Introduction

Postpartum haemorrhage (PPH) remains a critical global health issue, particularly in low- and middle-income countries, where it continues to be the leading factor of maternal mortality and morbidity. PPH still accounts for about 8% and 20% of maternal mortality in developed and developing countries, respectively, despite being a preventable event [

1]. About 14 million women experience PPH each year, resulting in approximately 70,000 maternal deaths globally [

2]. A primary PPH is typically understood as a blood loss of 500ml or more within 24 hours of vaginal birth and 1000ml or more of Caesarean section deliveries (CS) [

3]. Depending on a woman’s circumstances, clinicians may use lower or greater blood loss thresholds to initiate intervention [

4]. Indeed, a healthy or well-nourished woman may endure a more significant amount of blood loss than women with anaemia or chronic diseases, who might suffer grave repercussions with less than 500ml of blood loss. Therefore, it is critical to personalise care to understand a woman’s risk of developing a PPH better [

5,

6].

Recent evidence indicates that PPH is becoming more common, especially in developed countries and settings with high resources. The rise in underlying risk factors for obesity, pre-eclampsia, and CS is all believed to be important, even though the reasons for these changes remain unknown [

6,

7,

8,

9]. Furthermore, despite many identified risk factors, PPH is still unpredictable, and even those with the lowest risk can experience this obstetric emergency at any time. This places a significant burden on the strategies of PPH prevention and treatment since they imply that all pregnant women are thought to be at risk for postnatal bleeding [

6].

Vietnam, with its unique sociodemographic and healthcare landscape, has witnessed both progress and challenges in reducing maternal mortality rates over recent years. Recent reports show that PPH incidences have decreased significantly, notably since the Ministry of Health released the national guideline in 2000 and revised it in 2009 and 2016 [

10]. However, PPH-related maternal death remains dominant. While in 2000 – 2001, PPH was responsible for 41% of all maternal deaths across the country [

11], this rate was reported at 31.1% in 2022 [

12].

Given the significance of PPH as a preventable cause of maternal mortality, it is imperative to examine the current state of knowledge and research pertaining to this condition in the context of Vietnam. This review aims to provide a comprehensive overview of existing research on PPH within the Vietnamese healthcare system, focusing on risk factors, prevalence, prevention, and management strategies. By synthesising the available evidence, this review seeks to identify gaps in knowledge, areas for improvement, and potential directions for future research and policy development to enhance maternal health outcomes in Vietnam further. Understanding the specific challenges and opportunities related to PPH in the Vietnamese context is vital for informing evidence-based interventions and contributing to the broader global effort to reduce maternal mortality.

In undertaking this literature review on PPH, a meticulous approach was employed, leveraging databases affiliated with medical universities in Vietnam to ensure a targeted exploration of the local research landscape. Electronic repositories, including those associated with institutions such as the Hanoi Medical University, Military Medical University, Hue Medical University and Ho Chi Minh City University of Medicine and Pharmacy, would be queried alongside global databases such as PubMed, Scopus, and Google Scholar. The search strategy employed keywords such as “postpartum haemorrhage”, “maternal mortality”, and “PPH management”, “Vietnam” in both English and Vietnamese languages to capture a comprehensive spectrum of literature.

Postpartum Haemorrhage

Definition Discrepancies

The varying definitions of PPH as outlined in national guidelines and those specific to maternity hospitals introduce an essential dimension to the understanding of this critical obstetric complication in Vietnam. According to the national guideline, PPH is defined as blood loss exceeding 500ml [

10]. This threshold serves as a general benchmark for identifying and managing PPH cases nationwide. However, several prominent maternity healthcare institutions’ guidelines in Vietnam introduce a nuanced perspective. For instance, in the context of Tu Du Hospital, the definition of PPH is contingent on the mode of delivery, with blood loss exceeding 500ml considered indicative of PPH in vaginal births and a higher threshold of 1000ml applied to CSs [

13]. This discrepancy in the PPH criteria between the national and hospital-specific guidelines underscores the complexity of standardising definitions within a diverse healthcare landscape.

The existence of dual guidelines raises questions about the potential impact on clinical practices, resource allocation, and the accuracy of reported PPH incidences. Analysing and reconciling these definition variations is crucial for clinical management and epidemiological studies related to PPH in Vietnam. This nuanced understanding will contribute to developing targeted interventions and policies tailored to the specific context of healthcare facilities, ensuring that the management of PPH aligns with the realities of diverse obstetric practices and contributes to improved maternal outcomes.

Epidemiological Insights

The occurrence of PPH in Vietnam reveals discrepancies in prevalence rates across various regions nationwide. Recent investigations indicate discernible differences in PPH rates between hospitals in the northern and southern regions. The incidence of PPH in the North has remained relatively stable, but significant changes have occurred in the South. Indeed, medical facilities in the northern areas exhibit lower PPH rates, ranging from 0.24% to 0.55%, whereas Southern healthcare settings grapple with a notable burden of PPH, with rates ranging from 2.25% to 4.3% [

14,

15,

16,

17].

Table 1 below indicates the PPH-related studies since 2020.

Aetiology and Risk Factors

Generally, the aetiology of PPH in Vietnam shares similarities with global patterns, often described by the four T's, including Tone, Trauma, Tissue, and Thrombin. Uterine atony emerges as the predominant cause, accounting for over 70% of cases, followed by genital tract trauma, which contributes to approximately 20% of cases [

22]. Trauma may arise from perineal or cervical lacerations, episiotomy, or uterine rupture. Instances of retained placental fragments and coagulation abnormalities are comparatively infrequent. Research findings from Vietnam parallel international trends, wherein uterine atony comprises 68.2% of PPH cases, while genital tract trauma represents 17.4% [

23]. Notably, uterine rupture accounts for 4.2% of cases [

24], mainly observed in primary healthcare facilities. Conversely, there has been a gradual rise in cases involving placenta previa and placenta accreta, while the incidence of retained placenta has declined [

24]. Coagulation abnormalities, typically secondary to uterine atony, are reported in 4.3% of cases [

23].

Uncontrolled or untreated haemorrhage poses a significant risk of shock and mortality, with the majority of PPH-related deaths occurring within the first week postpartum [

25]. Several factors influence the likelihood of fatal PPH outcomes. Extensive research has explored variables associated with increased PPH incidence, including anaemia, multiple gestations, pre-eclampsia, operative vaginal delivery, and prolonged labour. Despite the association of these factors with heightened PPH risk, two-thirds of cases occur in women without identifiable risk factors, underscoring the necessity for vigilant postpartum monitoring [

26].

While the conventional definition of PPH typically denotes blood loss exceeding 500ml, in Vietnam, a wide-acceptable threshold of over 300ml is often considered to trigger the PPH treatment due to prevalent anaemia among women, rendering them less tolerant to blood loss [

4]. Anemic women face a substantially elevated risk of PPH, with a 21-fold increase compared to non-anemic counterparts [

27]. Additionally, home births, influenced by cultural preferences, economic constraints, or limited access to quality healthcare services, contribute significantly to PPH occurrences [

12]. High parity is another noteworthy risk factor, with multiparous women, particularly those with a history of prior PPH, facing a twofold increase in risk. Prolonged labour and the use of oxytocin are associated with a fourfold increase in PPH risk [

23], while macrosomic infants, defined inconsistently in Vietnamese literature (estimated foetal weight >3500 or >4000g), present elevated PPH risks [

27]. Notably, instrumental delivery, particularly forceps application, substantially increases PPH risk, underscoring the need for judicious use of such interventions to mitigate PPH incidence [

23].

Strategies for PPH Prevention

Preventative strategies for PPH should be initiated proactively, preferably commencing prior to conception, by identifying individuals at high risk and implementing interventions to enhance iron stores and haemoglobin levels as necessary. Assessing pregnant women for PPH risk factors throughout pregnancy and labour can aid in delivery preparation, including determining the most suitable delivery setting. Blood typing and screening are essential for individuals at moderate risk of PPH. In contrast, those at high risk should undergo blood typing and cross-matching of a minimum of two units of packed red blood cells in anticipation of potential PPH.

Table 2 below shows the suggested classification when assessing each individual's PPH risk.

The active management of the third stage of labour, which involves the preventive administration of uterotonic medications and controlled pulling of the umbilical cord, has demonstrated efficacy in minimising blood loss during this phase and lowering the likelihood of PPH by around 66% compared to a more passive approach [

28]. Nevertheless, controlled umbilical cord traction offers limited advantages in severe PPH scenarios. It may pose risks such as uterine inversion, notably if the attending medical team lacks experience in its implementation [

29].

Approaches to PPH Treatment

Initial Approach

The management of PPH requires a coordinated multidisciplinary approach involving effective communication, accurate blood loss assessment, continuous monitoring of maternal vital signs, fluid replacement, and prompt intervention to control bleeding [

30]. Accurate blood loss assessment is pivotal in managing PPH [

31]. It can be achieved through visual estimation (using V-drape) or quantification methods (weighing blood-soaked materials such as sponges and cotton underpads). While there is no definitive evidence favouring one method over the other, quantitative estimation offers greater precision than subjective assessment. Although obstetrics and gynaecology societies advocate for quantitative estimation methods, including weighing blood-soaked materials and monitoring fluid usage during irrigation, equipping all medical facilities in Vietnam with the necessary equipment for blood loss measurement is currently impossible and unfeasible [

32].

Upon admission for delivery, women at high risk for PPH should undergo appropriate interventions, including the insertion of large-bore intravenous cannulas, obtaining a complete blood count, and notifying the blood bank for blood typing and crossmatching. Additional monitoring tailored to the specific risk factors may include continuous pulse oximetry, assessment of urine output, continuous cardiac monitoring, evaluation of coagulation status, and comprehensive metabolic panel analysis [

22,

31].

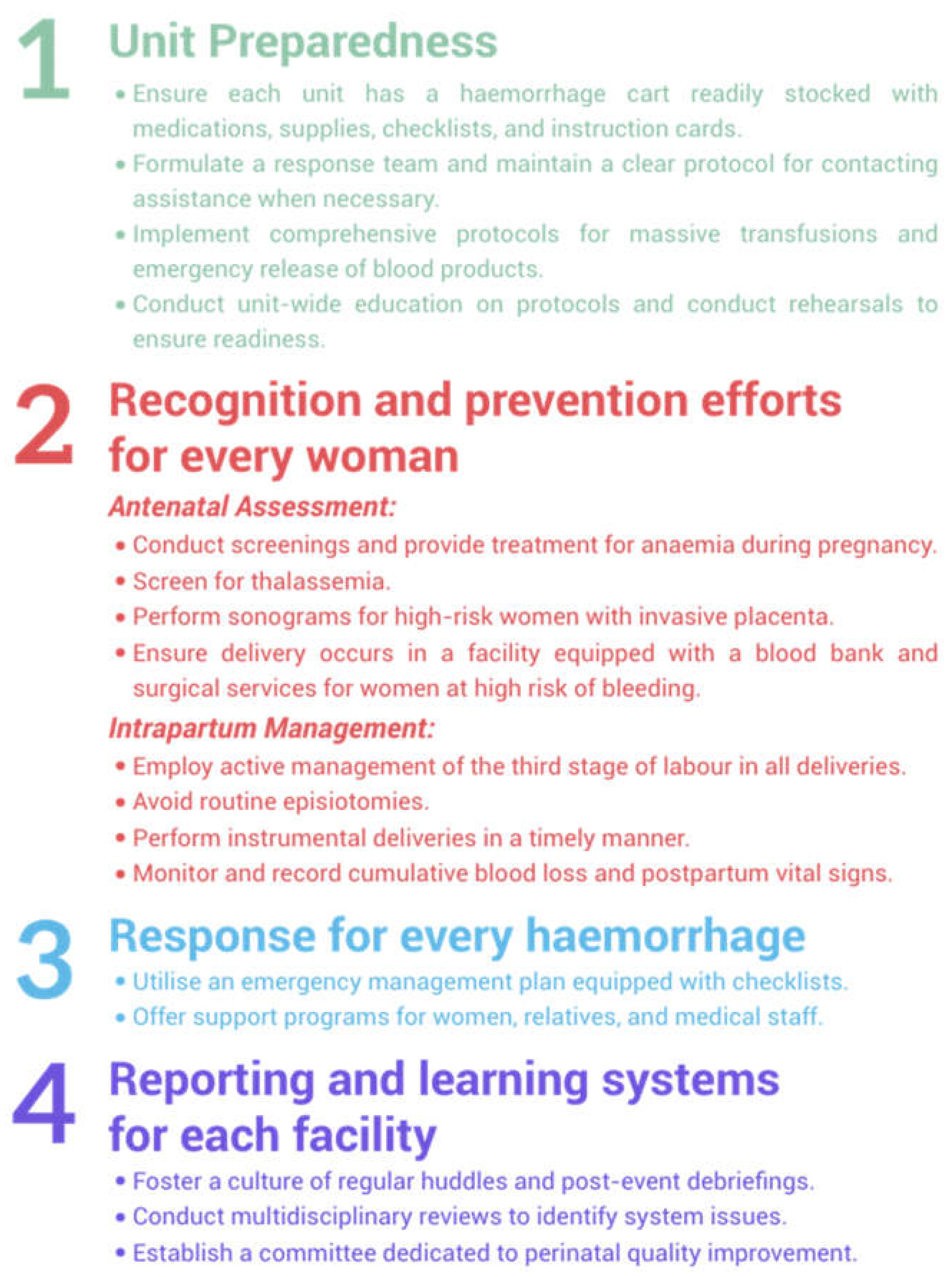

Figure 1.

Suggested strategies to reduce PPH-related morbidity and mortality.

Figure 1.

Suggested strategies to reduce PPH-related morbidity and mortality.

Management of Atonic Uterine

Bimanual uterine massage is typically the first step in dealing with excessive bleeding after childbirth caused by a relaxed uterus [

10,

13,

33]. Its mechanism involves the stimulation of endogenous prostaglandins to evoke uterine contractions. Oxytocin, administered either intravenously or intramuscularly, constitutes the cornerstone of treatment for uterine atony-induced PPH. Typically, oxytocin administration commences concurrently with bimanual uterine massage unless it has been preemptively administered. The intravenous administration of oxytocin typically elicits an immediate uterine response, given its short plasma half-life ranging from one to six minutes [

34]. Other medications, such as methylergonovine maleate, a partially synthetic ergot alkaloid, and intramuscular prostaglandins like carboprost, a 15-methyl analogue of prostaglandin F2α, may serve as alternative pharmaceutical options for managing PPH if initial treatments are ineffective [

13,

33].

In instances where pharmacotherapy proves ineffective in the management of uterine atony, recourse to mechanical interventions, such as balloon tamponade and uterine compression sutures, becomes imperative for potential life-saving outcomes. Notably, balloon tamponade systems, typified by the Bakri balloon, initially described in 2001, involve the intracavitary instillation of fluid (up to a maximum volume of approximately 500 ml) into an intrauterine balloon, with subsequent removal within a 24-hour timeframe post-insertion (or up to 12 hours in several institutions, depending on their local guidelines) [

13,

33,

35]. The utilisation of balloon tamponade in Vietnam has been initiated since the early 2000s and has yielded considerable success. Domestic studies conducted by local authors have elucidated the efficacy and safety of enhanced tamponade balloon variants (such as condom balloons and Foley catheter balloons), reportedly exceeding 90% [

16,

36,

37,

38]. Nguyen Xuan Vu and colleagues at Hung Vuong Hospital have undertaken refinements and implemented dual Foley catheter balloons since 2017, with outcomes demonstrating the promising utility of this approach in mitigating PPH [

16]. In addition, various uterine tamponade devices such as Ellavi® balloon and suction tube uterine tamponade (STUT) are undergoing a clinical trial at Hung Vuong Hospital and Tu Du Hospital, showing initial promising outcomes.

Uterine compression sutures, colloquially termed ‘brace sutures’, were pioneered by B-Lynch and colleagues in 1997, demonstrating remarkable efficacy in stemming PPH [

29]. Since their inception, subsequent to 1997, diverse compression suture methodologies have been delineated. While certain techniques involve sutures penetrating the uterine cavity that potentially elevate the risk of uterine adhesions, alternative techniques obviate such concerns. Combined results from multiple systematic reviews of case series have emphasised that ‘brace sutures’ achieve a success rate exceeding 90% in the treatment of PPH [

39]. Despite widespread adoption of this technique nationwide, research indicates that its efficacy, as well as potential complications, remain considerably limited.

In instances of severe PPH refractory to pharmacological, compressive, or tamponade interventions, surgical approaches emerge as potentially life-preserving measures [

31]. Bilateral uterine artery ligation, typically performed during laparotomy and currently implemented at referral maternity hospitals across the country, represents a customary next course of action. Originally delineated by Waters in 1952 and subsequently refined by O'Leary and O'Leary in 1966 [

40,

41], this surgical manoeuvre entails the suture ligation of uterine vessels along the lateral aspect of the lower uterine segment. Internal iliac artery ligation, introduced by Burchell et al. in 1964 for managing PPH, represents a final recourse, albeit with a success rate ranging from 50% to 60%. However, its utilisation has diminished due to the extensive surgical dissection it necessitates [

42]. Total or supracervical hysterectomy may be indispensable in stemming PPH and preserving life [

19,

24].

Management of Lacerations with or without Episiotomy

A thorough examination of the lower genital tract for cervical, vaginal, perineal, or rectovaginal lacerations is imperative in the management of PPH. Timely identification of such lacerations is crucial, as prompt repair using absorbable sutures can mitigate the risk of complications and facilitate optimal healing. However, the utility of routine antibiotic prophylaxis following uterine examination for PPH or repair of perineal lacerations remains uncertain due to insufficient evidence supporting its efficacy [

31]. While antibiotics are commonly prescribed in clinical practice to prevent infection, particularly in surgical procedures involving the genital tract, the decision to administer prophylactic antibiotics should be made judiciously, considering the balance between potential benefits and risks, as well as local antimicrobial resistance patterns [

43]. Further research is warranted to elucidate the optimal approach to antibiotic prophylaxis in the context of PPH and perineal laceration repair. This approach aims to optimise patient outcomes while minimising the risk of antibiotic-related adverse effects and antimicrobial resistance emergence.

Management of Placental Issues

The examination of the placenta post-delivery holds paramount importance in the clinical assessment to exclude the presence of retained placental tissue or a retained succenturiate lobe, the latter representing an aberrant placental structure characterised by the attachment of one or more accessory lobes to the main placental mass via blood vessels. Suspicions of retained placental tissue necessitate prompt intervention, typically involving evacuation through manual exploration or employing a blunt curette guided by ultrasonography. Ultrasonographic imaging exhibits moderate diagnostic accuracy in identifying retained placental tissue, with reported positive and negative predictive values of approximately 58% and 87%, respectively [

31]. Significantly, the occurrence of unusual uterine bleeding leading to the manual removal of the placenta increases the probability of haemorrhage due to an underlying placenta accreta spectrum (PAS) disorder, underscoring the importance of comprehensive placental inspection during the postpartum phase to identify and address related complications promptly.

Recent research has investigated the effects of endometriosis on placental complications; however, further evidence is required to confirm the association between endometriosis and PPH [

44,

45,

46]. While endometriosis is recognised as a risk factor for instrumental and CS deliveries, as well as placenta previa, it has not been found to be associated with PPH [

44,

47]. In Vietnam, the association between endometriosis and PPH has not received sufficient attention. Reports on PPH have not almost mentioned endometriosis as a risk factor or as a determinant of PPH-related maternal outcomes. This reflects a substantial gap in the existing knowledge, underscoring the necessity for more extensive research to examine the potential impact of endometriosis on PPH in the Vietnamese context.

The incidence of peripartum hysterectomy for managing PPH due to PAS disorders parallels increasing CS rates. While the optimal timing of delivery remains uncertain, recommendations from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) suggest CS between 34 to 35 weeks six days, while the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) proposes delivery between 35 to 36 weeks six days of gestation for PAS disorders [

22,

48]. Caesarean hysterectomy, a complex procedure, requires collaboration among obstetricians, gynaecologists, and surgical specialities to minimise maternal morbidity and mortality. Preoperative interventions, like ureteral stenting and internal iliac artery balloon catheter placement, aim to reduce injury and intraoperative bleeding risks. While immediate hysterectomy is the standard treatment, selective cases may benefit from expectant management followed by delayed hysterectomy to mitigate bleeding and reduce transfusion needs. A midline vertical incision is preferred in planned cesarean hysterectomies for optimal visualisation and bleeding control.

Management of Blood Transfusion

The initiation of blood transfusion in cases of PPH lacks strict criteria; however, transfusion observed in clinical practice commonly commences when estimated blood loss surpasses 1000 ml or when hemodynamic instability ensues [

33]. Therapeutic objectives aim to sustain haemoglobin levels above 8g per deciliter, fibrinogen levels above 2g per litre, platelet counts exceeding 50,000 per microliter, and activated partial thromboplastin and prothrombin times below 1.5 times the normal values, aligning with practical guidelines currently implemented in most Vietnamese institutions such as those established by the British Committee for Standards in Haematology [

49].

Management of Uterine Inversion

Uterine inversion, characterised by the protrusion of the uterus through the vaginal orifice during delivery, presents a significant obstetric complication associated with PPH and hypotension, potentially disproportionate to the actual blood loss. Timely intervention is critical, with immediate manual repositioning of the uterus while preserving the placenta in situ serving as the initial management approach. In cases where manual replacement proves ineffective, the utilisation of tocolytic agents, such as magnesium sulfate, nitroglycerin, or terbutaline, is considered a suitable adjunctive measure to relax the uterine musculature [

50]. Should these interventions fail to achieve successful repositioning, surgical intervention via laparotomy becomes imperative. Following successful repositioning, the administration of uterotonic agents facilitates uterine contraction, while manual placental extraction may be undertaken to mitigate further complications.

PPH Complications

In the immediate postpartum period, PPH presents a spectrum of complications, ranging from hypovolemic shock due to substantial blood loss to disseminated intravascular coagulopathy, acute renal failure, and hepatic dysfunction [

22]. Moreover, the potential sequelae of blood transfusions, including transfusion-related acute lung injury, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and transfusion-associated circulatory overload, underscore the complexity and gravity of this obstetric emergency. Late complications, such as Sheehan’s syndrome, characterised by pituitary necrosis and subsequent panhypopituitarism, along with infertility, further accentuate the multifaceted nature of PPH [

22]. Given the diverse array of complications that may ensue, it is paramount to promptly and effectively manage PPH to mitigate the risk of adverse outcomes and long-term sequelae.

Conclusion

PPH remains a significant global health concern. Vietnam, with its unique sociodemographic and healthcare landscape, has made strides in reducing maternal mortality rates, yet PPH-related maternal deaths persist. The review of existing literature highlights the complexities surrounding PPH definitions, epidemiology, risk factors, prevention, and management strategies within the Vietnamese context. Discrepancies in prevalence rates across regions underscore the need for tailored interventions and policies. Understanding the specific challenges and opportunities related to PPH in Vietnam is crucial for informing evidence-based interventions and policies to improve maternal health outcomes. Future research and policy development should focus on addressing these gaps to mitigate the burden of PPH and contribute to global efforts aimed at reducing maternal mortality.

References

- Say L, Chou D, Gemmill A, Tunçalp Ö, Moller AB, Daniels J, et al. Global causes of maternal death: a WHO systematic analysis. The Lancet Global Health. 2014 Jun 1;2(6):e323–33. [CrossRef]

- Lalonde A, FIGO Safe Motherhood and Newborn Health (SMNH) Committee. Prevention and treatment of postpartum hemorrhage in low-resource settings. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 2012;117(2):108–18. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Recommendations for the Prevention and Treatment of Postpartum Haemorrhage. Geneva; 2012. (WHO Guidelines Approved by the Guidelines Review Committee).

- Tsu VD, Mai TTP, Nguyen YH, Luu HTT. Reducing postpartum hemorrhage in Vietnam: Assessing the effectiveness of active management of third-stage labor. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research. 2006;32(5):489–96. [CrossRef]

- Chi B. Translating clinical management into an effective public health response for postpartum haemorrhage. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2015;122(2):211–211. [CrossRef]

- Weeks A. The prevention and treatment of postpartum haemorrhage: what do we know, and where do we go to next? BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2015;122(2):202–10. [CrossRef]

- Ford JB, Patterson JA, Seeho SKM, Roberts CL. Trends and outcomes of postpartum haemorrhage, 2003-2011. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2015 Dec 15;15(1):334. [CrossRef]

- Knight M, Callaghan WM, Berg C, Alexander S, Bouvier-Colle MH, Ford JB, et al. Trends in postpartum hemorrhage in high resource countries: a review and recommendations from the International Postpartum Hemorrhage Collaborative Group. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2009 Nov 27;9(1):55. [CrossRef]

- Giel van Stralen, von Schmidt Auf Altenstadt JF, Bloemenkamp KWM, van Roosmalen J, Hukkelhoven CWPM. Increasing incidence of postpartum hemorrhage: the Dutch piece of the puzzle. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2016 Oct;95(10):1104–10. [CrossRef]

- The Ministry of Health. Guidelines for obstetrics and gynecology. 2016.

- Pacific World Health Organization Regional Office for the Western. Maternal mortality in Viet Nam, 2000-2001 : an in-depth analysis of causes and determinants. WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific; 2005.

- Trần DC, Phạm DD, Nguyễn THL, Phạm VC, Trịnh TTH, Hoàng TN, et al. Understanding maternal mortality and associated factors in 31 Northern provinces for 2019 - 2021. 1. 2022 Oct 6;20(3):16–20. [CrossRef]

- Tu Du hospital. Protocol for obstetrics and gynecology practices. 2019.

- Ngô ĐT. Study on postpartum hemorrhage situation at Hanoi Obstetrics and Gynecology Hospital. 2022.

- Nguyễn CT. Study on management of post-partum hemorrhage through vagina at National hospital of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Journal of community medicine. 2020;60:150–5.

- Nguyễn XV. Modifier foley sonde dual-ballon tamponade in the treatment of postpartum hemorrahge with uterine atony. Ho Chi Minh City Journal of Medicine. 2022;26-No 1: 106-111.

- Bùi ĐLH, Phạm VT, Lê QT. Emergency peripartum hysterectomy for severe postpartum hemorrhage following vaginal delivery at Tu Du hospital. Vietnam Medical Journal. 2021 Mar 10;498(1). [CrossRef]

- Nguyễn DÁ, Nguyễn ĐQ. Factors related to early postpartum hemorrhage after vaginal birth at hanoi obstetrics & gynecology hospital. Vietnam Medical Journal. 2021 Dec;509(2).

- Nguyễn ĐQ. Study on postpartum hemorrhage 24 hours after vaginal delivery at Hanoi obstetrics and gynecology in 2019 - 2020 [Master thesis]. Hanoi University of Medicine; 2021.

- Hoàng TT, Lưu VD, Phạm VT Cáp Minh Đức,. Obstetric complications at Nghe An obstetrics and pediatrics hospital in 2019 - 2020. Journal of Preventive Medicine [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2024 Apr 18];32(1). Available from: https://vjpm.vn/index.php/vjpm/article/view/552.

- Võ TMD, Trương QV. Postpartum hemorrhage at Ninh Thuan General Hospital: causes and treatment results. 1. 2022;20(4):50–5. [CrossRef]

- Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics. Practice Bulletin No. 183: Postpartum Hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Oct;130(4):e168–86. [CrossRef]

- Phạm TH. Risk factors of postpartum hemorrhage at TuDu hospital. 2008; Available from: https://www.tudu.com.vn/cache/1841259_YeutonguycoBHSS.pdf.

- Nguyễn AT. Postpartum Hemorrhage situation at Hanoi Obstetrics and Gynecology [Thesis]. Hanoi University of Medicine; 2020.

- Iyengar K. Early Postpartum Maternal Morbidity among Rural Women of Rajasthan, India: A Community-based Study. J Health Popul Nutr. 2012 Jun;30(2):213–25.

- Main EK, Goffman D, Scavone BM, Low LK, Bingham D, Fontaine PL, et al. National Partnership for Maternal Safety: Consensus Bundle on Obstetric Hemorrhage. Anesthesia & Analgesia. 2015 Jul;121(1):142. [CrossRef]

- Nguyễn GĐ. Risk factors related to postpartum hemorrhage due to uterine atony and the effectiveness of treatment with intrauterine balloon tamponade. Hue University of medicine and pharmacy. 2020;Summary of medical doctoral thesis.

- Begley CM, Gyte GM, Devane D, McGuire W, Weeks A, Biesty LM. Active versus expectant management for women in the third stage of labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019 Feb 13;2(2):CD007412. [CrossRef]

- Hofmeyr GJ, Mshweshwe NT, Gülmezoglu AM. Controlled cord traction for the third stage of labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Jan 29;1(1):CD008020. [CrossRef]

- Cho HY, Na S, Kim MD, Park I, Kim HO, Kim YH, et al. Implementation of a multidisciplinary clinical pathway for the management of postpartum hemorrhage: a retrospective study. Int J Qual Health Care. 2015 Dec;27(6):459–65. [CrossRef]

- Bienstock JL, Eke AC, Hueppchen NA. Postpartum Hemorrhage. N Engl J Med. 2021 Apr 29;384(17):1635–45. [CrossRef]

- Gerdessen L, Meybohm P, Choorapoikayil S, Herrmann E, Taeuber I, Neef V, et al. Comparison of common perioperative blood loss estimation techniques: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Monit Comput. 2021;35(2):245–58. [CrossRef]

- Hung Vuong hospital. Protocol for obstetrics and gynecology practices. Vol. 1. 2020.

- Butwick AJ, Carvalho B, Blumenfeld YJ, El-Sayed YY, Nelson LM, Bateman BT. Second-line uterotonics and the risk of hemorrhage-related morbidity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015 May;212(5):642.e1-7. [CrossRef]

- Bakri YN, Amri A, Abdul Jabbar F. Tamponade-balloon for obstetrical bleeding. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2001 Aug;74(2):139–42. [CrossRef]

- Trần TL, Nguyễn TMT. To efficacy of uterine balloon tamponade in postpartum hemorrhage. Ho Chi Minh City Journal of Medicine. 2009;13(1):32–8.

- Tuấn LC, Tuyến NĐ, Thuận ĐN, Mnih NX, Sáu NV, Quyên LTT, et al. Efficacy of balloon tamponade using foley’s catheter in the management of postpartum haemorrhage. 1. 2019 Sep 1;17(1):28–35. [CrossRef]

- Tam HX, Xuân TTH, Mai NNH. To evaluate the effectiveness of balloon tamponade in preventing and treating postpartum haemorrhage at Phu Yen obstetrics and paediatrics hospital in 2013. 1. 2014 Apr 1;12(1):50–3.

- Matsubara S, Yano H, Ohkuchi A, Kuwata T, Usui R, Suzuki M. Uterine compression sutures for postpartum hemorrhage: an overview. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2013 Apr;92(4):378–85. [CrossRef]

- Waters EG. Surgical management of postpartum hemorrhage with particular reference to ligation of uterine arteries. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 1952 Nov 1;64(5):1143–8. [CrossRef]

- O’Leary JL, O’Leary JA. Uterine artery ligation in the control of intractable postpartum hemorrhage. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1966 Apr 1;94(7):920–4. [CrossRef]

- Joshi VM, Otiv SR, Majumder R, Nikam YA, Shrivastava M. Internal iliac artery ligation for arresting postpartum haemorrhage. BJOG. 2007 Mar;114(3):356–61. [CrossRef]

- ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 120. Use of prophylactic antibiotics in labor and delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2011 Jun;117(6):1472–83. [CrossRef]

- Matsuzaki S, Nagase Y, Ueda Y, Lee M, Matsuzaki S, Maeda M, et al. The association of endometriosis with placenta previa and postpartum hemorrhage: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2021 Sep;3(5):100417. [CrossRef]

- Shmueli A, Salman L, Hiersch L, Ashwal E, Hadar E, Wiznitzer A, et al. Obstetrical and neonatal outcomes of pregnancies complicated by endometriosis. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2019 Mar;32(5):845–50. [CrossRef]

- Yi KW, Cho GJ, Park K, Han SW, Shin JH, Kim T, et al. Endometriosis Is Associated with Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes: a National Population-Based Study. Reprod Sci. 2020 May;27(5):1175–80. [CrossRef]

- Nagase Y, Matsuzaki S, Ueda Y, Kakuda M, Kakuda S, Sakaguchi H, et al. Association between Endometriosis and Delivery Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Biomedicines. 2022 Feb 17;10(2):478. [CrossRef]

- Jauniaux E, Alfirevic Z, Bhide AG, Belfort MA, Burton GJ, Collins SL, et al. Placenta Praevia and Placenta Accreta: Diagnosis and Management: Green-top Guideline No. 27a. BJOG. 2019 Jan;126(1):e1–48. [CrossRef]

- Hunt BJ, Allard S, Keeling D, Norfolk D, Stanworth SJ, Pendry K, et al. A practical guideline for the haematological management of major haemorrhage. Br J Haematol. 2015 Sep;170(6):788–803. [CrossRef]

- Vijayaraghavan R, Sujatha Y. Acute postpartum uterine inversion with haemorrhagic shock: laparoscopic reduction: a new method of management? BJOG. 2006 Sep;113(9):1100–2. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).