Submitted:

18 June 2024

Posted:

19 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature and Research Explaining the Causes of Suboptimal Financial Decisions Made by Consumers

2.1. Consumers’ Cognitive Biases

2.2. Modern Perception of Financial Literacy and Learning Methods - Conclusions from Research

- Learning by consequences, which is like operant conditioning, involves consciously constructing hypotheses regarding what actions, and under what circumstances, have led to desired results.

- Modeling, where behavior is based on the observation of other people’s actions and their consequences.

3. Empirical Verification of Cognitive Errors Made by Consumers on the Financial Market.

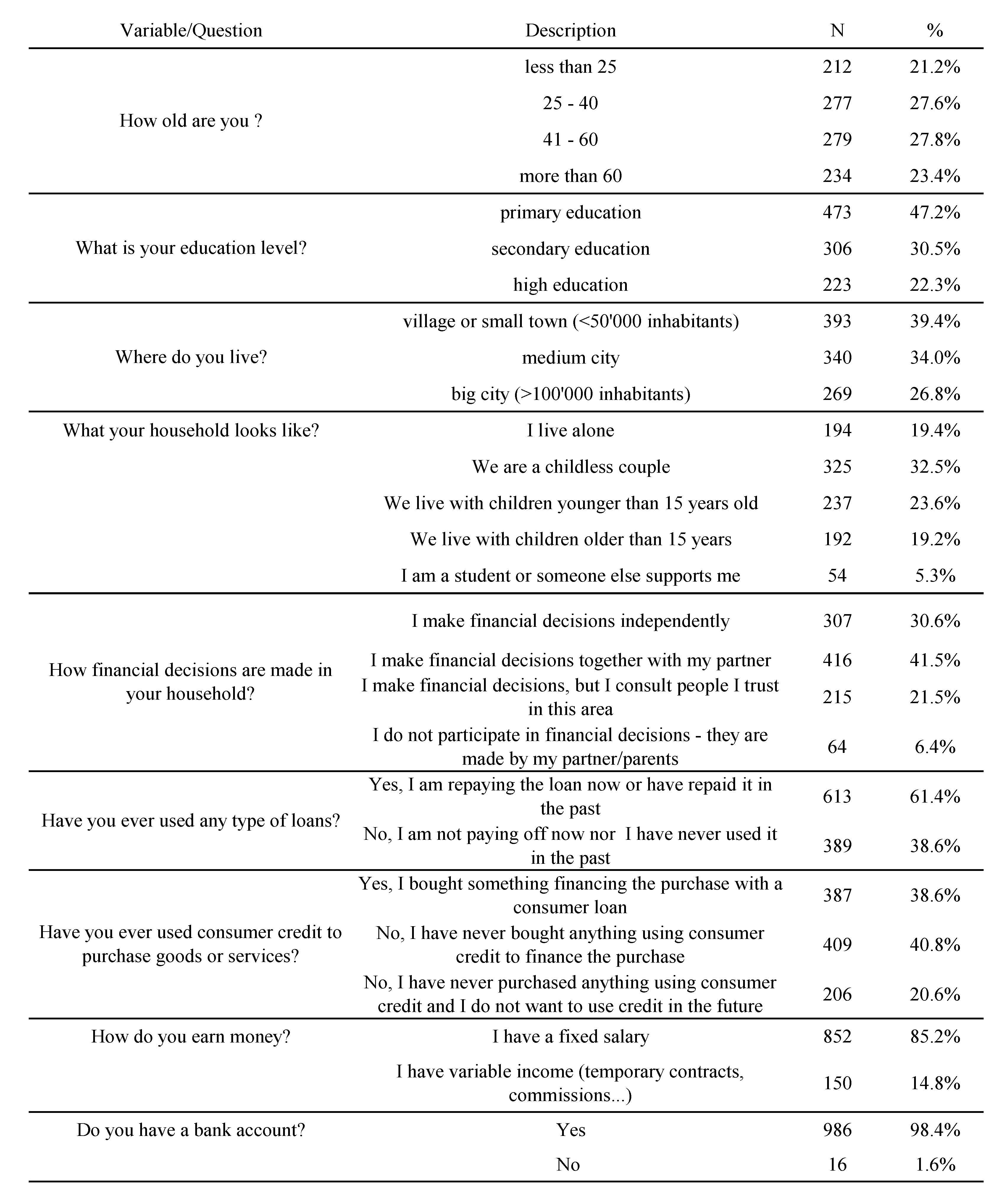

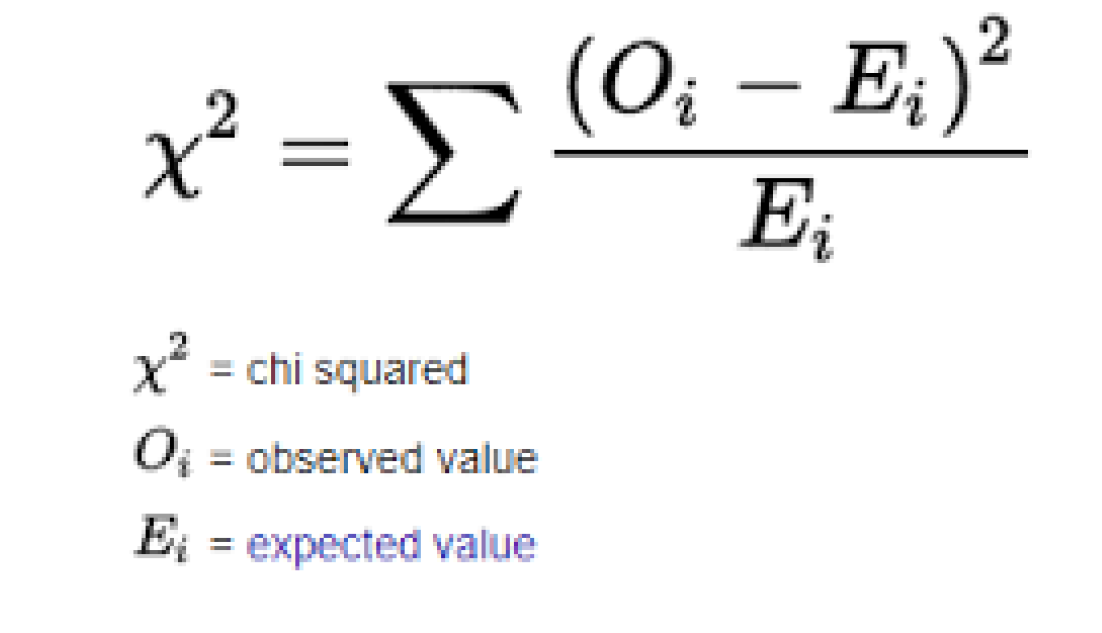

4. Methodology

- n is the number of observations,

- r is the number of levels of one variable,

- k is the number of levels of the second variable.

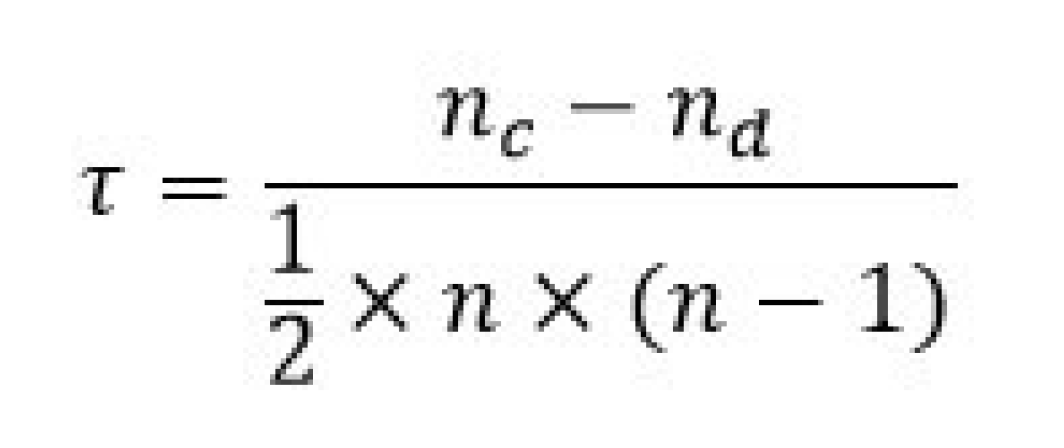

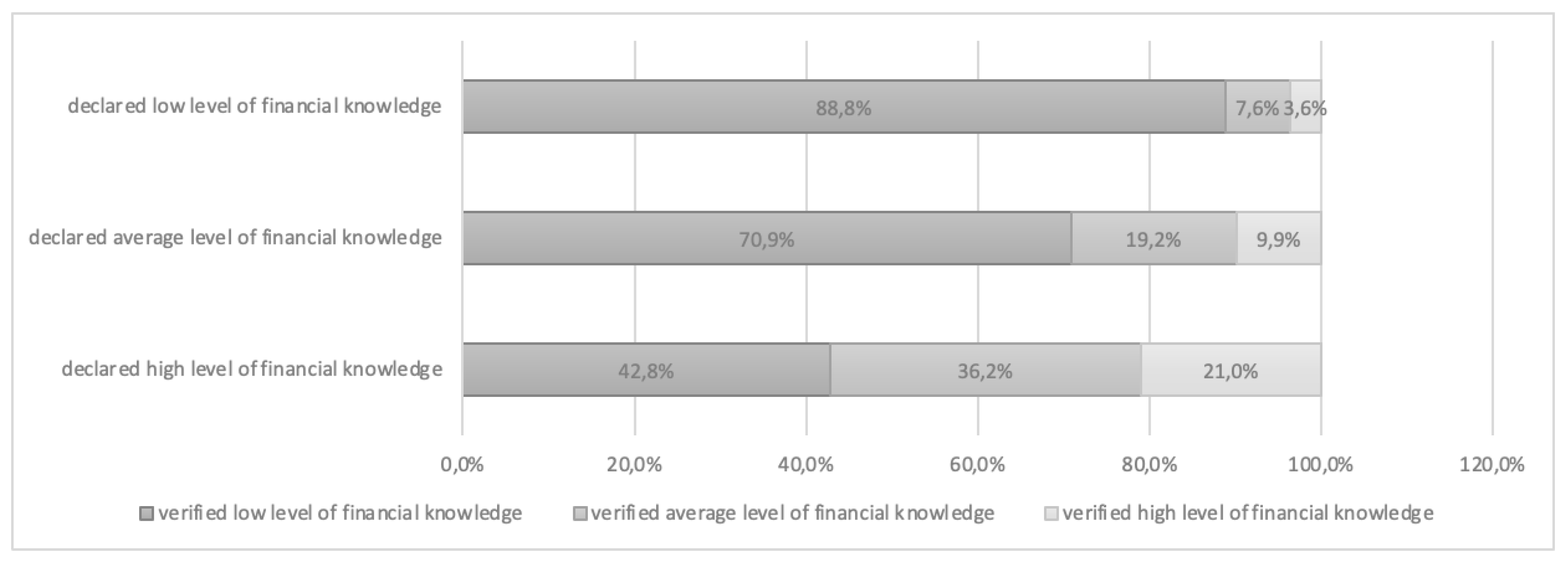

- Kendall's tau correlation analysis (a non-parametric method) for examining the relationship between two variables measured on an ordinal scale. Unlike Pearson correlation, Kendall’s Tau doesn’t rely on the assumption of linearity, making it useful for ordinal data. The study examined the relationship between consumers' self-assessment of their knowledge and the results obtained when answering verification questions (Graph 1).

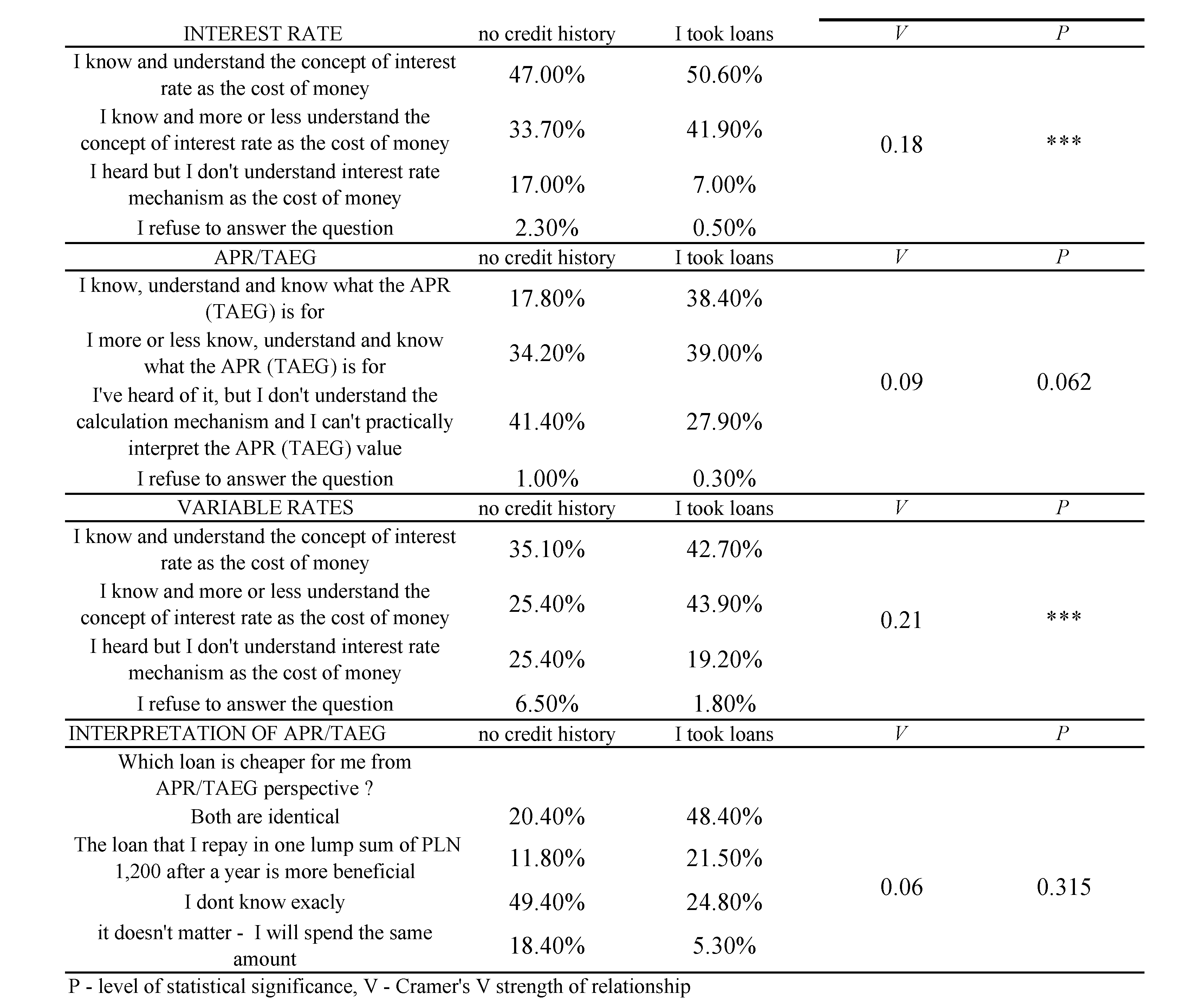

5. Financial Literacy & Financial Behavior – Observations

- a one-off repayment of the entire amount after one year (PLN 1,200)

- repayment of the loan in 12 equal monthly instalments of PLN 100 each

6. Results and Discussions by Topic and Globally

6.1. Examined Relationships

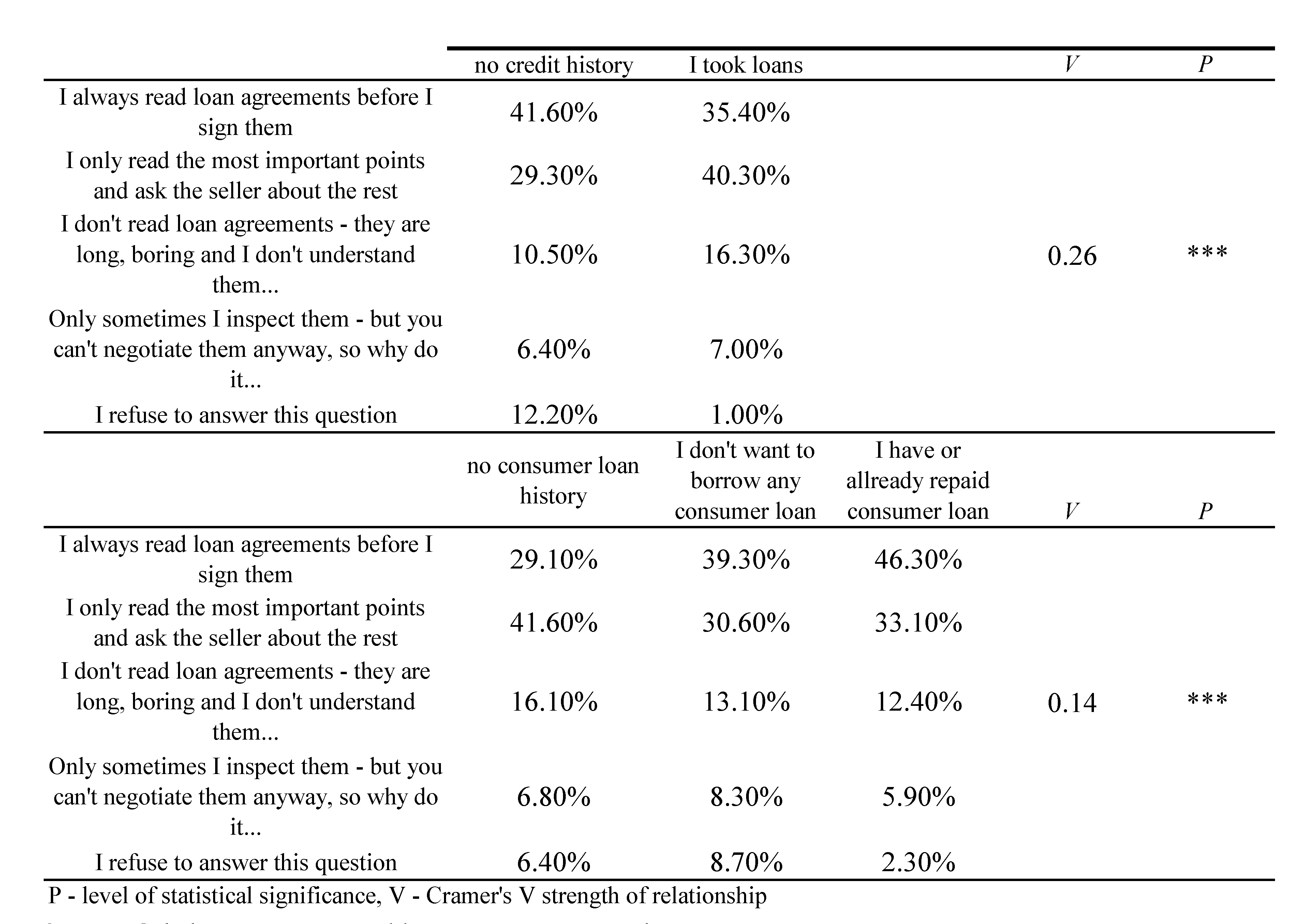

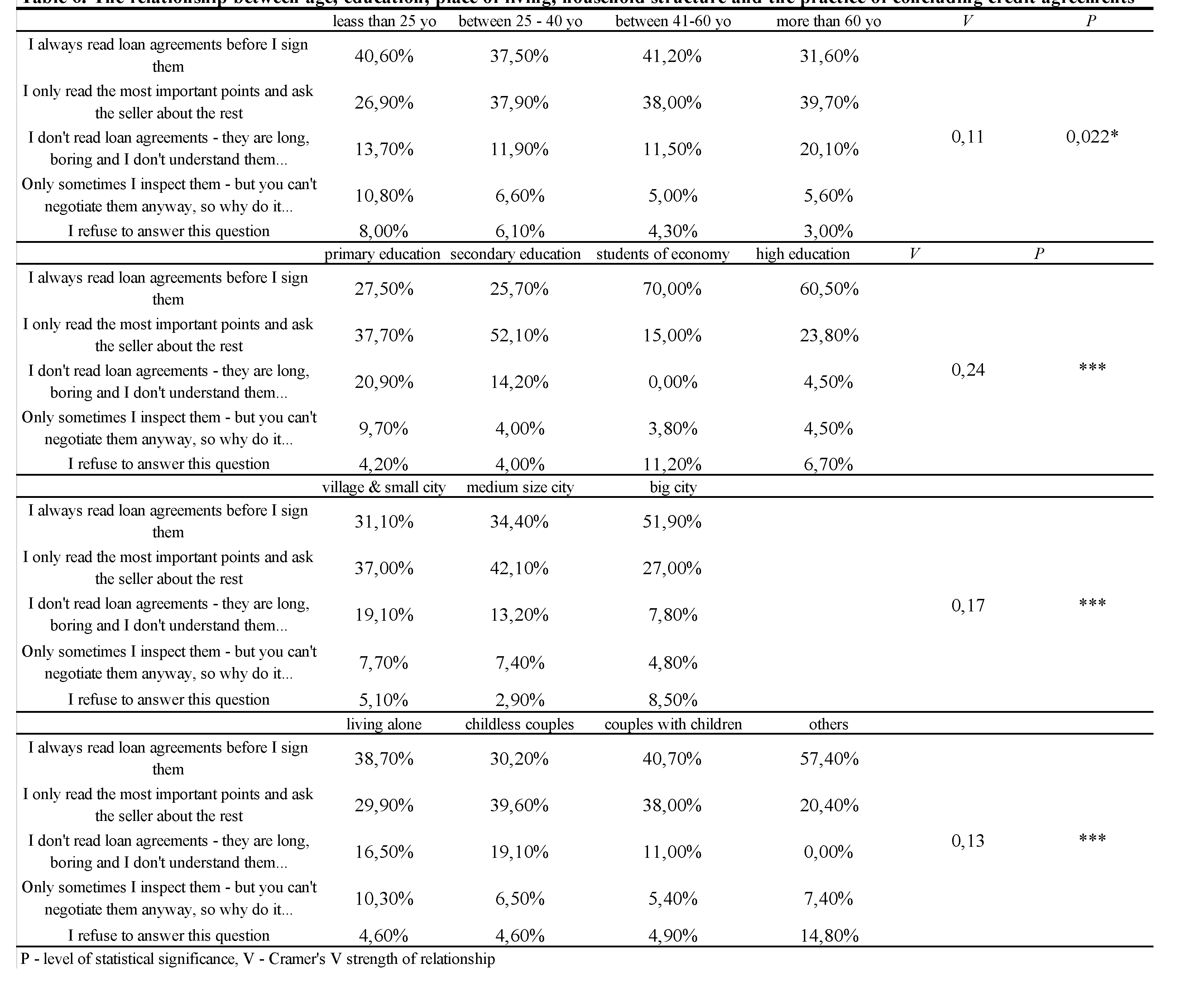

- Those who claimed that they carefully read loan agreements tended to be young people up to 25 years of age, as well as those with higher education.

- there was a statistically significant relationship between approach taken to signing consumer loans and place of residence and household. Those living in large cities and raising children or were themselves dependent on someone else were more likely to carefully read credit agreements.

6.2. Overall Financial Literacy

- nearly 36% of the respondents elect not to personally verify the terms of a loan agreement, relying on the salesperson’s opinions and recommendations. Such people are significantly exposed to the framing effect and possible consequences of information asymmetry.

- analysis of preferences regarding the method of loan repayment (one-off or instalments) revealed that mental accounting strongly influences consumers’ credit decisions, which is justifiable and rational from the perspective of consumer households. Subconsciously, consumers assume that their household budgets lack income flexibility and prefer solutions that ensure ongoing liquidity for the household.

- At the same time, when choosing a product or service, consumers are influenced by supposedly irrelevant factors such as the advisor’s suggestions, peer pressure or opinions commonly repeated on social media. This applies to young people especially (<25 years old) and those who have cash – in the questionnaire they tended to answer that they were indifferent to the choice of repayment method or preferred to pay ‘as late as possible’;

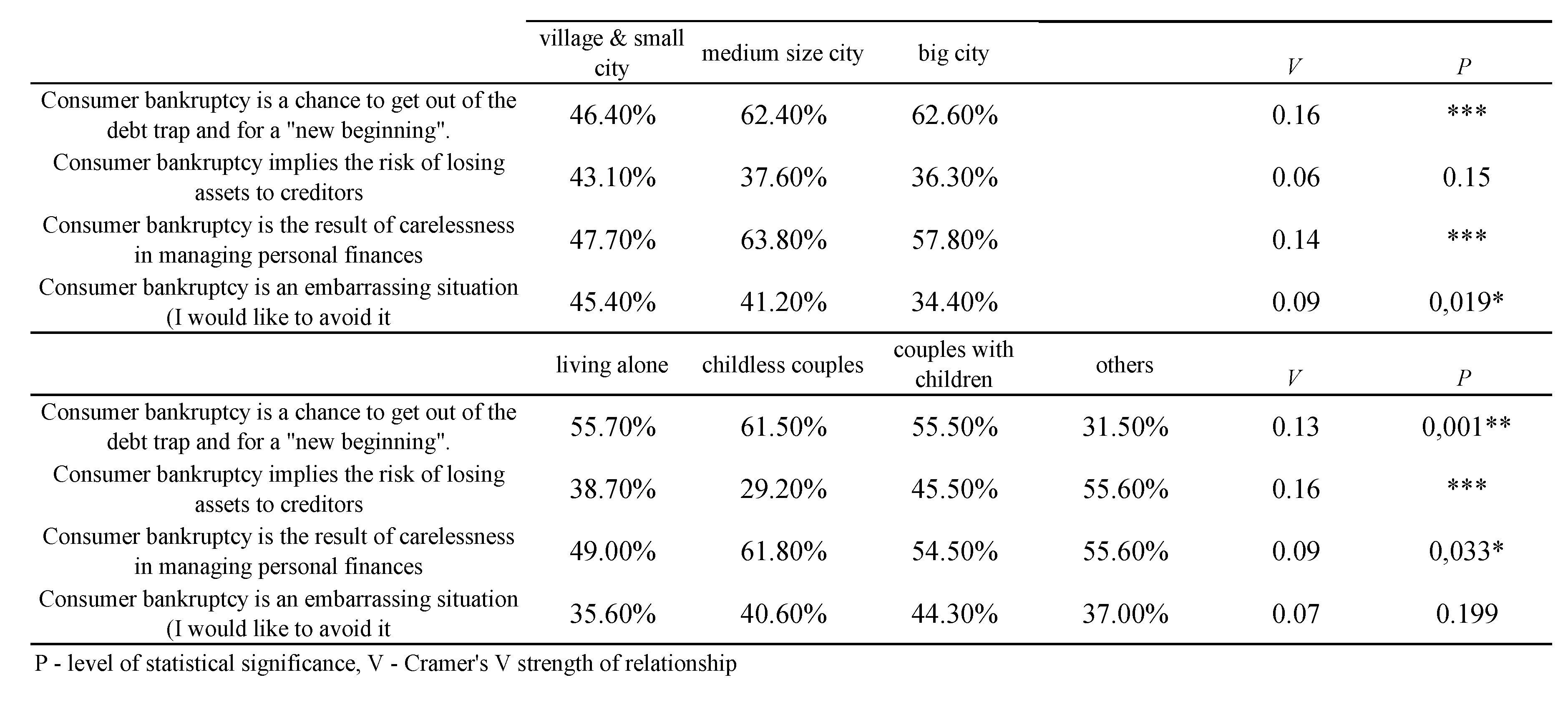

- the ease with which respondents treated consumer bankruptcy as an opportunity for a ‘fresh start’, while ignoring the costs of restructuring (involving one’s own assets to repay part of the debt) is an example of hyperbolic discounting.

7. Conclusions

References

- Amagir, A. , Groot, W., Maassen van den Brink, H., & Wilschut, A., A review of financial-literacy education programs for children and adolescents. Citizenship, Social and Economics Education. [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. , (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory, National Inst of Mental Health, Prentice-Hall, Inc.

- Böhm, P. , Böhmová, G., Gazdíková, J., & Šimková, V. Determinants of financial literacy: Analysis of the impact of family and socioeconomic variables on undergraduate students in the slovak republic. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 2023, 16, 252. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. , Ecology of the family as a context for human development: Research perspectives. Developmental Psychology 1986, 22, 723–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkhauser, R. , Gustman, A., Laitner, J., Mitchell, O., Sonnega, A. (2009), Social Security Research at the Michigan Retirement Research Center, 69 Social Security Research Bulletin 51.

- Cwynar, A. (2021). Financial literacy and financial education in Eastern Europe. The Routledge Handbook of Financial Literacy, 400-419.

- Dudchyk, O. , Matvijchuk, I., Kovinia, M., Salnykova, T., & Tubolets, I. (2023). Financial literacy in Ukraine: from micro to macro level.

- Eagly, A. , (1987), Sex differences in social behaviour: A social-role interpretation, Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Frame, W. S. , Wall L., i White, L. J., (2019) Technological Change and Financial Innovation in Banking: Some Implications for FinTech, (in) Oxford Handbook of Banking, 3rd ed., edited by A. Berger, P. Molyneux, and J. O. S. Wilson, s. 262–284, Oxford University Press.

- Hastings, J. , and Mitchell, O. S., (2018), How Financial Literacy and Impatience Shape Retirement Wealth and Investment Behaviors, Wharton Pension Research Council Working Papers, Number 13.

- Hausman, D.M. Rational Choice and Social Theory: A Comment. Journal of Philosophy 1995, 92, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hergár, E, Kovács, L and Németh, E., (2024) The Status and Development of Financial Literacy in Hungary. Financial and Economic Review, 23 (1). pp. 5–28. ISSN 2415-9271.

- Holmes, N. M. , Chan, Y. Y., & Westbrook, R. F. An application of Wagner’s Standard Operating Procedures or Sometimes Opponent Processes (SOP) model to experimental extinction. Journal of Experimental Psychology 2020, 46, 215–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hundtofte, S. , Gladstone J., (2017), Who Uses a Smartphone for Financial Services? Evidence of a Selection for Impulsiveness from the Introduction of a Mobile FinTech App, Federal Reserve Bank of New York Working Paper.

- Kahneman D, Ketsch J and Thaler R <italic>Journal of Political Economy</italic>. <bold>1990</bold>, <italic>98</italic>, 1325–1348.

- Krechovská, M. (2015). Financial literacy as a path to sustainability, Publisched online 2015, https://fek.zcu.cz/tvp/doc/2015-2. 20 May.

- Lusardi, A., (2008), Financial Literacy: An Essential Tool for Informed Consumer Choice, Working Paper No 14084, National Bureau of Economic Research, https://www.nber.org/papers/w14084 (accessed on December 2023).

- Lusardi, A. , & Mitchell, O. S., (2014), The economic importance of financial literacy: Theory and evidence, Journal of Economic Literature, 52(1), s.5–44. [CrossRef]

- Lusardi, A. , Michaud P. C., i Mitchell O. S. Optimal Financial Knowledge and Wealth Inequality. Journal of Political Economy 2017, 127, 431–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lusardi, A. , Mitchell, O.S., (2013) The Economic Importance of Financial Literacy: Theory and Evidence, Discussion Paper Netspar.

- Maison D., (2023). https://www.linkedin.com/posts/dominika-maison_wiedza-ekonomiczna-polaków-activity-7155467065988898816-eYFN/?originalSubdomain=pl (dostęp luty 2024).

- Mcelroy, T. , & Seta, J., (2003), Framing Effects: An Analytic-Holistic Perspective, Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 39, 610-617. [CrossRef]

- Moschis, G. P. , Churchill, G. A. Consumer socialization. A theoretical and empirical analysis. Journal of Marketing Research 1978, 15, 599–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitoi, M., Clichici, D., Zeldea, C., Pochea, M., Ciocirlan C (2022), Financial well-being and financial literacy in Romania: A survey dataset, Data in Brief, 43 , 108413, https://www.sciencedirect.com/ science/article/pii/S2352340922006102.

- OECD/INFE (2016). International Survey of Adult Financial Literacy Competencies.

- OECD/INFE (2020). International Survey of Adult Financial Literacy.

- Opletalová, A (2016), Financial Education and Financial Literacy in the Czech Education System, Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 171,1176-1184, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science /article/pii/S1877042815002591?

- Panos, G. A. Karkkainen, T. i Atkinson, A., (2019), Financial Literacy and Attitudes to Cryptocurrencies, Working Papers in Responsible Banking & Finance 2019, WP Nº 20-002,. [CrossRef]

- Rich, A. S. , & Gureckis, T. M., (2018), The limits of learning: Exploration, generalization, and the development of learning traps, Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 147(11).

- Rose, G. , Dalakas, V., Kropp, F. Consumer socialization and parental style across cultures: Findings from Australia, Greece, and India. Journal of Consumer Psychology 2003, 13, 366–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusek, J. , (2022), Analiza efektu odwrócenia preferencji w procesie dyskontowania społecznego, Warsaw University Press, https://ornak.icm.edu.pl/bitstream/handle/item/4509/0000-DR-172069-praca.pdf?sequence=1. (accessed on 13 December 2023).

- Schlinger, D. H. , (2009), Theory of Mind: An Overview and Behavioral Perspective. The Psychological Record, 59, 435-448. [CrossRef]

- Skinner, B.F., (1957), Verbal behaviour, Appleton-Century-Crofts. [CrossRef]

- Thaler, R. H. (2004), Mental Accounting Matters, (in) Camerer, C. F., Loewentein, G., & Rabin M., (Eds.), Advances in Behavioral Economics (pp. 75–103). Princeton University Press. [CrossRef]

- Thaler, R. H. , (2015), Misbehaving: The making of behavioural economics, W W Norton & Co.

- Thaler, R. H. , (2015), Unless You Are Spock, Irrelevant Things Matter in Economic Behavior, The New York Times, 08/05/2015. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/05/10/upshot/unless-you-are-spock-irrelevant-things-matter-in-economic-behaviour.html?smid=url-share. (accessed on 12 February 2024).

- Tversky, A. , & Kahneman, D. The framing of decisions and therationality of choice. Science 1981, 221, 453–458. [Google Scholar]

- van Rooij, M., Lusardi, A., Alessie, R., (2007), Financial Literacy and Stock Market Participation, Working Paper No 13565, National Bureau of Economic Research, https://www.nber.org/papers/w13565 (accessed on December 2023).

| 1 | The structure of the test may lead to some incorrect answers. In an experiment I conducted in 2021 on a group of 70 economics students during a colloquium, the test was arranged in such a way that only ‘A’ answers were correct (the students had 4 options ranging from A to D). Even the best in the group made a lot of mistakes by selecting different answers, thinking that the test could not possibly only have correct ‘A’ answers. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).