Submitted:

23 June 2024

Posted:

24 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

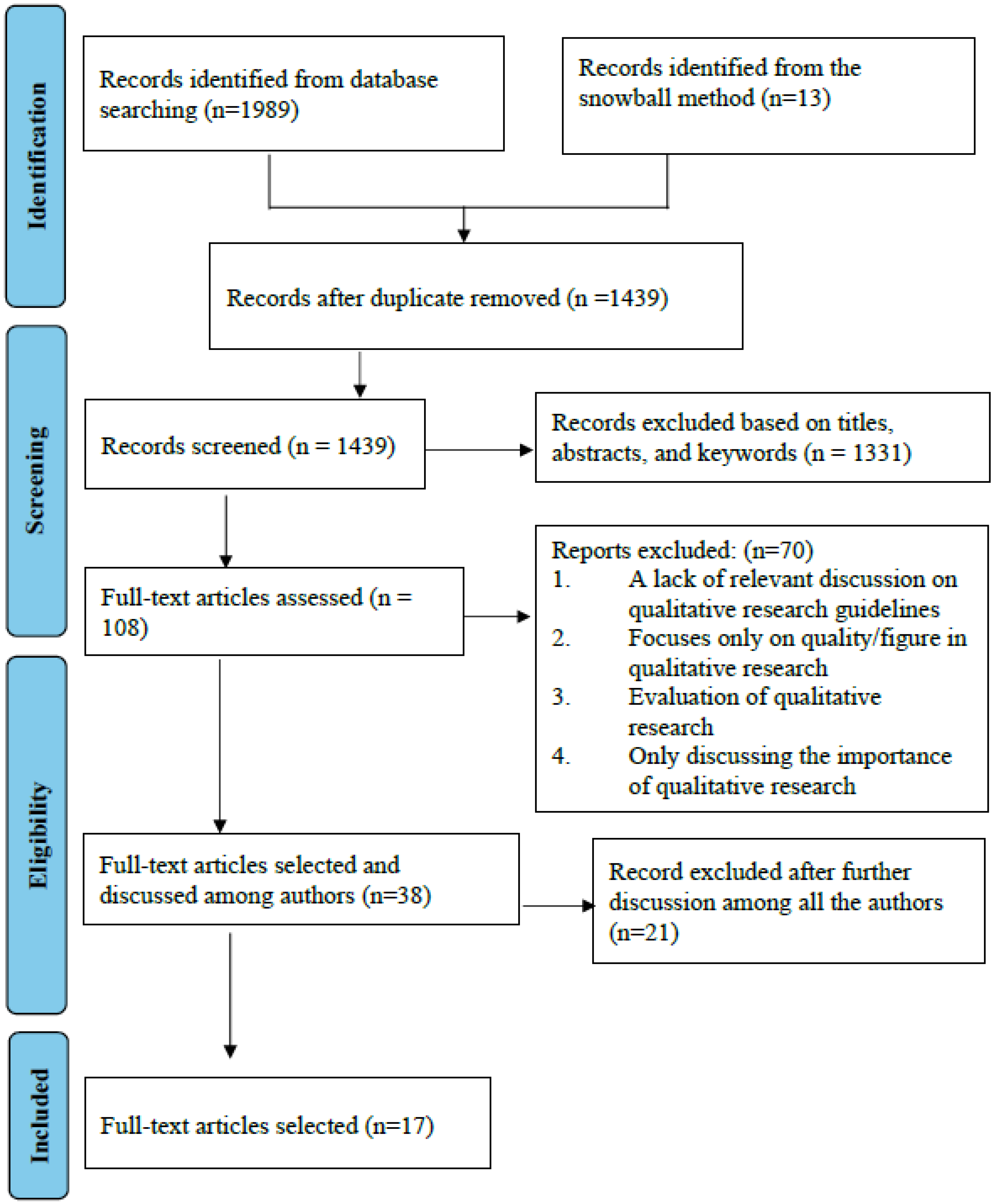

2. Methods

3. Result

3.1. Quality Assessment of Articles

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Malterud, K. Developing and promoting qualitative methods in general practice research: Lessons learnt and strategies convened. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health 2022, 50, 1024–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tenny, S.; Brannan, J.M.; Brannan, G.D. Qualitative Study; StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelf, 2022.

- Renjith, V.; Yesodharan, R.; Noronha, J.A.; Ladd, E.; George, A. Qualitative methods in health care research. International journal of preventive medicine 2021, 12, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryman, A. Social research methods; Oxford university press, 2012.

- McIlvennan, C.K.; Morris, M.A.; Guetterman, T.C.; Matlock, D.D.; Curry, L. Qualitative methodology in cardiovascular outcomes research: a contemporary look. Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes 2019, 12, e005828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grossoehme, D.H. Overview of qualitative research. Journal of health care chaplaincy 2014, 20, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandão, C.; Ribeiro, J.; Costa, A.P. Qualitative research: where do we stand now? SciELO Brasil: 2018; Vol. 23, pp 4-4.

- Peditto, K. Reporting qualitative research: Standards, challenges, and implications for health design. HERD: Health Environments Research & Design Journal 2018, 11, 16–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mays, N.; Pope, C. Quality in qualitative research. Qualitative research in health care 2020, 211–233. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, J.L.; Adkins, D.; Chauvin, S. A review of the quality indicators of rigor in qualitative research. American journal of pharmaceutical education 2020, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dossett, L.A.; Kaji, A.H.; Cochran, A. SRQR and COREQ reporting guidelines for qualitative studies. JAMA surgery 2021, 156, 875–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godinho, M.A.; Gudi, N.; Milkowska, M.; Murthy, S.; Bailey, A.; Nair, N.S. Completeness of reporting in Indian qualitative public health research: a systematic review of 20 years of literature. Journal of Public Health 2019, 41, 405–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flemming, K.; Booth, A.; Hannes, K.; Cargo, M.; Noyes, J. Cochrane Qualitative and Implementation Methods Group guidance series—paper 6: reporting guidelines for qualitative, implementation, and process evaluation evidence syntheses. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2018, 97, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCarthy, A.; Kirtley, S.; de Beyer, J.A.; Altman, D.G.; Simera, I. Reporting guidelines for oncology research: helping to maximise the impact of your research. British Journal of Cancer 2018, 118, 619–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tai, J.; Ajjawi, R. Undertaking and reporting qualitative research. The clinical teacher 2016, 13, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buus, N.; Perron, A. The quality of quality criteria: Replicating the development of the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ). International journal of nursing studies 2020, 102, 103452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International journal for quality in health care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, B.C.; Harris, I.B.; Beckman, T.J.; Reed, D.A.; Cook, D.A. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Academic medicine 2014, 89, 1245–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, M.; Daugherty, C.; Khallouq, B.B.; Maugans, T. Critical assessment of pediatric neurosurgery patient/parent educational information obtained via the Internet. Journal of Neurosurgery: Pediatrics 2018, 21, 535–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Research Guides: Evaluating Sources: The CRAAP Test. https://researchguides.ben.edu/source-evaluation. (accessed on 9 June 2024).

- France, E.F.; Cunningham, M.; Ring, N.; Uny, I.; Duncan, E.A.; Jepson, R.G.; Maxwell, M.; Roberts, R.J.; Turley, R.L.; Booth, A. Improving reporting of meta-ethnography: the eMERGe reporting guidance. BMC medical research methodology 2019, 19, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batten, J.; Brackett, A. Ensuring rigor in systematic reviews: Part 6, reporting guidelines. Heart & Lung 2022, 52, 22–25. [Google Scholar]

- Cronin, P.; Rawson, J.V. Review of research reporting guidelines for radiology researchers. Academic Radiology 2016, 23, 537–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florczak, K.L. Reflexivity: Should it be mandated for qualitative reporting? Nursing Science Quarterly 2021, 34, 352–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blignault, I.; Ritchie, J. Revealing the wood and the trees: reporting qualitative research. Health Promotion Journal of Australia 2009, 20, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coast, J.; Al-Janabi, H.; Sutton, E.J.; Horrocks, S.A.; Vosper, A.J.; Swancutt, D.R.; Flynn, T.N. Using qualitative methods for attribute development for discrete choice experiments: issues and recommendations. Health economics 2012, 21, 730–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levitt, H.M.; Bamberg, M.; Creswell, J.W.; Frost, D.M.; Josselson, R.; Suárez-Orozco, C. Journal article reporting standards for qualitative primary, qualitative meta-analytic, and mixed methods research in psychology: The APA Publications and Communications Board task force report. American Psychologist 2018, 73, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misiak, M.; Kurpas, D. Checklists for reporting research in Advances in Clinical and Experimental Medicine: How to choose a proper one for your manuscript? Advances in Clinical and Experimental Medicine: Official Organ Wroclaw Medical University 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, O.A.; Pinson, J.A.; Dennett, A.; Williams, C.; Davis, A.; Snowdon, D.A. Allied health assistants' perspectives of their role in healthcare settings: A qualitative study. Health & Social Care in the Community 2022, 30, e4684–e4693. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson, A.; Jordan, Z.; Lockwood, C.; Aromataris, E. Notions of quality and standards for qualitative research reporting. International Journal of Nursing Practice 2015, 21, 670–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, J. How to peer review a qualitative manuscript. Peer Review in Health Sciences. Edited by: Godlee F, Jefferson T. London: BMJ Books 2003, 219–235. [Google Scholar]

- Salzmann-Erikson, M. IMPAD-22: A checklist for authors of qualitative nursing research manuscripts. Nurse education today 2013, 33, 1295–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollin, I.L.; Craig, B.M.; Coast, J.; Beusterien, K.; Vass, C.; DiSantostefano, R.; Peay, H. Reporting formative qualitative research to support the development of quantitative preference study protocols and corresponding survey instruments: guidelines for authors and reviewers. The Patient-Patient-Centered Outcomes Research 2020, 13, 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zachariah, R.; Abrahamyan, A.; Rust, S.; Thekkur, P.; Khogali, M.; Kumar, A.M.; Davtyan, H.; Satyanarayana, S.; Shewade, H.D.; Delamou, A. Quality, Equity and Partnerships in Mixed Methods and Qualitative Research during Seven Years of Implementing the Structured Operational Research and Training Initiative in 18 Countries. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease 2022, 7, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Flemming, K.; McInnes, E.; Oliver, S.; Craig, J. Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC medical research methodology 2012, 12, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulz, K.F.; Altman, D.G.; Moher, D. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. Journal of Pharmacology and pharmacotherapeutics 2010, 1, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kline, R.B. Becoming a behavioral science researcher: A guide to producing research that matters; Guilford Press, 2008.

- Maxwell, J.A. Qualitative research design: An interactive approach; Sage publications, 2012.

- Nguyen, T.N.M.; Whitehead, L.; Dermody, G.; Saunders, R. The use of theory in qualitative research: Challenges, development of a framework and exemplar. Journal of advanced nursing 2022, 78, e21–e28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative research & evaluation methods: Integrating theory and practice; Sage publications, 2015.

- Turcotte-Tremblay, A.-M.; Mc Sween-Cadieux, E. A reflection on the challenge of protecting confidentiality of participants while disseminating research results locally. BMC medical ethics 2018, 19, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morse, J.M. Critical analysis of strategies for determining rigor in qualitative inquiry. Qualitative health research 2015, 25, 1212–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morse, J.M.; Barrett, M.; Mayan, M.; Olson, K.; Spiers, J. Verification strategies for establishing reliability and validity in qualitative research. International journal of qualitative methods 2002, 1, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles Matthew, B.; Huberman, A.M.; Saldana, J. Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook. Sage Publications: 2014.

- Charmaz, K. Constructing grounded theory; sage, 2014.

- Altman, D.G.; Simera, I. Using reporting guidelines effectively to ensure good reporting of health research. Guidelines for reporting health research: a user's manual 2014, 32–40. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S.; Wyant, D.C.; Fraser, M.W. Author guidelines for manuscripts reporting on qualitative research. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research 2016, 7, 405–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tate, R.L.; Douglas, J. Use of reporting guidelines in scientific writing: PRISMA, CONSORT, STROBE, STARD and other resources. Brain Impairment 2011, 12, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowan, M.; Huston, P. Qualitative research articles: information for authors and peer reviewers. Cmaj 1997, 157, 1442–1446. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. International journal of surgery 2021, 88, 105906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C. Presenting and evaluating qualitative research. American journal of pharmaceutical education 2010, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Tulder, M.; Furlan, A.; Bombardier, C.; Bouter, L.; Editorial Board of the Cochrane Collaboration Back Review Group. Updated method guidelines for systematic reviews in the cochrane collaboration back review group. Spine 2003, 28, 1290–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duran, R.P.; Eisenhart, M.A.; Erickson, F.D.; Grant, C.A.; Green, J.L.; Hedges, L.V.; Schneider, B. Standards for reporting on empirical social science research in AERA publications: American Educational Research Association. Educational Researcher 2006, 35, 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Bavdekar, S.B. Enhance the value of a research paper: Choosing the right references and writing them accurately. Journal of the Association of Physicians of India 2016, 64, 66. [Google Scholar]

- Malterud, K. Qualitative research: standards, challenges, and guidelines. The lancet 2001, 358, 483–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| ARTICLES AND YEARS | France et al. (2019) [21] |

Battenand Brackett (2022) [22] |

Cronin and Rawson (2016) [23] |

Florczak (2021) [24] |

Blignault and Ritchie (2009) [25] |

Coast et al. (2012) [26] |

Levitt et al. (2018) [27] |

Misiak and Kurpas (2022) [28] |

King (2022) [29] |

Pearson et al. (2015) [30] |

Clark (2003) [31] |

Salzmann-Erikson (2013) [32] |

O'Brien et al. (2014) [18] |

Hollin et al. (2020) [33] |

Zachariah et al. (2022) [34] |

Tong et al. (2012) [35] |

Tong et al. (2007) [17] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CURRENCY | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| RELEVANCE | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 |

| AUTHORITY | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| ACCURACY | 6 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 6 |

| PURPOSE | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Total | 24 | 21 | 23 | 22 | 18 | 23 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 19 | 20 | 23 | 25 | 25 | 23 | 25 | 25 |

| Author and Year | Journal Name | Title | Objectives | Method | Finding / Conclusion/ Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| France et al. (2019) [21] |

BMC Medical Research Methodology |

Improving reporting of meta-ethnography: The eMERGe reporting guidance |

Provide guidance to improve the completeness and clarity of meta-ethnography reporting. |

(1) A methodological systematic review of guidance for meta-ethnography conduct and reporting; (2) A review and audit of published meta-ethnographies to identify good practice principles; (3) International, multidisciplinary consensus-building processes to agree guidance content; (4) Innovative development of the guidance and explanatory notes. |

19 reporting criteria and accompanying detailed guidance |

| Batten and Brackett (2022) [22] |

Heart & Lung, The journal of cardiopulmonary and acute care | Ensuring rigor in systematic reviews: Part 6, reporting guidelines | Summarizing PRISMA, MOOSE, ENTREQ, systematic review reporting guidelines | Review | PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) is a key guideline updated in 2020. It includes a 27-item checklist covering title, abstract, introduction, methods, results, discussion, and additional information. It applies to all study designs, not just randomized control trials, ensuring comprehensive research transparency. MOOSE (Meta-analyses of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) is the guideline for synthesizing observational studies, which are crucial for assessing harm, including diverse populations, and reporting effectiveness. The 35-item checklist includes introduction, methods, results, discussion, and conclusion, similar to PRISMA but with specific details unique to observational studies. ENTREQ (Enhanced Transparency in Reporting the Synthesis of Qualitative Research) is the guideline for synthesizing qualitative studies, often called a meta-synthesis. It provides a 21-item checklist covering the synthesis aim, methods (search, data extraction, coding), results, and discussion, ensuring thorough and transparent reporting. |

| Cronin and Rawson (2016) [23] |

Academic Radiology | Review of Research Reporting Guidelines for Radiology Researchers |

To increase awareness of the radiology community of the available resources to enable researchers to produce scientific articles with a high standard of reporting of the research content and with a clear writing style |

To review the following study designs: diagnostic and prognostic studies, reliability and agreement studies, observational studies, experimental studies, quality improvement studies, qualitative research, health informatics, systematic reviews and meta-analyses, economic evaluations, mixed methods studies; and study protocols are discussed, as well as the reporting of statistical analysis. |

Complete review of the key EQUATOR reporting guidelines for radiology. |

| Florczak (2021) [24] |

SAGE | Reflexivity: Should It Be Mandated for Qualitative Reporting? |

Reflexivity and its importance to the process of qualitative research | Research issue | Reflexivity is important in evaluating qualitative studies. |

| Blignault and Ritchie (2009) [25] |

Health of Promotion- Journal of Australia | Revealing the wood and the trees: reporting qualitative research |

To provide a general guide to presenting qualitative research for publication in a way that has meaning for authors and readers is acceptable to editors and reviewers and meets the criteria for high standards of qualitative research reporting across the board. | Discussing the writing of all sections of an article, placing particular emphasis on how the author might best present findings, and illustrating his points with examples drawn from previous issues of this Journal. | Reporting qualitative research involves sharing both the process and the findings, that is, revealing both the wood and the trees. |

| Coast et al. (2012) [26] |

Health Economics | Using qualitative methods for attribute development for discrete choice experiments: issues and recommendations |

This paper explores issues associated with developing attributes for DCEs and contrasts different qualitative approaches. |

The paper draws on eight studies, four developed attributes for measures, and four developed attributes for more ad hoc policy questions. |

The theoretical framework for random utility theory and the need for attributes that are neither too close to the latent construct nor too intrinsic to people’s personality. The need to think about attribute development as a two-stage process. involving conceptual development followed by refinement of language to convey the intended meaning. The difficulty in resolving tensions inherent in the reductiveness of condensing complex and nuanced qualitative findings into precise terms. The comparison of alternative qualitative approaches suggests that the nature of data collection will depend both on the characteristics of the question and the availability of existing qualitative information. |

| Levitt et al. (2018) [27] |

American Psychologist | Journal Article Reporting Standards for Qualitative Primary, Qualitative Meta-Analytic, and Mixed Methods Research in Psychology: The APA Publications and Communications Board Task Force Report | To form recommendations for journals and publications using APA style. | A working group of APA was formed. A literature review was performed on qualitative research reporting standards before discussion and development of the standards. | Journal Article Reporting Standards for Qualitative Research. Qualitative Meta-Analysis Article Reporting Standards. Mixed-Methods Reporting Standards. |

| Misiak and Kurpas (2022) [28] |

Advances in Clinical and Experimental Medicine, | Checklists for reporting research in Advances in Clinical and Experimental Medicine: How to choose a proper one for your manuscript? | To provide an overview of the most frequently used checklists used to publish papers in Clinical and Experimental Medicine, Support authors in choosing a checklist | Presentation of 8 checklists from the EQUATOR website |

8 checklists compared. Checklist should be used to improve the manuscript. Equator website to choose a checklist. Choosing cheklist before start writing the paper Choice of checklist based on type of article. |

| King (2022) [29] |

Research in Nursing & Health | Two sets of qualitative research reporting guidelines: An analysis of the shortfalls | Aspects of the guidelines are discussed regarding their influence on the quality of qualitative health research | Review |

Although COREQ providing a comprehensive framework, guidelines might unintentionally compromise the quality and rigor of qualitative research due to their overly prescriptive nature. Despite encouraging rigorous and high-quality research in SRQR, guidelines need regular reassessment and updating to remain relevant and methodologically appropriate, akin to clinical guidelines. |

| Pearson et al. (2015) [30] |

International Journal of Nursing Practice | Notions of quality and standards for qualitative research reporting | Explore the possibility of developing a framework for authors of journals to report the results of qualitative studies to improve the quality of research. | Discussion | Standards of reporting Qualitative Studies must be promoted by high-quality journals to improve qualitative research. |

| Clark (2003) [31] |

Peer Review in Health Sciences | How to peer review a qualitative manuscript | Synthesis of quality criteria for qualitative research and summary of RATS | Synthesis | The quality of qualitative research may be compromised due to peer review demands that are misguided and uninformed. |

| Salzmann-Erikson (2013) [32] |

Nurse Education today | IMPAD-22: A checklist for authors of qualitative nursing research manuscripts | Developing a checklist for authors writing a qualitative nursing research manuscript (focus methods). | Review | 4 categories identified 1)Ingress and Methodology; 2)Participants; 3)Approval; 4)Data: Collection and Management 22 item checklist created. |

| O'Brien et al. (2014) [18] |

Academic Medicine | Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research: A Synthesis of Recommendations |

To formulate and define standards for reporting qualitative research while preserving the requisite flexibility to accommodate various paradigms, approaches, and methods. | Qualitative reporting guideline | SRQR consists of 21 checklists for reporting qualitative studies. |

| Hollin et al. (2020) [33] |

Tropical medicine and infectious disease | Reporting Formative Qualitative Research to Support the Development of Quantitative Preference Study Protocols and Corresponding Survey Instruments: Guidelines for Authors and Reviewers. | To improve the frequency and quality of reporting, we developed guidelines for reporting this type of research | Guidelines for Authors and Reviewers | The guidelines have five components: introductory material (4 domains); methods (12); results/findings (2); discussion (2); and other (2) |

| Zachariah et al. (2022) [34] |

Tropical medicine and infectious disease | Quality, Equity, and Partnerships in Mixed Methods and Qualitative Research during Seven Years of Implementing the Structured Operational Research and Training Initiative in 18 Countries |

To assess the publication characteristics and quality of reporting of qualitative and mixed-method studies from the Structured Operational Research and Training Initiative (SORT IT), a global partnership for operational research capacity building | Review | SORT IT plays an important role in ensuring the quality of evidence for decision-making to improve public health. |

| Tong et al. (2012) [35] |

BMC Medical Research Methodology | Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ | To develop a framework for reporting the synthesis of qualitative health research | Reporting the synthesis of qualitative research | The Enhancing Transparency in reporting the Synthesis of Qualitative Research (ENTREQ) statement consists of 21 items grouped into five main domains: introduction, methods and methodology, literature search and selection, appraisal, and synthesis of findings. |

| Tong et al. (2007) [17] |

International Journal for Quality in Health Care; | Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups |

To develop a checklist for explicit and comprehensive reporting of qualitative studies (in-depth interviews and focus groups) | Qualitative reporting guideline | 32 checklist consisting of (i) research team and reflexivity, (ii) study design, and (iii) data analysis and reporting. |

| ARTICLES | France et al. (2019) [21] |

Batten and Brackett (2022) [22] |

Chronic and Rawson (2016) [23] |

Florczak (2021) [24] |

Blignault and Ritchie (2009) [25] |

Coast et al. (2012) [26] |

Levitt et al. (2018) [27] |

Misiak and Kurpas (2022) [28] |

King (2022) [29] |

Pearson et al. (2015) [30] |

Clark (2003) [31] |

Salzmann-Erikson (2013) [32] |

O'Brien et al. (2014) [18] |

Hollin et al. (2020) [33] |

Zachariah et al. (2022) [34] |

Tong et al. (2012) [35] |

Tong et al. (2007) [17] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Title of the paper | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||||||

| Abstract | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||

| Introduction | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||

| Methodology | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Trustworthiness | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||

| Ethical consideration | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||

| Results | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||

| Discussion | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||

| Conclusion | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||||

| Strength and limitation | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||

| Recommendation | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||||

| Funding | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||||||

| Reference | ✔ | ||||||||||||||||

| Conflict of interest | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Topic | Description | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Title of the paper | ● Draws and attracts the reader and entails precisely what the paper covers; must be of relevance to intext content and precise. ● Includes type of study |

|

| 2. Abstract | ● Key elements of research including background, introduction, purpose, methodology, results, and conclusion. ● Under the abstract to include keywords. |

|

| 3. Introduction | ● Aim/objectives and purpose of the study. ● Relevance/ justification of research question, / connection to existing knowledge ● Problem statement /rational ● Describing existing knowledge |

|

| 4. Methodology | ● Research design/theoretical framework/Research Paradigm ● Rationale for chosen methodology. ● Study population (Sampling technique, study site, sample size and characteristics, inclusion and exclusion criteria ● Data collection (Data collection technique/methods (e.g Indepth interviews, focus group discussions (FGDs)), data collection tools, field notes, audio recording, video recording, data saturation, period of data collection, timing of interview, repeated interviews, interview guide). ● Data analysis and data management (Transcription, software, coding, theme generation, coding tree, number of data coders, participant checking and feedback (returning of transcripts to participants), triangulation, data security, data anonymity, changes in methodology). ● Reflexivity and researcher's characteristics (researchers’ participants relationship). ● Reporting guidelines used in reporting the study. ● Transparency in all processes. |

|

| 5. Trustworthiness | ● How it is achieved, which techniques were used? ● Transparency and credibility. ● Member checking through transcription and triangulation. ● Congruence between methodology and interpretation of results. |

|

| 6. Ethical consideration | ● Ethical Clearance and ethical approval: Document to be available per request. ● Participant's confidentiality and anonymity. ● Informed consent and procedure of taking informed consent. |

|

| 7. Results | ● Summary and clear statement of findings ● Research findings ● Major and minor themes ● Narration, quotes, field notes ● Diagrams, box, photographs, video links (clear presentation of findings) |

|

| 8. Discussion | ● Any biases (selection bias, publication bias, heterogenity) ● Interpretation of study results. ● Summary of major findings and comparison with existing literature and theory. ● Alternative explanation of findings. ● Implication, transferability, strength, and limitation of study contribution to the field. |

|

| 9. Conclusion | ● Describing implications ● Conclusion should come from analysis and interpretation. |

|

| 10. Strength and limitation | ● Strength and limitations ● How valuable are the study results? |

|

| 11. Recommendation | ● Recommendation for further studies and to the field | |

| 12. Funding | ● Source of funding and other support received during the study process. ● Role of funders in data collection, interpretation, and reporting Funding source (financial and nonfinancial support). ● Financial support for authorship or publication. |

|

| 13. Reference | ● Describe the information sources used/Citations. ● Appendix |

|

| 14. Conflict of interest | ● Potential influence on the study and how it was managed. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).