Submitted:

04 June 2024

Posted:

05 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

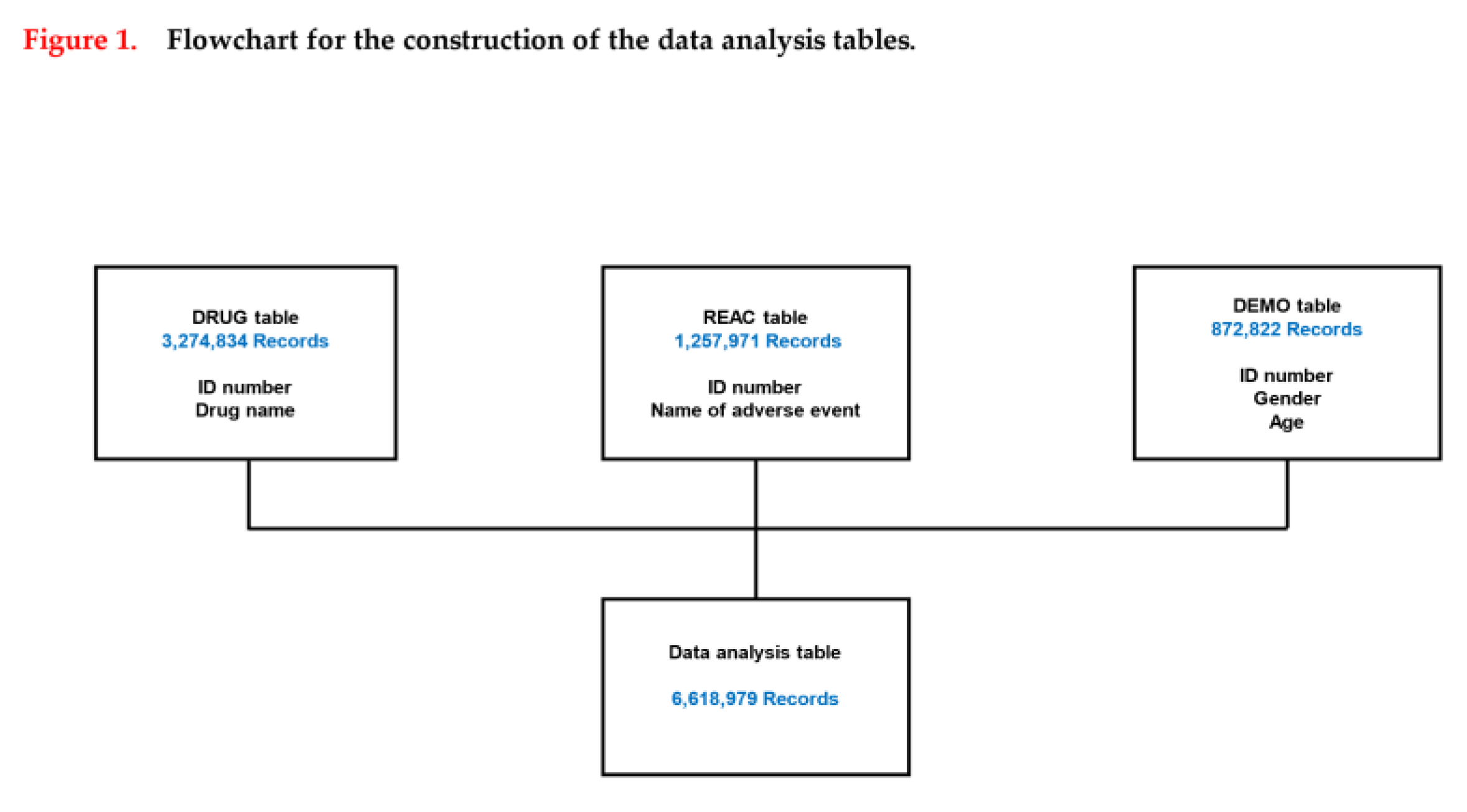

2.1. Preparing Data Tables for Analysis

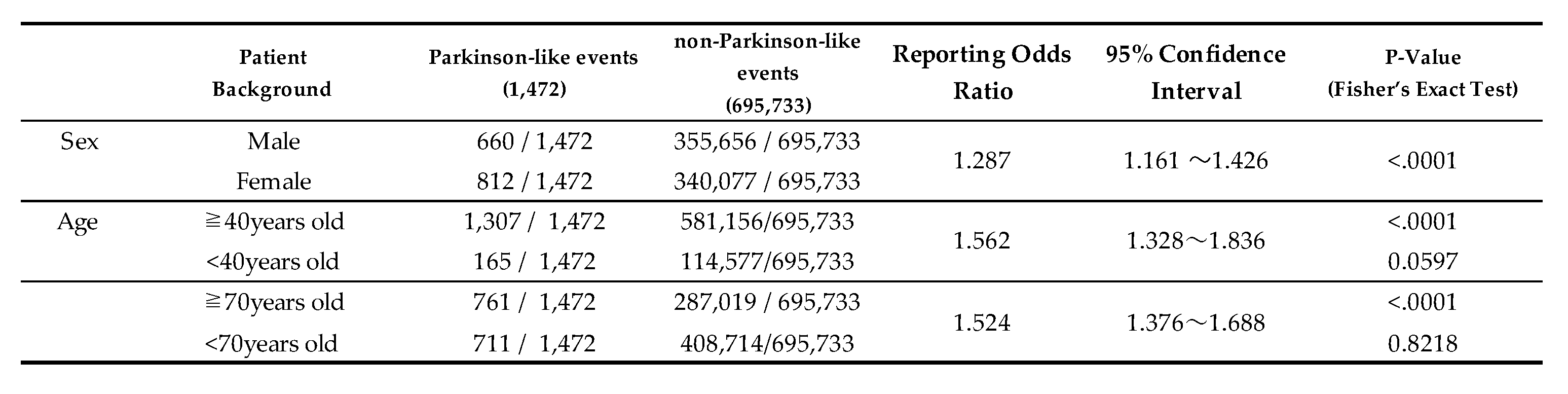

2.2. Relevance of Parkinson-like Events to Patient Characteristics

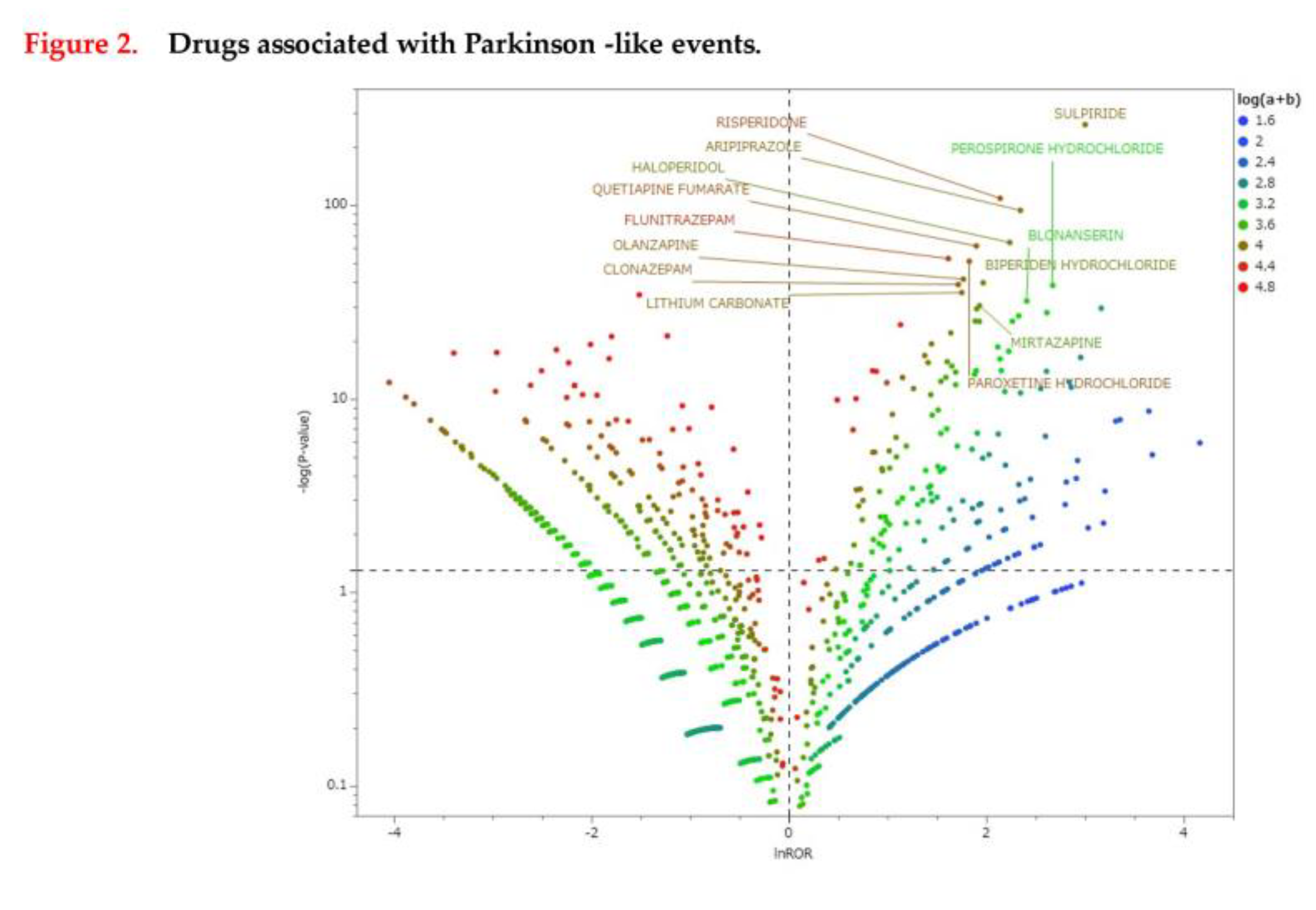

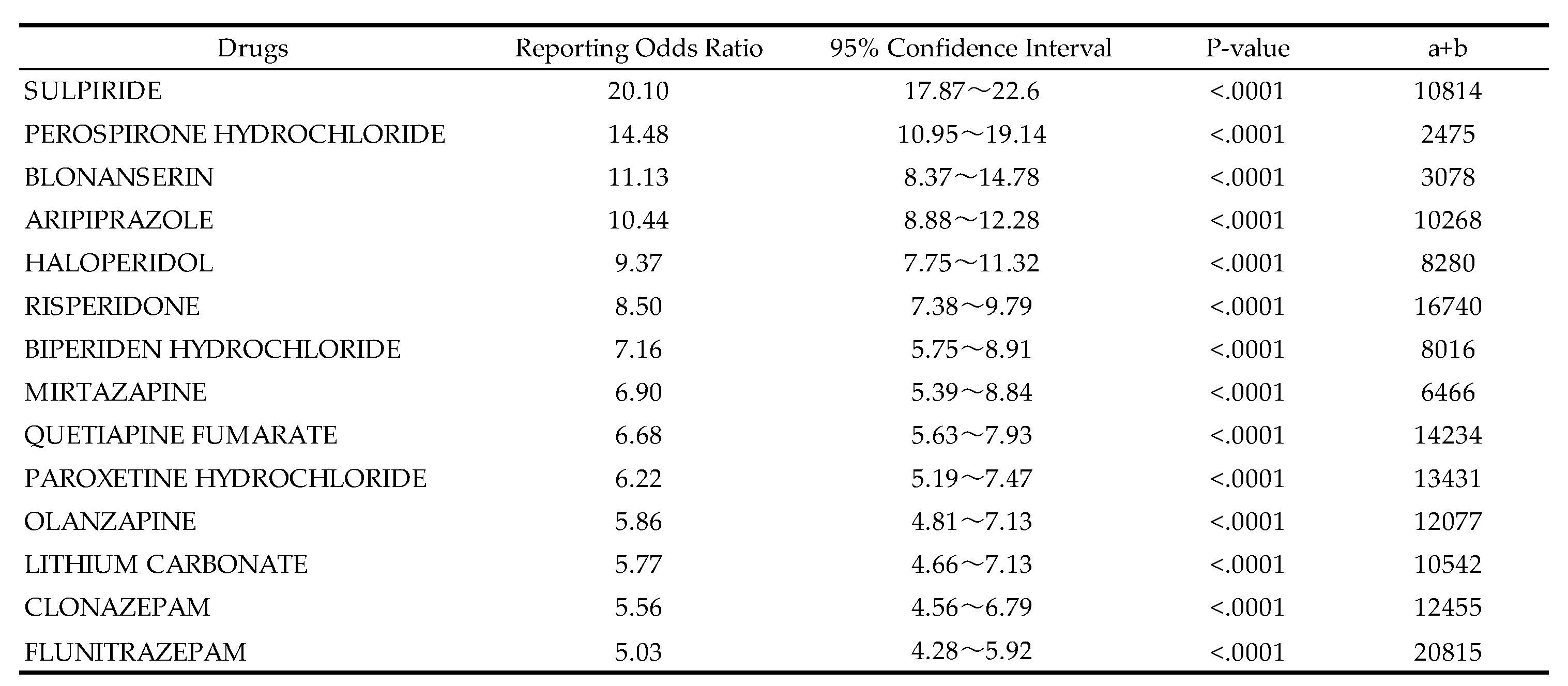

2.3. Relationship between Parkinson-like Events and Drugs

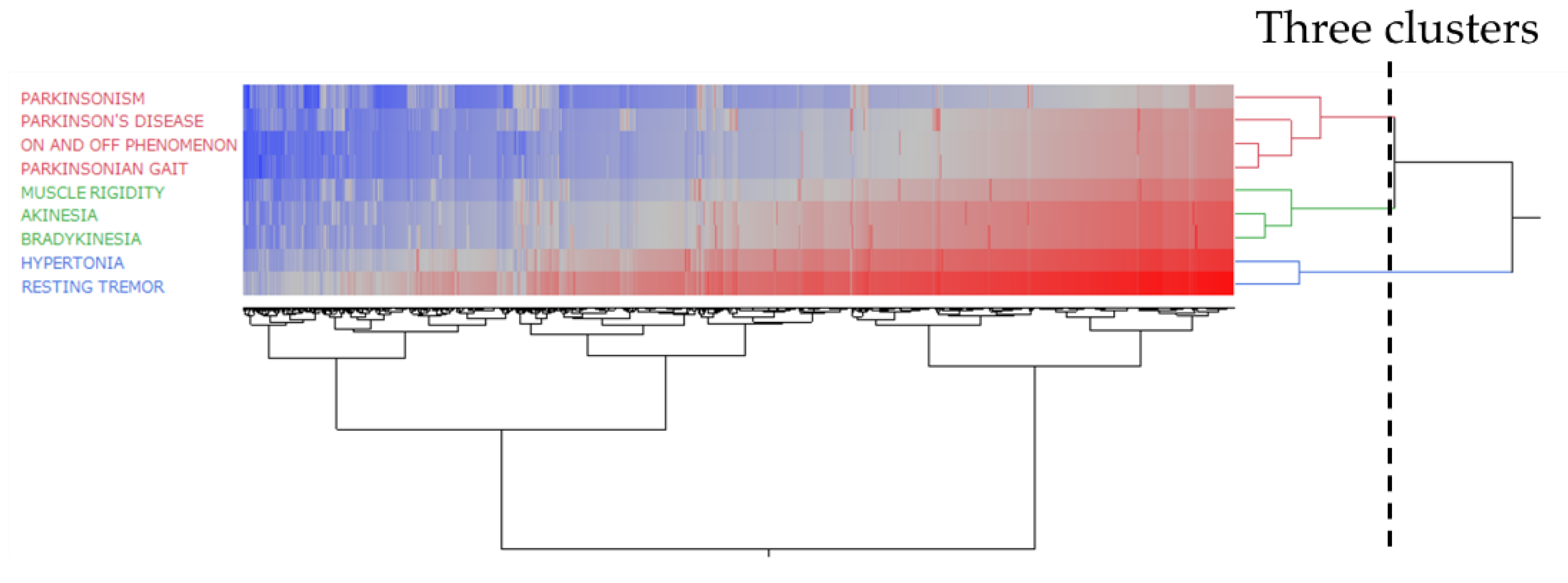

2.4. Hierarchical Clustering of Parkinson-like Events

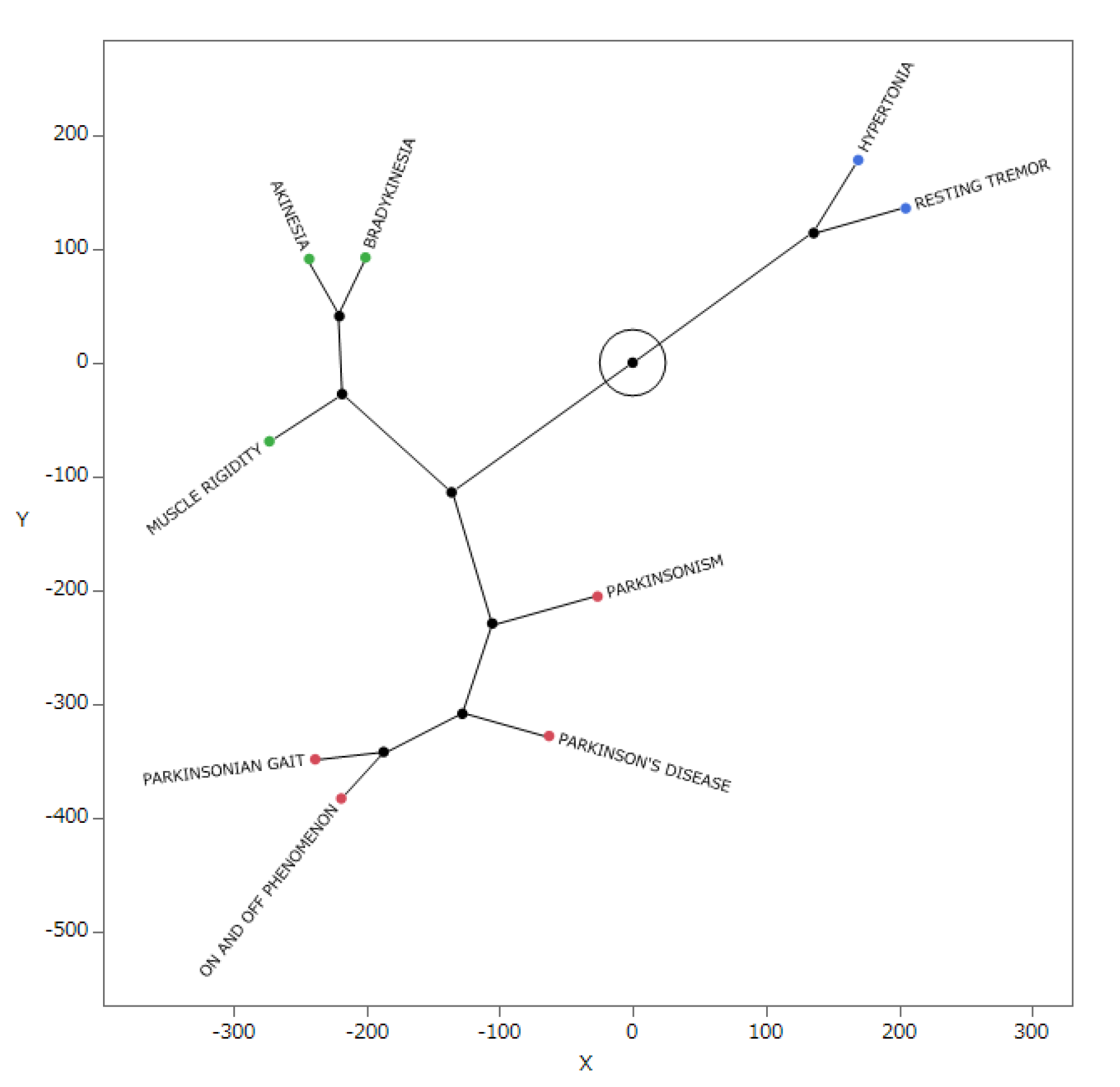

2.5. Star Dendrogram Associated with Parkinson-like Events

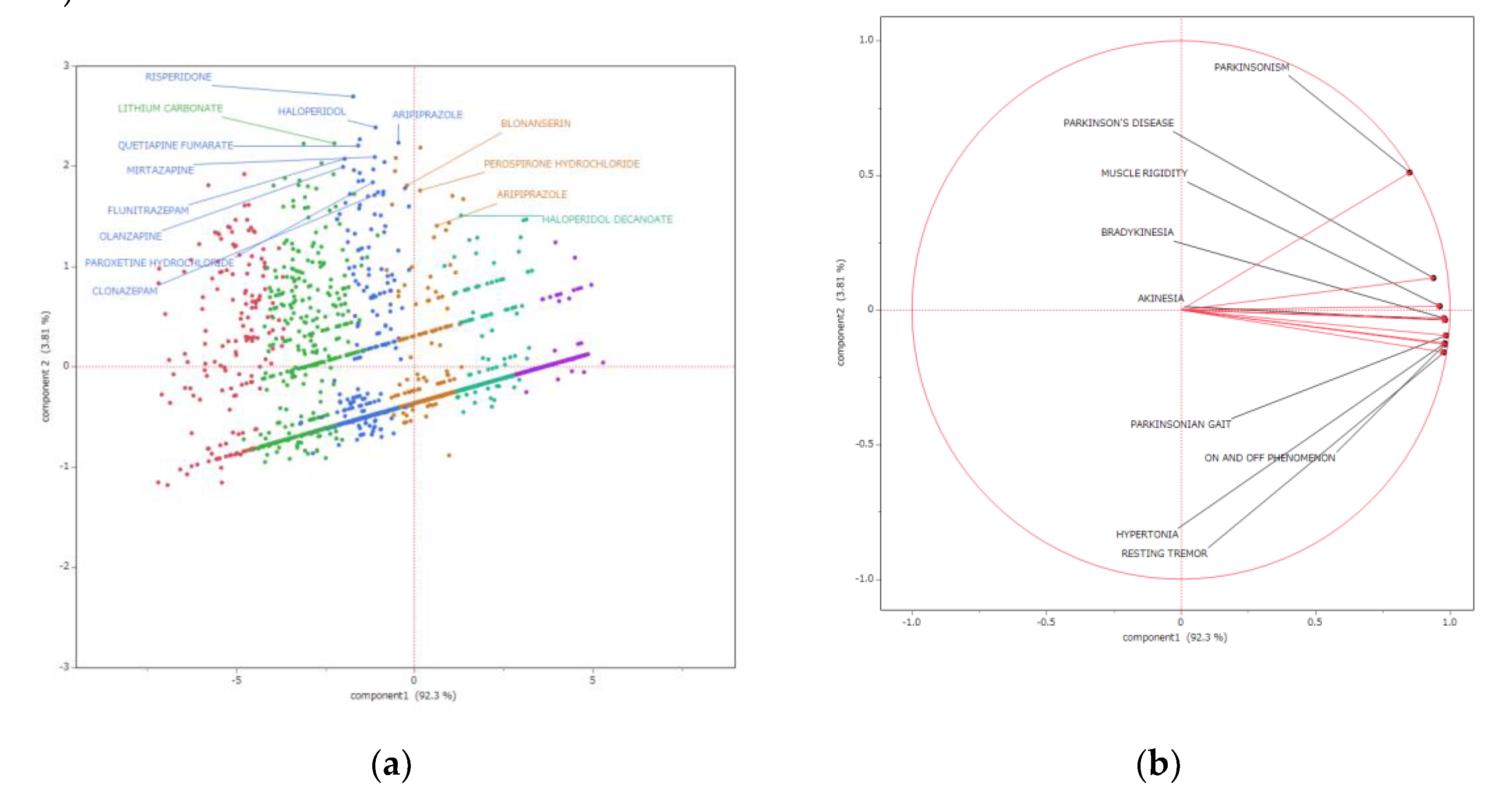

2.6. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) Shows Association between Parkinson-like Events and Drugs

3. Discussion

3.1. Parkinson-like Events and Patient Characteristics

3.2. Relationship between Parkinson-like Events and Drugs

3.3. Hierarchical Clustering Analysis of Side Effects Associated with Parkinsonian-like Events

3.4. Principal Component Analysis of Side Effects Related to Parkinson-like Events

3.5. Complex Parkinson-like Events Caused by Drugs

3.6. Limitations

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Database (JADER)

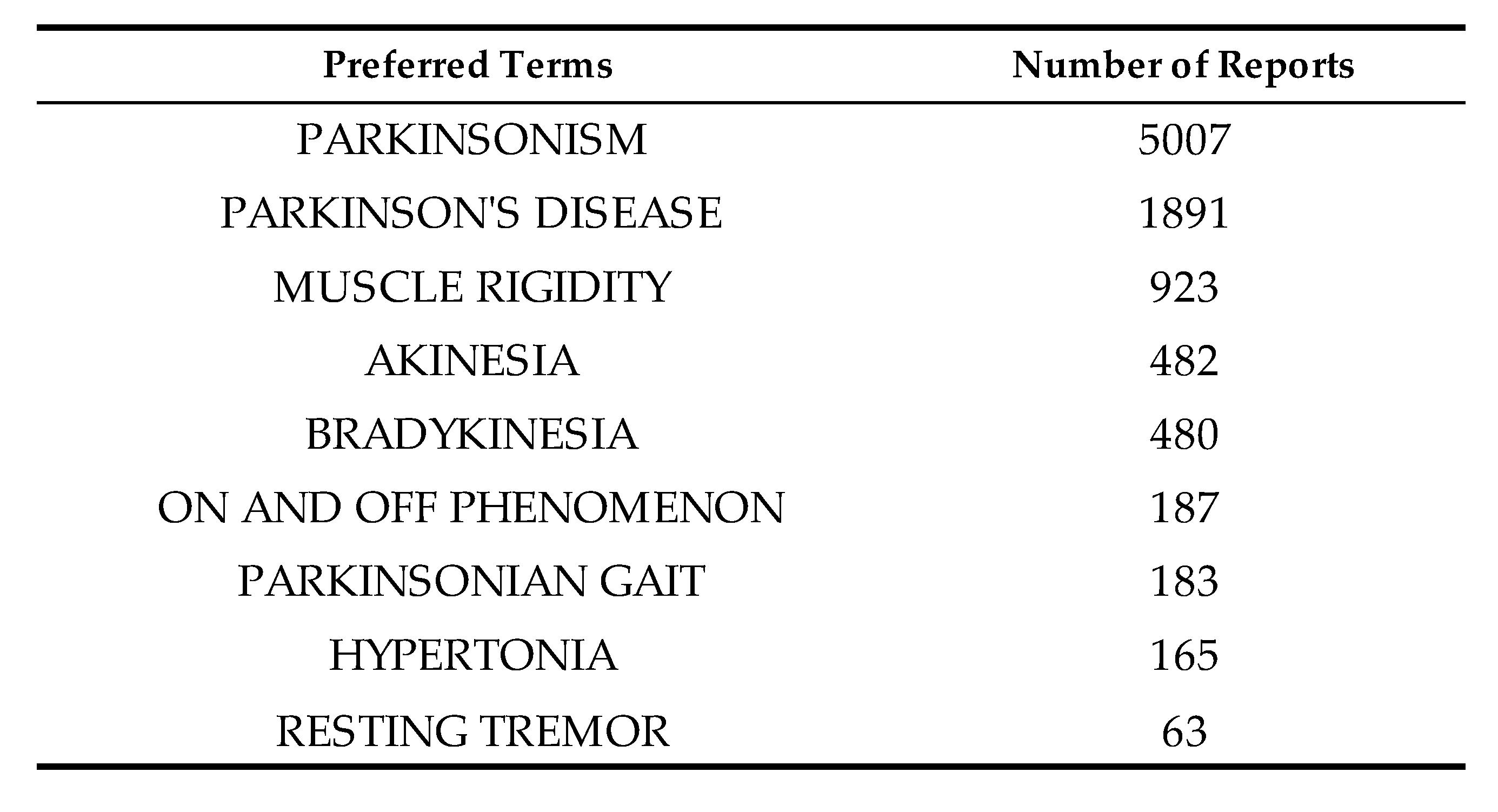

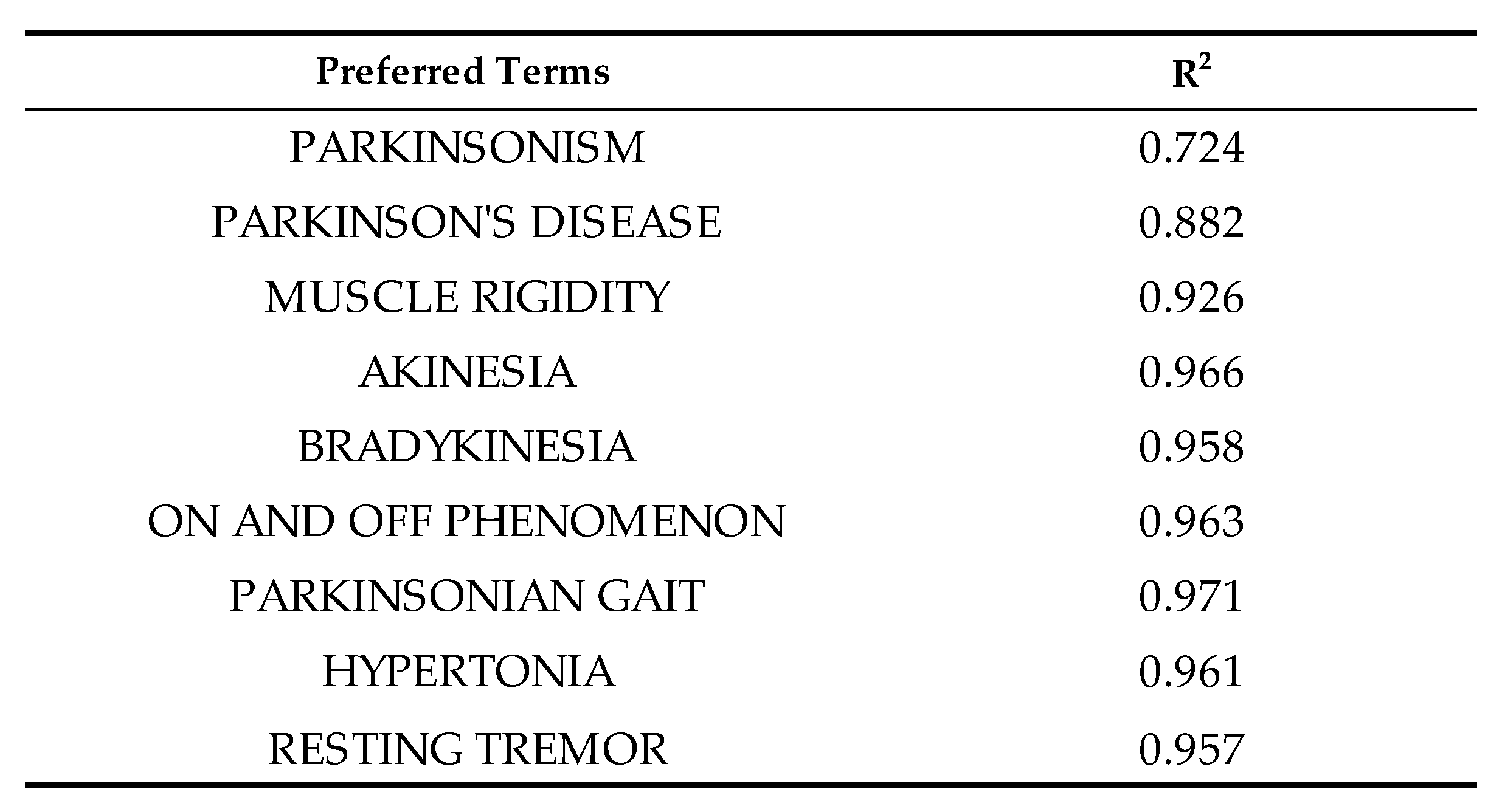

4.2. Drugs to Be Analyzed and Adverse Event Terms

4.3. Creation of a Data Table for Analysis

4.4. Parkinson-like Events and Patients Characteristics

4.5. Relationship between Parkinson-like Events and Drugs

4.4. Hierarchical Clustering

4.5. Principal Component Analysis

4.6. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Japanese Society of Neurology, Prologue. Parkinson's disease clinical practice guidelines 2018, "Parkinson's Disease Treatment Guidelines" Creation Committee, Igaku Shoin: Tokyo, Japan, 2018; pp.ⅶ.

- Correll, C.U.; Brevig, T. Brain C: Patient characteristics, burden, and pharmacotherapy of treatment-resistant schizophrenia: results from a survey of 204 US psychiatrists. BMC Psychiatry 2019, 19, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MedDRA Japanese Maintenance Organization. Available online: https://www.jmo.pmrj.jp/ (accessed on 29 March 2024).

- Farde, L.; Wiessel, F.A.; Halldin, C.; Sedvall, G. Central D2 dopamine receptor occupancy in schizophrenic patients treated with antipsychotic drugs. Arch Ben Psychiatry. 1988, 45, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Treatment manual for each serious side effect disease Drug-induced parkinsonism. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/topics/2006/11/dl/tp1122-1c01.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2024).

- Yoo, H.S.; Yunjin, B.; Seok, J.C.; Yoonju, L.; Byoung, S.Y.; Young, H.; Sohn; Na-Young, S. ; Phil, H.L. Impaired functional connectivity of sensorimotor network predicts recovery in drug-induced parkinsonism. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2020, 74, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wirdefeldt, K.; Adami, H.O.; Seok, J.C.; Cole, P.; Trichopoulos, D.; Mandel, J. Epidemiology, and etiology of Parkinson's disease: a review of the evidence. Eur J Epidemiol. 2011, 1, S1–S58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamawaki, M.; Kusumi, M.; Kowa, H.; Nakashima, K. Changes in Prevalence, and Incidence of Parkinson's Disease in Japan during a Quarter of a Century. Neuroepidemiology. 2009, 32, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajput, A.H.; Rajput, M.L.; Robinson, C.A.; Rajput, A. Normal Substantia Nigra Patients Treated with Levodopa - Clinical, Therapeutic, and Pathological Observations. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2015, 21, 1232–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brewer, G.J. Age-related toxicity to lactate, glutamate, and beta-amyloid in cultured adult neurons. Neurobiol Aging. 1998 Nov-Dec;19(6):561-568.

- Lim, S.-Y.; Fox, S. H.; Lang, A. E. Overview of the extranigral aspects of Parkinson's disease. Arch Neurol. 2009, 66(2), 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cremer, J. N.; Amunts, K.; Graw, J.; Piel, M.; Rösch, F.; Zilles, K. Neurotransmitter receptor density changes in Pitx3ak mice--a model relevant to Parkinson's disease. Neuroscience 2015, 285, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huot, P.; Fox, S.H.; Brotchie, J.M. The serotonergic system in Parkinson's disease. Prog Neurobiol. 2011, 95, 163–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rinne, U.K.; Koskinen, V.; Laaksonen, H.; Lönnberg, P.; Sonninen, V. GABA receptor binding in the parkinsonian brain. Life Sci. 1978, 22, 2225–2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaidel, A.; Arkadir, D.; Israel, Z.; Bergman, H. Akineto-rigid vs. tremor syndromes in Parkinsonism. Curr Opin Neurol, 2009 Aug;22(4):387-93.

- Péchadre, J.C.; Larochelle, L.; Poirier, L.J. Parkinsonian akinesia, rigidity, and tremor in the monkey. Histopathological and neuropharmacological study. J Neurol Sci, 1976 Jun;28(2):147-57.

- Helmich, R.C. The cerebral basis of Parkinsonian tremor: A network perspective. Mov Disord, 2018 Feb;33(2):219-231.

- Fearon, C.; Doherty, L.; Lynch, T. How Do I Examine Rigidity and Spasticity? Mov Disord Clin Pract. 2015 Mar 28;2(2):204.

- Ishii, T.; Kimura, Y.; Ichise, M.; Takahata, K.; Kitamura, S.; Moriguchi, S.; Kubota, M.; Zhang, M.R.; Yamada, M.; Higuchi, M.; Okubo, Y.; Suhara, T. Correction: Anatomical relationships between serotonin 5-HT2A and dopamine D2 receptors in living human brain. PLoS One. 2018, 13(5), e0197201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lloyd, K. G. The neuropathology of GABA neurons in extrapyramidal disorders. J. Neural Transm. Suppl. 1980, (16), 217–227. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M.; Ryu, Y. H.; Cho, W. G.; Kang, Y. W.; Lee, S. J.; Jeon, T. J.; Lyoo, C. H.; Kim, C. H.; Kim, D. G.; Lee, K.; Choi, T. H.; Choi, J. Y. Relationship between dopamine deficit and the expression of depressive behavior resulted from alteration of serotonin system. Synapse 2015, 69, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keller, H. H.; Schaffner, R.; Haefely, W. Interaction of benzodiazepines with neuroleptics at central dopamine neurons. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1976, 294, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maeda, R. JADER from pharmacovigilance point of view. Jpn. J. Pharmacoepidemiol. 2014, 19, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drug adverse reaction report data set bulk download. Available online: https://www.pmda.go.jp/safety/info-services/drugs/adr-info/suspected-adr/0004.html (accessed on 29 March 2024).

- Greenland, S.; Schwartzbaum, J.A.; Finkle, W.D. Problems due to small samples and sparse data in conditional logistic regression analysis. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2000, 151, 531–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Puijenbroek, E.P.; Bate, A.; Leufkens, H.G.M.; Lindquist, M.; Orre, R.; Egberts, A.C. A Comparison of measures of disproportionality for signal detection in spontaneous reporting systems for adverse drug reactions. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug. Saf. 2002, 11, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.J.; Wang, S.J.; Tsai, C.A.; Lin, C.J. Selection of differentially expressed genes in microarray data analysis. Pharm. J. 2007, 7, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakao, Y.; Kano, D.; Asada, M.; Kawasaki, T.; Uesawa, Y. Comprehensive Study of Drug-Induced Pruritus Based on Adverse Drug Reaction Report Database. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Everitt, B.S.; Landau, S.; Leese, M.; Stahl, D. Cluster Analysis, 5th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-0-470-74991-3. [Google Scholar]

| A crosstabulation table consisting of reports with the suspected drugs, all other reports, reports of Parkinson-like events, and reports of non-Parkinson-like events. | ||

| Parkinson-like events | Non-Parkinson-like events | |

| Reports with the suspected drugs | a | b |

| All other reports | c | d |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).