1. Introduction

The “Leave No One Behind” (LNOB) principle emphasises the importance of addressing multiple, intersecting inequalities that harm individuals’ rights [

1]. Intersecting inequality refers to the compounded disadvantages that arise from both the overlap of marginalised social categories (e.g., being female and living with a disability) and the intersection of multiple, mutually reinforcing dimensions of exclusion (e.g., deprivation in both health and education) [

2]. Meanwhile, the increasing adoption of AI tools in decision-making processes across various sectors, including health [

3], energy [

4], and housing [

5], underscores the urgency of ensuring fairness in their design and implementation [

6], as unfair AI systems may risk deepening existing inequalities.

AI fairness research spans various sectors, including healthcare [

7,

8,

9], finance [

10], and education [

11]. However, research on cross-sectoral intersecting AI fairness remains limited. The term “cross-sectoral intersecting" refers to the interaction and overlap of multiple sectors, such as healthcare, housing, and energy.

To address this gap, we propose quantifying cross-sectoral intersecting discrepancies between groups. These discrepancies refer to differences in user profiles across groups and can serve as a proxy for underlying inequalities, providing valuable insights for stakeholders. Additionally, the quantified discrepancies in data can offer insights into AI fairness when the data is used to train models. According to the LNOB principle of equal opportunities, everyone should ideally have equal access to public services and resources without discrepancies. We prefer the term “discrepancy” over “disparity” or “difference” because it suggests an unexpected difference.

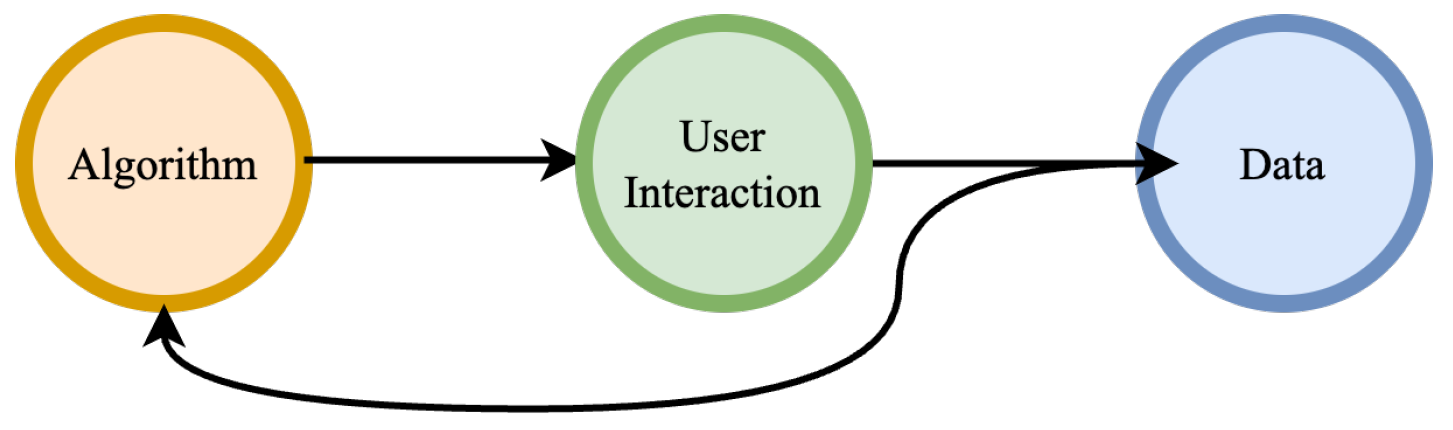

Bias and Fairness Recent studies highlight concerns that AI-supported decision-making systems may be influenced by biases [

12], which can unfairly impact vulnerable groups, such as ethnic minorities, emphasising the need for research on AI system fairness [

13]. A primary obstacle in advancing and implementing fair AI systems is the presence of bias [

14]. In AI, bias can originate from various sources, including data collection, algorithmic design, and user interaction, as illustrated in

Figure 1.

In particular, most AI systems rely on data for training and prediction. This close connection means that any inherent biases in the training data can be propagated and embedded into the AI systems, leading to biased predictions, the so called bias-in and bias-out. Even if the data itself is not inherently biased, algorithms can still exhibit biased behaviour due to inappropriate design and configuration choices. These biased outcomes can influence AI systems in real-world applications, creating a feedback loop where biased data from user interactions further trains and reinforces biased algorithms, resulting in a vicious cycle [

6].

Bias stemming from data is a crucial factor affecting fairness, as inappropriate handling of it may trigger a cascade of other biases, exacerbating fairness issues.

Discrepancy in data may indicate inequalities and lead to biases and unfairness, given that individuals should

ideally be treated

equally in ideal situations.

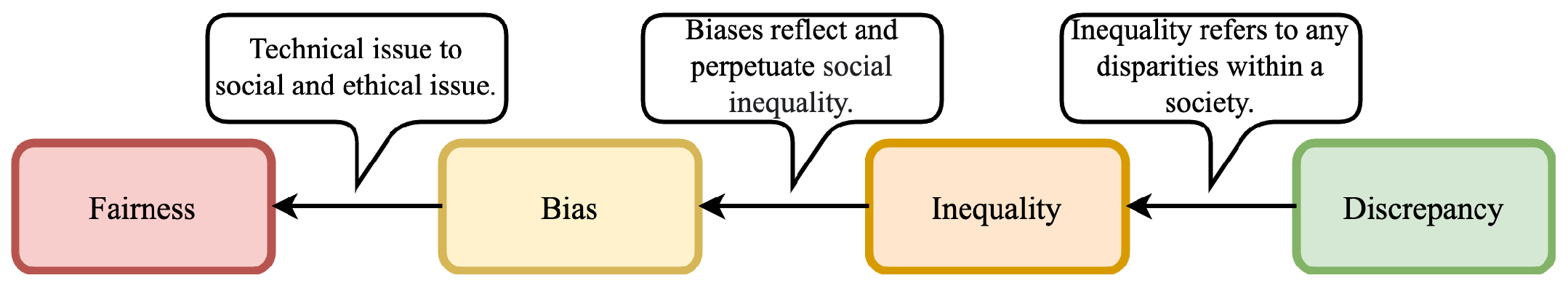

Figure 2 illustrates the correlations between fairness, bias, inequality, and discrepancy. Essentially, fairness is indirectly linked with discrepancy, and discrepancy can contribute to unfairness. The difference between fairness and bias is that the former can be viewed as a technical issue, while the latter can be viewed as a social and ethical issue [

14]. Furthermore, bias is a problem caused by historical and current social inequality [

15], and inequality can manifest as discrepancies.

Figure 2 starts with discrepancy and moves through inequality and bias to fairness. Therefore,

our research focuses on quantifying cross-sectoral intersecting discrepancies among different groups, with an aim to uncover insights or patterns related to inequality, bias, and AI fairness.

Background and Motivation Currently, there is limited research focusing on quantifying discrepancies. Most recent research on quantifying bias and/or inequality primarily revolves around resource allocation strategies and generally relies on objective data (e.g., [

16]). However, these approaches have limitations and face challenges in effectively assessing and measuring bias or discrepancy in datasets unrelated to resource allocation. For example, in social sciences, much data is collected through questionnaires, which often include binary, categorical, or ordinal data types related to subjective responses and user experiences. These questionnaires may cover various aspects, resulting in intersecting and cross-sectoral data of high dimensions. Analysing data based on no more than two dimensions or sectors may overlook important information or patterns. Therefore, we believe that quantifying cross-sectoral intersecting discrepancies is valuable, as it can provide comprehensive insights.

The

Anonymous project

1 aims to establish safer online environments for minority ethnic (ME) populations in the UK. Its survey questionnaire covers five key aspects: demography, energy, housing, health, and online services. Notably, the data collected in this context does not directly pertain to resource allocation, making it challenging to explicitly define and detect bias within the data using current methods, despite the presence of discrepancies. These discrepancies may arise from various factors, including culture, user experience, and discrimination, potentially contributing to bias or unfairness. This research is mainly motivated by the

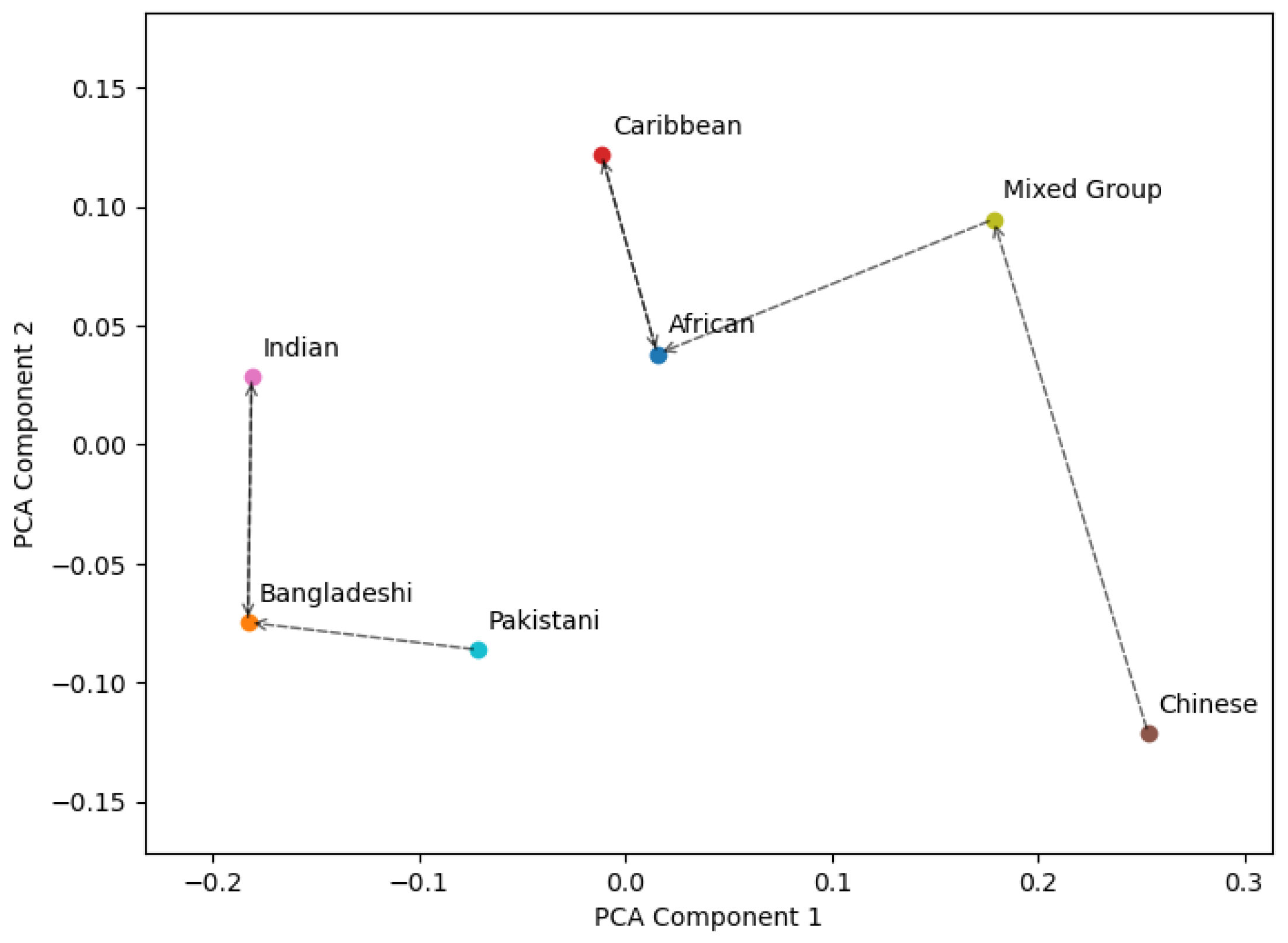

Anonymous project, so the datasets we used primarily cover the health, energy, and housing sectors, with our research targeting ME groups.

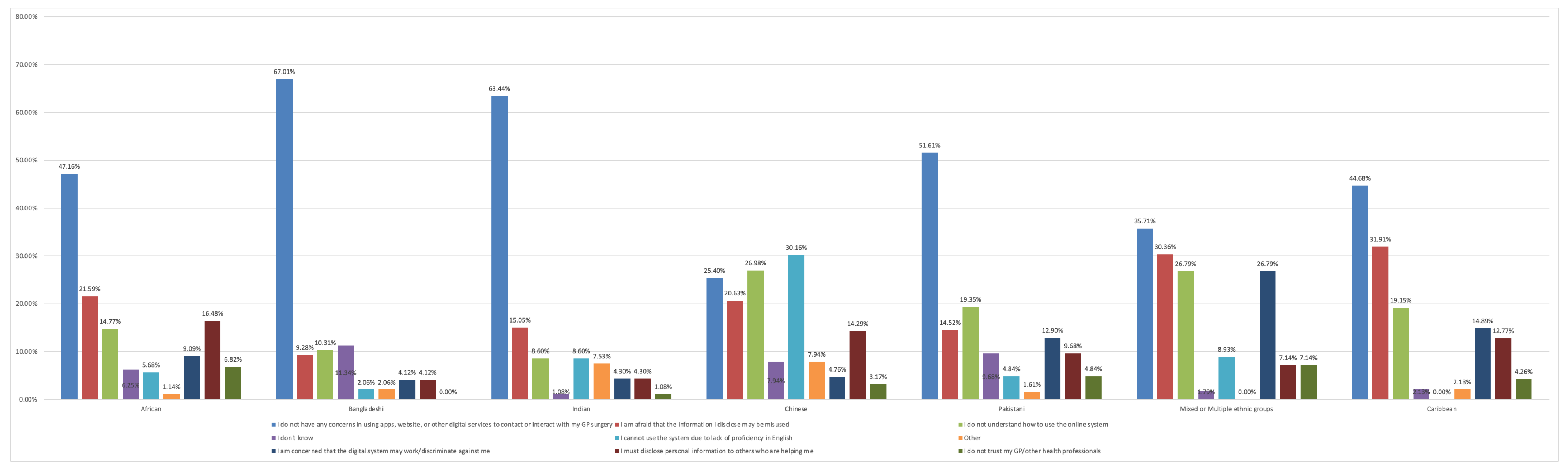

In our preliminary research (see

Appendix A) in England, based on a

Anonymous project survey question regarding health and digital services

2, we observed a notable discrepancy in the Chinese group: 30.16% lacked English proficiency and 26.98% struggled to use the online system, while most other ethnic groups reported less or no concerns. These discrepancies, stemming from cultural differences, user experiences, or discrimination, contribute to inequality and may affect AI fairness. For instance, an AI system might inappropriately assume that only Chinese individuals require English language support, thereby neglecting other ME groups who may also need assistance.

However, investigating multiple and cross-sectoral questions simultaneously is challenging. For instance, the

Anonymous project’s data contains similar questions for the energy and housing sectors, and current methods struggle to analyse these sectors jointly. Therefore, we propose an approach to quantify intersecting and cross-sectoral discrepancies for multiple ethnic groups by leveraging latent class analysis (LCA) [

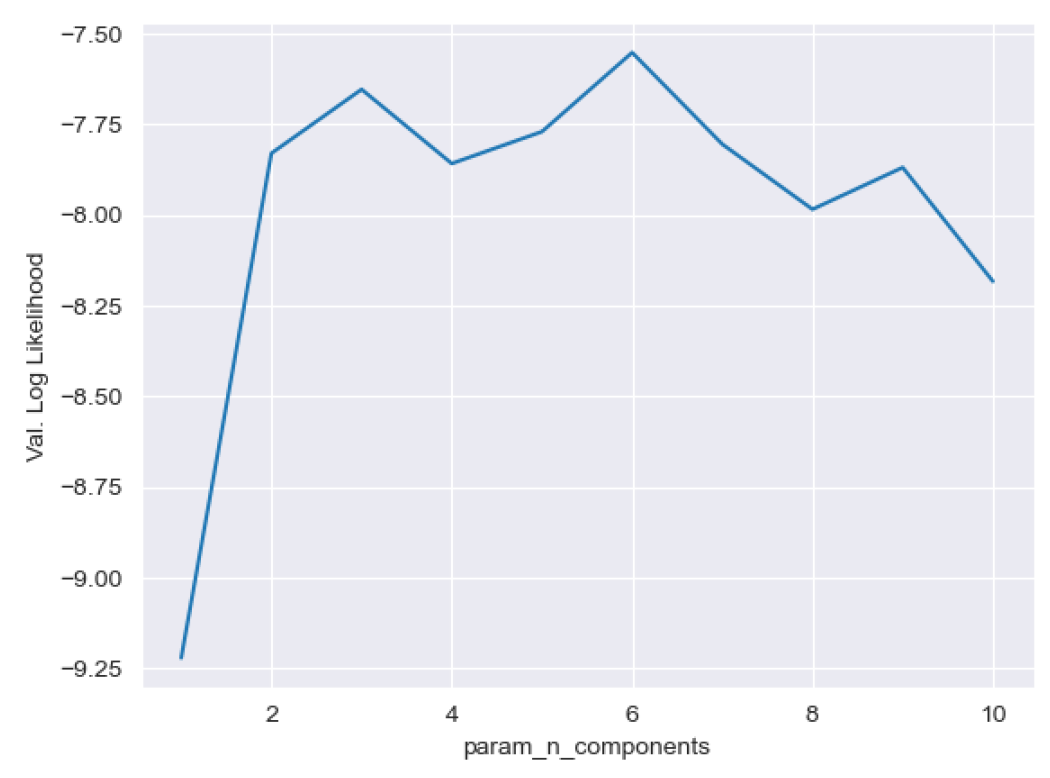

17].

LCA is a popular method in social science [

18] because it can identify latent groups within a population based on observed characteristics or behaviours. LCA offers a flexible framework for exploring social phenomena and integrating with other analytical techniques. In this research, we use LCA to cluster intersecting and cross-sectoral data, encompassing questions across the health, energy, and housing sectors. This method enables us to derive latent classes and outcomes, with each class describing a distinct cross-sectoral user profile. This approach moves beyond defining user classes solely based on individual questions. More details of our proposed approach are presented in

Section 2, with experiments and results reported in

Section 4.

The main contributions of this research are as follows: (1) we propose a novel and generic approach to quantify intersecting and cross-sectoral discrepancies between user-defined groups; (2) our findings reveal that ME groups cannot be treated as a homogeneous group, as varying discrepancies exist among them; and (3) we demonstrate how the proposed approach can be used to provide insights to AI fairness.

2. Quantifying the Cross-Sectoral Intersecting Discrepancies

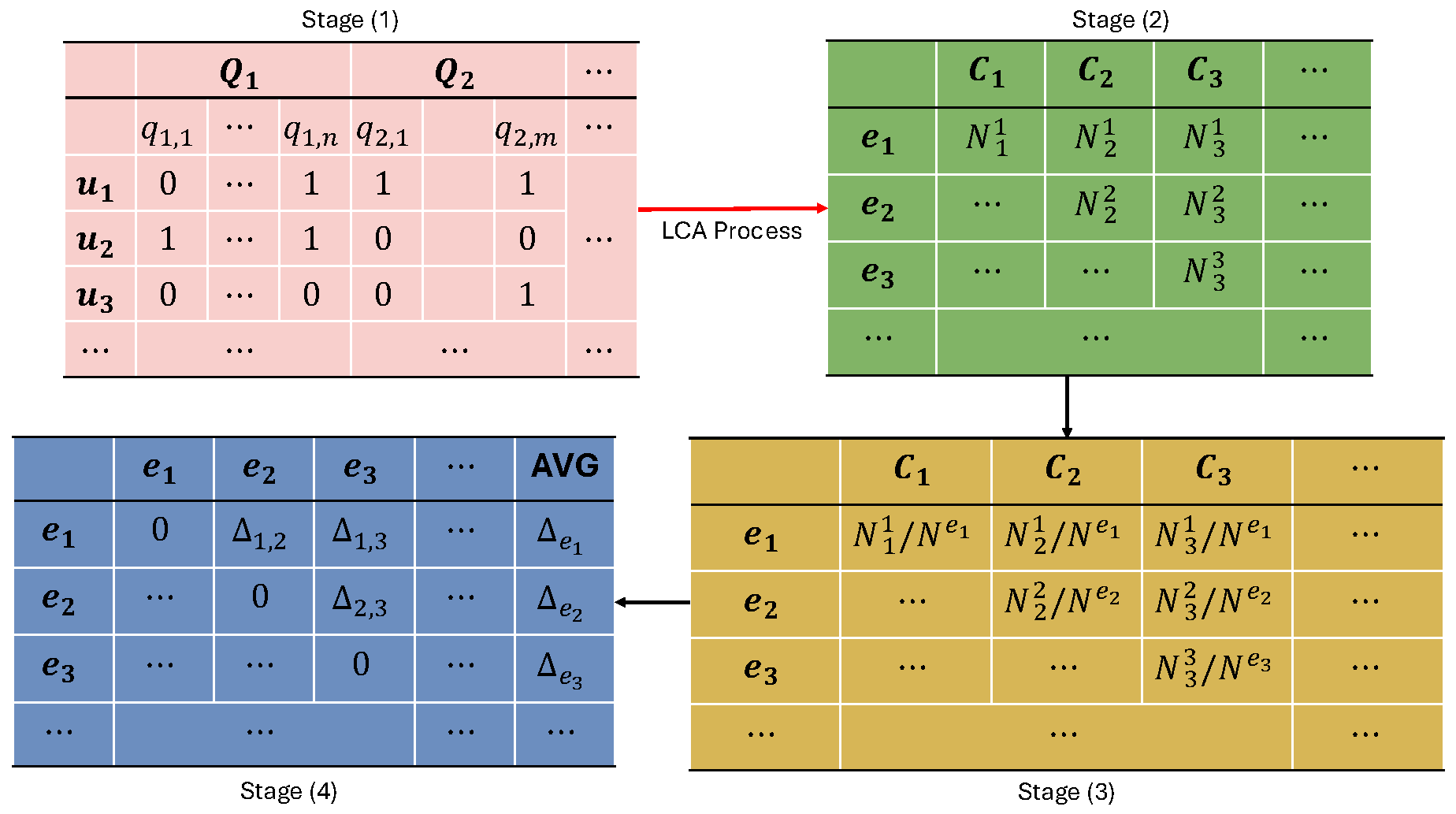

The overall workflow of the proposed approach is shown in

Figure 3, using a binary-encoded survey data as an example. It is noted that our approach is not limited to this specific format and can be applied to a wide range of similar problems. We will present more experiments with other datasets in

Section 4 to further validate and showcase the features of our approach.

In

Figure 3, Stage (1) illustrates the binary-encoded data

D, where

represents the selected survey questions, covering user experiences across different sectors. Similarly,

denotes the set of survey respondents. Here,

q represents the response options; for example,

refers to the first option for

. A value of `1’ indicates a selected option, while `0’ signifies that it was not selected. Each respondent’s responses can be represented as a vector

. The set of all indicator variables is denoted by

X, with

, where

is the space of all possible response vectors. For other datasets, the encoding method should be selected based on the data format and type. The red arrow in

Figure 3 illustrates the LCA process

3, which includes hyperparameter selection and model fitting.

For simplicity, the LCA process is defined in Equation (1), where

and

specify the marginal distribution of the latent classes

C and the class-conditional distribution of the indicator variables

X, respectively. Here,

, and each latent class is denoted by

c. In fact, the LCA is specified by a set of

, where

.

The advantage of using LCA is straightforward: it considers the joint probability distribution of all variables. This means potential inequalities or discrepancies can be analysed jointly. Once we obtain the distributions of latent classes

over user-defined groups

(as shown in

Figure 3 Stage (2)), we can calculate the discrepancy

.

Quantification of Discrepancy Let us denote the size of the dataset as N, where represents an individual sample. Concurrently, let denote a latent class, with the total number of classes being , and let represent the count of samples classified into latent class c. To quantify the discrepancies, it is necessary to establish a grouping variable G, which can be defined based on factors such as ethnicity, age, or income level. Here, denotes the total number of user-defined groups, represents one specific group within this set, denotes the number of individuals from group e, and denotes the number of individuals from group e assigned to the class c.

To initiate the quantification process, the proportions r of samples from each user-defined group within each latent class need to be calculated, as detailed in Line 6 in Algorithm 1. This calculation can be performed using . The reason for calculating r is that user-defined groups may have different numbers of samples; therefore, using percentages for subsequent analyses ensures fairness and consistency.

Subsequently, we can derive a matrix of results characterised by dimensions

, as shown in

Figure 3 (3). Within this matrix, each row corresponds to the proportions of samples from a specific group within each latent class. It is important to note that in this context, each latent class effectively represents an individual user profile and can be viewed as a distinctive feature. Consequently, each row within the matrix may be employed as a feature vector denoted as

, serving as a representation of a specific group within the feature space.

In the assessment of discrepancy between two feature vectors, various methods may be employed, including the Euclidean distance, Kullback-Leibler Divergence, Earth Mover’s Distance, and Manhattan Distance, among others. In our approach, we propose the utilisation of Cosine Similarity to calculate the discrepancy, which is defined as

. Finally, we can iteratively calculate

between any pairs of vectors

and obtain the discrepancy matrix

S (as shown in Stage (4) of

Figure 3). The AVG column in Stage (4) contains the mean discrepancy values for

e, which can be viewed an approximation for how each

e is different from others.

|

Algorithm 1 Quantifying the Intersecting Discrepancies within Multiple Groups |

- 1:

Input: D and G

- 2:

Initialise M

- 3:

Estimate M based on D

- 4:

for

e

in

G

do

- 5:

for c in C do

- 6:

- 7:

end for

- 8:

end for - 9:

for

e

in

G

do

- 10:

for in G do

- 11:

- 12:

end for

- 13:

end for - 14:

Output: Discrepancy matrix S of size

|

We suggest the use of Cosine Similarity due to its inherent characteristics, including a natural value range spanning from 0 to 1 as and contain no negative values. Importantly, it does not necessitate additional normalisation procedures. This metric, possessing with a fixed value range, enhances comparability and offers support to subsequent AI fairness research. The proposed approach is summarised in Algorithm 1.

3. Related Work

Quantifying and improving AI fairness As AI technologies are used more and more frequently in real life, people’s concerns about the ethics and fairness of AI have always existed, especially when AI is increasingly used in problems with sensitive data [

19]. Morley et al. [

13] and Garattini et al. [

20] noticed that an algorithm “learns” to prioritise patients it predicts to have better outcomes for a particular disease. And they also noticed that AI models have discriminatory potential when facing ME groups on health. Therefore, people are paying more and more attention on the impact and mitigating methods of AI bias.

Wu et al. [

16] proposes the allocation-deterioration framework for detecting and quantifying health inequalities induced by AI models. This framework quantifies inequalities as the area between two allocation-deterioration curves. They conducted experiments on synthetic datasets and real-world ICU datasets to assess the framework’s performance and applied the framework to the ICU dataset and quantified the unfairness of AI algorithms between White and Non-White patients. So et al. [

21] explores the limitations of fairness in machine learning and proposes a reparative approach to address historical housing discrimination in the US. In that work, they used contemporary mortgage data and historical census data to conduct case studies to demonstrate the impact of historical discrimination on wealth accumulation and estimate housing compensation costs. They then proposed a remediation framework that includes analysing historical biases, intervening in algorithmic systems, and developing machine learning processes that reduce correct historical harms.

Latent Class Analysis (LCA) is a statistical method based on mixture models and often used to detect potential or unobserved heterogeneity in samples [

22]. By analysing response patterns of observed variables, LCA can identify potential subgroups within a sample set [

23]. The basic idea of LCA is that some parameters of a postulated statistical model differ across unobserved subgroups, forming the categories of a categorical latent variable [

24]. In 1950, Lazarsfeld [

25] introduced LCA as a means of constructing typologies or clusters using dichotomous observed variables. Over two decades later, Goodman [

26] enhanced the model’s practical applicability by devising an algorithm for obtaining maximum likelihood estimates of its parameters. Since then, many new frameworks have been proposed, including models with continuous covariates, local dependencies, ordinal variables, multiple latent variables, and repeated measures [

24].

Because LCA is a person-centered mixture model, it is widely used in sociology and statistics to interpret and identify different subgroups in a population that often share certain external characteristics from data [

27]. However, in social sciences, LCA is used in cross-sectional and longitudinal studies. For example, in relevant studies in psychology [

28], social sciences [

29], and epidemiology [

30], mixed models and LCA can be used to establish probabilistic diagnoses when no suitable gold standard is available [

17].

In [

28], the relationship between cyberbullying and social anxiety among Hispanic adolescents was explored. The sample consisted of 1,412 Spanish secondary school students aged 12 to 18 years. There were significant differences in cyberbullying patterns across all social anxiety subscales after applying LCA. Compared with other profiles, students with higher cyberbullying traits scored higher on social avoidance and distress in social situations, as well as lower levels of fear of negative evaluation and distress in new situations. Researchers in [

29] developed a tool, using LCA, to characterise energy poverty without the need to arbitrarily define binary cutoffs. The authors highlight the need for a multidimensional approach to measuring energy poverty and discuss the challenges of identifying vulnerable consumers. The research in [

30] aimed to identify subgroups in COVID-19-related acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and compare them with previously described ARDS subphenotypes by using LCA. The study found that there were two COVID-19-related ARDS subgroups with differential outcomes, similar to previously described ARDS subphenotypes.

5. Discrepancy for AI Fairness

As we discussed earlier, our proposed approach can be used to quantify the discrepancies in the distribution of user (sample) profiles across multiple groups. We consider that these discrepancies can negatively impact the fairness of machine learning methods. Intuitively, the training process of machine learning models may struggle to extract patterns equally from two parts of a dataset with significant discrepancies. We expect that the discrepancy can serve as a data exploratory metric to alert AI users to the risk of fairness issues and support fairness analysis in AI.

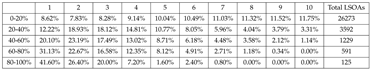

5.1. Predefined Range Groups (Fixed Intervals)

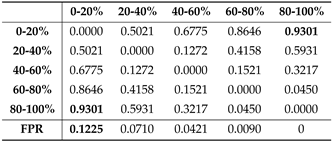

Now, we will show how discrepancies relate to potential AI bias. We selected logistic regression (LR) to classify deprivation indices for LSOAs using the Census 2021 data from previous experiments. To simplify the classification task, we redefined the deprivation indices as deprived (indices 1-5, labelled as 0) and not deprived (indices 6-10, labelled as 1). We randomly split the dataset into training and validation sets in an 8:2 ratio, and the experiments are repeated for 10 times.

The bias is measured using the False Positive Rate (FPR). In this study, we argue that FPR deserves greater attention, as it quantifies the extent to which deprived areas are incorrectly predicted as not deprived. Such misclassification could potentially exacerbate deprivation. For instance, groups with higher FPR may not receive the deserved attention they need from the government when it comes to resource allocation decisions.

The experimental results indicate that the two groups with the largest discrepancy values exhibit the greatest difference in FPR. As shown in

Table 4, the discrepancy between the 0-20% group and the 80-100% group is the largest with the value 0.9301. At the same time, the former group has the smallest FPR of 0, while the latter group has the largest FPR of 0.1225. This study reveals that the machine learning model can treat areas predominantly populated by non-ethnic minorities unfairly. Moreover, significant discrepancies between groups within a dataset warrant attention, as these disparities may lead to differential treatment by machine learning models.

5.2. Equal-Size Groups (Quantile-Based)

We observed that the grouping method employed in the aforementioned experiments presents a data imbalance issue, as the 0-20% group constitutes 82.59% of the LSOA samples. This imbalance may undermine the robustness of our findings, given the significant decrease in the number of samples from the 0-20% group to the 80-100% group. Consequently, the 80-100% group may achieve a 0 FPR with a small number of test samples, despite having a limited amount of training data.

To address this issue, we propose an alternative grouping method. First, we calculate the ME population percentages for all LSOAs, then sort and divide them into five groups, ensuring each group contains an equal number of samples. The ME population percentage ranges for these groups are as follows: 0-0.96%, 0.96-2.33%, 2.33-6.16%, 6.16-17.34%, and 17.34-95.02%. These groups are labeled as 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5, respectively. It is worth noting that the average ME population percentage in the UK is 18%, indicating that only the last group can be considered representative of the ME population.

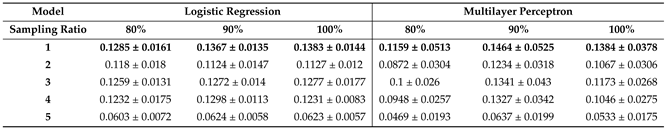

To further explore the correlations between discrepancy and AI fairness, we conducted experiments using two models: LR and a Multilayer Perceptron (MLP). Additionally, we applied two sampling ratios (90% and 80%) to randomly generate two new datasets. From our perspective, the sampled datasets should preserve the patterns discussed in the previous section, as random sampling does not substantially alter the overall distribution. All the results presented in

Table 5 and

Table 6 are derived from experiments repeated 10 times.

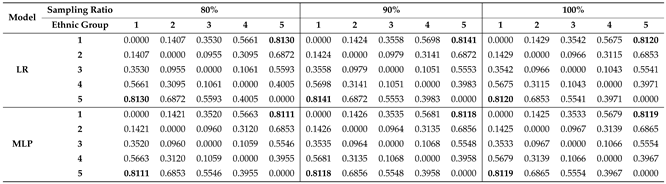

In

Table 5, we observed that the discrepancies between Groups 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 have increased compared to the values presented in

Table 4. We believe this is due to all ME LSOAs being concentrated in group 5 under the new grouping method, which explains this observation. In other words, the ME group and non-ME groups have differences in their user profiles. Meanwhile, the largest discrepancy remains between group 1 (predominantly non-ME) and Group 5 (predominantly ME) across the two sampled datasets (70% and 80%) and the original dataset (100%). In

Table 5, “LR" and “MLP" indicate that the discrepancy calculations were performed on independently sampling datasets. The datasets are used to observe the correlations between discrepancy and AI bias.

In

Table 6, the first group (predominantly non-ME), approximately equivalent to the 0-20% group in

Table 4, still exhibits the largest FPR across both models and all three datasets. Meanwhile, Group 5 continues to have the smallest FPR. Thus, the results align with the findings presented in

Section 5.1; the two groups with large discrepancy values may be treated differently by AI.

Additionally, compared to the results shown in

Table 4, we observe that the FPR values for Groups 2∼4 increase along with the increase of discrepancy values between Groups 2∼4 and Group 5. Meanwhile, the overall discrepancies within Groups 2∼4 are smaller than the discrepancies between Group 5 and the other groups (Groups 1∼4). This indicates that the features of the data for Groups 2∼4 are relatively similar, and models treat them similarly. As shown in

Table 4, Groups 1∼4 received relatively similar FPRs, while the FPR for Group 5 is significantly smaller. In summary, we believe our proposed method effectively quantifies the discrepancies between different groups. Additionally, these values are important for informing AI users and highlight potential risks of AI unfairness.

6. Conclusion and Limitations

In conclusion, the issue of AI fairness is of paramount importance and warrants attention from all stakeholders. In our research, we addressed this challenge by focusing on quantifying the discrepancies present in data, recognising that AI models heavily rely on data for their performance. Our proposed data-driven approach is aligned with the LNOB initiative, as it aids in discovering and addressing discrepancies between user-defined groups, thus contributing to efforts to mitigate inequality. Moreover, we believe that our proposed approach holds promise for applications across a broad spectrum of tasks, offering insights to develop fair AI models. Through testing on three datasets, we have demonstrated the efficacy and informativeness of our approach, yielding satisfactory results. Our proposed approach can be considered as an approximation of bias, as selecting different parameters for LCA may yield slightly varying results, to address this we have done hyperparameter optimisation.

In summary, our research represents a significant step towards promoting fairness in AI and offers an innovative avenue for social science research. By highlighting data-driven approaches and their alignment with broader societal initiatives, we aim to foster a more equitable and inclusive landscape for AI development and deployment.