1. Introduction

REDD+, which refers to a process for reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation, and foster conservation, sustainable management of forests, and enhancement of forest carbon stocks, has gained a global reputation since its introduction in 2007 [

1]. Agreed upon by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), REDD+ constitutes an international voluntary mechanism for funding the mitigation of climate change. The aim of the REDD+ program is to strengthen the value of existing forests by providing economic incentives to developing countries in order to deal with forest-related activities that contribute to carbon dioxide (CO

2) emissions in the atmosphere and accelerate climate change. REDD+ is a cost-effective mechanism for combating climate change and improving the livelihoods of forest communities [

2].

Since the inception of REDD+, many developing countries have expressed interest and have been undergoing the various phases of REDD+, including preparation, implementation, and results-based payment. Developing economies like Ghana and Mozambique have been paid from the World Bank’s Carbon Fund for reduced CO

2 emissions [

3]. Ghana received

$4.8 million for achieving 972,456 tonnes of CO

2 emission reductions [

4]. Despite the positives of REDD+, some scholars have argued that it could be detrimental to forest-dependent communities [

5.

6]. Poudyal et al. [

6] observed that households were negatively affected by the REDD+ project in Madagascar and were also not compensated due to poor information on local communities and the challenge of rural households accessing information. Derkyi et al. [

5] found that the livelihoods of people in the Tano Offin Forest Reserve Area in Ghana might be negatively affected due to Forest Law Enforcement, Governance, and Trade Voluntary Partnership Agreement and REDD+, and thus advocate for social safeguards to be considered when implementing forest governance initiatives. Visseren-Hamakers et al. [

7] expressed that REDD+ actions to halt agriculture, which causes deforestation, would affect rural livelihood and cause food insecurity. Based on these studies, it is essential to institute mechanisms to safeguard local communities from the effects of REDD+ implementation.

Safeguards are measures to prevent, minimize, or mitigate environmental and social impacts during REDD+ implementation. Safeguards have been integrated into the UNFCCC Warsaw Framework to enhance the benefits of REDD+ and protect host communities while reducing emissions. Developing countries implementing REDD+ are mandated to incorporate safeguards into their national REDD+ strategy in a manner consistent with UNFCCC rules (Decision 1/CP. 16). Implementing effective regulation enhances the legitimacy and effectiveness of REDD+ [

7].

Ghana has seen significant progress in the REDD+ process after joining the World Bank’s Forest Carbon Partnership Facility (FCPF) REDD+ Readiness Program in 2008 [

8,

9,

10]. The country has developed a national REDD+ strategy (NRS) in line with the Warsaw Framework and other decisions of the Conference of the Parties of the UNFCCC for REDD+ implementation [

8]. The NRS describes various national and subnational REDD+ programs, such as the Cocoa-Forest REDD+ Program, Shea Savanna Woodland Program, and Policy and Legislative Reform Program, due to be implemented in Ghana to reduce CO

2 emissions and enhance forest carbon stocks while safeguarding forest-fringe communities. Among the various safeguard measures, we find forest plantation development (625,000 ha), enrichment planting of poorly stocked and degraded forest reserves (100,000 ha), implementation of agroforestry systems (3.75 million ha), and the creation of job opportunities and sustainable livelihoods in rural communities [

10].

Agroforestry is important in REDD+ implementation since it protects against forest-fringe communities losing their livelihood by allowing them to integrate tree and food crops into tree plantation establishments. Agroforestry projects help farmers to generate income and reduce poverty. In Ghana, farmers are provided with access to land to cultivate crops together with planted trees in the forest reserves, termed the Modified Taungya System. The MTS allows for the sharing of revenues derived from the extraction of mature trees, leading to a higher local community income and poverty alleviation in forest zones. As an agroforestry program, the MTS could improve Ghana’s forest cover and timber stocks [

11]. Nonetheless, there is limited information on the potential effects of safeguards on the living conditions of local communities in Ghana. This study thus assesses the relationship between safeguard measures and the living conditions of local communities in Ghana’s forest, savanna, and coastal ecological zones and whether safeguard measures specified in Ghana REDD+-related documents are aligned with the determinants of the living conditions of local communities.

This study addresses the following research questions:

What is the living condition of local communities in Ghana?

What is the association between safeguard measures described in the Ghana Living Standard Survey (GLSS) and the living condition of local communities in Ghana?

Are the safeguard measures described in documents related to Ghana’s REDD+ program aligned with the determinants of the living conditions of local communities in Ghana?

This study may help policymakers and actors of REDD+ in Ghana to design and implement safeguards equitably and in a way that is targeted to the needs of forest-fringe communities in different ecological zones. This study has the potential to teach REDD+ countries yet to develop safeguard mechanisms the importance of considering the living conditions of forest-fringe communities as a baseline and prerequisite for REDD+ implementation. Our analysis relies on the GLSS data collected by the Ghana Statistical Service over the years, which provides nationwide information on households’ living conditions and well-being. We complement the survey data with analyses of publicly available documents on REDD+ safeguards from the Ghana Forestry Commission.

2. Conceptual Framework

Safeguards are essential for allowing developing countries to mitigate social and environmental impacts on local communities during REDD+ implementation. These safeguards should be suitable and equitable in order to improve the livelihoods of vulnerable groups such as women, youth, local communities, indigenous, poor, and disabled persons in the forest zones rather than benefit economically better-off households. Andersson et al. [

11] argued that well-to-do families could, unlike poor households, enhance their productivity with advanced technology and more labor using their income from forests. The affluent also monopolize external interventions and skew benefits to themselves at the expense of the poor [

12,

13]. Thus, safeguarding measures geared towards improving the living conditions of local communities and households should be fair and inclusive in order to reduce socioeconomic inequalities.

While there are various studies on safeguards in the literature, an assessment of their impact on living conditions is lacking. According to Arhin [

14], many existing studies have assessed the social and environmental principles of the safeguards through forest initiatives [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19], the different forms of safeguards used by various actors [

20], and the lessons from past efforts relevant for the application of safeguards [

21]. Arhin [

14] categorized safeguards into preventive, mitigative, promotive, and transformative. This study focuses on the latter group, which deals with strategies or actions to enhance social inclusion, improve rural livelihoods, reduce poverty, and ensure the equity of benefit-sharing arrangements for REDD+ in communities [

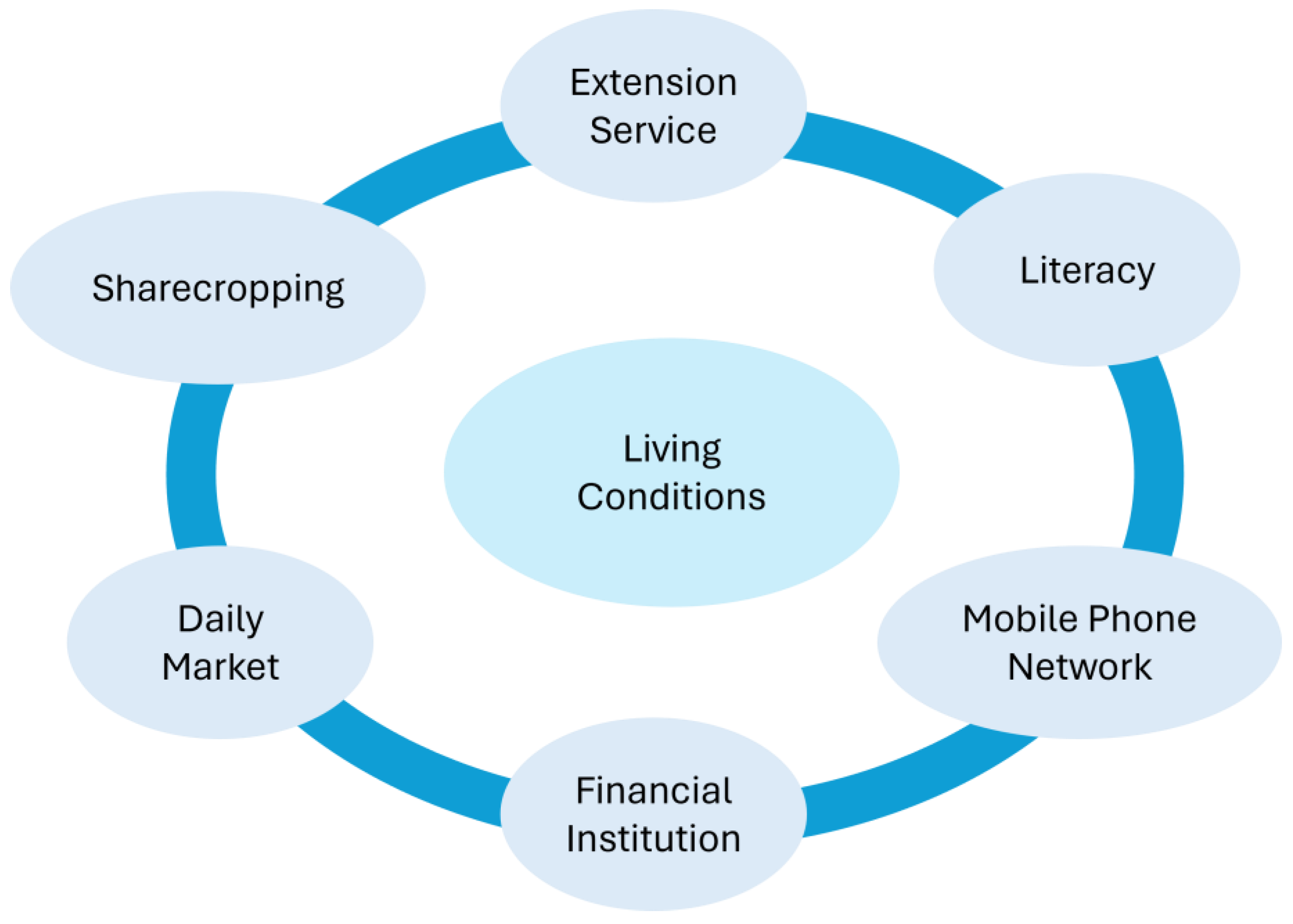

14]. We examine factors that can improve local communities’ living conditions to ensure effective REDD+ implementation in Ghana. We argue that local communities with sharecropping arrangements, access to extension services, a mobile phone network, a financial institution, and a daily or permanent market are positively influenced through REDD+ (

Figure 1). We define living conditions to include access to roads, access to electricity, access to transport, and migration.

3. Methods and Data Collection

We used the Ghana Living Standard Survey (GLSS) datasets to examine the living conditions of local communities and their relationships with some specified safeguards (Ghana Statistical Service, 2014, 2018). Seven periodic GLSS reviews have so far been conducted by the Ghana Statistical Service (GLSS 1, GLSS 2, GLSS 3, GLSS 4, GLSS 5, GLSS 6, and GLSS 7) since 1987 [

22]. The surveys provide information on Ghanaian households’ living conditions and poverty status by localities, regions, ecological zones, and occupational groups. Some studies have relied on the GLSS datasets to conduct their analysis. Novignon et al. [

23] used the GLSS 5 to estimate a household’s vulnerability to poverty and predicted that about 56% will be vulnerable to poverty in the future. Using the GLSS 7 dataset, Martey [

24] found that crop diversification relates to a 0.83 standard deviation decline in household energy poverty. These studies show the extent of the usage and reliability of the GLSS dataset. Our study relied on the GLSS 7 for our model estimation. The GLSS 7 covers 14,009 households, comprising 59,864 household members in 892 enumeration areas or communities across the original 10 regions of Ghana, now divided into 16. The data were collected using a stratified random sampling technique [

25]. The enumeration areas were stratified into regions, rural and urban residences, and ecological zones such as coastal, forest, and savanna.

In addition, we employed a qualitative content analysis of Ghana REDD+-related documents, using Atlas ti.9 to examine whether safeguard measures specified in these documents are aligned with the determinants of living conditions of local communities. In this instance, we included four documents collected online [

26] in our analysis. These documents include:

Ghana REDD+ Strategy (GRS), 2016;

Ghana Forest and Wildlife Policy (GFWP), 2012;

Ghana Benefit Sharing Mechanism (GBSM), 2014;

Ghana Forest Plantation Strategy (GFPS), 2016–2040.

The GRS was developed in accordance with the Warsaw REDD+ Framework and other rules of the United Nations Conference of the Parties. The GRS considers important national policies in the forestry sector and aims to reduce emissions from deforestation and forest degradation over the next 20 years. Additionally, it seeks to ensure the protection and sustainable management of forests. The GRS identifies the factors causing forest deforestation and degradation, including agricultural expansion, illegal logging, urbanization, and mining. It also identifies various innovative ways of solving these problems and improves rural livelihoods by providing economic and non-economic incentives and benefits.

The 2012 GFWP focuses on the conservation and sustainable development of forests and wildlife resources. The framework for forest policy includes Ghana’s common growth and development agenda, as well as international guidelines and conventions. The policy focuses on improving and maintaining the ecological integrity of Ghana’s forest areas, recovering and restoring damaged forest areas, developing viable forests and wildlife-based industries and livelihoods, and developing transparent governance, fair exchanges, and citizen participation in the management of forests and wildlife resources.

GBSM for REDD+ was developed in 2014 to address issues related to land and tree ownership, carbon rights and benefits sharing, i.e., concerns that are crucial to the implementation of REDD+ in Ghana [

27]. The report notes that three existing benefit-sharing mechanisms are suitable for use in REDD+, including community resource management area (CREMA), the MTS, and commercial private plantation income sharing (CPPRS).

The GFPS was developed in 2016 to deliver the sustainable utilization of forest resources for socio-economic and environmental benefits. Strategies include the development of forest plantations, the enrichment of degraded forest reserves, practicing agroforestry systems, and the provision of employment opportunities and sustainable livelihoods among rural communities. The GFPS seeks to incorporate food crops into forest plantations and to promote underground planting with alternative livelihood activities to provide additional short-term income to locals, thus improving livelihoods and increasing household incomes. The Ghana Forestry Commission projects that over 3 million jobs will be created during the 25-year strategic period 2016–2040 [

28].

After thoroughly reviewing the documents and attaining a better understanding of them, we searched for and categorized statements relating to the seven quantifiable and comparable Cancun safeguards and assessed their connection with the determinants of living conditions. The Cancun safeguards include: (A) national forest programs, international conventions, and agreements; (B) governance; (C) rights of indigenous peoples; (D) stakeholder participation; (E) natural forests and biodiversity; (F) risks of reversals; and (G) emission displacement. We qualitatively coded the safeguard measures (A–G) to distinguish levels of commitment through an iterative process [

29,

30].

Model Estimation Strategy

Our study establishes the relationship between safeguard measures and living conditions by estimating the following model:

where

represents the living conditions (measured as an index consisting of access to motorable roads, electricity, number of community members migrating out, and access to transportation services) in community

,

indicates the safeguard measures (adult literacy, women’s average wage, crop cultivated twice, and extension access),

is a vector of community characteristics and other relevant controls,

is the agroecological zone of the community, and

is the stochastic error term. The data and description on these variables are defined in

Table 1. The parameter of interest,

, measures the effect of safeguard measures on living conditions. We hypothesize that communities that employ safeguard measures record improved living conditions.

This study uses three different measures for living conditions. First, principal component analysis (PCA) is used to construct an index (continuous measure) where a higher index score indicates better living conditions and vice versa. The second construct of living conditions is based on count data (the number of living conditions). The PCA creates uncorrelated indices or components, where each component is a linear weighted combination of the initial indicator variables [

31]. The components indicate the different dimensions in the data due to their uncorrelated nature. According to Filmer and Pritchett [

32], the components are ordered such that the first component describes the largest possible variation common to all variables in the original data. In all the models, we controlled for average age, household size, the proportion of males, the proportion of elderly members, and the proportion of time-poor and economically active members of the community. Given the nature of the outcome variables (index and count), we employed three types of regression models, including Ordinary Least Squares (OLS), Poisson, and Negative binomial, in order to estimate the effect of safeguards on living conditions.

4. Results

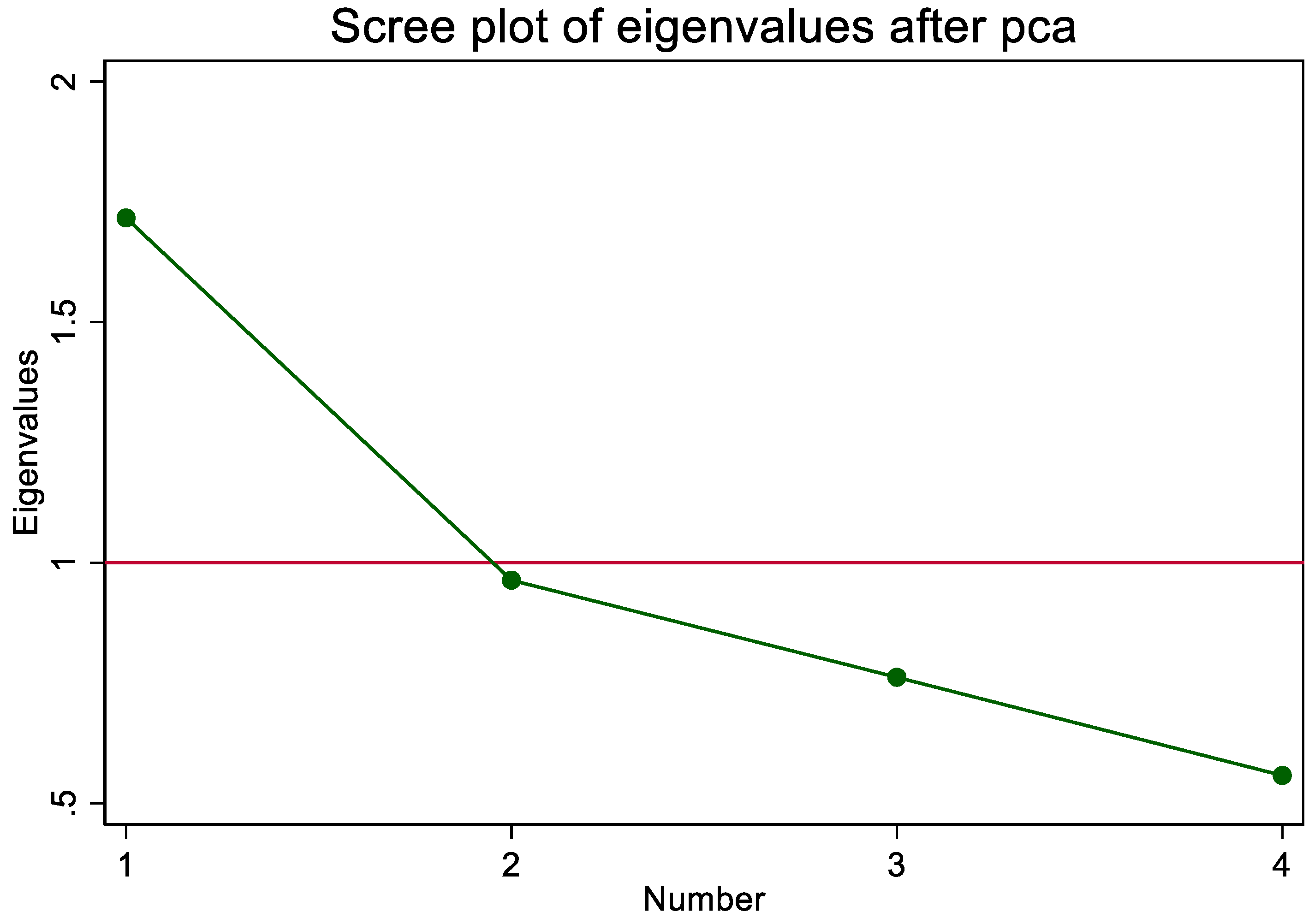

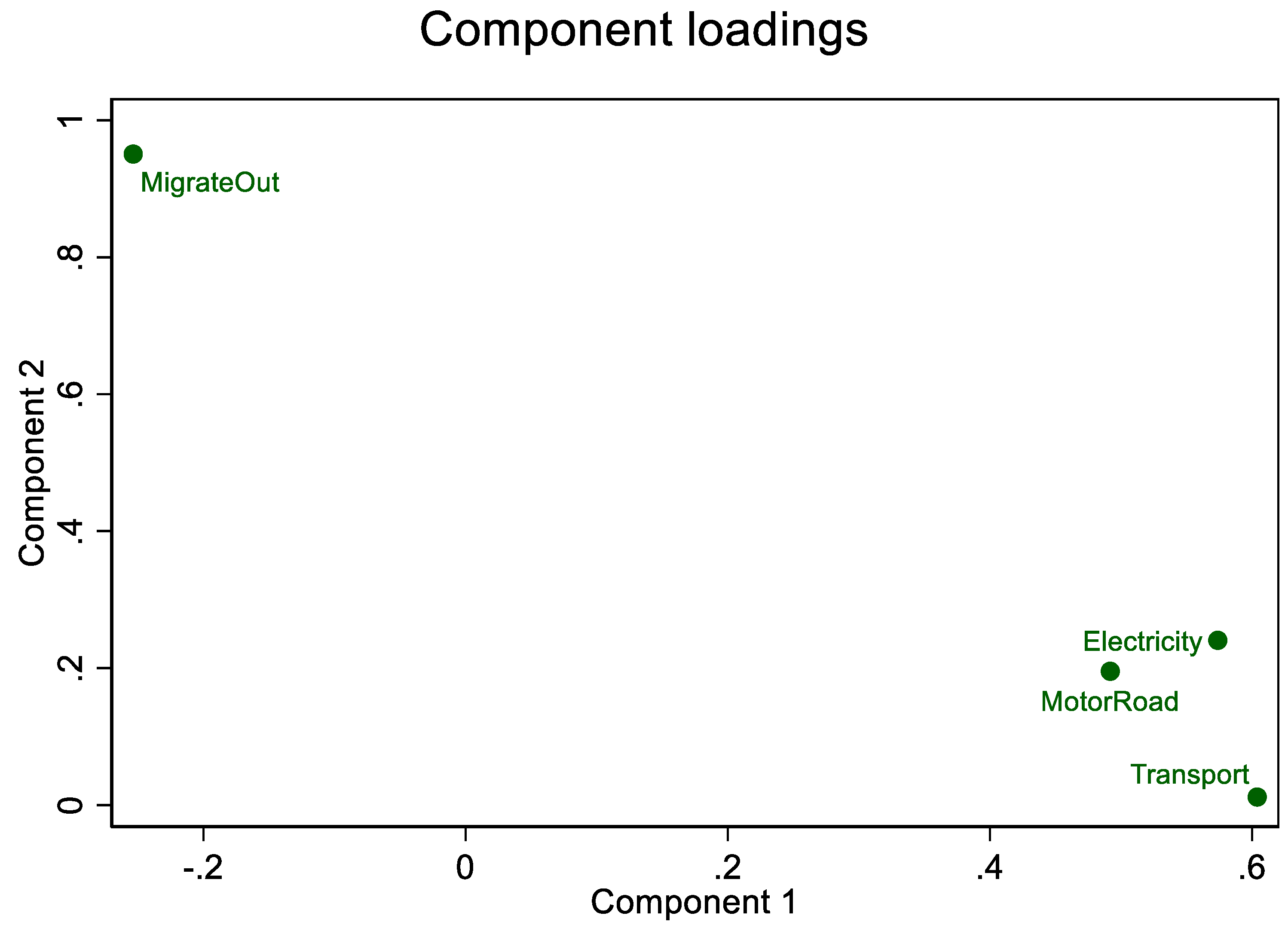

4.1. Packages of Standard of Living: Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

Figure 2 shows the plot of the eigenvalues against the number of components that should be included in the PCA. Four factors were considered in the PCA, whereas only one component was retained as the eigenvalue was greater than one. Two component loadings of the standard of living and their respective Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) values are reported in

Table 2. The estimated overall KMO measure was 0.6237, indicating the sampling adequacy of the PCA. Access to motorable roads and migration out contributed more than other variables in terms of the overall KMO. The result shows that zero variation in the indicators of the standard of living is unexplained by the retained components. Access to electricity, motorable roads, and transport services are highly loaded on component one, while migration out is highly loaded on component two (

Figure 3).

4.2. Relationship between Safeguard Measures and Living Conditions of Local Communities

Figure 4 provides an overview of the percentage distribution of living conditions in local communities in Ghana from 2012 to 2017. The GLSS 6, conducted in 2012/2013, used a 3-point Likert scale (better =1, worse = 2, and no change = 3) to measure the living conditions of the local communities, while in 2016/2017 the GLSS 7 used a 5-point Likert scale (better =1, slightly better = 2, worse = 3, slightly worse = 4, and no change = 5). Due to the difference in the measurement scale, we converted the 5-point Likert scale into a 3-point Likert scale to allow for comparison. We found that the living conditions of local communities vary from better to worse. According to the results, the 48.9% rate of local communities with better living conditions in 2012/2013 dropped to 32.7% in 2016/2017. Conversely, the percentage of local communities with worse living conditions increased from 44.3% in 2012/2013 to 57.2% in 2016/2017. We observed no significant change in the “no change” response in the two survey years.

Table 3 shows the results of the association between safeguard measures and living conditions. In the column (1), OLS model shows the effect of safeguard measures on the living condition index. Columns (2) and (3) show the effect of safeguard measures on the number of living conditions measured as count variables through Poisson model and Negative binomial model respectively. We found that men’s average wage is negatively associated with living conditions, decreasing living conditions within a significant level of 0.01. Conversely, women’s average wage is significant and positively associated with living conditions, increasing living conditions. However, the average women’s wage in a community improves the intensity of living conditions by a trivial rate (0.001), which implies that the impact of wage increase on living conditions is limited (0.01). The use of year-round multiple cropping and community tree planting increase the living conditions of the community members by 0.085 and 0.132 , respectively. However, tree planting and other crop cultivation reduce the intensity of living conditions by 0.131 and 0.161, respectively. The proportion of sharecroppers (standard deviation = 0.142), community members with extension access (standard deviation = 0.219), adult literacy (standard deviation = 0.187), and access to mobile phone networks (standard deviation = 0.525) are associated with increases in living conditions. Except for sharecroppers, community members with extension access (standard deviation = 0.101), adult literacy (standard deviation = 0.149), and access to mobile phone networks (standard deviation = 0.571) are positively associated with the intensity of living conditions. The proportion of community members that are financially included increases the intensity of good living conditions by 0.092. Additionally, the existence of a daily community market increases good living conditions and the intensity of good living conditions by 0.133 and 0.083 standard deviations, respectively.

Regarding socio-demographics, we find that the average age of a community member increases good living conditions and the intensity of good living conditions by 0.017 and 0.006 standard deviations, respectively, while average household size per community is associated with a decrease in good living conditions and the intensity of good living conditions by 0.048 and 0.052 standard deviations, respectively. The proportion of elderly members and males in a community is negatively associated with good living conditions, but the proportion of educated members of a community improves the living conditions and the intensity of living conditions by 0.079 and 0.040 standard deviations, respectively. The proportion of time-poor community members (members who spend more time in the labor market) improves living conditions by 0.118 standard deviations. Communities in savanna and forest agroecological zones are associated with a decline in living conditions and the intensity of living conditions compared to communities in the coastal agroecological zone.

4.3. Alignment of Safeguard Measures in Ghana REDD+ Policy Documents with the Determinants of Local Communities’ Living Conditions

Table 4 shows how safeguard measures described in the Ghana REDD+-related documents aligned with the determinants of living conditions of local communities in the three ecological zones. The safeguard measures described in the Ghana REDD+-related documents are consistent with the Cancun safeguards. We observed that 78% of the safeguards aligned with the determinants of the local communities’ living conditions, including sharecropping, extension access, literacy training, and daily community market. The safeguard measures aligned with education may limit the extent of deforestation and forest degradation in the forest fringe communities, ensure permanence, and avoid the risk of reversals of REDD+ policies. We observed that, of the safeguards aligned to the determinants of living conditions, most of them (43%) are related to sharecropping, while about 36% and 21% are aligned with extension access and education, respectively. The remaining safeguard measures show no alignment. We also observed that the MTS, the provision of off-reserve tree tenure security, the allocation of benefits accruing from resources and the provision of out-grower schemes, beekeeping, the cultivation of food crops, and the provision of livelihood systems for needy communities associated with significant sacred natural sites are aligned with sharecropping. Again, we observed that the decentralization of the forestry governance system to local levels, the dissemination of information on forestry events, the promotion of a multi-stakeholder dialogue approach towards decision making and feedback, transparency, the regular disclosure of information to stakeholder communities, the advancement of accountability, and the effective participation of women and local communities are aligned with the extension of access. Also, we observed that specialized training for processing bamboo, rubber wood, cane, and other NTFP species; the capacity building of communities including youth and women; and the provision of skill development and job creation are aligned with literacy training. These social safeguards, if implemented well, may enhance the living conditions of local communities in Ghana.

5. Discussion

In this study, we found that the living condition of local communities worsened from 2012 to 2017, indicating that most local communities lack basic amenities, with implications for the cost of implementing REDD+ in Ghana. Local communities that are potential beneficiaries of REDD+ need access to electricity, motorable roads, public transport, and other infrastructures to reduce costs associated with the REDD+ process and encourage progress. Furthermore, there is a need for the government to provide basic infrastructure in local communities, ensuring that the implementation of REDD+ is cost-effective due to reduced transaction costs. Transaction costs are expenditures from engaging stakeholders in the REDD+ process, including costs for negotiation, implementing strategies, monitoring actions and measurement, reporting, the verification of emission reductions , certification, and access to information [

33,

34].

Social infrastructures such as sharecropping, literacy, access to extension services, a mobile phone network, a financial institution, and a daily community market are likely to improve the living conditions of local communities and, thus, may aid the implementation of REDD+. This study also finds that safeguard measures described in Ghana’s REDD+-related documents align with living condition determinants and are likely to improve the living conditions of local communities. For example, the provision of specialized training for local communities in processing bamboo and other materials, capacity building for youth and women, skill development, and job creation aligned with literacy may improve the living conditions of local communities. The social safeguards here would reduce the over-reliance of local communities in forest zones on forest resources, an issue which tends to cause deforestation and carbon emissions. However, Hansen et al. [

35]suggested forest policy reforms to give landholders the right to manage and benefit from trees on farms and fallow lands rather than focusing on social safeguards. They argue that this will likely enhance rural livelihoods and curb illegal logging and the indiscriminate cutting down of trees in the country. We express that these social safeguards are critical and should not be ignored if Ghana wants to achieve results-based payment for REDD+. Therefore, forest policy reforms and social safeguards, used simultaneously, can help to achieve the ultimate goals of emission reduction and climate change mitigation.

5.1. Sharecropping

Sharecropping is one of the ways migrants and the landless poor can access fallow land to establish a cash or tree crop farm in the local communities of Ghana, especially those in forest zones, to improve their socioeconomic situation [

36,

37,

38,

39]. Sharecropping is a system whereby a tenant farmer shares the net proceeds from the harvest or shares the established plantation with the landowner, as per some sharing terms or agreements. In Ghana, the sharing terms under the sharecropping system are

abusa and

abunu which, in the Akan language of Ghana, mean dividing into three and two equal parts, respectively [

36].

Our findings revealed that sharecropping as a safeguard measure would likely improve the living conditions of local communities in the three eco-zones of Ghana. Giving room for more sharecropping systems in the local communities may enhance their living conditions and, thus, may reduce the risk associated with REDD+ implementation. Access to agricultural land and cultivated cash crops is a safeguard measure that may protect local communities from the potential harm of REDD+ and improve their livelihoods, thereby discouraging migration out of communities. Studies have shown that migration causes deforestation [

40]. Hoffmann et al. [

40] suggested, according to a local perspective in Columbia, that deforestation is also a result of waves of migration due to the displacement of communities. Darmawan et al. [

41] used both population census data and MODIS satellite image data and found that recent in-migration in Indonesia has had a significant positive relationship with deforestation. Ghana’s migrant population is growing in the local communities. Thus, in the wake of REDD+ activities in the High Forest Zone and Northern Savanna Zone, there is a need to safeguard these communities in terms of rights to access land or sharecropping arrangements to prevent the risk of reversals and emissions displacement in REDD+ implementation areas. However, there is also a need to regulate the distribution of benefits, costs, and tenancy reforms to prevent landowners from taking advantage of sharecropping tenants and avoid elite capture, which is in line with findings of Baah and Kidiko [

36], who asserted that the landowners’ profit share increase to 50% under the current

abunu system, unlike the 25% share they received under the traditional

abusa tenant system for tree crop plantations. This led to a decline in the percentage share of the sharecrop tenants from 67% to 50% under the current

abunu system [

36].

Furthermore, safeguard measures such as the MTS are aligned with sharecropping. The MTS is a form of agroforestry technique that allows farmers to access land to cultivate crops in the forest reserves in Ghana. Trees are integrated with crops until canopy closure, taking an average of 3 years [

42]. This study revealed that tree crop cultivation increases access to motorable roads and transport, while the cultivation of other crops increases access to motorable roads and decreases the proportion of community members migrating out of the community. The MTS allows for the sharing of revenues derived from the extraction of mature trees, leading to a higher local community income and poverty alleviation in the forest zones, with farmers receiving a 40% share of timber revenues for tree planting and maintenance. This safeguard measure may improve the living conditions of local communities and help to contribute to the effective implementation of REDD+. Blay et al. [

11] argue that the MTS has the potential to restore forest cover and timber stocks. Nonetheless, there is a need for input support such as firefighting tools, protective boots, cutlasses, raincoats, motorbikes, tricycles, fencing materials, boreholes, and access to credit in order to effectively and efficiently assist farmers in their farming activities and achieve REDD+.

5.2. Literacy

Literacy is considered an important factor in the improvement of living conditions in developing countries [44]. Generally, those who can read and write are said to accept and adopt new ways of doing things that can improve their standards of living. The results of this study show that adult literacy— indicating adults who can read and write in the local communities of Ghana—has a significant positive relationship with living conditions. This implies that providing more literacy training for adults in the local communities may enhance their standard of living and contribute to REDD+ implementation. The adult literate may appreciate and adopt various interventions under REDD+ aimed at improving their quality of life. The Cancun safeguards require that local communities’ and indigenous people’s rights are respected and protected, ensuring their full participation in and contribution to the REDD+ process. Thus, this can be effective and efficient if local communities have some level of literacy training. Yeang et al. [45] find that local communities participating in a REDD+ project in Cambodia prefer to use revenues from REDD+ for infrastructure development and literacy training. Literacy training is important because it builds the capacity of local communities, thus, facilitating discussions relating to REDD+. Further, it may prevent local communities from being sidelined because of the perception that they lack the technical knowledge and skills required to engage in REDD+ actions. Therefore, this study suggests that the safeguard measures observed should be aligned with training, such as the provision of specialized training for bamboo, rubber wood, cane, and NTFP species processing, the capacity building of communities including youth and women, and the provision of skill development and job creation.

5.3. Extension Access

Access to extension services is critical to the improvement of the living conditions of local communities. The study found that access to extension services by local communities may have a significant positive impact on their living conditions. This implies that, if local communities can transparently and regularly access information and participate effectively in decision making, their projects will be accountable and their living conditions may improve, which will likely positively affect the implementation of REDD+. For REDD+, access to information and the better interaction of local communities with implementing agencies are essential to achieving success. Therefore, this study argues that the use of safeguard measures by the government of Ghana to promote access to extension services and information helps to ensure effective and efficient REDD+ implementation. These measures include the decentralization of the forestry governance system to local levels, the dissemination of information on forestry events, the promotion of a multi-stakeholder dialogue approach for decision making and feedback, as well as transparency and regular disclosure of information to stakeholder communities.

6. Conclusions

REDD+ is an economic incentive mechanism for climate change mitigation agreed upon under the UNFCCC. REDD+ aims to reward developing countries that participate voluntarily with payments for reduced emissions from deforestation and forest degradation and increased carbon stocks. At COP 16 of the UNFCCC, held in Cancun, the parties agreed that REDD+ should address and respect a set of seven social and environmental safeguards. These safeguards must prevent or minimize negative environmental and social impacts during REDD+ implementation. For countries implementing REDD+ like Ghana, it is mandatory to develop a national REDD+ strategy that provides clear measures to address the drivers of deforestation and forest degradation and other related issues, including land and tree tenure, forest governance, benefit sharing, mainstreaming gender, MRV (monitoring, reporting and verification), and safeguards. This study paid attention to social safeguard measures developed for advancing REDD+ in Ghana. The study examined whether these safeguard measures aligned with the determinants of living conditions of local communities in the forest, savanna, and coastal zones of Ghana. The study found that social safeguards described in Ghana’s REDD+-related documents including GRS, GFWP, GBSM, and GFPS are aligned with the determinants of local communities’ living conditions. These safeguards include, among others, the MTS, the provision of off-reserve tree tenure security, the allocation of benefits accruing from resources, the provision of out-grower schemes, beekeeping, the cultivation of food crops, and the provision of livelihood systems for needy communities associated with significant sacred natural sites. These social safeguards, if implemented well, may enhance the living conditions of the local communities in Ghana and aid in REDD+ implementation and the sustainability of emission reduction projects. However, there is a need to enforce the benefit-sharing mechanisms and improve forest governance and tenancy reforms to prevent overexploitation by landowners and avoid elite capture. In addition, there is a need to link farmers to financial institutions in order to enable to access credit and provide local communities with the market and mobile phone networks necessary to carry out their livelihood activities effectively and efficiently, thus helping to sustain REDD+ actions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.A. and Y.L.; methodology, J.A.; formal analysis, J.A.; investigation, J.A.; resources, E.M., E.A.O., and K.A.O.; writing—original draft preparation, J.A.; writing—review and editing, Y.L.; visualization, J.A., Y.L; supervision, K.A.O. and Y.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Ghana Statistical Service for providing access to the GLSS dataset. The authors also express appreciation to anonymous reviewers for their time and insightful comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Available online: https://unfccc.int/topics/land-use/workstreams/reddplus (accessed on 7 December 2022).

- Hirata, Y.; Takao, G.; Sato, T.; Toriyama, J. (Eds.). REDD-Plus Cookbook; REDD Research and Development Center, Forestry and Forest Products Research Institute Japan: 2012. ISBN 978-4-905304-15-9.

- World Bank. In Ghana, Sustainable Cocoa-Forest Practices Yield Carbon Credits. Climate Stories: Ghana Carbon Credits. 2023. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2023/06/01/ (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- FCPF. Ghana Cocoa Forest REDD+ Program; Verification Report Version 1.3, July 2022; Scientific Certification Systems Global Services (SCS), 2000 Powell Street, Suite 600, Emeryville, CA 94608, USA.

- Derkyi, M.; Ros-Tonen, M.A.F.; Kyereh, B.; Dietz, T. Emerging Forest regimes and livelihoods in the Tano Offin Forest Reserve, Ghana: Implications for social safeguards. For. Policy Econ. 2013, 32, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudyal, M.; Ramamonjisoa, B.S.; Hockley, N.; Rakotonarivo, O.S.; Gibbons, J.M.; Mandimbiniaina, R.; Jones, J.P. Can REDD+ social safeguards reach the ‘right’ people? Lessons from Madagascar. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2016, 37, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visseren-Hamakers, I.J.; McDermott, C.; Vijge, M.J.; Cashore, B. Trade-offs, co-benefits and safeguards: Current debates on the breadth of REDD+. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2012, 4, 646–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andoh, J.; Lee, Y. National REDD+ strategy for climate change mitigation: A review and comparison of developing Countries. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andoh, J.; Oduro, K.A.; Park, J.; Lee, Y. Towards REDD+ implementation: Drivers of deforestation and forest degradation, REDD+ financing, and readiness activities in participant countries. Front. For. Glob. Chang. 2022, 5, e957550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forestry Commission of Ghana (FCG). Ghana National REDD+ Strategy. 2016. Available online: www.forestcarbonpartnership.org (accessed on 30 July 2018).

- Blay, D.; Appiah, M.; Damnyag, L.; Dwomoh, F.K.; Luukkanen, O.; Pappinen, A. Involving local farmers in rehabilitation of degraded tropical forests: Some lessons from Ghana. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2008, 10, 503–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, K.P.; Smith, S.M.; Alston, L.J.; Duchelle, A.E.; Mwangi, E.; Larson, A.M.; de Sassi, C.; Sills, E.O.; Sunderlin, W.D.; Wong, G.Y. Wealth and the distribution of benefits from tropical forests: Implications for REDD+. Land use policy 2018, 72, 510–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matson, P.; Clark, W.C.; Andersson, K. Pursuing Sustainability: A Guide to the Science and Practice; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Torpey-Saboe, N.; Andersson, K.; Mwangi, E.; Persha, L.; Salk, C.; Wright, G. Benefit sharing among local resource users: the role of property rights. World Development 2015, 72, 408–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arhin, A.A. Safeguards and dangerguards: A framework for unpacking the black box of safeguards for REDD+. For. Policy Econ. 2014, 45, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stickler, C.; Bezerra, T.; Nepstad, D. Global Rules for Sustainable Farming: A Comparison of Social and Environmental Safeguards for REDD+ and Principles & Criteria for Commodity Roundtables. The RT-REDD Consortium: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012; p. 14. [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie, C. REDD+ Social Safeguards and Standards Review; Forest Carbon, Markets, and Communities Program (FCMC), Tetra Tech: Burlington, VT, USA, 2012; pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Roe, S.; Streck, C.; Pritchard, L.; Costenbader, J. Safeguards in REDD+ and Forest Carbon Standards: A Review of Social, Environmental, and Procedural Concepts and Application. Climate Focus: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Merger, E.; Dutschke, M.; Verchot, L. Options for REDD+ voluntary certification to ensure net GHG benefits, poverty alleviation, sustainable management of forests, and biodiversity conservation. Forests 2011, 2, 550–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, N.; Nussbaum, R.; Muchemi, J.; Halverson, E. A Review of Three REDD+ Safeguard Initiatives; UN-REDD and FCPF: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- McDermott, C.L.; Coad, L.; Helfgott, A.; Schroeder, H. Operationalizing social safeguards in REDD+: Actors, interests, and ideas. Environ. Sci. Policy 2012, 21, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ros-Tonen, M.A.; Insaidoo, T.F.; Acheampong, E. Promising start, bleak outlook: The role of Ghana’s modified taungya system as a social safeguard in timber legality processes. For. Policy Econ. 2013, 32, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghana Statistical Service. Available online: www2.statsghana.gov.gh/nada (accessed on 22 January 2023).

- Novignon, J.; Nonvignon, J.; Mussa, R.; Chiwaula, L.S. Health and vulnerability to poverty in Ghana: Evidence from the Ghana Living Standards Survey Round 5. Health Econ. Rev. 2012, 2, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martey, E. Empirical analysis of crop diversification and energy poverty in Ghana. Energy Policy 2022, 165, 112952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghana Statistical Service. Ghana Living Standard Survey Round 7 Main Report; Ghana Statistical Service: Accra, Ghana, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Forestry Commission of Ghana (FCG). Available online: https://fcghana.org (accessed on 5 February 2022).

- Dumenu, W.K.; Samar, S.; Mensah, J.K.; Derkyi, M.; Oduro, K.A.; Pentsil, S.; Obeng, E.A. Benefit Sharing Mechanism for REDD+ Implementation in Ghana; Consultancy Report; Forestry Commission: Accra, Ghana, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Forestry Commission of Ghana (FCG). Ghana Forest Plantation Strategy. Forestry Commission of Ghana: Accra, Ghana, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mayring, P. Qualitative Content Analysis: Theoretical Foundation, Basic Procedures, and Software Solution; Open Access Repository: Klagenfurt, Austria, 2014; Available online: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-395173 (accessed on 2 December 2021).

- Carodenuto, S.; Buluran, M. The effect of supply chain position on zero deforestation commitments: Evidence from the cocoa industry. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2021, 23, 716–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D.S.; Twyman, C.; Osbahr, H.; Hewitson, B. Adaptation to climate change and variability: Farmer responses to intra-seasonal precipitation trends in South Africa. In African Climate and Climate Change; Williams, C.J.R., Kniveton, D.R., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 155–178. [Google Scholar]

- Filmer, D.; Pritchett, L.H. Estimating wealth effects without expenditure data—Or tears: An application to educational enrolments in states of India. Demography 2001, 38, 115–132. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Merger, E.; Held, C.; Tennigkeit, T.; Blomley, T. A bottom-up approach to estimating cost elements of REDD+ pilot projects in Tanzania. Carbon Balance Manag. 2012, 7, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deveny, A.; Nackoney, J.; Purvis, N.; Gusti, M.; Kopp, R.J.; Madeira, E.M.; Stevenson, A.R.; Kindermann, G.; Macauley, M.K.; Obersteiner, M. Forest Carbon Index; Resources for the Future: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, C.P.; Pouliot, M.; Marfo, E.; Obiri, B.D.; Treue, T. Forests, Timber and Rural Livelihoods: Implications for Social Safeguards in the Ghana-EU Voluntary Partnership Agreement. Small-Scale For. 2015, 15, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baah, K.; Kidido, J.K. Sharecropping arrangement in the contemporary agricultural economy of Ghana: A study of Techiman North District and Sefwi Wiawso Municipality, Ghana. J. Plan. Land Manag. 2020, 1, 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaye, W.; Ampadu, R.; Onuamah, J. Review of Existing Land Tenure Arrangements in Cocoa Growing Areas and Their Implications for the Cocoa Sector in Ghana; A Technical Report; 2014; Available online: https://www.academia.edu (accessed on 7 July 2022).

- Amanor, K.S.; Diderutuah, K.M. Share Contracts in the Oil Palm and Citrus Belt of Ghana; International Institute for Environment and Development: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kasanga, R.; Kotey, N.A. Land Management in Ghana: Building on Tradition and Modernity; International Institute for Environment and Development: London, UK; Russel Press: Nottingham, UK, 2001; pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, C.; Márquez, J.R.G.; Krueger, T. A local perspective on drivers and measures to slow deforestation in the Andean-Amazonian foothills of Colombia. Land Use Policy 2018, 77, 379–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darmawan, R.; Klasen, S.; & Nuryartono, N. Migration and deforestation in Indonesia (No. 19). Göttingen: GOEDOC, Dokumenten- und Publikationsserver der Georg-August-Universität, 2016.

- Agyeman, V.K.; Marfo, K.A.; Kasanga, K.R.; Danso, E.; Asare, A.B.; Yeboah, O.M.; Agyeman, F. Revising the taungya plantation system: New revenue-sharing proposals from Ghana. Unasylva 2003, 212, 40–43. [Google Scholar]

- Green, S.; Rich, T.; Nesman, E. Beyond individual literacy: The role of shared literacy for innovation in Guatemala. Hum. Organ. 1985, 44, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeang, D.; Eam, S.; Sherchan, K.; Mckerrow, L. Local community participation in biodiversity monitoring and its implication for REDD+: A case study of Changkran Roy Community Forest in Cambodia. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Environment and Rural Development, Phnom Penh, Cambodia, 16–17 January 2016.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).