Submitted:

19 June 2024

Posted:

19 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

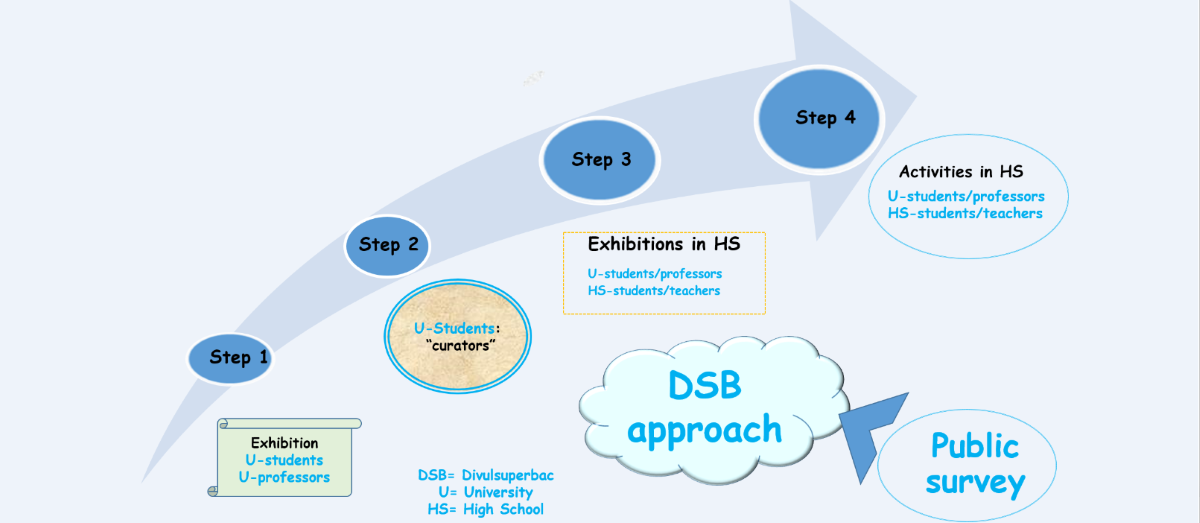

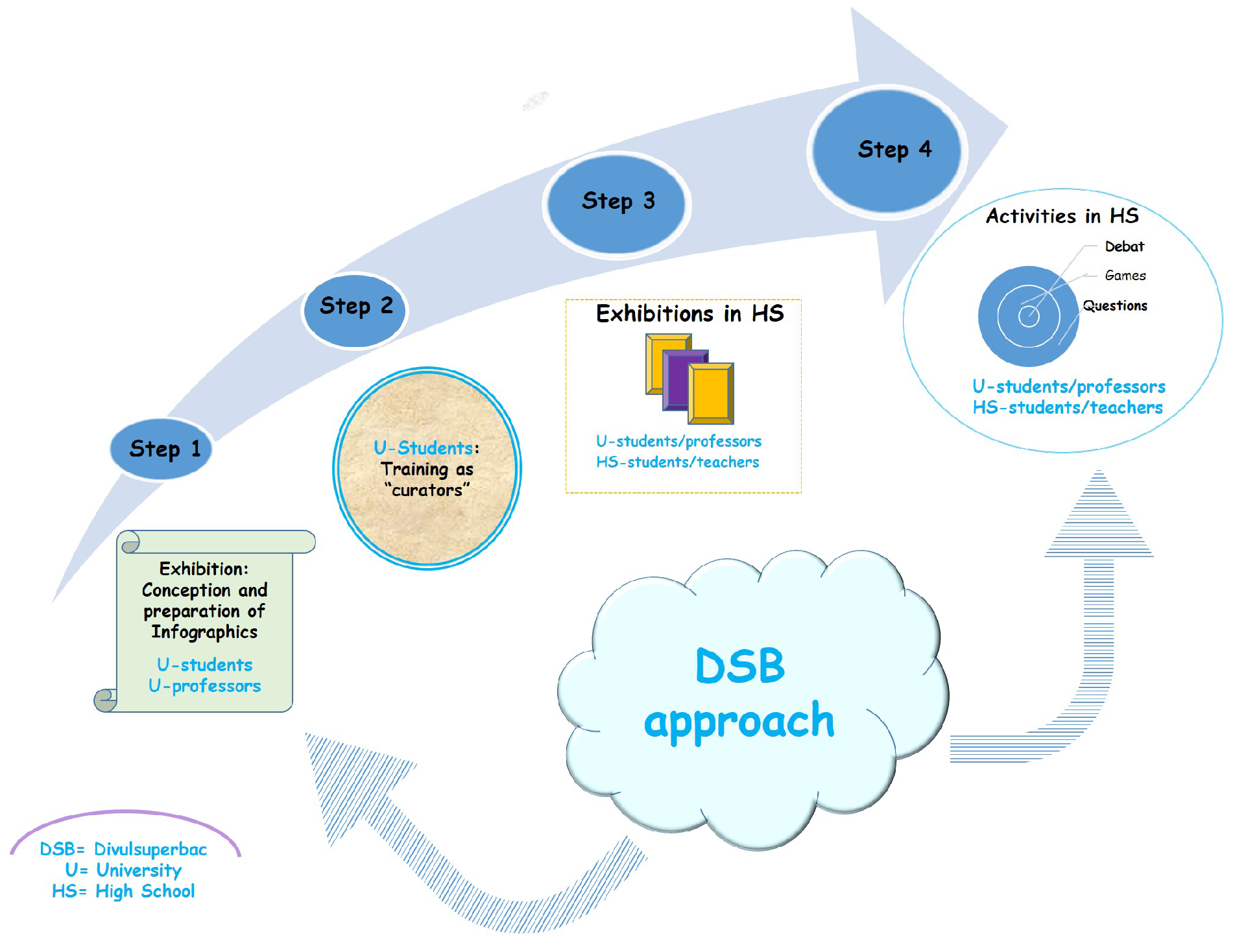

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Exhibition: Conception and Preparation of Infographics

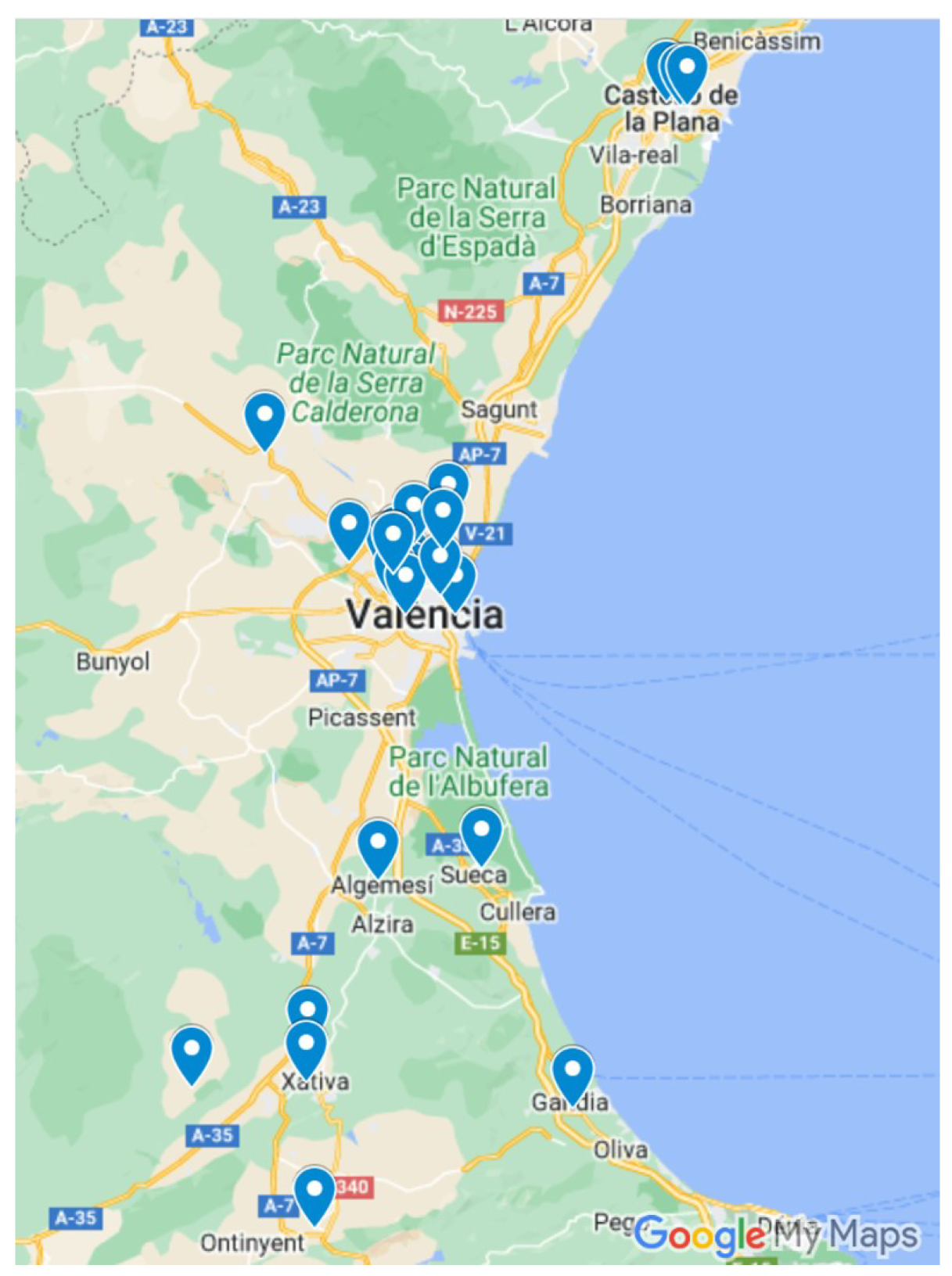

2.2. Participants and Partner High Schools

2.3. Activities in High Schools (HS)

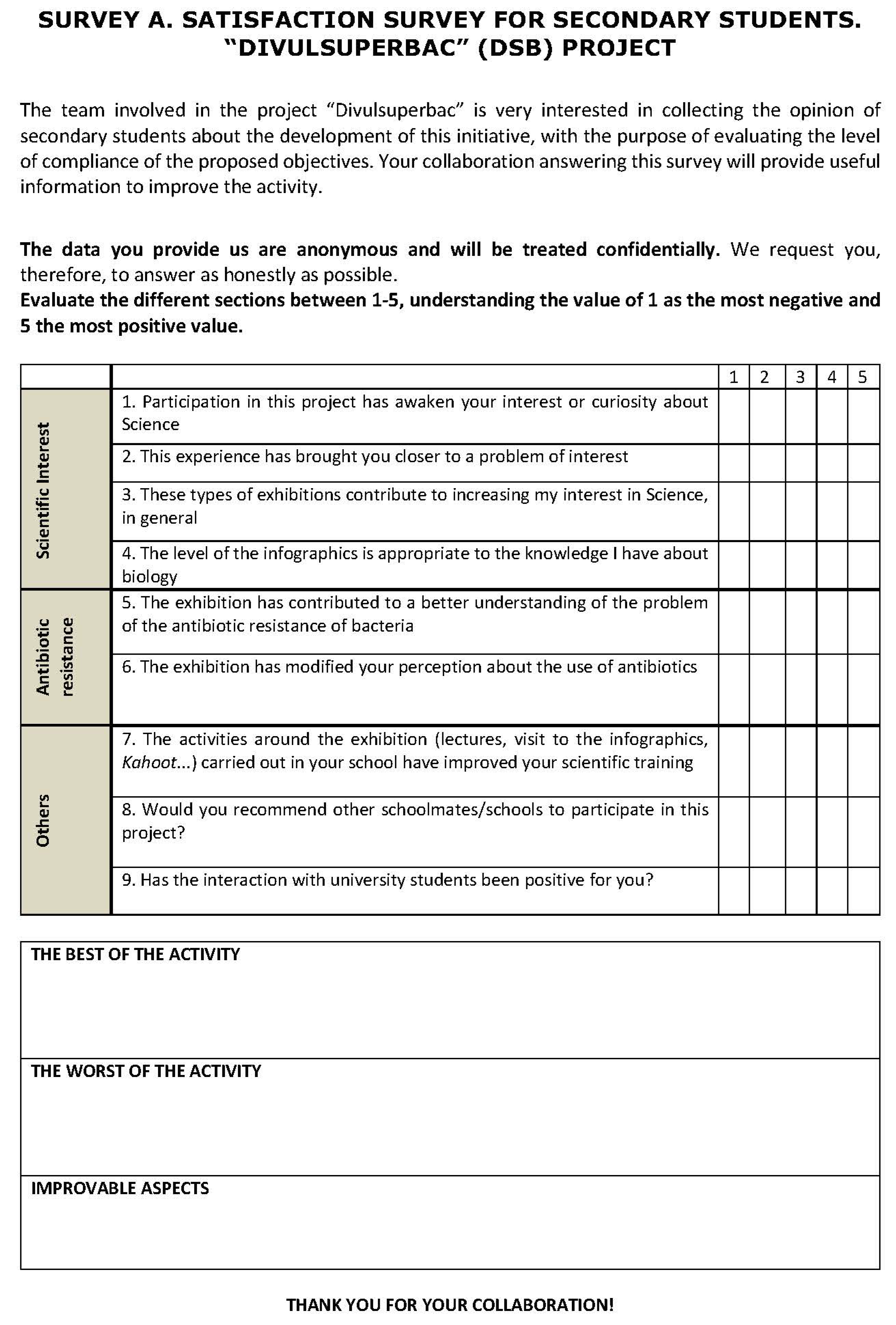

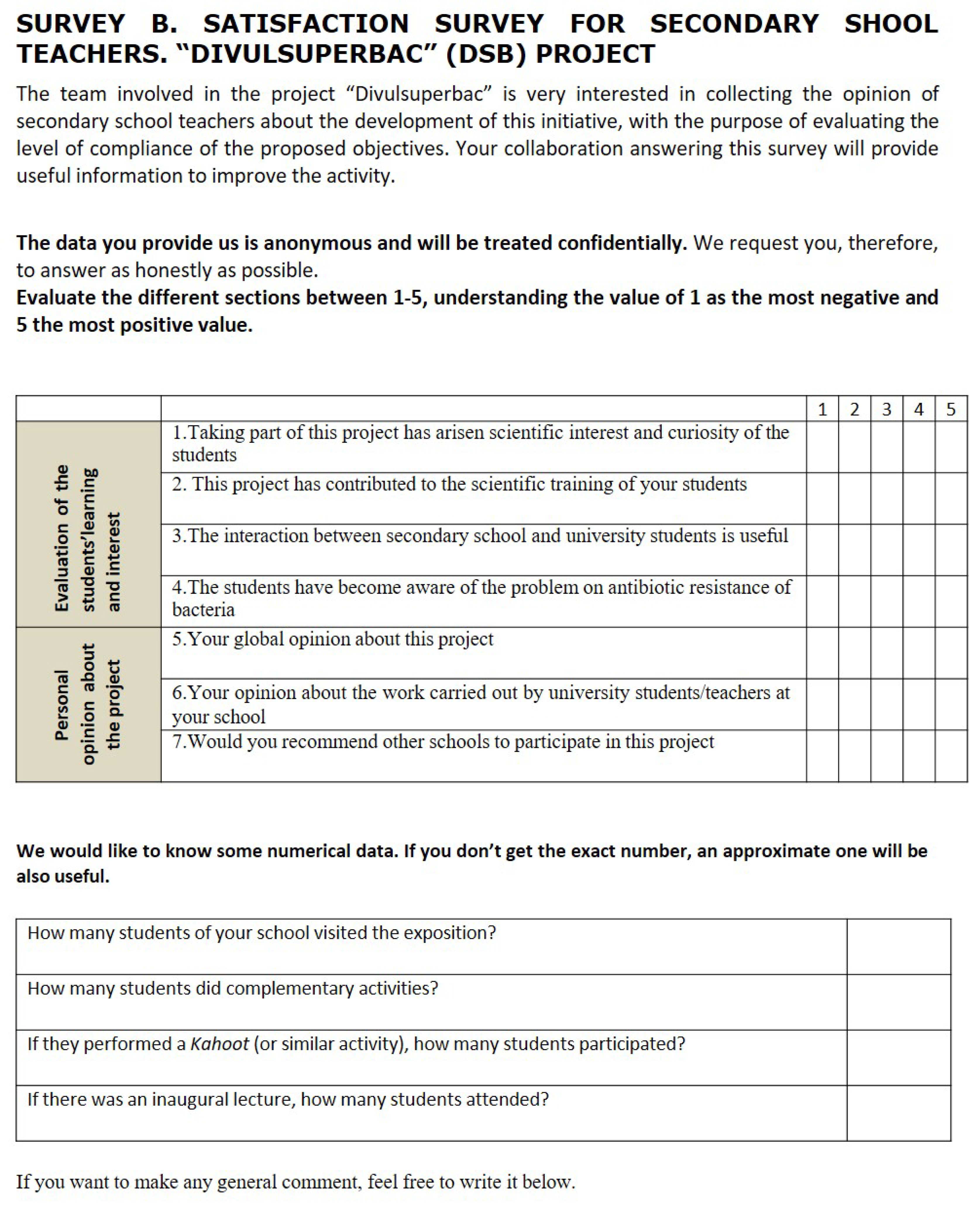

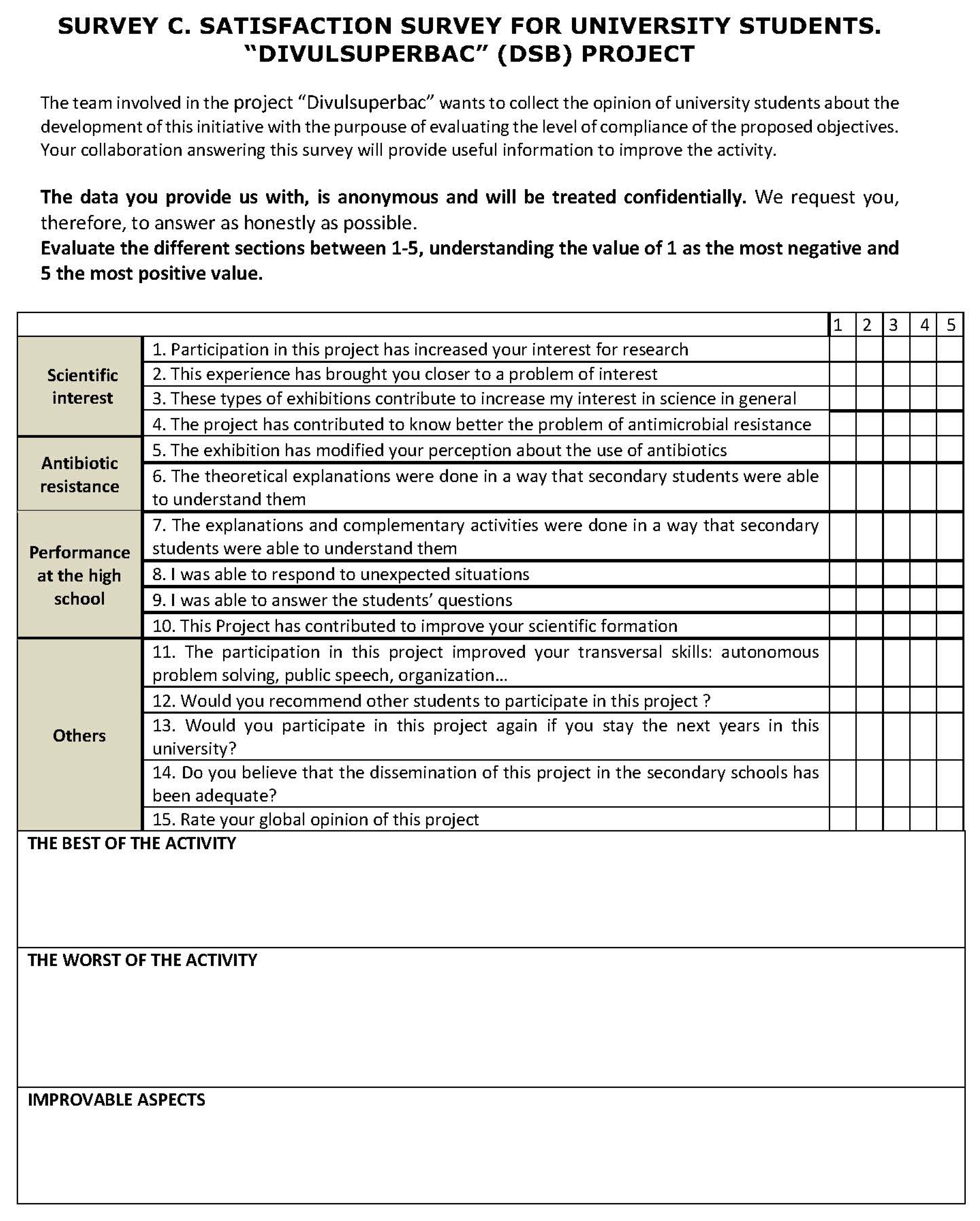

2.4. Design of Surveys and Evaluation Procedure

3. Results

3.1. Dynamics of the Activities

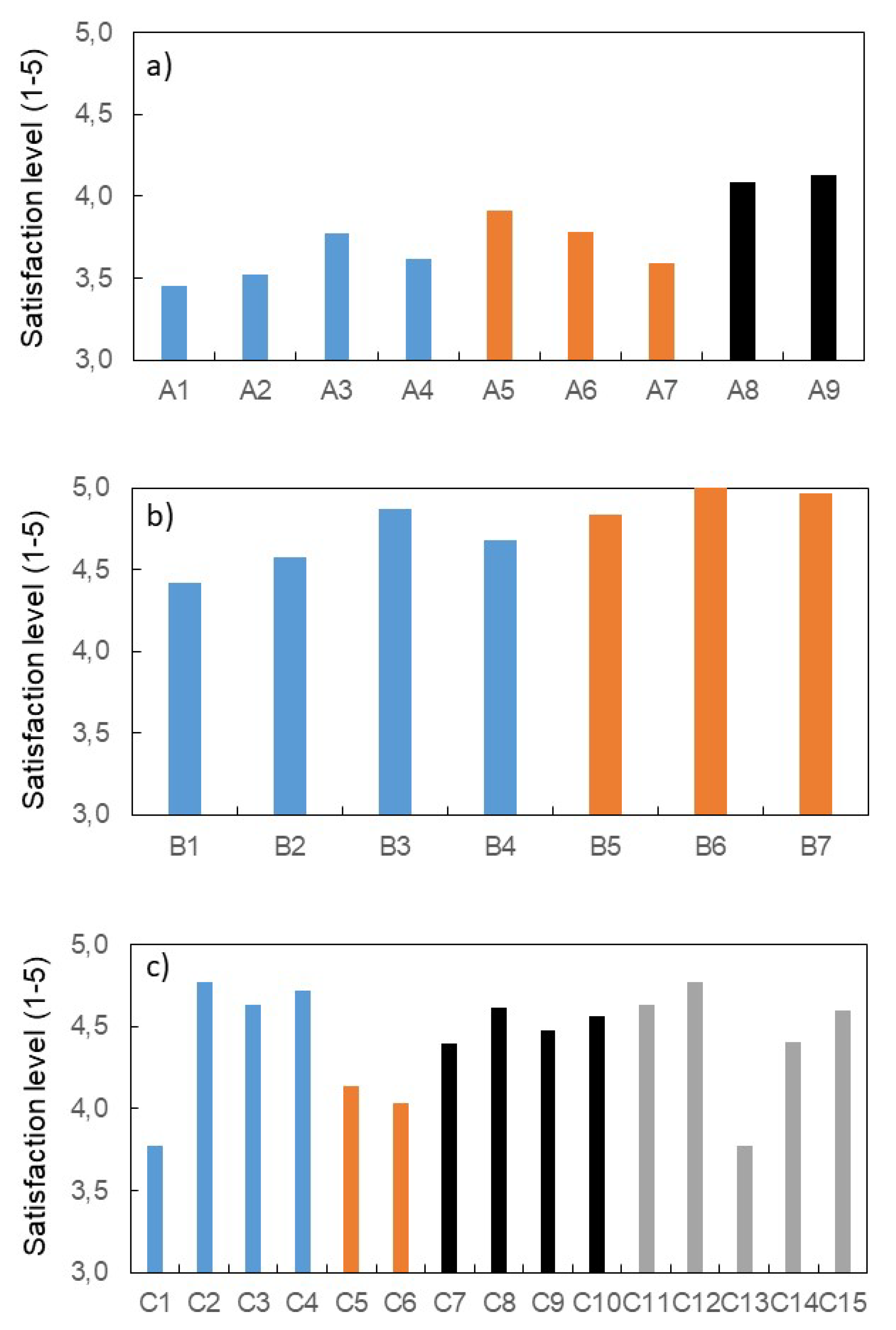

3.2. Evaluation of the Activities

3.2.1. Academic Survey

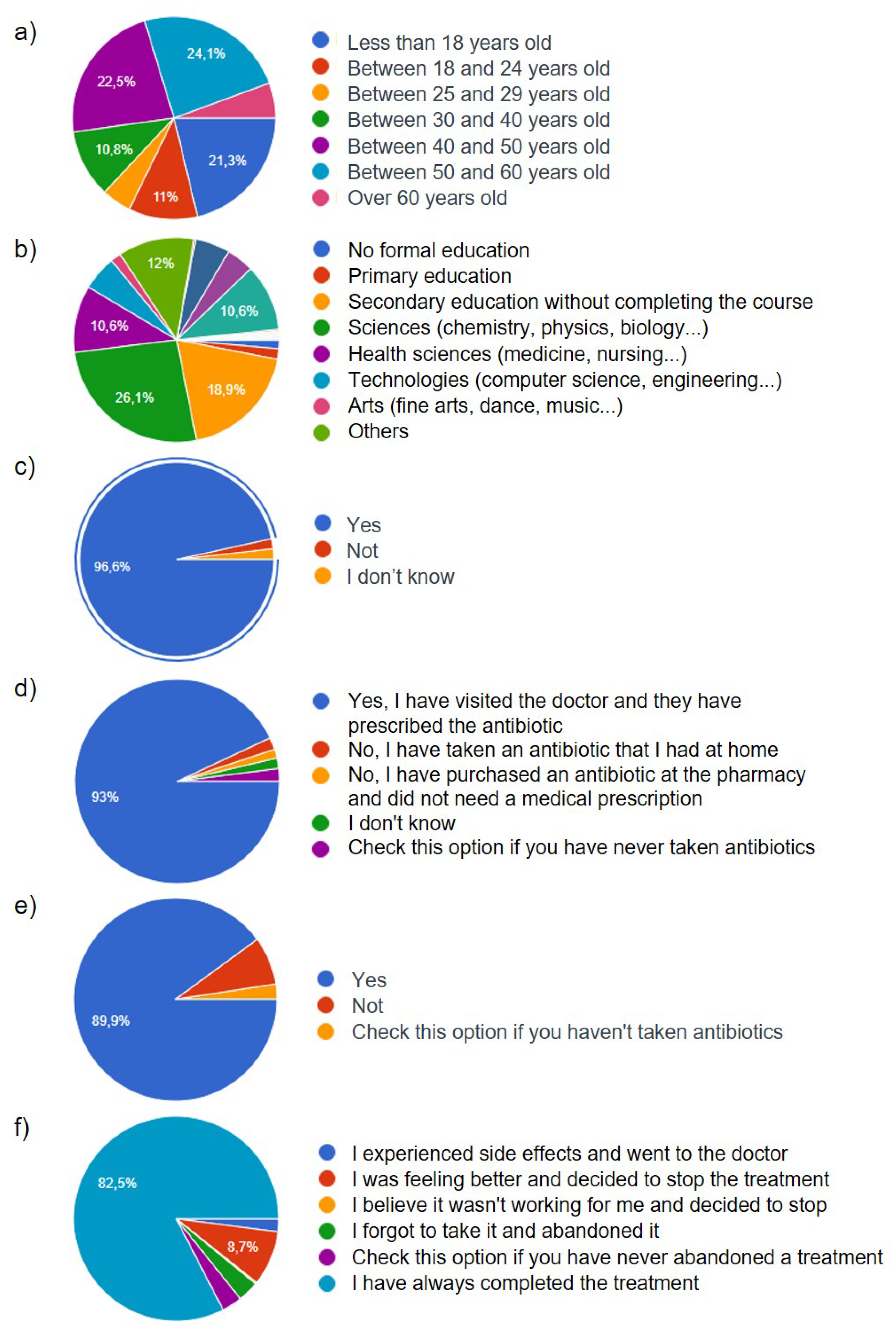

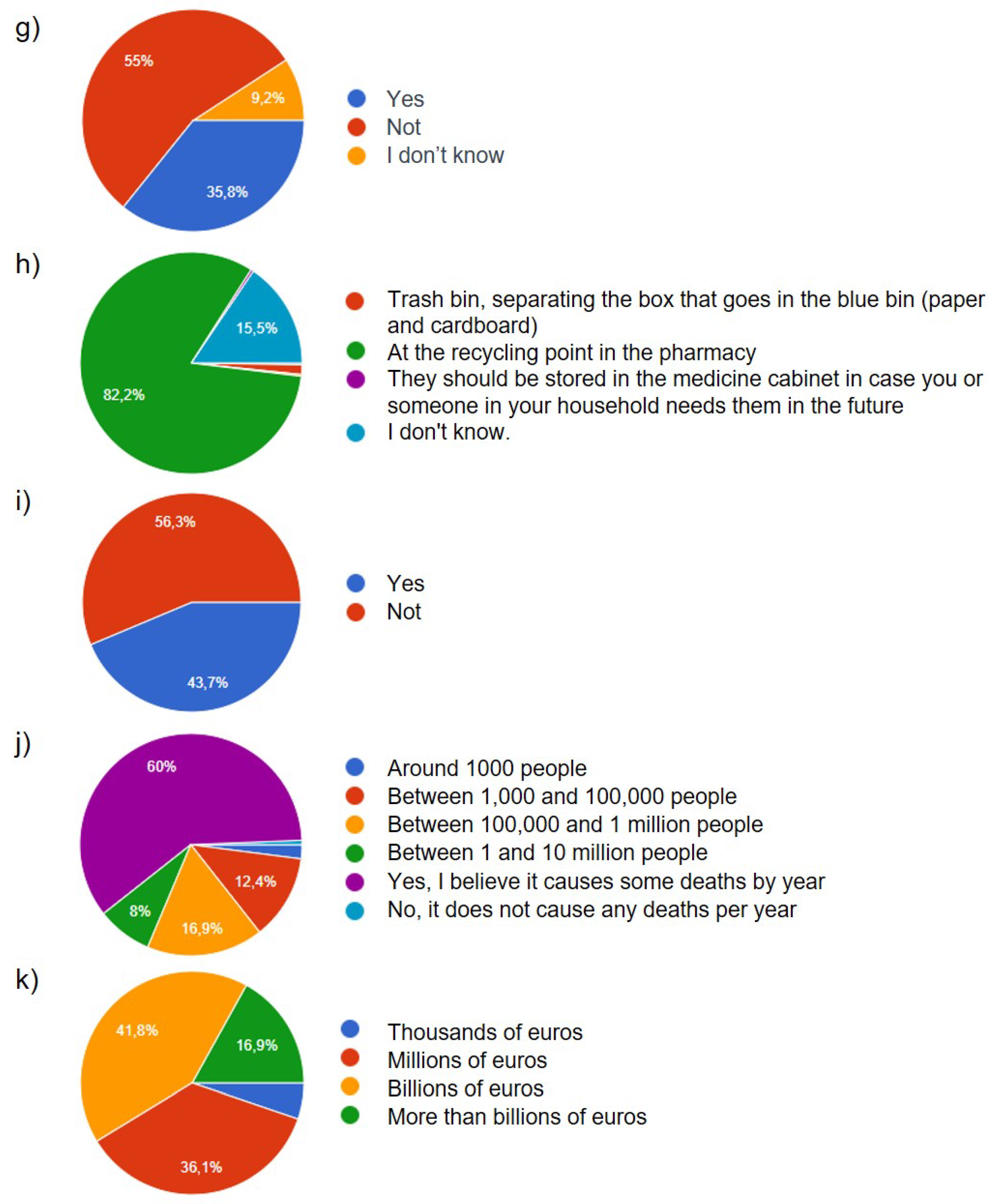

3.2.2. Public Survey

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMR | Antimicrobial resistance |

| DSB | Divulsuperbac |

| HS | high school |

Appendix A

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The threat of antimicrobial resistance: Time for action. CDC Drug Resistance Report 2013.

- O’Neill, J. Antimicrobial resistance: Tackling a crisis for the health and wealth of nations. The Review on Antimicrobial Resistance 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global action plan on antimicrobial resistance. World Health Organization 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Laxminarayan, R.; Duse, A.; Wattal, C.; Zaidi, A.K.M.; Wertheim, H.F.L.; Sumpradit, N.; Vlieghe, E.; Hara, G.L.; Gould, I.M.; Goossens, H.; others. Antibiotic effectiveness: balancing conservation against innovation. Science 2014, 345, 1299–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prüss-Ustün, A.; Bartram, J.; Clasen, T.; Colford Jr, J.M.; Cumming, O.; Curtis, V.; Bonjour, S.; Dangour, A.D.; De France, J.; Fewtrell, L. ; others. Safer water, better health: Costs, benefits and sustainability of interventions to protect and promote health. World Health Organization 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Laxminarayan, R.; Matsoso, P.; Pant, S.; Brower, C.; Røttingen, J.A.; Klugman, K.; Davies, S. Economic costs of antibiotic resistance: a systematic review. The Lancet infectious diseases 2016, 16, e270–e278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, J. The economic burden of antimicrobial resistance. The Review on Antimicrobial Resistance 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laxminarayan, R.; Duse, A.; Wattal, C.; Zaidi, A.K.; Wertheim, H.F.; Sumpradit, N.; Vlieghe, E.; Hara, G.L.; Gould, I.M.; Goossens, H.; others. Access to effective antimicrobials: a worldwide challenge. The Lancet 2016, 387, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ventola, C.L. The antibiotic resistance crisis: part 1: causes and threats. Pharmacy and Therapeutics 2015, 40, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Collignon, P. The importance of a One Health approach to preventing the development and spread of antibiotic resistance. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2013, 366, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Harbarth, S.; Theuretzbacher, U.; Hackett, J.; DRIVE-AB consortium. Antibiotic research and development: business as usual? J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2015, 70, 1604–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puig, J. Aprendizaje-Servicio: Educación para la Ciudadanía; Ed. Octaedro: Barcelona, Spain, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Maicas, S.; Fouz, B.; Figas-Segura, A.; Zueco, J.; Rico, H.; Navarro, A.; Carbó, E.; Segura-García, J.; Biosca, E.G. Implementation of Antibiotic Discovery by Student Crowdsourcing in the Valencian Community Through a Service Learning Strategy. Frontiers in Microbiology 2020, 11, 564030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piddock, L.J. The crisis of no new antibiotics-what is the way forward? Lancet Infect. Dis. 2012, 12, 249–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cairo, A. The Functional Art: An Introduction to Information Graphics and Visualization; New Riders: Berkeley, CA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, R.L. Information Graphics: A Comprehensive Illustrated Reference; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kirk, A. Data Visualisation: A Handbook for Data Driven Design; SAGE Publications Ltd: Thousand Oaks, CA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Likert, R. A technique for the measurement of attitudes. Arch. Psychol. 1932, 140, 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Valderrama, M.J.; González-Zorn, B.; de Pablo, P.C.; Díez-Orejas, R.; Fernández-Acero, T.; Gil-Serna, J.; others. Educating in antimicrobial resistance awareness: adaptation of the Small World Initiative program to service-learning. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2018, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Google Forms. https://docs.google.com/forms/d/19NQ0Lq9B1h6UA2BR3aZLyhklaNvUiNtzN_ULCk9eWn4/edit?ts=6061ab70. Accessed: May 25, 2023.

- Archer, L.; DeWitt, J.; Osborne, J.; Dillon, J.; Willis, B.; Wong, B. Not girly, not sexy, not glamorous: Primary school girls’ and parents’ constructions of science aspirations. Pedagogies: An International Journal 2012, 7, 261–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, F.S.; diSessa, A.A.; Sherin, B.L. An evolving framework for describing student engagement in classroom activities. The Journal of Mathematical Behavior 2012, 31, 270–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- William, L. Romine, L.H.B.; Folk, W.R. Exploring Secondary Students’ Knowledge and Misconceptions about Influenza: Development, validation, and implementation of a multiple-choice influenza knowledge scale. International Journal of Science Education 2013, 35, 1874–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AEMPS. Plan nacional frente a la resistencia a los antibióticos 2022-2024, 2022. https://resistenciaantibioticos.es/es/publicaciones/plan-nacional-frente-la-resistencia-los-antibioticos-pran-2022-2024 [Accessed: (06/06/2024].

- Byrne, J. Models of Micro-Organisms: Children’s knowledge and understanding of micro-organisms from 7 to 14 years old. International Journal of Science Education 2011, 33, 1927–1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnusson, U.; Moodley, A.; Osbjer, K. Antimicrobial resistance at the livestock-human interface: implications for Veterinary Services. Rev Sci Tech 2021, 40, 511–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ardakani, Z.; Canali, M.; Aragrande, M.; Tomassone, L.; Simoes, M.; Balzani, A.; Beber, C.L. Evaluating the contribution of antimicrobial use in farmed animals to global antimicrobial resistance in humans. One Health 2023, 17, 100647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shallcross, L.J.; Davies, S.D. Antibiotic overuse: a key driver of antimicrobial resistance. Br J Gen Pract 2014, 64, 604–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cusimano, M.; Schillaci, D. It is Time for Action in the Struggle against Antibiotic-Resistance, Let’s Start Reducing or Replacing Antibiotics in Agriculture. Journal of Microbial & Biochemical Technology 2016, 08. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Code | Title |

|---|---|

| 01. | The threat of multi-resistant bacteria to antibiotics |

| 02. | How much do you know about antibiotic resistance? |

| 03. | How did we get here? |

| 04. | ESKAPE |

| 05. | One health |

| 06. | Rebellion in the hospital! |

| 07. | Antibiotics: from the farm to the plate |

| 08. | Problems of antibiotics in agriculture |

| 09. | Intestinal dysbiosis: a serious unknown problem |

| 10. | Microbial resistance in the main sexually transmitted diseases |

| 11. | It will take your breath away! Tuberculosis |

| 12. | Alternatives to antibiotics |

| 13. | Economic impact of antimicrobial resistance |

| 14. | And you, what can you do against microbial resistance? |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).