1. Introduction

The marketing industry is continuously evolving, necessitating that education programs adapt to accommodate new developments. Graduating marketing students must possess the requisite knowledge and skills to meet current job market demands. Geitz et al. [

1] highlight the importance of creating learning environments that enable learners to acquire knowledge through complex and meaningful real-life experiences. This approach ensures that students can perform as marketing professionals at various levels, including the “micro-level of the customer, meso-level of value constellation, and macro-level of society” (p.2). Problem-based learning (PBL) offers students opportunities to address real-life problems, thereby fostering the development of critical skills such as critical thinking and decision-making.

Rosenbaum et al. [

2] describe PBL as an instructional and curriculum strategy designed to empower students to devise viable solutions to specific problems by integrating theory and practice, conducting research, and applying their knowledge and skills. This approach emphasizes active learning and student engagement, encouraging learners to take responsibility for their educational journey.

PBL is an integral component of marketing education, as it equips new marketing professionals with real-world experience and the ability to meet employers’ expectations. Marketing requires creativity, strategic thinking, and the ability to adapt to rapidly changing market conditions and consumer behaviors. Geitz et al. [

1] identify PBL as an effective strategy for helping students develop these essential capabilities. PBL engages students in projects that require them to integrate marketing theories with practical applications, such as developing marketing strategies for new products, analyzing consumer data, and creating advertising campaigns [

3]. This hands-on experience is invaluable, as it prepares students for actual marketing challenges and enhances their confidence and competence.

Additionally, Mardani et al. [

4] found that the collaborative nature of PBL aids students in developing interpersonal and communication skills. For instance, students are required to work effectively in teams, present their ideas persuasively, and negotiate differing viewpoints. This dynamic creates opportunities for feedback, which Geitz et al. [

1] identify as a tool for promoting deep learning and fostering self-efficacy among marketing students. Therefore, PBL provides a robust framework for equipping future marketers with the skills and mindset needed to thrive in their careers.

This systematic literature review with bibliometric analysis (SLRBA) synthesizes data on the concept of PBL and its integration into marketing education. The research findings are organized into sections based on identified themes, including the definition of the PBL concept, strategies to promote PBL in marketing education, and the advantages and challenges associated with its implementation.

2. Materials and Methods

The researcher employed a systematic literature review with bibliometric analysis (SLRBA) methodology, which offers a comprehensive and objective approach to evaluating existing literature. This method ensures that the research encompasses a broad range of studies and theoretical perspectives. Problem-Based Learning (PBL), being an interdisciplinary approach, integrates educational theory, marketing practices, and pedagogical innovations. The SLRBA method facilitates the identification, analysis, and synthesis of data across multiple academic fields.

Unlike traditional literature reviews, SLRBA utilizes a replicable, scientific, and transparent process designed to minimize bias by conducting an exhaustive search of both published and unpublished literature relevant to the study topic. Additionally, the researcher provides an audit trail, enabling readers to evaluate the quality of the included studies, research procedures, and conclusions.

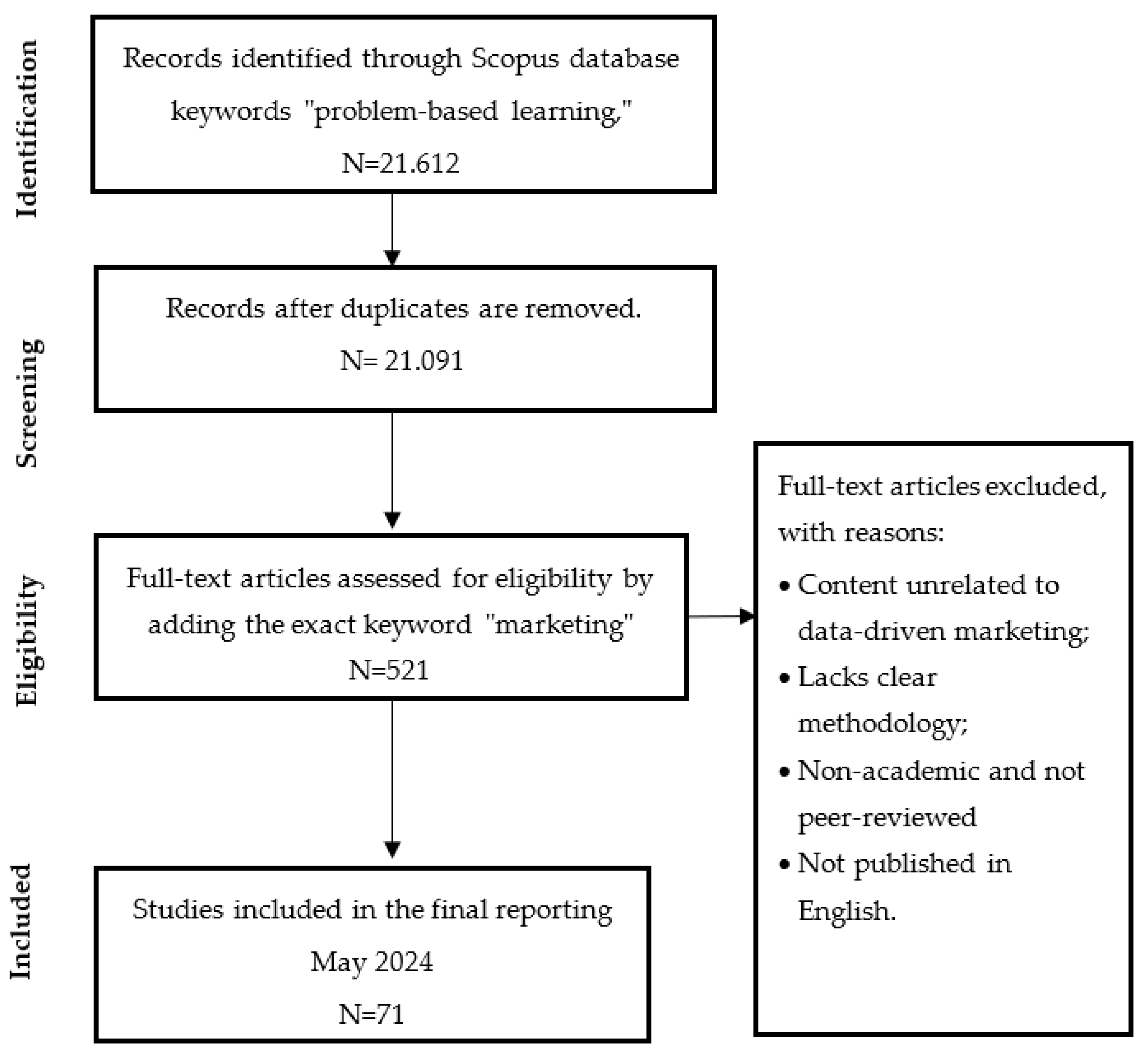

The SLRBA process involves a comprehensive screening and selection of information sources through three phases and six steps, as detailed in

Table 1, to ensure the validity and accuracy of the presented data.

The researchers conducted their literature search using the Scopus database, a highly respected resource in the scientific and academic communities. However, it is important to acknowledge the study’s limitations due to its exclusive reliance on Scopus, thereby excluding other scientific and academic databases. Ideally, the literature search should encompass peer-reviewed publications up until May 2024.

The initial search in the Scopus database used the keywords “problem-based learning,” yielding 21,612 sources. The researchers then screened the titles, abstracts, and keywords to assess relevance to the study topic. Following this, duplicates were eliminated, and inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied. The included studies had to focus on PBL and its integration into marketing education. Additionally, the researchers selected sources with clear methodologies and robust data.

The results were further filtered by publication type, including peer-reviewed journal articles, conference papers, books, book chapters, dissertations, and theses. This process reduced the search results to 521 sources. Finally, incorporating the keyword “marketing” narrowed the relevant sources to 71, which were synthesized in the final report (

Figure 1).

A set of standards aimed at improving the transparency and quality of systematic reviews is crucial for ensuring robust and reliable scientific evidence. The PRISMA guidelines provide a detailed checklist and a flow diagram to assist researchers in reporting their systematic reviews clearly and comprehensively. This effort is essential for facilitating informed decision-making in both clinical practice and scientific research.

For data analysis, we employed content and thematic analysis methods to categorize and discuss the diverse documents, as recommended by Rosário and Dias. The 71 documents indexed in Scopus were analyzed both narratively and bibliometrically to deepen our understanding of the content and identify common themes that directly address the research question. Among the selected documents, 46 are articles, 14 are conference papers, 7 are part of a book series, and 4 are books.

3. Publication Distribution

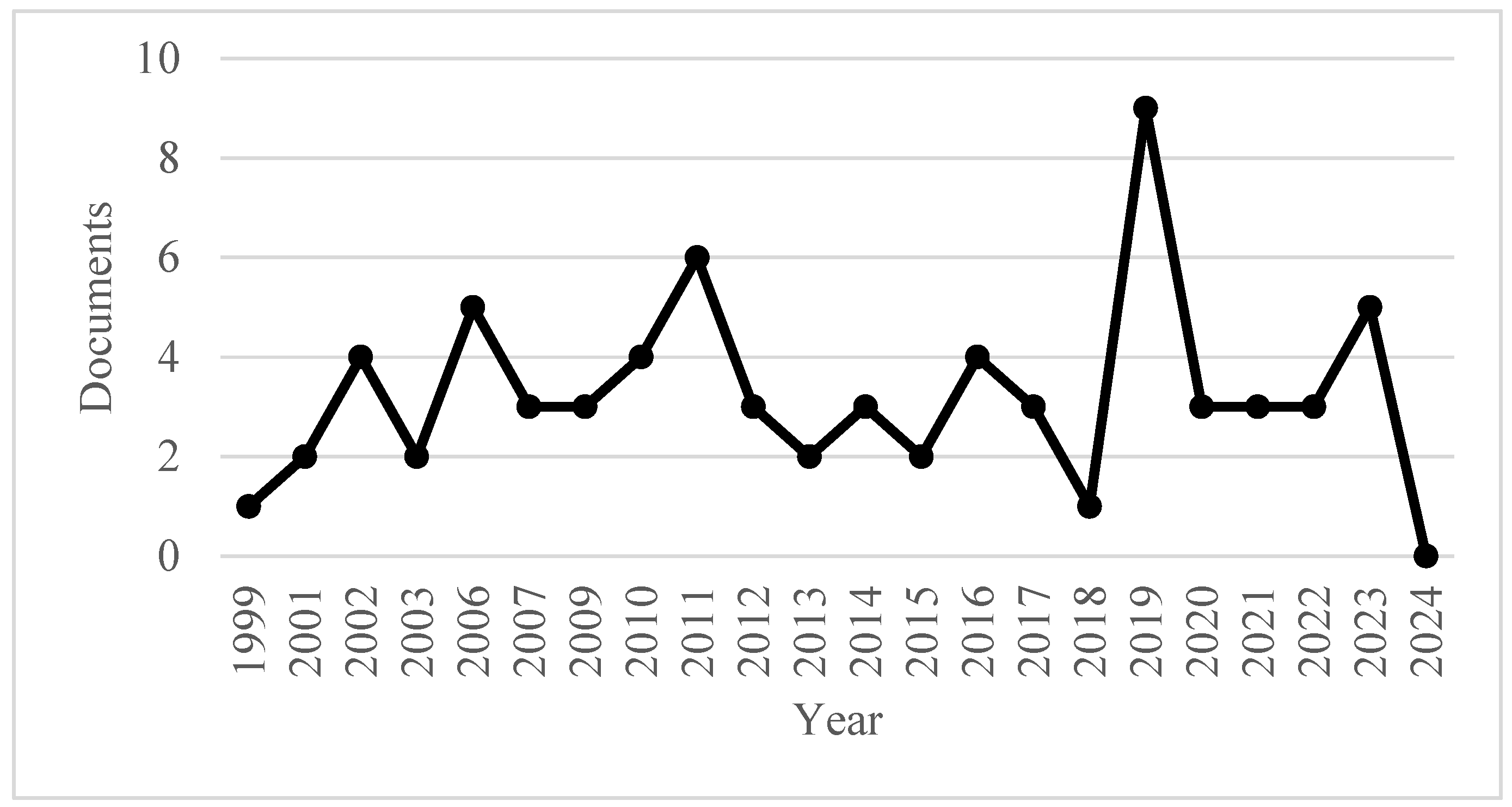

Problem-Based Learning Marketing Peer-Reviewed Articles through May 2024. The year 2019 had the highest number of peer-reviewed publications, reaching 9.

Figure 2 summarizes the peer-reviewed literature published through May 2024.

The publications were sorted out as follows, with 2 (Strategic Marketing Planning And Control Third Edition; Sefi Annual Conference 2011; Reference Services Review; Nature Biotechnology; Journal Of Public Health Management And Practice; Journal Of Marketing Education; International Symposium On Project Approaches In Engineering Education; American Journal Of Pharmaceutical Education; Advances In Intelligent Systems And Computing); and the remaining publications with 1 document.

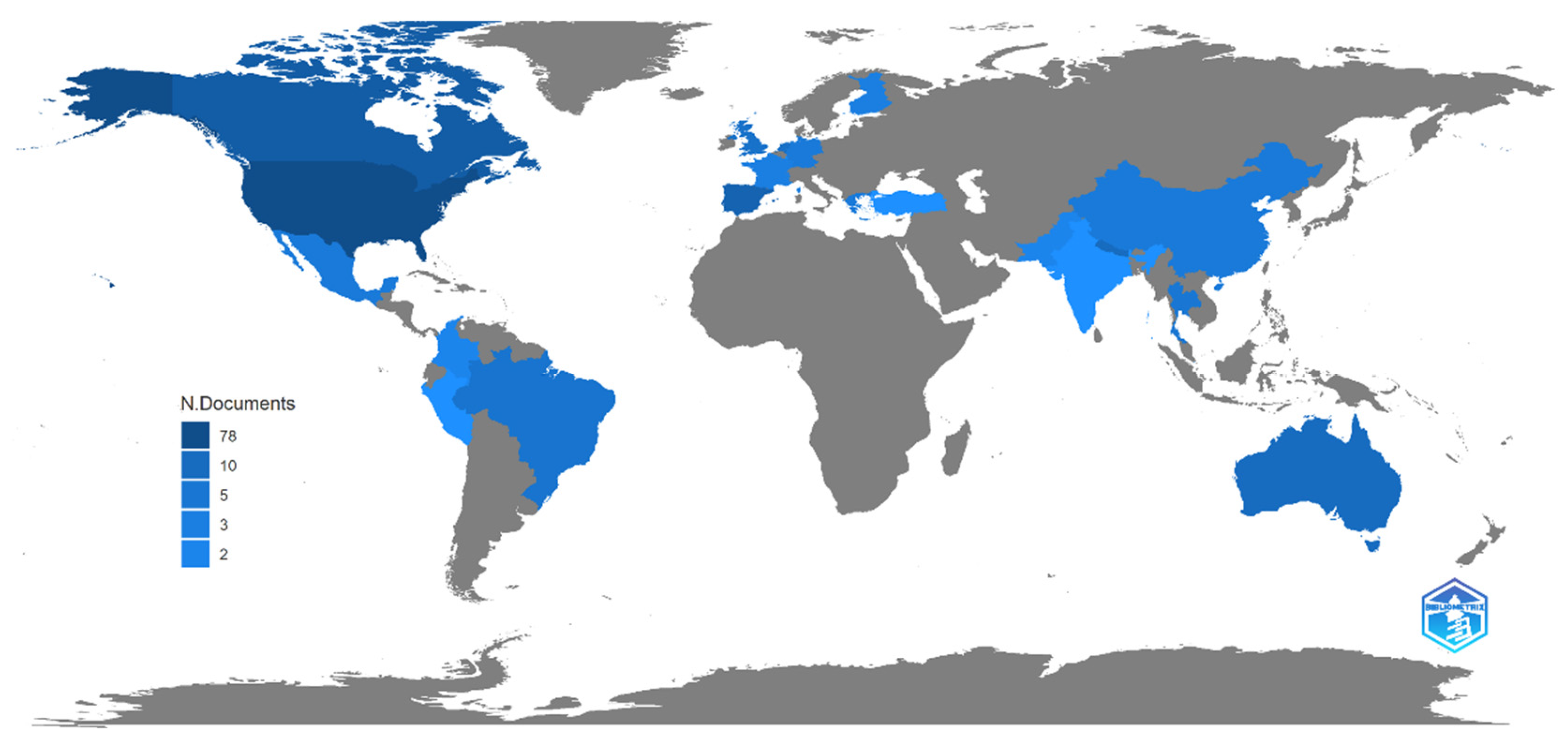

Similarly,

Figure 3 illustrates the regions with the most significant literature contributions on the topic. The USA, Canada and SPAIN stand out with the highest levels of scientific output in related fields, among other countries publishing on the subject.

The publications were categorized as follows: 2 publications each for “Strategic Marketing Planning And Control Third Edition,” “Sefi Annual Conference 2011,” “Reference Services Review,” “Nature Biotechnology,” “Journal Of Public Health Management And Practice,” “Journal Of Marketing Education,” “International Symposium On Project Approaches In Engineering Education,” “American Journal Of Pharmaceutical Education,” and “Advances In Intelligent Systems And Computing.” The remaining publications each had 1 document.

In

Table 2, we analyze the Scimago Journal & Country Rank (SJR), the best quartile, and the H index for various journals, including “Nature Biotechnology” with an SJR of 18,120, Q1, and an H index of 511. There are a total of 17 publications in Q1, 13 publications in Q2, 6 publications in Q3, and 3 publications in Q4. Publications in the best quartile Q1 represent 27% of the 62 publication titles; best quartile Q2 represents 21%; best quartile Q3 represents 10%; and best quartile Q4 represents 5% of the 62 publication titles. Finally, 24 publications without indexing data represent 39% of the publications. As shown in

Table 2, the significant majority of publications are in quartile Q1.

The 71 scientific and academic documents covered a wide range of subject areas: Social Sciences (35), Engineering (18), Business, Management and Accounting (16), Computer Science (12), Medicine (10), Pharmacology, Toxicology and Pharmaceutics (5), Economics, Econometrics and Finance (5), Biochemistry, Genetics and Molecular Biology (5), Mathematics (4), Nursing (3), Health Professions (3), Psychology (2), Immunology and Microbiology (2), Decision Sciences (2), Chemical Engineering (2), Materials Science (1), Energy (1), Chemistry (1), Arts and Humanities (1), and Agricultural and Biological Sciences (1).

The most cited article was “Barriers to the Circular Economy—Integration of Perspectives and Domains,” with 320 citations. Published in Nature Biotechnology, this article has an SJR of 18,120, is in the top quartile (Q1), and has an H index of 511. It explores how the proliferation of new media and industry involvement in academic research affect public trust and engagement in science, providing recommendations to enhance science communication.

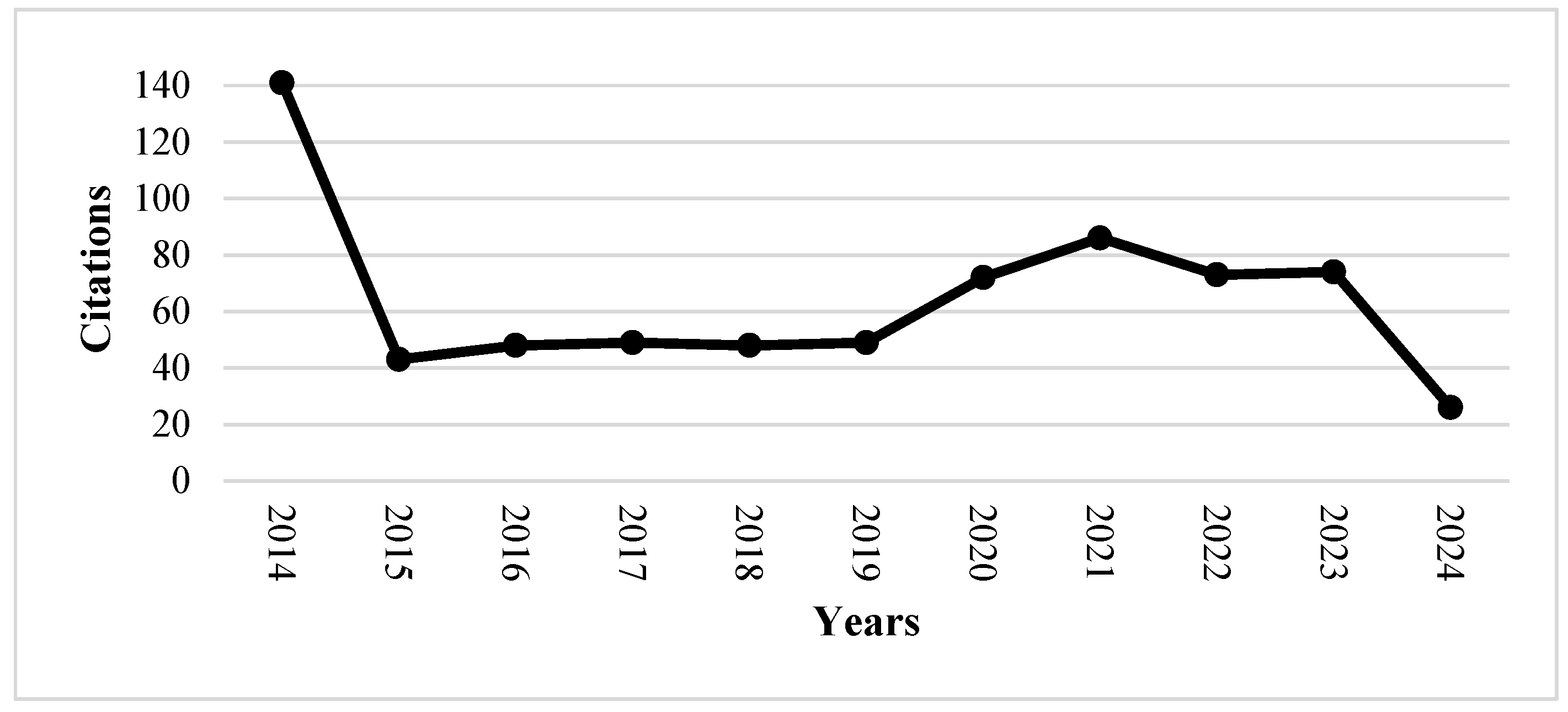

Figure 4 analyzes citation trends for documents published until May 2024. The period from 2014 to 2024 shows a positive net growth in citations, with an R2 of 73%, reaching a total of 809 citations by May 2024.

The h-index measures the productivity and impact of a published work based on the maximum number of articles that have been cited at least that same number of times. Among the documents considered for the h-index, 13 were cited at least 13 times.

From the period ≤2014 to May 2024, the 71 scientific and academic documents accumulated a total of 809 citations, with 21 of these documents not receiving any citations. During the same period, the self-citation count was 723.

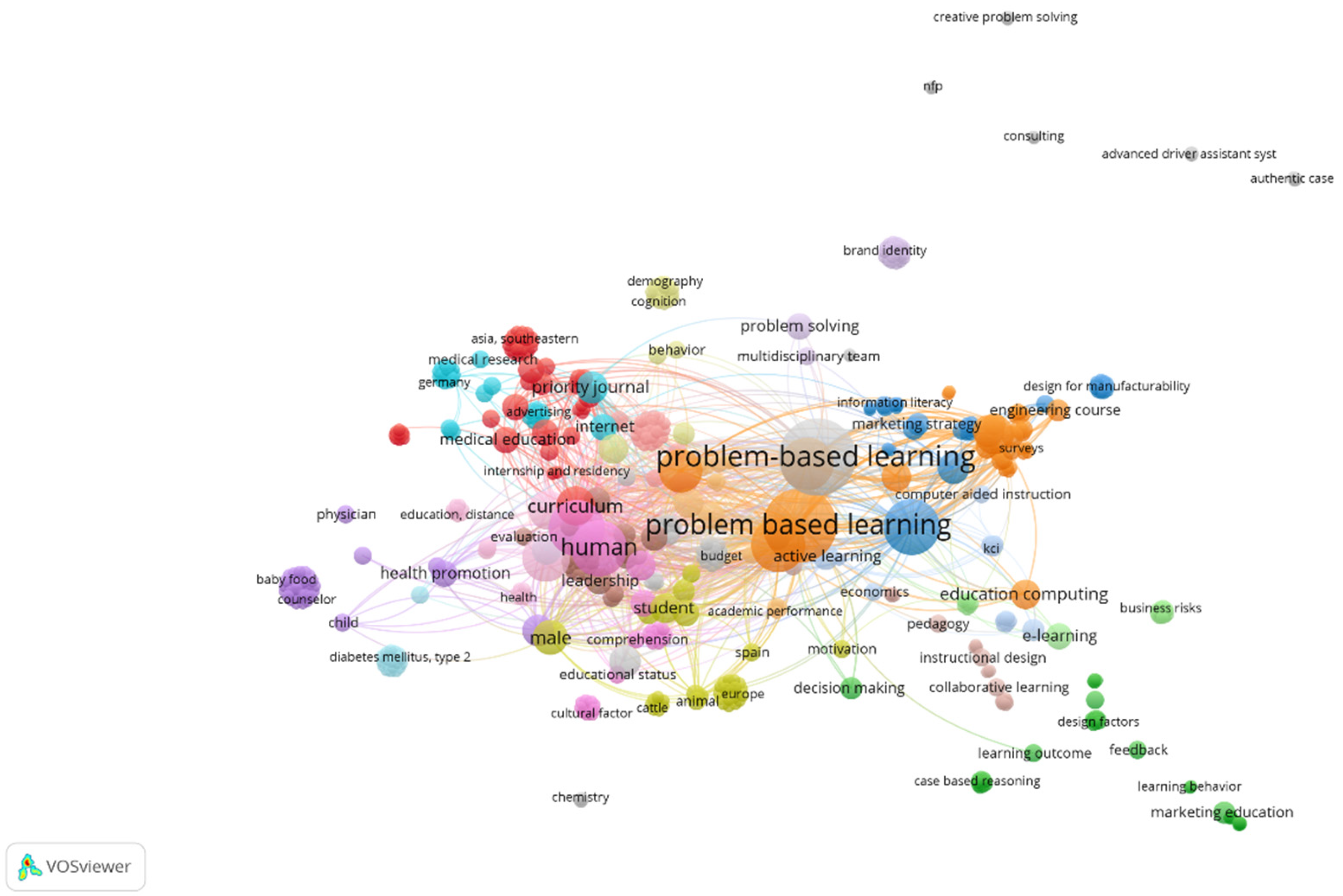

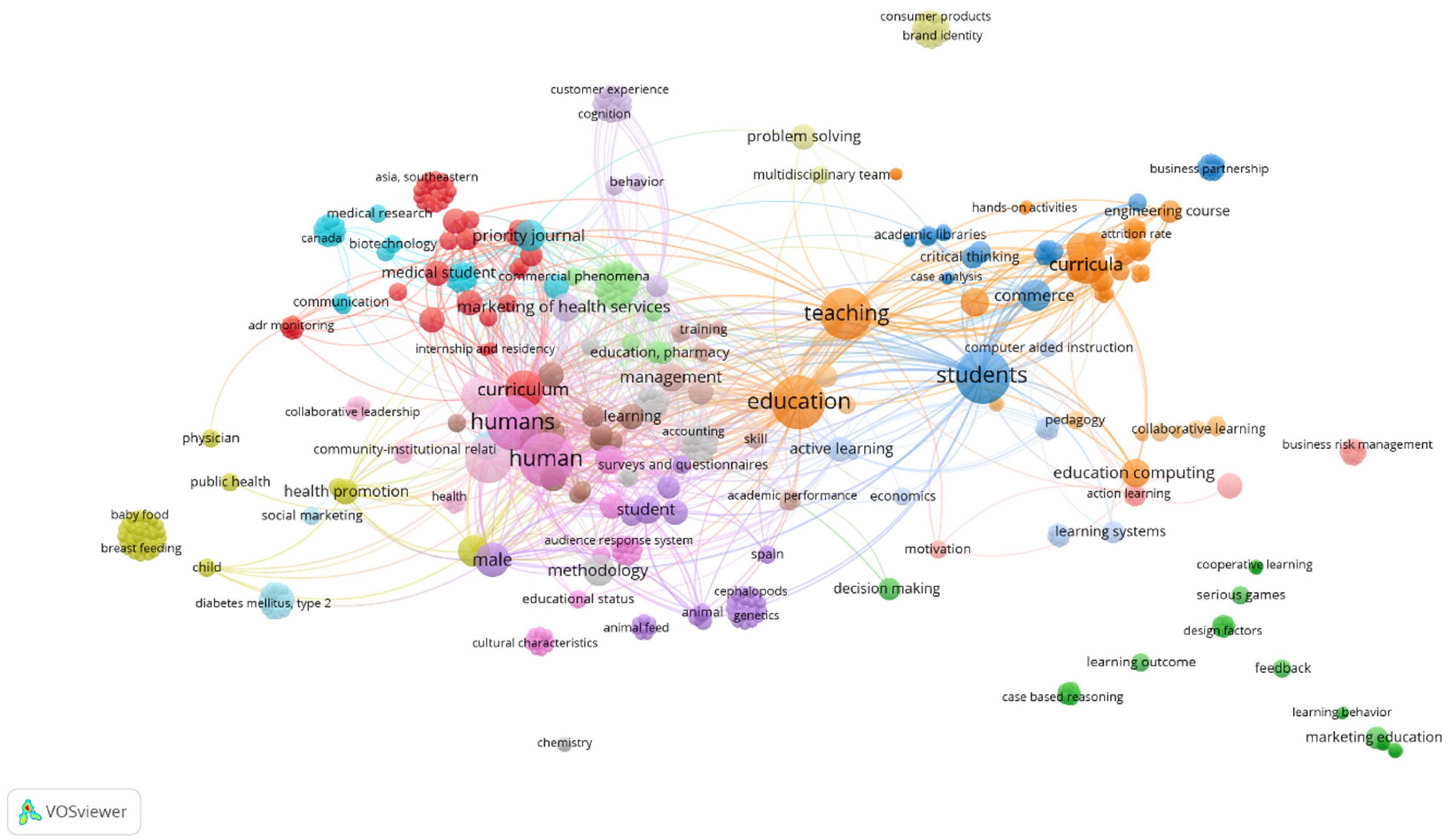

The bibliometric analysis aimed to explore and identify metrics revealing the patterns and development of scientific or academic content within the documents, using principal keywords (

Figure 5). In this visualization, the size of each network node indicates the frequency of the associated keyword, representing how often it appears. Additionally, the connections between the nodes signify keyword co-occurrences, where keywords appear together. The thickness of these links highlights the frequency of these co-occurrences, illustrating how often the keywords are found together.

In these diagrams, the size of a node corresponds to the frequency of its keyword, while the thickness of the links between nodes indicates the frequency of keyword co-occurrences. Each color represents a different thematic cluster, with the nodes illustrating the scope of topics within a theme and the links showing the relationships among these topics under the same thematic umbrella.

The results were derived using the scientific software VOSviewer, specifically designed to analyze the key search term “problem-based learning marketing.” This study utilized scientific and academic documents focusing on this area. In

Figure 6, we can analyze the connected keywords, illustrating the network of keywords that co-occur in each scientific article. This analysis helps identify the subjects investigated by researchers and pinpoint emerging trends for future studies.

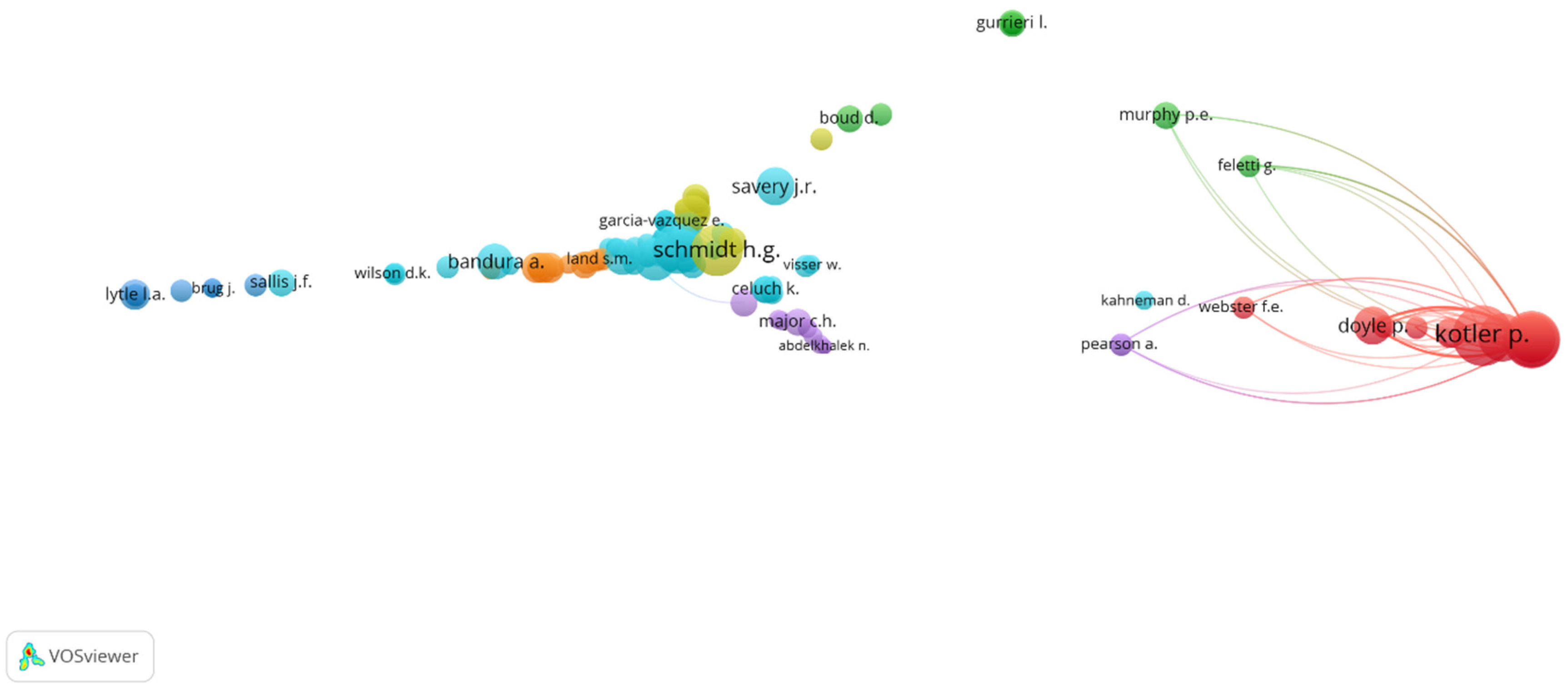

Lastly,

Figure 7 displays an extensive bibliographic coupling based on the document analysis, enabling interactive exploration of the co-citation network. This feature allows users to navigate through the network and uncover patterns within “problem-based learning marketing” across different authors.

In summary, the chosen methodology ensured precision and provided comprehensive data for other researchers to build upon this review. By addressing key issues, the methodology enhanced coherence and improved the overall validity and reliability of the findings. Consequently, we adhered to established guidelines for systematic reviews and meta-analyses, achieving a high methodological standard. These aspects will be discussed in further detail below.

4. Theoretical Perspectives

In recent years, employers have increasingly expressed concerns about graduates’ inadequate knowledge and skills. For example, Lisá et al. [

8] found that most employers refrain from hiring graduates due to a lack of practical and discipline-specific skills. Rapid technological advancements have further highlighted significant gaps in students’ abilities to perform effectively in marketing roles. Problem-Based Learning (PBL) addresses this issue by exposing learners to real-world challenges, thereby better preparing them for their future careers. This literature review section synthesizes data on the PBL concept and its effectiveness in marketing education.

4.1. Understanding the Concept of Problem-Based Learning (PBL)

Problem-Based Learning (PBL) is an educational approach that emphasizes student-centered learning through the exploration and resolution of real-world problems. First introduced in 1969 at McMaster University, PBL serves as an alternative to traditional lecture-based instruction. This method engages students by encouraging them to adopt active, self-directed learning approaches, such as establishing learning objectives, searching for appropriate educational resources, collaborating with peers to create solutions, and assessing their progress over time.

Geitz et al. indicate that students work collaboratively in small groups to identify what they need to learn to address the problem, engage in self-directed research, and apply their findings to develop and propose solutions. In this model, the instructor’s role shifts from being the primary source of information to acting as a facilitator who guides the learning process, supports student inquiry, and encourages critical thinking. Consequently, this approach helps students develop a deeper understanding of the subject matter and enhances essential skills such as critical analysis, problem-solving, teamwork, and effective communication.

PBL is grounded in constructivist learning theories, which posit that knowledge is constructed through active engagement and contextual experiences. This makes PBL particularly effective in preparing students for the complexities of real-life professional environments.

4.2. Strategies Used in PBL in Marketing Education

Multiple strategies are used to implement PBL in marketing education. According to Cunningham et al. [

9], students have different learning preferences, and each approach has varying results, such as various levels of student engagement and outcomes. Given that PBL is meant to be student-centric, understanding its different techniques can help implement effective programs based on individual student preferences and needs.

4.2.1. Social Media

Social media platforms enable students to engage with real-world marketing environments, analyze market trends, and interact with consumers and brands. According to Antonoff [

12], students can use social media to develop and test marketing campaigns, gather and analyze consumer feedback, and observe the immediate impact of their marketing strategies. For instance, students can create and manage social media pages for hypothetical or real products, learn how to craft engaging content, optimize posts for different audiences, and use social media analytics to measure campaign success [

13,

14]. This hands-on approach enhances their understanding of digital marketing and equips them with practical skills in content creation, community management, and data analysis.

4.2.2. Serious Games

Serious games are educational tools that incorporate game-based elements to facilitate learning engagingly and interactively. They are used in PBL marketing education to simulate real-world market scenarios where students must apply marketing principles to make strategic decisions. Correia and Simões-Marques [

15] explain that these games often involve challenges such as product launches, competitive market analysis, pricing strategies, and advertising campaigns. A serious game in PBL might require students to manage a virtual company, where they need to balance budgets, respond to consumer trends, and compete against other virtual businesses [

16]. This immersive learning experience allows students to experiment with different marketing tactics, understand the consequences of their decisions, and develop problem-solving skills in a risk-free environment [

15]. In addition, the immediate feedback and realistic consequences provided in serious games help students grasp complex marketing concepts more effectively and prepare them for real-life marketing challenges.

4.2.3. E-learning

E-learning leverages digital platforms and online resources to deliver educational content, enabling a flexible and interactive learning experience. In PBL for marketing education, e-learning can encompass a wide range of tools and activities, including online courses, webinars, interactive modules, and virtual collaboration spaces. Delgado-Peña and Subires-Mancera [

17] indicate that e-learning platforms provide students with access to multimedia content, discussion forums, and quizzes that reinforce learning. Therefore, students can use these platforms to work on marketing problems at their own pace and access resources such as case studies, tutorials, and industry reports [

18,

19]. In addition, Monedero-Perales et al. [

20] imply that e-learning facilitates remote collaboration, allowing students to work in virtual teams, share insights, and develop solutions to marketing challenges using tools like Google Docs, Slack, or Trello. This approach supports students’ diverse learning needs and helps them build digital literacy and collaboration skills that are crucial in modern marketing [

21]. Therefore, integrating e-learning into PBL enables educators to create a learning environment that enhances student engagement and prepares them for the digital aspects of marketing careers.

4.2.4. Feedback

Feedback provides students with valuable insights into their performance and progress. In PBL, feedback can come from various sources, including instructors, peers, industry professionals, and even consumers. Armengol et al. [

22] explain that this feedback helps students refine their problem-solving approaches, improve their marketing strategies, and enhance their overall learning experience. For instance, instructors can provide formative feedback on assignments and projects, highlighting strengths and areas for improvement. Peer feedback, facilitated through group discussions and peer review sessions, encourages collaborative learning and diverse perspectives [

23]. In addition, McDonald [

24] indicates that feedback from industry professionals through guest lectures, mentorship, or project evaluations bridges the gap between academic learning and real-world application. Students can also gather consumer feedback through surveys or social media interactions, allowing them to understand market reactions to their marketing campaigns. Armengol et al. [

22] explain that effective feedback in PBL is timely, specific, and constructive, guiding students to reflect on their learning, identify gaps, and make necessary adjustments. PBL programs with robust feedback mechanisms result in continuous improvement and help students develop critical thinking and adaptive skills.

4.2.5. Audience Response Systems

Audience response systems (ARS) are interactive technology tools that allow instructors to gather immediate feedback from students during lectures and discussions. These systems are used in PBL programs to enhance engagement, assess understanding, and facilitate active learning [

25]. In addition, they enable instructors to pose questions related to marketing problems or case studies and receive instant responses from students through handheld devices or smartphones. According to Wood and Shirazi [

26], educators use ARS to quickly gauge students’ comprehension of key marketing concepts, track their progress, and identify areas that may require further explanation. Immediate feedback allows for responsive teaching, where the instructor can adjust the lesson based on the student’s responses [

27,

28]. It also facilitates a more interactive and engaging learning environment. Besides, ARS can promote active participation among students reluctant to speak up in traditional classroom settings. They can anonymously submit their answers and contribute to discussions without the fear of judgment [

25]. As a result, this strategy encourages a more inclusive and participatory classroom atmosphere. This use of ARS in PBL supports real-time formative assessment and helps students develop critical thinking skills as they analyze and respond to complex marketing scenarios.

4.2.6. User-Generated Content

User-generated content (UGC) refers to any form of content, such as videos, blogs, discussion posts, digital images, and social media updates, created by users or students rather than by instructors or marketers. UGC in PBL programs is a powerful tool for engaging students and enhancing their learning experience [

29]. They are encouraged to create and share their content as part of their problem-solving activities. For example, they might develop marketing campaigns, produce promotional videos, write blog posts, or create social media content [

30]. This approach allows students to apply marketing theories and concepts creatively, thereby developing practical skills in content creation and digital marketing. Generating content enables students to experiment with different marketing strategies, receive feedback from peers and instructors, and refine their approaches based on real-world responses [

31,

32]. This hands-on experience is invaluable in preparing students for the demands of the marketing industry, where user engagement and content creation are critical. Moreover, incorporating UGC in PBL supports a collaborative learning environment. Students can share their work with classmates, discuss various approaches, and collectively analyze the effectiveness of different marketing strategies [

33]. This collaborative aspect of UGC helps build a sense of community and enhances peer-to-peer learning, as students learn their experiences from the insights and feedback of others.

4.2.7. Simulation Exercises

Simulation exercises are immersive, interactive activities that replicate real-world marketing scenarios. They allow students to practice and refine their skills in a controlled environment [

34]. In PBL programs for marketing education, simulation exercises provide experiential learning opportunities where students can apply theoretical knowledge to practical situations. These exercises can take various forms, such as virtual simulations, role-playing games, or computer-based simulations [

35,

36]. In these environments, students can analyze market data, adjust their strategies based on simulated consumer feedback, and observe the outcomes of their decisions over time. As a result, simulation exercises are associated with multiple educational benefits, including improving students’ understanding of the complexities of market dynamics and developing strategic thinking skills [

37]. Simulating real-life challenges allows students to gain insights into the cause-and-effect relationships inherent in marketing decisions. Consequently, this enhances their problem-solving abilities. Finally, simulations often include scenarios that require teamwork and collaboration. These practices help students develop essential interpersonal skills [

38]. For example, while working in groups, students must communicate effectively, negotiate roles, and collaborate to achieve common goals. This teamwork aspect mirrors the collaborative nature of the marketing profession, thereby preparing students for future roles in the industry.

4.2.8. Educational Robotics

Educational robotics involves using programmable robots as learning tools to teach various concepts and skills through hands-on, interactive activities. They are commonly associated with STEM education. However, educational robotics can also be effectively integrated into PBL for marketing education to enhance students’ understanding and engagement [

39]. For instance, students might program robots to perform tasks that simulate consumer interactions, automate marketing processes, or demonstrate product features. This hands-on approach helps students understand the application of technology in marketing, such as how automation and artificial intelligence can optimize marketing campaigns and improve customer experiences [

40,

41]. Working with educational robotics in a PBL context encourages students to think creatively and solve problems related to marketing strategies and consumer engagement. They can design and program robots to carry out specific marketing activities, such as distributing promotional materials, conducting surveys, or even interacting with potential customers at simulated trade shows or events [

42]. These activities require students to apply marketing principles while also developing technical skills in programming and robotics.

4.3. Advantages of PBL in Marketing Education

Research shows various advantages of implementing PBL programs in educational institutions. For instance, PBL bridges the gap between theoretical instructions and the practical application of concepts. This allows students to understand how concepts taught in class apply in real-life working environments [

43]. As a result, students engaged in PBL programs are more likely to graduate with employable skills. Other advantages include improved ability to collaborate, enhanced problem-solving and critical thinking skills, and enhanced student control. This section synthesizes data on multiple benefits and opportunities of PBL in marketing education.

4.3.1. Access to Hands-On Experience

PBL provides hands-on experience by offering students a tangible understanding of marketing concepts and strategies. Unlike traditional lecture-based approaches, PBL immerses students in real-world marketing scenarios, allowing them to apply theoretical knowledge to practical situations [

44]. Students engage directly with marketing challenges, such as developing marketing campaigns through hands-on projects, case studies, and simulations. This allows them to analyze consumer behavior and create strategic plans for product launches [

45]. In addition, this experiential learning approach provides students with a deeper understanding of marketing principles and practices. This occurs by allowing them to experience firsthand the complexities and nuances of marketing decision-making [

46,

47]. Moreover, hands-on experience in PBL empowers students to develop essential skills that are highly valued in the marketing industry. For instance, active participation in marketing projects and simulations allows students to learn to think critically, analyze data, and make informed decisions [

48]. These skills are crucial for success in marketing roles. In addition, hands-on experience encourages students to explore different approaches, experiment with new ideas, and learn from both successes and failures, thereby fostering creativity and innovation.

4.3.2. Interactive Collaboration

Interactive collaboration offers students the opportunity to engage with peers, instructors, and industry professionals in an interactive learning environment. In traditional classroom settings, learning is primarily passive. PBL changes this by encouraging students to actively participate in collaborative activities such as group projects, discussions, and problem-solving exercises [

49,

50]. This interactive collaboration benefits students by allowing them to share ideas, perspectives, and experiences with their peers [

51]. As a result, it enriches their learning experience and expands their understanding of marketing concepts. In addition, interactive collaboration in PBL develops essential teamwork and communication skills. Working together on marketing projects and assignments allows students to learn to communicate effectively, negotiate differing viewpoints, and resolve conflicts [

52]. The collaboration creates a supportive learning environment where everyone feels valued and respected. This sense of camaraderie enhances motivation and engagement and promotes a culture of cooperation and mutual support [

53]. Interactive collaboration in PBL facilitates meaningful interactions, promotes deeper learning, and prepares students for the collaborative nature of the marketing profession.

4.3.3. Problem-Solving and Critical Thinking Skills

PBL in marketing education is instrumental in cultivating problem-solving and critical-thinking skills among students. These capabilities prepare them for the challenges in the marketing industry. PBL encourages students to actively engage with real-world marketing problems, analyze information, and develop creative solutions. Klebba and Hamilton [

54] indicate that they work with authentic marketing scenarios, which challenge them to think critically about market factors, consumer behavior, and competitive landscapes. These practices help improve their ability to identify, analyze, and solve complex problems [

55]. In addition, the emphasis on inquiry-based learning in PBL contributes to their critical thinking and problem-solving skills. Students in PBL programs are tasked with asking questions, conducting research, and exploring multiple perspectives to arrive at well-informed solutions [

36]. This process encourages curiosity, independent thinking, and a willingness to challenge assumptions. This mindset is essential for innovation and success in marketing roles.

PBL programs allow students to engage in iterative problem-solving cycles. This approach enables students to learn to evaluate the effectiveness of their strategies, reflect on their decision-making processes, and adapt their methods based on feedback and new information [

56]. Therefore, students develop proficiency in solving marketing problems and cultivate broader cognitive skills such as analytical reasoning, creativity, and resilience through PBL. The opportunity to experience real-world marketing challenges enables students to learn to approach problems from multiple angles, think strategically, and make sound decisions under uncertainty [

57,

58]. These capabilities are particularly crucial given how fast-paced and competitive the marketing industry has become. Therefore, PBL empowers students to become agile problem solvers and critical thinkers, equipped to navigate the complexities of modern marketing and drive innovative solutions in their future careers.

4.3.4. Improved Decision-Making Capabilities

PBL in marketing education catalyzes improving students’ decision-making capabilities. Active engagement in real-world marketing problems encourages students to analyze information, evaluate alternatives, and make informed decisions [

15]. This process mirrors the decision-making procedures and challenges they will potentially encounter in their future marketing careers. Students enrolled in PBL programs learn to approach decision-making holistically, considering the immediate implications and long-term consequences of their actions [

59,

60]. Through iterative problem-solving cycles, students learn to assess risks, seek feedback, and adapt their strategies based on changing circumstances. This process fosters agility and resilience in decision-making [

61,

62]. They experience real-world implications of their decisions within a supportive learning environment, thereby gaining the confidence and competence to make sound judgments in their future marketing endeavors. Ultimately, PBL equips students with the skills and mindset needed to overcome challenges in marketing and make strategic decisions that drive business success [

63]. The improved decision-making capabilities through hands-on learning experiences empower them to become effective leaders and innovators in marketing.

4.3.5. Active Learning and Participation

PBL promotes active learning and participation by engaging students in meaningful, hands-on activities that encourage them to take ownership of their education. It requires students to engage with marketing problems actively, collaborate with peers, and apply critical thinking skills to solve real-world challenges [

29]. This promotes student-centered instruction by encouraging students to take an active role in their learning process. The self-directed inquiry and problem-solving activities contribute to their understanding and retention of knowledge [

64]. Moreover, students become more motivated, engaged, and invested in their learning. Thus, PBL empowers students to become active, lifelong learners who are well-prepared to succeed in their future marketing careers.

4.3.6. Opportunity for Community-Based Training

PBL programs allow students to engage with real-world stakeholders and apply marketing principles in authentic contexts beyond the classroom. Community-based training involves partnering with local businesses, nonprofit organizations, or community groups to address marketing challenges or opportunities, benefiting both students and the community [

28,

65]. PBL supports community-based training by integrating real-world projects and partnerships into the curriculum. This strategy provides students with hands-on experience and exposure to diverse marketing environments [

23]. For example, students might collaborate with local businesses to develop marketing strategies, conduct market research, or implement promotional campaigns. Working directly with community stakeholders provides practical insights into the unique challenges and opportunities facing businesses in the local area.

Community-based training in PBL promotes civic engagement and social responsibility by encouraging students to apply their marketing skills to address real societal issues. For instance, students might partner with nonprofit organizations or community groups to develop marketing campaigns for social causes or raise awareness about local issues [

24,

66]. These projects allow them to contribute positively to their communities while also gaining valuable experience in ethical marketing practices and social impact initiatives [

67]. In addition, community-based training provides students with networking opportunities and professional connections that can benefit their future careers [

65]. Interactions with local businesses, industry professionals, and community leaders expand their professional networks. They also create opportunities to gain insights into industry trends and access potential internships or job opportunities [

68]. This practical exposure to the marketing industry enhances students’ employability and prepares them for successful careers in marketing.

4.3.7. Improved Student Control

PBL increases students’ level of control over their learning process. In traditional lecture-based approaches, instructors dictate the pace and content of instruction. On the contrary, PBL empowers students to take ownership of their learning by actively engaging in problem-solving activities, setting learning goals, and directing their inquiry [

1]. In this case, PBL shifts the role of the instructor from a knowledge transmitter to a facilitator, providing guidance and support as students navigate through marketing challenges. Heiniö and Karjalainen [

69] argue that this student-centered approach allows learners to explore topics that align with their interests, strengths, and career aspirations. As a result, it establishes a sense of autonomy and motivation. Students have the flexibility to focus more on marketing areas that intrigue them, conduct independent research, and pursue projects that reflect their learning objectives.

Students in PBL programs could make decisions about how they approach and solve marketing problems. They can choose their research methods, select relevant resources, and determine the best strategies for addressing the challenges [

70]. This level of control enhances students’ sense of agency and promotes critical thinking and problem-solving skills as they learn to evaluate options and make informed decisions [

1]. Giving students control over their learning process through PBL programs promotes accountability and self-regulation [

71]. Students are responsible for managing their time, setting deadlines, and monitoring their progress. This results in self-directed professional marketers. The autonomy also builds a sense of ownership and commitment to learning, leading to greater engagement, satisfaction, and achievement.

4.3.8. Accommodation of Students’ Preferences for Different Instructional Methods

PBL programs are designed to accommodate students’ preferences for different instructional methods. They entail a diverse range of learning experiences tailored to individual needs and learning styles. Garver et al. [

13] found that these programs recognize that students have varying learning preferences and strengths, thus offering flexibility in how content is delivered and assessed. For instance, the PBL approach emphasizes active learning and experiential activities [

9]. This offers opportunities for students who prefer hands-on, practical learning experiences to engage in real-world marketing projects. Moreover, Alkhasawneh et al. [

72] explain that PBL incorporates various instructional methods to appeal to different learning styles. For example, visual learners may benefit from multimedia presentations, diagrams, and visual aids that help illustrate marketing concepts, while auditory learners may prefer lectures, podcasts, or discussions. Kinesthetic learners may thrive in interactive activities such as role-playing exercises or hands-on projects that involve physical manipulation and experimentation [

73]. Offering a mix of instructional methods in PBL programs ensures that students with diverse learning preferences can engage with the material in ways that resonate with them.

4.3.9. Multidisciplinary Student Projects and Teaching Approaches

PBL encourages multidisciplinary student projects and teaching approaches, thereby providing students with a holistic understanding of marketing concepts and their applications across various disciplines. This approach recognizes that marketing intersects with other areas, such as psychology, economics, sociology, technology, and design [

74]. It aims to promote collaboration and integration across these fields. Multidisciplinary student projects in PBL create an opportunity for students to explore diverse perspectives and insights from different disciplines [

69]. Collaborating with peers from various backgrounds provides exposure to alternative viewpoints and approaches to problem-solving, enhancing their learning experience, creativity and innovation [

75]. For example, a marketing project that incorporates insights from psychology may explore consumer behavior and decision-making processes. At the same time, one that integrates principles of economics may analyze market trends and pricing strategies.

Multidisciplinary teaching approaches in PBL allow instructors to use a wide range of resources and expertise to enhance student’s understanding of marketing concepts. In this regard, instructors may incorporate case studies, guest lectures, and real-world examples from other disciplines to illustrate key concepts and theories rather than relying solely on marketing textbooks and lectures [

76,

77]. For example, a marketing project on sustainability may involve input from environmental science experts, while one on digital marketing may incorporate insights from technology specialists. Besides, Heiniö and Karjalainen [

69] indicate that multidisciplinary student projects in PBL prepare students for the interconnected nature of the modern business world, where successful marketing strategies often require collaboration across departments and disciplines. Students who engage in these multidisciplinary projects develop valuable skills such as teamwork, communication, and adaptability.

4.4. Challenges Associated with PBL in Marketing Education

Implementing PBL in educational contexts can be associated with various obstacles that educators and institutions must navigate. For instance, the process of accommodating each student’s preferences and needs can be resource-intensive. Institutions with limited resources may struggle to provide adequate student-centric learning environments. Other issues identified in the research include information integrity issues, resistance, and inadequate instructor preparedness.

4.4.1. Information Integrity Issues

The potential for information integrity issues is a major issue in PBL. This approach relies heavily on real-world scenarios and external resources. This results in a higher risk of encountering inaccurate or outdated information that may undermine the validity of student learning outcomes [

78]. Students may struggle to discern credible sources from unreliable ones, leading to misconceptions or incomplete understandings of marketing concepts. Furthermore, the rapid changes and developments in the marketing industry mean that information can quickly become obsolete [

79]. This requires instructors to continuously update course materials and resources to ensure accuracy and relevance. Therefore, educators should guide evaluating sources and emphasize the importance of critical thinking and fact-checking skills [

80]. Students should learn to find and use reputable sources of information to support their learning objectives.

4.4.2. Student Resistance

Instructors and institutions implementing PBL in marketing education are likely to encounter student resistance, particularly among those accustomed to traditional forms of instruction. For example, Cunningham et al. [

9] found that 84% of participating students preferred PBL with small learning groups with tutors as facilitators. However, 14% of students still preferred more traditional teaching methods, including larger learning groups and tutors who taught didactically. Some students may find the open-ended nature of PBL projects daunting or may struggle with the required increased level of autonomy and responsibility [

81]. In addition, students may resist collaborating with peers or engaging in self-directed learning, preferring the structure and guidance provided by traditional lectures. Educators can reduce student resistance by effectively communicating the benefits of this approach, providing clear expectations and support structures, and creating a supportive learning environment where students feel empowered to take ownership of their learning.

4.4.3. Resource Intensive

Integrating PBL strategies into marketing curriculums can be resource-intensive, requiring significant time, effort, and resources to design and implement effective learning experiences. Developing authentic, real-world marketing projects, sourcing relevant case studies and resources, and facilitating group collaboration can all demand substantial investment from instructors and institutions [

82]. In addition, PBL may require access to specialized technology or software tools to support student learning, further increasing the resource requirements [

80]. Limited resources may pose challenges for educators, particularly those with heavy teaching loads or competing demands on their time. As a result, educators may need to collaborate with colleagues, leverage existing resources and materials, and seek support from institutional stakeholders to ensure the successful implementation of PBL initiatives in marketing education.

4.4.4. Inadequate Instructors Preparedness

Effective implementation of PBL requires instructors to possess a diverse skill set. These may include expertise in marketing concepts, instructional design, facilitation techniques, and assessment strategies [

76]. Some instructors may lack experience or training in PBL methodologies, leading to difficulties in designing and delivering engaging and effective learning experiences. Besides, instructors may struggle to adapt to the shift from a traditional lecture-based approach to a more facilitative role in PBL. As a result, Cunningham et al. [

9] indicate that they may require ongoing professional development and support to develop the necessary competencies. Education institutions should invest in faculty training and development programs. These should provide opportunities for instructors to learn about PBL methodologies, gain hands-on experience with implementing PBL projects, and receive feedback and support from experienced mentors or colleagues.

5. Conclusions

Problem-Based Learning (PBL) is an effective approach to ensuring that marketing students graduate with employable skills and knowledge. Its hands-on practice helps bridge the gap between employers’ expectations and the skills of new professionals. PBL encourages active student engagement, contrasting with traditional passive lecture-based formats. Educators using this approach employ various strategies, such as social media platforms for developing and testing marketing campaigns, serious games for simulating real-world activities, and e-learning platforms for resource accessibility. Feedback mechanisms and tools like Audience Response Systems (ARS) and User-Generated Content (UGC) further enhance engagement and learning experiences.

Implementing PBL programs offers numerous benefits, including hands-on experience, interactive collaboration, and the development of critical thinking and problem-solving skills. Students tackle real-world marketing challenges, collaborate with peers and industry experts, and hone decision-making and communication skills. PBL also supports community-based training, partnering with local businesses, NGOs, and other organizations, encouraging ethical professional practices. Unlike traditional setups, PBL gives students control over their learning, allowing them to set objectives and focus on topics of interest, enhancing engagement and satisfaction.

Most marketing PBL programs adopt a multidisciplinary approach, integrating concepts from various disciplines to deepen students’ understanding of marketing principles. Despite these benefits, challenges such as resource intensity, student resistance, and information integrity concerns can hinder PBL implementation. Educational institutions and educators must address these issues to optimize PBL programs effectively.

PBL emphasizes solving real-world problems to learn about a subject. In marketing, PBL mirrors the industry’s dynamic, problem-solving nature. It forces students to apply theoretical concepts to practical problems, enhancing understanding and adaptability. PBL involves teamwork, reflecting professional marketing environments, and includes real-life business problems, providing firsthand experience. The approach encourages reflection on the learning process, decision-making, and outcomes. With digital marketing’s rise, PBL incorporates digital tools and platforms, preparing students for modern challenges.

Future research in PBL for marketing should explore: (i) integrating technologies like AI, VR, and AR for immersive learning; (ii) tracking career trajectories of PBL students; (iii) adapting PBL for online and hybrid environments; (iv) integrating marketing with other disciplines like psychology and data science; and (v) developing new assessment methods for cognitive and practical skills gained through PBL. These areas will enhance the theoretical understanding and practical application of PBL, ensuring marketing education remains relevant and effective.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.T.R. and J.C.D.; methodology, A.T.R. and J.C.D.; software, A.T.R. and J.C.D.; validation, A.T.R. and J.C.D.; formal analysis, A.T.R. and J.C.D.; investigation, A.T.R. and J.C.D.; resources, A.T.R. and J.C.D.; data curation, A.T.R. and J.C.D.; writing—original draft preparation, A.T.R. and J.C.D.; writing—review and editing, A.T.R. and J.C.D.; visualization, A.T.R. and J.C.D.; supervision, A.T.R. and J.C.D.; project administration, A.T.R. and J.C.D.; funding acquisition, A.T.R. and J.C.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Th first author receives financial support from the Research Unit on Governance, Competitiveness and Public Policies (UIDB/04058/2020) + (UIDP/04058/2020), funded by national funds through FCT—Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, and the second receives financial support from FCT—Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia, through project UIDB/04005/2020.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to the Editor and the Referees. They offered valuable sug-gestions or improvements. The authors were supported by the GOVCOPP Research Center of the University of Aveiro and COMEGI—Centro de Investigação em Organizações, Mercados e Gestão Industrial of the Universidade Lusíada

Conflicts of Interest

The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Overview of document citations period ≤2014 to 2024.

Table A1.

Overview of document citations period ≤2014 to 2024.

| Documents |

|

≤2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

2023 |

2024 |

Total |

| (Feed Back as a Teaching Toei: lts lmpact on the Motivation ... |

2023 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

1 |

| Gender transformative advertising pedagogy: promoting gender. .. |

2023 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

2 |

1 |

3 |

| lmpact ofSerious Game Design Factors and Problem based Peda ... |

2022 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

2 |

2 |

| Developing a distinctive consulting capstone course in a sup ... |

2021 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

3 |

1 |

1 |

5 |

| Exploring a problem-based learning approach to improve the q ... |

2021 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

2 |

1 |

3 |

| Lab experience with seafood control at the undergraduate lev ... |

2020 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

2 |

- |

1 |

2 |

5 |

| Emerging MiningTrends: Preparing Future Mining Professional ... |

2020 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

1 |

1 |

- |

- |

3 |

| The practice research of flipped-classroorn combined mobile a ... |

2019 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

1 |

| A challenge based learning experience in forensic medicine |

2019 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

4 |

6 |

1 |

7 |

6 |

24 |

| Learning with Educational Robotics through Co-Creative Metho ... |

2019 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

2 |

| How Novices Use Expert Case Libraries for Problem Solving |

2019 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

4 |

1 |

4 |

- |

- |

10 |

| Teaching Geospatial Competences by Digital Activities and E- ... |

2019 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

| Rolling labs—Teaching vehicle electronics from the beginni ... |

2019 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

2 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

2 |

| (Massive open online course instructor motivations, innovati ... |

2019 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

4 |

5 |

4 |

2 |

|

15 |

| Using social media effectively in a surgical practice |

2016 |

- |

1 |

1 |

6 |

4 |

5 |

7 |

3 |

- |

- |

- |

27 |

| Are marketing students in control in problem-based learning? |

2016 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

2 |

- |

- |

3 |

| (Cases for teaching, problem-based learning and consulting: ... |

2016 |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

| Promoting Problem-Based Learning in Retailing and Services M ... |

2015 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

3 |

2 |

1 |

- |

- |

6 |

| Matters of taste: Bridging molecular physiology and the huma ... |

2015 |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

| A pharmacy business management sirnulation exercise as a prac ... |

2014 |

- |

12 |

1 |

- |

- |

1 |

3 |

3 |

1 |

- |

- |

13 |

| lnteractive Learning Activities for the Middle School Classr ... |

2014 |

3 |

|

1 |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

1 |

1 |

- |

- |

7 |

| Learning Context and Perceptions of Problem-Based Learning: ... |

2013 |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

2 |

| Problem-based service learning with a heart: Organizational ... |

2013 |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

3 |

1 |

6 |

| Theory to practice: Real-world case-based learning for manag ... |

2012 |

- |

- |

1 |

1 |

- |

- |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

- |

7 |

| (The ‘Ecosportech’ project as an example of entrepreneurial ... |

2012 |

2 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

2 |

| Promoting aclive learning using Audience Response System in ... |

2012 |

15 |

3 |

8 |

2 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

5 |

3 |

2 |

- |

50 |

| Work in progress—Does the marketing of engineering courses ... |

2011 |

|

1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

| Library and marketing class collaborate to create next gener ... |

2011 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

- |

- |

1 |

1 |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

7 |

| Evaluating community-based public health leadership training |

2011 |

3 |

- |

- |

3 |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

8 |

| A university, community coalition, and town partnership top ... |

2011 |

1 |

- |

1 |

1 |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

4 |

| Learning to maintain a proper relationship with the pharmace ... |

2010 |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

| Science communication reconsidered |

2009 |

76 |

19 |

13 |

20 |

25 |

27 |

37 |

34 |

31 |

26 |

9 |

317 |

| A review of problem-based (PBL) pedagogy approaches to engin ... |

2009 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

1 |

| Medical education and medical educators in South Asia -A se ... |

2009 |

4 |

2 |

2 |

- |

- |

2 |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

11 |

| Strategic marketing: Planning and control: Third edition |

2007 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

|

- |

- |

1 |

| Structured case analysis: Developing criticai thinking skill. .. |

2007 |

17 |

1 |

1 |

4 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

4 |

7 |

1 |

42 |

| Learning skills profiles of rnaster’s students in nursing adm ... |

2007 |

5 |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

7 |

| A discussion of refractive medical behavior from an experien ... |

2006 |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

| Modeling the problem-based learning preferences of McMaster ... |

2006 |

13 |

- |

- |

- |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

- |

21 |

| Teaching pharmacovigilance to medical students and doctors |

2006 |

9 |

1 |

1 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

5 |

1 |

- |

1 |

26 |

| Enhancing problem-solving expertise by means of an authentic ... |

2006 |

7 |

5 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

- |

1 |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

20 |

| Service scripts: A tool for teaching pharmacy students how t... |

2006 |

3 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

1 |

- |

5 |

| Transforming the Marketing Curriculum Using Problem-Based Le ... |

2003 |

25 |

1 |

2 |

4 |

- |

2 |

- |

2 |

2 |

5 |

- |

42 |

| Oregon State University’s Steer-a-Year program: lntegrating ... |

2002 |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

| Applying case methodology to teach pharmacy adrninistration e. .. |

2002 |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

3 |

| Cognitive effects of an authentic computer-supported, proble ... |

2002 |

32 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

2 |

- |

- |

2 |

2 |

- |

- |

56 |

| Teaching hands-on inventive problem solving |

2001 |

3 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

3 |

| (Promoting online collaborative learning experiences for tee ... |

2001 |

10 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

2 |

1 |

18 |

| Assuring integrity of information utility in cyber-learning ... |

1999 |

8 |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

10 |

| |

Total |

241 |

43 |

48 |

49 |

48 |

49 |

72 |

86 |

73 |

74 |

26 |

809 |

References

- Geitz, G., Brinke, D. J. T., & Kirschner, P. A. Are marketing students in control in problem-based learning? Cogent Education, 3, 2016 (1 C7—1222983). [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, M. S., Otalora, M. L., & Ramírez, G. C. Promoting problem-based learning in retailing and services marketing course curricula with reality television. Journal of Education for Business, 90(4), 2015, 182-191. [CrossRef]

- Nitisiri, K., Jamrus, T., Sethanan, K., Chetchotsak, D., & Nakrachata-Amon, T. Problem-Based Learning in Marketing Engineer Course: A Case Study from Industrial Engineering Curriculum. In Leveraging Transdisciplinary Engineering in a Changing and Connected World, 2023, (pp. 691-700). IOS Press. [CrossRef]

- Mardani, A. D., Dhewi, T. S., & Wardana, L. Comparison the Application of PBL (Project Based Learning) and PBL (Problem Based Learning) Learning Model on Online Marketing Subjects. Jurnal Pendidikan Bisnis dan Manajemen, 3(2), 2017, 97-106. [CrossRef]

- Rosário, A. T. & Dias, J. C. Marketing Strategies on Social Media Platforms. International Journal of E-Business Research (IJEBR), 19(1), 2023a, 1-25. [CrossRef]

- Rosário, A. & Dias, J. C. How has data-driven marketing evolved: Challenges and opportunities with emerging technologies. International Journal of Information Management Data Insights, 3(2), 2023b, 100203. [CrossRef]

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D.G. and Prisma Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS med, 6(7), 2009, p.e1000097. [CrossRef]

- Lisá, E., Hennelová, K., & Newman, D. Comparison between Employers’ and Students’ Expectations in Respect of Employability Skills of University Graduates. International Journal of Work-Integrated Learning, 20(1), 2019, 71-82.

- Cunningham, C. E., Deal, K., Neville, A., Rimas, H., & Lohfeld, L. Modeling the problem-based learning preferences of McMaster University undergraduate medical students using a discrete choice conjoint experiment. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 11(3), 2006, 245-266. [CrossRef]

- Araujo, M. V. P., de Araújo, A. G., & Brito, M. I. M. Cases for teaching, problem-based learning and consulting: Perception of students implementation of a pilot project in the course of management of UFRN—Brazil. International Symposium on Project Approaches in Engineering Education, 2016.

- Arts, J. A. R., Gijselaers, W. H., & Segers, M. S. R. Cognitive effects of an authentic computer-supported, problem-based learning environment. Instructional Science, 30, 2002, (6 C7—5098254), 465-495. [CrossRef]

- Antonoff, M. B. Using social media effectively in a surgical practice. Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, 151(2), 2016, 322-326. [CrossRef]

- Garver, M., Divine, R., & Dahlquist, S. Analysis of Gen Z marketing student preference for different instructional methods: An Abstract. In Developments in Marketing Science: Proceedings of the Academy of Marketing Science, 2022, (pp. 393-394). Springer Nature. [CrossRef]

- Chikatamarla, L., & Prasad, D. N. Emerging mining trends: Preparing future mining professionals. Learning and Analytics in Intelligent Systems, 2020.

- Correia, Anacleto, and Mário Simões-Marques, eds. Handbook of Research on Decision-Making Capabilities Improvement With Serious Games. Hershey, PA: IGI Global, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Gillani, F., Inayat, I., & Val De Carvalho, C. Impact of serious game design factors and problem-based pedagogy on learning outcome. Proceedings—2022 International Conference on Frontiers of Information Technology, FIT 2022, 2022.

- Delgado-Peña, J. J., & Subires-Mancera, M. P. (). Teaching geospatial competences by digital activities and e-learning. Experiences in Geography, Journalism, and Outdoor Education. In Key Challenges in Geograph,y 2019, (Vol. Part F2240, pp. 141-154). Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Vaz, L. M., & David, N. E-learning design issues for high-order learning—An application and empirical study in the knowledge domain of digital marketing. International Journal of Learning Technology, 14(3), 2019, 195-213. [CrossRef]

- Lin, S. M. The practice research of flipped-classroom combined mobile action learning in international marketing management course. ACM International Conference Proceeding Series, 2019.

- Monedero-Perales, M. C., Muñoz-Fernández, P., & Álvarez-Fuentes, J. Pharmaceutical management and planning: Implementation of PBL. Methodology implemented through group work. Ars Pharmaceutica, 2010.

- Huening, F., Hillgaertner, M., & Reke, M. Rolling labs—Teaching vehicle electronics from the beginning. International Journal of Engineering Pedagogy, 9(1), 2019, 34-49. [CrossRef]

- Armengol, J. V., Alcalde, I. H., Ibáñez, D. G., & Ferrer, S. E. Feed Back as a Teaching Tool: Its Impact on the Motivation of Higher Education Students. UCJC Business and Society Review, 20(76), 2023, 104-149. [CrossRef]

- Major, C. T., & Major, C. H. Learning context and perceptions of problem-based learning: A marketing course project at a community college. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 37(8), 2013, 620-628. [CrossRef]

- McDonald, S. Problem-based service learning with a heart: Organizational and student expectations and experiences in a postgraduate not-for-profit workshop event. Asia-Pacific Journal of Cooperative Education, 14(4), 2013, 281-293.

- Efstathiou, N., & Bailey, C. Promoting active learning using Audience Response System in large bioscience classes. Nurse Education Today, 32(1), 2012, 91-95. [CrossRef]

- Wood, R., & Shirazi, S. A systematic review of audience response systems for teaching and learning in higher education: The student experience. Computers & Education, 153, 2020, 103896.

- Eraña-Rojas, I. E., López Cabrera, M. V., Ríos Barrientos, E., & Membrillo-Hernández, J. A challenge-based learning experience in forensic medicine. Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine, 68, 2019, C7—101873. [CrossRef]

- Griffin, S. F., Williams, J. E., Hickman, P., Kirchner, A., & Spitler, H. A university, community coalition, and town partnership to promote walking. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice, 17(4), 2011, 358-362. [CrossRef]

- Ehrlick, S., Schwartz, N., & Slotta, J. Authentic experiences: How active learning and user-generated content can immerse university students in real life situations. IMSCI 2020—14th International Multi-Conference on Society, Cybernetics and Informatics, Proceedings, 2020.

- Baker, C. M., McDaniel, A. M., Pesut, D. J., & Fisher, M. L. Learning skills profiles of master’s students in nursing administration: Assessing the impact of problem-based learning. Nursing Education Perspectives, 28(4), 2007, 190-195.

- Holdford, D. Service scripts: A tool for teaching pharmacy students how to handle common practice situations. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 70, 2006, (1 C7—02). [CrossRef]

- Ramlo, S., Salmon, C., & Xue, Y. Student views of a PBL chemistry laboratory in a general education science course. Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-based Learning, 15(2), 2021. [CrossRef]

- Shankar, P. R., Subish, P., Mishra, P., & Dubey, A. K. Teaching pharmacovigilance to medical students and doctors. Indian Journal of Pharmacology, 38(5), 2006, 316-319. [CrossRef]

- Rollins, B. L., Gunturi, R., & Sullivan, D. A pharmacy business management simulation exercise as a practical application of business management material and principles. American journal of pharmaceutical education, 78(3), 2014, 62. [CrossRef]

- Rojter, J. Work in progress—Does the marketing of engineering courses through pedagogical differentiation matter? Proceedings—Frontiers in Education Conference, FIE, 2011, C7—6142887.

- Tawfik, A. A., Gill, A., Hogan, M., S. York, C., & Keene, C. W. How novices use expert case libraries for problem solving. Technology, Knowledge and Learning, 24(1), 2019, 23-40. [CrossRef]

- Roethlein, C. J., McCarthy Byrne, T. M., Visich, J. K., Li, S., & Gravier, M. J. Developing a distinctive consulting capstone course in a supply chain curriculum. Decision Sciences Journal of Innovative Education, 19(2), 2021, 117-128. [CrossRef]

- Simó Algado, S., De San Eugenio Vela, J., & Ginesta Portet, X. The ‘Ecosportech’ project as an example of entrepreneurial university. An experience based on the problem-based learning method. Estudios Sobre el Mensaje Periodistico, 18(SPEC. NOVEMBER), 2012, 869-877. [CrossRef]

- Siouli, S., Dratsiou, I., Antoniou, P. E., & Bamidis, P. D. Learning with educational robotics through co-creative methodologies. Interaction Design and Architecture(s), 42, 2019, 29-46.

- Reich-Stiebert, N., & Eyssel, F. (). Robots in the classroom: What teachers think about teaching and learning with education robots. In Social Robotics: 8th International Conference, ICSR 2016, Kansas City, MO, USA, November 1-3, 2016 Proceedings 8, 2016, (pp. 671-680). Springer International Publishing.

- Mubin, O., Stevens, C. J., Shahid, S., Al Mahmud, A., & Dong, J. J. (2013). A review of the applicability of robots in education. Journal of Technology in Education and Learning, 1(209-0015), 13.

- Werfel, J. Embodied teachable agents: Learning by teaching robots. In Intelligent Autonomous Systems, The 13th International Conference on, 2013.

- Theodosiou, M., Rennard, J. P., & Amir-Aslani, A. Theory to practice: Real-world case-based learning for management degrees. Nature Biotechnology, 30(9), 2012, 894-895. [CrossRef]

- Ackerman, C. J., Weber, D. W., & Dickson, R. L. Oregon State University’s Steer-a-Year program: Integrating classroom learning and hands-on experience. Journal of Animal Science, 80(10), 2002, 2764-2769. [CrossRef]

- Raviv, D. Teaching hands-on inventive problem solving. ASEE Annual Conference Proceedings, 2001.

- Rangachari, P. K., & Rangachari, U. Matters of taste: Bridging molecular physiology and the humanities. Advances in Physiology Education, 39(1), 2015, 288-294. [CrossRef]

- Ho, Y. C., Li, Y. C., & Su, T. H. A discussion of refractive medical behavior from an experiential marketing viewpoint. Journal of Hospital Marketing and Public Relations, 16(1-2), 2006, 45-68. [CrossRef]

- Fernández, S., Rodríguez-Muñiz, L. J., Molina, J., Muñiz-Rodríguez, L., Jiménez, J., García-Vázquez, E., & Borrell, Y. J. Lab experience with seafood control at the undergraduate level: Cephalopods as a case study. Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Education, 48(3), 2020, 236-246. [CrossRef]

- Brock, S., & Tabaei, S. Library and marketing class collaborate to create next generation learning landscape. Reference Services Review, 39(3), 2011, 362-368. [CrossRef]

- Wang, M., Poole, M., Harris, B., & Wangemann, P. Promoting online collaborative learning experiences for teenagers. Educational Media International, 38(4), 2001, 203-215. [CrossRef]

- Auer, M. E., Guralnick, D., & Simonics, I. (Eds.). Teaching and Learning in a Digital World: Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Interactive Collaborative Learning–Volume 1 (Vol. 715), 2017. Springer.

- . Rider, K., Kaya, H., Jha, V., & Hudmon, K. S. Attitudes of experiential education directors regarding tobacco sales in pharmacies in the USA. International Journal of Pharmacy Practice, 24(2), 2016, 134-138. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. H., Magjuka, R., Liu, X., & Bonk, C. J. Interactive technologies for effective collaborative learning. International Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning, 3(6), 2006, 17-32.

- Klebba, J. M., & Hamilton, J. G. Structured case analysis: Developing critical thinking skills in a Marketing Case Course. Journal of Marketing Education, 29(2), 2007, 132-139. [CrossRef]

- Arts, J. A. R., Gijselaers, W. H., & Segers, M. S. R. Enhancing problem-solving expertise by means of an authentic, collaborative, computer supported and problem-based course. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 21(1), 2006, 71-90. [CrossRef]

- Muniz, F., Geng, G., & Ganesh, G. G. Exploring a problem-based learning approach to improve the quantitative skills of marketing undergraduates. Journal for Advancement of Marketing Education, 29(1), 2021, 25-41.

- Drummond, G., Ensor, J., & Ashford, R. Strategic marketing: Planning and control: Third edition, 2007. Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Bubela, T., Nisbet, M. C., Borchelt, R., Brunger, F., Critchley, C., Einsiedel, E., Caulfield, T. Science communication reconsidered. Nature Biotechnology, 27(6), 2009, 514-518. [CrossRef]

- Rojter, J. A review of problem-based (PBL) pedagogy approaches to engineering education. ASEE Annual Conference and Exposition, Conference Proceedings, 2009.

- Coy, J. M., Ragai, I., Nozaki, S., & Bunce, K. Design, manufacturing, and finance—An interdisciplinary approach through engineering and business partnership. Manufacturing Letters, 33, 2022, 952-960. [CrossRef]

- Thabet, M., Taha, E. E. S., Abood, S. A., & Morsy, S. R. The effect of problem-based learning on nursing students’ decision making skills and styles. Journal of Nursing Education and Practice, 7(6), 2017, 108-116.

- Geitz, G., Joosten-ten Brinke, D., & Kirschner, P. A. Are marketing students in control in problem-based learning?. Cogent Education, 3(1), 2016, 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Nango, E., & Tanaka, Y. Problem-based learning in a multidisciplinary group enhances clinical decision making by medical students: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of medical and dental sciences, 57(1), 2010, 109-118.

- Venditti, E. M., Giles, C., Firrell, L. S., Zeveloff, A. D., Hirst, K., & Marcus, M. D. Interactive learning activities for the middle school classroom to promote healthy energy balance and decrease diabetes risk in the HEALTHY primary prevention trial. Health Promotion Practice, 15(1), 2014, 55-62. [CrossRef]

- Ceraso, M., Gruebling, K., Layde, P., Remington, P., Hill, B., Morzinski, J., & Ore, P. Evaluating community-based public health leadership training. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice, 17(4), 2011, 344-349. [CrossRef]

- Quintero Romero, S., & Arendt, M. Sofia Quintero Romero: Protection and support of breastfeeding with a feminist and social justice lens. Journal of Human Lactation, 39(4), 2023, 573-578. [CrossRef]

- Gurrieri, L., & Finn, F. Gender transformative advertising pedagogy: Promoting gender justice through marketing education. Journal of Marketing Management, 39(1-2), 2023, 108-133. [CrossRef]

- Shankar, P. R., Jha, N., Bajracharya, O., & Piryani, R. M. Learning to maintain a proper relationship with the pharmaceutical industry. Medical Teacher, 32(2), 2010, 183-184. [CrossRef]

- Heiniö, S., & Karjalainen, T. M. Multidisciplinary student project as a teaching platform for package design. 17th IAPRI World Conference on Packaging 2010.

- Stefanou, C., Stolk, J. D., Prince, M., Chen, J. C., & Lord, S. M. Self-regulation and autonomy in problem-and project-based learning environments. Active Learning in Higher Education, 14(2), 2013, 109-122.

- Suastra, I. W., Suarni, N. K., & Dharma, K. S. The effect of Problem Based Learning (PBL) model on elementary school students’ science higher order thinking skill and learning autonomy. In Journal of Physics: Conference Series (Vol. 1318, No. 1, p. 012084), 2019. IOP Publishing.

- Alkhasawneh, I. M., Mrayyan, M. T., Docherty, C., Alashram, S., & Yousef, H. Y. Problem-based learning (PBL): Assessing students’ learning preferences using VARK. Nurse education today, 28(5), 2008, 572-579.

- . Tyas, P. A., & Safitri, M. Kinesthetic learning style preferences: A survey of Indonesian EFL learners by gender. JEES (Journal of English Educators Society), 2(1), 2017, 53-64. [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, P., Reifschneider, L., & Langrehr, F. A Multidisciplinary Approach to Teaching the Marketing of Sustainable Products. Journal of Sustainability Education, 2011.

- Will, F. Value based learning—A new learning framework to create economic value during the learning process. FISITA 2014 World Automotive Congress—Proceedings, 2014.

- Zhu, M., Bonk, C. J., & Sari, A. R. Massive open online course instructor motivations, innovations, and designs: Surveys, interviews, and course reviews. Canadian Journal of Learning and Technology, 45(1), 2019. [CrossRef]

- Wee, L. K. N., Alexandria, M., Kek, Y. C., & Kelley, C. A. Transforming the marketing curriculum using problem-based learning: A case study. Journal of Marketing Education, 25(2), 2003, 150-162. [CrossRef]

- de Araújo, M. V. P., de Araújo, A. G., & Brito, M. I. D. M. Constrains and challenges of learning experience with problem-based learning: A pilot study in the perception of students of the marketing discipline of the course of administration of the Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte –UFRN. International Symposium on Project Approaches in Engineering Education, 2018.

- Morrison, J. L., & Stein, L. L. Assuring integrity of information utility in cyber-learning formats. Reference Services Review, 27(4), 1999, 317-326. [CrossRef]

- To, C. K. M., Chan, S. F., & Li, B. S. W. A problem-based learning system. Textile Asia, 33(6), 2002, 51-53.

- Harun, N. F., Yusof, K. M., Jamaludin, M. Z., & Hassan, S. A. H. S. Motivation in problem-based learning implementation. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 56, 2012, 233-242.

- Uden, L., & Page, T. Development of Learning Resources to Promote Knowledge Sharing in Problem Based Learning. Journal of Educational Technology, 5(1), 2008, 15-22.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |