Submitted:

12 June 2024

Posted:

13 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Children

Adults

Treatment

Asthma

Prevalence

SDB in Asthmatic Patients

Children

Adults

Treatment

Aims of the Study

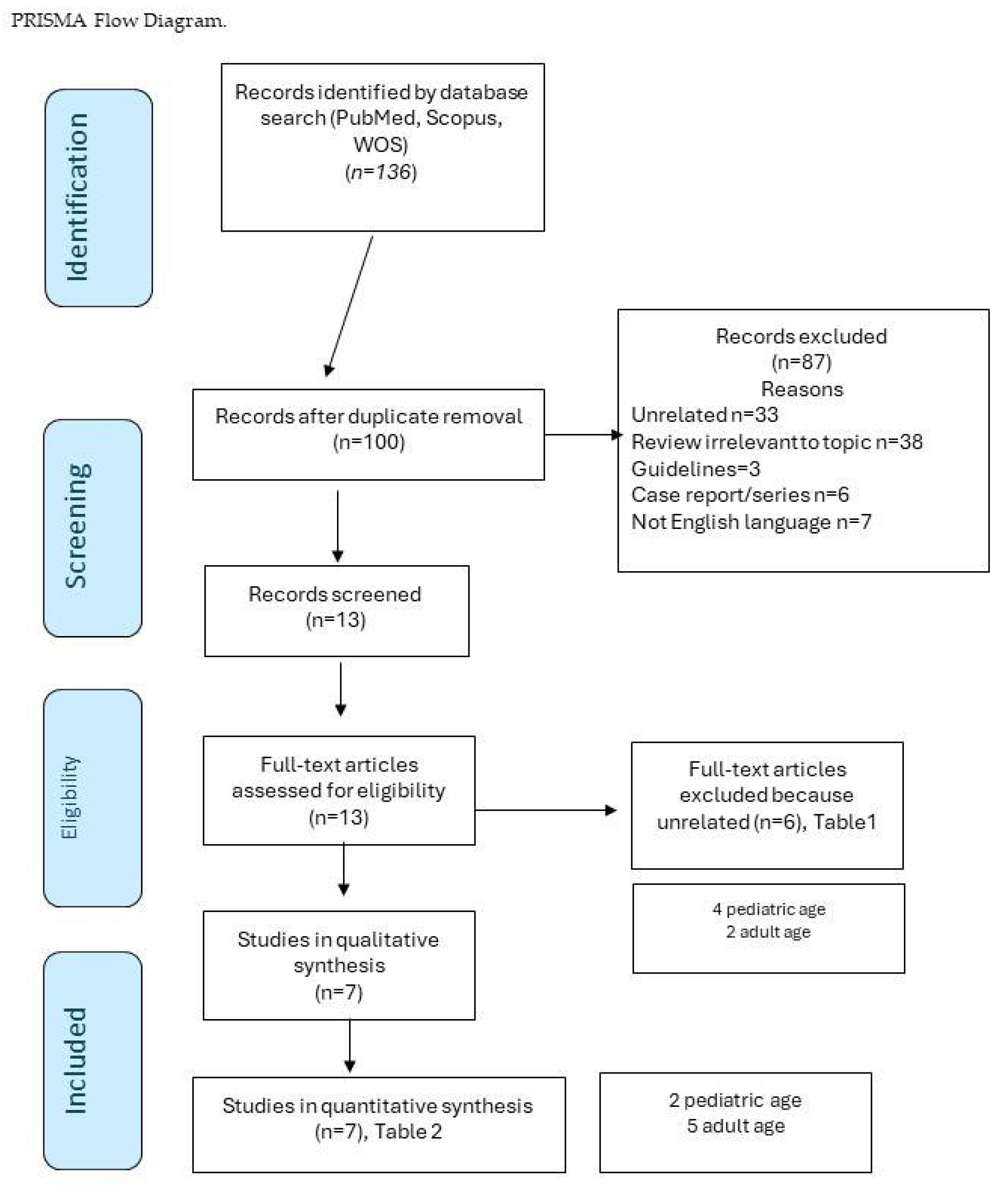

2. Materials and Methods

PICOS Criteria

3. Results

Study Data

Studies in Adulthood

Studies in Childhood

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bitners, A.C.; Arens, R. Evaluation and Management of Children with Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome. Lung 2020, 198, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharjee, R.; Kheirandish-Gozal, L.; Pillar, G.; Gozal, D. Cardiovascular Complications of Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome: Evidence from Children. Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases 2009, 51, 416–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nosetti, L.; Zaffanello, M.; Katz, E.S.; Vitali, M.; Agosti, M.; Ferrante, G.; Cilluffo, G.; Piacentini, G.; La Grutta, S. Twenty-year follow-up of children with obstructive sleep apnea. J Clin Sleep Med 2022, 18, 1573–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tagetti, A.; Bonafini, S.; Zaffanello, M.; Benetti, M.V.; Vedove, F.D.; Gasperi, E.; Cavarzere, P.; Gaudino, R.; Piacentini, G.; Minuz, P.; et al. Sleep-disordered breathing is associated with blood pressure and carotid arterial stiffness in obese children. J Hypertens 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jennum, P.; Riha, R.L. Epidemiology of sleep apnoea/hypopnoea syndrome and sleep-disordered breathing. Eur Respir J 2009, 33, 907–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franklin, K.A.; Lindberg, E. Obstructive sleep apnea is a common disorder in the population-a review on the epidemiology of sleep apnea. J Thorac Dis 2015, 7, 1311–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaffanello, M.; Ersu, R.H.; Nosetti, L.; Beretta, G.; Agosti, M.; Piacentini, G. Cardiac Implications of Adenotonsillar Hypertrophy and Obstructive Sleep Apnea in Pediatric Patients: A Comprehensive Systematic Review. Children (Basel) 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunetti, L.; Rana, S.; Lospalluti, M.L.; Pietrafesa, A.; Francavilla, R.; Fanelli, M.; Armenio, L. Prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome in a cohort of 1,207 children of Southern Italy. Chest 2001, 120, 1930–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lumeng, J.C.; Chervin, R.D. Epidemiology of pediatric obstructive sleep apnea. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2008, 5, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tishler, P.V.; Larkin, E.K.; Schluchter, M.D.; Redline, S. Incidence of sleep-disordered breathing in an urban adult population: the relative importance of risk factors in the development of sleep-disordered breathing. Jama 2003, 289, 2230–2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peppard, P.E.; Young, T.; Barnet, J.H.; Palta, M.; Hagen, E.W.; Hla, K.M. Increased prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing in adults. Am J Epidemiol 2013, 177, 1006–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.T.; Lin, Y.C.; Kuan, Y.C.; Huang, Y.H.; Hou, W.H.; Liou, T.H.; Chen, H.C. Intranasal corticosteroid therapy in the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Rhinol Allergy 2016, 30, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tauman, R.; Gozal, D. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome in children. Expert Review of Respiratory Medicine 2011, 5, 425–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mussi, N.; Forestiero, R.; Zambelli, G.; Rossi, L.; Caramia, M.R.; Fainardi, V.; Esposito, S. The First-Line Approach in Children with Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome (OSA). J Clin Med 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhle, S.; Hoffmann, D.U.; Mitra, S.; Urschitz, M.S. Anti-inflammatory medications for obstructive sleep apnoea in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2020, 1, Cd007074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tapia, I.E.; Shults, J.; Cielo, C.M.; Kelly, A.B.; Elden, L.M.; Spergel, J.M.; Bradford, R.M.; Cornaglia, M.A.; Sterni, L.M.; Radcliffe, J. A Trial of Intranasal Corticosteroids to Treat Childhood OSA Syndrome. Chest 2022, 162, 899–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Locci, C.; Cenere, C.; Sotgiu, G.; Puci, M.V.; Saderi, L.; Rizzo, D.; Bussu, F.; Antonucci, R. Adenotonsillectomy in Children with Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome: Clinical and Functional Outcomes. J Clin Med 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavwoski, P.; Shelgikar, A.V. Treatment options for obstructive sleep apnea. Neurol Clin Pract 2017, 7, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaghi, S.; Holty, J.E.; Certal, V.; Abdullatif, J.; Guilleminault, C.; Powell, N.B.; Riley, R.W.; Camacho, M. Maxillomandibular Advancement for Treatment of Obstructive Sleep Apnea: A Meta-analysis. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2016, 142, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekkanen, J.; Sunyer, J.; Anto, J.M.; Burney, P. Operational definitions of asthma in studies on its aetiology. Eur Respir J 2005, 26, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damianaki, A.; Vagiakis, E.; Sigala, I.; Pataka, A.; Rovina, N.; Vlachou, A.; Krietsepi, V.; Zakynthinos, S.; Katsaounou, P. Τhe Co-Existence of Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Bronchial Asthma: Revelation of a New Asthma Phenotype? J Clin Med 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ojo, R.O.; Okobi, O.E.; Ezeamii, P.C.; Ezeamii, V.C.; Nwachukwu, E.U.; Gebeyehu, Y.H.; Okobi, E.; David, A.B.; Akinsola, Z. Epidemiology of Current Asthma in Children Under 18: A Two-Decade Overview Using National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) Data. Cureus 2023, 15, e49229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, P.; Adeloye, D.; Salim, H.; Dos Santos, J.P.; Campbell, H.; Sheikh, A.; Rudan, I. Global, regional, and national prevalence of asthma in 2019: a systematic analysis and modelling study. J Glob Health 2022, 12, 04052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trivedi, M.; ElMallah, M.; Bailey, E.; Kremer, T.; Rhein, L.M. Pediatric Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Asthma: Clinical Implications. Pediatr Ann 2017, 46, e332–e335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garza, N.; Witmans, M.; Salud, M.; Lagera, P.G.D.; Co, V.A.; Tablizo, M.A. The Association between Asthma and OSA in Children. Children (Basel) 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salles, C.; Terse-Ramos, R.; Souza-Machado, A.; Cruz Á, A. Obstructive sleep apnea and asthma. J Bras Pneumol 2013, 39, 604–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, D.L.; Qin, Z.; Shen, H.; Jin, H.Y.; Wang, W.; Wang, Z.F. Association of Obstructive Sleep Apnea with Asthma: A Meta-Analysis. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 4088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnes, P.J. Inhaled Corticosteroids. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2010, 3, 514–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddel, H.K.; Bacharier, L.B.; Bateman, E.D.; Brightling, C.E.; Brusselle, G.G.; Buhl, R.; Cruz, A.A.; Duijts, L.; Drazen, J.M.; FitzGerald, J.M.; et al. Global Initiative for Asthma Strategy 2021: executive summary and rationale for key changes. Eur Respir J 2022, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksen, M.B.; Frandsen, T.F. The impact of patient, intervention, comparison, outcome (PICO) as a search strategy tool on literature search quality: a systematic review. J Med Libr Assoc 2018, 106, 420–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

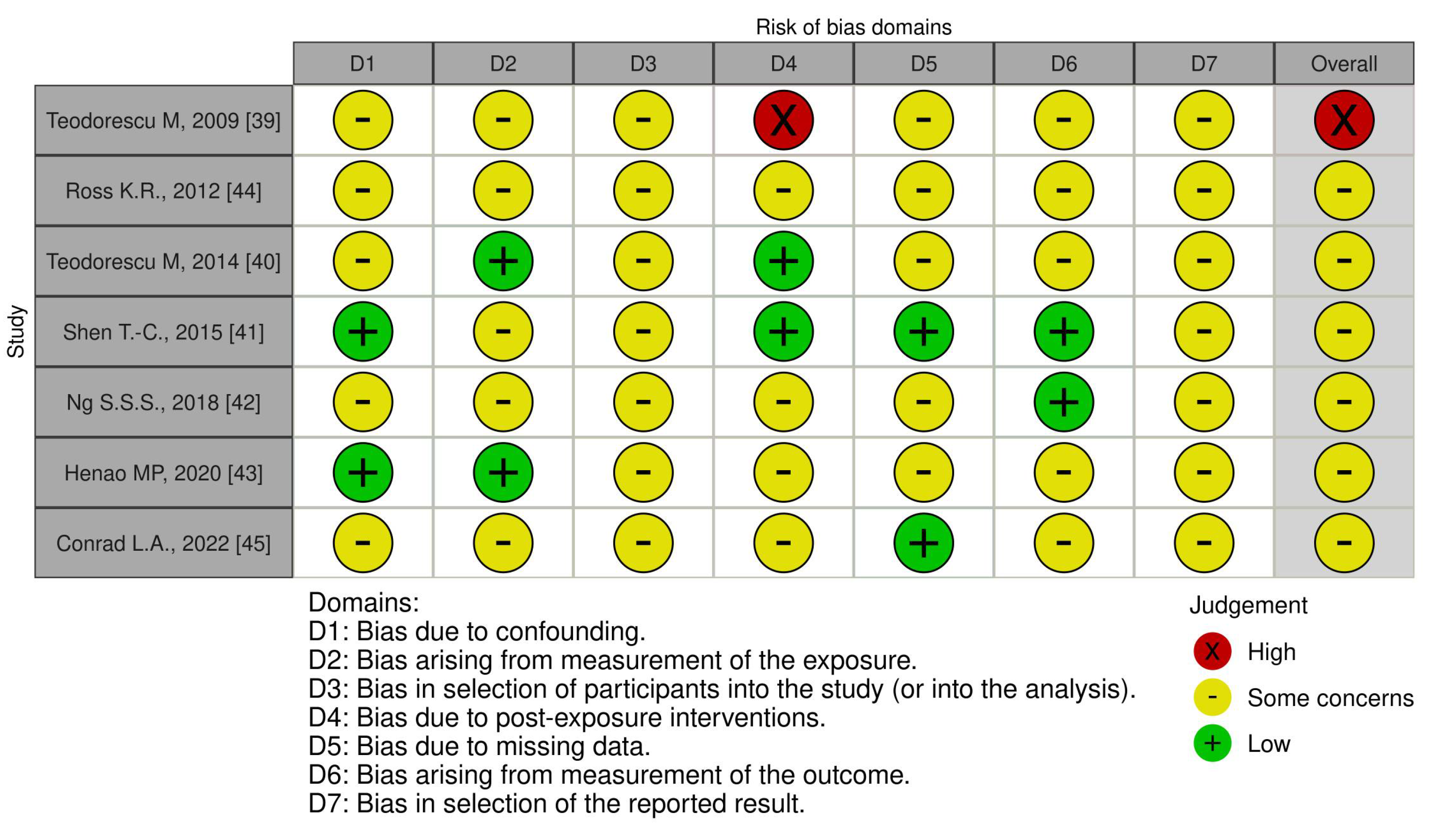

- Sterne, J.A.; Hernán, M.A.; Reeves, B.C.; Savović, J.; Berkman, N.D.; Viswanathan, M.; Henry, D.; Altman, D.G.; Ansari, M.T.; Boutron, I.; et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. Bmj 2016, 355, i4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharjee, R.; Choi, B.H.; Gozal, D.; Mokhlesi, B. Association of Adenotonsillectomy with Asthma Outcomes in Children: A Longitudinal Database Analysis. PLoS Medicine 2014, 11, e1001753–e1001753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kheirandish-Gozal, L.; Dayyat, E.A.; Eid, N.S.; Morton, R.L.; Gozal, D. Obstructive sleep apnea in poorly controlled asthmatic children: effect of adenotonsillectomy. Pediatr Pulmonol 2011, 46, 913–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfurayh, M.A.; Alturaymi, M.A.; Sharahili, A.; Bin Dayel, M.A.; Al Eissa, A.I.; Alilaj, M.O. Bronchial Asthma Exacerbation in the Emergency Department in a Saudi Pediatric Population: An Insight From a Tertiary Hospital in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Cureus 2023, 15, e33391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heatley, H.; Tran, T.N.; Bourdin, A.; Menzies-Gow, A.; Jackson, D.J.; Maslova, E.; Chapaneri, J.; Skinner, D.; Carter, V.; Chan, J.S.K.; et al. Observational UK cohort study to describe intermittent oral corticosteroid prescribing patterns and their association with adverse outcomes in asthma. Thorax 2023, 78, 860–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferguson, S.; Teodorescu, M.C.; Gangnon, R.E.; Peterson, A.G.; Consens, F.B.; Chervin, R.D.; Teodorescu, M. Factors associated with systemic hypertension in asthma. Lung 2014, 192, 675–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magnoni, M.S.; Caminati, M.; Canonica, G.W.; Arpinelli, F.; Rizzi, A.; Senna, G. Asthma management among allergists in Italy: results from a survey. Clin Mol Allergy 2017, 15, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kheirandish-Gozal, L.; Dayyat, E.A.; Eid, N.S.; Morton, R.L.; Gozal, D. Obstructive sleep apnea in poorly controlled asthmatic children: Effect of adenotonsillectomy. Pediatric Pulmonology 2011, 46, 913–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teodorescu, M.; Consens, F.B.; Bria, W.F.; Coffey, M.J.; McMorris, M.S.; Weatherwax, K.J.; Palmisano, J.; Senger, C.M.; Ye, Y.; Kalbfleisch, J.D.; et al. Predictors of habitual snoring and obstructive sleep apnea risk in patients with asthma. Chest 2009, 135, 1125–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teodorescu, M.; Xie, A.; Sorkness, C.A.; Robbins, J.; Reeder, S.; Gong, Y.; Fedie, J.E.; Sexton, A.; Miller, B.; Huard, T.; et al. Effects of inhaled fluticasone on upper airway during sleep and wakefulness in asthma: a pilot study. J Clin Sleep Med 2014, 10, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, T.C.; Lin, C.L.; Wei, C.C.; Chen, C.H.; Tu, C.Y.; Hsia, T.C.; Shih, C.M.; Hsu, W.H.; Sung, F.C.; Kao, C.H. Risk of Obstructive Sleep Apnea in Adult Patients with Asthma: A Population-Based Cohort Study in Taiwan. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0128461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, S.S.S.; Chan, T.O.; To, K.W.; Chan, K.K.P.; Ngai, J.; Yip, W.H.; Lo, R.L.P.; Ko, F.W.S.; Hui, D.S.C. Continuous positive airway pressure for obstructive sleep apnoea does not improve asthma control. Respirology 2018, 23, 1055–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henao, M.P.; Kraschnewski, J.L.; Bolton, M.D.; Ishmael, F.; Craig, T. Effects of Inhaled Corticosteroids and Particle Size on Risk of Obstructive Sleep Apnea: A Large Retrospective Cohort Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, K.R.; Storfer-Isser, A.; Hart, M.A.; Kibler, A.M.; Rueschman, M.; Rosen, C.L.; Kercsmar, C.M.; Redline, S. Sleep-disordered breathing is associated with asthma severity in children. J Pediatr 2012, 160, 736–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conrad, L.A.; Nandalike, K.; Rani, S.; Rastogi, D. Associations between sleep, obesity, and asthma in urban minority children. J Clin Sleep Med 2022, 18, 2377–2385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkhalil, M.; Schulman, E.; Getsy, J. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome and asthma: what are the links? J Clin Sleep Med 2009, 5, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- di Palmo, E.; Filice, E.; Cavallo, A.; Caffarelli, C.; Maltoni, G.; Miniaci, A.; Ricci, G.; Pession, A. Childhood Obesity and Respiratory Diseases: Which Link? Children (Basel) 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Setzke, C.; Broytman, O.; Russell, J.A.; Morel, N.; Sonsalla, M.; Lamming, D.W.; Connor, N.P.; Teodorescu, M. Effects of inhaled fluticasone propionate on extrinsic tongue muscles in rats. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2020, 128, 576–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chmielewska, M.; Akst, L.M. Dysphonia associated with the use of inhaled corticosteroids. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2015, 23, 255–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragnoli, B.; Pochetti, P.; Raie, A.; Malerba, M. Interrelationship Between Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome and Severe Asthma: From Endo-Phenotype to Clinical Aspects. Front Med (Lausanne) 2021, 8, 640636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Fu, C.; Li, W.; Jiang, H.; Wu, X.; Li, S. Screening for obstructive sleep apnea syndrome in asthma patients: a prospective study based on Berlin and STOP-Bang questionnaires. J Thorac Dis 2017, 9, 1945–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Mihaicuta, S.; Tiotiu, A.; Corlateanu, A.; Ioan, I.C.; Bikov, A. Asthma and obstructive sleep apnoea in adults and children - an up-to-date review. Sleep Med Rev 2022, 61, 101564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, C.A.; Eslick, S.R.; Berthon, B.S.; Wood, L.G. Asthma medication use in obese and healthy weight asthma: systematic review/meta-analysis. Eur Respir J 2021, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkhalil, M.; Schulman, E.S.; Getsy, J. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome and asthma: the role of continuous positive airway pressure treatment. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2008, 101, 350–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdul Razak, M.R.; Chirakalwasan, N. Obstructive sleep apnea and asthma. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol 2016, 34, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, S.E.; Bishopp, A.; Wharton, S.; Turner, A.M.; Mansur, A.H. Does Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP) treatment of obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) improve asthma-related clinical outcomes in patients with co-existing conditions?- A systematic review. Respir Med 2018, 143, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| First Author, Year | Aim of the Study | Subjects and methods | Asthma | ICS | OSA or SDB | Conclusions | Reasons of exclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHILDREN | |||||||

| Kheirandish-Gozal L, 2011 [38] | Prevalence of OSA in asthmatic PCA children. Effect of A&T on AAE frequency |

92/135 children (age 6.58 ± 1.8 years) with PCA; PSG. A&T was performed in the case of OSA. oAHI ≥5/ora TST (n.58) |

AAE (n. 92), 3.27 ± 1.13/year AAE: OSA+ (n. 58) 3.57 ± 1.37/years OSA- (n.34) 3.12 ± 1.40/years (p<0.05) |

β-rescue agonists (4.1 ± 2.4/week) β-Rescue agonists (/week): OSA+: 4,7 ± 2,9 versus OSA- 3,6 ± 2,1 (p<0,04) |

β-Rescue agonists (/week): Before T&A OSA+ (No. 35) 4.3 ± 1.8 vs. after T&A 2.1 ± 1.5 (p<0.001) Before PSG OSA- (n.24) 4.2 ± 1.9 against after PSG 3.9 ± 2.2 (p=NS) AAE (/year): Before T&A OSA+ (No. 35) 4.1 ± 1.3 vs. after T&A 1.8 ± 1.4 (p<0.001) Prima di PSG OSA- (n.24) 3,5 ± 1,5 versus dopo PSG 3,7 ± 1,7 (p=NS) |

The prevalence of OSA is higher in children with PCA Treatment of OSA by A&T is associated with improvements |

Effect of A&T on AAE Frequency in Children With PCA and Associated OSA |

| Bhattacharjee R, 2014 [32] | A&T+ Comparison with Controls, SDB, and Asthma Control | ATH A&T n.5,942 (44%) vs controls n.537 (2%) |

AAE decreased from 2,243 (30%) pre-A&T to 1,566 (2%) post-A&T in children (p<0.0001) Annual reduction in the incidence of hissing by 40.3% in A&T vs. 0% in controls |

Reduction in ICS prescription 21.5% A&T vs -2.0% controls (p<0.001) ICS/LABA −2.2% A&T vs −20.1% controld (p<0.001) Reduction of continuous inhalation for the first hour by 30% in A&T vs. 0% in controls (p<0.001) |

Reduction of OSA, snoring, and/or sleep disturbances: A&T n.3603 (27%) vs controlli n.1099 (1%) |

Children A&T: 30% reduction in AAE 1 year before A&T versus 1 year after 37.9% reduction in ASAs and 35.8% reduction in asthma-related hospitalizations |

Efficacy of A&T in Improving Asthma Symptoms and Reducing SDBs |

| Alfurayh, MA, 2022 [34] | Exacerbation of Bronchial Asthma in the ED in a Paediatric Population | Cohort study: Children in ED due to asthma exacerbation. Data collection: demographics, comorbidities, and asthma-related variables. |

Visits to the ED: yes (33.9%) vs no (66.1%) Of the 123 patients who used steroids, 74% (91) had no nocturnal symptoms (p < 0.001) |

Of the 363 asthma patients (age 4.9 ± 2.5 years; 68.8% male), 33.9% (n.123) used steroids for asthma | 1.9% with FBO (n.7). Number of patients hospitalized with OSA 4.5% (p=0.203). |

Association Between Steroid Use in Asthmatic Patients, Number of ED Visits, and Nocturnal Symptoms | Steroid Use in Asthmatic Patients, Number of ED Visits, and Nocturnal Symptoms |

| Heatley H, 2023 [35] | Intermittent prescribing of OCS in asthmatic patients and the association with adverse outcomes | Cohort study. Primary Care Medical Records (ages 4–<12, 12–<18, 18–<65 and ≥65 years) received intermittent OCS Categories: prescription: single, least frequent (≥90 day range), frequent (<90 day interval) Controls: patients not treated with OCS, matched 1:1 |

Dose-response relationship between cumulative annual exposure to OCS and risk of adverse outcomes | ICS prescriptions (0, 1–3, 4–6, 7–9, 10–12, and ≥13 administrations) 12 months prior to initial OCS prescriptions: received 1–2 administrations of SABA and ≤3 of ICS Proportion of patients receiving ≥3 administrations of SABA and ≥4 of ICS at baseline increased with more frequent OCS prescriptions Higher number of ICS prescriptions in those who had more frequent OCS prescriptions |

Higher risks of adverse outcomes related to OCS, pneumonia, and OSA | Patients with asthma who received intermittent OCS have frequent prescription. Prescribing more frequent OCS associated with higher risk of adverse outcomes |

Association Between Intermittent OCS Prescribing in Asthmatic Patients and Adverse Outcomes, Such as Pneumonia and OSA |

| ADULTS | |||||||

| Ferguson S, 2014 [36] | Association Between Lower Airway Caliber, OSA, and Other Asthma-Related Factors With HTN | Multicenter study; 812 asthmatics (ages 46 ± 14) OSA scale of the SA-SDQ Medical records: HTN, OSA, spirometry and medications |

Subjects with asthma, use of ICS n.631 (78%): low dose n.189 (23%), medium dose n.235 (29%), high dose n.207 (25%) | Associations of HTN: Low-dose ICS (OR 0.86, CI 0.50-1.45), medium doses (OR 1.1, CI 0.75-1.95), and high-dose (OR 2.18, CI 1.37-3.48) |

Association of HTN with history of OSA (OR= 5.18, CI 3.66-7.32; p<0.0001) and high risk of OSA according to SA-SDQ (OR 5.18 CI 3.66-7.32, p<0.001) | Concomitant OSA has been associated with HTN | Association Between OSA and ICS, with Hypertension in Asthmatic Patients |

| Magnoni M.S., 2017 [37] | How Italian allergists deal with asthma patients | 174 questionnaires, 16 questions: epidemiology, risk factors, therapeutic approaches and adherence to therapy |

Follow-up visits at 56.5%, worsening of symptoms for 41%, percentage of visits due to adverse effects of drugs 3% |

ICS combined with LABA were considered the treatment of choice | Sleep apnea and obesity were assessed as the most important comorbidities/risk factors of PCA | Recognizing and managing OSA could be key to improving asthma control in patients | Survey or a questionnaire exploring how Italian allergists manage asthma patients, including their treatment approaches and asthma management |

| First Author, Year | Aim of the Study | Subjects and methods | Inhaled corticosteroid | Asthma | OSA o SDB | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADULTS | ||||||

| Teodorescu M, 2009 [39] | Risk Factors Associated with Habitual Snoring and OSA Risk in Asthmatic Patients | Survey 284 asthmatics (age 46 ± 13, range 18–75 years) N.143/284 (50%) had SDB or met the criteria for high OSA risk Valutazione SDB: Self-Reported OSA Symptom, SA-SDQ |

Use of ICS: n.201 (82%): Low-dose 31 Medium-dose 87 High dose 83 No. 65 patients with grade 1 asthma: n.13 (20%) with high doses of ICS n.20 (31%) senza ICS N.77 patients with grade 4 asthma => n.12 (16%) non-use of ICS n.43 (56%) high doses of ICS |

Recent spirometry data collected to assess asthma severity step: Predictors of Habitual Snoring in 244 Asthma Patients was Asthma severity step aOR 1.22 (95% CI 0.94-1.60), p=0.14 Predictors of High Risk OSA in 244 Asthma Patients was Asthma severity step aOR 1.59 (95% CI 1.23-2.06), p<0.001 |

+129% risk of OSA with low-dose ICS (OR, 2.29; C.I.95% = 0.66-7.96); +267% with mid-dose ICS (OR, 3.67; C.I.95% = 1.34-10.03) +443% with high-dose ICS (OR, 5.43; 95% C.I. = 1.96-15.05) compared to no use of ICS Dose-dependent relationship between habitual snoring and ICS dose (overall p = 0.004) Dose-dependent relationship between high OSA risk and ICS dose (overall p < 0.001) |

Increased risk of OSA associated with ICS use. Proportional increase in risk based on the dosage of ICS used. |

| Teodorescu M, 2014 [40] | Effects of Orally Inhaled FP on UAW During Sleep and Wakefulness in Asthmatic Subjects | Prospective, single group and center study Baseline: 18 participants with asthma (age 25.9 ± 6.3 years). 16-week ICS (FP) treatment Asthma duration: 14.4 ± 10.2 years. Pcrit; MRI (Fat Fraction and Volume Around the Upper Airway) Valutazione SDB: Self-Reported OSA Symptom, SA-SDQ |

High dose inhaled FP (1,760 mcg/day). Dose adherence of FP was 91.2% ± 1.7%. |

FEV1 % pretreatment 88.8 ± 1.9, post treatment 94.1 ± 0.1 (p=0.001) | AHI baseline (events/h) = 1.2 ± 2.0, improved n.8 (0.51 ± 0.48), unchanged n.8 (1.64 ± 0.79), worsened n.2 (2.40 ± 2.40) SA-SDQ baseline score = n. 18 (21.2 ± 3.9), Improved No.8 (19.38 ± 0.98) invariato n.8 (22.00 ± 1.40) Worsened No. 2 (25.00 ± 4.00) Pcrit: improved n.8 (-8.16 ± 1.36), unchanged n.8 (-8.51 ± 2.18), worsened n.2 (-7.35 ± 0.85) Changes in tongue strength with fluticasone inhaled treatment, in the anterior (p=0.02) and posterior (p=0.002) positions |

High-dose FP led to improvements in lung function (FEV1%). Improved Pcrit in some participants. No significant impact on AHI after FP treatment. No reduction in overall AHI. High-dose FP appears to be associated with an increase in fat fraction and total fat volume in surrounding upper airway structures |

| Shen T.-C., 2015 [41] | Factors Associated with Habitual Snoring and OSA Risk in Asthmatic Patients | Retrospective cohort study. With asthma: 38,840 (age 52.8 ± 18.1 years) Asthma-free: 155,347 (age 53.3 ± 18.0 years) Follow-up period: with asthma 6.95 ± 3.33 years control 6.51 ± 3.44 years SDB Rating: PSG |

OSA Risk Ratio Among Asthma Patients Based on Different Treatments ICS 11,214 (15.3 per 1000 persons/year). No ICS 13,792 (10.6 per 1000 persons/year). |

aHR +2.51 (95% CI (1.61, 2.17) of OSA in the asthmatic cohort compared to control (12.1 vs 4.84 per 1,000 person-years). OSA development during follow-up: aHR +1.87 (95% CI = 1.61-2.17) for the asthma cohort compared to the non-asthma cohort |

OSA in asthma patients: Non-steroid aHR 1 (reference) Inhaled steroid aHR 1.33 (95% CI 1.01 - 1.76) |

Overall incidence of OSA is higher in the asthmatic cohort than in the control cohort. ICS appears to be associated with an even higher incidence of OSA among asthmatic patients. |

| Henao MP, 2020 [43] | Effects of ICS on the diagnosis of OSA, with sub-analysis by particle size of ICS. |

Cohort study. 29,816 asthmatics (age 42.8 ± 21.1 years). ACT, PFT [A diagnosis of OSA was determined by ICD-9 or ICD-10 codes reported during the study period] |

Higher likelihood of OSA in ICS users with standard particle sizes (aOR +1.56, 95% CI 1.45–1.69) than in non-users There was no increased risk of OSA in users of ICS with extra-fine particles compared to asthmatics who did not use ICS (aOR 1.11, 95% CI 0.78–1.58). |

Patients with uncontrolled asthma showed a higher likelihood of receiving a diagnosis of OSA ACT score (aOR +1.60, 95% CI 1.32–1.94) among n.1380 uncontrolled asthma versus 3288 controlled asthma PFT score (aOR +1.45, 95% CI 1.19–1.77) among 1,229 uncontrolled asthma versus 1,199 controlled asthma. ICS users were more likely to have OSA, regardless of asthma control (aOR 1.58, 95% CI 1.47–1.70). |

Probability of having a diagnosis of OSA with normal-sized particle ICS (OR 1.55, 95% CI 1.11-2.16) compared to those with extra-fine particles. Increased odds of having OSA in BMI patients ≥ 25 users of normal-sized particle ICS compared to users of extra-fine particles (aOR 1.70, 95% CI 1.15-2.50). Increased odds of receiving a diagnosis of OSA in male BMI ≥ 25 users of normal-sized particle ICS compared to users of extra-fine particles (aOR 2.45, 95% CI 1.22-4.93). |

Increased risk of OSA among users of ICS with standard-sized particles, compared to non-users of ICS. No increased risk of OSA was observed among users of ICS with extra-fine particles. Patients with PCA showed a higher likelihood of OSA. The association between ICS and OSA might vary based on asthma control and individual patient characteristics, such as BMI |

| Ng S.S.S., 2018 [42] | cPAP Effect on: Asthma Control, Airway Responsiveness, Daytime Sleepiness, and Health Status in Asthmatic Patients With Nocturnal Symptoms and OSAS | Prospective, randomized controlled trial. Baseline 122 asthmatic subjects (age 50.5 ± 12.0 years). SDB Rating: PSG Patients with AHI ≥ 10 (n = 41) Patients with AHI < 10 (n = 81) CPAP group (n = 17) and control group (n = 20) |

Beclomethasone 500 μg or more per day within the last 3 months Baseline High-dose inhaled steroids 90.1% Medium-dose inhaled steroids 9.9% |

Baseline FEV1 (% predetto) 79.2 ± 20.5 No significant difference in the change of the ACT score between n.17 CPAP group 15.9 ± 2.6 vs n.20 control group 21.7 ± 10.1 (P = 0.145) |

AHI correlates with BMI (r = 0.255, P = 0.008) and neck circumference (r = 0.247, P = 0.007). No significant difference in the change of the AHI score between n.17 CPAP group 19.1 ± 11.4 vs n.20 control group 21.7 ± 10.1 (P = 0.474) |

Asthma control did not improve significantly despite taking at least a moderate dose of ICS. This therapy may not be effective in improving asthmatic symptoms in patients with concomitant asthma and OSA |

| CHILDREN | ||||||

| Ross K.R., 2012 [44] | Relationships Between Obesity, SDB, and Asthma Severity in Children | Prospective observational study, comparative study Baseline 108 (82%) asthmatic children (age 9.1 ± 3.4 years). Valutazione SDB: overnight finger pulse oximetry monitoring No SDB (n.76) età 9.3 ± 3.4 years SDB (n.32) età 8.7 ± 3.3 years Predicted FEV1 %: No SDB 98.7 ± 17.7 With SDB 90.9 ± 17.1 Associations between SDB, obesity and asthma severity at follow-up. |

Severe asthma: children using high dose ICS alone or in combination with other drugs Not severe asthma: low to moderate dose ICS |

Asthma Severity at 12-month follow-up: Mild/Mod (n.79) Severe (n.29) Asthmatic children with BMI z-score=2 and SDB had a +6.7-fold risk (OR 1.74; 95% C.I.: 25.55) of having severe asthma compared to those without SDB. Children with asthma, BMI z-score 0 and SDB did not have an increased risk (OR +1.40; CI 95% 0.31 - 6.42) of having severe asthma compared to those without SDB |

32 children (29.6%) with SDB Children with prevalent SDB (OR 4.85, 95% CI 1.94 - 12.10) in severe asthma (55.2%) vs mild/mod asthma (20.3%, p <0.01); Children with SDB had OR 5.02 (95% CI 1.88 -13.44) to have severe asthma at follow-up (12 months), after adjustment for BMI z-score (p=0.001) |

Children who are asthmatic, obese, and with SDB: Higher risk of having severe asthma than those without SDB. Asthmatic, normal-weight, and SDB children using high doses of ICS alone or in combination with other medications: There was no significant association between SDB and asthma severity |

| Conrad L.A., 2022 [45] | Associations Between Sleep, Obesity and Asthma in Urban Minority Children | Retrospective review of medical records 448 children with asthma (ages 10.2 ± 4.1 years) who performed PSG. Association between spirometry variables, BMI and PSG parameters, adjusting for asthma and anti-allergy medications. |

Inhaled steroids: Obese asthmatics n.214 (74.1%), Normal weight asthmatics n.125 (81.2%) (p=0.09). [Montelukast: asma obesa n.174 (60,2%) versus n.92 (59,7%), p=0,92] [Steroidi nasali: Asma obesi n.89 (30,8%) versus Asma normopeso n.44 (28,6%); p= 0,63] |

FEV1: Obese asthmatics 83.1 ± 16.5, Normal weight asthmatics 86.4 ± 18.7 (p=0.05) FEF25%–75%: Obese asthmatics 74.8 ± 26.5 Normal weight asthmatics 76.8 ± 28.2 (p=0.4) |

289 obese asthmatics 5.9 ± 12.1 versus 154 normal-weight asthmatics 3.1 ± 5.7 (p=0.009) | In obese asthmatic children, both ICS and montelukast are associated with lower AHI. Neither ICS nor montelukast are associated with sleep respiratory parameters in children with asthma of normal weight. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).