1. Introduction

This paper emerges from a keen interest in examining the governance models devised and implemented to govern smart cities. While the inception of the smart city concept in the 1990s was intertwined with aspirations for sustainable development, critical perspectives [

1] have highlighted the role of multinational technology corporations such as IBM, Cisco, Microsoft, Samsung, and Siemens in propelling the proliferation of smart cities worldwide [

2,

3]. In light of this, it is relevant to examine how governance models could facilitate sustainability through the generation of public value from data, thereby mitigating the influence of corporate-centric governance structures.

What are the governance structures facilitating the development of sustainable smart cities? How are smart cities governed? What are the various governance models employed? And what are the advantages and drawbacks associated with each?

Data is assuming an increasingly pivotal role in comprehending and addressing urban issues, with cities emerging as focal points of information [

2,

4,

5,

6]. With 57% of the global population residing in urban areas and contributing roughly 80% of greenhouse gas emissions, the concept of smart cities has surfaced as a potential solution to mitigate urban impacts on the environment and confront challenges associated with global urbanization [

2,

7,

8]. The advocacy for data-driven approaches to inform decision-making aligns with international sustainability initiatives such as the 2015 Paris Agreement on climate change and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development [

6,

9]. The World Data Forum and its Cape Town Global Action Plan have underscored the necessity of timely and high-quality data to enhance local government decision-making and advance global sustainability agendas [

9].

This paper seeks to compare the advantages and limitations of three governance models: top-down, hybrid, and bottom-up. A theoretical framework for smart city governance is proposed, drawing from a rapid review of literature on public governance in the context of smart cities. Additionally, the review identifies instances of smart city governance to scrutinize the strengths and weaknesses of each model.

This paper delves into the processes, objectives, structures, and governance frameworks of 15 smart cities: Amsterdam, Barcelona, Turin, Vienna, Helsinki, London, Berlin, Eindhoven, Manchester, Stavanger, Dubai, Seoul, San Francisco, Parramatta, Newcastle, and Sunshine Coast. It contributes by juxtaposing the objectives, progress, and constraints of each model. It posits that top-down approaches often overlook sustainability concerns compared to hybrid and bottom-up approaches and may potentially engender corporate-centric outcomes. Through comparative analysis of governance models across different cities, this paper aids in discerning the advantages and drawbacks of each model, offering a framework to assist city governments and stakeholders in delineating their smart city strategies and governance structures. Additionally, it furnishes a governance framework for smart cities based on insights gleaned from the cities analyses.

The initial section of this paper outlines the materials and methods employed. The subsequent section presents the findings, including a discussion on the definition of the smart city concept. It also delves into the literature on public governance concerning smart city governance, underscoring the significance of governmental leadership in formulating smart city strategies and collaborating with stakeholders and citizens. Moreover, it introduces and expounds upon top-down and bottom-up governance models, proposing a theoretical framework for smart city governance. Subsequently, the results pertaining to the governance processes and models of the 15 cities are expounded upon. The third section compares the objectives, governance models, advantages, and limitations of the cases, followed by a discussion of the findings.

2. Materials and Methods

The first step of the research process consisted in an exploratory literature review on the role of technologies and data in smart cities and data governance. Then, a rapid review was conducted on the governance of smart cities. A search was done in Google scholar with the key words “(Smart cities AND Governance AND Public Policy AND Regulation) (Case studies OR Empirical studies)”. The 10 first pages of the 17 900 results were consulted. An additional search with the same key words was done in the EBSCO database.

A first selection of 106 references was done, including books, book chapters and peer-reviewed journal articles. The including criteria was the relevance of the article, based on its theoretical, literature review or empirical contribution and number of citations. Also, case studies, frameworks, and literature review published papers between 2015 and 2021 were included. Two members of the research team performed the abstract screening, and the full text screening and discussed the relevance of the inclusion of each one in the literature review. Papers that proposed governance frameworks without empirical support were excluded. A total of 28 articles were included in the literature review. All the found case studies were included in the analysis.

First, the literature analysis focused on the smart cities’ concept, definitions, goals, and challenges. Second, the governance challenges were studied, and the role of governments and stakeholders was analyzed. Third, the advantages and limits of the different models of governance were compared. Based on this academic knowledge on the governance of smart cities, a theoretical framework for smart city governance represented in a figure was built. Furthermore, 15 smart cities were compared relative to their goals. The ones that focus on sustainable development were compared with those that aim at improving citizens’ quality of live and infrastructure efficiency, and the ones focusing on innovation and economic development. Then, the top-down, hybrid, and bottom-up examples were compared, as well as the coordination offices of different cities. A table was built to compare the cities’ goals, governance models, advancements, and limits which enabled to reach conclusions on the advancements and limits of each model. Finally, a framework for smart cities was built based on the lessons-learned from the cities and the knowledge generated by the reviewed literature.

3. Results

3.1. The smart City Definition

3.1.1. Defining Smart City Goals

This section discusses the concept of smart city focusing on the identification of smart city goals. The variegated origin of smart cities that are at the crossroads of sustainable development and the development of urban technologies by technology corporations is reflected in the lack of a clear definition of this concept that identifies multiple solutions and city programs with different technologies and goals, while smart city governance and citizens are not often considered in the definition [

10]. Meijer [

11] argues that this concept has a normative orientation, and its meaning is unclear.

Actually, the concept of smart city is related to other similar notions: Intelligent city, digital city, sustainable city, techno-city, and wellbeing city. Identifying the ideas involved in these concepts is relevant to help municipal governments and stakeholders defining their goals according to the needs of their cities, also considering contextual factors such as culture, social, economic, and environmental problems as well as economic, institutional, technological, and human capacities [

10].

Table 1 shows the goals of technology use for each concept.

To better identify their goals, local elements must be considered. Multiple factors are involved in the design and implementation of smart cities by municipal governments, including the geographical area or the land, the technologies, the citizens, and the government [

10]. Sadowski and Malsen [

12] argue that there is not a universal way of building smart cities. This is important for the design of smart cities’ models of governance. The spatial, political, cultural, and material contexts are important elements of their design. Thus, the modes of building smart cities are variegated. Smart cities have different practices and outcomes. The influence of local elements such as administrative culture, demographic and political ones require attention. Further, it is relevant to take into consideration the potential for local cooperative knowledge and situational elements such as local political, economic, institutional, cultural, and social conditions and their interaction with technological choices [

13].

Challenges include the implementation of smart cities in developing countries and elsewhere due to financial costs of investing in and maintaining infrastructures, socio-economic issues, legal and policy barriers, lack of planning, coordination, and collaboration and lack of human resources

[9–11[

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]

].

3.1.1. Types of Smart City Definitions: The Importance of Governance

According to Meijer and Bolivar [

21], there are three types of smart cities’ definitions. Those that focus on:

− Smart technologies such as ICT, smart transport, transport regulation and smart grids to assess how technologies can enhance the urban system.

− Smart people or educated people and have a human resource perspective.

− Governance or smart collaboration.

An example of definition that focuses on governance and sustainability is formulated by [

10]. This definition has the advantage of linking technologies with governance processes and the creation of public value for citizens:

“A smart city is a well-defined geographical area, in which high technologies such as ICT, logistic, energy production, and so on, cooperate to create benefits for citizens in terms of well-being, inclusion and participation, environmental quality, intelligent development; it is governed by a well-defined pool of subjects, able to state the rules and policy for the city government and development”.

The perspective that focuses on governance, places the interactions between multiple stakeholders across urban networks that collaborate for the city governance as the most important aspect of smart cities. This concerns the governance of sustainable collaborative networks [

22]. This approach also gives importance to citizens’ participation. Meijer [

11], for example, argues from a public governance perspective that smart-cities are socio-technical constructions. This means that there is a mutual influence between governance interactions and digital technologies. As smart cities result from political and administrative interactions, actors play games according to institutional rules. Social and technological structures that emerge from interactions between multiple stakeholders are created. Meijer proposes the notion of “datapolis” to refer to the complex relationships between the political community and digital or data infrastructures [

11].

A central idea of the public governance approach to smart cities is that governments should play an active role in the development of smart cities and should drive goals, policies, rules, and investments. Lack of proper governance creates dispersed investments as well as lack of synergies [

10]. Proper governance is important for the success of smart cities’ implementation[

23]. It enables to create a common vision of the city as well as common goals that emerge from shared processes that make participate all relevant stakeholders. Governance includes the definition of policies that drive processes to a common goal, as well as the formulation of rules that define actors’ rights and duties and the projects’ boundaries and scope. The goal is that the implementation of technologies generates public value such as institutional trust and high-quality services for citizens.

3.2. Governing the smart city

3.2.1. The Governance Barriers for the Transformation of Cities into Smart Cities

This section discusses the governance limits in the construction of smart cities. Smart city governance can be regarded within a public management perspective that sees the implementation of public policies as the result of strong collaborations between governments and stakeholders [

24]. According to Meijer [

11] there are 3 types of actors: State, market, and civil society.

An element to consider is that private interests can conflict with public ones, limiting collaboration. As collaboration between the public sector, the private sector and civil society can generate conflicts of interests [

11], the interaction between the public and the private sector is based on exchange arrangements in which private actors participate in networks and partnerships. Thus, enhancing cooperation, partnerships and networks is important, as well as public-private partnerships. Governing the smart city also requires influencing the interactions between the different actors [

11].

However, one of the most important obstacles for the transformation of cities into smart cities is the lack of proper governance arrangements. The multiple agencies, stakeholders and interests involved in governance make it a very complex task. According to Ruhland [

13], a governance system is required to make communicate the actors, to enable information-sharing and decision-making. Smart city governance can be regarded as a process in which multiple stakeholders, who have different roles and forms of organization are regulated by legislation and polices and use data and technologies. They cooperate to achieve specific outputs for cities. Thus, organizational and coordination structures are important elements of smart governance. Structures can be political, administrative, or external. They can include associations that make participate multiple stakeholders. Intergovernmental, interagency, and inter-sectoral networks can enhance collaboration [

13].

3.2.2. Enhancing Collaboration through Governance Structures: The Existing Models of Governance

This section presents different models of governance that have been implemented by smart cities. Governance models can vary from hierarchical to network approaches. In hierarchical models, actions are directed by governments, while in network approaches, actors’ interactions are more horizontal. There is no consensus about whether governments should adopt a top-down or a bottom-up model of governance. Top-down strategies are leaded by governments that define the smart city framework and the long-term goals. Bottom-up approaches emerge from self-regulated processes of organization and are expected to be driven by civil society and citizens’ participation in the development of ICT solutions.

Furthermore, the form taken by smart urbanism can also be corporate-centric, citizen-centric, or planner-centric. The corporate-centric governance model is applied when smart cities are developed and operated according to the visions, services, and solutions of technology companies. Citizen-centric forms of governance are driven by citizens or by civil society’s participation and community values. The planner-centric approach refers to the design and implementation of smart initiatives by government strategic planners [

12].

There are different strategies that can be based on technology focused or holistic approaches, double, triple or quadruple-helix collaboration models, integrated or mono-dimensional logics of intervention [

25]:

− Holistic approaches integrate technology development and implementation with governance processes.

− Double-helix collaboration models are mainly between governments and technology corporations.

− Triple-helix models include governments, the industry, and universities, but have insufficient citizens’ participation.

− Theoretically, quadruple-helix collaboration models are horizontal and based on a more equal interaction between governments, citizens, universities, and technology companies. In this last model, the state becomes a node in a governance network.

Top-down approaches are sometimes associated with the defense by governments of technology corporations’ interests [

25]. However, this could be avoided by designing strategies that aim to generate public value from data and that make participate civil society in smart cities’ building. Thus, instead of seeing top-down approaches as opposed to bottom-up ones, it could be relevant to reflect about how to combine both approaches to make governments lead the processes to create participative strategies of smart-city building.

3.2.3. The Need of Defining Clear Roles for Smart City Governance: Governments as Leaders

This section discusses the role of governments and stakeholders in the development of smart cities. According to the smart collaboration approach on smart cities, smart governance is about collaboration between multiple stakeholders through an active engagement of citizens and stakeholders [

21]. According to this perspective, the role of governments must be reconsidered to play a leading role in coordinating and managing the city. Governments can act as regulators, coordinators, and funders [

13]. Thus, within a logic of collaboration, participation, and partnership, governments make participate all the interested parties. The idea of smart city involves networks of collaboration leaded by governments that create urban environments based on information and participation.

There are different dimensions of governance:

According to Bolivar [

24], stakeholders could play a role in the collection of knowledge and ideas about smart projects. Public administrations should promote a shared conception of public interest. Local governments could act as facilitators or initiators. They also should establish the structure of governance of the network, as well as the governance model that should be collaborative or participative [

24].

Data also plays a central role in urban governance being a data-driving form of governance. By studying organizational criteria to build sustainable collaborative networks, Yahia and colleagues [

22] show that to promote processes of co-governance, governments should build collaborative environments and sustainable collaborative networks. This includes an identification of smart organizational factors (efficiency, flexibility, and robustness) to promote collaboration, participation, and coordination between the actors of smart networks. Smart indicators should also be defined to measure smart criteria.

Furthermore, there are 3 types of relations between actors: Coordination, power, and control. Policymakers must decide which of the smart criteria they privilege. According to Yahia and colleagues [

22], governments should reduce power and control, while enhancing coordination because decreasing power relations in networks increases flexibility. The development of resilient, sustainable, robust, flexible, and efficient socio-technical systems is also crucial for co-governance processes.

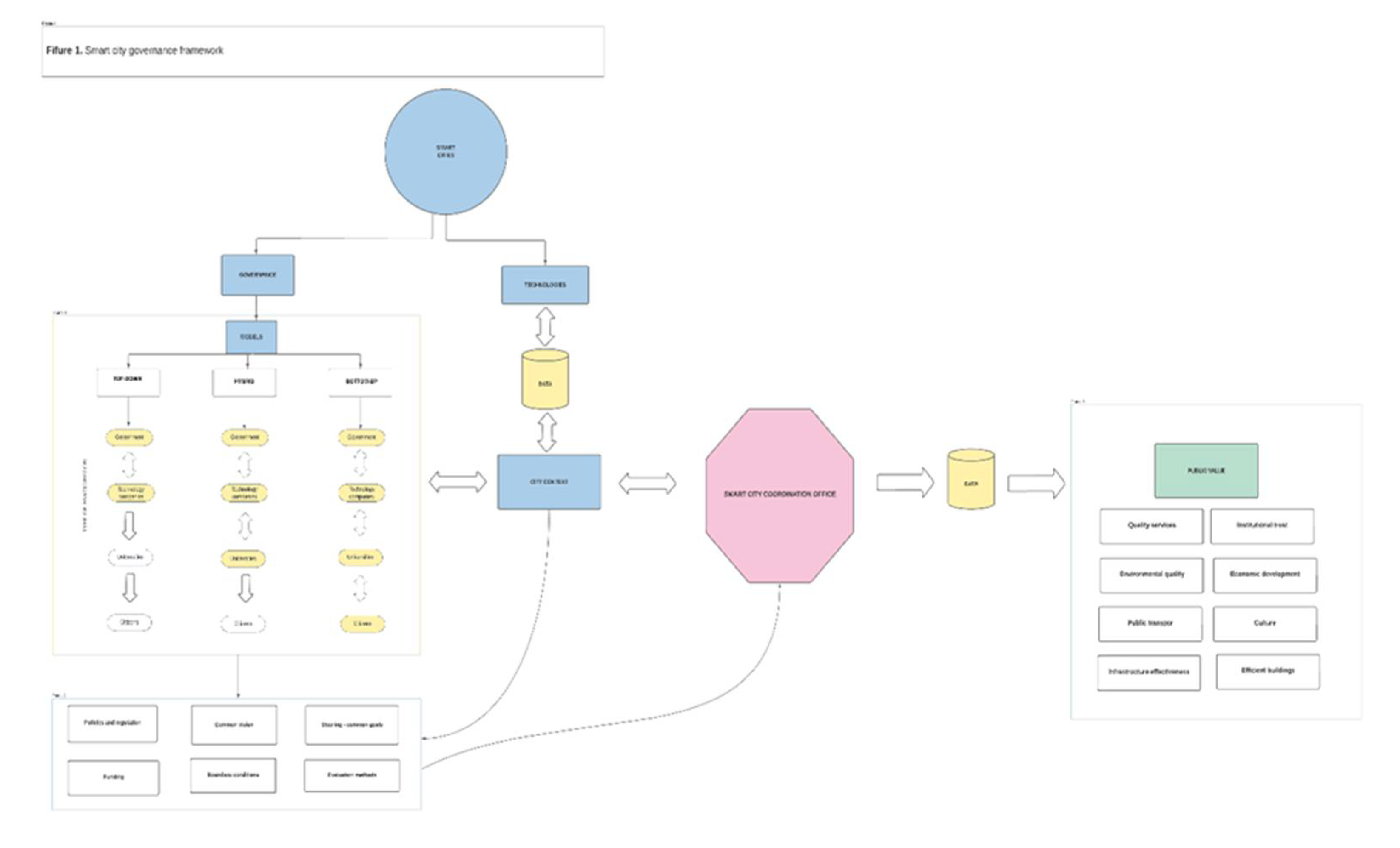

3.2.4. Theoretical Framework for Smart City Governance

This section proposes a theoretical framework for smart city governance. Based on the elements identified on the literature review on smart city governance, figure 1 represents a theoretical framework for the governance of smart cities. The smart city is regarded as a socio-technical construction resulting from governance and technological inputs. Governments, technology companies, universities, and citizens are the main actors participating in governance arrangements. However, these arrangements can vary according to the degree of participation of each actor. In the double-helix collaboration model, the two main participants are municipal governments and technology companies. In the triple-helix model, the main participants are governments, technology companies and universities. The quadruple helix model also counts with a high involvement of citizens.

In its pure form, in a top-down approach to smart city governance, there is a mutual influence between governments and technology companies in the definition and prioritization of goals and policies. Governments tend to lead the processes to defend the interests of technology companies. In a hybrid form between top-down and bottom-up approaches, governments lead the processes to make participate stakeholders. In this form of governance, there is a mutual influence between governments, technology companies, and universities with less participation of citizens. In a bottom-up approach to governance, civil society, citizens, and other stakeholders have a strong involvement in the process definition, development and implementation, and governments are less involved in strategic planning and coordination.

Depending on the type of governance adopted – top-down, bottom-up or hybrid – the involved actors consider the socio-cultural, economic, political, institutional, historical, and technological context of the city as well as its capacities, to steer or define common goals, a common vision of the city, its policies, and forms of regulation. In the hybrid and bottom-up forms of governance, stakeholders are active participants in the definition of goals and priorities through knowledge sharing. Other elements to be defined are funding opportunities, boundary conditions, the ways of monitoring and evaluating the outcomes, as well as the definition of a smart city coordination office that can be centralized or decentralized. The smart city coordination office is represented as the heart of the governance process that promotes data and technology integration and usage, and enables the synergies, communication, coordination, collaboration, information-sharing and decision-making activities that promote the development of the smart city as a socio-technical construction that emerges from the integration of governance with technologies and data. This combination between technological digital developments and governance processes generates outputs for value creation by smart cities for citizens. This includes quality services, institutional trust, environmental quality, economic development, improved mobility and public transports, culture, infrastructure, and buildings’ efficiency.

Figure 1.

Smart city governance framework.

Figure 1.

Smart city governance framework.

3.3. Cities

This section presents the examples about the governance design and implementation in 15 cities: Amsterdam, Barcelona, Turin, Vienna, Helsinki, London, Berlin, Eindhoven, Manchester, Stavanger, Dubai, Seoul, San Francisco, Parramatta, Newcastle, and Sunshine Coast. It first presents the different cities’ objectives for smart city development. It then exposes the cities that focus on sustainable development, while improving the economy; the example of the city of Dubai that aims at improving citizens’ quality of life and enhancing infrastructure effectiveness; as well as the cities oriented toward innovation and economic development. This is followed by a presentation of top-down, bottom-up and hybrid cities, as well as different forms of smart city coordination offices.

3.3.1. Goals for Smart Cities Development

Cities have different objectives for smart city development, including:

− The promotion of sustainable cities to address environmental and climate change issues

− Improving the economy by developing a smart and data economy

− Making infrastructures and buildings more efficient

− Improving transport

− Improving citizens’ quality of life

− Making governments and administrations more effective

− Promoting innovation

Strategies tend to combine many of the goals mentioned above, but some of them prioritize specific objectives such as sustainable development, economic development, infrastructure efficiency, or smart administration. Barcelona, for example, prioritized the improvement of the efficiency of its administration[

26]. San Francisco has been giving importance to the promotion of open data transparency with a strategy focused on government efficiency and innovation. In the case of Seoul, there is a focus on the promotion of services that support smart city’s infrastructure [

27]. In other cases, such as those of Turin and Vienna, the development of smart strategies was influenced by opportunities for funding[

26].

3.3.2. Cities That Focus on Sustainable Development While Improving the Economy: Amsterdam, Barcelona, Turin, Vienna, and the Triangulum International project (Eindhoven, Manchester, and Stavanger)

Amsterdam, Barcelona, Turin, and Vienna aim at promoting sustainable development to address climate change and reduce pollution and energy consumption. These cities are also oriented toward the improvement of the economy, the promotion of investments and the improvement of citizens’ quality of life[

26]. A relevant example with regards to the development of sustainability, is the one of the Triangulum International Project, in which participate the cities of Eindhoven, Stavanger and Manchester. Triangulum is inspired by the successful experiences of Leipzig, Sabadell and Prague that used a standardized approach to smart sustainable development. Triangulum aims to reach an important reduction of GHG emissions and energy demand, improving quality of life, making mobility clean, and efficient and enhancing the economies. It integrates smart technologies in the mobility, energy, and ICT sectors to make them leaders in smart sustainable development, seeking a drastic reduction of GHG emissions to sustainable levels. Like Vienna, the project also gives importance to the development of innovation through processes of co-creation and citizens’ participation[

28].

3.3.3. Improving Citizens’ Quality of Life and Infrastructures’ Efficiency: The City of Dubai

In the case of Dubai, the smart city emerges from the evolution of e-government into smart government. In 2014, the ruler of Dubai, Mr. Sheikh Mohammad, created the Dubai smart city office to develop the smart city. The slogan was to make Dubai the happiest city to improve citizens’ quality of life. There is a happiness champion who communicates with stakeholders, and citizens and makes them participate in the development, coordination, and implementation of programs through processes of co-creation.

This includes a focus on smart government and citizens. However, the policy covers different fields of application with a strong focus on energy, mobility, and health. The sustainability goal is mentioned in policies but is not enough applied and is regarded as unattainable in the urban context of Dubai[

29]. This shows that despite cities use similar reasons to develop their smart strategies, their visions and applications vary according to their own urban contexts. Despite the existence of a set of similar goals for smart cities’ development, visions, strategies, and implementations are influenced by contextual factors such as institutional history, infrastructure capacities, political orientations, the economy and so on.

3.3.4. Cities Oriented toward Innovation and Economic Development: Parramatta (Western Sydney), Newcastle (north of Sydney) and Sunshine Coast (north of Brisbane, Australia)

The Australian cities show how smart cities strategies can emerge from economic transitions and from needs to generate new economic opportunities through the development of smart economies, while using infrastructure’s capabilities. In the case of Newcastle, the economy used to be based on mining. The strategy was embedded in the sustainable transition from the industrial economy to an economy based on innovation and knowledge. In the Sunshine Coast Council, there was a need to revitalize the economy that used to be based on tourism, and services. The city of Parramatta developed local initiatives with little participation of large technology companies [

12].

3.3.5. Top-Down, Bottom-Up and Hybrid Examples

3.3.5.1. Top-Down Cases: Seoul, Dubai, Berlin, and London

Smart city services tend to be developed by e-government initiatives with little participation of users. In Seoul, there is a top-down governance model that supports large technology companies with little support to start-ups and poor development of sustainable development initiatives. This creates a “corporate centric” mode of governance. Smart city building reflects the visions, services, and solutions of large technology companies such as IBM and Cisco[

12]. The top-down governance approach involves the private sector in partnerships. Little funding is provided to promote initiatives by local start-ups and middle-sized companies. Seoul also needs a higher promotion of sustainability services through smart and open urban infrastructure. More investment in smart urban infrastructure for sustainability is required as well as incentives to promote green initiatives[

27].

Like in Seoul, the smart city in Dubai originates in e-government initiatives. Dubai adopted a top-down model of governance with a defined strategy and strong leadership. The Dubai smart city office is responsible for the development and implementation of programs and solutions. There is a higher support to start-up’s initiatives than in Seoul. There is also support to sustainable solutions, but the focus is on infrastructure[

29].

The coordination role of the Dubai smart city office has the advantage of enabling the collaboration with other government’s departments. It also collaborates with the private sector and other stakeholders, supporting innovations and start-ups in areas such as sustainable solutions, smart applications, and IoT. The office collaborates with telecommunications services, the Dubai Electricity and Water Authority (DEWA), the Road and Transport Authorities, Dubai Pulse, among others. DEWA has been developing smart initiatives, including installation of solar panels on rooftops, smart meters, smart grids, infrastructure, and electric vehicles[

29].

Another advantage of this top-down model is a clear definition of responsibilities. Different actors are responsible for the development of the smart city. The Dubai Data Establishment, for example, oversees regulation. The government’s data is shared in a data platform managed by the DDE, a government entity. The application DubaiNow is a single application for all services that manages, disseminates data, and offers public services to citizens[

29].

The examples of Berlin and London show that the adoption of a top-down approach can facilitate regulation. Berlin and London have smart cities agendas and offer indirect support to urban sharing to promote ICT innovation as well as start-ups. Urban sharing governance refers to the utilization of ICT by organizations to facilitate sharing among partners. Governments can act as regulators, providers, enablers, and/or consumers [

30].

Both cities’ motivation to promote urban sharing is economic development and innovation, acting as regulators. In London, regulation has been enforced at a city level, while Berlin has experienced a fragmented enforcement and has adopted a more restrictive attitude than London. London has established channels of communication with urban sharing organizations[

30].

However, both modes of governance remain top-down forms of policy approaches, with little participation of urban sharing organizations in the co-production of policies and regulations. For example, London provides support to large for-profit urban sharing organizations[

30].

3.3.5.2. Between top-down and bottom-up: Hybrid governance in European (Amsterdam, Barcelona, Helsinki, Turin, Vienna), and Australian (Parramatta, Newcastle, and Sunshine Coast) cases

Amsterdam, Barcelona, Vienna, and Helsinki balanced top-down with bottom-up governance approaches. In these cities, governments are the most active actors in the smart cities’ ecosystems. However, they do not centralize the processes, but rather promote participation and collaboration. They offer a strategic framework to direct actions toward shared goals and promote bottom-up processes. Strategies include different application domains across cities[

25].

All the cities adopt a holistic vision of smart cities, considering them as socio-technical systems. They have similar smart city approaches to their smart cities’ strategies. These strategies give similar importance to technology implementation, the design of a strategic framework and the development of collaboration. The idea is to ensure smart cities’ development through the creation of a strategic framework that directs actions and ensures perennation, as well as a participative and collaborative environment of co-creation of innovative initiatives[

25].

In theses cities, public actors play an active role with regards to negotiation, governance, and coordination of the strategies. Majors (Barcelona), public officials (Vienna and Amsterdam) and councillors (Turin) lead the processes. Negotiations and involvement of stakeholders are facilitated by political and administrative commitments. The definition and implementation of strategies are supported by the collaboration of business, research, and civil society that mostly participate in the strategy design through Public and Private Partnerships; Public, Private and People Partnerships; and urban living labs[

26].

Business, research, and civil society participate in governance processes in particular projects through advisory committees and direct participation in governing institutions[

26]. However, participation in the process varies across actors, with a lower participation of civil society and citizens. Thus, smart city programs mainly emerge from a triple-helix model of collaboration through the interaction between governments, industries, and research. Civil society and citizens are little represented[

25].

In the Australian cities, despite smart city develops from government strategies, these strategies focus on public-private partnerships and promote citizens’ participation. The strategies support project development for problem-solving. In the case of Newcastle, the government implemented a process of extensive citizens’ consultation that oriented the strategy. Processes of community collaboration, co-creation, and co-design were also supported by the government. These processes helped in identifying local community needs and orient policies toward the construction of smart and innovative economies based on the consultation process. Partnerships between universities, technology companies and civil society are prioritized for funding by the government[

12].

3.3.5.3. Bottom-up Examples: The Triangulum (Manchester, Eindhoven, and Stavanger)

The example of Triangulum reflects a bottom-up approach that implements the concept of urban living labs by conceptualizing the city as a set of module projects that are expected to create impacts at the project level. The projects are evaluated through common processes by stakeholders who link successful solutions with indicators and metrics[

28]. Unlike other EU smart city projects, Triangulum does not stand from a policy agenda or strategy of smart city building. Consortium members are developing 5 smart urban districts regarded as spaces to build certain visions through collaborative co-creation of smart sustainable solutions. Entrepreneurial forms of governance are supported across districts, seeking sustainable forms of growth and competitivity as well as a reputation as innovative places to live. All districts have adopted practices of data governance and a quadruple-helix approach of collaboration between governments, the private sector, citizens, and universities. In this context, private companies develop smart technologies through collaborations with infrastructure owners such as housing associations, owners of homes, governments, and universities[

28].

The governance approach of Triangulum is based on the principles of co-creation of smart cities with citizens; involvement of stakeholders in the development of solutions; the role of initiatives in understanding smart cities contexts; the adoption of an assessment and evaluation approach at the project and district scales, seeking to evaluate the impacts of interventions’ goals; and the consideration of issues relative to sustainability and governance. The evaluation and monitoring of impacts is leaded by the University of Manchester, in collaboration with governments and other universities. The collaborative approach aims to support stakeholders’ capacities and needs and aims at creating sustainable infrastructure and urban development through governance and data creation. Open data helps partners and users to create value from data. Data development in the projects is based on a bottom-up approach. Stakeholders, who are also learning partners, participate in all the process, including the construction of the strategy, the goals, impacts and metrics[

28].

3.3.6. Smart City Coordination Offices

Smart city coordination centres can take the form of offices of decision-making and coordination inside or outside governments administrations and committees. In Amsterdam, Barcelona, Vienna, and Helsinki, governance approaches are influenced by previous experiences of collaboration. Cities, however, must innovate, cooperate, and change governance processes. This includes enhancing flexibility, inventing new ways of including partners, and creating a single centre of decision-making and coordination between departments (the Board in Amsterdam and Habitat urba in Barcelona). In Turin, there has been a politico-administrative integration through the creation of the Torino Smart City Foundation. In Vienna, committees make collaborate departments with stakeholders. The implementation of projects is done through the creation of the SCWA. The structure of administration in Turin, and Amsterdam is outside the municipality, while Vienna, and Barcelona created new administrative departments [

26].

In Berlin, a cross-departmental unit was created within the municipality that organizes meetings and workshops on urban sharing. In London, regulation is enforced at a city level, while Berlin experiences a fragmented enforcement. Berlin has adopted a more restrictive attitude than London that has established channels of communication with urban sharing organizations [

30].

In Australia, the Federal Government launched the Smart Cities Plan in 2016 and provided funding through city deals. However, there are differences across local governments. In Newcastle, the 2017 Smart City Strategy is preceded by two successful projects. The Newcastle city council is important in the development and coordination of the strategy. It also established a smart city officer. Partnerships with the industry and stakeholders are important in the success of the strategy. After a promotion of smart projects by different government departments, the Future City Unit in Parramatta was created in 2016: a small unit of project officers and strategic planners that supports different government’s projects in different departments. It also enhanced government’s capabilities of data and technology usage for decision making [

12].

4. Discussion

This section compares the cities’ objectives, governance forms, advancements and limits and discusses the results. It also provides a framework for smart cities based on lessons-learned from the analysis of the cities’ examples.

Table 2 presents the cities’ objectives, governance forms, advancements, and limitations.

Table 2 Comparing goals, governance forms, advancements, and limitations across cities

With regards with top-down forms of governance, the table shows that this type of governance can favour corporate-centric developments of smart cities that focus on infrastructure effectiveness and economic development with little consideration of sustainability issues as in the city of Seoul. In this city, despite collaboration with the private sector, this collaboration takes place mainly with large corporations. There is lack of support to start-ups and middle companies. There is insufficient citizens’ participation and infrastructure investment, as well as problems of service integration. In London and Berlin that also focus on economic development, infrastructure effectiveness and innovation, there is also insufficient stakeholder’s participation, and the support is restricted to large organizations. There are better communication channels in London than in Berlin and municipal governments have done some efforts to organize hackathons and workshops. In both cities, there are problems relative to unclear regulation and the problems mentioned above are related to the contextual factor of a fragmented government structure and fragmented enforcement at the city level. The city of Dubai shows, however, that a top-down form of governance could favour cross-department coordination, which in turn could favour technology development, data sharing and integration, and monitoring. This city also shows that the vision of the strategy can help promoting citizens’ participation, as well as processes of co-creation and collaboration with the private sector by the government. Sustainability issues are also included in the strategy and promoted, but the sustainability goal is little attainable in the urban and economic context of Dubai.

The hybrid and bottom-up examples are oriented toward an integration of economic development with sustainability as well as the development of innovation. In the hybrid examples of Amsterdam, Turin, Barcelona, and Vienna holistic approaches to smart city building were adopted with the advantages of combining strategic planning and government leadership with processes of co-creation and innovation with the main collaboration of industries and universities. However, civil society and citizens’ participation is limited and there are divergent interests. Thus, there is a need to transit from a triple-helix to a quadruple-helix collaboration model that involves citizens. This is added to problems of technology and data integration and to regulation restrictions. However, the Australian cities that adopted a hybrid approach that also promoted processes of co-creation and innovation included a process of citizens’ consultation prior to the formulation of the strategy, and promoted public-private partnerships and citizens’ participation. This shows, like the top-down example of Dubai, how governments can promote citizens’ participation. In the Australian cities, the avoidance of a corporate-centric approach by the government is related to a strong opposition by local actors to corporations’ control. The main limit in these cities is the fragmented government and geographical structure that generates regulatory and integration challenges.

The bottom-up examples of Eindhoven, Manchester and Stavanger that integrated sustainability with infrastructure and economic development have the advantage to involve citizens in collaboration processes. This includes processes of co-creation involving living-labs as well as module projects that respond to stakeholders’ needs. This enables technology development and data creation as well as project monitoring by stakeholders who participate in all the projects’ phases. Unlike hybrid examples, there is no strategic planning by governments. There are also technical problems of data quality, integration, access, collection, and so on. The lack of a government’s strategy and leadership, however, makes their role unclear. Thus, we wonder if the unclear government’s participation fits with the idea of a quadruple-helix collaboration model that theoretically promotes equal and horizontal interactions between governments, universities, the industry, and citizens. An hypothesis to be further demonstrated by future research is that the bottom-up approach is better represented by a triple-helix model of collaboration between stakeholders, including citizens, technology companies and universities, with little participation of governments.

We recommend this framework for smart cities based on lessons learned from the cases:

− To generate public value from data, municipal governments can define their goals by considering both the social, economic, cultural, and ecological contexts of their cities and the institutional, socio-economic, human, and technological capacities.

− The goals can focus on different issues such as improving the quality of services for citizens and citizens’ quality of life, promoting trust on the institutions, government and administration effectiveness, enhancing environmental quality and sustainability, fostering economic development, public transport, or culture, a better infrastructure effectiveness, enhancing the efficiency of buildings, and promoting innovation.

− Attention must be paid to infrastructure investment and maintenance and to the promotion of regulatory adaptation to overcome regulatory barriers.

− The consideration of smart cities within an holistic approach as socio-technical systems enables to focus not only on the technological elements of these constructions but also on the integration of technologies with governance processes.

− Governments must play a leading role in defining common goals, promoting trust, collaboration, and a common vision of smart cities across networks and mobilising stakeholders.

− The best governance arrangements are those in which governments leader the formulation and implementation of smart city strategies to promote stakeholders’ participation and enhance urban networks by making participate universities, the industry, civil society, and citizens. These actors can participate in the design and implementation of the strategies. The establishment of partnerships is an important instrument to promote collaboration. The government act as a coordinator of smart networks of collaboration through the creation a smart city coordination office.

− The legitimacy of smart cities will depend on government’s ability to make participate citizens while generating public value for them. Citizens’ consultations about the strategies are mechanisms of citizens’ participation.

− Governments should avoid creating corporate-centric forms of governance. This includes strategies to support start ups as well as promoting sustainability. Urban living-labs are useful to develop sustainable projects in which data enables a permanent evaluation by stakeholders. Data governance and quadruple-helix models of collaboration can be promoted by the projects to co-create smart technologies and co-create both local sustainability, innovation, and economic development, thus enhancing stakeholders’ capacities. However, these projects must be promoted at the city level to have a real environmental impact.

− A division of work and responsibilities for the smart city development between the government’s agencies according to their expertise can be useful to implement smart cities strategies, while also promoting private initiatives. Cross-department integration also favours technology development at a systems’ level, data sharing and data integration.

− Governments could also promote adaptive regulation to avoid legal barriers as well as multi-level technologies of data sharing for urban sharing.

5. Conclusions

In the analyzed examples, governance is a central element of smart cities building. The cities adopted holistic approaches integrating technology development with governance processes. Beyond the governance model in which governments promote collaboration [

24] by leading processes of policy formulation, implementation, and regulation to create public value [

10,

11], the examples show that cities have invented different structures of smart cities’ governance. There are differences within the forms that top-down, hybrid and bottom-up approaches can adopt. Top-down forms can be corporate-centric (see [

25]) or promote citizens’ participation. Differences not only depend on the visions, goals, and strategies of the smart cities, but also on contextual factors such as government structures, previous institutional arrangements, and the technological and economic contexts of each city. Top-down forms of governance are moving toward more participative ones and the corporate-centric approach is increasingly regarded as something that erodes smart cities’ legitimacy. The acknowledgement of the need of civil society and citizens’ participation is driving the processes toward the creation of public value and sustainability. The Triangulum example shows the possibility of developing bottom-up approaches without government’s leadership and strategies. However, government leadership can have many advantages such as better alignment and coordination, promoting participation of stakeholders and citizens, funding opportunities and technology and data integration.

Through a rapid review of theoretical and empirical articles on smart-city governance, this paper has contributed to the literature on smart city governance and sustainability by proposing a theoretical framework that can be used by cities to define their governance models, as well as an analysis and comparison of the different models adopted by different cities. The analysis shows that the cities that implemented top-down models were oriented toward economic development, infrastructure effectiveness and innovation, giving less attention to sustainability issues. These cities privileged collaboration with technology corporations, gave poor support to start-ups and tended to not promote enough citizens’ involvement. However, top-down forms of governance can include this goal in their visions and strategies and use government’s institutional and funding capacities to make citizens participate. Hybrid forms of governance are more oriented toward sustainability goals and promote public-private partnerships and processes of co-creation and innovation through government leadership and smart city strategies implementation. However, in most of the cities more civil society and citizens’ participation was required. Hybrid examples tend to promote triple-helix collaboration and should move toward a quadruple-helix collaboration model. The quadruple-helix model was adopted by the cities with bottom-up approaches. In those cities, stakeholders participated in all the projects’ phases. However, these cities had problems related to data integration.

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, GMR. and MCT; methodology, GMR, and JP; software, JP; validation, MCT and JP.; formal analysis, GMR; investigation, GMR, and JP; resources, MCT.; data curation, JP; writing—original draft preparation, GMR; writing—review and editing, MCT, and JP; visualization, GMR; supervision, MCT; project administration, JP.; funding acquisition, MCT. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.” Please turn to the CRediT taxonomy for the term explanation. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

Funding

“This research received no external funding”

Institutional Review Board Statement

“Not applicable”.

Informed Consent Statement

“Not applicable.”

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Leszczynski, A. Speculative futures : Cities, data, and governance beyond smart urbanism. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 2016, 48, 1691–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israilidis, J. , Odusanya, K., & Mazhar, M. (2019). Knowledge management in smart city development : A systematic review.

- Artyushina, A. Is civic data governance the key to democratic smart cities ? The role of the urban data trust in Sidewalk Toronto. Telematics and Informatics 2020, 55, 101456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acuto, M. , Parnell, S., & Seto, K. C. Building a global urban science. Nature Sustainability 2018, 1, 2–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smedby, N. , & Neij, L. Experiences in urban governance for sustainability : The Constructive Dialogue in Swedish municipalities. Journal of Cleaner Production 2013, 50, 148–158. [Google Scholar]

- Washbourne, C.-L. , Culwick, C., Acuto, M., Blackstock, J. J., & Moore, R. Mobilising knowledge for urban governance : The case of the Gauteng City-region observatory. Urban Research & Practice 2021, 14, 27–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yigitcanlar, T. , Kamruzzaman, M., Foth, M., Sabatini-Marques, J., Costa, E. da, & Ioppolo, G. Can cities become smart without being sustainable ? A systematic review of the literature. Sustainable Cities and Society 2019, 45, 348–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, H. , Singh, M. K., Gupta, M., & Madaan, J. Moving towards smart cities : Solutions that lead to the Smart City Transformation Framework. Technological forecasting and social change 2020, 153, 119281. [Google Scholar]

- Acuto, M. , Steenmans, K., Iwaszuk, E., & Ortega-Garza, L. Informing urban governance ? Boundary-spanning organisations and the ecosystem of urban data. Area 2019, 51, 94–103. [Google Scholar]

- Dameri, R. P. Searching for smart city definition : A comprehensive proposal. International Journal of computers & technology 2013, 11, 2544–2551. [Google Scholar]

- Meijer, A. Datapolis : A public governance perspective on “smart cities”. Perspectives on Public Management and Governance 2018, 1, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadowski, J. , & Maalsen, S. Modes of making smart cities : Or, practices of variegated smart urbanism. Telematics and Informatics 2020, 55, 101449. [Google Scholar]

- Ruhlandt, R. W. S. The governance of smart cities : A systematic literature review. Cities 2018, 81, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, H. H. , Malik, M. N., Zafar, R., Goni, F. A., Chofreh, A. G., Klemeš, J. J., & Alotaibi, Y. Challenges for sustainable smart city development : A conceptual framework. Sustainable Development 2020, 28, 1507–1518. [Google Scholar]

- Hashem, I. A. T. , Chang, V., Anuar, N. B., Adewole, K., Yaqoob, I., Gani, A., Ahmed, E., & Chiroma, H. The role of big data in smart city. International Journal of information management 2016, 36, 748–758. [Google Scholar]

- Kandt, J. , & Batty, M. Smart cities, big data and urban policy : Towards urban analytics for the long run. Cities 2021, 109, 102992. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, C. , Kim, K.-J., & Maglio, P. P. Smart cities with big data : Reference models, challenges, and considerations. Cities 2018, 82, 86–99. [Google Scholar]

- Giest, S. Big data analytics for mitigating carbon emissions in smart cities : Opportunities and challenges. European Planning Studies 2017, 25, 941–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranchordás, S. , & Klop, A. (2018). Data-driven regulation and governance in smart cities. In Research Handbook in Data Science and Law. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Tan, S. Y. , & Taeihagh, A. Smart city governance in developing countries : A systematic literature review. sustainability 2020, 12, 899. [Google Scholar]

- Meijer, A. , & Bolívar, M. P. R. Governing the smart city : A review of the literature on smart urban governance. International review of administrative sciences 2016, 82, 392–408. [Google Scholar]

- Yahia, N. B. , Eljaoued, W., Saoud, N. B. B., & Colomo-Palacios, R. Towards sustainable collaborative networks for smart cities co-governance. International journal of information management 2021, 56, 102037. [Google Scholar]

- Chourabi, H. , Nam, T., Walker, S., Gil-Garcia, J. R., Mellouli, S., Nahon, K., Pardo, T. A., & Scholl, H. J. (2012). Understanding Smart Cities : An Integrative Framework. 2012 45th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, 2289–2297. [CrossRef]

- Bolívar, M. P. R. (2016). Characterizing the role of governments in smart cities : A literature review. Smarter as the new urban agenda, 49–71.

- Mora, L. , Deakin, M., & Reid, A. Strategic principles for smart city development : A multiple case study analysis of European best practices. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 2019, 142, 70–97. [Google Scholar]

- Nesti, G. Defining and assessing the transformational nature of smart city governance : Insights from four European cases. International Review of Administrative Sciences 2020, 86, 20–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. H. , Hancock, M. G., & Hu, M.-C. Towards an effective framework for building smart cities : Lessons from Seoul and San Francisco. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 2014, 89, 80–99. [Google Scholar]

- Paskaleva, K. , Evans, J., Martin, C., Linjordet, T., Yang, D., & Karvonen, A. Data governance in the sustainable smart city. 2017, 4, 41. [Google Scholar]

- Noori, N. , de Jong, M., Janssen, M., Schraven, D., & Hoppe, T. Input-output modeling for smart city development. Journal of Urban Technology 2021, 28, 71–92. [Google Scholar]

- Zvolska, L. , Lehner, M., Voytenko Palgan, Y., Mont, O., & Plepys, A. Urban sharing in smart cities : The cases of Berlin and London. Local Environment 2019, 24, 628–645. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).