1. Introduction

Disasters disproportionately affect developing countries, with the poor and marginalized people bearing the brunt (Hillier & Nightingale, 2013). The capacity of individuals to cope or recover following a disaster is contingent upon an intricate interplay of factors, including abilities, class, gender, social networks, income, land and other assets, information access, legal entitlements, government policies, and mechanisms, among other considerations. Disparities in physical and financial capabilities, along with uneven access to resources, can render specific groups more susceptible than others, potentially intensifying social divisions and conflicts (Hyndman & Hyndman, 2011; Wisner et al., 2014; De Juan et al., 2020). Disasters exacerbate coping and recovery capacities, leading to heightened vulnerabilities (Bates & Peacock, 1989; Hyndman & Hyndman, 2011; He et al., 2018).To assist vulnerable beneficiaries overlooked in post-earthquake, governmental and non-governmental organisations introduced Socio-Technical assistance (STA) in conjunction with Owner-driven reconstruction (ODR) in Nepal.

Nepal is ranked as the 20th most disaster-prone country globally and holds the 4th, 11th, and 20th positions in various climate change vulnerability categories (MoHA, 2017; ADRC, 2020). The 7.8 magnitude earthquake of April 25, 2015, led to more than 8,790 fatalities and over 22,300 injuries and incurred approximately $7 billion in damages, with housing (755,000 houses destroyed or damaged) contributing to nearly half of the total damages (Global Shelter Cluster, 2019). Nepal’s post-earthquake reconstruction is considered the world’s largest owner-driven housing reconstruction (ODR) effort, with over 753,104 beneficiaries (93%) rebuilding their houses (NRA, 2021). In response, the Government of Nepal (GoN) embraced the Owner-Driven reconstruction (ODR) approach in accordance with the ‘Build Back Better’ approach outlined in the Sendai Framework (UNDRR, 2015-30) based on the successful international implementation, considered as a ‘global default reconstruction strategy’ in low-income countries (Karunasena & Rameezdeen, 2010a; Lam, 2022). ODR emphasizes a process-driven housing reconstruction, fostering beneficiary involvement, promoting self-reliance, livelihood exploration, and improving quality of life, resilience, and connectivity. In contrast, a product-driven approach focusing solely on house delivery results in a passive dependency (UNDP, 2021b). There is a growing need for empirical evidence, as shelter and settlement interventions remain an inadequately explored facet of the humanitarian response (Twigg, 2006; Peacock et al., 2007; Peacock et al., 2018) and to explore impacts (Ganapati & Mukherji, 2014).

Against this backdrop, the paper examines the effectiveness of the Socio-Technical Assistance (STA) program combined with Owner-driven reconstruction, especially for vulnerable households, also synonyms used in this paper as ‘beneficiaries’ left behind in the large-scale private housing reconstruction. The research highlights the positive impact of well-implemented STA activities in providing crucial relief to vulnerable earthquake beneficiaries and leading their recovery efforts in rural housing reconstruction. It stresses the necessity of socio-technical facilitation mechanisms at different levels.

2. Literature Review and Research Gaps

Numerous studies focus on the successful international implementation guidelines and models for the Owner-driven reconstruction (ODR) approach (Barenstein et al., 2010; IFRC, 2010; Build Change, 2014; Tafti & Tomlinson, 2015; Vahanvati & Beza, 2017a; UNDP, 2021b; Hunnarshala Foundation, n.d,) as well as framework (Barenstein, 2006a; 2006b; Bilau et al., 2015; Vahanvati & Beza, 2015; Ade Bilau & Witt, 2016; Vahanvati & Mulligan, 2017; Bilau et al., 2018; Vahanvati, 2018), satisfaction (Bhusal & Bhattarai, 2023), evaluation of ODR(Lam, 2022), comparative study of donor vs owner-driven reconstruction approach (Karunasena & Rameezdeen, 2010a; Andrew et al., 2013), limitations of ODR (Taheri Tafti, 2012); there is a notable dearth of research specifically assessing the effectiveness of STA interventions on vulnerable beneficiaries. Existing studies primarily explore specific programs, and few address the effectiveness of STA targeting vulnerable beneficiaries eight years after the earthquake. In our earlier study, we had observed the heterogeneity of households due to several background factors, including gender, age, education, religion, ethnicity, and vulnerability, whether satisfaction rates differed across the factors have been tested in our previous study (Bhusal & Bhattarai, 2023).

Previous research highlights challenges in Nepal’s reconstruction, such as not being able to build houses even after receiving grants due to the government’s inefficiency in delivering funding and services to affected beneficiaries and the lack of coordination among NGOs (Lam et al., 2017), geographical challenges (Bothara et al., 2016; Sharma et al., 2018), vulnerability and social inequality (Jackson et al., 2016; Eichenauer et al., 2020; Rawal et al., 2021), issue of INGO’s top-down policy implementation (Sanderson & Ramalingam, 2015) and corruption (Dhungana & Cornish, 2021). Despite implementing the ODR model, vulnerable beneficiaries were evidenced from this study to be ‘left behind’ through the large-scale private housing reconstruction.

Limited studies have assessed the effectiveness of STA interventions on project-specific program interventions in Nepal’s post-earthquake context, evaluating specific projects outcomes (Dhungel et al., 2019; Gouli et al., 2019; Karki et al., 2020b; Lamsal et al., 2020; Manindra Malla, 2020; NSET, 2023; Hunnarshala Foundation, n.d,), inclusion of poor and vulnerable (Rawal et al., 2021), approaches to build back better (JICA, 2019a; 2019b; Nagami et al., 2021), community mobilization program (JICA, 2019a), Socio-Technical assistance (The World Bank, 2020-2021), Socio-Technical Facilitation (UNDP, 2019; 2021a). Therefore, there is a need for an independent research study to assess the effectiveness of targeting vulnerable beneficiaries even eight years after the earthquake.

The lessons from the 2004 South Asian tsunami underscore the importance of aligning aid with actual needs and ensuring long-term sustainability (Torrente, 2013). However, research is scarce on the perspectives of ‘bottom-up’ or aid recipients, hindering a comprehensive understanding and enhancement of aid quality (Ramalingam et al., 2009; Sandvik, 2017). Marginalized individuals often struggle to advocate for themselves, posing challenges for humanitarian organizations to address their needs effectively (Torrente, 2013) and ensure aid reaches the intended target group. Consequently, there is a need for renewed guidelines and criteria, particularly for the most vulnerable (Clay et al., 1999).

An in-depth examination of specific cases is essential to illustrate how interventions lead to distinct evidence to assess the prompt delivery of aid and its effectiveness in bringing about intended improvements in recipients’ lives (Proudlock et al., 2009). Moreover, it is crucial to generate reliable evidence to assess the prompt delivery of aid, its effectiveness in bringing about intended improvements in recipient’s lives (Puri et al., 2014; Maynard et al., 2017), and its alignment with the humanitarian assistance context.

3. Critical Evaluation of Owner-Driven Reconstruction (ODR)

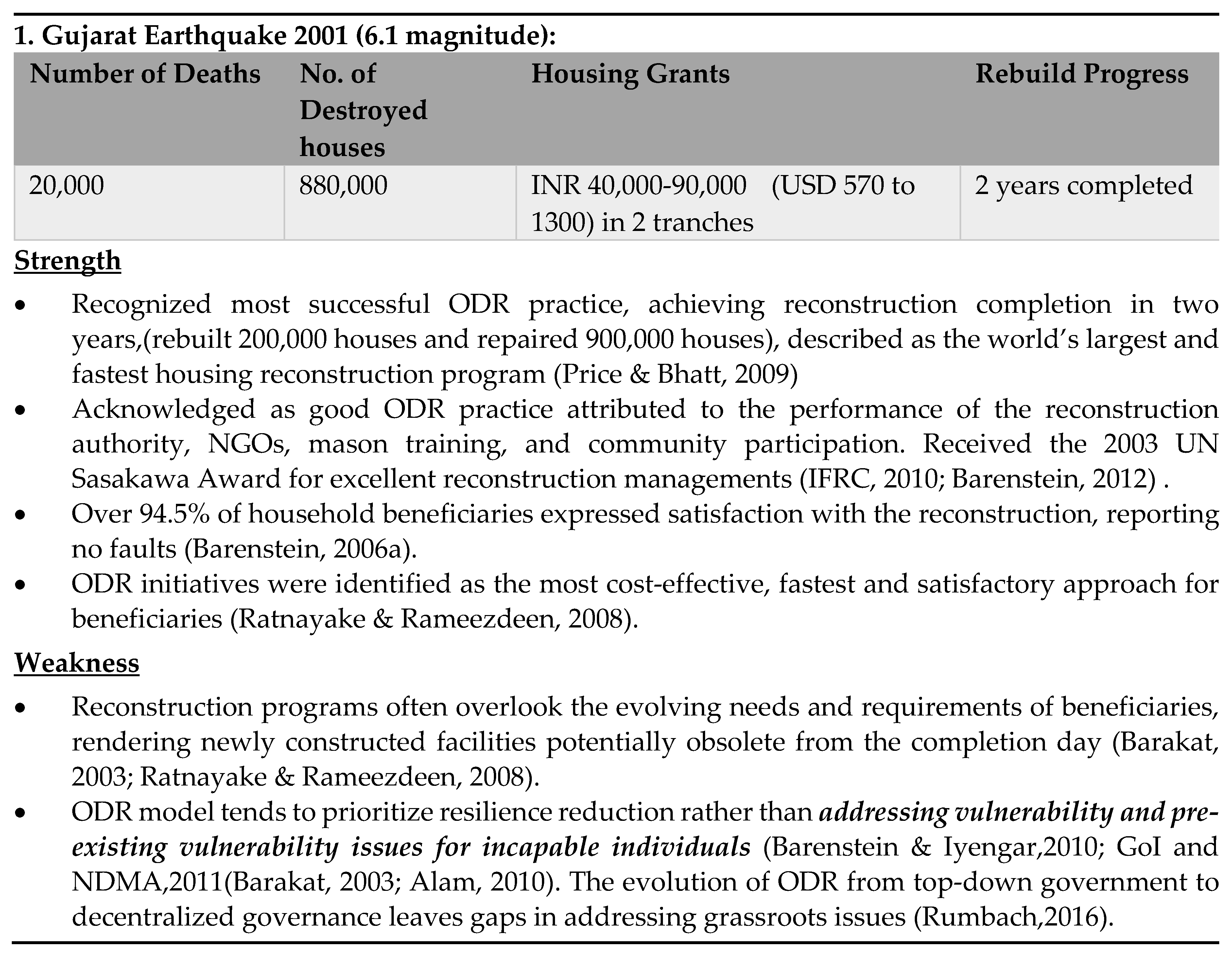

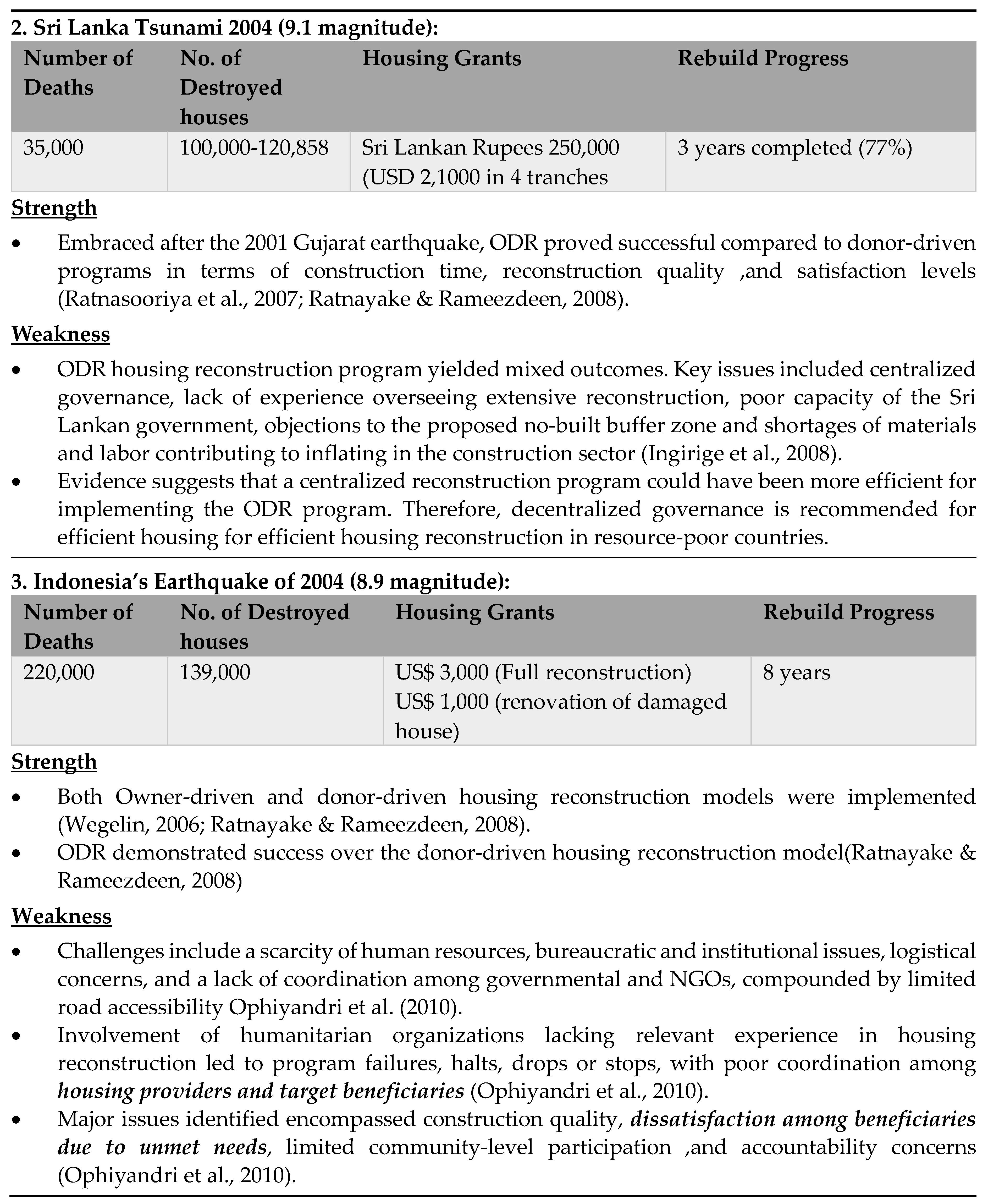

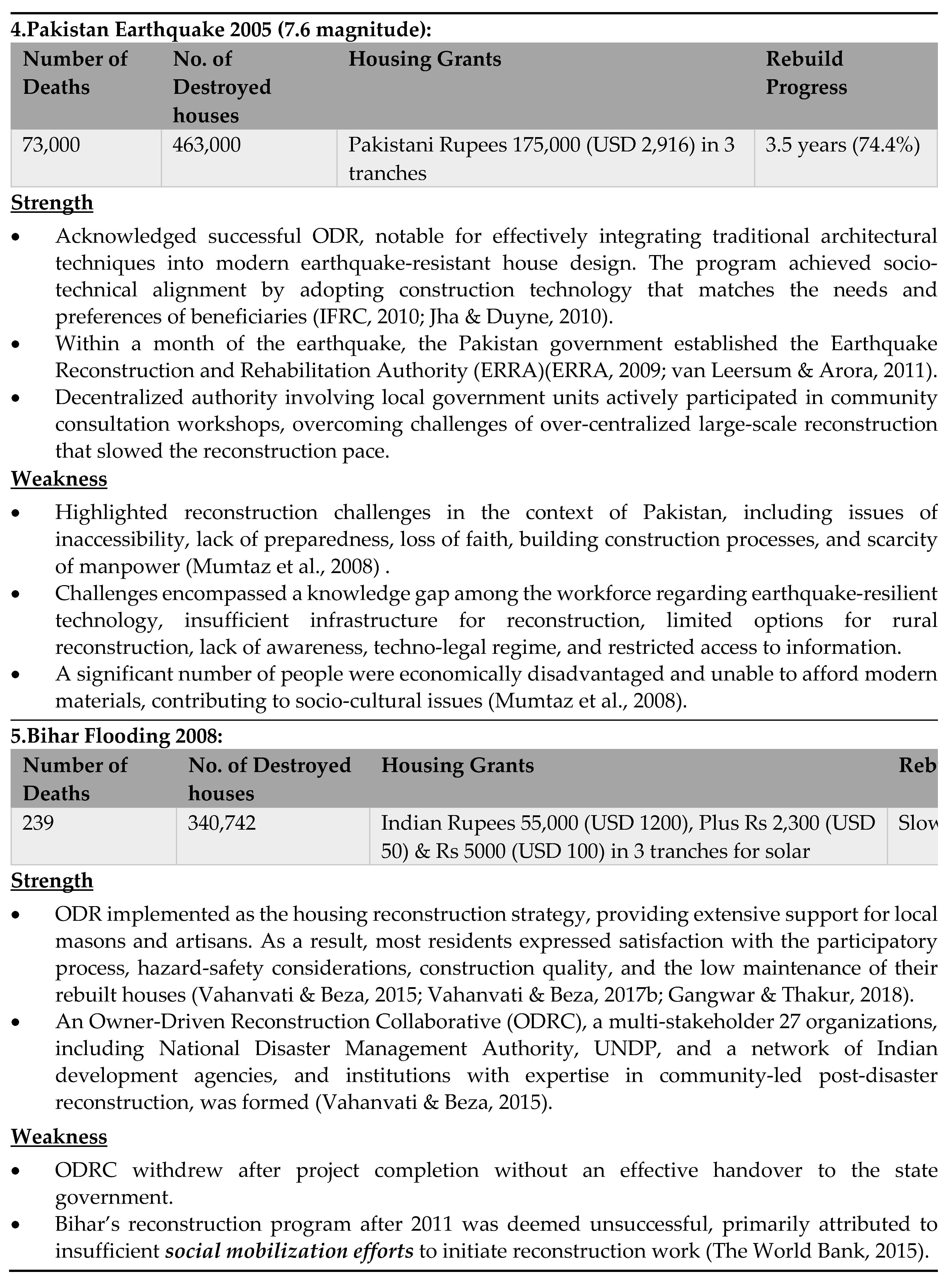

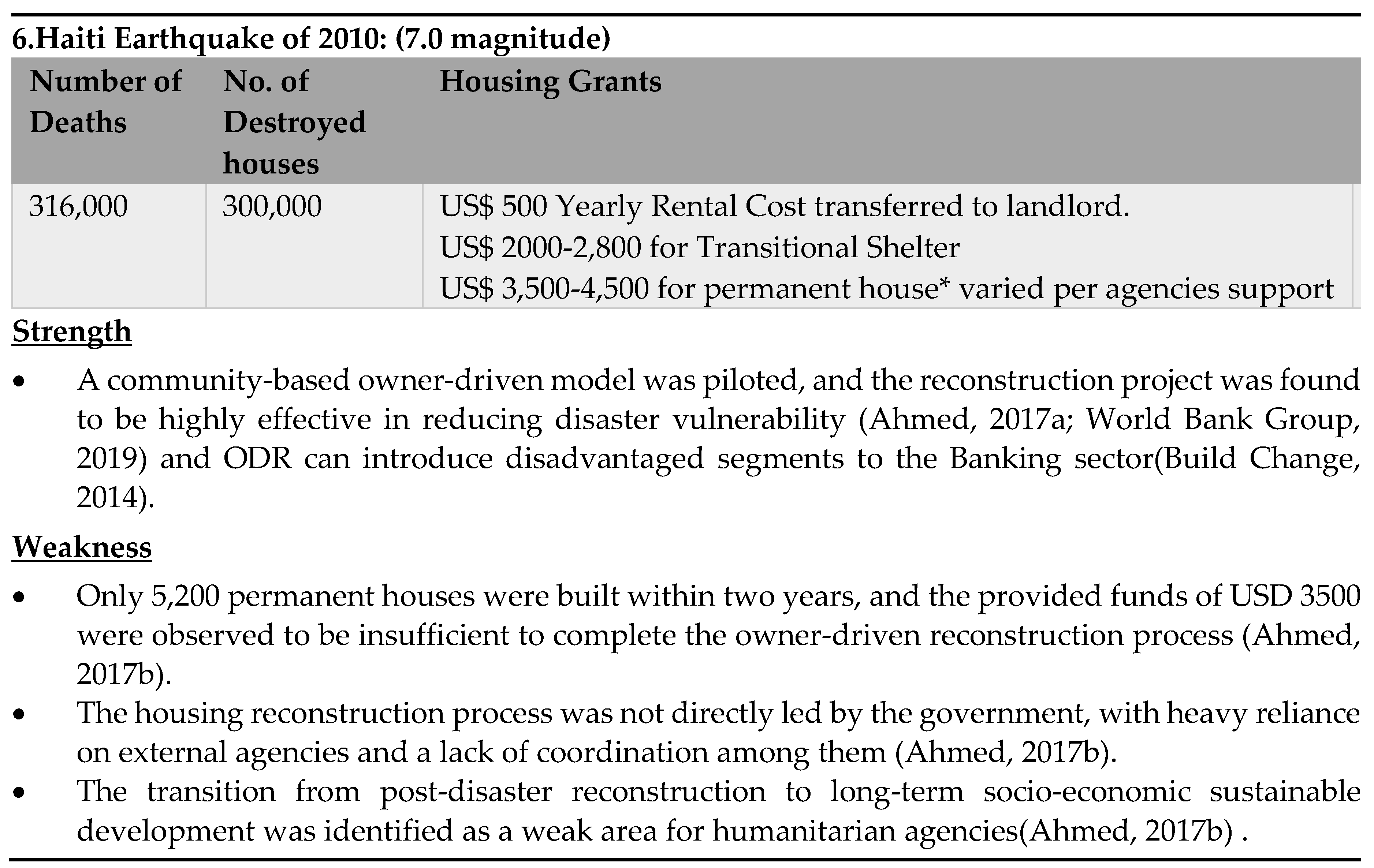

Table 1 presents an overview of the merits and drawbacks of the ODR model, recognized as a ‘default strategy’ in low-income countries and implemented in various post-disaster contexts. These include Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Indonesia, India (Gujarat, Tamil Nadu, and Bihar), and Haiti.

The analysis above

Table 1 sheds light on the limitations of the ODR model. While ODR evaluations often report positive outcomes, experiences from disasters like the Gujarat earthquake, Tamil Nadu, and Haiti’s recovery highlight the limited universal effectiveness of the informally applied ODR (Barenstein, 2006a; Barenstein et al., 2010). Adapting program approaches to be ‘demand-driven’, considering regional variations, is crucial, recognising that ODR cannot provide a ‘one-size-fits-all’ solution for post-disaster housing challenges. Concerns arise about the evolving nature of ODR, aiming to ‘build back better’ with high building standards and social-technical community support, potentially proving insufficient in extensive reconstruction projects (Hidellage & Usoof, 2010).

Existing research underscores the benefits of the ODR model based on labour availability and straightforward housing designs (Lyons, 2009). Challenges extend beyond housing investment, encompassing housing governance and the procurement process (Schilderman, 2004). However, this study indicates that vulnerable beneficiaries need assistance to lead the reconstruction process independently. Furthermore, the above analysis reveals limitations in the ODR approach, with scant evidence from a vulnerable household perspective. Studies emphasize unsuccessful reconstruction, citing insufficient social mobilization (The World Bank, 2015) and lack of evidence for support and program effectiveness from the ‘user-end’. These studies underscore the necessity for a distinct, targeted approach for the most vulnerable, drawing lessons from Nepal’s ODR-STA intervention (Caritas, 2019; Dhungel et al., 2019; Gouli et al., 2019; JICA, 2019a; Karki et al., 2020b; Manindra Malla, 2020; The World Bank, 2020-2021; Adhikari et al., 2021; NSET, 2021; Rawal et al., 2021).

4. Conceptual Framework of This Study

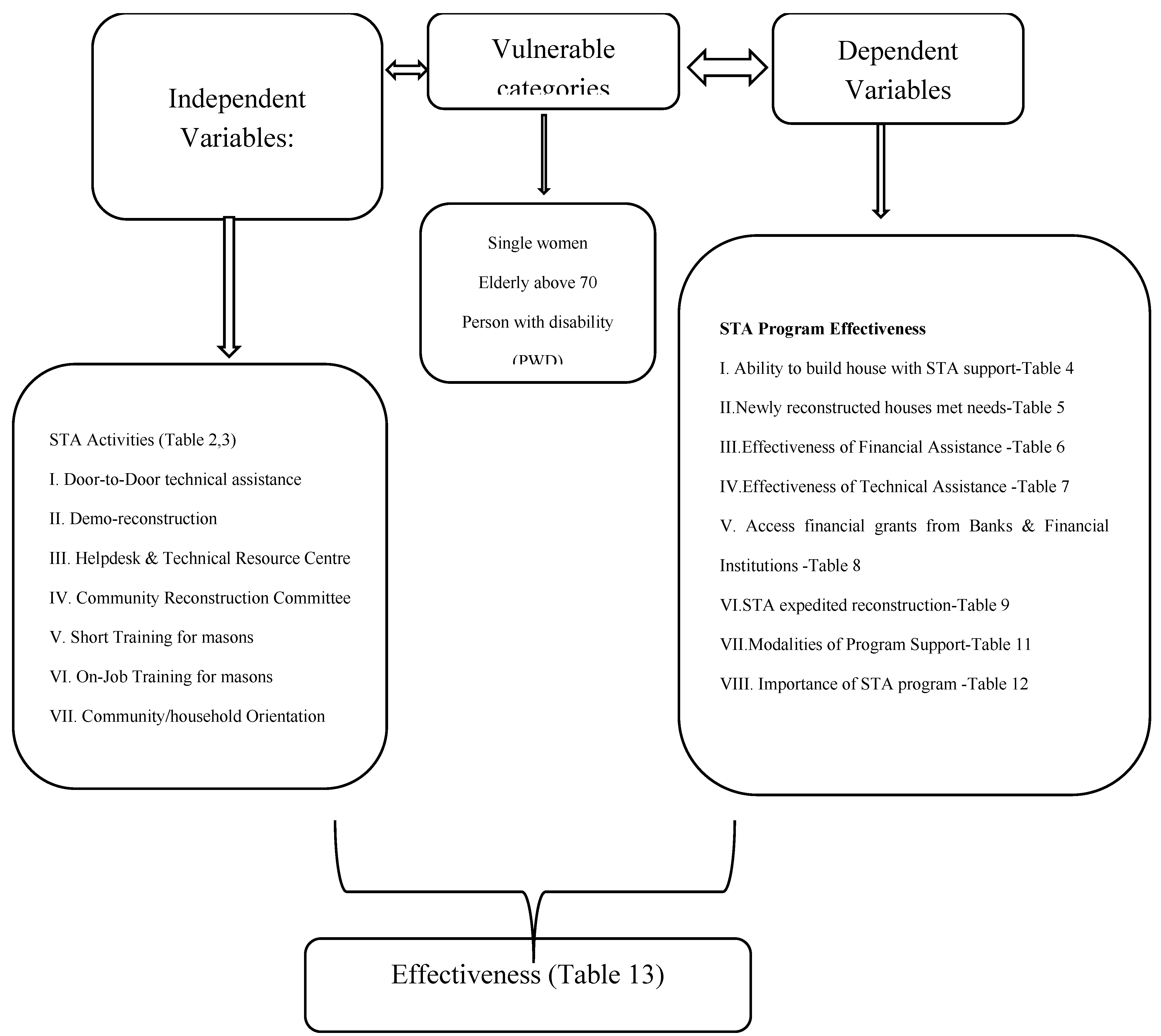

This study aims to assess the effectiveness of the ‘demand-driven’ STA program in rural private housing reconstruction settings through a quantitative survey of 304 vulnerable beneficiaries. The conceptual framework given below illustrates the causal relations between independent variables (STA Activities: seven activities) and dependent variables in program outcomes, focusing on the user-end’s perspectives of vulnerable beneficiaries.

Dependent Variables:

The study examined the outcomes of Social Technical Assistance (STA) interventions in supporting vulnerable beneficiaries in private housing reconstruction as depicted in the above conceptual framework (Fig 2). Participants were surveyed on various aspects, including their ability to construct houses with or without STA support, the satisfaction of needs in newly reconstructed houses, the effectiveness of financial and technical assistance, access to financial grants from Banks and Financial Institutions (BFIs), the acceleration of reconstruction facilitated by STA, awareness of disaster risk reduction (DRR), and the perceived need for STA among vulnerable categories. The study analysed the findings of both constructs – STA activities (Independent variable) and outcomes as (Dependent variable) in measuring Effectiveness STA activities.

Independent Causal Factors

These can be enumerated as follows:

-

Door-to-door technical Assistance, Demo-Reconstruction, Helpdesk & Technical Resource Centre, Community Reconstruction Committee, Community/Orientation, Short Training for Masons, and On-Job Training for Masons.

- ▪

Positively influence Ability to Build a House and reconstruction skills with STA

- ▪

Contributes to the STA Expedited Reconstruction

-

STA Expedited Reconstruction:

- ▪

Positively affects Newly Reconstructed House Met Need.

-

STA Expedited Reconstruction, Effectiveness of Financial Assistance, and Effectiveness of Technical Assistance:

- ▪

Influence Access to Financial Grants from Bank & Financial Institutions.

-

Awareness of Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR):

- ▪

Influenced by Community Reconstruction Committee, Helpdesk & Technical Resource Centre, and Training.

-

Need of STA for Vulnerable Categories and Importance of STA Program Activities:

- ▪

Influence Effectiveness of STA Program Activities.

The study challenges the assumption that owner-driven reconstruction (ODR) or ‘self-recovery’ is universally applicable, particularly in vulnerable contexts, as suggested by previous literature (Barenstein, 2006a; Hidellage & Usoof, 2010; Jha, 2010; Karunasena & Rameezdeen, 2010b; Barenstein, 2012; Andrew et al., 2013; Vahanvati & Beza, 2015; Maynard et al., 2017; Lam, 2022).

There is a significant gap between project implementation and completion, often due to terminated projects or achievement-focused outcomes, neglecting of future program dynamics and sustainability. Assistance for disaster-affected individuals often needs more timelines, adequacy, fairness, and predictability. The above conceptual framework, summarized in

Figure 2, delineates the logical sequence of the seven Independent Variable STA activities that culminate in the Dependent Variable for desired effectiveness in the lives of vulnerable beneficiaries. The detailed operational definition of these measurement variables is as illustrated in

Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Framework of this study.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Framework of this study.

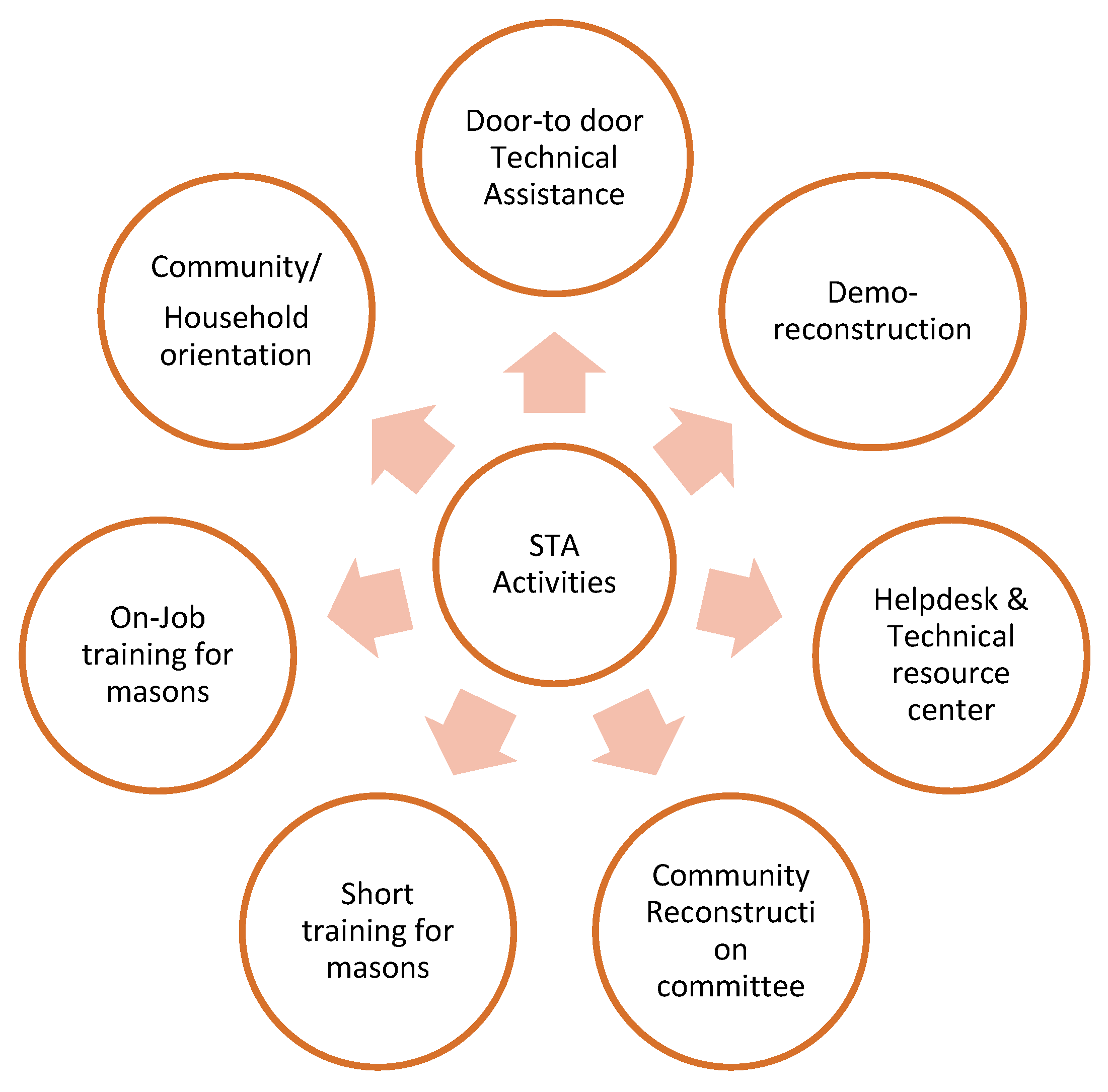

Figure 2.

Core Socio-Technical Package; Source: (HRRP, 2017b).

Figure 2.

Core Socio-Technical Package; Source: (HRRP, 2017b).

Table 2.

Socio-Technical Assistance (Independent Variables).

Table 2.

Socio-Technical Assistance (Independent Variables).

| |

Socio-Technical Assistance (Seven Activities) |

| I |

Door-to-door technical assistance: Field mobile teams, including social mobilizers and mobile masons, provided on-site support, assisting vulnerable beneficiaries in accessing financial and technical aid, documentation, and overall reconstruction guidelines. |

| II |

Demo-Reconstruction: Practical initiative clarifying construction information, customizing for local practices, complementing existing materials. |

| III. |

Helpdesk & Technical Resource Centre: Provides reconstruction support and advice and facilitates access to information/resources through social mobilization staff. |

| IV |

Community Reconstruction Committees: Enhance community participation, ownership, and coordination in the reconstruction process. |

| V |

Short Training for Masons: a 7-day program to enhance mason skills, prioritizing earthquake-affected individuals, women, and the untrained. |

| VI |

VI. On-the-Job Training for Masons: the 50-day program to expand the skilled labour force with expertise in earthquake-resistant structures. |

| VII. |

Community/household Orientation: Enhance communication, create awareness of policies and standards, and coordinate with community committees and officials through the helpdesk/technical resource centre. |

5. Description of the Study Area and Methodology

5.1. Nepal’s Post-earthquake Owner-Driven Housing Reconstruction

The recovery concept involves rebuilding, restoring, rehabilitating and redeveloping, centered on “putting the community back together again”(Nigg, 1995). ODR approach prioritizes recipient “choice” and diverse household coping strategies to alleviate disaster impacts. Involvement in the design and building process significantly impacts psychological recovery households, empowering them and providing control over uncontrollable circumstances (Lyons, 2009). ODR was initially adopted as a ‘default strategy for post-disaster housing reconstruction after the 2001 Gujarat earthquake (2001), the South Asian tsunami (2004), and the Kashmir earthquake (2005) (Mishra, 2006; Mumtaz et al., 2008; Baker et al., 2010; Rawal et al., 2021).

Nepal’s post-earthquake housing reconstruction is considered one of the largest owner-driven housing reconstruction programs globally, reconstructing more than 700,000 houses through a dedicated new entity ‘National Reconstruction Authority’. GoN provided uniform cash grants of NPR 300,000 (about $3,000) to affected beneficiaries, disbursed in tranches tied to construction compliance. Partially damaged homes received NPR 100,000 (about $1,000) in two tranches, with an additional NPR 50,000 (about $500) top-up for vulnerable beneficiaries (HRRP, 2017a).

5.2. Socio-Technical Assistance Component

Despite the success of Owner-Driven Reconstruction (ODR) in constructing nearly 741,031(NRA, 2024) houses in Nepal, post-earthquake challenges persist for vulnerable populations. To address inclusivity, a Socio-Technical Assistance (STA) module was introduced in collaboration between the government and partner agencies to ensure that 'No one is left behind.' Recognizing the distinct needs of vulnerable beneficiaries, implementing the STA module was deemed necessary (HRRP, 2017a; 2020). GoN of Nepal identified 18,505 beneficiaries (2.4%) as vulnerable from 782,695 beneficiaries for the top-up housing assistance (Rawal et al., 2021).The STA program entails seven core activities (Refer-Fig 2), outlined by the NRA and HRRP , and complements financial and technical assistance by guiding beneficiaries to meet reconstruction standards within a specified timeframe (HRRP, 2017a; 2019). It aims for transformative change, requiring behavioural shifts and empowering communities through capacity-building training and income-generating activities.

The ODR model proved ineffective for vulnerable beneficiaries, leading to the recognition of the STA modality in the Post-disaster needs assessment, aligned with the “Leave No One Behind” approach (NPC, 2015; NRA, 2016). Non-governmental agencies, avoiding a blanket approach, implemented the STA module, promoting the NRA to reintroduce the STA model due to its proven effectiveness in expediting reconstruction for the most vulnerable beneficiaries (JICA, 2019a; UNDP, 2019; Karki et al., 2020b; MDTF, 2021; NSET, 2021).

The key criteria for Socio-Technical Assistance are to:

- ▪

Engage all families and communities in timely and relevant guidance for safer and sustainable house construction, providing support throughout the inspection process.

- ▪

Enhance the availability and proficiency of skilled construction workers to facilitate reconstruction.

- ▪

Foster community resilience and long-term benefits.

5.3. Research Motivation, Geographical Locations, and Participants

First-hand experience the first author as a survivor during the 2015 Nepal Earthquake inspired a research focus on assessing the perspectives of ‘end-users’ regarding the effectiveness of post-disaster reconstruction activities, specifically STA combined with the ODR program. This study is part of a broader initiative examining post-disaster recovery among government-identified vulnerable beneficiaries, extending even into the eight years after the earthquake in the context of rural private housing reconstruction.

5.4. Data Collection Methods

The research employed a quantitative approach using a questionnaire survey gathered through a pen-and-paper survey administered to 304 vulnerable beneficiaries, later manually entered into JISC online software to ensure data quality. The field data collection occurred between May and July 2022 in Gorkha districts, covering three municipalities (Palungtar, Gorkha and Sulikot/Barpak). Cluster random sampling was used to select respondents. The questionnaire, designed by the author and translated into Nepali, ensured clarity and respondent anonymity using pseudonyms. Ethical approval and clearance were obtained from relevant authorities to conduct the study.

5.5. Sampling Size Calculation and Data Analysis

The survey targeted vulnerable beneficiaries identified by the Government of Nepal, National Reconstruction Authority (NRA), with a total of 18,505 individuals identified in 32 earthquake-affected regions as vulnerable under criteria including senior citizens above 70 years, single women above 65 years and People with Disabilities (red or blue cardholders), excluding minors under 16 years due to ethical issues. Gorkha district was the center of the earthquake and classed as a ‘highly affected’ region; the total identified as a vulnerable population was (N)=1431, 95% confidence level (Z value),5% margin of error (e value), and 50% prevalence (p-value). From the calculation, the sample size becomes 304 for the questionnaire survey. Quantitative data analysis, including descriptive and Chi-square tests, were conducted using the statistical software SPSS.

5.6. Research Questions and Hypotheses

This research aims to assess the effectiveness of socio-technical assistance on vulnerable earthquake beneficiaries in Nepal, focusing on its effectiveness in private housing reconstruction, particularly those involved in private housing reconstruction. We quantitatively test the following research hypothesis using our database constructed from the primary survey.

H1: There is no significant association between vulnerable categories and the likelihood of building a house with STA support.

H2: There is no significant association between vulnerable categories and the level of agreement on whether newly reconstructed houses met their needs in the STA program.

H3: There is no significant association between vulnerable categories and the perceived effectiveness of Financial Grants in the STA program.

H4: There is no significant association between vulnerable categories and the perceived effectiveness of Technical Assistance in the STA program.

H5: There is no significant association between vulnerable categories and the level of agreement on STA support in receiving tranches from Banks and Financial Institutions (BFIs)

H6: There is no significant association between vulnerable categories and the level of agreement on STA activities expediting reconstruction.

H7: There is no significant association between the vulnerable categories and the perceived importance of the STA program activities.

H8: There is no significant association between the vulnerable categories and the perceived DRR (disaster risk reduction) awareness of the STA Program.

6. Results and Discussion

The study assessed the participation and effectiveness of the seven STA Activities, aligning with the overarching goal of ensuring that vulnerable beneficiaries reconstruct their homes and communities within specified standards and timeframes.

Table 3 summarizes the engagement in STA activities among vulnerable beneficiaries, with the overall participation percentages as follows: (i) Community/household Orientation: 66.45 %, (ii) Door-to-door to technical assistance: 39.80%,(iii) Short Training for masons:60.86%, (iv) Helpdesk & communication centre: 29.28%,(v) Demo-construction: 34.21 %, (vi)Reconstruction committee support:9.87%, (vii) On-job training for masons:3.29%.

Table 3.

Socio-Technical Assistance Seven Activities (STA).

Table 3.

Socio-Technical Assistance Seven Activities (STA).

| STA Activities |

Vulnerable Categories |

Total |

| Single Women above 65 Years |

Elderly above 70 Years |

Persons with disabilities (PWD) |

| Total |

Community/household Orientation |

Count |

62 |

124 |

16 |

202 |

| % |

68.1% |

63.9% |

84.2% |

66.45% |

| Door to door technical assistance |

Count |

36 |

80 |

5 |

121 |

| % |

39.6% |

41.2% |

26.3% |

39.80% |

| Short Training for masons |

Count |

51 |

122 |

12 |

185 |

| % |

56.0% |

62.9% |

63.2% |

60.86% |

| Helpdesk & communication center |

Count |

25 |

59 |

5 |

89 |

| % |

27.5% |

30.4% |

26.3% |

29.28% |

| Demo-Construction |

Count |

31 |

66 |

7 |

104 |

| % |

34.1% |

34.0% |

36.8% |

34.21% |

| Reconstruction committee support |

Count |

7 |

22 |

1 |

30 |

| % |

7.7% |

11.3% |

5.3% |

9.87% |

| On-job training for masons |

Count |

4 |

6 |

0 |

10 |

| % |

4.4% |

3.1% |

0.0% |

3.29% |

| Total |

Count |

91 |

194 |

19 |

304 |

| Percentages and totals are based on respondents. |

| a. Dichotomy group tabulated at value 1. |

Surveyed participants identified the most effective STA activities based on their engagement in supporting their reconstruction efforts as follows: (i) Orientation: 84.2% PWD, (ii) Door-to-door technical support: 41.2% Elderly above 70, (iii) Short training: 63.2 % PWD,(iv) Helpdesk information centre:30.4% Elderly above 70,(v) Demo reconstruction:36.8% PWD,(vi) Reconstruction committee support:11.3% Elderly above 70 and (vii) Vocational training: 4.4% of single women; responded to expedite their reconstruction to complement the ODR housing reconstruction model through tailored STA activities.

- II.

Ability to build a house with STA program Intervention.

This outcome demonstrates the impact of STA program activities on the capacity of vulnerable beneficiaries to construct houses.

Table 4 presents responses from these beneficiaries, probing whether they could have independently built their houses without STA support.

Nearly 89% of surveyed participants indicated they would have needed help to construct a house independently.

Table 4.

Could you have built your house without STA Support?

Table 4.

Could you have built your house without STA Support?

| |

Vulnerable Categories |

Total |

| Single Women above 65 Years |

Elderly above 70 Years |

Person with disability (PWD) |

| Could you have built your house without STA support? |

No, I could not |

Count |

83 |

169 |

18 |

270 |

| % |

91.2% |

87.1% |

94.7% |

88.8% |

| Yes, I could |

Count |

8 |

25 |

1 |

34 |

| % |

8.8% |

12.9% |

5.3% |

11.2% |

| Total |

Count |

91 |

194 |

19 |

304 |

| % |

100.0% |

100.0% |

100.0% |

100.0% |

| Chi-Square Tests |

| |

Value |

df |

Asymp. Sig. (2-sided) |

| Pearson Chi-Square |

1.761a

|

2 |

0.415 |

Additionally,91.2 % of single women above 65 years, 87.1 % of elderly citizens above 70 years, and 94.7% of persons with disabilities (PWD) stated that they would not have been able to build on their own without STA support. The lack of a significant difference among the three vulnerable categories is indicated by a p-value of 0.415 (Accepted H1), suggesting a similar situation for all vulnerable groups.

- III.

Newly Reconstructed House Met Needs

The results in

Table 5 show that surveyed respondents responded to the statement

“Newly reconstructed house met needs” as follows on average in total: Strongly Agree: 22.2 %, Agree: 58.6%, Neither agree nor disagree: 3.3 %, Disagree: 10.9%, Strongly Disagree: 5.0%, with an average mean of 2.18, which is close to the Agree overall.

Table 5.

Newly Reconstructed House Met Needs.

Table 5.

Newly Reconstructed House Met Needs.

| |

Vulnerable Categories |

Total |

| Single Women above 65 Years |

Senior Citizen above 70 Years |

PWD |

| New reconstruction house met needs |

Strongly Agree |

Count |

18 |

46 |

3 |

67 |

| % |

19.8% |

24.0% |

15.8% |

22.2% |

| Agree |

Count |

59 |

107 |

11 |

177 |

| % |

64.8% |

55.7% |

57.9% |

58.6% |

| Neither agree or disagree |

Count |

4 |

5 |

1 |

10 |

| % |

4.4% |

2.6% |

5.3% |

3.3% |

| Disagree |

Count |

8 |

23 |

2 |

33 |

| % |

8.8% |

12.0% |

10.5% |

10.9% |

| Strongly Disagree |

Count |

2 |

11 |

2 |

15 |

| % |

2.2% |

5.7% |

10.5% |

5.0% |

| Total |

Count |

91 |

192 |

19 |

302 |

| % |

100.0% |

100.0% |

100.0% |

100.0% |

| Average Mean |

2.18 |

| Chi-Square Tests |

| |

Value |

Df |

Asymp. Sig. (2-sided) |

| Pearson Chi-Square |

5.956a

|

8 |

0.652 |

Table 5 indicates an overall positive response of 81 %, with 22% strongly agreeing and 59% agreeing that the newly reconstructed houses met their needs. There is no significant association among all vulnerable categories regarding the “New Reconstruction House met needs” program support, as the p-value is 0.652 (Accepted H2), suggesting unanimous agreement across all beneficiary groups.

- VI.

Effectiveness of Financial Grant

The below depicts the effectiveness of financial grants by the respondents, which was measured through the Likert scale (Highly effective=3, Effective =2, Less effective=1, Not effective=0). The average mean is 2.84 with a minimum of 1 and a maximum of 3, close to the highly effective. So, it is found that STA's role in supporting obtaining financial grants is highly effective for vulnerable beneficiaries.

The results in

Table 6 show that 84% of beneficiaries highly rated the government’s financial grant program, with 15.1% considering it effective and none perceiving it as ineffective. Only 0.7% found it less effective. The findings indicate a unanimous positive impact of financial grants, with no significant difference among vulnerable categories, as indicated by a p-value of 0.874 (Accepting H3).

Table 6.

Effectiveness of Financial Grant.

Table 6.

Effectiveness of Financial Grant.

| Effectiveness of Financial Grant |

Vulnerable Categories |

Total |

| Single Women above 65 Years |

Senior Citizen above 70 Years |

PWD |

| Financial Grant |

Less effective |

Count |

1 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

| % |

1.1% |

0.5% |

0.0% |

0.7% |

| Effective |

Count |

12 |

30 |

4 |

46 |

| % |

13.2% |

15.5% |

21.1% |

15.1% |

| Highly effective |

Count |

78 |

163 |

15 |

256 |

| % |

85.7% |

84.0% |

78.9% |

84.2% |

| Total |

Count |

91 |

194 |

19 |

304 |

| % |

100.0% |

100.0% |

100.0% |

100.0% |

| Average Mean |

2.84 |

| Chi-Square Tests |

| |

Value |

df |

Asymp. Sig. (2-sided) |

| Pearson Chi-Square |

1.223a

|

4 |

0.874 |

- VII.

Effectiveness of Technical Assistance

As surveyed respondents, the effectiveness of Technical Assistance is illustrated below, measured on a Likert scale (Highly effective=3, Effective =2, Less effective=1, Not effective=0). The average mean is 2.32, with a minimum mean of 1 and a maximum of 3, indicating close effectiveness. Therefore, it is concluded that STA effectively supports vulnerable beneficiaries in obtaining Technical Assistance.

The results in

Table 7 reveal that a minimal 2.3% of beneficiaries perceived technical assistance as less effective, while the vast majority (98%) found it effective. The findings affirm the equal distribution of the STA program among all vulnerable categories, including women, seniors, and persons with disabilities, with a P-value of 0.731 (Accepting H4), indicating unbiased support based on the humanitarian aid principle.

Table 7.

Effectiveness of Technical Assistance.

Table 7.

Effectiveness of Technical Assistance.

| Effectiveness of Technical Assistance |

Vulnerable Categories |

Total |

| Single Women above 65 Years |

Senior Citizen above 70 Years |

PWD |

| Technical Assistance |

Less effective |

Count |

1 |

5 |

1 |

7 |

| % |

1.1% |

2.6% |

5.3% |

2.3% |

| Effective |

Count |

61 |

119 |

11 |

191 |

| % |

67.0% |

61.7% |

57.9% |

63.0% |

| Highly effective |

Count |

29 |

69 |

7 |

105 |

| % |

31.9% |

35.8% |

36.8% |

34.7% |

| Total |

Count |

91 |

193 |

19 |

303 |

| % |

100.0% |

100.0% |

100.0% |

100.0% |

| Average Mean |

2.32 |

| Chi-Square Tests |

| |

Value |

Df |

Asymp. Sig. (2-sided) |

| Pearson Chi-Square |

2.026a

|

4 |

0.731 |

- VIII.

STA support in accessing financial grants from Banks and Financial Institutions (BFIs)

Table 8 presents survey results evaluating the contribution of STA activities to accessing financial grants from Banks and Financial Institutions (BFIs). Overall, the responses based on the Likert scale include (Strongly Agree= 1, Agree=2, Neither agree nor disagree=3, Disagree=4, Strongly Disagree=5) where data shows that Strongly agreed:33.3%, Agreed: 45.9%, Neither agreed no disagreed:3.6%, Disagreed:13.2% and Strongly Disagreed:4% with average mean is 2.09 which is close to the Agree in overall.

Table 8.

STA support in receiving tranches from Banks & Financial Institutions (BFIs).

Table 8.

STA support in receiving tranches from Banks & Financial Institutions (BFIs).

| |

Vulnerable Categories |

Total |

| Single Women above 65 Years |

Senior Citizen above 70 Years |

PWD |

| STA support in receiving trances form BFIs. |

Strongly Agree |

Count |

33 |

61 |

7 |

101 |

| % |

36.7% |

31.4% |

36.8% |

33.3% |

| Agree |

Count |

39 |

92 |

8 |

139 |

| % |

43.3% |

47.4% |

42.1% |

45.9% |

| Neither agree or disagree |

Count |

6 |

4 |

1 |

11 |

| % |

6.7% |

2.1% |

5.3% |

3.6% |

| Disagree |

Count |

8 |

29 |

3 |

40 |

| % |

8.9% |

14.9% |

15.8% |

13.2% |

| Strongly Disagree |

Count |

4 |

8 |

0 |

12 |

| % |

4.4% |

4.1% |

0.0% |

4.0% |

| Total |

Count |

90 |

194 |

19 |

303 |

| % |

100.0% |

100.0% |

100.0% |

100.0% |

| Average mean |

2.09 |

| Chi-Square Test |

| |

Value |

Df |

Asymp. Sig. (2-sided) |

| Pearson Chi-Square |

7.236a

|

8 |

0.511 |

- IX.

STA Activities Expedited Reconstruction

The following results illustrate the surveyed respondents’ views on how STA activities facilitated reconstruction, assessed on a Likert scale (Strongly agree= 1, Agree=2, Neither agree nor disagree=3, Disagree=4, Strongly Disagree=5). The overall average responses were strongly agreed: 25.8%, Agreed: 70.5%, disagreed: 2.3%, and strongly Disagree: 1.3 %, with an average mean of 1.83, close to Agree overall.

Table 9.

STA Expedited Reconstruction.

Table 9.

STA Expedited Reconstruction.

| |

Vulnerable Categories |

Total |

| Single Women above 65 Years |

Senior Citizen above 70 Years |

PWD |

| STA Activities Expedited Reconstruction |

Strongly Agree |

Count |

18 |

53 |

7 |

78 |

| % |

20.0% |

27.5% |

36.8% |

25.8% |

| Agree |

Count |

70 |

133 |

10 |

213 |

| % |

77.8% |

68.9% |

52.6% |

70.5% |

| Disagree |

Count |

2 |

4 |

1 |

7 |

| % |

2.2% |

2.1% |

5.3% |

2.3% |

| Strongly Disagree |

Count |

0 |

3 |

1 |

4 |

| % |

0.0% |

1.6% |

5.3% |

1.3% |

| Total |

Count |

90 |

193 |

19 |

302 |

| % |

100.0% |

100.0% |

100.0% |

100.0% |

| Average mean |

1.83 |

| Chi-Square Tests |

| |

Value |

Df |

Asymp. Sig. (2-sided) |

| Pearson Chi-Square |

8.139a

|

6 |

0.228 |

- X.

Modalities of STA Program Support Reception

Results from

Table 10 show that 77.6% of respondents, especially single women above 65 years (78.0%) and elderly above 70 years (77.3%), self-approached for STA program activities. Organizations approached a smaller percentage (9.8%),29.28% were recommended or referred, and 65.79% received support through the local community. Moreover, 4.93% were assisted by social mobilizers.

Table 10.

Modalities of STA Program Support Reception.

Table 10.

Modalities of STA Program Support Reception.

| How did you receive the program support? |

Vulnerable Categories |

Total |

| Single Women above 65 Years |

Senior Citizen above 70 Years |

PWD |

| Total |

Self-approached for the need of the program activities |

Count |

71 |

150 |

15 |

236 |

| % |

78.0% |

77.3% |

78.9% |

77.6% |

| Approached by organization |

Count |

6 |

13 |

1 |

20 |

| % |

6.6% |

6.7% |

5.3% |

9.80% |

| Recommended or referred |

Count |

21 |

61 |

7 |

89 |

| % |

23.1% |

31.4% |

36.8% |

29.28% |

| Local community |

Count |

61 |

124 |

15 |

200 |

| % |

67.0% |

63.9% |

78.9% |

65.79% |

| Social mobilizer |

Count |

5 |

9 |

1 |

15 |

| % |

5.5% |

4.6% |

5.3% |

4.93% |

| Total |

Count |

91 |

194 |

19 |

304 |

| Percentages and totals are based on respondents. |

| a. Dichotomy group tabulated at value 1. |

Results from

Table 10 show that approximately 78% of single women and around 77-79% of vulnerable individuals needed urgent support from the STA program intervention, leading them to self-approach for expediting reconstruction efforts. The findings suggest varied pathways for receiving program support, with a notable trend of self-initiation by vulnerable beneficiaries.

- XI.

Importance of STA program activities

Table 11 gauges the perceived importance of the STA program activities among different vulnerable categories measured on the Likert scale (Strongly agree 1, Agree=2, Neither agree nor disagree=3, Disagree=4, Strongly Disagree=5). Many respondents across all vulnerable categories agreed that the STA support program was crucial for their reconstruction efforts.

Table 11.

Importance of STA program activities.

Table 11.

Importance of STA program activities.

| |

Vulnerable Categories |

Total |

| Single Women above 65 Years |

Senior Citizen above 70 Years |

PWD |

| STA support program was very important for me |

Strongly Agree |

Count |

31 |

60 |

4 |

95 |

| % |

34.1% |

30.9% |

21.1% |

31.2% |

| Agree |

Count |

55 |

126 |

14 |

195 |

| % |

60.4% |

64.9% |

73.7% |

64.1% |

| Disagree |

Count |

1 |

7 |

1 |

9 |

| % |

1.1% |

3.6% |

5.3% |

3.0% |

| Strongly Disagree |

Count |

4 |

1 |

0 |

5 |

| % |

4.4% |

0.5% |

0.0% |

1.6% |

| Total |

Count |

91 |

194 |

19 |

304 |

| % |

100.0% |

100.0% |

100.0% |

100.0% |

| Average Mean |

1.80 |

| Chi-Square Tests |

| |

Value |

df |

Asymp. Sig. (2-sided) |

| Pearson Chi-Square |

9.037a

|

6 |

0.171 |

- XII.

Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) Awareness by STA program

Table 12 provides insights into Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) awareness among vulnerable categories in the STA program. Across single women above 65 years, senior citizens above 70 years, and persons with disabilities (PWD).

Table 12.

DRR Awareness by STA Program.

Table 12.

DRR Awareness by STA Program.

| |

Vulnerable Categories |

Total |

| Single Women above 65 Years |

Senior Citizen above 70 Years |

PWD |

| DRR Awareness |

Strongly Agree |

Count |

25 |

71 |

6 |

102 |

| % |

27.8% |

36.8% |

31.6% |

33.8% |

| Agree |

Count |

54 |

94 |

10 |

158 |

| % |

60.0% |

48.7% |

52.6% |

52.3% |

| Neither agree or disagree |

Count |

3 |

8 |

0 |

11 |

| % |

3.3% |

4.1% |

0.0% |

3.6% |

| Disagree |

Count |

3 |

11 |

2 |

16 |

| % |

3.3% |

5.7% |

10.5% |

5.3% |

| Strongly Disagree |

Count |

5 |

9 |

1 |

15 |

| % |

5.6% |

4.7% |

5.3% |

5.0% |

| Total |

Count |

90 |

193 |

19 |

302 |

| % |

100.0% |

100.0% |

100.0% |

100.0% |

| Average mean |

1.95 |

| Chi-Square Tests |

| |

Value |

Df |

Asymp. Sig. (2-sided) |

| Pearson Chi-Square |

5.648a

|

8 |

0.687 |

- XIII.

Effectiveness of the STA Program Activities

The table presents the effectiveness of the Socio-technical assistance (STA) program activities, focusing on vulnerable categories such as single women above 65, senior citizens above 70, and persons with disabilities (PWD).

- ▪

Financial Support: All three vulnerable categories show high percentages (99% to 100%) in acknowledging the effectiveness of financial support in their reconstruction.

- ▪

Technical Support: Over 90% in each vulnerable category perceive technical support as effective in aiding recovery.

- ▪

Accessible House: While there is a variation across categories, ranging from 70.3% to 78.9%, a substantial majority acknowledges housing accessibility as beneficial.

- ▪

Build Earthquake Resilient (EQ) House: A high percentage (94.7% to 96%) across vulnerable categories acknowledges the effectiveness of building earthquake-resilient houses.

- ▪

Improved Livelihood: The majority in each category (79.1% to 94.7%) recognize the program’s impact on enhancing their livelihoods.

- ▪

Training & Orientations: Strong positive perceptions (82.4% to 84.5%) indicate the importance of training and orientation in recovery.

- ▪

Sufficient Place to Live-In: Most respondents (73.6% to 89.5%) express satisfaction with providing sufficient living space.

- ▪

Enhanced Safety: Across all vulnerable categories, a significant proportion (84.6% to 89.5%) perceive the program as contributing to enhanced safety.

The survey reports unanimously demonstrate the remarkable success of program implementation in meeting the fundamental needs of vulnerable beneficiaries, significantly aiding their recovery efforts. The consistently high percentages across different program components underscore the program's effectiveness in comprehensively addressing the diverse needs of the identified vulnerable categories.

7. Result of Hypothesis Testing

| S. N |

Hypothesis |

P-Value Chi-Square Test |

Results |

| H1 |

There is no significant association between vulnerable categories and the likelihood of building a house with STA support |

0.415 (Table 4) |

Accepted |

| H2 |

There is no significant association between vulnerable categories and the level of agreement on whether newly reconstructed houses met their needs in the STA program. |

0.652 (Table 5) |

Accepted |

| H3 |

There is no significant association between vulnerable categories and the perceived effectiveness of Financial Grants in the STA program. |

0.874 (Table 6) |

Accepted |

| H4 |

There is no significant association between vulnerable categories and the perceived effectiveness of Technical Assistance in the STA program. |

0.731 (Table 7) |

Accepted |

| H5 |

There is no significant association between vulnerable categories and the level of agreement on STA support in receiving tranches from Banks and Financial Institutions (BFIs) |

0.511(Table 8) |

Accepted |

| H6 |

There is no significant association between vulnerable categories and the level of agreement on STA activities expediting reconstruction. |

0.228 (Table 9) |

Accepted |

| H7 |

There is no significant association between the vulnerable categories and the perceived importance of the STA program activities. |

0.171 (Table 11) |

Accepted |

| H8 |

There is no significant association between the vulnerable categories and the perceived DRR Awareness by the STA program. |

0.687 (Table 12) |

Accepted |

8. Discussion

The study reveals significant findings related to the effectiveness of Socio-Technical Assistance (STA) interventions in post-disaster reconstruction. The findings demonstrate substantial income increase for masons and a noteworthy inclusion of women in the workforce (

Table 3). Orientation and training efforts accelerated reconstruction by 75% (Build Change, 2014; Lamsal et al., 2020; Manindra Malla, 2020), with approximately 20% of the 755 recruited masons being women, also reported by other studies (The World Bank, 2020-2021). Furthermore, both governmental entitles significantly expedited reconstruction efforts, supported by various studies (Dhungel et al., 2019; Gouli et al., 2019; JICA, 2019a; Bishwakarma, 2020; The World Bank, 2020-2021; Rawal et al., 2021).

The role of tailored STA support for vulnerable beneficiaries is crucial, as it significantly contributes to socio-economic recovery and livelihood reinstatement (

Table 4),also revealed by other studies (Dhungel et al., 2019; Gouli et al., 2019; JICA, 2019a; The World Bank, 2021a; UNDP, 2021b; 2021c).Field survey results indicate that 89% of beneficiaries could not build their houses without focused STA program intervention, with over 97.1% findings it both practical and necessary, reinforcing the effectiveness and importance of such interventions, as supported by another study (Karki et al., 2020b; Manindra Malla, 2020). Similarly positive perceptions of reconstruction grants are highlighted, with over 90.59% of beneficiaries finding them easy and timely (

Table 5).A substantial portion of beneficiaries-initiated reconstruction promptly upon receiving the grant, aligning with FWLD's (2017) findings that more than 61% of beneficiaries initiated reconstruction promptly upon receiving the grant.

The importance of technical and financial assistance for knowledge transfer skills development in post-disaster reconstruction is emphasized (

Table 6 and 7). Prior study by Manindra Malla (2020) emphasized the importance of technical assistance by 92% and another study by Hülssiep et al. (2021) also evidenced the need of financial and technical assistance and access to finance by 94 % in April 2016 and 97% in June 2016 .This findings aligns with various project based reports underscoring the role of these elements in building resilience also revealed in other disaster contexts (Arshad & Athar, 2013; IFRC, 2018). These findings align with other project-based reports(JICA, 2019a; The World Bank, 2019; 2021a; NSET, 2023) and other project based studies (Dhungel et al., 2019; Karki et al., 2020b; Rawal et al., 2021). Previous research also highlighted enhanced financial access for disadvantaged segments due to post-earthquake housing reconstruction initiatives (Build Change, 2014; Bhusal et al., 2020).

STA’s contribution to imparting disaster resilience skills, creating employment opportunities, and supporting the Owner-Driven Reconstruction (ODR) approach to reinstate livelihoods is notable (

Table 8). The initiative is found to be imparting technical skills, creating employment opportunities for both men and women by project-based reports (IFRC, 2018; The World Bank, 2020).

STA activities expedited reconstruction, with an overall average agreed response of 96.30% (

Table 9).The implementation of STA resulted in a high construction compliance rate of 81 % validated by project based studies to validate the effectiveness (Gouli et al., 2019).The perceived need for the STA program by 77.6% of respondents is consistent with findings from other studies (

Table 10) (Dhungel et al., 2019; Gouli et al., 2019; Karki et al., 2020b).

Post-disaster reconstructed houses provide a safe and dignified shelter,serving as valuable assets and enhancing disaster reslience for beneficiaries (

Table 12).Similarly, another study by FWLD (2017) found that 80.32 % of female-owner beneficiaries perceived the effectiveness of earthquake resilience.

The effectiveness of the STA program combined with technical and financial assistance in accelerating reconstruction efforts is emphasized, aligning with the principle of ‘No One Left Behind” (

Table 11 and

Table 13) (Dhungel et al., 2019; Gouli et al., 2019; Scott Wilson Nepal, 2019; Rawal et al., 2021; The World Bank, 2021b).Consistent positive responses from beneficiaries regarding the STA program’s satisfaction and effectiveness are supported by previous research (Karki et al., 2020a; Bhusal & Bhattarai, 2023). Additionally,92 % reported that STA activities supported building back better (Manindra Malla, 2020). Vulnerable earthquake beneficiaries also provided positive responses regarding friendly house design in the study area of the Gorkha district (women: 80.49%, Children: 61.46%, Persons with Disability: 43.90% and Elderly: 52.20% (FWLD, 2017).Therefore, this research study evidences the effectiveness of STA program intervention, as revealed by prior project-based studies and reports.

This study contributes substantially to post-disaster humanitarian literature by addressing a critical knowledge gap in the shelter and settlement response, specifically examining Nepal’s private housing reconstruction from the earthquake epicentre region from vulnerable households’ perspectives eight years after a disaster as there is limited independent academic research. The study empirically evidences the significant impact of the STA program combined with the Owner-Driven Reconstruction (ODR) model, particularly for individuals struggling with self-reconstruction; this study offers groundbreaking insights from Nepal's world’s largest ODR housing recovery initiative. It also highlights that the ODR model, though widely preferred as a ‘global reconstruction strategy’ in low-income countries, requires tailored approaches rather than a universal application. Furthermore, the research aligns with the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goal (UN SDG: Goal 11), offering valuable insights for fostering sustainable cities and communities in disaster-prone regions.

9. Limitations

The study faced several limitations, including a confined number of collected variables, limited data scale values, and a focus on one district in rural housing reconstruction and three municipalities out of the 14 highly affected districts. Additionally, participant responses were influenced by their understanding of the questionnaire, education level and mood during completion. Future research could enhance generalizability by increasing the sample size to include 31 earthquake-affected regions, thereby capturing diverse perceptions of vulnerable beneficiaries. Further investigations in 14 ‘highly affected’ and 17 ‘less affected’ districts, focusing on vulnerable or non-recipients of STA interventions or those solely relying on ODR, can be explored using qualitative study to consider specific needs of families, challenges and detailed experiences with the reconstruction process will provide a deeper understanding of these dynamics. This study focused on a particular episode of the disaster; the broader issues, such as environmental degradation, climate change, and socio-economic vulnerability, will be incorporated in the next paper and our long-term research study on the relationship between disaster and economic development. To address this, we will broaden the scope and diversify the sample size in future studies.

10. Conclusion

In conclusion, this research examined the effectiveness of Socio-Technical Assistance (STA) in aiding vulnerable beneficiaries during post-disaster reconstruction programs. The study revealed that 302 out of 304 respondents surveyed in the field (99.3%) successfully completed their reconstruction efforts, highlighting positive outcomes in various aspects such as financial support, technical assistance, accessible housing, earthquake-resilient construction, improved livelihoods, training, sufficient living spaces, and enhanced safety. The predominant trend of self-help approach by beneficiaries highlighted their urgency in seeking assistance. The research underscores the vital role of STA interventions in accelerating reconstruction and addressing specific needs, as is evident by overwhelmingly positive participant responses. The perceived importance of STA and positive Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) awareness underscores its significance for immediate recovery and long-term resilience. Overall, the study highlights the effectiveness of the Owner-Driven Reconstruction (ODR) approach with tailored STA activities.

The research highlights the weakness of relying solely on ODR indicating challenges faced by vulnerable beneficiaries who were unable in independently driving the reconstruction of houses on their own (see

Table 1). Moreover, it sheds light on the limited evidence from the perspectives of vulnerable recipients, stressing the need to customize STA modalities in future post-disaster rural private housing reconstruction endeavors. These insights provide valuable guidance for post-disaster humanitarian responses and advocate for strategic policy considerations, promoting the integration of STA into comprehensive recovery strategies and fostering awareness of Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) for future sustainable recovery efforts to build resilient communities.

Author Contributions

The paper was conceived by N.P.B, is based on her unpublished PhD thesis from the Faculty of Business, Law and Politics, University of Hull, UK. She developed the methodological approach, conducted the literature review, and gathered information from various sources. K. B and F.W, who supervised the thesis, provided guidance during its production, revised and edited the manuscript, contributed to re-writing sections, and sourced additional information and images. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Ethical clearance was obtained from the University of Hull for the field research and informed consent from respondents of the survey.

Data Availability Statement

Data used in this paper will be available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Declaration of Interests

We affirm the accuracy of the provided information and confirm the absence of any actual, potential, or perceived conflicts of interest. No competing financial interests or personal relationships could be perceived as influencing the work presented in this paper.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Completion of House Reconstruction.

Table A1.

Completion of House Reconstruction.

| Q22.COMPLETED OR NOT |

| |

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

| Valid |

Under reconstruction |

2 |

.7 |

.7 |

.7 |

| Completed |

302 |

99.3 |

99.3 |

100.0 |

| Total |

304 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

|

Table A2.

Opening of Bank Account.

Table A2.

Opening of Bank Account.

| Q18.BANK A/C |

| |

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

| Valid |

After Earthquake |

196 |

64.5 |

64.5 |

64.5 |

| Before Earthquake |

108 |

35.5 |

35.5 |

100.0 |

| Total |

304 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

|

Table A3.

Living in the Newly Reconstructed House.

Table A3.

Living in the Newly Reconstructed House.

| Q25.LIVE IN OR NOT |

| |

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

| Valid |

No |

3 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

| Yes |

300 |

98.7 |

99.0 |

100.0 |

| Total |

303 |

99.7 |

100.0 |

|

| Missing |

System |

1 |

.3 |

|

|

| Total |

304 |

100.0 |

|

|

References

- Ade Bilau, A. & Witt, E. (2016) An analysis of issues for the management of post-disaster housing reconstruction. International journal of strategic property management, 20(3), 265-276. [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, S., Shrestha, S. K., Aryal, S. & Bhattarai, R. (2021) Analysis of Owner Driven Approach of Housing Reconstruction after Gorkha Earthquake 2015: A Case Study of Dhunibeshi Municipality, Dhading.

- ADRC (2020) Nepal: A brief country profile on Disaster Risk Reduction and Management. Available online: https://www.adrc.asia/countryreport/NPL/2019/Nepal_CR2019B.pdf [Accessed 16th January 2023].

- Ahmed, I. (2017a) A Partnership-Based Community Engagement Approach to Recovery of Flood-Affected Communities in Bangladesh, Community Engagement in Post-Disaster RecoveryRoutledge, 22-36. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, I. (2017b) Resilient housing reconstruction in the developing world, Urban Planning for Disaster RecoveryElsevier, 171-188.

- Alam, K. (2010) Bangladesh: Can large actors overcome the absence of state will? Building Back Better, 10(9781780440064.011).

- Andrew, S. A., Arlikatti, S., Long, L. C. & Kendra, J. M. (2013) The effect of housing assistance arrangements on household recovery: an empirical test of donor-assisted and owner-driven approaches. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 28(1), 17-34.

- Arshad, S. & Athar, S. (2013) Rural housing reconstruction program post-2005 earthquake: Learning from the Pakistan Experience: A manual for post-disaster housing program managers.

- Arunatilake, N. (2018) Post-disaster housing: Lessons learnt from the 2004 Tsunami of Sri Lanka. The Asian Tsunami and Post-Disaster Aid, 211-232.

- Baker, J., Rawal, V., Brown, P., Chiles, P. & Mohamed, E. (2010) Tsunami displacement: Lessons for climate adaptation programming: Findings on shelter reconstruction. USAgency for international development (USAID). Washigton: DC, USA.

- Barakat, S. (2003) Housing reconstruction after conflict and disaster. Humanitarian Policy Group, Network Papers, 43, 1-40.

- Barenstein, J. D. (2006a) Housing reconstruction in post-earthquake Gujarat. HPN Network Paper(54).

- Barenstein, J. D. (2006b) Housing reconstruction in post-earthquake Gujarat, a comparative analysis. Humanitarian Practice Network, Network Paper, 54.

- Barenstein, J. D. (2012) The role of communities in post-disaster reconstruction. A call for owner-driven approaches. Tafter Journal. Esperienze e Strumenti per cultura e territorio(50).

- Barenstein, J. D., Jha, A., Phelps, P., Pittet, D. & Sena, S. (2010) Safer Homes, Stronger Communities. A Handbook for Reconstruction After Natural Disasters. The World Bank/GFDRR.

- Bates, F. L. & Peacock, W. G. (1989) Long term recovery. International Journal of Mass Emergencies & Disasters, 7(3), 349-365.

- Bhusal, N. P., Aryal, B. & Lamsal, R. (2020) NRA HAS ENHANCED ACCESS TO FINANCIAL SERVICES. Available online: http://www.nra.gov.np/np/resources/details/izJxuxWH3okrr2FG_2uE0Gz4eIZbXBPLZoiXeEv7EBQ [Accessed 7th December].

- Bhusal, N. P. & Bhattarai, K. (2023) Assessing Satisfaction levels of the Earthquake Beneficiaries with the Post-disaster Private Housing Reconstruction Programme: Evidence from Nepal. Journal of Development Economics and Finance, 4(2), 277-308.

- Bilau, A., Witt, E. & Lill, I. (2018) Practice Framework for the Management of Post-Disaster Housing Reconstruction Programmes. Sustainability (Basel, Switzerland), 10(11), 3929. [CrossRef]

- Bilau, A. A., Witt, E. & Lill, I. (2015) A Framework for Managing Post-disaster Housing Reconstruction. Procedia Economics and Finance, 21, 313-320. [CrossRef]

- Bishwakarma, K. (2020) Final Evaluation Report of ‘Resilient Reconstruction through Building Back Better focussed on the most vulnerable communities in districts most severely affected by 2015 earthquake’.

- Bothara, J. K., Dhakal, R., Dizhur, D. & Ingham, J. (2016) The challenges of housing reconstruction after the April 2015 Gorkha, Nepal earthquake. Technical Journal of Nepal Engineers' Association, Special Issue on Gorkha Earthquake 2015, XLIII-EC30, 1, 121-134.

- Build Change (2014) Homeowner-Driven Housing Reconstruction and Retrofitting in Haiti -Lessons Learned, 4 Years After the Earthquake. Available online: https://buildchange.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Haiti-HODR-Lessons-Learned-Build-Change-.pdf [Accessed 17th December 2023].

- Caritas (2019) Earthquake Affected Communities Realize A Holistic Recovery. Available online: https://www.caritasnepal.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/for-website_Case-Study_2019-September-MM.pdf [Accessed 22nd November 2023].

- Charles, J. a. I., JA (2020) Ten Years After Haiti’s Earthquake: A Decade of Aftershocks and Unkept Promises. Available online: https://pulitzercenter.org/stories/ten-years-after-haitis-earthquake-decade-aftershocks-and-unkept-promises [Accessed 14th November 2023].

- Clay, D. C., Molla, D. & Habtewold, D. (1999) Food aid targeting in Ethiopia: A study of who needs it and who gets it. Food policy, 24(4), 391-409.

- De Juan, A., Pierskalla, J. & Schwarz, E. (2020) Natural disasters, aid distribution, and social conflict – Micro-level evidence from the 2015 earthquake in Nepal. World Development, 126, N.PAG-N.PAG.

- DesRoches, R., Comerio, M., Eberhard, M., Mooney, W. & Rix, G. J. (2011) Overview of the 2010 Haiti earthquake. Earthquake Spectra, 27(1_suppl1), 1-21.

- Dhungana, N. & Cornish, F. (2021) Beyond performance and protocols: early responders' experiences of multiple accountability demands in the response to the 2015 Nepal earthquake. Disasters, 45(1), 224-248.

- Dhungel, R., Shrestha, S. N., Guragain, R., Gouli, M. R., Baskota, A. & Hadkhale, B. (2019) Socio-technical module in assistance: Promoting resilient reconstruction in the wake of a disaster. Journal of Nepal Geological Society, 58, 139-144. [CrossRef]

- Eichenauer, V. Z., Fuchs, A., Kunze, S. & Strobl, E. (2020) Distortions in aid allocation of United Nations flash appeals: Evidence from the 2015 Nepal earthquake. World development, 136, 105023. [CrossRef]

- ERRA (2009) Social Impact Assessment Report. Available online: https://cms.ndma.gov.pk/storage/app/public/publications/October2020/bMMr7e87hV5F4Ojt5F8N.pdf [Accessed 17th November 2023].

- FWLD (2017) Gender Equality and Social Incusion in Post-Earthquake Reconstruction. Kathmandusa,Nepal: FWLD. Available online: https://fwld.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Gender-Equality-and-Social-Inclusion.pdf [Accessed 10th November 2023].

- Ganapati, N. E. & Mukherji, A. (2014) Out of sync: World Bank funding for housing recovery, postdisaster planning, and participation. Natural Hazards Review, 15(1), 58-73.

- Gangwar, S. & Thakur, B. (2018) Disaster, Displacement and Rehabilitation A Case Study of Kosi Floods in North Bihar. National Geographical Journal of India, 64(1-2), 76-92.

- Global Shelter Cluster (2019) Shelter Projects 2017-2018.

- Gouli, M. R., Dhungel, R., Baskota, A., Hadkhale, B. & Khatiwada, P. (2019) POST EARTHQUAKE RECONSTRUCTION IN NEPAL: ITS COMMUNAL IMPACTS AND ESSENCE OF SOCIO-TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE.

- He, L., Aitchison, J. C., Hussey, K., Wei, Y. & Lo, A. (2018) Accumulation of vulnerabilities in the aftermath of the 2015 Nepal earthquake: Household displacement, livelihood changes and recovery challenges. International journal of disaster risk reduction, 31, 68-75.

- Hidellage, V. & Usoof, A. (2010) Scaling-up people-centred reconstruction: Lessons from Sri Lanka’s post-tsunami owner-driven programme. Building Back Better, 77.

- Hillier, D. & Nightingale, K. (2013). How disasters disrupt development.

- HRRP (2017a) Core Socio-Technical Assistance Package.

- HRRP (2017b) Core Socio-Technical Assistance Package. Available online: https://www.preventionweb.net/files/63753_6lpmjtyz5rc9bqfioljx20171115.pdf [Accessed 11th September].

- HRRP (2019) The Path to Housing Recovery: Nepal Earthquake 2015: Housing Reconstruction. Kathmandu: Available online: https://www.hrrpnepal.org/uploads/media/HRRPtimelinebooklet-April2019_20190425195635.pdf [Accessed 6th March 2022].

- HRRP (2020) THE PATH TO HOUSING RECOVERY,NEPAL EARTHQUAKE 2015: HOUSING RECONSTRUCTION. Available online: https://www.hrrpnepal.org/uploads/media/HRRPtimelinebooklet-December2020_final_SM_min_20201218155954.pdf [Accessed 11th September 2022].

- Hülssiep, M., Thaler, T. & Fuchs, S. (2021) The impact of humanitarian assistance on post-disaster social vulnerabilities: some early reflections on the Nepal earthquake in 2015. Disasters, 45(3), 577-603. [CrossRef]

- Hunnarshala Foundation (n.d,) Owner Driven Reconstruction Collaborative (ODRC),Nepal. Available online: http://www.hunnarshala.org/owner-driven-reconstruction-collaborative-nepal.html [Accessed 12th September 2023].

- Hyndman, J. & Hyndman, J. (2011) Dual disasters: Humanitarian aid after the 2004 tsunami.Kumarian Press Sterling, VA.

- IFRC (2010) Owner-Driven Housing Reconstruction Guidelines. Available online: https://sheltercluster.s3.eu-central-1.amazonaws.com/public/docs/ODHR%20Guidelines.pdf [Accessed 11th August 2023].

- IFRC (2018) Post disaster reconstruction.

- Ingirige, B., Haigh, R., Malalgoda, C. & Palliyaguru, R. (2008) EXPLORING GOOD PRACTICE KNOWLEDGE TRANSFER RELATED TO POST TSUNAMI HOUSING (RE-)CONSTRUCTION IN SRI LANKA. Journal of Construction in Developing Countries, 13(2), 21-42.

- Jackson, R., Fitzpatrick, D. & Man Singh, P. (2016) Building Back Right: Ensuring equality in land rights and reconstruction in Nepal.

- Jha, A. K. (2010) Safer homes, stronger communities: a handbook for reconstructing after natural disasters.World Bank Publications.

- Jha, A. K. & Duyne, J. E. (2010) Safer homes, stronger communities: a handbook for reconstructing after natural disasters. Washington, D.C: Available online: https://go.exlibris.link/fSnF8mDM [Accessed 9th September 2023].

- JICA (2019a) Building on community strength for “Earthquake-Resilient Houses” to Nepal. Available online: https://www.jica.go.jp/Resource/english/news/field/2019/20191007_01.html [Accessed 5th July 2022].

- JICA (2019b) Transitional Project Implementation Support For Emergency Reconstruction Projects.

- Karki, T. B., Lamsal, R. & Bhusal, N. P. (2020a) Role of Socio-Technical Assistance (STA) in Private Housing Reconstruction for Vulnerable Community.

- Karki, T. B., Lamsal, R. & Poudel, N. (2020b) Role of Socio-Technical Assistance (STA) in Private Housing Reconstruction for Vulnerable Community (A case study of Okhaldhunga District, Nepal). Nepal Journal of Multidisciplinary Research, 3(3), 106-114.

- Karunasena, G. & Rameezdeen, R. (2010a) Post-disaster housing reconstruction: Comparative study of donor vs owner-driven approaches. International Journal of Disaster Resilience in the Built Environment, 1(2), 173-191.

- Karunasena, G. & Rameezdeen, R. (2010b) Post-disaster housing reconstruction: Comparative study of donor vs owner-driven approaches. International Journal of Disaster Resilience in the Built Environment.

- Lam, L. M. (2022) Against the trend: evaluation of Nepal's owner-driven reconstruction program. Housing studies, ahead-of-print(ahead-of-print), 1-28. [CrossRef]

- Lam, L. M., Khanna, V. & Kuipers, R. (2017) Disaster governance and challenges in a rural Nepali community: notes from future village NGO. HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies, 37(2), 11.

- Lamsal, R., Karki, D. & Poudel, N. (2020) Importance of Socio-Technical Assistance (STA) for Vulnerable Community: Special Case of Okhaldhunga District. Rebuilding Nepal, 24-25.

- Lyons, M. (2009) Building Back Better: The Large-Scale Impact of Small-Scale Approaches to Reconstruction. World Development, 37(2), 385-398. [CrossRef]

- Manindra Malla, A. K. (2020) Effectiveness of Holistic Socio-technical and Financial Support to Enable Socio-economic Vulnerable Households to Build Earthquake Resistant Houses. VIKAS: A Journal of Development Special Issue Nepal’s Post-Earthquake Recovery and Reconstruction, 2, pp. 142–164.

- Maynard, V., Parker, E. & Twigg, J. (2017) The effectiveness and efficiency of interventions supporting shelter self-recovery following humanitarian crises.Oxfam.

- MDTF (2021) NEPAL EARTHQUAKE HOUSING RECONSTRUCTION MULTI-DONOR TRUST FUND-How are the houses being rebuilt?

- Mishra, P. K. (2006) The Kutch Earthquake--2001: Recollections, Lessons, and Insights.National Institute of Disaster Management.

- MoHA (2017) Nepal Disaster Report 2017: The Road to Sendai.

- Mumtaz, H., Mughal, S. H., Stephenson, M. & Bothara, J. K. (2008) The challenges of reconstruction after the October 2005 Kashmir earthquake. Bulletin of the New Zealand Society for Earthquake Engineering, 41(2), 68-82.

- Nagami, K., Miyano, T., Nishimura, N., Toriumi, Y., Tsukahara, N. & Nakamura, A. (2021) Practical Approaches to Build Back Better with Inclusive Recovery from Earthquake Disasters: A Discussion Based on the 2015 Nepal Earthquake Recovery Project by JICA.

- Nigg, J. M. (1995) Disaster recovery as a social process.

- NPC (2015) Post Disaster Disaster Needs Assessment(Nepal Earthquake 2015). Available online: https://www.npc.gov.np/images/category/PDNA_volume_BFinalVersion.pdf [Accessed 4th September 2023].

- NRA (2016) Post Disaster Recovery Framework (PDRF). Available online: https://www.np.undp.org/content/nepal/en/home/library/crisis_prevention_and_recovery/post-disaster-recovery-framework-pdrf2016-2020.html.

- NRA (2021) NRA HAS MADE 93 PERCENT PROGRESS IN PRIVATE HOUSING RECONSTRUCTION. Available online: : http://nra.gov.np/en/news/details/Lt9HEgNaQYQSxGCpEp1FUQJzLEGYesQgzm44Ku6MCVs [Accessed 10th September].

- NRA (2024) Progress of Private Housing. Available online: http://www.nra.gov.np/en/mapdistrict/datavisualization [Accessed 21st January ].

- NSET (2021) Baliyo Ghar Program ‘A Contribution Towards Disaster Resilient Nepal’ Report on socio-technical assistance for housing reconstruction after 2015 Gorkha Earthquake.

- NSET (2023) ‘Baliyo Ghar’-the Housing Reconstruction Technical Assistance Program Completes,Direct Socio-Technical support provided to rebuild 63700 houses. Available online: https://www.nset.org.np/nset2012/index.php/event/eventdetail/eventid-587 [Accessed 12th December ].

- Ophiyandri, T., Amaratunga, R. & Pathirage, C. (2010) Community based post disaster housing reconstruction: Indonesian perspective.

- Peacock, W. G., Dash, N. & Zhang, Y. (2007) Sheltering and housing recovery following disaster, Handbook of disaster researchSpringer, 258-274.

- Peacock, W. G., Dash, N., Zhang, Y. & Van Zandt, S. (2018) Post-disaster sheltering, temporary housing and permanent housing recovery. Handbook of disaster research, 569-594.

- Price, G. & Bhatt, M. (2009) The role of the affected state in humanitarian action: A case study on India. Humanitarian Policy Group, HPG Working Paper,[cited April 2009].

- Proudlock, K., Ramalingam, B. & Sandison, P. (2009) Improving humanitarian impact assessment: bridging theory and practice. 8th Review of Humanitarian Action: Performance, Impact and Innovation.

- Puri, J., Aladysheva, A., Iversen, V., Ghorpade, Y. & Brück, T. (2014) What methods may be used in impact evaluations of humanitarian assistance? St. Louis: Available online: https://go.exlibris.link/r6yx42G5 [Accessed 11th September 2023].

- Quzai, U. (2010) Pakistan: Implementing people-centred reconstruction in urban and rural areas. Building Back Better, 113.

- Ramalingam, B., Mitchell, J., Borton, J. & Smart, K. (2009) Counting what counts: performance and effectiveness in the humanitarian sector. Review of Humanitarian Action.

- Ratnasooriya, H. A., Samarawickrama, S. P. & Imamura, F. (2007) Post tsunami recovery process in Sri Lanka. Journal of Natural Disaster Science, 29(1), 21-28. [CrossRef]

- Ratnayake, R. & Rameezdeen, R. (2008) Post disaster housing reconstruction: Comparative study of donor driven vs. owner driven approach. Women’s career advancement and training & development in the, 1067.

- Rawal, V., Bothara, J., Pradhan, P., Narasimhan, R. & Singh, V. (2021) Inclusion of the poor and vulnerable: Learning from post-earthquake housing reconstruction in Nepal. Progress in Disaster Science, 10, 100162.

- Sanderson, D. & Ramalingam, B. (2015) NEPAL EARTHQUAKE RESPONSE: Lessons for operational agencies. The active learning network for accountability and performance in Humanitarian action ALNAP.

- Sandvik, K. B. (2017) Now is the time to deliver: looking for humanitarian innovation’s theory of change. Journal of International Humanitarian Action, 2(1), 1-11.

- Schilderman, T. (2004) Adapting traditional shelter for disaster mitigation and reconstruction: experiences with community-based approaches. Building research & information, 32(5), 414-426.

- Scott Wilson Nepal (2019) Hamro Ghar: Overcoming barriers to Shelter Reconstruction-Leave No One Behind. Available online: https://swnepal.com.np/project/hamro-ghar-overcoming-barriers-to-shelter-reconstruction-leave-no-one-behind/ [Accessed 12th July ].

- Sharma, K., Apil, K., Subedi, M. & Pokharel, B. (2018) Post disaster reconstruction after 2015 Gorkha earthquake: challenges and influencing factors. Journal of the Institute of Engineering, 14(1), 52-63.

- Shelter Projects (2010) Natural Disaster: Haiti 2010-Earthquake-overview.

- Tafti, M. T. & Tomlinson, R. (2015) Best practice post-disaster housing and livelihood recovery interventions: winners and losers. International development planning review, 37(2), 165-185. [CrossRef]

- Taheri Tafti, M. (2012) Limitations of the owner-driven model in post-disaster housing reconstruction in urban settlements, procedings of the International conference on Disaster Management (IIIRR), Kumamoto.

- The World Bank (2012) Indonesia: A Reconstruction Chapter Ends Eight Years after the Tsunami Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2012/12/26/indonesia-reconstruction-chapter-ends-eight-years-after-the-tsunami [Accessed 10th December].

- The World Bank (2015) Bihar Kosi Flood Recovery Porject (P122096). Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/272441468290962267/pdf/India-Bihar-Kosi-Flood-Recovery-Project-P122096-Implementation-Status-Results-Report-Sequence-09.pdf [Accessed 15th November 2023].

- The World Bank (2019) Safer Housing Reconstruction in Nepal Empowers the Marginalized,Especially Women. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/results/2019/09/10/safer-housing-reconstruction-empowers-the-marginalized-especially-women.

- The World Bank (2020) In Nepal’s post-earthquake reconstruction, women masons are breaking gender barriers. Available online: https://blogs.worldbank.org/endpovertyinsouthasia/nepals-post-earthquake-reconstruction-women-masons-are-breaking-gender#:~:text=Post%2Dearthquake%20reconstruction%2C%20including%20those,up%20masonry%20as%20a%20vocation. [Accessed 1st September 2023].

- The World Bank (2020-2021) Annual Report July 2020-June 2021.

- The World Bank (2021a) Nepal Earthquake Housing Reconstruction Multi-Donor Trust Fund. Available online: https://www.nepalhousingreconstruction.org/sites/nuh/files/2021-10/mdtf-annualreport-2021-web.pdf [Accessed 15th September 2023].

- The World Bank (2021b) Nepal strives to leave no one behind in earthquake reconstruction Available online: https://blogs.worldbank.org/endpovertyinsouthasia/nepal-strives-leave-no-one-behind-earthquake-reconstruction [Accessed 11th July 2022].

- Torrente, N. d. (2013) The Relevance and Effectiveness of Humanitarian Aid: Reflections about the Relationship between Providers and Recipients. Social research, 80(2), 607-634.

- Twigg, J. (2006) Technology, post-disaster housing reconstruction and livelihood security. BH Centre (Ed.), Disaster studies working paper no, 15.

- UNDP (2019) Mid-term Review of Socio-Technical Facilitation Services to Housing Reconstruction in Gorkha District (GOI funded). Available online: https://erc.undp.org/evaluation/evaluations/detail/12420 [Accessed 6th August].

- UNDP (2021a) Comphrensive Disaster Risk Management Programme(CDRMP),Final Evaluation of Socio-technical Facilication Services to Nepal Housing Reconstruction Project (NHRP). Available online: https://erc.undp.org/evaluation/documents/download/19345 [Accessed 12th July 2023].