1. Introduction

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, adopted by all United Nations Member States in 2015, provides the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)–an urgent call for action by all countries [

1]. SDG 11 stipulates–“

Make cities and human settlements inclusive, stage any restrictions on the availability of materials or information. New methods

safe, resilient and sustainable”. Among the points of this goal are two that are closely related to urban design:

11.7 By 2030, provide universal access to safe, inclusive and accessible, green and public spaces, in particular for women and children, older persons and persons with disabilities.

11.7.1 Average share of the built-up area of cities that is open space for public use for all, by sex, age and persons with disabilities.

Thus universal and easy access to safe and inclusive open public green spaces is crucial in all neighborhoods. Safe and inclusive open public green spaces are understood as everyday places that unite the qualities of therapeutic landscapes to influence people’s physical, mental, and spiritual healing [

2]. They are open and welcoming to everyone, including people with special needs [

3]. Inclusive open public green spaces are designed according to the principles of universal design: Equitable Use, Flexibility in Use, Simple and Intuitive Use, Perceptible Information, Tolerance for Error, Low Physical Effort, and Appropriate Size and Space for Approach and Use [

4].

For all the Stakeholders the most interesting is the practical approach. The major focus of this study is how to implement this goal in practice in urban planning and design. Are there examples of good practices that can serve as guidelines for urban planning and renewal? There is a gap in research evidence therefore this study was undertaken.

The history of urban planning encompasses various attempts to create a health-promoting urban design [

5]. The historic old towns were built to satisfy all dwellers’ needs within walking distance. However, numerous factors influenced that urban tissue over time, e.g., the changes in town planning paradigm, economic pressures, and modern living standards. Today, the modern eco-neighborhoods are implementing the current state of knowledge [

6,

7,

8]. The concept of the open urban block coined by Christian de Portzamparc led to the creation of a new urban block -Macrolot, characterized by the increased presence of green spaces, direct sunlight, and fresh air [

9,

10,

11]. The concept of Macrolot was successfully utilized in the last twenty years in various operations of urban renewal in France: e.g., ZAC Paris Rive Gauche, ZAC Seguin-Rives de Seine à Boulogne, ZAC Paris Clichy Batignolles, ZAC Ginko Bordeaux, ZAC Docks de Saint-Ouen, ZAC Lyon Confluences. ZAC Jackques Coeur-Port Marianne Montpelier, etc [

10]. The research question was: does the concept of Macrolot facilitate the creation of easy access to safe and inclusive open public green spaces in France and other countries?

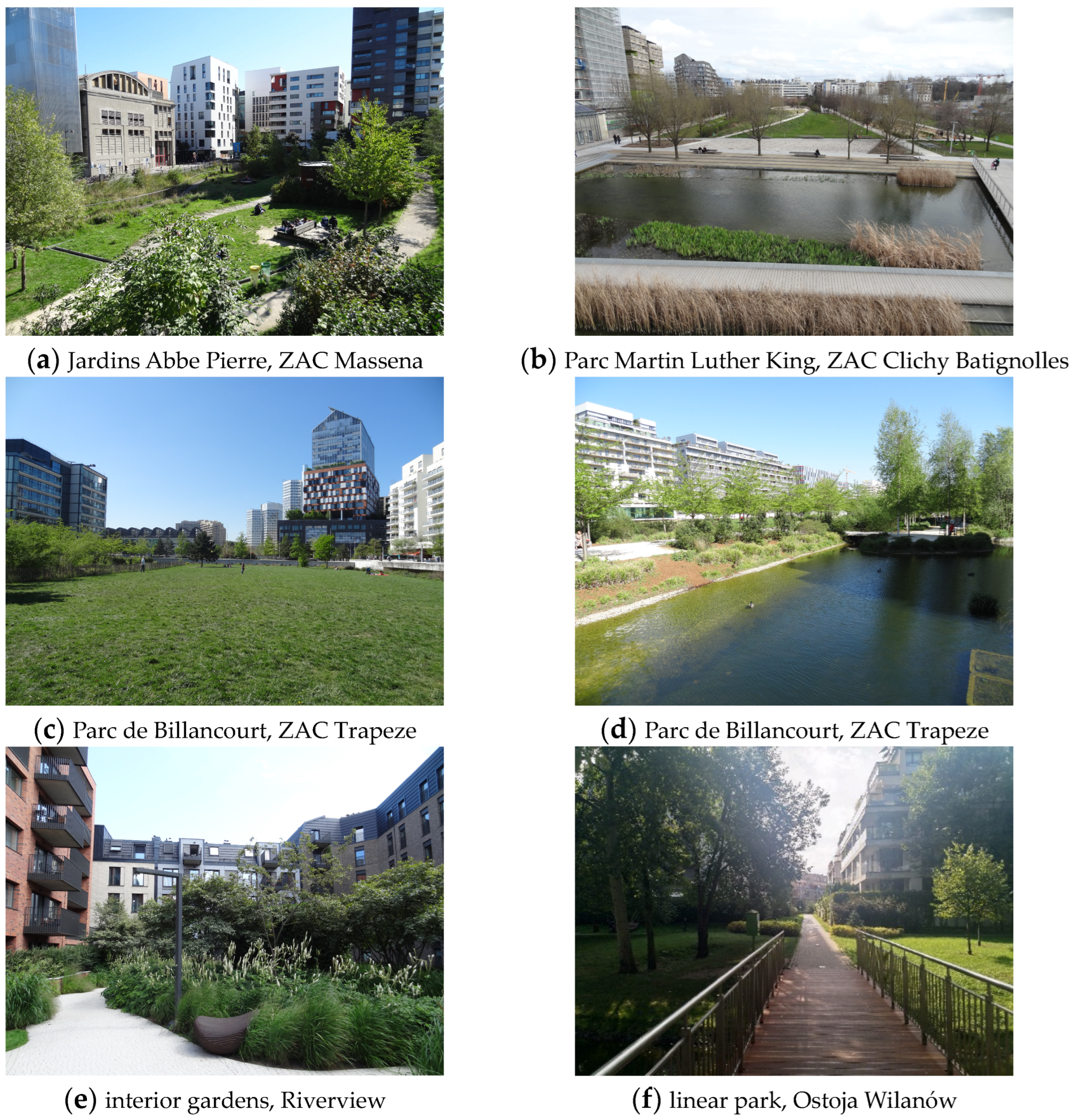

To answer this question in this study five modern neighborhoods: three eco-neighborhoods from France ZAC Massena, ZAC Trapeze, and ZAC Clichy-Batignolles and two award-winning developments from Poland–Riverview and Ostoja Wilanów–examples of the implementation of the open urban block (

Table 1). The focus is on urban morphology and the concept of open urban block coined by Chrisitan de Portzamparc.

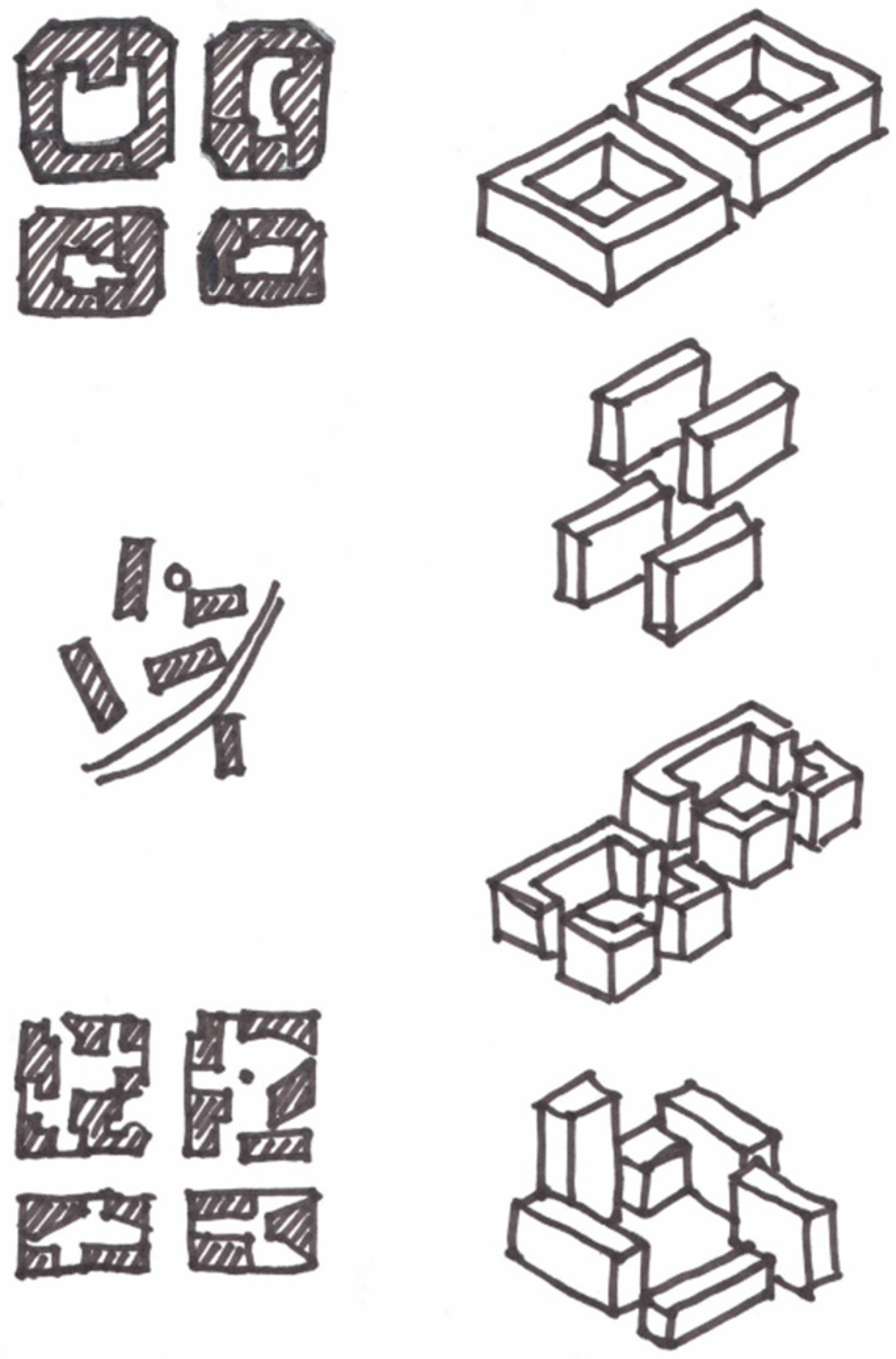

1.1. Open Urban Block. Macrolot

Christian de Portzamparc established the theory of III phases of urban development–la ville de l’Age I, la ville de l’Age II and la ville de l’Age III [

11,

12].

La ville de l’Age I–represents the historic urban form with streets, plazas, and urban blocks. The hierarchy of public and private spaces is clearly defined. The emphasis is on the space between buildings.

La ville de l’Age II is a functional city constructed according to the Athens Charter [

13,

14,

15] with a dominant form of building volumetry and surrounding spaces. The city is organized around the volumes and blocks, not around the human being. The old structures are being replaced all at the same time, there is no space or time for organic growth. The individual inhabitants are losing control over the space and time [

16,

17,

18].

La ville de l’Age III is not an idealistic theory. It is more about the new approach where the city is not seeking homogeneity but rather promotes diversity, architectural and functional variety, and individual treatment of each place. Portzamparc’s theory (1994) was based on Le Corbusier’s ideas but differs concerning the most unecological and unhuman concepts of a city destined to become a well-functioning machine. La ville de l’Age III is a place where the relations between human beings and the environment are the most important [

9,

10,

11].

The concept La ville de l’Age III coined by Christian de Portzamparc led to the creation of a new urban form–an open urban block, which was characterized by the increased presence of green spaces and diversified architectural features (Figure 4).

The first “open block” was implemented in the design of Hautes Formes in 1975 [

19].

That concept was evaluated towards the Macrolot, which facilitated the implementation of public parks in dense urban tissues. Back in the ‘90s’ Christian de Portzamparc proposed an urban block with various heights and fragmented perimeter. His urban blocks were more sculptured. They are referred to as the next generation of urban planning, which is a joining point between the historic city and the XIX century Haussmann block, modern city, and open planning (

Figure 1) [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

19]. This type of urban block is connected more with architectural design than with public space design. Portzamparc is using the world: l’île architecturale (architectural island) [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

19].

One of the noticeable characteristics of open blocks is the architectural variety. There are no long, uniform repetitious forms of blocks of flats. Each building is designed by a different architect. All buildings vary in height, width, material, and shape. Each of the blocks is coordinated and developed by a different construction firm.

The diversity encompasses mixed-use and various social groups of users and inhabitants. What is important–parking space, facilities, and open green space are also shared, therefore it is possible to create larger public parks inside the open block. There are open blocks that are constructed around the centrally located park or garden–e.g., Clichy-Batignolles, le Trapeze.

The concept was turned into Macrolot, which unites a few project managers to build one urban complex with various functions and uses, and sometimes designed by numerous architects [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. Macrolot represents the return of traditional town planning, with urban blocks. The concept of open urban block is related to sustainable urban form and the compact city [

20,

21,

22,

23].

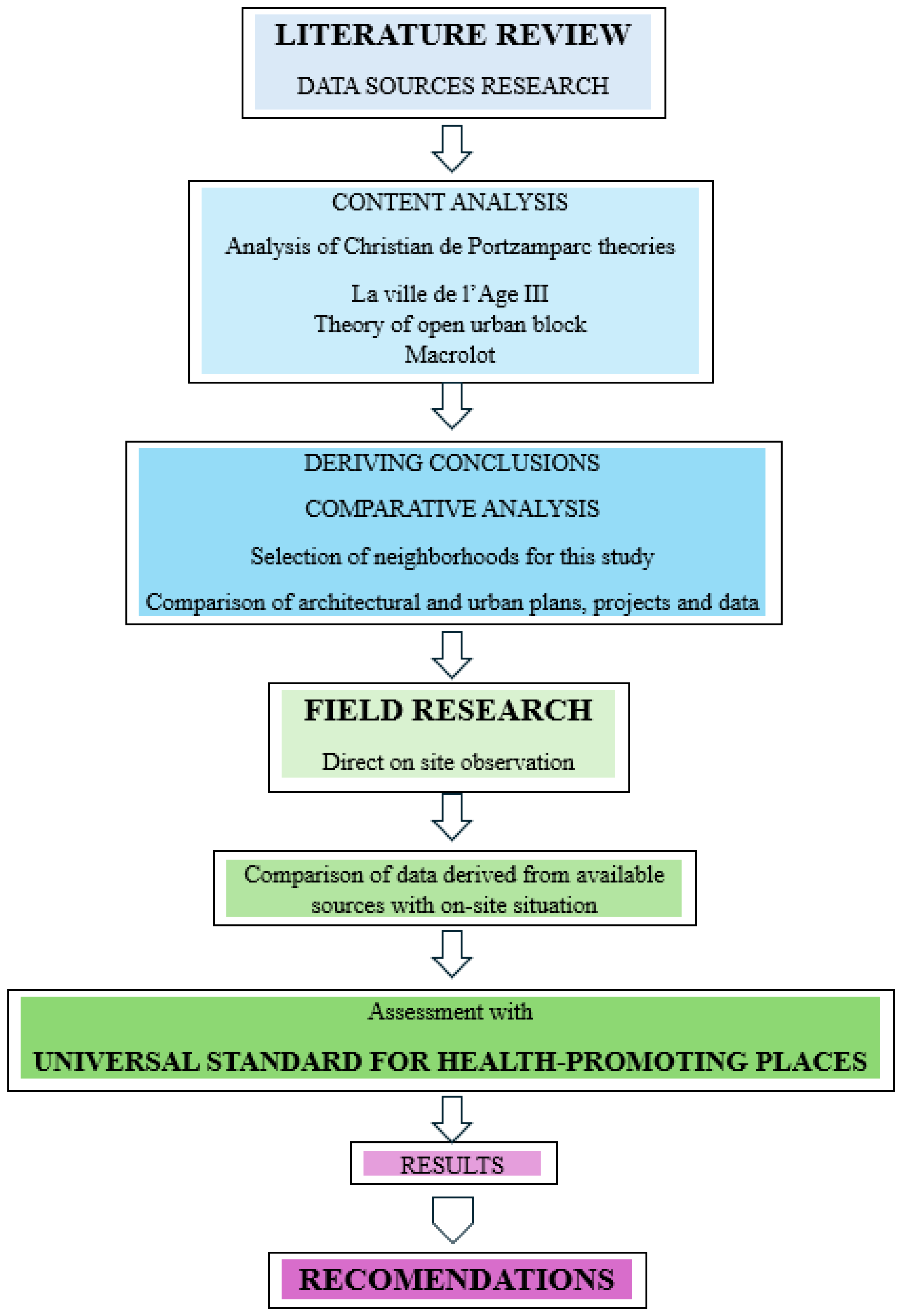

2. Materials & Methods

The methods included literature review, content analysis and comparative analysis (

Figure 2).

Literature studies encompassed data sources research. The content analysis involved deriving conclusions based on specific characteristics and extracting arguments and examples from recorded sources to support observations. Sources of existing data were used to address specific research problems [

24]. The comparative analysis included a comparison of architectural and urban plans, projects, and data from completed neighborhoods.

The field study visits focused on the comparison of data derived from available sources with on-site situations, and assessment using the author’s tool–UNIVERSAL STANDARD FOR HEALTH-PROMOTING PLACES (Table 3,

Appendix A).

The author’s original method was used to assess the qualities of open public green spaces in selected neighborhoods. This tool was developed using the triangulation of research evidence and field studies [

6,

8,

25]. The tool facilitates the assessment of attributes of therapeutic parks and access to the park (

Appendix A). The method of assessment was described in detail in the example of Rahway River Park [

25]. This tool can be used as an audit tool to determine the potential health-promoting qualities of urban places. This pattern can be used to evaluate existing parks as well as a design tool to make improvements in open public green areas (

Appendix A and

Appendix B).

Selected examples of the implementation of the open urban block-Macrolot are ZAC (Zone d’Aménagement Concerté) Massena, ZAC Trapeze and ZAC Clichy-Batignolles. All of the studied neighborhoods in France were designed according to Macrolot’s idea (

Figure 1 and Figure 6) [

13,

14,

15]. The Polish examples bear some resemblance to the Macrolots (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). Thus, the interior courtyards of both selected Polish neighborhoods are connected to form open green spaces, carefully designed and decorated with modern art pieces. The viability of the Macrolot concept was confirmed. Some similarities were obvious when comparing selected examples from Poland and France. Both Riverview and Ostoja Wilanów resemble the concept of a Macrolot. Both have openings and active frontages along the streets and shared open green spaces. The Macrolot offers a compact urban form and facilitates sustainability.

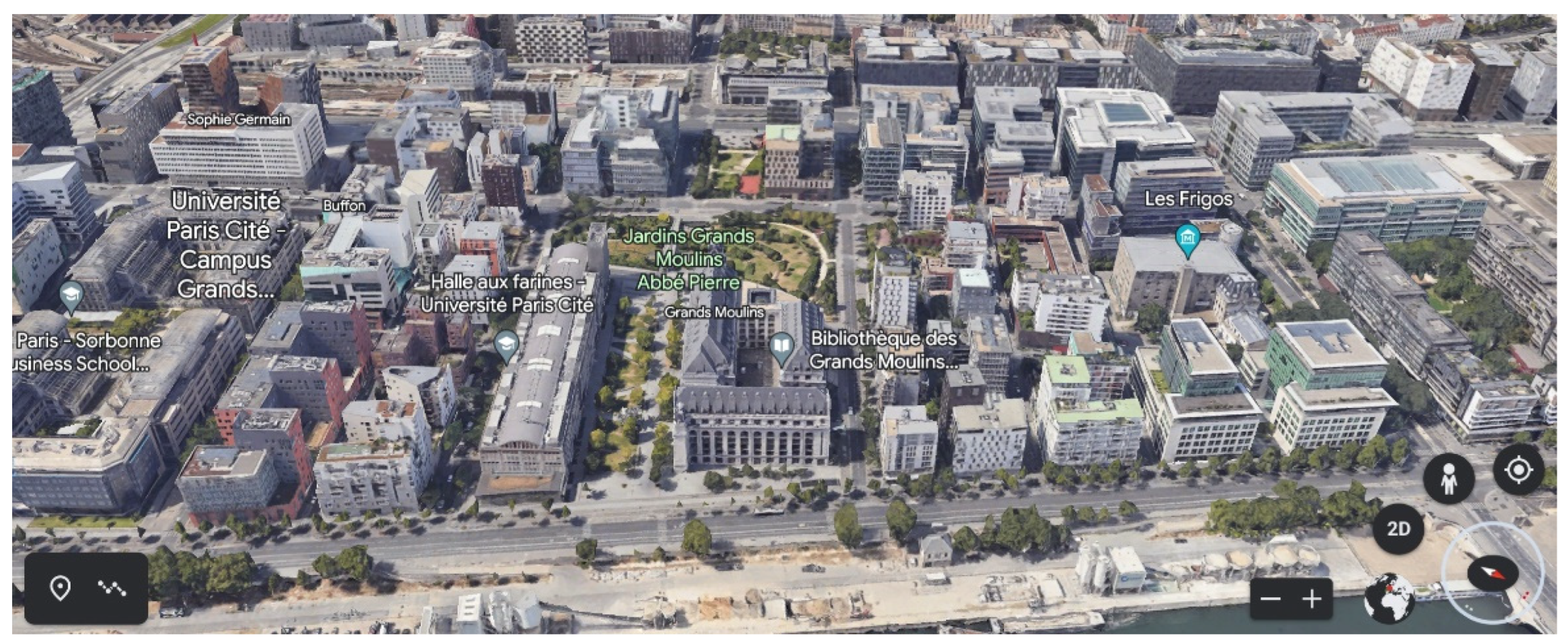

2.1. Christian de Portzamparc. ZAC (Zone D’aménagement Concerté) Rive Gauche. ZAC MASSENA, PARIS

This eco-neighborhood was designed by Christian de Portzamparc and landscape architect Thierry Huau. The project “Seine rive gauche” started in 1991, developed by SEMAPA (Société d’Economie Mixte de Paris). Christian de Portzamparc planned commercial spaces and services along the streets and residential units inside the “îlots ouverts” open islands of macrolots [

13,

14]. ZAC Paris Rive Gauche is a living example of his theory turned into practice. The site encompasses a strip of land 2,7 km long, with an area of 130 ha. Numerous revitalized ancient industrial buildings are enhancing architectural variety. The same can be said of functional and social variety. Half of the 4000 apartments are social housing [

13,

14]. The project included a comprehensive urban design with specifications of rules for urban blocks, built-up volumes, traced routes, and public gardens.

In the center of the development, there is a public park with a surface of 11,2 ha [

13,

14]. Moreover, each group of houses has access to an interior garden which can be private or form part of a public green corridor running along the district.

Figure 3.

Bird’s eye view of ZAC Massena, Rive Gauche, Paris. Eco-district was designed by Christian de Portzamparc according to Macrolot and open block principles. Source: Google Maps, retrieved 20.07.202.

Figure 3.

Bird’s eye view of ZAC Massena, Rive Gauche, Paris. Eco-district was designed by Christian de Portzamparc according to Macrolot and open block principles. Source: Google Maps, retrieved 20.07.202.

2.2. ZAC CLICHY-BATIGNOLLES, Architecte-Urbaniste François Grether, Landscape Architect Jacquelin Osty

This eco-neighborhood was planned as a showcase model of a sustainable district. The city of Paris had an ambition to organize the Olympic Games in 2008 and the ZAC Clichy- Batignolles was planned to become the Olympic Village. Eventually, the Olympic Games were organized by China, but the idea to promote the sustainability in new urban renewal project was kept. The functional and architectural diversity was promoted, and each of the open blocks was designed by a different architectural office. The project Clichy-Batignolles is divided into 3 secteurs:

ZAC Cardinet Chalabre (7,6 ha)

ZAC Clichy-Batignolles (43,2 ha)

Urban island Saussure (3 ha) which is located on the opposite side of the railroad

Only 12% of the district area is dedicated to driveways accessible to motorized vehicles [

23,

24,

25,

26]. Public transportation is given a priority. The new metro line no 14 and tramway lines were lengthened to the eco-neighborhood. The new public transport stops were constructed inside or close to the new district. To give priority to public transport the car parking areas were reduced. Therefore the basic parking indicators are:

1 parking space per 100m2 of apartment space,

0,33 of 1 parking space per 100 m² of office space,

0,28 of parking space per 100 m² of commercial space.

The eco-neighborhood was planned to accommodate 7500 new inhabitants,12 700 employees, and 5000 visitors to the new Palais of Justice, commercial, educational, and cultural centers and services located within the new district daily. Half of all the new apartments–3400 were planned to become social housing, 20%–were apartments with regulated rent and only 30% were available to potential buyers [

15,

26,

27,

28,

29].

The masterplan was designed by a team led by architecte-urbaniste François Grether, landscape architect Jacquelin Osty, and the agency responsible for sustainable solutions–OGI. The project encompasses 54 hectares at the former SNCF rail yard in the north of the Batignolles neighborhood (Paris 17th arrondissement) [

13]. It was designed according to the Macrolot concept by Christian de Portzamparc. Each Macrolot could be built with approx. 10 000–30 000 m2 SHON [

15,

26,

27,

28,

29].

This idea facilitated the creation of one of the largest public parks–Martin Luther King Park, which spans over 10 hectares in the center of the new district. The park is the heart of the new development. All of the pedestrian routes are leading to the park and are crossing the park. The design facilitates everyday contact with nature in a safe and inclusive open public green space.

Figure 4.

Bird’s eye view of ZAC Clichy-Batignolles, Paris. Eco-district was designed by François Grether according to Macrolot and open block principles. Source: Google Maps, retrieved 20.07.2023.

Figure 4.

Bird’s eye view of ZAC Clichy-Batignolles, Paris. Eco-district was designed by François Grether according to Macrolot and open block principles. Source: Google Maps, retrieved 20.07.2023.

Figure 5.

Scale model of of ZAC Clichy-Batignolles, Paris. Eco-district was designed by François Grether according to Macrolot and open block principles. Source: photo by author.

Figure 5.

Scale model of of ZAC Clichy-Batignolles, Paris. Eco-district was designed by François Grether according to Macrolot and open block principles. Source: photo by author.

2.3. Patric Chavannes. ZAC TRAPEZE, BOULOGNE-BILLANCOURT

This eco-neighborhood exemplifies the idea of macrolot. It was designed by architect-urbanist Patrick Chavannes and a team of specialists in various fields. The construction started in January 2012 and was scheduled to be finished in 2023 [

30].

The vast area of the former Renault factory is 74 ha, including ZAC Trapèze, ZAC Pont de Sèvres, l’île Seguin, and separate blocks. The Macrolots have various sizes, ranging from (200-400 long and 150-200 in depth). Each Macrolot can be developed with volumes up to 30 000 et 50 000 m² de SHON (area without net built area) and is divided into plots with multifunctional development [

30,

31,

32]. This eco-neighborhood is characterized by a social, functional, and architectural variety [

30,

31,

32].

Access to open green spaces was secured with a centrally located public park of 7 ha. The private interior gardens are located inside open blocks. There are green corridors along pedestrian paths and motor vehicle routes. The open public green spaces are open and inclusive, safe and well-maintained.

Figure 6.

Bird’s eye view of ZAC Trapeze, Boulogne-Billancourt, Paris. Eco-district was designed by Patrick Chavannes according to Macrolot and open block principles. Source: Google Maps, retrieved 20.07.2023.

Figure 6.

Bird’s eye view of ZAC Trapeze, Boulogne-Billancourt, Paris. Eco-district was designed by Patrick Chavannes according to Macrolot and open block principles. Source: Google Maps, retrieved 20.07.2023.

The examples from Poland are also interesting. Both of the selected developments are located in Gdańsk. Both received many awards and can be treated as examples of good and innovative practices. Riverview is the first residential development in Poland that received LEED Gold certification.

2.4. APA Wojciechowski Architekci, RIVERVIEW, GDAŃSK

The Riverview complex of seven buildings located next to the Granary Island in Gdańsk was completed in 2020. This location offers easy access to the city center. The development encompasses an area of 3,8 hectares [

33,

34]. It was designed to seamlessly fit into the neighborhood and the city skyline. The character of the project alludes to surrounding historical buildings and Hanseatic architecture. However, the aim was to create a modern and timeless development. The complex has many openings facing the river and a compact frontage from the street. The urban design facilitates access to safe, open, and inclusive public green spaces.

The complex includes space for offices, retail units, and open green spaces. Riverview’s shared space was created in collaboration with the students of the Academy of Fine Arts in Gdańsk, who designed and produced the elements of street furniture. The architects and designers took a modern approach by using minimalistic details and ensuring high-quality workmanship. The complex was developed by Vastint.

2.5. Kuryłowicz and Associates, Ostoja Wilanów, Warsaw

This large neighborhood–17,4 ha, 33 buildings, was developed in phases from 2005 to 2017. Ostoja Wilanów is a development located on the outskirts of the new neighborhood–Wilanów. 45% of the land is developed as green areas [36]. Inside the development a 2 hectares of green corridor–a linear park was developed around a retention pond with a stream, bridges, benches, and pedestrian paths. A gated private forest park form also part of the investment. There are a few playgrounds. Public space and public plazas in front of the local church were designed with care for details. There are numerous local services and a kindergarten located inside the neighborhood. The Ostoja Wilanów was awarded a prize for being sound with principles of sustainable development. This development offers safe and inclusive open public green space on top of private gardens and parks for the inhabitants.

3. Results

This research demonstrates how operationalization of SDGs–11. Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable in urban planning & design is present in eco-neighborhood development. Chrisitan de Portzamparc created the concept of Macrolot based on la ville de l’Age III, which unites the qualities of traditional urban blocks with modernist suggestions for a healthy city that could facilitate that implementation. It could be used for eco-neighborhood design not only in France but also in other countries. The concept of Macrolot proved to be useful in securing space for local urban parks in densely inhabited urban neighborhoods (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Urban morphology of selected neighbourhoods, Source (a-c) Geoportail.gouv.fr, accessed on 27.12.2023, (d-e) Geoportal.pl, accessed on 27.12.2023.

Figure 7.

Urban morphology of selected neighbourhoods, Source (a-c) Geoportail.gouv.fr, accessed on 27.12.2023, (d-e) Geoportal.pl, accessed on 27.12.2023.

3.1. Health-Promoting Urban Places–Public Parks and Gardens

This study included an assessment of the health-promoting qualities of public parks in selected neighborhoods. The author’s original method–the universal pattern of design for health-promoting places (Table 3,

Appendix A) was used to assess the qualities of open public green spaces in selected neighborhoods. In this study, a simplified rough assessment method was used to compare the overall health-promoting qualities of open public green areas in selected neighborhoods: ZAC Massena, ZAC Trapeze, ZAC Clichy Batignolles in France, and Riverview and Ostoja Wilanowska in Poland (

Appendix B). The binary assessment method was used for the evaluation of comparable attributes: 0 -not present, 1-present. The results of this study are presented in Table 4,

Appendix B.

This study demonstrated some divergences and discrepancies, as well as fields for possible improvement. The largest Parc Martin Luther King received the highest score, followed by Jardins Abbee Pierre and Parc de Billancourt.

However, the order of scores did not match the order of sizes of the parks. It is easier to provide all sorts of park interiors, infrastructure, and equipment in larger parks, over 10 ha. What was surprising was the small park Jardins Abbe Pierre [

13,

14,36] and interior gardens in Riverview [

33,

34] received a relatively large number of points. It proves that even pocket parks can promote the health and well-being of local inhabitants, even though they could neither compete nor replace larger parks.

Table 2.

Comparison of open green areas within selected neighborhoods.

Table 2.

Comparison of open green areas within selected neighborhoods.

| |

Total area |

PUBLIC PARK |

Public park/ total area ratio |

Open green public courtyards |

Private park / garden |

| ZAC Massena [13,14,36] |

130 ha |

Jardins Abbee Pierre–

1,2 ha |

0,01 |

|

Some individual lots are fenced |

ZAC Clichy Batignolles [15,26,27,28,29]

|

54 ha |

Parc Martin Luther King–10 ha |

0,19 |

|

Some individual lots are fenced |

| ZAC Trapeze [30,31,32] |

74 ha |

Parc de Billancourt–

7 ha |

0,09 |

|

Some individual lots are fenced |

| Riverview [33,34] |

3,8 ha |

Public riverfront of Motława, pedestrian path along the banks |

Access to green and blue city infrastructure |

Open interior gardens |

|

| Ostoja Wilanów [35] |

17,4 ha |

Linear Park

-2h |

0,11 |

Open interior gardens |

Private, fenced park accessible to inhabitants only |

Figure 8.

Public parks and gardens in selected neighborhoods were created as a result of implementation of open urban blocks, source: Author.

Figure 8.

Public parks and gardens in selected neighborhoods were created as a result of implementation of open urban blocks, source: Author.

3.2. Placemaking

According to Project for Public Spaces [

36] Placemaking inspires people to collectively reimagine and reinvent public spaces as the heart of every community (…) and it results in the creation of quality public spaces that contribute to people’s health, happiness, and wellbeing. The studied neighborhoods offered quality public spaces. How was it achieved?

The process of neighborhood development was different in France and Poland. The French ÉcoQuartiers were constructed by the local government which engaged private stakeholders and developers. In Poland, the neighborhoods were developed by private companies. In France, the grassroots level of the user is taken into consideration early in the design process and down-up management and public participation in decision making is encouraged. In Poland, this process of public participation is still under development.

However, the public spaces of all selected neighborhoods have similar aesthetic qualities. There is a close relationship between the quality and accessibility of public spaces and urban forms of open blocks. The selected neighborhoods offer attractive public spaces which can be called third [

37] and fourth places [

38]. Moreover, there are also numerous locations within accessible walking distance to places that can fulfill the role of third places in all studied cases [

36,

37,

38].

Modern research confirms the human need for a stimulating environment, full of engaging details [

4,

5]. However, it is difficult to design architectural variety without falling into the trap of overstimulating cacophony. Architectural variety requires not only multiple architectural practices, but also a leading Architect, or a supervising board who coordinates design, materials, and color schemes.

The architectural variety is much more pronounced in France than it is in Poland. Each of the blocks or even individual buildings is designed by a different architectural practice. The majority of work is commissioned only to the winners of architectural compositions. It seems that the public demand for architectural variety is much more articulated in France. To avoid cacophony the Ecoquartiér are designed according to masterplans which come with precise color and material schemes. Their execution is coordinated by leading architects and urbanists, usually the author of the masterplan. Large-scale developments are controlled by a board of supervising specialists.

The examples from Poland also demonstrate some architectural variety. The Riverview complex has diversified street frontage and the Ostoja Wilanów was designed in various phases.

The functional variety was present in all selected developments. Functional variety and walkability promote active living and physical activity. The examples from France demonstrate a higher percentage of mixed-use urban tissue than those from Poland. That might be a result of location. ZAC Massena and ZAC Clichy-Batignolles are located in Paris and ZAC Trapeze forms a central part of the new large district. The Riverview and Ostoja Wilanów in Poland rely on the functional variety of their surroundings and function as residential neighborhoods with only the most basic services (Figure 4).

It is worth noting that the criteria for safety assessment are prone to be subjective. Many cases exist where areas with good accessibility and close proximity deteriorate into high-crime zones due to neglect or lack of management. Placemaking motivates place attachment and inspires people to look after open public green spaces.

4. Conclusions

The application of the Macrolot concept to urban planning and design offers possibilities to implement the SDGs: 11. Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable are discussed. The concept of Macrolot proved to be useful in securing space for inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable local urban parks in densely inhabited urban neighborhoods. The public parks created within five neighborhoods observed in this study were assessed as health-promoting everyday spaces with the Author’s assessment tool–Universal Standard for Health-promoting Urban Places. Moreover, this study demonstrated that even pocket parks can promote health and well-being of local inhabitants, even though they could neither compete nor replace larger parks. Their assessment with The Universal Standard for health promoting places demonstrated satisfactory results. The concept of the Macrolot coined by Christian de Portzamparc can be recommended for urban planning and design.

The results may serve as a ground for further discussion about the future of health-promoting urban design in Poland, but also due to the geographical and cultural similarities of other countries in Central and Eastern Europe. The limitations of this study to this geographic area may provoke possible development of this research. Similar studies may be implemented in other parts of the world to verify the health-promoting potential of urban design of eco-neighborhoods based on Macrolot morphology in other climate zones.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table 1.

Universal standard for health promoting places. Source [

20].

Table 1.

Universal standard for health promoting places. Source [

20].

| Universal Standard for Health Promoting Places |

|---|

| Universal Standard for Therapeutic Parks |

|---|

| 1. Universal design |

2. Park’s functional program |

3. Organization of space and functions |

4. Placemaking |

5. Sustainability |

6. Access to park |

1.1 Place

Area

Location

Surrounding urban pattern

1.2 Environmental characteristics

Soil quality

Water quality

Air quality

Noise level

Biodiversity

Forms of nature protection

1.3 Universal accessibility (addressing need of people with disabilities)

1.4 Access to park

Distance to potential users

Public transport stops

Walkways to park |

2.1. Psychological and physical regeneration

Natural Landscapes

Green open space

Place to rest in the sun and in the shade

Place to rest in silence and solitude

Possibility to observe other people

Possibility to observe animals

2.2. Social Contacts Enhancement

Organization of events inside the park

Gathering place for groups

2.3. Physical Activity Promotion

Sports infrastructure

Recreational infrastructure

Community gardens

2.4. Catering for basic needs

Safety and security (presence of guards, cleanness, maintenance, etc.)

Places to sit and rest

Shelter

Restrooms

Drinking water

Food (possibility to buy food in the park or close vicinities) |

3.1. The park spatial composition follows the surrounding urban pattern

3.2. Architectural variety of urban environment

Focal points and landmarks

Structure of interiors and connections

Long vistas (Extent)

Pathways with views

Invisible fragments of the scene (Vista engaging the imagination)

Mystery, Fascination

Framed views

Human scale

3.3. Optimal level of complexity

3.4. Natural surfaces

3.5. Engaging features

Risk/Peril

Movement

3.6. Presence of Water

3.7. Sensory stimuli design

Sensory stimuli: Sight

Sensory stimuli: Hearing

Sensory stimuli: Smell

Sensory stimuli: Touch

Sensory stimuli: Taste

Sensory path |

4.1. Works of Art

4.2. Monuments in the park

4.3. Historic places

Culture and connection

to the past

4.4. Thematic gardens

4.5. Personalization

4.6. Animation of place

4.7. Community Engagement

Personalising the architectural process

Participation of all stakeholders, including inhabitants and users

Determining the rules of conduct and self-management

Space for social contact

- third places

- fourth places |

5.1. Green Infrastructure

5.2. Parks of Second (New) Generation

5.3. Biodiversity protection

Part of park not-available to visitors

Native plants

Native animals

Natural maintenance methods

5.4. Sustainable water management

Rainwater infiltration

Irrigation with non-potable water

5.5. Urban metabolism

5.6. Ecological energy sources

|

6.1 Sidewalk Infrastructure-

Width of sidewalk Evenness of surface

Lack of obstructions Slope

Sufficient drainage

6.2 General conditions: Maintenance

Overall aesthetics

Street art

Sufficient seating

Perceived safety

Buffering from traffic

Street activities

Vacant lots

6.3 Traffic

Speed

Volume

Number and safety of crossings

On-street parking

6.4 User Experience

Air quality

Noise level

Sufficient lighting

Sunshine and shade

Transparency of ground floors of building |

Appendix B

In this study a simplified rough assessment method was used to compare the overall health-promoting qualities of open public green areas in selected neighborhoods: ZAC Massena, ZAC Trapeze, ZAC Clichy Batignolles in France, and Riverview and Ostoja Wilanowska in Poland.

The binary assessment method was used for evaluation of comparable attributes:

0-not present

1-present

Table 3.

The rough assessment of open green public spaces in selected neighborhoods.

Table 3.

The rough assessment of open green public spaces in selected neighborhoods.

| The Universal standard for health-promoting places |

Selected neighbourhoods |

| |

1. ZAC MASSENA |

2. ZAC TRAPEZE

|

3. ZAC CLICHY BATIGNOLLES |

4. RIVERVIEW |

5. OSTOJA WILANOWSKA |

| 1. UNIVERSAL DESIGN |

|

|

|

|

|

| 1.1 Place |

|

|

|

|

|

| Area, approximately |

130 ha /

Jardin Grands Moulins Abbé Pierre

1,2 ha |

74 ha /

Parc de Billancourt–7ha |

54 ha /

Parc Martin Luther King–10ha |

3,8 ha /

Interior gardens |

17,4 ha /

Linear Park–2ha |

| Location |

Paris |

Paris |

Paris |

Gdańsk |

Warsaw |

| Surrounding urban pattern |

dense urban tissue |

dense urban tissue |

dense urban tissue, |

dense urban tissue |

loose urban tissue, forest |

| 1.2Environmental characteristics |

|

|

|

|

|

| Soil quality |

brownfield |

brownfield |

brownfield |

brownfield |

Unbuilt green periurban space |

| Water quality |

|

good |

good |

good |

good |

| Air quality |

good [39] |

good [39] |

good [39] |

good [40] |

good [41] |

| Biodiversity |

Local species vere observed |

Local species vere observed |

Local species vere observed |

Local species vere observed |

Local species vere observed |

| Forms of nature protection |

Yes–fragment of park is closed to visitors |

Yes–fragment of park is closed to visitors |

Yes–fragment of park is closed to visitors |

No |

No |

| 1.3 Universal accessibility |

accessible |

accessible |

accessible |

partially accessible, steep slope |

accessible |

|

1.4 Access to park

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Distance to potential users |

less than 500m |

less than 500m |

less than 500m |

less than 500m |

less than 500m |

| Public transport stops |

less than 500m |

less than 500m |

less than 500m |

less than 500m |

less than 500m |

| Walkways to park |

multiples |

multiples |

multiples |

multiples |

multiples |

| 2. PARK’S FUNCTIONAL PROGRAM |

|

|

|

|

|

| 2.1. Psychological and physical regeneration |

|

|

|

|

|

| Natural Landscapes |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

| Green open space |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| Place to rest in the sun and in the shade |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| Place to rest in silence and solitude |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| Possibility to observe other people |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| Possibility to observe animals |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| 2.2. Social Contacts Enhancement |

|

|

|

|

|

| Organization of events inside the park |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| Gathering place for groups |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| 2.3. Physical Activity Promotion |

|

|

|

|

|

| Sports and recreational infrastructure |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| Community gardens |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

| 2.4. Catering for basic needs |

|

|

|

|

|

| Safety and security |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| Places to sit and rest |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| Shelter |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

| Restrooms |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

| Drinking water |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

| Food |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

| 3. ORGANISATION OF SPACE AND FUNCTIONS |

|

|

|

|

|

| 3.1. The park spatial composition follows the surrounding urban pattern |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| 3.2. Architectural variety of urban environment |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| Focal points and landmarks |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| Structure of interiors and connections |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| Long vistas (Extent) |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| Pathways with views |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| Invisible fragments of the scene (Vista engaging the imagination) |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| Mystery, Fascination |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| Framed views |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| Human scale |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| 3.3. Optimal level of complexity |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| 3.4. Natural surfaces |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| 3.5. Engaging features |

|

|

|

|

|

| Risk/Peril |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| Movement |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| 3.6. Presence of Water |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

| 3.7. Sensory stimuli design |

|

|

|

|

|

| Sensory stimuli: Sight |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| Sensory stimuli: Hearing |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| Sensory stimuli: Smell |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| Sensory stimuli: Touch |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| Sensory stimuli: Taste |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

| Sensory path |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 4. PLACEMAKING |

|

|

|

|

|

| 4.1. Works of Art |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| 4.2. Monuments in the park |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| 4.3. Historic places |

|

|

|

|

|

| Culture and connection to the past |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| 4.4. Thematic gardens |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| 4.5. Personalization |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

| 4.6. Animation of place |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| 4.7. Community Engagement |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| Personalising the architectural process |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| Participation of all stakeholders, including inhabitants and users |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

| Determining the rules of conduct and self-management |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| Space for social contact |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| - third places |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| - fourth places |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| 5. PURSUIT OF -SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT |

|

|

|

|

|

| 5.1. Green Infrastructure |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| 5.2. Parks of Second (New) Generation |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| 5.3. Biodiversity protection |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| Part of park not-available to visitors |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

| Native plants |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| Native animals |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| Natural maintenance methods |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| 5.4. Sustainable water management |

|

|

|

|

|

| Rainwater infiltration |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| Irrigation with non-potable water |

Data n/a |

Data n/a |

Data n/a |

Data n/a |

Data n/a |

| Park in a flood risk zone |

no |

yes |

no |

no |

no |

| 5.5. Urban metabolism |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| 5.6.Ecological energy sources |

Data n/a |

Data n/a |

Data n/a |

Data n/a |

Data n/a |

| TOTAL |

57 |

56 |

58 |

47 |

50 |

References

- United Nations. (2015), General Assembly Resolution A/RES/70/1. Transforming Our World, the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. [cited 2016 Feb 10]. Available online: http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/70/1&Lang=E (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Trojanowska, M., Sas-Bojarska A. Health-affirming everyday landscapes in sustainable city. Theories and tools. Architecture, Civil and Environmental Engineering, No 3/2018. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Inclusive Public Space project, University of LEEDS. Available online: https://inclusivepublicspace.leeds.ac.uk/ (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Universal Design Principles. University at Buffalo (UB) University of Buffalo. Accessibility at UB. Available online: https://www.buffalo.edu/access/help-and-support/topic3/universaldesignprinciples.html (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Trojanowska, M. Urban design and therapeutic landscapes. Evolving theme. Budownictwo i Architektura, 2021, vol. 20, nr 1, s.117-140. [CrossRef]

- Trojanowska, M. Health-Promoting Places: Architectural Variety. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering. 2020, 960. 022024. 10.1088/1757-899X/960/2/022024.

- Trojanowska, M. Parki i ogrody terapeutyczne Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN, Warszawa, 2017.

- Trojanowska, M. Trojanowska M. Architectural Strategies that promote creation of social bonds within eco-neighbourhoods, Space & FORM, 2021, 46, 195-210. Available online: http://www.pif.zut.edu.pl/pl/pif46-2021/.

- Guislain, M. Le macrolot, paysage urbain du XXI siécle? AMC Le Moniteur architecture. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Guislain, M. Christian de Portzamparc, en noir & blanc et en lumière. Le Moniteur, 30 decembre 2019. Available online: https://www.lemoniteur.fr/article/christian-de-portzamparc-en-noir-blanc-et-en-lumiere.2069424 (accessed on 15 September 2023).

- Masbuongi, A. Grand Prix de l’urbanisme 2004: Christian de Portzamparc, Collection: Projet urbain, Parenthèses Editions, Paris, 2006.

- Kantarek, A. O orientacji w przestrzeni miasta. Politechnika Krakowska, Kraków, 2013.

- PARIS–Quartier Massena. Available online: https://www.christiandeportzamparc.com/en/projects/quartier-massena/ (accessed on 15 September 2023).

- Petite histoire du quartier ZAC Masséna. Available online: http://blog.ac-versailles.fr/hdamaupassant3eme/public/ZAC_Massena.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2023).

- Le projet ZAC Clichy-Batignolles. Available online: http://didierfavre.com/Historique-Batignolles.php?SmartphoneWidth=3 (accessed on 15 September 2023).

- Le Corbusier. La Charte d’Athènes. Paris: La Librairie Plon, Paris, 1943.

- Sert, J.L. Can Our Cities Survive? Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 1942.

- Frampton, K. Modern Architecture. Thames and Hudson, London, 1992.

- Available online: https://www.christiandeportzamparc.com/en/projects/les-hautes-formes/ (accessed on 15 September 2023).

- Cassaro P.F., Magliacani F. The European block as a renewed spatial entity among collective living, functional autonomy and sustainability, FAMagazine, 2020. Available online: https://www.famagazine.it/index.php/famagazine/article/view/522/1485.

- Burgess R., Jencks M. Compact Cities: Sustainable Urban Forms for Developing Countries, Routledge, 2003.

- Mobaraki, A.; Oktay Vehbi, B. A Conceptual Model for Assessing the Relationship between Urban Morphology and Sustainable Urban Form. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codispoti, O. Sustainable urban forms: eco-neighbourhoods in Europe, Journal of Urbanism: International Research on Placemaking and Urban Sustainability, 2022, 15:4, 395-420. [CrossRef]

- Bednarowska Z, (2015), Desk research–wykorzystanie potencjału danych zastanych w prowadzeniu badań marketingowych i społecznych, „Marketing i Rynek”, 2015, 7, 18–26.

- Trojanowska, M. A universal standard for health-promoting places. Example of assessment–on the basis of a case study of Rahway River Park, Budownictwo i Architektura, 2021, Vol 20, 3, s. 57-84.

- Available online: https://www.batiactu.com/edito/zac-clichy-batignolles---le-projet-devoile-aux-riv-33174.php (accessed on 15 September 2023).

- Available online: https://www.parisetmetropole-amenagement.fr/sites/default/files/2020-02/BAT-NUM_CB_DP_OCT2019_20191202_WEB.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2023).

- Available online: https://www.parisetmetropole-amenagement.fr/sites/default/files/2018-11/BD_CB_DossierPress_En_060317.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2023).

- Available online: https://www.parisetmetropole-amenagement.fr/en/clichy-batignolles-paris-17th#scrollNav-5 (accessed on 15 September 2023).

- Available online: https://www.ileseguin-rivesdeseine.fr/fr/le-quartier-du-trapeze (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Available online: https://www.boulognebillancourt.com/fileadmin/medias/ARBORESCENCE/Ma_Ville/Urbanisme_et_grands_projets/Ile_Seguin_Rives_de_Seine/1_RAPPORT_D_ENQUETE_BOULOGNE_D5.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2023).

- Rapport d’enquête publique Numéro E20 000019/92, 23 septembre 2020.

- Available online: https://www.archdaily.com/973475/riverview-complex-apa-wojciechowski-architects (accessed on 15 September 2023).

- Available online: https://vastint.eu/pl/pl/projects/riverview-2/?lang=pl (accessed on 15 September 2023).

- Available online: https://www.ostoja-wilanow.com/pl_ostoja-wilanow.html (accessed on 15 September 2023).

- Available online: https://www.in-foliopaysagistes.fr/%C3%A9tudes-et-r%C3%A9alisations/parcs-et-jardins/paris-grands-moulins/ (accessed on 27 December 2023).

- Project for Public Spaces, What is Placemaking? Available online: https://www.pps.org/article/what-is-placemaking (accessed on 27 December 2023).

- Oldenburg, R. The Great Good Place: Cafes, Coffee Shops, Community Centers, Beauty Parlors, General Stores, Bars, Hangouts, and How They Get You Through the Day. Paragon House, New York, 1989.

- Simões Aelbrecht P. 2016. ‘Fourth places’: the contemporary public settings for informal social interaction among strangers, Journal of Urban Design, 2016, 21:1, 124-152. [CrossRef]

- Paris Air Pollution: Real-time Air Quality Index (AQI), Air Pollution in the World Real-time Air Quality Index (AQI). Available online: https://aqicn.org/city/paris/ (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Warsaw Zanieczyszczenie powietrza. wskaźnik jakości powietrza (AQI) w czasie rzeczywistym., Air Pollution in the World Real-time Air Quality Index (AQI). Available online: https://aqicn.org/city/warsaw/pl/ (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Gdansk Srodmiescie, Gdansk Air Pollution: Real-time Air Quality Index (AQI), Air Pollution in the World Real-time Air Quality Index (AQI). Available online: https://aqicn.org/search/#q=Gda%C5%84sk (accessed on 15 April 2024).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).