Submitted:

07 June 2024

Posted:

11 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

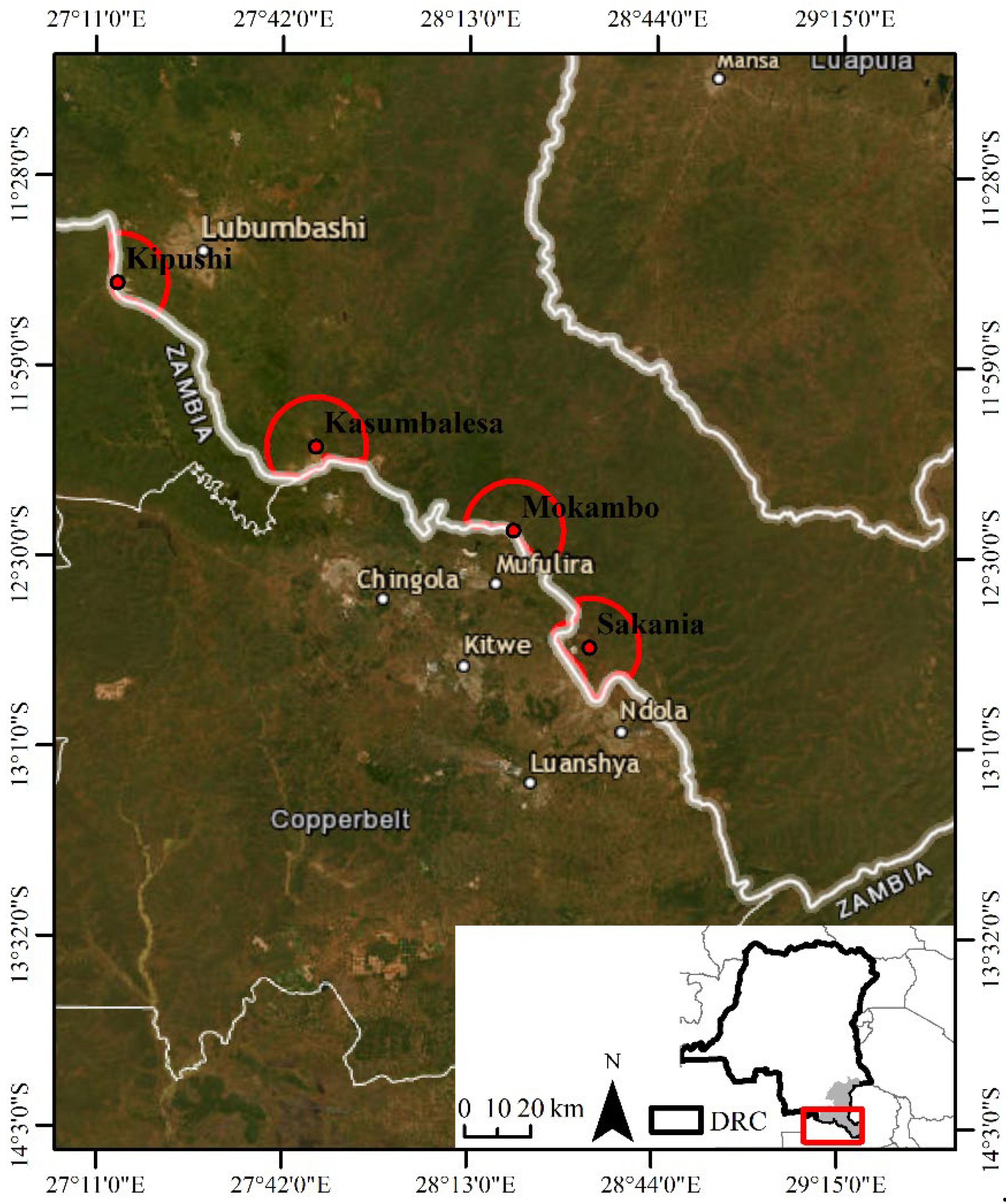

2.1. Study Area: Congolese Cities Bordering Zambia

2.2. Methodology

2.2.1. Data

2.2.2. Classification

2.2.3. Quantifying Urban Landscape Pattern Changes

3. Results

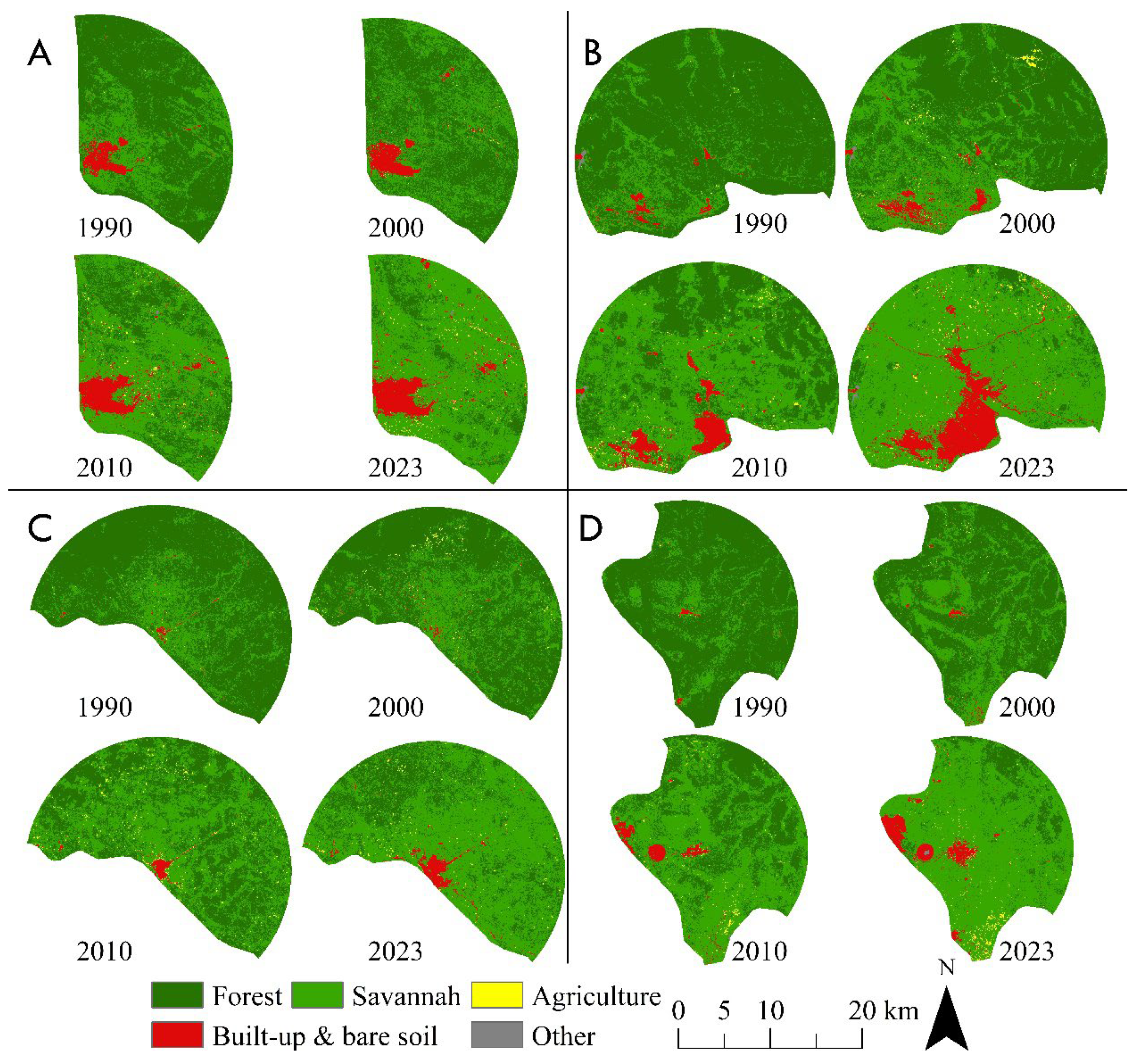

3.1. Classification Accuracy and Mapping

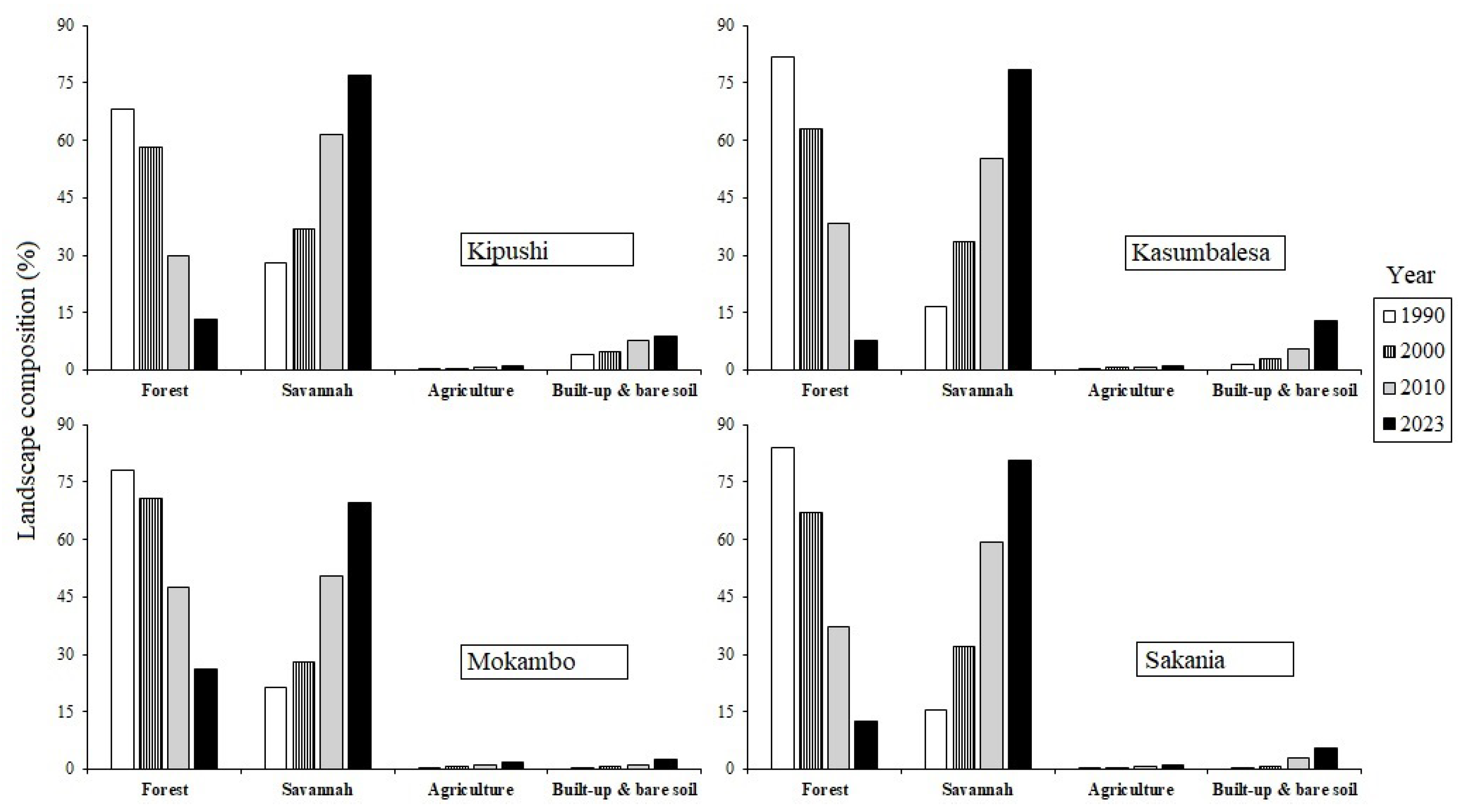

3.2. Landscape Composition Dynamics

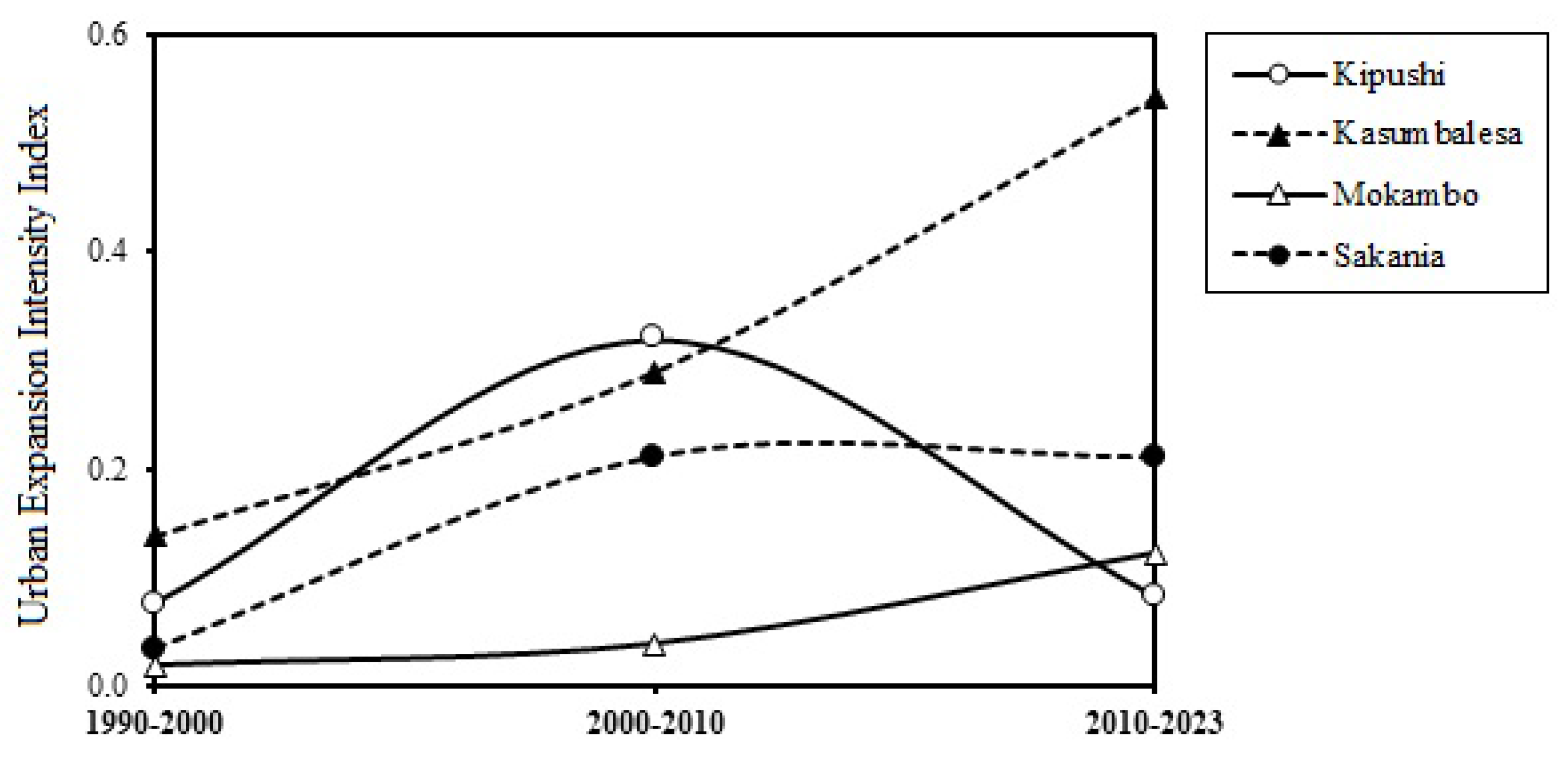

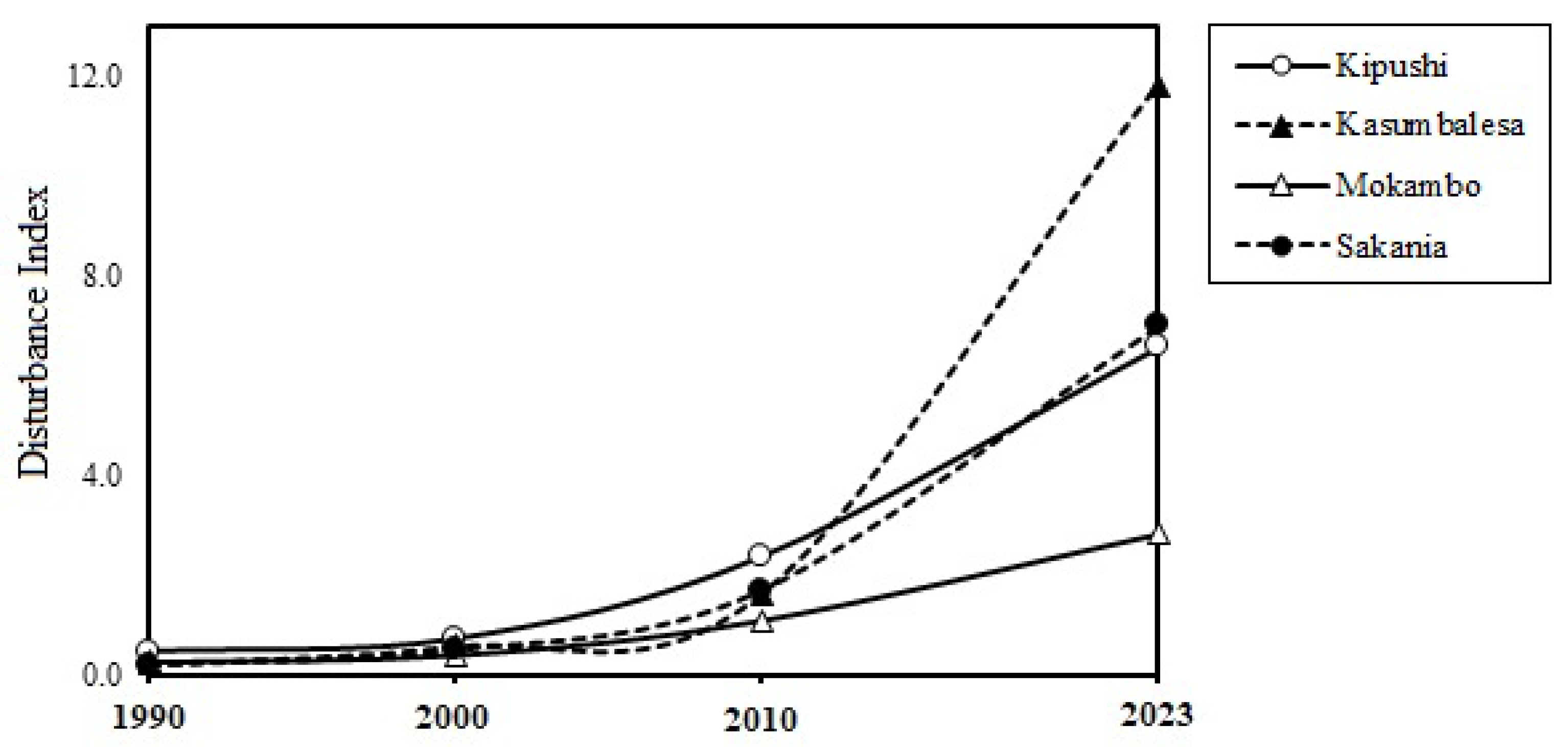

3.3. Intensity of Urban Expansion, Sprawl and Associated Landscape Anthropization

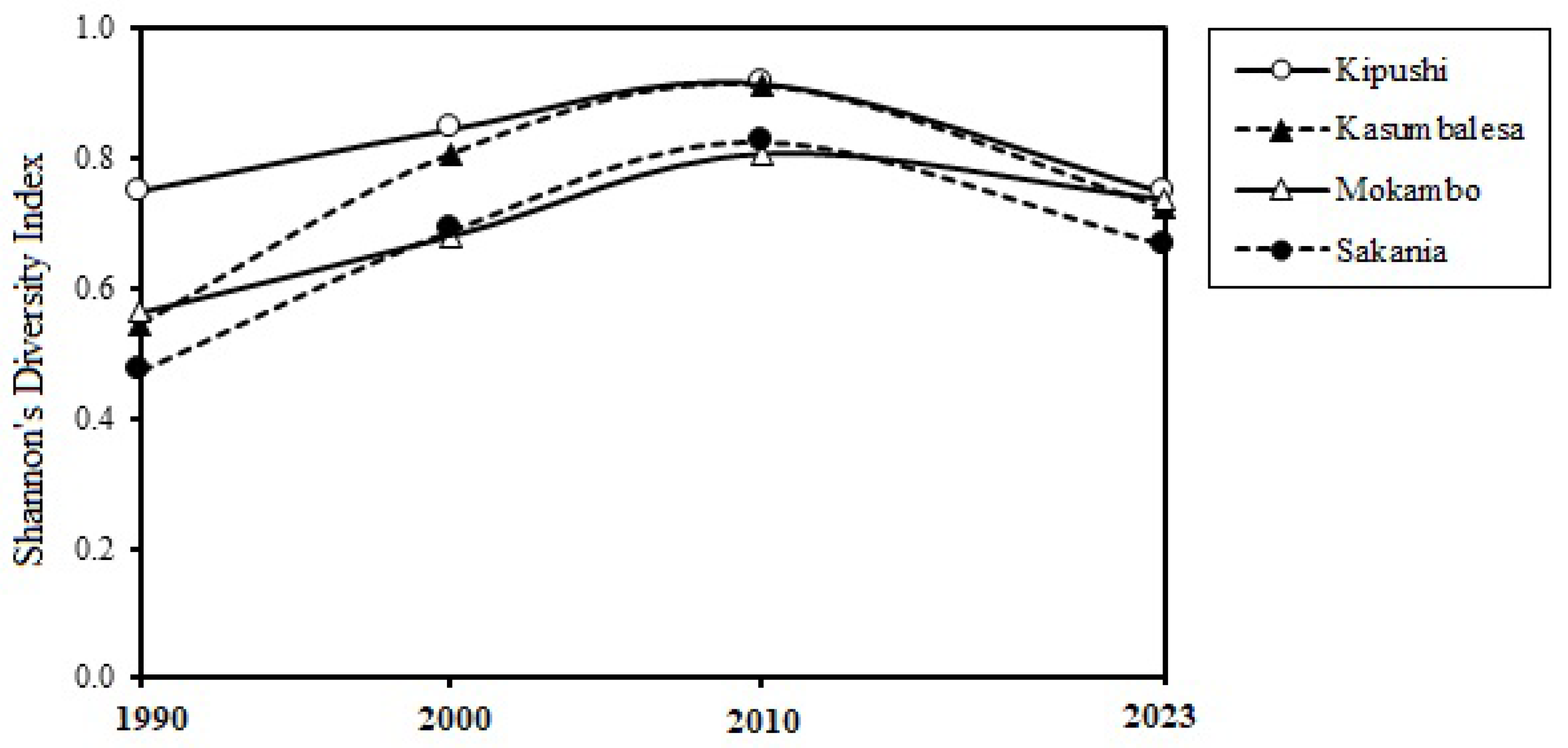

3.4. Analysis of Landscape Spatial Pattern Dynamics

4. Discussion

4.1. Methodology

4.2. Urban Expansion Intensity and Associated Landscape Dynamics

4.2. Implications for Regional Urban Planning

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hussain, M.; Imitiyaz, I. Urbanization concepts, dimensions and factors. International Journal of Recent Scientific Research 2018, 9, 23513–23523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, D.; Andreev, K.; Dupre, M.E. Major Trends in Population Growth Around the World. China CDC Weekly 2021, 3, 604–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cividino, S.; Halbac-Cotoara-Zamfir, R.; Salvati, L. Revisiting the “City Life Cycle”: Global urbanization and implications for regional development. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs. World Urbanization Prospects. In Demographic Research 2018,12. Available online: https://population.un.org/wup/Publications/Files/WUP2018-Report.pdf (accessed on 14 April 2024).

- Sinka, M.E.; Pironon, S.; Massey, N.C.; Longbottom, J.; Hemingway, J.; Moyes, C.L.; Willis, K.J. A new malaria vector in Africa: Predicting the expansion range of Anopheles stephensi and identifying the urban populations at risk. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2020, 117, 24900–24908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paz, J.A. Demographic Dynamics, Poverty, and Inequality. In: May, J.F.; Goldstone, J.A. (eds) International Handbook of Population Policies. International Handbooks of Population, Springer 2022, 11,. [CrossRef]

- Baye, F.; Adugna, D.; Mulugeta, S. Administrative failures contributing to the proliferation and growth of informal settlements in Ethiopia: The case of Woldia Township. Heliyon 2023, 9, e13758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlesinger, J.; Drescher, A.; Shackleton, C.M. Socio-spatial dynamics in the use of wild natural resources: Evidence from six rapidly growing medium-sized cities in Africa. Applied Geography 2015, 56, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stacey, P.; Lund, C. In a state of slum: Governance in an informal urban settlement in Ghana. Journal of Modern African Studies 2016, 54, 591–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieterse, E.; Parnell, S.; Haysom, G. African dreams: locating urban infrastructure in the 2030 sustainable developmental agenda. Area Development and Policy 2018, 3, 149–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugent, P. Border Towns and Cities in Comparative Perspective. A Companion to Border Studies 2012, 557–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobler, G. The green, the grey and the blue: A typology of cross-border trade in Africa. Journal of Modern African Studies 2016, 54, 145–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappellano, F.; Kurowska-Pysz, J. The mission-oriented approach for (cross-border) regional development. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimal, B.; Zhang, L.; Keshtkar, H.; Haack, B.N.; Rijal, S.; Zhang, P. Land use/land cover dynamics and modeling of urban land expansion by the integration of cellular automata and markov chain. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 2018, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soi, I.; Nugent, P. Peripheral Urbanism in Africa: Border Towns and Twin Towns in Africa. Journal of Borderlands Studies 2017, 32, 535–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peša, I. Crops and Copper: Agriculture and Urbanism on the Central African Copperbelt, 1950–2000. Journal of Southern African Studies 2020, 46, 527–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mususa, P. Mining, welfare and urbanisation: The wavering urban character of Zambia’s Copperbelt. Journal of Contemporary African Studies 2012, 30, 571–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabin, A.; Butcher, S.; Bloch, R. Peripheries, suburbanisms and change in sub-Saharan African cities. Social Dynamics 2013, 39, 167–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larmer, M. Permanent precarity: capital and labour in the Central African copperbelt. Labor History 2017, 58, 170–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubbers, B. Mining towns, enclaves and spaces: A genealogy of worker camps in the Congolese copperbelt. Geoforum 2019, 98, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baruah, N.G.; Henderson, J.V.; Peng, C. Colonial legacies: Shaping African cities. Journal of Economic Geography 2021, 21, 29–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwitwa, J.; German, L.; Muimba-Kankolongo, A.; Puntodewo, A. Governance and sustainability challenges in landscapes shaped by mining: mining forestry linkages and impacts in the Copper Belt of Zambia and the DR Congo. Forest Policy and Economics 2012, 25, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoji, M.H.; Nghonda, D.D.N.; Malaisse, F.; Waselin, S.; Sambiéni, K.R.; Kaleba, S.C.; Kankumbi, F.M.; Bastin, J.F.; Bogaert, J.; Sikuzani, Y.U. Quantification and Simulation of Landscape Anthropization around the Mining Agglomerations of Southeastern Katanga (DR Congo) between 1979 and 2090. Land 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuvelier, J.; Mumbund, P.M. Réforme douanière néolibérale, fragilité étatique et pluralisme normatif. Politique Africaine 2013, 129, 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wilderode, J.; Heijlen, W.; De Muynck, D.; Schneider, J.; Vanhaecke, F.; Muchez, P. The Kipushi Cu-Zn deposit (DR Congo) and its host rocks: A petrographical, stable isotope (O, C) and radiogenic isotope (Sr, Nd) study. Journal of African Earth Sciences 2013, 79, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Useni, S.Y.; Kaleba, S.C.; Khonde, C.N.; Mwana, Y.A.; Malaisse, F.; Bogaert, J.; Kankumbi, F.M. Vingt-cinq ans de monitoring de la dynamique spatiale des espaces verts en réponse á ('urbanisation dans les communes de la ville de Lubumbashi (Haut-Katanga, RD Congo). Tropicultura 2017, 35, 300–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez Lopez, J.M.; Heider, K.; Scheffran, J. Human and remote sensing data to investigate the frontiers of urbanization in the south of Mexico City. Data in Brief 2017, 11, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Min, X. Quantifying spatiotemporal patterns of urban expansion in China using remote sensing data. Cities 2013, 35, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.; Lin, T.; Jones, L.; Liu, X.; Xing, L.; Sui, J.; Zhang, J.; Ye, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, G.; Lu, X. Quantitatively assessing ecological stress of urbanization on natural ecosystems by using a landscape-adjacency index. Remote Sensing 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisa, P.; Christian, L.; Karen, B.; Blake, W. Armed conflict and cross-border asymmetries in urban development: A contextualized spatial analysis of Goma, Democratic Republic of the Congo and Gisenyi, Rwanda. Land Use Policy 2021, 109, 105711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabala, K.S.; Useni, S.Y.; Sambieni, K.R.; Bogaert, J.; Kankumbi, F.M. Dynamique des écosystémes forestiers de I'Arc Cuprifére Katangais en République Démocratique du Congo. I. Causes, transformations spatiales et ampleur. Tropicultura 2017, 35, 192–202. [Google Scholar]

- Malaisse, F. How to Live and Survive in Zambezian Open Forest (Miombo Ecoregion); Presses Agronomiques de Gembloux: Gembloux, Belgium, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Van Engelen, V.; Verdoodt, A.; Dijkshoorn, K.; Van Ranst, E. Soil and Terrain Database of Central Africa-DR of Congo, Burundi and Rwanda (SOTERCAF, version 1.0). ISRIC FAO, Report 2006, 7, 07.

- Potapov, P.V.; Turubanova, S.A.; Hansen, M.C.; Adusei, B.; Broich, M.; Altstatt, A.; Mane, L.; Justice, C.O. Quantifying forest cover loss in Democratic Republic of the Congo, 2000-2010, with Landsat ETM+ data. Remote Sensing of Environment 2012, 122, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabala, K.S.; Useni Sikuzani, Y.; Mwana, Y.A.; Bogaert, J.; Kankumbi, F.M. Pattern Analysis of Forest Dynamics of the Katangese Copper Belt Region in the Democratic Republic of the Congo: II. Complementary Analysis on Forest Fragmentation. Tropicultura 2018, 36, 621–630. [Google Scholar]

- Yamba, A.M.; Isabelle Vranken, Jules Nkulu, François Lubala Toto Ruananz, Daniel Kyanika, Scott Tshibang Nawej, Flori Mastaki Upite, Jean-Pierre Bulambo Mwema,; Bogaert, J. L’activité minière au Katanga et la perception de ses impacts à Lubumbashi, Kolwezi, Likasi et Kipushi. In Anthropisation des paysages katangais ; Presses Agronomiques de Gembloux: Gembloux, Belgium, 2018, p. 267.

- INS (Institut National de la Statistique). Anuaire statistique RDC 2022. Ministère National du Plan, Kinshasa, RD Congo, 2022, 433p.

- Chapa, F.; Hariharan, S.; Hack, J. A new approach to high-resolution urban land use classification using open access software and true color satellite images. Sustainability 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barima, Y.S.S.; Egnankou, W.M.; N’doumé, A.T.C.; Kouamé, F.N.; Bogaert, J. Modélisation de la dynamique du paysage fores- tier dans la région de transition forêt-savane à l’est de la Côte d’Ivoire. Télédétection 2010, 9, 129–138. [Google Scholar]

- Barima, Y.S.S.; Barbier, N.; Bamba, I.; Traoré, D.; Lejoly, J.; Bogaert, J. Dynamique paysagère en milieu de transition forêt-savane ivoirienne. Bois; Forêts Des Tropiques 2009, 299. [CrossRef]

- Mpanda, M.M.; Muteya, H.K.; Nghonda, D.D.N.; Sambiéni, K.R.; Malaisse, F.; Kaleba, S.C.; Bogaert, J.; Sikuzani, Y.U. Uncontrolled Exploitation of Pterocarpus tinctorius Welw. and Associated Landscape Dynamics in the Kasenga Territory: Case of the Rural Area of Kasomeno (DR Congo). Land 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Useni, S.Y.; Mpanda, M.M.; Malaisse, F.; Kaseya, P.K.; Bogaert, J. The Spatiotemporal Changing Dynamics of Miombo Deforestation and Illegal Human Activities for Forest Fire in Kundelungu National Park, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Fire 2023, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Useni, S.Y.; Mpanda Mukenza, M.; Khoji Muteya, H.; Cirezi Cizungu, N.; Malaisse, F.; Bogaert, J. Vegetation Fires in the Lubumbashi Charcoal Production Basin (The Democratic Republic of the Congo): Drivers, Extent and Spatiotemporal Dynamics. Land 2023, 12, 2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noi Phan, T.; Kuch, V.; Lehnert, L.W. Land cover classification using google earth engine and random forest classifier-the role of image composition. Remote Sensing 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olofsson, P.; Foody, G.M.; Herold, M.; Stehman, S.V.; Woodcock, C.E.; Wulder, M.A. Good practices for estimating area and assessing accuracy of land change. Remote Sensing of Environment 2014, 148, 42–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran, W.G. Sampling Techniques; John Wiley and Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Bogaert, J.; Ceulemans, R.; Salvador-Van Eysenrode, D. Decision Tree Algorithm for Detection of Spatial Processes in Landscape Transformation. Environmental Management 2004, 33, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O'Neill, R.V.; Krummel, J.R.; Gardner, R.E.A.; Sugihara, G.; Jackson, B.; DeAngelis, D.L.; Milne, B.T.; Turner, M.G.; Zygmunt, B.S.; Christensen, W.; Dale, V.H.; Graham, R.L. Indices of landscape pattern. Landscape ecology 1988, 1, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGarigal, K. FRAGSTATS help. University of Massachusetts: Amherst, MA, USA, 2015, 182.

- Useni, Y.S.; André, M.; Mahy, G.; Kaleba, S.C.; Malaisse, F.; Kankumbi, F.M.; Bogaert, J. Interprétation paysagère du processus d’urbanisation à Lubumbashi: Dynamique de la structure spatiale et suivi des indicateurs écologiques entre 2002 et 2008. In Anthropisation des Paysages Katangais; Presses Agronomiques de Gembloux: Gembloux, Belgium, 2018; 281p. [Google Scholar]

- Manesha, E.P.P.; Jayasinghe, A.; Kalpana, H.N. Measuring urban sprawl of small and medium towns using GIS and remote sensing techniques: A case study of Sri Lanka. Egyptian Journal of Remote Sensing and Space Science 2021, 24, 1051–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mama, A. ; Sinsin, B. ; De Cannière, C.; Bogaert,; J. Anthropisation et dynamique des paysages en zone soudanienne au nord du Bénin. Tropicultura 2013, 31, 78–88.

- de Haulleville, T. ; Rakotondrasoa, O.L. ; Rakoto Ratsimba, H. ; Bastin, J.F. ; Brostaux, Y. ; Verheggen, F.J., Rajoelison, G.L. ; Malaisse, F. ; Poncelet, M. ; Haubruge, É. ; Beeckman, H.; Bogaert, J. Fourteen years of anthropization dynamics in the Uapaca bojeri Baill. forest of Madagascar. Landscape and Ecological Engineering 2018, 14, 135–146. [CrossRef]

- Schug, F.; Okujeni, A.; Hauer, J.; Hostert, P.; Nielsen, J.; van der Linden, S. Mapping patterns of urban development in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, using machine learning regression modeling with bi-seasonal Landsat time series. Remote Sensing of Environment 2018, 210, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forget, Y.; Shimoni, M.; Gilbert, M.; Linard, C. Mapping 20 years of urban expansion in 45 urban areas of sub-Saharan Africa. Remote Sensing 2021, 13, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini, S.; Saber, M.; Rabiei-Dastjerdi, H.; Homayouni, S. Urban Land Use and Land Cover Change Analysis Using Random Forest Classification of Landsat Time Series. Remote Sensing 2022, 14, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyamekye, C.; Kwofie, S.; Ghansah, B.; Agyapong, E.; Boamah, L.A. Assessing urban growth in Ghana using machine learning and intensity analysis: A case study of the New Juaben Municipality. Land Use Policy 2020, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- York, A.M.; Shrestha, M.; Boone, C.G.; Zhang, S.; Harrington, J.A.; Prebyl, T.J.; Swann, A.; Agar, M.; Antolin, M.F.; Nolen, B.; Wright, J.B.; Skaggs, R. Land fragmentation under rapid urbanization: A cross-site analysis of Southwestern cities. Urban Ecosystems 2011, 14, 429–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, C.; Zhu, F.; Song, C.; Wu, J. Spatiotemporal pattern of urbanization in Shanghai, China between 1989 and 2005. Landscape Ecology 2013, 28, 1545–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacalone, M.; Turco, R.; Mosconi, E.M.; Alaimo, L.S.; Salvati, L. The Way Toward Growth: A Time-series Factor Decomposition of Socioeconomic Impulses and Urbanization Trends in a Pre-crisis European Region. Social Indicators Research 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhaug, H.; Urdal, H. An urbanization bomb? Population growth and social disorder in cities. Global Environmental Change 2013, 23, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacMillan, H. Mining, housing and welfare in South Africa and Zambia: An historical perspective. Journal of Contemporary African Studies 2012, 30, 539–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emuze, F.; Hauptfleisch, C. The Impact of Mining Induced Urbanization: A Case Study of Kathu in South Africa. Journal of Construction Project Management and Innovation 2014, 4, 882–894. [Google Scholar]

- Ebeke, C.H.; Ntsama Etoundi, S.M. The Effects of Natural Resources on Urbanization, Concentration, and Living Standards in Africa. World Development 2017, 96, 408–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, T. Urban fortunes and skeleton cityscapes: real estate and late urbanization in Kigali and Addis Ababa. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 2017, 41, 786–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arimah, B. Infrastructure as a Catalyst for the Prosperity of African Cities. Procedia Engineering 2017, 198, 245–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beeckmans, L.; Lagae, J. Kinshasa’s syndrome-planning in historical perspective: From Belgian colonial capital to self-constructed megalopolis. In Urban Planning in Sub-Saharan Africa, Routledge, 2015,pp. 223-246.

- Groupe Huit. Elaboration du plan urbain de référence de Lubumbashi. Rapport final Groupe Huit, BEAU, Ministère des ITR, RD Congo, 2009, 62p.

- Djeufack Dongmo, A.; Avom, D. Urbanization, civil conflict, and the severity of food insecurity in Africa. Politics & Policy 2024, 52, 140-168. [CrossRef]

- Forkuor, G.; Cofie, O. Dynamics of land-use and land-cover change in Freetown, Sierra Leone and its effects on urban and peri-urban agriculture - a remote sensing approach. International Journal of Remote Sensing 2011, 32, 1017–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tambwe, N.A. Urban agriculture, land sustainability. The case of Lubumbashi. In Bogaert, J.;; Halleux, J.M. (Eds). Territoires périurbains : développement, enjeux et perspectives dans les pays du sud. Les presses agronomiques de Gembloux, Gembloux, Belgique, 2015; 153-162.

- Bamba, I.; Yedmel, M.S.; Bogaert, J. Effets des routes et des villes sur la forêt dense dans la province orientale de la République Démocratique du Congo. European Journal of Scientific Research 2010, 43, 417–429. [Google Scholar]

- N’tambwe Nghonda, D.-d.; Muteya, H.K.; Kashiki, B.K.W.N.; Sambiéni, K.R.; Malaisse, F.; Sikuzani, Y.U.; Kalenga, W.M.; Bogaert, J. Towards an Inclusive Approach to Forest Management: Highlight of the Perception and Participation of Local Communities in the Management of miombo Woodlands around Lubumbashi (Haut-Katanga, D.R. Congo). Forests 2023, 14, 687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Useni, S.Y.; Boisson, S.; Cabala Kaleba, S.; Nkuku Khonde, C.; Malaisse, F.; Halleux, J.M.; Bogaert, J.; Munyemba Kankumbi, F. Dynamique de l'occupation du sol autour des sites miniers le long du gradient urbain-rural de la ville de Lubumbashi, RD Congo. Biotechnologie, Agronomie, Société et Environnement 2020, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Münkner, C.-A.; Bouquet, M.; Muakana, R. Elaboration du schéma directeur d’approvisionnement durable en bois-énergie pour la ville de Lubumbashi (Katanga). Programme Biodiversité et Forêts, RD Congo,2015, 68p.

- Sanga-Ngoie, K.; Fukuyama, K. Interannual and long-term of climate variability over the Zaïre basin during the last 30 years. Journal of Geophysical Research 1996, 110, 21351–21360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havyarimana, F.; Masharabu, T.; Kouao, JK.; Bamba, I.; Nduwarugira, D.; Bigendako, MJ.; Hakizimana, P.; Mama, A.; Bangirinama, F.; Banyankimbona, G.; Bogaert, J.; De canniere, C. La dynamique spatiale de la forêt située dans la réserve naturelle forestière de Bururi au Burundi. Tropicultura 2017, 35, 158–172. [Google Scholar]

- Bisiaux, F. ; Peltier, R. ; Muliele, JC. Plantations industrielles et agroforesterie au service des populations des plateaux Batéké, Mampu, en République Démocratique du Congo. Bois et Forêts Trop, 2009. [CrossRef]

- Toyi, M.S.; Barima, S.; Mama, A.; Andre, M.; Bastin, J.F.; De Cannière, C.; Brice, S.; Bogaert, J. Tree plantation will not compensate natural woody vegetation cover loss in the Atlantic Department of Southern Benin. Tropicultura 2013, 31, 62–70. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y. Use of exotic species during ecological restoration can produce effects that resemble vegetation invasions and other unintended consequences. Ecological engineering 2013, 52, 247–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaumbu, K.; Mubemba Mulambi Michel, M.; Emery Lenge Mukonzo, K.; Mylor, N.S.; Honoré, T.; Nkombe Alphonse, K.; Khasa, D. Early selection of tree species for regeneration in degraded woodland of southeastern Congo Basin. Forests 2021, 12, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, W.T.; Chigbu, U.E.; Duran-Diaz, P. Twenty years of building capacity in land management, land tenure and urban land governance. In: Home, R. (Ed.), Land Issues for Urban Governance in Sub-Saharan Africa. Springer, Cham, Switzerland 2021, pp. 121 – 136.

- Gwedla, N.; Shackleton, C.M. The development visions and attitudes towards urban forestry of officials responsible for greening in South African towns. Land Use Policy 2015, 42, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Useni, Y.S.; Malaisse, F.; Yona, J.M.; Mwamba, T.M.; Bogaert, J. Diversity, use and management of household-located fruit trees in two rapidly developing towns in Southeastern DR Congo. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 2021, 63, 127220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Land cover | Description | ROI (Polygons) |

|---|---|---|

|

Forest: Natural land cover, comprising patches of miombo woodland, dry dense forest, and gallery forest. | 170 |

|

Savannah: Generally anthropogenic land cover, characterized by low tree density and predominance of herbaceous cover. | 170 |

|

Agriculture: The anthropogenic land cover class consists of harvested agricultural lands, abandoned agricultural lands, or lands occupied by annual and off-season crops. | 120 |

|

Built-up & bare soil: Bare land and residential areas with minimal vegetation; impermeable surfaces or rarely paved roads. | 150 |

|

Other land cover: Water and unclassified spaces. | 90 |

| 1990-2000 | FR | SV | AG | BBS | OT | FR Loss | SV Gain | AG Gain | BBS Gain |

| Accuracy measure | |||||||||

| PA [%] | 99.09 | 100 | 98.97 | 93.58 | 100 | 98.05 | 100 | 98.06 | 93.58 |

| UA [%] | 100 | 99.02 | 96.04 | 97.14 | 100 | 99.01 | 97.06 | 98.06 | 97.14 |

| Overall accuracy [%] | 97.56 | ||||||||

| Stratified estimators of area ± CI [% of total map area] | |||||||||

| Area [%] | 18.14 | 18.23 | 9.12 | 9.29 | 9.20 | 8.94 | 8.67 | 9.65 | 8.76 |

| 95% CI | 0.42 | 0.00 | 0.35 | 0.00 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.38 | 0.54 | 0.30 |

| 2000-2010 | FR | SV | AG | BBS | OT | FR Loss | SV Gain | AG Gain | BBS Gain |

| Accuracy measure | |||||||||

| PA [%] | 99.00 | 94.42 | 98.99 | 98.00 | 96.00 | 98.11 | 98.10 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| UA [%] | 99.01 | 100.00 | 98.00 | 97.09 | 98.06 | 99.05 | 99.04 | 98.99 | 95.10 |

| Overall accuracy [%] | 97.40 | ||||||||

| Stratified estimators of area ± CI [% of total map area] | |||||||||

| Area [%] | 19.30 | 16.95 | 9.30 | 9.21 | 8.66 | 9.21 | 9.21 | 8.94 | 9.21 |

| 95% CI | 0.25 | 0.47 | 0.30 | 0.25 | 0.18 | 0.25 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.31 |

| 2010-2023 | FR | SV | AG | BBS | OT | FR Loss | SV Gain | AG Gain | BBS Gain |

| Accuracy measure | |||||||||

| PA [%] | 99.00 | 96.49 | 100.00 | 97.02 | 100.00 | 96.04 | 98.04 | 97.98 | 95.06 |

| UA [%] | 99.02 | 98.00 | 95.17 | 99.02 | 98.97 | 99.00 | 99.01 | 98.98 | 100.00 |

| Overall accuracy [%] | 96.30 | ||||||||

| Stratified estimators of area ± CI [% of total map area] | |||||||||

| Area [%] | 18.32 | 17.96 | 10.30 | 9.21 | 8.66 | 10.21 | 9.21 | 9.94 | 8.21 |

| 95% CI | 0.26 | 0.46 | 0.33 | 0.25 | 0.18 | 0.27 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.31 |

| Border city | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kipushi | Kasumbalesa | Mokambo | Sakania | |||||

| Indices | LPI | ENN | LPI | ENN | LPI | ENN | LPI | ENN |

| 1990 | ||||||||

| Forest | 63.84 | 68.54 | 79.75 | 68.40 | 74.67 | 67.01 | 82.43 | 67.08 |

| Savannah | 14.83 | 83.19 | 6.35 | 87.13 | 10.33 | 82.27 | 3.30 | 87.52 |

| Agriculture | 0.01 | 1986.84 | 0.00 | 530.87 | 0.00 | 263.60 | 0.00 | 438.33 |

| Built-up & bare soil | 3.09 | 210.96 | 0.21 | 220.15 | 0.16 | 303.63 | 0.15 | 271.01 |

| 2000 | ||||||||

| Forest | 53.53 | 64.60 | 49.44 | 71.96 | 66.30 | 66.33 | 64.16 | 73.56 |

| Savannah | 12.15 | 69.37 | 23.41 | 77.27 | 12.09 | 75.40 | 10.09 | 80.00 |

| Agriculture | 0.00 | 217.59 | 0.11 | 163.93 | 0.01 | 160.89 | 0.00 | 266.45 |

| Built-up & bare soil | 3.74 | 187.15 | 0.87 | 132.25 | 0.11 | 171.10 | 0.20 | 189.77 |

| 2010 | ||||||||

| Forest | 10.29 | 75.76 | 12.53 | 75.50 | 15.31 | 70.99 | 16.65 | 77.33 |

| Savannah | 55.22 | 67.24 | 48.43 | 73.97 | 43.32 | 71.58 | 52.43 | 73.17 |

| Agriculture | 0.05 | 163.54 | 0.02 | 151.23 | 0.01 | 156.72 | 0.04 | 183.45 |

| Built-up & bare soil | 5.84 | 119.31 | 2.43 | 153.99 | 0.70 | 289.83 | 0.90 | 171.13 |

| 2023 | ||||||||

| Forest | 3.02 | 88.55 | 1.14 | 99.56 | 13.69 | 77.15 | 3.96 | 91.52 |

| Savannah | 75.18 | 70.95 | 77.07 | 77.98 | 64.43 | 66.78 | 78.77 | 74.15 |

| Agriculture | 0.02 | 138.42 | 0.02 | 157.16 | 0.02 | 199.42 | 0.05 | 132.63 |

| Built-up & bare soil | 6.14 | 133.83 | 10.33 | 136.26 | 1.89 | 195.50 | 4.32 | 180.06 |

| Border city | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kipushi | Kasumbalesa | Mokambo | Sakania | |||||

| Indices | CA | NP | CA | NP | CA | NP | CA | NP |

| 1990 | ||||||||

| Forest | 209.0 | 2335.0 | 437.3 | 1567.0 | 332.1 | 1994.0 | 393.4 | 1431.0 |

| Savannah | 86.3 | 3869.0 | 89.0 | 5915.0 | 90.2 | 6010.0 | 73.1 | 5633.0 |

| Agriculture | 0.0 | 16.0 | 0.2 | 119.0 | 0.4 | 476.0 | 0.1 | 89.0 |

| Built-up & bare soil | 11.8 | 400.0 | 7.6 | 613.0 | 1.9 | 385.0 | 1.8 | 190.0 |

| 2000 | ||||||||

| Forest | 178.7 | 3032.0 | 336.2 | 4468.0 | 300.1 | 3009.0 | 314.5 | 2994.0 |

| Savannah | 113.6 | 6349.0 | 179.3 | 6844.0 | 119.1 | 7112.0 | 149.8 | 7039.0 |

| Agriculture | 0.6 | 546.0 | 3.9 | 1643.0 | 2.8 | 1683.0 | 0.6 | 552.0 |

| Built-up & bare soil | 14.1 | 644.0 | 14.9 | 1390.0 | 2.7 | 1206.0 | 3.4 | 917.0 |

| 2010 | ||||||||

| Forest | 91.4 | 4058.0 | 204.1 | 7081.0 | 201.7 | 5084.0 | 174.6 | 5855.0 |

| Savannah | 189.2 | 2717.0 | 295.4 | 3920.0 | 213.6 | 4162.0 | 277.2 | 3967.0 |

| Agriculture | 2.5 | 1582.0 | 4.6 | 2083.0 | 5.1 | 2091.0 | 3.4 | 1503.0 |

| Built-up & bare soil | 23.9 | 2132.0 | 30.4 | 1206.0 | 4.3 | 391.0 | 13.3 | 1141.0 |

| 2023 | ||||||||

| Forest | 40.7 | 4085.0 | 41.7 | 5211.0 | 111.1 | 8181.0 | 58.6 | 6040.0 |

| Savannah | 236.1 | 878.0 | 418.7 | 1147.0 | 299.3 | 2581.0 | 378.6 | 1387.0 |

| Agriculture | 3.0 | 1624.0 | 5.9 | 2191.0 | 6.2 | 2212.0 | 4.9 | 2189.0 |

| Built-up & bare soil | 27.2 | 1504.0 | 67.9 | 2428.0 | 11.0 | 697.0 | 26.0 | 924.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).