1. Introduction

This article contributes to concepts of causation and terminology for work-related musculoskeletal problems based on findings from a survey of United States employers regarding the musculoskeletal problems experienced recently by their employees

1.1. Background

The field of occupational safety and health (OSH) encompasses a multitude of workplace hazards and several professional specialties, including industrial hygiene, safety/injury prevention, occupational medicine, occupational health nursing, and ergonomics. Ergonomics fits into these specialties because many of the occupational injuries and illnesses involve the musculoskeletal systems, and ergonomic specialists have training and education on the human biomechanics and physiology used to design tasks to match the capabilities of the workers who perform those tasks [

1,

2,

3,

4].

The separation of professional specialties has led to differences in terminology and the associated concepts. Terms found in scientific and professional literature include musculoskeletal problems, disorders, injuries, and illnesses. Of these, the broadest, and least specific is musculoskeletal problem—it does not imply a known cause or specific diagnosis [

5,

6]. For the concept that a musculoskeletal problem resulting from a single incident, the term musculoskeletal injury is appropriate [

7,

8]; for the concept that a musculoskeletal problem resulted from long-term, repeated stress on an anatomical part, the term musculoskeletal disorder is popular [

9]. And, if the musculoskeletal disorder developed from employment, the adjective “work-related “ is an appropriate modifier of injury or disorder. In workers’ compensation systems, a claim for a musculoskeletal problem might be called an injury, illness, or disease, depending on the applicable statute [

10].

In the musculoskeletal area, different concepts and terms can affect the way national research organizations prioritize their risk-reduction research efforts for preventing the occurrence of work-related musculoskeletal problems and for treating and rehabilitating cases that already exist. A second concern is the differences among professional specialists using different concepts and terms to grow their role in the musculoskeletal area.

1.2. Controversy

Authors of article about work-related musculoskeletal problems recognize two views of causation [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Regarding the single event view, the concept is that musculoskeletal damage comes from a single, intense exertion that exceeds the physical capability of the person’s body part. The contrasting perspective is that a person working a physically stressing task, will gradually wear down their spine, ligaments, tendons, and or other anatomical elements until eventually the capability of that body part can no longer perform the task without pain [

4].

Information on how these concepts are understood may be gleaned from results of a survey of U.S. employers conducted by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) [

9,

10,

11,

12]. The employer-respondents were asked to describe each injury, illness, and fatality their employees experienced during the recent 2-year period according to categorical descriptors of interest [

14,

15]. The survey items about overexertion cases ask if the musculoskeletal disorder resulted from a single episode or from multiple episodes. Among the descriptor attributes is the event or exposure (E&E) directly preceding the injury, illness, or fatality. Categories for E&E accompany the 8-page survey. Responses may shed light on how employers view the source of the musculoskeletal problems incurred by their employees.

1.3. Aim

The aim of this short communication is to share findings from an examination of the recent BLS survey about occupational musculoskeletal cases, and more specifically, about whether employers regard causes of the musculoskeletal problems as being the result of a single exposure or from multiple exposures.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

BLS conducts a biennial survey of employers and makes results available through their website (BLS.gov). BLS personnel use a sampling strategy to select employers to represent the larger population of employers. The survey asks for information on each case as well as employment data needed to compute incidence rates and to categorize the cases. The cases used for this paper were nonfatal occupational injury and illness cases involving days away from work, restricted activity, or job transfer. These are commonly referred to as DART cases. The fatal cases excluded from this project were reported in an earlier paper [

15]. Results for the years 2021–2022 are shared with the public on BLS web sites in spreadsheets, graphics, and commentary.

Survey respondents were asked to report each case using codes in a hierarchical structure using four placeholders for numeric codes. The left-most placeholder, for the event and exposure (E&E) category, contains a single-digit code for one of seven categories. The E&E codes are the most useful categories related to causation and prevention because they inform about situations immediately preceding the harmful event [

15]. The number seven indicates the case was in the “overexertion and bodily reaction” category. The second placeholder contains a code indicating subcategories applicable to the tier above, i.e. the Level I.

Table 1 lists the Level I and applicable Level II categories and code numbers.

2.2. Methods

The initial analysis of the E&E category 7 cases involved identifying and determining the portion of cases in each level II category. The published dataset consisted of number of cases the BLS statisticians projected for the entire U.S. from the survey sample. Further analyses focused on third and fourth level responses, whichever had the most relevance to the study aim. Some of items relevant to musculoskeletal problems asked employers to choose between the cause being a single exposure or multiple exposures. Per a previous recommendation [

15], a graphical form of presentation was created to concisely convey the findings.

3. Findings

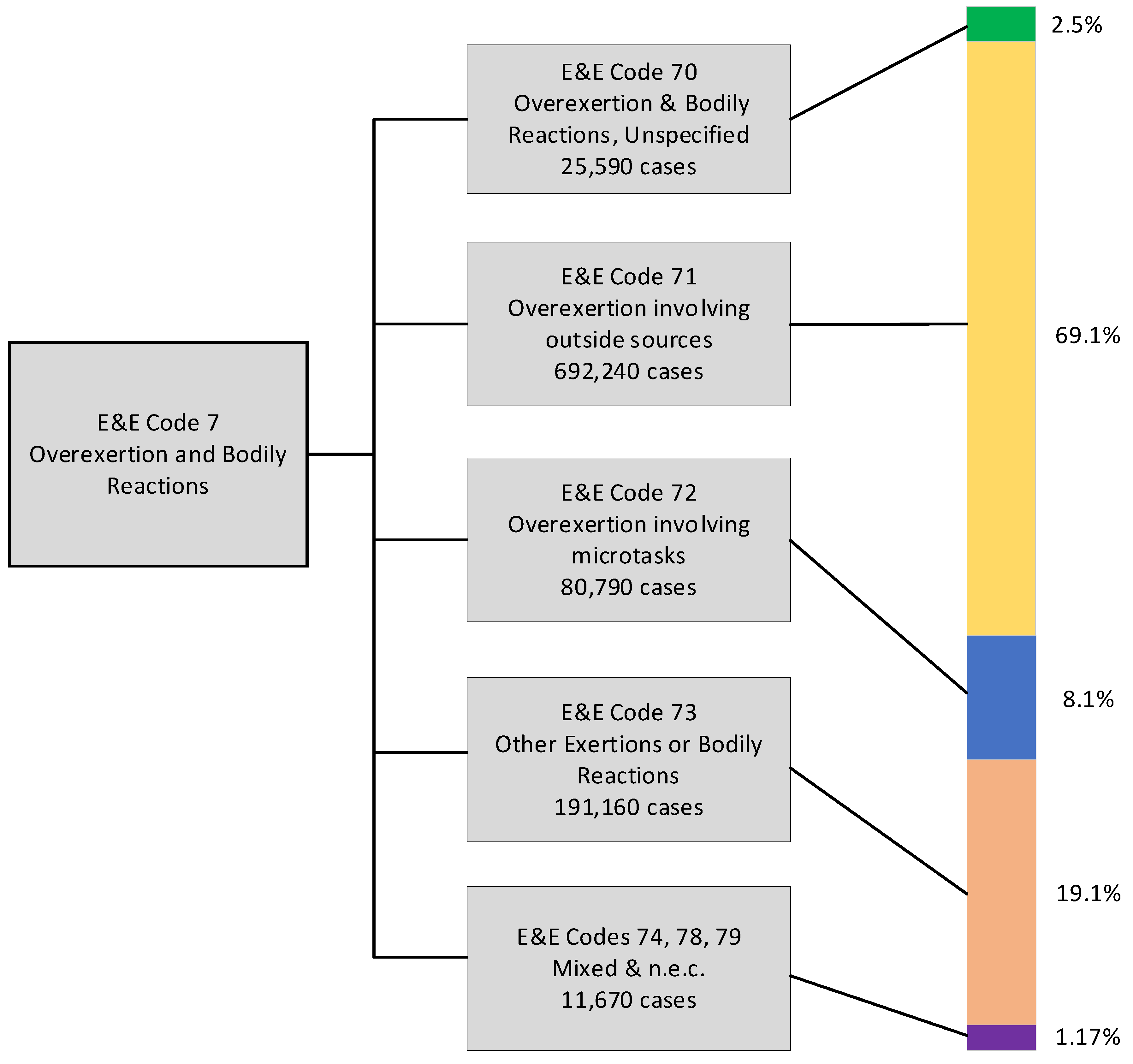

The graphic depiction in

Figure 1 shows essential findings in the BLS Division 7, grouped into subcategories 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 78, and 79. Subcategories 74, 78, and 79 are depicted together because individually, their combined contributions constituted only 1.17% of the total.

The official title of subcategory 71, “Overexertion involving outside source”, is essentially what the industrial engineering and physical ergonomics communities call manual materials handling [

2,

3]. Cases in category 7 compose 69 percent of the E&E Code 7 cases in the national data set. This broad category has third-level subcategories for lifting, lowering, pushing, pulling, turning, throwing, catching, and carrying. The largest subcategory, lifting, offers a fourth level for indicating if the injury resulted from a single episode or from repetition of multiple episodes of lifting. Respondents marked the single episode choice over 12 times more frequently than the multiple episode choice (273,349 versus 21,840 cases).

Category E&E 73 contributed the second most frequent cases (19%) of all E&E Code 7 cases. The cases in E&E 73 include bending, crawling, reaching, and twisting. Within this conglomerate subcategory, respondents marked the single episode choice over 13 times more often than the repetitive or prolonged choice (72,950 versus 5,269 cases).

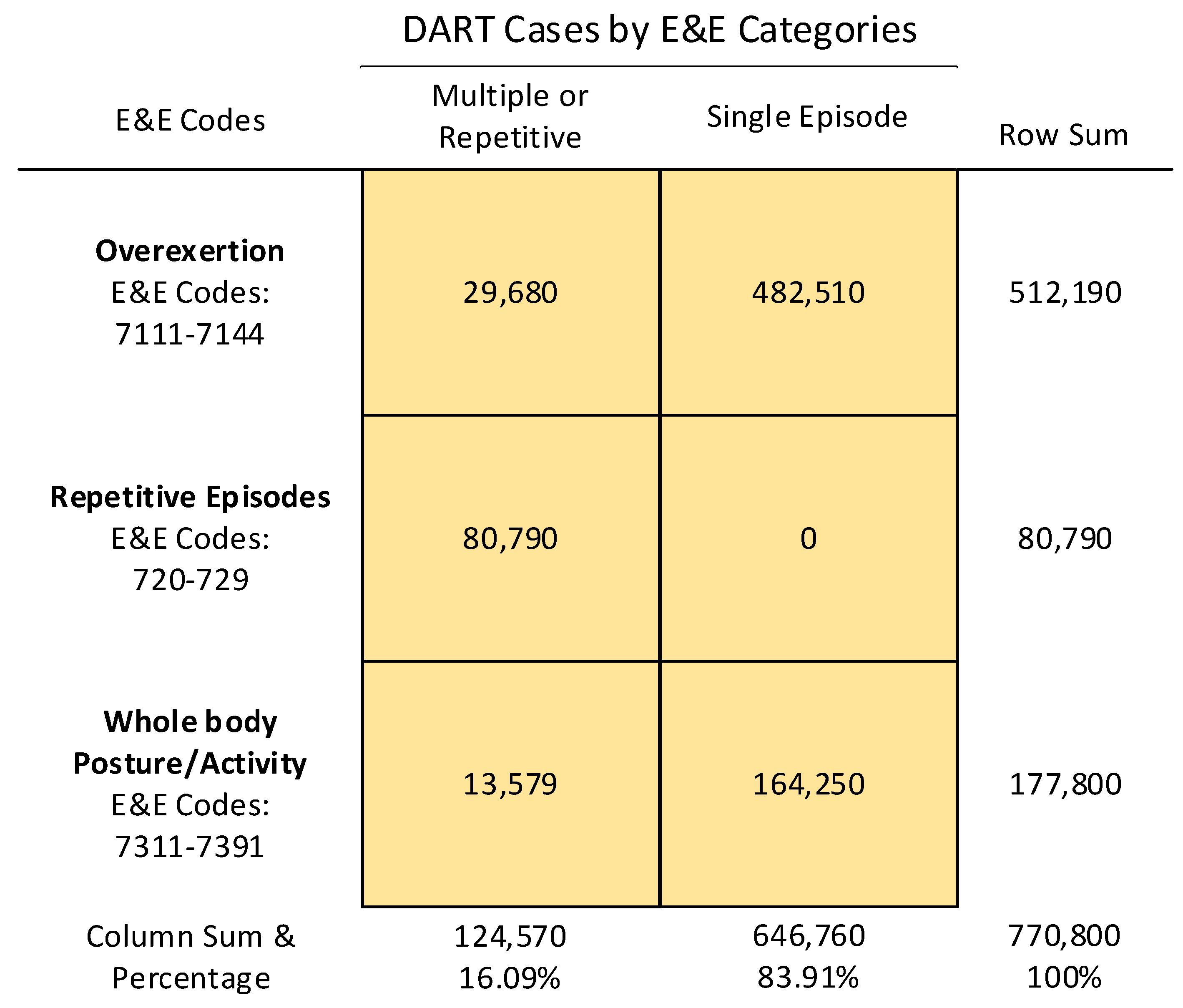

To address the controversy about how to describe occupational musculoskeletal cases, the BLS reports were examined to address the frequency of cases falling into the manual materials handling category (E&E code 71) versus repetitive activity category (E&E code 72). The findings of this process are presented in

Figure 2 below the applicable column. According to this analysis, 16% of the E&E code 7 cases were coded as caused by multiple or repetitive episodes.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

4.1. Survey Strengths and Limitations

Survey research has both strengths and limitations. A strength of surveys in general is learning about people’s attitudes, feelings, and opinions. A limitation of surveys is the design of items may be influenced by the survey developers’ opinions [

17]. Most of the BLS survey items seek factual records about the employer’s injury and illness experience. The paired choice items are somewhat different in that these items ask about the source of overexertion musculoskeletal cases being multiple episodes or single episodes. Answering involves using a mix of objective facts and subjective judgment. The subjective aspect comes from the individual responsible for recording each case in the employers ongoing injury/illness log. That individual may have some room to describe the nature of a case as, for example, a ligament sprain or a muscle strain. For purposes of the analyses reported here, the category reported by the employer’s representative is accepted as is.

To maintain objectivity, the investigator/author of this paper avoided any conflict of interest and had no reason to extract findings to promote a particular point of view.

Some findings found in the published results strengthen the confidence that the results are trustworthy. Referring to findings in

Figure 2, the upper section involving overexertion-item responses shows responders were able to distinguish the two sources of musculoskeletal cases. Respondents were split 94% for single episode to 6% for multiple episodes. The second reasons why the findings strengthen confidence in the results appears in the middle section of

Figure 2 where all items were specifically about multiple episode causes. These results indicate that 100% of respondents chose, as expected, the source was multiple episodes.

A finding supporting external consistency comes from comparing the disorders identified in the survey to the affected body parts expected from literature [

18]. An indicator of external validity would be a match between the nature of harm and body-part affected. In one part of the survey, the responding individuals indicated the nature of employee’s injury/illness; in another part of the survey responding individuals indicated the part of body affected. For cases coded as sprains, the expected body parts were joints held together with ligaments. The survey results were consistent with this expectation—the most common body parts identified were ankles (33%), knees (19%), back (13%), and wrist (11%). For cases coded as strains, the expectation was for body parts where muscles are heavily involved in significant exertions—back (51%) and shoulder (19%). Also consistent with established literature [

18], for cases coded in one of the soft tissue categories, the main body parts identified were as expected:

Bursitis: knee (43%), arm (33%), and shoulder (24%);

Stenosing tenosynovitis: hand (66%) and wrist (39%);

Other tenosynovitis: hand (39%) and wrist (38%);

Epicondylitis: arm (97%);

Other non-specified tendonitis: wrist (28%) and arm (25%); and

Ganglion or cystic tumor: wrist (64%) and hand (29%).

4.2. Conclusions

The BLS survey data provided a dataset for achieving the aim of this analyses; specifically, to share findings from an examination of the recent BLS survey about occupational musculoskeletal cases, and more specifically, about whether cases arose from a single episode or from multiple episodes. Four conclusions follow.

Conclusion 1. According to these data, the survey items on manual materials handling cases (E&E codes 7111-7114) received responses indicating approximately 6% (29,680 cases) were from multiple episodes while 94% (482,510 cases) from single episodes.

Conclusion 2. The BLS survey included some items relevant to concepts of causation for occupational musculoskeletal problems. These were the items asking if the source of a particular musculoskeletal problem was from a single episode or from multiple episodes. If source is considered a risk factor, then the analysis described here supports a finding of source as a categorical risk factor for several kinds of work-related musculoskeletal disorders. This broad conclusion is consistent with past ergonomics literature [

1,

2,

3]. On a more specific level, the conclusion involves two parts. One part is that repetitive work is a risk factor for work-related musculoskeletal disorders commonly known as work-related musculoskeletal disorders (WRMSDs). The second is that manual material handling is a risk factor for musculoskeletal injuries as defined by OSHA (see footnote to

Figure 1). Both these conclusions provide additional support for the current thinking within the ergonomics community. Any attempt to learn more about risk factors for work-related musculoskeletal disorders from the BLS survey data is limited because it lacks comparison data on workers who did not experience a musculoskeletal injury or illness.

Conclusion 3. Data presented in this article indicate that employers recognize that injuries from manual materials handling may come from single events (94%) or from repetitive stressors (6%). The term injury is appropriate for the 94 percent of musculoskeletal harms resulting from a single incident, while the term injury is inappropriate from musculoskeletal harms resulting from repetitive stresses. For the latter, appropriate terms include disorder, syndrome, and specific medical diagnostic names.

Conclusion 4. The BLS survey data is not suitable for learning about the combined involvement of long-term wear-and-tear reducing the physical capability of body parts to a point where a common physical load exceeds the body part’s tolerance causing an onset of pain or other symptoms.

4.3. Recommendations

Based on the BLS survey findings, the author makes two recommendations for future references to occupational musculoskeletal problems. The first is. avoid using overly broad labels, like saying all work-related musculoskeletal problems are repetitive motion disorders, or that all musculoskeletal problems are caused by single, excessive biomechanical forces on a joint or related anatomical structure. The second is use terms precisely to match the sort of hazard associated with the work, specifically, for assembly line work, and other highly repetitive work, use either repetitive motion or repetitive stress to describe the hazard of long-term stress on body parts or for general, whole body manual work, use the term injury if the harm resulted from a single exertion or motion.

Author Contributions

The author, RJ, conceived the project, performed all analyses, created all graphics, and wrote all text.

Funding

This research received funding from the Montana Technological University’s Training Project Grant (T03 OH008630) from the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the author and do not represent the official views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, or the Department of Health and Human Services.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Institutional Review Board Statement

No human subjects involved.

Abbreviations:

| AJHSR |

Academic Journal of Health Sciences & Research |

| AWEH |

Annals of Work Exposure and Health |

| JOEM |

Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine |

| JOM |

Journal of Occupational Medicine |

| MLR |

Monthly Labor Review |

References

- Chengalur, S.N.; Rodgers, S.H.; Bernard, T.E. People at Work, 2nd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, New Jersey, USA, 2004; pp. 1–5.

- Karwowski, W.; Marras, W.S. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders of the upper extremities. In Handbook of Human Factors and Ergonomics, 2nd ed.; Salvendy, G.; Ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken New Jersey USA, 1997. pp. 1124-1173.

- Ayoub, M.; Dempsey, P.G.; Karwowski, W.; Manual materials handling; In Handbook of Human Factors and Ergonomics, 2nd ed. Salvendy, G.; Ed.; John Wiley & Sons, New York, USA; 1997. pp. 1085-1123.

- Bridger, R.S.; Introduction to Ergonomics, 3rd ed. Boca Raton, FL. USA. 2009; pp. 66-70. ISBN: 13-978-0-8493-7306-0.

- Vanderpool, H.E.; Friis, E.A.; Smith, B.; Harms, K.L. Prevalence of carpal tunnel syndrome and other work-related musculoskeletal problems in cardiac sonographers, JOM 1993, 35, 6, pp. 604–610. [CrossRef]

- Du, T.; Iwakiri, K.; Sotoyama, M.; Tokizawa, K. Computer and furniture affecting musculoskeletal problems and work performance in work from home during COVID-19 pandemic. JOEM 2022, 64, 11, 964–969. [CrossRef]

- Tsai, S.P.; Gilstrap, E.L.; Cowles, S.R.; Waddell, L.C.; Ross, C.E. Personal and job characteristics of musculoskeletal injuries in an industrial population. JOM 1992, 34, 6, pp. 606–612.

- Sundstrom, J.N.; Webber, B.J.; Delclos, G.L.; Herbold, J.R.; Gimeno Ruiz de Porras, D. Musculoskeletal injuries in US Air Force security forces, January 2009 to December 2018. JOEM 2021, 63, 8, 673–678. [CrossRef]

- Bao, S.; Howard, N.; Jia-Hua, L. Are work-related musculoskeletal disorder claims related to risk factors in workplaces of the manufacturing industry? AWEH 2019, 64, 2, 152-164.

- Jensen, R.C.; Bricio, F.J. Causation issues in workers’ compensation. In Handbook of Human Factors in Litigation, Noy, Y.I., Karwowski W., Eds.; CRC, Hoboken, New Jersey USA, 2005, Chapter 9.

- Putz-Anderson, V.; Grant, K.A. Fundamentals of surveillance for work-related musculoskeletal disorders. In The Occupational Ergonomics Handbook., Karwowski, W.; Marras, W.S. Eds.; CRC, Boca Raton, FL USA, 1998; pp. 1189-1203.

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Survey of occupational injuries and illnesses; In Handbook of Methods, 2023. www.bls.gov/opub/hom/soii/home.htm.

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Economic News Release (11/8/2023). Biennial case and demographic characteristics for work-related injuries and illnesses involving days away from work, restricted activity, or job transfer - 2021–22. Table R33. Number of nonfatal occupational injury and illness cases involving days away from work, restricted activity, or job transfer (DART). (http://www.bls.gov/iif/non-fatal-injuries-and-ilnesses-tables.htm), (accessed on 10 June 2024.

- Drudi, D. The quest for meaningful and accurate occupational safety and health statistics. MLR, Dec. 2015. pp.1–19. [CrossRef]

- Jensen, R.C. Occupational fatality surveillance data: Communication issues, misunderstandings, and misuses. AJHSR. 2024, 1, 2; pp. 1–10, Manuscript ID.000510.

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Survey of occupational injuries and illnesses by industry and case types. In Table 1, Incidence rates of nonfatal occupational injuries and illnesses by industry and case types, 2021-2022. http://www.bls.gov/iif/nonfatal-injuries-and-illnesses-tables.htm. (accessed on 10 June, 2024).

- Freivalds, A. Biomechanics of the upper limbs: Mechanics, modeling, and musculoskeletal injuries, 2nd Edition. CRC, Boca Raton, Florida, USA. 2011; pp. 202–212.

- Sinclair, M.A. Participative assessment. In Evaluation of Human Work, 3rd ed.; Wilson, J.R., Corlett,N. Eds.; CRC, Boca Raton, Florida, USA, 2005, pp. 83–111.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).