Submitted:

25 June 2024

Posted:

25 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

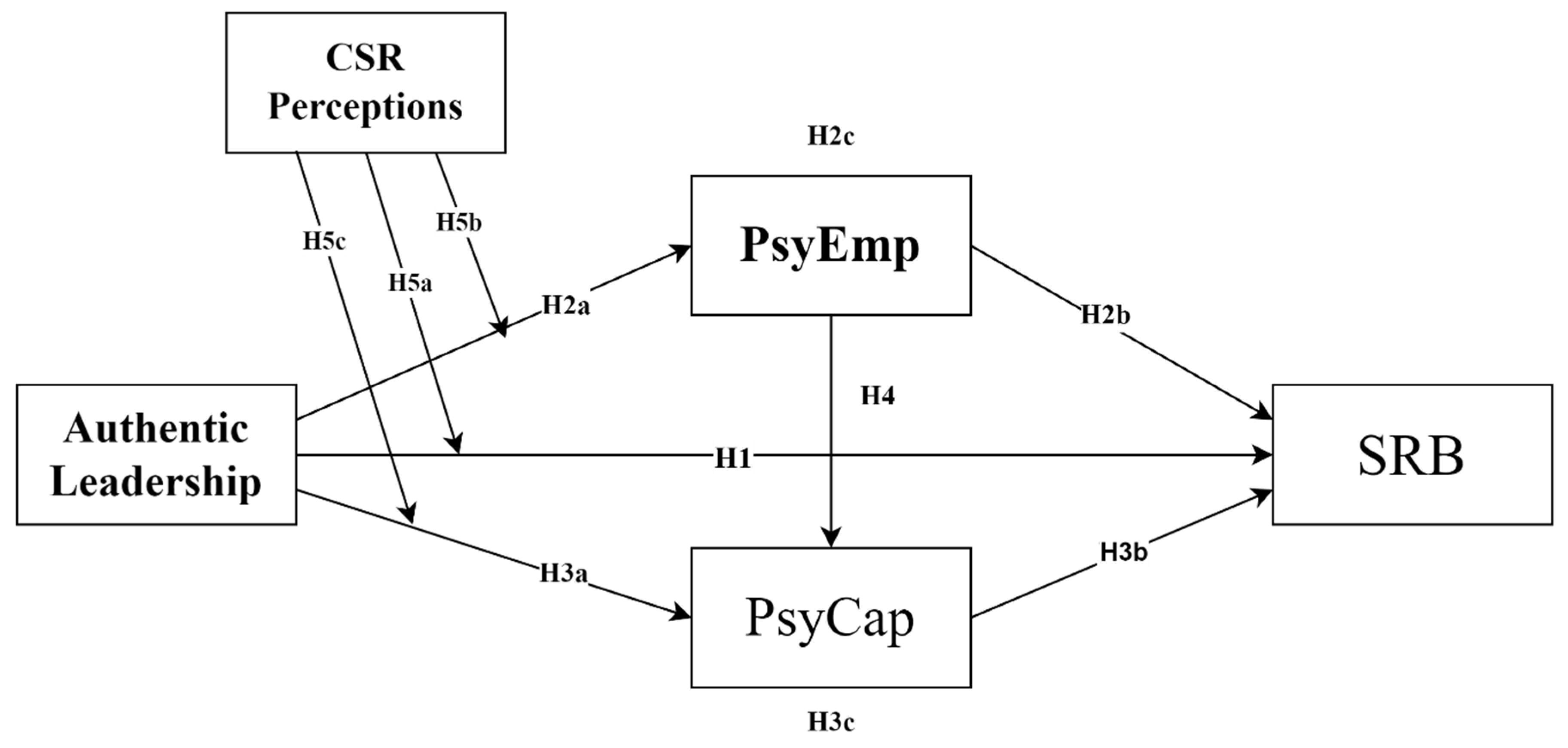

2. Literature and Hypothesis

2.1. Socially Responsible Behavior

2.2. Authentic Leadership and Socially Responsible Behavior

2.3. Psychological Empowerment as a Mediator

2.4. Psychological Capital as a Mediator

2.5. Serial Mediation

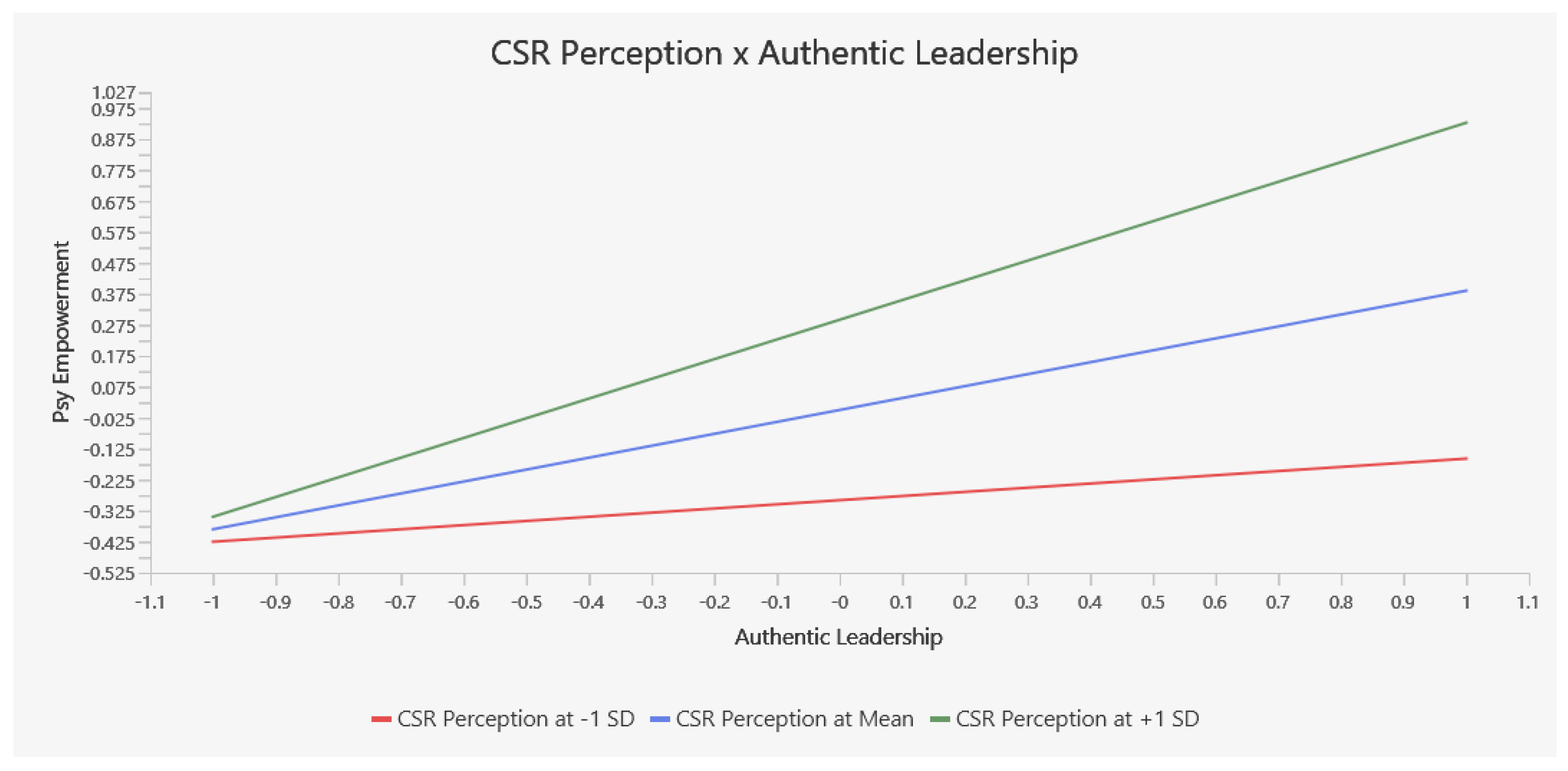

2.6. CSR Perception as a Moderator

3. Measures

Analysis Strategy

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitation and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bocean, C.G.; Nicolescu, M.M.; Cazacu, M.; Dumitriu, S. The Role of Social Responsibility and Ethics in Employees’ Wellbeing. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19, 8838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Dick, R.; Crawshaw, J.R.; Karpf, S.; Schuh, S.C.; Zhang, X.-a. Identity, importance, and their roles in how corporate social responsibility affects workplace attitudes and behavior. Journal of Business and Psychology 2020, 35, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crilly, D.; Schneider, S.C.; Zollo, M. Psychological antecedents to socially responsible behavior. European Management Review 2008, 5, 175–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veetikazhi, R. Socially responsible behaviour at work: the impact of goal directed action and leadership. Dissertation, Duisburg, Essen, Universität Duisburg-Essen, 2021, 2021.

- Carroll, A.B.; Shabana, K.M. The business case for corporate social responsibility: A review of concepts, research and practice. International journal of management reviews 2010, 12, 85–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, J.; Schrader, J. Corporate social responsibility: A microeconomic review of the literature. Journal of Economic Surveys 2015, 29, 27–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavas, A.; Kelley, K. The effects of perceived corporate social responsibility on employee attitudes. Business ethics quarterly 2014, 24, 165–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, M.; Xu, S.; Liu, X.; Newman, A. Antecedents and outcomes of authentic leadership across culture: A meta-analytic review. Asia Pacific Journal of Management 2022, 39, 1399–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caza, A.; Jackson, B. Authentic leadership. The SAGE handbook of leadership 2011, 352–364. [Google Scholar]

- Avolio, B.J.; Gardner, W.L. Authentic leadership development: Getting to the root of positive forms of leadership. The leadership quarterly 2005, 16, 315–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, W.L.; Avolio, B.J.; Luthans, F.; May, D.R.; Walumbwa, F. “Can you see the real me?” A self-based model of authentic leader and follower development. The leadership quarterly 2005, 16, 343–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroy, H.; Anseel, F.; Gardner, W.L.; Sels, L. Authentic leadership, authentic followership, basic need satisfaction, and work role performance: A cross-level study. Journal of management 2015, 41, 1677–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, F.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, S. The interactive effect of authentic leadership and leader competency on followers’ job performance: The mediating role of work engagement. Journal of Business Ethics 2018, 153, 763–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimnia, F.; Sharifirad, M.S. Authentic leadership and employee well-being: The mediating role of attachment insecurity. Journal of Business Ethics 2015, 132, 363–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, N.; Duarte, A.P.; Filipe, R.; David, R. Does authentic leadership stimulate organizational citizenship behaviors? The importance of affective commitment as a mediator. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal 2022, 13, 320–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mubarak, F.; Noor, A. Effect of authentic leadership on employee creativity in project-based organizations with the mediating roles of work engagement and psychological empowerment. Cogent Business & Management 2018, 5, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, E. Authentic leadership and task performance via psychological capital: the moderated mediation role of performance pressure. Frontiers in Psychology 2022, 13, 722214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Song, L.J.; Wang, Y.; Liu, G. How authentic leadership influences employee proactivity: the sequential mediating effects of psychological empowerment and core self-evaluations and the moderating role of employee political skill. Frontiers of business research in China 2018, 12, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rego, A.; Sousa, F.; Marques, C.; e Cunha, M.P. Authentic leadership promoting employees’ psychological capital and creativity. Journal of business research 2012, 65, 429–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muduli, A.; Pandya, G. Psychological empowerment and workforce agility. Psychological Studies 2018, 63, 276–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F.; Youssef, C.M. Human, Social, and Now Positive Psychological Capital Management:: Investing in People for Competitive Advantage. Organizational Dynamics 2004, 33, 143–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E.; Halbesleben, J.; Neveu, J.-P.; Westman, M. Conservation of resources in the organizational context: The reality of resources and their consequences. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior 2018, 5, 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Asian journal of social psychology 1999, 2, 21–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, G.K.; Sully de Luque, M. Antecedents of responsible leader behavior: A research synthesis, conceptual framework, and agenda for future research. Academy of Management Perspectives 2014, 28, 235–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kish-Gephart, J.J.; Harrison, D.A.; Treviño, L.K. Bad apples, bad cases, and bad barrels: meta-analytic evidence about sources of unethical decisions at work. Journal of applied psychology 2010, 95, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H.; Mavondo, F.; Sowamber, V. Corporate social responsibility at LUX* resorts and hotels: Satisfaction and loyalty implications for employee and customer social responsibility. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Morrison, A.M.; Zhang, H. Being sustainable: The three-way interactive effects of CSR, green human resource management, and responsible leadership on employee green behavior and task performance. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 2021, 28, 1043–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemphill, T.A.; Laurence, G.A. Employee social responsibility: A missing component in the ISI 26000 social responsibility standard. Business and Society Review 2018, 123, 59–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: Toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders. Business horizons 1991, 34, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Roeck, K.; Farooq, O. Corporate social responsibility and ethical leadership: Investigating their interactive effect on employees’ socially responsible behaviors. Journal of Business Ethics 2018, 151, 923–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F.; Avolio, B.J. Authentic leadership development. Positive organizational scholarship 2003, 241, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Walumbwa, F.O.; Avolio, B.J.; Gardner, W.L.; Wernsing, T.S.; Peterson, S.J. Authentic leadership: Development and validation of a theory-based measure. Journal of management 2008, 34, 89–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Tian, W.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhang, X.; Lin, W.; Li, H.; Sun, L.; Cheng, B.; Ding, H. The mediating role of psychological capital on the relationship between authentic leadership and nurses’ caring behavior: a cross-sectional study. BMC nursing 2023, 22, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hannah, S.T.; Avolio, B.J.; Walumbwa, F.O. Relationships between authentic leadership, moral courage, and ethical and pro-social behaviors. Business Ethics Quarterly 2011, 21, 555–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, H.-Y.; O-Yang, Y. How and when authentic leadership promotes prosocial service behaviors: A moderated mediation model. International Journal of Hospitality Management 2022, 104, 103227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekleab, A.G.; Reagan, P.M.; Do, B.; Levi, A.; Lichtman, C. Translating corporate social responsibility into action: a social learning perspective. Journal of Business Ethics 2021, 171, 741–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreitzer, G.M. Psychological empowerment in the workplace: Dimensions, measurement, and validation. Academy of management Journal 1995, 38, 1442–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walumbwa, F.O.; Wang, P.; Wang, H.; Schaubroeck, J.; Avolio, B.J. Retracted: Psychological processes linking authentic leadership to follower behaviors. 2010.

- Wang, H.; Sui, Y.; Luthans, F.; Wang, D.; Wu, Y. Impact of authentic leadership on performance: Role of followers’ positive psychological capital and relational processes. Journal of Organizational Behavior 2014, 35, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Kan, W.; Qin, S.; Zhao, C.; Sun, Y.; Mao, W.; Bian, X.; Ou, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Hu, Y. How authentic leadership impacts on job insecurity: The multiple mediating role of psychological empowerment and psychological capital. Stress and Health 2021, 37, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E.; Johnson, R.J.; Ennis, N.; Jackson, A.P. Resource loss, resource gain, and emotional outcomes among inner city women. Journal of personality and social psychology 2003, 84, 632–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.J.A.; Kim, W.G.; Choi, H.-M.; Li, Y. How to fuel employees’ prosocial behavior in the hotel service encounter. International Journal of Hospitality Management 2020, 84, 102333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, N.; Ryan, R.M. When helping helps: autonomous motivation for prosocial behavior and its influence on well-being for the helper and recipient. Journal of personality and social psychology 2010, 98, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, W.; Song, B.; Ferguson, M.A.; Kochhar, S. Employees’ prosocial behavioral intentions through empowerment in CSR decision-making. Public Relations Review 2018, 44, 667–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F.; Youssef, C.M.; Avolio, B.J. Psychological capital: Investing and developing positive organizational behavior. In Positive organizational behavior, Nelson, D.L., Cooper, C.L., Eds.; 2007; pp. 9–24.

- Walumbwa, F.O.; Peterson, S.J.; Avolio, B.J.; Hartnell, C.A. An investigation of the relationships among leader and follower psychological capital, service climate, and job performance. Personnel Psychology 2010, 63, 937–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, B.-K.; Lim, D.H.; Kim, S. Enhancing work engagement: The roles of psychological capital, authentic leadership, and work empowerment. Leadership & Organization Development Journal 2016, 37, 1117–1134. [Google Scholar]

- Aydin Sünbül, Z.; Aslan Gördesli, M. Psychological capital and job satisfaction in public-school teachers: the mediating role of prosocial behaviours. Journal of Education for Teaching 2021, 47, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, W.; Hahn, J. Psychological Capital and Organizational Citizenship Behaviors of Construction Workers: The Mediating Effect of Prosocial Motivation and the Moderating Effect of Corporate Social Responsibility. Behavioral Sciences 2023, 13, 981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Fu, Y.-N.; Liu, Q.; Turel, O.; He, Q. Psychological capital mediates the influence of meaning in life on prosocial behavior of university students: A longitudinal study. Children and Youth Services Review 2022, 140, 106600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumsteiger, R. Looking forward to helping: The effects of prospection on prosocial intentions and behavior. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 2017, 47, 505–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schornick, Z.; Ellis, N.; Ray, E.; Snyder, B.-J.; Thomas, K. Hope that Benefits Others: A systematic literature review of Hope Theory and prosocial outcomes. International Journal of Applied Positive Psychology 2023, 8, 37–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sri Ramalu, S.; Janadari, N. Authentic leadership and organizational citizenship behaviour: the role of psychological capital. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management 2022, 71, 365–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, T.A.; Khattak, M.N.; Zolin, R.; Shah, S.Z.A. Psychological empowerment and employee attitudinal outcomes: The pivotal role of psychological capital. Management Research Review 2019, 42, 797–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.M.; Park, S.-Y.; Lee, H.J. Employee perception of CSR activities: Its antecedents and consequences. Journal of business research 2013, 66, 1716–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, S.; Wang, Y. The consequences of employees’ perceived corporate social responsibility: A meta-analysis. Business Ethics: A European Review 2020, 29, 471–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupp, D.E. An employee-centered model of organizational justice and social responsibility. Organizational Psychology Review 2011, 1, 72–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haski-Leventhal, D.; Roza, L.; Meijs, L.C. Congruence in corporate social responsibility: Connecting the identity and behavior of employers and employees. Journal of Business Ethics 2017, 143, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duane Hansen, S.; Dunford, B.B.; Alge, B.J.; Jackson, C.L. Corporate social responsibility, ethical leadership, and trust propensity: A multi-experience model of perceived ethical climate. Journal of Business Ethics 2016, 137, 649–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlMulhim, A.F. Knowledge management capability and organizational performance: a moderated mediation model of environmental dynamism and opportunity recognition. Business Process Management Journal 2023, 29, 1655–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshashai, D.; Leber, A.M.; Savage, J.D. Saudi Arabia plans for its economic future: Vision 2030, the National Transformation Plan and Saudi fiscal reform. British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies 2020, 47, 381–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghamdi, A.A. University social responsibility under the influence of societal changes: Students’ satisfaction and quality of services in Saudi Arabia. Frontiers in Psychology 2022, 13, 976192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F.; Avolio, B.J.; Avey, J.B.; Norman, S.M. Positive psychological capital: Measurement and relationship with performance and satisfaction. Personnel Psychology 2007, 60, 541–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papacharalampous, N.; Papadimitriou, D. Perceived corporate social responsibility and affective commitment: The mediating role of psychological capital and the impact of employee participation. Human Resource Development Quarterly 2021, 32, 251–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamovi, P. Jamovi (Version 2.3)[Computer Software]. 2022.

- Hair Jr, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage publications: 2021.

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological bulletin 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Becker, J.-M. SmartPLS 4. Oststeinbek: SmartPLS GmbH. 2022.

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. Journal of marketing research 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the academy of marketing science 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N.; Lynn, G. Lateral collinearity and misleading results in variance-based SEM: An illustration and recommendations. Journal of the Association for information Systems 2012, 13, 546–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguinis, H.; Beaty, J.C.; Boik, R.J.; Pierce, C.A. Effect size and power in assessing moderating effects of categorical variables using multiple regression: a 30-year review. Journal of applied psychology 2005, 90, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardner, W.L.; Cogliser, C.C.; Davis, K.M.; Dickens, M.P. Authentic leadership: A review of the literature and research agenda. The leadership quarterly 2011, 22, 1120–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorgievski, M.J.; Halbesleben, J.R.; Bakker, A.B. Expanding the boundaries of psychological resource theories. Journal of occupational and organizational psychology 2011, 84, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F.; Youssef-Morgan, C.M. Psychological Capital: An Evidence-Based Positive Approach. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior 2017, 4, 339–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haski-Leventhal, D.; Pournader, M.; McKinnon, A. The role of gender and age in business students’ values, CSR attitudes, and responsible management education: Learnings from the PRME international survey. Journal of Business Ethics 2017, 146, 219–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, C.B.; Sen, S.; Korschun, D. Using corporate social responsibility to win the war for talent. MIT Sloan management review 2008, 49. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | Category | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Females | 42 | 12.0% |

| Males | 307 | 88.0% | |

| Age (years) | less than 30 | 76 | 21.8% |

| 31-40 | 120 | 34.4% | |

| 41-50 | 122 | 35.0% | |

| 51-60 | 26 | 7.4% | |

| greater than 60 | 5 | 1.4% | |

| Marital Status | Married | 277 | 79.4% |

| Unmarried | 72 | 20.6% | |

| Educational Level | High School | 26 | 7.4% |

| Diploma | 14 | 4.0% | |

| Bachelors | 166 | 47.6% | |

| Masters | 109 | 31.2% | |

| Post Graduate | 34 | 9.7% | |

| Years of Experience | less than 5 | 70 | 20.1% |

| 6 to 10 | 46 | 13.2% | |

| 11 to 15 | 78 | 22.3% | |

| 16 to 20 | 60 | 17.2% | |

| 21 to 25 | 57 | 16.3% | |

| more than 25 | 38 | 10.9% | |

| Current Job Tenure | less than 5 | 105 | 30.1% |

| 6 to 10 | 51 | 14.6% | |

| 11 to 15 | 64 | 18.3% | |

| 16 to 20 | 55 | 15.8% | |

| 21 to 25 | 39 | 11.2% | |

| more than 25 | 35 | 10.0% | |

| Organizational Size | less than 50 | 60 | 17.2% |

| 51-100 | 61 | 17.5% | |

| 101-250 | 59 | 16.9% | |

| 251-500 | 49 | 14.0% | |

| more than 500 | 120 | 34.4% | |

| Industry | Information Technology | 92 | 26.4% |

| Hotel and Tourism | 86 | 24.6% | |

| Financial Services | 75 | 21.5% | |

| Education | 46 | 13.2% | |

| Others | 50 | 14.3% |

| α | CR | AVE | AL | CSRP | PE | PsyCap | SRB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AL | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.73 | 0.86 | 0.8 | 0.48 (2.86) | 0.37 (3.08) | 0.4 (3.14) |

| CSR_P | 0.9 | 0.93 | 0.68 | 0.85 | 0.82 | 0.46 (2.89) | 0.3 (3) | 0.38 (3.03) |

| PsyEmp | 0.94 | 0.95 | 0.59 | 0.5 | 0.49 | 0.77 | 0.78 (1.53) | 0.74 (3.04) |

| PsyCap | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.75 | 0.37 | 0.32 | 0.81 | 0.87 | 0.72 (2.57) |

| SRB | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.6 | 0.41 | 0.4 | 0.78 | 0.75 | 0.77 |

| Note:AL = Authentic Leadership; CSR_P = Corporate Social Responsibility Perceptions, PsyEmp = Psychological Empowerment, PsyCap = Psychological Capital, SRB = Socially responsible Behavior, CR = Composite Reliability, AVE = Average Variance Extracted. The bold values on the diagonal represents square root of AVE. Values above diagonal represents correlations among latent constructs for Fornell-Larcker criteria and values in brackets represents VIF (Variance inflation factors). Values below the diagonal are HTMT values. | ||||||||

| Direct Paths | β | P values | 95% CI | Effect Size | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | AL -> SRB | 0.01 | 0.46 | [-.11;.14] | 0 |

| H2a | AL -> PsyEmp | 0.39 | 0 | [.22;.55] | 0.08 |

| H2b | PsyEmp -> SRB | 0.38 | 0 | [.27;.50] | 0.12 |

| H3a | AL -> PsyCap | 0.13 | 0.08 | [-.01;.28] | 0.01 |

| H3b | PsyCap -> SRB | 0.43 | 0 | [.29;.53] | 0.17 |

| PsyEmp -> PsyCap | 0.76 | 0 | [.68;.84] | 1.02 | |

| Gender -> PsyEmp | -0.44 | 0 | [-.68; -.24] | 0 | |

| Gender -> SRB | 0.22 | 0.02 | [.05;.50] | 0.01 | |

| Indirect Paths | |||||

| AL -> PsyEmp -> PsyCap | 0.29 | 0 | [ 0.17;0.42] | ||

| H2c | AL -> PsyEmp -> SRB | 0.14 | 0 | [ 0.08;0.23] | |

| H3c | AL -> PsyCap -> SRB | 0.05 | 0.08 | [ 0;0.12] | |

| PsyEmp -> PsyCap -> SRB | 0.33 | 0 | [ 0.22;0.42] | ||

| H4 | AL -> PsyEmp -> PsyCap -> SRB | 0.13 | 0 | [ 0.06;0.19] | |

| Moderation | |||||

| H5a | CSR_P x AL -> SRB | 0.03 | 0.13 | [-.01;.08] | 0 |

| H5b | CSR_P x AL -> PsyEmp | 0.25 | 0 | [.16;.33] | 0.16 |

| H5c | CSR_P x AL -> PsyCap | 0.03 | 0.21 | [-.02;.10] | 0.01 |

| Moderated Mediations | |||||

| CSR_P x AL -> PsyEmp -> PsyCap | 0.19 | 0 | [ 0.13;0.25] | ||

| CSR_P x AL -> PsyEmp -> SRB | 0.09 | 0 | [ 0.06;0.14] | ||

| CSR_P x AL -> PsyCap -> SRB | 0.01 | 0.2 | [ -0.01;0.04] | ||

| CSR_P x AL -> PsyEmp -> PsyCap -> SRB | 0.08 | 0 | [ 0.05;0.11] | ||

| Note: AL = Authentic Leadership; CSR_P = Corporate Social Responsibility Perceptions, PsyEmp = Psychological Empowerment, PsyCap = Psychological Capital, SRB = Socially responsible Behavior. For control variables only significant relationships are shown. | |||||

| Q²predict | PLS-SEM_MAE | LM_MAE | R2 adj | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PsyEmp | 0.3 | 0.36 | ||

| EE_1 | 0.47 | 0.5 | ||

| EE_2 | 0.47 | 0.49 | ||

| EE_3 | 0.42 | 0.47 | ||

| EE_4 | 0.44 | 0.51 | ||

| EE_5 | 0.48 | 0.57 | ||

| EE_6 | 0.45 | 0.53 | ||

| EE_7 | 0.49 | 0.5 | ||

| EE_8 | 0.51 | 0.55 | ||

| EE_9 | 0.49 | 0.5 | ||

| EE_10 | 0.48 | 0.52 | ||

| EE_11 | 0.45 | 0.5 | ||

| EE_12 | 0.47 | 0.51 | ||

| PsyCap | 0.19 | 0.63 | ||

| PC1 | 0.46 | 0.48 | ||

| PC2 | 0.46 | 0.47 | ||

| PC3 | 0.45 | 0.47 | ||

| PC4 | 0.45 | 0.48 | ||

| PC5 | 0.5 | 0.53 | ||

| PC6 | 0.47 | 0.5 | ||

| PC7 | 0.45 | 0.46 | ||

| PC8 | 0.5 | 0.53 | ||

| PC9 | 0.46 | 0.49 | ||

| PC10 | 0.48 | 0.5 | ||

| PC11 | 0.48 | 0.48 | ||

| PC12 | 0.51 | 0.52 | ||

| SRB | 0.19 | 0.61 | ||

| SRB_1 | 0.46 | 0.52 | ||

| SRB_2 | 0.47 | 0.49 | ||

| SRB_3 | 0.52 | 0.59 | ||

| SRB_4 | 0.53 | 0.56 | ||

| SRB_5 | 0.51 | 0.56 | ||

| SRB_6 | 0.55 | 0.61 | ||

| SRB_7 | 0.5 | 0.55 | ||

| SRB_8 | 0.48 | 0.49 | ||

| SRB_9 | 0.46 | 0.51 | ||

| SRB_10 | 0.48 | 0.5 | ||

| SRB_11 | 0.56 | 0.59 | ||

| SRB_12 | 0.5 | 0.55 | ||

| SRB_13 | 0.48 | 0.55 | ||

| SRB_14 | 0.52 | 0.59 | ||

| SRB_15 | 0.5 | 0.55 | ||

| Note:, PsyEmp = Psychological Empowerment, PsyCap = Psychological Capital, SRB = Socially responsible Behavior. | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).