1. Introduction

Background

Infantile haemangiomas (IH) represent childhood’s most common benign tumour, with a prevalence of 4-5% [

1]. Most of them spontaneously regress, but 10-15% of affected patients require systemic treatment with propranolol due to the risk of ulceration or permanent functional or cosmetic damage [

1]. Due to the risk of rare, major adverse events, such as hypotension, bradycardia, hypoglycaemia, or bronchospasm, repeated clinical evaluations in a hospital setting are provided [

1,

2]. Moreover, other widespread, minor adverse events, such as sleep disturbances, may increase the need for office visits, placing a considerably high managerial load on the family and potentially exposing children to nosocomial infections [

1,

2,

3]. Furthermore, monitoring patients for any adverse events related to treatment and supporting caregivers was reported as very difficult during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic [

4]. This has created a dramatic impetus towards innovative ways to remotely and effectively monitor patient health status.

2. Objectives

The study’s primary endpoint was to explore new methods of remote monitoring of the therapy, such as structured questionnaires aimed at the early identification of sleep disturbances as adverse events to treatment and any concomitant factors as potential confounding factors. The secondary endpoint of the study was to report the proportion of treated patients who present sleep disturbances as drug adverse reactions, i.e., adverse events which can be directly related to drug administration after the causality assessment process conducted by pharmacovigilance experts.

3. Materials and Methods

Design and Setting of the Study

This is an observational, prospective monocentric cohort study. The study was conducted in the Paediatric Unit of a tertiary-level hospital (University Hospital of Verona, Veneto Region, Italy) by physicians with expertise in Paediatrics and IH.

Study Population

Participants were enrolled during the first outpatient visit between 01/08/2019 and 01/08/2020. Written informed consent was obtained from the legal representatives of all participants. The local Ethical Committee approved the study (EI-TM Prog. 2792CESC- vers: 2, date of approval 15/07/2020).

All adverse drug reaction (ADR) reporting forms provided by patients on propranolol and their physicians were analysed by Veneto Region Pharmacovigilance Centre experts according to Naranjo’s algorithm [

5]. The deadline for data analysis was 31/01/2021.

All consecutive patients referred for IH were considered for recruitment. Inclusion criteria were as follows: age <2 years; diagnosed with a type of IH with an indication for systemic treatment with propranolol according to the International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies (ISSVA) criteria (i.e., life-threatening IH, severe functional impairment, ulcerated IH, permanent aesthetic impairment) [

1]. Exclusion criteria were as follows: patient weight <2000 g at recruitment, heart rate <80 bpm, non-invasive systemic blood pressure <50/30 mmHg, atrioventricular block 2°-3° degree, heart failure, phaeochromocytoma, propranolol drug allergy; poor Italian language competence of the patient’s caregivers; lack of electronic instruments such as smartphones or personal computers at the patient’s home.

Since this study was exploratory, the population size was set based on feasibility. According to the patient enrolment capacity in the study, approximately 30 patients were expected to be enrolled over 12 months. Considering a prevalence of sleep disorders of about 30% in the general paediatric population under the age of 24 months [

6], and 10% of cases on average (range 2%-20% according to studies) in subjects treated with propranolol for IH [

1], the 95% confidence interval for the percentage of detectable adverse events according to Fisher’s exact test probability formula is 1.6% - 18.3%.

4. Data Collection

Office Visits

Patients’ age, sex, IH phenotype, sleep habits, and complaints were recorded in medical records at recruitment and at each follow-up visit (every 8 weeks and at treatment suspension). Data on personal and family history of diseases and sleep disorders were collected. Children were diagnosed with sleep disturbances if there was a presence, for ≥5 nights/week, of prolonged time to fall asleep compared to the norm for age, and/or ≥3 awakenings/night, and/or prolonged night wakefulness compared to the norm for age, and/or total duration of sleep (day + night) reduced compared to the norm for age, and/or excessive daytime sleepiness and/or increased daytime irritability [

7].

Structured Electronic Questionnaire

The electronic interview for the survey is shown as

Supplementary Data. The questionnaire was developed in plain Italian. The first part included anamnestic data, information on pregnancy, the perinatal period, growth, nutrition, and sleep/awake rhythm. Moreover, information about IH, previous diseases, and family history for significant pathologies was collected. The second part consisted of a previously published sleep quality questionnaire about sleep habits (Brief Infant Sleep Questionnaire - BISQ - for evaluating sleep quality in infants) [

7].

Diagnostic criteria for the identification of sleep disturbances were previously reported. In order to accurately evaluate any adverse events reported by caregivers, information about any confounders was also investigated in the third section of the questionnaire, mainly non-drug-related factors possibly associated with sleep disorders, such as the order of birth, presence of chronic diseases, age in physiological “sleep regression” periods [

8], type of feeding, type of care (e.g., exclusive parental care; child communities; the presence of caregivers other than parents); sleep hygiene habits (e.g., co-sleeping, bed-sharing; stimuli in the bedroom; mode of falling asleep; mode of interaction with the child during awakenings; a first-degree family history of sleep disorders).

At recruitment, parents communicated their email addresses to IH-expert physicians involved in the study [FO, ER], to be contacted for the follow-up interview; moreover, they indicated their phone contact and the preferred time interval for any phone calls by FO and ER. The electronic form of the interview was sent by email, and caregivers were requested to complete data using a free software application (“Google Forms”), which also allowed automatic data export into an Excel file dataset (Office for Windows, version 365) after completion of the questionnaire—within 7 days of sending questionnaires, FO and ER contacted parents to detect any major adverse events or any difficulties in completing the interview. Any descriptive notes provided by responders in the electronic interview were used for dataset integration. In case of discordant opinions between two researchers (FO, RO) for the interpretation of notes, a third opinion was requested (ER).

The questionnaire was administered after 8 weeks of treatment and at treatment interruption.

Dataset Management

Clinicians involved in the study [FO, ER, RO] integrated information from patient’s medical records and information from the corresponding electronic questionnaires provided by caregivers. Then, the dataset was cleaned for duplicates and structural errors. No missing data were found. Finally, a person-level, anonymized data linkage was provided to researchers for data analysis.

Statistical Analysis

The Chi-square or Fisher exact probability tests, Student t-test, or U Mann-Whitney test were used as appropriate for categorical variables, quantitative variables with normal distribution, and quantitative variables without normal distribution. The significance threshold was set at p<0.05 for all analyses in the study. Data analysis was performed using SPSS 22.0 version for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

5. Results

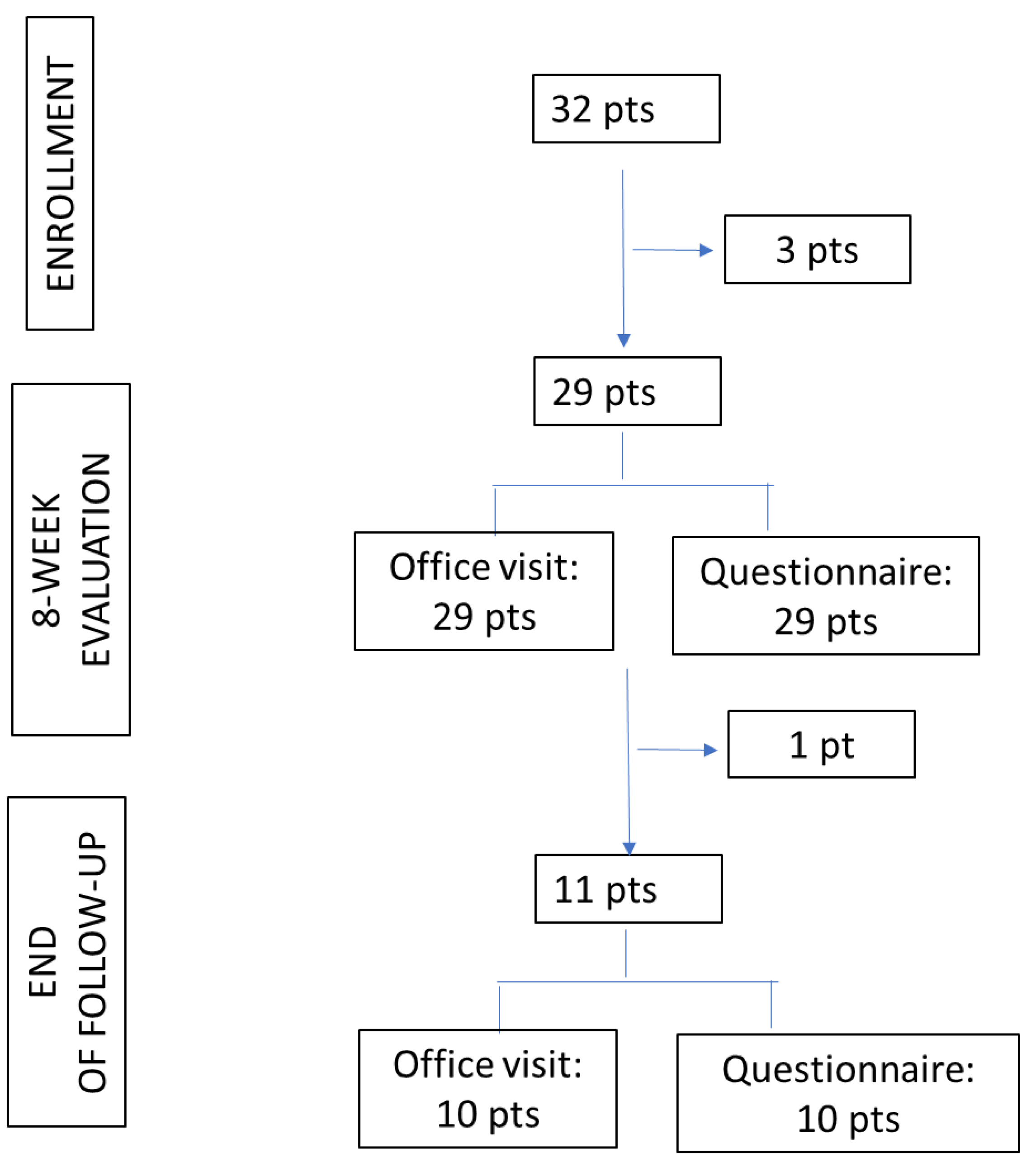

Thirty-two patients were eligible and accepted enrollment in the study (

Figure 1), then 3 patients refused to continue in the study actively.

The characteristics of the study population are summarized in

Table 1.

The questionnaire was administered to all 32 subjects enrolled, and a response was obtained from 29 patients (Response Rate 90.6%). All questionnaires were completed (Completion Rate 100%).

Twenty-two enrolled subjects were native Italian speakers. The response rate was 20/22 (91%) among Italian native speakers and 9/10 (90%) among non-native Italian speakers. The level of education of the parent completing the questionnaire was represented by a primary school diploma in 2/29 cases (7%), by a high school diploma in 12/29 cases (41%), and by graduation or postgraduation in 15/29 cases (52%). Regarding non-Italian native speakers, in all cases, the compiler reported a level of education represented by a high school diploma (4/9 subjects – 44%) or higher (degree or postgraduate in 5/9 cases – 56%).

Twenty-nine enrolled patients were visited in the medical office after 8 weeks of treatment. At the study deadline, 7 patients had completed their course of treatment, 4 discontinued the therapy, and one was lost to follow-up. Ten patients sent questionnaires (Response Rate 91%) and completed interviews (100% Completion Rate). The level of education of parents completing the questionnaire was represented by a primary school diploma in 2/10 cases (20%), by a high school diploma in 4/10 cases (40%), and by graduation or postgraduation in 4/10 cases (40%). Five out of 10 subjects (50%) were non-native Italian speakers.

Table 2 summarises the integrated information from office medical records, the electronic interview, and the causality assessment provided for ADR reports.

None reported sleep disorders at the enrollment visit. Instead, sleep-awake rhythm disturbances were reported in 10/29 subjects (34%) at the 8-week survey and in 7/10 patients (70%) at the end of follow-up (30/09/2020). According to Naranjo’s algorithm, all reported adverse events were considered potentially treatment-related. However, due to the strong negative impact of sleep disturbances on the quality of life of some families, a 2-week trial of drug suspension was needed in 2/10 subjects at the 8-week evaluation and in 3/7 patients at subsequent visits. As shown in

Table 3, the drug suspension trial was adequate in 1/2 subjects and 2/3 patients, respectively. Among patients who did not undergo a drug suspension trial, a child continued his therapy unchanged as the sleep disorder was tolerable after counselling on sleep hygiene and introduction of melatonin supplementation, and 11/17 subjects did not require any specific intervention due to the perception of a shallow symptom impact on their quality of life.

Potential confounders other than propranolol were also evaluated, as shown in

Table 4.

First-degree family history for sleep disturbances was much more represented in subjects with onset of sleep disorder before 4 months of age (2/3 subjects – 67%), compared to subjects with late-onset (3/14 – 21%), although without a statistical significance (p=0.110).

6. Discussion

According to the literature, the response rate to electronically sent questionnaires is considered the most accurate indicator for assessing the quality of research through surveys [

9,

10], and the response rate is considered high when above 80% [

11,

12]. The questionnaire proposed in this study obtained a very high response rate (91%), similar among subjects of both Italian and foreign mother tongues, at the initial survey and the remote retesting. The completion rate reflects the proportion of participants who abandon the questionnaire before the last question due to the excessive length of the survey or questions perceived as unclear or unwelcome [

11]. This questionnaire’s 100% completion rate indicates that everyone who started it completed it, including retesting. Thus, the questionnaire appeared user-friendly, at least to subjects with a medium level of education, even if they were non-native Italian speakers, and it was not excessively time-consuming for the respondents.

Regarding sleep disorders, the prevalence detected at outpatient visits was 17%, similar to data reported in the literature (2-20% of cases) [

2]. However, following the administration of the computerized anamnestic questionnaire, this prevalence increased to 59%. According to literature data, sleep disturbances are adverse events frequently reported for treatment with propranolol in IH, and they appear to be even more frequent in this study [

13,

14]. These data, we argue, are consistent with the possibility of quickly recalling a child’s health information in space and time, which is more comfortable for parents than those in a traditional medical office. It is also interesting to note that the causality assessment for all adverse events reported by caregivers in this study was “possible” or “likely” based on the Naranjo algorithm, and therefore, the reported “adverse events” should be regarded as “adverse reactions”.

The discontinuation of propranolol due to adverse effects occurred in 13% of the subjects in the present sample, a higher proportion than reported in the literature (2.5% of cases) [

14]. This may be consistent, in our opinion, with the strong negative impact of this specific adverse event on the quality of life of all family members.

We found that sleep disorders were significantly more frequent in specific physiological neurodevelopmental stages (“sleep regression” phases), but also in subjects who fell asleep maintaining physical contact with their caregivers, and in those who had bed-sharing with their parents or were actively cradled, breastfed, or moved to their parents’ bed at nocturnal awakenings. Bed-sharing and active parental intervention are well-known risk factors for the development of sleep disorders in children, and several studies have shown that autonomous children in falling asleep and in falling asleep again in case of awakenings have a longer sleep duration and a lower number of awakenings during the night [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. Therefore, this study’s data align with literature reports about general risk factors for sleep disorders in the paediatric age. Moreover, some sleep-routine habits may act as facilitating factors for the onset and/or worsening of sleep disturbances during developmental stages (e.g., physiological “sleep regression” phases), independently of any drug therapy. We may be reported by parents as suspected drug adverse events if a new drug was started in the meantime.

However, due to the limited population size of this study, further investigation is needed to allow conclusive analyses of any risk factors for the onset of sleep/awake rhythm disturbances as adverse events of treatment with propranolol in IH.

The clinical relevance of sleep disorders in children and their impact on the quality of life of the whole family unit is widely reported in the literature as resulting in poor parental physical and mental health, maternal depression, and high levels of family stress [

21]. Suppose specific counselling about general sleep habits in children, and their physiological expected variations with age, was not provided before the introduction of pharmacological therapy for IH. In that case, there should be consideration of the potential onset of sleep/awake disturbances during the treatment course, and parents may interpret these symptoms as drug-adverse events. Suppose sleep disturbances are particularly intense, due to their high level of stress and their belief in the primary role of the drug in causing the symptoms. In that case, there may be a consistent risk of premature treatment interruption and low parental adherence to second-level assessments and specific interventions, such as behavioural therapy or melatonin, as indicated by experts [

22].

The administration of an electronic, user-friendly questionnaire before the onset of treatment to identify any risk factors for sleep disturbances and its regular re-administration during the therapy course may support clinicians in their efforts to reduce sleep disturbances and improve treatment adherence.

Although the sample size is small due to the exploratory nature of the study, we believe that the participants in the study are representative of the target population according to the literature data on patients with infantile haemangiomas and that all instruments required for data collection after language translation could be highly usable in middle- and high-income countries.

The limitation of the study was that several studies in the scientific literature have investigated the use of propranolol for the treatment of IH, and some of these studies have also investigated the potential side effects of the treatment, including sleep disorders (for example, a study published in the Journal of Pediatrics in 2015 and another study published in the Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive & Aesthetic Surgery in 2016). These studies suggest that sleep disorders are a potential side effect of propranolol treatment for IH and highlight the importance of counselling on sleep hygiene habits before the start of treatment.

However, the study’s strength is that it adds to the existing literature by using a computerized specific questionnaire to evaluate sleep disorders in infants and toddlers treated with propranolol for IH. This approach identifies any potential non-drug-related confounding factors for sleep adverse events and helps manage the therapeutic course in these patients. Additionally, the study contributes to the existing literature by emphasizing the importance of counselling on sleep hygiene habits before the start of treatment to avoid unjustified suspensions of therapy. Overall, the study adds to the existing literature by providing new insights and a new approach to evaluating the side effects of propranolol treatment for IH.

7. Conclusions

Using this computerized specific questionnaire, a high prevalence of sleep disorders emerges in infants and toddlers treated with propranolol for IH. The application of the questionnaire, alongside the outpatient evaluations, allows for the identification of any potential non-drug-related confounding factors for sleep adverse events, facilitating easier management of the therapeutic course with propranolol in patients with IH. Moreover, considering the potentially significant impact of these symptoms on patients’ families, counselling on sleep hygiene habits appears to be strongly indicated before the onset of treatment to avoid unjustified suspensions of the therapy, especially in cases with an expected favourable risk/benefit ratio for treatment.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org. The electronic interview for the survey.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.O. and E.R.; Methodology, R.O.; Software, F.O. and R.O.; Validation, F.O. and R.O.; Formal Analysis, F.O., R.O., M.Z., E.R.; Investigation, F.O. and E.R.; Resources, E.R..; Data Curation, F.O. and R.O.; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, F.O., R.O., M.Z., E.R.; Writing – Review & Editing, F.O., R.O., M.Z., E.R.; Visualization, M.Z.; Supervision, M.Z.; Project Administration, E.R.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of University Hospital of Verona (protocol code: EI-TM Prog. 2792CESC- vers: 2, date of approval 15/07/2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are unavailable due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Krowchuk DP, Frieden IJ, Mancini AJ, Darrow DH, Blei F, Greene AK, Annam A, Baker CN, Frommelt PC, Hodak A, Pate BM, Pelletier JL, Sandrock D, Weinberg ST, Whelan MA; Subcommittee On The Management Of Infantile Hemangiomas. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Infantile Hemangiomas. Pediatrics, 2019;143(1).

- Drolet BA, Frommelt PC, Chamlin SL, Haggstrom A, Bauman NM, Chiu YE, Chun RH, Garzon MC, Holland KE, Liberman L, MacLellan-Tobert S, Mancini AJ, Metry D, Puttgen KB, Seefeldt M, Sidbury R, Ward KM, Blei F, Baselga E, Cassidy L, Darrow DH, Joachim S, Kwon EK, Martin K, Perkins J, Siegel DH, Boucek RJ, Frieden IJ. Initiation and use of propranolol for infantile hemangioma: report of a consensus conference. Pediatrics 2013; 131(1):128-40.

- Schreiber PW, Sax H, Wolfensberger A, Clack L, Kuster SP; Swissnoso. The preventable proportion of healthcare-associated infections 2005-2016: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2018;39(11):1277-1295.

- Behar JA, Liu C, Kotzen K, Tsutsui K, Corino VDA, Singh J, Pimentel MAF, Warrick P, Zaunseder S, Andreotti F, Sebag D, Kopanitsa G, McSharry PE, Karlen W, Karmakar C, Clifford GD. Remote health diagnosis and monitoring in the time of COVID-19. Physiol Meas. 2020 10;41(10):10TR01.

- Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981;30(2):239-45.

- Mindell JA, Owens JA. A clinical guide to pediatric sleep-diagnosis and management of sleep problems. Second Ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2010.

- Sadeh, A. A brief screening questionnaire for infant sleep problems: validation and findings for an Internet sample. Pediatrics. 2004 Jun;113(6):e570-7.

- Mindell JA, Leichman ES, Composto J, Lee C, Bhullar B, Walters RM. Development of infant and toddler sleep patterns: real-world data from a mobile application. J Sleep Res. 2016;25(5):508-516.

- Biemer, P. P., Lyberg, L. E. Introduction to Survey Quality, New York: John Wiley & Sons; 2003.

- American Association for Public Opinion Research. Standard Definitions: Final Dispositions of Case Codes and Outcome Rates for Surveys, Second Edition, Ann Arbor, MI: AAPOR; 2000.

- AAPOR. “Standard Definitions - AAPOR”. AAPOR. Retrieved 3 March 2016. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/emre.12375.

- Evans, S.J. Good surveys guide. BMJ. 1991; 302 (6772): 302–3.

- Marqueling AL, Oza V, Frieden IJ, Puttgen KB. Propranolol and infantile hemangiomas four years later: a systematic review. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:182–91.

- Leaute-Labreze C, Boccara O, Degrugillier-Chopinet C, et al. Safety of Oral Propranolol for the Treatment of Infantile Hemangioma: A Systematic Review. Pediatrics, 2016;138(4):e20160353-e20160353.

- Adair R, Bauchner H, Philipp B, Levenson S, Zuckerman B. Night waking during infancy: role of parental presence at bedtime. Pediatrics. 1991;87:500–4.

- Hayes MJ, Parker KG, Sallinen B, Davare AA. Bedsharing, temperament, and sleep disturbance in early childhood. Sleep, 2001;24(6):657-62.

- Sadeh A, Tikotzky L, Scher A. Parenting and infant sleep. Sleep Med Rev. 2010;14:89–96.

- Byars KC, Yolton K, Rausch J, Lanphear B, Beebe DW. Prevalence, patterns, and persistence of sleep problems in the first 3 years of life. Pediatrics 2012;129:e276-8.

- Bruni O, Baumgartner E, Sette A, Ancona M, Caso G, Di Cosimo ME, Mannini A, Ometto M, Pasquini A, Ulliana A, Ferri R. Longitudinal study of sleep behavior in normal infants during the first year of life. J Clin Sleep Med 2014;10(10):1119-27.

- Hysing M, Harvey AG, Torgersen L, Ystrom E, Reichborn-Kjennerud T, Sivertsen B. Trajectories and predictors of nocturnal awakenings and sleep duration in infants. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2014;35(5):309-16.

- Sharkey, K.M. Infant sleep and feeding patterns are associated with maternal sleep, stress, and depressed mood in women with a history of major depressive disorder. Arch Womens Ment Healt 2016;19(2):209-1.

- Bruni O, Alonso-Alconada D, Besag F, et al. Current role of melatonin in pediatric neurology: clinical recommendations. Eur J Paediatr Neurol 2015;19(2):122-33.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).