1. Introduction

The attachment theory, initially formulated to elucidate the emotional bond between infants and caregivers, has subsequently been broadened to encompass close relationships in adults. Bowlby [

1] defined attachment as the infant’s inclination to seek closeness to a primary caregiver during childhood, with the attachment system maintaining moderate stability into adulthood [

2]. Attachment problems in adults have been associated with couple dissatisfaction and sexual risk behavior [

3]. In one study conducted with an adolescent sample, it was found that higher levels of attachment anxiety and avoidance were predictive of less healthy sexual attitudes. Moreover, elevated levels of attachment avoidance were linked to higher cumulative sexual risk scores, particularly among non-virgin males [

4]. In a more recent study involving adults in their 30s, it was discovered that insecure attachment predicts sexual debut, the number of casual and committed sexual partners, and the likelihood of remaining single in one’s 30s [

5]. Furthermore, another study has demonstrated that excessive sexual behavior is primarily rooted in attachment processes rather than mere behavior; traumatic experiences, along with symptoms of depression, could play a mediating role in hypersexual behavior [

6].

A secure attachment serves as the foundation for a positive self-concept, a healthy sense of trust in others, a readiness to seek help when needed, and effective emotional regulation, all of which contribute to mental well-being and robust interpersonal relationships [

7]. Conversely, insecure attachments are marked by challenges in emotional and interpersonal regulation, predisposing individuals to enduring psychological distress [

2,

6,

8], lower sexual satisfaction [

9,

10], lower marital satisfaction [

9]; and infidelity [

11].

Regarding couple satisfaction, one meta-analysis confirmed in 132 studies that higher levels of attachment avoidance and anxiety were associated with lower personal relationship satisfaction and a lower level of partner relationship satisfaction [

12]. Even some couple therapy aims to decrease attachment anxiety as a result of persistent couple conflict [

13,

14,

15].

Attachment problems have been associated with additional variables, including low self-esteem [

16], heightened depressive symptoms [

6], and diminished interpersonal trust [

17]. In this context, the strong correlation between attachment problems and significant variables such as couple satisfaction, sexual dysfunction, and excessive sexual behavior prompts the current study to explore all these variables together. The aim is to gain a comprehensive understanding of the risk factors for developing hypersexuality.

In order to understand and evaluate the attachment construct, it is crucial to possess and assess the strong psychometric properties of instruments designed to measure it. The Experience in Close Relationships (ECR) scale has been utilized in numerous countries and stands as one of the most employed instruments [

18,

19]. However, in Latin-speaking regions, few studies have utilized the scale [

7,

20,

21], particularly in its abbreviated version. Therefore, one of the aims of our study is to furnish psychometric evidence for the brief version of the ECR with 8 items. In the past decade, numerous studies have provided evidence supporting the practicality of the brief scale [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27].

In the instance of the Couple Satisfaction Index, only a few studies have examined the psychometric properties of the scale within the Latino population [

11], particularly regarding the potential for a brief version. Similarly, to the ECR scale, over the past decade, the CSI-4 version has demonstrated strong psychometric evidence and practical utility [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31].

Considering the evidence linking attachment patterns to various problematic behaviors, the current study has two primary aims. The first aim is to explore the implications of attachment problems (anxiety and avoidance) on sexual risk behavior (such as the number of sexual partners, the use of sexual protection, and the consumption of drugs and alcohol during sexual activity), sexual addiction, psychological distress, sexual satisfaction, and couple satisfaction. The insights gained from these analyses could help validate the interrelationships among these variables and facilitate the development of strategies for early detection of the primary factors associated with the onset of sexual addiction, a highly problematic behavior among emerging adults.

The second aim is to provide evidence of the psychometric properties of the brief versions of the ECR scale and CSI scale within the Latino population. This endeavor seeks to enhance understanding of romantic and sexual behavior in these populations.

2. Materials and Methods

We utilized a cross-sectional design, which was complemented by a snowball sampling strategy. Participants were recruited via online advertisements and were invited to participate in the study through the university’s online social media platforms. All participants were residents of urban areas within cities in Sonora, aged between 18 and 50 years, and possessed adequate literacy skills. In order to be included in the present sample, participants were required to complete all questionnaires.

2.1. Participants

We enrolled 214 adult participants from a pool of 307 individuals who completed all psychological measures. Of these, 104 identified as men (mean age: M = 21.63, SD = 5.66), 103 as women (mean age: M = 21.95, SD = 5.55), four identified with a non-binary gender (mean age: M = 21.75, SD = 5.67), and three did not specify their gender (mean age: M = 22.33, SD = 8.38). In terms of sexual orientation, 72.4% of the sample identified as heterosexual, 3.7% as homosexual, 10.6% as bisexual, 4.1% were unsure of their orientation, and 7.8% did not respond to the question. The average number of years of education was M = 14.20 (SD = 3.93), with a mean monthly income of M = 164.54 USD (SD = 397.48). The marital status of the sample was as follows: 1.8% were married, 97% were single, and 1.2% were in a concubinage arrangement. Among the single participants, 62.1% reported being in a serious and exclusive relationship, 25.5% were not engaged in any form of romantic or sexual relationship, and 9.5% were engaged in non-serious relationships with multiple partners, involving both romantic and sexual experiences.

Participants reported no history of neurological disorders, substance use disorders, or any psychiatric diagnoses. This information was collected from their responses subsequent to providing informed consent. All participants provided written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and did not receive financial compensation for their participation. Participants affirmed their lack of awareness of the study hypotheses. The study protocol received approval from the Institutional Review Board of the Sonora Institute of Technology (ID 178).

2.2. Measures

We developed a website to host the online surveys, which were designed to collect information, including demographic characteristics (e.g., age, years of education, gender, income, neurological and psychiatric diagnoses) and psychological measures.

In addressing the question of sexual behavior, we examined several key factors, including: the age at which individuals engage in sexual activity, the number of sexual partners they have had, their utilization of contraceptives and sexual protection measures, the consumption of alcohol during sexual encounters, and the use of drugs during such interactions. To minimize participant withdrawal from the study, we distributed 232 items across 30 pages, with an anticipated completion time of 30 to 40 minutes.

Sexual Addiction (SAST-R). The latest iteration of the Sexual Addiction Screening Test-Revised includes 20 fundamental items. This 20-item version was selected due to its applicability to heterosexual and homosexual men and women. The confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) employed a five-factor model with a second-order factor, which demonstrated the most robust fit, and the reliability analysis indicated acceptable internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.80) [

32]. This scale categorizes sexual addiction into five dimensions: 1) Affect Disturbance (items 4, 5, 11, 13, and 14), characterized by a significant decrease in mood associated with sexual behaviors; 2) Relationship Disturbance (items 6, 8, and 16), where sexual behavior interferes with intimate relationships; 3) Preoccupation (items 3, 18, 19, and 20), defined by obsessive sexual thoughts; 4) Loss of Control (items 10, 12, 15, and 17), where individuals are unable to regulate their sexual behaviors despite adverse consequences; 5) Associated Features (items 1, 2, 7, and 9), which include traumatic sexual experiences. We used the total score as a unit of analysis.

Experiences in Close Relationships-Revised (ECR-R): The ECR-R is an instrument comprising 36 items, designed to assess two distinct dimensions of adult attachment: Anxiety and Avoidance. Respondents rate their agreement with statements pertaining to their romantic relationship experiences using a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The scale consists of two subscales, each comprising 18 items. Average scores are computed for both Anxiety and Avoidance subscales, with higher scores indicating elevated levels of anxiety or avoidance within relationships. Adequate psychometric properties were observed in a sample of Latino college students, with internal consistency coefficients of .91 for Anxiety and .90 for Avoidance [

21]. As with previous studies, we aim to assess the practicality of the brief scale by contrasting the brief version consisting of 8 items. Each subscale is analyzed as a distinct unit of analysis.

The Couple Satisfaction Index-16, and Index-4 (CSI): The CSI is composed of 16 items intended to assess relationship satisfaction among couples. Each item is rated on a scale ranging from 0 (Always disagree/never/extremely unhappy) to 5 and 6 (Always agree/perfect/all time/complete true). Higher scores are indicative of heightened satisfaction within the couple. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for internal consistency was calculated to be 0.872 in the CSI-4 version [

27]. Additionally, the CSI has demonstrated strong convergent validity with other satisfaction measures and excellent construct validity [

11,

33]. Recent studies have employed a brief four-item version of the scale, demonstrating robust psychometric properties as a measure of general couple satisfaction [

27,

29,

31]. In the current study, we aim to explore the validity of both the 16-item and 4-item versions.

The New Sexual Satisfaction Scale-Short (NSSS-S): The NSSS-S is a 12-item instrument designed to assess global sexual satisfaction, irrespective of gender, sexual orientation, or relationship status. Responses are recorded on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = not at all satisfied, 5 = extremely satisfied). Items 1–6 constitute the individual sexual satisfaction factor, while items 7–12 constitute the interpersonal factor. The instrument demonstrated strong internal reliability, with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of .92 for the overall scale, .88 for the individual subscale, and .87 for the interpersonal subscale [

34]. Each subscale is analyzed as distinct units of analysis.

Symptom Checklist 90 (SCL-90): The SCL-90 is a psychometric instrument consisting of 90 items, each rated on a Likert scale ranging from 0 to 4. It assesses the level of psychological distress experienced by the respondent in the period from the day of evaluation up to one week prior to the application. For seven of the nine dimensions, as well as the Global Severity Index (GSI), Cronbach’s alpha demonstrated internal consistency values greater than .7. Meanwhile, the remaining dimensions registered scores above .66 [

35]. The analysis was conducted using the total score of the instrument, and each subscale was also evaluated as separate units of analysis.

2.3. General Procedures

The translation and adaptation of the original version of the Couple Satisfaction Index-16 for the Mexican context were undertaken by three clinical psychologists specializing in romantic relationships. The retroversion procedure, as outlined in the test translation guidelines, was followed meticulously, involving a native speaker. A pilot study with 50 participants was conducted to ensure that the meaning of the items was clearly understood. During this phase, participants demonstrated a comprehensive understanding of all 16 items. Consequently, this version was retained to maintain its integrity.

Data collection occurred from July 2023 to January 2024. Participants were recruited through online advertisements, and extra credit was offered to psychology students if they invited their relatives. Participants were scheduled and invited to computer classrooms at the university. No personal information was requested during data collection; instead, participants were assigned ID numbers to ensure anonymity. All data was stored on a secure server accessible only to the principal researcher. Prior to commencement, informed consent was obtained from the participants. The survey was initiated only if they agreed to participate; otherwise, no information was collected.

After consenting to participate, the participants completed the psychological measures in the following sequence: demographic information, sexual behavior, ECR-R, CSI, NSSS-S, SAST-R, and SCL-90. On average, participants required approximately 30 to 40 minutes to complete all the surveys.

2.4. Data Analysis

We computed means, standard deviations, and frequencies for all demographic characteristics within the samples to ascertain the suitable statistical tests for examining correlations and intergroup comparisons. Normality assessments were performed, encompassing the Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests. Furthermore, Levene’s test was employed to assess the homogeneity of variances across the five dependent variables. The results of these tests indicated that nonparametric tests would be more appropriate for the data. In order to facilitate comparison among the scales, the z-scores were calculated based on the mean and standard deviation of all participants. We utilized the latest version of GPower software, version 3.1.9.7, to determine the sample size required for a linear multiple regression analysis with α = .05, β = .8, and 5 predictors. The current sample size (n = 214) aligns with the analysis conducted using GPower.

For assessing construct validity, we employed Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA). Items were treated as ordinal variables; consequently, we utilized the weighted least squares with mean and variance adjusted (WLSMV) estimator. The adequacy of the CFA model was evaluated using several fit indices, including the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), χ2, the comparative fit index (CFI), and the Tucker–Lewis index (TLI). We considered the following cutoff scores: RMSEA scores below .05 indicate a good fit, while scores between .05 and .08 suggest an acceptable fit; a TLI score > .95 denotes a good fit; and a CFI score of > .95 indicates an excellent fit. Regarding χ2, a good fit is indicated when χ2 / df ≤ 2, while χ2 / df ≤ 3 suggests an acceptable fit. The CFA was performed using Mplus 8.6. The McDonald’s omega Ω was performed to assess internal consistency [

36,

37,

38,

39].

For the criterion-related validity analysis, we computed Pearson correlations and regression models among the CSI-8 total score, and ECR-8 items version and the following scales: Individual Sexual Satisfaction, Interpersonal Sexual Satisfaction, the nine subscales of the SCL-90 scale, and the total score of Sexual Addiction. Additionally, in our examination of sexual behavior, we considered the correlation with the following variables: age at first sexual intercourse, number of sexual partners, contraceptive use, alcohol use during sex, and drug use during sex.

To contrast hypersexuality and non-hypersexuality across various variables (psychological distress, sexual satisfaction, attachment, couple satisfaction, and sexual behavior), we established a categorical variable. This variable differentiated between scores equal to or lower than five and scores exceeding five on the SAT-R test, closely aligning with the Mexican version [

32]. The Mann–Whitney U test was performed to compare the differences between the hypersexuality and non-hypersexuality groups concerning the dependent variables.

We decided to explore differences between men and women in our variables of interest: psychological distress, sexual satisfaction, attachment, couple satisfaction, and sexual behavior. We used the Mann–Whitney U test again to compare the groups.

To assess the prediction of SAST-R test scores, we utilized the Classification and Regression Trees (CART) algorithm alongside logistic regression analysis. The algorithm underwent training on 80% of the dataset and testing on the remaining 20%. The decision tree was constructed with a maximum of three splits. Each node comprised decision rules, the Gini index, and the number of cases. Lower Gini indexes signify greater information gain or uncertainty reduction [for further details, refer to Mejía et al. [

40]]. The predicted group is found in the leaves of each terminal node. The statistical analyses were performed using Python 3.11, including sklearn libraries.

3. Results

3.1. Construct validity

According to the theoretical assumptions of the two dimensions in the ECR-R scale and the one factor of the CSI scale, we used confirmatory factor analysis to verify the hypothesis of a two-factor model and a one-factor model for the brief versions of these scales. The fit of the two-factor model for the brief version of the ECR-8 items scale and the one-factor model of the CSI-4 was better, considering the indices (see

Table 1).

3.2. Reliability of CSI-4 and ECR-8

The McDonald’s coefficient yielded Ω = .96 for the CSI-16 scale and Ω = .93 for the CSI-4 scale, indicating the reliability of both versions of the CSI. In consideration of the abbreviated version of the Experiences in Close Relationships (ECR) scale, the McDonald’s coefficient for the anxiety attachment scale was Ω = .99, while for the avoidance attachment scale, it was Ω = .99. These coefficients suggest that the abbreviated version of the ECR also demonstrates reliability (See

Table 1).

3.3. Sexual Behavior

In the current sample, we observed that the mean age of initiation of sexual behavior was 14.3 years (SD = 6.8), while the mean age of the partner at the onset of sexual behavior was 15.8 (SD = 9.7). Additionally, the mean number of sexual partners was found to be 4.55 (SD = 8.12). The 13.5% of the sample reported never having engaged in sexual relationships. 60.74% used protection during their sexual activity, while 20.56% reported using protection sometimes, and 5.14% reported not using protection at all. The 24.29% of the sample reported using drugs during sexual activity, and the 47.66% reported using alcohol during sexual encounters.

We decided to investigate whether these characteristics of sexual behavior were associated with five psychological measures. We found that the age of initiation of sexual behavior was correlated with ECR-avoidance attachment (r = -.153, p = .05); NSSS-S individual (r = .309, p < .001); NSSS-S interpersonal (r = .337, p < .001); Couple Satisfaction Index CSI-4 (r = .151, p = .028); SAST-R (r = .213, p = .002); number of sexual partners (r = .164, p = .018); use of drugs during sex (r = .60, p < .001); use of alcohol during sex (r = .626, p < .001); and lack of sexual protection (r = .519, p < .001) (see

Table 2).

In our analysis of the number of sexual partners, we observed correlations with specific factors, including SAST-R (r = .353, p < .001), alcohol consumption during sexual activity (r = .372, p < .001), drug use (r = .369, p < .001), and lack of sexual protection (r = .278, p < .001). The absence of sexual protection correlates with alcohol consumption during sexual experiences (r = .579, p < .001); drug use during sexual activity (r = .539, p < .001); and scores on the SAST-R scale (r = .300, p < .001). We identified a correlation between alcohol consumption and drug use during sexual activity (r = .709, p < .001); and scores on the SAST- R with alcohol (r = .390, p < .001), and drug use (r = .321, p < .001).

In the variable of individual sexual satisfaction of the NSSS-S, we observed a correlation between the use of alcohol (r = .221, p = .001) and drugs (r = .235, p < .001) during sexual activity. Conversely, in the variable of interpersonal sexual satisfaction, only the use of alcohol showed a correlation (r = .215, p = .002). Psychological distress is ultimately correlated with the SAST-R scale (r = .149, p = .029).

Table 2.

Correlations among the CSI, ECR, NSSS-S, SAST-R, SCL-90, and Sexual Behavior.

Table 2.

Correlations among the CSI, ECR, NSSS-S, SAST-R, SCL-90, and Sexual Behavior.

| Variable |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

| 1. CSI-4 |

— |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2. ECR-8 Anxious |

-.038 |

— |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 3. ECR-8 Avoidant |

-.384*** |

.145* |

— |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 4. Individual NSSS-S |

.296*** |

-.048 |

-.296*** |

— |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 5. Interpersonal NSSS-S |

.254*** |

-.062 |

-.247*** |

.806*** |

— |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 6. SAST-TR |

.071 |

.061 |

.05 |

.037 |

.037 |

— |

|

|

|

|

|

| 7. SCL90 |

-.104 |

.103 |

.071 |

-.167* |

-.131 |

.149* |

— |

|

|

|

|

| 8. Age of initiation of sexual activity |

.151* |

.043 |

-.153* |

.309*** |

.337*** |

.213** |

.055 |

— |

|

|

|

| 9. Number sexual partners |

.125 |

-.079 |

.088 |

.113 |

.088 |

.353*** |

-.104 |

.164* |

— |

|

|

| 10. Contraceptive use |

.056 |

-.002 |

-.048 |

.053 |

.016 |

.3*** |

.012 |

.519*** |

.278*** |

— |

|

| 11. Alcohol use during sex |

.105 |

.075 |

.01 |

.221** |

.215** |

.39*** |

.025 |

.626*** |

.372*** |

.579*** |

— |

| 12. Drug use during sex |

.112 |

-.014 |

.026 |

.235*** |

.129 |

.321*** |

.064 |

.6*** |

.369*** |

.539*** |

.709*** |

3.4. Sexual and Couple Satisfaction

Considering partner satisfaction and attachment variables, we noted a significant negative correlation between ECR-avoidant attachment and CSI-4 (r = -.384, p < .001). Additionally, we identified a positive correlation between individual sexual satisfaction and CSI-4 (r = .296, p < .001), as well as between interpersonal sexual satisfaction and CSI-4 (r = .254, p < .001). We found no correlation between couple satisfaction, psychological distress, and hypersexuality (see

Table 2).

In terms of sexual satisfaction, we observed a negative correlation between ECR-avoidant attachment and both individual sexual satisfaction (r = -.296, p < .001) and interpersonal sexual satisfaction (r = -.247, p < .001). Additionally, we identified a negative correlation between psychological distress and individual sexual satisfaction (r = -.167, p = .015), with a marginally significant association observed with interpersonal sexual satisfaction (r = -.131, p = .055). We found no correlation between sexual satisfaction and hypersexuality.

3.5. Gender Differences

Considering gender, we decided to contrast males and females, given that we had too few non-binary participants to include them in the analysis (see

Table 3). We found significant differences in attachment and anxiety scales: women tended to have higher levels of anxious attachment, while men exhibited higher levels of avoidant attachment. In terms of individual sexual satisfaction, men reported higher levels than women. Regarding couple satisfaction, no differences were found between the groups. Similarly, no differences were found on the sexual addiction scale. Finally, in the psychological distress scales, women tended to report higher levels of somatization, obsession, and depressive symptoms compared to men.

3.6. Hypersexual Behavior

In examining the correlation between hypersexuality and attachment style, we observed no significant correlation between the SAST-R and ECR scales (all p-values > 0.05). However, we found a significant positive correlation between psychological distress and hypersexuality (r = −.149, p = .029) (see

Table 4).

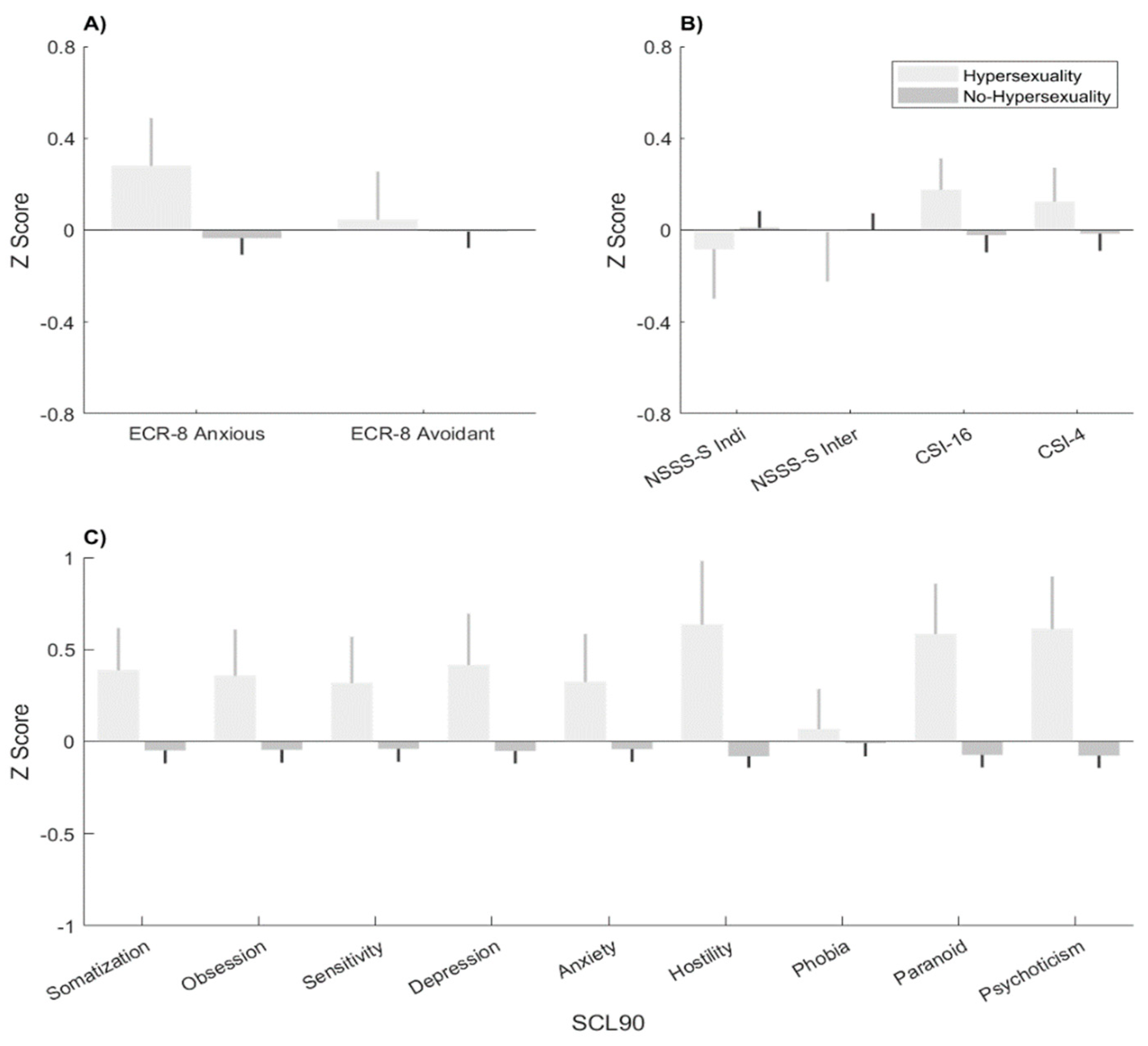

Figure 1A shows that the z-scores for ECR Anxious and Avoidant were higher for the hypersexual group. However, a Mann-Whitney U test revealed statistically significant differences only in the anxiety subscale (

Table 4).

Figure 1B indicates that individual and interpersonal sexual satisfaction in the hypersexual group was lower compared to the non-hypersexual group. Nonetheless, participants in the hypersexual group reported greater couple satisfaction on both the 16-item and 4-item scales. However, no statistically significant differences were observed (

Table 4). Finally,

Figure 1C presents the results of the SCL-90 subscales for both groups. The hypersexual group exhibited higher scores on all SCL-90 subscales compared to the non-hypersexual group, with statistically significant differences observed solely in the Paranoid and Psychoticism subscales (

Table 4).

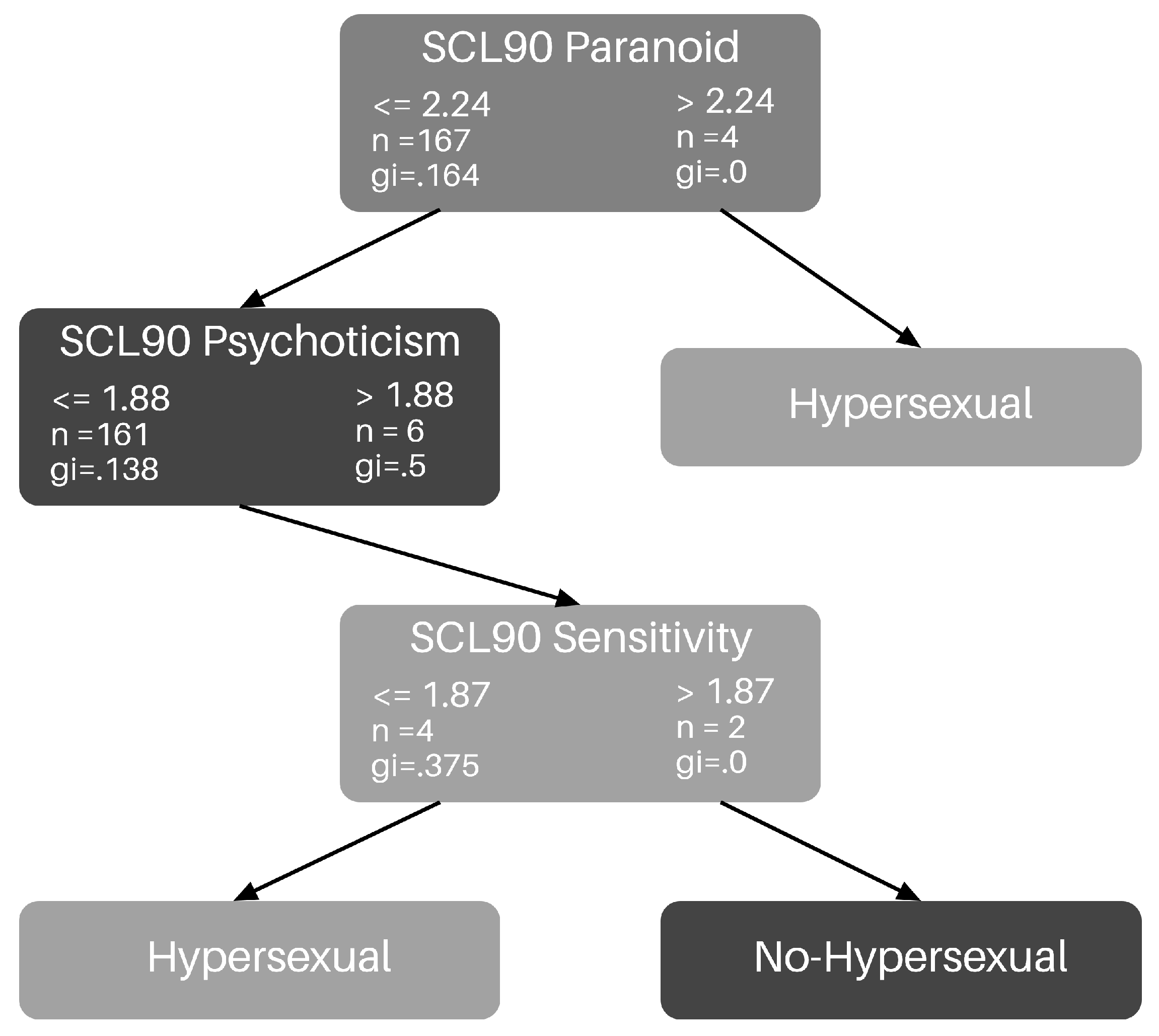

Figure 2 presents the results of the CART algorithm for the z-scores of the subscales, identifying predictors for both the non-hypersexual and hypersexual groups. The model’s accuracy, derived from comparing the training set (80% of the data) and testing set (20% of the data), was 0.83. Additionally, the relative importance of factors that best classified the sample was as follows: SCL-90 Paranoid (0.64), SCL-90 Psychoticism (0.21), and ECR Avoidant (0.15). High scores on SCL-90 Paranoid, combined with high scores on SCL-90 Psychoticism and ECR Avoidant, unequivocally classified 31% of hypersexual participants (Gini = 0).

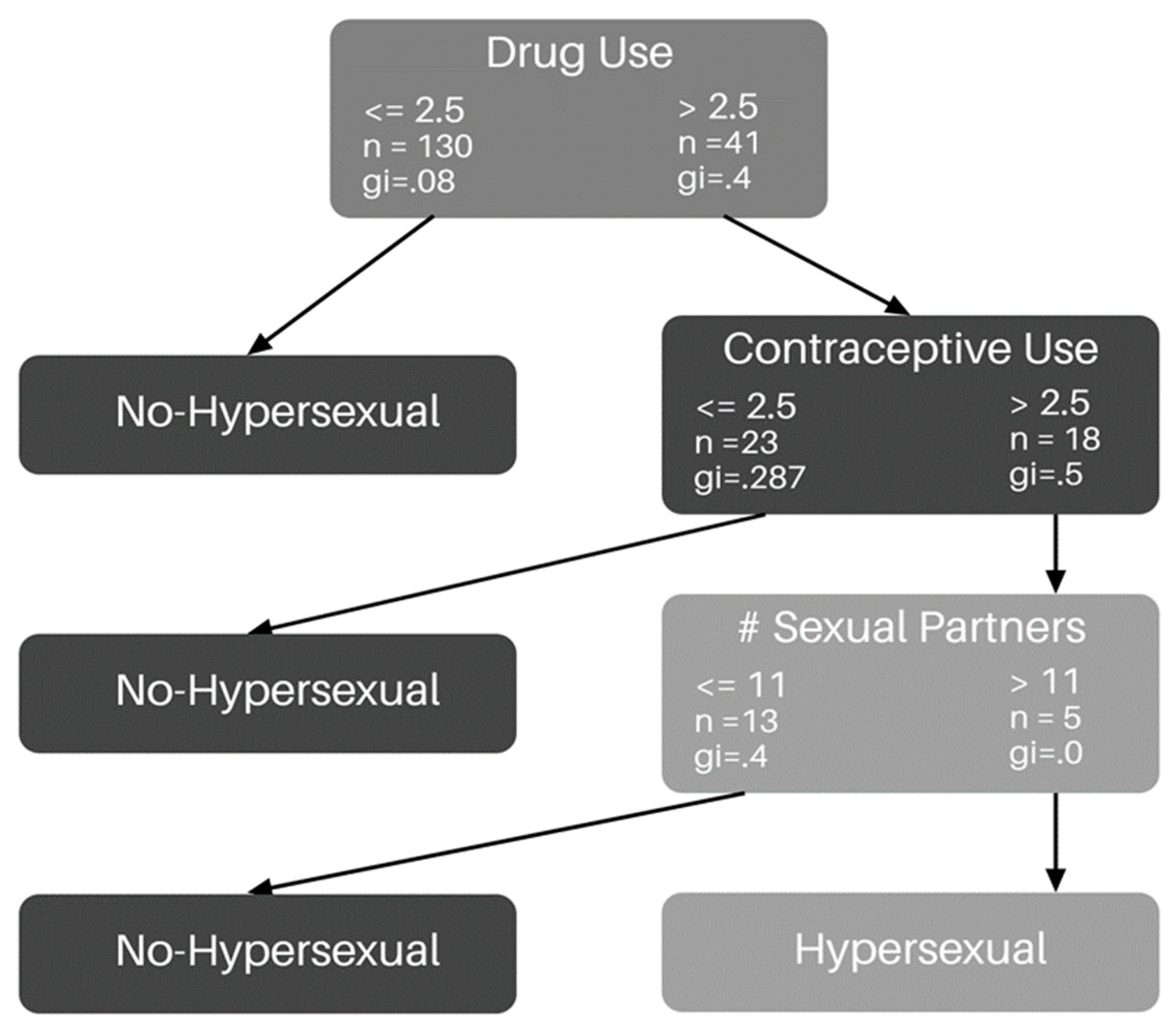

Figure 3 presents the results of the CART algorithm for the frequency of sexual behaviors in both non-hypersexual and hypersexual groups. The model’s accuracy was 0.83, based on 80% training and 20% testing data. The relative importance of factors that best classified the sample was as follows: drug use (.44), number of sexual partners (.33), and contraceptive use (.21). The combination of higher drug use, greater contraceptive use, and a higher number of sexual partners unequivocally classified 26% of the hypersexual participants (Gini = 0).

Considering sexual behavior,

Table 5 presents the socio-demographic data organized into hypersexual and non-hypersexual groups. No statistically significant differences were observed in age, income, years of education, or age at first sexual intercourse. However, differences were observed in the number of sexual partners, contraceptive use, alcohol use during sex, and drug use during sex. The hypersexual group tended to exhibit more risky sexual behaviors.

4. Discussion

In the present study, we observed a significant association between riskier sexual behaviors—such as a higher number of sexual partners, drug and alcohol use during sexual activity, and lack of sexual protection—and elevated scores of hypersexuality, which aligns with findings from previous research [

3,

4]. Moreover, participants with higher scores of hypersexuality demonstrated increased levels of psychological distress. Specifically, the hypersexual group exhibited elevated scores across all SCL-90 subscales compared to the non-hypersexual group, consistent with prior investigations [

41].

However, our aim was to further investigate whether sexual behavior problems, including sex addiction, are underpinned by attachment issues, as suggested by previous studies. Contrary to expectations, in our sample, anxiety and avoidance attachment styles showed limited associations with sexual behavior, while attachment variables were more strongly correlated with perceptions of couple dynamics and sexual satisfaction. This suggests that the underlying mechanisms contributing to sexual problems may be more closely linked to cognitive impairments, such as impulsivity (including urgency, lack of control, lack of perseverance, lack of premeditation, and sensation-seeking) [

42,

43]. Nonetheless, avoidant attachment emerged as the attachment style most strongly associated with early sexual experiences, which may hypothetically impact secure attachment formation.

In this context, our aim was to explore predictive models for identifying hypersexual behavior. The results obtained from the CART algorithm revealed that the subscales of psychological distress were the most effective in identifying hypersexuality. Specifically, elevated symptoms of paranoia, psychoticism, and interpersonal sensitivity were found to significantly reduce entropy, thus aiding in the identification of hypersexual participants.

Subsequently, in a second iteration of the CART algorithm, we identified variables such as drug use, lack of sexual protection, and a high number of sexual partners as key factors for identifying hypersexual individuals. This collective evidence suggests that cognitive impairment resulting from drug use and impulsive disorders contributes to both elevated psychological distress and risky sexual behaviors observed in hypersexuality [

6,

41,

44]. Furthermore, these risky behaviors heighten the probability of developing physical disabilities, such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and other sexually transmitted infections. Subsequently, these conditions exacerbate cognitive impairment, as highlighted in prior studies [

45].

Although lacking statistical significance, we observed a greater prevalence of anxiety and avoidant attachment styles among hypersexual participants compared to non-hypersexual individuals. Additionally, hypersexual participants reported lower levels of sexual satisfaction, aligning with previous research findings [

10]. Surprisingly, hypersexual participants reported higher levels of couple satisfaction compared to their non-hypersexual counterparts, as indicated by both the brief CSI-4 and the longer CSI-16 scales. This finding contrasts with some prior studies that have highlighted the negative impact of hypersexuality on interpersonal relationships [

3]. It’s possible that such effects may be more pronounced in adulthood; however, our sample primarily consisted of emerging adults.

We found that the brief versions of the couple satisfaction scale (CSI-4) and the attachment scale (ECR-8) demonstrated good psychometric properties, enhancing their practicality for research purposes, as observed in prior studies. Criterion validation revealed that the CSI-4 scale exhibited convergent validity with measures of sexual satisfaction, as anticipated, while demonstrating divergent validity with variables such as psychological distress [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31]. Similarly, the ECR-8 attachment scale diverged from constructs such as sexual and couple satisfaction, as expected [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26]. Based on these findings, we advocate for the continued utilization of these brief scales in research settings. Furthermore, our study provides evidence supporting their applicability within the Latino population, consistent with prior research [

7,

11,

20,

21].

Regarding gender differences, our findings were consistent with previous research, indicating that women exhibited higher levels of psychological distress compared to men [

46,

47]. Specifically, women displayed elevated scores on subscales measuring somatization, obsessive symptoms, and depression. In terms of sexual satisfaction, men tended to report higher levels than women, whereas women reported higher levels of couple satisfaction compared to men. These results align with previous studies in the field [

48].

A noteworthy finding in our sample was that men demonstrated a higher prevalence of attachment problems compared to women. At this juncture, we recommend that future studies take into account potential cultural differences that may contribute to understanding gender disparities.

In future studies, we recommend integrating cognitive measures to further clarify the heightened risk of developing hypersexuality, such as the Iowa Gambling Task, delay discounting task, and working memory, as observed in prior research [

43,

49]. We posit that adult attachment serves as a significant variable contributing to vulnerabilities in sexual risk behavior. Therefore, it is imperative to implement skills training aimed at fostering secure attachment among adolescents. Such interventions could empower individuals to explore and express their sexuality in a secure manner, without resorting to alcohol or drugs. Moreover, emphasizing the importance of using protection during sexual encounters and fostering romantic relationships based on respect, admiration, and reciprocity are crucial aspects. Previous research has demonstrated the efficacy of romantic competence training in this regard [

50,

51]. Consequently, we advocate for the evaluation of romantic competence within the Latino population.

In conclusion, we believe that the present study offers valuable insights into sexual behavior and romantic interactions within the Mexican population. Our research contributes by introducing new brief scales for assessing couple satisfaction and adult attachment. Additionally, we provide evidence regarding sexual behavior among Latin emerging adults, highlighting the heightened risk of developing sexual addiction associated with alcohol and drug use, as well as its impact on psychological distress. Notably, our study stands out as one of the few to simultaneously explore sexual satisfaction, couple satisfaction, attachment, and sexual behavior. The integration of these variables facilitates the development of novel prevention strategies aimed at promoting secure sexual interactions and fostering healthy romantic relationships.

Author Contributions

DMC: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project Administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. LAC: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Software, Writing—review & editing. LVG: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing—review & editing.

Funding

This study received financial support from the Sonora Institute of Technology PROFAPI_2024_018, and National Council of Humanities, Science and Technology CONAHCYT project CF-2023-I-2522

Institutional Review Board Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Sonora Institute of Technology Review Board (ID 178).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bowlby, J. Attachment and loss: Retrospect and prospect. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 1982, 52, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corcoran, M.; McNulty, M. Examining the role of attachment in the relationship between childhood adversity, psychological distress and subjective well-being. Child Abuse & Neglect 2018, 76, 297–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilliland, R.; Blue Star, J.; Hansen, B.; Carpenter, B. Relationship attachment styles in a sample of hypersexual patients. J. Sex Marital Ther. 2015, 41, 581–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElwain, A.D.; Kerpelman, J.L.; Pittman, J.F. The role of romantic attachment security and dating identity exploration in understanding adolescents’ sexual attitudes and cumulative sexual risk-taking. J. Adolesc. 2015, 39, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busby, D.M.; Hanna-Walker, V.; Yorgason, J.B. A closer look at attachment, sexuality, and couple relationships. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2020, 37, 1362–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciocca, G.; Pelligrini, F.; Mollaioli, D.; Limoncin, E.; Sansone, A.; Colonnello, E.; Fontanesi, L. Hypersexual behavior and attachment styles in a non-clinical sample: The mediation role of depression and post-traumatic stress symptoms. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 293, 399–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shelton, A.J.; Wang, C.D. Adult attachment among US Latinos: Validation of the Spanish Experiences in Close Relationships Scale. J. Lat. /O Psychol. 2018, 6, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altan-Atalay, A.; Sohtorik İlkmen, Y. Attachment and psychological distress: The mediator role of negative mood regulation expectancies. J. Clin. Psychol. 2020, 76, 778–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butzer, B.; Campbell, L. Adult attachment, sexual satisfaction, and relationship satisfaction: A study of married couples. Pers. Relatsh. 2008, 15, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafortune, D.; Girard, M.; Bolduc, R.; Boislard, M.A.; Godbout, N. Insecure attachment and sexual satisfaction: A path analysis model integrating sexual mindfulness, sexual anxiety, and sexual self-esteem. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy 2022, 48, 535–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Pichardo, A.Y.; Garrido, L.E.; Aranda Torres, C.; Parrón-Carreño, T. Del apego adulto a la infidelidad sexual: Un análisis de mediación múltiple. Psykhe (Santiago) 2020, 29, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candel, O.S.; Turliuc, M.N. Insecure attachment and relationship satisfaction: A meta-analysis of actor and partner associations. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2019, 147, 190–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feeney, J.A.; Karantzas, G.C. Couple conflict: Insights from an attachment perspective. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2017, 13, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgis, B.L.; Ewing, E.S.K.; Liu, T. A Hold Me Tight Workshop for Couple Attachment and Sexual Intimacy. Contemp Fam Ther 2019, 41, 368–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiebe, S.A.; Elliott, C.; Johnson, S.M.; Burgess Moser, M.; Dalgleish, T.L.; Lafontaine, M.F.; Tasca, G.A. Attachment change in emotionally focused couple therapy and sexual satisfaction outcomes in a two-year follow-up study. J. Couple Relatsh. Ther. 2019, 18, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, F.; Liu, Y.; Brat, M. Attachment, Self-Esteem, and Psychological Distress: A Multiple-Mediator Model. Prof. Couns. 2021, 11, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, R.D.; Houser, M.E. Extending the four-category model of adult attachment: An interpersonal model of friendship attachment. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2010, 27, 351–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafontaine, M.F.; Brassard, A.; Lussier, Y.; Valois, P.; Shaver, P.R.; Johnson, S.M. Selecting the best items for a short-form of the Experiences in Close Relationships questionnaire. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2015, 32, a000243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, M.; Russell, D.W.; Mallinckrodt, B.; Vogel, D.L. The Experiences in Close Relationship Scale (ECR)-short form: Reliability, validity, and factor structure. J. Personal. Assess. 2007, 88, 187–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-arbiol, I.; Balluerka, N.; Shaver, P.R. A Spanish version of the Experiences in Close Relationships (ECR) adult attachment questionnaire. Pers. Relatsh. 2007, 14, 45–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Mosquera, E.; Latorre Vaca, G.; Merlyn Sacoto, M.F.; Moreta-Herrer, R.; Nóblega, M. Características psicométricas del ECR-R (Experiences in Close Relationships-Revised) en población ecuatoriana. Rev. Argent. De Cienc. Del Comport. 2022, 14, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brugnera, A.; Zarbo, C.; Farina, B.; Picardi, A.; Greco, A.; Coco, G.L.; Compare, A. Psychometric properties of the Italian version of the Experience in Close Relationship Scale 12 (ECR-12): An exploratory structural equation modeling study. Research in Psychotherapy: Psychopathology, Process, and Outcome 2019, 22. [CrossRef]

- Constantinescu, N.; Bacro, F.; Dincă, M. A Romanian version of the experiences in close relationship scale-short form (ECR-S) measure of adult attachment. Journal of Evidence-Based Psychotherapies, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Shin, Y.J. Experience in close relationships scale–short version (ECR–S) validation with Korean college students. Meas. Eval. Couns. Dev. 2019, 52, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, S.; Spitzer, C.; Flemming, E.; Ehrenthal, J.C.; Mestel, R.; Strauß, B.; Lübke, L. Measuring change in attachment insecurity using short forms of the ECR-R: Longitudinal measurement invariance and sensitivity to treatment. J. Personal. Assess. 2024, 106, 218–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philipp, R.; Vehling, S.; Scheffold, K.; Grünke, B.; Härter, M.; Mehnert, A.; Lo, C. Attachment insecurity in advanced cancer patients: Psychometric properties of the German version of the Brief Experiences in Close Relationships Scale (ECR-M16-G). Journal of pain and symptom management 2017, 54, 555–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Frenn, Y.; Akel, M.; Hallit, S.; Obeid, S. Couple’s Satisfaction among Lebanese adults: Validation of the Toronto Alexithymia Scale and Couple Satisfaction Index-4 scales, association with attachment styles and mediating role of alexithymia. BMC Psychol. 2022, 10, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forouzesh Yekta, F.; Yaghubi, H.; Mootabi, F.; Roshan, R.; Gholami Fesharaki, M.; Omidi, A. Psychometric characteristics and factor analysis of the Persian version of Couples Satisfaction Index. Avicenna J. Neuro Psycho Physiol. 2017, 4, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn-Nilas, C. Time for a measurement check-up: Testing the Couple’s Satisfaction Index and the Global Measure of Sexual Satisfaction using structural equation modeling and item response theory. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2023, 40, 2252–2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayee, A.A.; Kamal, A. Couple’s Satisfaction of Married Adults from Pakistan: A Cross-Cultural Validation of Couple Satisfaction Index-4. Pakistan Social Sciences Review 2024, 8, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.S.; Gil, M.; Kim, D.; Kim, S.; Heo, D.; Moon, N.Y. Validity and reliability of the Korean version of the couple satisfaction index. J. Korean Acad. Nurs. 2022, 52, 228–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejía Cruz, D.; Avila Chauvet, L.; Villalobos-Gallegos, L.; Toledo-Lozano, C.G. Impulsivity and sexual addiction: Factor structure and criterion-related validity of the sexual addiction screening test in Mexican adults. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1265822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funk, J.L.; Rogge, R.D. Testing the ruler with item response theory: Increasing precision of measurement for relationship satisfaction with the Couples Satisfaction Index. J. Fam. Psychol. 2007, 21, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strizzi, J.; Fernández-Agis, I.; Alarcón-Rodríguez, R.; Parrón-Carreño, T. Adaptation of the new sexual satisfaction scale-short form into Spanish. J. Sex Marital Ther. 2016, 42, 579–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz Fuentes, C.S.; López Bello, L.; Blas García, C.; González Macías, L.; Chávez Balderas, R.A. Datos sobre la validez y confiabilidad de la Symptom Check List 90 (SCL 90) en una muestra de sujetos mexicanos. Salud Ment. 2005, 28, 72–81. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, D.L.; Gillaspy, J.A., Jr.; Purc-Stephenson, R. Reporting practices in confirmatory factor analysis: An overview and some recommendations. Psychol. Methods 2009, 14, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming (multivariate applications series). New York: Taylor Fr. Group 2010, 396, 7384. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schermelleh-Engel, K.; Moosbrugger, H.; Müller, H. Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: Tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. Methods Psychol. Res. Online 2003, 8, 23–74. [Google Scholar]

- Mejía, D.; Avila-Chauvet, L.; Toledo-Fernández, A. Decision-making under risk and uncertainty by substance abusers and healthy controls. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 12, 788280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafka, M.P. Hypersexual disorder: A proposed diagnosis for DSM-V. Arch Sex Behav 2010, 39, 377–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cyders, M.A.; Smith, G.T.; Spillane, N.S.; Fischer, S.; Annus, A.M.; Peterson, C. Integration of impulsivity and positive mood to predict risky behavior: Development and validation of a measure of positive urgency. Psychol Assess 2007, 19, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, R.C.; Berlin, H.A.; Kingston, D.A. Sexual impulsivity in hypersexual men. Curr Behav Neurosci Rep 2015, 2, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, R.C.; Meyer, M.D. Substance use disorders in hypersexual adults. Curr Addict Rep 2016, 3, 400–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, R.M.; Gonzalez, R. Substance abuse, hepatitis C, and aging in HIV: Common cofactors that contribute to neurobehavioral disturbances. Neurobehav HIV Med 2012, 15–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matud, M.P.; Díaz, A.; Bethencourt, J.M.; Ibáñez, I. Stress and psychological distress in emerging adulthood: A gender analysis. J Clin Med 2020, 9, 2859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viertiö, S.; Kiviruusu, O.; Piirtola, M.; Kaprio, J.; Korhonen, T.; Marttunen, M.; Suvisaari, J. Factors contributing to psychological distress in the working population, with a special reference to gender difference. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, J.B.; Miller, R.B.; Oka, M.; Henry, R.G. Gender differences in marital satisfaction: A meta-analysis. J Marriage Fam 2014, 76, 105–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miner, M.H.; Romine, R.S.; Raymond, N.; Janssen, E.; MacDonald, A., III; Coleman, E. Understanding the personality and behavioral mechanisms defining hypersexuality in men who have sex with men. J Sex Med 2016, 13, 1323–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davila, J.; Zhou, J.; Norona, J.; Bhatia, V.; Mize, L.; Lashman, K. Teaching romantic competence skills to emerging adults: A relationship education workshop. Pers. Relatsh. 2021, 28, 251–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davila, J.; Mattanah, J.; Bhatia, V.; Latack, J.A.; Feinstein, B.A.; Eaton, N.R.; Zhou, J. Romantic competence, healthy relationship functioning, and well-being in emerging adults. Pers. Relatsh. 2017, 24, 162–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).