1. Introduction

According to the United Nations (UN) Convention on Child Rights, all infants and children are entitled to a healthy diet. The foundation of healthy growth and development, a healthy future generation, baby and child survival, and national development is infancy and young child feeding (IYCF) [

1]. Mothers naturally breastfeed their children, which has many advantages for the child, the mother, and society [

2]. It lowers the chance of infection, improves cognitive development and level of schooling, and protects against cancer, diabetes, and obesity in mothers [

1,

3]. Furthermore, breastfeeding preserves skin-to-skin contact, which helps the mother’s skin microbes safely colonize the newborn’s skin and protects against hypothermia [

4]. Thirty million newborns need special medical care, of which 20.5 million have low birth weight every year, and this is the major cause of morbidity and mortality in the neonatal period [

5,

6]. Research has shown that mother’s own milk is the best source of nutrition for newborns. It plays a critical role in protecting the health and development of preterm and very low birth weight (VLBW) infants and lowers the risk of developing necrotizing enterocolitis, late-onset sepsis, and chronic diseases [

7]. Breastfeeding can prevent approximately 823000 child deaths per year globally because of its rich composition [

3,

8].

For best practice management of premature and VLBW newborns; the Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI) has established guidelines based on 10 steps to support successful breastfeeding [

9]. These steps ensure that mothers receive timely support after delivery to ensure they can establish breastfeeding and provide optimal feeding for the best health outcomes for both their infants and themselves [

9,

10]. Kangaroo Mother Care (KMC), continuous skin-to-skin care between mother and baby, has been implemented in South Africa in the care protocol for preterm and low birth weight infants to reduce mortality, strengthen the mother-child bond, ensure breastfeeding and its exclusivity, and reduce the length of hospital stay [

11,

12].

Unfortunately, the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) is a stressful environment for mothers to initiate and maintain an optimal breast milk supply [

13]. Anxiety, maternal/infant separation, lack of knowledge and support, especially related to early and frequent expressions of breast milk, and hospital policies contribute to this [

9].

When a mother is unable to provide her own milk, donor human milk (DHM) is the preferred feeding strategy for preterm and very low birth weight infants [

14]. The main purpose is to provide a “bridge to breastfeeding” to promote, protect and support breastfeeding while the mother builds up her own supply. It should be noted that DHM is nutritionally inferior compared to preterm mothers’ own milk because the breast milk of a mother who gave birth prematurely is more concentrated in proteins and higher in secretory IgA and growth factors because her mammary gland is immature, allowing the passage of more proteins in the milk, making the composition different from DHM [

15]. DHM generally comes from mothers who gave birth at term, but the process of pasteurization and storage also contributes to the loss of certain important components of milk [

16]. Early enteral feeding of the newborn with breast milk within the first hours of life is recommended.

Encouragement, counseling, and support from health workers, nurses, and peer supporters improve breastfeeding initiation among mothers of preterm and VLBW infants during the first days after birth and have a positive impact on the achievement of exclusive breastfeeding [

17]. The latest recommendations are that healthcare professionals develop empathic relationships with mothers while offering emotional support, information, and technical advice on lactation [

18]. There is a danger that using DHM to feed VLBW infants is more convenient than the time it takes to provide lactation support to mothers during the first days after birth [

19].

In a KMC unit in South Africa, mothers of VLBW infants were trained on how to feed their infants. First, how to express their own milk and feed via tube feeding and ways to breastfeed when the infant is able to latch to the breast [

20]. Researchers in Tanzania found that mothers of LBW infants did not receive adequate education and breastfeeding support in a NICU; consequently, they found difficulties in establishing and sustain exclusive breastfeeding and understanding its importance [

21,

22]. Another study conducted in Colombia found that despite the busy schedule of nurses, the mothers had individualized breastfeeding support to guide them on the feeding practices of their infant [

23]. Mothers should receive adequate discharge preparation and support after discharge because the transition from the NICU to home remains a big challenge for them.

This review is based on the belief that by understanding the breastfeeding experiences of mothers of VLBW infants, steps could be taken to improve lactation support, which could have a positive impact on the breastfeeding rate. A high rate of breastfeeding could potentially reduce neonatal deaths in low- and middle-income countries and will contribute to achieving the 2030 sustainable development goals of reducing neonatal mortality to 12 per 1000 live births (SDG Target 3.2) and ending malnutrition (SDG Target 2.2) [

24]. This review examines factors influencing the mother’s ability to produce breast milk and sustain breastfeeding.

2. Methods/Design

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Metanalyses (PRISMA) will be followed during this study. This review protocol was created and submitted to PROSPERO for registration. The 2020 PRISMA statement will be followed in the following review. The review is planned to begin in July 2024 and be completed by January 2025.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Cross-sectional studies, cohort studies, case-control studies, and randomized controlled trials (RCTs) will be included in the review. The relationship between the outcomes (exclusive breastfeeding) and the measured exposure (support for breastfeeding) will be estimated in all investigations. These estimates are computed or measurable. The Participants, Interventions, Comparisons, Outcomes (PICOS) approach and the research type from each study will be identified and used in the systematic review. The PICOS framework serves as the basis for the inclusion and exclusion criteria, which are outlined in

Table 1.

The study population will be VLBW (birth weight <1,500 g) infants and their mothers. The findings of this study will investigate the relationship between exclusive breastfeeding and breastfeeding support. Exclusive breastfeeding is advised for six months and up to two years of age [

25]. From six months onward, it is advised to introduce soft foods and various liquids, besides formula, breast milk [

26]. The WHO guidelines for infant feeding will be used to categorize the study results.

Studies on VLBW (birth weight <1,500 g) infants and their mothers in their sample will be included. Studies that include only term newborns or that solely detail neonates admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) without identifying and/or separately evaluating outcomes for VLBW infants will be excluded for consideration. Studies that examine the efficacy of initiatives to encourage breastfeeding (either expressed or direct milk feeding) will be included in this review. This review does not include reviews from high-income settings.

The rates of exclusive breastfeeding at discharge and six months after discharge are our expected key outcomes. Studies that do not report at least one of these results will be excluded. Studies that do not collect primary data (such as reviews, commentaries, letters to the editor, or research protocols) will also be excluded.

Search Strategy

Searches will be conducted on MEDLINE Ovid via EBSCOhost, Web of Science, PubMed, Cochrane Library, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), the WHO Global Index Medicus, Google Scholar, and WILEY online Library). Papers published in 2014 and up to the current search date will be covered by our search.

In addition to searches, gray literature sources, peer-reviewed articles and reference lists of papers will be submitted for assessment and discussion with subject matter experts. The following search terms: breastfeeding, exclusive breastfeeding, very low birth weight, breastfeeding support, donor human milk, LMIC will be used.

To improve our search approach, we first looked through PubMed to identify relevant search phrases and best practices. Using MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) from PubMed, we methodically selected search phrases by carefully examining the indexing of previous relevant research and adding expert commentary. For reference, a detailed summary of the original PubMed search approach will be provided. We will also manually review the reference lists of papers that fit our predetermined criteria. The final assessment will include extensive documentation detailing the search approach for every database used in the study. The purpose of this documentation is to make the search process more repeatable and to provide clear insight into the search plan and findings.

Additionally, Cabell’s Predatory Reports inside Cabell’s Scholarly Analytics will be consulted to guarantee the integrity of the chosen studies. This stage is crucial to ensure that none of the research that made up the final selection and was published in open-access journals has any warning signs of being possible predatory publications.

Study Selection and Screening

To expedite the review process, Veritas Health Innovation’s Covidence systematic review software or EndNote Software 2020 will be used. The deduplication process is handled automatically by this program, which also enables blind screening of all entries found by the database search. After duplicated studies have been removed, two reviewers will independently assess the titles and abstracts based on the predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Articles that do not satisfy the specified requirements will not be considered for review.

Disputes will be settled through debate, and if differences persist, a third reviewer will be available to render a judgment. The two reviewers independently evaluate the full texts of these studies, with the third reviewer on hand to offer a second opinion if disagreements arose over eligibility up until a consensus is established.

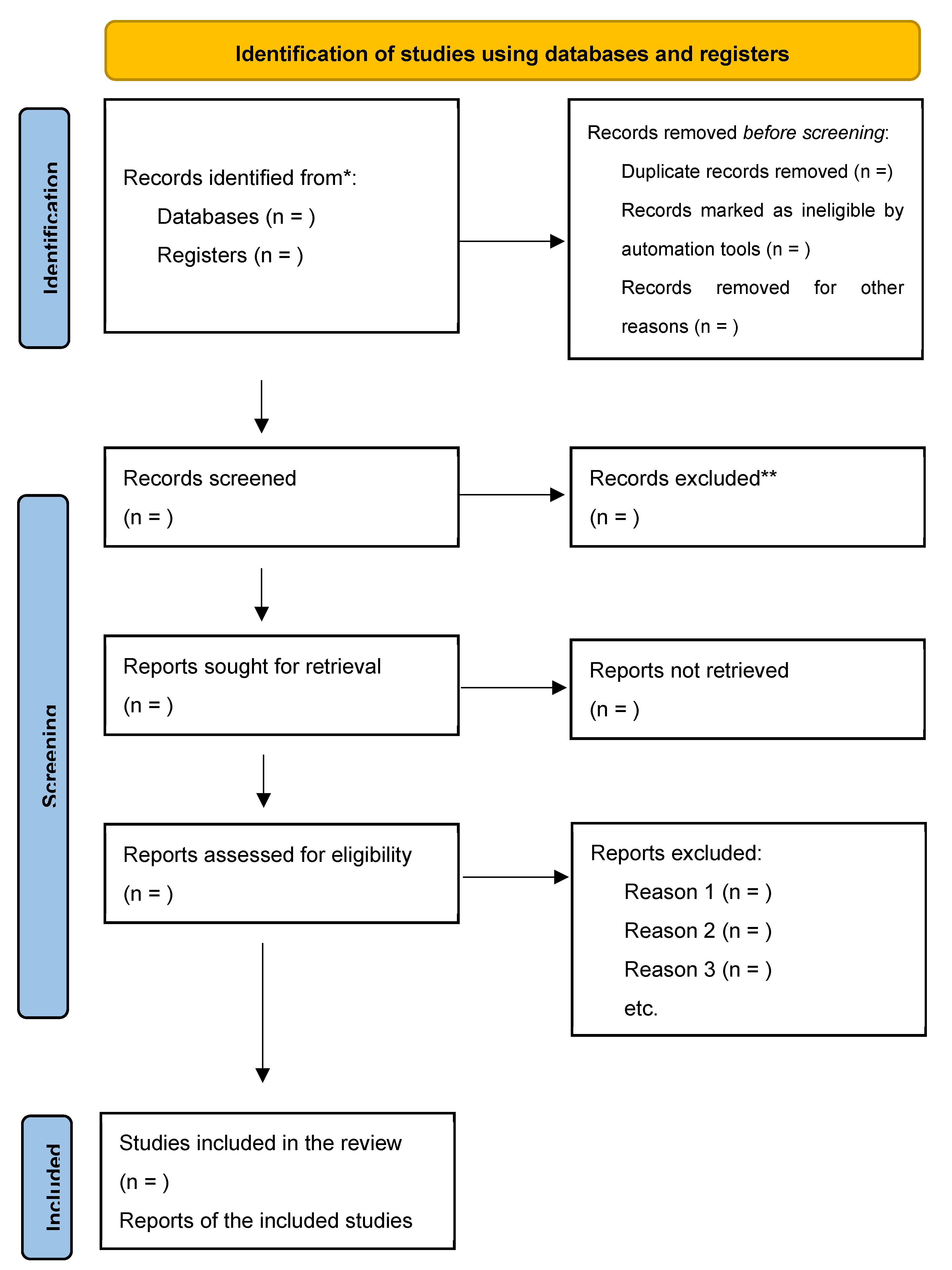

Complete documentation of the screening and selection procedure will be maintained, along with the reasoning behind the exclusion of full-text studies that did not meet the requirements. From this documentation, a PRISMA 2020 flow diagram will be created to provide a clear visual representation of the study selection process.

Data Extraction and Management

A pilot form will be used to extract the data. Each study that satisfies the qualifying requirements will have its data extracted by two researchers working separately. A third researcher will be consulted to resolve any inconsistencies that may occur. Ms. Excel will be used to build a data extraction sheet (Microsoft, Redmond, WA). From the full texts that will be included, the two reviewers will separately extract data for the sheet. The study design, sample size, nation, intervention, comparison, and quantitative results data are among the details that will be extracted. The two reviewers will discuss to settle any disagreements. Information from each study will be collected throughout the data extraction process, such as the primary author’s surname, year of publication, classification of low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), study design, key outcome measures, sample size, participant age, length of breastfeeding, nursing support, and effect size (odds ratio/risk ratio, RR) with mean difference (MD), if available. An internet source will be cited for the LMIC classification.

Output

A PRISMA flow diagram that includes the search results, and a summary of the study selection procedure will be included in the research (See

Figure 1). A comprehensive table highlighting the features of the included research will also be supplied along with the study quality ratings. The analysis and summary of the factors influencing exclusive breastfeeding found in the research will be the main goals of the finding’s synthesis. This synthesis provides an overview of the variables affecting feeding practices of VLBW infants in LMICs during the study period.

Quality Assessment and Risk of Bias in the Primary Study

Newcastle–Ottawa scale (NOS) will be used to assess the quality of evidence and risk of bias in cohort and case-control studies [

28]. An adapted version of the NOS will be used to evaluate cross-sectional studies. Good inter-rater reliability and validity are acknowledged for the NOS. This tool assesses, in accordance with the study type, participant selection, group comparability, and exposure or results [

29]. If a study satisfies the requirements, it is assigned a score for each item in the three categories; cross-sectional studies are limited to 10 points, whereas cohort studies are limited to nine [

28,

29]. To determine the risk of bias in systematic reviews, it is essential to evaluate the internal validity of primary studies. Although using NOS in non-randomized studies might be more difficult and subjective than in randomized controlled trials (RCTs), it is still the most used method for these types of studies. The quality review tool Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) will be used for RCTs [

30]. Both writers will reread the inclusion criteria and discuss any discrepancies in grades.

Measurement of Outcome Variables

The outcome variables in this review are as follows: timely initiation of breastfeeding (TIBF), which is the percentage of babies who start breastfeeding in the first hour following delivery [

31]. The percentage of babies that are exclusively breastfed from birth to six months of age is known as exclusive breastfeeding [

32].

Analysis and Data Synthesis

To investigate the relationship between breastfeeding support, donor human milk, and breastfeeding duration, descriptive analysis will be performed. Comprehensive narrative explanations and condensed data given in the tables will both be included in this analysis. Utilizing Review Manager (RevMan 5), a meta-analysis based on the Mantel-Haenzel random-effects model will be conducted to investigate the impact of interventions on exclusive breastfeeding rates at discharge (main outcomes) and 6 months postpartum (secondary outcomes).

The effect sizes will be presented as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and forest plots will be produced [

33]. A high degree of between-study heterogeneity is defined as I

2 > 50%. The I

2 test is used to quantify the amount of unexplained heterogeneity [

34]. Funnel plots are used to estimate publication bias for outcomes involving more than 10 trials [

35]. Primary outcomes will be examined through sub analyses based on the type of intervention, study location (LMICs), and VLBW infants alone. Sensitivity analysis will examine whether limiting the sample to only RCTs, high-quality studies, and studies published within the previous 10 years affected the impact of interventions on breastfeeding duration.

Subgroup Analysis

We intend to perform subgroup analysis using a stratified approach based on the study’s regional states and residency locations.

Bias Minimization

To guarantee the inclusion of all pertinent research that satisfies our predetermined criteria, the review will carefully investigate several databases. The R package will be used to measure publication bias using Begg’s or Egger’s tests and funnel plots, which show effect sizes [

35], as well as Trim and Fill analysis. To reduce bias, the NOS and GRADE tools will be used by both authors to assess the quality of primary studies [

36]. Any differences in grading will be settled by discussion. Sensitivity analysis will be repeated for the meta-analysis, but only for studies that have been rated as high quality. The team’s statistician will supervise the statistical analyses, which will be performed using Stata V.16 (Stata Corp).

Patient and Public Involvement

At no point throughout the study will patients or the public be involved. The primary purpose of the proposed study is to review published data that can be accessed via designated electronic databases.

Ethics and Dissemination

Ethics approval is not required for this review because it excludes original data collection. We plan to disseminate the results of our systematic review and meta-analysis by publishing them in a peer-reviewed journal and giving talks at national or international scientific/ public health conferences and research symposia on child health in LMICs.

3. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, our review is the only one that considers a thorough investigation of exclusive breastfeeding in VLBW infants in low- and middle-income countries regarding breastfeeding assistance methods. LBW refers to a birth weight of less than 2500 g, and VLBW is defined as less than 1500 g [

37]. Several factors may contribute to low birth weight, including restricted intrauterine growth, premature delivery (less than 37 gestational weeks), or both [

38]. Most LBW babies (>90%) are born in low- or middle-income nations (LMICs) [

39]. There are reports of feeding difficulties, impediments to exclusive breastfeeding, and delays in the start of feeding [

31,

40,

41]. The WHO updated its guidelines in 2022 with an emphasis on providing care for preterm and low birth weight (LBW) newborns; nonetheless, there is still a lack of advice, especially regarding feeding and nutrition for this susceptible population [

5].

The rates of breastfeeding continuation in LMICs were increased by peer support interventions and health worker counseling during the prenatal and breastfeeding phases [

42]. However, with the shortage of health workers and their heavy workload, it may be more challenging to promote and support optimal feeding in the absence of appropriate documentation and handover between clinicians [

43]. Encouraging mothers to express their milk as soon as possible after giving birth is a significant step toward increasing the amount of breastmilk produced, as it is essential for the baby’s health and delaying breastfeeding can have an impact on milk production.

We are aware of no previous review that considers VLBW mothers’ experiences nursing their child in a low-income country. It is verified that the number of LBW babies is higher in LMIC than in high-income countries (HIC). Our review will provide evidence that breastfeeding support methods provided to mothers are a contributing factor in the exclusive breastfeeding rate. In addition, it will mention any gaps and offer suggestions for further research on breastfeeding assistance.

4. Conclusion

In terms of timing and frequency of breastfeeding assistance, this systematic review will emphasize the strategies used to support breastfeeding during the neonatal period and identify potential influencing factors. The knowledge gathered from the review will raise awareness, direct advancements, and shape future breastfeeding assistance programs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.M.B and A.G-A.M.; writing-original draft preparation, F.M.B and A.G-A.M.; writing—review and editing, F.M.B., A.G-A.M., P.R. and A.C.; supervision, P.R. and A.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research has received no funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the College of Health Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Victora, C.G., et al., Breastfeeding in the 21st century: epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. The lancet, 2016. 387(10017): p. 475-490. [CrossRef]

- Sosseh, S.A., A. Barrow, and Z.J. Lu, Cultural beliefs, attitudes and perceptions of lactating mothers on exclusive breastfeeding in The Gambia: an ethnographic study. BMC Women’s Health, 2023. 23(1): p. 18. [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, A.S., et al., Breastfeeding Impact on Cancer in Women: A Systematic Review. Barw Medical Journal, 2024.

- Gupta, P., et al., Evidence-based consensus recommendations for skin care in healthy, full-term neonates in India. Pediatric Health, Medicine and Therapeutics, 2023: p. 249-265. [CrossRef]

- Darmstadt, G.L., et al., New World Health Organization recommendations for care of preterm or low birth weight infants: health policy. EClinicalMedicine, 2023. 63. [CrossRef]

- Jana, A., et al., Relationship between low birth weight and infant mortality: evidence from National Family Health Survey 2019-21, India. Archives of Public Health, 2023. 81(1): p. 28. [CrossRef]

- Parker, M.G., et al., Promoting human milk and breastfeeding for the very low birth weight infant. Pediatrics, 2021. 148(5). [CrossRef]

- Binns, C. and M.K. Lee, Public health impact of breastfeeding, in Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Global Public Health. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Li, X., et al., Mothers’ experiences of breast milk expression during separation from their hospitalized infants: a systematic review of qualitative evidence. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 2024. 24(1): p. 124. [CrossRef]

- James, L., L. Sweet, and R. Donnellan-Fernandez, Self-efficacy, support and sustainability–a qualitative study of the experience of establishing breastfeeding for first-time Australian mothers following early discharge. International breastfeeding journal, 2020. 15: p. 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Adejuyigbe, E., et al., Evaluation of the impact of continuous Kangaroo Mother Care (KMC) initiated immediately after birth compared to KMC initiated after stabilization in newborns with birth weight 1.0 to< 1.8 kg on neurodevelopmental outcomes: Protocol for a follow-up study. Trials, 2023. 24(1): p. 265. [CrossRef]

- Williams, S., Outcomes of preterm infants discharged early from a South African kangaroo mother care unit. 2019.

- Leong, M., et al., Skilled lactation support using telemedicine in the neonatal intensive care unit. Journal of Perinatology, 2024: p. 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Kashyap, V. and S.G. Choudhari, Unlocking the Potential: A Systematic Literature Review on the Impact of Donor Human Milk on Infant Health Outcomes. Cureus, 2024. 16(4). [CrossRef]

- Van Belkum, M., L. Mendoza Alvarez, and J. Neu, Preterm neonatal immunology at the intestinal interface. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences, 2020. 77: p. 1209-1227. [CrossRef]

- Arslanoglu, S., et al., Recommendations for the establishment and operation of a donor human milk bank. Nutrition Reviews, 2023. 81(Supplement_1): p. 1-28. [CrossRef]

- Bengough, T., et al., Factors that influence women’s engagement with breastfeeding support: A qualitative evidence synthesis. Maternal & child nutrition, 2022. 18(4): p. e13405. [CrossRef]

- Hoyt-Austin, A.E., et al., Physician personal breastfeeding experience and clinical care of the breastfeeding dyad. Birth, 2024. 51(1): p. 112-120. [CrossRef]

- Coyne, R., et al., Influence of an Early Human Milk Diet on the Duration of Parenteral Nutrition and Incidence of Late-Onset Sepsis in Very Low Birthweight (VLBW) Infants: A Systematic Review. Breastfeeding Medicine, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Madiba, S., P. Modjadji, and B. Ntuli. “Breastfeeding at Night Is Awesome” Mothers’ Intentions of Continuation of Breastfeeding Extreme and Very Preterm Babies upon Discharge from a Kangaroo Mother Care Unit of a Tertiary Hospital in South Africa. in Healthcare. 2023. MDPI. [CrossRef]

- Tada, K., et al., Evaluation of breastfeeding care and education given to mothers with low-birthweight babies by healthcare workers at a hospital in urban Tanzania: a qualitative study. International breastfeeding journal, 2020. 15: p. 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Vesel, L., et al., Facilitators, barriers, and key influencers of breastfeeding among low birthweight infants: a qualitative study in India, Malawi, and Tanzania. International Breastfeeding Journal, 2023. 18(1): p. 59. [CrossRef]

- Abugov, H., et al., Barriers and facilitators to breastfeeding support practices in a neonatal intensive care unit in Colombia. Investigación y educación en enfermería, 2021. 39(1). [CrossRef]

- Bossman, E., The post-2015 development agenda: progress towards sustainable development goal target on maternal mortality and child mortality in limited resource settings with mHealth interventions: a systematic review in Sub-Saharan Africa and Southern Asia. 2019, UiT Norges arktiske universitet.

- Søegaard, S.H., et al., Exclusive Breastfeeding Duration and Risk of Childhood Cancers. JAMA network open, 2024. 7(3): p. e243115-e243115. [CrossRef]

- Bafila, P., et al. Nutritional and compositional aspects of complementary feeding. in AIP Conference Proceedings. 2024. AIP Publishing.

- Page, M.J., et al., The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Bmj, 2021. 372.

- Sun, B., et al., Prevalence and risk factors of early postoperative seizures in patients with glioma: A protocol for meta-analysis and systematic review. Plos one, 2024. 19(4): p. e0301443. [CrossRef]

- Abouelmagd, M.E., et al., Adverse childhood experiences and risk of late-life dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 2024: p. 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Piggott, T., et al., Grading of recommendations, assessment, development and evaluations concept 7: issues and insights linking guideline recommendations to trustworthy essential medicine lists. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 2024. 166: p. 111241.

- Makwela, M.S., et al., Barriers and enablers to exclusive breastfeeding by mothers in Polokwane, South Africa. Frontiers in global women’s health, 2024. 5: p. 1209784. [CrossRef]

- Aboagye, R.G., et al., Mother and newborn skin-to-skin contact and timely initiation of breastfeeding in sub-Saharan Africa. Plos one, 2023. 18(1): p. e0280053. [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, E., et al., Maternal circulating leptin, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, and interleukine-6 in association with gestational diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gynecological Endocrinology, 2023. 39(1): p. 2183049. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, M., et al., Quantifying replicability of multiple studies in a meta-analysis. The Annals of Applied Statistics, 2024. 18(1): p. 664-682. [CrossRef]

- Afonso, J., et al., The perils of misinterpreting and misusing “publication bias” in meta-analyses: An education review on funnel plot-based methods. Sports medicine, 2024. 54(2): p. 257-269. [CrossRef]

- Kolaski, K., L.R. Logan, and J.P. Ioannidis, Guidance to best tools and practices for systematic reviews. British Journal of Pharmacology, 2024. 181(1): p. 180-210. [CrossRef]

- Atriadewi, H.S., Y. Hafidh, and I. Andarini, Newborn Calf Circumference to Identify Low Birth Weight Neonates. Journal of Maternal and Child Health, 2024. 9(1): p. 97-104. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.Y., et al., Short-term neonatal and long-term neurodevelopmental outcome of children born term low birth weight. Scientific Reports, 2024. 14(1): p. 2274.

- Vats, H., et al., Association of Low Birth Weight with the Risk of Childhood Stunting in Low-and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Neonatology, 2024. 121(2): p. 244-257. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M., et al., Factors associated with delayed initiation and non-exclusive breastfeeding among children in India: evidence from national family health survey 2019-21. International Breastfeeding Journal, 2023. 18(1): p. 28. [CrossRef]

- Vizzari, G., et al., Feeding difficulties in late preterm infants and their impact on maternal mental health and the mother–infant relationship: a literature review. Nutrients, 2023. 15(9): p. 2180. [CrossRef]

- Khatib, M.N., et al., Interventions for promoting and optimizing breastfeeding practices: An overview of systematic review. Frontiers in Public Health, 2023. 11: p. 984876. [CrossRef]

- Vernekar, S.S., et al., Lessons learned in implementing the Low Birthweight Infant Feeding Exploration study: A large, multi-site observational study. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 2023. 130: p. 99-106. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).