1. Introduction

The term “medical error” is quite often used to refer to mistakes committed in the provision of healthcare services which has caused harm to a patient[

1,

2]. In the midst of advances in scientific knowledge and with the problems in Brazil’s healthcare system, establishing a close relationship between doctor and patient is one of the greatest challenges of modern medicine. The ideal doctor-patient relationship can be conceptualized as a relationship of a professional nature, reciprocal reliability, honesty, rights and duties of both doctor and patient, and one which is imbued with humanism and compassion for those suffering.

2. Objective

Considering the judicialization of health and its impact on our society, our objective is to analyze civil cases of medical error in the area of pediatrics and adolescence, evaluating: 1) causal link; 2) type of medical error; 3) conviction of the court and its legal basis; 4) correlation between medical expert’s understanding and legal understanding.

3. Materials and Method

Retrospective analysis of 60 pediatric/adolescent forensic medical examinations carried out by pediatric medical expert between April 2009 and February 2014 at the Institute of Medicine and Criminology of the State of São Paulo (IMESC).

Only one medical expert had the prerequisites. During this period, 1,308 expert’s reports were carried out, out of which 230 dealt with civil lawsuits related to medical error, 76 fell within the age range of the study, and 60 had first instance judgment on the digital system of the São Paulo State Court website. The latter are the subjects of our study.

For analyzing the expert’s reports, we distributed them per age, gender, type of expert’s report (indirect or direct), conclusion of expert’s report (causal link between medical conduct and the complaint or not), type of medical error (negligence, recklessness, malpractice), court sentence in the first instance (if in accordance with the expert’s report), and the reasoning of the judgment as being objective or subjective (type of law).

The causal link was described to the judge as good or bad medical practice, in accordance with evidence-based medicine and medical guidelines. As for the type of medical error, it was described to the judge, with no judgment or classification criteria (negligence, recklessness or malpractice) applied to the expert’s report.

Cases with a conclusion of medical malpractice were classified as having a causal link. Cases of good medical practice were classified as having no causal link.

The time elapsed between the filing of the lawsuit, medical examination, and the publication of the judgment was also assessed.

Indirect expert examinations involved analyzing medical records, given the subject had already died. Direct examinations, on the other hand, included, in addition to analyzing medical records, conducting an anamnesis and a physical examination.

Then, an intersection between court ruling, analysis of the medical practice, and the legal bases was carried out.

For the sake of data uniformity, the expert examinations evaluated were carried out by the same legal expert. The years between 2009 and 2014 was the chosen period of time.

The statistical analysis consisted of the distribution of nominal variables (frequency) in a descriptive study.

4. Results

Of the 60 expert examinations analyzed, 29 were female and 31 were male. The age of subjects examined ranged from 2 minutes to 15 years of age, with a median of 3.5 years.

The time between the filing of the lawsuit and the expert’s examination ranged from 0.6 to 8.8 years, with a median of 2.37 years. The time between the expert’s report and the decision of the court in the first instance ranged from 0.3 to 11.6 years. The time between filing of the lawsuit and the sentencing ranged from 0.8 to 12.3 years.

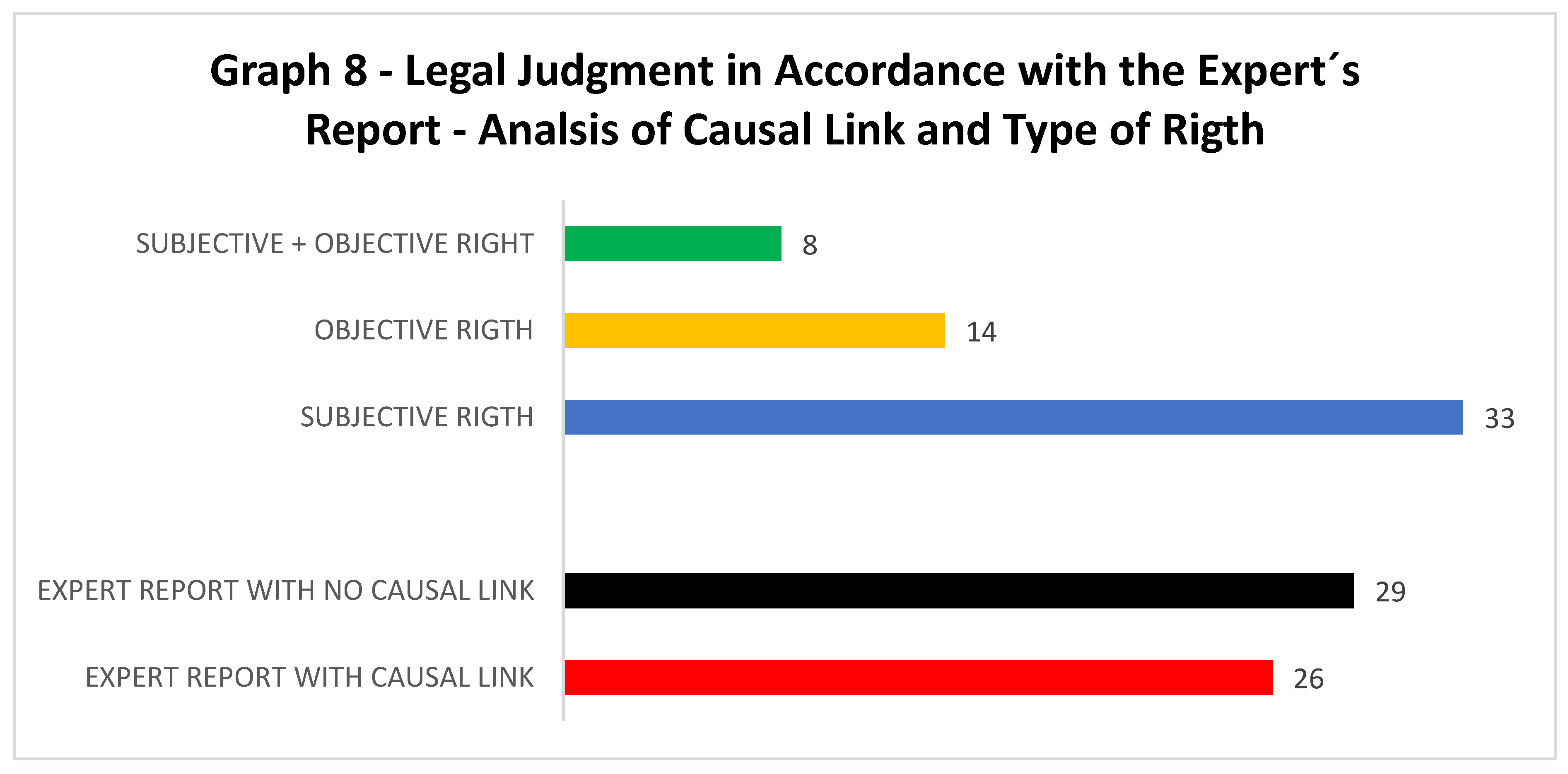

Most expert’s examinations (65%) were indirect, i.e. an analysis of the death event (

Graph 1).

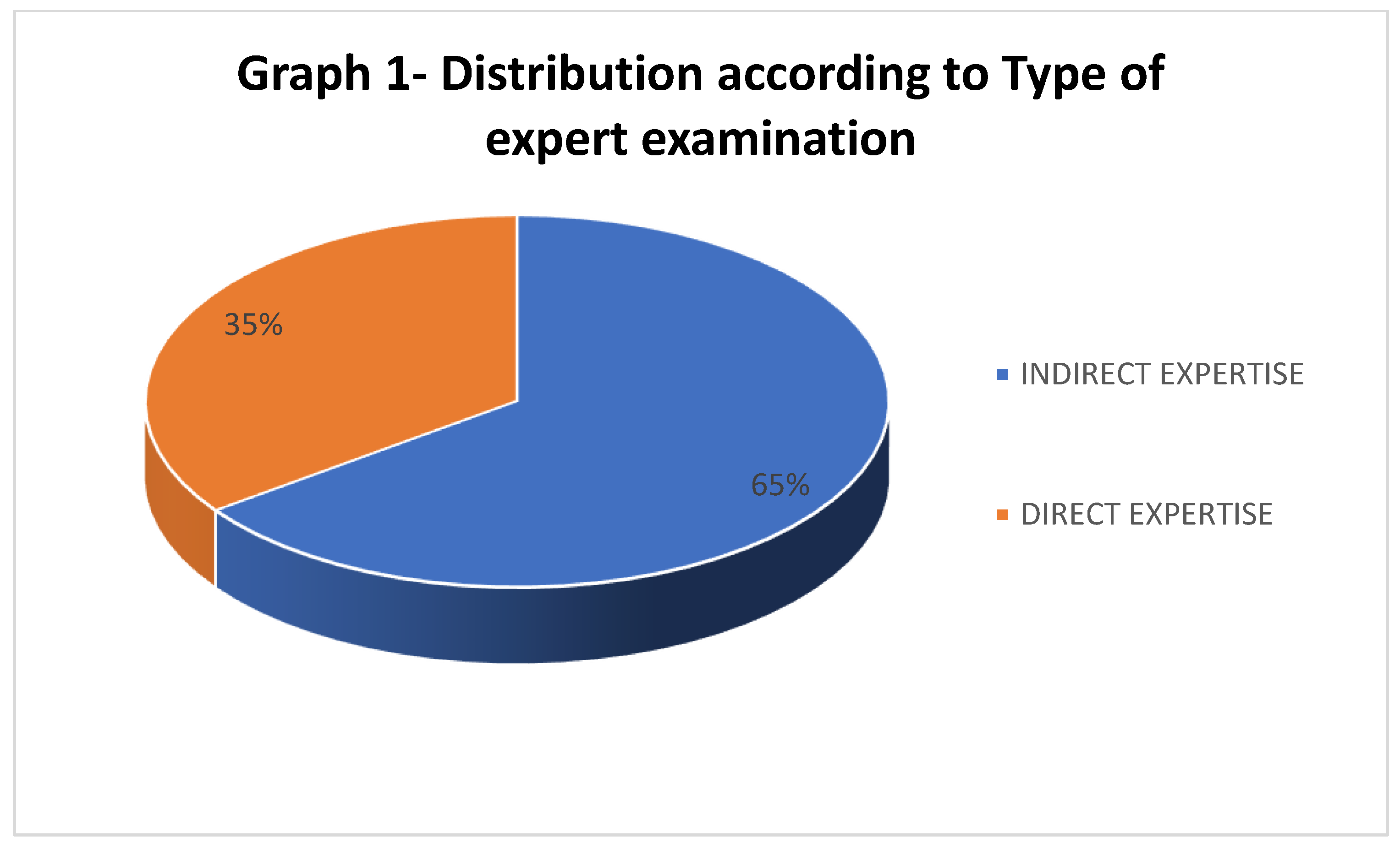

In 27 expert examinations (45%), the expert conclusion determined a causal link between medical care provision and the damage caused (

Graph 2).

Of the 27 reports with causal link, in one case the judge was not in accordance with the expert’s report, thus not considering it as a medical error. In the other 26 expert examinations with causal link, the judge agreed or partially agreed with the initial claim, and went on to classify the type of medical error. The judge classified all 26 as negligence and in 7 of them, he added recklessness.

Graph 3 shows the classification of type of medical error.

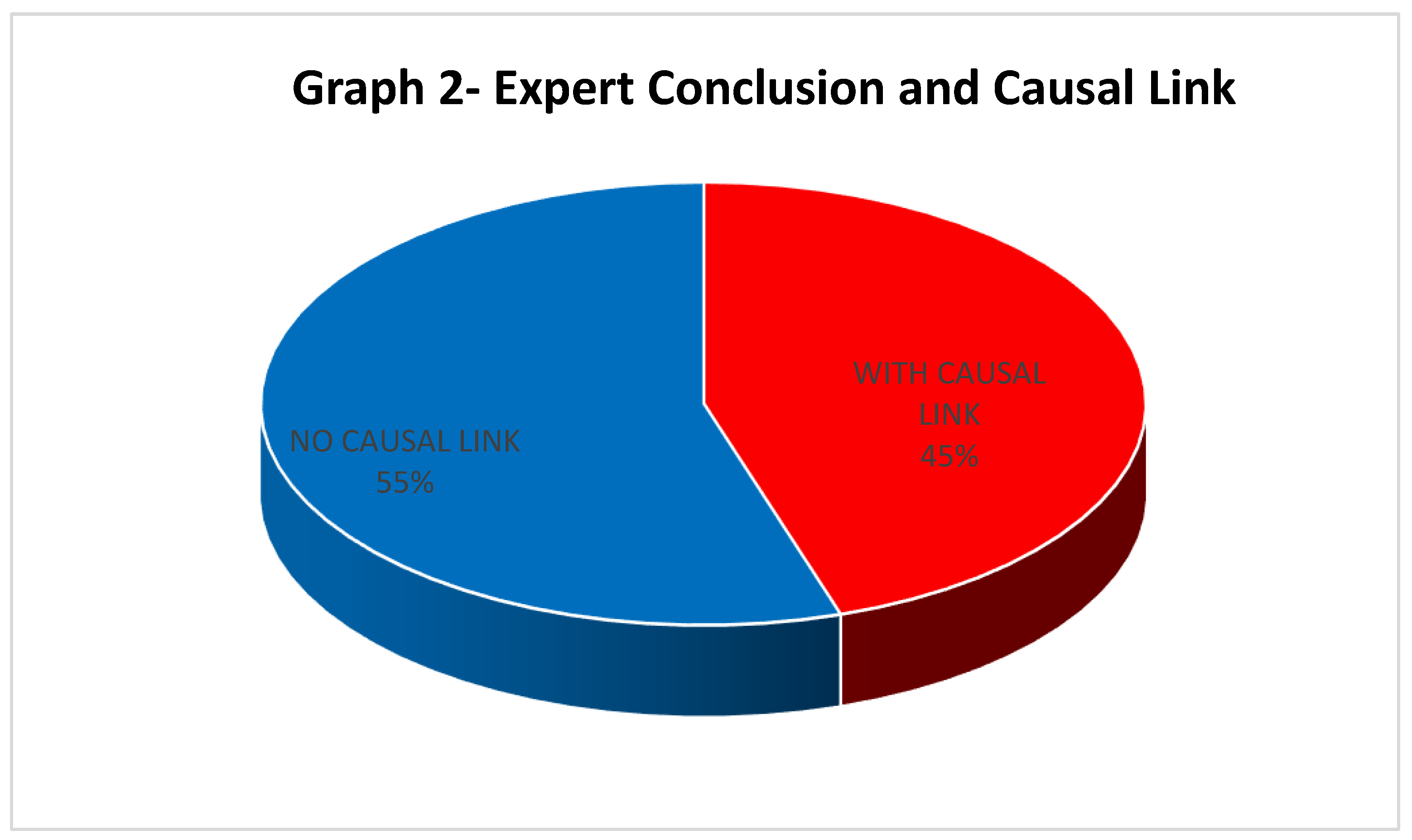

Half of the lawsuits (30) were considered unfounded, 22 (36.6%) were considered partially founded, 7 (11.6%) were considered well-founded, and one (1.8%) was time-barred (

Graph 4). In the statute of limitations, the judge only ruled on the merits of the time between the event and the start of the action, regardless of the expert report.

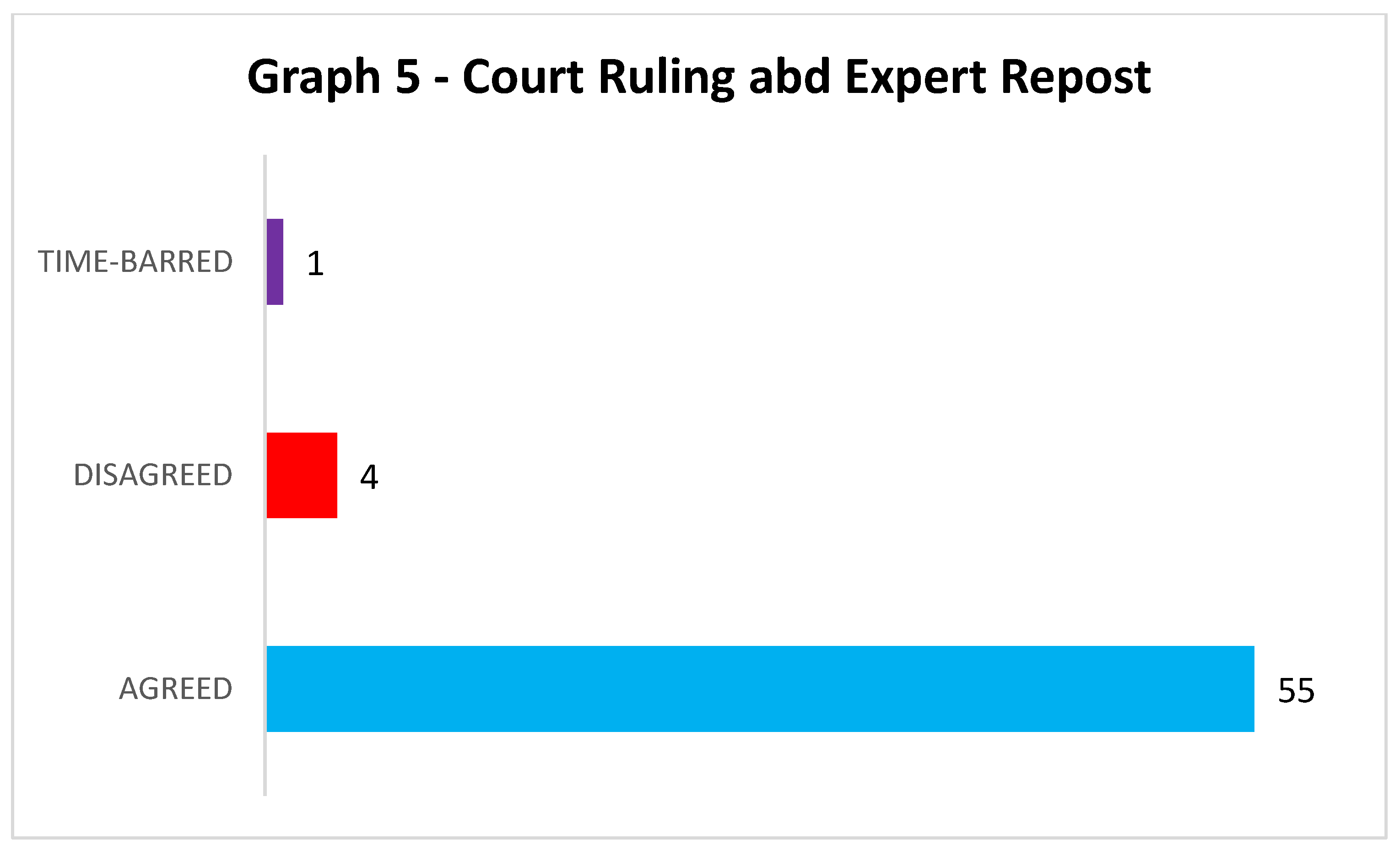

Most sentences (55) were in accordance with the expert’s conclusion (91.6%). Only four (6.6%) were in discordance, and one (1.8%) was time-barred (

Graph 5).

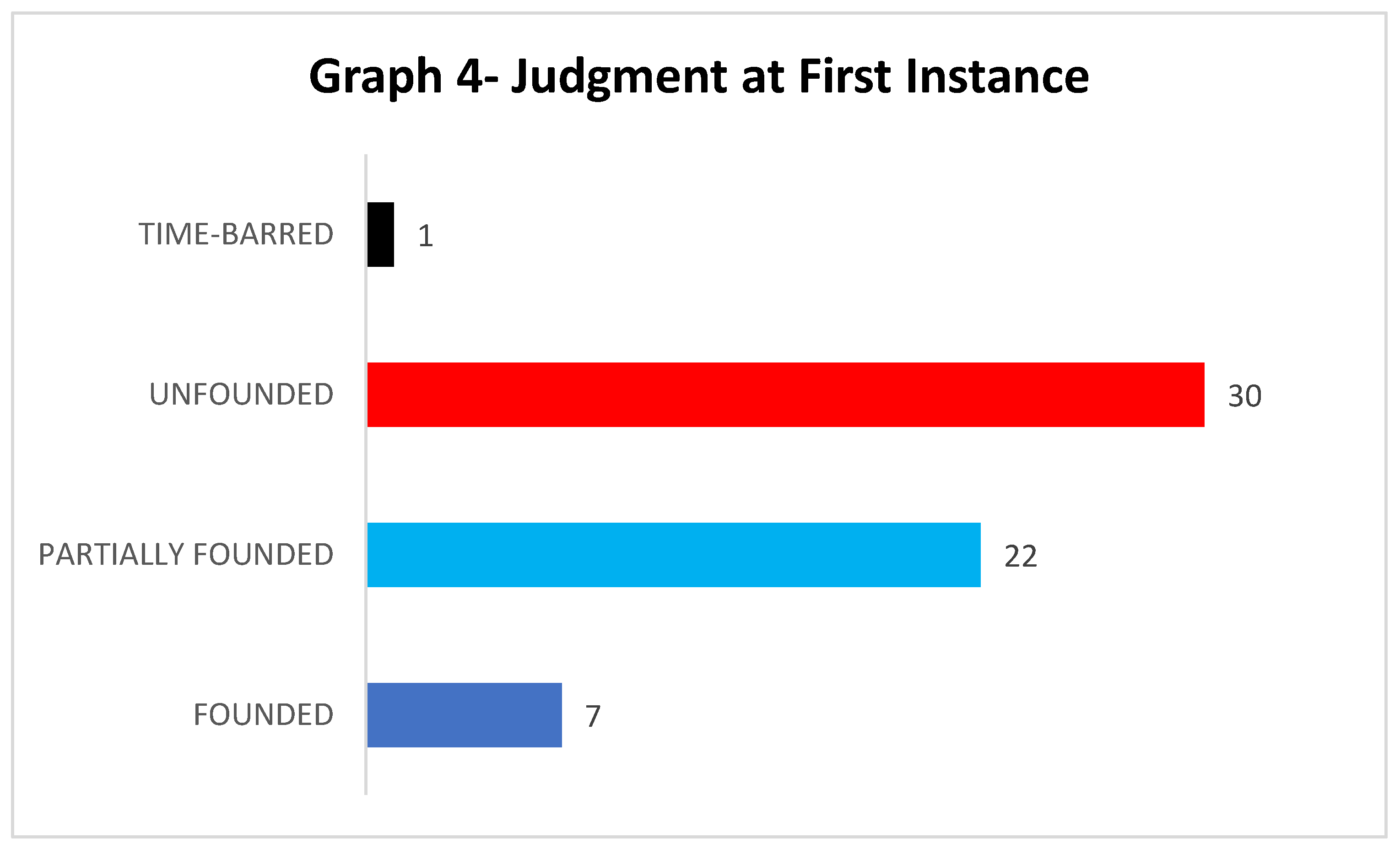

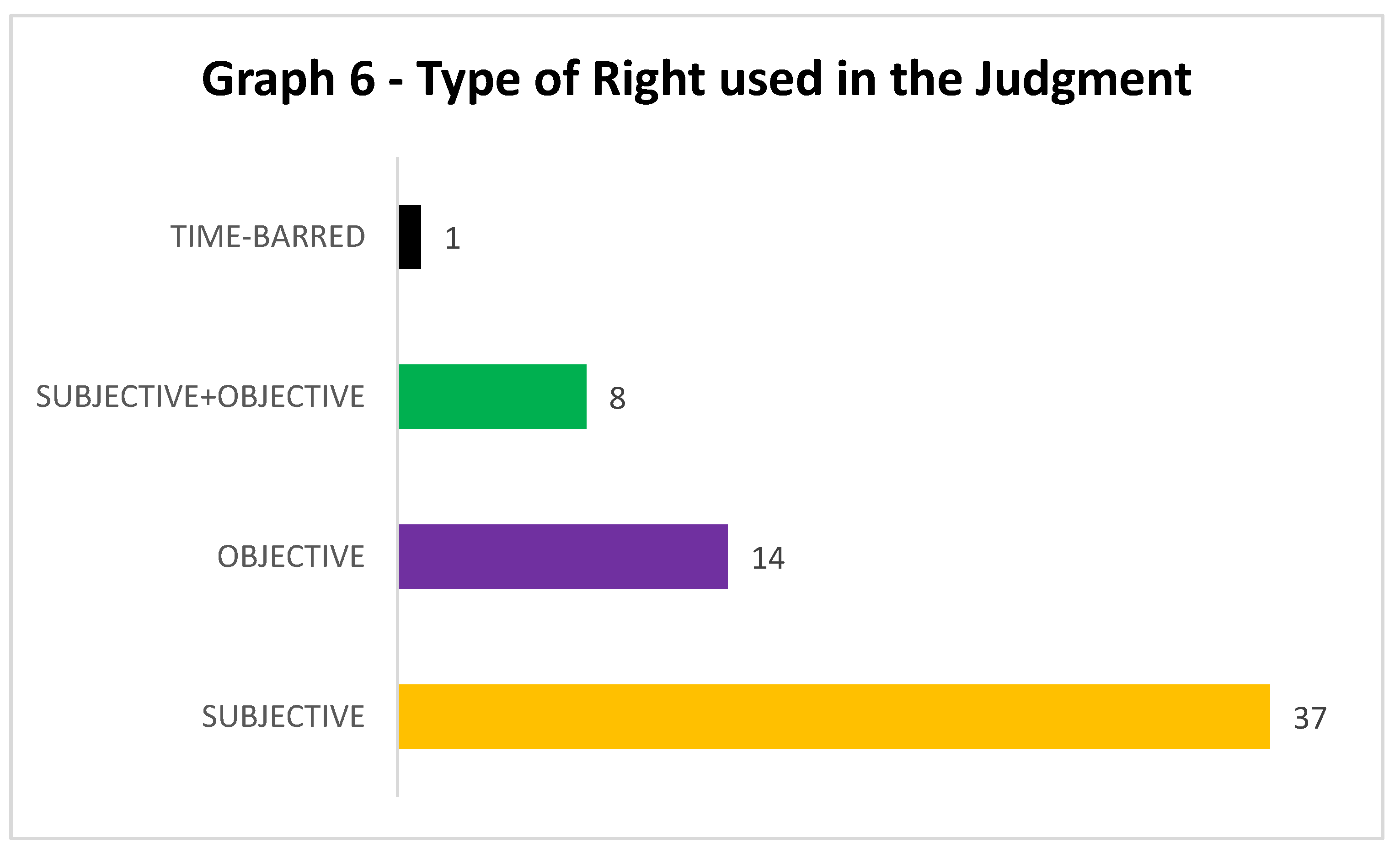

Subjective right was the mostly used by the judge as grounds of the sentences. It was used in 37 rulings (61.70%), followed by objective right, used in 14 judgments (23.30%). And both, subjective and objective rights were used together in eight judgments (13.30%). Time-barred occurred in one case only (

Graph 6).

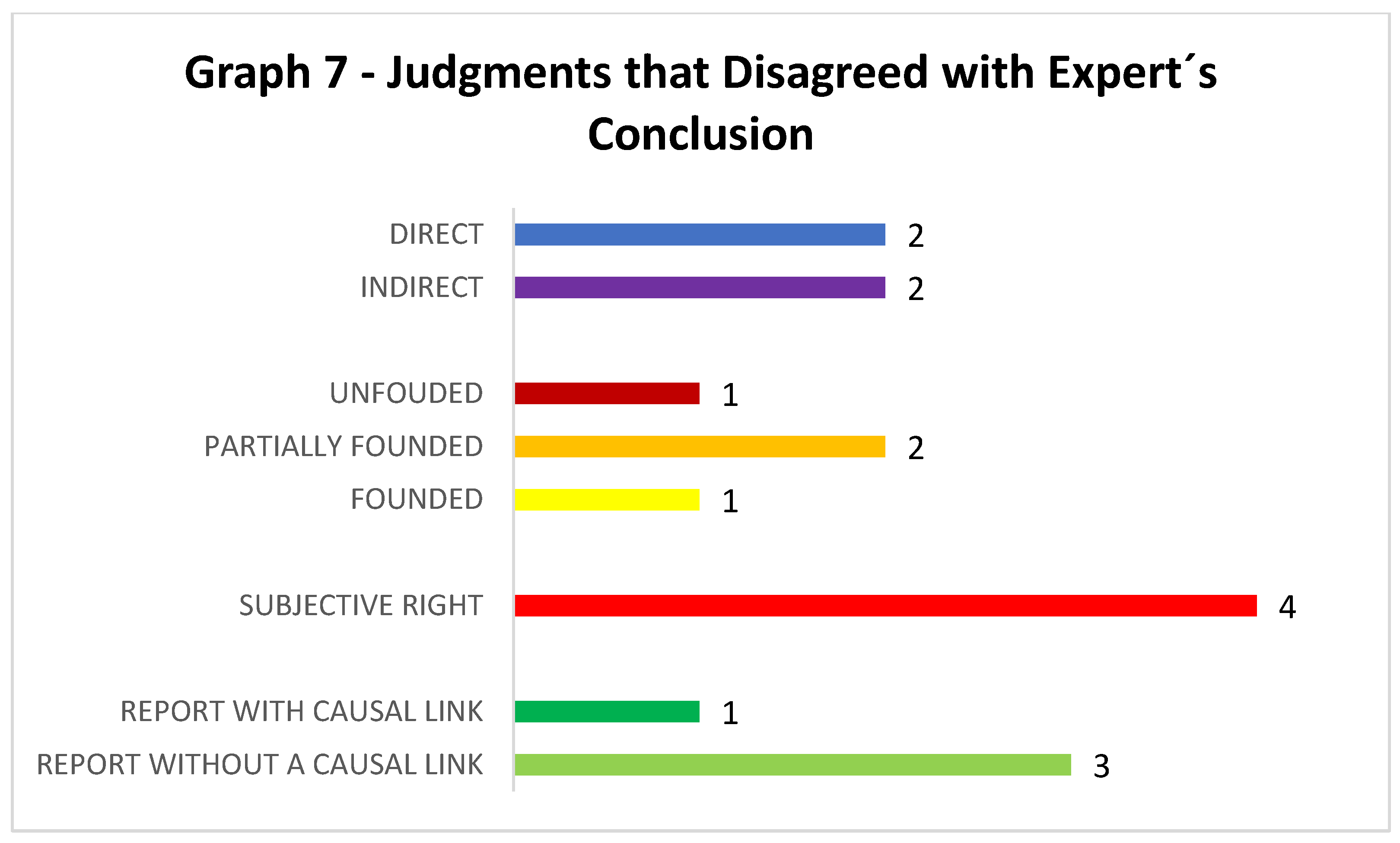

When we analyzed the judgments that disagreed with the expert’s conclusion (total of four), we found that most of them had the expert report finding no causal link to medical errors (three cases). The subjective right was used in all sentences. The judgement was well-founded in one case, partially founded in two cases and unfounded in one case (

Graph 7).

When analyzing the judgments that agreed with the expert’s conclusion (55 cases), 53% of the reports did not determine a causal link (29 cases), thus showing no irregularities. These cases were considered unfounded.

All lawsuits (100%) claimed moral damages. In 41 cases, material damage was also claimed. And in three only, compensation for aesthetic damage was added.

The loss of a chance was put forward by the magistrate in three partially well-founded sentences and in one well-founded sentence. In these four cases of loss of a chance, the verdicts were in agreement with the expert’s report which determined a causal link.

In the statistical analysis of the distribution of nominal variables (frequency), we found strong agreement (kappa = 0.86) between the expert medical report and the court judgment, with statistical significance. Most sentences were in line with the expert conclusion (91.6%) and this frequency was statistically significant.

In the statistical analysis of the distribution of the nominal variables (frequency), we found weak agreement (kappa= 0.10) between the causal link and the type of expert examination (direct/indirect), indicating that the fact of death is independent in determining the causal nexus.

No statistically significant association was found between the type of right (subjective and objective) and the compatibility between the court ruling and the expert report (Fisher, p=0.483).

5. Discussion

Throughout the world, the occurrence of medical malpractice, popularly known as “medical error” has become a fact of life both in the media and in the courts of various countries. The concept of medical negligence is unanimous as the act carried out by a medical or healthcare professional that causes harm to the patient. The search for compensation for damage has provided courts and lawyers with an area of practice that combines medical and legal knowledge, crucial for an effective judgment.

Over the last two centuries, the discipline of medical jurisprudence, where medical knowledge is applied to respond legal issues has expanded to such an extent that a new field was created, the field of forensic medicine, closely uniting law, and healthcare. In the past, the two professions were seen as the association of great knowledge to the practice of justice. In these past 200 years, there have been major changes as how to enforce the law with regards to medicine, including assessing the medical act and its possible flaws [

3].

The first medical malpractice case in England was held in 1767: Slater v. Baker [

3]. Slater broke his leg, which failed to heal properly. So, he sought treatment from another doctor, a surgeon named Baker. Dr. Baker re-fracture his leg and utilized a steel contraption to stretch Slater’s leg, which led to further injury. Slater sued Baker; three surgeons testified that the “steel thing” should not have been used. The jury awarded Slater £500 (approximately £60,000 today), and the defendants appealed. The appeals court affirmed the award. In its decision, the English court determined that a radical experiment can be considered negligent, at least in the absence of the patient’s consent. In 1840 the first medical malpractice case was heard in the American courts.

Law and medicine have been closely associated since at least the last two centuries, but it was in 1964 that the New England Journal (NEJ) inaugurated a regular feature on the subject (then called “Medicolegal relations”) and William J. Curran started writing his “Law-Medicine Notes.” Like Elwell and Beck before him, Curran devoted several articles to medical malpractice (including hospital liability), forensic medicine (including abortion) and forensic psychiatry, yet he also tackled new topics including the physician and the shifting roles in capital punishment, torture, death care, foetal research, and the issue of determining death by brain criteria [

3].

In Brazil, lawsuits involving medical error have increased by 200% in the last six years - most of them related to childbirth care and plastic surgery [

4].

In 91.6% of the sample, statistical significance was found between the expert report and the court ruling (p<0.005), demonstrating the influence of medical expert evidence on the decision of the judge.

Observations show that medical malpractice lawsuits are lengthy and take about 4.7 years until the publication of a judgment at first instance. Despite the growing number of medical malpractice lawsuits, in most cases (55%), expert analysis did not determine a causal link. This finding is also verified in the study by Talita Rodrigues Gomes and Maria Célia Delduque, where most lawsuits analysed were rejected (57%), demonstrating the difficulty in proving the adverse event as consequence of a wrongful act [

5]. Only 11.6% of the lawsuits analysed, had the final decision considered founded in favour of the plaintiff. Of the total actions analysed, 36.6% were considered partially founded, granting the plaintiff part of what was claimed in the initial lawsuit. One action was time-barred.

Most expert examinations were carried out indirectly (65%), indicating a high number of deaths in our sample. In the year 2000, the Institute of Medicine IOM published the report “To Err is Human - Building a Safer Health System” stating that medical errors cause between 44,000 and 98,000 deaths a year, making it the 8th leading cause of death in the United States, surpassing traffic accidents (44,458), breast cancer (42,297) or Aids (16,516) [

6]. Fragata and Martins estimated that deaths due to medical error in Portugal account for between 1,300 and 2,900 per year, consecutively surpassing deaths per year from traffic accident from 2005 until September 2011 [

7].

We found four cases (6.6%) of disagreement between the expert report and the court judgment. In these cases, we observe the principle of motivated judgment which allows the judge not be bound by the report issued by the expert as long as there are sufficient grounds for the decision.

One of the cases draws attention because the legal basis does not value medical records as evidence. The medical expert did not prove a causal link in the child who had neurological sequela due to Kernicterus. The judge accepted the testimonial evidence and claim that the medical records were one-sided and of dubious value. In this case there was no evidence of haste, carelessness, lack of knowledge about how to fill in the medical records, as well as other circumstances that might contribute to the misuse of medical records.

It is worth noting that the Federal Council of Medicine’s resolution 1,638 of 10 July 2002 stipulates that medical records must include “anamnesis, physical examination, complementary tests and their respective results, diagnostic hypotheses, definitive diagnosis and the treatment carry out”; int this case the medical record followed the rules of the Federal Council (CFM, in the Brazilian acronym).

In the other two conflicting cases between the expert report and the court judgment, the expert report did not determine a causal link and the judge considered one case as well-founded and the other one as partially founded. In one case it was alleged that the obstetric procedures had not been explained to the patient, and in the other that tests should have been carried out to avoid possible side effects from metoclopramide medication.

In the last case which disagreed between the expert report and the court judgment, the medical expert determined a causal link in the child’s first treatment, which was not re-evaluated before discharge. The child died on the same day on returning to the same medical care service, however, this last care follows the parameters of good medical doctrine. There was no technical opinion from the plaintiff to highlight possible flaws in the care. Thus, the judge focussed on the part of the expert’s report on the last medical care and did not consider medical error.

The

loss of a chance was also seen in the sentences analysed, being present in four cases with a causal link and an agreed sentence. This is the case in many countries. In the US jurisprudence (De Burkarte v. Louvar), the court admitted the theory of loss of a chance to hold the doctor responsible for not requesting a biopsy to detect the patient’s cancer, which had progressed, due to opportunistic damages caused by the disease itself, aggravated by a late diagnosis [

6]. In Italy, compensation is allowed for “loss of chances of survival or protection.” GIOVANNA VISINTINI [

8] warns that it is appropriate in contractual liability.

In judgments considered founded or partially founded, we find that when the error of the doctor is proven, whose liability is subjective under the terms of article 14 of the Consumer Defense Code, the liabilities automatically extended to the hospital and the medical insurance company. The Brazilian Supreme Court has already ruled that in the event of medical error, the fault of the person directly causing the damage must be proven for liability to extend to the hospital. It should be emphasized that for joint and several liability to be applicable between the doctor and the healthcare institution there must be an institutional link. In cases where the doctor had no connection with the hospital and uses it for the examinations or surgeries, the hospital liability only applies when the damage results from the failure of services that are the sole and exclusive responsibility of the healthcare institution [

9,

10].

In our study, the subjective right predominated in most lawsuits (55%). The objective right was applied in 13 lawsuits against public hospitals, of which three applied objective right in regards to the hospital and subjective right for the doctor; despite the understanding of the supreme court of Brazil, which has jurisprudence of subjective right for lawsuits against public hospitals. The judges’ justification in these cases lies in the theory of administrative risk. In private hospitals, objective right was applied in six cases.

All lawsuits claimed moral damages. Moral damages were awarded to the well-founded and partially founded lawsuits.

6. Conclusions

The court-appointed medical expert needs extensive knowledge of the various areas of medicine and most correlate the medical act with legal thinking on the facets of civil liability. It is not up to the medical expert to make a value judgment, but to provide the judge with the elements needed to be convinced by other evidence in the case.

Expert evidence substantiated 91.6% of the court rulings and was considered to be highly valuable evidence by the judge. The conclusion is that expert evidence has a major impact on the judicial process and is statistically significant (p<0,005).

There is a consensus in the legal field on the type of civil liability of doctors and healthcare companies. The former falls under subjective law, requiring fault; the later under objective law, requiring only damage and causal link. The main defendants in the lawsuits were hospitals and not medical insurance companies, present in 100% of the cases analysed. In 28% of the cases, the doctor was jointly and severely liable with the legal health entity. Subjective law was applied to analyse medical error in all cases where healthcare professionals were involved. Objective law was applied to analyse medical error in all cases where there was a consumer relationship between the patient and the hospital or medical insurance company.

Moral damage was claimed in all lawsuits and then was covered in 100% of those judged to be well founded or partially well founded.

The main reason that led the claimant to seek justice was the final event of death, present in 65% of the cases.

The median time between case distribution and the judgment was 4.7 years. We concluded that the publication of a judgment at first instance is time-consuming. This is due to the complex nature of the lawsuit, requiring medical expertise for technical support, the requisition of medical records, witness statements, and technical opinions from the parties involved, which means that the judge has to analyse a range of evidence in order to be convinced.

Observations

The authors declare no conflict of interest. This article is based on the author’s doctoral thesis conducted at the Department of Pediatrics of University of São Paulo Medical School. It was approved by the Ethics and Research Committee and registered on Platforma Brasil under CAAE number 35085220.2.0000.0068 and under Ethics Committee opinion number 4.534.302.

References

- Lourenço EA. Erro médico, falha médica e iatrogenia. See Perspect Méd. 1998; 9: 16-21.

- Wild CLDT. Erro médico – o laudo pericial e a decisão judicial. Saúde, Ética & Justiça. 2014;19(1): 21-25. [CrossRef]

- Annas GJ. Doctors, Patients, and Lawyers -Two Centuries of Health Law. N Engl J Med 2012; 367: 445-50.

- Murr LP. A Inversão do onus da prova na caracterização do erro médico pela legislação brasileira. Bioética Magazine, 2010;18(1): 31-47.

- Gomes TR, Delduque MC. O Erro médico sob o olhar do Judiciário: uma investigação no Tribunal de Justiça do Distrito Federal e Territórios. Cad. Ibero-Amer. Dir. Sanit., Brasília, 6(1): 72-85, Jan./Mar, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Kohn LT, Corrigan JM. To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Institute of Medicine of National Academy Press. Washington, D.C. 1999.

- Oliveira JBDVM. O Erro Médico nas Instituições Públicas de Saúde. Dissertação de Mestrado. Porto 2013. http://hdl.handle.net/10400.14/16792.

- Carvalho, DP. Os novos contornos do dano: o dano decorrente da perda de uma chance. In: Âmbito Jurídico, Rio Grande, XIV, n. 95, Dec, 2011. Available at <http://ambitojuridico.com.br/site/index.php/Ricardo%20Antonio?n_link=revista_artigos_leitura&artigo_id=10771&revista_caderno=7>.

- Resp no 1635560/SP (2016/0254982-3).

- Minossi JG. Prevenção de conflitos médico-legais no exercício da medicina. Rev. Col. Bras. Cir. 2009; 36(1): 090-095 autuado em 21/09/2016. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).