Submitted:

17 June 2024

Posted:

18 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

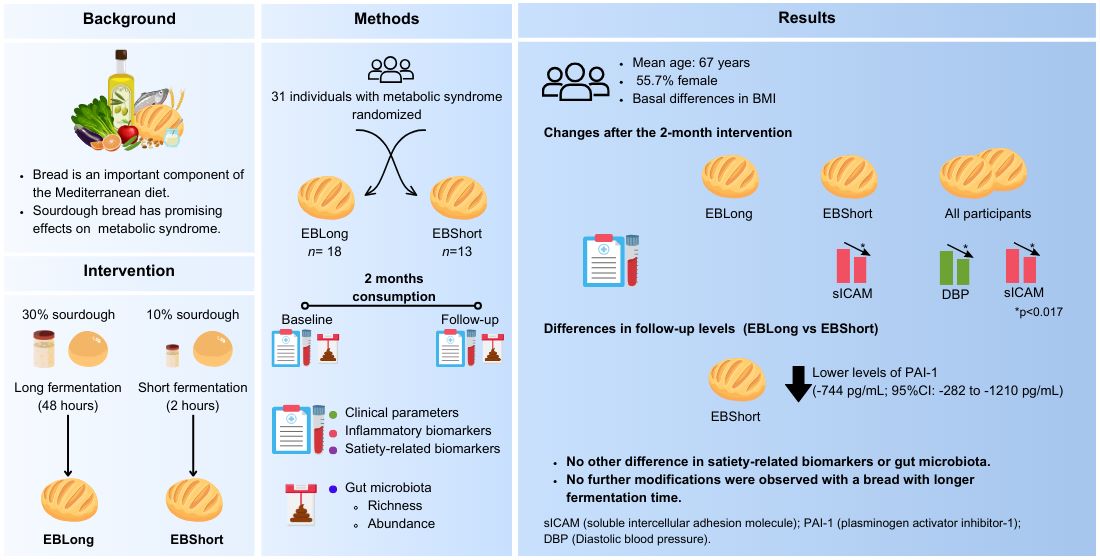

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

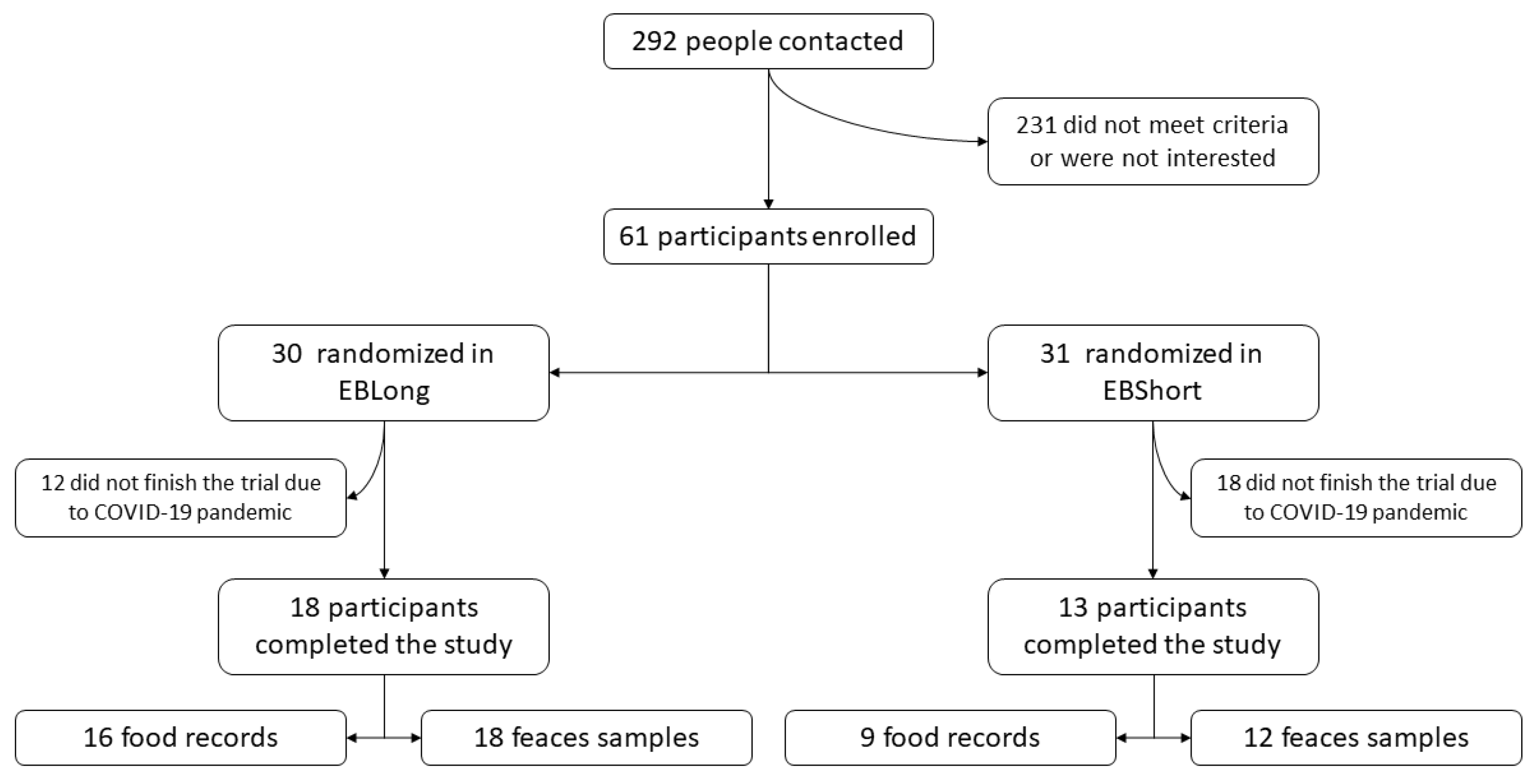

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Ethical Aspects

2.3. Bread Composition and Fermentation Process

2.4. General and Life-Style Data

2.5. Anthropometric and Exploration Data

2.6. Laboratory Analysis

2.7. Intestinal Microbiota Analysis

2.8. Bioinformatic Analysis

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

| All | EBLong | EBShort | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 31 | 18 | 13 | |

| Age, mean (SD) | 66.7 (5.94) | 66.6 (7.04) | 66.8 (4.36) | 0.954 |

| Sex, Female, n (%) | 16 (51.6%) | 8 (44.4%) | 8 (61.5%) | 0.565 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 26 (83.9%) | 17 (94.4%) | 9 (69.2%) | 0.134 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 30 (96.8%) | 18 (100%) | 12 (92.3%) | 0.419 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL, median [1st-3rd quartile] | 142 [90.5;174] | 146 [90.0;168] | 139 [92.0;175] | 0.889 |

| HDLc, mg/dL, mean (SD) | 49.0 (11.7) | 50.3 (11.8) | 47.2 (11.7) | 0.475 |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean (SD) | 32.8 (3.26) | 34.1 (2.84) | 31.2 (3.13) | 0.015 |

| Scholarity | 0.895 | |||

| Elementary School | 13 (43.3%) | 7 (38.9%) | 6 (50.0%) | |

| Middle school | 9 (30.0%) | 6 (33.3%) | 3 (25.0%) | |

| Higher education | 8 (26.7%) | 5 (27.8%) | 3 (25.0%) | |

| Smoking habit | 0.634 | |||

| Non smoker | 13 (41.9%) | 9 (50.0%) | 4 (30.8%) | |

| Smoker | 5 (16.1%) | 2 (11.1%) | 3 (23.1%) | |

| Former smoker | 13 (41.9%) | 7 (38.9%) | 6 (46.2%) | |

| Adherence to MedDiet (14pt), points, mean (SD) | 9.71 (2.18) | 9.83 (2.07) | 9.54 (2.40) | 0.724 |

| Basal intake, kcal, mean (SD) | 1558 (345) | 1552 (387) | 1567 (291) | 0.900 |

| Physical activity, Mets/day, mean (SD) | 2502 (1885) | 2320 (1632) | 2753 (2234) | 0.560 |

3.1. Dietetic Assesment

3.2. Sourdough Bread Intervention

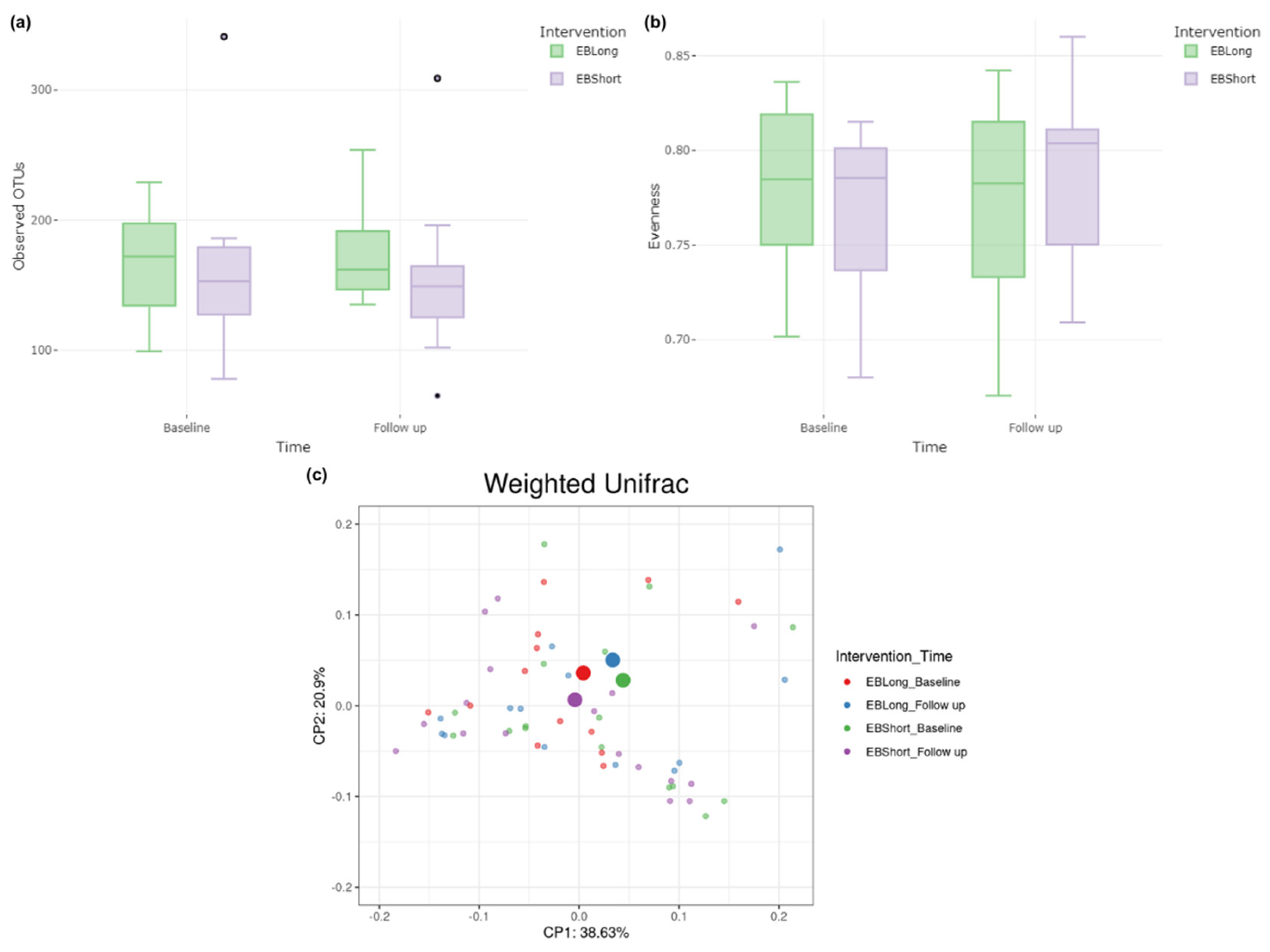

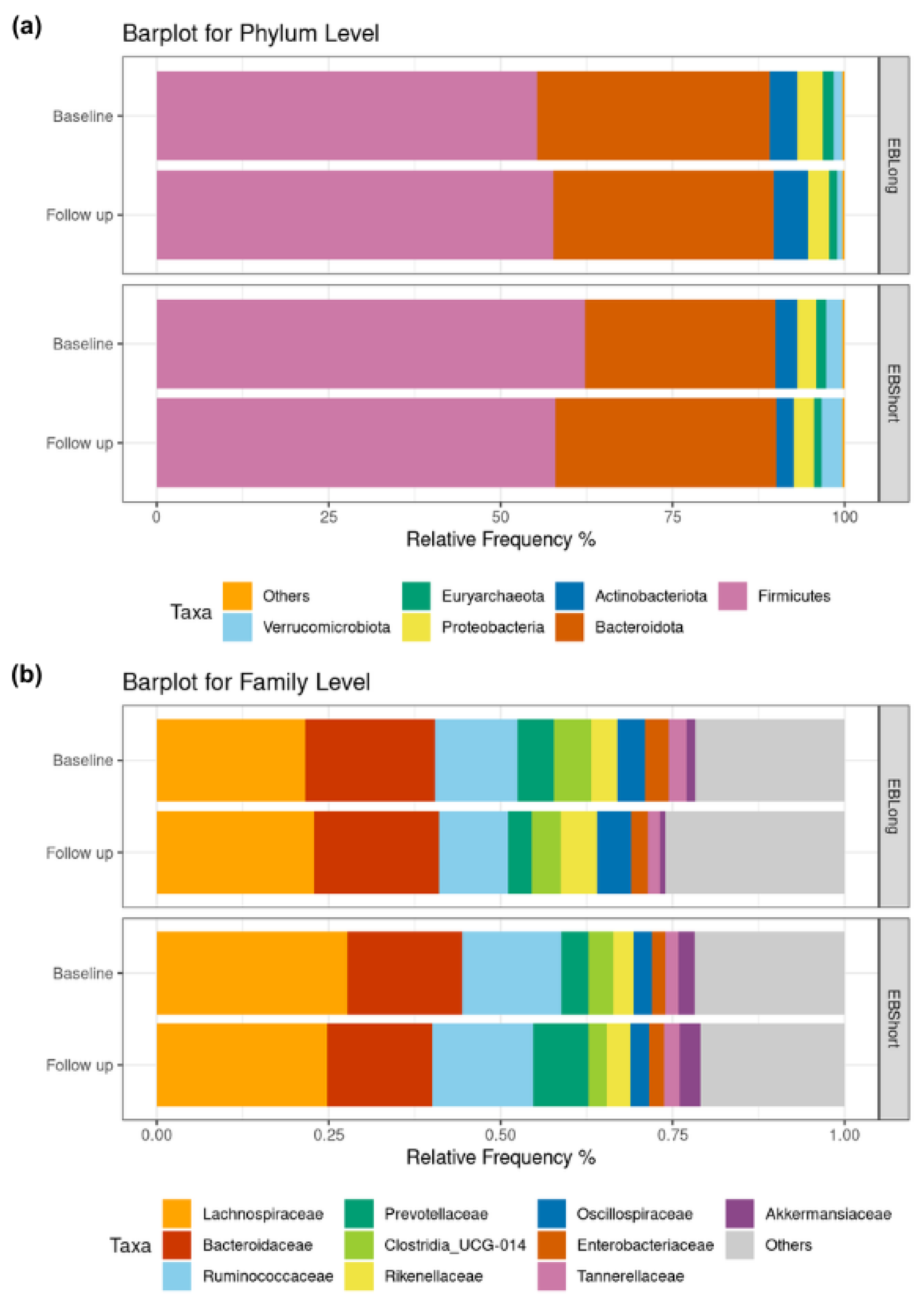

3.3. Microbiota Characterization

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shin, J.A.; Lee, J.H.; Lim, S.Y.; Ha, H.S.; Kwon, H.S.; Park, Y.M.; Lee, W.C.; Kang, M. Il; Yim, H.W.; Yoon, K.H.; et al. Metabolic Syndrome as a Predictor of Type 2 Diabetes, and Its Clinical Interpretations and Usefulness. J Diabetes Investig 2013, 4, 334–343. [CrossRef]

- Galassi, A.; Reynolds, K.; He, J. Metabolic Syndrome and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease: A Meta-Analysis. Am J Med 2006, 119, 812–819. [CrossRef]

- Alberti, K.G.M.M.; Eckel, R.H.; Grundy, S.M.; Zimmet, P.Z.; Cleeman, J.I.; Donato, K.A.; Fruchart, J.C.; James, W.P.T.; Loria, C.M.; Smith, S.C. Harmonizing the Metabolic Syndrome: A Joint Interim Statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; And International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation 2009, 120, 1640–1645. [CrossRef]

- Rippe, J.M. Lifestyle Strategies for Risk Factor Reduction, Prevention, and Treatment of Cardiovascular Disease. Am J Lifestyle Med 2019, 13, 204–212. [CrossRef]

- Estruch, R.; Ros, E.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Covas, M.-I.; Corella, D.; Arós, F.; Gómez-Gracia, E.; Ruiz-Gutiérrez, V.; Fiol, M.; Lapetra, J.; et al. Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease with a Mediterranean Diet Supplemented with Extra-Virgin Olive Oil or Nuts. N Engl J Med. 2018, 378, e34. [CrossRef]

- Esposito, K.; Kastorini, C.M.; Panagiotakos, D.B.; Giugliano, D. Mediterranean Diet and Metabolic Syndrome: An Updated Systematic Review. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 2013, 14, 255–263. [CrossRef]

- Capurso, A.; Capurso, C. The Mediterranean Way: Why Elderly People Should Eat Wholewheat Sourdough Bread—a Little Known Component of the Mediterranean Diet and Healthy Food for Elderly Adults. Aging Clin Exp Res 2020, 32, 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Arendt, E.K.; Ryan, L.A.M.; Dal Bello, F. Impact of Sourdough on the Texture of Bread. Food Microbiol 2007, 24, 165–174. [CrossRef]

- Olagnero, G.; Abad, A.; Bendersky, S.; Genevois, C.; Granzella, L.; Montonati, M. Alimentos Funcionales: Fibra, Prebióticos, Probióticos y Simbióticos. Diaeta 2007, 25, 20–33.

- Akamine, I.T.; Mansoldo, F.R.P.; Vermelho, A.B. Probiotics in the Sourdough Bread Fermentation: Current Status. Fermentation 2023, 9, 90. [CrossRef]

- Lluansí, A.; Llirós, M.; Oliver, L.; Bahí, A.; Elias-Masiques, N.; Gonzalez, M.; Benejam, P.; Cueva, E.; Termes, M.; Ramió-Pujol, S.; et al. In Vitro Prebiotic Effect of Bread-Making Process in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Microbiome. Front Microbiol 2021, 12, 716307. [CrossRef]

- Schröder, H.; Fitó, M.; Estruch, R.; Martínez-González, M.A.; Corella, D.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.; Ros, E.; Salaverría, I.; Fiol, M.; et al. A Short Screener Is Valid for Assessing Mediterranean Diet Adherence among Older Spanish Men and Women. J Nutr. 2011, 141, 1140–1145. [CrossRef]

- Cantós López, D.; Farran, A.; Palma Linares, I. Programa de Càlcul Nutricional Professional (PCN Pro) 2013.

- Molina, L.; Sarmiento, M.; Peñafiel, J.; Donaire, D.; Garcia-Aymerich, J.; Gomez, M.; Ble, M.; Ruiz, S.; Frances, A.; Schröder, H.; et al. Validation of the Regicor Short Physical Activity Questionnaire for the Adult Population. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0168148. [CrossRef]

- Klindworth, A.; Pruesse, E.; Schweer, T.; Peplies, J.; Quast, C.; Horn, M.; Glöckner, F.O. Evaluation of General 16S Ribosomal RNA Gene PCR Primers for Classical and Next-Generation Sequencing-Based Diversity Studies. Nucleic Acids Res 2013, 41, e1. [CrossRef]

- Bolyen, E.; Rideout, J.R.; Dillon, M.R.; Bokulich, N.A.; Abnet, C.C.; Al-Ghalith, G.A.; Alexander, H.; Alm, E.J.; Arumugam, M.; Asnicar, F.; et al. Reproducible, Interactive, Scalable and Extensible Microbiome Data Science Using QIIME 2. Nat Biotechnol 2019, 37, 852–857. [CrossRef]

- Callahan, B.J.; McMurdie, P.J.; Rosen, M.J.; Han, A.W.; Johnson, A.J.A.; Holmes, S.P. DADA2: High-Resolution Sample Inference from Illumina Amplicon Data. Nat Methods 2016, 13, 581–583. [CrossRef]

- Katoh, K.; Standley, D.M. MAFFT Multiple Sequence Alignment Software Version 7: Improvements in Performance and Usability. Mol Biol Evol 2013, 30, 772–780. [CrossRef]

- Price, M.N.; Dehal, P.S.; Arkin, A.P. FastTree 2—Approximately Maximum-Likelihood Trees for Large Alignments. PLoS One 2010, 5. [CrossRef]

- Lozupone, C.; Lladser, M.E.; Knights, D.; Stombaugh, J.; Knight, R. UniFrac: An Effective Distance Metric for Microbial Community Comparison. ISME J 5 2011, 5, 169–172. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Garrity, G.M.; Tiedje, J.M.; Cole, J.R. Naïve Bayesian Classifier for Rapid Assignment of RRNA Sequences into the New Bacterial Taxonomy. Appl Environ Microbiol 2007, 73, 5261–5267. [CrossRef]

- Pruesse, E.; Quast, C.; Knittel, K.; Fuchs, B.M.; Ludwig, W.; Peplies, J.; Glöckner, F.O. SILVA: A Comprehensive Online Resource for Quality Checked and Aligned Ribosomal RNA Sequence Data Compatible with ARB. Nucleic Acids Res 2007, 35, 7188–7196. [CrossRef]

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V.; et al. Scikit-Learn: Machine Learning in Python. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2011, 12, 2825–2830.

- R Core Team R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing.

- Zhang, X.; Yi, N. NBZIMM: Negative Binomial and Zero-Inflated Mixed Models, with Application to Microbiome/Metagenomics Data Analysis. BMC Bioinformatics 2020, 21, 488. [CrossRef]

- Cribari-Neto, F.; Zeileis, A. Beta Regression in R. J Stat Softw 2010, 34, 1–24. [CrossRef]

- Pagliai, G.; Venturi, M.; Dinu, M.; Galli, V.; Colombini, B.; Giangrandi, I.; Maggini, N.; Sofi, F.; Granchi, L. Effect of Consumption of Ancient Grain Bread Leavened with Sourdough or with Baker’s Yeast on Cardio-Metabolic Risk Parameters: A Dietary Intervention Trial. Int J Food Sci Nutr 2021, 72, 367–374. [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Kaur, R.; Kumari, P.; Pasricha, C.; Singh, R. ICAM-1 and VCAM-1: Gatekeepers in Various Inflammatory and Cardiovascular Disorders. Clinica Chimica Acta 2023, 548, 117487. [CrossRef]

- Seidel, C.; Boehm, V.; Vogelsang, H.; Wagner, A.; Persin, C.; Glei, M.; Pool-Zobel, B.L.; Jahreis, G. Influence of Prebiotics and Antioxidants in Bread on the Immune System, Antioxidative Status and Antioxidative Capacity in Male Smokers and Non-Smokers. Br J Nutr 2007, 97, 349–356. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.C.; Chow, M.P.; Huang, W.C.; Lin, Y.C.; Chang, Y.J. Flavonoids Inhibit Tumor Necrosis Factor-α-Induced up-Regulation of Intercellular Adhesion Molecule-1 (ICAM-1) in Respiratory Epithelial Cells through Activator Protein-1 and Nuclear Factor-ΚB: Structure-Activity Relationships. Mol Pharmacol 2004, 66, 683–693.

- Jahreis, G.; Vogelsang, H.; Kiessling, G.; Schubert, R.; Bunte, C.; Hammes, W.P. Influence of Probiotic Sausage (Lactobacillus Paracasei) on Blood Lipids and Immunological Parameters of Healthy Volunteers. Food Res Int 2002, 35, 133–138. [CrossRef]

- Tjärnlund-Wolf, A.; Brogren, H.; Lo, E.H.; Wang, X. Plasminogen Activator Inhibitor-1 and Thrombotic Cerebrovascular Diseases. Stroke 2012, 43, 2833–2839. [CrossRef]

- MacKay, K.A.; Tucker, A.J.; Duncan, A.M.; Graham, T.E.; Robinson, L.E. Whole Grain Wheat Sourdough Bread Does Not Affect Plasminogen Activator Inhibitor-1 in Adults with Normal or Impaired Carbohydrate Metabolism. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2012, 22, 704–711. [CrossRef]

- Tucker, A.J.; MacKay, K.A.; Robinson, L.E.; Graham, T.E.; Bakovic, M.; Duncan, A.M. The Effect of Whole Grain Wheat Sourdough Bread Consumption on Serum Lipids in Healthy Normoglycemic/Normoinsulinemic and Hyperglycemic/Hyperinsulinemic Adults Depends on Presence of the APOE E3/E3 Genotype: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutr Metab 2010, 7, 37. [CrossRef]

- Gabriele, M.; Arouna, N.; Árvay, J.; Longo, V.; Pucci, L. Sourdough Fermentation Improves the Antioxidant, Antihypertensive, and Anti-Inflammatory Properties of Triticum Dicoccum. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 6283. [CrossRef]

- Ayyash, M.; Johnson, S.K.; Liu, S.Q.; Mesmari, N.; Dahmani, S.; Al Dhaheri, A.S.; Kizhakkayil, J. In Vitro Investigation of Bioactivities of Solid-State Fermented Lupin, Quinoa and Wheat Using Lactobacillus Spp. Food Chem 2019, 275, 50–58. [CrossRef]

- Rolim, M.E.; Fortes, M.I.; Von Frankenberg, A.; Duarte, C.K. Consumption of Sourdough Bread and Changes in the Glycemic Control and Satiety: A Systematic Review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2022, 801–816. [CrossRef]

- Iversen, K.N.; Johansson, D.; Brunius, C.; Andlid, T.; Andersson, R.; Langton, M.; Landberg, R. Appetite and Subsequent Food Intake Were Unaffected by the Amount of Sourdough and Rye in Soft Bread—A Randomized Cross-over Breakfast Study. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1594. [CrossRef]

- Darzi, J.; Frost, G.S.; Robertson, M.D. Effects of a Novel Propionate-Rich Sourdough Bread on Appetite and Food Intake. Eur J Clin Nutr 2012, 66, 789–794. [CrossRef]

- Zamaratskaia, G.; Johansson, D.P.; Junqueira, M.A.; Deissler, L.; Langton, M.; Hellström, P.M.; Landberg, R. Impact of Sourdough Fermentation on Appetite and Postprandial Metabolic Responses-A Randomised Cross-over Trial with Whole Grain Rye Crispbread. Br J Nutr 2017, 118, 686–697. [CrossRef]

- Najjar, A.M.; Parsons, P.M.; Duncan, A.M.; Robinson, L.E.; Yada, R.Y.; Graham, T.E. The Acute Impact of Ingestion of Breads of Varying Composition on Blood Glucose, Insulin and Incretins Following First and Second Meals. Br J Nutr 2009, 101, 391–398. [CrossRef]

- Bo, S.; Seletto, M.; Choc, A.; Ponzo, V.; Lezo, A.; Demagistris, A.; Evangelista, A.; Ciccone, G.; Bertolino, M.; Cassader, M.; et al. The Acute Impact of the Intake of Four Types of Bread on Satiety and Blood Concentrations of Glucose, Insulin, Free Fatty Acids, Triglyceride and Acylated Ghrelin. A Randomized Controlled Cross-over Trial. Food Res Int 2017, 92, 40–47. [CrossRef]

- Lluansí, A.; Llirós, M.; Carreras-Torres, R.; Bahí, A.; Capdevila, M.; Feliu, A.; Vilà-Quintana, L.; Elias-Masiques, N.; Cueva, E.; Peries, L.; et al. Impact of Bread Diet on Intestinal Dysbiosis and Irritable Bowel Syndrome Symptoms in Quiescent Ulcerative Colitis: A Pilot Study. PLoS One 2024, 19, e0297836. [CrossRef]

- Korem, T.; Zeevi, D.; Zmora, N.; Weissbrod, O.; Bar, N.; Lotan-Pompan, M.; Avnit-Sagi, T.; Kosower, N.; Malka, G.; Rein, M.; et al. Bread Affects Clinical Parameters and Induces Gut Microbiome-Associated Personal Glycemic Responses. Cell Metab 2017, 25, 1243-1253.e5. [CrossRef]

- Marchandin, H.; Damay, A.; Roudière, L.; Teyssier, C.; Zorgniotti, I.; Dechaud, H.; Jean-Pierre, H.; Jumas-Bilak, E. Phylogeny, Diversity and Host Specialization in the Phylum Synergistetes with Emphasis on Strains and Clones of Human Origin. Res Microbiol 2010, 161. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, M.Y.; Inohara, N.; Nuñez, G. Mechanisms of Inflammation-Driven Bacterial Dysbiosis in the Gut. Mucosal Immunol 2017, 10. [CrossRef]

- Konikoff, T.; Gophna, U. Oscillospira: A Central, Enigmatic Component of the Human Gut Microbiota. Trends Microbiol 2016, 24. [CrossRef]

- Duan, M.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Zou, R.; Guo, M.; Zheng, H. Characteristics of Gut Microbiota in People with Obesity. PLoS One 2021, 16. [CrossRef]

| EBLong | EBShort | All | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Follow up | p Value | Baseline | Follow up | p Value | Baseline | Follow up | p Value | |

| Weight, kg | 92.9 (14.7) | 93.4 (14.3) | 0.710 | 84 (10.2) | 83.5 (9.5) | 0.415 | 89.1 (13.5) | 89.1 (13.2) | 0.462 |

| Waist, cm | 119 (17.3) | 114 (12.5) | 0.237 | 111 (10.3) | 110 (9.18) | 0.796 | 115 (15.1) | 112 (11.2) | 0.223 |

| Systolic pressure, mmHg | 136 (11.3) | 132 (14.5) | 0.470 | 134 (10.1) | 135 (9.91) | 0.395 | 135 (10.7) | 134 (12.6) | 0.830 |

| Diastolic pressure, mmHg | 80.2 (12.2) | 72.5 (10.2) | 0.020 | 77.6 (12.7) | 72.7 (11.3) | 0.208 | 79.1 (12.2) | 72.6 (10.5) | 0.008 |

| Glucose, mg/dL | 125 (30.7) | 128 (33.2) | 0.162 | 117 (23.8) | 117 (21.9) | 0.967 | 122 (27.8) | 124 (29.2) | 0.318 |

| Insulin, pg/mL | 423 (201) | 388 (168) | 0.067 | 484 (282) | 490 (287) | 0.797 | 449 (236) | 431 (227) | 0.241 |

| Glucagon, pg/mL | 520 (188) | 493 (177) | 0.143 | 541 (117) | 539 (180) | 0.949 | 529 (160) | 512 (177) | 0.376 |

| Homa Index | 18.2 (7.97) | 17.3 (7.43) | 0.286 | 21.2 (15.6) | 21 (13.8) | 0.890 | 19.5 (11.7) | 18.8 (10.5) | 0.431 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 146 [90; 168] | 130 [91; 158] | 0.862 | 139 [92; 175] | 124 [84; 179] | 0.839 | 139 [92; 175] | 124 [84; 179] | 0.814 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 199 (39.5) | 202 (38.6) | 0.378 | 189 (38.9) | 192 (56.3) | 0.707 | 195 (39) | 198 (46.3) | 0.444 |

| HDLc, mg/dL | 50.3 (11.8) | 50.6 (11.7) | 0.736 | 47.2 (11.7) | 48.7 (15.4) | 0.263 | 49 (11.7) | 49.8 (13.1) | 0.282 |

| LDLc, mg/dL | 120 (28.6) | 125 (35.1) | 0.123 | 115 (33.1) | 115 (44.2) | 0.918 | 118 (30.2) | 121 (38.8) | 0.314 |

| C-peptide, pg/mL | 1100 (423) | 1050 (358) | 0.389 | 1190 (511) | 1190 (613) | 0.940 | 1140 (457) | 1110 (481) | 0.618 |

| Ghrelin, pg/mL | 902 (297) | 904 (274) | 0.952 | 1180 (777) | 1130 (622) | 0.444 | 1020 (558) | 998 (458) | 0.531 |

| Leptin, pg/mL | 8920 (5110) | 8540 (5430) | 0.434 | 9170 (4680) | 9120 (4910) | 0.897 | 9020 (4850) | 8780 (5140) | 0.451 |

| GLP1, pg/mL | 164 (97.8) | 165 (111) | 0.960 | 187 (125) | 223 (122) | 0.191 | 174 (109) | 189 (118) | 0.304 |

| IL6, pg/mL | 2.4 (1.73) | 3.06 (1.93) | 0.106 | 2.5 (1.5) | 2.14 (1.08) | 0.350 | 2.44 (1.62) | 2.67 (1.67) | 0.426 |

| IL8, pg/mL | 4.49 (2.21) | 3.86 (2.02) | 0.116 | 4.63 (2.78) | 4.4 (2.04) | 0.563 | 4.55 (2.42) | 4.09 (2.02) | 0.099 |

| Resistin, pg/mL | 4320 (1720) | 4360 (1310) | 0.883 | 6260 (3020) | 5630 (2240) | 0.339 | 5130 (2510) | 4890 (1840) | 0.445 |

| TNF a, pg/mL | 29.6 (9.59) | 29.9 (11.8) | 0.898 | 40.7 (15.4) | 35.5 (12.4) | 0.032 | 34.2 (13.3) | 32.2 (12.2) | 0.246 |

| PAI-1, pg/mL | 2740 (1070) | 2840 (999) | 0.466 | 2750 (529) | 2330 (773) | 0.018 | 2740 (872) | 2630 (933) | 0.318 |

| Visfatin, pg/mL | 1910 (1310) | 1730 (1380) | 0.133 | 2030 (1440) | 1990 (1400) | 0.887 | 1960 (1340) | 1840 (1370) | 0.364 |

| sICAM, pg/mL | 179000 (67500) | 170000 (41800) | 0.325 | 192000 (59300) | 160000 (39200) | 0.013 | 184000 (63500) | 166000 (40300) | 0.014 |

| LBP, ng/mL | 15100 (2630) | 16500 (4370) | 0.095 | 14200 (3820) | 13900 (3690) | 0.761 | 14700 (3160) | 15400 (4230) | 0.259 |

| EBLong vs EBShort | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Adjusted $(diff. [95% CI]) | p Value | Adjusted $(diff. [95% CI]) | p Value | |

| Weight, kg | 9.82 [0.47; 19.2] | 0.050 | -0.2 [-2.03; 1.62] | 0.829 |

| Waist, cm | 4.49 [-3.89; 12.9] | 0.303 | -4.46 [-9.22; 0.3] | 0.082 |

| Systolic pressure, mmHg | -3.16 [-12.7; 6.38] | 0.522 | -11.6 [-21.1; -2.12] | 0.026 |

| Diastolic pressure, mmHg | -0.18 [-8.17; 7.81] | 0.966 | -6.43 [-14.6; 1.76] | 0.140 |

| Glucose, mg/dL | 11.3 [-9.48; 32] | 0.296 | 5.71 [-4.76; 16.2] | 0.296 |

| Insulin, pg/mL | -102 [-262; 58.8] | 0.224 | -22 [-91.9; 47.9] | 0.543 |

| Glucagon, pg/mL | -46.3 [-173; 80.7] | 0.480 | -2.05 [-96.7; 92.6] | 0.966 |

| Homa Index | -3.64 [-11.2; 3.9] | 0.352 | 0.31 [-3.05; 3.67] | 0.858 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | -9.53 [-53.2; 34.1] | 0.672 | -33.3 [-66.6; -0.086] | 0.062 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 10.2 [-23.2; 43.5] | 0.554 | -4.44 [-25.3; 16.4] | 0.681 |

| HDLc Cholesterol | 1.87 [-7.65; 11.4] | 0.703 | -1.49 [-4.9; 1.91] | 0.399 |

| LDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 10.2 [-17.7; 38.1] | 0.479 | 2.03 [-16.1; 20.2] | 0.829 |

| C-peptide, pg/mL | -149 [-498; 200] | 0.411 | 50.4 [-205; 306] | 0.703 |

| Ghrelin, pg/mL | -225 [-548; 97.1] | 0.181 | -45.4 [-163; 72.1] | 0.457 |

| Leptin, pg/mL | -584 [-4310; 3140] | 0.761 | -276 [-1920; 1370] | 0.745 |

| GLP, pg/mL | -58.6 [-141; 24] | 0.175 | -16.9 [-88.1; 54.2] | 0.646 |

| IL6, pg/mL | 0.92 [-0.25; 2.08] | 0.134 | 1 [-0.17; 2.16] | 0.107 |

| IL8, pg/mL | -0.55 [-1.99; 0.9] | 0.466 | -0.62 [-1.57; 0.34] | 0.219 |

| Resistin, pg/mL | -1270 [-2530; -22.4] | 0.056 | -5.84 [-1190; 1180] | 0.992 |

| TNF a, pg/mL | -5.59 [-14.2; 3] | 0.212 | 3.81 [-3.15; 10.8] | 0.295 |

| PAI-1, pg/mL | 516 [-135; 1170] | 0.131 | 744 [282; 1210] | 0.004 |

| Visfatin, pg/mL | -258 [-1250; 731] | 0.613 | 19.9 [-626; 665] | 0.952 |

| sICAM, pg/mL | 9530 [-19500; 38600] | 0.525 | 22100 [2250; 42000] | 0.040 |

| LBP, ng/mL | 2520 [-411; 5450] | 0.103 | 1710 [-1210; 4630] | 0.263 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).