Submitted:

28 June 2024

Posted:

01 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation and Use of Minimal Culture Medium for Lanthanides

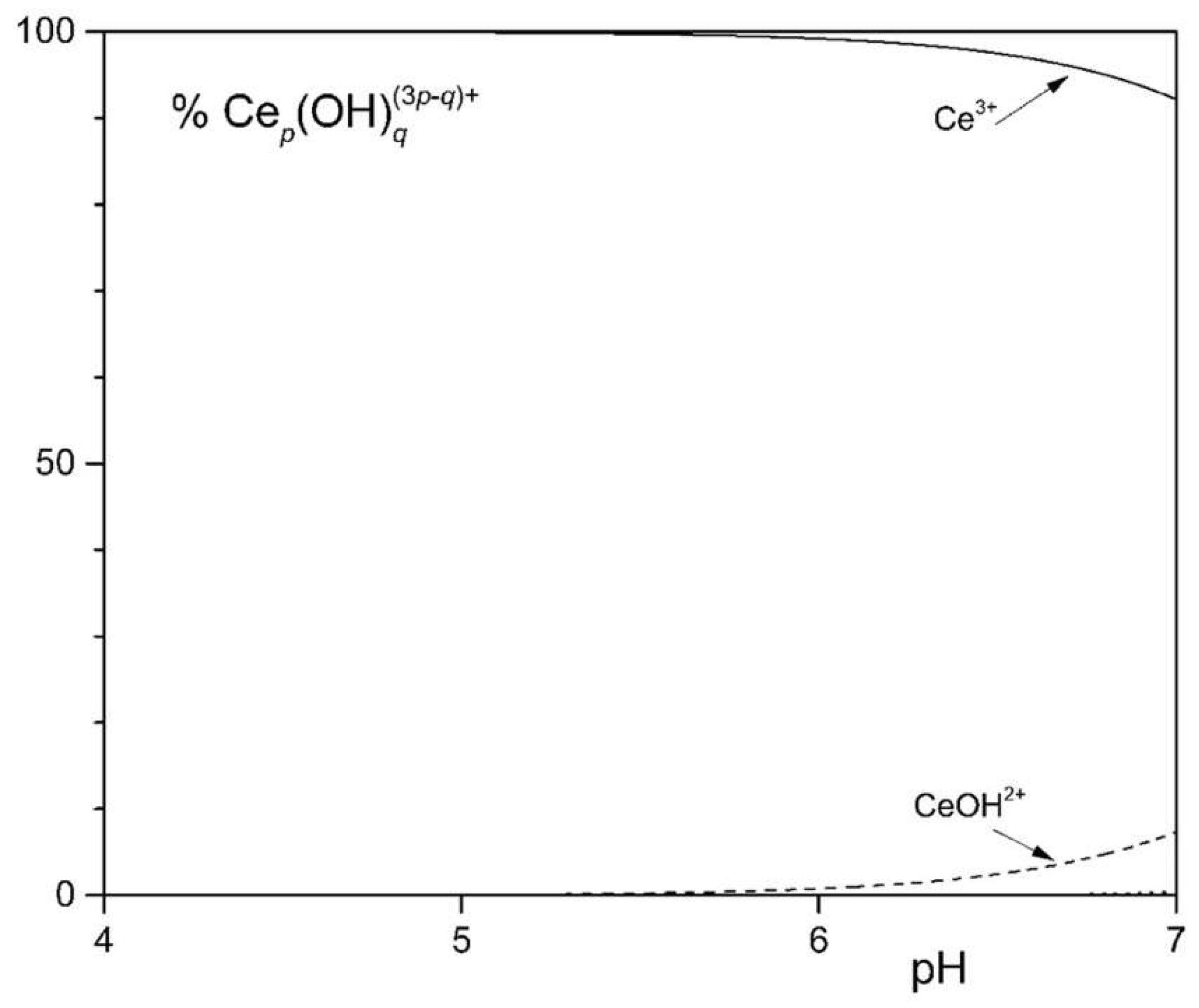

2.2. Complexation Equilibria Model

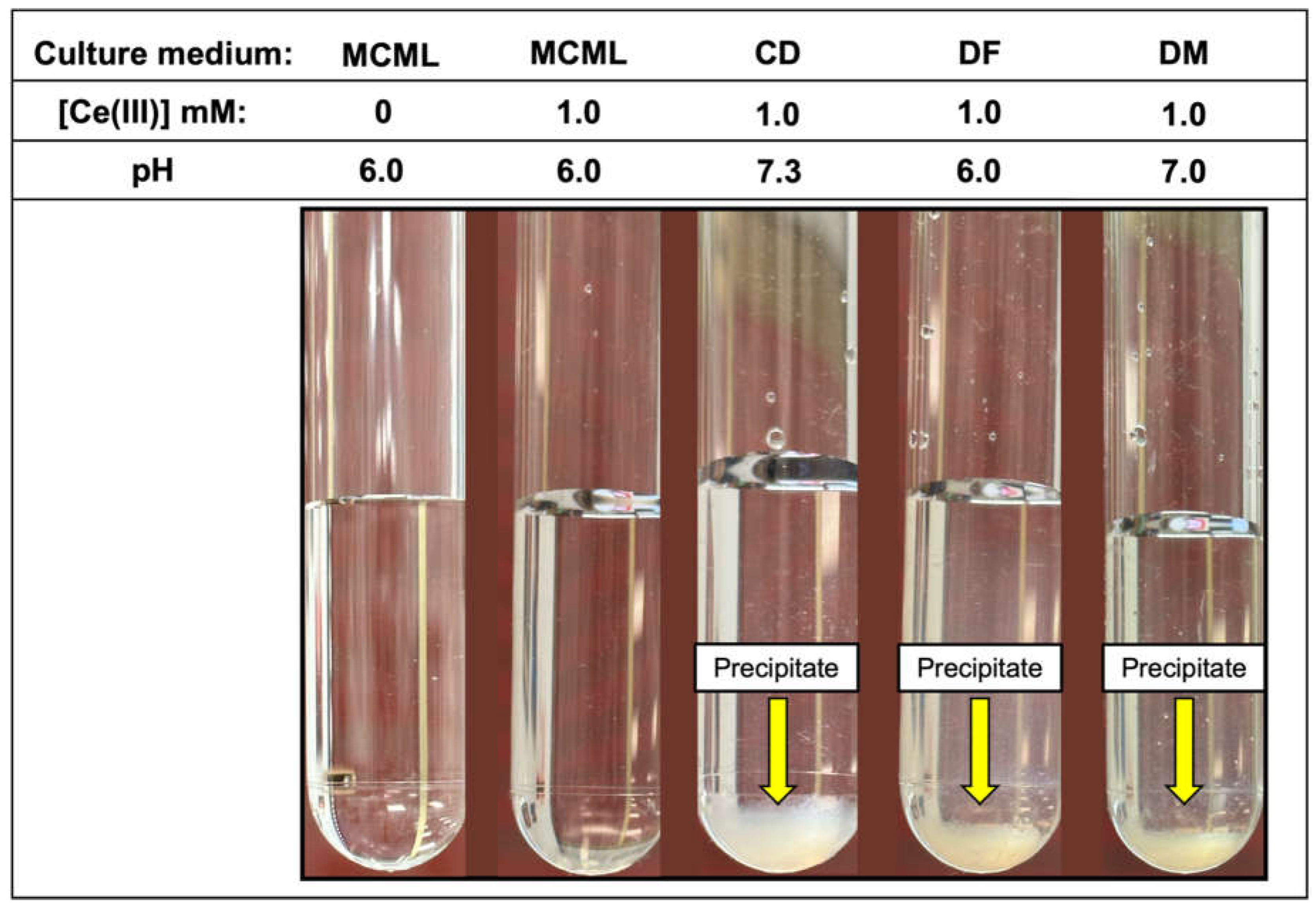

2.3. Solubility Test

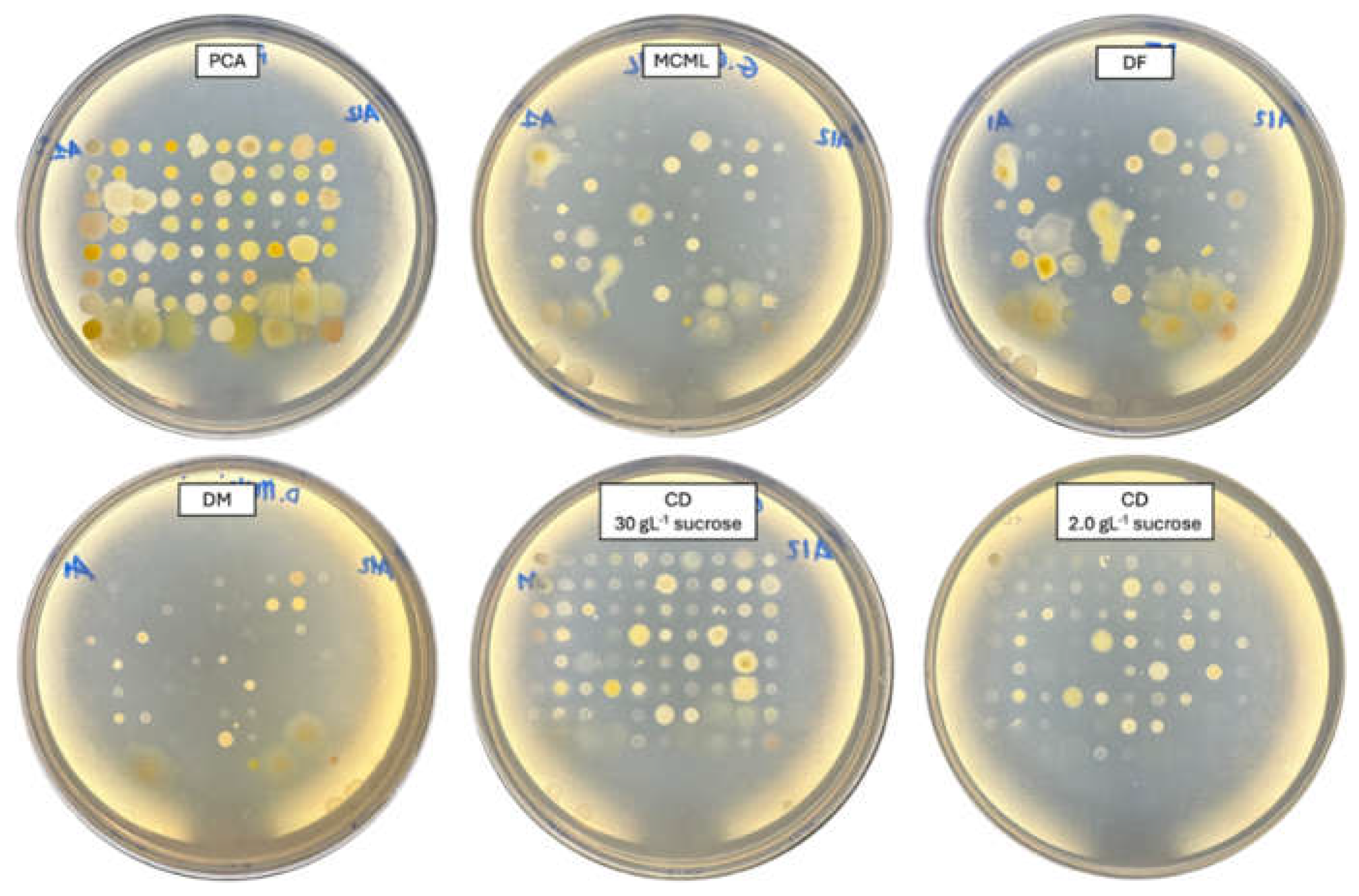

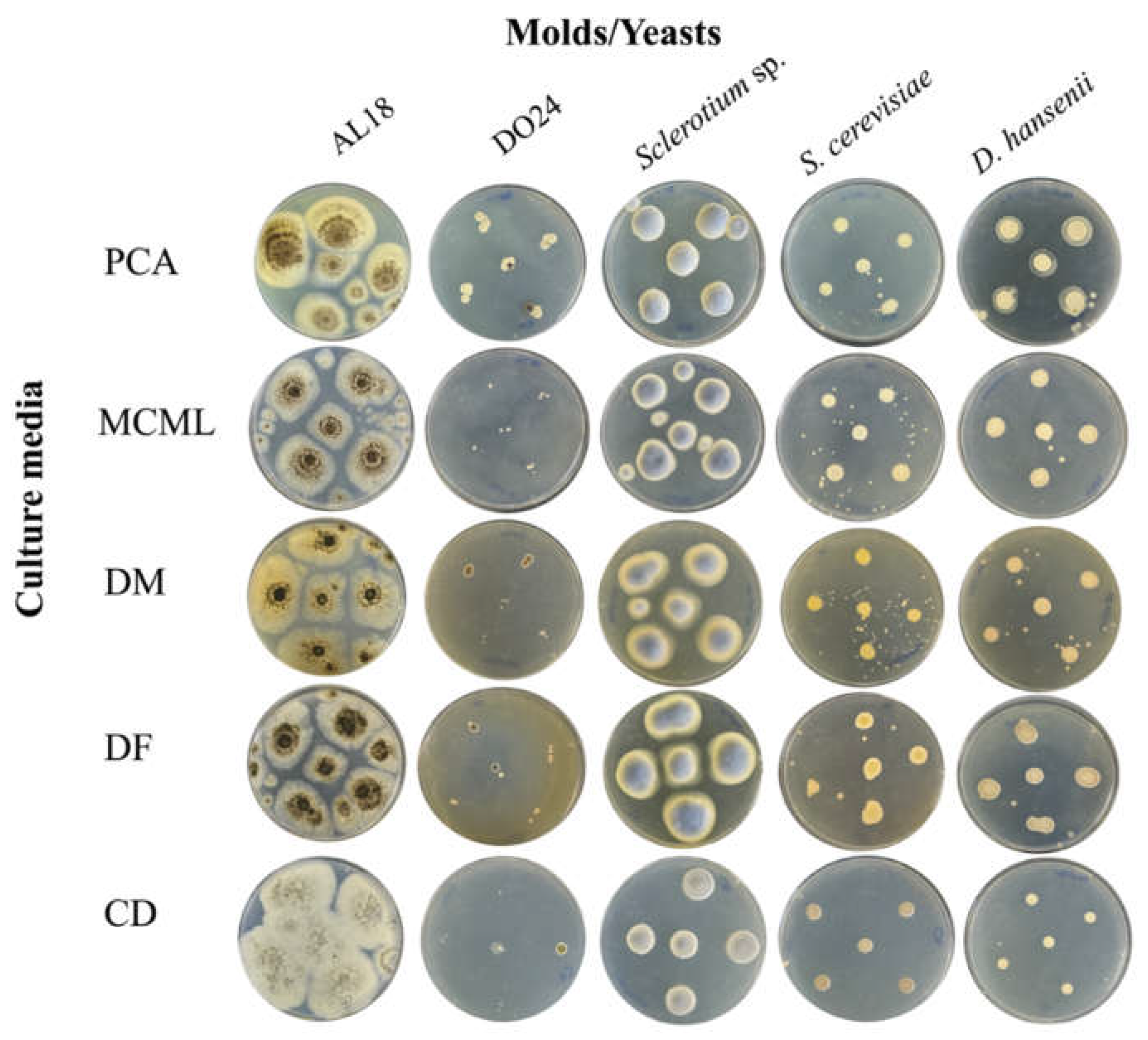

2.4. MCML Potentiality for the Cultivation of Different Microorganisms

2.5. Determination and Comparison of Growth Parameters

2.6. Evaluation of Ln3+ Toxicity and Accumulation

3. Results

3.1. Solubility in MCML

3.2. Formation of Ce Complexes

3.3. Solubility of Trivalent Lanthanides in Different Culture Media

3.4. Evaluation of MCML Suitability for Microorganism Growth

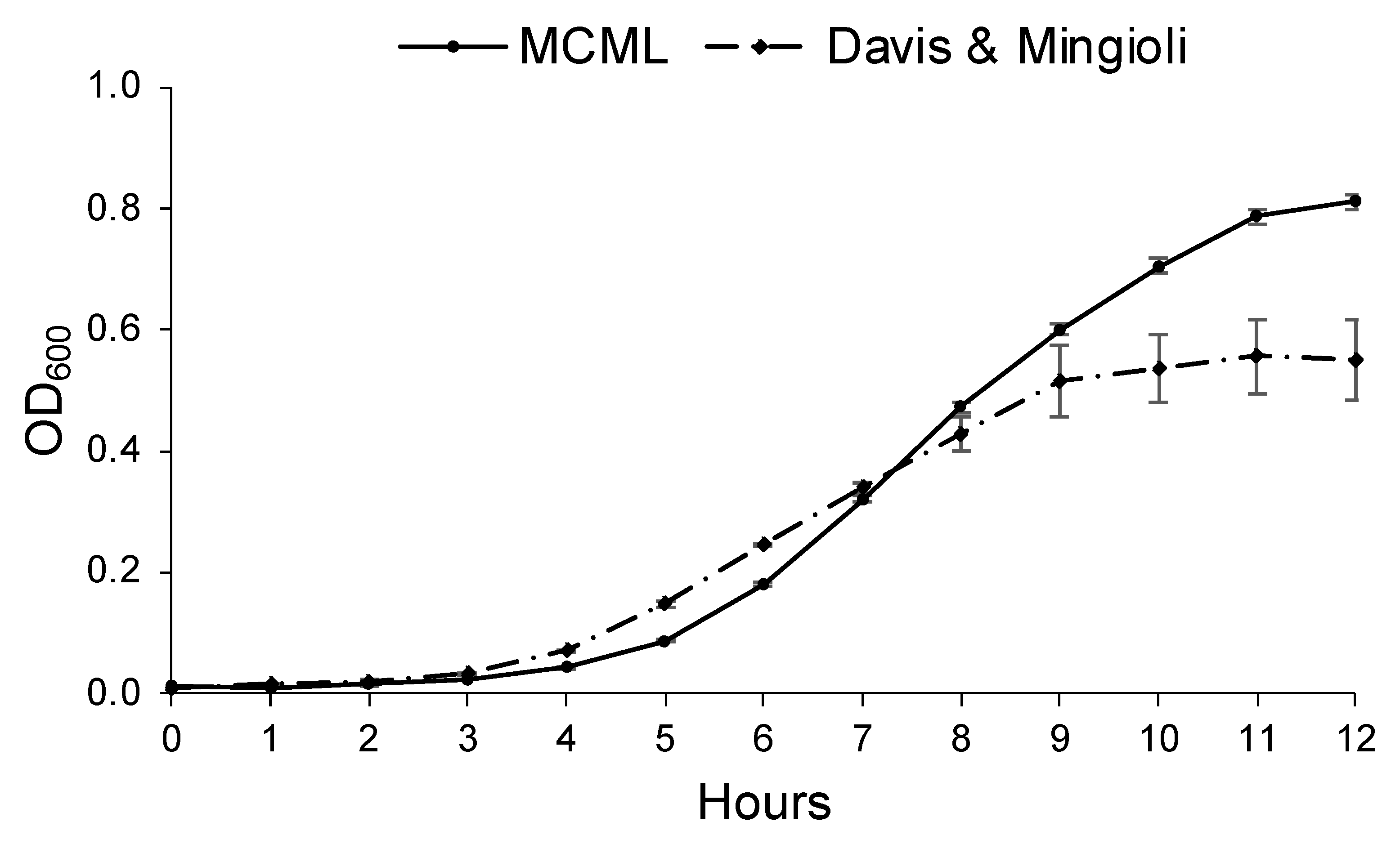

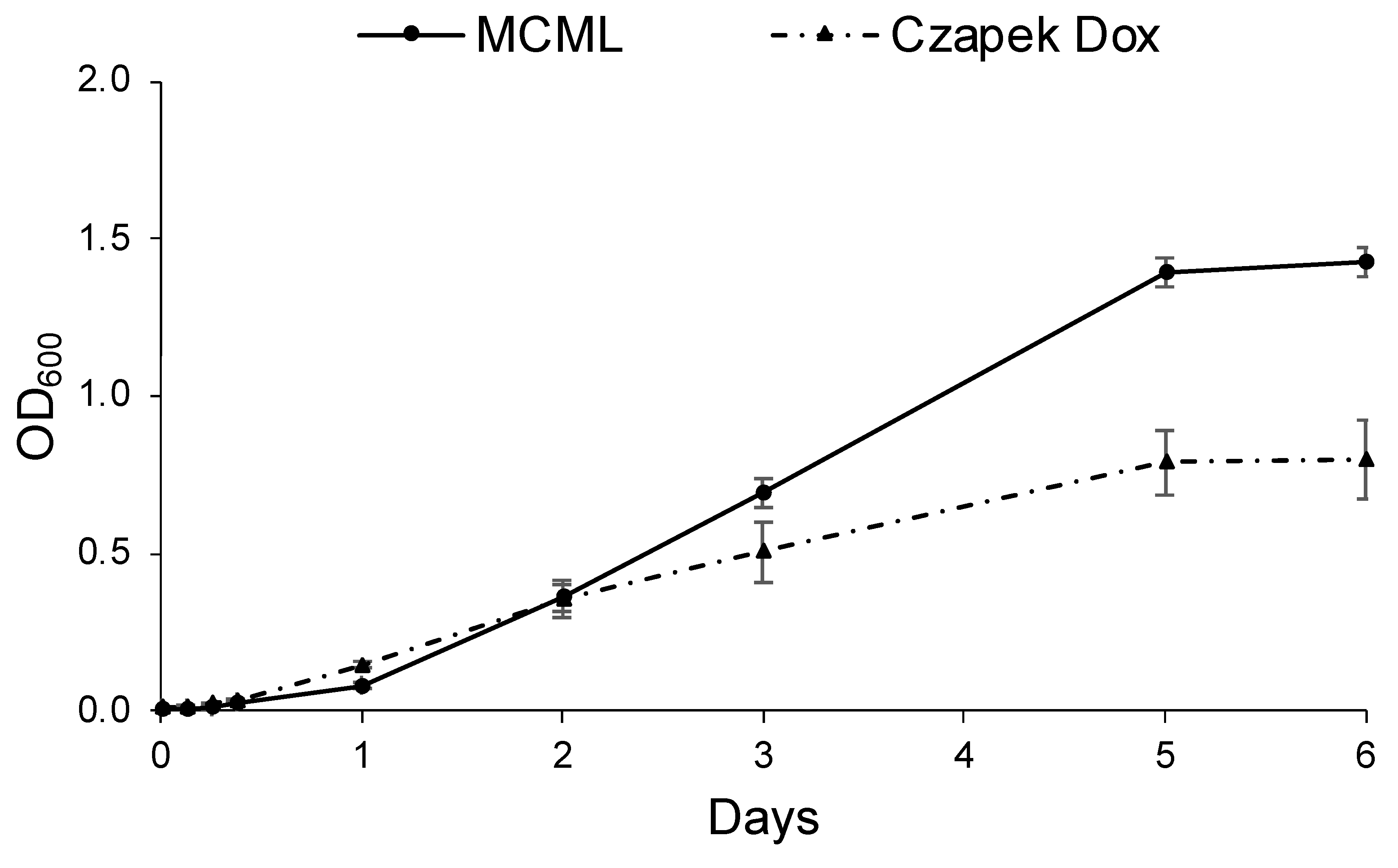

3.5. Evaluation of MCML Medium Growth Parameters

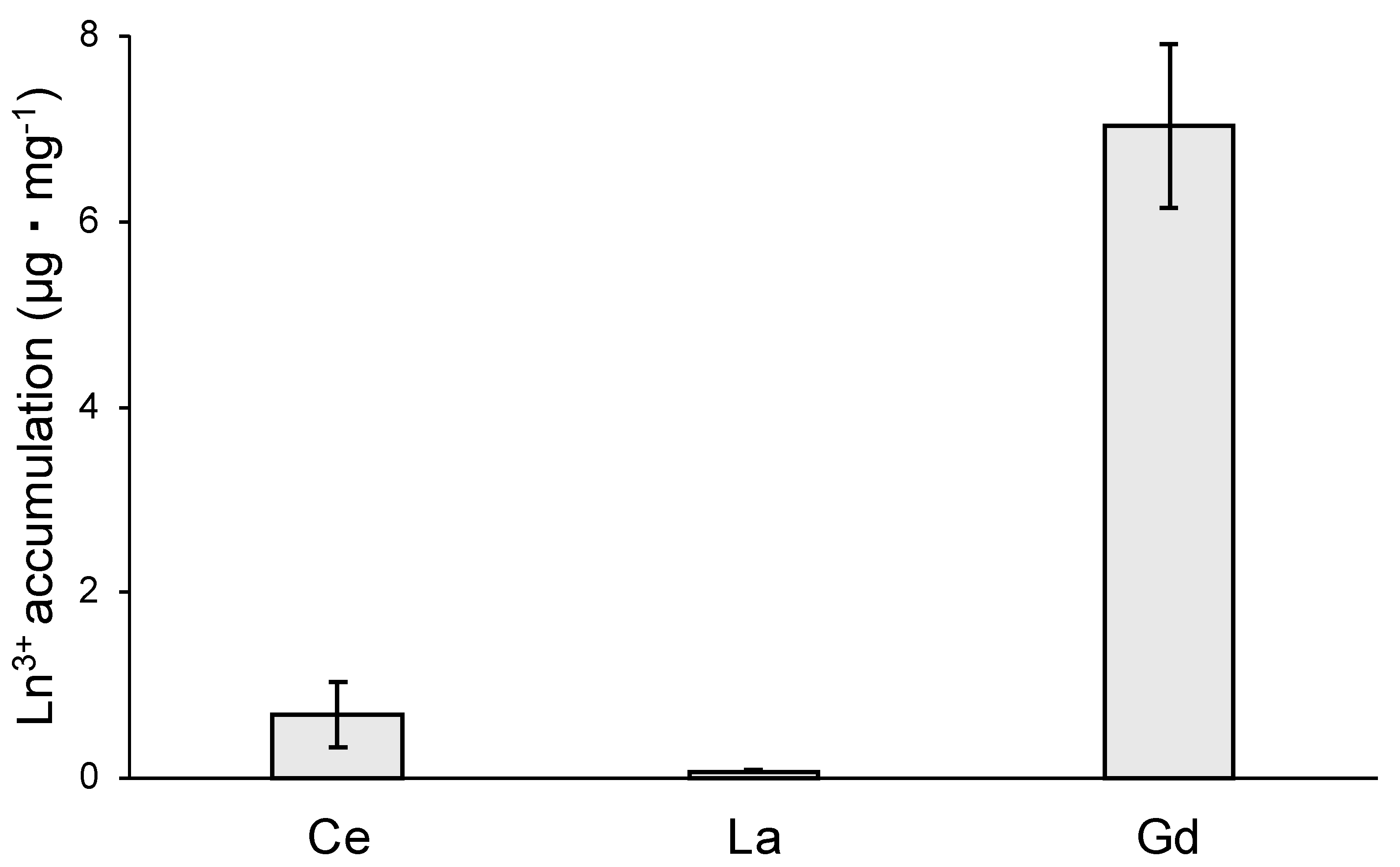

3.6. Ln3+ Toxicity and Accumulation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gompa, T.P.; Ramanathan, A.; Rice, N.T.; La Pierre, H.S. The Chemical and Physical Properties of Tetravalent Lanthanides: Pr, Nd, Tb, and Dy. Dalton Transactions 2020, 49, 15945–15987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tessitore, G.; Mandl, G.A.; Maurizio, S.L.; Kaur, M.; Capobianco, J.A. The Role of Lanthanide Luminescence in Advancing Technology. RSC Advances 2023, 13, 17787–17811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armelao, L.; Quici, S.; Barigelletti, F.; Accorsi, G.; Bottaro, G.; Cavazzini, M.; Tondello, E. Design of Luminescent Lanthanide Complexes: From Molecules to Highly Efficient Photo-Emitting Materials. Coordination Chemistry Reviews 2010, 254, 487–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Kumar, A.; Oberoi, D.; Ghosh, S.; Majhi, J.; Priya, K.; Bandyopadhyay, A. A Review on Diverse Applications of Electrochemically Active Functional Metallopolymers. Reactive and Functional Polymers 2023, 193, 105742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viana, L.N.; Soares, A.P.S.; Guimarães, D.L.; Rojano, W.J.S.; Saint’Pierre, T.D. Fluorescent Lamps: A Review on Environmental Concerns and Current Recycling Perspectives Highlighting Hg and Rare Earth Elements. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2022, 10, 108915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Chan, W.K.; Tan, T.T.Y. Neodymium-Sensitized Nanoconstructs for Near-Infrared Enabled Photomedicine. Small 2020, 16, 1905265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagheri, S.; Khalil, I.; Julkapli, N.M. Cerium(IV) Oxide Nanocomposites: Catalytic Properties and Industrial Application. Journal of Rare Earths 2021, 39, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.K.; Ahmed, M.H.; Khan, M.I.; Miah, M.S.; Hossain, S. Recent Progress of Rare Earth Oxides for Sensor, Detector, and Electronic Device Applications: A Review. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2021, 3, 4255–4283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Liu, J.; Huang, D.; Zhou, W.; Liu, C.; Cao, Y.; Cao, C. Sources of Rare Earth Elements REE+Y (REY) in Bayili Coal Mine from Wensu County of Xinjiang, China. Transactions of Nonferrous Metals Society of China 2021, 31, 3105–3115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, D.H.; Thompson, K.A.; Ma, L.; Nguyen, H.Q.; Luu, S.T.; Duong, M.T.N.; Kernaghan, A. Toward the Circular Economy of Rare Earth Elements: A Review of Abundance, Extraction, Applications, and Environmental Impacts. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol 2021, 81, 521–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opare, E.O.; Struhs, E.; Mirkouei, A. A Comparative State-of-Technology Review and Future Directions for Rare Earth Element Separation. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2021, 143, 110917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, P.H.N.; Danaee, S.; Hai, H.T.N.; Huy, L.N.; Nguyen, T.A.H.; Nguyen, H.T.M.; Kuzhiumparambil, U.; Kim, M.; Nghiem, L.D.; Ralph, P.J. Biomining for Sustainable Recovery of Rare Earth Elements from Mining Waste: A Comprehensive Review. Science of The Total Environment 2024, 908, 168210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Čížková, M.; Mezricky, P.; Mezricky, D.; Rucki, M.; Zachleder, V.; Vítová, M. Bioaccumulation of Rare Earth Elements from Waste Luminophores in the Red Algae, Galdieria Phlegrea. Waste Biomass Valor 2021, 12, 3137–3146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotelnikova, A.D.; Rogova, O.B.; Stolbova, V.V. Lanthanides in the Soil: Routes of Entry, Content, Effect on Plants, and Genotoxicity (a Review). Eurasian Soil Sc. 2021, 54, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Gao, Z. Effects of Lanthanum on Growth and Accumulation in Roots of Rice Seedlings. Plant Soil Environ. 2013, 59, 196–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, M.H.; Alamri, S.; Alsubaie, Q.D.; Ali, H.M.; Ibrahim, A.A.; Alsadon, A. Potential Roles of Melatonin and Sulfur in Alleviation of Lanthanum Toxicity in Tomato Seedlings. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2019, 180, 656–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malhotra, N.; Hsu, H.-S.; Liang, S.-T.; Roldan, M.J.M.; Lee, J.-S.; Ger, T.-R.; Hsiao, C.-D. An Updated Review of Toxicity Effect of the Rare Earth Elements (REEs) on Aquatic Organisms. Animals 2020, 10, 1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brouziotis, A.A.; Giarra, A.; Libralato, G.; Pagano, G.; Guida, M.; Trifuoggi, M. Toxicity of Rare Earth Elements: An Overview on Human Health Impact. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, R.A.; Alexandrov, K.; Scott, C. Rare Earth Elements in Biology: From Biochemical Curiosity to Solutions for Extractive Industries. Microbial Biotechnology 2024, 17, e14503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Featherston, E.R.; Cotruvo, J.A. The Biochemistry of Lanthanide Acquisition, Trafficking, and Utilization. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research 2021, 1868, 118864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keltjens, J.T.; Pol, A.; Reimann, J.; Op den Camp, H.J.M. PQQ-Dependent Methanol Dehydrogenases: Rare-Earth Elements Make a Difference. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2014, 98, 6163–6183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, S.; Takashino, M.; Igarashi, K.; Kitagawa, W. Isolation and Genomic Characterization of a Proteobacterial Methanotroph Requiring Lanthanides. Microbes and Environments 2020, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cotruvo, J.A.Jr.; Featherston, E.R.; Mattocks, J.A.; Ho, J.V.; Laremore, T.N. Lanmodulin: A Highly Selective Lanthanide-Binding Protein from a Lanthanide-Utilizing Bacterium. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 15056–15061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemmann, J.L.; Keller, P.; Hemmerle, L.; Vonderach, T.; Ochsner, A.M.; Bortfeld-Miller, M.; Günther, D.; Vorholt, J.A. Lanpepsy Is a Novel Lanthanide-Binding Protein Involved in the Lanthanide Response of the Obligate Methylotroph Methylobacillus Flagellatus. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2023, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassas, B.V.; Rezaee, M.; Pisupati, S.V. Effect of Various Ligands on the Selective Precipitation of Critical and Rare Earth Elements from Acid Mine Drainage. Chemosphere 2021, 280, 130684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heller, A.; Pisarevskaja, A.; Bölicke, N.; Barkleit, A.; Bok, F.; Wober, J. The Effect of Four Lanthanides onto a Rat Kidney Cell Line (NRK-52E) Is Dependent on the Composition of the Cell Culture Medium. Toxicology 2021, 456, 152771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, A.; Bhattacharjee, S.; Saha, J.; Sarkar, M.; Mandal, P. Bacterial Survival Strategies and Responses under Heavy Metal Stress: A Comprehensive Overview. Critical Reviews in Microbiology 2022, 48, 327–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lund, P.A.; De Biase, D.; Liran, O.; Scheler, O.; Mira, N.P.; Cetecioglu, Z.; Fernández, E.N.; Bover-Cid, S.; Hall, R.; Sauer, M.; et al. Understanding How Microorganisms Respond to Acid pH Is Central to Their Control and Successful Exploitation. Frontiers in Microbiology 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barker, E.; Shepherd, J.; Asencio, I.O. The Use of Cerium Compounds as Antimicrobials for Biomedical Applications. Molecules 2022, 27, 2678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polido Legaria, E.; Samouhos, M.; Kessler, V.G.; Seisenbaeva, G.A. Toward Molecular Recognition of REEs: Comparative Analysis of Hybrid Nanoadsorbents with the Different Complexonate Ligands EDTA, DTPA, and TTHA. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 56, 13938–13948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finnegan, S.; Percival, S.L. EDTA: An Antimicrobial and Antibiofilm Agent for Use in Wound Care. Advances in Wound Care 2015, 4, 415–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, N.; Rathore, S.; Patoli, B.B.; Patoli, A.A. Bacterial Biofilms and Ethylenediamine-N,N’-Disuccinic Acid (EDDS) as Potential Biofilm Inhibitory Compound: EDDS as Biofilm Inhibitory Compound. Proceedings of the Pakistan Academy of Sciences: B. Life and Environmental Sciences 2020, 57, 85–92. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, B.; Kläger, W.; Kubitzki, G. Metal Chelates of Citric Acid as Corrosion Inhibitors for Zinc Pigment. Corrosion Science 1997, 39, 1481–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braissant, O.; Verrecchia, E.P.; Aragno, M. Is the Contribution of Bacteria to Terrestrial Carbon Budget Greatly Underestimated? Naturwissenschaften 2002, 89, 366–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellino, L.; Alladio, E.; Bertinetti, S.; Lando, G.; De Stefano, C.; Blasco, S.; García-España, E.; Gama, S.; Berto, S.; Milea, D. PyES – An Open-Source Software for the Computation of Solution and Precipitation Equilibria. Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory Systems 2023, 239, 104860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, B.D.; Mingioli, E.S. MUTANTS OF ESCHERICHIA COLI REQUIRING METHIONINE OR VITAMIN B 12. J Bacteriol 1950, 60, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dworkin, M.; Foster, J.W. EXPERIMENTS WITH SOME MICROORGANISMS WHICH UTILIZE ETHANE AND HYDROGEN. J Bacteriol 1958, 75, 592–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, G. The Effect of Adding Trace Elements to Czapek-Dox Medium. Transactions of the British Mycological Society 1949, 32, 280–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigliotta, G.; Giordano, D.; Verdino, A.; Caputo, I.; Martucciello, S.; Soriente, A.; Marabotti, A.; De Rosa, M. New Compounds for a Good Old Class: Synthesis of Two Β-Lactam Bearing Cephalosporins and Their Evaluation with a Multidisciplinary Approach. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry 2020, 28, 115302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigliotta, G.; Di Giacomo, M.; Carata, E.; Massardo, D.R.; Tredici, S.M.; Silvestro, D.; Paolino, M.; Pontieri, P.; Del Giudice, L.; Parente, D.; et al. Nitrite Metabolism in Debaryomyces Hansenii TOB-Y7, a Yeast Strain Involved in Tobacco Fermentation. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2007, 75, 633–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castiglione, S.; Oliva, G.; Vigliotta, G.; Novello, G.; Gamalero, E.; Lingua, G.; Cicatelli, A.; Guarino, F. Effects of Compost Amendment on Glycophyte and Halophyte Crops Grown on Saline Soils: Isolation and Characterization of Rhizobacteria with Plant Growth Promoting Features and High Salt Resistance. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva, G.; Vigliotta, G.; Terzaghi, M.; Guarino, F.; Cicatelli, A.; Montagnoli, A.; Castiglione, S. Counteracting Action of Bacillus Stratosphericus and Staphylococcus Succinus Strains against Deleterious Salt Effects on Zea Mays L. Frontiers in Microbiology 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, C.T.; Ratledge, C. A Comparison of the Oleaginous Yeast,Candida Curvata, Grown on Different Carbon Sources in Continuous and Batch Culture. Lipids 1983, 18, 623–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Souza, S.S.; Berti, F.V.; de Oliveira, K.P.V.; Pittella, C.Q.P.; de Castro, J.V.; Pelissari, C.; Rambo, C.R.; Porto, L.M. Nanocellulose Biosynthesis by Komagataeibacter Hansenii in a Defined Minimal Culture Medium. Cellulose 2019, 26, 1641–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ansari, M.; Kalaiyarasi, M.; Almalki, M.A.; Vijayaraghavan, P. Optimization of Medium Components for the Production of Antimicrobial and Anticancer Secondary Metabolites from Streptomyces Sp. AS11 Isolated from the Marine Environment. Journal of King Saud University - Science 2020, 32, 1993–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, L.; Blázquez, M.L.; González, F.; Muñoz, J.A. Bioleaching of Phosphate Minerals Using Aspergillus Niger: Recovery of Copper and Rare Earth Elements. Metals 2020, 10, 978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoulnia, P.; Barthen, R.; Lakaniemi, A.-M.; Ali-Löytty, H.; Puhakka, J.A. Low Residual Dissolved Phosphate in Spent Medium Bioleaching Enables Rapid and Enhanced Solubilization of Rare Earth Elements from End-of-Life NiMH Batteries. Minerals Engineering 2022, 176, 107361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groom, J.D.; Lidstrom, M.E. Cultivation Techniques to Study Lanthanide Metal Interactions in the Haloalkaliphilic Type I Methanotroph “Methylotuvimicrobium Buryatense” 5GB1C. In Methods in Enzymology; Cotruvo, J.A., Ed.; Rare-Earth Element Biochemistry: Methanol Dehydrogenases and Lanthanide Biology; Academic Press, 2021; Vol. 650, pp. 237–259.

- Kaiser, C.; Michaelis, S.; Mitchell, A. Methods in Yeast Genetics: A Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Course Manual, 1994 ed.; Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press: Cold Spring Harbor, NY, 1994; ISBN 978-0-87969-451-7. [Google Scholar]

- Ene, C.D.; Ruta, L.L.; Nicolau, I.; Popa, C.V.; Iordache, V.; Neagoe, A.D.; Farcasanu, I.C. Interaction between Lanthanide Ions and Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Cells. J Biol Inorg Chem 2015, 20, 1097–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breuker, A.; Ritter, S.F.; Schippers, A. Biosorption of Rare Earth Elements by Different Microorganisms in Acidic Solutions. Metals 2020, 10, 954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazak, E.S.; Lebedeva, E.G.; Kharitonova, N.A.; Chelnokov, G.A.; Elovsky, E.V. Fractionation of Rare Earth Elements and Yttrium in Aqueous Media: The Role of Organotrophic Bacteria. Moscow Univ. Geol. Bull. 2021, 76, 445–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, Z.; Pang, S.; Jiang, B.; Yang, Y.; Duan, Q.; Zhu, G. The Impact of Cell Structure, Metabolism and Group Behavior for the Survival of Bacteria under Stress Conditions. Arch Microbiol 2021, 203, 431–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suryadevara, B. Advances in Chemical Mechanical Planarization (CMP); Woodhead Publishing, 2016; ISBN 978-0-08-100218-6.

- Sigala-Valdez, J.O.; Ramirez-Ezquivel, O.Y.; Castañeda-Miranda, C.L.; Moreno-García, H.; García-Rocha, R.; Escalante-García, I.L.; Del Rio-De Santiago, A. Effect of the Tri-Sodium Citrate as a Complexing Agent in the Deposition of ZnS by SILAR. Heliyon 2023, 9, e17971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughn, R.H.; Osborne, J.T.; Wedding, G.T.; Tabachnick, J.; Beisel, C.G.; Braxton, T. THE UTILIZATION OF CITRATE BY ESCHERICHIA COLI. J Bacteriol 1950, 60, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Lu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Yu, L.; Jia, X.; Wong, P.K.; Qiu, R. Kinetics, Pathways and Toxicity of Hexabromocyclododecane Biodegradation: Isolation of the Novel Bacterium Citrobacter Sp. Y3. Chemosphere 2021, 274, 129929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaoka, S.; Murata, S.; Kimura, K.; Mori, T.; Hojo, K. Antimicrobial Activity of Sodium Citrate against Streptococcus Pneumoniae and Several Oral Bacteria. Letters in Applied Microbiology 2010, 51, 546–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Cesario, T.; Owens, J.; Shanbrom, E.; Thrupp, L.D. Antibacterial Activity of Citrate and Acetate. Nutrition 2002, 18, 665–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.; Mao, Y.; Jin, B.; Guo, Y.; Wang, Z.; Chen, T. Substrate Profiling and Tolerance Testing of Halomonas TD01 Suggest Its Potential Application in Sustainable Manufacturing of Chemicals. Journal of Biotechnology 2020, 316, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Porro, C.; Kaur, B.; Mann, H.; Ventosa, A. Halomonas Titanicae Sp. Nov., a Halophilic Bacterium Isolated from the RMS Titanic. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology 2010, 60, 2768–2774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wakabayashi, T.; Ymamoto, A.; Kazaana, A.; Nakano, Y.; Nojiri, Y.; Kashiwazaki, M. Antibacterial, Antifungal and Nematicidal Activities of Rare Earth Ions. Biol Trace Elem Res 2016, 174, 464–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anil, A.; Sanjeev, K.G.; Kamarudheen, N.; Sebastian, P.M.; Rao, K.V.B. EPS-Mediated Biosynthesis of Nanoparticles by Bacillus Stratosphericus A07, Their Characterization and Potential Application in Azo Dye Degradation. Arch Microbiol 2023, 205, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Components | Concentration in medium [g L-1] | |||

| MCML | DM | CD | DF | |

| (NH4)2SO4 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 2.0* | 2.0 |

| MgSO4·7H2O | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.2 |

| KH2PO4 | 0.4 | 3.0 | - | 4.0 |

| K2HPO4 | - | 7.0 | 1.0 | - |

| Na2HPO4 | - | - | - | 6.0 |

| KCl | - | - | 0.5 | - |

| Na3citOH·2H2O | 10.02 | 0.5 | - | - |

| H3citOH | 0.94 | - | - | 2.0 |

| Gluconic acid | - | - | - | 2.0 |

| FeSO4·7H2O | 0.0001 | - | 0.01 | 0.0001 |

| D-Glucose | 2.0 | 2.0 | - | 2.0 |

| Sucrose | - | - | 30.0 | - |

| L-arginine | - | 0.02 | - | - |

| L-tryptophan | - | 0.02 | - | - |

| Micronutrients | 100 µL** | - | - | 100 µL*** |

| pH | 6.0 | 7.0 | 7.3 | 6.0 |

| pH | |||||||

| mM | 2.0 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 5.0 | 6.0 | 7.0 | 8.0 |

| 0.01 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 0.05 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 0.1 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 0.5 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 1.0 | + | + | + | + | + | + | - |

| 2.0 | + | + | + | + | - | - | - |

| 3.0 | + | + | + | - | - | - | - |

| 5.0 | + | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Culture medium | pH | La3+ | Ce3+ | Gd3+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MCML | 6.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 5.0 |

| Dworkin & Foster | 6.0 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.05 |

| Davis & Mingioli | 7.0 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.05 |

| Czapek Dox | 7.3 | - | - | - |

| Ln3+ (mM) | Colony numbers in the follow Ln3+ treatments | ||

| Ce3+ | La3+ | Gd3+ | |

| 0 (Control) | 166 ⋅ 105 | 166 ⋅ 105 | 166 ⋅ 105 |

| 5 | 121 ⋅ 105 | 900 ⋅ 104 | ND |

| 10 | 48 ⋅ 105 | 147 ⋅ 104 | 54 ⋅ 104 |

| 20 | ND | ND | - |

| Ln3+ (mM) | Colony diameter (mm) in the follow Ln3+ treatments | ||

| Ce3+ | La3+ | Gd3+ | |

| 0 (Control) | 2.14 ± 0.17 a | 2.17 ± 0.47 a | 2.05 ± 0.17 a |

| 5 | 0.89 ± 0.15 b | 0.87 ± 0.17 b | ND |

| 10 | 0.49 ± 0.08 c | 0.99 ± 0.12 b | 1.43 ± 0.22 b |

| 20 | ND | ND | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).