Submitted:

27 June 2024

Posted:

27 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Economic, Environmental and Social Dimensions of the Fashion Industry

1.2. Consumer Preferences for Sustainable Fashion

1.3. Theory: Nudges and Consumer Preferences

2. Materials and Methods

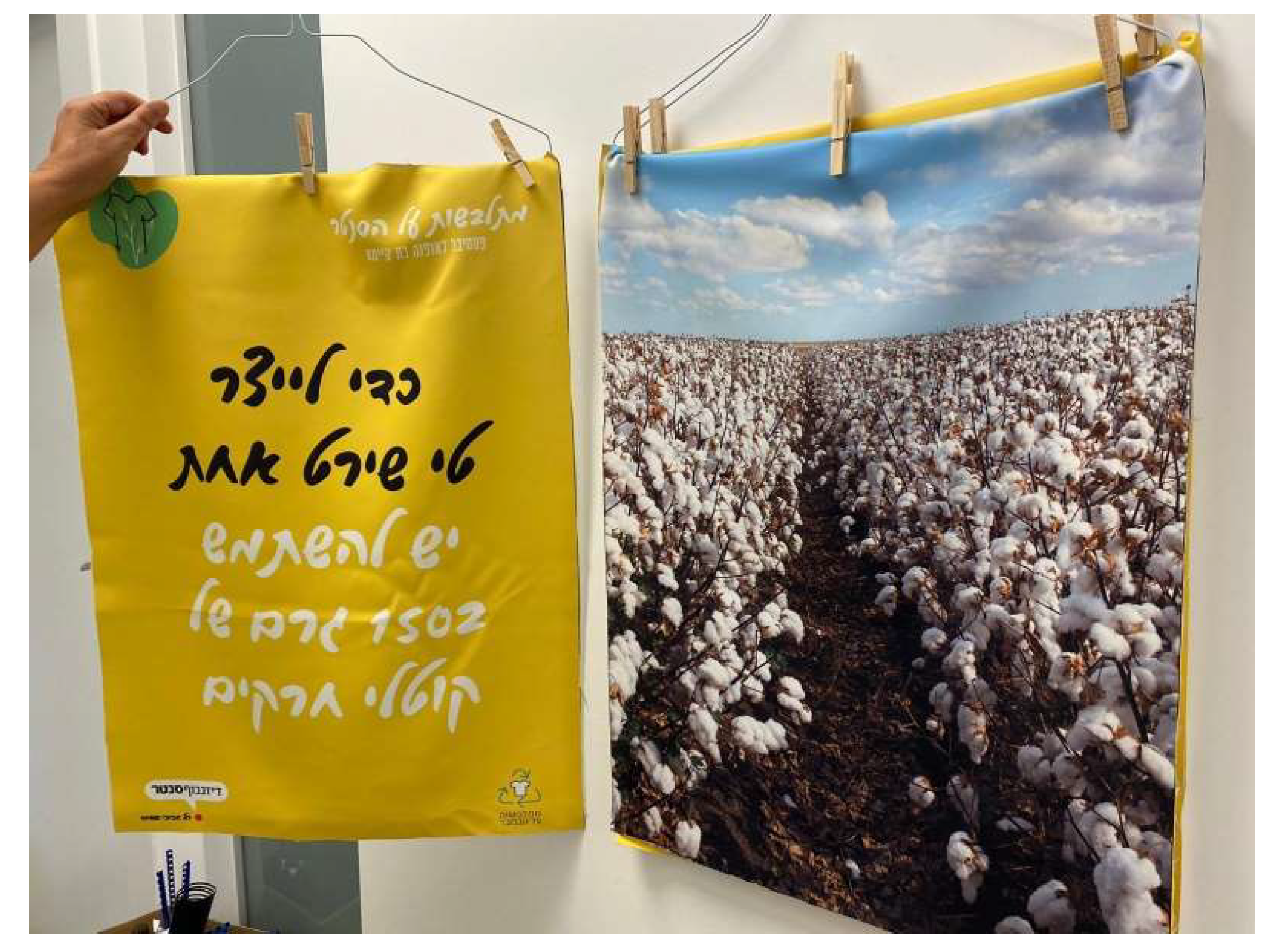

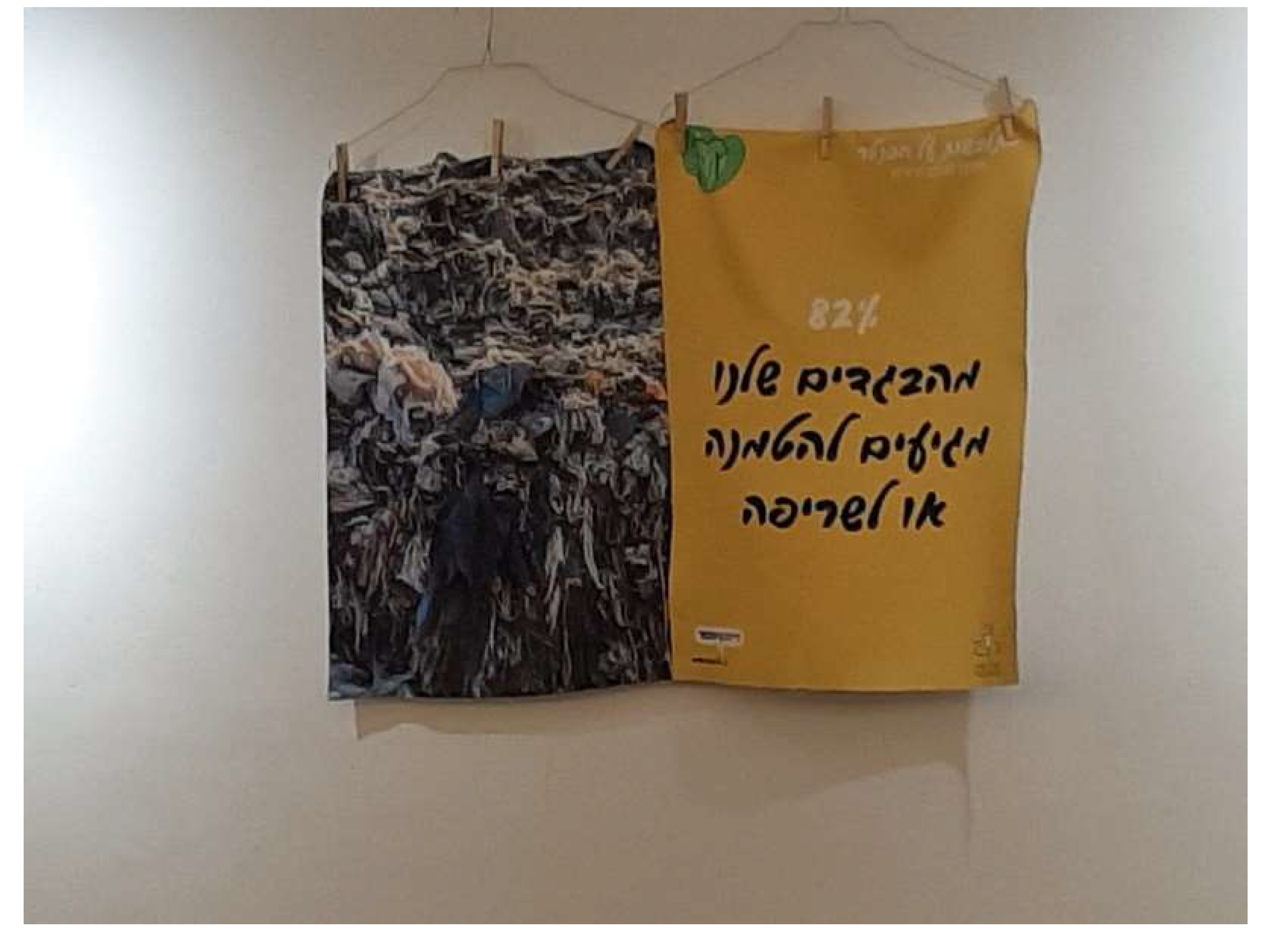

2.1. Nudge 1: Knowledge: Providing Information to Consumers, About the Environmental and Social Damages of the Fashion Industry

- “Fast and cheap fashion is not really cheap, somewhere someone else is paying the full price”

- “We have enough clothes in the world for the next fifty years"

- "Over 64% of women workers in textile factories say that they suffer physical and verbal abuse every day".

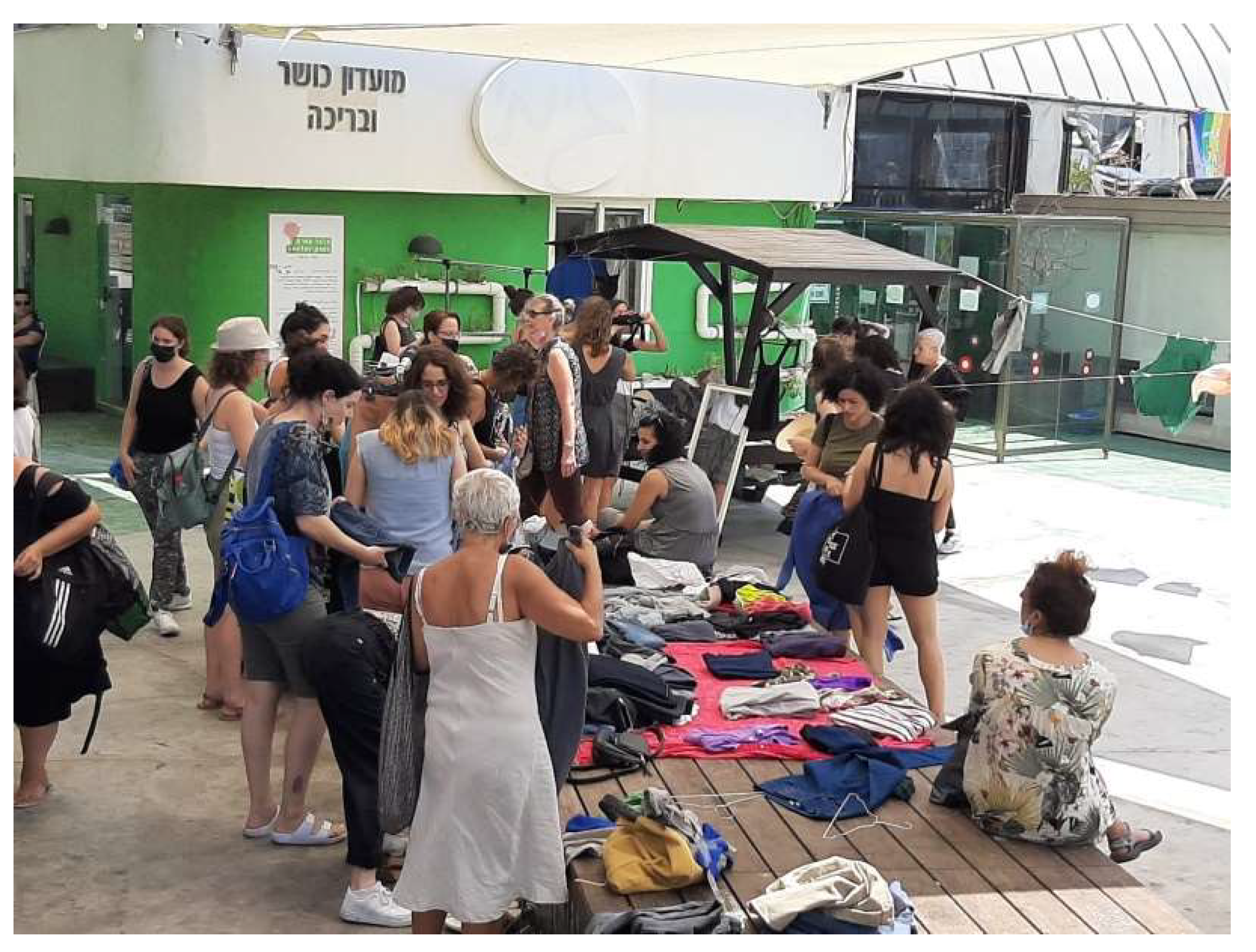

2.2. Nudge 2: Increased the Sustainable Fashion Alternatives within the Mall

2.3. Nudge 3: Highlighting the Social Identity Involved in Purchasing Sustainable Fashion

- Demographics: Age, gender, major occupation in life and identify of people with whom they came to shop.;

- Impact on Consumption: Did they purchase clothing items, and if so, how many? Did they notice if they were sustainably produced and how much did they pay for them? (Participants were asked to state the amount of clothing purchased and money spent).

- Attitudes: degree of agreement with several statements regarding sustainable fashion (questions 8-11), and the climate crisis (questions 12-14) on a Likert scale of 1 to 5. For example: "I prefer to buy a single item over several cheap items at the same price", "The climate crisis is a critical crisis and must be addressed urgently"; "I believe there is a connection between my consumer choices and the climate crisis".

- Barriers to purchasing sustainable fashion: These were presented using a nominal scale, with three options (yes/no/I'm not sure). For example: "I feel I know how to distinguish between green and non-green clothes".

- Green self-image: These questions compare self-reported environmental awareness on a Likert scale of 1 to 5 (question 18) with actual green behaviors on a descriptive nominal scale (question 19). For instance: "My social circle recognizes me as environmentally conscious compared to others," and "Which of these actions do you regularly engage in: donate to environmental organizations, volunteer for green causes, follow a vegan or vegetarian diet, refrain from car ownership, avoid purchasing new clothes, or buy organic products?”

2.4. Dependent and Independent Variables

- Attitudes towards the climate crisis, examined by the degree of agreement with statements about the climate crisis;

- Attitudes regarding fast fashion and sustainable fashion, tested by the degree of agreement with the statements on fashion;

- Perceived green self-image tested by both self-perception and reported actions;

- Willingness to pay more (WTPM) for sustainable fashion, based on the ratio between the amount of clothing items purchased, and the total expenditure on clothing;

- Barriers facing sustainable fashion, tested by the degree of agreement with statements concerning the consumers' fashion purchases at the time of the experiment;

- Independent variables are:

- Type of intervention (providing information / increasing alternatives / social identity);

- Common environmental behaviors;

- The social group with which respondents came to the mall (family, friends, alone, etc.). And;

- General demographic characteristics.

3. Results

3.1. General

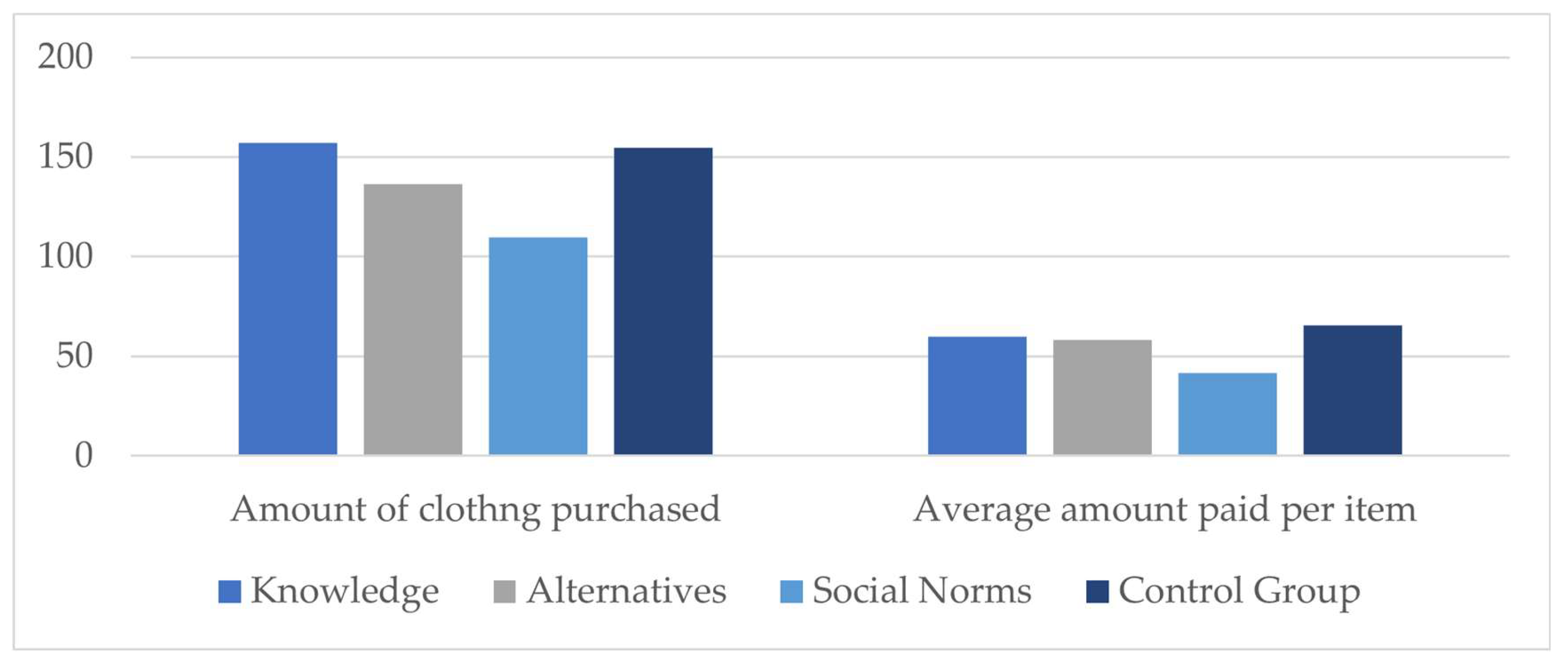

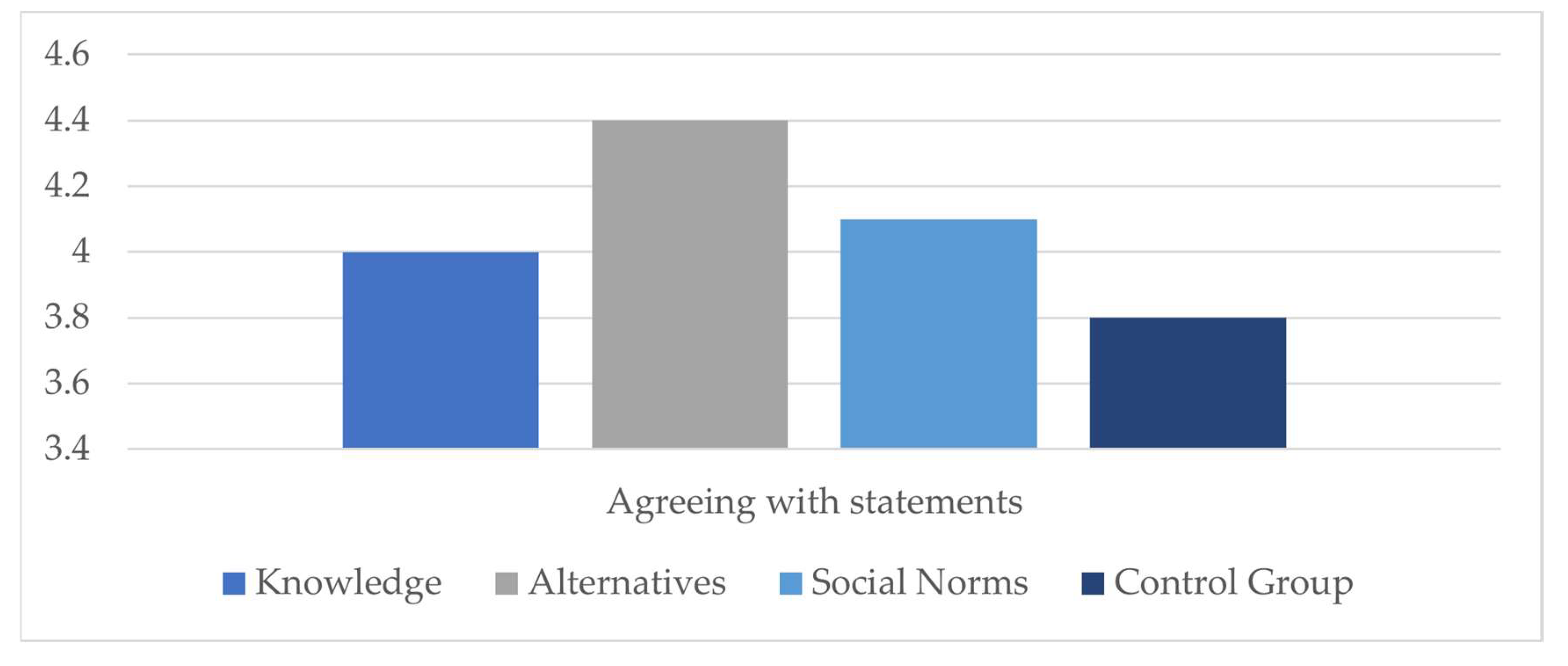

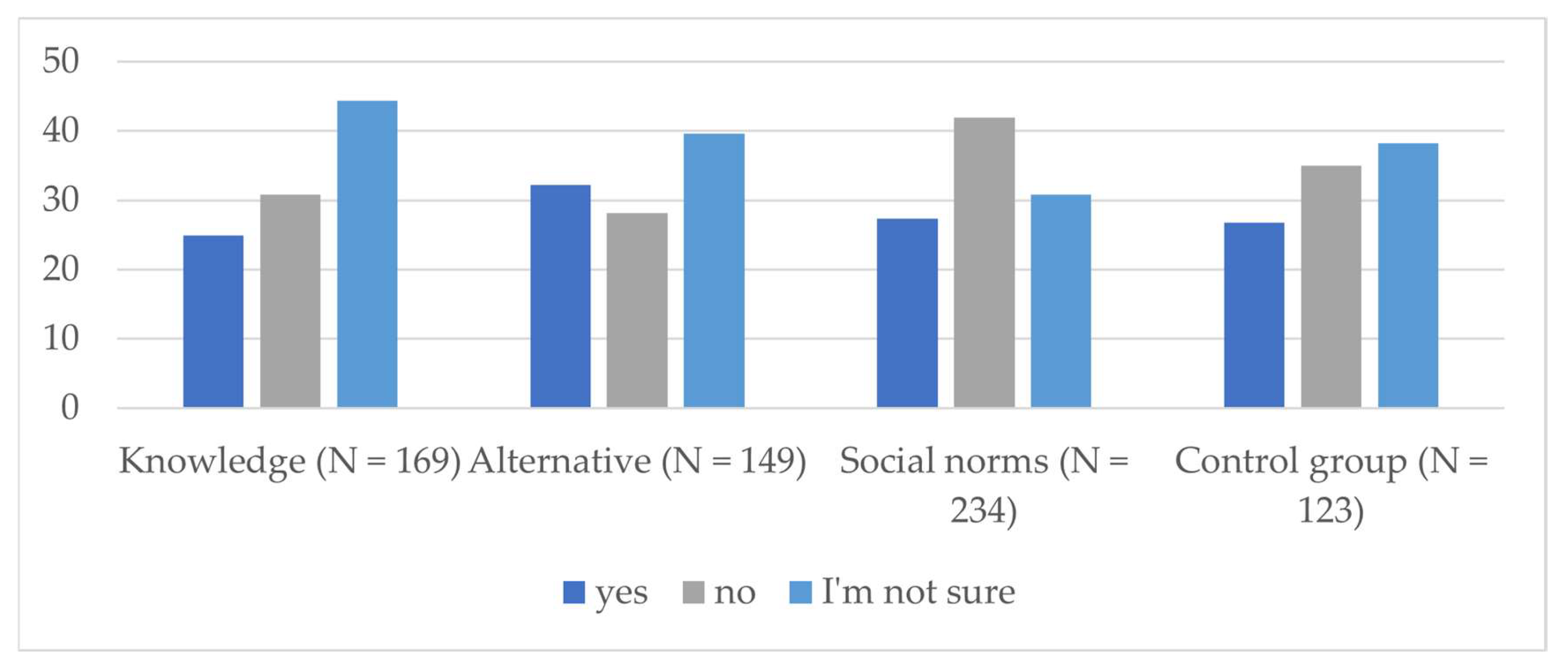

3.2. Differences between the Intervention Conditions

3.3. Analysis based on Demographic Characteristics

3.3.1. Gender

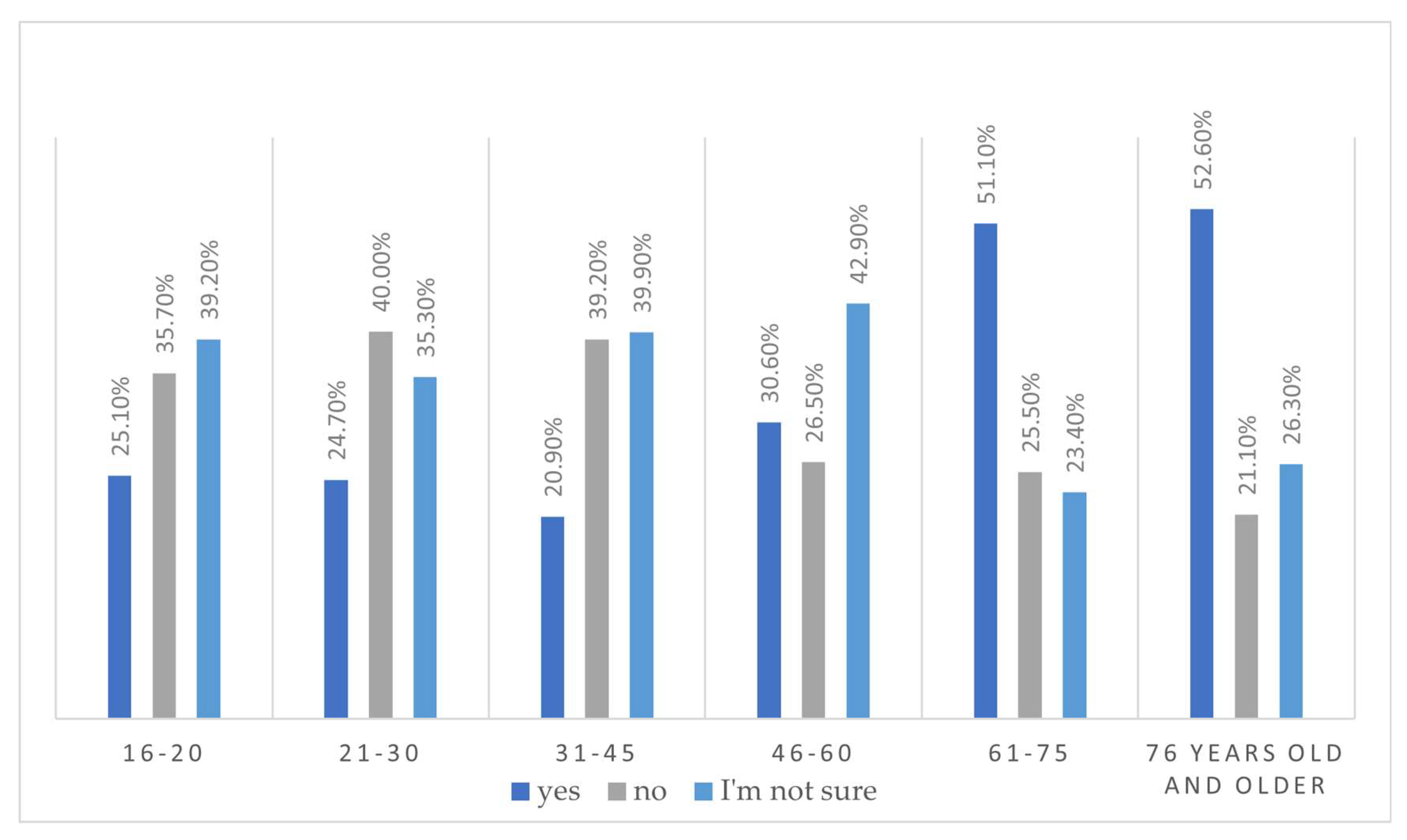

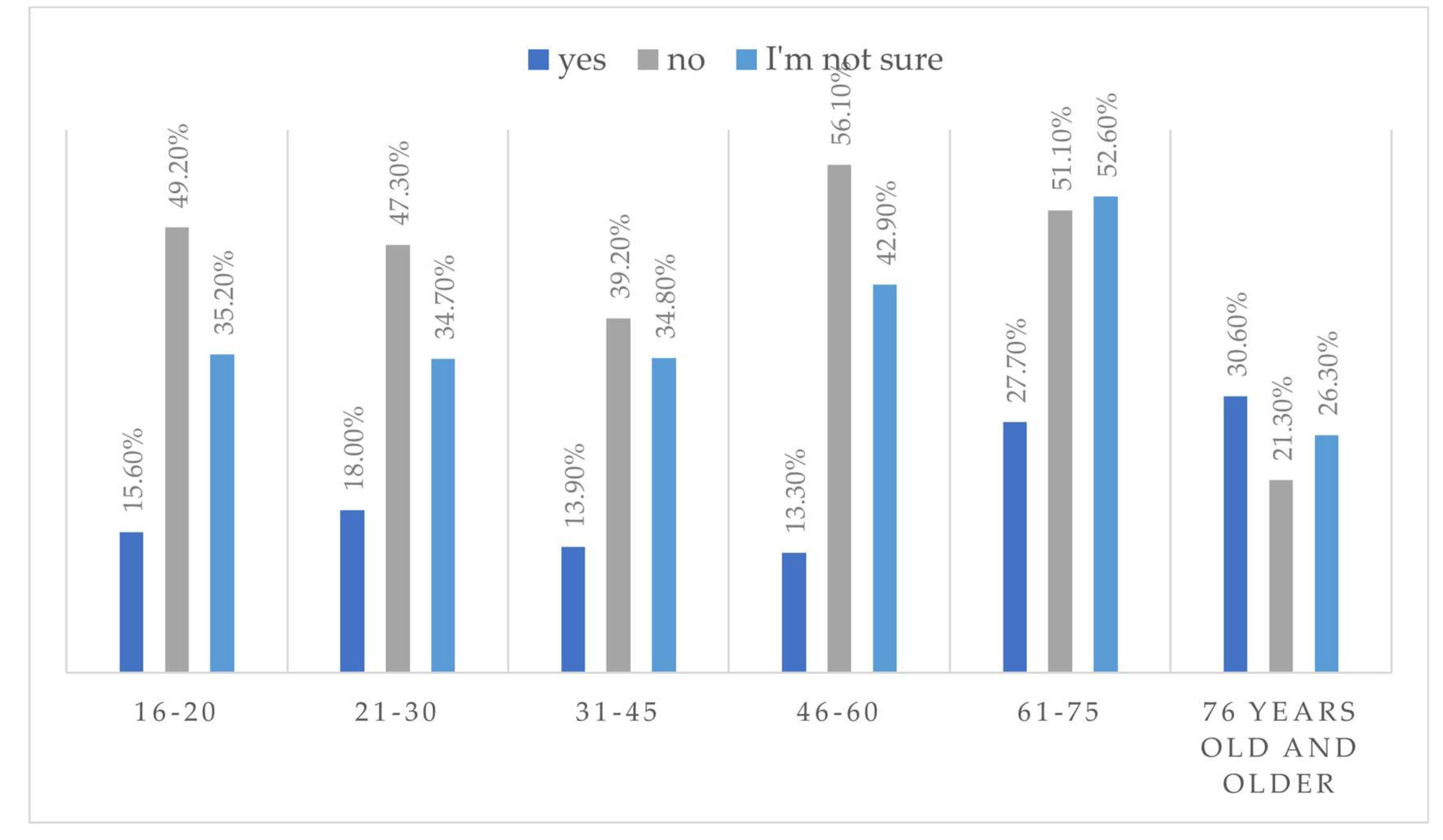

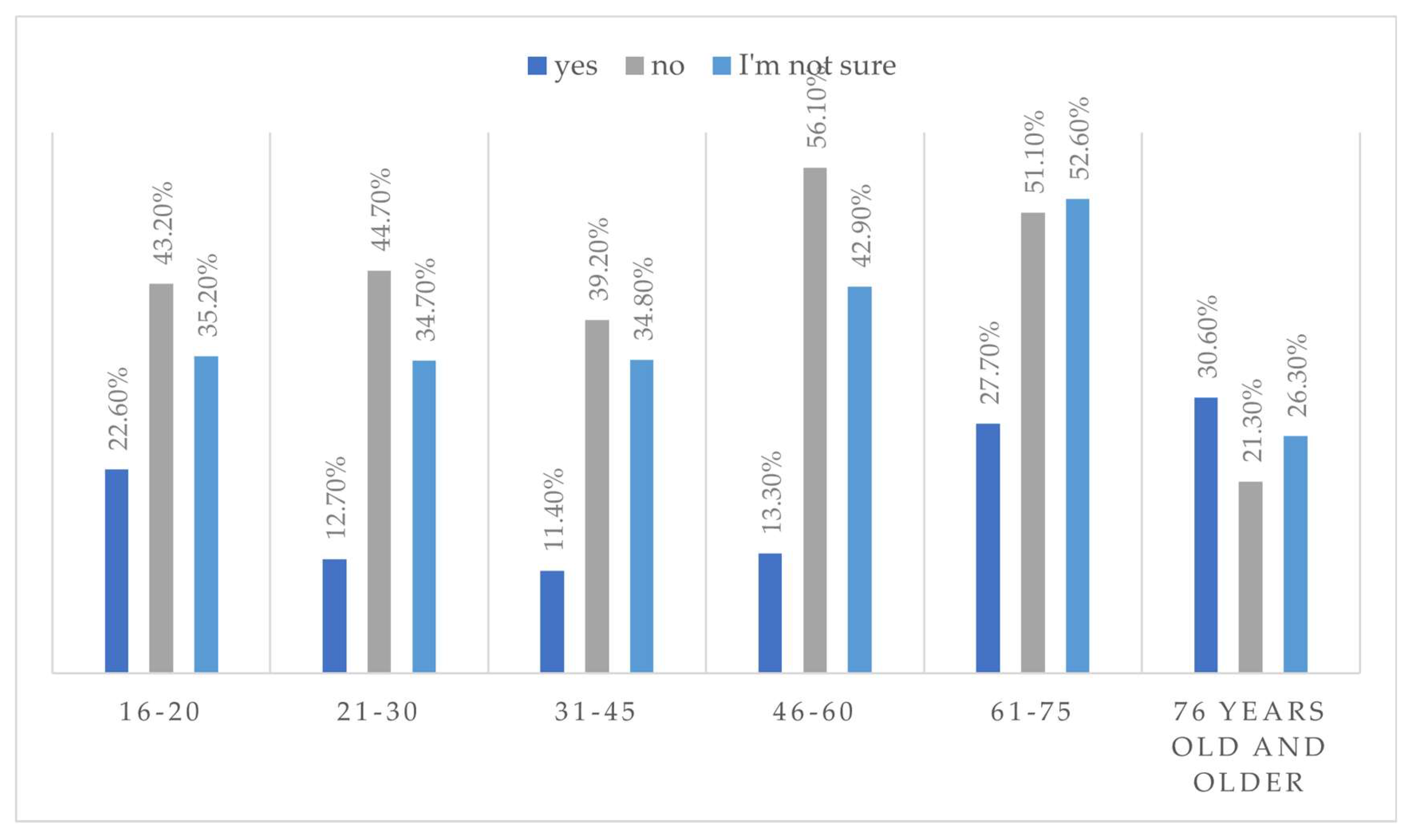

3.3.2. Age

3.4. Analysis of Variance

4. Discussion

4.1. Demographic Nuances: A Surprising Generation Gap

5. Conclusions

5.1. Greenwash and Reliability in Fashion

5.2 The Gap between Consumer Statements and Their Actual Purchases

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

- • Eighty thousand toxic chemicals are used in the process of dyeing the fabrics

- • Fast and cheap fashion is not really cheap, somewhere someone else is paying the full price

- • In order to produce one pair of jeans, it takes the amount of water that a person drinks for 7.5 years

- • It takes 2700 liters of water to produce one t-shirt

- • We have enough clothes in the world for the next fifty years

- • Over 64% of women workers in textile factories say that they suffer physical and verbal abuse every day

- • 21 % of the clothes we own will never be worn

- • 80% of the time we wear 20% of the clothes in our closet

- • Raising animals for wool consumes a huge amount of resources. In a country with 300 sunny days a year do we really need another sweater?

- • Did you know? Polyester made from petroleum

- • The decomposition process of synthetic fabrics takes several hundred years, please think wisely before throwing them away

Appendix C

| I don’t agree at all 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Strongly agree 6 |

| I don’t agree at all 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Strongly agree 6 |

| I don’t agree at all 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Strongly agree 6 |

| I don’t agree at all 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Strongly agree 6 |

| I don’t agree at all 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Strongly agree 6 |

| I don’t agree at all 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Strongly agree 6 |

| I don’t agree at all 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Strongly agree 6 |

| I don’t agree at all 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Strongly agree 6 |

References

- Rahman, O.; Hu, D.; Fung, B.C.M. A Systematic Literature Review of Fashion, Sustainability, and Consumption Using a Mixed Methods Approach. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niinimäki, K.; Peters, G.; Dahlbo, H.; et al. The environmental price of fast fashion. Nat Rev Earth Environ 2020, 1, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, S. F. Impact of the Accord and Alliance on labor productivity of the Bangladesh RMG industry. Doctoral dissertation, Brac University, 2020.

- EU strategy for sustainable and circular textiles. Available online: https://environment.ec.europa.eu/publications/textiles-strategy_en (accessed on 25 June 2024).

- ReSet the Trend - #ReFashionNow-Become a role model! Available online: https://environment.ec.europa.eu/topics/circular-economy/reset-trend_en (accessed on 25 June 2024).

- Astrid, C,; Saskia, C. ; Hendrik, S. Organizational characteristics explaining participation in sustainable business models in the sharing economy: Evidence from the fashion industry using conjoint analysis. Business Strategy and the Environment 2020, 29:6, 2603-2613. [CrossRef]

- Lotfi, M.; Boote, A. The unsustainable impact of patriarchy on the industry. Lampoon Magazine 2023, 27, https://lampoonmagazine.com/article/2023/03/28/the-unsustainable-impact-of-patriarchy-on-the-industry-maryam-lofti-with-amy–boote/. [Google Scholar]

- Children’s rights in the garment and footwear supply chain. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/reports/childrens-rights-in-garment-and-footwear-supply-chain-2020 (accessed on 25 June 2024).

- Dzhengiz, T.; Haukkala, T.; Sahimaa, O. (Un)Sustainable transitions towards fast and ultra-fast fashion. Fash Text 2023, 10, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 10 Truly Oppressive Working Conditions Of The Clothing Industry. Available online: https://citi.io/2017/03/23/10-truly-oppressive-working-conditions-of-the-clothing-industry/ (accessed on 25 June 2024).

- Pal, R.; Gander, J. Modelling environmental value: An examination of sustainable business models within the fashion industry. Journal of Cleaner Production 2018, 184, 251–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Business of Fashion, & McKinsey & Company. The state of fashion 2017. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/McKinsey/Industries/Retail/Our%20Insights/The%20state%20of%20fashion/The-state-of-fashion-2017-McK-BoF-report.pdf (accessed on 25 June 2024).

- Franklin-Wallis, O. Wasteland: The Secret World of Waste and the Urgent Search for a Cleaner Future, 1rd ed.; Hachette Books: New York, New York, 2023; pp. 117–156. [Google Scholar]

- Bick, R. ; Halsey, E.; Ekenga, C.C. The global environmental injustice of fast fashion. Environ Health 2018, 17, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Changing Markets Foundation & STAND. Synthetics Anonymous- Fashion brands’ addiction to fossil fuels. Changing markets foundation 2021. Available online: http://changingmarkets.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/SyntheticsAnonymous_FinalWeb.pdf (accessed on 25 June 2024).

- Mäkinen, K. Clothing rental – service development proposals through service design. master thesis, Turku University of Applied Sciences, Turku, Finland, 2019. https://www.theseus.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/226728/Makinen_Kaisa.pdf.

- Manieson, L.A. ; Ferrero-Regis, T. Castoff from the West, pearls in Kantamanto? A critique of second-hand clothes trade. Journal of industrial ecology, a: content-type="lang, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Business of Fashion, & McKinsey & Company. The state of fashion 2022. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/industries/retail/our%20insights/state%20of%20fashion/2022/the-state-of-fashion-2022.pdf (accessed on 25 June 2024).

- The Business of Fashion, & McKinsey & Company. The state of fashion 2019. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/industries/retail/our%20insights/fashion%20on%20demand/the-state-of-fashion-2019.pdf (accessed on 25 June 2024).

- Cheng, W.H.; Song, S.; Chen, C.Y.; Hidayati, S.C.; Liu, J. Fashion meets computer vision: A survey. ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR) 2021, 54, 1-41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Circular Economy: A Wealth of Flows - 2nd Edition. Available online: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/the-circular-economy-a-wealth-of-flows-2nd-edition (accessed on 25 June 2024).

- Hwang, J.; Sun, X.; Zhao, L.; Youn, S.-y. Sustainable Fashion in New Era: Exploring Consumer Resilience and Goals in the Post-Pandemic. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holy, M.; Borčić, N. Information, consumerism and sustainable fashion. SUSTAINABLE GROWTH AND DEVELOPMENT IN SMALL OPEN ECONOMIES 2018, 179.

- Hehorn, J.; Ulasewicz, C. . Sustainable Fashion: Why Now? A Conversation Exploring Issues, Practices and Possibilities., 1rd ed.; New York: Fairchild Book: New York, New York, 2008; pp. 24–37. [Google Scholar]

- Peleg Mizrachi, M.; Tal, A. Sustainable Fashion—Rationale and Policies. Encyclopedia 2022, 2, 1154–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Kim, E. Categorizing Chinese Consumers’ Behavior to Identify Factors Related to Sustainable Clothing Consumption. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sustainable Fashion Market Analysis Shows The Market Progress In Attempt To Decrease Pollution In The Global Ethicalfashion Market 2020. Available online: https://www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2020/10/28/2116073/0/en/Sustainable-Fashion-Market-Analysis-Shows-The-Market-Progress-In-Attempt-To-Decrease-Pollution-In-The-Global-Ethicalfashion-Market-2020.html (accessed on 25 June 2024).

- Ethical Fashion Market 2022 - By Product (Organic, Man-Made/Regenerated, Recycled, Natural), By Type (Fair Trade, Animal Cruelty Free, Eco-Friendly, Charitable Brands), By End-User (Men, Women, Kids), and By Region, Opportunities and Strategies – Global Forecast To 2030. Available online: https://www.thebusinessresearchcompany.com/report/ethical-fashion-market (accessed on 25 June 2024).

- Gazzola, P.; Pavione, E.; Pezzetti, R.; Grechi, D. Trends in the Fashion Industry. The Perception of Sustainability and Circular Economy: A Gender/Generation Quantitative Approach. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, S.; Nayak, L. Marketing Sustainable Fashion: Trends and Future Directions. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The global consumer: Changed for good-Consumer trends accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic are sticking. Available online: https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/consumer-markets/consumer-insights-survey/2021/gcis-june-2021.pdf (accessed on 25 June 2024).

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, C.; Lyu, Y. Profiling Consumers: Examination of Chinese Gen Z Consumers’ Sustainable Fashion Consumption. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, S.; Weber, O. How Fashionable Are We? Validating the Fashion Interest Scale through Multivariate Statistics. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, A.; Chanda, R. S. Psychology of consumer: study of factors influencing buying behavior of millennials towards fast-fashion brands. Cardiometry 2022, 23, 360–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, L. R.; Birtwistle, G. An investigation of young fashion consumers' disposal habits. International journal of consumer studies 2009, 2, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lades, L. K. Impulsive consumption and reflexive thought: Nudging ethical consumer behavior. Journal of Economic Psychology 2014, 41, 114–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, N. K. Self concept and product choice: An integrated perspective. Journal of Economic Psychology 1988, 1, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thøgersen, J.; Ölander, F. Human values and the emergence of a sustainable consumption pattern: A panel study. Journal of economic psychology 2002, 23(5), 605–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandarić, D.; Hunjet, A.; Vuković, D. The impact of fashion brand sustainability on consumer purchasing decisions. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 2022, 4, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.-J.; Choi, H.; Han, J.; Kim, D. H.; Ko, E.; Kim, K. H. . How to “nudge” your consumers toward sustainable fashion consumption: An fMRI investigation. Journal of Business Research 2020, 117, 642–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.; Jin, B. A theoretical investigation of slow fashion: Sustainable future of the apparel industry. International Journal of Consumer Studies 2014, 38(5), 510–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramonienė, L. . Sustainability motives, values and communication of slow fashion business owners. Journal of Philanthropy and Marketing, 1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyner, N.; Olofsson, N.; Fager, F. The effect of substantial factors that influence consumers’ purchase decisions on clothes in the Fast Fashion industry in Sweden. A quantitative study of the significant substantial factors which affect Swedish consumers’ purchase decisions when buying Fast Fashion items. Bachelor’s degree project, Jönköping University-Business School, International Management, Jönköping, Sweden, May 2023.

- Joergens, C. Ethical fashion: Myth or future trend? Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management 2006, 10(3), 360–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, R.; Mehlkop, G. Neutralization strategies account for the concern-behavior gap in renewable energy usage–Evidence from panel data from Germany. Energy Research & Social Science 2023, 99, 103041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shein Revenue and Usage Statistics (2024). Available online: https://www.businessofapps.com/data/shein-statistics/ (accessed on 25 June 2024).

- Peleg Mizrachi, M. he Good, the Bad, and the Sustainable: How Technology Has Changed and Continues to Change the World of Fashion, from Cotton Gin to Digital Clothes. In Roadmap to Sustainable Textiles, 1nd ed.; Ayşegül, K., İbrahim, M., Kanat., S., Eds.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaler, R.H. From cashews to nudges: The evolution of behavioral economics. American Economic Review 2018, 108, 1265–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herstein, R. ; Gilboa, S; Gamliel, E. Private and national brand consumers' images of fashion stores, Journal of Product & Brand Management 2013, 22, 5/6, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herstein, R. H; Berger, R. Creating & Managing Brand Image, 1rd ed.; Lambert Academic Publishing: Saarbrücken, Germany, 2015; pp. 57–73. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Ami, M.; Hornik, J.; Eden, D.; Kaplan, O. Boosting consumers' self-efficacy by repositioning the self. European Journal of Marketing 2014, 48, 11–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A.; Dutta, T.; Mishra, A. S. Value-based nudging of ethnic garments: a conjoint study to differentiate the value perception of ethnic products across Indian Markets. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management 2023, 27, 4–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schürmann, C.L.; Helinski, C.; Koch, j.; Westmattelmann, D. DIGITAL NUDGING TO PROMOTE SUSTAINABLE CONSUMER BEHAVIOR? AN EXPERIMENTAL ANALYSIS IN ONLINE FASHION RETAIL. European Conference on Information Systems, Kristiansand, Norway, 11-16.06.2023.

- Yan, S.; Henninger, C.E.; Jones, C.; McCormick, H. Sustainable knowledge from consumer perspective addressing microfibre pollution. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management 2020, 24, 3, 437- 454. [CrossRef]

- Roozen, I.; Raedts, M.; Meijburg, L. Do verbal and visual nudges influence consumers’ choice for sustainable fashion?. Journal of Global Fashion Marketing 2021, 12(1), 4, 327-342. [CrossRef]

- Gossen, M.; Jäger, S.; Lena Hoffmann, M.; Bießmann, F.; Korenke, R.; Santarius, T. Nudging Sustainable Consumption: A Large-Scale Data Analysis of Sustainability Labels for Fashion in German Online Retail. Frontiers in Sustainability 2022, 2022. 3, 922984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijssen, S. R.; Pijs, M.; van Ewijk, A.; Müller, B. C. Towards more sustainable online consumption: The impact of default and informational nudging on consumers’ choice of delivery mode. Cleaner and Responsible Consumption 2023, 11, 100135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bicchieri, C.; Dimant, E. Nudging with care: the risks and benefits of social information. Public Choice 2019, 191, 443–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, C. Green nudges: Do they work? Are they ethical?, Ecological Economics 2017, 132, 329-342. [CrossRef]

- Loschelder, D. D.; Siepelmeyer, H.; Fischer, D.; Rubel, J. A. Dynamic norms drive sustainable consumption: Norm-based nudging helps café customers to avoid disposable to-go-cups. Journal of Economic Psychology 2019, 75, 102146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunstein, C. R.; Reisch, L. A. Automatically green: Behavioral economics and environmental protection. Harv. Envtl. L. Rev 2014. 38, 1, 127. [CrossRef]

- Bruns, H.; Kantorowicz-Reznichenko, E.; Klement, K. , Jonsson, M. L.; Rahali, B. Can nudges be transparent and yet effective? Journal of Economic Psychology 2018, 65, 41–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colasante, A.; D'Adamo, I. The circular economy and bioeconomy in the fashion sector: Emergence of a “sustainability bias”. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 329, 129774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairns, H. M.; Ritch, E. L.; Bereziat, C. Think eco, be eco? The tension between attitudes and behaviours of millennial fashion consumers. International Journal of Consumer Studies 2022, 46, 1262–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, L. R.; Birtwistle, G. An investigation of young fashion consumers' disposal habits. International journal of consumer studies 2009, 33,2, 190-198. [CrossRef]

- Negrin, L. Appearance and identity. In Appearance and identity: Fashioning the body in postmodernity. Palgrave Macmillan US: New York, New York, 2008, 9-32.

- Yoh, E. Application of the fashion therapy to reduce negative emotions of female patients. The Research Journal of the Costume Culture 2015, 23,1, 85–101. [CrossRef]

- Munasinghe, P.; Druckman, A.; Dissanayake, D. G. K. A systematic review of the life cycle inventory of clothing. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 320, 128852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehner, M.; Mont, O.; Heiskanen, E. Nudging – A promising tool for sustainable consumption behaviour? Journal of Cleaner Production 2016, 134, 166–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meske, C.; Potthoff, T. THE DINU-MODEL – A PROCESS MODEL FOR THE DESIGN OF NUDGES. In Proceedings of the 25th European Conference on Information Systems (ECIS), Guimarães, Portugal, 2017., June 5-10.

- Momsen, K.; Ohndorf, M. Information avoidance, selective exposure, and fake (?) news: Theory and experimental evidence on green consumption. Journal of Economic Psychology 2022, 88, 102457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, C.; Kurschilgen, M. The fragility of a nudge: the power of self-set norms to contain a social dilemma. Journal of Economic Psychology 2020, 81, 102293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marczak, M.; Winkowska, M.; Chaton-Østlie, K.; Rios, R. M.; Klöckner, C. “When I say I'm depressed, it's like anger.” An Exploration of the Emotional Landscape of Climate Change Concern in Norway and Its Psychological, Social and Political Implications. Research Square. [CrossRef]

- Wood, S. Generation Z as consumers: trends and innovation. Institute for Emerging Issues: NC State University 2013, 119, 9, 7767-7779. https://archive.iei.ncsu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/GenZConsumers.pdf.

- Hwang, C. G.; Lee, Y. A.; Diddi, S. Generation Y's moral obligation and purchase intentions for organic, fair-trade, and recycled apparel products. International Journal of Fashion Design, Technology and Education 2015, 8,2, 97-107. [CrossRef]

- Licence to Greenwash: How certification schemes and voluntary initiatives are fuelling fossil fashion. Available online: https://changingmarkets.org/report/licence-to-greenwash-how-certification-schemes-and-voluntary-initiatives-are-fuelling-fossil-fashion/ (accessed on 26 June 2024).

- Kumar, P.; Polonsky, M.; Dwivedi, Y. K.; Kar, A. Green information quality and green brand evaluation: the moderating effects of eco-label credibility and consumer knowledge. European Journal of Marketing 2021, 55, 7, 2037–2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, C.; Rivetti, F. Assessing Young Consumers’ Responses to Sustainable Labels: Insights from a Factorial Experiment in Italy. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badiei Khorsand, D.; Wang, X.; Ryding, D.; Vignali, G. Greenwashing in the Fashion Industry: Definitions, Consequences, and the Role of Digital Technologies in Enabling Consumers to Spot Greenwashing. In The Garment Economy: Understanding History, Developing Business Models, and Leveraging Digital Technologies, 2 Eds. Cham: Springer International Publishing: Gewerbestrasse Cham, Switzerland, 2023, pp. 81-107.

- McNeill, L.; Moore, R. Sustainable fashion consumption and the fast fashion conundrum: fashionable consumers and attitudes to sustainability in clothing choice. International Journal of Consumer Studies 2015, 39,3, 212-222. [CrossRef]

- Richey, A. K. The Green Gap: How Consumers Value Sustainable Fashion. Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects, 3458. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, L. M.; Shiu, E.; Shaw, D. Who Says There is an Intention– Behaviour Gap? Assessing the Empirical Evidence of an Intention–Behaviour Gap in Ethical Consumption. Journal of Business Ethics 2016, 136 ,2, 219–236. [CrossRef]

- Henninger, C.E.; Singh, P. Ethical Consumption Patterns and the Link to Purchasing Sustainable Fashion. In: Henninger, C., Alevizou, P., Goworek, H., Ryding, D. (eds) Sustainability in Fashion 2016. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Joshi, Y.; Rahman, Z. Factors affecting green purchase behavior and future research directions. International Strategic Management Review 2015, 3, 128–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiederhold, M.; Martinez, L. F. Ethical consumer behaviour in Germany: The attitude- behaviour gap in the green apparel industry. International Journal of Consumer Studies 2018, 42,4, 419– 429. [CrossRef]

- How data is making the business case for sustainable fashion. Available online: https://www.thinkwithgoogle.com/intl/en-emea/consumer-insights/consumer-trends/how-data-making-business-case-sustainable-fashion/ (accessed on 26 June 2024).

- Tetik, C.; Cherradi, O. Attitude-Behavior Gap in sustainable clothing consumption. Bachelor’s degree project, Jönköping University-Business School, International Management, Jönköping, Sweden, 20. 20 May.

- Sreen, N.; Purbey, S.; Sadarangani, P. Impact of culture, behavior and gender on green purchase intention. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 2018, 41, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.J.; Choi, Y.J.; Oh, K.W. Influencing Factors of Chinese Consumers’ Purchase Intention to Sustainable Apparel Products: Exploring Consumer “Attitude–Behavioral Intention” Gap. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peleg Mizrachi, M.; Tal, A. Regulation for Promoting Sustainable, Fair and Circular Fashion. Sustainability 2022, 14, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Man | 224 | 32.9% |

| Woman | 451 | 66.8% |

| With whom did they come to the mall? | ||

| Alone | 208 | 30.8% |

| with friends | 232 | 34.4% |

| with a partner | 79 | 11.7% |

| with family members | 143 | 21.2% |

| Other | 13 | 1.9% |

| Main occupation | ||

| High school student | 150 | 22.2% |

| Soldier | 39 | 5.8% |

| Student | 63 | 9.3% |

| employee/ self- employs | 295 | 43.7% |

| Pensioner | 62 | 9.2% |

| On Maternity Leave | 4 | 0.6% |

| Unemployed | 54 | 8.0% |

| Other | 8 | 1.2% |

| Age | ||

| 16-20 | N=199 | 29.66% |

| 21-30 | N=150 | 22.36% |

| 31-45 | N=158 | 23.55 |

| 46-60 | N=98 | 14.61% |

| 61-75 | N=47 | 7.00% |

| 76 and older | N=19 | 2.83% |

| control (N=123) | knowledge (N=169) | Alternative (N=149) |

social norms N= (234) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | |

| The amount of purchase | 300.6 | 154.7 | 256.8 | 157.2 | 233.8 | 136.6 | 201.4 | 109.8 |

| Number of items purchased | 2.4 | 1.5 | 2.4 | 1.7 | 2.1 | 1.6 | 2.3 | 1.4 |

| Average amount spent on an item | 130.3 | 65.5 | 99.1 | 59.9 | 124.6 | 58.3 | 71.4 | 41.5 |

| control (N=123) | knowledge (N=169) | Alternative (N=149) |

social norms N= (234) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | |

| Agreeing with the statements about climate and sustainable fashion | 1.0 | 3.8 | 1.0 | 4.0 | 9. | 4.4 | 9. | 4.1 |

| Predominance of green self-image (self-report) | 1.4 | 4.1 | 1.5 | 4.3 | 1.3 | 4.5 | 1.3 | 4.4 |

| Predominance of green self-image (based on actions) | 1.2 | 1.4 | 1.1 | 1.7 | 1.2 | 1.7 | 1.1 | 1.6 |

| Control (N=123) |

knowledge (N=169) | Alternative (N=149) |

social norms N= (234) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I feel like I know how to distinguish between green clothes and those that are not | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N |

| Yes | 26.8 | 33 | 24.9 | 42 | 32.2 | 48 | 27.4 | 64 |

| No | 35.0 | 43 | 30.8 | 52 | 28.2 | 42 | 41.9 | 98 |

| I'm not sure | 38.2 | 47 | 44.4 | 75 | 39.6 | 59 | 30.8 | 72 |

| Control (N=123) |

knowledge (N=169) | Alternative (N=149) |

social norms N= (234) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I came across many green clothes today | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N |

| Yes | 18.7 | 23 | 7.1 | 12 | 28.2 | 42 | 15.0 | 35 |

| No | 44.7 | 55 | 59.2 | 100 | 38.9 | 58 | 54.7 | 128 |

| I'm not sure | 36.6 | 45 | 33.7 | 57 | 32.9 | 49 | 30.3 | 71 |

| Control (N=123) |

knowledge (N=169) | Alternative (N=149) |

social norms N= (234) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I believe that the clothes I bought today are green products | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N |

| Yes | 15.4 | 19 | 8.3 | 14 | 23.5 | 35 | 17.5 | 41 |

| No | 43.1 | 53 | 50.9 | 86 | 40.9 | 61 | 50.4 | 118 |

| I'm not sure | 41.5 | 51 | 40.8 | 69 | 35.6 | 53 | 32.1 | 75 |

| Women (N=451) |

Men (N=222) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SD | M | SD | M | |

| Amount purchased | 241.0 | 132.4 | 249.2 | 143.9 |

| Number of items bought | 2.2 | 1.4 | 2.4 | 1.8 |

| Average amount per item | 92.5 | 53.4 | 124.2 | 56.4 |

| Agreed with statements on climate and sustainable fashion | .9 | 4.2 | 1.0 | 3.9 |

| Predominance green self-image (self-reporting) | 1.3 | 4.5 | 1.5 | 4.1 |

| Predominance green self-image dominance (based on actions) | 1.1 | 1.7 | 1.2 | 1.3 |

| Women (N=451) |

Men (N=222) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | N | % | N | |

| I feel like I know how to distinguish between green clothes and those that are not | ||||

| Yes | 29.7 | 134 | 23.4 | 52 |

| No | 29.3 | 132 | 46.4 | 103 |

| I’m not sure | 41.0 | 185 | 30.2 | 67 |

| I came across many green clothes today | ||||

| Yes | 18.4 | 83 | 12.6 | 28 |

| No | 49.9 | 225 | 51.8 | 115 |

| I’m not sure | 31.7 | 143 | 35.6 | 79 |

| I believe that the clothes I bought today are green products | ||||

| Yes | 17.5 | 79 | 13.5 | 30 |

| No | 46.8 | 211 | 47.3 | 105 |

| I’m not sure | 35.7 | 161 | 39.2 | 87 |

| 31-45 (N=158) |

21-30 (N=150) |

16-20 (N=199) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I feel like I know how to distinguish between green clothes and those that are not | % | N | % | N | % | N |

| Yes | 20.9 | 33 | 24.7 | 37 | 25.1 | 50 |

| No | 39.2 | 62 | 40.0 | 60 | 35.7 | 71 |

| I'm not sure | 39.9 | 63 | 35.3 | 53 | 39.2 | 78 |

| I came across many green clothes today | ||||||

| Yes | 13.9 | 22 | 18.0 | 27 | 15.6 | 31 |

| No | 51.3 | 81 | 47.3 | 71 | 49.2 | 98 |

| I'm not sure | 34.8 | 55 | 34.7 | 52 | 35.2 | 70 |

| I believe that the clothes I bought today are green products | ||||||

| Yes | 11.4 | 18 | 12.7 | 19 | 22.6 | 45 |

| No | 48.7 | 77 | 44.7 | 67 | 43.2 | 86 |

| I’m not sure | 39.9 | 63 | 42.7 | 64 | 34.2 | 68 |

|

76 and above (N=19) |

61-75 (N=47) |

46-60 (N=98) |

||||

| I feel like I know how to distinguish between green clothes and those that are not | % | N | % | N | % | N |

| Yes | 52.6 | 10 | 51.1 | 24 | 30.6 | 30 |

| No | 21.1 | 4 | 25.5 | 12 | 26.5 | 26 |

| I'm not sure | 26.3 | 5 | 23.4 | 11 | 42.9 | 42 |

| I came across many green clothes today | ||||||

| Yes | 21.1 | 4 | 27.7 | 13 | 13.3 | 13 |

| No | 52.6 | 10 | 51.1 | 24 | 56.1 | 55 |

| I'm not sure | 26.3 | 5 | 21.3 | 10 | 30.6 | 30 |

| I believe that the clothes I bought today are green products | ||||||

| Yes | 26.3 | 5 | 21.3 | 10 | 12.2 | 12 |

| No | 57.9 | 11 | 53.2 | 25 | 50.0 | 49 |

| I'm not sure | 15.8 | 3 | 25.5 | 12 | 37.8 | 37 |

| B | SEB | B | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Green self-image dominance (self-report) | .47 | .02 | ***32. |

| Green self-image dominance (number of actions) | .13 | .03 | ***11. |

| Green self-image based on a number of actions | Green self-image based on self-report | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I feel like I know how to distinguish between green clothes and those that are not | M | SD | M | SD |

| Yes | 1.85 | 1.25 | 5.06 | 1.15 |

| No | 1.27 | 1.05 | 3.74 | 1.42 |

| I encountered many green clothes today | ||||

| Yes | 1.93 | 1.26 | 4.87 | 1.33 |

| No | 1.56 | 1.14 | 4.25 | 1.43 |

| I believe that the clothes I bought today are green products | ||||

| Yes | 1.86 | 1.17 | 4.96 | 1.14 |

| No | 1.51 | 1.14 | 4.16 | 1.51 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).