The Baga Oigor complex encompasses the extensive petroglyphic rock art concentrations of Baga Oigor Gol (river) and its chief tributary, Tsagaan Salaa. These conjoined valleys lie at the far northwestern border of Mongolia dividing it from the Russian Altai Republic. Together with two complexes to the south—those in the long valley of Tsagaan Gol and on the hill of Aral Tolgoi—the Baga Oigor complex includes thousands of individual images and multi-image compositions spanning a period of approximately 12,000 years. These complexes thus offer a vast and priceless storehouse of artistic and cultural documentation within the Altai Mountains at the juncture between North and Central Asia. Given the quantity and quality of the pictorial materials in the Baga Oigor complex, it would be possible to dwell on its aesthetic significance and its reflection of social values and life ways over a period of several thousand years. In this discussion, however, I will focus on one particular image type, that of Alces alces (moose) and the ways in which its appearance and pictorial contexts reveal significant aspects of a radically changing paleoenvironment. That material, hitherto largely ignored, should clarify our understanding of the character and dating of cultural change at the heart of Asia.

The materials on which this study is based were gathered over a period of approximately twenty years of field work in the Altai Mountains of Mongolia and Russia. Working within the context of two major projects—the Joint Mongolian/American/Russian Project, Altay, and the Mongolian Altai Inventory Project—the author and her colleagues identified, recorded, and ultimately mapped the rich cultural heritage of the Baga Oigor valley and of several other valleys in Bayan Ölgiy aimag. At this time, Mongolian scholars are continuing to enlarge the rock art record of the Baga Oigor region; to date, however, there have been no other attempts to reconsider paleoenvironment and culture in the northern Altai region and no consideration at all of the image of the moose and its signification.

Alces alces, otherwise known in North America as moose and in Europe as elk, is the largest cervid inhabiting the Northern Hemisphere (see Wikipedia: Moose). Although specific aspects of the animal vary according to geographical region, it is everywhere of considerable height and weight. When mature, a male may weigh more than 380 kg and stand at the shoulder more than 2.0 m. The bulls annually regrow huge antlers that may be either palmate or cervine in character. They also carry a distinctive “bell” hanging from their throats. Both sexes are distinguished by a heavy head, large ears that offer stereophonic hearing, and a large and prehensile upper lip with which they grab and tear at vegetation and branches. Both males and females have high shoulders, which in males have the appearance of a substantial hump. Moose are the only cervids capable of submerging deep into water to feed on bottom-growing plants as well as to escape the ubiquitous biting insects. In general, only female animals and their offspring form small groups; by contrast, the male Alces alces is a fairly solitary animal, except during the fall rut. Despite their great size, within the area of South Siberia they are prey to such animals as wolves and brown bears. This is particularly the case with young animals.

Throughout its northern habitat, the moose is associated with riparian zones rich in deciduous foliage such as willows and birches from which they browse leaves and twigs; they also forage on the new growth of pines and extensively on aquatic plant growth. Moose avoid areas with little or no snow since those offer less of their essential riparian habitat and greater risk of predation by wolves; but they also retreat from areas of deep snow where forage is radically decreased (Dussault et al. 2005). Throughout their habitat, the movement of moose is directed by a need for food and protection; they typically move between the forest edge, with its riparian vegetation, and deeper forests, which offer protection and cooler temperatures.

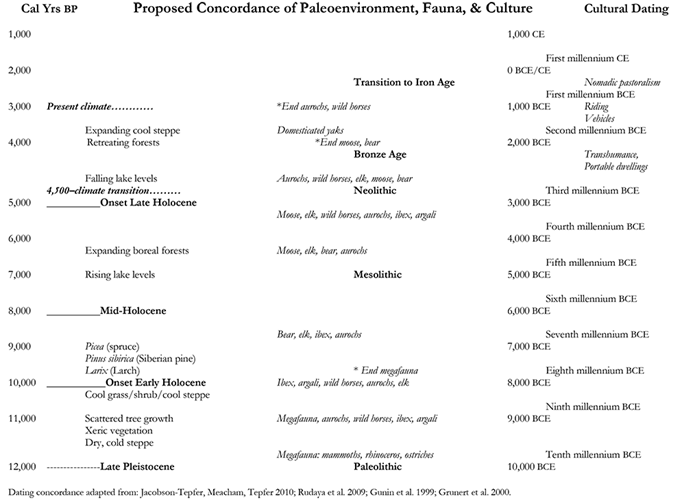

Before presenting the Baga Oigor valley itself and the pictorial material that centers this discussion, I must explain the markers I use for considering dating. These comments are necessarily brief since the subject of dating Altai rock art is complex and multi-layered. Here I will try to summarize what I have written about at much greater length in other publications (Jacobson-Tepfer 2015, 2019). In my chronological framework, the pre-Bronze Age includes the Late Pleistocene, the Early Holocene, and the Middle Holocene (

Table 1). That long period may be dated from about 12,000 years before the present to approximately 5,000 years before the present. The Late Holocene, characterized by a drying and cooling climate, evolved by approximately 4,500 years before the present, and the transition to a climate of the near past emerged about 3,000 years ago. By then, the Altai region we will be considering had reverted to its present-day mountain-steppe, although the glaciers were then much larger than is the case today, and water courses much more extensive. Because of the lack of excavated material within the Altai region, the onset of the Bronze Age is uncertain. Within this discussion, however, the Bronze Age should be understood to have encompassed the second millennium BCE down into the first third of the first millennium BCE. Those estimations are approximate; they are all associated, however, with the transformation of the larger paleoenvironment and with the emergence of major cultural changes.

In the study of rock art there are many indicators of chronology; these must be integrated and consulted together as an indivisible gestalt. The most important indicators here include the subject and its stylistic rendering; the technical manner in which it is executed; the activities in which it is contextualized and details of weaponry and other realia. In addition, the environmental implications of animal types and human activities must be considered with reference to the prehistory of vegetation and faunal regimes. Within the Altai region, these are known primarily through numerous lakebed sediment studies conducted over the last several decades (e.g., Gunin et al. 1999, An et al. 2008; Rudaya et al. 2009).

When considering the long history of Altai rock art, one begins by identifying the subject matter, by which is meant the animal or human type represented and the nature of their interactions, if any. Over that long history, individual large animals, represented in motionless profiles, were the earliest subjects; only late in the Pleistocene were there introduced crude scenes of humans hunting animals. For a number of reasons relating to the paleoenvironment, the pictorial record is essentially blank across the Middle Holocene (Jacobson-Tepfer 2019, 2020). The next major change in human/animal interactions came with the beginning of a transhumant way of life in the early Bronze Age. This emerged with the change in climate facilitating but also necessitating seasonal movement into higher pasture. Such a change signals, of course, the development of a greater dependency on the herding of small animals; and it was made possible by the domestication of yaks and the evolution of portable dwellings (today known as ger or yurt). This major change in cultural traditions is signaled in rock art by representations of family caravans with their animals and loaded yaks. Following closely on the early appearance of herding came the short-lived subject of wheeled vehicles, driven or not and pulled or not by horses (Jacobson-Tepfer 2012). The last major change involving humans and animals came with the adoption of horse riding at the end of the Bronze Age and the appearance of mounted pastoralism by the early Iron Age.

In attempting to date any subject matter, style and the manner of execution are of paramount importance because these measures changed radically over time. The earliest imagery, that dating to the period before the Bronze Age, is characterized by motionless but realistic profile animals, often monumental in appearance and executed in contours through direct pecking (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6). This technique involved the artist directly pounding the stone surface with a heavy instrument, most certainly a heavy stone. By the early Bronze Age, animals began to be represented in silhouettes, in movement, and in groups; and the pecking became indirect, by which is meant that with one hand the artist held the pecking stone and with the other hand, the hammer stone (e.g.,

Figure 16). This method of executing an image offered much greater control over the depth and density of the pecked marks and over the contours of the subject being represented. During the Bronze Age, artists occasionally also used a fine engraving technique, most certainly with a bronze instrument. Re-patination of the pecked marks in any image can offer a significant assist in relative dating, but it is not reliable for absolute dating across contemporary imagery: location, the mineral content of the stone matrix, and ambient conditions such as moisture and dust can all affect the degree to which any mark on the stone darkens down over time.

Another set of significant indicators for dating includes clothing and, most importantly, weaponry. Again, it is possible to be fairly confident of changes in that material over time: Altai artists were careful with detailing realia and clear in representing the particular activity being represented. In the earliest scenes of hunting, figures are equipped with what look like clubs or some kind of large, curved weapons. In the early Bronze Age, we see the introduction of a long bow, which by the mid-Bronze Age was reformed as a composite bow. Because of its fabrication, this weapon was stronger and less cumbersome than the long bow; but its length would have rendered it unusable on horseback. During this period, which I consider the full Bronze Age (mid-second millennium BCE), hunters also used clubs, spears, and occasionally long knives. In the late Bronze Age and with the gradual introduction of riding, bows were gradually shortened and then reshaped into true recurve bows: short enough to be carried and used on horseback but tense enough to offer considerable thrust. With the shift in bow types, the hunter’s long quiver was transformed into a short gorytus, carried at the waist and into which fit both arrows and one or two bows (Jacobson-Tepfer 2019).

The assumption of riding by the early first millennium BCE also forced a major change in clothing (for men). Close fitting trousers and jackets had been characteristic of the Bronze Age, together with a variety of head gear that seems to have been made from furred animal skins. Women were commonly shown in long dresses, their hair arranged in plaits. Riding forced very particular changes in the male costume: men adopted the use of belted tunics, soft pants, and soft foot gear. Rounded animal skin hats were replaced by soft hoods, probably made of felt and capable of being tied under the rider’s chin.

Animal types, and the human activities of hunting, transhumant pastoralism, and riding: these all implicate a larger environmental context involving climate change and the resulting evolution of vegetation and faunal regimes; and that is what will be considered in the following discussion.

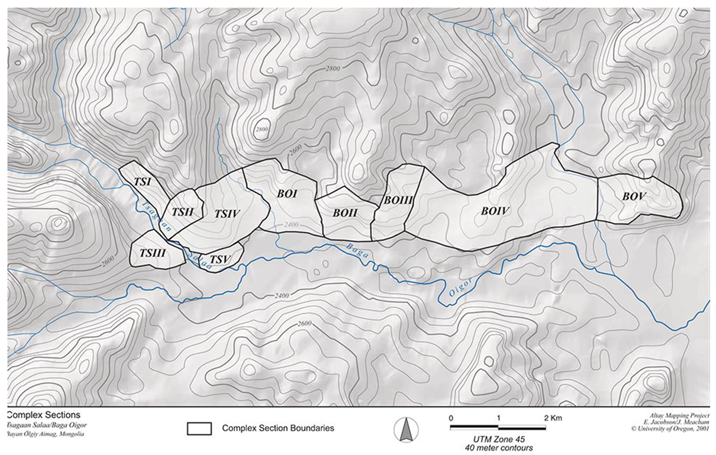

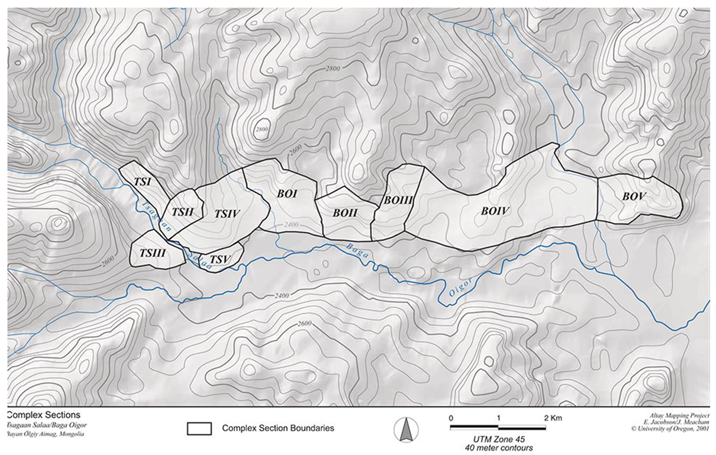

The Baga Oigor valley lies at the northwestern-most edge of Mongolia, where the Altai Mountains divide that country from its neighbor to the north, the Altai Republic of Russia. That ridge, known as Sailiugem or, in Mongolian, Siilkhem Nuuru, is the source of several rivers flowing to the south and east. The primary river in this discussion, Baga Oigor, is enlarged at the center of its course by Tsagaan Salaa, itself an outflow of two higher streams, Aksei and Usei Gol. After meandering eastward for approximately twenty-five km, the Baga Oigor is joined by both Shetya and Ikh Oigor Gol to form Oigor Gol, one of the larger rivers in Bayan Ölgiy aimag. The confluence of Tsagaan Salaa and Baga Oigor (

Figure 1) marks the western end of the main valley; at that point, its elevation is approximately 2394 m. At the point further to the east where the river leaves the broad Baga Oigor valley and enters a narrow canyon, the elevation is approximately 2288 m. Virtually all the bedrock and boulders in the valley reveal the abrasive passage of ancient glaciers.

At present, the dominant impression one has of the Baga Oigor valley is its extreme emptiness: while a few winter dwellings appear in protected folds of the slopes on both the north and south sides of the valley, there are neither towns nor any population concentration within the valley proper and nothing of any size above the administrative center of Khökh Khötel, many kilometers to the east at the end of Oigor Gol. The treeless aspect of the valley and, indeed, of the whole surrounding region certainly reflects millennia of grazing animals; but that would not account for the absolute lack of any vegetation higher than shrubs. It is rather probable that this glacier-plowed valley, like those to the north (Khar Yamaa) and south (Tsagaan Gol), has been essentially treeless for thousands of years beginning with the gradual drying of the environment during the onset of the Late Holocene. At present, there are few surviving forests in northern Bayan Ölgiy. These include forest cover on north facing slopes along the boundary with north China, south and west of Khoton Nuur. Larch forests also cover the steep, north facing slope of Shiveet Khairkhan, in the upper Tsagaan Gol. Otherwise, a few remnant larch groves cling to small draws on north-facing slopes above Khovd Gol and a few other rivers.

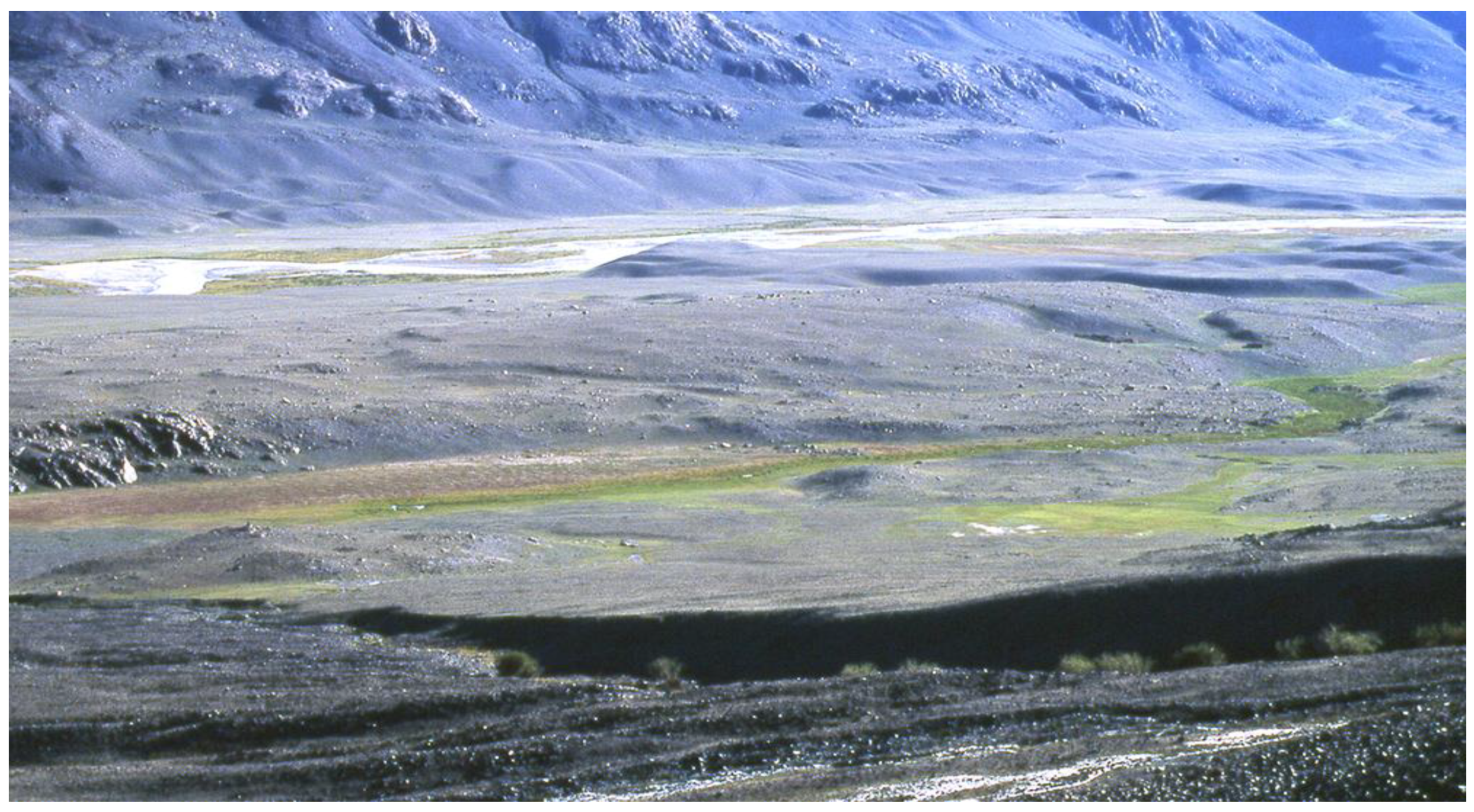

Related to the present-day treeless aspect of the Baga Oigor valley is the nature of the river course itself and of its tributary streams. A view over the valley (

Figure 2) indicates how at present the river winds through formerly marshy areas, fed by streams descending from the higher slopes, and leaving small ponds along its course. It is also apparent that none of the streams are bordered by signs of riparian growth. It is probable that animals, including yaks, horses, camels, sheep and goats, have thoroughly degraded the plant life marking the margins of streams and ponds, but that has certainly been the case for many hundreds of years, perhaps since the valley was inhabited by nomadic pastoralists in the early Iron Age.

Another aspect of the present environment is its challenging weather. The wind, snow, and low temperatures of the autumn, winter, and early spring discourage habitation except in a few, snugly located winter dwellings (

Figure 3). From there the larger animals (yaks, horses) can go higher up the slopes to graze where the wind has driven off the snow; smaller animals, however, must be protected in shelters and fed with dried hay throughout the cold months. It is certain that these harsh climatic conditions have prevailed since the beginning of the first millennium BCE, when the environment associated with the Late Holocene had been well established. In other words, this valley located in the high Altai and within the region of extreme continental conditions, has always been characterized by harsh weather patterns and the commensurate vegetation regimes.

However, despite the discouraging environmental conditions, the rock art record of this valley (like that of the valleys of Tsagaan Gol and Khar Yamaa), indicates the existence of vital cultural layers over a significant period of time. That record reveals the coming of hunters to the valleys before the Bronze Age and the kinds of animals they hunted, as well as the emergence of pastoral nomadism and the subsequent herding of large and small animals into the mountains in the second millennium BCE. It documents, finally, the appearance of full mounted nomadism by about 2700 years before the present. That same rock art is a record of the kinds of large animals found in these mountains—elk, moose, bear, aurochs, wild horses, argali, ibex, wolves, and leopards—as well as the way in which the valley’s inhabitants hunted their large game. Within that pictorial record is also visible a rich bird life, including not only large raptors but also ptarmigan, cranes, and a variety of water birds. The contrast between the empty aspect of the valley today and the life of people and animals in the past, as they are revealed on boulders and bedrock, is stark. That seeming conflict between the lived present and the envisioned past behooves us to attempt to reconstruct what this region looked like in the Bronze Age—the period most fully documented in the petroglyphic record.

Observing the present-day environment of northwest Mongolia and any description of the habitat essential for

Alces alces, it is to be wondered that there were ever any moose in the Altai region on which we are focusing. In the area around the mouth of the Tsagaan Salaa (

Figure 4), there is not a tree in sight, and the river has been reduced to a slender stream. And yet to judge from the location of surfaces decorated with images of moose, this area at the juncture of TS II, III, and IV (Map), was once rich in the kind of riparian and forest growth on which

Alces alces depends. The surviving imagery indicates that moose were commonly seen and hunted here over a period of several hundred years in the middle to late Holocene. The Baga Oigor valley must have had a vastly different aspect than we see today, the now treeless slopes covered with forest and its riverine plains much richer in streams, ponds, and all the vegetation characteristic of such habitats. Considering the pictorial material from these valleys, including the imagery of moose, stretches our understanding of the life of those valleys and the world of their ancient inhabitants.

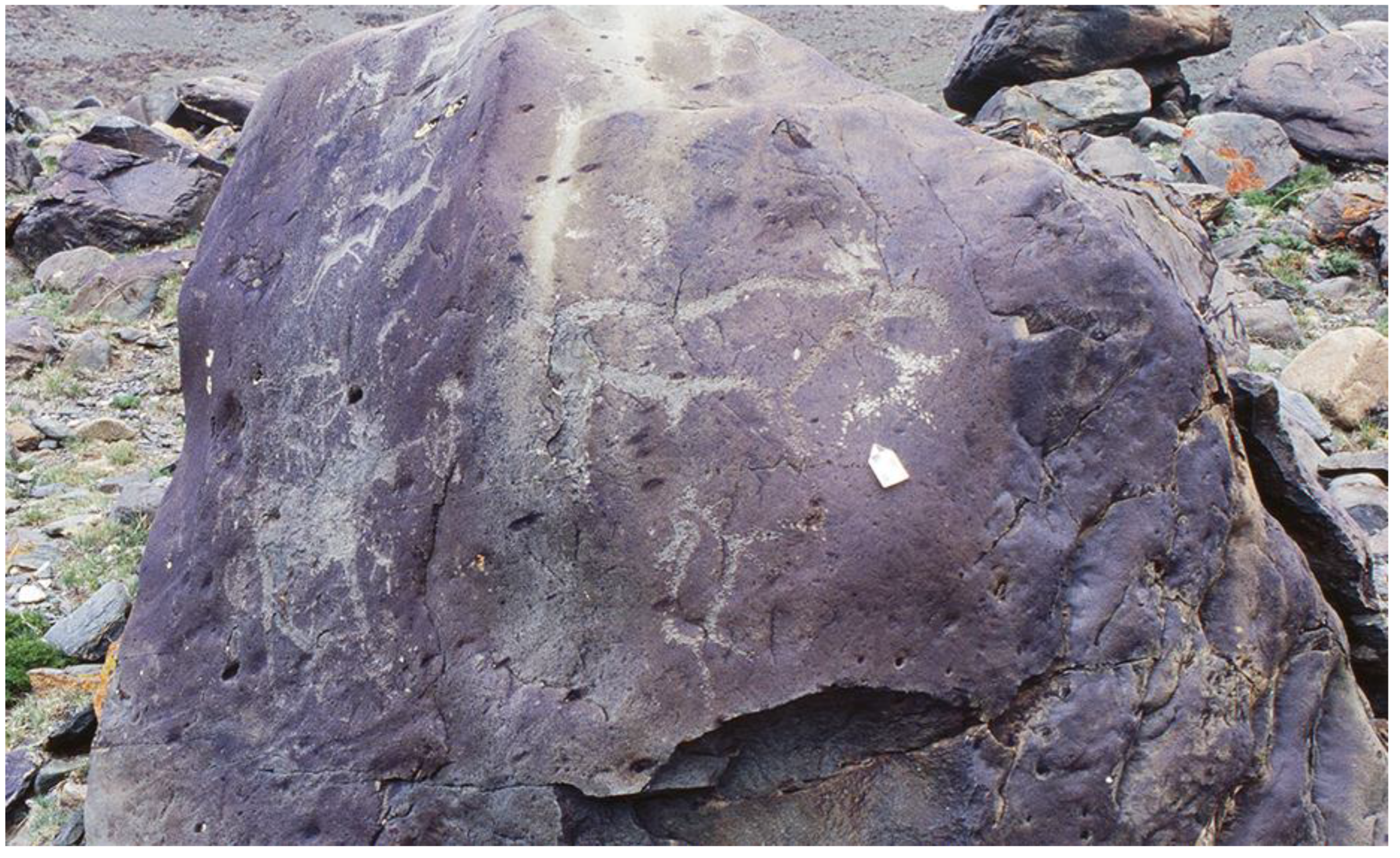

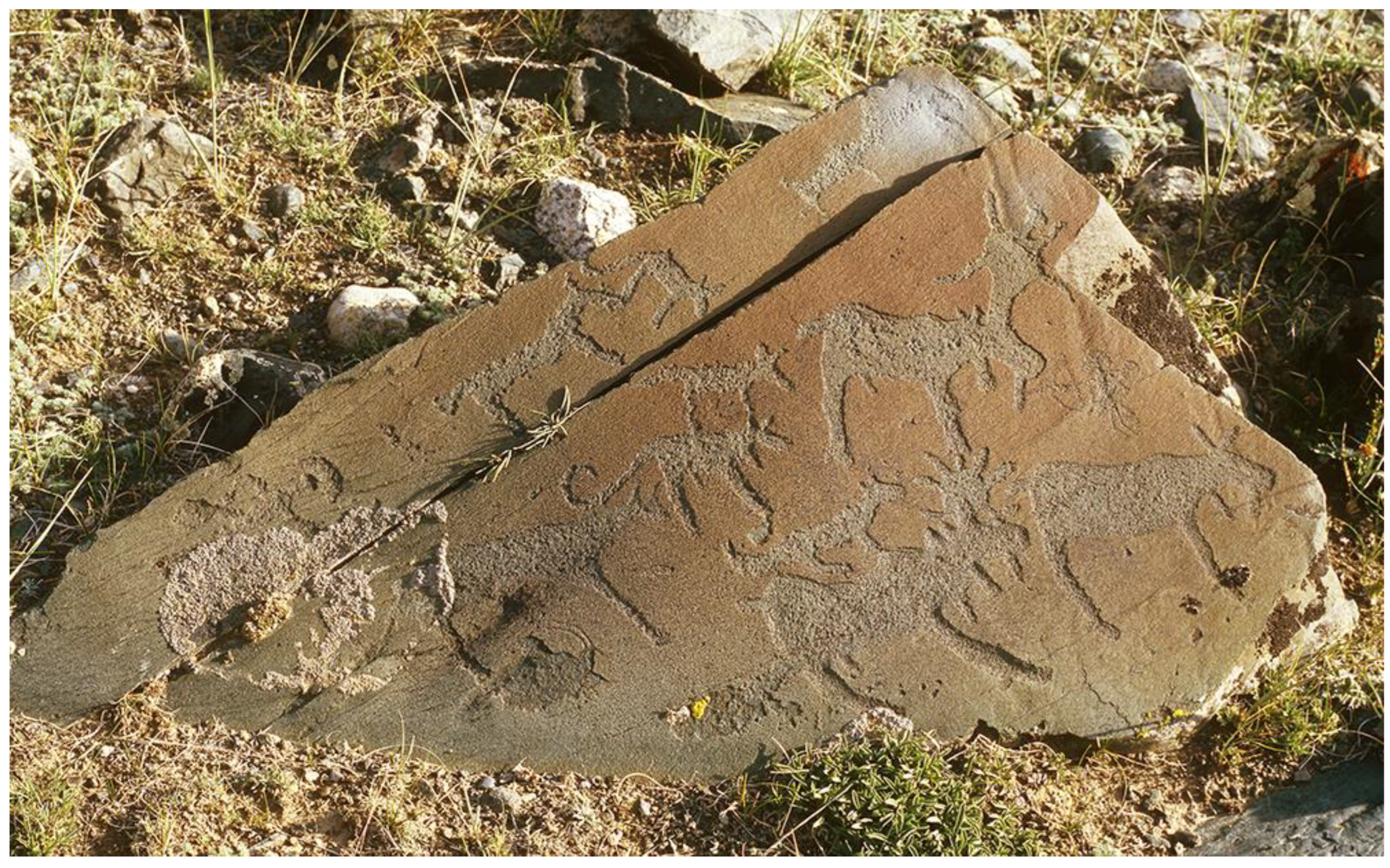

The oldest image of a moose appears on a split boulder located at the southwest end of TS IV (

Figure 5). The boulder is rounded, heavily scraped by glacial action, and much of its surface is spalling, revealing the dull matrix of the stone under the warm brown surface layer. The body of the animal, pecked onto the side of the boulder, is only partially indicated by a roughly pecked contour, but its head and large palmate antler have been fully pecked, again with rough blows. Under the animal’s throat is visible its characteristic hairy bell. The use of a contour line for the animal and the direct (as opposed to indirect) blows of a hammer stone, indicate a very early date for this image. This is also true of the figure of a man visible across the upper split of the stone. His frontal posture and the heavy club in his hand are best compared with the earliest images of hunters in the region, from Aral Tolgoi, a small complex further to the south. These are almost all frontal, all directly pecked, and many are armed with clubs rather than bows and arrows (Tseveendorj, Kubarev, Jacobson 2005). For a number of reasons, the compositions from Aral Tolgoi must be dated to the late Pleistocene or early Holocene, while the boulder from TS IV is certainly later (Jacobson-Tepfer 2019). However, the boulder is found in immediate proximity to a number of images of wild horses, aurochs, a mammoth, and a bear that can be confidently dated to a period earlier than the Bronze Age.

Map. Baga Oigor complex with main rivers and sections. TS refers to sections along the Tsagaan Salaa river; BO refers to sections along the main river, Baga Oigor Gol.

Figure 5.

Split boulder with frontal hunter and upper body of a moose. TS IV.

Figure 5.

Split boulder with frontal hunter and upper body of a moose. TS IV.

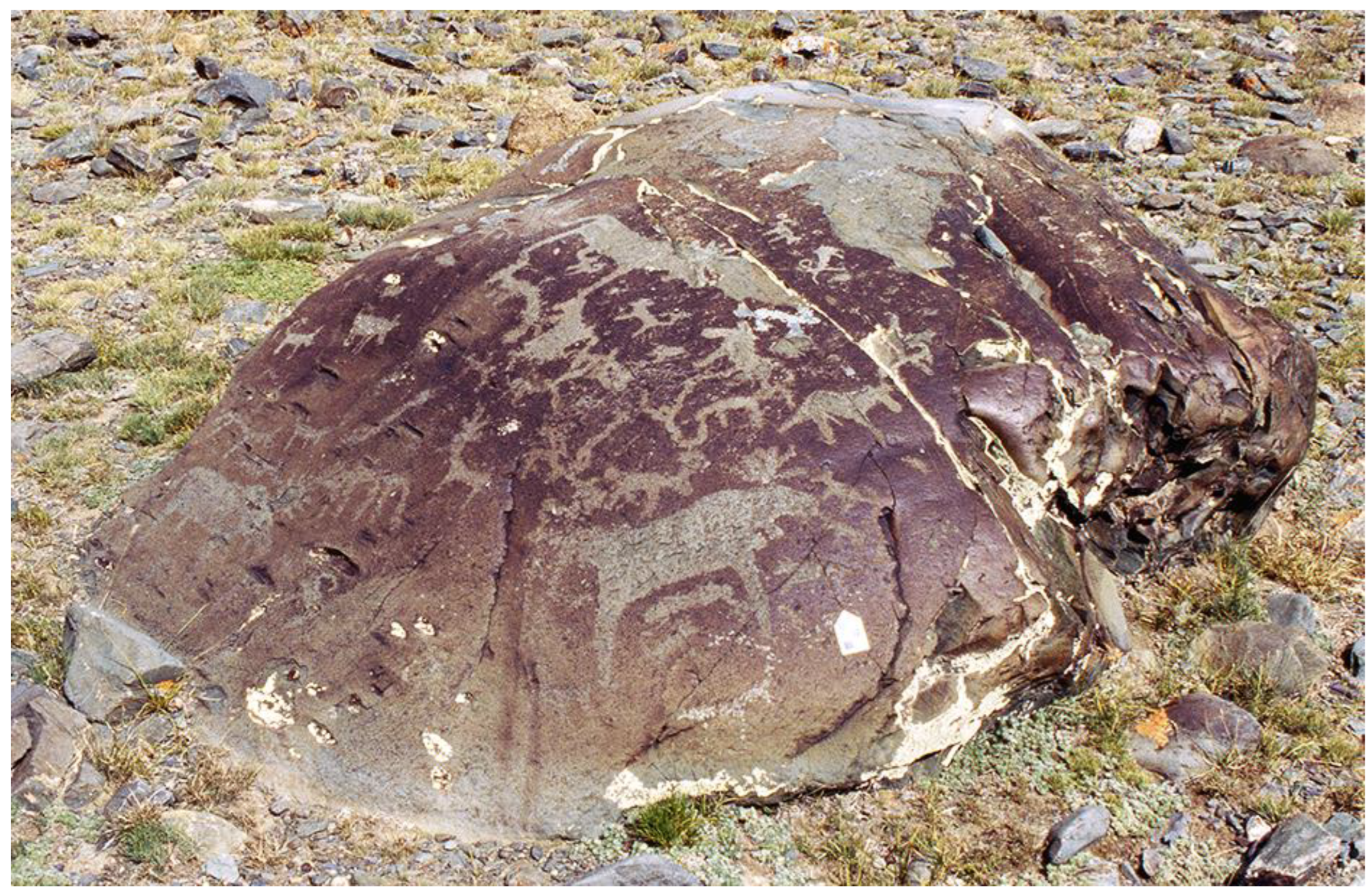

On a boulder further to the east, in BO II, are several images executed at different dates (

Figure 6). On the basis of execution and style, that of a large profile moose was the earliest: its heavy, contoured body was pecked out with rough, direct blows; and the animal demonstrates a degree of static realism that is certainly of a pre-Bronze Age date. The artist has indicated the animal’s bell, its soft dew lip, and its palmate antlers. In this case there are no hunters associated with the bull moose; but on the adjoining plane of the boulder is a scene of a hunt in which two diminutive archers attack another but clumsily detailed bull moose. The body of this animal and its small palmate antlers were executed with indirect blows, as were the two small hunters. The slight build of the hunters, their rounded headdresses, and their composite bows are sure signs of a mid-Bronze Age date. In effect, the two very different panels on this one boulder offer a virtual measure of geological time during which this valley offered habitat for moose.

Figure 6.

Bull moose on the east-facing panel; a second moose and small hunters on the south-facing panel. BO II.

Figure 6.

Bull moose on the east-facing panel; a second moose and small hunters on the south-facing panel. BO II.

On a boulder from BO I are visible three bull moose, several wild horses, and a variety of other animals. All the animals have been directly pecked out in silhouette style, thus indicating a Bronze Age date; but the moose stand stoically still while being attacked by small wolves or dogs. The appearance here of a number of mature bull moose—which would ordinarily not be seen together—raises questions about the artist’s conception: whether he intended to simply duplicate the image of the bull moose or to represent the period of the rut. If that remains uncertain, the very repetition of this animal image, executed with a considerable degree of realism, forces us to recognize that the large moose were familiar to the hunters here, at least within this valley, and that there had to have been the habitat to support them.

Figure 7.

Three bull moose, wild horses, other animals. BO I.

Figure 7.

Three bull moose, wild horses, other animals. BO I.

No less interesting are the images on a massive, table-like boulder that stands on the terrace of the hidden winter dwelling in

Figure 3. This boulder was deeply scraped and polished by glacial action; and to judge from the style and uniform re-patination of all the figures on the upper surface, it must have been decorated within a limited span of time, perhaps that marked by a single family’s use of the dwelling over several years. On the side of the boulder (not visible here) is a clumsy moose; but on the upper surface (

Figure 8), amid a welter of figures including a handsome buck, a wild horse, and many canids, is a fine bull moose with small palmate antlers and a well-defined bell. This animal is in motion, as if to ward off the small canines by which it is surrounded. On this surface are visible two human figures: one is frontal, with arms raised in the position of a birthing woman (Jacobson-Tepfer 2015); the other walks toward the moose, his right arm raised and holding some kind of a hammer-like weapon. The appearance here of a figure with that kind of weapon and the frontal figure indicate a date no later than the mid-Bronze Age.

The greatest concentration of surviving moose images is in the area where TS II and IV converge (

Figure 9), just overlooking the confluence of the stream Tsagaan Salaa and the river, Baga Oigor. The aspect of that region is now completely treeless; but around the confluence and in the adjoining large plain of Baga Oigor, rippled topography and water-worn boulders indicate a time in the past when there was considerable moving water, enough even to create a shallow lake (Jacobson-Tepfer 2020). Just above the present stream bed and within TS II, is a worn boulder deeply embedded in the rocky soil (

Figure 10). This boulder has been decorated with two highly realistic bull moose, one on the upper surface and one attacked by a wolf on the south-facing surface (

Figure 11 and

Figure 12).

Not far above the boulder in

Figure 10, a large winter dwelling is tucked into a terrace between TS II and IV and backs up to a protective, rocky rise (

Figure 13). The photograph of the terrace makes clear the utter treelessness of the topography in the present. In one of several corridors leading back through this rocky rise is a vertical surface on which was executed a hunting scene including a massive moose surrounded by wolves or dogs and followed by a walking hunter. Although his weaponry is not evident, the hunter does have two dogs on long leads (

Figure 14).

Another hunting scene, this one at the base of TS II and just above the stream Tsagaan Salaa, is centered on the powerful image of a bull moose (

Figure 15). Its size in relation to all the other images on the stone suggests that the moose is an animal of mythic significance. It is surrounded by wolves or dogs, while off to the left is a small hunter. He holds what appears to be a bow, and aims at a goat-like animal rather than at the moose. The surface of the stone is extremely worn and its imagery much darkened. That together with the realistic style of the images, the suggestion of a reference to a mythic narrative, and the treatment of the human figure indicates, also, a date solidly in the middle Bronze Age.

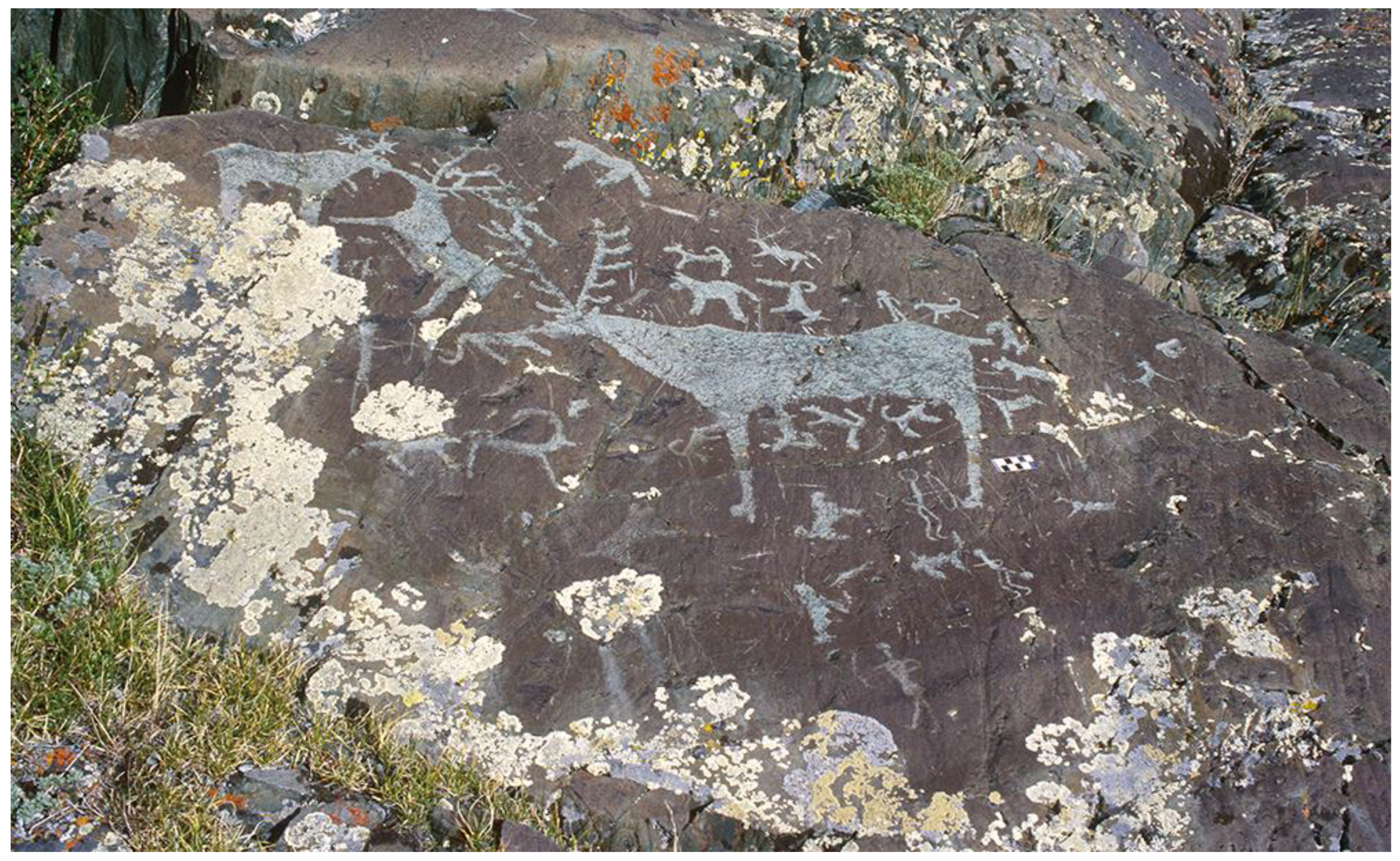

On a high surface at the western edge of TS II is another hunting scene with two large elk, one confronting a powerful moose (

Figure 16). The largest elk is surrounded by canids, a variety of other animals, and at least three small hunters. The size of the elk and moose, the diminutive character of the human figures, and the small frontal figure standing on the hip of the large elk suggest that this scene may also refers to a mythic tale, in which large antlered cervids improbably together center the narrative landscape.

Figure 16.

Mythic scene: moose and elk, hunters and dogs. TS II.

Figure 16.

Mythic scene: moose and elk, hunters and dogs. TS II.

TS IV is a large section and one of the most richly decorated within the whole Baga Oigor complex. On its west end it includes a deep and protected terrace in which are found several surfaces covered with imagery. One large outcrop on the west side of the terrace includes the scene of a complex hunt involving wild horses (upper right), argali (left), and two antlered moose, one massive and the other quite small (

Figure 17 and

Figure 18). These images are much more awkward in shape and execution than those in the previously mentioned hunting scenes: they seem to stand passively, as if tolerating the attack of dogs and human hunters. The latter are variously defined, including one large hunter on the far fight. Nonetheless, their dress and weaponry help to establish a date within the latter Bronze Age. All the figures carry composite bows. At least three of the figures carry a large round object from their waists; these were probably throwing stones (Jacobson-Tepfer 2019, IV.28). Elsewhere in this complex and in that of Tsagaan Gol, these objects are associated with a number of elements that indicate a late Bronze Age date: a time when people were beginning to handle horses but not yet a period of mounted nomadism. At least three of the figures in this large scene from TS IV also wear what look like horned headdresses but were almost certainly the skins of animal heads worn by hunters (even today) as a kind of disguise (Jacobson-Tepfer 2019, IX.11–IX.15). The images of wild horses, as opposed to domesticated horses, reaffirm a date no later than the latter Bronze Age.

One last image from the Baga Oigor complex must be mentioned; even though it is more modest than the others it may be more culturally significant. This is a small scene on a hidden vertical face in BO II (

Figure 19). The composition includes a yak loaded with a large basket in which are visible two small figures. Around this group is another, smaller yak, a goat, and two indeterminate animals as well as a bull moose. This last stands quietly behind the loaded yak as if it were a benign observer of newcomers passing through the landscape. The moose has large antlers, a soft and swollen nose and what appears to be a messy bell. This figure has been scraped and scratched after its original execution, so the pecked surface has a smoothed whitish-brown, lacquer-like appearance and deep gouges over its legs. Its long tail was added well after the execution of the animal, probably by the same person who gouged out its front leg.

For all its modesty, this scene offers significant clues regarding its temporal and cultural context. The coloration of the images, seemingly in transition between the original white of the crushed rock and the brown of re-patination, indicates that the scene was executed in the latter half of the second millennium BCE. The modesty and directness of the images, also, are typical of many petroglyphic compositions in that period. Most important is the image of the loaded yak. These patient, heavily burdened animals, often shown carrying both the children and the gear of the household, attest to a time when hunters and herders began to move into the higher mountains with their families in search of good summer pasture. There are many such images in the Baga Oigor and Tsagaan Gol complexes, all reflecting a new cultural phase in the latter Bronze Age. In none of those scenes, however, are there ever any figures on horseback, although there are a few in which horses are included as a part of the animal caravan (Jacobson-Tepfer 2019, X.3). In this case, the loaded yak signals a time when the valley must have become sufficiently dry to allow the passage of such heavy animals. The moose, on the other hand, reflects an earlier, more riparian environment. In other words, this little composition, balanced between moose and loaded yak, suggests a world in decisive environmental and cultural flux.

The appearance of a moose in the BO II panel adds a distinctive narrative impulse as well as a firmer sense of the larger context in which this family caravan was occurring. The moose infers the wild world through which the caravan was moving, but a world far different from the rocky, dry landscape of today’s valley. It evokes a forested, marshy environment in the Baga Oigor valley. This scene and all the others featuring individual moose, or the hunting of moose, should correct our understanding of the world here in the Bronze Age before the advent of horse riding; and this, in turn, should reshape our understanding of that cultural period transitional between the environment of the middle Holocene and the early late Holocene.

There are no moose images in Baga Oigor later than those discussed above; and there are very few within the petroglyphic record of the Tsagaan Gol complex. Two may be mentioned here. One is a small scene on a lacquered brown surface involving two scenes of predation (

Figure 20). On the left is a large wolf leaping at the hindquarters of an elegant stag. On the right, and dominating the surface, is a scene of another wolf attacking the leg of a large animal with the palmate antler and shoulder hump of a moose. The two pairs of animals were clearly executed by different hands and at various times; and the second “moose” is unclearly even that, identifiable as such only by the animal’s antlers.

Within the Tsagaan Gol valley, there is one other scene that makes absolutely clear the nature of the large animals and their probable presence at some time in the valley. We found this composition on a fragmentary boulder (

Figure 21) at the edge of the vast, rocky moraine filling the middle section of the Tsagaan Gol complex. The scene is dominated by three large moose, two of which have strange palmate antlers, but all three of which inexplicably have two or more bells hanging from their necks. Despite these odd elements, these animals are easily recognizable as moose, but they are static despite being followed by a group of wolves. At either end of the remaining surface are two small hunters, one (extreme left) partially hidden by lichen and the other (right) almost lost between two of the larger animals. This little figure (

Figure 22) has the slender body type of many other figures from the mid-Bronze Age. He also carries the long quiver and composite bow indicative of that approximate date; and from the waists of both figures hang the wand-like

daluur used for distracting prey animals. In addition, both figures wear a form of rounded fur headdress that we find in many other petroglyphs indicative of the full Bronze Age, well before the advent of riding.

This small scene is puzzling in many respects. It is the only clear image of a moose hunt that we have located and recorded within the huge Tsagaan Gol complex. But it is also in such an anomalous place, on the edge of the rocky moraine, close by a small area that is still marshy with the inflow of a small stream from the slopes above (

Figure 23). Despite the forbidding aspect of the moraine today, the marshy area infers an earlier, wetter environment; and the images of small figures hunting moose also imply that at some point in the Bronze Age, this valley was still wet enough and forested enough to support moose.

The image of Alces alces in the Baga Oigor and Tsagaan Gol valleys is unusual within the rock art record of western Mongolia and, indeed, within that of the Altai region in general. It may be considered together with that of another animal requiring a somewhat similar environment, the brown bear (Ursus arctos collaris). This animal occurs irregularly in rock art of these northern complexes. Together these animals, moose and bear, implicate a more heavily forested and significantly wetter habitat. In fact, the moose images here in Bayan Ölgiy suggest that this may once have been the southern edge of the Siberian taiga habitat, where these animals are still found in the more heavily forested zones. The ancient imagery of moose from cliffs over the Tom’ (Okladnikov and Martynov, 1972), the Angara (Olkadnikov 1966), and the Lena (Mel’nikova et al. 2011) rivers of Siberia indicates the extent to which that animal was previously hunted and even revered in prehistory (Jacobson-Tepfer 2015, pp. 28–41). That status does not seem to have been the case in northwestern Mongolia. To judge from the compositions in which it appears, Alces alces seems to have been understood primarily as a prey animal, although its occasional appearance in compositions suggesting mythic narratives may belie that statement. Most important, however, is the degree to which the images of moose should force us to rethink the environment of northwestern Mongolia, to recalibrate, as it were, the lives of ancient hunters and herders in that region and in that geological period in the third to early second millennia BCE when they were well represented on the Baga Oigor stage.

Acknowledgments

The author is indebted to Gary Tepfer for all the photographs published in this paper. The Map was made by the author and James Meacham with the collaboration of the InfoGraphics Lab at the University of Oregon. The Chart is adapted from that published by Jacobson-Tepfer et al. 2010.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- (An et al. 2008) An, Cheng-Bang, Fa-Hu Chen, and Loukas Barton. 2008. Holocene environmental changes in Mongolia: A review. Global and Planetary Change 63: 283–289. [CrossRef]

- (Gunin et al. 1999) Gunin, P. D., E. A. Vostokova, N. I. Dorofeyuk, P. E. Tarasov, and C. C. Black. 1999. Vegetation Dynamics of Mongolia. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- (Rudaya et al. 2009) Rudaya, Natalia, Pavel Tarasov, Nadezhda Dorofeyuk, Nadia Solovieva, Ivan Kalugin, Andrei Andreev, Andrei Daryin, Bernhard Diekmann, Frank Riedel, Narantsetseg Tserendash, and Mayke Wagner. 2009. Holocene environments and climate in the Mongolian Altai reconstructed from the Hoton-Nur pollen and diatom records: a step towards better understanding climate dynamics in Central Asia. Quaternary Science Reviews 28: 540–554. [CrossRef]

- (Jacobson-Tepfer 2015) Jacobson-Tepfer, E. 2015. The Hunter, the Stag, and the Mother of Animals. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- (Jacobson-Tepfer 2019) Jacobson-Tepfer, E. 2019. The Life of Two Valleys in the Bronze Age. Eugene, Oregon: Luminaire Press.

- (Jacobson-Tepfer 2020). Jacobson-Tepfer, E. 2020. The Anatomy of Deep Time. Cambridge Elements in the Environmental Humanities. Cambridge University Press.

- (Jacobson-Tepfer et al. 2010) Jacobson-Tepfer, E., James Meacham, Gary Tepfer. 2010. Archaeology and Landscape in the Mongolian Altai: an Atlas. Redlands, CA: ESRI Press.

- (Mel’nikova et al. 2011) Mel’nikova, L. V., V, S. Nikolayev, and N. I. Dem’yanovich. 2011. Shishkinskaya pisanitsa. Vol. I. Irkutsk: Institute of the Earth’s Crust. Russian Academy of Sciences, Siberian Section.

- (Okladnikov 1966) Okladnikov, A. P. 1966. Petroglify Angary. Moscow-Leningrad: Nauka.

- Okladnikov and Martynov 1972) Okladnikov, A. P. and A. I. Martynov. 1972. Sokrovishcha tomskikh pisanits. Moscow: Iskusstvo.

- (Tsevendorj et al. 2005) Tseveendorj, D., V. D. Kubarev, and E. Yakobson (Jacobson). 2005. Aral tolgoin khadny zurag. Ulaanbaatar: Institute of Archaeology, Mongolian Academy of Sciences.

Figure 1.

View west over the confluence of Baga Oigor and Tsagaan Salaa and up the Tsagaan Salaa valley.

Figure 1.

View west over the confluence of Baga Oigor and Tsagaan Salaa and up the Tsagaan Salaa valley.

Figure 2.

View east down Baga Oigor valley, from the Great Circle. TS IV.

Figure 2.

View east down Baga Oigor valley, from the Great Circle. TS IV.

Figure 3.

Hidden winter dwelling. BO IV. View to the west.

Figure 3.

Hidden winter dwelling. BO IV. View to the west.

Figure 4.

View across the mouth of Tsagaan Salaa northwest to TS II (left of center) and TS IV (right of center). The view here encompasses some of the finest panels with moose imagery in the Baga Oigor complex.

Figure 4.

View across the mouth of Tsagaan Salaa northwest to TS II (left of center) and TS IV (right of center). The view here encompasses some of the finest panels with moose imagery in the Baga Oigor complex.

Figure 8.

Section of a large surface of a table-like boulder: elk, moose, two frontal figures, inter alia. BO IV.

Figure 8.

Section of a large surface of a table-like boulder: elk, moose, two frontal figures, inter alia. BO IV.

Figure 9.

View from TS III east down the Baga Oigor valley with the juncture between TS II and IV in the center midground and the river course of Baga Oigor in the upper right. The circular dips in the near landscape were washed out by flooding water in a distant past. In the upper right can be seen the plain that at one time was part of a lake. .

Figure 9.

View from TS III east down the Baga Oigor valley with the juncture between TS II and IV in the center midground and the river course of Baga Oigor in the upper right. The circular dips in the near landscape were washed out by flooding water in a distant past. In the upper right can be seen the plain that at one time was part of a lake. .

Figure 10.

Boulder with two moose images. East end, TS II.

Figure 10.

Boulder with two moose images. East end, TS II.

Figure 11.

Bull moose on the upper surface of the boulder seen in

Figure 10.

Figure 11.

Bull moose on the upper surface of the boulder seen in

Figure 10.

Figure 12.

Bull moose attacked by a wolf, on the sloping surface of the boulder in

Figure 10. TS II.

Figure 12.

Bull moose attacked by a wolf, on the sloping surface of the boulder in

Figure 10. TS II.

Figure 13.

View of large winter dwelling between TS II and TS IV.

Figure 13.

View of large winter dwelling between TS II and TS IV.

Figure 14.

Moose hunt with leashed dogs. On the left is the hunter with his dogs, on the right is a large moose within a herd of horses. TS II.

Figure 14.

Moose hunt with leashed dogs. On the left is the hunter with his dogs, on the right is a large moose within a herd of horses. TS II.

Figure 15.

Moose surrounded by wolves and a small hunter in the lower left. TS II.

Figure 15.

Moose surrounded by wolves and a small hunter in the lower left. TS II.

Figure 17.

Moose hunt, with wild horses attacked by dogs or wolves. TS IV.

Figure 17.

Moose hunt, with wild horses attacked by dogs or wolves. TS IV.

Figure 18.

Detail of

Figure 17: two bull moose, five hunters, several dogs or wolves.

Figure 18.

Detail of

Figure 17: two bull moose, five hunters, several dogs or wolves.

Figure 19.

Loaded yak, moose, and other images. BO II.

Figure 19.

Loaded yak, moose, and other images. BO II.

Figure 20.

Double predation: wolf on elk, wolf on moose. TG_04167.

Figure 20.

Double predation: wolf on elk, wolf on moose. TG_04167.

Figure 21.

Two bull moose, one cow moose, dogs and two hunters. TG_H1.

Figure 21.

Two bull moose, one cow moose, dogs and two hunters. TG_H1.

Figure 22.

Small hunter, detail from the far-right side of the moose hunt,

Figure 21.

Figure 22.

Small hunter, detail from the far-right side of the moose hunt,

Figure 21.

Figure 23.

View down to a marshy section of the Tsagaan Gol valley, where was found the panel with moose and hunters (

Figure 21). The large moraine and the main river are visible across the midground of the image.

Figure 23.

View down to a marshy section of the Tsagaan Gol valley, where was found the panel with moose and hunters (

Figure 21). The large moraine and the main river are visible across the midground of the image.

Table 1.

Proposed Concordance of Paleoenvironment, Fauna, and Culture.

Table 1.

Proposed Concordance of Paleoenvironment, Fauna, and Culture.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).