1. Introduction: Tracing Inventive Spirits in Siberia

This study examines healing rituals and rumours of magical assault in a Siberian territory during an extraordinary period of sociopolitical transition. In the early 2000s, beliefs in magical practices or evil “spells” and the deadly threat of “curse” (kargysh) abounded in narratives of misfortune and sickness, which shamans relayed on their clients’ behalf in Tuva Republic – an inaccessible and relatively impoverished Federal subject of the Russian Federation, which borders Northwestern Mongolia. The article draws on data collected in the course of a year’s fieldwork in Kyzyl (the capital city of Tuva). It revisits pathways and passages through which Tuvan spirits were moving in search of new opportunities for reincarnation through haunting their living relatives and visiting their shamanic successors in rituals. Central to this picture of human communities being altered by the return of uninvited and (formerly) repressed spirits and shamanic ancestors is a dark movement, involving features of ritual parasitism and extraction of souls from dead or living persons. While the shamans’ rituals function as a refuge for downtrodden spirits originating in the wilderness, Buddhism – Tuva’s national religion – promotes an alternative spiritual path of dealing with the consequences of the shamans’ propagation of spirits.

The current analysis probes an extraordinary range of indigenous religious reactions and adaptations to Russian neocolonial practices of mobilizing various spiritual resources, whether currently active or dormant, for political domination. This proposition, namely, the presence of a fundamental analogy between shamanic and political procedures of governance is crucial for the purposes of this analysis. The ethnographic cases will shed light on a ritual specialism leading to a revitalization of landscapes, which have been depleted of spiritual resources owing to “extractive” shamanic schemes sponsored by government agents (including, but not limited to, the current President of the Russian Federation, Vladimir Putin). On this basis, the theory of shamanism, which this article advances, challenges notions of the monopoly of the state’s sovereignty as the ultimate basis of power, or as a sacred canon guaranteeing the “command of the sovereign”, in modern governmental states (see Roberts 2013, for a relevant discussion). In assessing the socio-political implications of a broader field of remedial and destructive (or harmful) ritual practices, associated with popular shamans and oracles respectively, the present analysis affirms a key thesis on Siberian religions as a forum for ethno-national resilience to state-sponsored Russification and coercive political integration among the Indigenous people of the Russian North (see Balzer 2021, also 1999).

In this context, the article foregrounds an analysis of “shamanism” as a peripheral ecological power, which overlaps with ethnic frontier zones, in line with Balzer’s definition of Siberian religions as a “bulwark of potentially tenacious personal and social-cultural significance” (1999: 22). In her well-known studies of ethnic identity formation in North Russia, Balzer analyses the variety of religious adaptations and transformations that took shape in the milieu of the “Soviet (dis)Union” (ibid. 1999: 22). Based on long-term fieldwork among the Khanty, a traditionally nomadic society of reindeer breeders and hunters in the Northern Ob river region, Balzer highlights the interplay between folk Marxist-Leninist ideologies and pre-existing practices of bear ceremonialism. She argues that, rather than yielding to a vapid, materialist approach to native religion as an opiate that contributes to socioeconomic depravity, ethnic groups in this sub-Arctic area creatively merged the “sacral” doctrines of Marxism and Russian Orthodox Christianity with beliefs originating from traditional Khanty animist cosmology (ibid. 1999: 16 ff.).

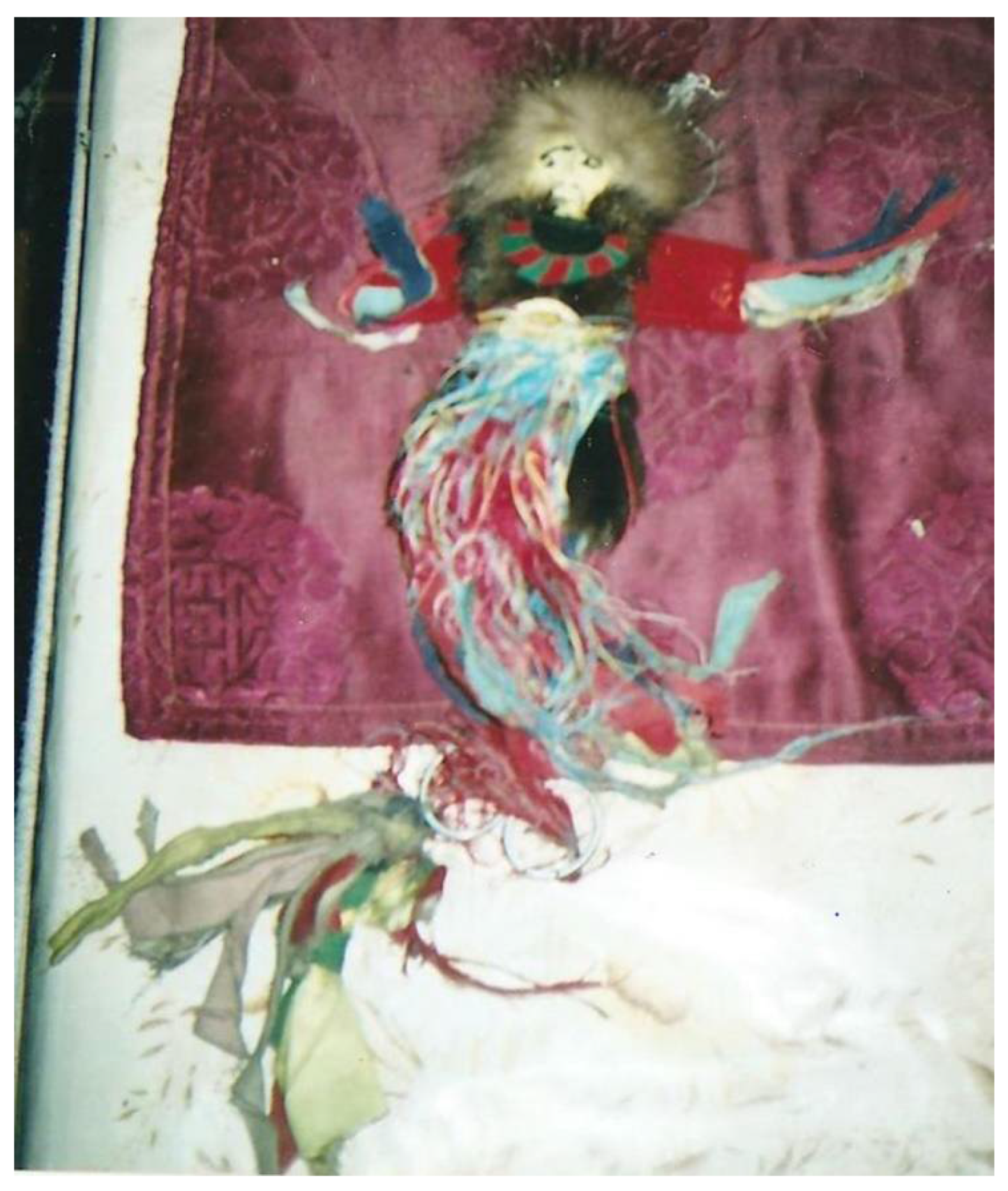

Focusing on the interplay between long-lasting shamanic symbols and new kinds of social anxiety, the current analysis identifies forms of shamanic “power”, which evolve across the fringes of Tuva’s territory. Central to this ethnography is an assemblage of shamanic talismans, which embody ritual memory among coercively secularized post-communist societies (cf. Kwon 2000: 36). Focusing on a healing rite, which the Headman practised to block an assassin’s assault with “kargysh” curses against a helpless client, the materials will highlight symbolic paths opened by these shamanic devices as part of the remedial ceremony of kamlaniye. “Kamlaniye”, a Russian word signifying Siberian rituals conducted by either shamanic specialists or native lay persons (see Vitebsky 2001), is synonymous with the great animistic religions of the Altaians and other South Siberian (Tuva, Soyot, Karagas) horse-breeding “tribal” (clan-based) ethnic units, whose sacrificial rites and veneration of a “sky god” Eliade (1964) famously defined as a pristine residue of an “archaic” North Asian shamanism (DiÓszegi 1974, cited in Hoppál 1998). The presence of a religious specialist, known in Russian ethnography as shamán (Altai “kam”; Tuva “ham kizhi”) is ubiquitous in these regional cultures (Znamenski 2004), which include folkloric traditions of various ritual genres and chants (algyshtar, Tuvan; algysh, singular) for pleading with “spirits” (eeler, Tuvan) or even uttering curses at enemies and rival shamans (Kenin-Lopsan 1995a, 1995b). All these “concepts of power” govern the vocation and healing specialisms of the “Headman”, a revivalist Tuvan shaman, whose story of election and initiation begins with an interesting set of events that evolve from the classical motif of a “bestowal” of power by the neophyte’s ancestors. In the Headman’s narrative, this motif (which features in shamanic legends from Arctic Siberia to Mongolia) appears as a box containing a “hidden treasure” (namely, talismans and a female effigy), which he received from his shaman-grandmother amidst the politically dangerous climate of Soviet Tuva (in the 1950s).

As we shall see, this effigy, which incorporates the rebellious identity of a long dead shaman ancestor, functions as a catalyst of healing and retaliation during the Headman’s countercursing rituals. Bragging about his grandmother’s fearlessness, the Headman used to narrate his reminiscences of acting as an assistant of this ancestor and attending overnight kamlaniye rituals, during which this shamaness performed divination in a state of exaltation from chanting and blessings. These abilities caught the Party Commissars unawares and compromised their campaigns for “conquering superstitious false consciousness” through material progress (Balzer 1999: 21). The return of repressed shamanic spirits currently is reminiscent of heroic tales and myths about the shamanic amulets of the Orochon (Sakhalin, Eastern Siberia), which became furious after falling in the hands of Russians who installed them in a museum (Kwon 2000). Symbolizing experiences of totalitarian terror, stories about disowned and angered amulets, which take revenge on their former owners and command illness, reveal meanings of ritual memory as a form of resistance (2000: 34). As Kwon argues, re-approaching the trauma of Stalinist repressions through stories about shamanic objects is a way to acknowledge a living “absence”; namely, an absent agency involving the repressed and “unperformed rituals” of the past (ibid. 2000: 35-36; see also Højer 2009).

The ethnographic data on magical parasitism (or “soul vampirism”) and shamanic restorative practices are organized under three conceptual pillars, which underpin the structure of this essay. Emerging from a field of shadowy or illegitimate cultic practices, the data of the first part introduce a central theme of this analysis. Namely, the extension of “shamanic” rituals for cursing one’s antagonists (or avenging their misdeeds) into contexts associated with political intrigue. The present inclusion of this murky field of ritual practices into the shamans’ repertoire of remedial rituals is an analytical construct. The shamans who relayed rumours about professional magicians hired by political officeholders to dispense with their hard-working and committed assistants after an electoral campaign or to disable other candidates, sharply distinguish this type of occult malignancy from rituals for providing remedies to individuals struck with misfortunes. Crucially for the purposes of advancing a theory of “shamanism”, activities of ritual parasitism, which involve magical assaults, form a horizontal “curse-scape”. This spatial ontological realm expands like an anarchical religious cult, which is fuelled with riotous “energy sources” from graveyards and other infested areas.

Contrary to these disorderly schemes, developed by infamous cult-practitioners, the data related to the second conceptual pillar reveal how shamanic healing works through transferring clients from a “curse-scape” to a genealogy of ancestral souls and nature spirits. In this process, an explicit reference is made to the bear as a shamanic ancestor, whose presence symbolizes features of shamanic reciprocity (in opposition to the “parasitical activities” of magical offenders). This dichotomy underpins the third conceptual pillar of the present analysis. Based on a testimony of acts of sorcery, which allegedly took place in a public bureau and a graveyard, this exploration will establish a link between a client’s misfortunes and a long-standing agency of hauntings by spirits returning from the exile. The data will identify a distinct Buddhist religious modality of healing landscapes, which have become the sources of an extractive spiritual industry developed by Russian government elites and shamanic conspirators.

2. Research Results: Shamans, Ghostly Predation, and the Worship of Magical Parasitism

This article’s documentation of an upsurge of “curse paranoia”, which is governed by shamans, draws on primary data collected by this author during fieldwork in Kyzyl and other towns of Tuva in the year 2003. Common to these case materials (some of which are introduced below) is an understanding of curse afflictions as repercussions of disputes and conflicts, which are actionable by the justice system, as this author has shown elsewhere (2021, 2020, 2015). The condensation of curse accusations and ensuing hostilities within contexts associated with new political solutions involving indigenous spirituality (cf. Vitebsky and Alekseyev 2021: 114) is crucial for analysing the shamanic redressive techniques documented below. As it will be argued, practices of healing and countercursing are key features of a shamanic operation, which expands like a “border-crossing” phenomenon. A central finding of this study involves the interconnectedness of strands of socio-political ordering developed by shamans and political actors respectively. According to the evidence presented in the process, shamans develop novel contexts of political specialization with synergies across the state’s institutions.

Of special relevance for analysing contexts of hybrid political action is the following vignette, which offers a preamble to the main case study of this section. One of the most prized and rewarding moments of ethnographic inquiry concerned a special category of shamanic rituals reversing curses, which were enshrouded under a veil of secrecy. Infiltrating the public system of transparency and institutional democratization in the post-socialist political milieu of Kyzyl, shamanic rituals reserved by mid-level bureaucrats and high-profile clients (such as government officials) exhibited the dark (shamanic) undercurrents of political development in this Siberian city. Being a vital part of an expansive trend that resonates with Obeyesekere’s groundbreaking ethnography of demonic Hindu deities rising from Sri Lanka’s pantheon and of sorcery-cutting rituals, which proliferate in the drab slums of South Asia (1981, 1977, 1975), the Headman’s vindictive rituals recapitulated through cultic relics a heroic or redemptive path trodden by shamanic ancestors and rebellious spirits several decades ago.

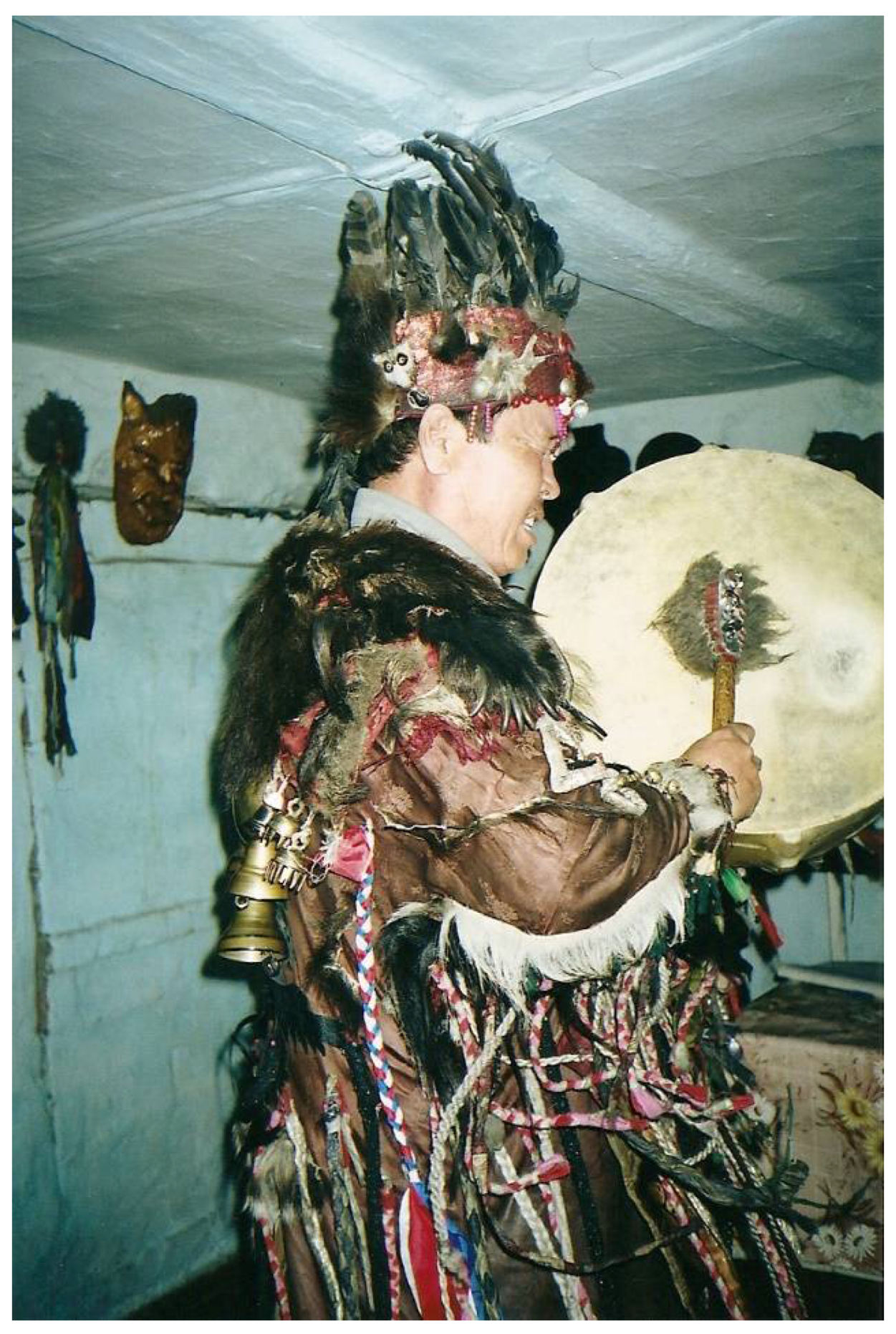

As we shall see, this personal imaginary of the “return of the repressed”, namely, a ritual modality of attributing ideology and revolutionary intentions to the “primal” ceremonial masks and symbols, is focused on the “dark powers” of the Headman’s shamanic ancestor. The latter, a Tuvan shamaness, was known as a figure of resistance and a political agitator, whose angered soul went into a flight after she was summarily executed by the Soviets in the mid-1950s. According to this account, which the Headman represented as an old regional legend about this ancestor’s feats, the fame of this “black shamaness” (

kara ham, Tuvan) originated from her miraculous healing rituals and prophecies, which the Soviets strived to suppress. In a way reminiscent of millenarian mobilizations and various “prophetic disturbances”, which surged in Africa during the halcyon days of anti-colonial popular resistance (see Morris 2004: 159 ff.), the shamaness

Kara-kys1 roamed throughout the Tuvan steppes, propagating a religious craft akin to a “cult of affliction”. The spirit, which was fuelled into this cultic association founded by Kara-kys in a rural locality known as

Kara Bulung (“The Black Corner”, Tuvan), permeated the life of Kara-kys’ brother, whose name was

Cherlik ham (“The Mad Shaman”, Tuvan). Acknowledging mutual genealogical roots of affliction with

Albys, a mysterious, shape-shifting spirit (whose form as a “hostess of the taiga” you may encounter while walking through the wilderness at dawn), the inspired siblings practised kamlaniye rituals to release ethnic Tuvans and Russians from sickness and suffering at the height of Soviet anti-religious campaigns. Symbolically overshadowing the post-Soviet political establishment of Tuva, this ancestor (Kara-kys

) lives within an effigy, which the Headman had placed over his desk and chair at his shamanic Association (

Figure 1).

The political implications of the resurgence of dark spirits behind shamanic revival in Kyzyl emerge in the following account relayed by the Headman. The latter, a specialist in casting out curses and similar forms of “negative (bad) energy” (plokhaya energiya, Russian) from patients, would often comment that a great deal of his special techniques was concerned with knowledge and “advice” (soviet, Russian) he himself offered to local political personnel at a fee. Characteristically, once, the Headman dissuaded this author from contacting the office of an elected member of the Tuvan Parliament (at whose request the Headman had practised a ritual for bolstering his political campaign), stressing that the opposite action would be tantamount to a definitive end of the author’s ethnographic career in Tuva! This author took seriously his shamanic mentor’s advice to avoid establishing contacts fraught with danger, particularly after he had several bitter experiences of dealing with bureaucratic procedures of registration required of foreign visitors to Kyzyl. Nonetheless, this author was compensated with rare testimonies about secret consortiums between political actors (or their teams) and the Headman. Moreover, in one instance, the author witnessed a shaman’s divination, which dealt with a life-threatening situation concerning a close kin of a high-level Russian state administrator (who was the main client present at this consultation). Although they constituted secondary sources, primary field data of this kind added further insights into the political impact of modern shamanic retaliatory action, leading thereby to the refining of the major propositions explored in this article.

Evidence concerning the centrality of notions of political domination regulated by shamans (some of whom are associated with disreputable ritual practices) emerges from the following account, which circulated among this author’s informants. This story involved strange rumours about a ritual, during which an obscure magician died of the same curses he launched against his client’s enemies. These rumours focused on the shady dealings and inevitable death of an aficionado of “black magic” (chiornaya magiya, Russian). This person had not been ordained in any shamanic “school” of Kyzyl. Nonetheless, his identity as an extra-sensory healer (extra-sens, Russian) was well-known among many shamans. According to these rumours, the culprit (who fell victim to his own sorcery) was a socially marginal figure, who propagated an egregious cult in the fringes of shamanism’s institutional settings. He was known as offering magical services in an unacknowledged (grey) zone lying beyond the domain of shamans licensed by their organizations to perform cures. He was rumoured to practise costly rituals for politicians and affluent citizens, as well as to charge exorbitant fees for providing his services to desperate clients struck with misfortunes related to health and family. His notoriety stemmed from his methods of sickening his victims with “evil spells” (zaklinaniya, Russian) and demanding ransom to release their own or their relatives’ souls (which he had abducted). In a way which replicated pyramid schemes or protection rackets on a metaphysical level, the magician operated an inscrutable criminal business of harvesting souls from alive victims and alienating deceased persons from the scattered remnants of their souls, which linger in graveyards.

As this rumour unfolds, one night, the infamous magician was dabbling in a ritual for a client seeking to empower himself through a vampirical extraction of a victim’s soul. Nonetheless, things took an unexpected turn. It did not become possible to verify the medical diagnosis of the cause of his death. Nonetheless, the shamans, who imparted this information to this author, attributed this outcome to a combination of occult and material causes. In their view, the magician’s death resulted from a cumulative process, which involved the appropriation of large quantities of “bad energy” delivered from the spirit world. During his career, the magician was allegedly being supplied with these resources by noxious spirits, which inhabit in graveyards and desolate places. As the managers of a repository of dead peoples’ souls, these spirits (known as chetker and mangys) had granted the “soulless” magician access to a grotesque gallery of disembodied “soul parts” that survive a person posthumously. Thanks to his intimacy with these spirits, the magician was a licensed collector of “soul parts”, which had composed a person’s vitality in this world.

As a member in this “auction of souls” in the Tuvan “Underworld” (

Erlik Oran), this magician had amassed a collection of “soul parts”, such as a person’s “breath” (

tyn, Tuvan), which he devoured each time he conducted his deadly cursing rituals. In this way, the magician sponsored his professional activities and channelled his occult acquisitions into his rituals. Accordingly, his death was explained as a result of running out of “energy” supplies at a critical moment whilst practising a ritual of exalting these demons’ magnanimity as providers of souls, who made his anthropophagic feasts possible. While promoting this explanation, the shamans designated locations, which are rich in resources such as the “dark powers” (

karaŋ kiushter, Tuvan)

2 appropriated by ill-intentioned magicians. Moreover, they noted that these dark powers are condensed in graveyards, where they can be extracted by shamanic vampires – like the main character of this story – hovering around burials and preying on the residual energy of deceased persons.

Importantly, religious beliefs in occult and demonic agencies as causes of illness and death are widely documented in the indigenous folklore about non-human demonic beings across the Inner Asian and Tibetan areas, as well as in the Himalayas. In his excellent ethnography of Nepal’s evocative religious landscapes, which are home to the Hyolmo people and their spirits, Davide Torri observes that in Helambu Valley “human and non-human communities are entangled in a cosmopolitical process of reciprocity, mutuality and conflictual relationships” (2022: 68 ff.). Hyolmo experiences of fright due to being stalked by demonic non-humans and headless ghosts in liminal social spaces, such as water mills, exemplify a cultural logic of predation and loss of a human’s life-energy after encounters with spirits (ibid. 2022: 69). Originating from the Gelukpa clerical tradition of Tibetan Buddhism (Markus 2006: 295; also Samuel 1993), Lamaism has long been intertwined with the shamanic spirit complex of Tuva. In his overview of Tuvan Lamaism at the turn of the twentieth century, Sergei Markus, a Russian scholar of Tuva, mentions that shamans and lamas co-existed and performed rituals in local monasteries (known as

khuree). This form of syncretism encompassed lay peoples’ practices of worshipping figures of Buddhist deities (

burkhan, Tuvan), which were placed alongside shamanic cultic objects on the altar (

shiree) inside the yurt (2006: 296).

3 The shamanic notion of affliction with occult agencies is also present in Tuvinian (Tuvan) folkloric images of Tibetan demons associated with symptoms of illnesses (e.g. epilepsy, oblivion, or emaciation), which were dealt with in healing rituals (Schwieger 2009).

Besides these anthropomorphic demons, Tuvan cosmology contains various spiritually degraded quasi-shamanic beings, which live impoverished or dysfunctional lives as a result of karmic retribution for their immoral conduct. For instance, the Headman referred to one of his shamanic rivals, deriding this practitioner’s penchant for shifting into a goblin or a dwarf and spying on his algysh chanting at the Association (a precious and enviable intellectual resource, akin to native epic stories describing past feats, which is also subject to illegitimate extraction, like gold and uranium). The perceived multiplicity of shamanic-like doppelgangers, who appear as parasitical ghosts, resonates with Alexander King’s description of a non-social ethos replete with unsettling images of shamanic spirituality among the Koryak of northern Kamchatka (1999). As he notes, human vampires were omnipresent in this gloomy post-socialist setting of Northeastern Russia, where daily stealing or siphoning off once-public assets and meagre state budgets have their equivalent in the misdeeds of the blood-sucking undead. As a refraction of general moral decline, ageless shamanic vampires are feared for their ability to feed on the souls of both dead and living Koryaks. These vampires are attributed with superhuman skills of sapping peoples’ “life-souls”. In this way, they act similarly to local Koryak anthropophagic spirits, which destroy the dead persons’ journey to the afterlife and forestall their reincarnation (King 1999; see also Vallikivi and Sidorova 2017, on reincarnation accounts among the Yukaghir of Northeast Siberia).

Likewise, the magician’s impulse for draining the souls of the dead and channelling them into a market of “soul parts” was condemned as an an unethical form of shamanizing. Yet, the shamans who commented on this malpractice, identified one more cause, which contributed to a synergy of spiritual and material sources of degradation. The latter cause involved this magician’s costume and decorative symbols, which functioned as a magnet of occult agencies, sickening thus its owner. The magician’s death after handling the hazardous occult agencies disclosed his risky repudiation of the ethics of reciprocal exchanges inherent in shamanic sociality. As these shamans recalled, the victim owned a fearsome and uncanny ritual gown, which he wore each time he was dabbling in rituals saturated with curses and “black language” (kara-dyl). Symbolizing its owner’s person as a sinister cult leader, this gown was made exclusively of black fabric, which the odd soul-snatcher had adorned with numerous pendants as the products of his own craftsmanship. Resembling late Medieval denunciations of the “magus” and his “idolatrous cults inspired by the devil” (Ginzburg 1990: 137), the magical robe and its weird emblems functioned as an appalling theatre of spectres feeding on deceased souls captured in graveyards. Moreover, drawing on testimonies from shamans who witnessed this devotee’s rituals, this urban legend had it that the bizarre cloak had become the abode of noxious incorporeal beings (mangys, shulbus) and similar “devils”, which one day devoured their master’s soul. Thus, the magus and his “theater of the offensive” (cf. Ginzburg 1990: 137) exemplify a religious iconoclasm, which stands in contrast to the shamans’ morality cults (cf. Lewis 1971), including curse removals, which are performed for healing.

3. The Pendulum of Cursing and Healing: Parsing Curse-Scapes with Shamanic Symbols

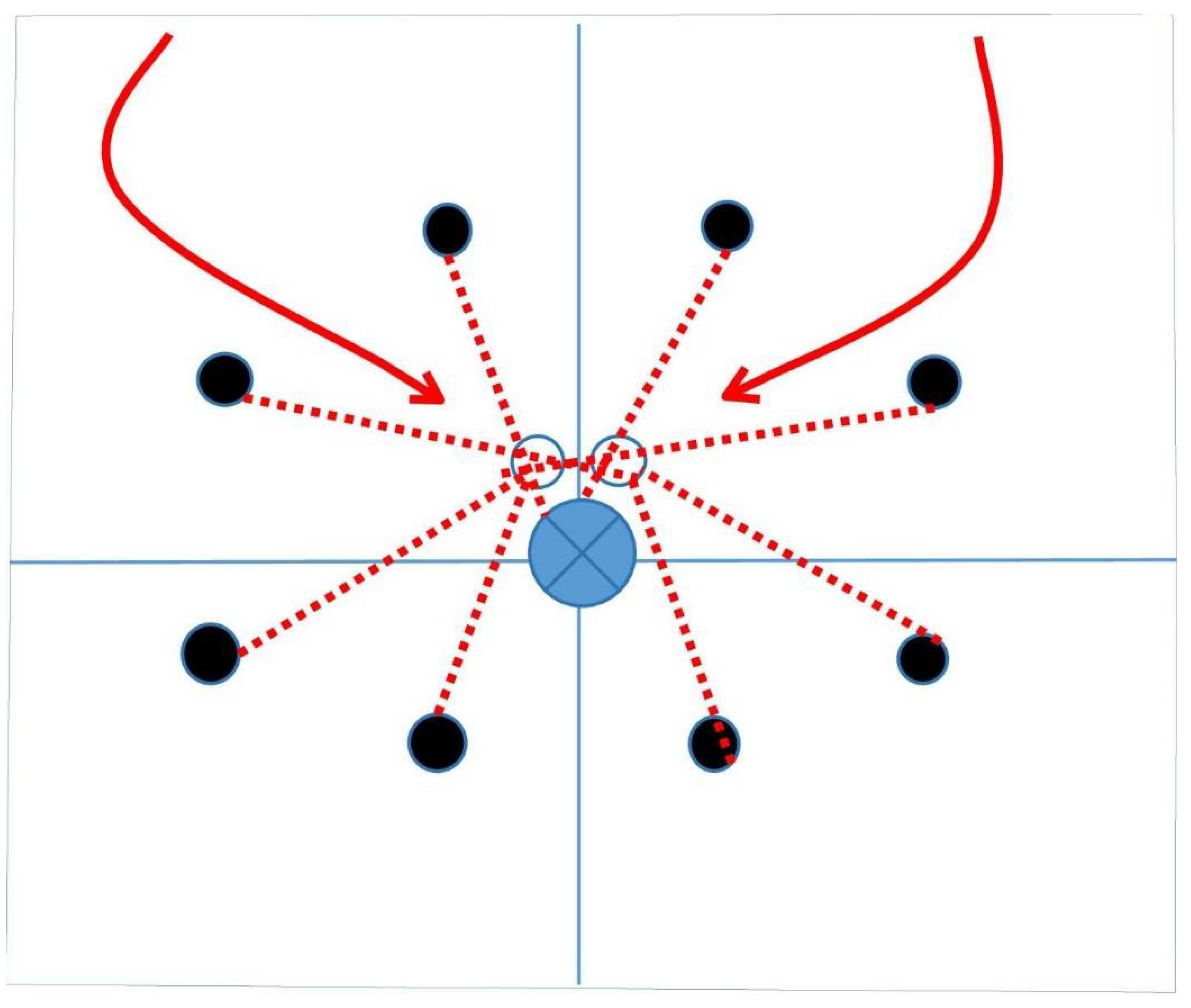

In highlighting a hybrid, religious and political, sphere, which evolves around rumours and practices of worshipping magical parasitism, the magician’s story reveals an occult economy of shamanic offenders, doppelgangers, and dangerous relics. This occult operation involves practices of seizing the souls of the dead and the living in order to install them in foreign bodies and benefit their possessors. The following shamanic diagnosis of magical assault involving the extraction of the victim’s soul further attests to this operative logic. In this case, which the author was able to document in the course of several days, the Headman removed curses from a woman who had gone to court to contest her ex-husband’s legal claims on the ownership of a house where she was living after they divorced. Additionally, this client reported that she had been struck with grave misfortunes, which the Headman attributed to curses by various magicians whom her ex-husband had enlisted. Evidence of the latter enemy’s abusive magical activities, with which the aggrieved client agreed, was procured through an unfailing divinatory method of detecting the trajectories of the curses that had criss-crossed this client and her family members from multiple ankles (see Sketch 1). This pattern was presented to the client as a “panoramic” portrait of innumerable lineaments of cursing, which emerged as the Headman took his forty-one tiny divinatory stones and randomly dispersed them on a purple mat laid on his desk. The Headman pointed to the central axis of this complex pattern, where two white stones, standing as symbols of the client’s and her family’s purity and innocence, were encircled by a multitude of black stones as the traces of recurrent murder attempt planned by her ex-husband and perpetrated by hired vampiric killers.

Scheme 1.

Author’s reconstruction of divinatory map showing a stream of curses that struck the client and her relative, killing the latter. The diagram lays out in a schematic fashion the pattern of multilateral curse affliction, as it emerged from the Headman’s divination. The invasion of curses is featured by the two curved red arrows, which represent the reflexive or spiralling motion of ballistic supernatural weapons deployed by either murderous sorcerers or specialists in intercepting curses (namely, weapons similar to “surface-to-air” missiles, in the Headman’s words; “земля-вoздух”, in Russian). The red dotted lines, which extend from each of the black circles, show the path of curses cutting across the victims (the latter ones are symbolized by two white circles right above the central axis of the diagram).

Scheme 1.

Author’s reconstruction of divinatory map showing a stream of curses that struck the client and her relative, killing the latter. The diagram lays out in a schematic fashion the pattern of multilateral curse affliction, as it emerged from the Headman’s divination. The invasion of curses is featured by the two curved red arrows, which represent the reflexive or spiralling motion of ballistic supernatural weapons deployed by either murderous sorcerers or specialists in intercepting curses (namely, weapons similar to “surface-to-air” missiles, in the Headman’s words; “земля-вoздух”, in Russian). The red dotted lines, which extend from each of the black circles, show the path of curses cutting across the victims (the latter ones are symbolized by two white circles right above the central axis of the diagram).

This circular pattern offered evidence of the workings of an extremely serious “kargysh curse”, which had caused these misfortunes – namely, the sudden death of a beloved relative of this client, followed by health problems this client was suffering from. As the client was trying to read this map of linear cursing, which the Headman’s pathfinding (and fact-finding) divinatory technique produced, she was alarmed to the implications of this divination (evidently, a risky and exaggerated divination) of the occult threats surrounding her. On his part, the Headman further explained that the enemy had mobilized a magical offensive as a drastic means for fulfilling his purpose: the sooner the victim dies of black magic, the more likely the offender will become the sole proprietor of the house he coveted. The client expressed feelings of agony about the detrimental effects of the enemy’s unabated offensive. She requested the Headman to deflect the curses on the spot. Further on, thinking about her home’s security, she arranged for a ritual of cleansing curses at her house. In this sense, the Headman’s divination of curses paved the way for mutual dissociation and hostility for the enemy in a process of constructing his performative efficacy. The Headman’s imaginative construction of ritual efficacy involved a plan of manipulation based on cultivating risk and “curse anxiety” in a process of rectifying this pathological state with a shamanic repertoire of symbols.

The proceedings of this ritual purification included standard techniques of cleansing the client’s ailing body with juniper incense. During this process, the client was asked to stand upright and hold a key symbol of spiritual cleanliness; a metallic bowl, which the Headman had filled with milk. Attempting to stimulate the client’s experiential responses to the invisible workings of his healing energy, the Headman described his technique as a “twofold” remedy, which, in his own words, repelled the “extended arrows” of the curses. The first fold of this healing epistemology involved the aforementioned procedure of “cleansing with juniper incense” (artysh bile aryglaar, Tuvan), a herbal medicament whose cathartic and palliative effects the Headman regarded as indispensable for efficacious healing (Anonymous 2013). The second fold developed this healing imagery through acts, which symbolized a cosmological partition between nature’s “spirited landscape” and an infectious “curse-scape”. The latter is a grim social world full of aggression and virulent cursing within which the citizens of Kyzyl and other Russian cities were interlinked as causal agents and victims.

During this phase of the healing process, the Headman tied a blue and a red thread to the client’s left and right wrists respectively. The client was sitting on the bench with her palms stretched in a gesture signifying an act of supplication (as though she received a boon from the spirit world). At that moment, the Headman tied the edges of the two threads to a sacred “bundle” of countless threads and patches embodying a legendary and feared shamanic ancestor, namely, his shaman grandmother, Kara-kys (

Figure 2). Symbolizing a bygone epoch of rebellious spirits and political trance-rituals by shamans in Soviet Tuva, this cultic item was displayed with great pride by the Headman – whose narrative of salvaging a box enclosing this relic among other receptacles of his ancestors’ shamanic spirits parallels accounts of the indefatigable spirit of Russian and Siberian ethnographers, who were sent to labour camps or were executed in the 1930s, as well as the spirit of the “surviving bruised and battered” ethnographers, who outlived the Stalinist purges and the German siege of Leningrad (see Vitebsky and Alekseyev 2015: 443 ff.; also Takakura 2006). As a symbol of shamanic ancestry, this effigy contains a meaning of “primalness” characteristic of artefacts in Soviet museums, which displayed the life ways of the “self-provisioning” Siberian nationalities and their primal religious systems (see Anderson and Arzyutov 2016: 197; also, Anisimov 1958).

Next, the Headman’s evocation of spirit-helpers, which animate talismans indispensable for manning an ancestor cult, triggered images of native Siberians perambulating sacred sites and searching for clues of their genealogy or visiting ethnic museums at the end of Russia’s Siberian frontiers. Resembling discussions between anthropologists and museum curators about the carved votive figures of the Nanai people in the Russian Far East (Bloch and Kendall 2004: 108-109), the healing ritual shifted into an exposition of the Headman’s artefacts and ceremonial masks. Pointing to a copper made arrow, which had a pair of colourful “ribbons” (chalama, Tuvan) tied to its edge, the Headman noted the abilities of the spirit inhabiting this “arrow” (ydyk-ok, Tuvan). Once the arrow spirit is awakened by the Headman’s drumming and chanting (see below), it functions as a projectile, whose velocity is reminiscent of the old shamans’ intercepting – through soul flight and clairvoyance – the movement of the prey in the permafrost (Vitebsky and Alekseyev 2020: 31-32). The performance of kamlaniye reconfigures the perception of landscapes through “altered states” of pace and velocity, which extend across the space between nature’s spirits and the “curse-scape” in Kyzyl. In this sense, the shaman’s imaginary of a hunting tool, which traverses the sky and strikes the soul of a human target, displays features akin to the velocities of aviation and telecommunications, which, as Vitebsky and Alekseyev observe for the Eveny people of Northeast Siberia, are modern enhancements of the shaman’s soul-flight (2020: 45).

This continuity between kinds of movement associated with hunters, animals, and shamans extends into another symbol, which stands in the centre of the Headman’s “museum of spirits”. Described by the Headman as the “bear spirit” (

adyg eeren, Tuvan), this tutelary spirit resides in the body of an embalmed brown bear, which overlooks the assemblage of talismans and shamanic attires hanging on the walls of the Headman’s inner court room (

Figure 3). In a way that evokes his predecessors’ cults of appeasing the soul of a bear slain by hunters, the Headman honoured the eeren spirit of his “bear” (

medved’, Russian) with offerings of chunks of boiled meat from sheep (which were consumed afterwards by the shamans and the ethnographer participating in this domestic ritual in the Associations’ premises). After each of these communal meals, ritual action would be resumed, this time as a collective kamlaniye ritual by the shamans in the courtyard, where the spirits of “heaven” (

tengger, Tuvan) were propitiated with algysh chants. In performing this ritual, the shamans possibly legitimized and updated a tribal cosmology of hunting rituals addressing the bear as a spirit-overlord.

This discussion indicates the resilience of a pattern of hunter-prey interchange, which, as Willerslev argues, permeates the cosmology of hunting communities in Arctic Siberia (2007). In his discussion of the elementary forms of Yukaghir shamanism in Upper Kolyma, Sakha Republic, Willerslev observes that shamans and hunters differ from each other in terms of kinds of ritual specialization in attracting or coercing animals to offer themselves as prey. Yukaghir hunters risk incurring the wrath of the animal, which avenges the violence of human predators. Hunters in this circumpolar region cope with ontological insecurity through applying shamanic tactics of interchangeability involving objects or other persons as substitutes. Characteristically, they blame the killing of a bear on Russians or Sakha people and, thereby, avoid being “preyed upon” by the offended soul of the animal they themselves killed (2007: 128 ff.). The present data indicate a similar pattern of making a ritual reparation to the bear spirit, which, as mentioned, holds a superior place among the Headman’s tutelary spirits (perhaps being second only to the bundle-effigy, which is incarnated by his shaman ancestor). Namely, the collective ritual following a meal, where large quantities of mutton are consumed by shamans honouring their bear-spirit, may serve the purpose of avoiding a dangerous identification with the bear-ancestor in a sacred symposium, where its human relatives feast on this ancestor by means of consuming a symbolic substitute.

In re-enacting the bear-ancestor’s perspective, the participants in this ancestor-cult anticipate the consequences of their cannibalistic acts through a ritual of atonement as a symbolic remove (cf. Obeyesekere 1990) from a primordial stratum overlain with features of “animality”. From this perspective, performing shamanic rituals with a gown on which pieces of a bear’s hide are sewn (as in the Headman’s coat) epitomizes basic precepts of humanity – in opposition to the unrecognizable features of the dead magician’s gown as a devouring instrument (considered earlier). This contrast takes on a special meaning in light of Ingold’s argument that humans are “constitutionally divided” beings, since they subscribe to moral restraints and innate (biological) conditions respectively. According to Ingold, a key feature of modern Western rationalism involves a dichotomy between a capacity for sociality characteristic of humans and a more generic condition of animality. As a raw state of being, animality is present in human life forms, which are thought of as having stripped themselves of essential attributes, such as moral or customary regulations (1994: 21).

There is evidence to support this indigenous perception of the Headman’s bear feast as a symbolic boundary between human sociality and anthropophagy (a boundary which the dark magician fatally trespassed as a result of performing with his “self-devouring gown”). As Victoria Soyan Peemot shows in her studies of horse husbandry in Ak-Erik Khem, a region in South Tyva (Tuva), equines are distinguished from other domesticated animals that comprise each herder’s socio-economic unit (known as aal). In a way that resembles notions of the bear as a special guest, Ak-Erik herders regard their horses as more-than-human persons whose distinct lineages evolve parallel to their human owners’ lineages (2024). In the “sentient landscapes” of the boreal forests of Tangdy-Uula Mountains of South Tyva, equines hold a special status as “livestock of the land” (or wilderness) and as mediators between humans and the spirit-master (eezi) of these places (Soyan Peemot 2019: 56 ff.).

“Natural Symbols” and the Performance of Shamanic Healing

The above account of a synergy of healing symbols evolving from the Headman’s (expertly calculated) alarming divination of occult violence leads to an important implication about therapeutic efficacy. According to this, the healing process takes the form of parsing an extended shamanic topography into a pair of opposite moral systems, which are symbolized by a horizontal and a vertical axis respectively (cf. Delaplace 2020). These conceptual pillars uphold a metaphysical geography, which divides the world into a horizontal spatial context infested with curses; and, on the other hand, a vertical genealogy of shamanic spirits, which reside in the Headman’s ritual instruments. The shamanic “journey” and quest for a remedy are contingent on effectively invoking the sacred genealogy of shamanic spectres. The latter engagement with a vertical line of shamanic ancestors and spirits – an arduous and unknowable path, as it will emerge below – symbolizes the client’s redemption from a plague of curses roaming in the crime-ridden capital city of Kyzyl. This imagery of shamanic healing as a pendulum swinging between a (spatial) curse-scape and a field of “natural healing symbols” is manifested in the final part of the Headman’s ritual for the cursed client. Soon after the client was linked to the Headman’s effigy through a pair of red and blue threads (as described above), the Headman cut each of these threads with a scissors. This “cutting rite” signalled the outflow of curses to the effigy-bundle (which functions as a collector of curses from hundreds of clients treated by the Headman).

The final part of this healing involved the Headman’s kamlaniye ritual as a means for transitioning to a vertical cosmology of spirits and ancestors, who function as arbiters of justice and redress wrongs. During this performance, the burnt juniper incense emitted a soothing vapour that filled the inner courtroom. Along with the bowl filled with ritually blessed milk, which the client was given to hold in the onset of this ritual, the juniper incense materialized the

“natural elements” sweeping the curses away. These “natural symbols” set the ground for establishing a polarity between pure landscapes and a (ritually) unclean “energy field” that radiates throughout Kyzyl (like a “cross-cutting curse” lying in ambush at a road junction). This contrast and its symbolization involved illocutionary acts of calling upon the “spirits of the taiga” (tandy synnar eeleri) and the “spirits of rivers and waters” (khemner suglar eeleri). While chanting his algysh to these spirits and summoning them to defend the client, the Headman unleashed an impressive crescendo of drum beats, which intensified the tempo of his performance. The final part of this performance involved a “demonstration of competence” by the master of kamlaniye. As the sound of his drum vibrated throughout the interior spaces, the Headman kept rolling around himself in a way imitating the “whirlwind” (kazyrgy) and dispersing the curses. The spirits had been informed of the client’s request for justice and health, which the shaman conveyed through indignant pleas for attention to the woman’s tragic circumstances during his algysh chanting.

Looking as though he had just recovered his senses after a laborious effort to grapple with the spirits and persuade them, the Headman took off his shamanic coat and sat behind his desk. He announced that the spirits revealed to him the chronicle of the enemy’s mobilizing magicians to curse the client. As this sequence of deadly metaphysical events was unfolding before his eyes whilst performing kamlaniye, he “saw” the client’s ex-husband launch a curse assault against the client’s relative. In elaborating on his divination of magicians being hired to kill, the Headman enhanced the efficacy of his performance by means of jeopardizing his ritual status during a consultation with uncertain outcomes. This unusual device of performative efficacy involved a risky divination, which unravelled the events of the client’s relative’s death from the perspective of a vampire. The vampire’s perspective involved the presence of a kin-based homology between the victim and himself. The Headman asserted that the enemy, by virtue of his rapport with magicians in a Russian town of Krasnoyarsk Region (located north of Tuva Republic), had developed a propensity for feasting parasitically on his relatives’ vitality. As he added, the ageing enemy-vampire extracted the soul of his young relative with support from his conspirators. The perpetrator inserted the soul in his own body in order to acquire the victim’s sexual potency and use this “energy” to the satisfaction of a woman much younger than him, with whom he was carrying on. Thus, being compelled by a cannibalistic impulse, the enemy had devoured the soul of his young relative.

Remarkably, this exaggerated (and, potentially, insensitive or explosive) divination, involving shamanic visions of soul extraction, intensified the client’s resentment and vengefulness (rather than provoking anxiety or even fatalistic thoughts). The shaman’s articulation of a magical plot as a ramification of animosities between ex-spouses suggests that risk and imagination are inextricably linked to power and ritual efficacy. Efficacy in the context of performing a “cure” (emneer, Tuvan) involves an intuitive skill for pulling strands of paranoia from a client’s narrative, as the Headman’s following explanation reveals: “Each time I divine for a client, I do not look at the stones in front of me; I look into the client’s eyes (even as the latter is gazing at the stones) and I see the events of cursing, as they are reflected on the client’s eyes”. This vignette shows that the cultivation of risk and occult danger as “powerful strategic resources” sets in motion an enchanted ontological realm, which harmonizes socio-political contexts rife with tensions – a point which Kari Telle has developed in her discussion of Hindu Balinese rituals in Lombok (2016: 427). The materials following will set the stage for an unforeseen permutation of shamanic rituals into an arena of re-enchanted tools and techniques of reshaping a world of incommensurate value systems, namely, a “curse-scape” and a natural landscape of healing spirits.

4. Case Materials from a Shaman’s Inner Courtroom: The Propagation of Healing and Supernatural Justice

Viewed in light of an indigenous cosmology, which traverses landscapes across Tuva and Mongolia, cases of magical parasitism, ritual offences by living parasites, and vindictive impulses of dead shamanic ancestors weave an unsettling new portrayal of classical (kin and ancestor based) shamanic religion. A striking picture of the socio-political field emerges, according to which the shamans’ rituals have turned into strange attractors for afflicted or repressed (ancestral and nature) spirits in search of a “sanctuary” or a refuge. These downtrodden spirits take on various (unpredictable) appearances through successive reincarnations even as they encounter past and present human communities, as the following sets of interlinked narratives reveal.

One of those few clients, whose narrative of suffering and healing uniquely contributed to the author’s understanding of a curse-scape in Kyzyl, shared her experiences of spirit-human encounters in the vicinity of a village where she lived until her adolescence. These ghostly stories were narrated as an extension of this informant’s extraordinary experiences of “darkness and light”, leading to her transformation and spiritual renewal effected by the Headman’s ritual of summoning the spirits of this client’s birthplace. A summary of this client’s chronicle of curse affliction and experiential responses to several episodes of occult violence, which were allegedly orchestrated by her antagonists, is necessary at this point. The main event, which led this client to interpret a spate of curse-inflicted misfortunes as a permutation of a long-lasting “agency” haunting her, was an unfulfilled romantic relationship in the village where she grew up. In early March, 2003, Arzhana, a single and childless woman (aged 32 at that time) came to the Association seeking a consultation in the Headman’s inner courtroom (where this author first met her). Prior to this treatment, this client had received a medical diagnosis of infertility and had been hospitalized in the intervals of long periods of suffering from an illness, which the doctors diagnosed as an “inflammation” (vospaleniye, Russian) in her uterus.

This problem, which the Headman diagnosed as a “chronic illness” (khoochuraan aaryg, Tuvan), formed the basis of successive curing sessions involving the physical and “psychological manipulation” of the ailing woman’s generative organs (cf. Levi-Strauss 1963). Accompanied by an assistant female shaman, who depicted her ecstatic visions of the curative bio-energy through flashing drawings on plain paper in front of her, the Headman established “evidence” of the calamitous impact of curses during his kamlaniye. Whilst the female shaman’s dream-like fugue had deepened and her eyes had rolled back (at a moment when she was holding a pen in her trembling hand), the Headman bombastically chanted and drummed. During these moments, he summoned supernatural retaliation by means of indignant invocations of his tutelary spirits. The target of this performance of revenge, whose effectiveness the Headman predetermined in a “political” oratory (involving self-praising speech), was this client’s enemy. The enemy – a Tuvan woman who supervised Arzhana at her workplace, a tax accounts bureau – was rumoured to engage in “shady affairs” at her office, aided by a mysterious witch of Armenian origin, whose “method” of bewitching involved burning banknotes of roubles and disposing of the ashes in graveyards, in order to feed the “dark” powers. Arzhana described this period of her life as a tax accountant in Ak Dovurak (a provincial town in the western part of Tuva) as a period full of misery caused by a regime of tyranny, which her superior had imposed.

Her testimony contains many facts suggestive of a plan of disguised acts of sorcery. Her supervisor deceptively used various objects as devices for canalizing hostile impulses. Once, this offender’s impulse for gratifying her death wishes for Arzhana took an almost unnoticeable appearance, since it involved actions of giving a sorcerous potion to her. In what looked like a strange synergy of encounters, the supervisor emerged from her office and approached Arzhana’s desk, leaving a cup of black tea right next to her (an offer that was made in an unusually “polite” and subdued tone). Arzhana was struck by this “courteous” offer and responded to her supervisor as follows: “You forgot your cup; please take it because my desk is full of papers”. Her supervisor attempted to justify this inexplicable gesture in a way that only intensified Arzhana’s suspicions. She relayed her supervisor’s response: “Arzhana, I have never brought you anything before”. Her fears of having been trapped into an incident of cursing took a concrete form as soon as she witnessed the following.

Shortly after Arzhana confronted her supervisor, the Armenian witch emerged from the supervisor’s office and walked past Arzhana’s desk, glancing at the latter with hatred. A solution to this “enigma” emerged a few minutes later, as the supervisor approached the employees of her bureau and, in a state of enthusiasm, announced to them that the Armenian witch had assured her that her “wishes” (pozhelaniya, Russian) would come true if she followed her advice. The supervisor relayed that she was asked to withdraw four thousand roubles from her own bank account. The Armenian witch kept a note of one hundred roubles in compensation for her services, instructing the supervisor to rush to the nearest graveyard, in order to burn the rest of the money (namely, three thousand nine hundred roubles to be turned into ashes). The Armenian required the supervisor to give a vow, warning her that the spirits will accept only this offer of money (as a sacrifice) at the site of the graveyard and that “everything would turn out very bad for her” if she reneged on her vow! During these moments, Arzhana was overwhelmed with ominous feelings leading her to dispel the curses contained in her supervisor’s tea pot. Instead of drinking tea from her supervisor’s cup, she emptied the tea on a flower pot, avoiding any contact with this poisonous gift.

In October 2002 (several months before her consultation at the Association), Arzhana resigned from her position, accusing her supervisor of contemptuous conduct, yet the worst was still to come. In the town of Ak Dovurak, where she spent two years working as an accountant, Arzhana had an affair with a man (a teacher by profession). One day in December 2002, this man revealed to her that he had an affair with another woman who was pregnant by him, and he asked for a breakup. Arzhana was adamant in her belief that her breakup and health-related problems resulted from her supervisor’s assault with “kargysh curses”.

5. Implications: Re-Enchanting Curse-Scapes

It will be argued that this chronicle of curse affliction supports the article’s interpretation of shamanic practices as a refuge for socially unacknowledged and politically repressed spectres. Seen within a wider context of events unfolding backwards, Arzhana’s misfortunes appear to be the latest chapter in a larger meta-historical narrative authored by avenging spirits and their politicized rituals. This link between recent misfortunes and “ancient” transgressions or faults associated with graveyards and scary shamanic locales in the countryside (see Humphrey 1999) emerges from several interlinked ethnographic vignettes. The first of them concerns a tragic event, which Arzhana disclosed in a way affirming a “miraculous” revelation by the Headman after performing a kamlaniye ritual to cleanse her from curses. During a “trance state”, which he described as a reverse flight over a line of events from Arzhana’s lifetime, the Headman’s vision caught several instances of an episode of cursing in the village of Khondergei (Dzun Khemchkikskii kozhuun, West Tuva), where Arzhana lived in her adolescence. Through an unprecedentedly opaque divination, the Headman articulated a series of blurred visions of how Arzhana had been cursed by other residents of this village. Remarkably, being motivated by the opacity of the Headman’s divination, Arzhana disclosed a tragic event, which marked the period of her life in this village.

According to her narrative, while she was living in Khondergei, Arzhana had a relationship, which, however, was meant to be short-lived. Her partner, who was a young Tuvan man, wanted to marry her, but Arzhana was reluctant to proceed to marriage. Nonetheless, this period of happiness was terminated one day, when Arzhana’s partner died after he accidentally grasped a faulty electrical cable. Following his death, Arzhana had an encounter with his mother, who believed that her son would be alive if she had married him. Arzhana reflected on this loss in a way that displaces human accountability for misfortune to a predetermined supernatural pattern, which resembles the Buryats’ narratives of reincarnation analysed by Humphrey (2004). Arzhana recalled that her partner’s death was the last in a succession of deadly accidents that had taken place several years earlier in the vicinity of her village. She mentioned that the residents of this village brought a lama, who conducted a cleansing rite in order to “cut” a line of contagiousness, which was flowing into the unprotected space, as this Buddhist priest explained the purpose of this ritual. The priest drew a connection between the incidents of unnatural death among young people and an unsettling phenomenon; namely, an epidemic of hauntings by frightening spirits and the wandering souls of deceased people in the same village.

Several months before these deaths started to occur, the community of Khondergei suffered from a “plague” of spirits roaming in the village’s space and its outlying areas. People would wake up terrified in the dead of night and would see a silent figure of a deceased kin emerging through the darkness. Other people would be found paralysed or unconscious after encountering an albys; namely, an uncanny spirit, which assumes deceptive anthropomorphic appearances and raises its dark long hair to reveal a countenance terrifying to its beholder, who falls into shamanic fits of “insanity” (albystai bergen, Tuvan). The deeper cause behind this silent revolution of ghosts was the paucity of rituals, which had kept the intruding “dark forces” at bay in the past. Arzhana recalled the lama’s parting words to the participants of this ritual, which he performed to sever the link between the possessing (or afflicting) spirits and this community’s members: “For a long time, there were no rituals in this region, and the “dark forces” (karaŋ kiushter) have dispersed throughout the landscape”. The priest closed his address to the residents in a pessimistic tone. The propitiatory ceremony, which he conducted, could only provide temporary solace to the disgruntled and unacknowledged dead kin and wild spirits, for the latter task would require a herculean mental effort by a group of lamas and shamans conducting a ritual in this memorial site. To put this differently, in a concerted effort to overcome the socially divisive consequences of shamanic ritual acts upon the Tuvan landscape (cf. Lindquist 2011), this “imagined community” of religious artisans and lay pilgrims would use the edifying ethos of Buddhism to reinstate order in the world of ancestors and spirits, and heal a land infested with curses as a result of shamanic rivalries and occult violence.

This tense or ambiguous interplay between subversive shamanic agencies and Buddhism, as a national Tuvan religion promoting sociopolitical cohesion, bears an analogy with the phenomenon of a pandemic of shamans, which the anthropologist Ippei Shimamura has highlighted in his studies of Mongolian shamanism (2017, 2014). Central to this analysis of Mongolia’s post-socialist transition into a market economy, which is permeated by prestige-driven competitiveness and upward social mobility, is the proliferation of shamans through practices of initiation and ritual ordination. In Ulaanbaatar, the upsurge of “cultish” activities is perceived as a plague of shamanic cult organizers and disciples, who propagate their “ongod” ancestral spirits, while uttering prophesies in rituals and offering guidance and succor to their kin. In a politically transformed environment, shamans of different ethnic origins rediscover their “root” (ongod) spirits. As these devotees are “claimed” by their “ongod” spirits in possession rituals, they overturn or fracture social norms and kin-based loyalties through inspirational techniques which yield religious innovations (Shimamura 2017: 111 ff.; see also Swancutt 2012). Shimamura argues that the resurgence of shamans in a veritable flood challenges historically entrenched perceptions of otherness and backwardness, which the ethnic majority of Khalkha Mongols have held in respect of the non-Buddhist ethnic groups of Mongolia, such as the Mongol Buryats or the Darkhad and the Tsaatan (Tuvan) reindeer pastoralists in the northern fringes of the country. In this political landscape, where the visibility of religious practices reverses the earlier (socialist) dogma of disavowing religions, the Buryats’ shamanic activities proliferate like a border-crossing phenomenon (Shimamura 2014: 33). Moreover, in contrast to the rigid and spatially circumscribed forms of Buddhist liturgical rituals, the shamanic practices of the Buryats are a nomadic operation, whose cult members multiply horizontally in a “guerrilla-like” pattern (ibid. 2014: 34).

Likewise, the case of a protest cult of spirits reappearing in their homeland reveals a shamanic agency which is intent on upending or disassembling a line of genealogical continuity. In this light, the Buddhist priest’s public exhortation to perform a healing rite of re-connecting with the land and cleansing it from a spiritual plague can be interpreted as a reinvention of kinds of knowledge anchored in this community’s past. In the above narrative, the priest promulgates a disengaged or dispassionate ritual modality as a means to stop an accelerating crisis, during which the lives of young people are overturned by the reappearance of shamanic spirits and dead ancestors. Importantly, the escape from this tragic impasse is envisaged as a collective ritual of healing a curse-infested land rather than as a shaman’s endowment or exclusionary right to repossess spirits as a proprietor of (incorporeal) agencies. The data of this case signify the preponderance of a collectivist religious modality, which is attuned to the unforeseen implications of inhabiting a landscape infested with familiar – albeit alienated and disowned – shamanic spirits living in their silent horribleness. Carrying on the allure and mystique of a secret government protocol for radioactive contamination or nuclear emergencies, this ritual modality amplifies a sense of revitalizing and re-enchanting a landscape, which has become inert and profane due to the sordid motives of state shamans – and dark magicians – and politicians colluding with each other.

6. Conclusions

Evidence emerges of a new ethics of spiritual revival and re-enchantment, which resuscitates a dying people and their land (cf. Vitebsky 2002) and renders this land’s entities – including the alienated and homeless shamanic spirits – impervious to the effects of combative (quasi-shamanic) politics across a space extending from Kyzyl to Kremlin and, even further, to Russia’s turbulent and militarized frontiers. This (imagined) imbrication of shamans and state agents as ethnic frontiersmen, whose activities augment Russia’s military aggression, emerges from recent accounts about an alleged task force involving shamans, who are loyal to Kremlin. According to these rumours, shortly after President Putin’s plan of attack against Ukraine was publicized (on 22 February 2022), this task force sacrificed an alive bear in the depths of the Southern Siberian taiga in order to backup and promote Putin’s plan. On hearing about this initiative, Vladimir Putin allegedly confided to his Minister of Defence, Sergei Shoigu (who is a native of Tuva), that he would be keen on participating in a shamanic ritual in Siberia.

4

This imaginary of a group of shamans, who prey on the reserves of Siberian wilderness to support Russia’s war, offers an extraordinary insight on classical paradigms of Russia as an interstitial space between Europe and Asia (see Humphrey 2014). As models constitutive of Russian political geography, these paradigms challenged received portrayals of Europe as a paragon of social progress and focused on Russia’s imperial landmass as an independent and self-contained civilization, which is distinct from Europe and Asia. This emphasis on Russia’s geographical cohesiveness and continuity alongside its East European and West Siberian plains legitimized a nineteenth century manifesto, which posited that this continental space was predestined for Russian settlement (Bassin 1991: 11). This ideology of “manifest destiny”, which explained an “ecumene” of Russian settlers in Siberia as an organic process, underpins the imagination of Eurasian Russia and its external contours as a sacred and inviolable space in contrast to the perceived materiality-profanity of the outside world (see Humphrey 2014: 60).

Of special relevance for this discussion of synergies between shamanic operators, working remotely, and the federal government in Moscow is Humphrey’s observation that the Russian concept of Eurasia is enacted by diverse sociopolitical constituencies relating to frontier zones. As Humphrey notes, this image of Eurasia as an “autarchic spiritual bulwark” between East and West is embodied in hybrid formations of power extending along Russia’s border with China. These social constituencies, which range from military and security apparatuses to activist groups of non-Russian nationalities and Cossacks (mobilized as vigilantes or part-time border guards in the turbulent 1990s and later) coalesce into a zone of purity and spiritual defence against the wild terrains of the “other”. This purifying essence of marking the borders is manifested in the Cossacks’ pilgrimages and rituals of rejuvenation, through which they reaffirm their loyalty to their forebears’ Orthodox heritage as Russia’s national subjects (Humphrey 2014: 65, ff.).

What the above rumours about hyper-loyal shamans and governmental elites suggest is a particular Russian political imagination of the repressed shamans’ “rebel cults” in the 1940s and their transformation into a post-colonial outpost of a militarized state, which strategically converts political violence and warfare into lawfare (cf. Comaroff and Comaroff 2016: 30 ff.) As the Comaroffs observe, a key characteristic of modern state sovereignty involves a fetishism for re-embracing policing and the law; namely, drawing boundaries between rights-bearing citizens and sinister strangers, who are designated as agents of lawlessness. In this context, the dispersal of the state’s monopoly as a guarantor of national security has given rise to a number of striking “permutations of order” (see Kirsch and Turner 2009). The expansion of the state’s ideology as a sovereign guarantor of security through various operations, such as “self-securitizing religious and ethnic communities” (see Comaroff and Comaroff 2016: 37), is revealing for the present documentation of how shamanic agents may pull metaphysical strands from the apparatus of a criminal neocolonial state.

Funding

Removed for peer review.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original data collected during fieldwork in Tuva Republic are all included in this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 |

A common female Tuvan name, which is translated as “Black Girl”. Nonetheless, as a precious testimony to a profound or esoteric meaning associated with this ancestor’s mythical abilities for cursing her political persecutors to the death, the Headman ingeniously coined the following explanation fitting this ancestor’s biography. According to this, her name could also be translated as the “Revengeful Girl”, since “Kara” means “punishment” in Russian. Viewed as a set of intertwined linguistic symbols, the versions of Tuvan and Russian “Kara” take on connotations of dark revenge associated with the soul of a venerable shamanic ancestor. |

| 2 |

The last letter of the word karaŋ (n) is pronounced as a nasal final. Both of these words are stressed in the final syllable. |

| 3 |

A variant form of the term “burkhan”, relating to communicable diseases, appears in Shirokogoroff’s magnum opus on shamanism among the Tungus pastoralists of Eastern Siberia and Manchuria. Among several of these ethnic units, the term “burkan” denoted a class of diseases (e.g. influenza), which, nonetheless, were attributed to pathological causes rather than to affliction with spirits (1935: 97). |

| 4 |

Sources: “Putin news: Russian ‘Shamans’ call on ‘earth’s spirits’ to aid war in Ukraine”, Express.co.uk, retrieved on 31/5/2022). “Sacrificing Art for War: The Handover of Russia’s Trinity Icon - Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center (carnegieendowment.org), retrieved on 10/6/2024. |

References

- Anonymous. 2021. Shamanic Dialogues with the Invisible Dark in Tuva, Siberia – The Cursed Lives. Cambridge Scholars Publishing, Newcastle upon Tyne.

- Anonymous. 2020. “Shamanism, Occult Murder, and Political Assassination in Siberia and Beyond”. Made in China Journal, vol. 5 (2): 154-159. [CrossRef]

- Anonymous. 2015. “The Origins and Reinvention of Shamanic Retaliation in a Siberian City (Tuva Republic, Russia)”. Journal of Anthropological Research, vol. 71 (3): 401-422. [CrossRef]

- Anonymous. 2013. “Shirokogoroff’s Psychomental Complex as a Context for Analyzing Shamanic Mediations in Medicine and Law (Tuva, Siberia)”. SHAMAN: Journal of the International Society for Academic Research on Shamanism vol. 21 (1-2): 81-102.

- Anderson, David and Arzyutov, Dmitry. 2016. “The Construction of Soviet Ethnography and the “Peoples” of Siberia”. History and Anthropology, vol. 27 (2): 183-209. [CrossRef]

- Anisimov, Arkadii Fedorovich. 1958. Religiya Evenkov v istoriko-geneticheskom izuchenii i problemy proishozhdeniya pervobytnykh verovanii (The Religion of the Evenki in the study of history and genesis, and problems of the origin of primeval beliefs). Izdatel’stvo AH CCCP.

- Balzer, Mandelstam Marjorie. 2021. Galvanizing Nostalgia? Indigeneity and Sovereignty in Siberia. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press.

- Balzer, Mandelstam Marjorie. 1999. The Tenacity of Ethnicity: A Siberian Saga in Global Perspective. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Bassin, Mark. 1991. “Russia between Europe and Asia: The Ideological Construction of Geographical Space”. Slavic Review, vol. 50 (1): 1-17. [CrossRef]

- Bloch, Alexia and Kendall, Laurel. 2004. The Museum at the End of the World: Encounters in the Russian Far East. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Comaroff, Jean and Comaroff, John. 2016. The Truth about Crime: Sovereignty, Knowledge, Social Order. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Delaplace, Grégory. 2020. “Enchanting democracy: facing the past in Mongolian shamanic rituals”. In Reassembling Democracy: Ritual as Cultural Resource. Eds. Graham Harvey et. al., pp. 53-68. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Ginzburg, Carlo. 1990. Ecstasies: Deciphering the Witches’ Sabbath. Hutchinson Radius (First published in 1989).

- Højer, Lars. 2009. “Absent Powers: magic and loss in post-socialist Mongolia”. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, vol. 15 (3): 575-591. [CrossRef]

- Hoppál, Mihály. 1998. Shamanism: Selected Writings of Vilmos DiÓszegi. Budapest: Akadémiai KiadÓ.

- Humphrey, Caroline. 2012. “Concepts of “Russia” and their Relation to the Border with China”. In Frontier Encounters: Knowledge and Practice at the Russian, Chinese and Mongolian Border. Eds. Franck Billé et. al., pp. 55-70.

- Humphrey, Caroline. 2004. “Stalin and the Blue Elephant: Paranoia and Complicity in Post-Communist Metahistories”. In Transparency and Conspiracy: Ethnographies of Suspicion in the New World Order. Eds. Harry West and Todd Sanders, pp. 175-203. Duke University Press.

- Ingold, Tim. 1994. “Humanity and Animality”. In Companion Encyclopedia of Anthropology: Humanity, Culture, and Social Life. Ed. Tim Ingold, pp. 14-32. London: Routledge.

- Kenin-Lopsan, Mongush Borakhovich. 1995a. Algyshy Tuvinskikh Shamanov (The Algysh Chants of Tuvan Shamans). Kyzyl: “Novosti Tyvy”.

- Kenin-Lopsan, Mongush Borakhovich. 1995b. “Tuvan shamanic folklore”. In Culture Incarnate: Native Anthropology from Russia. Ed. Marjorie Mandelstam Balzer, pp. 215-254. M. E. Sharpe Publications.

- King, Alexander. 1999. “Soul Suckers: Vampiric Shamans in Northern Kamchatka, Russia”. Anthropology of Consciousness, vol. 10 (4): 57-68. [CrossRef]

- Kirsch, Thomas and Turner, Bertram. 2009. Permutations of Order: Religion and Law as Contested Sovereignties. London: Routledge.

- Kwon, Heonik. 2000. “To Hunt the Black Shaman: Memory of the Great Purge in East Siberia”. Etnofoor, vol. 13 (1): 33-50.

- Lindquist, Galina. 2011. “Ethnic Identity and Religious Competition: Buddhism and Shamanism in Southern Siberia”. In Religion, Politics, and Globalization: Anthropological Approaches. Eds. Galina Lindquist and Don Handelman, pp. 69-90. Oxford and New York: Berghahn.

- Levi-Strauss, Claude. 1963. “The Effectiveness of Symbols”. In Structural Anthropology, ed. Claude Levi-Strauss, pp. 186-205. Basic Books.

- Lewis, Ioan. 1971. Ecstatic Religion: an anthropological study of spirit possession and shamanism. London: Penguin Books.

- Markus, Sergei. 2006. Tyva: Slovar’ Kultury (Tyva: a Dictionary of Culture). Moskva: Akademicheskii Proekt Triksta.

- Morris, Brian. 2004. Religion and Anthropology: A Critical Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Obeyesekere, Gananath. 1990. The Work of Culture: Symbolic Transformation in Psychoanalysis and Anthropology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Obeyesekere, Gananath. 1981. Medusa’s Hair: An Essay on Personal Symbols and Religious Experience. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Obeyesekere, Gananath. 1977. “Social Change and the Deities: Rise of the Kataragama Cult in Modern Sri Lanka”. Man, New Series (Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute), vol. 12 (3-4): 377-396. [CrossRef]

- Obeyesekere, Gananath. 1975. “Sorcery, Premeditated Murder, and the Canalization of Aggression in Sri Lanka”. Ethnology, vol. 14 (1): 1-23. [CrossRef]

- Roberts, Simon (2013). Order and Dispute: An Introduction to Legal Anthropology. Quid Pro Books. First published in 1979 by Penguin Books, London.

- Samuel, Geoffrey. 1993. Civilized Shamans: Buddhism in Tibetan Societies. Washington and London: Smithsonian Institute Press.

- Schwieger, Peter. 2009. “Tuvinian Images of Demons from Tibet”. In Tibetan Studies in Honor of Sampten Karmay. Eds. Francoise Pommaret and Jean-Luc Achard, pp. 331-336. Dharamsala: Amnye Machen Institute.

- Shimamura, Ippei. 2017. “A Pandemic of Shamans: The overturning of social relationships, the fracturing of community, and the diverging of morality in contemporary Mongolian shamanism”. SHAMAN: Journal of the International Society for Academic Research on Shamanism, vol. 25 (1-2): 95-136.

- Shimamura, Ippei. 2014. The Roots Seekers: Shamanism and Ethnicity among the Mongol Buryats. Yokohama: Shumpusha Publishing.

- Shirokogoroff, Sergei. 1935. Psychomental Complex of the Tungus. London: Kegan Paul.

- Soyan Peemot, Victoria. 2024. The Horse in my Blood: Multispecies Kinship in the Altai and Saian Mountains. London: Berghahn.

- Soyan Peemot, Victoria. 2019. “Emplacing Herder-Horse Bonds in Ak-Erik, South Tyva”. In MultispeciesHousehold in the Saian Mountains: Ecology at the Russia-Mongolia Border. Eds. Oehler, Alex and Varfolomeeva, Anna, pp. 51-70. London: Lexington Books.

- Swancutt, Katherine. 2012. Fortune and the Cursed: The Sliding Scale of Time in Mongolian Divination. London: Berghahn Books.

- Takakura, Hiroki. 2006. “Indigenous Intellectuals and Suppressed Russian Anthropology: Sakha Ethnography from the End of the Nineteenth Century to the 1930s”. Current Anthropology, 47 (6): 1009-1116. [CrossRef]

- Telle, Kari. 2016. “Ritual Power: Risk, Rumours, and Religious Pluralism on Lombok”. The Asia Pacific Journal of Anthropology, vol. 17 (5): 419-438. [CrossRef]

- Torri, Davide. 2020. Landscape, Ritual, and Identity among the Hyolmo of Nepal. London: Routledge.

- Vallikivi, Laur and Sidorova, Lena. 2017. “The Rebirth of a People: Reincarnation Cosmology among the Tundra Yukaghir of the Lower Kolyma, Northeast Siberia”. Arctic Anthropology, vol. 54 (2): 24-39. [CrossRef]

- Vitebsky, Piers. 2001. Shamanism. University of Oklahoma Press.

- Vitebsky, Piers and Alekseyev, Anatoly. 2020. “Indigenous Arctic religions”. In Routledge Handbook of Indigenous Peoples in the Arctic. Ed. Koivurona, Timo et al., pp. 106-121. London: Routledge.

- Vitebsky, Piers and Alekseyev, Anatoly. 2020. “Velocity and Purpose among Reindeer Herders in the Verkhoyansk Mountains”. Inner Asia, vol. 22 (1): 28-48. [CrossRef]

- Vitebsky, Piers and Alekseyev, Anatoly. 2015. “Siberia”. Annual Review of Anthropology, vol. 44 (1): 439-455. [CrossRef]

- Vitebsky, Piers. 2002. “Withdrawing from the Land: social and spiritual crisis in the Indigenous Russian Arctic”. In Post-socialism: ideals, ideologies and practices in Eurasia. Ed. Chris Hann, pp. 180-195. London: Routledge.

- Willerslev, Rane. 2007. Soul Hunters: Hunting, Animism, and Personhood among the Siberian Yukaghirs. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

- Znamenski, Andrei. 2004. Shamanism in Siberia: Russian Records of Indigenous Spirituality. Kluwer Academic Publishers.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).