Submitted:

18 June 2024

Posted:

19 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Chronological Development of the Application of Acrylates and the Appearance of Adverse Reactions

3. Acrylates in Cosmetics and Medicine

4. Acrylates as a Cause of Allergic Contact Dermatitis and Other Disorders

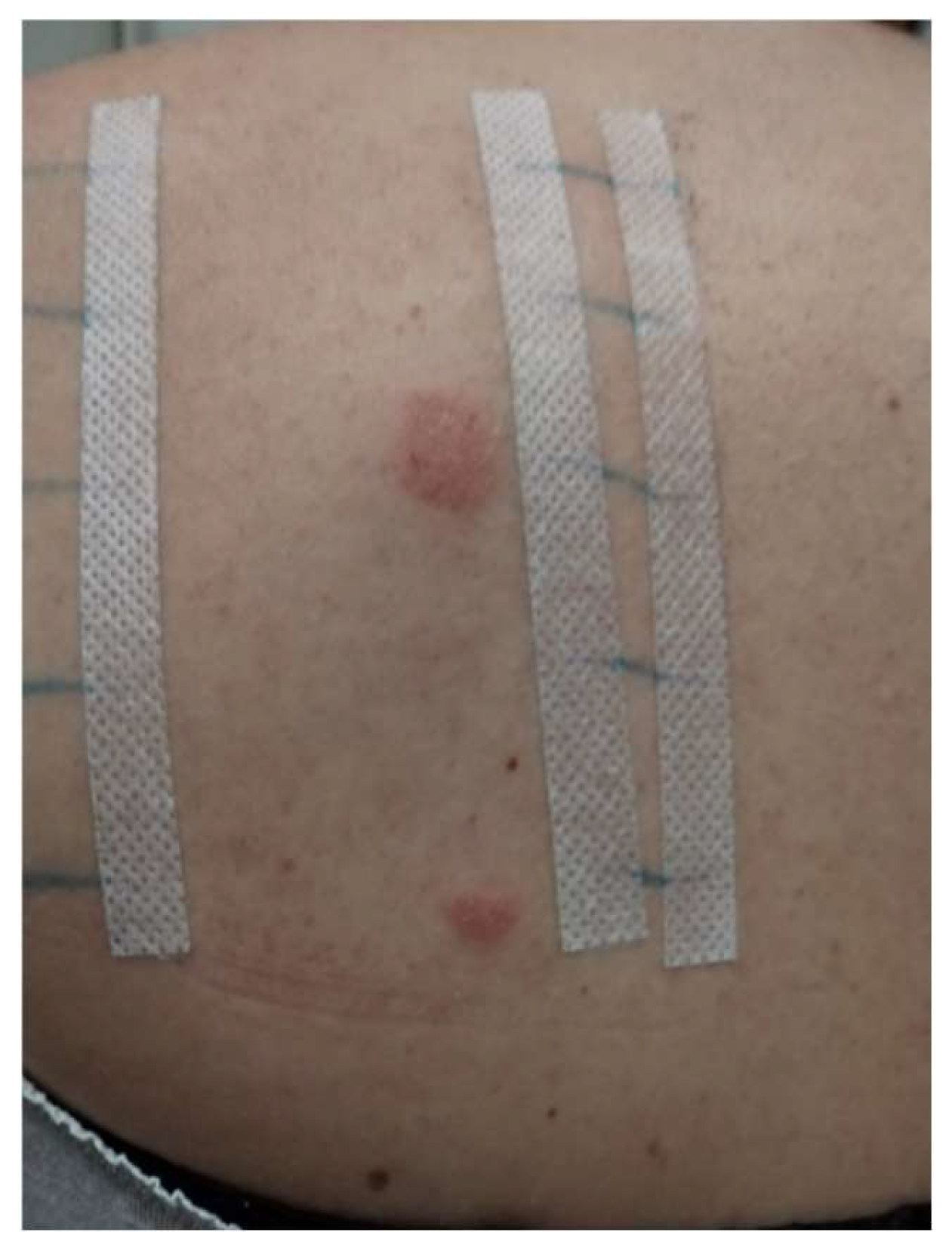

5. Diagnosis and Proof of Allergy to Acrylates

6. Allergy to Acrylates and Methacrylates in Dental Workers and Students

7. Preventive Procedures

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- de Groot, A.C.; Rustemeyer, T. 2-Hydroxyethyl methacrylate (HEMA): A clinical review of contact allergy and allergic contact dermatitis. Part 2. Cross- and co-sensitization, other skin reactions to HEMA, position of HEMA among (meth)acrylates, sensitivity as screening agent, presence of HEMA in commercial products and practical information on patch test procedures. Contact Dermatitis 2024, 90, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Havmose, M.; Thyssen, J.P.; Zachariae, C.; Johansen, J.D. Contact allergy to 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate in Denmark. Contact Dermatitis 2020, 82, 229–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Opalińska, S.; Opalińska, M.; Rudnicka, L.; Czuwara, J. Contact eczema induced by hybrid manicure. The role of acrylates as a causative factor. Postepy Dermatol. Alergol. 2022, 39, 768–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isaksson, M.; Zimerson, E.; Svedman, C. Occupational airborne allergic contact dermatitis from methacrylates in a dental nurse. Contact Dermatitis 2007, 57, 371–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos, L.; Cabral, R.; Gonçalo, M. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by acrylates and methacrylates—a 7-year study. Contact Dermatitis 2014, 71, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gregoriou, S.; Tagka, A.; Velissariou, E.; Tsimpidakis, A.; Hatzidimitriou, E.; Platsidaki, E.; Kedikoglou, S.; Chatziioannou, A.; Katsarou, A.; Nicolaidou, E.; et al. The rising incidence of allergic contact dermatitis to acrylates. Dermatitis 2020, 31, 140–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geukens, S.; Goossens, A. Occupational contact allergy to (meth)acrylates. Contact Dermatitis 2001, 44, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasseville, D. Acrylates in contact dermatitis. Dermatitis 2012, 23, 6–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cameli, N.; Silvestri, M.; Mariano, M.; Messina, C.; Nisticò, S.P.; Cristaudo, A. Allergic contact dermatitis, an important skin reaction in diabetes device users: a systematic review. Dermatitis 2022, 33, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyapina, M.; Dencheva, M.; Krasteva, A.; Tzekova, M.; Kisselova-Yaneva, A. Concomitant contact allergy to formaldehyde and methacrylic monomers in students of dental medicine and dental patients. Int. J. Occup. Med. Environ. Health 2014, 27, 797–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucharczyk, M.; Słowik-Rylska, M.; Cyran-Stemplewska, S.; Gieroń, M.; Nowak-Starz, G.; Kręcisz, B. Acrylates as a significant cause of allergic contact dermatitis: new sources of exposure. Postepy Dermatol. Alergol. 2021, 38, 555–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spencer, A.; Gazzani, P.; Thompson, D.A. Acrylate and methacrylate contact allergy and allergic contact disease: a 13-year review. Contact Dermatitis 2016, 75, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wrangsjö, K.; Swartling, C.; Meding, B. Occupational dermatitis in dental personnel: contact dermatitis with special reference to (meth)acrylates in 174 patients. Contact Dermatitis 2001, 45, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goon, A.T.; Isaksson, M.; Zimerson, E.; Goh, C.L.; Bruze, M. Contact allergy to (meth)acrylates in the dental series in southern Sweden: simultaneous positive patch test reaction patterns and possible screening allergens. Contact Dermatitis 2006, 55, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fugolin, A.P.; Dobson, A.; Mbiya, W.; Navarro, O.; Ferracane, J.L.; Pfeifer, C.S. Use of (meth)acrylamides as alternative monomers in dental adhesive systems. Dent. Mater. 2019, 35, 686–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rolls, S.; Rajan, S.; Shah, A.; Bourke, J.; Chowdhury, M.; Ghaffar, S.; Green, C.; Johnston, G.; Orton, D.; Reckling, C.; et al. (Meth)acrylate allergy: Frequently missed? Br. J. Dermatol. 2018, 178, 980–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Japundžić-Rapić, I.; Macan, J.; Babić, Ž.; Vodanović, M.; Salarić, I.; Prpić-Mehičić, G.; Gabrić, D.; Pondeljak, N.; Lugović-Mihić, L. Work-related and personal predictors of hand eczema in physicians and dentists: results from a field study. Dermatitis 2024, 35, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piirilä, P.; Kanerva, L.; Keskinen, H.; Estlander, T.; Hytönen, M.; Tuppurainen, M.; Nordman, H. Occupational respiratory hypersensitivity caused by preparations containing acrylates in dental personnel. Clin. Exp. Allergy 1998, 28, 1404–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muttardi, K.; White, I.R.; Banerjee, P. The burden of allergic contact dermatitis caused by acrylates. Contact Dermatitis 2016, 75, 180–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uter, W.; Geier, J. Contact allergy to acrylates and methacrylates in consumers and nail artists – data of the Information Network of Departments of Dermatology, 2004–2013. Contact Dermatitis 2015, 72, 224–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raposo, I.; Lobo, I.; Amaro, C.; Lobo, M.L.; Melo, H.; Parente, J.; Pereira, T.; Rocha, J.; Cunha, A.P.; Baptista, A.; et al. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by (meth)acrylates in nail cosmetic products in users and nail technicians – a 5-year study. Contact Dermatitis 2017, 77, 356–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dudek, W.; Wittczak, T.; Swierczyńska-Machura, D.; Kręcisz, B.; Nowakowska-Świrta, E.; Kieć-Świerczyńska, M.; Pałczyński, C. Allergic blepharoconjunctivitis caused by acrylates promotes allergic rhinitis response. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2014, 113, 492–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanerva, L.; Alanko, K.; Estlander, T.; Jolanki, R.; Lahtinen, A.; Savela, A. Statistics on occupational contact dermatitis from (meth)acrylates in dental personnel. Contact Dermatitis 2000, 42, 175–176. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Heratizadeh, A.; Werfel, T.; Schubert, S.; Geier, J.; IVDK. Contact sensitization in dental technicians with occupational contact dermatitis. Data of the Information Network of Departments of Dermatology (IVDK) 2001–2015. Contact Dermatitis 2018, 78, 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Splete, H.; Dermatologists name isobornyl acrylate contact allergen of the year. AT ACDS. 2019. Available online: https://www.mdedge.com/dermatology/article/195656/contact-dermatitis/dermatologists-name-isobornyl-acrylate-contact. (Accessed on 6 June 2024).

- Lin, Y.; Tsai, S.; Yang, C.; Tseng, Y.; Chu, C. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by acrylates in nail cosmetic products: case reports and review of the literature. Dermatol. Sin. 2018, 36, 218–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatica-Ortega, M.E.; Pastor-Nieto, M.A.; Mercader-García, P.; Silvestre-Salvador, J. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by (meth)acrylates in long-lasting nail polish – are we facing a new epidemic in the beauty industry? Contact Dermatitis 2017, 77, 360–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonçalo, M.; Pinho, A.; Agner, T.; Andersen, K.E.; Bruze, M.; Diepgen, T.; Foti, C.; Giménez-Arnau, A.; Goossens, A.; Johanssen, J.D.; et al. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by nail acrylates in Europe. An EECDRG study. Contact Dermatitis 2018, 78, 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canizares, O. Contact dermatitis due to the acrylic materials used in artificial nails. AMA Arch. Derm. 1956, 74, 141–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonçalo, M. Nail acrylate allergy: the beauty, the beast and beyond. Br. J. Dermatol. 2019, 181, 663–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gatica-Ortega, M.E.; Pastor-Nieto, M.A.; Gil-Redondo, R.; Martínez-Lorenzo, E.R.; Schöendorff-Ortega, C. Non-occupational allergic contact dermatitis caused by long-lasting nail polish kits for home use: ‘the tip of the iceberg’. Contact Dermatitis 2018, 78, 261–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ródenas-Herranz, T.; Navarro-Triviño, F.J.; Linares-González, L.; Ruiz-Villaverde, R.; Brufau-Redondo, C.; Mercader-García, P. Acrylate allergic contact dermatitis caused by hair prosthesis fixative. Contact Dermatitis 2020, 82, 62–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyry, H.S.I.; Liippo, J.P.; Virtanen, H.M. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by glucose sensors in type 1 diabetes patients. Contact Dermatitis 2019, 81, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herman, A.; de Montjoye, L.; Tromme, I.; Goossens, A.; Baeck, M. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by medical devices for diabetes patients: a review. Contact Dermatitis 2018, 79, 331–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raison-Peyron, N.; Mowitz, M.; Bonardel, N.; Aerts, O.; Bruze, M. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by isobornyl acrylate in OmniPod, an innovative tubeless insulin pump. Contact Dermatitis 2018, 79, 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mowitz, M.; Herman, A.; Baeck, M.; Isaksson, M.; Antelmi, A.; Hamnerius, N.; Pontén, A.; Bruze, M. N,N-dimethylacrylamide – a new sensitizer in the FreeStyle Libre glucose sensor. Contact Dermatitis 2019, 81, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oppel, E.; Kamann, S. Hydrocolloid blister plaster decreases allergic contact dermatitis caused by Freestyle Libre and isobornyl acrylate. Contact Dermatitis 2019, 81, 380–381. [Google Scholar]

- Dittmar, D.; Dahlin, J.; Persson, C.; Schuttelaar, M.L. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by acrylic acid used in transcutaneous electrical nervous stimulation. Contact Dermatitis 2017, 77, 409–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foti, C.; Lopalco, A.; Stingeni, L.; Hansel, K.; Lopedota, A.; Denora, N.; Romita, P. Contact allergy to electrocardiogram electrodes caused by acrylic acid without sensitivity to methacrylates and ethyl cyanoacrylate. Contact Dermatitis 2018, 79, 118–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, V.; Chaubal, T.V.; Bapat, R.A.; Shetty, D. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by polymethylmethacrylate following intradermal filler injection. Contact Dermatitis 2017, 77, 407–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marrero-Alemán, G.; Sabater-Abad, J.; Miquel, F.J.; Boix-Vilanova, J.; Mestre Bauzá, F.; Borrego, L. Allergic contact dermatitis to (meth)acrylates involving nail technicians and users: prognosis and differential diagnosis. Allergy 2019, 74, 1386–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parać, E.; Špiljak, B.; Lugović-Mihić, L.; Bukvić Mokos, Z. Acne-like eruptions: disease features and differential diagnosis. Cosmetics 2023, 10, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, G.I.; Robertson, A.S.; Moore, V.C.; Burge, P.S. Occupational asthma caused by acrylic compounds from SHIELD surveillance (1989–2014). Occup. Med. 2017, 67, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aalto-Korte, K.; Alanko, K.; Kuuliala, O.; Jolanki, R. Methacrylate and acrylate allergy in dental personnel. Contact Dermatitis 2007, 57, 324–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rustemeyer, T.; Frosch, P.J. Occupational contact dermatitis in dental personnel. In Kanerva’s Occupational Dermatology, John, S., Johansen, J., Rustemeyer, T., Elsner, P., Maibach, H., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Germany, 2019; pp. 1–12. ISBN 978-3-319-40221-5. [Google Scholar]

- Lugović-Mihić, L.; Ferček, I.; Duvančić, T.; Bulat, V.; Ježovita, J.; Novak-Bilić, G.; Šitum, M. Occupational contact dermatitis amongst dentists and dental technicians. Acta Clin. Croat. 2016, 55, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Japundžić, I.; Bembić, M.; Špiljak, B.; Parać, E.; Macan, J.; Lugović-Mihić, L. Work-related hand eczema in healthcare workers: etiopathogenic factors, clinical features, and skin care. Cosmetics 2023, 10, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamri, A.; Lill, D.; Summer, B.; Thomas, P.; Thomas, B.; Oppel, E. Artificial nail wearing: unexpected elicitor of allergic contact dermatitis, oral lichen planus and risky arthroplasty. Contact Dermatitis 2019, 81, 210–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazarov, A. Sensitization to acrylates is a common adverse reaction to artificial fingernails. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2007, 21, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, Y.; Okada, K.; Kondo, M.; Matsushita, T.; Nakazawa, S.; Yamazaki, Y. Oral health for achieving longevity. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2020, 20, 526–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savage, N.W.; Boras, V.V.; Barker, K. Burning mouth syndrome: clinical presentation, diagnosis and treatment. Aust. J. Dermatol. 2006, 47, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lugović-Mihić, L.; Špiljak, B.; Blagec, T.; Delaš Aždajić, M.; Franceschi, N.; Gašić, A.; Parać, E. Factors participating in the occurrence of inflammation of the lips (cheilitis) and perioral skin. Cosmetics 2023, 10, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symanzik, C.; Weinert, P.; Babić, Ž.; Hallmann, S.; Havmose, M.S.; Johansen, J.D.; Kezic, S.; Macan, M.; Macan, J.; Strahwald, J.; et al. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate and ethyl cyanoacrylate contained in cosmetic glues among hairdressers and beauticians who perform nail treatments and eyelash extension as well as hair extension applications: A systematic review. Contact Dermatitis 2022, 86, 480–492. [Google Scholar]

- Mattos Simoes Mendonca, M.; LaSenna, C.; Tosti, A. Severe onychodystrophy due to allergic contact dermatitis from acrylic nails. Skin Appendage Disord. 2015, 1, 91–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieć-Świerczyńska, M.; Świerczyńska-Machura, D.; Chomiczewska-Skóra, D.; Kręcisz, B.; Walusiak-Skorupa, J. Screening survey of ocular, nasal, respiratory and skin symptoms in manicurists in Poland. Int. J. Occup. Med. Environ. Health. 2017, 30, 887–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesonen, M.; Kuuliala, O.; Henriks-Eckerman, M.L.; Aalto-Korte, K. Occupational allergic contact dermatitis caused by eyelash extension glues. Contact Dermatitis 2012, 67, 307–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japundžić, I. The impact of working conditions and constitutional factors on the onest of contact dermatitis of the hands in dental medicine doctors and medical doctors. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Zagreb, School of Dental Medicine, Zagreb, Croatia, 2020. Available online: https://repozitorij.sfzg.unizg.hr/islandora/object/sfzg:708 (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- Drucker, A.M.; Pratt, M.D. Acrylate contact allergy: patient characteristics and evaluation of screening allergens. Dermatitis 2011, 22, 98–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minciullo, P.L.; Paolino, G.; Vacca, M.; Gangemi, S.; Nettis, E. Unmet diagnostic needs in contact oral mucosal allergies. Clin. Mol. Allergy 2016, 14, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aalto-Korte, K.; Henriks-Eckerman, M.L.; Kuuliala, O.; Jolanki, R. Occupational methacrylate and acrylate allergy—cross-reactions and possible screening allergens. Contact Dermatitis 2010, 63, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tillberg, A.; Stenberg, B.; Berglund, A. Reactions to resin-based dental materials in patients-type, time to onset, duration, and consequence of the reaction. Contact Dermatitis 2009, 61, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad Hunasehally, R.Y.; Hughes, T.M.; Stone, N.M. Atypical pattern of (meth)acrylate allergic contact dermatitis in dental professionals. Br. Dent. J. 2012, 213, 223–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieć-Świerczyńska, M.K. Occupational allergic contact dermatitis due to acrylates in Lodz. Contact Dermatitis 1996, 34, 419–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanerva, L.; Estlander, T.; Jolanki, R.; Tarvainen, K. Occupational allergic contact dermatitis caused by exposure to acrylates during work with dental prostheses. Contact Dermatitis 1993, 28, 268–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budimir, J.; Mravak-Stipetić, M.; Bulat, V.; Ferček, I.; Japundžić, I.; Lugović-Mihić, L. Allergic reactions in oral and perioral diseases-what do allergy skin test results show? Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2019, 127, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.; Padmanabhan, T.V. Methyl methacrylate permeability of dental and industrial gloves. N. Y. State Dent. J. 2009, 75, 40–42. [Google Scholar]

- Morgado, F.; Batista, M.; Gonçalo, M. Short exposures and glove protection against (meth)acrylates in nail beauticians – thoughts on a rising concern. Contact Dermatitis 2019, 81, 62–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aalto-Korte, K.; Pesonen, M. The additive value of patch testing non-commercial test substances and patients' own products in a clinic of occupational dermatology. Contact Dermatitis 2023, 88, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieć-Świerczyńska, M.; Krecisz, B.; Chomiczewska-Skóra, D. Occupational contact dermatitis to acrylates in a manicurist. Occup. Med. (Lond.) 2013, 63, 380–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Liu, F.; He, J. Preparation of low shrinkage stress dental composite with synthesized dimethacrylate oligomers. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2019, 94, 222–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, S.B.; Petzhold, C.L.; Gamba, D.; Leitune, V.C.B.; Collares, F.M. Acrylamides and methacrylamides as alternative monomers for dental adhesives. Dent. Mater. 2018, 34, 1634–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author, Year [Reference number] | Examinees/Patients | Analysed Factors - Methods | Results | Conclusions |

| Kanerva L et al., 1993 [64] | 4 patients (an orthodontist, 2 dental technicians, and an in-house trained dental worker) | Patch testing for allergens in dental prostheses | All patients had positive allergic patch test reactions to MMA. | Dental personnel working with prostheses - higher risk of sensitization. Patients working with dental prostheses should be patch-tested with MMA, 2-HEMA, dimethacrylates, epoxy acrylates, and urethane acrylates to detect occupational ACD. |

| Kiec-Swierczynska MK, 1996 [63] |

1619 patients suspected of occupational CD (examined during 1990-1994) | Patch testing to acrylates and methacrylates including EGDMA, MMA, 2-HEMA and TEGDMA | The most frequent sensitizers were: EGDMA (5 positive patch tests), MMA (4), 2-HEMA (4) and TEGDMA (4). Sensitivity to acrylates was diagnosed in 9 patients (4 dental technicians, 4 dentists, 1 textile printer). |

Dentists more sensitive to (meth)acrylate allergens and other allergens (metals and rubber additives). Dental techniques mainly sensitive to methacrylates. The textile printer was only sensitive to acrylates. |

| Geukens S and Goossens A, 2001 [7] |

3,833 patients suspect of CD (during 1978-1999) | Patients were tested by patch test | The top three sensitizers were EGDMA (17 positive patch tests), 2-HEMA, (14), and TEGDMA (6). Almost the half of the examinees (14/31) were affected by (meth)acrylate-containing dental materials (including dentists and dental technology students). |

An increasing trend in dermatological issues associated with the expanding use of (meth)acrylates, particularly in dental professions. |

| Wrangsjö K et al., 2001 [13] | 174 dental personnel referred as patients to the Department of Occupational and Environmental Dermatology, Stockholm (1995- 1998) | Patch testing to the Swedish standard series and a dental screening series. Testing for IgE-mediated allergy to natural rubber latex (NRL). |

Hand eczema affected 63% participants; 67% ICD, and 33% ACD. 59% of participants had positive reactions to standard series substances and 40% to the dental series. 22% had positive reactions to (meth)acrylates, primarily to multiple test preparations, including HEMA, EGDMA, and MMA. Allergy to NRL was recorded in 10% of patients. |

Irritant hand dermatitis was the predominant diagnosis among dental personnel. Contact allergy to (meth)acrylate in around 20% of the tested patients, mostly to 3 test substances; HEMA, EGDMA and MMA. (Meth)acrylate allergy often coexisted with atopy and/or other contact allergies. |

| Goon AT et al., 2006 [14] |

1639 subjects were patch-tested at the Department of Occupational and Environmental Dermatology, Malmo, Sweden | Patch tests to to either dental patient series or dental personnel series including (meth)acrylate allergens: identification of common allergens and their prevalence in each group. | Positive patch tests to (meth)acrylate allergens were seen in 2.3% (30/1322) of the dental patients and 5.8% (18/310) of the dental personnel. The most common allergens for both groups were 2-HEMA, EGDMA, and MMA. |

2-HEMA is important screening allergen to detect contact allergy to (meth)acrylates used in the dental profession. |

| Isaksson M et al., 2007 [4] | A case report (dental nurse with facial eczema allegedly caused by airborne methacrylates in the workplace) | Patch testing with serial dilutions of several methacrylates and work provocations in methacrylate environments | High reactivity to patch testing. Repeated exposure to methacrylates at work led to facial eczema; resolved when away. Efforts to collect the sensitizers using air pumps and filters failed. |

Facial dermatitis may be associated with airborne methacrylate exposure, which may involve allergy to ≥1 allergens. |

| Ramos L et al., 2014 [5] |

An observational and retrospective study (January 2006–April 2013) | Evaluation and correlation of epidemiological and clinical parameters and positive patch test results with (meth)acrylates. | 37/122 patients show a positive patch test with an extended (meth)acrylate series. 25 cases (67.6%) were occupational. Hand eczema with pulpitis in 32 patients: 28 related to artificial nails, 3 to dental materials, and 2 to industrial work. Oral lesions associated with dental prostheses in 4 patients. 31/37 positive to >1 (meth)acrylate. Beauty technicians with artificial nails accounted for 80% of occupational cases. |

HEMA detected 80.6% of cases and it may serve as a reliable screening allergen. A broader range of allergens is advisable for accurate diagnosis. |

| Muttardi K et al., 2016 [19] |

A retrospective study of 241 patients were patch tested with meth(acrylates) and cyanoacrylates (January 2012 – February 2015) | Patch testing with the mini-acrylate or extended acrylate series. | 16/241 patients had positive patch test reactions to (meth)acrylate or cyanoacrylate. Female predominance (M/F ratio of 1:15). |

(Meth)acrylate allergy is mainly occupational, but more common in younger women, especially beauticians and nail technicians. |

| Havmose M et al., 2020 [2] | 1293 female patients patch-tested with HEMA | Two groups of patients based on their positive/negative patch test reactions to HEMA. MOAHLFA characteristics analyzed for both groups. |

31 (2.4%) of the tested examinees were positive to HEMA. | Sensitization and elicitation of ACD to HEMA primarily from artificial nail modeling systems; a significant health issue for consumers and certain professions. |

| Gregoriou S et al., 2020 [6] | 156 female patients with ACD - using/performing cosmetic nail procedures (January 2009 – December 2018) | The incidence of positive sensitization to (meth)acrylates assessed using patch tests. | Contact allergy to ≥1 (meth)acrylates in 74.4%: 88.5% occupationally exposed, and 11.5% consumers. A statistically significant increase in (meth)acrylate ACD during 2014-2018 (79%) compared to 2009–2013 (55%). EGDMA was the most common sensitizer positive in 72.4%. Among acrylate-positive patients, the rate was 97.4%. |

A global trend of increasing (meth)acrylate sensitization among nail technicians and users of nail products with ACD. Enhancing preventive measures is essential. |

| Opaliñska S et al., 2022 [3] | 8 women with CD related to acrylates found in hybrid varnishes | Manicure using a home acrylic nail kit and a non-professional UV lamp. Clinical and dermoscopic features were assessed. |

Allergen contact areas (skin and nails) were affected. Severity correlated with exposure duration. Common findings: subungual hyperkeratosis and onycholysis (8/8 patients), eczematous finger pulp fissuring (2/8 patients) (more specific). |

Nail changes from hybrid manicures may resemble onychomycosis or nail psoriasis (patch tests in uncertain cases) - ACD was suspected. Confirmed acrylate allergies require patient awareness and avoidance. |

| de Groot AC, Rustemeyer T, 2024 [1] |

24 studies presenting case series and 168 case reports on patients with ACD attributed to HEMA | Review of cross- and co-sensitization, atypical contact allergy manifestations, HEMA versus other (meth)acrylates, HEMA's screening sensitivity, and its presence in commercial products. | Strong cross-allergy exists between HEMA, EGDMA, and HPMA. Reactions to EGDMA often from primary HEMA sensitization. Rare atypical manifestations of HEMA allergy include lichen planus, lymphomatoid papulosis, systemic CD, leukoderma post-positive patch tests, and systemic side effects (nausea, diarrhea, malaise, palpitations). |

HEMA is the most common patch test-positive methacrylate; an effective screening agent for other (meth)acrylates allergies. Sensitization to HEMA 2% pet. in patch tests is exceedingly rare. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).