Submitted:

28 June 2024

Posted:

01 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

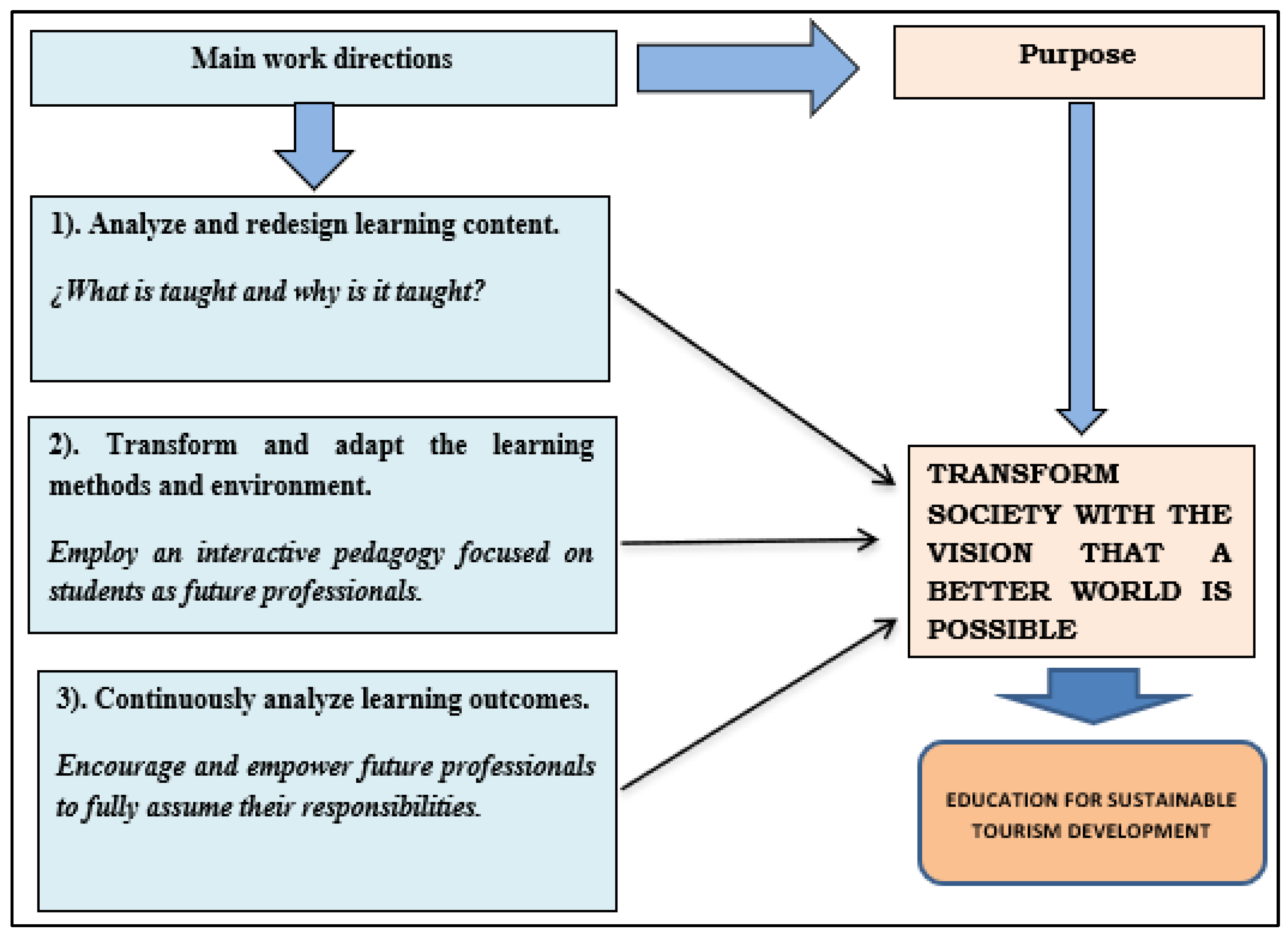

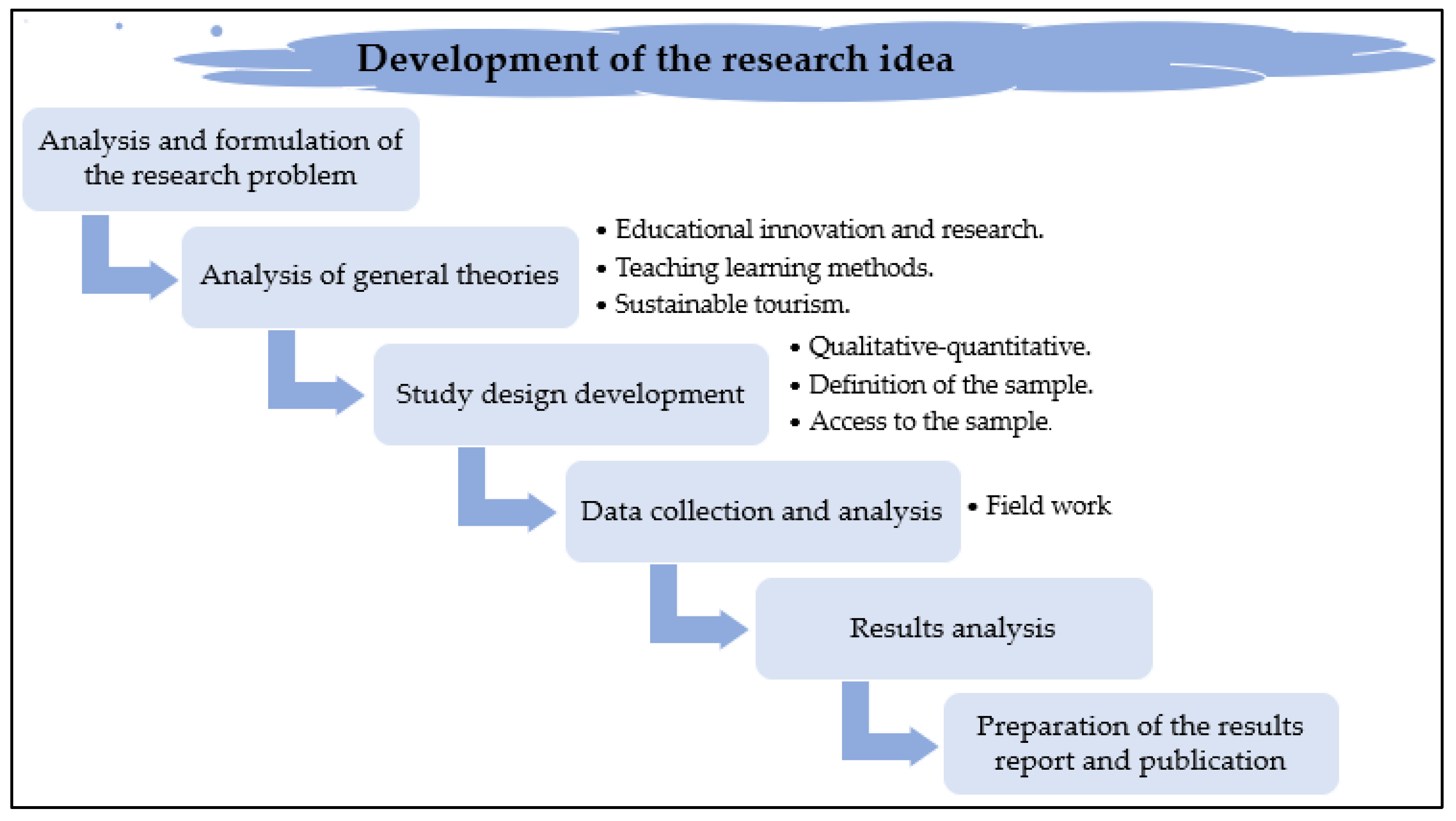

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Contextualization of the Research

2.2. Experiences Achieved in the Materialization of Teaching Innovation Methods

- Expository master classes that allow for the internalization of information and common teaching processes, which guarantee students’ knowledge of the necessary training, methodologies, and processes to know, apply, intervene, propose, and conclude direct interventions in their professional actions [73,74].

- Open, collaborative, and integrated teaching (collaborative teaching model) that, at professional and degree levels, allows the student and teacher to integrate with the knowledge society, with respect to not only the traditional methodologies that are applied but also those practiced in the various contexts of action through the use of the various media associated with the information society and globalization [79,80].

2.3. Research Method, Techniques, and Tools

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barrero-Barrero, David.; Fabio Baquero-Valdés. Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible: un contrato social posmoderno para la justicia, el desarrollo y la seguridad. Revista Científica General José María Córdova 18.29, 2020: 113-137. [CrossRef]

- Martínez, Juan Carlos Pila.; Wilson Gonzalo Andagoya Pazmiño.; María Elizabeth Fuertes Fuertes. El profesorado: Un factor clave en la innovación educativa. Revista EDUCARE-UPEL-IPB-Segunda Nueva Etapa 2.0 24.2, 2020: 212-232. [CrossRef]

- Céspedes, Lianet Goyas.; Georgina Marcia Soto Senra.; Liannet Sánchez Soto. La gestión de los procesos educativos universitarios enfocados a la educación ambiental. Magazine de las Ciencias: Revista de Investigación e Innovación 3.3, 2018: 89-102. https://revistas.utb.edu.ec/index.php/magazine/article/view/580. (Accessed on 16 February 2024).

- Gómez Ponce, Leonardo. El presupuesto de las universidades, ¿dinero bien gastado? Observatorio de gasto público de Ecuador. 2020. https://www.gastopublico.org/informes-del-observatorio/el-presupuesto-de-las-universidades-dinero-bien-gastado. (Accessed on 21 May 2024).

- ONU. Educación para el Desarrollo Sostenible. Hoja de Ruta. Repositorio UNESCO. Organización de las Naciones Unidas. 2020. http://es.unesco.org/open-access/terms-use-ccbysa-sp. (Accessed on 18 February 2024).

- Pinzón, Juan David. Educar para la sostenibilidad, como fomento de una cultura de desarrollo humano sostenible en el contexto rural. [Tesis doctorado]. Universidad Pedagógica Experimental Libertador. Venezuela. (2020). https://espacio.digital.upel.edu.ve/index.php/TD/article/view/896/750. (Accessed on 20 February 2024).

- Ciro Romero, Diana Libia. Evaluación de las intenciones ambientales de los estudiantes de la Universidad Nacional de Colombia-Sede Bogotá. [Tesis de maestría]. Universidad Nacional de Colombia. https://repositorio.unal.edu.co/handle/unal/80188. (Accessed on 10 February 2024).

- Delandshere, Ginette. From static and prescribed to dynamic and principled assessment of teaching. The Elementary School Journal 97.2, 1996: 105-120. https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/461857. (Accessed on 3 May 2024).

- Huckle, John. Education for sustainability: evaluating paths to the future. Australian Journal of Environmental Education 7, 1991: 43-62.

- Tilbury, Daniella. Environmental education for sustainability: Defining the new focus of environmental education in the 1990s. Environmental education research 1.2, 2006. [CrossRef]

- Calvo, Seoanez. El medio ambiente en la opinión pública: Tendencias de opinión. Demanda social. Análisis y gestión de la opinión pública en materia de medio ambiente. Comunicación medioambiental en la Administración y en la empresa. Ediciones Mundi-Prensa, 1997. https://books.google.es/books?hl=es&lr=&id=-Ab7syu2PRQC&oi=fnd&pg=PA31&dq=Calvo,+S.+(1997)&ots=Lu0E7ebDXT&sig=HIfUACspztsCbmX_t0U7UJ4eR70. (Accessed on 11 February 2024).

- Huckle, John.; Stephen R. Sterling. Education for sustainability. Earth exploration,1996. https://books.google.es/books?hl=es&lr=&id=dNsTFPRFAZ4C&oi=fnd&pg=PP9&dq=Sterling,+S.+(1996).+Good+Earth-keeping:+Education,+Training+%26+Awareness+for+the+Sustainable+Future,+Londres,+UNEP&ots=c7SjnqYUdx&sig=wz5zRQLDQCJbHcBb2fXKK9JVlbM. (Accessed on 20 February 2024).

- Palmer, Joy. Environmental education in the 21st century: Theory, practice, progress and promise. Routledge, 2002. https://api.taylorfrancis.com/content/books/mono/download?identifierName=doi&identifierValue=10.4324/9780203012659&type=googlepdf. (Accessed on 21 February 2024).

- McNaughton, Marie Jeanne. El drama educativo en la educación para el desarrollo sostenible: Ecopedagogía en acción. Pedagogía, Cultura y Sociedad 18.3, 2010: 289-308. [CrossRef]

- O’Flaherty, Joanne.; Mags Liddy. The impact of development education and education for sustainable development interventions: a synthesis of the research. Environmental education research 24.7, 2018: 1031-1049. [CrossRef]

- Boeve-de Pauw, Jelle.; Niklas Gericke.; Daniel Olson.; Teresa Berglund. The effectiveness of education for sustainable development. Sostenibilidad 2015, 7 (11), 15693-15717; [CrossRef]

- Valdiviezo, Wilfredo Alva. Ecoeficiencia: Nueva estrategia para la educación ambiental en instituciones educativas. Investigación Valdizana 13.2, 2019: 77-84. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=7099924. (Accessed on 7 February 2024).

- Barajas, Leomary Niño. Estudio de caso: una estrategia para la enseñanza de la educación ambiental. Praxis & Saber 3.5, 2012: 53-78. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/4772/477248389003.pdf. (Accessed on 5 March 2024).

- Huckle, John.; Arjen EJ Wals. The UN Decade of Education for Sustainable Development: business as usual in the end. Neoliberalism and Environmental Education, 2018: 203-218. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9781315388786-17/un-decade-education-sustainable-development-business-usual-end-john-huckle-arjen-wals. (Accessed on 5 April 2024).

- Gutiérrez, José, Javier Benayas.; Susana Calvo. Educación para el desarrollo sostenible: evaluación de retos y oportunidades del decenio 2005-2014. Revista Iberoamericana de educación 40, 2006: 25-69.

- Asencio, Enrique Navarro.; Eva Jiménez García.; Soledad Rappoport Redondo.; Bianca Thoilliez Ruano. Fundamentos de la investigación y la innovación educativa. La Rioja, Spain: UNIR editorial, 2017. https://www.academia.edu/download/63914904/Investigacion_innovacion20200714-76954-16h68ce.pdf. (Accessed on 15 March 2024).

- Toker, Umut.; Denis O. Gray. Innovation spaces: Workspace planning and innovation in US university research centers. Research policy 37.2, 2008: 309-329. [CrossRef]

- Morales-Rubiano, María Eugenia.; Carolina Ortiz-Riaga.; Yenni Viviana Duque-Orozco.; Paola Andrea Plata-Pacheco. Fuentes de conocimiento e imágenes de la innovación en micro y pequeñas empresas de turismo: agencias de viajes y hoteles en Bogotá y Pereira. Revista de Investigación, Desarrollo e Innovación 7.2, 2017: 217-230. [CrossRef]

- Chica, J. C. La importancia de innovación en las actividades turísticas de recreación en las operadoras turísticas del puerto El Morro, de la provincia del Guayas en el año 2017. Tesis de grado. Repositorio de la Universidad Estatal de la Península de Santa Elena, Ecuador. 2017. https://repositorio.upse.edu.ec/bitstream/46000/4126/1/UPSE-THT-2017-0005.pdf. (Accessed on 20 February 2024).

- Pasaco, B.; Agudo, K. Análisis de la innovación en las Mipymes turísticas de la ciudad de cuenca en los años 2011 y 2012. Tesis de grado. Universidad de Cuenca Ecuador. 2014. Disponible en: http://dspace.ucuenca.edu.ec/bitstream/123456789/5604/1/Tesis.pdf. (Accessed on 18 January 2024).

- Morales, M.; León, A. Adiós a los mitos de la innovación. Una práctica para innovar en América Latina. Ed. Innovare. 2013. Disponible en: http://www.quieroinnovar.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/Capitulo1AdiosALosMitosDeLaInnovacion.pdf. (Accessed on 15 January 2024).

- González, M.; León, C. Turismo sostenible y bienestar social ¿cómo innovar esta industria global? Ed. Erasmus. Madrid. 2010. https://books.google.es/books?hl=es&lr=&id=EDAo6ThGYNUC&oi=fnd&pg=PA1&dq=Gonz%C3%A1lez,+M.%3B+Le%C3%B3n,+C.+Turismo+sostenible+y+bienestar+social+%C2%BFc%C3%B3mo+innovar+esta+industria+global%3F+Ed.+Erasmus.+Madrid.+2010&ots=wwPUvYMQ3g&sig=UQ7JSystuUWm5SkiwxvHYgDTPZs. (Accessed on 16 February 2024).

- Molina Ruiz, Enriqueta. Creación y desarrollo de comunidades de aprendizaje: hacia la mejora educativa. Revista de Educación, 337, 2005: 235-250. https://redined.educacion.gob.es/xmlui/bitstream/handle/11162/68041/00820053000214.pdf?sequence=1. (Accessed on 7 April 2024).

- Harrington, Denis.; Arthur Kearney. The business school in transition: New opportunities in management development, knowledge transfer and knowledge creation. Journal of European Industrial Training 35.2, 2011: 116-134. https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/03090591111109334/full/html. (Accessed on 16 April 2024).

- Karpov, Alexander O. Education for knowledge society: Learning and scientific innovation environment. Journal of Social Studies Education Research 8.3, 2017: 201-214. https://dergipark.org.tr/en/download/article-file/375096. (Accessed on 21 April 2024).

- Giorgou Tzampazi, Stella. The effects of deductive, inductive and a combination of both types of grammar instruction in pre-sessional classes in higher education. Doctoral thesis. University of Bedfordshire. 2019. https://uobrep.openrepository.com/handle/10547/624036. (Accessed on 10 April 2024).

- Figueiró, Paola Schmitt.; Daiane Mülling Neutzling.; Bruno Lessa. Education for sustainability in higher education institutions: A multi-perspective proposal with a focus on management education. Journal of Cleaner Production 339, 2022: 130539. [CrossRef]

- Azungah, Theophilus. Qualitative research: deductive and inductive approaches to data analysis. Qualitative research journal 18.4, 2018: 383-400. https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/QRJ-D-18-00035/full/html. (Accessed on 7 April 2024).

- Yom, Sean. From methodology to practice: Inductive iteration in comparative research. Comparative Political Studies 48.5, 2015: 616-644. [CrossRef]

- Schadewitz, Nicole.; Jachna, Timothy. Comparing inductive and deductive methodologies for design patterns identification and articulation. In: International Design Research Conference IADSR 2007 Emerging Trends in Design Research, 12-15 Nov 2007, Hong Kong. http://www.sd.polyu.edu.hk/iasdr/index.htm. (Accessed on 7 May 2024).

- Kilroy, D. A. Problem based learning. Emergency medicine journal 21.4, 2004: 411-413. [CrossRef]

- Hung, Woei, David H. Jonassen.; Rude Liu. Problem-based learning. Handbook of research on educational communications and technology. Routledge, 2008. 485-506. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9780203880869-42/problem-based-learning-woei-hung-david-jonassen-rude-liu. (Accessed on 26 May 2024).

- Picazo, P.; Moreno, S. Difusión de la investigación científica en turismo. El caso de México. El Periplo Sustentable, núm. 24, enero-junio, 2013, pp. 7-40. https://accedacris.ulpgc.es/bitstream/10553/22732/2/Difusi%C3%B3n_investigaci%C3%B3n_M%C3%A9xico.pdf. (Accessed on 6 March 2024).

- Bowen, John T. Managing a research career. International journal of contemporary hospitality management 17.7, 2005: 633-637. [CrossRef]

- Jogaratnam, G., Chon, K., Mccleary, K., Mena, M. y Yoo, J. An Analysis of Institutional Contributors to Three Major Academic Tourism Journals: 1992-2001. En Tourism Management, vol. 26, 2005, núm. 5, pp. 641-648. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W. y Ritchie, J. R. B. An Investigation of Academic Leadership in Tourism Research: 1985-2004. En Tourism Management, vol. 28, 2007, núm. 2, pp. 476-490. [CrossRef]

- Park, K., Phillips, W.J., Canter, D.; Abbott, J. Hospitality and Tourism Research Rankings by Author, University, and Country using Six Major Journals: The First Decade of the New Millennium. En Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Research, vol. 35, 2011, núm. 3, pp. 381-416. [CrossRef]

- Mullo Romero, Esther del Carmen.; Jenny Patricia Castro Salceso.; Samuel Ricardo Guillén Herrera. Innovación y desarrollo turístico. Reflexiones y desafíos. Revista Universidad y Sociedad 11.4, 2019: 394-399. http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?pid=S2218-36202019000400394&script=sci_arttext&tlng=pt. (Accessed on 10 January 2024).

- Vergel, M; Vega, O; Bustos, V. J. Modelo de quíntuple hélice en la generación de ejes estratégicos durante y postpandemia 2020. Revista Boletín Redipe, 2022 vol. 9 (9):92-105. https://revista.redipe.org/index.php/1/article/view/1066. Consulted 30 june 2022.

- Carayannis, E.G; Barth, T. D; Campbell, D. The Quintuple Helix innovation model: global warming as a challenge and driver for innovation. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship 2012 volume 1, number: 2. http://transicionsocioeconomica.blogspot.com/2020/01/modelos-de-quinduple-helice.html. Consulted 10 july 2022.

- Castillo-Vergara, M. La teoría de las N-hélices en los tiempos de hoy. Journal of technology management & innovation, 2020 Volumen 15(3), 3-5. https://www.scielo.cl/pdf/jotmi/v15n3/0718-2724-jotmi-15-03-3.pdf. Consulted 25 june 2022.

- Dooley, Kim E. Hacia un modelo holístico para la difusión de tecnologías educativas: una revisión integradora de los estudios de innovación educativa. Revista de Tecnología y Sociedad Educativa 2.4, 1999: 35-45. https://www.jstor.org/stable/jeductechsoci.2.4.35. (Accessed on 3 April 2024).

- Mosquera-Esparza, Z. A.; Mosquera-Esparza, M. E.; Suárez-Monzón, N. Estrategias para la mejora de la gestión de la innovación didáctica en los docentes de la Unidad Educativa “Los Andes”. Revista Metropolitana de Ciencias Aplicadas, 6(1), 2023: 168-177. https://remca.umet.edu.ec/index.php/REMCA/article/view/612/618. (Accessed on 19 February 2024).

- Juárez-Ibarra, Gerónimo. El rol del docente ante un ambiente innovador de aprendizaje en escuelas y facultades de negocios. El caso de la: Facultad de Administración y Contaduría. Fuentes 878.782, 2018: 56-65. https://educanew.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/LECTURA-2.-EL-ROL-DEL-DOCENTE-ANTE-UN-AMBIENTE-INNOVADOR-DE-APRENDIZAJE-EN-ESCUELAS-Y-FACULTADES-AUTOR-GERONIMO-JUAREZ.pdf. (Accessed on 21 May 2024).

- Orihuela Gallardo, Francisca.; Carmen Cristina Sierra Casanova. Una experiencia de innovación docente: el debate académico en Administración de Empresas. Revista de estudios socioeducativos Núm. 8, 2020. págs. 64-79. https://rodin.uca.es/bitstream/handle/10498/23860/RESED%20N8%20-64-79.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. (Accessed on 15 February 2024).

- Hillen S. A. ‘School Staff-centered School Development by Communicative Action: Working Methods for Creating Collective Responsibility - From the Idea to Action’. Journal on Efficiency and Responsibility in Education and Science, vol. 13, no. 4, 2020. pp. 189-203. http://dx.doi.org/10.7160/eriesj.2020.130403.

- Luque T.; Adriana M.; Pérez, I. R.; Aguilar, J. A.; Rozas, M. R. Aprendizaje cooperativo y habilidades sociales: Universidad Nacional Jorge Basadre Grohmann. Horizonte de la Ciencia, vol. 11, núm. 21, 2021, Julio-, pp. 239-254. [CrossRef]

- García-Almiñana, Daniel, and Beatriz Amante García. Algunas experiencias de aplicación del aprendizaje cooperativo y del aprendizaje basado en proyectos. I Jornadas de Innovación Educativa. Escuela Politécnica Superior de Zamora, 2006. https://upcommons.upc.edu/handle/2117/9489. (Accessed on 10 May 2024).

- Sánchez, Gerardo I.; Claudia M.; Concha.; Carolina A. Rojas. Hackathon social como metodología activo-participativa para el aprendizaje colaborativo e innovador en la formación universitaria. Información tecnológica 33.4, 2022: 161-170. http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0718-07642022000400161.

- Consejo Universitario de la Universidad Técnica de Manabí. Carrera de Turismo. Facultad de Ciencias Administrativas y Económicas. 2024. https://www.utm.edu.ec/turismo. (Accessed on 3 February 2024).

- Siu, Jenny Liliana Rodríguez. Las habilidades blandas como base del buen desempeño del docente universitario. Innova research journal 5.2, 2020: 186-199. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, Odalys Marrero.; Rachida Mohamed Amar.; Jordi Xifra Triadú. Habilidades blandas: necesarias para la formación integral del estudiante universitario. Revista científica ECOCIENCIA 5, 2018: 1-18. [CrossRef]

- Noah, Joanna Bunga.; Azlina Abdul Aziz. A Systematic review on soft skills development among university graduates. EDUCATUM Journal of Social Sciences 6.1 (2020): 53-68.

- Pozo, Juan Ignacio.; Carles Monereo. Introducción: La nueva cultura del aprendizaje universitario o por qué cambian nuestras formas de enseñar y aprender. Psicología del aprendizaje universitario. Ediciones Morata. 2009: 9-28. https://www.torrossa.com/en/resources/an/2953088. (Accessed on 21 May 2024).

- Suárez-Escudero, Juan Camilo.; María Camila Posada-Jurado.; Lennis Jazmín Bedoya-muñoz.; Alejandro José Urbina-Sánchez.; Jorge Luis Ferreira-Morales.; César Alberto Bohórquez-Gutiérrez. Enseñar y aprender anatomía: Modelos pedagógicos, historia, presente y tendencias. Acta Médica Colombiana 45.4, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Coelho, Maria João.; Helena Martins. The future of soft skills development: a systematic review of the literature of the digital training practices for soft skills. Journal of E-learning and Knowledge Society 18.2, 2022: 78-85. [CrossRef]

- Álvarez Álvarez, María del Carmen.; Elia Fernández Díaz.; Gonzalo Silió Saiz. Planificación, colaboración, innovación: tres claves para conseguir una buena práctica docente universitaria. REDU: Revista de Docencia Universitaria, 10(1), 2012, 415-430. [CrossRef]

- Romillo, Antonio de J., and Cecilia J. Polaino. Aplicación del modelo de gestión pirámide del desarrollo universitario en la universidad de Otavalo, Ecuador. Formación universitaria 12.1, 2019: 3-12. http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0718-50062019000100003.

- Jayaram, S.; Musau, R. Habilidades blandas: qué son y cómo fomentarlas. En: Jayaram, S., Munge, W., Adamson, B., Sorrell, D., Jain, N. (eds) Bridging the Skills Gap. Educación y formación técnica y profesional: problemas, preocupaciones y perspectivas, vol 26. Springer, Cham. 2017. págs. 101-122. [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, Shirley Tanya Basurto.; Moreira-Cedeño, José Alexander.; Velásquez-Espinales, Angélica Narcisa.; Rodríguez-Gámez, María. Autoevaluación, Coevaluación y Heteroevaluación como enfoque innovador en la práctica pedagógica y su efecto en el proceso de enseñanza-aprendizaje.” Polo del Conocimiento: Revista científico-profesional 6.3 (2021): 828-845. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=7926891. (Accessed on 7 May 2024).

- Morales Páez, Marcela.; Rodolfo García-Galván. Colaboración tecnocientífica academia-empresa. Un análisis de la percepción de profesores-investigadores. Economía: teoría y práctica 52, 2020: 171-206. [CrossRef]

- Santos, José Lázaro Quintero.; Francisco Mena Galárraga.; Diego Alfredo Salazar Duque. Reflexiones Acerca Del Desarrollo Del Turismo: caso de estudio observatorio de turismo para la Provincia de Pichincha. Anais Brasileiros de Estudos Turísticos 2018: 100-110.

- Hasing Sánchez, Lila Pilar.; Víctor Manuel Vera Peña.; Samuel Ricardo Guillén Herrera. La práctica pre profesional en el currículum de la carrera Turismo. Conrado 14.64, 2018: 40-45. http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?pid=S1990-86442018000400040&script=sci_arttext. (Accessed on 15 February 2024).

- Marín, Haideé Coromoto.; Soria Velasco, Román Eduardo.; Bravo Medina, Carlos Alfredo.; Reyes Vargas, María Victoria.; Gamboa Ríos, María Germania.; Manjarrez Fuentes, Nelly Narcisa.; del Corral Villaroel, Víctor Hugo. Evaluación del currículo ofertado por la Universidad Estatal Amazónica para la carrera de Ingeniería en Turismo. Revista Educación. vol. 42, núm. 2, 2018: 318-334. [CrossRef]

- Rosero, Cecilia Yacelga.; Hada Solórzano Robinson. La sustentabilidad en el currículo del profesional de turismo en la Universidad Politécnica Estatal del Carchi UPEC. Tierra Infinita 5.1, 2019: 189-200.

- Zaitseva, Natalia A.; Anna A. Larionova.; Olga V. Skrobotova.; Svetlana N. Trufanova.; Elena V. Dashkova. The Business Integration Mechanism and the Training System for the Tourism Industry. International Electronic Journal of Mathematics Education 11 no. 6, 2016: 1713-1722. https://www.iejme.com/article/the-mechanism-of-business-integration-and-the-training-system-for-the-tourism-industry. (Accessed on 7 May 2024).

- Pelegrín Entenza, Norberto.; María Rosa Naranjo Llupart.; Liliana Elvira López Báster.; Leonardo Ramón Marín Llaver. Perspectiva del currículo de la licenciatura en turismo de la Universidad Técnica de Manabí. Encuentros. Revista de Ciencias Humanas, Teoría Social y Pensamiento Crítico. 19 (septiembre-diciembre). 2023: 190-207.

- Tronchoni, H.; Izquierdo, C.; Anguera, M.T. Interacción participativa en las clases magistrales: fundamentación y construcción de un instrumento de observación. Publicaciones, 48(1), 2018. 81-108.

- Rogers, Draper D. “Enseñanza expositiva en grupos pequeños: capacitar a líderes de grupos pequeños sobre cómo desarrollar y enseñar lecciones expositivas”. Tesis y Proyectos Doctorales. 2022. 3697. https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/doctoral/3697. (Accessed on 17 May 2024).

- Fernández, María José Mayorga; Dolores Madrid Vivar. Modelos didácticos y Estrategias de enseñanza en el Espacio Europeo de Educación Superior. Tendencias pedagógicas 15, 2010: 91-111. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=3221568. (Accessed on 18 February 2024).

- Ellis, Edwin S. An instructional model for teaching learning strategies. Focus on exceptional children 23.6, 1991: 1-24. https://simvilledev.ku.edu/sites/default/files/PD%20Resources/ArticleELlis1.pdf. (Accessed on 11 May 2024).

- Rodríguez, María Teresa.; Antonio Delgado Trujillo.; Enrique de Justo Moscardo. Un nuevo modelo didáctico para el aprendizaje activo de Estructuras. Jornadas sobre Innovación Docente en Arquitectura: JIDA: Jornades sobre Innovació Docent en Arquitectura: JIDA 5 (2017): 496-506.

- Gómez Carrasco, Cosme J.; Jorge Ortuño Molina.; Pedro Miralles Martínez. Enseñar Ciencias Sociales con métodos activos de aprendizaje. Ediciones Octaedro SL, 2018. http://hdl.handle.net/10201/137730. (Accessed on 18 May 2024).

- Roselli, Nestor Daniel. El aprendizaje colaborativo: Bases teóricas y estrategias aplicables en la enseñanza universitaria. Revista Propósitos y Representaciones; 4; 1; 4, 2016; 219-280.

- Díez Gutiérrez, Enrique Javier. Modelos socioconstructivistas y colaborativos en el uso de las TIC en la formación inicial del profesorado. Revista de Educación, 358. Mayo-agosto 2012, pp. 175-196. [CrossRef]

- Maldonado, Marisabel. Aprendizaje basado en proyectos colaborativos. Una experiencia en educación superior. Laurus 14.28. 2008: 158-180. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/761/76111716009.pdf. (Accessed on 27 May 2024).

- Espinoza Freire, Eudaldo Enrique. El aprendizaje basado en problemas, un reto a la enseñanza superior. Conrado 17.80, 2021: 295-303. http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?pid=S1990-86442021000300295&script=sci_arttext&tlng=pt. (Accessed on 5 February 2024).

- Oblitas De Las Casas, Karla Mariela. Modelo didáctico basado en el trabajo colaborativo para mejorar el aprendizaje del pensamiento lógico en estudiantes del nivel superior. Tesis doctoral. Universidad Cesar Vallejo Chiclayo Perú. 2020. https://repositorio.ucv.edu.pe/bitstream/handle/20.500.12692/40972/Oblitas_DLCKM.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. (Accessed on 21 February 2024).

- Grover, Rajiv. Multi-disciplinary and inter-disciplinary research. Journal of Market-Focused Management 1, 1996: 275-275. [CrossRef]

- Abeysekara, A. Multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary research. Journal of the National Science Foundation of Sri Lanka. Volumen: 49 Edición: 2, 2021. Página 135.

- Hernández-Sampieri, R.; Fernández-Collado, C.; Baptista-Lucio, P. Metodología de la Investigación, 5th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2010. Available online: https://www.ecotec.edu.ec/material/material_2017F_CSC244_11_80241.pdf. (accessed on 11 January 2024).

- Dahl, Per. Hypothetico-Deductive Method. Music and Knowledge: A Performer’s Perspective. Brill, 2017. 51-61. [CrossRef]

- Moisey, R. Neil.; Stephen F. McCool. Sustainable tourism in the 21st century: Lessons from the past; challenges to address. Tourism, recreation and sustainability: Linking culture and the environment. 2008: 283-291. https://books.google.es/books?hl=es&lr=&id=huoLBvVw0gkC&oi=fnd&pg=PA283&dq=Sustainable+tourism+for+the+21st+century&ots=Q2236W4rWz&sig=C-ud6iupn4rliPlS7dwnUvMFyJU. (Accessed on 7 May 2024).

- Farid, Hadi.; Fatemeh Hakimian.; Vikneswaran Nair.; Pradeep Kumar Nair.; Nazari Ismail. Trend of research on sustainable tourism and climate change in 21st century. Worldwide Hospitality and Tourism Themes 8.5, 2016: 516-533. [CrossRef]

- Anguera, M. Teresa.; Mariona Portell.; Salvador Chacón Moscoso, Salvador.; Susana Sanduvete-Chaves. Indirect observation in everyday contexts: concepts and methodological guidelines within a mixed methods framework. Frontiers in psychology 9, 2018: 254638. [CrossRef]

- Rivero, José Luis Lissabet. Research experiences in the application of the Historical-logical research method and the. Analysis of Content qualitative technique in educational research. Dilemas Contemporáneos: Educación, Política y Valore Año: V. Número: 1. Artículo no.23, 2017. https://www.proquest.com/openview/92d6ce69ca5fd44574315dac99c025e5/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=4400984. (Accessed on 17 April 2024).

- Iannone, Paola.; Elena Nardi. On the pedagogical insight of mathematicians: Interaction and ‘transition from the concrete to the abstract’. The Journal of Mathematical Behavior 24.2, 2005: 191-215. [CrossRef]

- Knight, Peter. A systemic approach to professional development: learning as practice. Teaching and teacher education 18.3, 2002: 229-241. [CrossRef]

- Myers, Jerome L.; Arnold D. Well.; Robert F. Lorch Jr. Research design and statistical analysis. Routledge, Nueva York, 2013. Pgs. 832. [CrossRef]

- Hassine, Jameleddine.; Daniel Amyot. A questionnaire-based survey methodology for systematically validating goal-oriented models. Requirements Engineering 21, 2016: 285-308. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00766-015-0221-7. (accessed on 21 January 2024).

- Snyder, Hannah. Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines. Journal of business research 104, 2019: 333-339. [CrossRef]

- Consejo Universitario de la Universidad Técnica de Manabí. Reglamento de Régimen Académico de la Universidad Técnica de Manabí. 2021. https://www.utm.edu.ec/la-universidad/nuestra-universidad/reglamentos?download=1977:reglamento-de-regimen-academico-de-la-universidad-tecnica-de-manabi&start=60. (Accessed on 25 February 2024).

- Consejo Universitario de la Universidad Técnica de Manabí. Reglamento de evaluación integral al desempeño del personal académico de la Universidad Técnica de Manabí. 2018. https://www.utm.edu.ec/la-universidad/nuestra-universidad/reglamentos?download=14:reglamento-de-evaluacion-integral-al-desempeno-del-personal-academico. (Accessed on 3 February 2024).

- Bisquerra Alzina, Rafael.; Núria Pérez Escoda. “ŋPueden las escalas Likert aumentar en sensibilidad?” REIRE. Revista d’Innovació i Recerca en Educació, vol. 8, 2015, num. 2, p. 129-147. [CrossRef]

| Level | Integrative subject | Significant elements resulting from the research |

| 1st | Introduction to the Tourism System | Argue, from theoretical, methodological, and epistemological assumptions, the relationship that exists between the components that are part of the tourism system for the establishment of cause–effect relationships. |

| 2nd | Tourist Geography of Ecuador | Compare differences and similarities of the regions and tourist destinations of Ecuador, emphasizing geographical location, resources, and attractions. |

| 3rd | Tourist Modalities I | Diagnose the processes and sub-processes of tourism exploitation related to accommodation, apartments, and restaurants based on case studies linked to the community in the tourism modalities studied. |

| 4th | Regional and Ecuadorian Cuisine | Apply basic food techniques and preparations associated with regional and Ecuadorian cuisine. |

| 5th | Tourist Modalities II | Diagnose, from case studies linked to the community, the tourism modalities that are studied, along with the processes and sub-processes of tourist operations related to recreation, tourist entertainment, and bar services. |

| 6th | Quality Management in Tourism | Apply the standards, tools, and techniques used for quality management in tourism companies and their statistical foundations. |

| 7th | Integrated Management of Tourist Destinations | Apply the main tools and good practices for the integrated strategic planning and management of sustainable tourist destinations. |

| 8th | Sustainable Tourism Ventures | Design and execute sustainable tourism ventures in the areas of social and community tourism. |

| Teaching work procedures | ||

| Types of procedure | Activities | Instruments |

| Panels. | Network meetings. | Study of tourist communities. |

| Round tables. | Problem-based learning. | Presentation and evaluation of tourist services and products. |

| Debates. | Interinstitutional scientific meetings. | Checklists and process audits. |

| Forums. | Pre-professional guided scientific visits. | Verification of standards and procedure manuals. |

| Seminars. | Link with the community. | Inventories of resources and tourist attractions. |

| Discussion groups. | Video filming. | Degree projects. |

| Conversations. | Competencies and display of skills of various operational processes. | Visits to museums and work centers, tourist routes, and guided tours of cultural and natural heritage. |

| Conferences. | Practical classes to develop skills. | Process monitoring. |

| Virtual tutorials. | Experimentation projects. | Presentation of papers. |

| Case studies. | Community linkage projects. | Participatory diagnoses. |

| Meetings with clients, familiarization groups, FAM, and travel agents. | Evaluation of satisfaction rates. | Monitoring and feedback in destinations, hotels and restaurants in tourist sites. |

| Application of survey systems and feedback systems. | Website design and monitoring. | Study of tourist image in social networks. |

| Market study and research. | Application of integrated project management tools. | Presentation of tourism projects. |

| Creation of ventures. | Application of SWOT matrix and other hotel management tools. | Evaluation of tourism sustainability indicators. |

| Practical application in different tourism modalities with emphasis on sustainable tourism. | Study of good international practices in sustainable tourism. | Poster presentation. |

| Items | Sample | La |

OK (4 points) |

I have no opinion (3 points) |

In disagreement (2 points) |

Strongly disagree (1 point) |

Total points | Arithmetic average |

| 1 | 102 | 85 | 15 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 489 | 4.79 |

| 2 | 102 | 78 | 10 | 2 | 8 | 4 | 454 | 4.45 |

| 3 | 102 | 4 | 13 | 7 | 20 | 58 | 191 | 1.87 |

| 4 | 102 | 84 | 10 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 476 | 4.66 |

| 5 | 102 | 79 | 15 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 469 | 4.59 |

| 6 | 102 | 80 | 12 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 467 | 4.57 |

| 7 | 102 | 75 | 16 | 2 | 5 | 4 | 459 | 4.50 |

| 8 | 102 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 8 | 88 | 125 | 1.22 |

| 9 | 102 | 86 | 10 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 483 | 4.73 |

| 10 | 102 | 83 | 15 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 482 | 4.72 |

| 11 | 102 | 84 | 14 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 482 | 4.72 |

| 12 | 102 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 15 | 83 | 132 | 1.29 |

| 13 | 102 | 81 | 10 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 466 | 4.56 |

| 14 | 102 | 88 | 10 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 486 | 4.76 |

| 15 | 102 | 80 | 11 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 466 | 4.56 |

| Items | Upper Score | Lower Score | Average of the scores of the five items |

| Items 1 to 5 (Learning in contact with the teacher) | 4.79 | 1.87 | 4.07 |

| Items 6 to 10 (Autonomous learning) | 4.73 | 1.22 | 3.94 |

| Items 11 to 15 (Experimental practical learning) | 4.76 | 1.29 | 3.97 |

|

Evaluated competencies |

Evaluated periods | ||||

| October 2021 to February 2022 |

May 2022 to September 2022 |

October 2022 to February 2023 |

May 2023 to September 2023 |

October 2023 to January 2024 |

|

| Mastery of the contents of the subject. | 4.0 | 4.1 | 4.1 | 4.3 | 4.5 |

| Teaching methodologies used. | 4.2 | 4.2 | 4.3 | 4.5 | 4.8 |

| Use of new information and communication technologies. | 4.2 | 4.2 | 4.3 | 4.3 | 4.4 |

| Exercise of tutoring and evaluation of learning. | 3.9 | 4.3 | 4.7 | 4.8 | 5.0 |

| Ethical attitudes and interpersonal relationships. | 4.3 | 4.6 | 4.8 | 4.8 | 5.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).