Submitted:

11 June 2024

Posted:

12 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

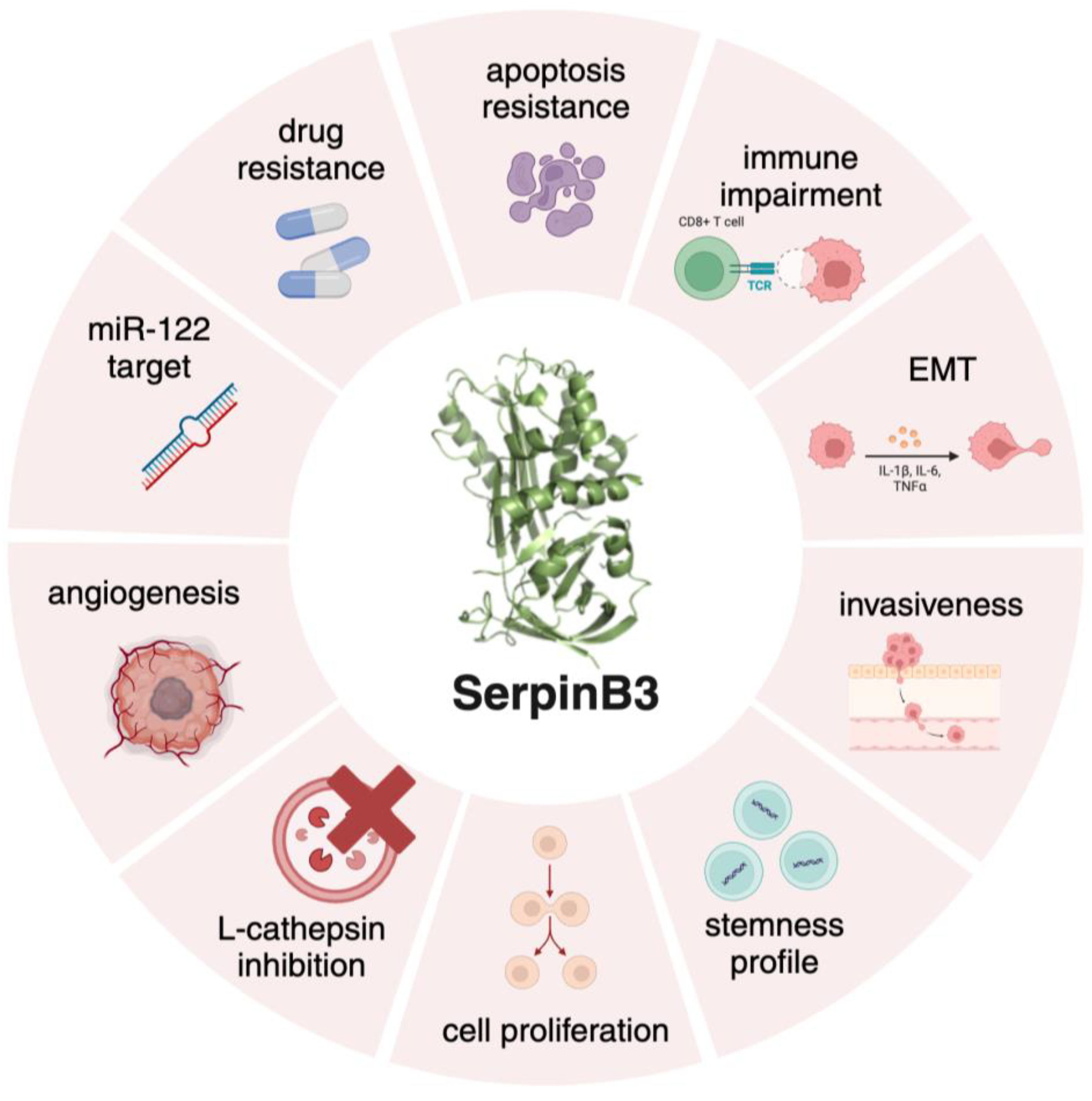

2. SerpinB3 in Fibrosis and Carcinogenesis

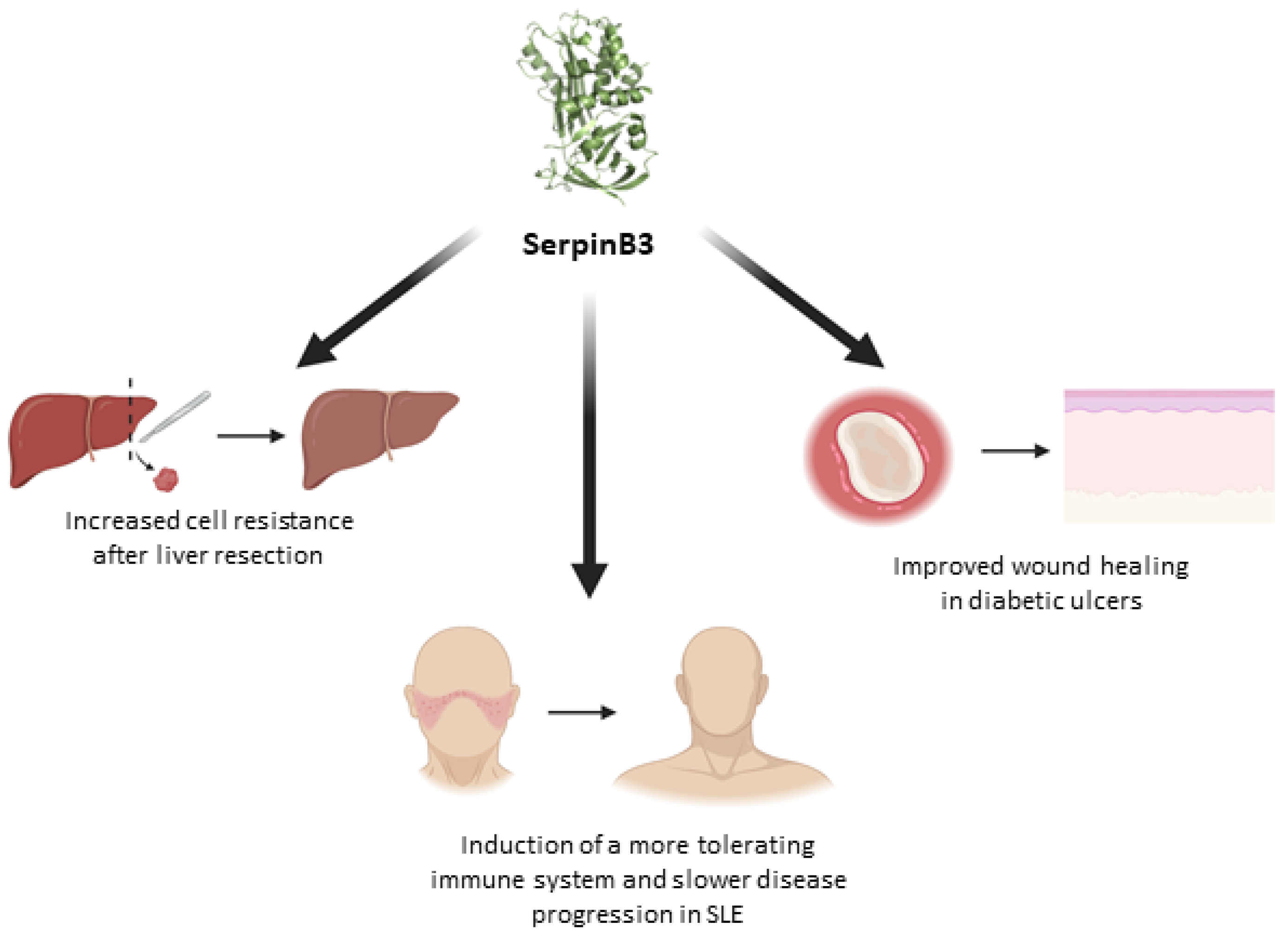

3. SerpinB3 as a Promising Protective Molecule

4. The Future, a Novel Druggable Target for SerpinB3 Inhibition?

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Heit, C.; Jackson, B.C.; Mcandrews, M.; Wright, M.W.; Thompson, D.C.; Silverman, G.A.; Nebert, D.W.; Vasiliou, V. Update of the human and mouse SERPIN gene superfamily.

- Izuhara, K.; Ohta, S.; Kanaji, S.; Shiraishi, H.; Arima, K. Recent progress in understanding the diversity of the human ov-serpin/clade 2013, B. serpin family. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 2008, 65, 2541–2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezaie, A.R.; Giri, H. Anticoagulant and signaling functions of antithrombin. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis 2020, 18, 3142–3153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Wang, J.; Gao, J.; Yang, H.; Wang, Y.; Manithody, C.; Li, J.; Rezaie, A.R. Antithrombin up-regulates AMP-activated protein kinase signalling during myocardial ischaemia/reperfusion injury. Thromb Haemost 2015, 113, 338–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janciauskiene, S.M.; Bals, R.; Koczulla, R.; Vogelmeier, C.; Köhnlein, T.; Welte, T. The discovery of α1-antitrypsin and its role in health and disease. Respir Med 2011, 105, 1129–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Law, R.H.P.; Zhang, Q.; McGowan, S.; et al. An overview of the serpin superfamily. Genome Biol 2006, 7, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silverman, G.A.; Bird, P.I.; Carrell, R.W.; et al. The serpins are an expanding superfamily of structurally similar but functionally diverse proteins. Evolution 2001, 276, 33293–33296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, H.; Torigoe, T. Radioimmunoassay for tumor antigen of human cervical squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer 1977, 40, 1621–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suminami, Y.; Kishi, F.; Sekiguchi, K.; Kato, H. Squamous cell carcinoma antigen is a new member of the serine protease inhibitors. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1991, 181, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, R.C.; Worrall, D.M. Identification of a novel human serpin gene; cloning sequencing and expression of leupin. FEBS Lett 1995, 373, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, S.S.; Schick, C.; Fish, K.E.; Miller, E.; Pena, J.C.; Treter, S.D.; Hui, S.M.; Silverman, G.A.; Sager, R. A serine proteinase inhibitor locus at 18q21.3 contains a tandem duplication of the human squamous cell carcinoma antigen gene (serpins/maspin/plasminogen activator inhibitor type 2).

- Zheng, B.; Matoba, Y.; Kumagai, T.; Katagiri, C.; Hibino, T.; Sugiyama, M. 2009. Crystal structure of SCCA1 and insight about the interaction with JNK1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1995, 380, 143–147. [Google Scholar]

- Askew, D.J.; Askew, Y.S.; Kato, Y.; Turner, R.F.; Dewar, K.; Lehoczky, J.; Silverman, G.A. Comparative genomic analysis of the clade, B. serpin cluster at human chromosome 18q21: amplification within the mouse squamous cell carcinoma antigen gene locus. Genomics 2004, 84, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schick, C.; Bromme, D.; Bartuski, A.J.; Uemura, Y.; Schechter, N.M.; Silverman, G.A. The reactive site loop of the serpin SCCA1 is essential for cysteine proteinase inhibition. 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Schick, C.; Pemberton, P.A.; Shi, G.-P.; Kamachi, Y.; Çataltepe, S.; Bartuski, A.J.; Gornstein, E.R.; Brömme, D.; Chapman, H.A.; Silverman, G.A. Cross-Class Inhibition of the Cysteine Proteinases Cathepsins, K, L, and, S. by the Serpin Squamous Cell Carcinoma Antigen, 1, A Kinetic Analysis. Biochemistry, 1998; 37, 5258–5266. [Google Scholar]

- Schick, C.; Kamachi, Y.; Bartuski, A.J.; Çataltepe, S.; Schechter, N.M.; Pemberton, P.A.; Silverman, G.A. Squamous Cell Carcinoma Antigen 2 Is a Novel Serpin That Inhibits the Chymotrypsin-like Proteinases Cathepsin, G and Mast Cell Chymase. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1997, 272, 1849–1855. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Sheshadri, N.; Zong, W.X. SERPINB3 and B4: From biochemistry to biology. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2017, 62, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tolomeo, A.M.; Quarta, S.; Biasiolo, A.; et al. Engineered EVs for oxidative stress protection. Pharmaceuticals. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidalino, L.; Doria, A.; Quarta, S.; Zen, M.; Gatta, A.; Pontisso, P. SERPINB3, apoptosis and autoimmunity. Autoimmun Rev 2009, 9, 108–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciscato, F.; Sciacovelli, M.; Villano, G.; Turato, C.; Bernardi, P.; Rasola, A.; Pontisso, P. SERPINB3 protects from oxidative damage by chemotherapeutics through inhibition of mitochondrial respiratory complex I. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Numa, F.; Takeda, O.; Nakata, M.; Nawata, S.; Tsunaga, N.; Hirabayashi, K.; Suminami, Y.; Kato, H.; Hamanaka, S. 1996. Tumor necrosis factor a stimulates the production of squamous cell carcinoma antigen in normal squamous cells. Tumor Biology 97–101.

- Catanzaro, J.M.; Sheshadri, N.; Zong, W.X. SerpinB3/B4: Mediators of ras-driven inflammation and oncogenesis. Cell Cycle 2014, 13, 3155–3156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catanzaro, J.M.; Sheshadri, N.; Pan, J.A.; Sun, Y.; Shi, C.; Li, J.; Powers, R.S.; Crawford, H.C.; Zong, W.X. Oncogenic Ras induces inflammatory cytokine production by upregulating the squamous cell carcinoma antigens SerpinB3/B4. Nat Commun. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Sheshadri, N.; Zong, W.X. SERPINB3 and B4: From biochemistry to biology. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2017, 62, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quarta, S.; Vidalino, L.; Turato, C.; et al. SERPINB3 induces epithelial - Mesenchymal transition. Journal of Pathology 2010, 221, 343–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Shi, V.; Wang, S.; et al. SCCA1/SERPINB3 suppresses antitumor immunity and blunts therapy-induced, T. cell responses via STAT-dependent chemokine production. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, F.; Lunardi, F.; Giacometti, C.; et al. Overexpression of squamous cell carcinoma antigen in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: Clinicopathological correlations. Thorax 2008, 63, 795–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turato, C.; Calabrese, F.; Biasiolo, A.; et al. SERPINB3 modulates TGF-Β expression in chronic liver disease. Laboratory Investigation 2010, 90, 1016–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novo, E.; Villano, G.; Turato, C.; et al. SerpinB3 promotes pro-fibrogenic responses in activated hepatic stellate cells. Sci Rep. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turato, C.; Biasiolo, A.; Pengo, P.; et al. Increased antiprotease activity of the SERPINB3 polymorphic variant SCCA-PD. Exp Biol Med 2011, 236, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, A.; Turato, C.; Cannito, S.; et al. The polymorphic variant of SerpinB3 (SerpinB3-PD) is associated with faster cirrhosis decompensation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2024, 59, 380–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turato, C.; Vitale, A.; Fasolato, S.; et al. SERPINB3 is associated with TGF-β1 and cytoplasmic β-catenin expression in hepatocellular carcinomas with poor prognosis. Br J Cancer 2014, 110, 2708–2715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terrin, L.; Agostini, M.; Ruvoletto, M.; Martini, A.; Pucciarelli, S.; Bedin, C.; Nitti, D.; Pontisso, P. SerpinB3 upregulates the Cyclooxygenase-2 / β-Catenin positive loop in colorectal cancer.

- Debebe, A.; Medina, V.; Chen, C.Y.; et al. 2017. Wnt/β-catenin activation and macrophage induction during liver cancer development following steatosis. Oncogene 2017, 36, 6020–6029. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Valenta, T.; Hausmann, G.; Basler, K. The many faces and functions of b-catenin. EMBO Journal 2012, 31, 2714–2736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turato, C.; Buendia, M.A.; Fabre, M.; et al. Over-expression of SERPINB3 in hepatoblastoma: A possible insight into the genesis of this tumour? Eur, J. Cancer 2012, 48, 1219–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quarta, S.; Cappon, A.; Turato, C.; et al. SerpinB3 Upregulates Low-Density Lipoprotein Receptor-Related Protein (LRP) Family Members, Leading to Wnt Signaling Activation and Increased Cell Survival and Invasiveness. Biology (Basel). 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.; Wang, J.; Liu, B.; et al. Low-Density Lipoprotein Receptor-Related Protein-5 Binds to Axin and Regulates the Canonical Wnt Signaling Pathway. Mol Cell 2001, 7, 801–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, Y.; Wang, C.; Chen, S.; Liu, J.; Fu, Y.; Luo, Y. Extracellular Hsp90á and clusterin synergistically promote breast cancer epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and metastasis via LRP1. J Cell Sci. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parola, M.; Pinzani, M. Liver fibrosis: Pathophysiology, pathogenetic targets and clinical issues. Mol Aspects Med 2019, 65, 37–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nath, B.; Szabo, G. Hypoxia and hypoxia inducible factors: Diverse roles in liver diseases. Hepatology 2012, 55, 622–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cannito, S.; Paternostro, C.; Busletta, C.; Bocca, C.; Colombatto, S.; Miglietta, A.; Novo, E.; Parola, M. Hypoxia, hypoxia-inducible factors and fibrogenesis in chronic liver diseases. Histol Histopathol 2014, 29, 33–44. [Google Scholar]

- Roth, K.J.; Copple, B.L. Role of Hypoxia-Inducible Factors in the Development of Liver Fibrosis. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015, 1, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foglia, B.; Novo, E.; Protopapa, F.; Maggiora, M.; Bocca, C.; Cannito, S.; Parola, M. Hypoxia, hypoxia-inducible factors and liver fibrosis. Cells. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzner, L.M.W.; Murray, A.J. Hypoxia-Inducible Factors as Key Players in the Pathogenesis of Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Non-alcoholic Steatohepatitis. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majmundar, A.J.; Wong, W.J.; Simon, M.C. Hypoxia-Inducible Factors and the Response to Hypoxic Stress. Mol Cell 2010, 40, 294–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, G.K.; Tennant, D.A.; Mckeating, J.A. Hypoxia inducible factors in liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma: Current understanding and future directions.

- Schito, L.; Semenza, G.L. Hypoxia-Inducible Factors: Master Regulators of Cancer Progression. Trends Cancer 2016, 2, 758–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Lou, T. Hypoxia inducible factors in hepatocellular carcinoma. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- McKeown, S.R. Defining normoxia, physoxia and hypoxia in tumours - Implications for treatment response. British Journal of Radiology. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, D.; Wang, Z.; Wu, J.; Jiang, C.; Wu, J. The role of hypoxia inducible factor-1 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Biomed Res Int. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menrad, H.; Werno, C.; Schmid, T.; Copanaki, E.; Deller, T.; Dehne, N.; Brüne, B. Roles of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) versus HIF-2α in the survival of hepatocellular tumor spheroids. Hepatology 2010, 51, 2183–2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Sun, X.P.; Qiao, H.; Jiang, X.; Wang, D.; Jin, X.; Dong, X.; Wang, J.J.; Jiang, H.; Sun, X. Downregulating hypoxia-inducible factor-2a improves the efficacy of doxorubicin in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Sci 2012, 103, 528–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.X.; Xu, Y.; Yang, X.R.; et al. Hypoxia inducible factor 2 alpha inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma growth through the transcription factor dimerization partner 3/E2F transcription factor 1-dependent apoptotic pathway. Hepatology 2013, 57, 1088–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Zhai, B.; He, C.; et al. Upregulation of HIF-2α induced by sorafenib contributes to the resistance by activating the TGF-α/EGFR pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Cell Signal 2014, 26, 1030–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.-L.; Liu, L.-P.; Niu, L.; Sun, Y.-F.; Yang, X.-R.; Fan, J.; Ren, J.-W.; Chen, G.G. ; Lai PBS Downregulation and pro-apoptotic effect of hypoxia-inducible factor 2 alpha in hepatocellular carcinoma.

- Chen, J.; Chen, J.; Huang, J.; et al. HIF-2a upregulation mediated by hypoxia promotes NAFLD-HCC progression by activating lipid synthesis via the PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway. Aging 2019, 11, 10839–10860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontisso, P.; Calabrese, F.; Benvegnù, L.; et al. Overexpression of squamous cell carcinoma antigen variants in hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Cancer 2004, 90, 833–837. [Google Scholar]

- Foglia, B.; Sutti, S.; Cannito, S.; et al. Hepatocyte-Specific Deletion of HIF2α Prevents NASH-Related Liver Carcinogenesis by Decreasing Cancer Cell Proliferation. CMGH 2022, 13, 459–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turato, C.; Cannito, S.; Simonato, D.; et al. SerpinB3 and Yap Interplay Increases Myc Oncogenic Activity. Sci Rep. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannito, S.; Foglia, B.; Villano, G.; et al. Serpin B3 differently up-regulates hypoxia inducible factors -1α and -2α in hepatocellula arcinoma: Mechanisms revealing novel potential therapeutic targets. Cancers (Basel). 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novo, E.; Cappon, A.; Villano, G.; et al. SerpinB3 as a Pro-Inflammatory Mediator in the Progression of Experimental Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Front Immunol. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, X.; Kuang, H.; Ansari, S.; et al. Landscape of Intercellular Crosstalk in Healthy and NASH Liver Revealed by Single-Cell Secretome Gene Analysis. Mol Cell 2019, 75, 644–660e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rankin, E.B.; Rha, J.; Selak, M.A.; Unger, T.L.; Keith, B.; Liu, Q.; Haase, V.H. Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 2 Regulates Hepatic Lipid Metabolism. Mol Cell Biol 2009, 29, 4527–4538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, A.; Taylor, M.; Xue, X.; Matsubara, T.; Metzger, D.; Chambon, P.; Gonzalez, F.J.; Shah, Y.M. Hypoxia-inducible transcription factor 2α promotes steatohepatitis through augmenting lipid accumulation, inflammation, and fibrosis. Hepatology 2011, 54, 472–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morello, E.; Sutti, S.; Foglia, B.; et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor 2α drives nonalcoholic fatty liver progression by triggering hepatocyte release of histidine-rich glycoprotein. Hepatology 2018, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.A.; Friedman, S.L. Inflammatory and fibrotic mechanisms in NAFLD—Implications for new treatment strategies. J Intern Med 2022, 291, 11–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanwal, F.; Shubrook, J.H.; Younossi, Z.; et al. Preparing for the NASH Epidemic: A Call to Action. Gastroenterology 2021, 161, 1030–1042e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, H.; Torigoe, T. Radioimmunoassay for tumor antigen of human cervical squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer 1977, 40, 1621–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, H.; Nagaya, T.; Torigoe, T. Heterogeneity of a tumor antigen TA-4 of squamous cell carcinoma in relation to its appearance in the circulation. Gan 1984, 75, 433–435. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vassilakopoulos, T.; Troupis, T.; Sotiropoulou, C.; et al. Diagnostic and prognostic significance of squamous cell carcinoma antigen in non-small cell lung cancer. 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Stenman, J.; Hedström, J.; Grénman, R.; Leivo, I.; Finne, P.; Palotie, A.; Orpana, A. Relative levels of SCCA2 and SCCA1 mRNA in primary tumors predicts recurrent disease in squamous cell cancer of the head and neck. Int J Cancer 2001, 95, 39–43. [Google Scholar]

- Collie-Duguid, E.S.R.; Sweeney, K.; Stewart, K.N.; Miller, I.D.; Smyth, E.; Heys, S.D. SerpinB3, a new prognostic tool in breast cancer patients treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2012, 132, 807–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markovina, S.; Wang, S.; Henke, L.E.; et al. Serum squamous cell carcinoma antigen as an early indicator of response during therapy of cervical cancer. Br J Cancer 2018, 118, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turato, C.; Scarpa, M.; Kotsafti, A.; et al. Squamous cell carcinoma antigen 1 is associated to poor prognosis in esophageal cancer through immune surveillance impairment and reduced chemosensitivity. Cancer Sci 2019, 110, 1552–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martini, A.; Prasai, K.; Zemla, T.J.; et al. SerpinB3/4 Expression Is Associated with Poor Prognosis in Patients with Cholangiocarcinoma. Cancers (Basel). 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guido, M.; Roskams, T.; Pontisso, P.; Fassan, M.; Thung, S.N.; Giacomelli, L.; Sergio, A.; Farinati, F.; Cillo, U.; Rugge, M. Squamous cell carcinoma antigen in human liver carcinogenesis. J Clin Pathol 2008, 61, 445–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biasiolo, A.; Chemello, L.; Quarta, S.; et al. Monitoring SCCA-IgM complexes in serum predicts liver disease progression in patients with chronic hepatitis. J Viral Hepat 2008, 15, 246–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beneduce, L.; Castaldi, F.; Marino, M.; Quarta, S.; Ruvoletto, M.; Benvegnù, L.; Calabrese, F.; Gatta, A.; Pontisso, P.; Fassina, G. Squamous cell carcinoma antigen-immunoglobulin, M. complexes as novel biomarkers for hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer 2005, 103, 2558–2565. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ullman, E.; Pan, J.-A.; Zong, W.-X. Squamous Cell Carcinoma Antigen 1 Promotes Caspase-8-Mediated Apoptosis in Response to Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress While Inhibiting Necrosis Induced by Lysosomal Injury. Mol Cell Biol 2011, 31, 2902–2919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheshadri, N.; Catanzaro, J.M.; Bott, A.J.; et al. SCCA1/SERPINB3 promotes oncogenesis and epithelial-mesenchymal transition via the unfolded protein response and IL6 signaling. Cancer Res 2014, 74, 6318–6329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suminami, Y.; Nagashima, S.; Vujanovic, N.L.; Hirabayashi, K.; Kato, H.; Whiteside, T.L. Inhibition of apoptosis in human tumour cells by the tumour-associated serpin, SCC antigen-1. Br J Cancer 2000, 82, 981–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katagiri, C.; Nakanishi, J.; Kadoya, K.; Hibino, T. Serpin squamous cell carcinoma antigen inhibits UV-induced apoptosis via suppression of c-JUN NH2-terminal kinase. Journal of Cell Biology 2006, 172, 983–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murakami, A.; Suminami, Y.; Hirakawa, H.; Nawata, S.; Numa, F.; Kato, H. Squamous cell carcinoma antigen suppresses radiation-induced cell death. Br J Cancer 2001, 84, 851–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciscato, F.; Sciacovelli, M.; Villano, G.; Turato, C.; Bernardi, P.; Rasola, A.; Pontisso, P. SERPINB3 protects from oxidative damage by chemotherapeutics through inhibition of mitochondrial respiratory complex I. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Villano, G.; Turato, C.; Quarta, S.; et al. Hepatic progenitor cells express SerpinB3. BMC Cell Biol. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turato, C.; Fornari, F.; Pollutri, D.; Fassan, M.; Quarta, S.; Villano, G.; Ruvoletto, M.; Bolondi, L.; Gramantieri, L.; Pontisso, P. MiR-122 targets serpinB3 and is involved in sorafenib resistance in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Med. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakral, S.; Ghoshal, K. miR-122 is a Unique Molecule with Great Potential in Diagnosis, Prognosis of Liver Disease, and Therapy Both as miRNA Mimic and Antimir. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Castoldi, M.; Spasic, M.V.; Altamura, S.; et al. The liver-specific microRNA miR-122 controls systemic iron homeostasis in mice. Journal of Clinical Investigation 2015, 121, 1386–1396. [Google Scholar]

- Ranganathan, S.; Tan, X.; Monga, S.P.S. β-Catenin and Met Deregulation in Childhood Hepatoblastomas. Pediatric and Developmental Pathology 2005, 8, 435–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cairo, S.; Armengol, C.; De Reyniès, A.; et al. Hepatic Stem-like Phenotype and Interplay of Wnt/β-Catenin and Myc Signaling in Aggressive Childhood Liver Cancer. Cancer Cell 2008, 14, 471–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmermann, A. The emerging family of hepatoblastoma tumours: From ontogenesis to oncogenesis. Eur J Cancer 2005, 41, 1503–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marquardt, J.U.; Raggi, C.; Andersen, J.B.; et al. Human hepatic cancer stem cells are characterized by common stemness traits and diverse oncogenic pathways. Hepatology 2011, 54, 1031–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamashita, T.; Honda, M.; Nakamoto, Y.; et al. Discrete nature of EpCAM+ and CD90+ cancer stem cells in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2013, 57, 1484–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Correnti, M.; Cappon, A.; Pastore, M.; et al. The protease-inhibitor SerpinB3 as a critical modulator of the stem-like subset in human cholangiocarcinoma. Liver International 2022, 42, 233–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raggi, C.; Invernizzi, P.; Andersen, J.B. Impact of microenvironment and stem-like plasticity in cholangiocarcinoma: Molecular networks and biological concepts. J Hepatol 2015, 62, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raggi, C.; Correnti, M.; Sica, A.; et al. Cholangiocarcinoma stem-like subset shapes tumor-initiating niche by educating associated macrophages. J Hepatol 2017, 66, 102–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, J.B.; Spee, B.; Blechacz, B.R.; et al. Genomic and Genetic Characterization of Cholangiocarcinoma Identifies Therapeutic Targets for Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors. Gastroenterology 2012, 142, 1021–1031e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, H.; Arai, Y.; Totoki, Y.; et al. Genomic spectra of biliary tract cancer. Nat Genet 2015, 47, 1003–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gringeri, E.; Biasiolo, A.; Di Giunta, M.; et al. Bile detection of squamous cell carcinoma antigen (SCCA) in extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Digestive and Liver Disease 2023, 55, 534–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Luke, C.J.; Pak, S.C.; et al. SERPINB3 (SCCA1) inhibits cathepsin, L. and lysoptosis 2022, protecting cervical cancer cells from chemoradiation. Commun Biol. [CrossRef]

- Mali, S.B. Review of STAT3 (Signal Transducers and Activators of Transcription) in head and neck cancer. Oral Oncol 2015, 51, 565–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takemoto, S.; Ushijima, K.; Kawano, K.; et al. Expression of activated signal transducer and activator of transcription-3 predicts poor prognosis in cervical squamous-cell carcinoma. Br J Cancer 2009, 101, 967–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.H.; Lu, S. A meta-analysis of STAT3 and phospho-STAT3 expression and survival of patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. European Journal of Surgical Oncology 2014, 40, 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.; Pal, S.K.; Reckamp, K.; Figlin, R.A.; Yu, H. STAT3: A Target to Enhance Antitumor Immune Response. pp 41–59. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bu, L.L.; Yu, G.T.; Wu, L.; Mao, L.; Deng, W.W.; Liu, J.F.; Kulkarni, A.B.; Zhang, W.F.; Zhang, L.; Sun, Z.J. STAT3 Induces Immunosuppression by Upregulating PD-1/PD-L1 in HNSCC. J Dent Res 2017, 96, 1027–1034. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T.; Niu, G.; Kortylewski, M.; et al. Regulation of the innate and adaptive immune responses by Stat-3 signaling in tumor cells. Nat Med 2004, 10, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, W.; Kim, H.S.; Jeong, W.; et al. SERPINB3 in the Chicken Model of Ovarian Cancer: A Prognostic Factor for Platinum Resistance and Survival in Patients with Epithelial Ovarian Cancer. PLoS One. [CrossRef]

- Ohara 2012, Y.; Tang, W.; Liu, H.; et al. SERPINB3-MYC axis induces the basal-like/squamous subtype and enhances disease progression in pancreatic cancer. Cell Rep. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Y.R.; Liu, C.J.; Hu, H.; Yang, M.; Guo, A.Y. Biological Pathway-Derived TMB Robustly Predicts the Outcome of Immune Checkpoint Blockade Therapy. Cells. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadini, G.P.; Albiero, M.; Millioni, R.; et al. The molecular signature of impaired diabetic wound healing identifies serpinB3 as a healing biomarker. Diabetologia 2014, 57, 1947–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Shao, T.; Wang, J.; Huang, X.; Deng, X.; Cao, Y.; Zhou, M.; Zhao, C. An update on potential biomarkers for diagnosing diabetic foot ulcer at early stage. Biomedicine and Pharmacotherapy. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albiero, M.; Fullin, A.; Villano, G.; et al. Semisolid Wet Sol–Gel Silica/Hydroxypropyl Methyl Cellulose Formulation for Slow Release of Serpin B3 Promotes Wound Healing In Vivo. Pharmaceutics. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatto, M.; Luisetto, R.; Ghirardello, A.; et al. SERPINB3 delays glomerulonephritis and attenuates the lupus-like disease in lupus murine models by inducing a more tolerogenic immune phenotype. Front Immunol. [CrossRef]

- Villano 2018, G.; Quarta, S.; Ruvoletto, M.G.; et al. Role of squamous cell carcinoma antigen-1 on liver cells after partial hepatectomy in transgenic mice. Int 2010, 25, 137–143. [Google Scholar]

- Gringeri, E.; Villano, G.; Brocco, S.; Polacco, M.; Calabrese, F.; Sacerdoti, D.; Cillo, U.; Pontisso, P. SerpinB3 as hepatic marker of post-resective shear stress. Updates Surg 2023, 75, 1541–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.Y.; Wang, M.; Liu, Q.; Feng, D.; Wen, Y.; Xia, Y.; Colgan, S.P.; Eltzschig, H.K.; Ju, C. Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-2α Reprograms Liver Macrophages to Protect Against Acute Liver Injury Through the Production of Interleukin-6. Hepatology 2020, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taub, R. Liver regeneration: From myth to mechanism. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2004, 5, 836–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cannito, S.; Turato, C.; Paternostro, C.; et al. Hypoxia up-regulates SERPINB3 through HIF-2α in human liver cancer cells. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Akerman, P.; Cote, P.; Yang, I.; McCLAIN, C.; Nelson, S.; Bagby, G.J.; Mae Diehl, A.; Qi Yang, S.; Mc-Clain, C. Antibodies to tumor necrosis factor-a inhibit liver regeneration after partial hepatectomy. 1992. [Google Scholar]

- HEINRICH PC, BEHRMANN I, HAAN S, HERMANNS HM, MÜLLER-NEWEN G, SCHAPER F Principles of interleukin (IL)-6-type cytokine signalling and its regulation. Biochemical Journal 2003, 374, 1–20.

- Cressman, D.E.; Greenbaum, L.E.; DeAngelis, R.A.; Ciliberto, G.; Furth, E.E.; Poli, V.; Taub, R. Liver Failure and Defective Hepatocyte Regeneration in lnterleukin-6-Deficient Mice. Wiley. 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, S.T.; Darnell, J.E. Serpin B3/B4, activated by STAT3, promote survival of squamous carcinoma cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2009, 378, 821–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanke, T.; Takizawa, T.; Kabeya, M.; Kawabata, A. Physiology and pathophysiology of proteinase-activated receptors (PARs): PAR-2 as a potential therapeutic target. J Pharmacol Sci 2005, 97, 38–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suhaj, P.; Olejar, T.; Matej, R. PAR2: The Cornerstone of Pancreatic Diseases. Physiol Res 2022, 71, 583–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rana, R.; Shearer, A.M.; Fletcher, E.K.; et al. PAR2 controls cholesterol homeostasis and lipid metabolism in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Mol Metab 2019, 29, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shearer, A.M.; Wang, Y.; Fletcher, E.K.; Rana, R.; Michael, E.S.; Nguyen, N.; Abdelmalek, M.F.; Covic, L.; Kuliopulos, A. PAR2 promotes impaired glucose uptake and insulin resistance in NAFLD through GLUT2 and Akt interference. Hepatology 2022, 76, 1778–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shearer, A.M.; Rana, R.; Austin, K.; Baleja, J.D.; Nguyen, N.; Bohm, A.; Covic, L.; Kuliopulos, A. Targeting Liver Fibrosis with a Cell-penetrating Protease-activated Receptor-2 (PAR2) Pepducin. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2016, 291, 23188–23198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, H.; Chen, Z.; Chen, F.; Yao, Y.; Lai, Y.; Xu, W.; Liu, X. Tryptase Promotes the Profibrotic Phenotype Transfer of Atrial Fibroblasts by PAR2 and PPARγ Pathway. Arch Med Res 2018, 49, 568–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seitz, I.; Hess, S.; Schulz, H.; Eckl, R.; Busch, G.; Montens, H.P.; Brandl, R.; Seidl, S.; Schömig, A.; Ott, I. Membrane-type serine protease-1/matriptase induces interleukin-6 and -8 in endothelial cells by activation of protease-activated receptor-2: Potential implications in atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2007, 27, 769–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camerer, E.; Huang, W.; Coughlin, S.R.; Majerus, P.W. Tissue factor-and factor X-dependent activation of protease-activated receptor 2 by factor VIIa.

- Sullivan, B.P.; Kopec, A.K.; Joshi, N.; Cline, H.; Brown, J.A.; Bishop, S.C.; Kassel, K.M.; Rockwell, C.; Mackman, N.; Luyendyk, J.P. Hepatocyte tissue factor activates the coagulation cascade in mice. Blood 2013, 121, 1868–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bang, E.J.; Kim, D.H.; Chung, H.Y. Protease-activated receptor 2 induces ROS-mediated inflammation through Akt-mediated NF-κB and FoxO6 modulation during skin photoaging. Redox Biol 2021, 44, 102022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villano, G.; Novo, E.; Turato, C.; et al. The protease activated receptor 2 - CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein beta - SerpinB3 axis inhibition as a novel strategy for the treatment of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Mol Metab 2024, 81, 101889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chinellato, M.; Gasparotto, M.; Quarta, S.; Ruvoletto, M.; Biasiolo, A.; Filippini, F.; Spiezia, L.; Cendron, L.; Pontisso, P. 1-Piperidine Propionic Acid as an Allosteric Inhibitor of Protease Activated Receptor-2. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).