Submitted:

18 June 2024

Posted:

19 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Theoretical Delimitation

1.1.1. Theoretical Models of Tourism and Their Relevance

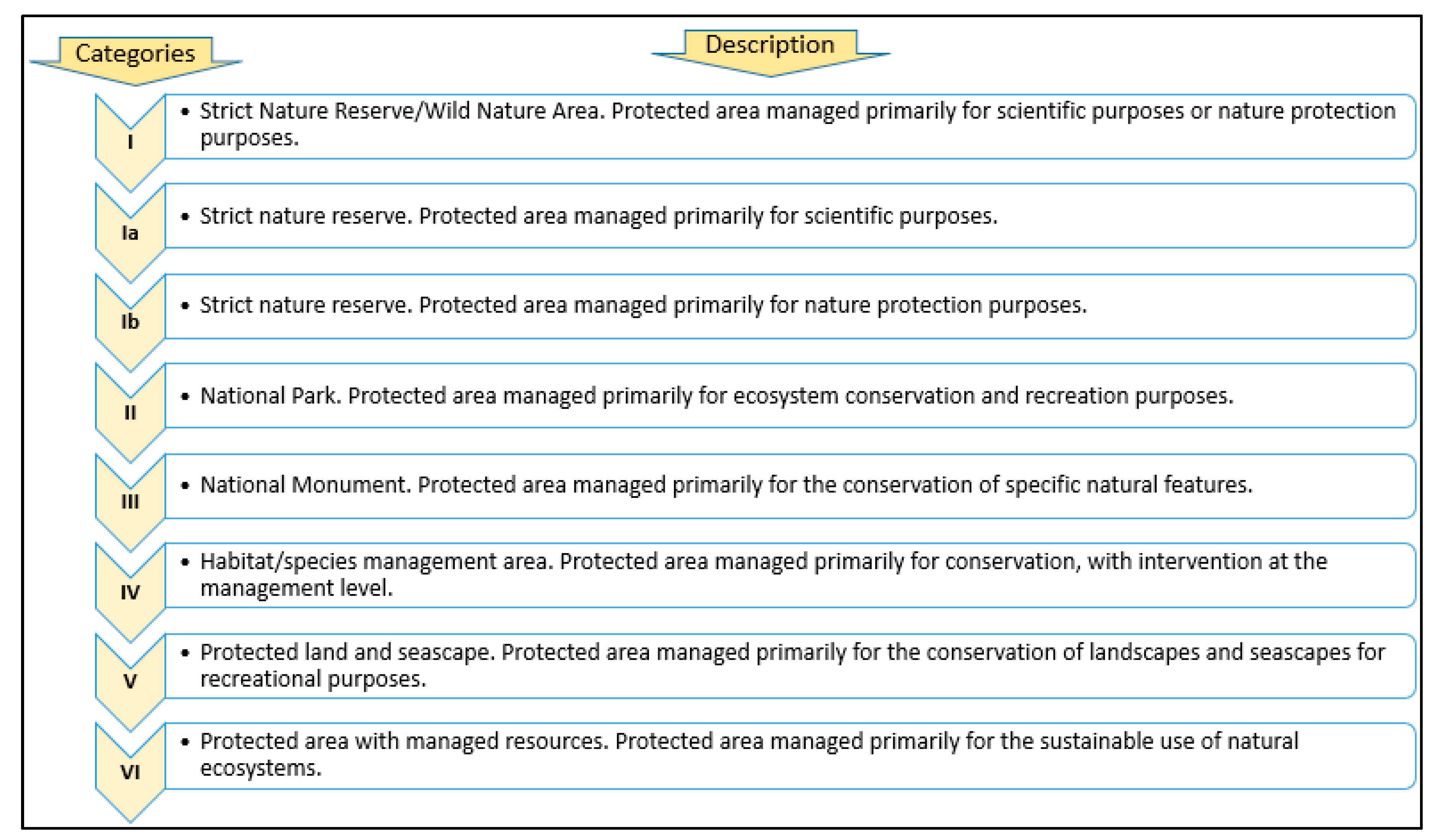

1.1.2. The Sustainable Tourism Model for Protected Areas

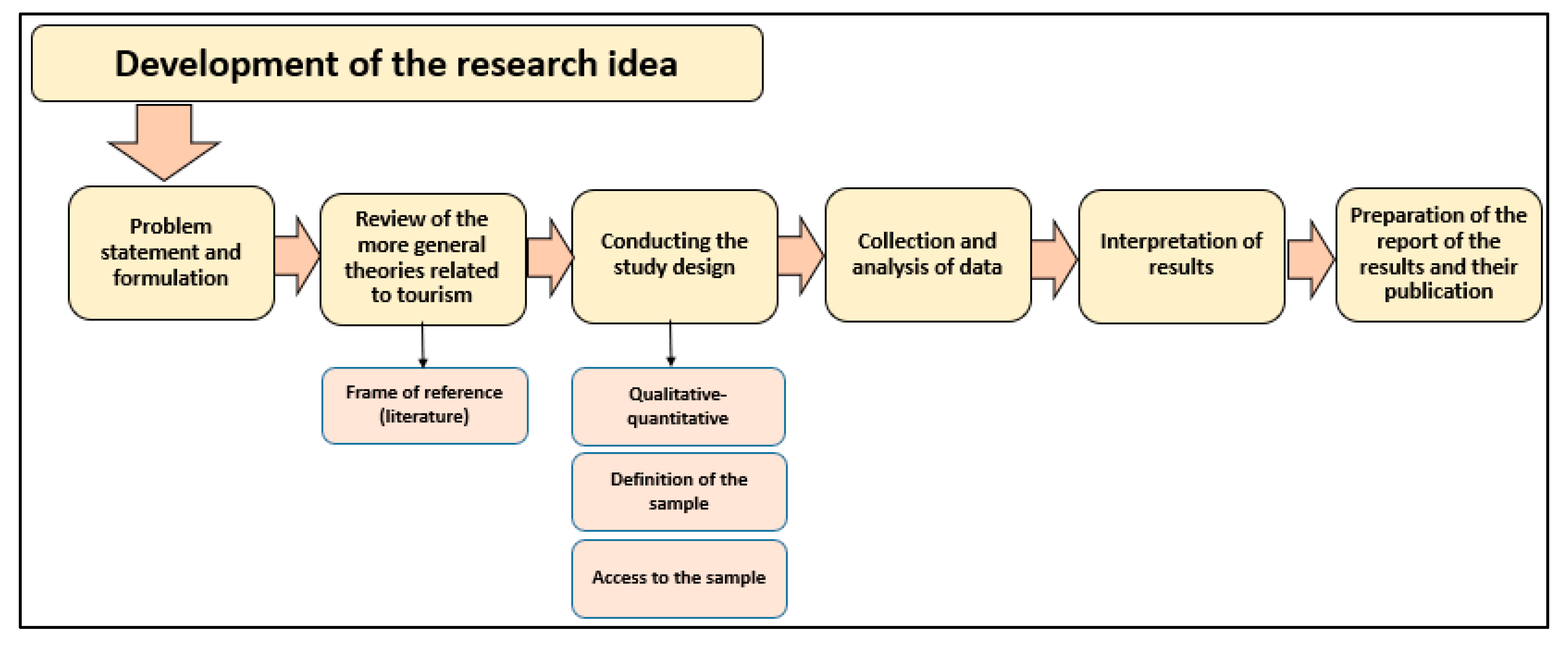

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

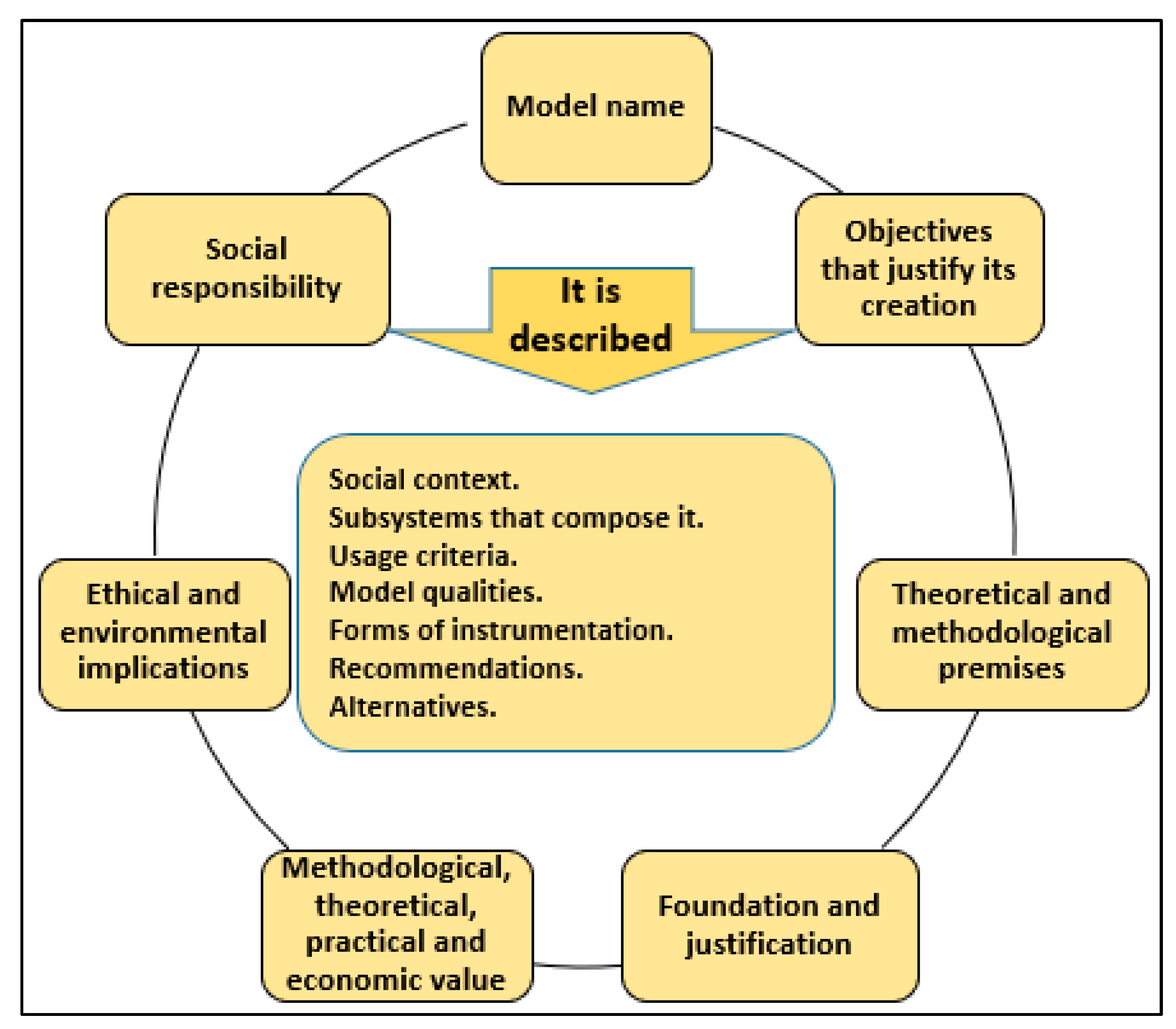

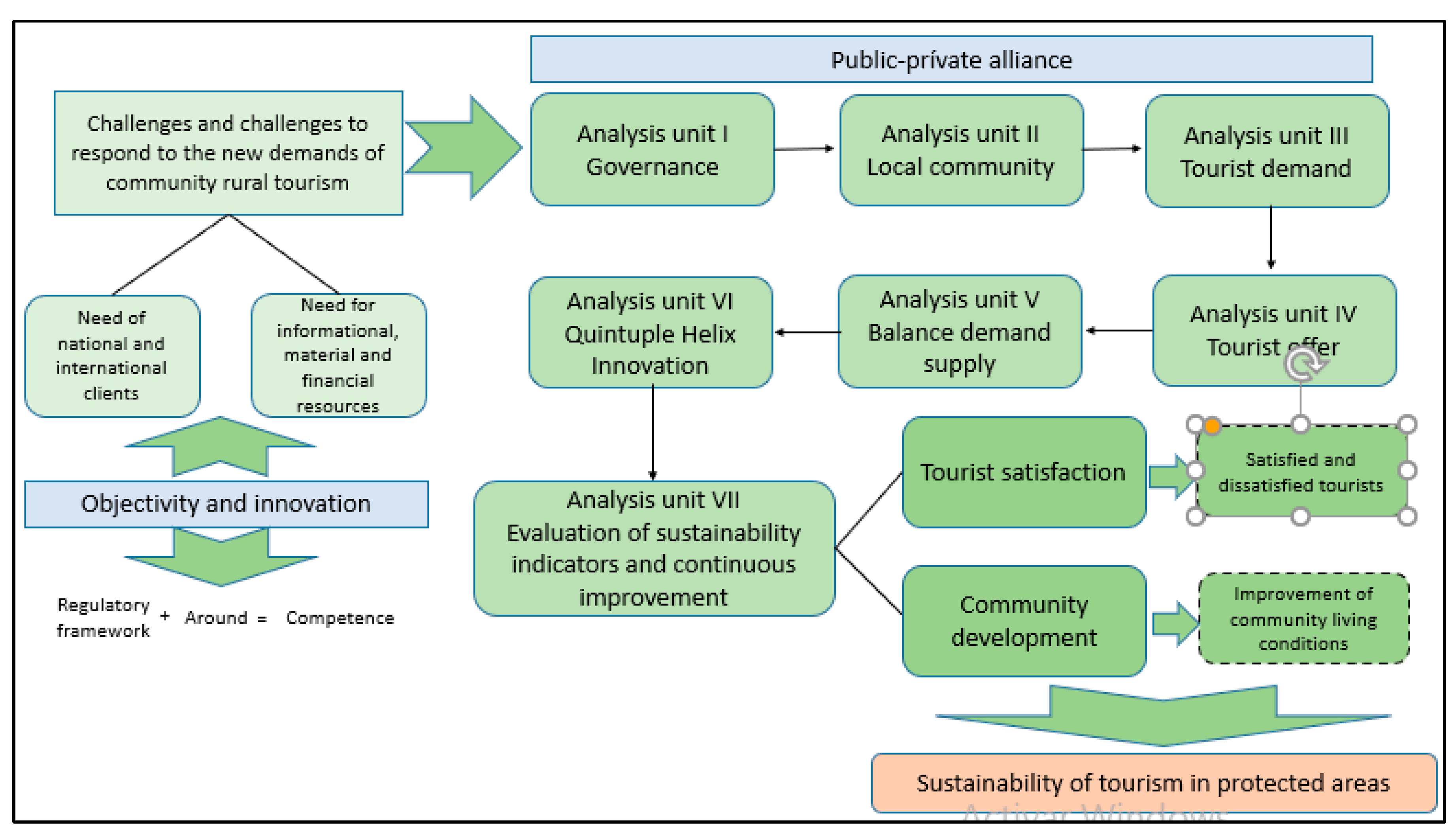

3.1. The Sustainable Tourism Model in Protected Areas

3.2. Synthesis of the Proposed Model

3.3. Foundation and Justification of the Sustainable Tourism Model in Protected Areas

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baggio, R.; Scott, N.; Cooper, C. Improving tourism destination governance: A complexity science approach. Tour. Rev. 2010, 65, 51–60. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1108/16605371011093863. (Accessed on 20 November 2023). [CrossRef]

- Brouder, P.; Teoh, S.; Salazar, N.B.; Mostafanezhad, M.; Pung, J.M.; Lapointe, D.; Higgins-Desbiolles, F.; Haywood, M.; Hall, C.M.; Clausen, H.B. Reflections and discussions: Tourism matters in the new normal post COVID-19. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 735–746. http://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1770325. [CrossRef]

- Naranjo Llupart, M.R. Theoretical Model for the Analysis of Community-Based Tourism: Contribution to Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10635. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141710635. [CrossRef]

- Montes, Carlos.; Osvaldo Sala. La Evaluación de los Ecosistemas del Milenio. Las relaciones entre el funcionamiento de los ecosistemas y el bienestar humano. Ecosistemas 2007, 16, 3. http://revistaecosistemas.net/index.php/ecosistemas/article/view/120. (Accessed on 15 December 2023).

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68. http://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68. [CrossRef]

- Cummins, R.A.; Nistico, H. Maintaining life satisfaction: The role of positive cognitive bias. J. Happiness Stud. 2002, 3, 37–69. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1023/A:1015678915305. (Accessed on 9 March 2024).

- Diener, E. A. Value based index for measuring national quality of life. Soc. Indic. Res. 1995, 36, 107–127. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF01079721. (Accessed on 10 November 2023).

- Tuula, H.; Tuuli, H. Wellbeing and sustainability: A relational approach. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 23, 167–175. http://doi.org/10.1002/sd.1581. [CrossRef]

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F. Sustainable tourism: Sustaining tourism or something more? Tourism Management Perspectives, 25(1), 2018. 157-160. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2017.11.017. [CrossRef]

- Deb, S., Das, M., Voumix, L., Nafi, S., Rashid, M., Esquivias, M. The environmental effects of tourism: analyzing the impact of tourism, global trade, consumption expenditure, electricity, and population on environment in leading global tourist destinations. GeoJournal of Tourism and Geosites, 51(4), 2023. 1703-1716. https://doi.org/10.30892/gtg.514spl11-1166. [CrossRef]

- Meadows, Donella H., et al. Los límites del crecimiento: informe al Club de Roma sobre el predicamento de la humanidad. Vol. 116. México: Fondo de cultura económica, 1972. https://blocs.xtec.cat/dcolellcs/files/2019/09/Sobre-Meadows.pdf. (Accessed on 9 March 2024).

- Taibo, Carlos. Decrecimiento, crisis, capitalismo. Colección de estudios internacionales 5, 2009. https://ojs.ehu.eus/index.php/ceinik/article/view/13666. (Accessed on 10 March 2024).

- Latouche, Serge. El decrecimiento como solución a la crisis. Ed. CIECAS – IPN, México. 2010 Pg 47-53. https://repositorio.flacsoandes.edu.ec/bitstream/10469/7158/1/REXTN-MS21-05-Latouche.pdf. (Accessed on 10 March 2024).

- ONU. Conferencia de las Naciones Unidas sobre Medio Ambiente y Desarrollo, Río de Janeiro, Brasil, 3 a 14 de junio de 1992: https://www.un.org/es/conferences/environment/rio1992. (Accessed on 14 March 2024).

- Gauna Ruiz de León, Carlos. Percepción de la problemática asociada al turismo y el interés por participar de la población: caso Puerto Vallarta. El periplo sustentable 33, 2017: 251-290. https://rperiplo.uaemex.mx/article/view/4858. (Accessed on 10 December 2023).

- Castiñeira, Carlos Javier Baños. La oferta turística complementaria en los destinos turísticos alicantinos: implicaciones territoriales y opciones de diversificación. Investigaciones Geográficas (Esp) 19, 1998: 85-103. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/176/17654249005.pdf. (Accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Paul F. J. Eagles, Stephen F. McCool y Christopher D. Haynes. Sustainable tourism in protected areas Planning and management guidelines. United Nations Environment Programmed, World Tourism Organization and IUCN – World Conservation Union. 2002. https://www.institutobrasilrural.org.br/download/20120219144738.pdf. (Accessed on 10 January 2024).

- Asamblea Nacional Legislativa. Código Orgánico del Ambiente. Registro Oficial Suplemento 983 de 12-abr.-2017 Estado: Vigente. https://www.emaseo.gob.ec/documentos/lotaip_2018/a/base_legal/Codigo_organico%20de%20ambiente_2017.pdf. (Accessed on 26 February 2024).

- Vera-Rebollo, José Fernando.; Carlos Javier Baños Castiñeira. Turismo, territorio y medio ambiente. La necesaria sostenibilidad. Universidad de Alicante. 2004. https://rua.ua.es/dspace/bitstream/10045/132322/1/Vera_Banos_2004_PapEconEsp.pdf. (Accessed on 25 May 2024).

- Aguirre, G. El turismo sostenible comunitario en Puerto el Morro: Análisis de su aplicación e incidencia económica. Univ. Soc. 2019, 11, 289–294. Available online: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2218-36202019000100289. (Accessed on 16 June 2023).

- Tite, G.M.; Carrillo, D.M.; Ochoa, M.B. Turismo accesible: Estudio bibliométrico. Tur. Soc. 2021, 28, 115–132. http://doi.org/10.18601/01207555.n28.06. [CrossRef]

- Korstanje, M.E. El COVID-19 y el turismo rural: Una perspectiva antropológica. Dimens. Turísticas 2020, 4, 179–196. http://doi.org/10.47557/CKDK5549. [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, H. ¿El coronavirus reescribirá el turismo rural? Reinvención, adaptación y acción desde el contexto latinoamericano: Reinvenção, adaptação e ação no contexto latino-americano. Cenário Rev. Interdiscip. Tur. Territ. 2020, 8, 55–72. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=7869335. (Accessed on 11 December 2023).

- Iorio, M.; Corsale, A. Community-based tourism and networking: Viscri, Romania. J. Sustain. Tour. 2014, 22, 234–255. Available online: https://pascal-francis.inist.fr/vibad/index.php?action=getRecordDetail&idt=28222623. (Accessed on 5 July 2023).

- Maldonado, C. Fortaleciendo Redes de Turismo Comunitario. REDTURS Bolivia No 4. 2007. Available online: https://www.nacionmulticultural.unam.mx/empresasindigenas/docs/2053.pdf. (Accessed on 6 November 2023).

- Barriga, Andrea Muñoz. Percepciones de la gestión del turismo en dos reservas de biosfera ecuatorianas: Galápagos y Sumaco. Investigaciones Geográficas, Boletín del Instituto de Geografía 2017.93, 2017: 110-125. https://doi.org/10.14350/rig.47805. [CrossRef]

- Frías, Margarita Capdepón. Las áreas protegidas privadas como escenarios para el turismo. Implicaciones y cuestiones clave. Cuadernos geográficos de la Universidad de Granada 60.2, 2021: 72-90. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=8001811. (Accessed on 6 March 2024).

- Murcia García, Cecilia, John Freddy Ramírez-Casallas, and Oscar Camilo Valderrama Riveros. "La participación ciudadana, factor asociado al desarrollo del turismo sostenible: caso ciudad de Ibagué (Colombia)." Anales de Geografía de la Universidad Complutense. Vol. 40. No. 1. 2020. http://dx.doi.org/10.5209/AGUC.69336. [CrossRef]

- Shibia, Mohamed G. Determinants of attitudes and perceptions on resource use and management of Marsabit National Reserve, Kenya. Journal of Human Ecology 30.1 2010: 55-62. https://doi.org/10.1080/09709274.2010.11906272. [CrossRef]

- Chiedza, Ngonidzashe Mutanga.; Sebastián, Vengesayi.; Nunca Muboko.; Edson, Gandiwa. Towards harmonious conservation relationships: A framework for understanding protected area staff-local community relationships in developing countries. Journal for Nature Conservation 25. 2015: 8-16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnc.2015.02.006. [CrossRef]

- Mir, Zaffar Rais.; Athar, Noor.; Bilal, Habib.; Gopi, Govindan Veeraswami. Actitudes de la población local hacia la conservación de la vida silvestre: un estudio de caso del valle de Cachemira. Investigación y desarrollo de montañas 35.4, 2015: 392-400. https://doi.org/10.1659/MRD-JOURNAL-D-15-00030.1. [CrossRef]

- Perry, Elizabeth E., Mark D. Needham y Lori A. Cramer. Confianza, similitud, actitudes e intenciones de los residentes costeros con respecto a las nuevas reservas marinas en Oregón. Sociedad y recursos naturales 30.3, 2017: 315-330. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2016.1239150. [CrossRef]

- Mengesha, Girma.; Yosef, Mamo.; Kefyalew Sahle.; Chris Elphick.; and Afework Bekele. Effects of land-use on birds’ diversity in and around Lake Zeway, Ethiopia. Journal of Science & Development 2, 2014: 2. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Mamo-Yosef/publication/293332579_Effects_of_land-use_on_birds'_diversity_in_and_around_Lake_Zeway_Ethiopia/links/56b75fb008aebbde1a7df0fa/Effects-of-land-use-on-birds-diversity-in-and-around-Lake-Zeway-Ethiopia.pdf. (Accessed on 10 March 2024).

- Dafau Arjona, Ivonne Lizeth. Actitudes ambientales de la sociedad hacia el aprovechamiento turístico sustentable de la Laguna de Términos. MS thesis. Universidad de Quintana Roo, 2019. http://risisbi.uqroo.mx/handle/20.500.12249/3135. (Accessed on 12 March 2024).

- Ngonidzashe Mutanga, Chiedza; Sebastián, Vengesayi; Nunca, Muboko. Community perceptions of wildlife conservation and tourism: A case study of communities adjacent to four protected areas in Zimbabwe. Tropical Conservation Science 8.2, 2015: 564-582. https://doi.org/10.1177/194008291500800218. [CrossRef]

- Tilahun, Belete.; Kassahun, Abie.; Asalfew, Feyisa.; Alemneh, Amare. Actitud y percepciones de las comunidades locales hacia el valor de conservación del parque nacional gibe Sheleko, suroeste de Etiopía. Economía agrícola y de recursos: Revista electrónica científica internacional 3.2, 2017: 65-77. DOI: https://doi.org/10.51599/are.2017.03.02.06. [CrossRef]

- Caviedes-Rubio, Diego Iván.; Alfredo Olaya-Amaya. Ecoturismo en áreas protegidas de Colombia: una revisión de impactos ambientales con énfasis en las normas de sostenibilidad ambiental." Revista Luna Azul 46, 2018: 311-330. https://doi.org/10.17151/luaz.2018.46.16. [CrossRef]

- Macura, Biljana.; Francisco Zorondo Rodríguez.; Mar Grau Satorras.; Kathryn Demps.; María Laval.; Claude A.; García, Victoria Reyes García. Actitudes de la comunidad local hacia los bosques fuera de las áreas protegidas en la India. Impacto de la conciencia jurídica, la confianza y la participación". Ecología y sociedad 16.3, 2011. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26268928. (Accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Fox, H. K.; Molina, A. C.; Swearingen, T. C. An Interrupted Time Series Approach to Assessing the Impacts of Marine Protected Areas on Recreational Fishing License Sales, 32 (12), 2022. 1970-1982. https://doi.org/10.1002/aqc.3889. [CrossRef]

- Ferrero, Brián G. Tras una definición de las áreas protegidas: Apuntes sobre la conservación de la naturaleza en Argentina. Revista Universitaria de Geografía 27.1, 2018: 99-117. http://www.scielo.org.ar/scielo.php?pid=S1852-42652018000100006&script=sci_arttext. (Accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Holdgate, Martin. The green web: a union for world conservation. Routledge, 2014. https://www.routledge.com/The-Green-Web-A-Union-for-World-Conservation/Holdgate/p/book/9781853835957. (Accessed on 15 November 2023).

- Kelleher, Graeme. Directrices para áreas marinas protegidas. Ed, Comisión Mundial de Áreas Protegidas (CMAP). 1999. https://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.CH.1999.PAG.3.en. [CrossRef]

- Dudley, Nigel. Directrices para la aplicación de las categorías de gestión de áreas protegidas. Ed. Iucn, 2008. https://books.google.es/books?hl=es&lr=&id=xLZKJE_bpzgC&oi=fnd&pg=PA1&dq=proceso+evolutivo+del+concepto+y+significado+de+las+%C3%A1reas+protegidas+&ots=C27pSSy3f7&sig=fT7Nc-mm6loDsXjh1lINzkScn1s#v=onepage&q&f=false. (Accessed on 8 March 2024).

- Cifuentes, Miguel.; Arturo, Izurieta.; Helder, Henrique de Faria. Medición de la efectividad del manejo de áreas protegidas. Vol. 2. 2000. WWF: IUCN: GTZ, 2000. 105 p., 22 cm. https://awsassets.panda.org/downloads/wwfca_measuring_es.pdf. (Accessed on 4 March 2024).

- ONU. Convenio sobre la diversidad Biológica. Organización de las Naciones Unidas 1992. https://www.cbd.int/doc/legal/cbd-es.pdf. (Accessed on 14 December 2023).

- Márquez Guerra, José Francisco. Reglamentos indígenas en áreas protegidas de Bolivia: el caso del Pilón Lajas. Revista de derecho 46, 2016: 71-110. https://doi.org/10.14482/dere.46.811. [CrossRef]

- Sandwith, Trevor.; Lawrence, Hamilton.; David, Sheppard. Protected areas for peace and co-operation. Best practice protected area guidelines. Ed. Adrian Phillips, series 7 2001. http://web.bf.uni-lj.si/students/vnd/knjiznica/Skoberne_literatura/gradiva/zavarovana_obmocja/IUCN_TBPA.pdf. (Accessed on 13 January 2024).

- Íñiguez Dávalos, Luis Ignacio.; Jiménez Sierra, Cecilia Leonor.; Sosa Ramírez, Joaquín.; Ortega-Rubio, Alfredo. Categorías de las áreas naturales protegidas en México y una propuesta para la evaluación de su efectividad. Investigación y ciencia 22.60, 2014: 65-70. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/674/67431160008.pdf. (Accessed on 3 March 2024).

- Green, Michael J. B.; James Paine. State of the World's Protected Areas at the End of the Twentieth Century. Ed. UICN. 1997. https://aquadocs.org/handle/1834/867. (Accessed on 20 December 2023).

- Hockings, Marc.; Sue, Stolton.; Nigel Dudley. Evaluating effectiveness: a framework for assessing the management of protected areas. Ed. UICN, No. 6. 2000. https://espace.library.uq.edu.au/view/UQ:162233. (Accessed on 2 March 2024).

- Hiernaux-Nicolas, D.; Cordero, A.; Duynen-Montijn, L. Imaginarios Sociales y Turismo Sostenible. Cuaderno de Ciencias Sociales 123; Sede Académica, Costa Rica. Facultad Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales FLACSO: San José, Costa Rica, 2002. Available online: http://biblioteca.clacso.edu.ar/Costa_Rica/flacso-cr/20120815033220/cuaderno123.pdf. (Accessed on 29 March 2024).

- Light, D.; Cretan, R.; Dunca, A.-M. Museums and transitional justice: Assessing the impact of a memorial museum on young people in post-communist Romania. Societies 2021, 11, 43. http://doi.org/10.3390/soc11020043. [CrossRef]

- Popescu, L.; Albă, C. Museums as a means to (re)make regional identities: The Oltenia museum (Romania) as case study. Societies 2022, 12, 110. http://doi.org/10.3390/soc12040110. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz Ballesteros, E.; Solís Carrión, D. Turismo Comunitario en Ecuador Desarrollo y Sostenibilidad Social, 1st ed.; Abya-Yala: Quito, Ecuador, 2007; p. 333. Available online: https://animacionsociocultural2013.files.wordpress.com/2013/05/turismo-comunitarioen-ecuador.pdf. (Accessed on 10 February 2024).

- Prieto, M. Espacios en Disputa: El turismo en Ecuador, 1st ed.; Flacso Ecuador: Quito, Ecuador, 2011; p. 232. Available online: http://190.57.147.202:90/xmlui/handle/123456789/1881. (Accessed on 6 February 2024).

- Hiwasaki, L. Community-based tourism: A pathway to sustainability for Japan’s protected areas. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2006, 19, 675–692. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/08941920600801090. (Accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Lepp, A. Residents attitudes towards tourism in Bigodi village, Uganda. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 876–885. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0261517706000483. (Accessed on 12 February 2024).

- Alaeddinoglu, F.; Can, A. S. Identification and classification of nature-based tourism resources: Western Lake Van basin, Turkey. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 19, 198–207. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.05.124. [CrossRef]

- Timothy, D.J.; Blanco, K. Community-based ecotourism development ion the periphery of Belize. Curr. Issues Tour. 1999, 2, 226–243. http://doi.org/10.1080/13683509908667853. [CrossRef]

- Patterson, T.; Gulden, T.; Cousins, K.; KRAEV, E. Integrating environmental, social and economic systems: A dynamic model of tourism in Dominica. Ecol. Model. 2004, 175, 121–136. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2003.09.033. [CrossRef]

- Zorn, E.; Farthing, L.C. Communitarian tourism. Hosts and mediators in Peru. Ann. Tour. Res. 2007, 34, 673–689. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2007.02.00262. [CrossRef]

- Guerreiro, E.M. O turismo como agente de desenvolvimento social e a comunida de Guaraninas Ruínas Jesuíticas de Sao Miguel das Missoes. PASOS: Rev. Tur. Patrim. Cult. 2007, 5, 343–352. http://doi.org/10.25145/j.pasos.2007.05.025. [CrossRef]

- Loor-Bravo, L.; Plaza-Macías, N.; Medina-Valdés, Z. Turismo comunitario en Ecuador: Apuntes en tiempos de pandemia. Rev. De Cienc. Soc. 2021, 27, 265–277. http://doi.org/10.31876/rcs.v27i1.35312. [CrossRef]

- Maldonado-Erazo, C.P.; Río-Rama, M.C.; Noboa-Viñan, P.; Álvarez-García, J. Community-based tourism in Ecuador: Community ventures of the provincial and cantonal networks. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6256. http://doi.org/10.3390/su12156256. [CrossRef]

- Alcívar, I.; Mendoza-Mejía, J.L. Modelo de gestión del turismo comunitario orientado hacia el desarrollo sostenible de la comunidad de Ligüiqui en Manta, Ecuador. ROTUR Rev. Ocio Tur. 2020, 14, 1–22. http://doi.org/10.17979/rotur.2020.14.1.5849. [CrossRef]

- Lucas-Mantuano, C.A.; Salazar-Olives, G.; Loor-Caicedo, C.K. El emprendimiento social en el turismo comunitario de la provincia de Manabí, Ecuador. Telos Rev. Estud. Interdiscip. Cienc. Soc. 2019, 21, 661–680. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=7041198. (Accessed on 5 April 2024).

- Alvarado, R. El turismo rural y el desarrollo local sostenible desde la percepción de los pobladores de la parroquia Ingapirca. Rev. Publicando 2022, 33, 67–86. http://doi.org/10.51528/rp.vol9.id2278. [CrossRef]

- Calvo-Vélez, D. Modelos Teóricos y Representación del Conocimiento. Tesis Doctoral, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Madrid, Spain, 2006. Available online: https://eprints.ucm.es/id/eprint/7367/. (Accessed on 8 April 2024).

- De Oliveira-Santos, G.E. Modelos teóricos aplicados al turismo. Estud. Perspect. Tur. 2007, 16, 96–110. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/1807/180713890005.pdf. (Accessed on 7 February 2024).

- De Armas-Ramírez, N.; Lorences-González, J.; Perdomo-Vázquez, J.M. Caracterización y Diseño de los Resultados Científicos como Aportes de la Investigación Educativa. En Actas del evento Internacional Pedagogía 40; Universidad de Guayaquil: Guayas, Ecuador, 2003. Available online: http://pnfe-sucre.over-blog.com/caracterizaci%C3%93n-y-dise%C3%91o-de-los-resultados-cient%C3%8Dficos-como-aportes-de-la. (Accessed on 11 February 2024).

- Tejeda, R. El aporte teórico en investigaciones asociadas a las Ciencias Pedagógicas. Didasc@ Lia Didáctica Educ. 2015, 6, 103–120. Available online: https://revistas.ult.edu.cu/index.php/didascalia/article/view/438. (Accessed on 16 February 2024).

- Trujillo-Villena, F.G. Modelo y Procedimiento de Promoción para Potenciar las Estrategias y Desarrollo del Sector Turístico. Tesis de Maestría, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador, Quito, Ecuador, 2022. Available online: https://repositorio.puce.edu.ec/server/api/core/bitstreams/a788df7c-3ab7-4f42-9f99-73e03d5d97af/content. (Accessed on 6 February 2024).

- Ollague-Andrade, N.M. Plan de Promoción Turística para la Comunidad Punta Diamante de la Parroquia Chongón del Cantón Guayaquil. Tesis de grado: Licenciado en Turismo y Hotelería, Universidad de Guayaquil, Guayas, Ecuador, 2015. Available online: http://repositorio.ug.edu.ec/bitstream/redug/8291/1/TESIS%20ORIGINAL%20NANCY.pdf. (Accessed on 8 April 2024).

- Aimacaña-Tasinchano, E.C. La Florícola Mil Rosse y su Contribución al Desarrollo del Agroturismo en la Parroquia Mulaló provincia de Cotopaxi. Tesis de grado, Universidad Técnica de Ambato, Ambato, Ecuador, 2017. Available online: https://repositorio.uta.edu.ec/bitstream/123456789/24636/1/Erika%20Consuelo%20%20Aimaca%C3%B1a%20Tasinchano%20Tesis%20Final.pdf. (Accessed on 11 February 2024).

- Castillo-Palacio, M.; Castaño-Molina, V. La promoción turística a través de técnicas tradicionales y nuevas. Una revisión de 2009 a 2014. Estud. Perspect. En Tur. 2015, 24, 737–757. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/1807/180739769017.pdf. (Accessed on 6 April 2024).

- Sánchez-Amboage, E. El Turismo 2.0. un nuevo modelo de promoción turística. Red MARKA Rev. Mark. Apl. 2018, 1, 3–57. http://doi.org/10.17979/redma.2011.01.06.4719. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, Luna M. G. Plan de Marketing digital para la promoción de sitios turísticos del cantón Mocache, provincia de los ríos, año 2022. Tesis de grado, Universidad Técnica de Babahoyo, Los Ríos Ecuador, 2023. Available online: http://dspace.utb.edu.ec/bitstream/handle/49000/13561/E-UTB-EXTQUEV-HTURIS-000025.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. (Accessed on 9 April 2024).

- Franco-Bravo, A.I.; Giraldo-Velásquez, C.M.; López-Zapata, L.V.; Palmas-Castrejón, Y.D. Modelos Sistémicos y sus Implicaciones para el Estudio de Destinos Turísticos: Aplicaciones en Casos Locales; Corporación Universitaria Remington: Medellín, Colombia, 2020. Available online: https://es.scribd.com/book/482032426/Modelos-sistemicos-y-sus-implicaciones-para-el-estudio-dedestinos-turisticos-Aplicaciones-en-casos-locales. (Accessed on 15 February 2024).

- Vitorero-Aspiazu, M.A. Diseño de un Modelo para la Gestión Turística local Sostenible en el Cantón Jipijapa, Provincia de Manabí. Tesis Licenciado en Turismo, Universidad Estatal del Sur de Manabí (UNESUM), Manabí, Ecuador, 2022. Available online: https://repositorio.unesum.edu.ec/bitstream/53000/3596/1/01%20Tesis_%20MARICARMEN%20ALEXANDRA%20VITORERO%20ASPIAZU-DISE%c3%91O%20DE%20UN%20MODELO%20PARA%20LA%20GESTI%c3%93N%20TUR%c3%8dSTICA%20LOC.pdf. (Accessed on 16 February 2024).

- Cabanilla-Vásconez, E. Turismo comunitario en América Latina, un concepto en construcción. Siembra 2018, 5, 121–131. http://doi.org/10.29166/siembra.v5i1.1433. [CrossRef]

- Mullo-Romero, E.C.; Vera-Pena, V.M.; Guillén-Herrera, S.R. El desarrollo del turismo comunitario en Ecuador: Reflexiones necesarias. Rev. Univ. Soc. 2019, 11, 178–183. Available online: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?pid=s2218-36202019000200178&script=sci_arttext. (Accessed on 9 February 2024).

- Bravo, O.; Zambrano, P. Turismo comunitario desde la perspectiva del desarrollo local: Un desafío para la Comuna 23 de noviembre, Ecuador. Rev. Espac. 2018, 39, 28. Available online: https://www.revistaespacios.com/a18v39n07/a18v39n07p28.pdf. (Accessed on 16 February 2024).

- García-Palacios, C. Turismo comunitario en Ecuador: ¿quo vadis? Estud. Perspect. Tur. 2016, 25, 597–614. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/1807/180747502011.pdf. (Accessed on 16 February 2024).

- Cabanilla, E.A.; Gentili, J. Caracterización de la oferta de Turismo Comunitario en internet. Una aproximación desde el análisis de contenido y la cartografía temática. PASOS Rev. Tur. Patrim. Cult. 2014, 14, 157–174. http://doi.org/10.25145/j.pasos.2015.13.011. [CrossRef]

- Cabanilla-Vásconez, E.; Garrido-Cornejo, C. El turismo Comunitario en Ecuador. Evolución, Problemática y Desafíos; Universidad Internacional del Ecuador (UIDE): Pichincha, Ecuador, 2017. Available online: https://repositorio.uide.edu.ec/bitstream/37000/2826/1/libro%20turismo%20comunitario%20web.pdf. (Accessed on 17 February 2024).

- Navas-Ríos, M.E. Revisión Sistemática del Concepto Turismo Comunitario. Saber Cienc. Lib. 2019, 14, 144–162. http://doi.org/10.18041/2382-3240/saber.2019v14n2.5884. [CrossRef]

- Segovia-Chiliquinga, G.J. Modelo de Gobernanza para el Desarrollo de Turismo Comunitario en el Cantón Montalvo. Doctoral Tesis, Universidad Cesar Vallejo, Piura, Perú, 2022. Available online: https://repositorio.ucv.edu.pe/handle/20.500.12692/88592. (Accessed on 15 February 2024).

- Larrea, L.; López, L.; Portillo, L.D. Caracterización de la oferta y la demanda turístíca en el litoral Caribe de Antioquia-Colombia. Rev. Tur. Patrim. Desarro. (TURPADE) 2019, 10. Available online: https://revistaturpade.lasallebajio.edu.mx/index.php/turpade/article/view/43/40. (Accessed on 20 January 2024).

- López-Mielgo, N.; Loredo, E.; Sevilla-Álvarez, J. Realidad aumentada en destinos turísticos rurales: Oportunidades y barreras. Int. J. Inf. Syst. Tour. (IJIST) 2019, 4, 25–33. Available online: http://www.uajournals.com/ojs/index.php/ijist/article/view/448. (Accessed on 6 February 2024).

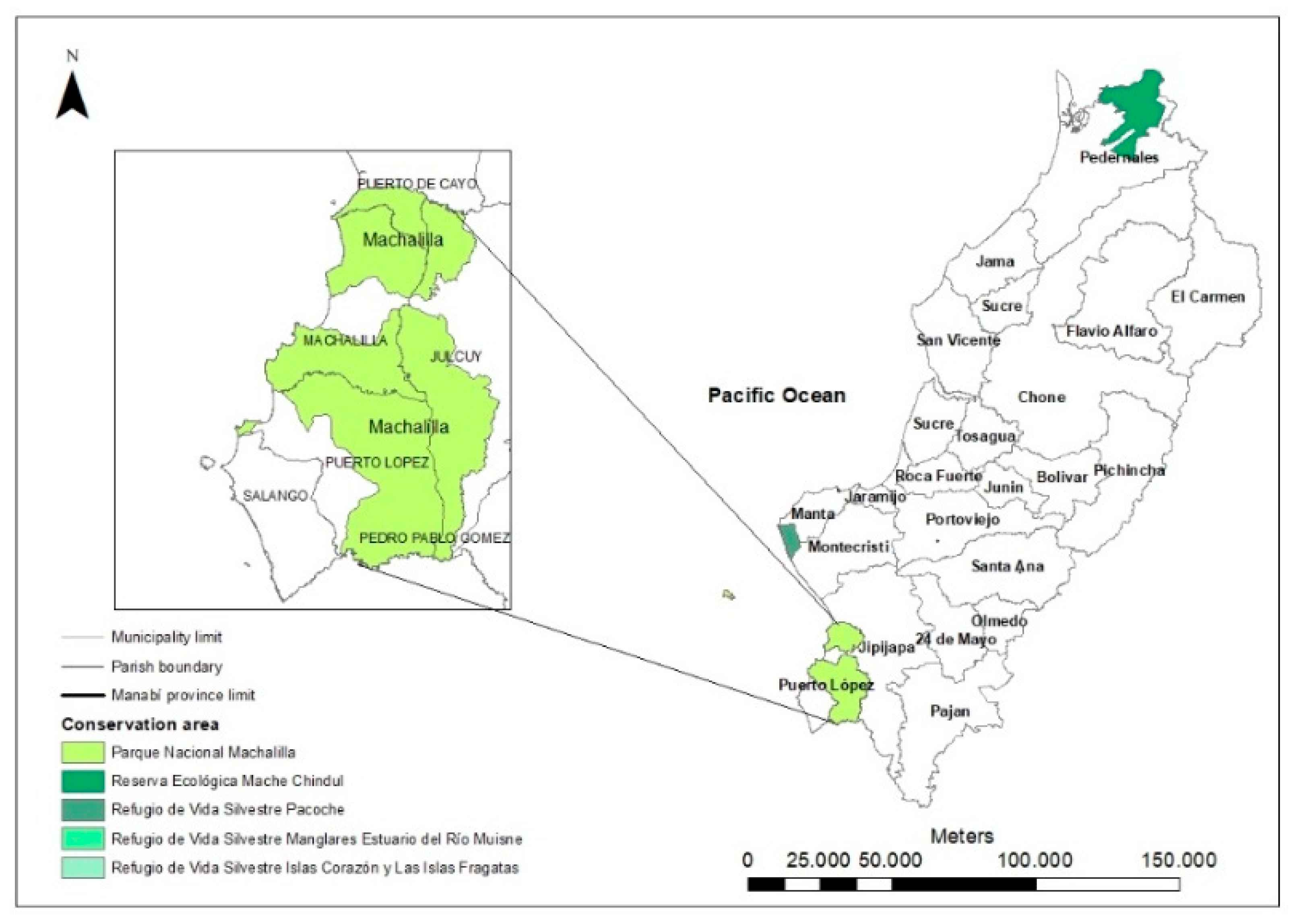

- Represa, F., y Macías-Zambrano, L. H. Sostenibilidad social en Áreas Naturales Protegidas. Estudio de caso en el Parque Nacional Machalilla (Manabí, Ecuador). Revista Científica Ciencia y Tecnología Vol 23. 2022. No 37 págs. 61- 81. http://cienciaytecnologia.uteg.edu.ec/revista/index.php/cienciaytecnologia/article/view/586. (Accessed on 12 January 2024).

- Reyes, Javier Escalera.; Esteban Ruiz Ballesteros. Resiliencia Socioecológica: aportaciones y retos desde la Antropología. Revista de antropología social 20 (2011): 109-135. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/838/83821273005.pdf. (Accessed on 12 February 2024).

- Hernández-Sampieri, R.; Fernández-Collado, C.; Baptista-Lucio, P. Metodología de la Investigación, 5th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2010. Available online: https://www.ecotec.edu.ec/material/material_2017F_CSC244_11_80241.pdf. (Accessed on 11 January 2024).

- Menoya, S.; Gómez, G.P.; Pérez, I.; Cándano, L. Modelo para la Gestión del Turismo desde el Gobierno Local en Municipios con Vocación Turística Cubanos, Basado en el Enfoque de Cadena de Valor. Caso Viñales. Retos 2017, 11, 172–204. Available online: https://pure.ups.edu.ec/en/publications/model-for-tourism-management-from-the-local-government-in-municip. (Accessed on 9 January 2024).

- Goffi, G. A. Model of Tourism Destinations Competitiveness: The Case of the Italian Destinations of Excellence; Anuario Turismo y Sociedad: Bogota, Colombia, 2013; Volume XIV, pp. 121–147. Available online: https://revistas.uexternado.edu.co/index.php/tursoc/article/view/3718/3851. (Accessed on 9 January 2024).

- Jafari, Y. Tourism models: Sociocultural aspects. Tour. Manag. 1987, 8, 151–159. http://doi.org/10.1016/0261-5177(87)90023-9. [CrossRef]

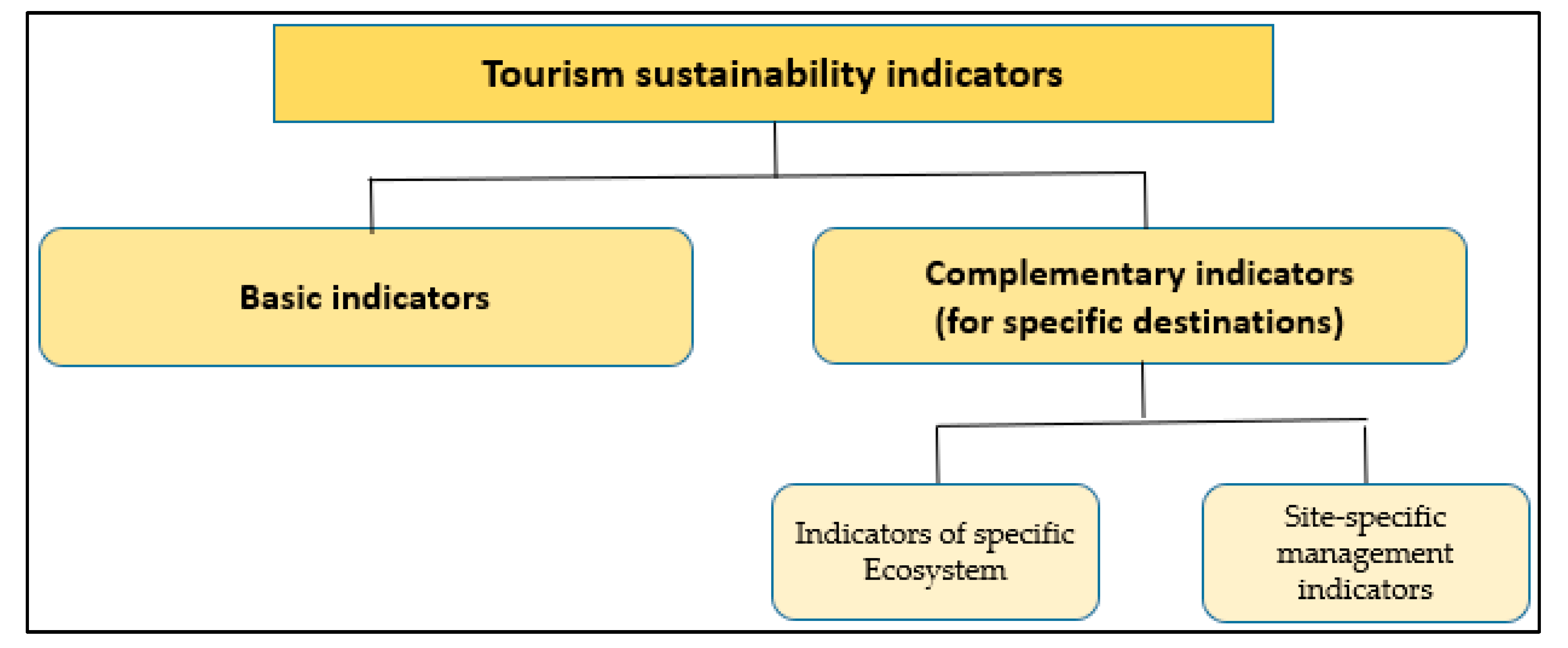

- Camacho-Ruiz, E.; Carrillo-Reyes, A.; Rioja-Paradela, T. M.; Espinoza-Medinilla, E. E. Sustainability Indicators for Ecotourism in Mexico: Current State. LiminaR vol.14 no.1 San Cristóbal de las Casas ene./jun. 2016. https://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1665-80272016000100011#:~:text=Es%20necesario%20que%20los%20indicadores,y%20aplicabilidad%20(OMT%2C%201996%3A.

- Cruz-Ramírez, M.; Martínez-Cepena, M.C. Perfeccionamiento de un instrumento para la selección de expertos en las investigaciones educativas. Revista electrónica de investigación educativa, 14(2), 2012, 167-179. https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=15525013012. Consulted: 21 January 2024.

- Marín-González, Freddy.; Pérez-González, J.; Senior-Naveda, A.; García-Guliany, J. Validación del diseño de una red de cooperación científico-tecnológica utilizando el coeficiente K para la selección de expertos. Información tecnológica 32.2 (2021): 79-88. http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0718-07642021000200079. (Accessed on 21 January 2024). [CrossRef]

- Vergel, M.; Vega, O.; Bustos, V.J. Modelo de quíntuple hélice en la generación de ejes estratégicos durante y postpandemia 2020. Rev. Boletín Redipe 2022, 9, 92–105. Available online: https://revista.redipe.org/index.php/1/article/view/1066. (Accessed on 25 January 2024).

- Carayannis, E.G.; Barth, T.D.; Campbell, D. The quintuple helix innovation model: Global warming as a challenge and driver for innovation. J. Innov. Entrep. 2012, 1, 1–12. Available online: http://transicionsocioeconomica.blogspot.com/2020/01/modelosde-quinduple-helice.html. (Accessed on 25 January 2024).

- Arocena, R.; Sutz, J. Subdesarrollo e Innovación: Una Propuesta desde el Sur: 5 (Ciencia, Tecnología, Sociedad e Innovación), 1st ed.; Ediciones Akal: Madrid, Spain, 2003; p. 95. Available online: https://www.amazon.es/Subdesarrollo-innovaci%C3%B3nPropuesta-Tecnolog%C3%ADa-Innovaci%C3%B3n/dp/8483233584. (Accessed on 26 January 2024).

- OMT. El Turismo y los Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible–Buenas prácticas en las Américas; Organización Mundial del Turismo: Madrid, Sapin, 2018; p. 56. Available online: https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/pdf/10.18111/9789284419937. (Accessed on 5 February 2024).

- Narváez, M.; Fernández, G. El turismo desde la perspectiva de la demanda. lugar de estudio: Península de Paraguaná–Venezuela. Rev. U.D.C.A, Actual. Divulg. Cient. 2010, 13, 175–183. Available online: http://www.scielo.org.co/pdf/rudca/v13n2/v13n2a20.pdf. (Accessed on 21 January 2024).

- Vieytez, J.L. Análisis de Demanda y Oferta de Turismo Alternative en la Mancomunidad La Montañona, Departamento de Chalatenango, El Salvador. Tesis de grado, Universidad Zamorano, Tegucigalpa, Honduras, 2004. Available online: https://bdigital.zamorano.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/236ed44b-0366-4869-b76a-5426f8e49955/content. (Accessed on 21 January 2024).

- López-Guzmán, T.; Borge, O.; Cerezo, J.M. Community based tourism and local socio-economic development: A case study in Cape Verde. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2011, 5, 1608–1617. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/download/88225505/article1380558839_Lopez-Guzman_20et_20al.pdf. (Accessed on 12 January 2024).

- Alonso-Dovale, M.; González-Slovasevich, C.M.; Pérez-Hernández, I. Rediseño de la modalidad de turismo de aventura en el destino de naturaleza Viñales. COODES 2021, 9, 243–257. Available online: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?pid=S2310-340X2021000100243&script=sci_arttext&tlng=en. (Accessed on 20 January 2024).

- Rivas García, Jesús.; Marta Magadán Díaz. Los Indicadores de Sostenibilidad en el Turismo. Revista de Economía, Sociedad, Turismo y Medio Ambiente - RESTMA nº 6, 2007. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Jesus-Garcia-31/publication/45702208_Los_indicadores_de_sostenibilidad_en_el_turismo/links/5b2692eb458515270fd59d57/Los-indicadores-de-sostenibilidad-en-el-turismo.pdf.

- Nasimba, C.; Cejas, M. Diseño de productos turísticos y sus facilidades. Qualitas 2015, 10, 22–39. Available online: https://www.unibe.edu.ec/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/2015-dic_NASIMBA-Y-CEJAS-DISE%C3%91O-DE-PRODUCTOSTUR%C3%8DSTICOS-Y-SUS-FACILIDADES.pdf. (Accessed on 20 January 2024).

- Pelegrín-Naranjo, L. Rediseño de la oferta de productos turísticos de naturaleza: Región Costa Sur Central de Cuba. Rev. Cienc. Soc. 2022, 28, 376–389. http://doi.org/10.31876/rcs.v28i.38171. [CrossRef]

- Pelegrín-Naranjo, L.; Pelegrín-Entenza, N.; Vázquez-Pérez, A. An analysis of tourism demand as a projection from the destination towards a sustainable future: The case of Trinidad. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5639. http://doi.org/10.3390/su14095639. [CrossRef]

- Gómez, G. Procedimiento metodológico de diseño de productos turísticos para facilitar nuevos emprendimientos. RETOS. Rev. Cienc. Adm. Econ. 2014, 4, 158–171. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/5045/504550659004.pdf. (Accessed on 20 January 2024).

- Muro, M.N.; Saravia, M.C. Tourist products methodology for its elaboration: Cultural and historical product in the coast district. Herit. Res. 2019, 2, 123–156. Available online: http://www.jthr.es/index.php/journal/article/view/34. (Accessed on 18 January 2024).

- Mujica-Chirinos, N.; Rincón-González, S. Consideraciones teórico-epistémicas acerca del concepto de modelo. Telos Rev. Estud. Interdiscip. Cienc. Soc. 2011, 13, 51–64. Available online: http://ojs.urbe.edu/index.php/telos/article/view/1880. (Accessed on 18 January 2024).

- Pin-Figueroa, W.J.; Pita-Lino, A.E.; Santos-Moreira, V.T. Aspectos teóricos para la gestión sostenible del turismo rural en la zona Sur de Manabí, Ecuador. RECUS. Rev. Electrón. Coop. Univ. Soc. 2018, 3, 27–33. Available online: https://revistas.utm.edu.ec/index.php/Recus/article/view/1282/1094. (Accessed on 23 January 2024).

- Bayas-Escudero, J.P.; Mendoza-Torres, M.C. Modelo de gestión para el turismo rural en la zona centro de Manabí, Ecuador. Dominio Cienc. 2018, 4, 81–102. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=6870907. (Accessed on 23 January 2024).

- Roux, F. Turismo Comunitario Ecuatoriano, Conservación Ambiental y Defensa de los Territorios.; Federación Plurinacional de Turismo Comunitario del Ecuador (FEPTCE): Quito, Ecuador, 2013; p. 322. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/download/34308252/Estudio_terr_amb.FEPTCE.Roux_F.2013.pdf. (Accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Hermosilla, K.; Peña-Cortés, F.; Gutiérrez, M.; Escalona, M. Caracterización de la oferta turística y zonificación en la Cuenca del Lago Ranco. Un destino de naturaleza en el sur de Chile. Estud. Perspect. Tur. 2011, 20, 943–959. Available online: http://www.scielo.org.ar/scielo.php?pid=S1851-17322011000400011&script=sci_arttext. (Accessed on 26 January 2024).

- Pabon-Cadavid, J.A. Gestión del conocimiento y políticas de innovación. Rev. Prop. Inmater. 2016, 22, 19. http://doi.org/10.18601/16571959.n22.02. [CrossRef]

- Acosta-Guacaneme, S.; Bautista-Bautista, C.C. Comunidades resilientes: Tres direcciones integradas. Rev. Arquit. 2017, 19, 54–67. http://doi.org/10.14718/RevArq.2017.19.2.997. [CrossRef]

- Mowforth, M.M.; Munt, I. Tourism and Sustainability: Development, Globalisation and New Tourism in the Thrid World; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2009; p. 149. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315795348. [CrossRef]

- Bernabé-Rosario, E.J. El Turismo Rural Comunitario y su Influencia en el Desarrollo Económico del Distrito de Chiquián. Tesis de Maestría, Universidad Cesar Vallejo, Piura, Perú, 2021. Available online: https://repositorio.ucv.edu.pe/bitstream/handle/20.500.12692/72442/Bernabe_REJ-SD.pdf?sequence=4&isAllowed=y. (Accessed on 8 January 2024).

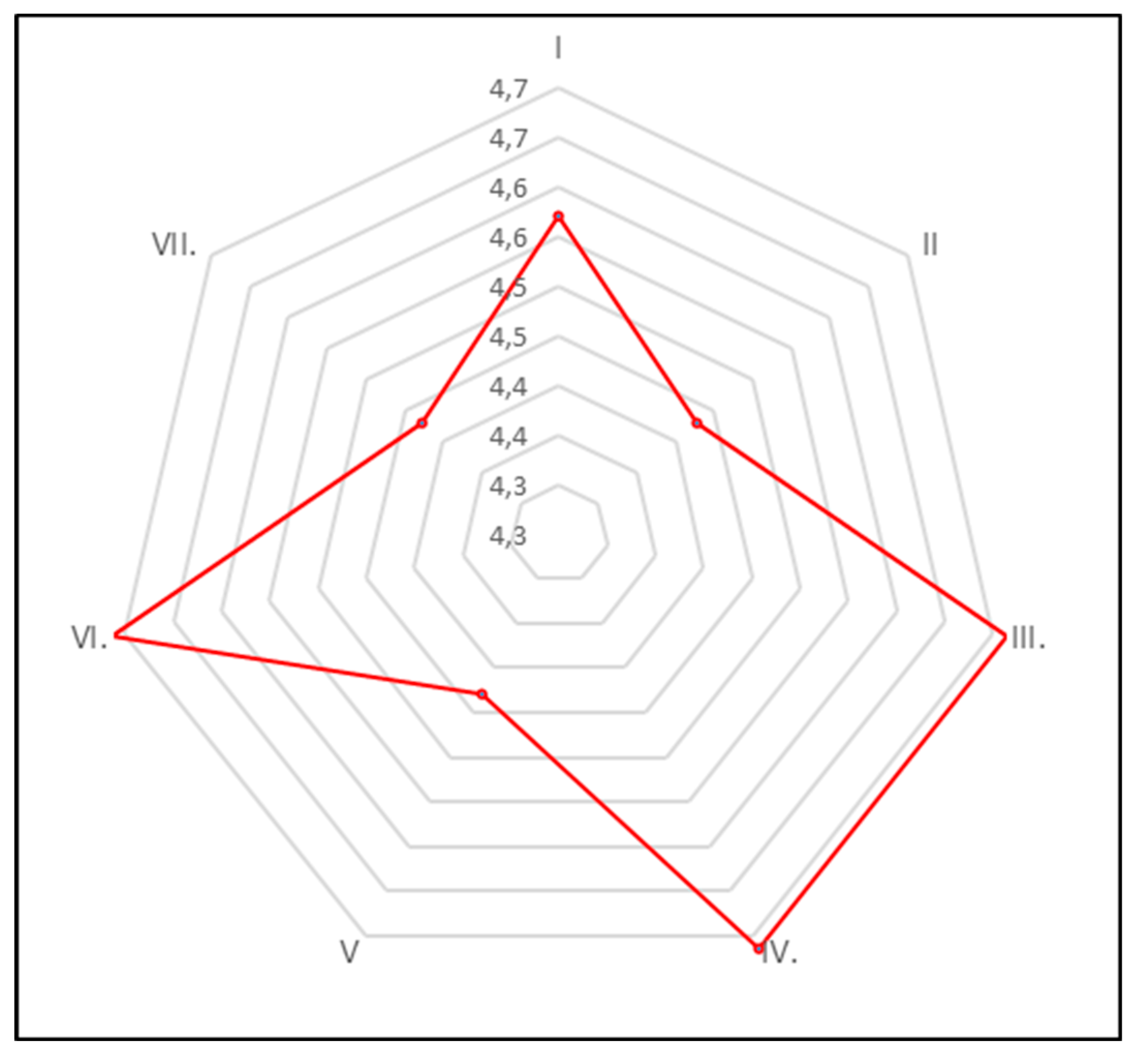

| Unit of analysis | Rating according to expert judgement |

Kendall’s W 0.207 Chi-square 8.781 Asymptotic sig. 0.183 |

||||||

| E1 | E2 | E3 | E4 | E 5 | E6 | E7 | ||

| I | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | |

| II | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | |

| III. | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |

| IV. | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |

| V | 5 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | |

| VI. | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | |

| VII. | 5 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | |

| Kendall’s W 0,090 |

Chi-square 3.808 |

Asymptotic sig. 0.700 |

||||||

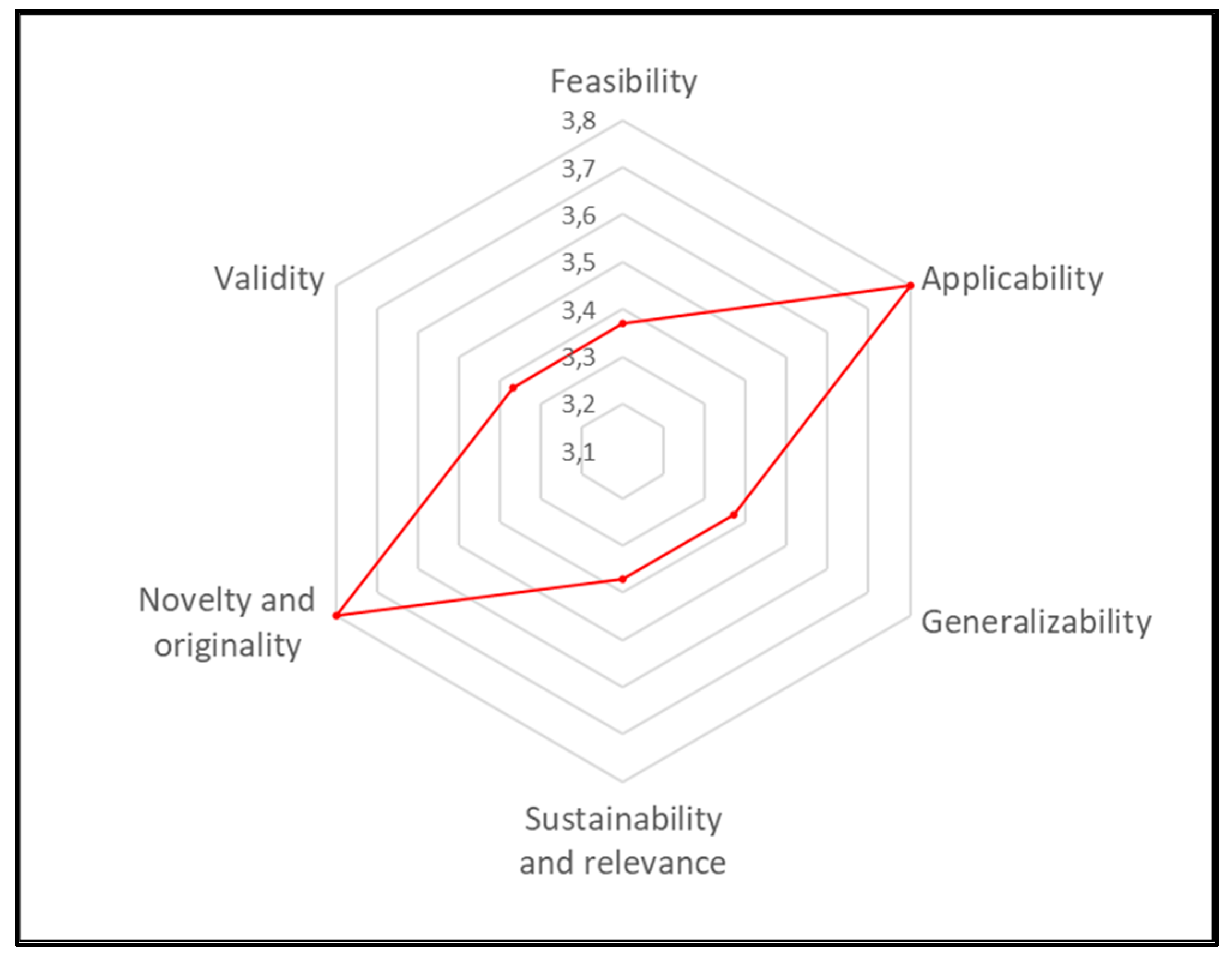

| Indicators | Rating according to expert judgement |

Kendall’s W 0.181 Chi-square 6.5 Asymptotic sig 0.37 |

||||||

| E1 | E2 | E3 | E4 | E5 | E6 | E7 | ||

| Feasibility | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |

| Applicability | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |

| Generalizability | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | |

| Sustainability and relevance | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |

| Novelty and originality | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |

| Validity | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |

| Kendall’s W 0.063 |

Chi-square 2.222 |

Asymptotic sig 0.818 |

||||||

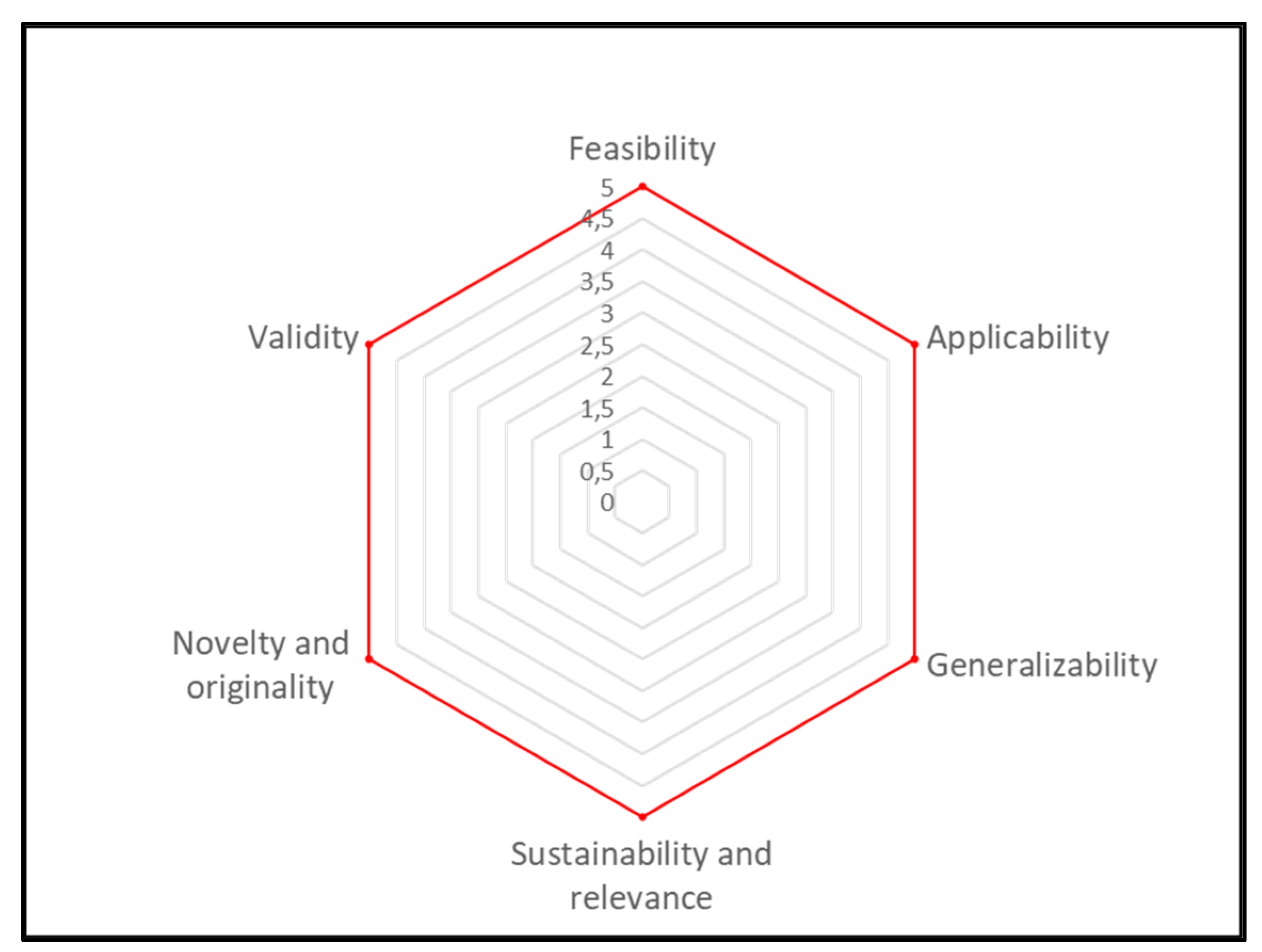

| Indicators | Rating according to expert judgement |

Kendall’s W 0.1 Chi-square 3.6 Asymptotic sig 0.731 |

||||||

| E1 | E2 | E3 | E4 | E5 | E6 | E7 | ||

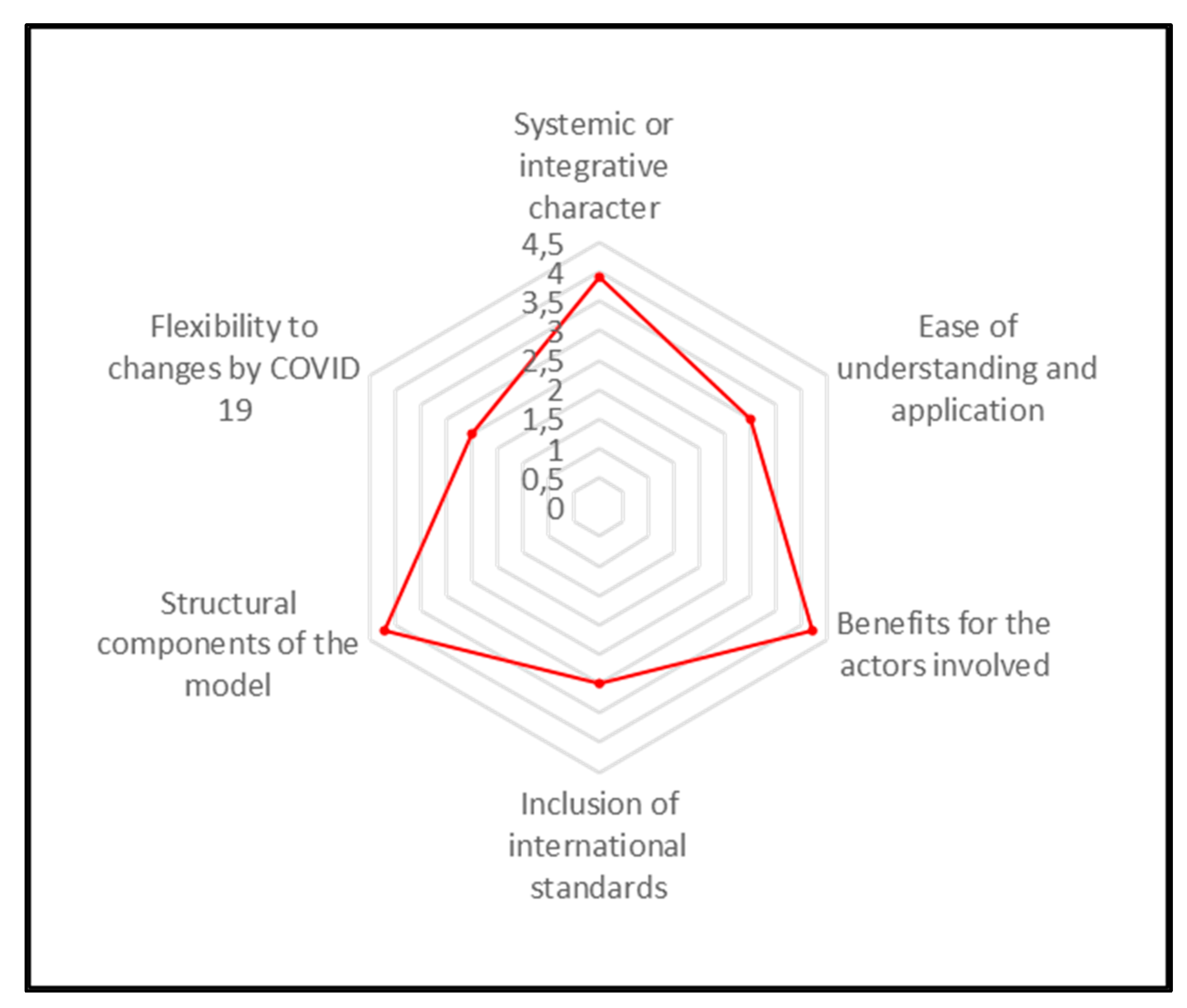

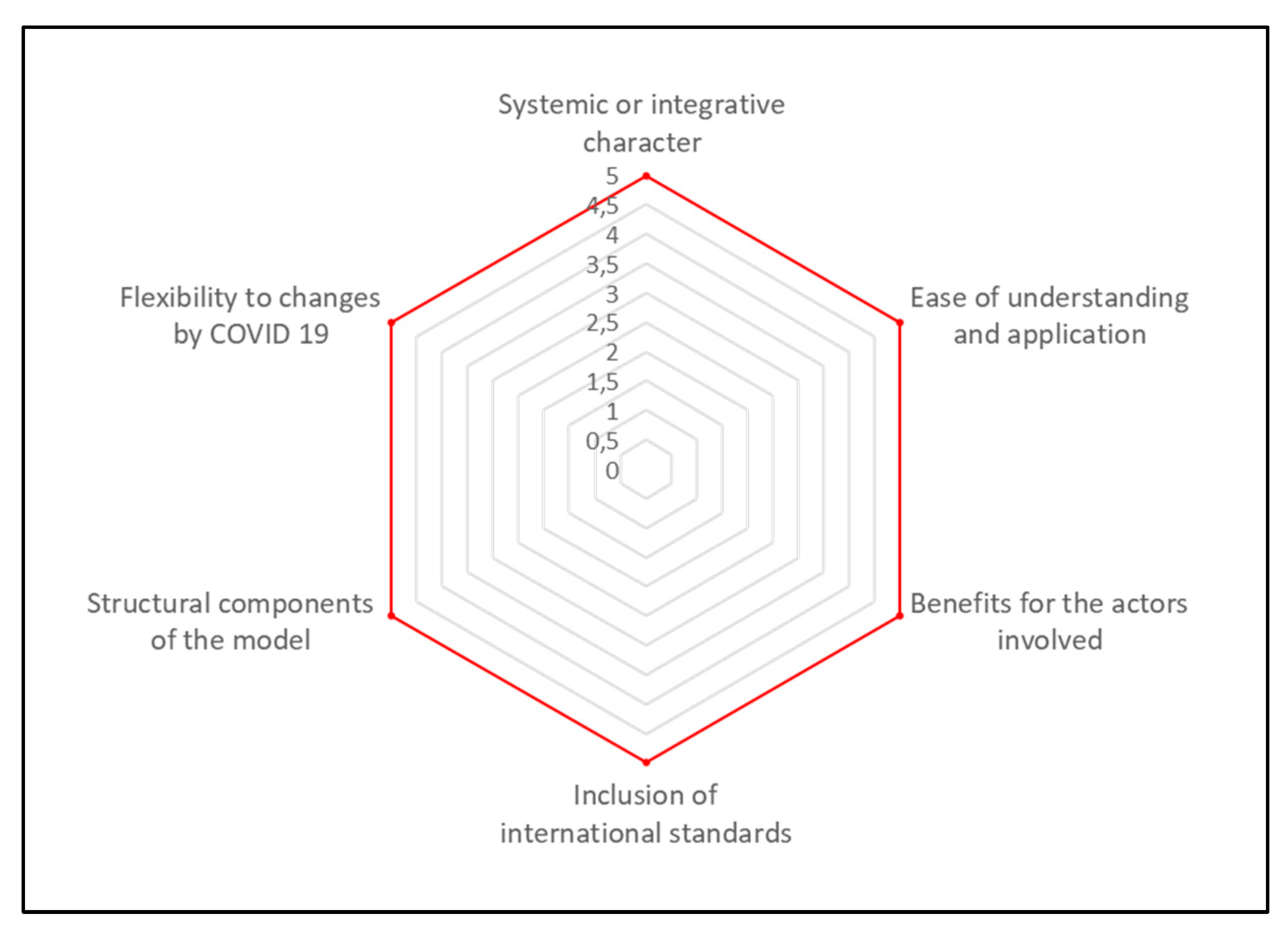

| Systemic or integrative character | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | |

| Ease of understanding and application | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 | |

| Benefits for the actors involved | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |

| Inclusion of international standards | 4 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | |

| Structural components of the model | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | |

| Flexibility to changes by COVID 19 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | |

|

Kendall’s W 0.209 |

Chi-square 7.308 |

Asymptotic sig 0.199 |

||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).