Submitted:

05 June 2024

Posted:

07 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Questionnaire Data Collection

2.3. Focus Group and Interview Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Reach

3.2. Effectiveness

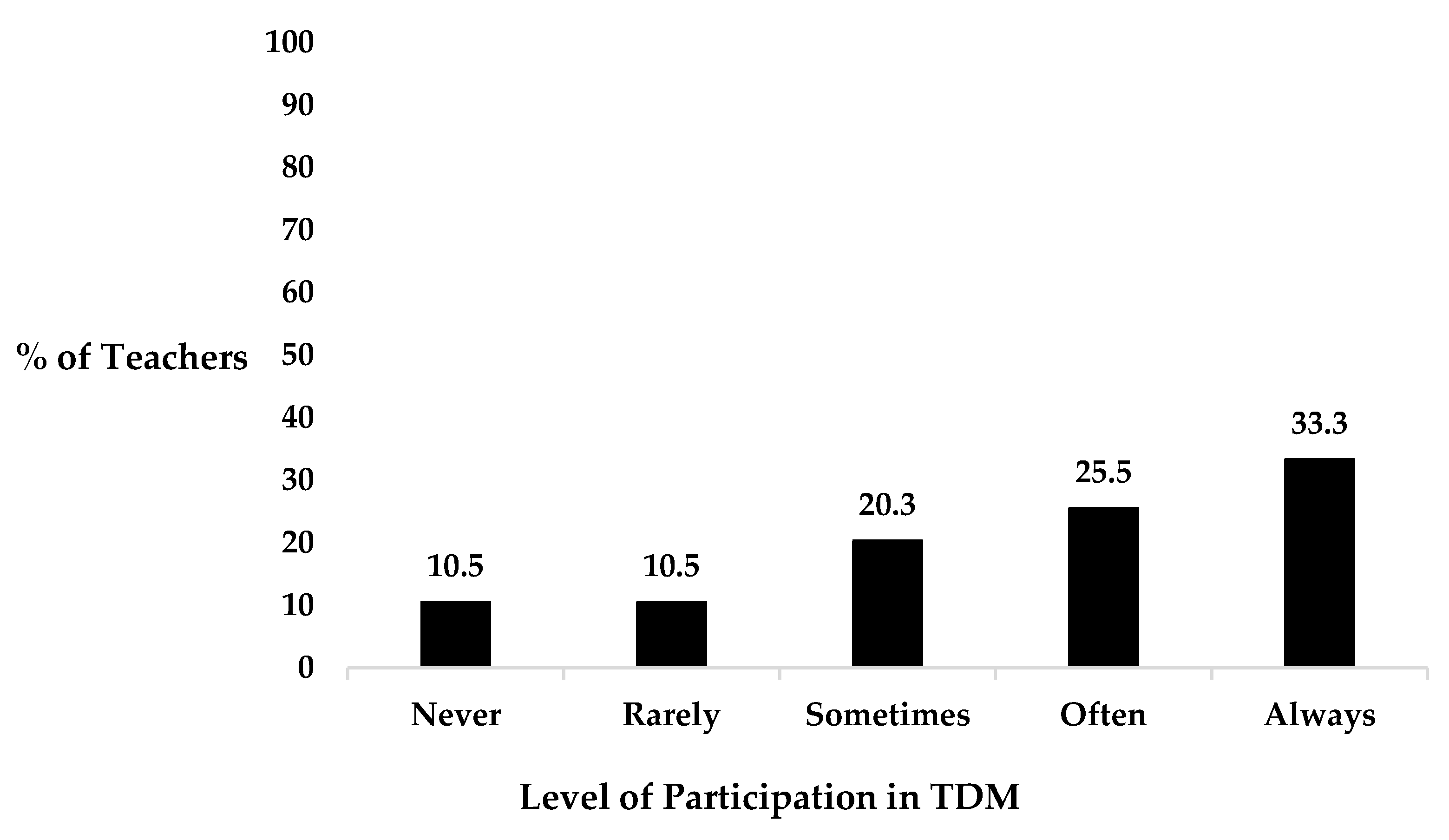

3.3. Adoption

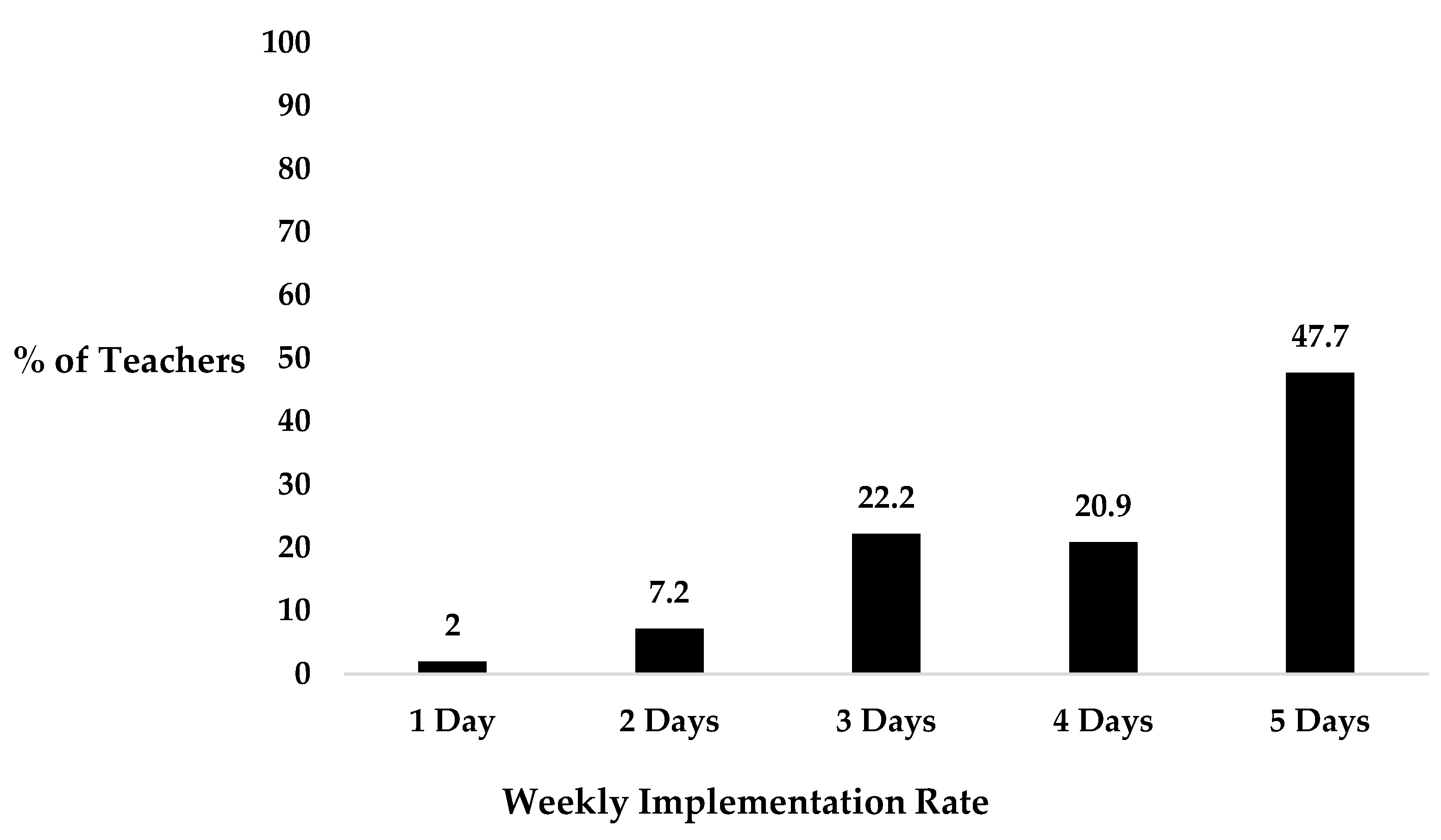

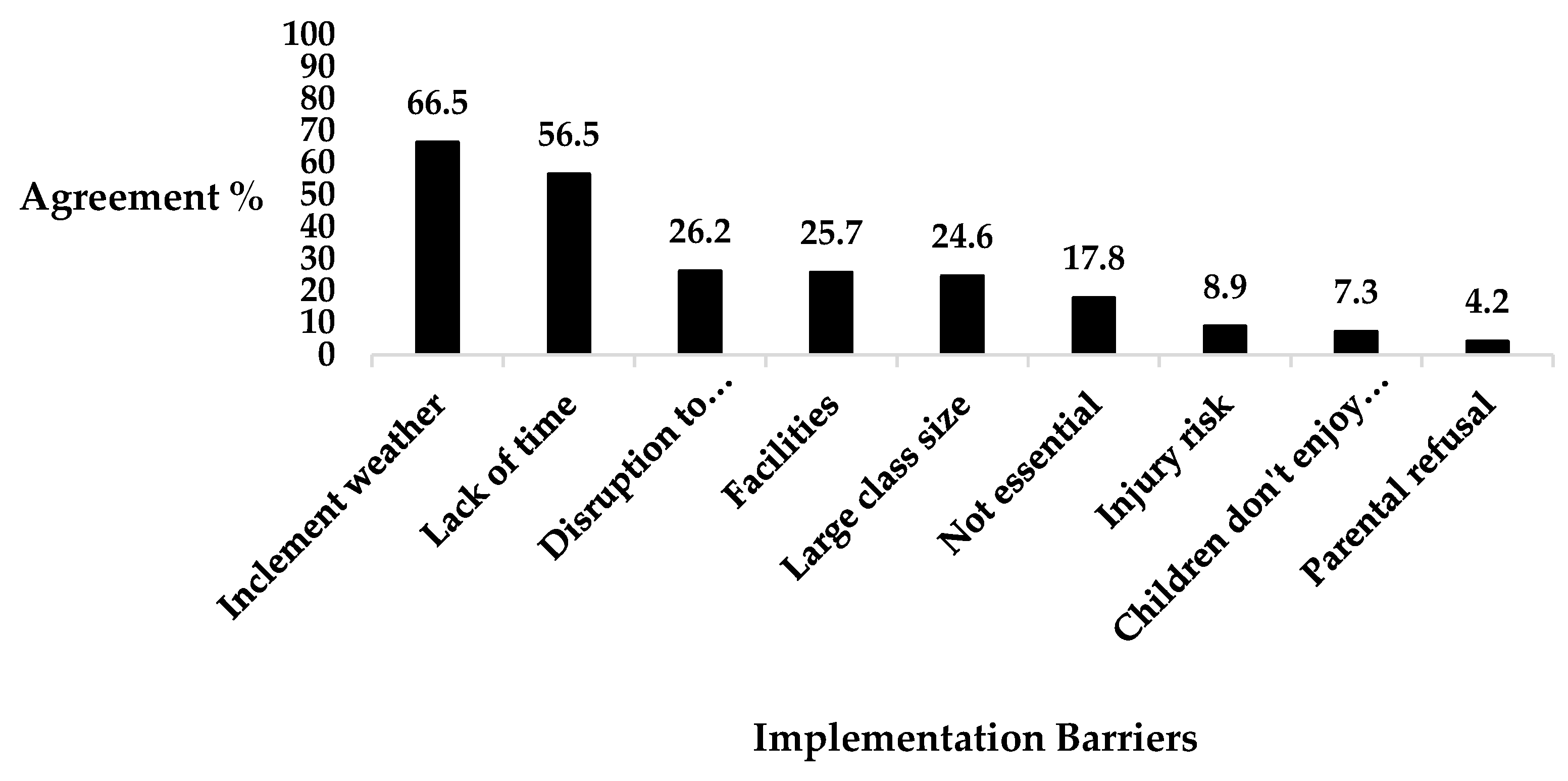

3.4. Implementation

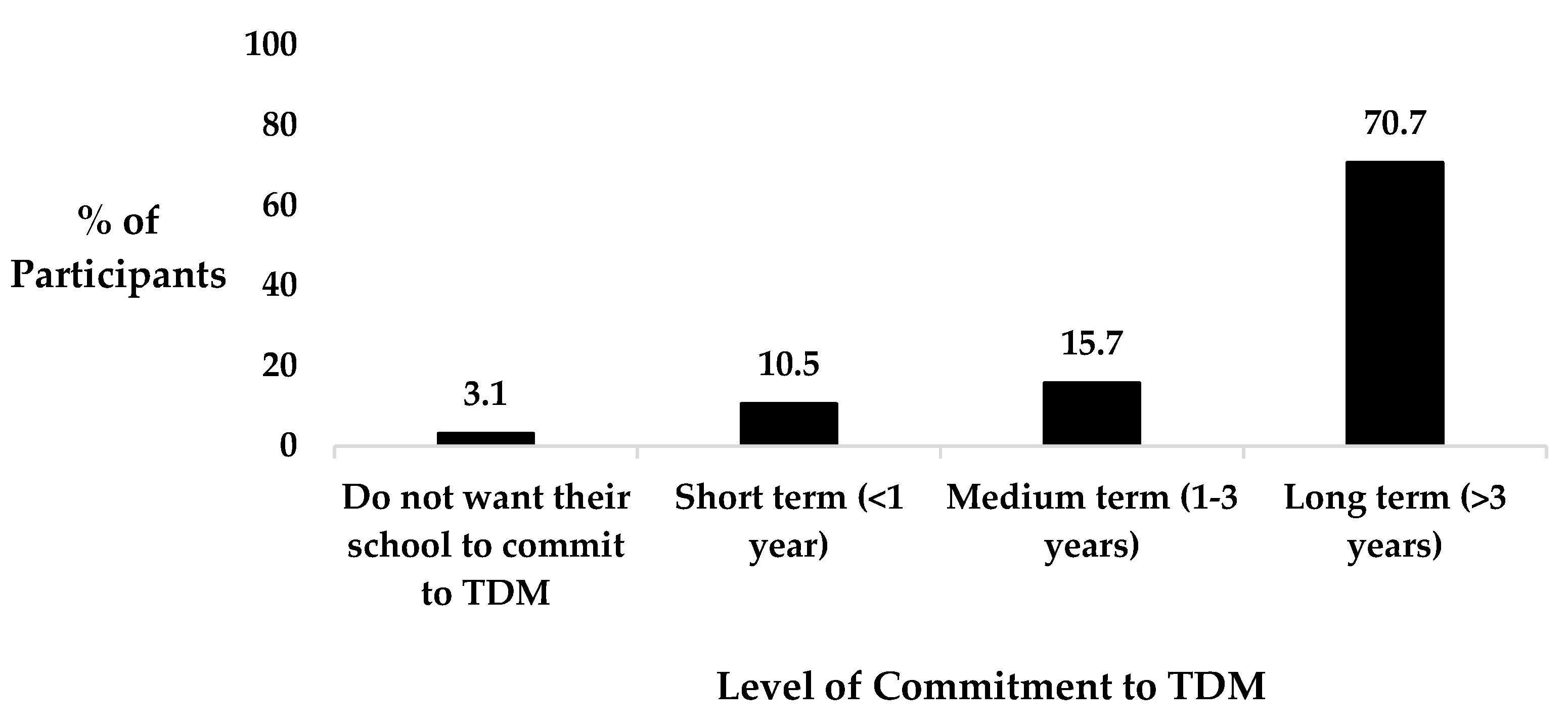

3.5. Maintenance

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Woods, C.B.; NG, K.W.; Britton, U.; McCelland, J.; O’Keefe, B.; Sheikhi, A.; McFlynn, P.; Murphy, M.H.; Goss, H.; Behan, S.; Philpott, C.; Lester, D.; Adamakis, M.; Costa, J.; Coppinger, T.; Connolly, S.; Belton, S.; O’Brien, W. The Children’s Sport Participation and Physical Activity Study 2022 (CSPPA 2022). Limerick, Ireland: Physical Activity for Health Research Centre, Department of Physical Education and Sport Sciences, University of Limerick; Dublin, Ireland: Sport Ireland and Healthy Ireland; Belfast, Northern Ireland: Sport Northern Ireland. Published 2023. [CrossRef]

- Glasgow, R.E.; Vogt, T.M.; Boles, S.M. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. Am J Public Health 1999, 89, 1322–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohl III, H.W.; Cook, H.D. Educating the student body: Taking physical activity and physical education to school. The National Academies Press: Washington DC, USA, 2013.

- Wyszyńska, J.; Ring-Dimitriou, S.; Thivel, D.; Weghuber, D.; Hadjipanayis, A.; Grossman, Z.; Ross-Russell, R.; Dereń, K.; Mazur, A. Physical activity in the prevention of childhood obesity: the position of the European childhood obesity group and the European academy of pediatrics. Front Pediatr. 2020, 8, 535705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loprinzi, P.D.; Cardinal, B.J.; Loprinzi, K.L.; Lee, H. Benefits and environmental determinants of physical activity in children and adolescents. Obes Facts. 2012, 5, 597–610. http://dx.doi.org/10.1159%2F000342684. [Google Scholar]

- Health Service Executive (HSE). Physical Activity Guidelines. Available online: https://www.hse.ie/eng/about/who/healthwellbeing/our-priority-programmes/heal/physical-activity-guidelines/ (accessed on 10th November 2023).

- World Health Organisation (WHO). Physical Activity. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/physical-activity. (accessed on 1st February 2022).

- Woods, C.B.; Powell, C.; Saunders, J.A.; O’Brien, W.; Murphy, M.H.; Duff, C.; Farmer, O.; Johnston, A.; Connolly, S. ; Belton., S. (2018). The Children’s Sport Participation and Physical Activity Study 2018 (CSPPA 2018). Department of Physical Education and Sport Sciences, University of Limerick, Limerick, Ireland, Sport Ireland, and Healthy Ireland, Dublin, Ireland and Sport Northern Ireland, Belfast, Northern Ireland. Published 2018, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Citizens Information. Starting School. Available online: https://www.citizensinformation.ie/en/education/primary_and_post_primary_education/going_to_primary_school/primary_education_life_event.html#:~:text=Your%20child%20in%20school,around%2011am%20and%2012.30pm. (accessed on 10th August 2023).

- Naylor, P.J.; Nettleford, L.; Race, D.; Hoy, C.; Ashe, M.C.; Wharf Higgins, J.; McKay, H.A. Implementation of school based physical activity interventions: A systematic review. J Prev Med. 2015, 72, 95–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryde, G.C.; Booth, J.N.; Brooks, N.E.; Chesham, R.A.; Moran, C.N.; Gorely, T. The Daily Mile: What factors are associated with its implementation success? Plos One. 2018, 13, e0204988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Daily Mile Foundation. Starting School. Available online: https://thedailymile.ie/ (accessed on 5th November 2022).

- Booth, J.N.; Chesham, R.A.; Brooks, N.E.; Gorely, T.; Moran, C.N. A Citizen Science study of short physical activity breaks at school: improvements in cognition and wellbeing with self-paced activity. BMC Med. 2020, 18, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brustio, P.R.; Mulasso, A.; Lupo, C.; Massasso, A.; Rainoldi, A.; Boccia, G. The Daily Mile is able to improve cardiorespiratory fitness when practiced three times a week. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020, 17, 2095–2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brustio, P.R.; Mulasso, A.; Marasso, D.; Ruffa, C.; Ballatore, A.; Moisè, P.; Lupo, C.; Rainoldi, A.; Boccia, G. The Daily Mile: 15 minutes running improves the physical fitness of Italian primary school children. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019, 16, 3921–3933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesham, R.A.; Booth, J.N.; Sweeney, E.L.; Ryde, G.C.; Gorely, T.; Brooks, N.E.; Moran, C.N. The Daily Mile makes primary school children more active, less sedentary and improves their fitness and body composition: a quasi-experimental pilot study. BMC Med. 2018, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jonge, M.; Slot-Heijs, J.J.; Prins, R.G.; Singh, A.S. The effect of The Daily Mile on primary school children’s aerobic fitness levels after 12 weeks: a controlled trial. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020, 17, 2198–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, J.; Milnes, L.J.; Mountain, G. How ‘The Daily MileTM’ works in practice: A process evaluation in a UK primary school. J Child Health Care. 2020, 24, 544–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatch, L.M.; Williams, R.A.; Dring, K.J.; Sunderland, C.; Nevill, M.E.; Cooper,S. B. Activity patterns of primary school children during participation in The Daily Mile. Sci Rep. 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatch, L.M.; Williams, R.A.; Dring, K.J.; Sunderland, C.; Nevill, M.E.; Sarkar, M.; Morris, J.G.; Cooper, S.B. The Daily MileTM: Acute effects on children’s cognitive function and factors affecting their enjoyment. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2021, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchant, E.; Todd, C.; Stratton, G.; Brophy, S. The Daily Mile: Whole-school recommendations for implementation and sustainability. A mixed-methods study. PloS One. 2020, 15, e0228149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, J.L.; Daly-Smith, A.; Archbold, V.S.J.; Wilkins, E.L.; McKenna, J. The Daily MileTM initiative: Exploring physical activity and the acute effects on executive function and academic performance in primary school children. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2019, 45, 101583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breheny, K.; Passmore, S.; Adab, P.; Martin, J.; Hemming, K.; Lancashire, E.R.; Frew, E. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of The Daily Mile on childhood weight outcomes and wellbeing: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Int J Obes. 2020, 44, 812–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herold, F.; Müller, P.; Gronwald, T.; Müller, N.G. Dose–response matters! – perspective on the exercise prescription in exercise–cognition research. Front Psychol. 2019, 10, 2338–2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowbotham, S.; Conte, K.; Hawe, P. Variation in the operationalisation of dose in implementation of health promotion interventions: insights and recommendations from a scoping review. Implement Sci. 2019, 14, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanckel, B.; Ruta, D.; Scott, G.; Peacock, J.L.; Green, J. The Daily Mile as a public health intervention: a rapid ethnographic assessment of uptake and implementation in South London, UK. BMC Public Health. 2019, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malden, S.; Doi, L. The Daily Mile: teachers’ perspectives of the barriers and facilitators to the delivery of a school-based physical activity intervention. BMJ Open. 2019, 9, e027169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Routen, A.; Aguado, M.G.; O’Connell, S.; Harrington, D. The Daily Mile in practice: implementation and adaptation of the school running programme in a multiethnic city in the UK. BMJ Open. 2021, 11, e046655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Department of Education. DEIS: Delivering equality of opportunity in school. Available online: https://www.education.ie/en/schools-colleges/services/deis-delivering-equality-of-opportunity-in-schools-/ (accessed on 12th August 2023).

- Ory, M.G.; Mier, N.; Sharkey, J.R.; Anderson, L.A. Translating science into public health practice: Lessons from physical activity interventions. Alzheimer’s & Dement. 2007, 3, S52–S57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaglio, B.; Shoup, J.A.; Glasgow, R.E. The RE-AIM Framework: A systematic review of use over time. Am J Public Health. 2013, 103, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Austin, G.; Bell, T.; Caperchione, C.; Mummery, W.K. Translating research to practice. Health Promot Pract. 2011, 12, 932–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Meij, J.S.B.; Chinapaw, M.J.M.; Kremers, S.P.J.; Van der wal, M.F.; Jurg, M.E.; Van Mechelen. Promoting physical activity in children: the stepwise development of the primary school-based JUMP-in intervention applying the RE-AIM evaluation framework. Br J Sports Med. 2010, 44, 879–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janssen, M.; Toussaint, H.M.; van Mechelen, W.; Verhagen, E.A.L.M. Translating the PLAYgrounds program into practice: A process evaluation using the RE-AIM framework. J Sci Med Sport. 2013, 16, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Leary, M.; Rush, E.; Lacey, S.; Burns, C.; Coppinger, T. Project Spraoi: two year outcomes of a whole school physical activity and nutrition intervention using the RE-AIM framework. Ir Educ Stud. 2019, 38, 219–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smedegaard, S.; Brondeel, R.; Christiansen, L.B.; Skovgaard, T. What happened in the ‘Move for Well-being in School’: a process evaluation of a cluster randomized physical activity intervention using the RE-AIM framework. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2017, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, C. Home Page – LimeSurvey – Easy Online Survey Tool. Available online: https://www.limesurvey.org/. (accessed on 18th January 2022).

- Central Statistics Office. Area type classification by small area 2016. Available online: http://census.cso.ie/urlimap11/ (accessed on 9th August 2021).

- World Health Orginisation. Coronavirus disease (COVID19): How is it transmitted? Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/coronavirus-disease-covid-19-how-is-it-transmitted. (accessed on 17th January 2022).

- Williams, T.; Wetton, N.; Moon, A. A way in: five key areas of health education. Health Education Authority: London, England, 1989.

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Education. Teacher statistics. Available online: https://www.education.ie/en/Publications/Statistics/teacher-statistics/ (accessed on 12th August 2021).

- School Days. Find primary schools in Ireland by county. Available online: https://www.schooldays.ie/articles/primary-schools-in-ireland-by-county. (accessed on 10th August 2022).

- Cassar, S.; Salmon, J.; Timperio, A.; Naylor, P.J.; Van Nassau, F.; Ayala, A.M.C.; Koorts, H. Adoption, implementation and sustainability of school-based physical activity and sedentary behaviour interventions in real-world settings: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2019, 16, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durlak, J.A.; DuPre, E.P. Implementation matters: A review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. Am J Community Psychol. 2008, 41, 327–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herlitz, L.; MacIntyre, H.; Osbom, T.; Bonell, C. The sustainability of public health interventions in schools: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2020, 15, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loucaides, C.A.; Chedzoy, S.M.; Bennett, N. Differences in physical activity levels between urban and rural school children in Cyprus. Health Educ Res. 2004, 19, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carroll, C.; Patterson, M.; Wood, S.; Booth, A.; Rick, J.; Balain, S. A conceptual framework for implementation fidelity. Implement Sci. 2007, 2, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Occupation | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Walking Principal | 11 | 5.8 |

| Teaching Principal | 21 | 11 |

| Walking Vice-Principal | 0 | 0 |

| Teaching Vice-Principal | 20 | 10.5 |

| Class Teacher | 112 | 58.6 |

| Resource Teacher | 16 | 8.4 |

| Special Needs Assistant | 3 | 1.6 |

| Other* | 8 | 4.2 |

| Perceived Benefits of The Daily Mile (TDM) | Strongly Disagree or Disagree (%) | Undecided (%) | Strongly Agree or Agree (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positively impacts children’s health and wellbeing | 4.2% | 4.2% | 91.6% |

| Positively impacts children’s attitudes towards physical activity (PA) | 4.2% | 4.7% | 91.1% |

| Positively impacts children’s participation in PA | 4.2% | 11.5% | 84.3% |

| Positively impacts children’s physical fitness | 4.2% | 8.4% | 87.4% |

| Positively impacts children’s movement proficiency | 3.1% | 14.1% | 82.7% |

| Reduces children’s sedentary behaviour during school | 2.1% | 9.4% | 88.5% |

| Increases the opportunity for social interaction between children | 3.7% | 14.7% | 81.7% |

| Positively impacts children’s attentiveness and concentration directly after a TDM session | 3.7% | 14.7% | 81.7% |

| Positively impacts children’s attentiveness and concentration across a school day | 3.7% | 20.4% | 75.9% |

| Sub-theme of Effectiveness | Topic of Quote | Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Physical health | TDM’s impact on less athletic children. | ‘The ones who couldn’t do one lap at the beginning. They’re the ones that are making the most progress’ (teacher, school A). |

| TDM helps to minimise the prevalence of child obesity. | ‘In certain homes, where you may not have the same support or they may not be taking part, this is their exercise. This is what we do every day and when they were missing out on a mile a day, it’s amazing the difference it made to their physical size’ (principal, school B). | |

| Social health | TDM fosters the development of friendships. | ‘There are some people that normally just wouldn’t mix, like you know they would be in different circles or different sports, but sometimes they’re just at that pace, the same pace as someone that’s running and you’d often see them chatting away to each other. It has actually helped to develop a good few friendships’ (teacher, school B). |

| Cognitive health | Classroom impact. | ‘When you’re gone out to the fresh air and you come back in, you’re ready to sit down and start your work again’ (child, school B). |

| Behavioural impact. | ‘Since we brought in TDM, our discipline problems are not huge, but our discipline problems have plummeted’ (principal, school B). |

| Topic of Quote | Quote |

|---|---|

| Differentiated approaches for integrating TDM into teaching schedules. | ‘The teacher decides what time is most appropriate. I don’t think we had to sit down and say is everybody doing TDM? Are we all on board? That never happened at a staff meeting. We said we’re introducing TDM and we’d love everybody to be part of this and that’s exactly what happened. So, there was no formal school policy that we all have to do this now’ (principal, school A). |

| ‘They have a timetable so unless the weather is absolutely shocking, they have their 10-15 minute slot and it starts at about 10:15 in the day and it continues throughout’ (principal, school B). | |

| The role of a TDM coordinator. | ‘If there’s a hassle, if there’s a problem here he’ll come to myself, you know if there’s something huge, but it’s great we work away and thanks be to God we’ve had no issues. You want it to be successful, so if there was a problem [name of coordinator] can work with it’ (principal, school B). |

| The impact of a school’s PA culture and uniform policy. | ‘Everybody is dressed appropriately because we are wearing a school track suit every day at school. We don’t have a formal school uniform. 99% of the children are wearing runners coming to school, you know they’re all wearing appropriate footwear coming to school’ (principal, school A). |

| Sub-themes of implementation | Topic of quote | Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Barriers | Inclement weather and inadequate facilities. | ‘I know when we were doing runs in the grass and stuff like that, when the pitch is out of use there for the months of December November you know, you’re not really running it then’ (teacher, school B). |

| Time constraints associated with a congested curriculum. | ‘It can take a bit of time. You’re talking the bones of 25 minutes, half an hour a day, which is a lot to be giving towards it when you have other items you’re supposed to be covering as well’ (teacher, school A). | |

| TDM’s repetitive nature. | ‘I think it’s good but it’s sort of a repetitive thing to do the same four laps every day of the same pitch. It’s not like other sports like soccer, basketball or hurling where it’s always different each day’ (child, school A). | |

| Facilitators | Social rapport between teachers and children. | ‘You could be chatting away to them as well. I find that’s nice because I find it so busy during the days you don’t get a chance to talk to half of them with stuff that’s going on, and some of them like chatting away to you and jogging away’ (teacher, school B). |

| TDM’s inclusive nature. | ‘What it helped greatly actually was children who may have autism, who may find it hard to take part in games that aren’t organized. Now they’d something to do so, they were going around with a pal or going around with somebody else’ (principal, school B). | |

| Teachers participating in TDM. | ‘Yeah I do it, not every day but maybe half the time I jog around and I tend to stay around the middle or towards the back and kind of give them a bit of a G-up because the other ones at the front are tearing off ahead’ (teacher, school A). | |

| Adapting and varying how TDM is implemented. | ‘Some people have a different twist. Today’s Thursday and there were some classes doing relays. Some of the junior classes might start it off where they’ll just walk and then you can get them jogging you know, walk one and then jog one. The older classes, I’m looking at the sixth class there and there’s some guys in there just doing rounds. Some teachers might tie it in with a homework pass or something like that, you know every so often get your laps up this week, or we do a marathon or something like this and you know every so often, you do have to give an incentive’ (principal, school B). | |

| Addition of a competitive element. | ‘The competitive nature for me. I find a lot of them, like there’s a couple of boys and girls who would be very involved in their sport and they’d be running and they’d be chatting away but they don’t want to finish behind someone else. I know that they enjoy it, but they still take the competitive part of it very seriously as well’ (teacher, school B). |

| Theme of Quote | Quote |

|---|---|

| Prioritising the personal development of each child. | ‘As long as the emphasis is on self-improvement, they won’t get too caught up on who is the fastest or who is the slowest so they’re all making their own improvement. I’ll definitely keep it up’ (teacher, school A). |

| Recognising the benefits of TDM participation. | ‘I think we should keep on participating because even though sometimes when we might not want to run, the fresh air and just running with your friends always helps the mind even if you don’t really feel like running’ (child, school B). |

| Recognition of a school’s TDM commitment. | ‘We’d love to commit to implementing and we’d love to have a daily mile flag outside the school at some point. Maybe there should be some sort of recognition. I know we are involved, and we’re registered but maybe there should be some sort of recognition, somewhere where people say this is a daily mile school’ (principal, school A). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).