Submitted:

07 June 2024

Posted:

11 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. HCV-Screening Campaign and LTC

2.2. Recall Programme

2.3. Description of the HCV Treatment in Taiwan

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Self-Awareness of HCV Infection and LTC

3.2. Effectiveness of the Recall Programme

3.3. Clinical Features and Outcomes of the LTC Participants

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- WHO, Global hepatitis report, 2017.Geneva:World Health Organization. 2017.

- Stoove, M.; Wallace, J.; Higgs, P.; Pedrana, A.; Goutzamanis, S.; Latham, N.; Scott, N.; Treloar, C.; Crawford, S.; Doyle, J.; Hellard, M. , Treading lightly: Finding the best way to use public health surveillance of hepatitis C diagnoses to increase access to cure. Int J Drug Policy 2020, 75, 102596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chien, R. N.; Lu, S. N.; Pwu, R. F.; Wu, G. H.; Yang, W. W.; Liu, C. L. , Taiwan accelerates its efforts to eliminate hepatitis C. Glob Health Med 2021, 3, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chien, R. N.; Lu, S. N.; Hui-Min Wu, G.; Yang, W. W.; Pwu, R. F.; Liu, C. L.; Cheng, K. P.; Chen, S. C.; Chen, C. J. , Policy and Strategy for Hepatitis C Virus Elimination at the National Level: Experience in Taiwan. J Infect Dis 2023, (Suppl 3) (Suppl 3), S180–S188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M. L.; Yeh, M. L.; Tsai, P. C.; Huang, C. I.; Huang, J. F.; Huang, C. F.; Hsieh, M. H.; Liang, P. C.; Lin, Y. H.; Hsieh, M. Y.; Lin, W. Y.; Hou, N. J.; Lin, Z. Y.; Chen, S. C.; Dai, C. Y.; Chuang, W. L.; Chang, W. Y. , Huge gap between clinical efficacy and community effectiveness in the treatment of chronic hepatitis C: a nationwide survey in Taiwan. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015, 94, e690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, K.; Terrault, N. A. , Gaps in Viral Hepatitis Awareness in the United States in a Population-based Study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020, 18, 188–195 e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.; Clark, R.; Tu, P.; Tu, R.; Hsu, Y. J.; Nien, H. C. , The disconnect in hepatitis screening: participation rates, awareness of infection status, and treatment-seeking behavior. J Glob Health 2019, 9, 010426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denniston, M. M.; Klevens, R. M.; McQuillan, G. M.; Jiles, R. B. , Awareness of infection, knowledge of hepatitis C, and medical follow-up among individuals testing positive for hepatitis C: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2001-2008. Hepatology 2012, 55, 1652–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, C. A.; Chen, H. C.; Lu, S. N.; Chen, C. J.; Lu, C. F.; You, S. L.; Lin, S. H. , Persistent hyperendemicity of hepatitis C virus infection in Taiwan: the important role of iatrogenic risk factors. J Med Virol 2001, 65, 30–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kondili, L. A.; Robbins, S.; Blach, S.; Gamkrelidze, I.; Zignego, A. L.; Brunetto, M. R.; Raimondo, G.; Taliani, G.; Iannone, A.; Russo, F. P.; Santantonio, T. A.; Zuin, M.; Chessa, L.; Blanc, P.; Puoti, M.; Vinci, M.; Erne, E. M.; Strazzabosco, M.; Massari, M.; Lampertico, P.; Rumi, M. G.; Federico, A.; Orlandini, A.; Ciancio, A.; Borgia, G.; Andreone, P.; Caporaso, N.; Persico, M.; Ieluzzi, D.; Madonia, S.; Gori, A.; Gasbarrini, A.; Coppola, C.; Brancaccio, G.; Andriulli, A.; Quaranta, M. G.; Montilla, S.; Razavi, H.; Melazzini, M.; Vella, S.; Craxi, A.; Group, P. C. , Forecasting Hepatitis C liver disease burden on real-life data. Does the hidden iceberg matter to reach the elimination goals? Liver Int 2018, 38, 2190–2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Treloar, C.; Rance, J.; Backmund, M. , Understanding barriers to hepatitis C virus care and stigmatization from a social perspective. Clin Infect Dis 2013, 57 Suppl 2, S51–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspinall, E. J.; Corson, S.; Doyle, J. S.; Grebely, J.; Hutchinson, S. J.; Dore, G. J.; Goldberg, D. J.; Hellard, M. E. , Treatment of hepatitis C virus infection among people who are actively injecting drugs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis 2013, 57 Suppl 2, S80–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, M.; Sarkar, R.; Diez-Quevedo, C. , Management of mental health problems prior to and during treatment of hepatitis C virus infection in patients with drug addiction. Clin Infect Dis 2013, 57 Suppl 2, S111–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yehia, B. R.; Schranz, A. J.; Umscheid, C. A.; Lo Re, V. , 3rd, The treatment cascade for chronic hepatitis C virus infection in the United States: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2014, 9, e101554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Younossi, Z. M.; Stepanova, M.; Afendy, M.; Lam, B. P.; Mishra, A. , Knowledge about infection is the only predictor of treatment in patients with chronic hepatitis C. J Viral Hepat 2013, 20, 550–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viner, K.; Kuncio, D.; Newbern, E. C.; Johnson, C. C. , The continuum of hepatitis C testing and care. Hepatology 2015, 61, 783–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bajis, S.; Dore, G. J.; Hajarizadeh, B.; Cunningham, E. B.; Maher, L.; Grebely, J. , Interventions to enhance testing, linkage to care and treatment uptake for hepatitis C virus infection among people who inject drugs: A systematic review. Int J Drug Policy 2017, 47, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuure, F. R.; Heijman, T.; Urbanus, A. T.; Prins, M.; Kok, G.; Davidovich, U. , Reasons for compliance or noncompliance with advice to test for hepatitis C via an internet-mediated blood screening service: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seedat, F.; Hargreaves, S.; Friedland, J. S. , Engaging new migrants in infectious disease screening: a qualitative semi-structured interview study of UK migrant community health-care leads. PLoS One 2014, 9, e108261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Aware of HCV infection | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | P value | |

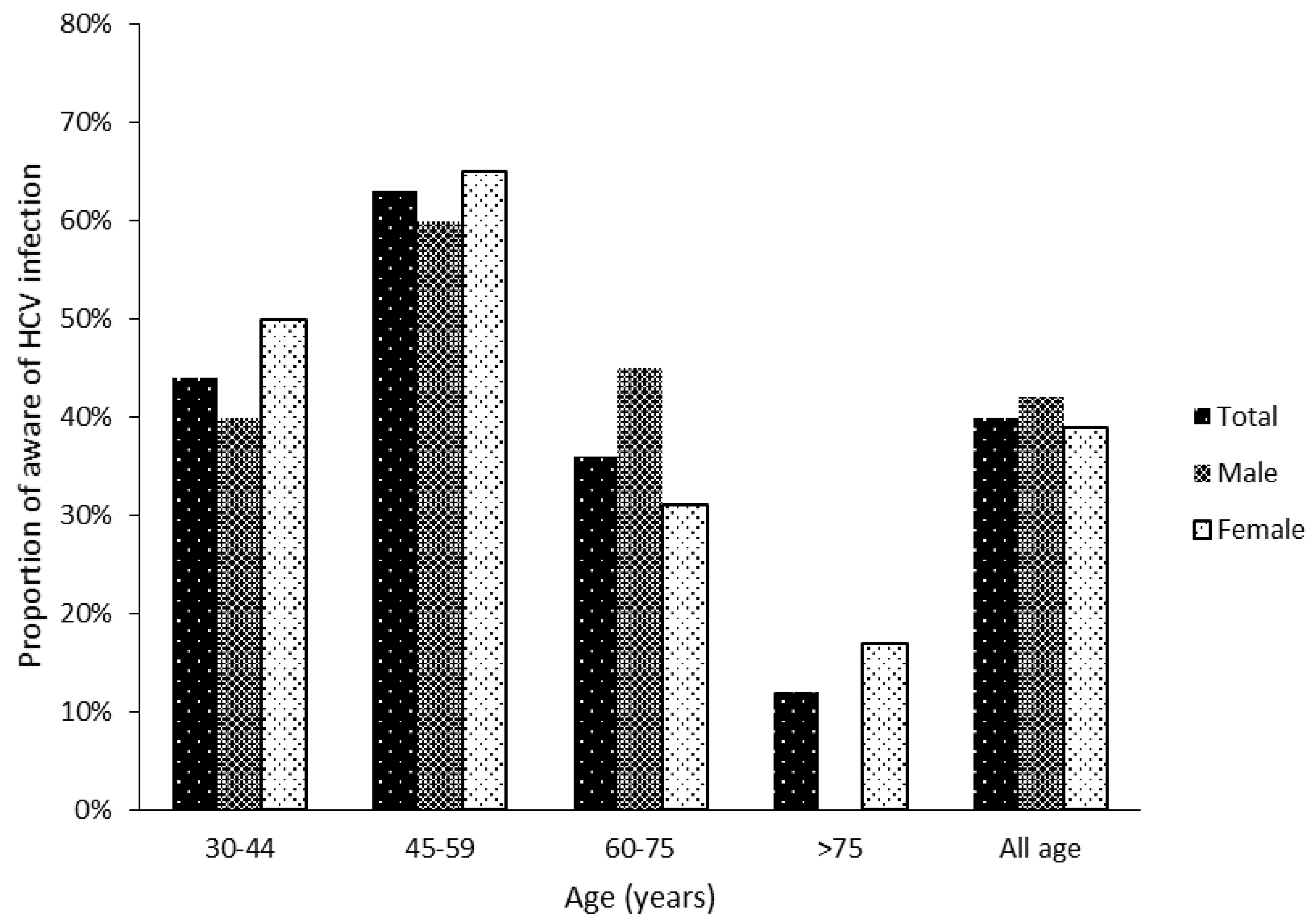

| Number | 111 | 74 | |

| Male (%) | 34(30.6) | 25(33.8) | 0.625 |

| Age, years | 67.7 ± 10.1 | 61.0 ± 8.5 | <0.001 |

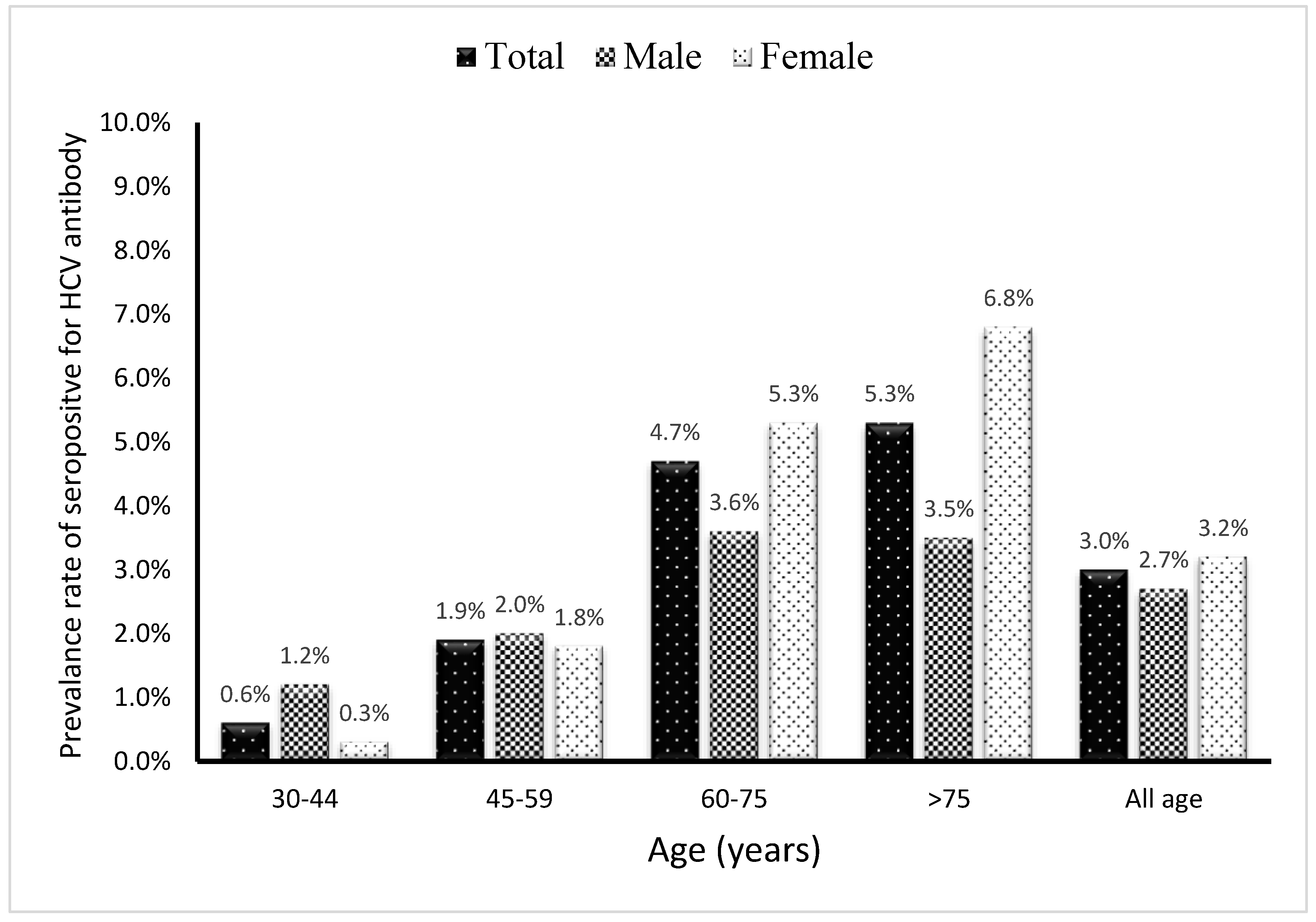

| 30-44 | 5(4.5) | 4(5.4) | <0.001 |

| 45-59 | 18(16.2) | 31(41.9) | |

| 60-75 | 65(58.6) | 36(48.6) | |

| >75 | 23(20.7) | 3(4.1) | |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 25.3 ± 3.6 | 24.3 ± 3.9 | 0.075 |

| Private health Insurance, Yes (%) | 56(52.8) | 56(78.9) | <0.001 |

| Education level (%) | |||

| No education completed | 29(26.9) | 3(4.2) | <0.001 |

| Elementary school | 39(36.1) | 21(29.2) | |

| Middle school | 18(16.7) | 21(29.2) | |

| High school | 12(11.1) | 15(20.8) | |

| College and higher | 10(9.3) | 12(16.7) | |

| Live in urban area (%) | 45(40.5) | 40(54.1) | 0.071 |

| Alcohol consumption, Yes (%) | 16(14.7) | 23(32.9) | 0.04 |

| Smoking, Yes (%) | 22(19.8) | 19(26.0) | 0.322 |

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 19(17.1) | 14(18.9) | 0.754 |

| Hypertension (%) | 44(39.6) | 25(33.8) | 0.42 |

| Hepatitis B carrier (%) | 11(10.0) | 10(13.7) | 0.442 |

| Family history of liver disease (%) | 12(10.9) | 13(17.8) | 0.183 |

| AST > 34 U/L (%) | 25(22.5) | 25(33.8) | 0.091 |

| ALT > 36 U/L (%) | 25(22.5) | 27(36.5) | 0.038 |

| Linkage to care | |||

| No | Yes | P value | |

| Number | 76 | 109 | |

| Male (%) | 26(34.2) | 33(30.3) | 0.572 |

| Age, years | 67.0±11.6 | 63.7±8.6 | 0.035 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 24.9 ± 3.3 | 24.9 ± 4.0 | 0.982 |

| Live in urban area (%) | 28(36.8) | 57(52.3) | 0.038 |

| Education level (%) | |||

| No education completed | 21(28.8) | 11(10.5) | 0.032 |

| Elementary school | 20(26.7) | 40(38.1) | |

| Middle school | 13(17.3) | 26(24.8) | |

| High school | 11(14.7) | 16(15.2) | |

| College and higher | 10(13.3) | 12(11.4) | |

| Insurance, Yes (%) | 39(53.4) | 73(70.2) | 0.023 |

| Alcohol consumption, Yes (%) | 15(19.7) | 24(23.3) | 0.568 |

| Smoking, Yes (%) | 19(25.0) | 22(20.4) | 0.457 |

| Aware of HCV infection | 18(23.7) | 55(51.4) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 12(15.8) | 20(18.7) | 0.611 |

| Hypertension | 27(35.5) | 40(37.4) | 0.797 |

| Stroke | 1(1.3) | 4(3.7) | 0.322 |

| HBsAg(+) | 11(14.5) | 12(11.0) | 0.482 |

| Family history of liver disease | 13(17.1) | 12(11.2) | 0.253 |

| AST > 34 U/L | 16(21.1) | 34(31.2) | 0.127 |

| ALT > 36 U/L | 17(22.4) | 35(34.4) | 0.147 |

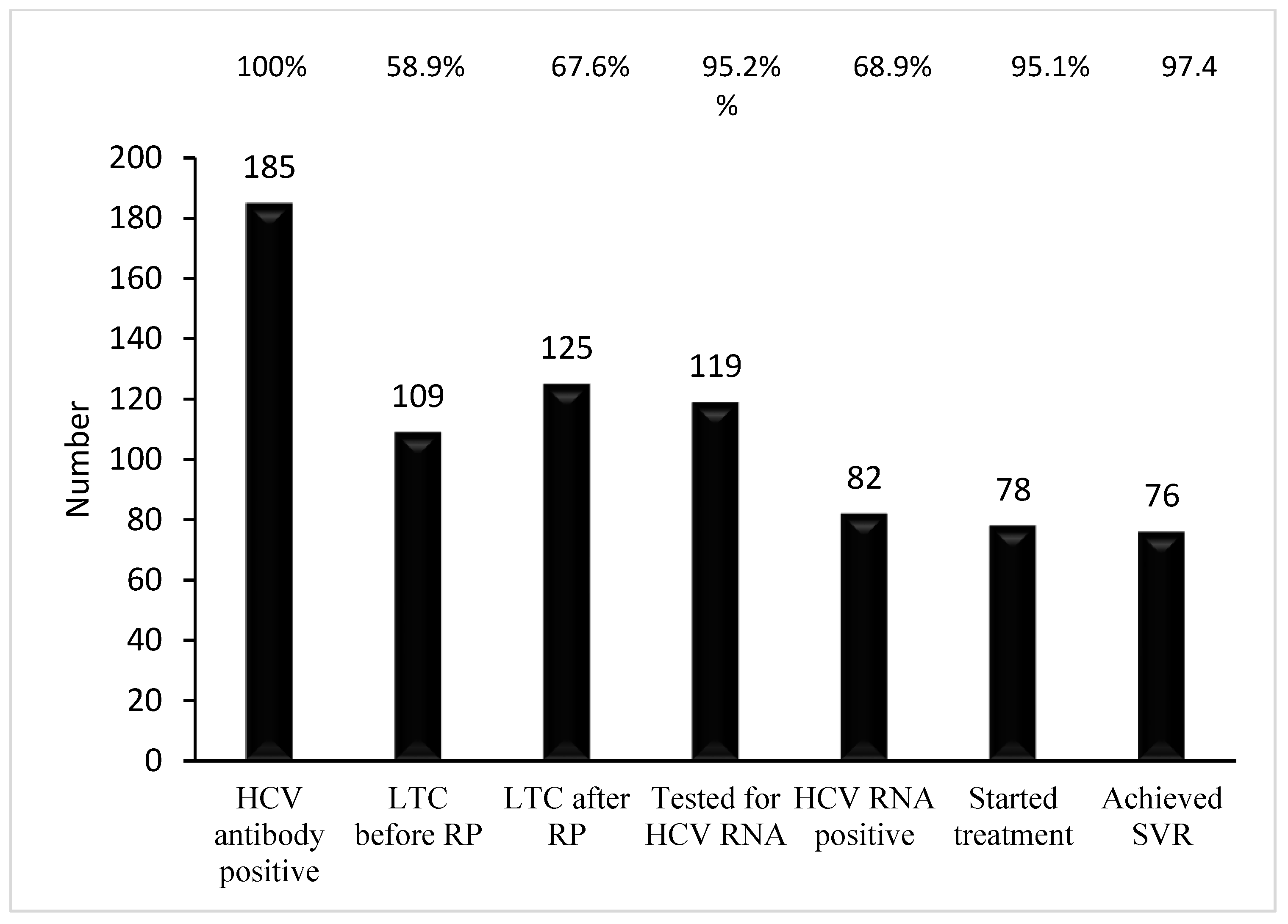

| Percentage of LTC before recall program | 58.9(109/185) |

| Percentage of mortality | 1.6(3/185) |

| Percentage of LTC after recall program | 67.6(125/185) |

| Percentage of viremia in HCV antibody positive | 68.9(82/119) |

| Genotype (N=66), %(n) | |

| Type 1b, | 62.1(41) |

| Type 2 | 36.3(24) |

| Indeterminated | 1.5(1) |

| Fibrosis stage (N=58), %(n) | |

| F0 | 25.9(15) |

| F1 | 22.4(13) |

| F2 | 17.2(10) |

| F3 | 19.0(11) |

| F4 | 15.5(9) |

| Percentage of treatment in eligible patient | 95.1(78/82) |

| Antiviral drug, %(n) | |

| Interferon based | 46.2(36) |

| Interferon based then DAA | 3.8(3) |

| DAA | 53.8(39) |

| End of treatment response, % | 100(78/78) |

| Sustained viral response, % | 97.4(76/78) |

| Cured rate of eligible patient % | 92.7(76/82) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).