1. Introduction

According to a created by SAC The Higg Index, wool is calculated to possess one of the highest environmental impacts among all textile fibres. In general, it is ranked a total score of 80,6 MSI (Materials Sustainability Index), higher than cotton: 54.49 MSI and even higher than polyester: 36,2 MSI or polyamide: 29.67 MSI [1].

To put a better light on the evaluating institution, founded in 2010 the SAC- Sustainable Apparel Coalition is a cooperative of brands, retailers and manufacturers that are likely to be responsible for more than one third of the clothing and footwear produced globally. The Higg Index is an esteemed assessment tool created by SAC to support apparel and footwear products in its green goals [2]. Constructed on trusted life cycle assessment data that is supported by science, the Higg MSI calculates environmental impacts and “translates them into comparable Higg MSI scores” [1,45]. It is a gear with evaluation of a product’s sustainability effects, estimating raw materials, manufacturing processes and end of life. The tool collects information on energy, water and chemical consumption by the industry within product lifecycle. Its main aim is to allow professionals to make pro environmental choices and to improve design and production of garments [3]. These evaluations come from data collected from SAC members, receiving this way a standardized score presented in The Higg Index schemes [4]. As it had been written before, The Higg Index provides homogenous calculations of wool environmental impacts also. These ones include definite filters as global warming, eutrophication, water scarcity, resource depletion, fossil fuels and chemistry, what shall be used further on in this analysis.

Although the Higg Index is acclaimed and practiced by fashion business [4–8] one might question the above source of information about wool environmental impact as single, and not sufficient. There is also a critical voice as the report by KPMG, conducted in 2023 [9], concluding that the Sustainable Apparel Coalition's (SAC) Higg Materials Sustainability Index (MSI) could be disposed to misinterpretation when used in isolation. The report claims, that although the Higg Sustainability Index has been utilized for over a decade, it is likewise exposed to controversial opinions as favouring fossil fuel-based synthetic materials over natural textiles- such doubts shall be addressed in the further parts of the text. Hence, it is recommended to call to additional credible sources, like academic papers and scientific research, that back on another judgement of a commodity or a service environmental performance: LCA- Life Cycle Assessment.

LCA is a complex products’ engineering calculation. It is a praised methodology for discerning collection of the item’s eco track, [10–12], that includes measurement of individual production phases in the context of impact on the ecosystem. During the life cycle assessment of the examined entity by LCA, its overall impact on the environment is valorised, containing primary natural resources usage and environment contamination on the earliest manufacture phases, the side eco footprints as ecological footprint of distribution, the usage, waste and contamination of water, the usage of energy and any pollution during all production stages. It even calculates consumer use part impact on the ecosystem. This scheming also includes influences of manufacture of necessary semi-finished products and preceding processes: supplier assessment and environmental exploitation, once again- correspondingly at the early stage of production. Finally, LCA weighs waste management related to the production of a given item and its decomposing capacity [2]. These exclusive features of LCA help avoiding problem fluctuating from one life cycle stage to another phase, or from one environmental impact to another impact [13]. Following Dahllöf and Płonka [14,26], LCA is credible and makes a competent measurement tool of a product’s life cycle.

That is why LCA has been chosen to be used in the below analysis for better understanding and sourcing data about wool environmental impacts, what is further followed by equation with information promoted in the Internet by wool industry itself.

2. Wool via LCA Lenses

While the wool industry tries to find its way of narration through internet communication channels, according to latest research, the LCA of wool presents a concerning high environmental impact. Although LCA revisions depend on taken variables and measured case studies (strategies for manufacture, production location, distribution destinations and due to that different transport distances, where even supply chain activities may account for up to 90% of the environmental impact of product [10], the accessible results bring concerning numbers and clearly critical perspectives on wool LCA. Co2 emissions analysis, climate change, energy and water consumption are crucial for fibre environmental footprint [15]. One kilogram of unprocessed, or "greasy" wool from meat lamb is equal to 8.9kg of CO2e, whereas one kilogram of greasy merino wool from a sheep who is alive and regularly trimmed for a longer period is equal to 30.6kg of CO2e.1 [16]. The impact on climate change of one woollen undershirt outcomes in 11.7 kg CO2 eq, mainly due to the farming phase of sheep (grazing), which accounts for 88% of the over-all of emissions. What is more, 1kg of wool Co2 emissions range due to their length, from 25 to 30 kg CO2 eq/kg- short fibres impact to 78–97 kg CO2 eq/kg- longer fibres [17,43]. This could be compared to data brought by Devaux [18], stating that wool GHG average outcomes are 56 kg/ 1 kg of yarn. Wiedemann, Simmons, Watson and Biggs [19] LCA studies bring measurements on predictable impacts of wool production of 15.75 kg CO2-e for 500 g of clean wool. However, the LCA in terms of global warming wool contribution is much higher while including a proportion of sheep maintenance requirements- then GHG emissions calculations elevate from 10–12 kg CO2-e/ per 1 kg of wool to 24–38 kg CO2-e/kg wool [20]. Such results are similar to Brock [21], whose research finds the total greenhouse gas emissions amount 24.9 kg CO2e/ per 1 kg of wool, however a different study from a cradle-to-gate perspective shows even higher results, where wool yarn production results in 95.70 kg CO2 eq/kg for climate change/global warming potential [21]. Although the above presented numbers may diverge according to assumed variables, they give a perspective on wool high impact in context of climate change trough GHG emissions. As it is pictured in Shear Destruction Report [16] small cattle farming, including sheep and goats, each year is responsible for CO2 emissions 5 times higher than the number of cars registered in Australia itself.

In terms of energy LCA evaluations, Devaux [18] brings calculations of wool energy input with a score of 32 (MJ). Other described results for the impact category of energy use for the on-farm period of production for New Zealand merino wool are 13.42 MJ per kg greasy wool or 22.55 MJ per kg wool fibre [23]. Again here the variables shape the outcomes, where the wool LCA is very high in phases of processing, like cleaning and fibre improvement. The same factors influence the LCA outcome depending on even type of farm. Energy use in intensive farm systems is reported to be 21% higher than for extensive farms. However, the total energy on-farm part through to a spinning mill in China (the most common global production destiny) is estimated to be 45.73 MJ/kg [23]. Other numbers on energy use or correlated energy consuming phases present as following: in case of Diesel energy usage 0.00021 kg/ 1 kg of wool, liquid petroleum gas 0.00051 kg/ 1 kg of wool, electricity—high voltage 0.209 kWh/ 1 kg wool, energy from natural gas 6.266 MJ/ 1kg, process steam from light fuel oil 0.013 MJ / 1 kg, fossil energy requirements for the production of an additional 500 g of clean fine Merino wool: 36.15 and 13.13 MJ respectively, and that the energy requirements for the production of 500 g of clean wool assessed by LCA: 19.32 MJ [19].

In the field of water use, wool LCA outcomes state that it is needed 17.843 l to produce 1 kg of wool [19], where according to the author’s inventory for the scouring and combing of 1 kg of wool, water lost due to evaporation consumes 2.399 l, while scouring wastewater treatment itself takes 15.444 l. Even when calculating water loss in wool production, the fresh water consumption by animals shall be calculated, as Devaux [18] sums ups its total ranging between 204 to 394 L/kg in case of greasy wool.

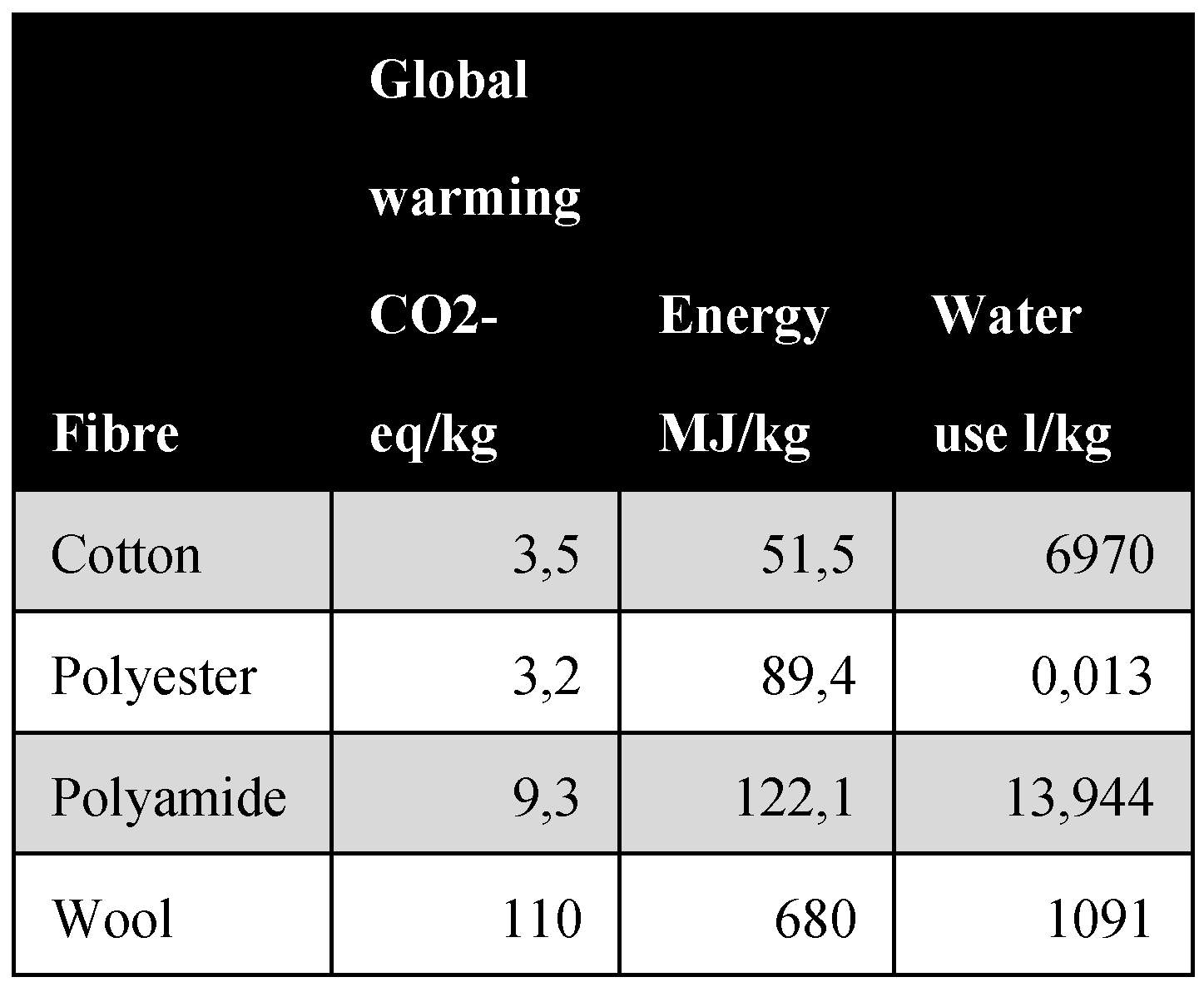

Nevertheless, to present the above complex data in a better way, there has been cited a juxtaposition with other popular materials from the Sustainability Impact Metrics ranking [24].

Figure 1.

Sustainability Impact Metrics ranking (cited from Grevinga [24].

Figure 1.

Sustainability Impact Metrics ranking (cited from Grevinga [24].

As illustrated, wool cannot be classified as a sustainable fibre considering it literally ‘beats’ other most popular materials in environmental negative evaluations, both in context of global warming/ Co2 emissions during its whole life cycle (35 times more than polyester or cotton and 11 times more than polyamide), likewise in energy consumption (13 times more than cotton, 7 times more than polyester and 5 times more than polyamide). Equally in water usage the calculations are merciless (83 923 times higher usage than polyester), although cotton and polyamide present a contradictory ranking outcome here, having a much higher footprint in water usage than wool or polyester.

Recapitulating, despite its natural origin, wool's resource-intensive production process make it less environmentally friendly compared to other popular materials, as presented above.

3. Greenwashing Framework

Apart from the above revealed data that jeopardizes wool green image, the wool market cultivates sustainable narration about its products. There might be noticed a pattern: commonly adapted phrases and ascriptions about wool sustainability, including: ‘natural’ and ‘biodegradable’ words. There is also another eco aspiring practice wool business follows, which is a method of making selective comparisons of particular negative features of other materials in order to put wool in a better light. There is a noticeable abusive usage of these terms and undeserved wool placement in context of sustainability, what could be classified as greenwashing practices.

Although sustainability is often seen only as an aspect of marketing strategy [25] it would be unreasonable to underestimate the meaning of marketing as one of sustainable performance elements, considering its supremacy to spread information and to shape consumers tastes. However, commonly such practice is grasped as another type of building the hyper-sales-based world through pro-ethical and pro- environmental messages, thus manipulating the customers and other stakeholders, as from its fundamental concept, marketing is not to be objective or to run straight public speech in ethical or ecological themes, cultivating nothing but greenwashing [26].

According to a systematic review by de Freitas Netto, Sobral, Ribeiro and Soares [27] greenwashing is defined as:

“(…) the phenomenon as two main behaviors simultaneously: retain the disclosure of negative information related to the company’s environmental performance and expose positive information regarding its environmental performance”.

(p.6)

What is more, referring to Seele and Gatti [47], greenwashing arises in the light of rational correctness, where “Cognitive legitimacy is based on the shared taken-forgranted assumptions of an organization’s societal environment.” As Newbery and Ghosh-Curling [28] have found, it is about a cultivation of the company’s green image, with the rhetoric far outweighing the real company’s accomplishments. Walker and Wan [29] write, there are different organizations, some that run a “green talk” to polish their corporate image (greenwashing), and some whose green dialog (symbolic activities) is joined with “green walk” (substantive actions).

Overall, greenwashing is not exactly about claiming the untruth. Nevertheless it is a selective beneficial communication, hiding meaningful, but negative facts and making a contextual enhancing of extracted features to a level that changes the subject’s perceptions. It is a commercial ‘beauty lifting’ via green values, an arrogation to sustainable goals and pro environmental achievements far beyond facts or happenings.

4. Case Study

The below case study provides an interpretation of greenwashing practices by wool industry, based on the first positioned links in Google, while searching the internet with phrase as “sustainable wool” or “is wool sustainable”. Woolmark, an organization representing 60,000 Australian wool growers, has been selected, as it appears as the very first in Google while using the above key words. Woolmark [36] claims on its site to be the world’s most known textile fibre brand - with its emblem applied to more than 5 billion products since 1964, an organization that represents a commitment between woolgrowers, brands and consumers on the authenticity and quality. Its main activity is dedicated to certification and networking in wool business. Due to that, the brands’ recognition and its google positioning were the main reasons for its selection. It has been followed by comparison to other highly ranked links of wool and fashion industry representatives, likewise extracted from the first page in Google search (January 2024): IWTO (International Wool Textile Organisation) [30], AWI (Australian Wool Innovation) [31], CFDA (Council of Fashion Designers of America) [32], American Wool [33], Trust in Australian Wool [34] or British Wool [35].

The Woolmark website welcomes with a sentence: “Wool has long been accepted as an environmentally positive fibre choice with a number of benefits, such as being 100% natural, renewable, biodegradable and recyclable” [36]. As it can be mapped on other, cited in this article, highly positioned in the Internet websites, multiple wool brands and organizations use similar phrases, what likewise was found by “Shear Destruction. Wool, Fashion and the Biodiversity Crisis report” [16]. The commonly used expressions are; ‘natural’, ‘biodegradable’, mixed with selective comparisons to other materials (mostly synthetics) through picked up features, hence in comparison to presented wool LCA numbers, the earlier makes an entry to a study of such claims.

4.1. ‘Natural’ Is Not an Eco- Guarantee

Asking whether wool is natural would be rhetoric. However, it could be also inquired if the adjective ‘natural’ ascribed to any product, being or happening inevitably gathers all the beautiful symbolic attributions to the healthy and idealistic ecosystem, almost like from Henri Rousseau paintings or Jane Austen romantic portrayals. What is firstly analysed in this paper are greenwashing techniques via abusive expression of ‘natural’, numerous times placed in sustainability brackets by wool industry. As it is briefly summed up in The Guardian:

“Natural's not in it: just because a product calls itself 'natural' doesn't make it good. Not only are hurricanes, disease and mosquitoes natural, the way the word is defined by regulators can render it practically meaningless”.

[37]

Referring to Collins Dictionary, Cambridge Dictionary or Oxford Dictionary “natural means natural things that are or happen in nature and are not made or caused by humans” [40–42]. What shall be emphasised, none of the definitions enlists ecology or ecosystem protection. There is no lexicon association of “natural’ adjective with sustainable features, eco products or sustainable practices in any dictionary classifications. However, it is reflected by a public, that a ‘sustainable fibre’ is an organic fibre or a natural one [15], although, according to US Department of Agriculture a product might be categorized ‘natural’, even it contains growth hormones [37]. Still, the term ‘natural’ is caught by different sectors of economy in sustainability setting and used to shift the perceptions of a product towards environmentally affirmative ones.

„In February 2021 The Fashion Law reported on the European Commission’s findings that 42% of companies making green claims were "exaggerated, false or deceptive" in their nature. According to the report, the UK’s Competition and Markets Authority and International Consumer Protection Enforcement Network’s assessment of companies making unclear claims, found regular mention of "natural products" and the hiding or omission of certain information that would disrupt eco-friendly appearances”

[16]

Wool business is not an exception here, as the vocal ‘natural’ is inflected by different declinations in context of high sustainability on wool associated websites. Practicing phrase ‘natural’ in close association to ‘sustainable’ correlated meanings and frameworks can be found on the first displays of wool industry via Google search. The examples start with Woolmark brand [36] where it might be read “(…) to adopt natural ingredients for a more sustainable future”, “100% natural, (…) wool is nature’s miracle fibre, offering a natural solution to the global apparel and footwear industry”, “Its natural benefits are so great that no other fibre - natural or man-made - can match it”. Such narration is being continued on American Wool website [33]: “(…) Natural Sustainability. The wool life cycle is as earth friendly as it gets.”, with “natural durability”, next on Trust in Australian Wool, a project partnered by Wool Producers Australia and Animal Health Australia to develop the Trust in Australian Wool campaign, to deliver information on sheep welfare and biosecurity practices, as well as the sustainability processes of the Australian wool industry. It states on its main entry webpage “(…) Aussie wool — a natural, sustainable product that is recognised globally for its excellence and quality” [34]. IWTO continues to paint wool’s green image via it biological nature: “Key facts about wool sustainability (…). Sheep are part of the natural carbon cycle (…)” and “The compelling sustainability benefits of wool include: Naturally renewable (…)”, “Wool is a naturally durable fibre. Wool garments can stay in circulation for a relatively long period of time, and this reduces their environmental footprint., “wool is part of the natural life cycle of the planet” IWTO [30]. Following Australian Wool Innovation, which stays in the same line with ‘natural’ being presented as sustainable “Australian wool is truly sustainable; it is 100% natural,(…)”, (…) position Australian woolgrowers as proactive, socially responsible and forward-looking stewards of the environment, building natural capital on their farms (…)” [31].

Making conclusions from a revision on the cited above green communicates, every one of them uses adjective ‘natural’ in a positive, pro environmental or pro health background. The tendency to replicate misleading interpretation of wool’s sustainability through correlations to its ‘naturality’ is a common, repetitive behaviour by items linked directly to the wool business. As it has been explained at the beginning of this article, language science does not put ‘sustainable’ with ‘natural’ on the same page., there is likewise no etymological association, neither certification that confirms that ‘natural’ is a synonym of ‘pro environmental’. Moreover, both presented the LCA measurements and The Higg Index calculations do not leave doubt about wool’s large environmental impact, which is even higher than its synthetic counterparts. Adjective “natural” is proceeded by this part of fashion industry to assemble green credits and to blend into trendy eco narration. Natural origin of this yarn does not change its environmental, complete negative evaluations, thus making custom positive usage of the adjective ‘natural’ in context of wool sustainability a greenwashing practice.

4.2. Greenwashing through Selective Comparisons

As it might be recognized on the Woolmark website and analogous ones, synthetics are targeted for selective comparison with wool, ignoring in the discourse man-made innovative and sustainable fibres or even in most cases other, natural ones (cotton, hemp or leather). It seems in the wool industry public discourse about its counterparts, there is no wider palette of other materials it could be equated to. The story telling is constructed towards either biodegradable fibres or non-biodegradable synthetics or headed for microplastics emissions. Here a continual moderation via concerns about the environment in relations to microplastics or critique of synthetics drives to an impression of positive for wool placement among the purposely chosen fibres.

As leading in such narration Woolmark brings on its website “No microplastics, unlike synthetics. Wool (…) does not contribute to microplastic pollution in our oceans or on our land.”, “Choosing natural fibres over synthetic fibres can make a huge difference in protecting our land, waterways and ocean against pollution” and “Fabrics which sound too good to be true, such as recycled polyester and recycled nylon, are generally just that. At the end of the day they are still synthetic fibres, which stay in landfill for hundreds of years and contribute to microplastic pollution.”, “And don’t be fooled by (…) recycled polyester or regenerated nylon – these are still synthetic fibres which shed microplastics” [36]. American Wool goes further on: “Wool is an incredibly complex natural fibre, providing many attributes that plastic fibres just can’t match.”, “Wool is sustainable. Wool is grown naturally (…). This is in direct contrast to synthetic fibres (…)”, “Wool is also more durable than synthetic fibres” [33]. IWTO claims on its webpage, “All synthetic clothing and materials, sooner or later, will become microplastics, a “time-delayed” pollution bomb”, “Wearing clothing made from wool and other natural fibres means less synthetic fibres are released into the world.” (IWTO) [30]. AWI follows such narration “Research funded by AWI has shown that machine-washable wool fibres as well as untreated wool fibres readily biodegrade in the marine environment, in contrast to synthetic fibres that do not.”, “Synthetic fibres show little or no biodegradation,”[31]. British Wool likewise makes such selective and intentionally located comparisons, writing that “Wool & synthetics – what’s the difference? Wool is an amazing natural fibre. (…) Using wool products benefits the planet in many ways” [35]. American Wool continues “Testing of various textiles in clothing show that wool has a natural UV protection factor of 30+ in more than 70% of cases—much higher than most synthetics and cotton” [33].

Described here pick up of certain material and its intentionally selected features, taken often out of context and without a wider picture creates a cunning exit door for manipulation. In such light wool looks as a sustainability hero, while meantime the total Life Cycle Assessment of wool matched with synthetics by the business is consequently avoided. Not surprisingly Curteza writes, as a result of such narration, consumers would discard man-made fibres due to perceptions that they damage the environment,

“(…) But some manmade or synthetic fibres can be more sustainable than natural ones as they do not use as many resources as the ‘natural fibres’”.

[15]

Far from a positive view on wool’s sustainability within such type of a very narrowed and discriminatory description, a more all-inclusive revision presents a different perspective on this yarn. When likened to other materials used in similar types of garments, the outcomes are in opposition to the interpretations pushed by wool industry. Collective Fashion Justice’s Circumfauna Initiative more holistic calculations estimate the climate cost of sheep’s wool to be 3 times larger than acrylic and 5 times bigger than a textile made from conventionally grown cotton. One Australian merino wool sweater is accountable for 27 times more greenhouse gas emissions than an Australian cotton one. What is more, as an example, Collective Fashion Justice’s Circumfauna Initiative has found that a single bale of Australian wool requires 44.04 hectares of land to be kept cleared for production. In comparison, only 0.12 hectares is kept cleared to produce a single Australian cotton bale [16].

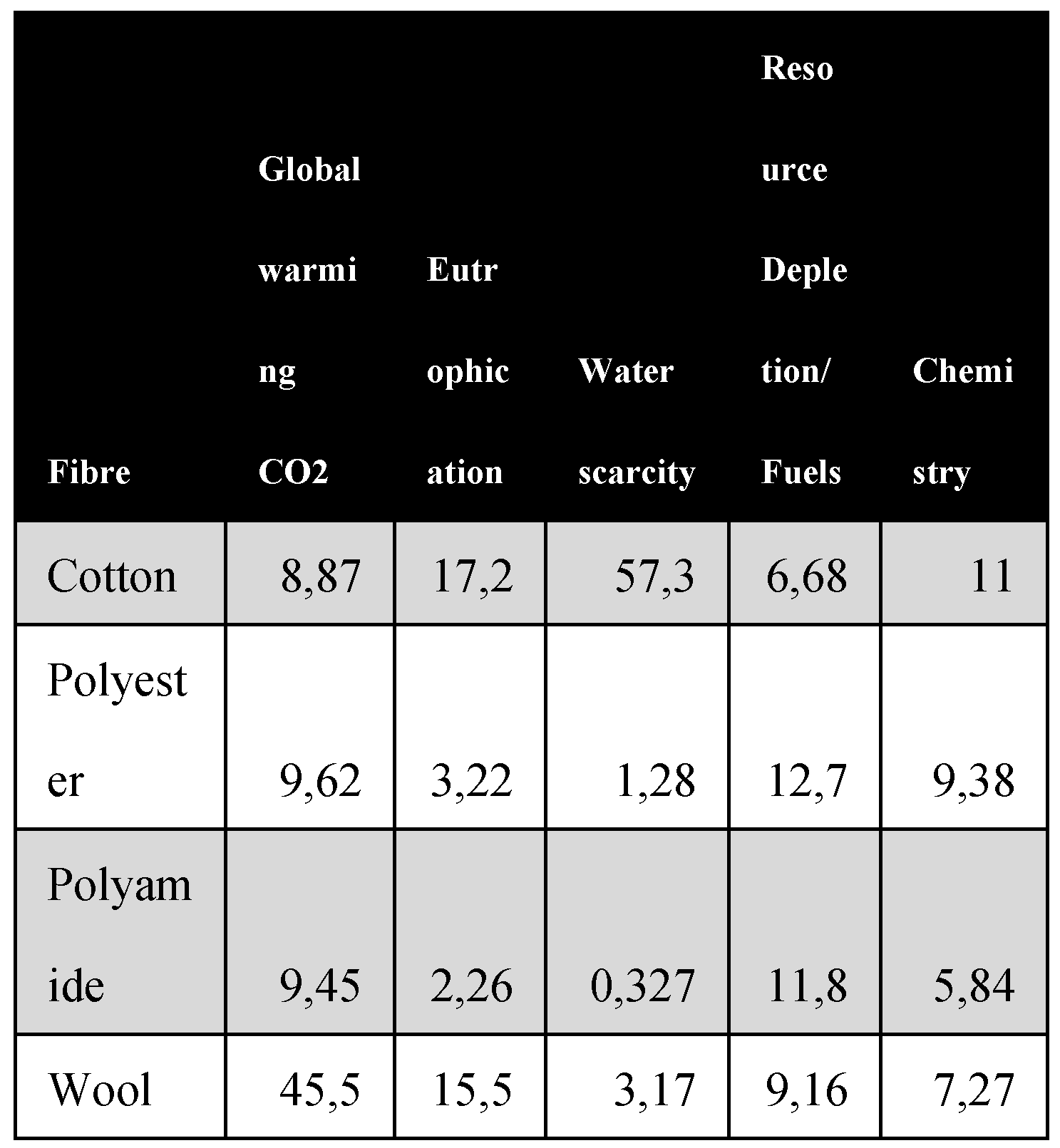

As it has been stated at the beginning of this article, wool industry is ignoring more complex studies in its communication. Not surprisingly, as neither the described earlier wool LCA academic data, nor The Higg Index MSI is favourable with this yarn, grading it with the highest- worst score. Therefore as another feedback for the below observations, detailed figures about wool MSI by The Higg Index have been presented in a chart. Wool has been placed in the graph next to cotton and synthetics (polyester and polyamide)- as these materials are repeatedly mentioned in selective comparisons in discussed wool manicured articles. The below table presents exact results of MSI of four compared materials in five areas: Global warming/ Co2 emissions, Eutrophication, Water Scarcity, Resource Depletion/ Fossil Fuels and Chemistry.

Figure 2.

MSI (Materials Sustainability Index) scores cited from The Higg Index [1].

Figure 2.

MSI (Materials Sustainability Index) scores cited from The Higg Index [1].

While analysing the above table, although it could be noticed that in terms of chemicals usage in wool production it is less poisonous to the planet than cotton or polyester, polyamide has got a better environmental outcome here than wool. In contrast, when the ratings of wool in the field of water scarcity are checked, cotton wears the worst burden to the ecosystem of all the compared materials. Wool is positioned on the second place here, having 9,6 times worse impact then polyamide and 2,4 than polyester in terms of water scarcity. Nevertheless, when looking at these materials via eutrophication, wool and cotton are even up to 6,5 times more damaging to the environment then the synthetic fibres. Yet worse effect of the comparative Higg Index study is to come when checking sustainability of wool through global warming and Co2 emissions factor. Here the measurements are the least satisfying in the whole compared group of textiles, with wool having more than 5 times higher contribution to climate changes then cotton, 4,8 times higher than polyamide and 4,7 times than polyester.

As it has been clarified at the begging of this paper, greenwashing is projected also via avoiding complete information about true eco-cost of a product. Likewise, communication on the wool industry linked main webpages lacks other and more complex metrics, polishing the fibres green image through nominated complements. As it has been presented above in academic and LCA studies, wool’s sustainability is literally crushed with the undeniable data and numbers. The above outcomes do not leave much for a debate, as in majority of the scientific analysis, wool gives worse environmental performance than compared synthetics. Therefore selective wool attribution to sustainability and publicizing information in a discriminating way to its rivals could be treated as another exposed greenwashing technique.

4.3. Biodegradation as a Greenwashing Exit Door

Biodegradation is a commonly used word in greening commodities or services. What shall be emphasized, most of materials/ objects in the world decompose. Some in shorter period of time, others in longer. It depends on the physical and chemical circumstances in which an object happens to remain.

“(…) Biodegradable material can be defined as a substance that can be decomposed by bacteria or other organic matter and does not add to the pollution. Biodegradable waste is waste that is present and can be damaged by organic matter such as bacteria (e.g. bacteria, fungi and a few others), abiotic elements such as temperature, UV, oxygen, etc. Other examples of this contamination of food items, kitchen waste and other natural waste. Microorganisms and other abiotic elements together divide complex organisms into living organisms that eventually hang in the soil. The whole process is natural which may be faster or slower. Therefore, environmental problems and the dangers caused by biodegradable wastes are low.

[46]

The decomposition degree is different due to the fact that microorganisms and pollutants do not spread equally in the environment [47], followed by explanation what biodegradation means for the environment:

“Physical decomposition is when materials are broken down into smaller pieces, but the material remains unchanged. Erosion of soil and rock is an example of physical decomposition. Chemical decomposition occurs when materials are chemically changed in a reaction, and the products differ from the original compounds chemically. Biodegradation is an example of chemical decomposition performed by living organisms”.

[44]

According to the above, it is an obvious process, that most of surrounding us bodies are condemned to. Although Woolmark admits it on its webpage: “All materials of animal and vegetable origin have some degree of biodegradability”, it highlights that “Natural fibres, such as Merino wool, are 100% biodegradable in both land and marine environments. So you can wear, care, recycle and dispose of your woolies with confidence that Mother Nature won’t suffer”, “When 100% Merino wool fabrics are disposed of, it will naturally decompose (…) slowly releasing valuable nutrients back into the earth” [36]. CFDA refers to the same narration “In terms of sustainability, wool is a renewable resource that is biodegradable.”, “Cloudwool® is a fabric for the Circular Economy: Natural, Recyclable and Biodegradable [32]. British Wool claims “Products made out of synthetic fibres can take up to 40 years to degrade, while wool – a natural fibre – degrades in a fraction of that time” [35]. AWI continues in similar tone “Australian wool is truly sustainable; it is 100% natural, renewable and biodegradable” [31]. IWTO is not an exemption in writing “The research is absolutely clear that wool biodegrades safely” (IWTO) [30]. Not surprisingly, the above two organizations use similar comparisons as they refer to the same research by IWTO, surprisingly discovering a common knowledge, that wool fibres readily biodegrade in marine environments, what on AWI webpage is acclaimed “A substantial body of research” [31]. Moreover, wool in the business communicates is presented almost like a remedy to the environment through its biodegradation: “When a wool item finally reaches the end of its useful life, it can be recycled to make new yarn or be discarded onto the compost heap, where it naturally biodegrades, putting nutrients back into the soil” Woolmark writes [36]. American Wool is consequent here as it likewise reaches for environmental optimism around wool through biodegradation issue “Wool biodegrades in soil without harm to the planet and the environment, fulfilling optimum life-cycle benefits” [33].

The analysed umbrella organizations do not only inspire each other in wool green marketing, but also cooperate in studies dedicated to strengthening the sound of such narration. As referred, on IWTO website a document is placed, a report signed by IWTO and authored by dr. Paul Swan “Wool is Biodegradable” with subtitle “Ready Biodegradability is Crucial to Sustainability”. The report is sponsored by American Wool.

Whether there is no argument to ignore the aspect of decomposition or its influence on nature of any material object, it is not a determinant in the environmental footprint evaluation. Often, it is not even considered in LCA studies. For example, according to a major environmental calculation of Swedish fashion consumption, which inspected the impact of the annual consumption of textiles in Sweden, the research deducted that the production of a garment is the dominant phase in its eco footprint. Fibre production accounts for 17% and fabric production for 42%, resulting in half’s of the product’s total impact on the climate. End of life was accounted for 0 % on the eco footprint list [38,39]. No other similar contradictory study results could be tracked in academic research thusly making wool industry persistent eco-arrangement with biodegradation in its communication another example of greenwashing. Summing up with citation from Mecking [48], who writes: “Biologically degradable materials based on renewable resources are certainly not per se as “green” as they might appear at first sight”(p.1084).

5. Conclusions

The objective of this work has been to quantify greenwashing of wool via the industry’s internet communicates. As it has been explained, in context of environmental implications, the wool business has been guiding perceptions towards environmental accountability of this fibre via cunning circumstantial wool presentation and verbal directing, what is in the line with presented greenwashing definitions. The wool business shapes public views through abusive usage of adjective ‘natural’ and via juggling with biodegradation issue, which in fact, both have insignificant share in LCA or The Higg Index complete evaluations. As it has been clarified, the industry also grasps undeserved designation related to sustainability via cultivation of negative comparisons to other materials, mostly synthetics, through selected, convenient for such contrasts features. The advantage by wool industry is mainly taken by avoiding a broader context and not addressing or measuring the whole product’s environmental footprint. In light of such practice, and additionally by escaping LCA or The Higg Index accessible data references, wool industry hides negative scores of this fibre ecosystem impacts. These are sets of features that are coherently organized in a way to achieve green reflections on wool, making it nothing else, but greenwashing. The article’s point of view has been reasoned with firm data and shown examples, making a departure point for a broader research and wider discussion.

References

- The Higg Index. "Wool.” The Sustainable Apparel Coalition, accessed January 7, 2024, https://howtohigg.org/.

- Muthu, S. S., ed. Roadmap to Sustainable Textiles and Clothing: Environmental and Social Aspects of Textiles and Clothing Supply Chain; Springer: Singapore, 2014.

- Martin, M. "Creating Sustainable Apparel Value Chains—a Primer on Industry Transformation." Accessed April 25, 2014. http://www.ifc.org/.

- Yudina, A. "The Higg Index: A Way to Increase Sustainable Consumer Behavior." University of Colorado, 2017.

- Laitala, K., Klepp, I. G., and Henry, B. "Does Use Matter? Comparison of Environmental Impacts of Clothing Based on Fiber Type." Sustainability 2018, 10, 2524. [CrossRef]

- Radhakrishnan, S. "The Sustainable Apparel Coalition and the Higg Index." In Roadmap to Sustainable Textiles and Clothing: Regulatory Aspects and Sustainability Standards of Textiles and the Clothing Supply Chain; Springer: Singapore, 2014; pp. 23-57.

- Reichard, R. Textiles 2013: The Turnaround Continues. Available online: http://www.textileworld.com (accessed on 1 May 2014).

- Williams, A., Hodges, N., and Watchravesringkan, K. "An Index Is Worth a Thousand Words: Considering Consumer Perspectives in the Development of a Sustainability Label." Cleaner and Responsible Consumption 2023, 11, 100148. [CrossRef]

- KPMG. "Business Digital Transformation Monitor Edition 2023." January 7, 2024, https://kpmg.com/pl/en/home/insights/2023/06/report-business-digital-transformation-monitor-edition-2023.html.

- Carrières, V., Lemieux, A. A., Margni, M., Pellerin, R., and Cariou, S. "Measuring the Value of Blockchain Traceability in Supporting LCA for Textile Products." Sustainability 2022, 14, 2109. [CrossRef]

- Piontek, F. M., and Müller, M. "Literature Reviews: Life Cycle Assessment in the Context of Product-Service Systems and the Textile Industry." Procedia CIRP 2018, 69, 758-763. [CrossRef]

- De Abreu, M. C. S. "Perspectives, Drivers, and a Roadmap for Corporate Social Responsibility in the Textile and Clothing Industry." In Roadmap to Sustainable Textiles and Clothing: Regulatory Aspects and Sustainability Standards of Textiles and the Clothing Supply Chain; Springer, 2015; pp. 1-21.

- Finnveden, G., and Potting, J. "Life Cycle Assessment." In Encyclopedia of Toxicology; 2014; pp. 74-77.

- Dahllöf, L. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) Applied in the Textile Sector: The Usefulness, Limitations and Methodological Problems – A Literature Review. 2003.

- Curteza, A. "Sustainable Textiles." Radar 2011, 2, 19-21.

- Feldstein, S., Hakansson, E., and Katcher, J. Shear Destruction: Wool, Fashion, and the Biodiversity Crisis. A report by the Center for Biological Diversity and Collective Fashion Justice’s Circumfauna Initiative. 2021.

- Bianco, I., Picerno, G., and Blengini, G. A. "Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) of Worsted and Woollen Processing in Wool Production: ReviWool® Noils and Other Wool Co-Products." Journal of Cleaner Production 2023, 137877. [CrossRef]

- Devaux, C. A. Wool Production, Systematic Review of Life Cycle Assessment Studies. 2019.

- Wiedemann, S. G., Simmons, A., Watson, K. J., and Biggs, L. "Effect of Methodological Choice on the Estimated Impacts of Wool Production and the Significance for LCA-Based Rating Systems." The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment 2019, 24, 848-855. [CrossRef]

- Wiedemann, S. G., Ledgard, S. F., Henry, B. K., Yan, M. J., Mao, N., and Russell, S. J. "Application of Life Cycle Assessment to Sheep Production Systems: Investigating Co-Production of Wool and Meat Using Case Studies from Major Global Producers." The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment 2015, 20, 463-476. [CrossRef]

- Brock, P. M., Graham, P., Madden, P., and Alcock, D. J. "Greenhouse Gas Emissions Profile for 1 kg of Wool Produced in the Yass Region, New South Wales: A Life Cycle Assessment Approach." Animal Production Science 2013, 53, 495-508. [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, A., Ramalho, E., Gouveia, A., Henriques, R., Figueiredo, F., and Nunes, J. "Systematic Insights into a Textile Industry: Reviewing Life Cycle Assessment and Eco-Design." Sustainability 2023, 15, 15267. [CrossRef]

- Henry, B. Understanding the Environmental Impacts of Wool: A Review of Life Cycle Assessment Studies. International Wool Textile Organisation, Brussels, Belgium, 2012.

- Grevinga, T. H., Lurvink, M., Brinks, G., & Luiken, A. (2017). Going eco, going dutch: A local and closed loop textile production system.

- Jugend, D., de Figueiredo, R. J., & Pinheiro, M. A. P. (2017). Environmental sustainability and product portfolio management in biodiversity firms: A comparative analysis between Portugal and Brazil. Contemporary Economics, 11(4), 431-442.

- Plonka, M. B. "Implementing CSR in the Fashion Industry: Measuring the Designers' Perceptions and Commitment." 2019.

- De Freitas Netto, S. V., Sobral, M. F. F., Ribeiro, A. R. B., and Soares, G. R. D. L. "Concepts and Forms of Greenwashing: A Systematic Review." Environmental Sciences Europe 2020, 32, 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Newbery, M., and Ghosh-Curling, R. Chapter 7 CSR: Do Fashion Retailers and Clothing Suppliers Behave with Corporate Social Responsibility? In The Just-Style Green Report; Aroq Limited: Bromsgrove, UK, 2011.

- Walker, K., and Wan, F. "The Harm of Symbolic Actions and Green-Washing: Corporate Actions and Communications on Environmental Performance and Their Financial Implications." Journal of Business Ethics 2012, 109, 227-242. [CrossRef]

- IWTO. "Sustainability." IWTO, accessed January 7, 2024, https://iwto.org/sustainability/.

- AWI. "Sustainability." AWI, accessed January 7, 2024, https://www.wool.com/sustainability/.

- CFDA. "Wool." CFDA, accessed January 7, 2024, https://cfda.com/resources/materials/detail/wool.

- American Wool. "Natural & Biodegradable." American Wool, accessed January 7, 2024, https://www.americanwool.org/wool-101/natural-biodegradable/.

- Trust in Australian Wool. "Sustainability." Trust in Australian Wool, accessed January 7, 2024, https://trustinaustralianwool.com.au/sustainability/.

- British Wool. "Sustainability." British Wool, accessed January 7, 2024, https://shop.britishwool.org.uk/sustainability/.

- Woolmark. "Wool as a Sustainable Fibre for Textiles." Accessed January 7, 2024. https://www.woolmark.com/industry/sustainability/wool-is-a-sustainable-fibre/.

- Hyde, M. "Natural's Not in It: Just Because a Product Calls Itself 'Natural' Doesn't Make It Good." The Guardian, accessed January 7, 2024, https://www.theguardian.com.

- Roos, S., Sandin, G., Zamani, B., and Peters, G. "Environmental Assessment of Swedish Fashion Consumption: Five Garments—Sustainable Futures." Mistra Future Fashion, 2015.

- La Rosa, A. D., and Grammatikos, S. A. "Comparative Life Cycle Assessment of Cotton and Other Natural Fibers for Textile Applications." Fibers 2019, 7, 101.

- Collins Dictionary. "Natural." Collins Dictionary, accessed January 7, 2024, https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/natural.

- Oxford Dictionary. "Natural." Oxford Dictionary, accessed January 7, 2024, https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/definition/english/natural_1.

- Cambridge Dictionary. "Natural." Cambridge Dictionary, accessed January 7, 2024, https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/natural.

- Bianco, I., De Bona, A., Zanetti, M., and Panepinto, D. "Environmental Impacts in the Textile Sector: A Life Cycle Assessment Case Study of a Woolen Undershirt." Sustainability 2023, 15, 11666. [CrossRef]

- Bianco, I., De Bona, A., Zanetti, M., and Panepinto, D. "Environmental Impacts in the Textile Sector: A Life Cycle Assessment Case Study of a Woolen Undershirt." Sustainability 15, no. 15, 11666. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Cosgrove, J., and Ertmann, J. What is Biodegradable? In Composting by Microbes. Science in the Real World. Microbes in Action. University of Missouri-St. Louis, 2002.

- Kayne, L. "Clothing Industry Giants Launch Sustainable Apparel Coalition." The Guardian, accessed January 7, 2024, https://www.theguardian.com.

- Kevin, W. Brief Note on Biodegradation and Its Types. Department of Environmental Science, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York, USA, 2022.

- Mahmoud, D. A. "Mechanism of Microbial Biodegradation: Secrets of Biodegradation." In Handbook of Biodegradable Materials; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 179-193.

- Mecking, S. "Nature or Petrochemistry?—Biologically Degradable Materials." Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2004, 43, 1078-1085. [CrossRef]

- Seele, P., and Gatti, L. "Greenwashing Revisited: In Search of a Typology and Accusation-Based Definition Incorporating Legitimacy Strategies." Business Strategy and the Environment 2017, 26, 239-252. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).