1. Introduction

Patients with severe swallowing difficulties usually use compensatory feeding method such as nasogastric tube (NGT) feeding or parenteral nutrition.[

1,

2,

3] NGT feeding may be an appropriate alternative method to enteral feeding. However, some patients are fed using an NGT for relatively long periods, which may have negative impact on their swallowing function.[

4] Prolonged dysphagia is strongly associated with poor functional outcomes after brain injury.[

5,

6]

Long-term NGT placement can also cause complications such as gastroesophageal reflux or aspiration pneumonia, nasal wing lesions, and chronic sinusitis.[

7] Although many studies and guidelines recommend percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube insertion in patients with prolonged dysphagia of more than 4-6 weeks[

7,

8,

9], the appropriate patients and timing for this intervention are controversial. Furthermore, there are many patients with prolonged NGT insertion who do not want to undergo PEG tube insertion for various reasons.[

10,

11]

Notably, passing a swallowing test does not guarantee the end of NGT feeding for dysphagic patients. Patients with prolonged NGT insertion can lose oropharyngeal swallowing function[

4], and many patients who receive NGT feeding for a long time are unable to obtain sufficient amounts of nutrients orally immediately after NGT removal.[

12] There are also patients who require NGT reinsertion due to aspiration pneumonia or malnutrition. As patients with dysphagia have various etiologies and undergo different recovery processes, multiple and complex factors are associated with successful exclusive oral feeding. Frequent evaluation and appropriate management of dysphagia symptoms are very important strategies.

If the patient is a proper potential candidate for NGT removal, individualized and comprehensive approaches are needed to achieve full oral feeding. At this point, we would like to emphasize that a transitional period involving oral diet training is required to transition from long-term indwelling NGT feeding to exclusive oral feeding. However, the impact of long-term indwelling NGT insertion on oropharyngeal function remains largely unknown. Previous studies have shown various results regarding the effect of long-term NGT insertion on swallowing function.[

3,

4,

7]

This study aimed to evaluate the therapeutic effect of oral diet training in indwelling NGT patients with prolonged dysphagia. We also attempted to identify factors that may be associated with safe oral feeding attempts with the indwelling NGT.

2. Materials and Methods

This study was designed as a retrospective study. Dysphagic patients admitted to our institution between February 01, 2020, and December 30, 2022, were screened for this study. We reviewed patients’ medical chart who were evaluated VFSS during LGT feeding period. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of the Catholic University of Korea, Daejeon St. Mary’s Hospital (IRB No: DC22RISI0013). Because of the retrospective study design and minimal harm to the patients, informed consent was waived. All patient-specific identifiers were deleted from the data set before analysis.

2.1. Intervention

Medical records of 175 patients with severe dysphagia who were fed via an NGT for more than 4 weeks were retrospectively reviewed. The swallowing function of all patients was evaluated by a video-fluoroscopic swallowing study (VFSS). During the VFSS, patients received thick and thin barium while the NGT was insulted. Then, the patients’ NGTs were removed. Thirty minutes after NGT removal, the patients underwent a VFSS without an NGT. All VFSS processes were recorded, and three expert physiatrists interpreted the results. The diet type was determined according to the VFSS results.

When the patient could safely swallow a therapeutic food containing a certain viscosity without aspiration, the NGT was removed and oral feeding was recommended. However, if the total amount of oral intake was insufficient, oral attempts combined with NGT feeding were recommended based on the results of the VFSS. In this case, oral trials were permitted with a minimum dose of 100 ml at a time and a total amount less than 500 ml per day for the first few days until the patient could safely swallow orally without complications. Only soft and thick therapeutic foods with a viscosity similar to that of yogurt, not liquids or thin fluids, were allowed during oral trials. The oral trial volume was gradually increased according to the patient’s condition. In patients with severe dysphagia who were unable to safely receive oral feedings, NGT reinsertion was recommended, and oral trials were prohibited. All patients received a personalized dietary prescription according to the results of VFSS and received conventional dysphagia therapy. Follow-up VFSS was performed every 2 to 4 weeks, depending on the patient’s condition.

2.2. Patient Grouping

Patients were divided into one of the following 3 groups.

Group 1 included patients who could only consume food orally.

Group 2 included patients who could attempt oral feeding combined with NGT insertion. In this group, NGT feeding was the main feeding method. Patients in this group could intake therapeutic food orally but were not able to intake sufficient amount of food orally; thus, oral feeding with an indwelling NGT was attempted.

Group 3 included patients who were not able to attempt oral feeding with an indwelling NGT.

2.3. Evaluations

Swallowing function of patients was measured using the Functional Dysphagia Scale (FDS) and Penetration Aspiration Scale (PAS) according to the VFSS result. The VFSS was performed with a modified Logerman protocol by physiatrists.[

13] The FDS is a calculation system used to estimate the severity of dysphagia. This FDS is composed of 11 items, including 4 oral function items and 7 pharyngeal function items, which is observed during a VFSS.[

14] A higher FDS indicates more severe dysphagia.

The PAS can evaluate airway invasion. The score was determined according to the depth to which food materials pass the vocal cord into the airway and whether the food materials entering an airway can be expectorated.[

15] The laryngotracheal aspiration categories correspond to levels 6-8 on the PAS. A PAS score of 8 indicates that food materials enter the airway and pass below the vocal folds and that no effort is made to expectorate the material.

Cough function was measured using a peak cough flowmetry (PCF) after the VFSS. Voluntary coughing power was measured by performing patients cough as forcefully as possible using a peak flow meter. They were allowed to exert their maximal effort at least 3 times. The maximum value from the 3 trials was used for the statistical analysis. The PCF values are primary parameter widely used to estimate voluntary cough ability[

16,

17]

3. Results

As shown in the flowchart (

Figure 1), we reviewed the medical chart of 175 patients with prolonged dysphagia who were fed via an NGT for more than 4 weeks. A total of 129 patients were allowed to initiate an oral diet using therapeutic food after the VFSS. Among the patients, 37 (28.7%) required NGT reinsertion due to failure to achieve a sufficient oral feeding amount after NGT removal. These patients were assigned to Group 2, where therapeutic foods were tried orally while the NGT was inserted. Of the 46 patients who required NGT reinsertion after the VFSS, 12 (26.1%) had no aspiration of the thick or thin fluid during the VFSS with an NGT inserted. Therefore, these patients were also assigned to Group 2 and orally administered therapeutic foods with an NGT inserted. Of the 49 patients in Group 2 who underwent oral trials with an indwelling NGT, 39 (79.6%) were transitioned to exclusive oral feeding. A transition period of 3-8 weeks was required for these patients to achieve full oral feeding and removal of the NGT. Among the remaining 10 patients, aspiration pneumonia occurred in 4 patients; otherwise, no further attempts were made because the amount of oral intake was too low.

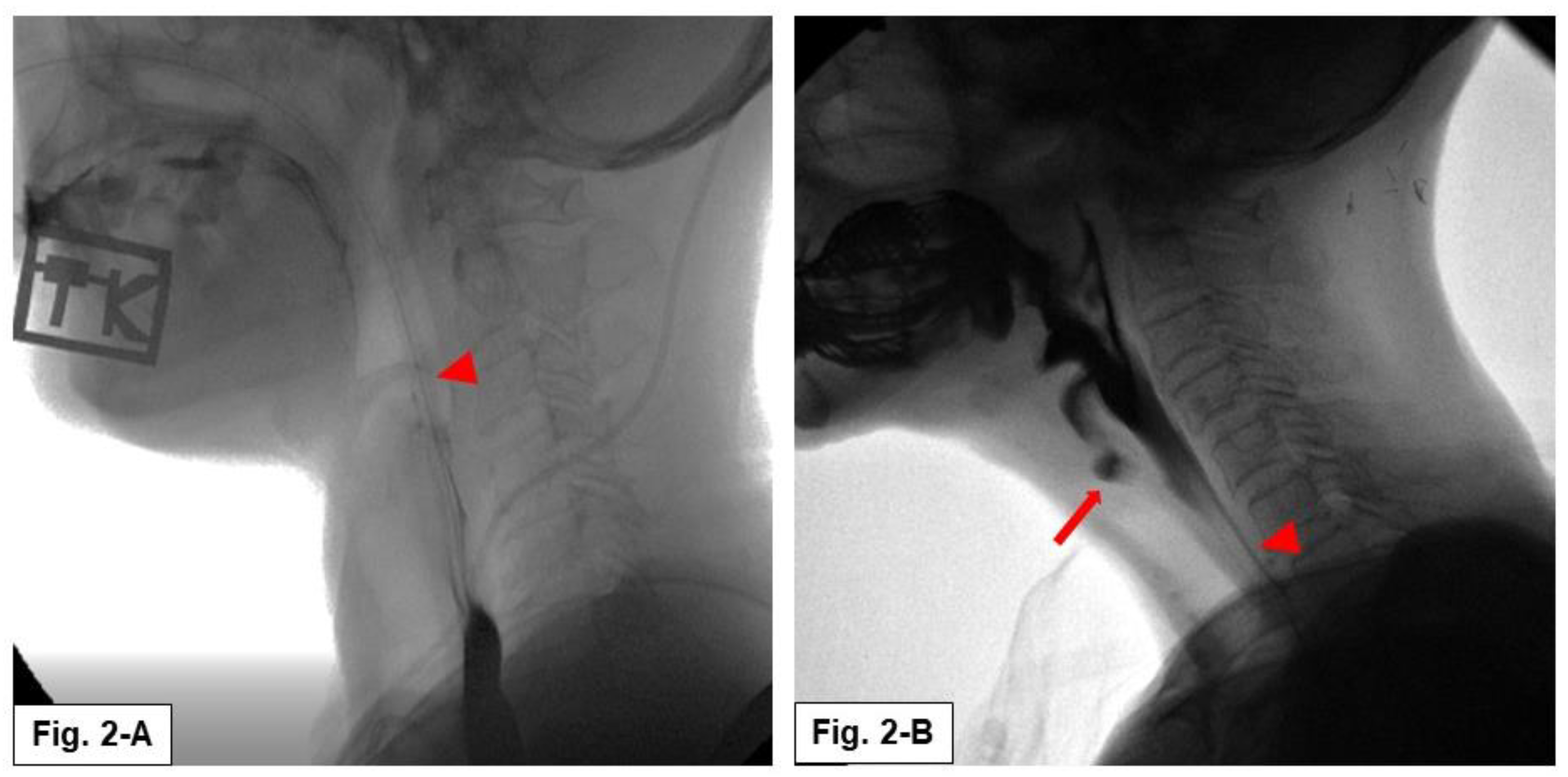

Figure 2 shows the results of the VFSS with an NGT inserted. Patients assigned to Group 2 had no aspiration when oral swallowing was attempted with an NGT inserted during the VFSS (

Figure 2A). These patients were allowed an oral feeding trial with an NGT inserted. However, the patients assigned to Group 3 showed aspiration when they tried to swallow orally with an NGT inserted (

Figure 2B). These patients were not allowed to undergo an oral feeding trial with an NGT inserted.

The demographic characteristics of the patients in each group are shown in

Table 1. The patients in Group 3 who were not allowed to attempt oral feeding trials with an NGT inserted were significantly older, had a longer duration of NGT feeding before VFSS evaluation, had a greater rate of tracheostomy, and had lower coughing ability than the patients in Groups 1 and 2.

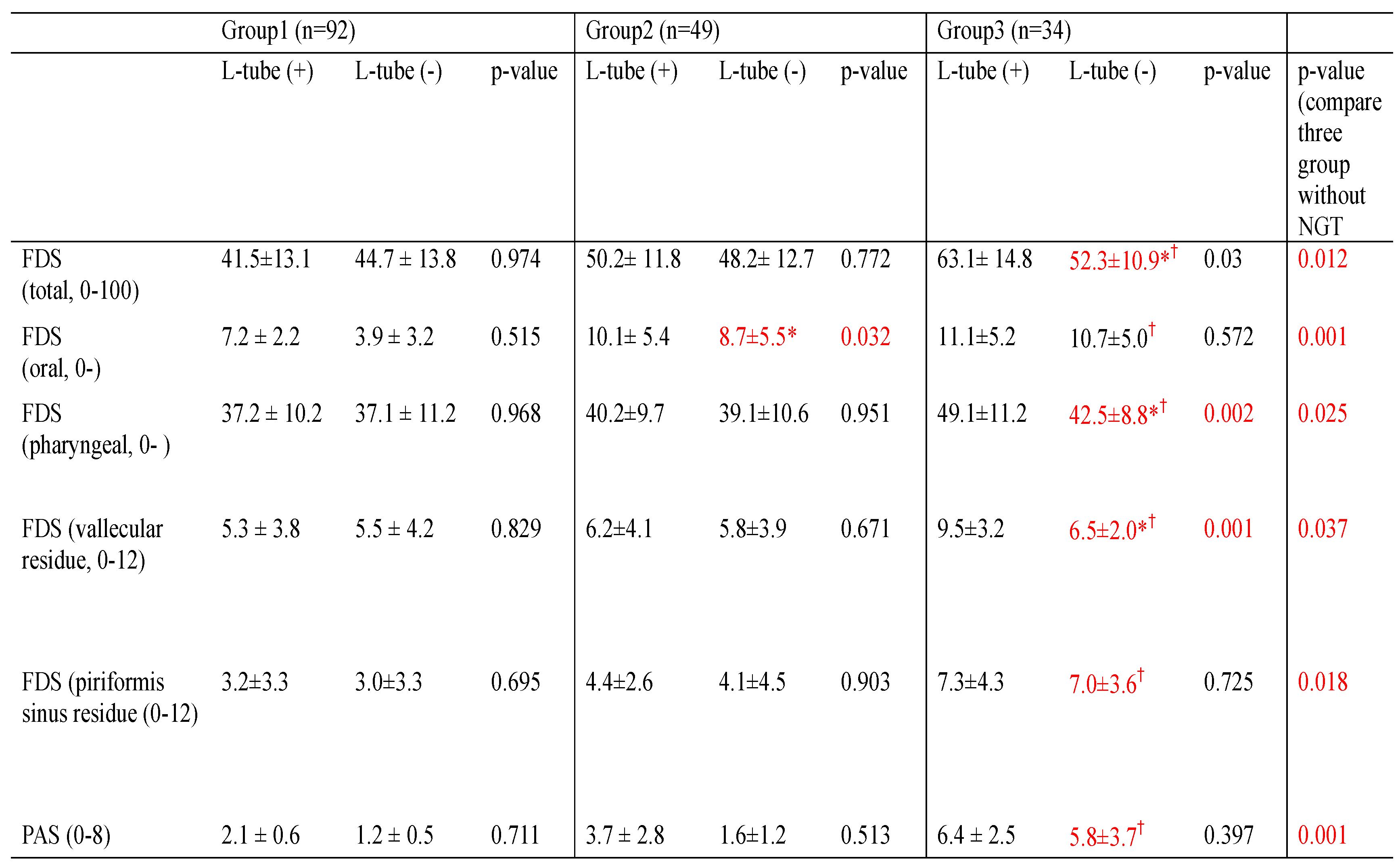

Table 2 shows the changes in swallowing function in each group with and without an NGT inserted during the VFSS. For the patients in Group 1 who could receive oral feedings only, the FDS score was not different between the VFSS with or without NGT inserted. The patients in Group 2 were eligible to undergo oral trials with an NGT inserted, and no significant differences were found in the FDS scores between the VFSS with or without NGT inserted during the VFSS except for the oral phase of the FDS. There was no significant aspiration during the VFSS when an NGT was inserted. However, the patients in Group 3, who required prolonged NGT feeding without oral trials, showed significant aspiration when they underwent VFSS with an NGT inserted. The amount of residue in the valleculae and pyriformis sinuses was greater with an NGT inserted than in those without an NGT inserted. When comparing conditions with and without an NGT inserted, the FDS and PAS scores of patients without an NGT inserted were slightly and significantly improved compared to those with an NGT inserted.

As mentioned in

Figure 2, the patients assigned to Group 2 did not undergo aspiration when performing VFSS with an NGT inserted, while the patients assigned to Group 3 underwent aspiration when performing VFSS with an NGT inserted. Comparing the results of the three groups without an NGT inserted condition, patients in Group 3 had significantly higher FDS scores in both the oral and pharyngeal phases, and higher aspiration scores in the PAS than did those in the other groups (

Table 2). The patients in Group 3 also had significantly lower coughing ability than patients who could undergo an oral trial with an indwelling NGT (

Table 1).

4. Discussion

In the present study, we aimed to investigate the therapeutic effect of oral diet training in long-term indwelling NGT patients with chronic dysphagia. Our results demonstrated that the effect of long-term NGT insertion on swallowing definitely differs according to various factors, and our study also quantitatively revealed the effect of successive oral feeding training with an NGT inserted in patients with long-term indwelling NGT. Most patients (79.6%) were able to obtain an adequate amount of nutrition only orally, and the NGT could be removed after oral diet training with an NGT inserted.

As mentioned previously, passing a swallowing test does not guarantee the end of NGT feeding. Our data showed that among the 129 patients who underwent NGT removal and started an oral diet after the VFSS, 37 (28.7%) returned to NGT feeding again because they did not achieve enough nutrients through oral feed after NGT removal. In most cases, the patients were able to obtain an adequate amount of nutrition orally after oral diet training with an NGT insertion state. And then, they finally could undergo NGT removal.

Furthermore, of the 46 patients who required NGT feeding after the VFSS, 12 (26.1%) were able to attempt oral diet training with an NGT inserted, and some of these patients achieved oral feeding exclusively after oral diet training. Patients with prolonged NGT insertion may lose oropharyngeal muscle swallowing function. For these patients, a transitional period involving training is required during the transition from NGT feeding to full oral feeding.

4.1. Factors Associated with Successive Oral Feeding

In this study, we attempted to identify factors that may be related to safe oral feeding with an indwelling NGT. Our results showed that in patients with sufficient cough function and no aspiration with an NGT inserted during the VFSS, oral diet training would be a useful and safe procedure for swallowing treatment.

Of the note, the patients in Group 3 who were unable to attempt oral feeding due to significant aspiration during the VFSS with an NGT inserted were significantly older and had a higher rate of tracheostomy than did the patients in Groups 1 and 2 (

Table 1).

Age could also be a significant factor in determining whether

a patient can receive oral feedings. Previous studies revealed that an indwelling NGT had little effect on swallowing ability in young and healthy adults,[

18] whereas the opposite result was demonstrated in healthy older adults.[

19] These studies showed an age-related effect on swallowing function.[

4,

20] Aging is directly related to the risk of multiple degenerative diseases and sarcopenic dysphagia.[

21]

The presence of a tracheostomy tube also negatively affects swallowing function. Several mechanisms have been proposed for swallowing dysfunction after a tracheostomy. Tethering of the larynx by the tracheostomy tube may result in decreased laryngeal elevation.[

22] The pharyngeal pathway could be directly obstructed by the tube cuff.[

23] Prolonged air diversion also causes desensitization of the larynx.[

24] Furthermore, tracheostomy also negatively affects coughing ability.[

17]

According to our results and previous findings, important factors prior to attempting oral feeding with an NGT inserted are sufficient cough function, no aspiration during a VFSS with an NGT inserted, younger age, and no tracheostomy. These factors are associated with the successive achievement of oral feeding even when patients have a long-term indwelling NGT. Because prolonged NGT insertion is an independent and negatively influencing factor in stroke recovery[

5], NGT must be removed as soon as possible when a patient can safely consume an oral diet.

4.2. Effect of NGT on Swallowing Function

Previous studies have reported various effects of NGT on swallowing, but the conclusions remain controversial. Anatomically, the NGT occupies the space of the nasopharynx, oropharynx and hypopharynx and can interfere with pharyngeal swallowing in patients with dysphagia.[

3] NGT feeding may interfere with the movement of the hyoid bone during swallowing.[

4,

25] In healthy adults, the presence of an NGT is associated with delayed initiation of maximal pharyngeal excursion. It also prolongs the opening time of the upper esophageal sphincter and the total swallowing time.[

18] A recent study demonstrated that the presence of an NGT negatively impacted swallowing function in elderly stroke patients. Swallowing evaluations were significantly different before and after NGT removal.[

4,

26]

The opposite results were showed in another study in which no significant differences were found in swallowing function before and after NGT removal.[

27] A review article concluded that the risk of aspiration from small amounts of liquid was not differ significantly before and after NGT removal, regardless of dysphagia or general functional level.[

25]

Why are NGT effects different according to these studies? Because dysphagia patients have various etiologies and exhibit multiple diverse clinical manifestations and recovery processes. Our results also revealed that the effect of long-term NGT insertion on swallowing definitely differs according to various factors. Thus, we triaged the patients and managed them differently according to their swallowing ability.

As previously described, multiplex factors appear to be associated with swallowing function and the ability to achieve full oral feeding after long-term NGT insertion, and it seems difficult to generalize and draw conclusions about the impact of long-term NGT insertion on swallowing. Individual evaluation and multidisciplinary approaches are needed for chronic dysphagia patients to achieve successful oral feeding.

4.3. Therapeutic Effect of Oral Diet Training with an Indwelling NGT

Generally, the goals of dysphagia treatment focus on safe oral diets and adequate nutritional intake, which include oral motor facilitation, electrical stimulation, and muscle strength training related to swallowing and breathing [

28,

29].

Oral motor therapy is a traditional effective dysphagia therapy [

28,

30] that consists of direct manual stroking, active oral motor exercises, and passive sensory stimulation. Direct oral diet training can certainly achieve these oral motor facilitation effects, and furthermore, it can induce the coordination of swallowing muscles. Direct oral training may also stimulate the pharyngeal walls during swallowing of food. It affects pharyngeal efferent nerves and triggers swallowing reflexes and pharyngeal wall movement. In patients with pharyngeal weakness due to neurogenic or degenerative dysphagia, the mechanical effect of an NGT may negatively affect swallowing [

4,

17]. However, after oral diet training, patients who had improved pharyngeal weakness or recovered dysphagia were unaffected by the mechanical effect of NGT on swallowing.

A previous study revealed that one of the factors associated with the achievement of oral intake ability in stroke patients was starting oral intake early.[

31] Our protocol could help patients start oral intake combined with an indwelling NGT early, resulting in better functional outcomes. Based on our results, we propose that, if the patient is a proper, potential candidate for NGT removal, our direct oral feeding training with an NGT inserted can accelerate NGT removal and help patients achieve full oral feeding. To date, direct oral training attempts with an NGT inserted have not been evaluated, and our trial is the first preliminary study.

4.4. Percutaneous Endoscopic Gastrostomy Tube Insertion

In terms of PEG tube insertion, there are no strict guidelines on who is the best indication or when is the best time. Current guidelines recommend PEG tube insertion in cases of prolonged dysphagia of more than 4-6 weeks[7-9], and many patients with prolonged NGT insertion do not want to undergo PEG tube insertion for various reasons.[

10] Some of the included patients had an indwelling NGT for a period exceeding 36 months.[

10]

In our study, among the 175 patients who had a prolonged indwelling NGT, 44 (25.1%) could not undergo NGT removal during the study period. We suggest that if

a patient is older and has no expectation of improvement in oral feeding due to brain lesions of the central pattern generator involved in swallowing function or advanced stages of dementia, it may be better to insert a PEG tube early to support adequate nutrition, improve the patient’s quality of life and prevent further complications. A recent review article recommended PEG tube insertion before weight loss due to disease to provide adequate nutrition.[

8] Even with PEG tube insertion, our oral diet training protocol can be applied if a patient’s condition improves and there are appropriate indications for our protocol.

4.5. Limitations

Our study was designed as a retrospective medical chart review, so we were unable to conduct a randomized controlled trial of oral diet training. In addition, this study included a small number of patients, and we could not divide patients according to brain lesion or disease characteristics. Patients had different indwelling NGT periods, and long-term follow-up VFSS could not be performed for all patients, which may have affected the results. Therefore, further studies involving more participants, and well-designed randomized controlled trials with longer follow-up periods are needed.

5. Conclusions

This study investigated the therapeutic effect of oral diet training with an NGT inserted in patients with chronic dysphagia. Our results quantitatively revealed the successive effects of oral feeding training with an NGT inserted in patients with long-term indwelling NGT. We also provided the appropriate indications for direct oral training. Direct oral training with an NGT inserted has therapeutic effects on oral motor facilitation, swallowing muscle coordination, and pharyngeal wall stimulation.

As chronic dysphagia patients exhibit different recovery processes associated with multiple factors, frequent evaluation and appropriate personalized management of dysphagia symptoms are very important strategies. We suggest that if the patient is a proper candidate for NGT removal, our method of direct oral feeding training with an NGT inserted could be a useful therapeutic strategy during the transitional period from long-term NGT feeding to successful oral feeding.

Author Contributions

Sook Joung Lee, Byung-chan Choi: Study design, Data collection, Manuscript preparation, Eunseok Choi, and Sangjee Lee: Literature search, Data collection Jungsoo Lee: Study design, Analysis of data, Review of manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of the Catholic University of Korea, Daejeon St. Mary’s Hospital (IRB No: DC22RISI0013).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to retrospective study design and minimal harm to the patients.

Data Availability Statement

Data of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

Non-financial competing interest. There are no financial competing interests to declare in relation to this manuscript.

Disclosures

No disclosures to declare.

Abbreviations

|

FDS: functional dysphagia scale |

|

NGT: nasogastric tube |

|

PAS: penetration aspiration scale |

|

PEG: percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy |

|

VFSS: videofluoroscopic swallowing study |

Appendix A. The VFSS video file of Group 2 patient (swallowing with NGT insertion)

Appendix B. The VFSS video file of Group 3 patient (swallowing with NGT insertion)

References

- Gomes, G.F.; Pisani, J.C.; Macedo, E.D.; Campos, A.C. The nasogastric feeding tube as a risk factor for aspiration and aspiration pneumonia. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2003, 6, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.K.; Koo, K.I.; Hwang, C.H. Intermittent Oroesophageal Tube Feeding via the Airway in Patients With Dysphagia. Ann Rehabil Med 2016, 40, 794–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, G.; Baek, S.; Park, H.W.; Kang, E.K.; Lee, G. Effect of Nasogastric Tube on Aspiration Risk: Results from 147 Patients with Dysphagia and Literature Review. Dysphagia 2018, 33, 731–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.Y.; Chen, J.M.; Ni, G.X. Effect of an indwelling nasogastric tube on swallowing function in elderly post-stroke dysphagia patients with long-term nasal feeding. BMC Neurol 2019, 19, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galovic, M.; Stauber, A.J.; Leisi, N.; Krammer, W.; Brugger, F.; Vehoff, J.; Balcerak, P.; Müller, A.; Müller, M.; Rosenfeld, J. , et al. Development and Validation of a Prognostic Model of Swallowing Recovery and Enteral Tube Feeding After Ischemic Stroke. JAMA Neurol 2019, 76, 561–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, W.H.; Lim, M.H.; Seo, H.G.; Seong, M.Y.; Oh, B.M.; Kim, S. Development of a Novel Prognostic Model to Predict 6-Month Swallowing Recovery After Ischemic Stroke. Stroke 2020, 51, 440–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, C.A., Jr.; Andriolo, R.B.; Bennett, C.; Lustosa, S.A.; Matos, D.; Waisberg, D.R.; Waisberg, J. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy versus nasogastric tube feeding for adults with swallowing disturbances. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015, 2015, Cd008096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietrich, C.G.; Schoppmeyer, K. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy - Too often? Too late? Who are the right patients for gastrostomy? World J Gastroenterol 2020, 26, 2464–2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tae, C.H.; Lee, J.Y.; Joo, M.K.; Park, C.H.; Gong, E.J.; Shin, C.M.; Lim, H.; Choi, H.S.; Choi, M.; Kim, S.H. , et al. Clinical practice guidelines for percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Clin Endosc 2023, 56, 391–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, A.; Sowa, P.M.; Banks, M.D.; Bauer, J.D. Home Enteral Nutrition in Singapore’s Long-Term Care Homes-Incidence, Prevalence, Cost, and Staffing. Nutrients 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.Y.; Lai, J.N.; Kung, W.M.; Hung, C.H.; Yip, H.T.; Chang, Y.C.; Wei, C.Y. Nationwide Prevalence and Outcomes of Long-Term Nasogastric Tube Placement in Adults. Nutrients 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Ma, D.; Meng, X.; Zhang, M.; Sun, J. Predictors of complete oral feeding resumption after feeding tube placement in patients with stroke and dysphagia: A systematic review. J Clin Nurs 2023, 32, 2533–2546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmer, J.B.; Kuhlemeier, K.V.; Tippett, D.C.; Lynch, C. A protocol for the videofluorographic swallowing study. Dysphagia 1993, 8, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, T.R.; Paik, N.J.; Park, J.W. Quantifying swallowing function after stroke: A functional dysphagia scale based on videofluoroscopic studies. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2001, 82, 677–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbek, J.C.; Robbins, J.A.; Roecker, E.B.; Coyle, J.L.; Wood, J.L. A penetration-aspiration scale. Dysphagia 1996, 11, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, Y.; Takahashi, M.; Wada, F.; Hachisuka, K. Differences in the peak cough flow among stroke patients with and without dysphagia. J uoeh 2013, 35, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, M.K.; Lee, S.J. Changes in Swallowing and Cough Functions Among Stroke Patients Before and After Tracheostomy Decannulation. Dysphagia 2018, 33, 857–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huggins, P.S.; Tuomi, S.K.; Young, C. Effects of nasogastric tubes on the young, normal swallowing mechanism. Dysphagia 1999, 14, 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pryor, L.N.; Ward, E.C.; Cornwell, P.L.; O’Connor, S.N.; Finnis, M.E.; Chapman, M.J. Impact of nasogastric tubes on swallowing physiology in older, healthy subjects: A randomized controlled crossover trial. Clin Nutr 2015, 34, 572–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, J.; Hamilton, J.W.; Lof, G.L.; Kempster, G.B. Oropharyngeal swallowing in normal adults of different ages. Gastroenterology 1992, 103, 823–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sire, A.; Ferrillo, M.; Lippi, L.; Agostini, F.; de Sire, R.; Ferrara, P.E.; Raguso, G.; Riso, S.; Roccuzzo, A.; Ronconi, G. , et al. Sarcopenic Dysphagia, Malnutrition, and Oral Frailty in Elderly: A Comprehensive Review. Nutrients 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldsmith, T. Evaluation and treatment of swallowing disorders following endotracheal intubation and tracheostomy. Int Anesthesiol Clin 2000, 38, 219–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betts, R.H. POST-TRACHEOSTOMY ASPIRATION. N Engl J Med 1965, 273, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaker, R.; Milbrath, M.; Ren, J.; Campbell, B.; Toohill, R.; Hogan, W. Deglutitive aspiration in patients with tracheostomy: effect of tracheostomy on the duration of vocal cord closure. Gastroenterology 1995, 108, 1357–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, H.J.; Kim, L.; Ryu, B.J.; Kim, Y.H.; Park, S.W.; Cho, D.G.; Lee, C.J.; Ha, K.W. Influence of Nasogastric Tubes on Swallowing in Stroke Patients: Measuring Hyoid Bone Movement With Ultrasonography. Ann Rehabil Med 2018, 42, 551–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nam du, H.; Jung, A.Y.; Cheon, J.H.; Kim, H.; Kang, E.Y.; Lee, S.H. The Effects of the VFSS Timing After Nasogastric Tube Removal on Swallowing Function of the Patients With Dysphagia. Ann Rehabil Med 2015, 39, 517–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.G.; Wu, M.C.; Chang, Y.C.; Hsiao, T.Y.; Lien, I.N. The effect of nasogastric tubes on swallowing function in persons with dysphagia following stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2006, 87, 1270–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cosentino, G.; Todisco, M.; Giudice, C.; Tassorelli, C.; Alfonsi, E. Assessment and treatment of neurogenic dysphagia in stroke and Parkinson’s disease. Curr Opin Neurol 2022, 35, 741–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, K.C.; Seo, S.M.; Woo, H.S. Effect of oral motor facilitation technique on oral motor and feeding skills in children with cerebral palsy : a case study. BMC Pediatr 2022, 22, 626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvedson, J.; Clark, H.; Lazarus, C.; Schooling, T.; Frymark, T. The effects of oral-motor exercises on swallowing in children: an evidence-based systematic review. Dev Med Child Neurol 2010, 52, 1000–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikegami, T.; Kobayashi, M.; Matsumoto, S. FACTORS ASSOCIATED WITH ORAL INTAKE ABILITY IN PATIENTS WITH ACUTE-STAGE STROKE. J Rehabil Med Clin Commun 2021, 4, 2657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).