Introduction

TB remains one of the deadliest infectious diseases in the world. In 2022, there were an estimated 10.6 million cases of TB, and 1.3 million people died from this disease globally. After years of constant decline, the TB incidence rate (new cases per 100 000 population per year) increased by 3.9% between 2020 and 2022. Further, in 2022 there were about 3.1 million people that were not diagnosed, or not officially reported to health authorities, thus increasing the alarming scale of TB incidence worldwide [

1].

The burden of multi-drug (MDR)- and extensively-drug resistant (XDR)-TB is considerable with 410 000 new cases of multidrug and rifampicin-resistant TB being reported in 2022. TB is a major cause of antimicrobial resistance related deaths [

1], and the high incidence of HIV-TB co-infection poses additional challenges for the control of this disease that nowadays still represents a global health threat. There is an urgent need to identify easily accessible scaffolds with anti-tubercular activity that can be developed into therapeutics to treat TB infections.

Chalcones represent a privileged scaffold in medicinal chemistry and both naturally occurring and synthetic chalcones have been reported to exert multiple biological functions. Chalcones bear the 1,3-diarylprop-2-en-1-one framework and occur naturally in ferns and higher plants [

2,

3,

4]. These compounds are precursors in the biosynthesis of flavonoids from which they differ due to the absence of a heterocyclic benzopyrone or benzopyran ring system.

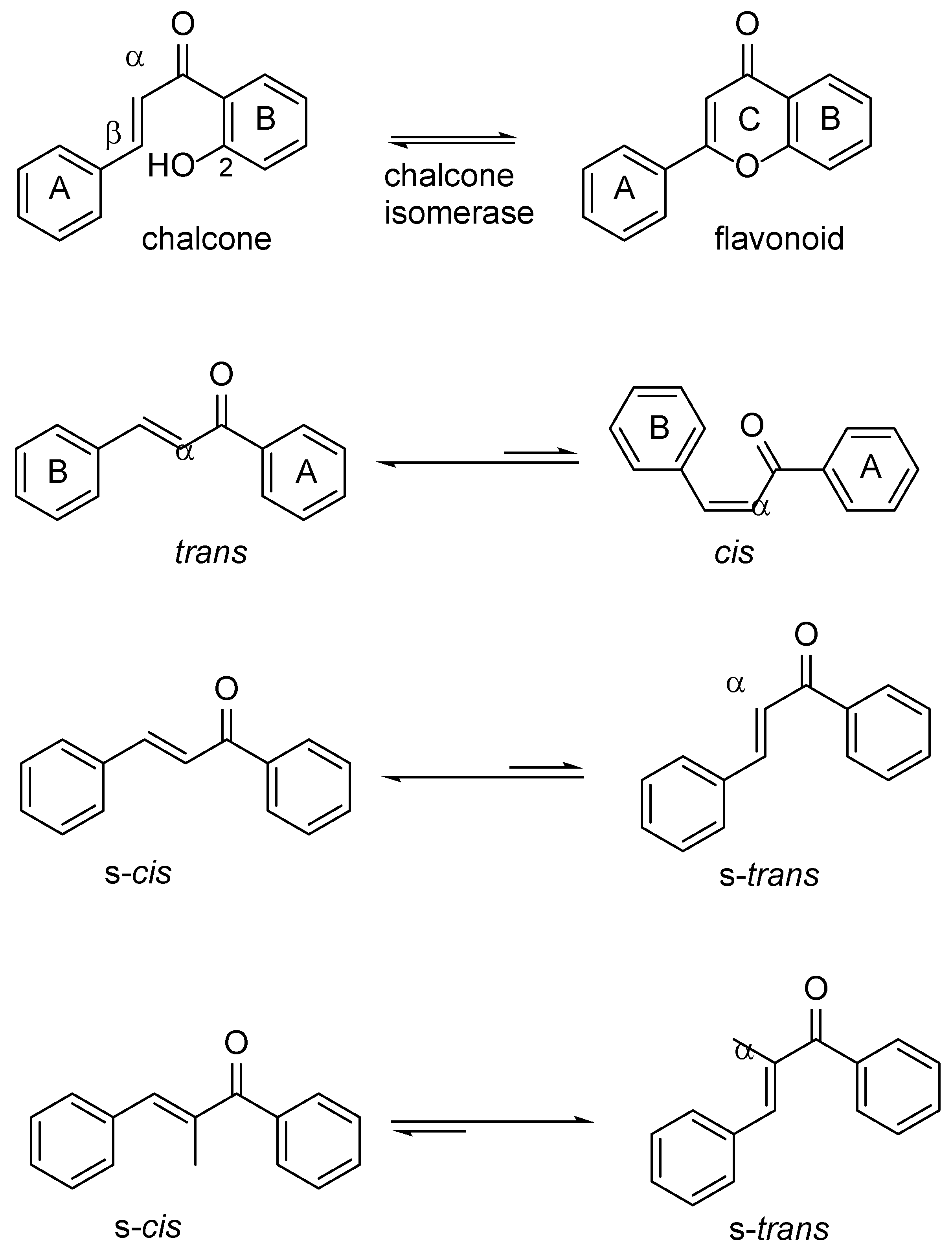

The α,β-unsaturated double bond in the enone moiety of chalcones can adopt either

cis(

Z) or

trans(

E) configuration (

Figure 1) [

5]. The

trans-isomer is thermodynamically more stable compared to the

cis-isomer, and almost all chalcones prepared are isolated in this form. In addition to cis/trans geometrical isomerism, chalcone can exist in several conformations where the conformers interconvert by rotation along single bonds. Conformational analysis of the orientation of the carbonyl group and the αβ-double bond in chalcones has revealed that in lowest activation energy they exist as two distinct conformers. The

s-cis where the carbonyl and the double bonds are positioned

cis with respect to each other, or the

s-trans where the double bonds are

trans configured with respect to each other. The s-

cis conformer is reported to be the more stable than the s-

trans, although the latter might predominate when sterically hindered substituents, such as α-methyl groups, are present [

6]. Therefore, chalcone conformational equilibria might be influenced by substitution patterns on the aryl rings [

7].

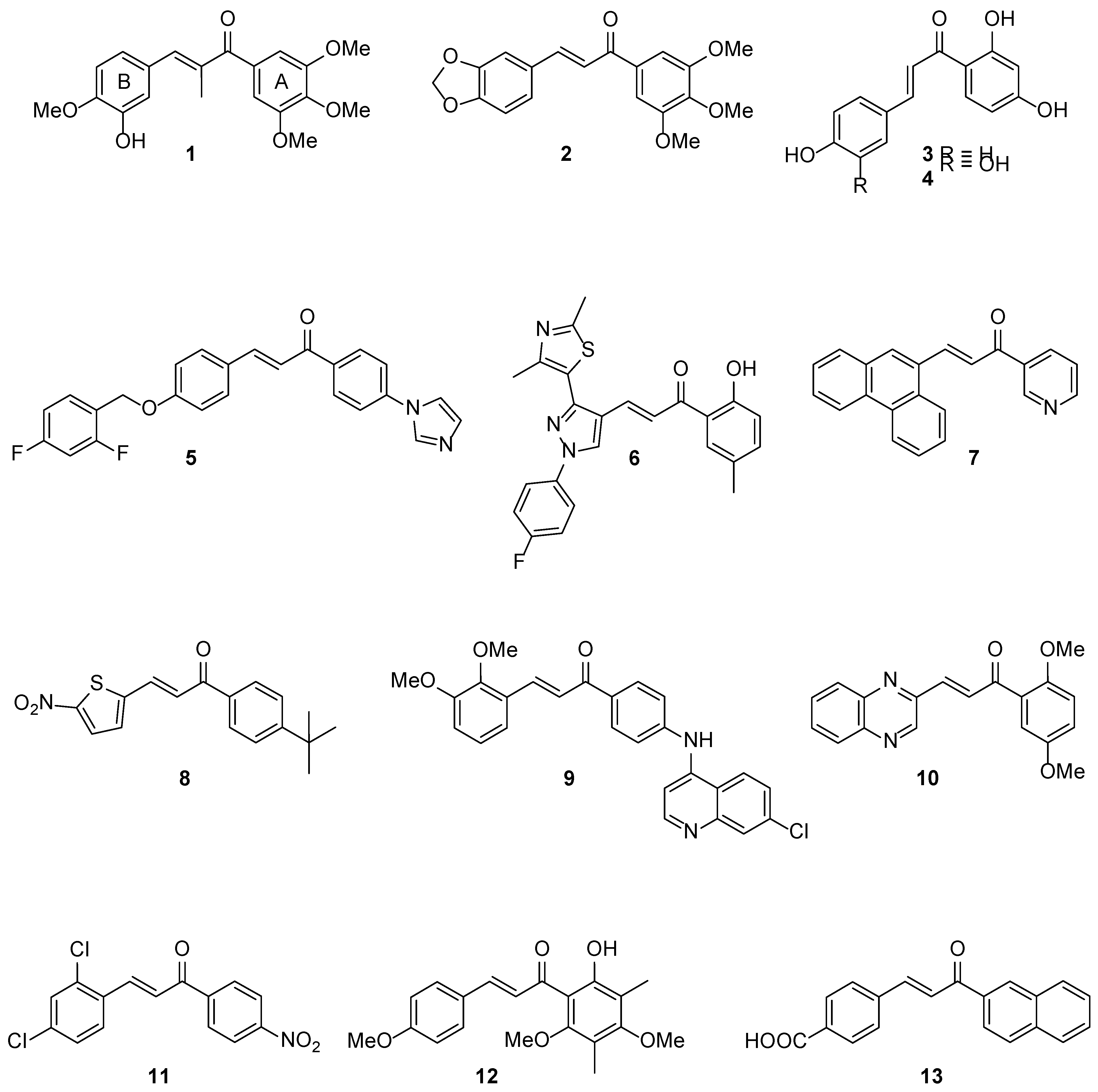

The chalcones frame is very versatile and amenable to multiple synthetic modifications leading to analogues endowed with remarkable biological properties including anti-inflammatory, anti-proliferative, antiviral, antibacterial and antifungal activities [

8,

9,

10,

11]. Members of this class of compounds displayed significant anti-proliferative activity at nanomolar levels. For example, α-methyl chalcone derivative

1 inhibited the growth of K562 human leukaemia cells [

7], whereas our previously reported chalcone anticancer prodrug

2 (DMU-135) halted proliferation of MDA-468 breast cancer cell lines upon CYP1 bioactivation [

12]. Dietary natural chalcones such as isoliquiritigenin

3 (ISL, 4, 2’,4’-trihydroxychalcone) and its tetrahydroxy analogue butein

4 (3,4,2’,4’-tetrahydroxychalcone) have been shown to possess anticancer activities (

Figure 2). Isoliquiritigenin has been reported to induce apoptosis in human hepatoma cells and butein was reported to act as an EGF receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor in cell signalling pathways [

13,

14,

15]. It has been suggested that chalcones with phenols in both A- and B-rings (e.g., butein, ISL) are generally more toxic than chalcones that possessed a benzene A-ring and a polyphenol B-ring (pyrogallol, resorcinol) [

14].

Chalcone scaffolds have also been employed to design anti-tubercular agents including imidazole derivative

5 and pyrazole-thiazole conjugate

6, which were found to be active against virulent (H37Rv) and avirulent (ATCC 25177) strains of

M. tuberculosis, respectively [

16,

17]. It can be noted that the presence of heterocyclic rings in (or closely linked to) the chalcone frame might lead to enhanced anti-tubercular activity, as can be observed in chalcone hybrids containing either pyridine (

i.e.,

7) [

18,

19], nitro-thiophene (

i.e.,

8) [

20], quinoline (

i.e.,

9) [

21,

22], and quinoxaline (

i.e.,

10) rings. Moreover, the introduction of a nitro group (

i.e.,

11) or hydroxy/poly-methoxy functional groups (

i.e.,

12) in chalcone A-rings resulted in derivatives active against

M. tuberculosis H37Rv [

23,

24].

Interestingly, naphthylchalcone analogues were found to inhibit

M. tuberculosis protein tyrosine phosphatases A and B (Mtb PtpA and B) with IC

50 values in the low-micromolar range. Docking studies revealed that the presence of the bulky, hydrophobic 2-naphthyl substituent in the A-ring of chalcone

13 played an important role in the inhibition of Mtb PtpB [

22].

Given the therapeutic potential of this class of compounds, we sought to investigate a series of aryl- and heteroaryl-chalcones for their antitubercular activity and cytotoxicity in cancer and non-cancer breast cells, and HepG2 cells. The structural insights and SARs reported here may be beneficial for the design of potent and cost effective anti-tubercular agents.

Chemistry

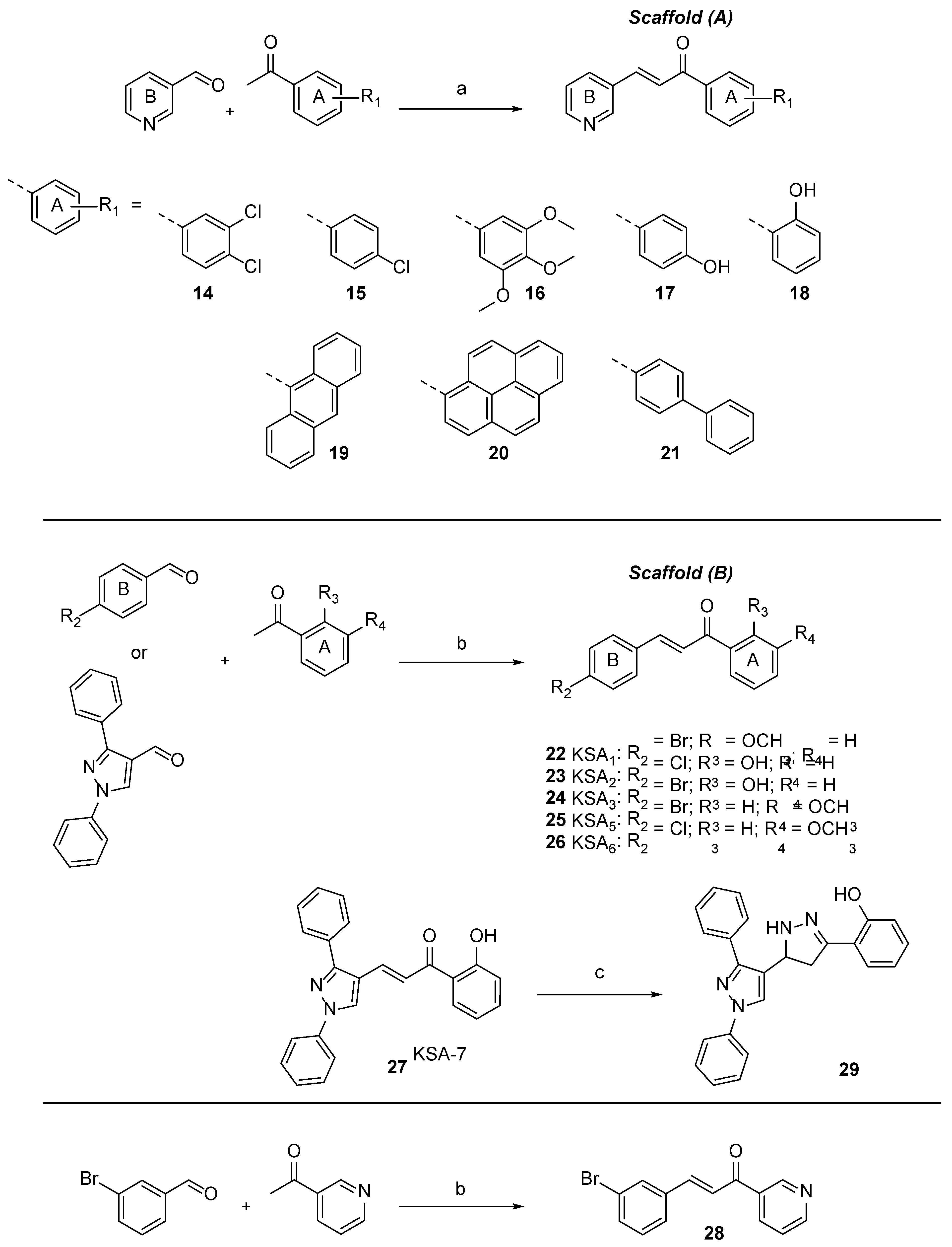

Two chalcone frameworks were selected for our synthetic campaign and included the (E)-1-(phenyl-1-(pyridin-4-yl)prop-2-en-1-one (Scaffold A or pyridyl chalcones) and (E)-1-(4-chloro/bromophenyl)- or (E)-3-(1,3-diphenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)-1-(hydroxy/methoxy-phenyl)prop-2-en-1-one (Scaffold B or aryl chalcones), as previously reported derivatives bearing pyridinyl and hydroxyphenyl moieties (e.g., compounds 6 and 7) exhibited attractive antitubercular activities.

Chalcones are readily synthesized by the Claisen-Schmidt condensation reaction of a benzaldehyde and acetophenone in equimolar quantities in the presence of a base or acid catalyst. Synthesis of Scaffold A required the use of aprotic anhydrous solvent with freshly made lithium diisopropylamide (LDA) as the base, whereas chalcones containing Scaffold B were prepared employing aqueous sodium hydroxide solution (50%w/v) with methanol as the solvent (

Scheme 1). A series of acetophenones with different physicochemical properties were incorporated in Scaffold A analogues to assess their ability to penetrate the thick lipophilic cell envelope of

M. tuberculosis and arrest its growth. Three previously reported chalcones (

2,

20 and

21) [

25,

26,

27], which were designed as anti-proliferative and CYP1 enzyme inhibiting agents, were re-synthesised and evaluated, for the first time, against

M. tuberculosis H37Rv.

Biological Evaluation

The compounds were screened against wild-type

M. tuberculosis H37Rv and inhibitory concentrations were determined. Cytotoxicity was evaluated in HepG2, “normal” MCF10A and breast cancer MDA468 cell lines (

Table 1). Pyridyl chalcones

14,

20 and

21 exhibited anti-tubercular activity in the low micromolar range with IC

90 values ranging from 8.9 – 28 µM. The biphenyl-moiety bearing chalcone

21 [

25] was the most active against

M. tuberculosis with an IC

90 value of 8.9 µM, although it showed toxicity across the panel of “normal” and cancer eukaryotic cells used in this study. This trend was observed for all Scaffold (A) chalcones excluding pyridyl chalcones

17 and

18 that contained hydroxyphenyl units in their A rings. The presence of hydroxy groups in the A rings of

17 and

18 abolished the chalcones anti-tubercular activity, while preserving their ability to inhibit the growth of MDA-468 cancer cells with IC

50 values of 30 and 8 µM, respectively. Trimethoxy-phenyl (

16) and anthracene-9-yl (

19)-including chalcones exhibited IC

90 values of 59 and 48 µM, respectively, against

M. tuberculosis, and were the most cytotoxic, amongst the compounds tested, in MDA468 cells with IC

50 values of 0.7 and 0.3 µM, respectively. HepG2 toxicity was observed for the majority of pyridyl-chalcones.

The contribution of the B ring to the anti-tubercular activity of Scaffold A derivatives was also evaluated. To this end, the “reversed” chalcone

28 was synthesised to establish whether the replacement of the pyridine B ring with a

m-bromo-phenyl moiety affected the anti-tuberculosis activity. It was found that the position of the pyridine unit within the chalcone frame,

i.e., ring A or B, did not overly influence the

M. tuberculosis growth inhibitory properties of

28 that were comparable to those of other pyridyl chalcones, such as

15,

16 and

19 synthesised in this study. Chalcone

28 exhibited cytotoxic activity in MCF10A and MDA468 cell lines. Further, we tested our previously reported chalcone

2 [

12], which included the 3,4-methylenedioxy phenyl B ring. Chalcone

2 did not exhibit anti-tubercular activity but showed selectivity for CYP1 expressing MDA468 breast cancer cells.

Subsequent steps in the chalcone frame modification included the replacement of pyridyl B ring with either p-Cl- / p-Br-phenyl or diphenyl-pyrazole rings leading to compounds 22-27.

Scaffold B chalcones bearing a 2-hydroxyphenyl units in ring A were inactive, i.e., 23, 24 and 27 (IC90 = 97 - 100 μM), whereas 3-methoxyphenyl moieties were well tolerated with analogues 25 and 26 showing IC90 values of 29 and 28 μM, respectively. Interestingly, chalcone 22, which had a 2-methoxyphenyl unit in ring A, showed very weak activity against M. tuberculosis with an IC90 value of 80 μM.

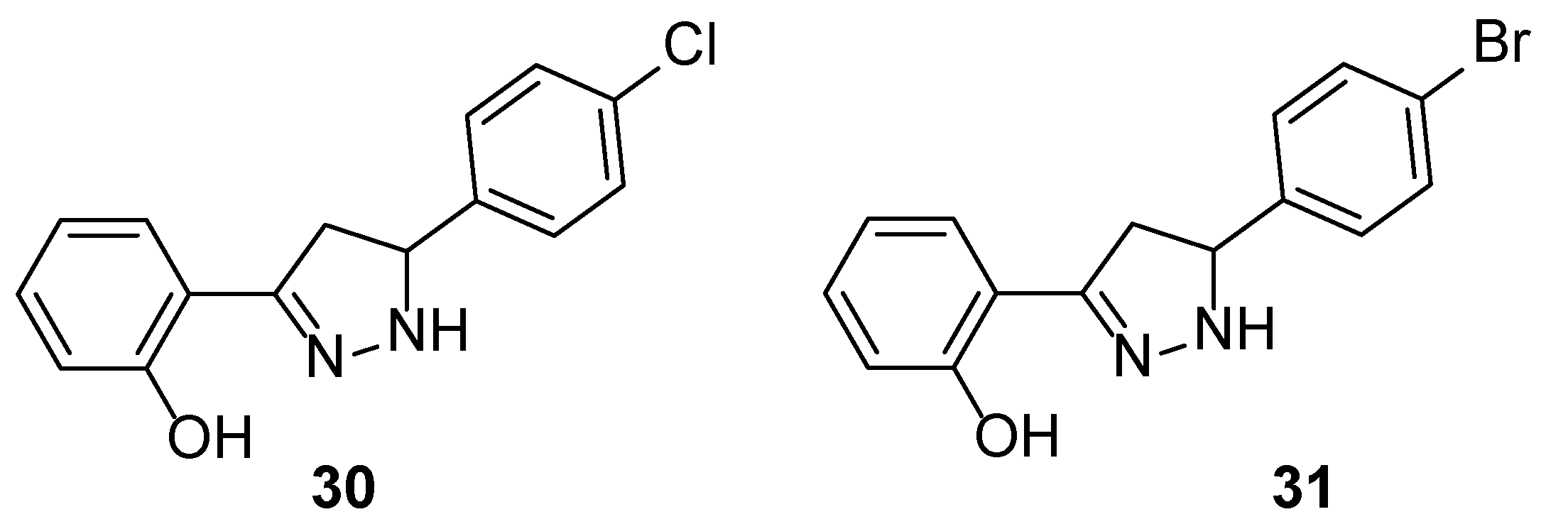

At this stage we were interested to determine whether modification of the framework of chalcones bearing a 2-hydroxyphenyl A ring might lead to derivatives with improved anti-tubercular activities. To this end, we converted the inactive chalcone

27 into pyrazoline

29 that was found to exhibit an IC

90 value of 25 μM (IC

50 = 11 μM). This growth inhibitory activity correlated well with the anti-tubercular properties of previously reported mycobactin analogue-pyrazoline

31 (IC

90 = 34 μM; IC

50 = 23 μM) [

28], which was re-synthesised and screened in this study.

Molecular Modelling

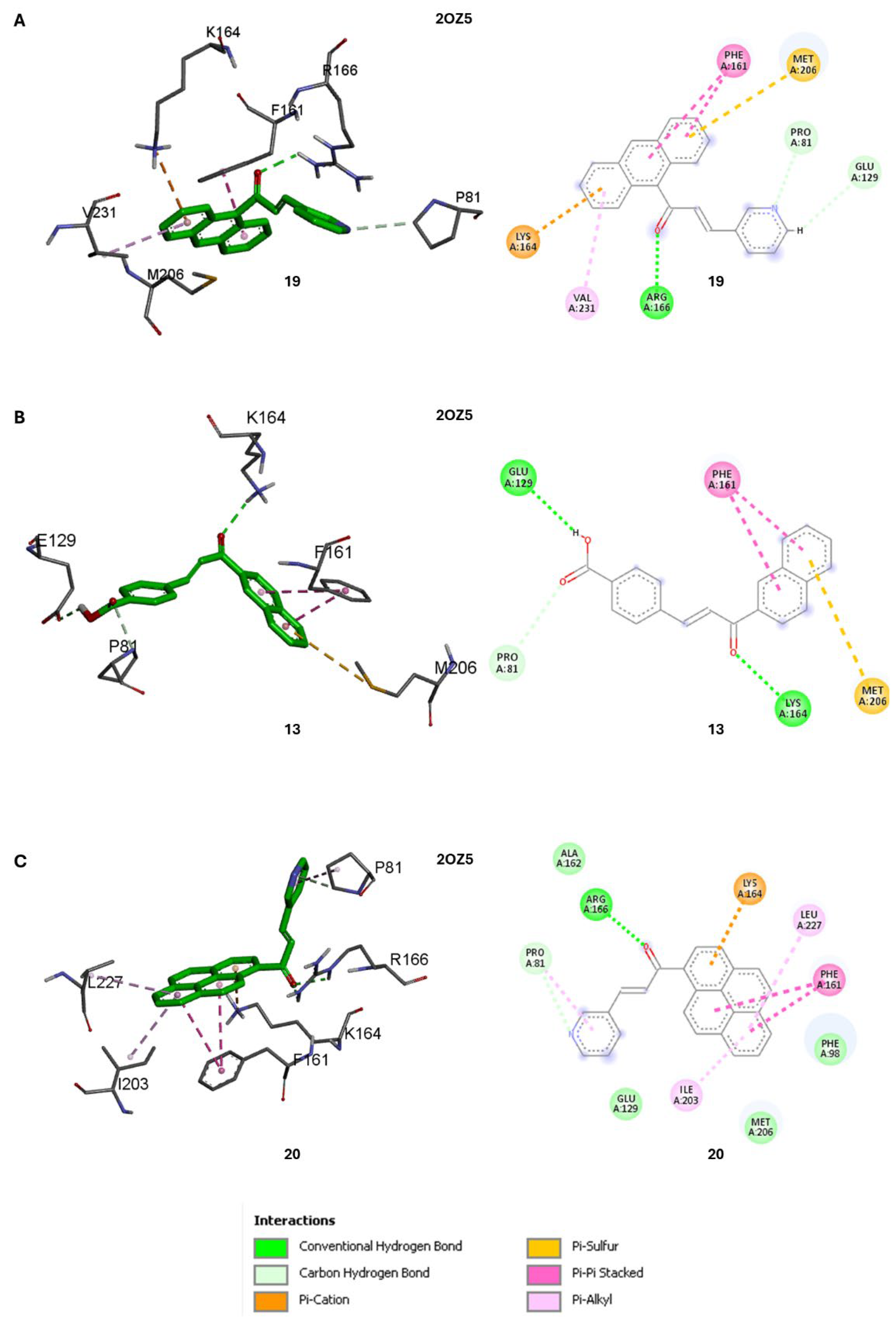

Given the structural similarity of known Mtb PtpB inhibitor 13 with pyridyl chalcones 19, 20 and 21, which contained lipophilic A-rings, we sought to predict whether these analogues would bind to either Mtb PtpA (PDB ID: 1U2P) or Mbt PtpB (PDB ID: 2OZ5). CYP1 inhibitor 2 (DMU-135) was also included in the phosphatases docking studies.

Two different software packages were used to study putative binding of these molecules in both enzymes,

i.e., Autodock Vina [

29] and GOLD [

30], according to our previous methods [

31] (

Table 2). The docking score is an estimation of the binding affinity between the small molecules and the target proteins, with more negative values indicating stronger predicted binding, while higher GoldScore fitness values generally indicate a stronger predicted binding affinity between the molecule and the target protein. It is important to note that docking studies are primarily used for relative comparisons of binding affinities between different small molecules for a specific protein target, rather than direct comparisons of binding across different protein targets. Nevertheless, the consistent trend observed in both the Vina docking scores and GoldScore fitness values suggested that the chalcones analysed in this modelling study (

2, 13, 19, 20 and

21) may exhibit a higher binding affinity towards Mtb PtpB (PDB ID: 2OZ5) compared to Mtb PtpA (PDB ID: 1U2P). Compound

20, which exhibited a MIC

50 H37Rv of 8.8 μM, was predicted to be the most promising candidate, showing the best docking scores, when compared to

13, against PtpB according to the Vina docking program. Based on the GoldScore fitness scores, compound

19 appeared to be a stronger binder than

20, albeit marginally. Chalcone

2, which had no antitubercular activity, showed the least favourable docking score for both PtpA or PtpB amongst the compounds analysed.

Previous virtual screening for an inhibitor of Mbt PtpB target employed a consensus scoring approach by comparing the results of five different software packages and revealed the importance of hydrogen bonds formed between the ligand and three residues (K164, D165, and R166) and a lipophilic pocket formed by P81, H94, F98, L101, Y125, M126, F161, L199, I203, L227, V231, and L232 [

32].

A detailed analysis of the most favourable binding poses of

13 in PtpB (2OZ5) obtained by Autodock Vina showed the presence of a hydrogen bond between K164 with the keto group of the chalcone frame (

Figure 4B). For

19, only one of three hydrogen bonds (E129, K164 and R166) specified in the model is detected in the binding pose, e.g., R166 side chain interacting with keto group of

19. However, additional relevant interactions are observed between the anthracenyl unit of

19 and F161, K164, M206 and V231 residues, and between the pyridine ring of

19 and P81 and E129 of PtpB (2OZ5) (

Figure 4A).

Similarly, in the binding pose of

20, only one hydrogen bond was detected with R166, although the molecule interacted with an even higher number of relevant residues, namely P81 (with pyridine ring of

20), F98, F161, K164, I203 and L227 (with pyrene ring of

20), compared to both

13 and

19 (

Figure 4C). This likely led to the more favourable (Vina) docking score of

20 (-9.6 kcal/mol) compared to

13 (-9.2 kcal/mol) for the PtpB (PDB ID: 2OZ5) target (

Table 2). Compound 20 had a

While these computational findings provide valuable guidance for prioritising compounds and targets for further experimental evaluation, it is crucial to validate these predictions through biochemical and biophysical assays to confirm the actual binding affinities and selectivity profiles of these compounds against Mtb PtpA and PtpB.

Conclusions

Chalcones represent an easily accessible synthetic framework endowed with significant biological, and most importantly, anti-tubercular properties. The pyridine-based chalcones reported here had growth inhibition activities in the low micromolar region against H37Rv strains with dichloro-phenyl- (14), pyrene-1-yl (20)- and biphenyl-4-yl (21)-including compounds exhibiting MIC90 values ranging from 8.9 - 29 μM. The obvious downside associated with Scaffold A pyridyl-chalcones being used as anti-infective lead-compounds might be their cytotoxicity, which was observed in the cell lines used in this study. However, this might be an advantage if selected compounds were solely to be deployed as antiproliferative agents. Indeed, trimethoxy-phenyl (16) and anthracene-9-yl (19) pyridyl-chalcones exhibited IC50 values of 0.7 and 0.3 µM, respectively, against MDA468 cells. A marginally improved toxicity profile can be seen for Scaffold B chalcones 25 and 26, which were active against M. tuberculosis H37Rv at concentrations as low as 28 μM and were ~five-fold less toxic to HepG2 cells compared to Scaffold A derivatives. This study indicates that the presence of an electron withdrawing group (i.e., halo-phenyl group or pyridine unit) in ring B is required for the anti-tubercular activity of the chalcones. As chalcones might serve a scaffold to construct higher chemical structures, we employed 27 (IC50 H37Rv = >100 µM) to synthesise the tri-cyclic pyrazoline 29, which was ten-fold more active (IC50 H37Rv = 11 µM) than its parent compound (27), and circa two-fold more active than mycobactin analogue 31. Molecular modelling experiments using pyridyl-chalcones and M. tuberculosis Mtb PtpA (PDB ID: 1U2P) and Mbt PtpB (PDB ID: 2OZ5) as targets revealed that compound 20 had a very favourable docking score within the PtpB site.

General Method for Scaffold A or Pyridyl Chalcones Synthesis

Compounds14 – 21, and 28. A solution of n-butyl lithium (1.6 M in hexane, 1 equiv.) was added dropwise to a stirred solution of N,N-diispropylethylamine (1 equiv.) in anhydrous THF (10 mL) at −78 °C under nitrogen. After 30 min, a solution of the appropriate acetophenone (1 equiv.) in anhydrous THF (5 mL) was added to the solution at −78 °C. Subsequently, after 10 min, a solution of the pyridine-3-carbaldehyde (1 equiv.) in THF (5 mL) was added to the reaction mixture, which was allowed to reach room temperature and stirred overnight. The mixture was quenched with water (20 mL), neutralised with 1 N hydrochloric acid, and extracted with ethyl acetate (3 × 50 mL). The combined organic fractions were washed with brine (20 mL), dried over MgSO4 and the solvent was removed in vacuo. The final compounds were purified by flash column chromatography on silica gel using a gradient elution with hexane: ethyl acetate: triethylamine (10–80% ethyl acetate, 5% triethylamine).

(E)-1-(3,4-dichlorophenyl)-3-(pyridin-3-yl)prop-2-en-1-one (14). An off-white solid. Yield: 67%. 1H-NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-D6) δ 9.04 (s, 1H), 8.62-8.41 (m, 3H), 8.11 (s, 2H), 7.82 (d, J = 40.8 Hz, 2H), 7.54 (s, 1H). 13C-NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-D6) δ 181.7, 151.3, 150.6, 148.5, 141.7, 137.4, 135.4, 131.2, 130.5, 130.3, 128.6, 123.9, 123.2. ESI-MS [M+H]. Calculated for C14H9Cl2NO: 277.0; Observed: 278.0.

(E)-1-(4-chlorophenyl)-3-(pyridin-3-yl)prop-2-en-1-one (15). An off-white solid. Yield 55%. 1H-NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-D6) δ 8.96 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H), 8.58 (dd, J = 4.8, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 8.31 (dt, J = 8.0, 1.9 Hz, 1H), 7.94 (d, J = 15.8 Hz, 1H), 7.71 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 1H), 7.62 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 7.47 (dd, J = 8.0, 4.7 Hz, 1H), 7.44 (t, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H), 7.37 (t, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 7.02-7.09 (1H). 13C-NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-D6) δ 187.7, 150.3, 149.6, 144.5, 143.3, 139.4, 135.4, 131.2, 130.5, 130.3, 128.6, 124.9, 123.1. ESI-MS [M+H]: Calculated for C14H10ClNO: 243.1; Observed: 244.1.

(E)-3-(pyridin-3-yl)-1-(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)prop-2-en-1-one (16). A pale-yellow powder. Yield 65%. 1H-NMR (600 MHz, CHLOROFORM-D) δ 8.86 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H), 8.62 (dd, J = 4.8, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 7.93 (dt, J = 7.9, 1.9 Hz, 1H), 7.78 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 1H), 7.53 (d, J = 15.8 Hz, 1H), 7.35 (dd, J = 7.9, 4.8 Hz, 1H), 7.24 (s, 1H), 3.93 (d, J = 5.3 Hz, 9H). 13C-NMR (151 MHz, CHLOROFORM-D) δ 188.5, 153.2, 151.1, 149.9, 142.9, 140.8, 134.7, 133.0, 130.7, 123.8, 123.6, 106.2, 56.4. ESI-MS [M+H]: Calculated for C17H17NO4: 299.1; Observed: 300.1.

(E)-1-(2-hydroxyphenyl)-3-(pyridin-3-yl)prop-2-en-1-one (18). An off-white powder. Yield 58%. 1H-NMR (600 MHz, CHLOROFORM-D) δ 8.89 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 8.66 (dd, J = 4.8, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 7.97 (dt, J = 7.9, 1.7 Hz, 1H), 7.92-7.89 (m, 2H), 7.73 (d, = 15.6 Hz, 1H), 7.54-7.52 (m, 1H), 7.39 (dd, J = 7.9, 4.8 Hz, 1H), 7.05 (dd, J = 8.4, 1.0 Hz, 1H), 6.98-6.96 (m, 1H). 13C-NMR (151 MHz, CHLOROFORM-D) δ 193.1, 163.7, 151.4, 150.1, 141.6, 136.7, 134.7, 130.4, 129.6, 123.8, 122.1, 119.8, 119.0, 118.8, 77.2, 77.0, 76.8. ESI-MS [M+H]: Calculated for C14H11NO2: 225.1; Observed: 226.1.

(E)-1-(pyren-1-yl)-3-(pyridin-3-yl)prop-2-en-1-one (20). An off-white powder. Yield 64%. 1H-NMR (600 MHz, CHLOROFORM-D) δ 8.81 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H), 8.66 (d, J = 9.1 Hz, 1H), 8.63 (dd, J = 4.8, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 8.29-8.26 (m, 3H), 8.24 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 8.20 (dd, J = 9.1, 6.0 Hz, 2H), 8.12 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 8.08 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.94 (dt, J = 8.0, 1.9 Hz, 1H), 7.66 (d, J = 16.2 Hz, 1H), 7.55 (d, J = 16.2 Hz, 1H), 7.36 (dd, J = 8.1, 4.8 Hz, 1H). 13C-NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-D6) δ 194.1, 151.1, 150.4, 141.6, 135.1, 133.0, 132.8, 130.7, 130.4, 130.0, 129.4, 129.2, 128.8, 128.7, 127.2, 127.0, 126.8, 126.5, 126.1, 124.4, 124.3, 124.0, 123.9, 123.5. ESI-MS [M+H]: Calculated for C24H15NO: 333.1; Observed: 334.1.

(E)-1-([1,1'-biphenyl]-4-yl)-3-(pyridin-3-yl)prop-2-en-1-one (21). A yellow solid. Yield 34%. 1H-NMR (600 MHz, CHLOROFORM-D) δ 8.89 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 1H), 8.64 (dd, J = 4.7, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 8.12 (d, J = 6.5 Hz, 2H), 7.97 (dt, J = 7.9, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 7.83 (d, J = 15.8 Hz, 1H), 7.75 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 7.67-7.64 (m, 3H), 7.49 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 7.43-7.40 (m, 1H), 7.38 (dd, J = 7.9, 4.8 Hz, 1H). 13C-NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-D6) δ 188.4, 151.0, 150.3, 144.7, 140.5, 138.8, 136.0, 135.1, 130.5, 128.4, 123.9, 123.8. ESI-MS [M+H]: Calculated for C20H15NO: 285.1; Observed: 286.1.

(E)-3-(3-bromophenyl)-1-(pyridin-3-yl)prop-2-en-1-one (28). A pale-yellow solid. Yield 55%. 1H-NMR (600 MHz, CHLOROFORM-D) δ 9.24 (q, J = 1.0 Hz, 1H), 8.82 (dd, J = 4.8, 1.7 Hz, 1H), 8.29 (ddd, J = 7.9, 2.2, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 7.81 (t, J = 1.7 Hz, 1H), 7.76 (d, J = 15.8 Hz, 1H), 7.57 (dd, J = 7.9, 1.9 Hz, 2H), 7.49-7.46 (m, 2H), 7.32 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H). 13C-NMR (151 MHz, CHLOROFORM-D) δ 188.7, 153.4, 149.8, 144.1, 136.6, 135.9, 133.7, 133.2, 131.1, 130.6, 127.3, 123.7, 123.2, 122.5. ESI-MS [M+H]: Calculated for C14H10BrNO: 286.9; Observed: 287.9.

General Method for Scaffold B Chalcones Synthesis

Compounds23,24, and 27. To a solution of the appropriate 2-hydroxyacetophenone (1 equiv.) and aromatic aldehyde (1 equiv.) in MeOH (20 mL) was added NaOH (50% w/v, 10 equiv.) dropwise under cooling (0–5°C) and stirring. After the addition was complete the reaction mixture was allowed to reach room temperature and stirred for the required amount of time until disappearance of the starting materials and formation of a precipitate, as confirmed by TLC analysis (i.e., 24 h to 48 h). The solution was then acidified to pH 2 with 2 N HCl and a yellow-reddish precipitate was collected by filtration. Recrystallisation from EtOH afforded the products.

(E)-3-(4-chlorophenyl)-1-(2-hydroxyphenyl)prop-2-en-1-one (23). 1H-NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-D6) δ 8.15-8.21 (1H), 7.95-8.02 (1H), 7.87-7.93 (2H), 7.75-7.82 (1H), 7.57-7.54 (m, 1H), 7.51 (dt, J = 9.0, 2.2 Hz, 2H), 7.01-6.98 (m, 2H). 13C-NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-D6) δ 193.7, 161.9, 143.5, 136.7, 135.7, 133.6, 131.1, 131.0, 129.3, 122.8, 121.0, 119.6, 118.0. ESI-MS [M+H]: Calculated for C15H11ClO2: 258.1; Observed: 259.1.

(E)-3-(4-bromophenyl)-1-(2-hydroxyphenyl)prop-2-en-1-one (24). 1H-NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-D6) δ 12.38 (s, 1H), 8.17 (dd, J = 8.0, 1.7 Hz, 1H), 8.00 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 1H), 7.83 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.76 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 1H), 7.68 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 7.65 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.57-7.54 (m, 1H), 6.99-6.98 (m, 1H). 13C-NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-D6) δ 193.8, 161.9, 143.6, 136.7, 133.9, 132.2, 131.9, 131.5, 131.2, 131.1, 124.6, 122.9, 121.0, 119.6, 118.0. ESI-MS [M+H]: Calculated for C15H11BrO2: 301.9; Observed: 302.9.

(E)-3-(1,3-diphenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)-1-(2-hydroxyphenyl)prop-2-en-1-one (27). 1H-NMR (600 MHz, CHLOROFORM-D) δ 8.38 (s, 1H), 8.00 (d, J = 15.8 Hz, 1H), 7.82 (dd, J = 8.7, 1.1 Hz, 2H), 7.76 (dd, J = 8.1, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 7.73-7.71 (m, 2H), 7.54-7.46 (m, 7H), 7.39-7.36 (m, 1H), 7.02 (dd, J = 8.2, 1.0 Hz, 1H), 6.92-6.89 (m, 1H). 13C-NMR (151 MHz, CHLOROFORM-D) δ 193.3, 163.6, 154.1, 139.4, 136.2, 136.1, 132.2, 129.6, 129.4, 128.9, 128.8, 127.4, 127.1, 120.0, 119.4, 119.4, 118.7, 118.6, 118.2. ESI-MS [M+H]: Calculated for C24H18N2O2: 366.1; Observed: 367.1.

Compounds 25 and 26. To a solution of the appropriate methoxy-acetophenone (1 equiv.) and aromatic aldehyde (1 equiv.) in MeOH (20 mL) was added NaOH (50% w/v, 10 equiv.) dropwise under cooling (0–5°C) and stirring. After the addition was complete, the reaction mixture was allowed to reach room temperature and stirred for the required amount of time (i.e., 24 h to 48 h). Upon completion, as indicated by the formation of a precipitate and confirmed by TLC, the reaction was quenched with water (30 mL). The resulting mixture was extracted with ethyl acetate (3 × 30 mL). The combined organic extracts were washed with brine (50 mL), dried (MgSO4) and the solvent removed under vacuum. The crude product was purified by flash chromatography on silica gel using a gradient elution with hexane: ethyl acetate (30-50% ethyl acetate).

(E)-3-(4-bromophenyl)-1-(3-methoxyphenyl)prop-2-en-1-one (25). A beige solid. Yield 75%. 1H-NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-D6) δ 7.94 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 1H), 7.86 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.76 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 7.70 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 1H), 7.65 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.60 (t, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 7.48 (t, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 7.24 (dd, J = 8.2, 2.7 Hz, 1H), 3.84 (s, 3H). 13C-NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-D6) δ 188.9, 159.6, 142.7, 138.9, 134.0, 131.9, 131.2, 131.2, 130.9, 130.0, 124.0, 122.9, 121.1, 119.3, 113.1, 55.4. ESI-MS [M+H]: Calculated for C16H13BrO2: 316.0; Observed: 317.0.

(E)-3-(4-chlorophenyl)-1-(3-methoxyphenyl)prop-2-en-1-one (26). A pale yellow solid. Yield 71%. 1H-NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-D6) δ 7.95 (d, J = 4.0 Hz, 2H), 7.93 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 2H), 7.77 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 7.73 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 1H), 7.61 (s, 1H), 7.53-7.52 (m, 1H), 7.49 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.25 (ddd, J = 8.2, 2.7, 0.8 Hz, 1H), 3.85 (s, 3H). 13C-NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-D6) δ 188.9, 159.6, 142.6, 138.9, 135.1, 133.6, 130.9, 130.7, 130.0, 129.0, 128.3, 122.8, 121.1, 119.3, 113.1, 55.4. ESI-MS [M+H]: Calculated for C16H13ClO2: 272.0; Observed: 273.0.

General Method for Pyrazolines Synthesis. Compounds 29, 31

To a solution of the appropriate chalcone (1 equiv.) in 25 mL of absolute ethanol, hydrazine monohydrate (2 equiv.) was added dropwise under stirring. The reaction mixture was heated at reflux for 6 – 8 h. The hot reaction mixture was then poured into a conical flask containing crushed ice. The crude white precipitate obtained was collected by filtration, washed with water, and dried. Products were recrystallised from ethanol.

2-(1',3'-diphenyl-3,4-dihydro-1'H,2H-[3,4'-bipyrazol]-5-yl)phenol (29). A yellow solid. Yield 64%. 1H-NMR (600 MHz, CHLOROFORM-D) δ 8.02 (s, 1H), 7.74-7.70 (m, 4H), 7.50-7.40 (m, 5H), 7.30-7.27 (m, 2H), 7.19 (dd, J = 7.7, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 7.02 (dd, J = 8.2, 1.0 Hz, 1H), 6.90-6.88 (m, 1H), 5.13 (t, J = 9.3 Hz, 1H), 3.58 (dd, J = 16.2, 10.3 Hz, 1H), 3.18 (dd, J = 16.2, 8.8 Hz, 1H). 13C-NMR (151 MHz, CHLOROFORM-D) δ 163.6, 154.1, 139.4, 136.2, 136.1, 132.2, 129.6, 129.4, 128.9, 128.8, 127.4, 127.1, 120.0, 119.4, 119.4, 118.7, 118.6, 118.2, 49.3, 41.9. ESI-MS [M+H]: Calculated for C24H20N4O: 380.1; Observed: 381.1.

2-(5-(4-bromophenyl)-4,5-dihydro-1H-pyrazol-3-yl)phenol (31). An off-white solid. Yield 68%. 1H-NMR (600 MHz, CHLOROFORM-D) δ 7.50-7.48 (m, 2H), 7.28-7.25 (m, 3H, overlapping with solvent residue signal), 7.15 (dd, J = 7.7, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 7.01 (dd, J = 8.2, 1.0 Hz, 1H), 6.88 (td, J = 7.5, 1.1 Hz, 1H), 4.88-4.85 (m, 1H), 3.58 (dd, J = 16.5, 10.7 Hz, 1H), 3.09 (dd, J = 16.5, 9.1 Hz, 1H). 13C-NMR (151 MHz, CHLOROFORM-D) δ 156.8, 152.8, 140.6, 131.1, 130.6, 130.4, 129.5, 127.7, 126.8, 120.7, 118.4, 115.8, 115.6, 61.3, 40.9. ESI-MS [M+H]: Calculated for C15H13BrN2O: 316.0; Observed: 317.0.

Antitubercular Screening

MIC Under Aerobic Conditions

The antimicrobial activity of compounds against Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv grown under aerobic conditions is assessed by determining the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of compound i.e., the concentration required to prevent growth. The assay is based on measurement of growth in liquid medium of a fluorescent reporter strain of H37Rv where the readout is either optical density (OD) or fluorescence. The use of two readouts minimizes problems caused by compound precipitation or autofluoresence. A linear relationship between OD and fluorescence readout has been established justifying the use of fluorescence as a measure of bacterial growth. MICs generated from the OD are reported in summary data. The strain has been fully characterized and is equivalent to the parental strain in microbiological phenotypes and virulence.

Protocol

The MIC of compound was determined by measuring bacterial growth after 5 d in the presence of test compounds. Compounds were prepared as 10-point two-fold serial dilutions in DMSO and diluted into 7H9-Tw-OADC medium (recipe: 4.7 g/L 7H9 base broth, 0.05% w/v Tween 80,10% v/v OADC supplement) in 96-well plates with a final DMSO concentration of 2%. Each plate included assay controls for background (medium/DMSO only, no bacterial cells), zero growth (100 µM rifampicin) and maximum growth (DMSO only), as well as a rifampicin dose response curve. Plates were inoculated with M. tuberculosis and incubated for 5 days: growth was measured by OD590 and fluorescence (Ex 560/Em 590) using a BioTek™ Synergy H4 plate reader. Growth was calculated separately for OD590 and RFU. A dose response curve was plotted as % growth and fitted using the Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm. Concentrations that resulted in 50% and 90% inhibition of growth were determined (IC50 and IC90 respectively). Raw data is provided and can be used to plot either type of curve.

Antiproliferative Evaluation In Vitro

The cytotoxicity of compounds towards eukaryotic cells was determined using human liver cells (HepG2), non-tumorigenic human mammary epithelial cells (MCF-10A), and breast cancer cells (MDA-MB-468).

HepG2 Cytotoxicity Screening

HepG2 cells were incubated with compounds for 72 hours in medium containing either glucose or galactose and cell viability was measured. The IC50 was determined as the concentration of compound causing a 50% decrease in viable cells after 72h. Compounds were prepared as 10-point three-fold serial dilutions in DMSO. The highest concentration of compound tested was 100 µM where compounds were soluble in DMSO at 10 mM. For compounds with limited solubility, the highest concentration was 50× less than the stock concentration, e.g., 100 µM for 5 mM DMSO stock, 20 µM for 1 mM DMSO stock. HepG2 cells were cultured in complete DMEM (recipe: DMEM medium, 1X penicillin-streptomycin solution, 2 mM Corning Glutogro supplement, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 10% v/v Fetal Bovine Serum), inoculated into 384-well assay plates and incubated for 24 h at 37oC, 5% CO2. Compounds were added and cells were cultured for a further 72 h. The final DMSO concentration was 1%. Cell viability was determined using the CellTiter-Glo® Luminescent Cell Viability Assay (Promega) and measuring relative luminescent units (RLU). The dose response curve was fitted using the Levenberg–Marquardt algorithm. The IC50 was defined as the compound concentration that produced 50% decrease in viable cells. Each run included staurosporine as a control.

MCF-10A and MDA-468 MTT Cytotoxicity Screening

Cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Virginia, USA). MDA-468 cells were grown in RPMI-1640 medium with 10% (v/v) heat inactivated foetal calf serum and L-glutamine (2 mM) without phenol red. MCF-10A cells were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium/ Ham’s F-12 medium (1:1) with 5% (v/v) heat inactivated foetal calf serum, epidermal growth factor (20 ng/mL), insulin (10 µg/mL) and hydrocortisone (500 ng/mL). Cells were maintained at 37°C, 5% CO2 / 95% air with 100% humidity and passaged every 2-3 days using trypsin EDTA solution (0.25% w/v). Adhered cells at sub confluence were harvested for experimental use. The medium was aspirated and discarded and trypsin-EDTA solution (1% w/v, 1 mL) was added to the cells. After 30 seconds this was aspirated and immediately replaced by a further 1 mL of trypsin-EDTA solution. The cells were incubated at 37°C for approximately 5 mins or until the cells were visibly non-adherent. The resultant cell suspension was placed in a 25 mL sterile universal container with 10 mL of fresh medium followed by centrifugation (3 min, 3000 rpm and 4°C). Old medium was aspirated and replaced with 10 mL of fresh medium. To determine the density of cells in suspension, an aliquot (100 µL) was added to a trypan-blue solution (0.4% w/v, 100 µL) and the number of viable cells determined using a Neubauer haemocytometer. The cell suspension was diluted with relevant medium to give a cell count of 2×103 cells per ml. Aliquots (100 µL) were dispensed into sterile 96-well microtitre flat-bottomed plates. For the MDA-468 and MCF-10A cell lines the plates were incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2/95% air with 100% humidity for 24 hours prior to the addition of test compounds. Test compounds were added within 30 mins into the wells from a 100 mM stock solution in DMSO and serially diluted to give final concentrations of 100, 30, 10, 3, 1, 0.1, 0.93, 0.01, 0.003, 0.001 and 0.0003 µM. The final concentration of DMSO did not exceed 0.1% v/v in each well. The cells were allowed to grow for 96 h at 5%, CO2, 37°C to give 80-90% confluence in the control wells after which 50 µL of MTT (3-[4, 5 dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2, 5- diphenyl tetrazolium bromide, 2mg mL-1) in sterile phosphate buffer was added to each well and the plates were further incubated for 2 h. All medium was aspirated, and the formazan precipitate generated by viable cells was solubilised by 150 µL of DMSO. All the plates were vortexed and the absorbance at 540nm was determined using a Molecular Devices SpectraMax M5 plate reader. Results were expressed as a percentage of the control value versus the negative logarithm of the molar drug concentration range using Graph Pad Prism. Relative toxicities of each compound within each cell line were expressed as 50% of growth inhibition (IC50). All determinations were carried out in quadruplicate.

References

- World Health Organization, Global tuberculosis report 2023, World Health Organization 2023.

- Riaz, S.; Iqbal, M.; Ullah, R.; Zahra, R.; Chotana, G.A.; Faisal, A.; Saleem, R.S.Z. , Bioorg. Chem. 2019, 87, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, H.U.; Xu, Y.; Ahmad, N.; Muhammad, Y.; Wang, L. , Bioorg. Chem. 2019, 87, 335–365. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain, M.; Das, U.; Dimmock, J.R., Eur. , Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 183, 111687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Go, M.L.; Wu, X.; Liu, X.L., Curr. , Curr. Med. Chem. 2005, 12, 483–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, N.J.; Patterson, R.P.; Ooi, L.; Cook, D.; Ducki, S. , Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006, 16, 5844–5848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducki, S.; Forrest, R.; Hadfield, J.A.; Kendall, A.; Lawrence, N.J.; McGown, A.T.; Rennison, D. , Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1998, 8, 1051–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elias, D.W.; Beazely, M.A.; Kandepu, N.M. , Curr. Med. Chem. 1999, 6, 1125. [Google Scholar]

- Mezgebe, K.; Melaku, Y.; Mulugeta, E., ACS omega 2023.

- Mahapatra, D.K.; Bharti, S.K.; Asati, V., Eur. , Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 101, 496–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhaliwal, J.S.; Moshawih, S.; Goh, K.W.; Loy, M.J.; Hossain, M.S.; Hermansyah, A.; Kotra, V.; Kifli, N.; Goh, H.P.; Dhaliwal, S.K.S. , Molecules 2022, 27, 7062. [CrossRef]

- Ruparelia, K.C.; Zeka, K.; Ijaz, T.; Ankrett, D.N.; Wilsher, N.E.; Butler, P.C.; Tan, H.L.; Lodhi, S.; Bhambra, A.S.; Potter, G.A. , Medicinal Chemistry 2018, 14, 322-332. [CrossRef]

- Hsu, Y.; Kuo, P.; Lin, C., Life Sci. 2005, 77, 279-292.

- Guo, J.; Liu, D.; Nikolic, D.; Zhu, D.; Pezzuto, J.M.; van Breemen, R.B. , Drug Metab. Disposition 2008, 36, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, E.; Zhang, K.; Cheng, L.Y.; Mack, P. , Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1998, 245, 435–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrapu, V.K.; Chaturvedi, V.; Singh, S.; Singh, S.; Sinha, S.; Bhandari, K., Eur. , Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 46, 4302–4310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takate, S.J.; Shinde, A.D.; Karale, B.K.; Akolkar, H.; Nawale, L.; Sarkar, D.; Mhaske, P.C. , Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2019, 29, 1199–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Flavin, M.T.; Zhou, L.; Nie, W.; Chen, F. , Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2002, 10, 2795–2802. [Google Scholar]

- Sivakumar, P.M.; Babu, S.K.G.; Mukesh, D. , Chemical and pharmaceutical bulletin 2007, 55, 44-49.

- Gomes, M.N.; Braga, R.C.; Grzelak, E.M.; Neves, B.J.; Muratov, E.; Ma, R.; Klein, L.L.; Cho, S.; Oliveira, G.R.; Franzblau, S.G. , Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 137, 126–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, M.; Chaturvedi, V.; Manju, Y.K.; Bhatnagar, S.; Srivastava, K.; Puri, S.K.; Chauhan, P.M., Eur. , Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 44, 2081–2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiaradia, L.D.; Martins, P.G.A.; Cordeiro, M.N.S.; Guido, R.V.C.; Ecco, G.; Andricopulo, A.D.; Yunes, R.A.; Vernal, J.; Nunes, R.J.; Terenzi, H., J. , J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 390–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anandam, R.; Jadav, S.S.; Ala, V.B.; Ahsan, M.J.; Bollikolla, H.B. , Medicinal Chemistry Research 2018, 27, 1690-1704. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.A.; Kaskhedikar, S.G. , Medicinal Chemistry Research 2013, 22, 3863-3880.

- Horley, N.J.; Beresford, K.J.; Chawla, T.; McCann, G.J.; Ruparelia, K.C.; Gatchie, L.; Sonawane, V.R.; Williams, I.S.; Tan, H.L.; Joshi, P., Eur. , Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 129, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horley, N.J.; Beresford, K.J.; Kaduskar, S.; Joshi, P.; McCann, G.J.; Ruparelia, K.C.; Williams, I.S.; Gatchie, L.; Sonawane, V.R.; Bharate, S.B. , Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2017, 27, 5409–5414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhambra, A.S.; Ruparelia, K.C.; Tan, H.L.; Tasdemir, D.; Burrell-Saward, H.; Yardley, V.; Beresford, K.J.; Arroo, R.R., Eur. , Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 128, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shyam, M.; Verma, H.; Bhattacharje, G.; Mukherjee, P.; Singh, S.; Kamilya, S.; Jalani, P.; Das, S.; Dasgupta, A.; Mondal, A., J. , J. Med. Chem. 2022, 65, 234–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trott, O.; Olson, A.J. , Journal of computational chemistry 2010, 31, 455-461.

- Jones, G.; Willett, P.; Glen, R.C.; Leach, A.R.; Taylor, R., J. , J. Mol. Biol. 1997, 267, 727–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murnane, R.; Zloh, M.; Tanna, S.; Allen, R.; Santana-Gomez, F.; Parish, T.; Brucoli, F. , Bioorg. Chem. 2023, 138, 106659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazzaniga, G.; Mori, M.; Meneghetti, F.; Chiarelli, L.R.; Stelitano, G.; Caligiuri, I.; Rizzolio, F.; Ciceri, S.; Poli, G.; Staver, D., Eur. , Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 234, 114235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).