Introduction

1.1.1. Hepatitis B virus

1.1.1.1. Classification

The hepatitis B virus belongs to the Orthohepadnavirus genus, along with eleven other species. The Hepadnaviridae family, which also includes the four other genera Avihepadnavirus, Herpetohepadnavirus, Metahepadnavirus, and Parahepadnavirus, is where the genus is categorized. The sole member of the viral order Blubervirales is this family of viruses. All apes, including chimpanzees, gorillas, orangutans, and Old World monkeys, have been reported to carry viruses resembling hepatitis B (Dupinay et al., 2017). ... in woolly monkeys found in the New World (the woolly monkey hepatitis B virus), pointing to the virus’s prehistoric primate origin. There are ten subgenotypes of genotype D (Hundie et al., 2017).

1.1.1.2. Morphology

A. Structure

The hepadnavirus family includes the hepatitis B virus. The viral particle, also known as a virion or Dane particle (WHO, 2015), is made up of an icosahedral nucleocapsid core made of protein and an outer lipid envelope. The viral DNA and a DNA polymerase with reverse transcriptase activity akin to that of retroviruses are enclosed in a nucleocapsid (Locarnini, 2004).

B. Components

It consists of:

HBsAg, or hepatitis B surface antigen was the first known hepatitis B virus protein (Jaroszewicz et al., 2010).

HBcAg (Hepatitis B core antigen) The primary structural protein of the HBV icosahedral nucleocapsid and is involved in the virus’s reproduction (Lin et al., 2012).

HBeAg (Hepatitis B envelope antigen) is secreted and builds up in serum. The same reading frame is used to create both HBcAg and HBeAg (TSRI, 2009).

HBx is tiny. is nonstructural, 154 amino acids long, and plays a significant part in HBV replication in HepG2 cells as well as liver illness linked to HBV (Tang et al. 2006).

C.Size

Although the circular DNA that makes up the HBV genome is uncommon, it is not completely double-stranded. The viral DNA polymerase is connected to one end of the whole strand. According to Kay and Zoulim (2007), the genome has a length of 3020–3320 nucleotides for the full length strand and 1700–2800 nucleotides for the short length strand.

1.1.1.3. Epidemiology

As of 2017, at least 391 million individuals, or 5% of the global population, were chronically infected with HBV. However, same year there were an additional 145 million instances of acute HBV infection (GBD, 2017). According to WHO (2020), regional prevalences vary from approximately 6% in Africa to 0.7% in the Americas.

The disease primarily spreads among youngsters in regions with moderate frequency, such as Eastern Europe, Russia, and Japan, where 2–7% of the population has a chronic infection. Transmission during birthing is more likely in high-prevalence areas like China and South East Asia, but it can also occur during childhood in other high-endemicity areas like Africa (Alter, 2003).

According to Komas et al. (2013), the prevalence of chronic HBV infection is at least 8% in high endemicity areas and between 10% and 15% in Africa and the Far East. China has 120 million infected persons as of 2010, followed by 40 million in India and 12 million in Indonesia. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that the virus claims the lives of 600,000 people annually. About 19,000 new cases were reported in the US in 2011, a nearly 90% decrease from 1990 (Schillie et al., 2013).

1.1.1.4. Transmission

Hepatitis B virus transmission occurs when an individual comes into contact with infected blood or bodily fluids that contain blood. Comparatively speaking, it is 50–100 times more contagious than the HIV virus (CDC, 2015). Sexual interaction is one way that information can spread (Fairley and Read, 2012). Reusing contaminated needles and syringes, transfusions of blood, transfusions with other human blood products, and vertical transmission from mother to child after childbirth (Buddeberg et al., 2008).

A mother who tests positive for HBsAg at birth has a 20% chance of infecting her child if treatment is not received. In the event that the mother also tests positive for HBeAg, this risk might reach 90%. Within households, family members may contract HBV from one another by coming into touch with saliva or secretions that contain the virus on non-intact skin or mucous membranes (IDEAS, 2009).

1.1.1.5. Diseases

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) continues to be a global health concern even with a vaccine to prevent it. The hepatitis B virus (HBV) is the infectious agent that causes hepatitis B, a liver-damaging illness (WHO, 2014). Acute hepatitis B can develop into chronic hepatitis B, which can cause many illnesses and ailments (Hu et al., 2019).

1.1.1.6. Signs and symptoms

Acute viral hepatitis, which starts with generalized malaise, lack of appetite, nausea, vomiting, body aches, low fever, and dark urine and develops into jaundice, is linked to acute hepatitis B virus infection. For those affected, the disease lasts a few weeks before progressively getting better (Terrault et al., 2005).

Hepatitis B virus infection can be chronic and asymptomatic, or it can be linked to a persistent liver inflammation that progresses over years to cirrhosis. An infection of this kind significantly raises the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC; liver cancer). About half of hepatocellular carcinoma cases in Europe are related to hepatitis B and C (El-Serag, 2011).

1.1.1.7. Diagnosis

Hepatitis B virus antigens and antibodies that can be found in an individual’s blood after an acute infection or in an individual who has been infected for a long time. Assays, or tests for the identification of hepatitis B virus infection, are blood or serum tests that look for antibodies made by the host or viral antigens. These assays have complicated interpretations (Bonino et al., 1987).

The most common test for this illness is the hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg). It is the initial detectable antigen produced by the virus following infection. But this antigen might not be present in the early stages of an infection, and it might not be noticeable in the latter stages when the host is eliminating it. The 180 or 240 copies of the core protein, also referred to as the hepatitis B core antigen, or HBcAg, make up the icosahedral core particle. Serological evidence of disease may only be IgM antibodies specific to the hepatitis B core antigen during this “window” in which the host is still infected but is effectively clearing the virus. Consequently, total anti-HBc and HBsAg are present in the majority of hepatitis B diagnostic panels (Karayiannis et al., 2009).

Hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) is a second antigen that appears shortly after HBsAg does. Hepatitis B virus genotypes that do not express the ‘e’ antigen challenge the conventional wisdom that increased rates of viral replication and enhanced infectivity are linked to the presence of HBeAg in a host’s serum (Liaw et al., 2010).

IgG antibodies to the hepatitis B surface antigen and core antigen (anti-HBs and anti-HBc IgG) will eventually overtake the HBsAg if the host is successful in eliminating the infection. The window period is the interval of time between the elimination of HBsAg and the emergence of anti-HBs. A person who tests positive for anti-HBs but negative for HBsAg has likely had a prior vaccination or recovered from an illness (Liaw et al., 2010).

Hepatitis B carriers are those who test positive for HBsAg for at least six months (Lok and McMahon, 2007). If virus carriers are in the immunological clearance phase of a chronic infection, they may have chronic hepatitis B, which would be indicated by high serum alanine aminotransferase levels and liver inflammation. Due to their low viral multiplication, carriers who have seroconverted to HBeAg negative status—especially those who contracted the infection as adults—may be less likely to experience long-term consequences or to infect others (Chu and Liaw, 2007). To identify and quantify the quantity of HBV DNA, often known as the viral load, in clinical specimens, PCR techniques have been developed. These examinations determine an individual’s infection status and track the effectiveness of treatment (Zoulim, 2006).

1.1.1.8. Prevention

Since 1991, the United States has consistently recommended vaccinations for babies to avoid hepatitis B (Schillie et al., 2013). It is usually advised to take the first dosage the day after birth. According to Chan et al. (2016), the hepatitis B vaccine was the first to be able to prevent cancer in general and liver cancer in particular.

In addition, the vaccine with hepatitis B immunoglobulin combo is better than the vaccine alone (Lee et al., 2006). In 86% to 99% of cases, this combination stops HBV transmission around the time of birth (Wong et al., 2014).

1.1.1.9. Treatment

Most persons who have an acute hepatitis B infection recover on their own without the need for treatment (CDC, 2017). Less than 1% of individuals with immunocompromised individuals or those whose infection progresses aggressively to fullminant hepatitis may need early antiviral treatment (Lai and Yuen, 2007).

Treatment duration varies based on medicine and genetics, ranging from six months to a year. However, the length of treatment varies greatly and is typically more than a year when medication is administered orally (Terrault et al., 2016).

As of 2018, the United States had eight approved medicines available to treat hepatitis B infection. They include two immune system modulators, PEGylated interferon alpha-2a and interferon alpha-2a, as well as antiviral drugs, such as entecavir, lamivudine, adefovir, tenofovir disoproxil, tenofovir alafenamide, telbivudine, and more. The World Health Organization suggested entecavir or tenofovir as first-line treatments in 2015. The majority of people who have cirrhosis now require therapy (WHO, 2015).

Long-acting PEGylated interferon, which is injected just once per week, has replaced the use of interferon (Dienstag, 2008). The therapy lowers the quantity of virus particles detected in the blood, or the viral load, by inhibiting viral replication in the liver (Pramoolsinsup, 2002).

1.2.2. Hepatitis C virus

1.2.2.1. Virology

According to Rosen (2011), the hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a tiny, enclosed, single-stranded, positive-sense RNA virus. According to Ray et al. (2009), it belongs to the family Flaviviridae and the genus Hepacivirus. HCV has seven main genotypes, referred to as genotypes one through seven (Nakano et al., 202 1). According to Wilkins et al. (2010), genotype 1 accounts for roughly 70% of cases in the US, genotype 2 for 20%, and each of the remaining genotypes for 1% of cases.

In Europe and South America, genotype 1 is likewise the most prevalent (Rosen, 2011). The virus particles in the serum have a half-life of roughly three hours, although they could be as brief as forty-five minutes (Lerat and Hollinger 2004; Pockros, 2011). Every day, an infected individual produces roughly 1012 virus particles (Lerat Hollinger, 2004).

1.2.2.2. Transmission

Most infections are often caused by percutaneous contact with contaminated blood; however, the mode of transmission is highly dependent on the location and economic standing of a nation (Hagan and Schinazi, 2013). In fact, injectable drug usage is the main means of transmission in the industrialized world, whereas risky medical procedures and blood transfusions are the main means in the developing world (Maheshwari and Thuluvath, 2010). In 20% of cases, the cause of transmission is still uncertain (Pondé, 2011).

A. Drug use

In many regions of the world, injection drug use (IDU) is a significant risk factor for hepatitis C. Out of the 77 countries that were examined, it was shown that between 60% and 80% of injectable drug users in 25 of them, including the US, had hepatitis C. More than 80% of the countries had these rates (Nelson et al., 2011).

Ten million intravenous drug users are thought to be hepatitis C positive; the largest absolute totals are found in China (1.6 million), the US (1.5 million), and Russia (1.3 million) (Nelson et al., 2011). Inmates in American prisons have a hepatitis C prevalence that is 10–20 times higher than that of the general population (Imperial, 2010).

B. Healthcare exposure

Significant infection risks are associated with blood transfusions, blood product transfusions, and organ donations that do not undergo HCV screening (Wilkins et al., 2010). 1992 saw the implementation of universal screening in the US (Marx, 2010). and in 1990, Canada implemented nationwide screening (Day et al., 2009).

As a result, the risk per unit of blood dropped from one in 200 (Marx, 2010) to one in 10,000–1,000,000 (Pondé, 2010). This minimal risk persists because, depending on the technique, it can take anywhere from 11 to 70 days for the blood to test positive for hepatitis C after the potential blood donor has the disease (Pondé, 2010).

According to Wilkins et al. (2010), there is a 1.8% risk that someone who was needlestick injured by an HCV positive person will go on to get the illness. If the puncture incision is deep and the needle in question is hollow, the danger is higher (Alter, 2007).

C. Sexual intercourse

Hepatitis C is not often spread through sexual contact. Very minimal risks have been observed in studies looking at the possibility of HCV transmission between heterosexual partners when one is infected and the other is not (Kim, 2016).

D. Bodymodification

Hepatitis C risk is elevated by two to three times in those who have tattoos. This may be the result of contaminated dyes or inadequately sanitized equipment (Jafari et al., 2010). According to the CDC (2012), tattoos received in a licensed establishment are rarely directly linked to HCV infection.

E. Sharedpersonalitems

Razors, toothbrushes, and tools for manicures and pedicures are examples of personal hygiene products that can get contaminated with blood. Sharing these kinds of things may expose someone to HCV. Hugging, kissing, or sharing cutlery while cooking are not examples of informal contact that can transmit HCV (CDC, 2012). additionally, it cannot be spread via food or drink (Wong and Lee, 2006).

F. Mother-to-child transmission

Less than 10% of pregnancies result in hepatitis C transmission from mother to kid. This risk cannot be changed by any means (Lam et al., 2010). Although the exact time of transmission during pregnancy is unknown, it may happen at either the gestational or delivery stages (Pondé, 2010). There is a higher chance of transmission during a prolonged labor (Alter, 2007).

1.2.2.3. Epidemiology

In a 2021 report, the World Health Organization estimated that, as of 2019, 58 million persons worldwide had chronic hepatitis C (WHO, 2021). An estimated 290,000 people die each year from hepatitis C-related illnesses, primarily cirrhosis and liver cancer, and an estimated 1.5 million people become infected each year (WHO, 2022).

Consequently, the global chronic patient population under treatment increased from approximately 950,000 in 2015 to 9.4 million in 2019. Hepatitis C mortality decreased from approximately 400,000 to 290,000 during the time (WHO 2015; WHO, 2021).

A previous study conducted in 2013 found that infection rates were low (<1.5%) in Asia-Pacific, Tropical Latin America, and North America, and high (>3.5% population infected) in Central and East Asia, North Africa, and the Middle East; intermediate (1.5–3.5%) in South and Southeast Asia, sub-Saharan Africa, Andean, Central and Southern Latin America, Caribbean, Oceania, Australasia, and Central, Eastern, and Western Europe.

The probability of cirrhosis among chronically infected individuals after 20 years is estimated to be approximately 10-15% for men and 1-2%) for women, however it varies according on the study. It’s unknown why there is this difference. Hepatocellular carcinoma can develop at a rate of 1-4 percent annually if cirrhosis is established (Yu and Chuang, 2009). Egypt achieved a significant reduction in Hepatitis C infection rates from 22% in 2011 to just 2% in 2021 by implementing Egypt’s 2030 Vision (Egypt Today, 2021).

About 2% of Americans suffer from chronic hepatitis C (Wilkins et al., 2010). According to estimates, there were 30,500 new cases of acute hepatitis C in 2014 (0.7 cases per 100,000 people), up between 2010 and 2012. (CDC, 2016). In 2008, there were 15,800 hepatitis C-related fatalities (CDC, 2014). surpassing HIV/AIDS as the leading cause of death in the United States in 2007. (Nrw York Time, 2012). According to estimates, between 0.13 and 3.26% of people in Europe suffer from chronic infections (Blachier et al., 2013).

According to Hepatitis C, 2017, around 118,000 individuals in the UK had a chronic infection in 2019. There are more cases of this virus overall in a few Asian and African nations (Holmberg et al., 2011). Pakistan (4.8%) and China (3.2%) are two nations with exceptionally high infection rates (WHO, 2011).

Since 2014, most people can eradicate the condition in 8–12 weeks with the use of incredibly powerful medication. Overall, the number of HCV cases increased in 2015, with around 950,000 new infections and 1.7 million treatment cases (Lombardi and Mondelli, 2019).

A. HCV in children and pregnancy

Global estimates place the prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in infants and pregnant women at 0.05–5% and 1-8%, respectively (Arshad et al., 2011). An estimated 3–5% of cases are vertically transmitted, and children have a high probability of spontaneous clearance (25–50%). Higher rates of occurrence in children (15%) as well as vertical transmission (18%, 6–36%, and 41%) have been documented (Fischler, 2007).

HCV infection is now most commonly caused via transmission around the time of birth in affluent countries. Transmission appears to be uncommon when there is no virus in the mother’s blood (Thomas et al., 1998). According to Indolfi and Resti (2009), procedures that expose the newborn to maternal blood and membrane rupture occurring more than six hours prior to birth are factors linked to an elevated likelihood of infection.

1.2.2.4. Signs and symptoms

Hepatitis C can take two weeks to six months to incubate. After the initial infection, almost 80% of individuals show no symptoms at all. When symptoms are severe, a person may have fever, lethargy, nausea, vomiting, abdominal discomfort, pale stools, dark urine, joint pain, and jaundice (yellowing of the skin and whites of the eyes). About 20–30% of infected individuals experience acute symptoms (WHO, 2016; CDC, 2020).

1.2.2.5. Diagnosis

Hepatitis C can be diagnosed using many methods such as quantitative HCV RNA polymerase chain reaction (PCR), recombinant immunoblot assay, and HCV antibody enzyme immunoassay (ELISA) (Wilkins et al., 2010). While antibodies can take a significant amount longer to develop and become detectable, HCV RNA can usually be found by PCR one to two weeks after infection (Ozaras and Tahan, 2009).

Patients with acute illnesses typically come with mild, nonspecific flu-like symptoms, making diagnosis difficult. In contrast, the transition from acute to chronic illness is often sub-clinical (Westbrook and Dusheiko, 2014). According to Kanwal and Bacon (2011), chronic hepatitis C is defined as a viral infection that lasts longer than six months and is detected by the presence of its RNA.

A. Serology

The first step in the testing process for hepatitis C usually involves blood work to look for HCV antibodies using an enzyme immunoassay. In the event that this test yields positive results, an additional test is run to confirm the immunoassay results and ascertain the viral load. HCV RNA polymerase chain reaction is employed to measure the viral load, and recombinant immunoblot assay is utilized to validate the immunoassay (Wilkins et al., 2010). Although there are hazards associated with the process, liver biopsies are utilized to assess the level of liver damage that is present (Rosen, 2011).

1.2.2.6. Prevention

As of 2016 (Abdelwahab and Said, 2018), there is no vaccination that is authorized to prevent getting hepatitis C. The risk of hepatitis C in injecting drug users is reduced by around 75% when harm reduction tactics, such as providing fresh needles and syringes and treating substance abuse, are combined (Hagan et al., 2011). Both blood donor screening and following standard operating procedures in medical facilities are critical on a nationwide scale (Ray and Thomas, 2009).

1.2.2.7. Treatment

Alcohol and liver-toxic drugs should be avoided by those with chronic hepatitis C (Wilkins et al., 2010). Given the higher risk of infection if they also have hepatitis A and hepatitis B, they should also receive vaccinations against those diseases (Wilkins et al., 2010). At lower dosages, acetaminophen use is usually regarded as safe (Kim, 2016).

A. Medications

About 90% of chronic cases with ribavirin resolve with therapy (WHO, 2016). For those with confirmed chronic hepatitis C who do not have a significant risk of dying from other causes, antiviral drug treatment is advised (AASLD/IDSA, 2015). When given medicine, almost 90% of patients with persistent infections can be cured (CDC, 2019). Nevertheless, it may be costly to obtain these medicines (WHO, 2016).

For patients who have not responded to prior treatment with sofosbuvir or other NS5A inhibitors, a combination of sofosbuvir, velpatasvir, and voxilaprevir may be utilized. Treatments up until 2011 involved a 24- or 48-week course of pegylated interferon alpha and ribavirin, contingent on the genotype of the HCV (Wilkins et al., 2010).

Cure rates from this treatment range from 45 to 70% for genotypes 1 and 4, and from 70 to 80% for genotypes 2 and 3. Treatment works best while hepatitis C is in its acute stage, which lasts for six months, as opposed to when it has progressed into the chronic stage (Ozaras and Tahan, 2009). About 25% of those with chronic hepatitis B experience reactivation of hepatitis B after receiving therapy for hepatitis C (Mücke et al., 2018).

1.2.3. Hepatitis A virus

Hepatovirus A (HAV) is the infectious agent that causes hepatitis A, a form of viral hepatitis. Many cases, especially in the younger population, show few or no symptoms. For individuals who experience symptoms, the interval between infection and symptoms is two to six weeks (Connor, 2005; Matheny and Kingery, 2012).

When they do, symptoms including nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, jaundice, fever, and abdominal discomfort usually linger for eight weeks. Ten to fifteen percent of patients had a symptom recurrence within six months of the original illness. Rarely, acute liver failure can happen; older people are more likely to have this (Matheny and Kingery, 2012).

Typically, consuming food or drinking water tainted with diseased excrement spreads the infection. Shellfish that is uncooked or undercooked is a very common source. Additionally, it can spread through intimate contact with an infected individual. Even while children who are infected frequently show no symptoms, they can still spread the infection to others. A person is immune for the remainder of their lives following just one infection. Blood testing is necessary for the diagnosis because the symptoms can be mistaken for those of several different illnesses. Out of the five recognized hepatitis viruses, there are A, B, C, D, and E. Bellou and associates (2013); Matheny and Kingery, 2012).

As a preventative measure, the hepatitis A vaccine works well. Certain nations regularly advise against it for young people and others who are more vulnerable and have never received a vaccination. It seems to work for eternity. Proper meal preparation and hand cleaning are two other protective strategies. There isn’t a set course of therapy; rest and over-the-counter drugs for nausea or diarrhea are advised as needed. Most of the time, infections end fully and don’t cause persistent liver damage. Liver transplantation is the treatment of choice for acute liver failure, should it arise. (WHO, 2013; Irving et al., 2012; Matheny and Kingery, 2012).

Annually, there are around 114 million infections (including symptomatic and asymptomatic) and 1.4 million symptomatic cases worldwide. It is more prevalent in parts of the world where there is a shortage of clean water and inadequate sanitation. Ninety percent of children in underdeveloped countries are immune by maturity, having been infected by the age of ten. In moderately developed nations, when vaccination rates are low and children are not exposed at an early age, it frequently happens during outbreaks. 11,200 people died from acute hepatitis A in 2015. Every year on July 28, the world observes World Hepatitis Day to raise awareness of viral hepatitis (Matheny and Kingery, 2012; WHO, 2013).

1.2.3.1. Transmission

The fecal–oral pathway is how the virus spreads, and crowded, unsanitary environments are common places for infections to happen. Parenterally administered hepatitis A can seldom be contracted from blood or blood products. Food-borne illnesses frequently occur, and eating shellfish raised in contaminated water carries a significant risk of infection. HAV is responsible for about 40% of cases of acute viral hepatitis. Ten days after infection, or before symptoms appear, infected people are contagious. According to Murray et al. (2005), the virus is resistant to drying, detergent, acid (pH 1), solvents (such as ether and chloroform), and temperatures as high as 60 °C.

Both fresh and salt water can support it for several months. Epidemics from common sources (restaurants, water, etc.) are common. In developing nations, the prevalence of infection in children can exceed 100%; yet, once an infection occurs, a lifetime immunity develops. Drinking water treated with chlorine, formalin (0.35%, 37 °C, 72 hours), peracetic acid (2%, 4 hours), beta-propiolactone (0.25%, 1 hour), and UV light can all inactivate HAV. Sexual intercourse, particularly oroanal sexual behaviors, can also transmit HAV (Brundage and Fitzpatrick, 2006).

This virus is very contagious in underdeveloped nations and areas with low standards of hygiene, and the sickness is typically first discovered in early childhood. The frequency of HAV falls as wages grow and more people have access to clean water. However, in industrialized nations, young adults who are susceptible to infection are the main carriers of the virus. Most of these individuals become infected while traveling to nations where the illness is common or by coming into contact with infected individuals. The virus’s sole natural reservoir is humans. There are no known insect or animal vectors that can spread the virus. There have been no reports of a chronic HAV condition (Connor, 2005).

1.2.3.2. Epidemiology

About 1.4 million persons worldwide are thought to get symptomatic HAV infections each year. In total, there were about 114 million infections in 2015, both symptomatic and asymptomatic. 11,200 people died from acute hepatitis A in 2015. The amount of hepatovirus A in circulation is lower in developed nations than it is in underdeveloped nations. Since the majority of adults and adolescents in poor nations have already experienced the illness, they are immune. There is a chance that adults in middle-income nations will be exposed to diseases (Jacobsen and Wiersma, 2010; Matheny and Kingery, 2012).

In 1997, the US CDC received reports of almost 30,000 cases of hepatitis A; however, throughout the years, the number of cases reported every year has decreased to less than 2,000. The state of Kentucky experienced the largest-scale hepatitis A outbreak in US history in 2018. It is thought that the outbreak began in November 2017. As of July 2018, there had been at least one case of hepatitis A recorded in 48 percent of the state’s counties; there had been 969 suspected cases overall, with six fatalities (482 instances in Louisville, Kentucky). The outbreak peaked in July 2019 with 5,000 cases and 60 fatalities, but it thereafter tapered off to a few new cases per month (Wymer, 2019).

In late 2003, there was another large-scale outbreak in the US: the 2003 US hepatitis outbreak, which struck at least 640 persons in northeastern Ohio and southwest Pennsylvania (resulting in four fatalities). A Monaca, Pennsylvania restaurant’s poisoned green onions were identified as the cause of the outbreak (Wheeler et al., 2005).

After consuming clams from a tainted river in Shanghai, China, more than 300,000 people contracted HAV in 1988. A recall of frozen berries was issued in June 2013 after at least 158 persons—69 of whom required hospitalization—were infected with HAV after the US retailer Costco sold the product to over 240,000 consumers. A recall of Costco’s frozen berries was announced in April 2016, following at least 13 cases of HAV infection in Canada, three of which resulted in hospitalization. A recall of frozen berries was announced in Australia in February 2015 after the product was consumed by at least 19 persons who became ill. Hepatitis A outbreaks in 2017 were recorded in Utah, Michigan, and California (especially in the San Diego area), resulting in over 800 hospital admissions and 40 fatalities (Ramseth, 2017).

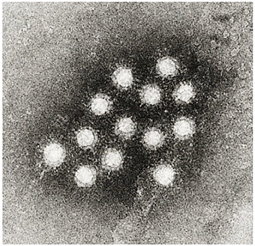

1.2.3.3. Structure

Hepatovirus A is a picornavirus, meaning it has a single strand of positive-sense RNA encased in a protein shell. It is not enclosed. The virus has been identified as having only one serotype, but several genotypes. The genome uses codons in a biased way that is unusually different from that of its host. Its internal ribosome entrance site is also not very good. Highly conserved clusters of uncommon codons limit antigenic diversity in the area encoding the HAV capsid (Aragonès et al., 2008).

| Genus |

Structure |

Symmetry |

Capsid |

Genomic arrangement |

Genomic segmentation |

| Hepatovirus |

Icosahedral |

Pseudo T=3 |

Nonenveloped |

Linear |

Monopartite |

1.2.3.4. Taxonomy

Hepatovirus A is a type of virus belonging to the genus Hepatovirus, family Picornaviridae, order Picornavirales. Natural hosts include vertebrates such as humans. There are nine known Hepatovirus members. Shrews, hedgehogs, rodents, and bats are all infected by this species. Hepatitis A may have originated in rodents, according to phylogenetic study (Anthony et al., 2015).

Electron micrograph of Hepatovirus A virions.

From a seal, a member virus of hepatovirus B, or Phopivirus, has been isolated. About 1800 years ago, this virus and Hepatovirus A had a common ancestor. The woodchuck Marmota himalayana has been found to harbor another hepatovirus, known as the Marmota himalayana hepatovirus. It suggests that approximately a millennium ago, this virus and the one that infects primates had an ancestor (Yu et al., 2016).

1.2.3.2.1. Genotypes

There has been a description of one serotype and seven distinct genetic groups (three simian and four human). I through III are the human genotype numbers. There are six known subtypes: IA, IB, IIA, IIB, IIIA, and IIIB. The genotypes of simian have been assigned numbers IV–VI. Additionally, a single human isolate of genotype VII has been reported. It has been possible to isolate humans and owl monkeys with genotype III. Most isolates from humans belong to genotype I. Subtype IA makes up the majority of type I isolates (Ching et al., 2002).

According to estimates, the genome experiences 1.73–9.76 × 10−4 nucleotide substitutions per site annually for each mutation. It seems that approximately 3600 years ago, the human strains separated from the simian strains. It has been estimated that the mean age of the IIIA and III genotype strains is 202 years and 592 years, respectively (Kulkarni et al., 2009).

1.2.3.5. Pathogenesis

The host immunological reaction to HAV results in hepatic damage. Human leukocyte antigen-restricted, HAV-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes and natural killer cells mediate hepatocellular damage and the elimination of infected hepatocytes; viral replication takes place in the cytoplasm of hepatocytes. It seems that interferon-gamma plays a major part in encouraging the removal of infected hepatocytes. Severe hepatitis is linked to an overreaction by the host, as evidenced by a significant decrease in HAV ribonucleic acid (RNA) in the bloodstream after acute infection (CDC, 2009).

1.2.3.6. Signs and symptoms

Early signs of hepatitis virus Although an infection can be mistaken for influenza, some individuals—particularly children—don’t show any symptoms at all. It usually takes 2-4 weeks (the incubation period) for symptoms to manifest following the initial infection. Ninety percent of kids do not exhibit any symptoms. For individuals who experience symptoms, the interval between infection and onset is typically 2–6 weeks, with an average of 28 days (Connor, 2005).

Age is a crucial factor in the likelihood of symptomatic infection; over 80% of adults have symptoms consistent with acute viral hepatitis, but most children have infections that are either silent or go undiagnosed. Although some patients may experience symptoms for up to six months, the majority of patients experience symptoms such as fatigue, fever, nausea, appetite loss, jaundice, a yellowing of the skin or whites of the eyes due to hyperbilirubinemia, diarrhea, light or clay-colored stools (acholic faeces), and abdominal discomfort (Ciocca, 2000; CDC, 2009). Bile is removed from the bloodstream and excreted in the urine, giving it a dark amber color.

1.2.3.7. Extrahepatic manifestations

Extrahepatic symptoms include pancreatitis, red cell aplasia, joint discomfort, and widespread lymphadenopathy. Pericarditis with kidney failure are extremely rare conditions. If they materialize, they have an abrupt start and end when the illness resolves (Mauss et al., 2012).

1.2.3.8. Diagnosis

After hepatovirus A infection, serum IgG, IgM, and ALT levels. HAV is eliminated in the feces at the conclusion of the incubation period, but the identification of HAV-specific IgM antibodies in the blood allows for a precise diagnosis. The blood only contains IgM antibodies after an acute hepatitis A infection. It appears 1-2 weeks following the original illness and lasts for up to 14 weeks. IgG antibodies in the blood indicate that the sickness has progressed past its acute phase and that the patient is no longer susceptible to infection. After vaccination, IgG antibodies to HAV are also detected in the blood, and the presence of these antibodies serves as the basis for testing to determine a person’s immunity to the virus (Musana et al., 2004).

The liver enzyme alanine transferase (ALT) is significantly more prevalent in the blood than usual during the acute stage of the infection. The virus-damaged liver cells produce the enzyme. Up to two weeks before a clinical sickness manifests, hepatovirus A can be found in the blood (viremia) and feces of infected individuals (Musana et al., 2004).

1.2.3.9. Prevention

a. Vaccination

Hepatovirus A, either inactivated or attenuated, is contained in the two vaccination forms. Both offer proactive defense against upcoming infections. For almost 25 years, the vaccine offers protection against HAV in over 95% of instances. The vaccination Maurice Hilleman and his colleagues produced was approved in 1995 and administered to children in high-risk areas for the first time in 1996. In 1999, the vaccine was expanded to places where infection rates were rising (CDC, 2006).

1.2.3.10. Treatment

Hepatitis A does not currently have a specific treatment. After an infection, symptoms may be slow to go away and may take weeks or months. It’s critical to stay away from needless drugs. Avoid using acetaminophen, paracetamol, and antiemetic medications if you have vomiting (WHO, 2022). Hospitalization is not required if acute liver failure is not present. The goal of therapy is to preserve comfort and a healthy nutritional balance, which includes replenishing fluids lost due to diarrhea and vomiting (WHO, 2022).

1.3. Objective of this study

1.3.1. General objectives

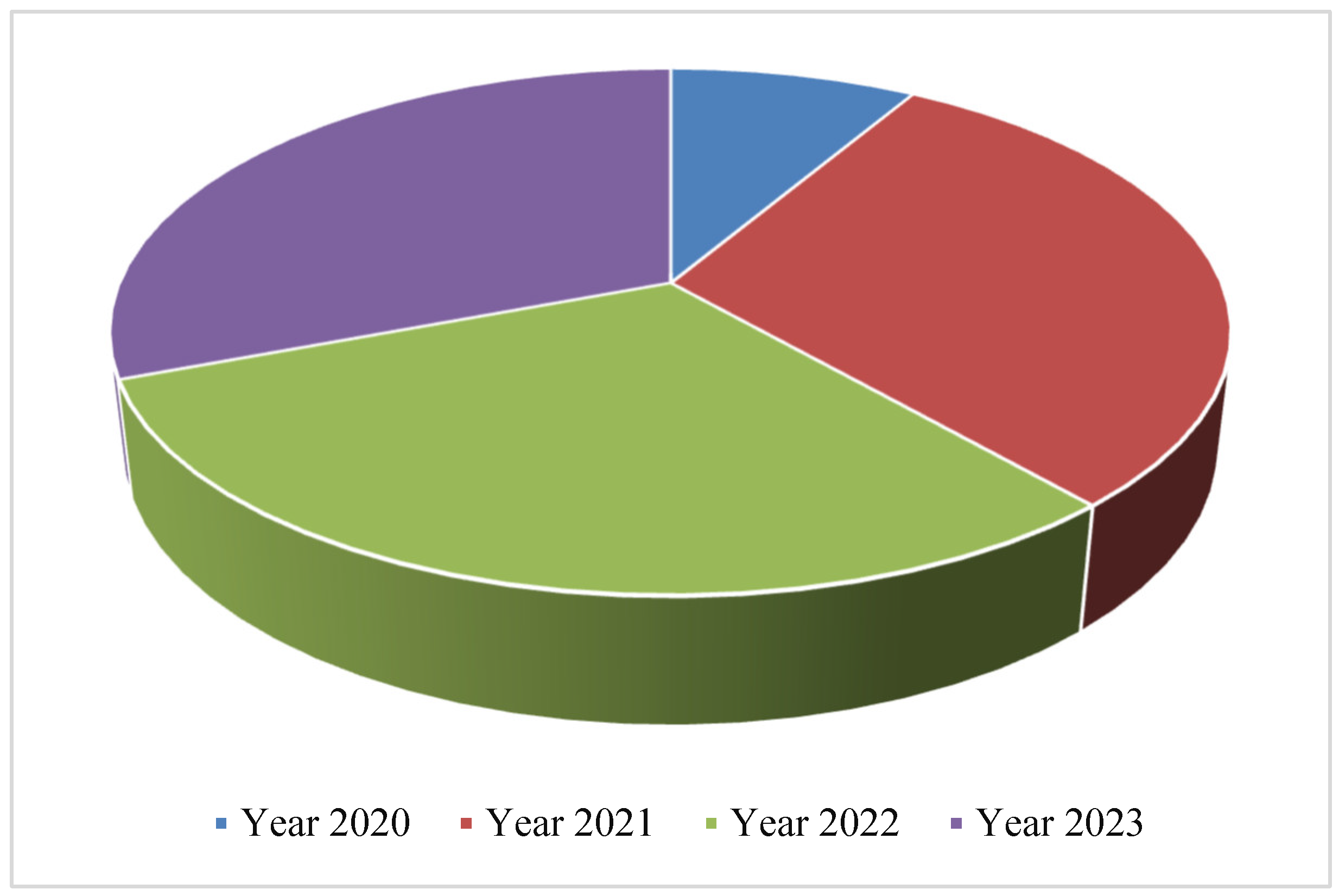

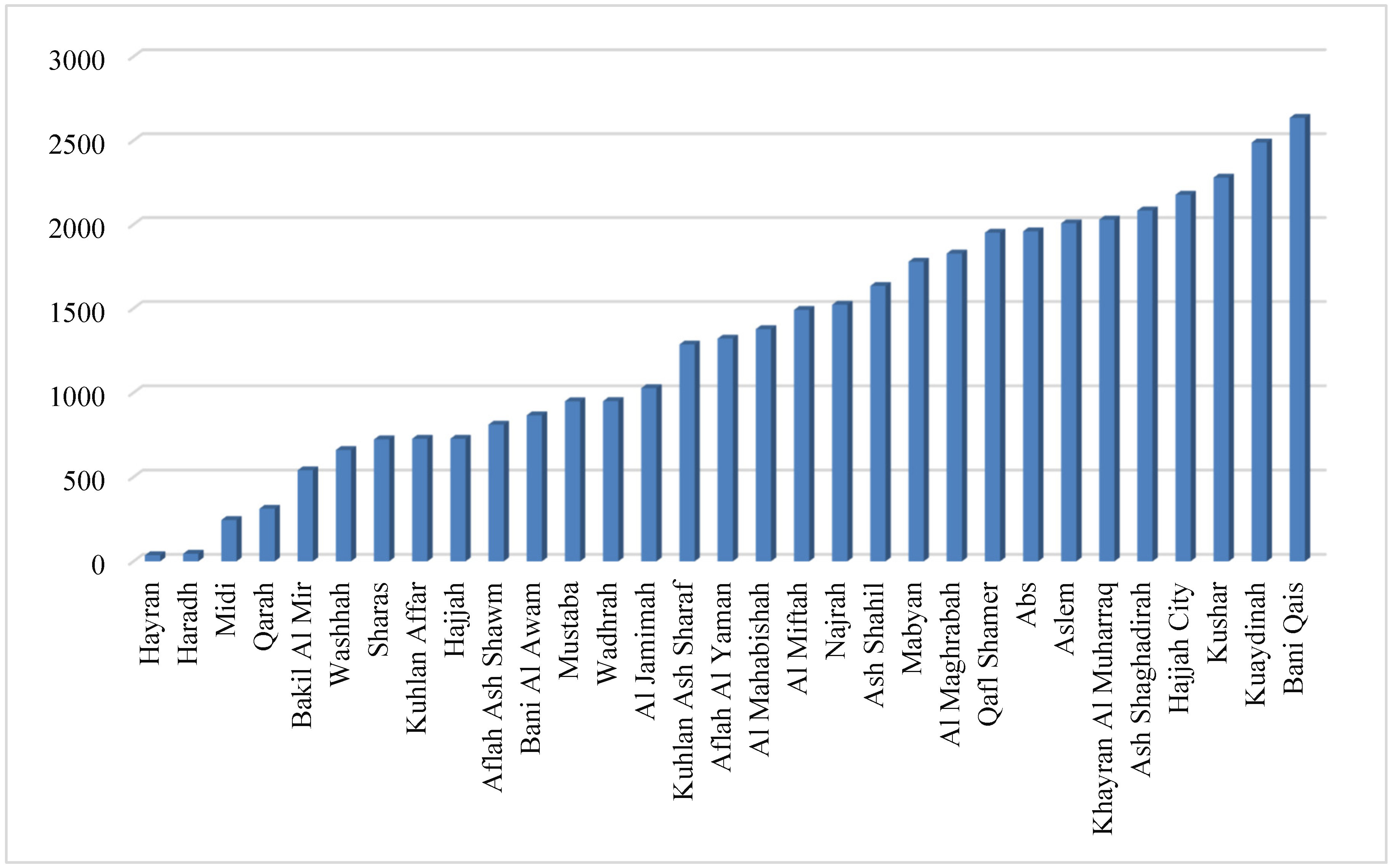

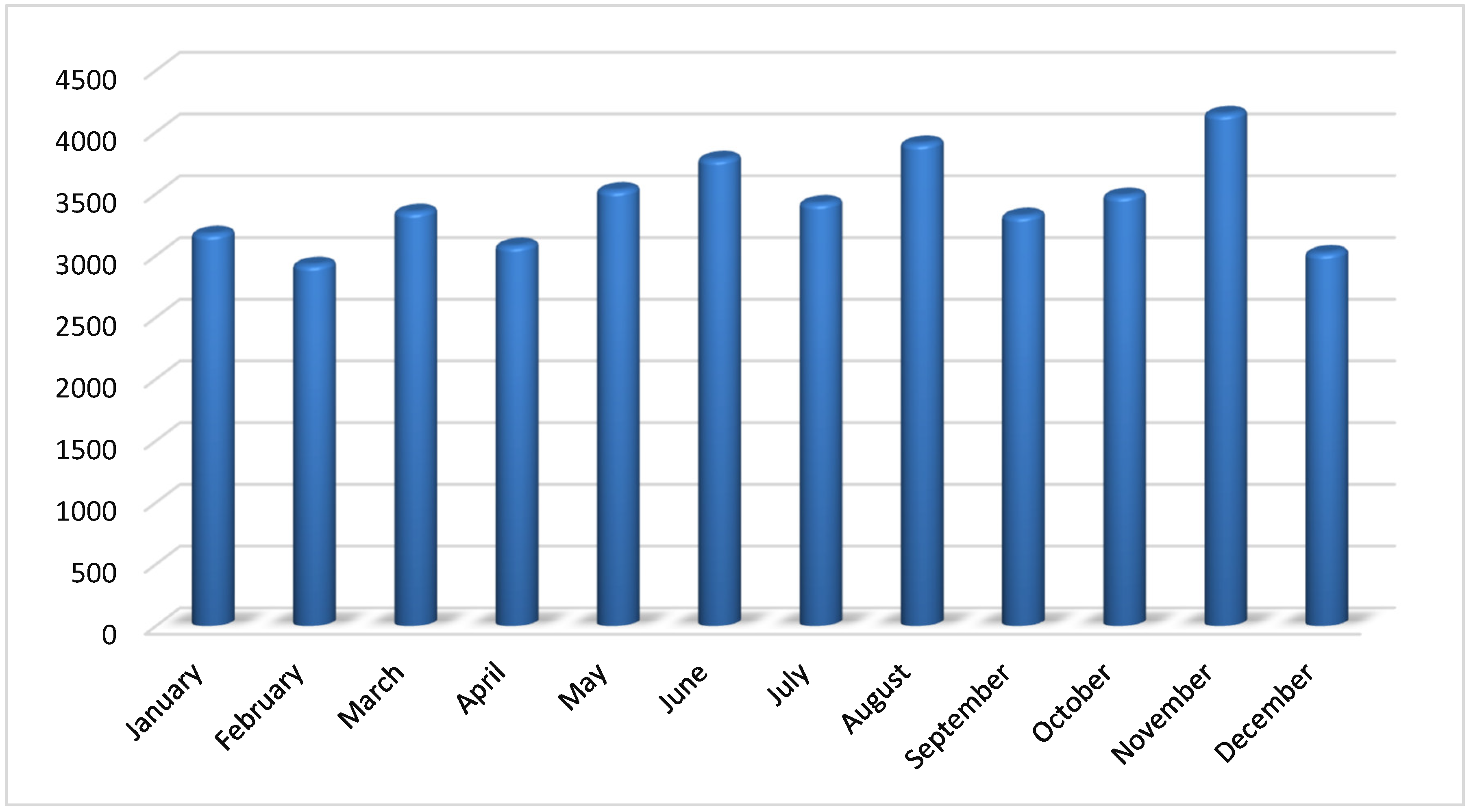

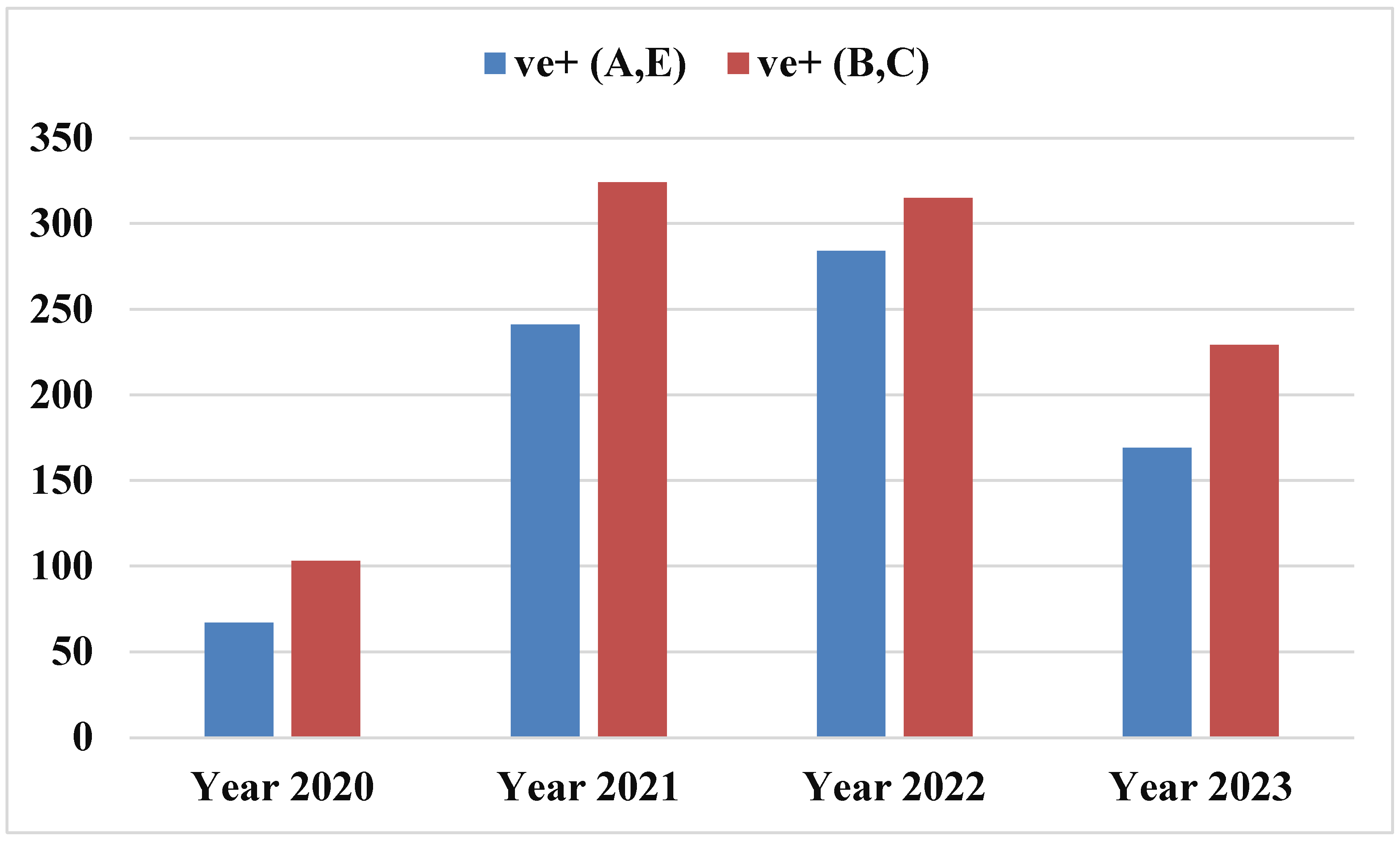

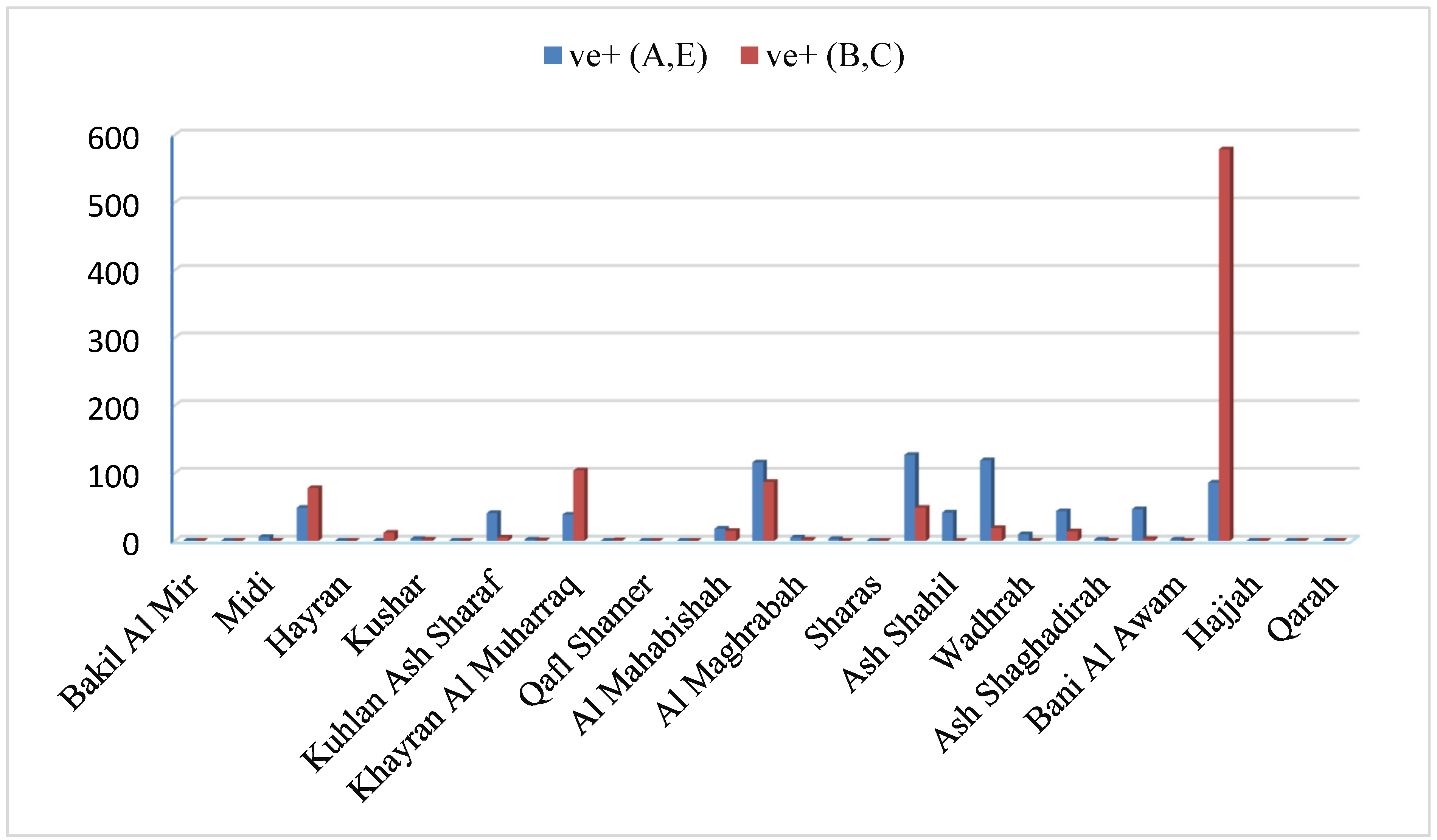

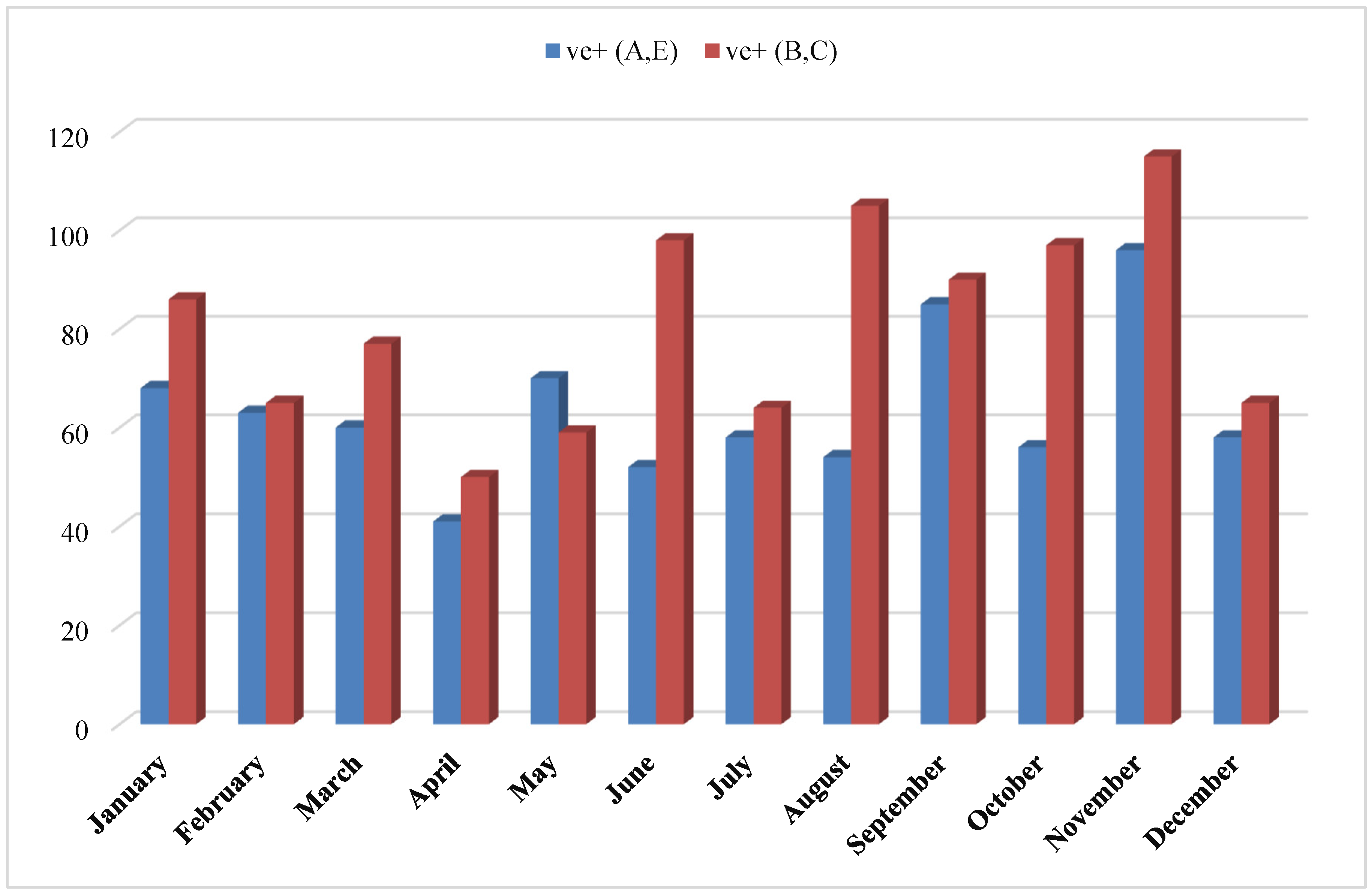

The aim of the present investigation was designed to determine the prevalence of hepatitis A, E, B and C viruses in Hajjah governorate between 2020-2023, Yemen.

1.3.2. Specific objectives

To determine the prevalence of viral hepatitis in Hajjah governorate between 2020-2023.

To evaluate the demographic factors influencing the prevalence of viral hepatitis infection in Hajjah governorate between 2020-2023.