Submitted:

04 June 2024

Posted:

05 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

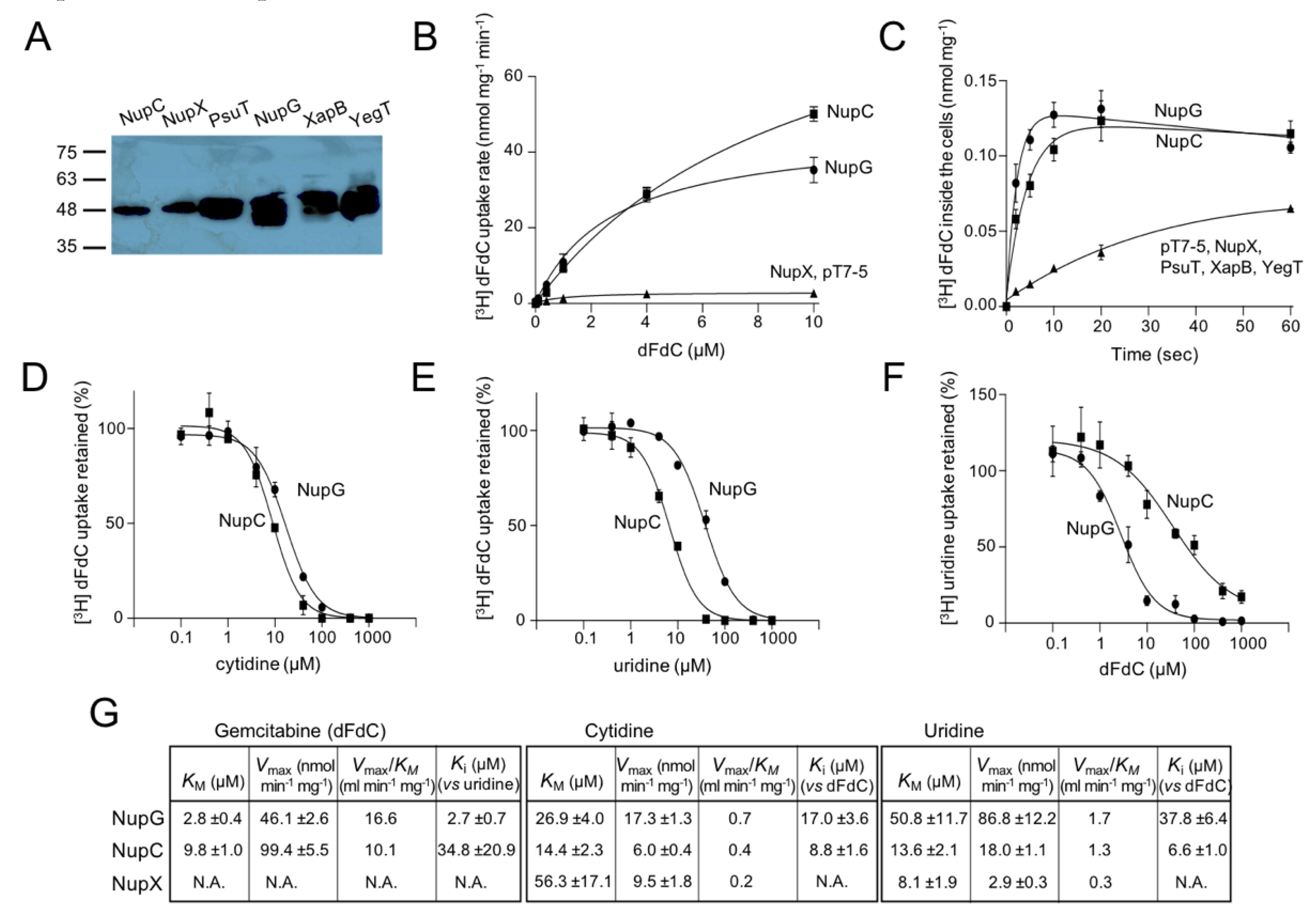

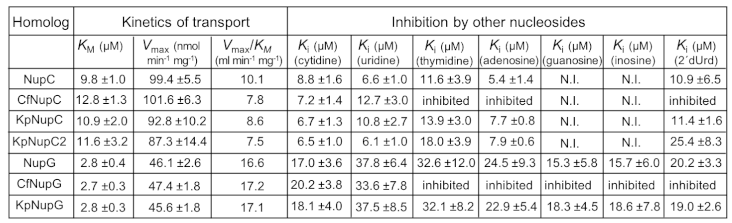

2.1. NupC and NupG are Efficient Gemcitabine Transporters of Escherichia coli K-12

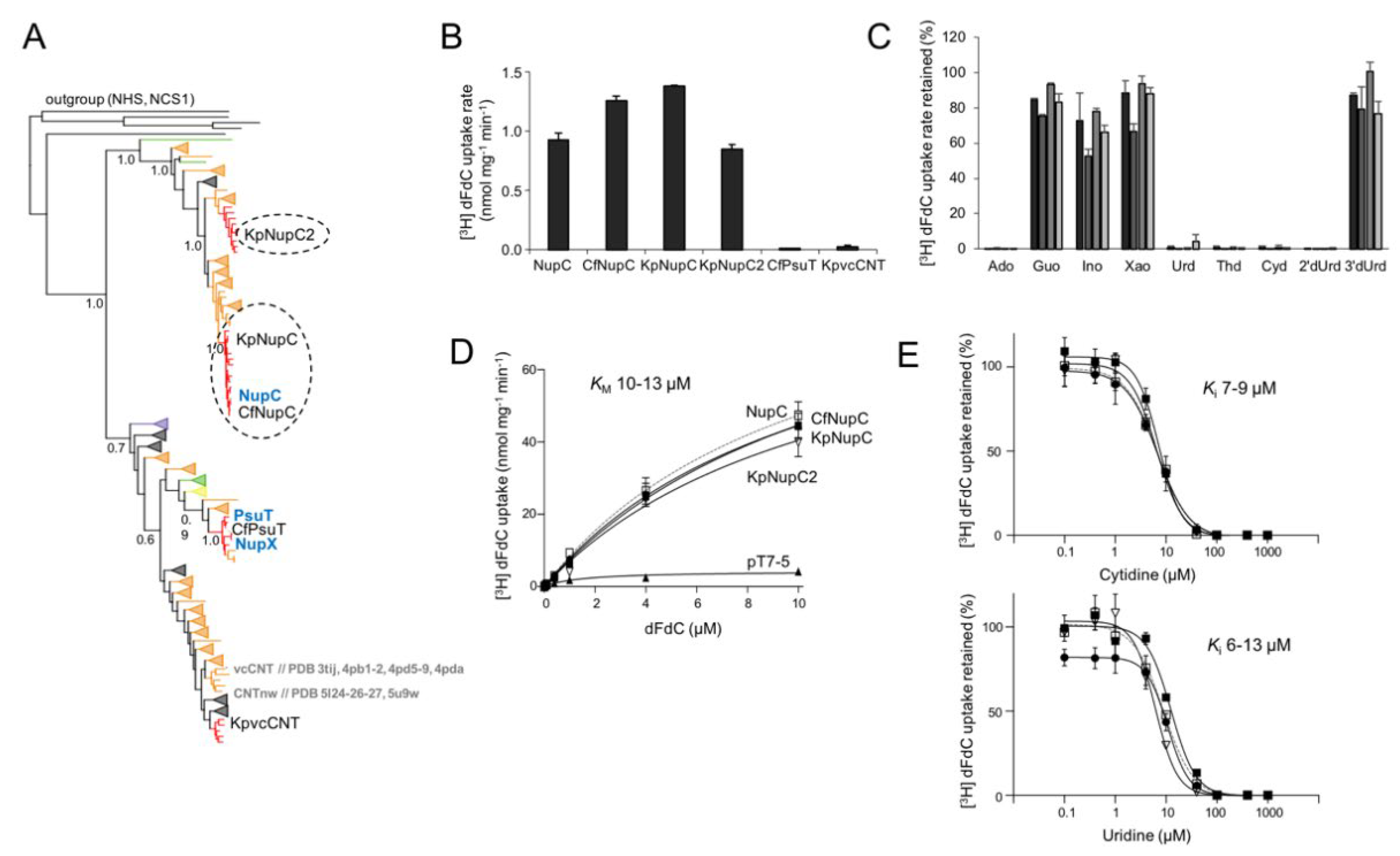

2.2. Phylogenetic Analysis of NupC and NupG Homologs in Proteobacteria

2.3. Functional Characterization of Gemcitabine-Transporting NupC Homologs of K. pneumoniae and C. freundii

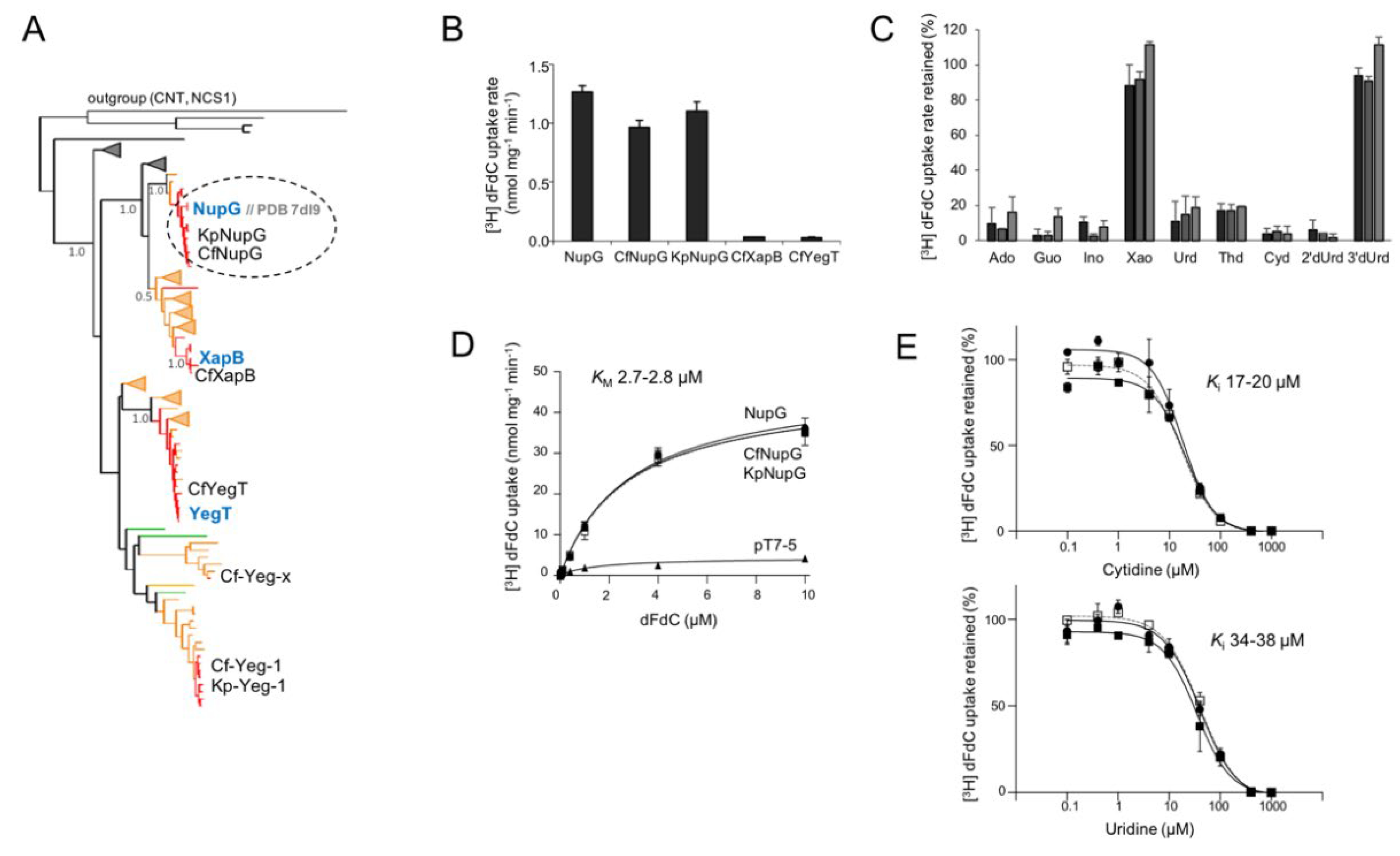

2.4. Functional Characterization of Gemcitabine-Transporting NupG Homologs of K. pneumoniae and C. freundii

2.5. Distinction of the NupG Functional Profile from the NupC Functional Profile

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Phylogenetic Analysis of CNT and NHS Families in Proteobacteria.

4.2. Materials for Wet-Lab Experiments and General Considerations

4.3. Bacterial Strains, Coding Sequences and Plasmids

4.4. Molecular Cloning and Bacterial Growth

4.5. Western Blot Analysis

4.6. Transport Assays and Kinetic Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Elion, G.B.; Hitchings, G.H. Metabolic basis for the actions of analogs of purines and pyrimidines. Adv. Chemother. 1965, 2, 91–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girardi, E.; César-Razquin, A.; Lindinger, S.; Papakostas, K.; Konecka, J.; Hemmerich, J.; Kickinger, S.; Kartnig, F.; Gürtl, B.; Klavins, K.; Sedlyarov, V.; Ingles-Prieto, A.; Fiume, G.; Koren, A.; Lardeau, C.-H.; Kandasamy, R.K.; Kubicek, S.; Ecker, G.F.; Superti-Furga, G. A widespread role for SLC transmembrane transporters in resistance to cytotoxic drugs. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2020, 16, 469–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, C.J.; Mekkawy, A.H.; Morris, D.L. Role of human nucleoside transporters in pancreatic cancer and chemoresistance. World J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 27, 6844–6860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koltai, T.; Reshkin, S.J.; Carvalho, T.M.A.; Di Molfetta, D.; Greco, M.R.; Alfarouk, K.O.; Cardone, R.A. Resistance to Gemcitabine in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma: A Physiopathologic and Pharmacologic Review. Cancers 2022, 14, 2486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geller, L.T.; Barzily-Rokni, M.; Danino, T.; Jonas, O.H.; Shental, N.; Nejman, D.; Gavert, N.; Zwang, Y.; Cooper, Z.A.; Shee, K.; Thaiss, C.A.; Reuben, A.; Livny, J.; Avraham, R.; Frederick, D.T.; Ligorio, M.; Chatman, K.; Johnston, S.E.; Mosher, C.M.; Brandis, A.; Fuks, G.; Gurbatri, C.; Gopalakrishnan, V.; Kim, M.; Hurd, M.W.; Katz, M.; Fleming, J.; Maitra, A.; Smith D., A.; Skalak, M.; Bu, J.; Michaud, M.; Trauger, S.A.; Barshack, I.; Golan, T.; Sandbank, J.; Flaherty, K.T.; Mandinova, A.; Garrett, W.S.; Thayer, S.P.; Ferrone, C.R.; Huttenhower, C.; Bhatia, S.N.; Gevers, D.; Wargo, J.A.; Golub, T.R.; Straussman, R. Potential role of intratumor bacteria in mediating tumor resistance to the chemotherapeutic drug gemcitabine. Science 2017, 357, 1156–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nejman, D.; Livyatan, I.; Fuks, G.; Gavert, N.; Zwang, Y.; Geller, L.T.; Rotter-Maskowitz, A.; Weiser, R.; Mallel, G.; Gigi, E.; Meltser, A.; Douglas, G.M.; Kamer, I.; Gopalakrishnan, V.; Dadosh, T.; Levin-Zaidman, S.; Avnet, S.; Atlan, T.; Cooper, Z.A.; Arora, R.; Cogdill, A.P.; Khan, M.A.W.; Ologun, G.; Bussi, Y.; Weinberger, A.; Lotan-Pompan, M.; Golani, O.; Perry, G.; Rokah, M.; Bahar-Shany, K.; Rozeman, E.A.; Blank, C.U.; Ronai, A.; Shaoul, R.; Amit, A.; Dorfman, T.; Kremer, R.; Cohen, Z.R.; Harnof, S.; Siegal, T.; Yehuda-Shnaidman, E.; Gal-Yam, E.N.; Shapira, H.; Baldini, N.; Langille, M.G.I.; Ben-Nun, A.; Kaufman, B.; Nissan, A.; Golan, T.; Dadiani, M.; Levanon, K.; Bar, J.; Yust-Katz, S.; Barshack, I.; Peeper, D.S.; Raz, D.J.; Segal, E.; Wargo, J.A.; Sandbank, J.; Shental, N.; Straussman, R. The human tumor microbiome is composed of tumor type-specific intracellular bacteria. Science 2020, 368, 973–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, Z.L.; Cheong, C.-G.; Lee, S.-Y. Crystal structure of a concentrative nucleoside transporter from Vibrio cholerae at 2.4 Å. Nature 2012, 483, 489–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Xiao, Q.; Duan, H.; Li, J.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Q.; Guo, L.; Hu, J.; Sun, B.; Deng, D. Molecular basis for substrate recognition by the bacterial nucleoside transporter NupG. J. Biol. Chem. 2021, 296, 100479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, N.J.; Lee, S.-Y. Toward a molecular basis of cellular nucleoside transport in humans. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 5336–5358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, J.D. The SLC28 (CNT) and SLC29 (ENT) nucleoside transporter families: a 30-year collaborative odyssey. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2016, 44, 869–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordh, S.; Ansari, D.; Andersson, R. hENT1 expression is predictive of gemcitabine outcome in pancreatic cancer: A systematic review. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 8482–8490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenhalf, W.; Ghaneh, P.; Neoptolemos, J.P.; Palmer, D.H.; Cox, T.F.; Lamb, R.F.; Garner, E.; Campbell, F.; Mackey, J.R.; Costello, E.; Moore, M.J.; Valle, J.W.; McDonald, A.C.; Carter, R.; Tebbutt, N.C.; Goldstein, D.; Shannon, J.; Dervenis, C.; Glimelius, B.; Deakin., M.; Charnley, R.M.; Lacaine, F.; Scarfe, A.G.; Middleton, M.R.; Anthoney, A.; Halloran, C.M.; Mayerle, J.; Oláh, A.; Jackson, R.; Rawcliffe, C.L.; Scarpa, A.; Bassi, C.; Büchler, M.W.; European Study Group for Pancreatic Cancer. Pancreatic cancer hENT1 expression and survival from gemcitabine in patients from the ESPAC-3 trial. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2014, 106, djt347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spratlin, J.L.; Mackey, J.R. Human Equilibrative Nucleoside Transporter 1 (hENT1) in Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma: Towards individualized treatment decisions. Cancers 2010, 2, 2044–2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skrypek, N.; Duchêne, B.; Hebbar, M.; Leteurtre, E.; van Seuningen, I.; Jonckheere, N. The MUC4 mucin mediates gemcitabine resistance of human pancreatic cancer cells via the concentrative nucleoside transporter family. Oncogene 2012, 32, 1714–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhutia, Y.D.; Hung, S.W.; Patel, B.; Lovin, D.; Govindarajan, R. CNT1 expression influences proliferation and chemosensitivity in drug-resistant pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2011, 71, 1825–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hesler, R.A.; Huang, J.J.; Starr, M.D.; Treboschi, V.M.; Bernake, A.G.; Nixon, A.B.; McCall, S.J.; White, R.R.; Blobe, G.C. TGF-β-induced stromal CYR61 promotes resistance to gemcitabine in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma through downregulation of the nucleoside transporters hENT1 and hCNT3. Carcinogenesis 2016, 37, 1041–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loewen, S.K.; Yao, S.Y.; Slugoski, M.D.; Mohabir, N.N.; Turner, R.J.; Mackey, J.R.; Weiner, J.H.; Gallagher, M.P.; Henderson, P.J.; Baldwin, S.A.; Cass, C.E.; Young, J.D. Transport of physiological nucleosides and anti-viral and anti-neoplastic nucleoside drugs by recombinant Escherichia coli nucleoside:H+ cotransporter (NupC) produced in Xenopus laevis oocytes. Mol. Membr. Biol. 2004, 21, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preumont, A.; Snoussi, K.; Stroobant, V.; Collet, J.-F.; Schaftingen, E.V. Molecular identification of pseudouridine-metabolizing enzymes. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 25238–25246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norholm, M.H.; Dandanell, G. Specificity and topology of the Escherichia coli xanthosine permease, a representative of the NHS sub-family of the major facilitator superfamily. J. Bacteriol. 2001, 183, 4900–4904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saylin, S.; Rosener, B.; Li, C.G.; Ho, B.; Ponomarova, O.; Ward, D.V.; Walhout, A.J.M.; Mitchell, A. Evolved bacterial resistance to the chemotherapy gemcitabine modulates its efficacy in co-cultured cancer cells. eLife 2023, 12, e83140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Patching, S.G.; Galagher, M.P.; Litherland, G.J.; Brough, A.R.; Venter, H.; Yao, S.Y.M.; Ng, A.M.L.; Young, J.D.; Herbert, R.B.; Henderson, P.J.F.; Baldwin, S.A. Purification and properties of the Escherichia coli nucleoside transporter NupG, a paradigm for a major facilitator transporter sub-family. Mol. Membr. Biol. 2004, 21, 323–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, Z.L.; Lee, J.-H.; Lee, K.; Lee, M.; Kwon, D.-Y.; Hong, J.; Lee, S.-Y. Structural basis of nucleoside and nucleoside drug selectivity by concentrative nucleoside transporters. eLife 2014, 3, e03604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirschi, M.; Johnson, Z.L.; Lee, S.-Y. Visualizing multistep elevator-like transitions of a nucleoside transporter. Nature 2017, 545, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, I.-M.A.; Chu, K.; Palaniappan, K.; Ratner, A.; Huang, J.; Huntermann, M.; Hajek, P.; Ritter, S.J.; Webb, C.; Wu, D.; Varghese, N.J.; Reddy, T. B. K.; Mukherjee, S.; Ovchinnikova, G.; Nolan, M.; Seshardi, R.; Roux, S.; Visel, A.; Woyke, T.; Eloe-Fadrosh, E.A.; Kyprides, N.C.; Ivanova, N.N. The IMG/M data management and analysis system v.7: content updates and new features. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D723–D732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackey, J.R.; Yao, S.Y.M.; Smith, K.M.; Karpinski, E.; Baldwin, S.A.; Cass, C.E.; Young, J.D. Gemcitabine transport in Xenopus oocytes expressing recombinant plasma membrane mammalian nucleoside transporters. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1999, 21, 1876–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackey, J.R.; Baldwin, S.A.; Young, J.D.; Cass, C.E. Nucleoside transport and its significance for anticancer drug resistance. Drug Resist. Updat. 1998, 1, 310–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackey, J.R.; Mani, R.S.; Selner, M.; Mowles, D.; Young, J.D.; Belt, J.A.; Crawford, C.R.; Cass, C.E. Functional nucleoside transporters are required for gemcitabine influx and manifestation of toxicity in cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 1998, 58, 4349–4357. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- García-Manteiga, J.; Molina-Arcas, M.; Casado, F.J.; Mazo, A.; Pastor-Anglada, M. Nucleoside transporter profiles in human pancreatic cancer cells: role of hCNT1 in 2',2'-difluorodeoxycytidine- induced cytotoxicity. Clin. Cancer Res. 2003, 9, 5000–5008. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, H.; Endres, C.J.; Chang, C.; Umapathy, N.S.; Lee, E.W.; Fei, Y.J.; Itagaki, S.; Swaan, P.W.; Ganapathy, V.; Unadkat, J.D. Electrophysiological characterization and modeling of the structure activity relationship of the human concentrative nucleoside transporter 3 (hCNT3). Mol. Pharmacol. 2006, 69, 1542–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drew, D.; Boudker, O. Shared molecular mechanisms of membrane transporters. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2016, 85, 543–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, N. Structural biology of the major facilitator superfamily transporters. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2015, 44, 257–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffiths, M.; Beaumont, M.; Yao, S.Y.; Sundaram, M.; Boumah, C.E.; Davies, A.; Kwong, F.Y.; Coe, I.; Cass, C.E.; Young, J.D.; Baldwin, S.A. Cloning of a human nucleoside transporter implicated in the cellular uptake of adenosine and chemotherapeutic drugs. Nat. Med. 1997, 3, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, J.L.; Sherali, A.; Mo, Z.P.; Tse, C.M. Kinetic and pharmacological properties of cloned human equilibrative nucleoside transporters, ENT1 and ENT2, stably expressed in nucleoside transporter-deficient PK15 cells. Ent2 exhibits a low affinity for guanosine and cytidine but a high affinity for inosine. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 8375–8381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, S.Y.; Ng, A.M.L.; Cass, C.E.; Baldwin, S.A.; Young, J.D. Nucleobase transport by human equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1 (hENT1). J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 32552–32562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, W.; Zeng, X.; Shi, Y.; Liu, M. Functional characterization of human equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1. Protein Cell 2017, 8, 284–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, N.J.; Lee, S.-Y. Structures of human ENT1 in complex with adenosine reuptake inhibitors. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2019, 26, 599–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanehisa, M.; Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Tamura, K. MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016, 33, 1870–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corpet, F. Multiple sequence alignment with hierarchical clustering. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988, 16, 10881–10890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatza, P.; Frillingos, S. Cloning and functional characterization of two bacterial members of the NAT/NCS2 family in Escherichia coli. Mol Membr Biol. 2005, 22, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baba, T.; Ara, T.; Hasegawa, M.; Takai, Y.; Okumura, Y.; Baba, M.; Datsenko, K.A.; Tomita, M.; Wanner, B.L.; Mori, H. Construction of Escherichia coli K-12 in-frame, single-gene knockout mutants: the Keio collection. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2006, 2, 2006–0008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inoue, H.; Nojima, H.; Okayama, H. High efficiency transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. Gene 1990, 96, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Botou, M.; Lazou, P.; Papakostas, K.; Lambrinidis, G.; Evangelidis, T.; Mikros, E.; Frillingos, S. Insight on specificity of uracil permeases of the NAT/NCS2 family from analysis of the transporter encoded in the pyrimidine utilization operon of Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 2018, 108, 204–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Y.; Prusoff, W.H. Relationship between the inhibition constant (Ki) and the concentration of inhibitor which causes 50 per cent inhibition (I50) of an enzymatic reaction. Biochem Pharmacol. 1973, 22, 3099–3108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).