1. Introduction

Support for a smooth transition from school to adulthood is one of the essential services for persons with disabilities. In the United States, transition support is already mandated as assistance for students receiving special education. If the core transition support plan within these services deviates from the needs of users with disabilities and is not implemented as concrete support, it may negatively impact outcomes such as users' employment and job retention [

1]. Additionally, collaboration among relevant organizations is essential for the success of transition support from special education to employment [

2,

3] as this collaboration enhances the achievement of students' post-graduate goals [

4,

5].

In recent years, momentum for promoting the transition from special education to society has been increasing in Japan. In Japan, employment promotion for persons with disabilities is driven by the employment quota system. Legal amendments have been made to promote social participation for persons with disabilities. The employment quota for companies, which was 2.3% in 2023, is set to increase to 2.5% in 2024 and 2.7% in 2026 [

6]. The employment rate of persons with disabilities in companies is increasing year by year [

7]. Special education schools in Japan play a central role in supporting the transition of people with disabilities. The competitive employment rate for graduates with intellectual disabilities from special education schools in 2022 was 33.4% [

8] – this employment rate is increasing annually. Against this background, there is growing recognition of the importance of transition support from special education to society at large.

While recognition of the importance of transition support is increasing, there is a current situation in which transition support does not function adequately. According to a survey by the National Institute of Special Needs Education, a national research institution for special education in Japan, the content of transition support by special education schools and vocational rehabilitation institutions is limited to simple advice such as "cooperation in workplace development" and "advice on career guidance and vocational education" [

9]. Additionally, special education teachers have pointed out the need to make the collaboration between special education teachers and vocational rehabilitation practitioners more functional [

10]. To make transition support function effective, it is necessary to promote collaboration among supporters [

11], and it is also deemed necessary to advance the establishment of systems and environments for this purpose [

12]. In Japan, a new support service called Employment Choice Support, which supports the self-determination of persons with disabilities, is in its infancy, and transitional support is expected to become increasingly important [

13]. Collaboration through transition support not only enhances transition support services, but also has the potential to improve the quality of local employment support [

14].

One of the background factors for the collaboration issues associated with such transition support is the perception gap between special education and vocational rehabilitation, which are different fields involved in transition support. Previous studies have reported the necessity of special training for teachers who tend to focus on "what students cannot do" rather than their potential [

15], and that the number of years of experience and knowledge of vocational rehabilitation has a positive impact on the execution of vocational education by teachers [

16,

17]. Additionally, there have been reports regarding the failure of collaboration in transition support due to differences in expertise between special education teachers and vocational rehabilitation practitioners [

18,

19,

20,

21]. These studies are useful to clarify the perception gap between special education teachers and vocational rehabilitation practitioners involved in transition support and propose measures to bridge this gap.

As described above, Japan currently experiences a demand for improved support for the transition from school to society in Japan. To achieve this improvement, it is necessary to bridge the perception gap between special education teachers and vocational rehabilitation practitioners involved in transition support. Therefore, this study aims to elucidate the perception gap regarding the content of instruction between special education teachers and vocational rehabilitation practitioners involved in transition support.

2. Methods

2.1. Methodology

Based on the research objective, this study compared perceptions of the importance of support for acquiring skills that constitute vocational readiness between vocational rehabilitation practitioners (Survey 1) and special education schoolteachers (Survey 2) during and after enrollment in special education schools.

2.2. Survey 1

2.2.1. Participants

The participants were vocational support providers from all 337 Employment and Life Support Centers for persons with disabilities (ELSCs), which are vocational rehabilitation institutions in Japan.

2.2.2. Procedure

During the period from November 1 to November 30, 2023, request letters were sent by mail to all 337 ELSCs for persons with disabilities, inviting them to respond to an online survey.

2.3. Survey 2

2.3.1. Participants

The participants were 538 teachers from 10 special education schools for students with intellectual disabilities in Prefecture X, a rural area of Japan.

2.3.2. Procedure

From October 21 to November 17, 2023, an email was sent to 10 special education schools requesting responses to an online survey.

2.4. Survey Items

2.4.1. Basic Attributes

Participants were asked to provide their gender (male, female, other), age as of March 31, 2024, years of experience in support/education, and their highest level of education (middle school, high school, vocational school, junior college, university, graduate school (master's), graduate school (doctorate)).

2.4.2. Skills Constituting Vocational Readiness

In this study, we use the concept of "vocational readiness," which comprises skills recognized as important for acquisition in transition support in Japan. Vocational readiness is defined as "various personal abilities necessary for vocational life" [

22,

23]. It is expressed in the form of a five-layer pyramid, which includes, in order from the top, vocational aptitude (VA) (Layer 1), basic work habits (BH) (Layer 2), interpersonal skills (IS) (Layer 3), daily living management (DM) (Layer 4), and health management (HM) (Layer 5). In Japanese vocational rehabilitation, assessment, training, and support are often provided with reference to this concept. For many vocational rehabilitation practitioners in Japan, this is the most representative guiding concept for transitional support. This vocational readiness concept is always taught in fundamental national training for employment support providers, such as the "Basic Training for Employment Support," the "Job Coach Training," which is a certification training for supported employment in Japan, and the "Vocational Counselor Training," equivalent to rehabilitation counselors prescribed by Japanese law.

The pyramidal shape of vocational readiness represents the stages of skill acquisition, meaning that if lower-layer skills are not sufficiently mastered, vocational aptitude skills in the upper layers cannot be fully utilized in the workplace. This is a practically useful concept that provides a perspective on support and training, even for supporters with little knowledge of employment support. Each layer incorporates several skills. Vocational aptitude includes suitability for tasks and the knowledge necessary for task execution. Basic work habits include greetings, responses, reporting, communication, consulting, grooming, adherence to rules, and physical work endurance. Interpersonal skills include emotional control, apologizing when corrected, and greeting those with whom one is uncomfortable. Daily living management includes basic life rhythms, money management, leisure activities, and mobility skills. Health management includes dietary, nutritional, physical condition, and medication management.

In this study, an original survey consisting of 25 items, with five items from each layer of vocational readiness, was created (

Table 1). Participants were asked to rate the importance of each of the 25 items during and after enrollment, using a 5-point Likert scale: 1 = not important, 2 = not very important, 3 = neutral, 4 = somewhat important, and 5 = important.

2.5. Data Analysis

Basic information was tabulated. For the skills constituting vocational readiness, the mean scores for each of the five layers were calculated and Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was computed to evaluate the internal consistency of these scores. To examine whether the scores of each layer of vocational readiness before and after graduation differed by affiliation (ELSCs or special education schools), a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted, with the within-subject factor being the period (before and after graduation) and the between-subject factor being affiliation.

2.6. Research Ethics

For the survey, an explanation regarding the protection of personal information was provided on the front page of the questionnaire, and consent was obtained from the respondents' who completed the survey. Additionally, approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee for Research Involving Human Subjects at Akita University’s Tegata Campus (Approval No. 5-37, dated October 11, 2023).

3. Results

3.1. Basic Attribution

The survey targeted 337 ELSC in Japan. Responses were obtained from 126 ELSC employment-support providers, representing a response rate of 37.4%. The survey targeted 538 teachers from special education schools, 129 of whom responded, being a response rate of 24.0%. These respondents' basic information is presented in

Table 2.

3.2. Perception of Skills for Vocational Readiness

3.2.1. Average Importance of Skills for Vocational Readiness

The average importance of the five layers of skills for vocational readiness as perceived by employment support providers at ELSCs and teachers at special education schools during and after enrollment is shown in

Table 3.

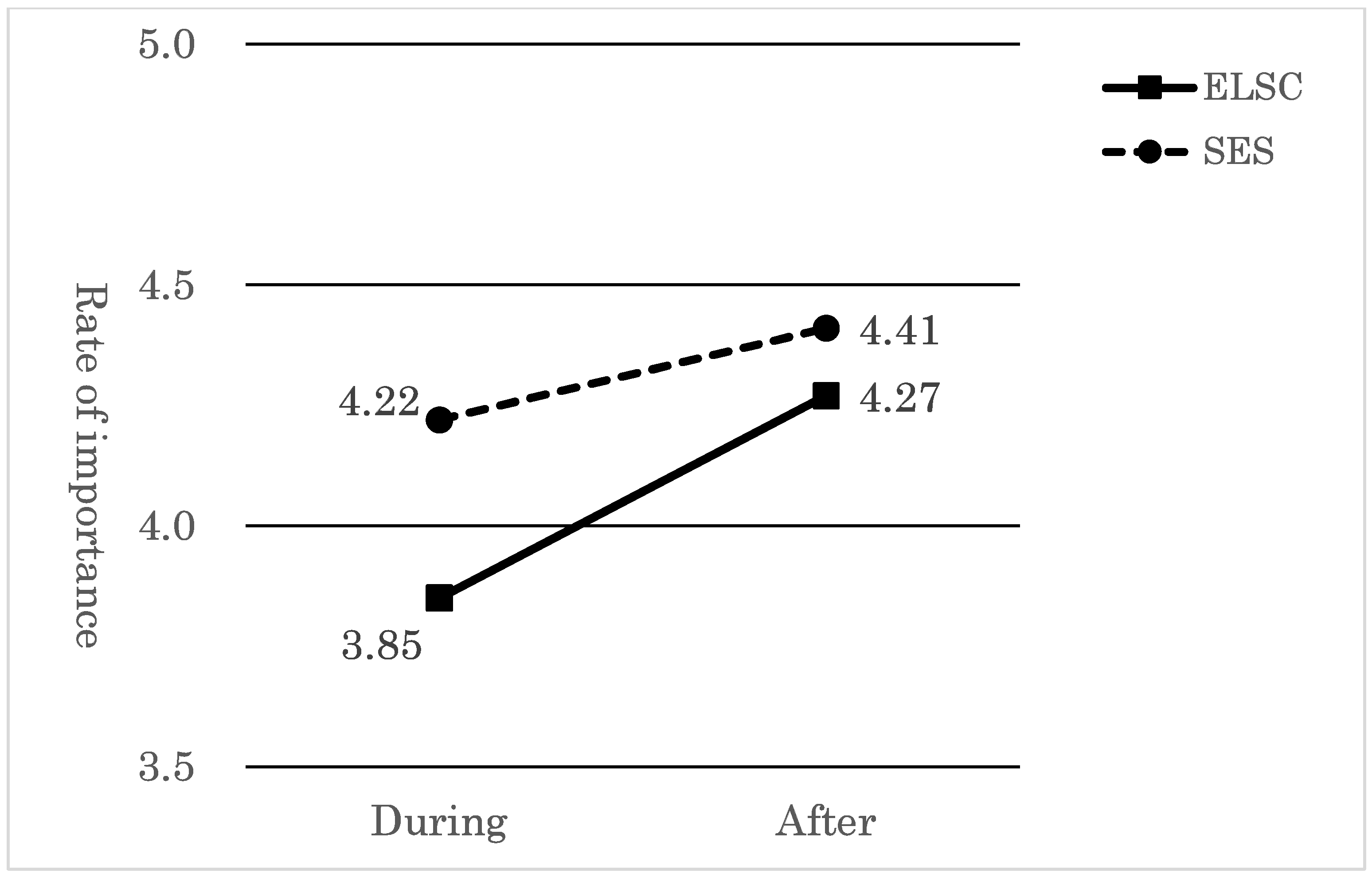

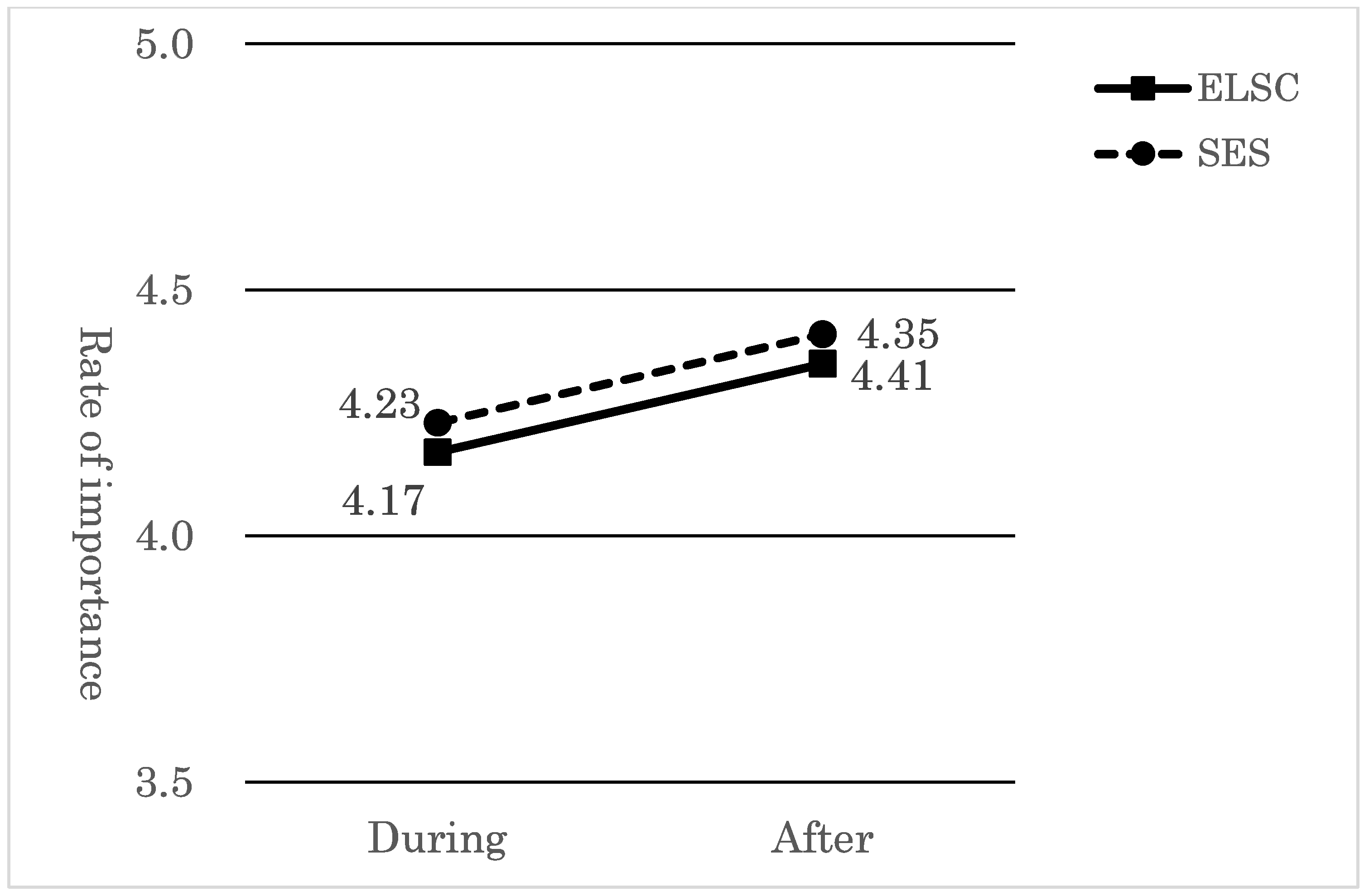

3.2.2. Perception of Vocational Aptitude

To examine whether the importance of support for vocational aptitude changed during and after enrollment based on the institution, a two-way ANOVA was conducted, with the within-subject factor being the time period (during and after enrollment) and the between-subject factor being the institution. As reflected in

Table 4, an interaction effect was observed (

F(1,253) = 12.55,

p < .01). The results of multiple comparisons indicated that importance was significantly higher for SES, and for both institutions, importance was significantly higher after enrollment (

Figure 1).

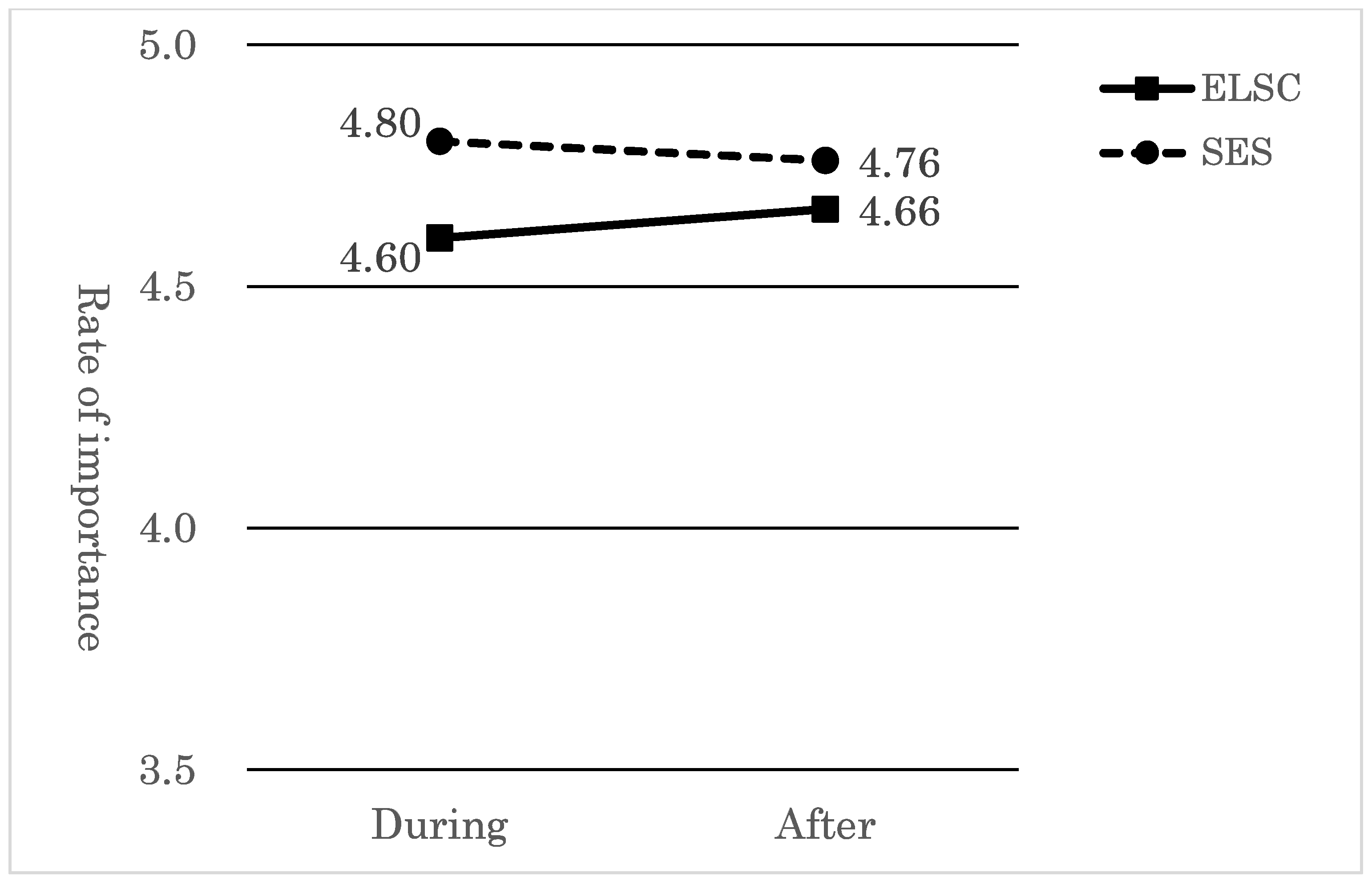

3.2.3. Perception of Basic Work Habits

To examine whether the importance of support for work habits changed during and after enrollment based on the institution, a two-way ANOVA was conducted, with the within-subject factor being the time period (during and after enrollment) and the between-subject factor being the institution. As demonstrated in

Table 5, an interaction effect was found (

F(1,253) = 4.87,

p < .05). The results of multiple comparisons indicated that importance was significantly higher in SES, and there was no significant difference during or after enrollment in either institution (

Figure 2).

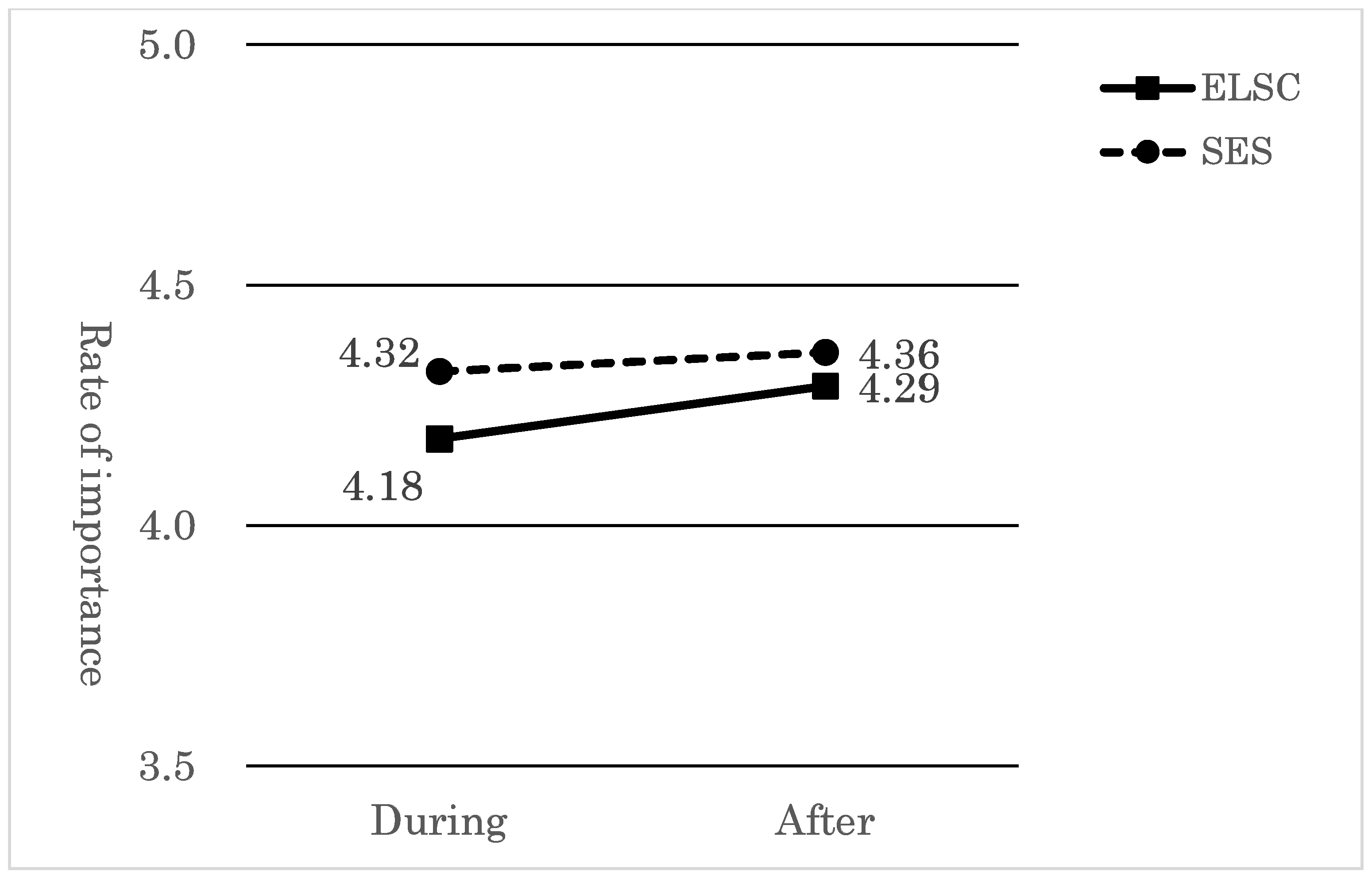

3.2.4. Perception of Interpersonal Skills

To examine whether the importance of support for interpersonal skills changed during and after enrollment based on the institution, a two-way ANOVA was conducted, the within-subject factor being the time period (during and after enrollment) and the between-subject factor being the institution. As depicted in

Table 6, there was a main effect of the time period (

F(1,253) = 9.78,

p < .01), but no interaction effect was observed (

F(1,253) = 2.32, n.s.) (

Figure 3).

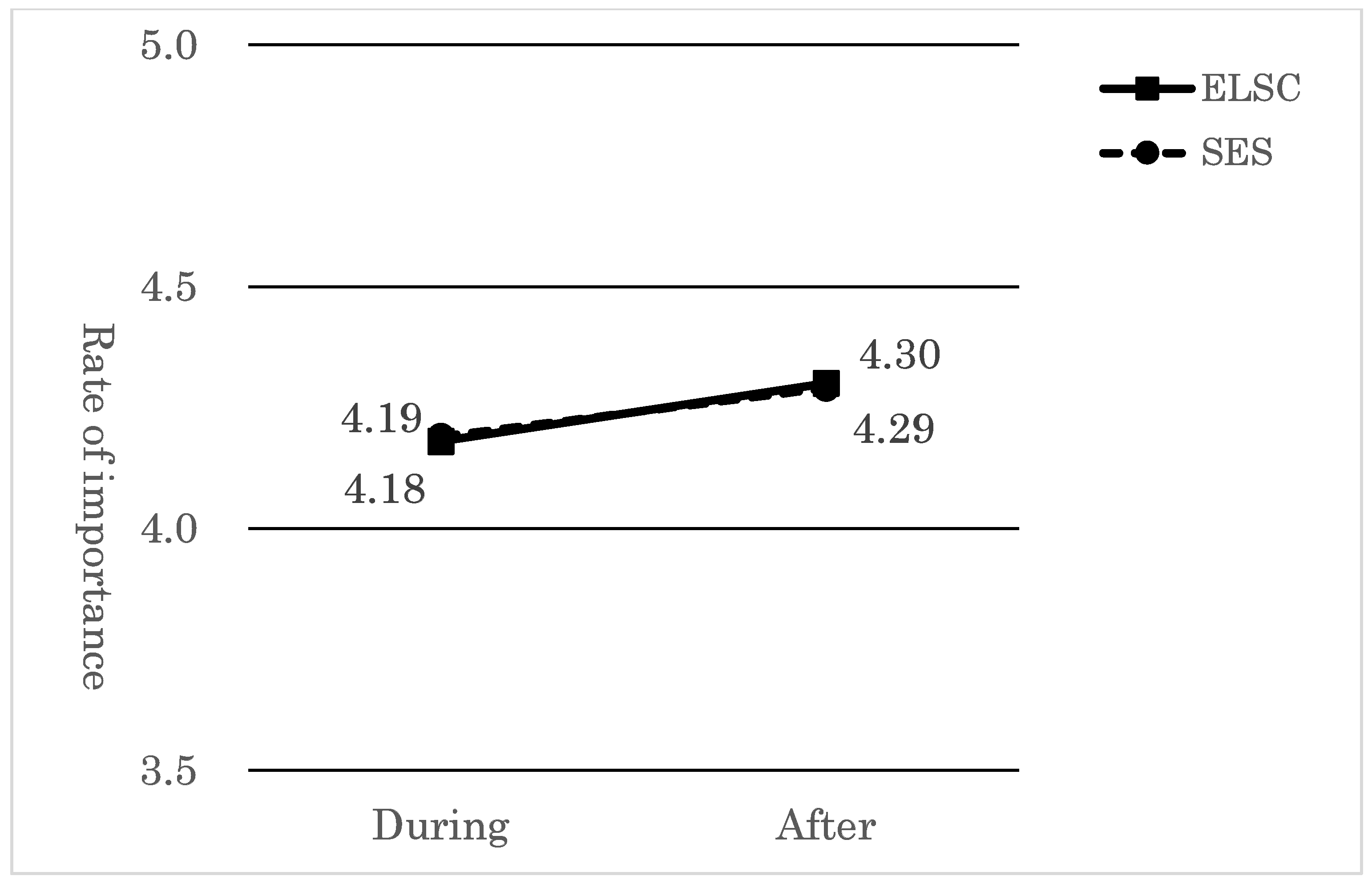

3.2.5. Perception of Daily Living Management

To examine whether the importance of support for daily living management changed during and after enrollment based on the institution, a two-way ANOVA was conducted, with the within-subject factor being the time period (during and after enrollment) and the between-subject factor being the institution. As shown in

Table 7, there was a main effect of the time period (

F(1,253) = 15.74,

p < .01), but no interaction effect was observed (

F(1,253) = 0.16, n.s.) (

Figure 4).

3.2.6. Perception of Health Management

To examine whether the importance of support for health management changed during and after enrollment based on the institution, a two-way ANOVA was conducted, the within-subject factor being the time period (during and after enrollment) and the between-subject factor being the institution. As illustrated in

Table 8, there was a main effect of the period (

F(1,253) = 4.93,

p < .01), but no interaction effect was found (

F(1,253)=0.01, n.s.) (

Figure 5).

4. Discussion

This study elucidated the gap in perceptions regarding the skills deemed necessary for employment between vocational rehabilitation providers and special education teachers. To this end, a two-way analysis of variance was conducted to evaluate whether the importance of support varied during and after enrollment based on institution, using the five-layered vocational readiness skills as items. The results confirmed a perception gap in the first layer, vocational aptitude. This gap indicated that special education teachers recognized the importance of training skills related to vocational aptitude, irrespective of the period during or after enrollment, more highly than vocational rehabilitation providers. A similar perception gap was observed in the second layer, basic work habits. This gap highlighted that special education teachers recognized the necessity of training basic work habits skills more during the period of schooling. In contrast, no perception gaps were observed in the third layer, interpersonal skills, the fourth layer, daily living management, and the fifth layer, health management. Moreover, it was noted that special education teachers acknowledged the importance of teaching work habits skills more during than after enrollment, while the perception of the importance of instruction after enrollment was higher for other skills.

Currently, the job coach system based on the concept of supported employment is widespread in Japan, serving as a core service for promoting the employment of persons with disabilities [

24]. The results of this study, indicating that most items of vocational readiness were recognized as important for after-enrollment training, reflect the perception of on-the-job training provided by job coaches. The concept of on-the-job training, which pursues interaction and potential with the environment, has significantly contributed to the development of the current vocational rehabilitation system in Japan. However, there are instances where support based on a biased concept of on-the-job training leads to issues within the workplace after employment, often reported as challenges in transitional support [

25]. Initial transitional support in the early stages of career planning for persons with disabilities is beneficial, enhancing the quality of employment through the provision of training and services [

26,

27,

28]. These studies suggest that not only improving the quality of support represented by after-enrollment supported employment is essential but also enhancing the quality of support during enrollment. Special education is considered to play a significant role in improving the quality of this support during enrollment.

In Japan, the training programs for employment support practitioners implemented by the government invariably include education on vocational readiness [

29]. Consequently, many vocational rehabilitation providers consider on-the-job training of hard skills, which are specific skills required by the workplace, as a fundamental approach. On the other hand, Japanese practitioners recognize the usefulness of preemptively training and supporting the acquisition of soft skills, other than vocational aptitude, which facilitate smooth transitions to the workplace before employment.

The results of this study indicated the existence of a perception gap between special education teachers and vocational rehabilitation providers. Firstly, a perception gap regarding the guidance of vocational aptitude in the first layer was confirmed. The results of this study showed that special education teachers recognized the importance of training vocational aptitude during enrollment. In Japan, an educational practice called "work learning" is conducted within special education schools. Generally, reports on the practice of this work learning tend to focus on the novelty or uniqueness of training methods for acquiring hard skills [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34]. From the perspective of transitional support, it is necessary to shift the focus from training hard skills to emphasizing the assessment of students through education and the acquisition of soft skills for employment after graduation [

35]. Secondly, an unexpected result in this study was the perception gap concerning the training of basic work habits in the second layer. It was predicted that the importance of after-enrollment training would be recognized for basic work habits, similar to other items. However, special education teachers recognized the importance of training basic work habits during enrollment. In Japan, workplace cooperation is highly valued. For the continued employment of individuals with intellectual disabilities, communication skills and cooperation, included in the basic work habits items, are considered necessary [

36,

37,

38]. Given this cultural perception, it was thought that the training of basic work habits during enrollment was deemed important.

5. Conclusion

The results of this study highlight critical points for the improvement of transitional support in Japan. It suggests that the failure in transitional support may not be due to system deficiencies but rather due to the perception gaps among the supporters involved in transitional support. Therefore, it is essential for supporters in transitional support to collaborate with an awareness of these gaps. Moving forward, it is necessary for supporters involved in transitional support to place students with disabilities at the center of their support, working together and communicating with the awareness of these gaps. Furthermore, the results of this study indicate that special education teachers should first learn about the concept of vocational readiness held by vocational rehabilitation providers and improve in-school career education based on this vocational rehabilitation perspective. Conversely, vocational rehabilitation providers should provide feedback to schools regarding educational outcomes, such as post-employment situations obtained from employment support. Such mutual communication is believed to enhance transitional support.

There are limitations to the data from special education teachers, which is the data source of this study. The teachers targeted in this study were from special education schools in a single prefecture in a rural area of Japan. Rural areas in Japan have limited opportunities to obtain information on vocational rehabilitation compared to urban areas. Therefore, it is necessary to consider the limitations of the data as representative of Japanese teachers. In the future, it is believed that more detailed data for the improvement of transitional support can be obtained by conducting surveys nationwide in Japan, taking into account external variables such as rural and urban areas. Additionally, in this survey, vocational readiness, which is prevalent in vocational rehabilitation, was used as the item for comparison. However, it is also necessary to investigate the content that schools focus on, which is not included in this vocational readiness. In recent special education, education on leisure guidance, lifelong learning, and information and communication technology is being conducted. It is considered beneficial to examine whether there are perception gaps in these areas as well in transitional support.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.M. and A.Y.; methodology, K.M.; validation, K.M.; investigation, K.M. and A.Y.; resources, K.M.; data curation, K.M.; writing—original draft preparation, K.M.; writing—review and editing, K.M.; visualization, K.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (Comprehensive Research on Disability Policy) from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (Grant Number: 23GC1001) for the development of a manual to improve the quality of employment support for persons with disabilities.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Human Research Ethics Committee of Akita University, Tegata District (Approval No. 5-37, October 11, 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

In the survey, explanations regarding the protection of personal information and other matters were provided on the front page of the questionnaire, and consent was obtained by the respondents' participation in the survey.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the special education teachers who supported this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Snell-Rood, C.; Ruble, L.; Kleinert, H.; McGrew, J.H.; Adams, M.; Rodgers, A.; Odom, J.; Wong, W.H.; Yu, Y. Stakeholder perspectives on transition planning, implementation, and outcomes for students with autism spectrum disorder. Autism 2020, 24(5), 1164–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, D.L.; Morgan, R.L.; Callow-Heusser, C.A. A survey of vocational rehabilitation counselors and special education teachers on collaboration in transition planning. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation 2016, 44(2), 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Povenmire-Kirk, T.C.; Test, D.W.; Flowers, C.P.; Diegelmann, K.M.; Bunch-Crump, K.; Kemp-Inman, A.; Goodnight, C.I. CIRCLES: Building an interagency network for transition planning. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation 2018, 49(1), 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehman, P.; Sima, A.P.; Ketchum, J.; West, M.D.; Chan, F.; Luecking, R. Predictors of successful transition from school to employment for youth with disabilities. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation 2015, 25(2), 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheef, A.R.; McKnight-Lizotte, M. Utilizing vocational rehabilitation to support post-school transition for students with learning disabilities. Intervention in School and Clinic 2022, 57(5), 316–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Regarding the strengthening of measures to increase the statutory employment rate of persons with disabilities [in Japanese]. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. 2023a. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/001064502.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2024).

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Summary of the employment situation of persons with disabilities [in Japanese]. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. 2023b. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/newpage_36946.html (accessed on 12 January 2024).

- Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology. Special education materials (fiscal year 2021) [in Japanese]. Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, 2022. Available online: https://www.mext.go.jp/a_menu/shotou/tokubetu/material/1406456_00010.html (accessed on 12 January 2024).

- National Institute of Special Needs Education. Development of career guidance and vocational education support programs in special needs schools (specialized departments) [in Japanese]. Research report 2012. National Institute of Special Needs Education.

- Yoshida, M.; Fujita, M.; Sekiguchi, T. Career guidance and support in special needs education (intellectual disabilities, autism) - A guide for homeroom teachers [in Japanese]. Zearth-Education-Shin-sha; Tokyo, Japan, 2008.

- Yaeda, J.; Shibata, J.; Umenaga, Y. Transition from school to work: The key to collaboration in rehabilitation services [in Japanese]. Japanese Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation 2000, 13, 32–39. [Google Scholar]

- Utsumi, J. Transition to new career guidance and "transition support" [in Japanese]. In Individual transition support that supports autonomy. Taiyo-Shobo; Tokyo, Japan, 2004; pp. 9–28.

- Suzuki, D.; Maebara, K. Current status and issues of transition support efforts for social participation of persons with disabilities: From the efforts of the Edogawa Ward Work Support Center for Persons with Disabilities [in Japanese]. Bulletin of the Center for Educational Research and Practice, Faculty of Education and Human Studies, Akita University 2021, 43, 89–95. [Google Scholar]

- Maebara, K. Case studies for multi-agency collaboration through assessment [in Japanese]. Research output of the 2023 Fiscal Year Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (21GC1009) from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. 2023. Available online: https://doi.org/10.20569/00006199 (accessed on 4 July 2023).

- Nota, L.; Soresi, S. Ideas and thoughts of Italian teachers on the professional future of persons with disability. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 2009, 53, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, R.; Dymond, S.K. Special education teachers' perceptions of benefits, barriers, and components of community-based vocational instruction. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities 2010, 48, 313–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imai, A.; Maebara, K.; Yaeda, J. Efforts and effectiveness in improving knowledge and skills of vocational assessment for teachers supporting career decisions of students with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability - Diagnosis and Treatment 2023, 11, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, A.; Ochiai, T. The survey of the knowledge and skills required for transition teachers in high school divisions of special needs education with intellectual disabilities: Based on the opinions of transition teachers in high school divisions of special needs education with intellectual disabilities [in Japanese]. Bulletin of the Graduate School of Education, Hiroshima University. Part. 1, Learning and curriculum development 2011, 60, 119–126. [Google Scholar]

- Fujii, A. The survey of the knowledge and skills required for transition specialists in high school divisions of special schools for students with intellectual disabilities: Based on the opinions of stuffs of employment and life support centers for individual with disabilities [in Japanese]. Bulletin of the Graduate School of Education, Hiroshima University. Part. 1, Learning and curriculum development 2011, 60, 127–133. [Google Scholar]

- Fujii, A.; Kawai, N.; Ochiai, T. The competencies required for transition specialists in high school divisions of special needs schools for students with intellectual disabilities: from the perspectives of vocational rehabilitation [in Japanese]. Japanese Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation 2013, 25, 2–13. [Google Scholar]

- Fujii, A. Interprofessional collaboration between special education and vocational rehabilitation [in Japanese]. Japanese Journal of Rehabilitation 2018, 173, 16–21. [Google Scholar]

- Matsui, N. Challenges in career education [in Japanese]. In Vocational Rehabilitation Studies, Revised 2nd Edition. Kyodo-Isho-Publishing; Tokyo, Japan, 2006; pp. 40–43.

- Matsui, N. Vocational readiness [in Japanese]. In Glossary of Terms in Vocational Rehabilitation. Yadokari-Publishing; Saitama, Japan, 2020; pp. 18–19.

- Ogawa, H. Handbook of job coach [in Japanese]. Empowerment Ken-Kyu-Jyo; Tokyo, Japan, 2012.

- Maebara, K. Case study on the employment of person with intellectual disability in childcare work in Japan. Journal of Intellectual Disability-Diagnosis and Treatment 2022, 10(3), 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, C. Demographic variables, vocational rehabilitation services, and employment outcomes for transition-age youth with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities 2018, 15, 226–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young Illies, M.; Valentini, B.J.; Ingles, K.E.; Gilson, C.B. An analysis of training and vocational rehabilitation services for individuals with intellectual disability. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation 2021, 55, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, A.; McKelvey, S.; Getzel, E.E.; Belluscio, T.; Parthemos, C. Perspectives on the implementation of pre-ETS services: Identification of barriers and facilitators to early career planning for youth with disabilities. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation 2023, 58, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japan Organization for Employment of the Elderly, Persons with Disabilities and Job Seekers (2024) Handbook of employment support [in japanese]. Japan Organization for Employment of the Elderly, Persons with Disabilities and Job Seekers; Chiba, Japan, 2024.

- Harada, K.; Azuma, N.; Sasaki, Z.; Shinagawa, M.; Kon, A.; Akuto, Y.; Fujiya, K. Developing classes to promote career development in special needs schools for students with intellectual disabilities: A case study of work learning in "the woodworking team" of a senior high school at special need school [in Japanese]. Bulletin of Educational Practice Research Papers 2021, 8, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obara, K.; Nakamura, M.; Kikuchi, M.; Hoshino, H.; Nakamura, K.; Fjiya, K.; Sasaki, N.; Azuma, N.; Sasaki, Z. Effectiveness of support in work learning at an upper secondary school for students with special needs with intellectual disabilities: A case study of a student in the "hand weaving team" [in Japanese]. Bulletin of Educational Practice Research Papers 2021, 8, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koeda, Y.; Katsukawa, K.; Uenosono, T. How to work with intellectual disability children on cotton cultivation and spinning [in Japanese]. Crossroads: Journal for Educational Research 2022, 26, 101–107, DOI: http://hdl.handle.net/10129/00007820. [Google Scholar]

- Oode, K.; Msai, T. A practical study on iPad utilization focusing on visual support methods in "work-learning": Investigation and implementation in a school for special needs for intellectual disabilities [in Japanese]. Special needs education research 2022, 44, 59–80. [Google Scholar]

- Kuroiwa, S.; Tsuji, K.; Sasaki, D.; Fukuda, C.; Sakuma, T.; Sakurai, K.; Hosokawa, K.; Kinoshita, R. Model lessons and teaching materials developed for agricultural group of high school work study of special needs education for intellectual disabilities [in Japanese]. Bulletin of the Faculty of Education, Chiba University 2024, 72, 127–138, DOI: https://opac.ll.chiba-u.jp/da/curator/900122364/. [Google Scholar]

- Nawaoka, K.; Maebara, K. A case report of improvement of career education using vocational rehabilitation techniques at special support school for children [in Japanese]. Bulletin of the Center for Educational Research and Practice, Faculty of Education and Human Studies, Akita University 2020, 42, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueoka, K. Abilities required for youth with mental retardation to get a job: Comparison of the attitudes of employers, teachers, and parents [in Japanese]. Japanese Journal of Special Education 1997, 34(4), 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, Y.; Yaeda, J.; Kikuchi, E. Factors indicating necessary support for job retention of individuals with intellectual disabilities [in Japanese]. Japanese Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation 2009, 22, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadaoka, K. A Study on the support of retention in the workplace for the graduates of upper secondary department of special needs education school for the students with intellectual disabilities: Appropriate vocational education from the view point of the support of retention in the workplace [in Japanese]. Bulletin of the National Institute of Special Needs Education 2017, 44, 13–26. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).