Introduction

Different reading strategies have been researched with many different groups of participants, but no known research has evaluated reading strategies employed by different groups of English for Specific Purposes (ESP) students. Differences in reading strategies could potentially influence teaching effectiveness, learning outcomes, and English language applications. Many studies have been conducted in relation to ESP and specifically to what students need to do in their vocations or jobs (Harding, 2012). Likewise, many studies have focused on reading strategies, however, no known studies have compared reading strategies among Spanish speaking students in different programs of ESP.

Therefore, the key research question was: Do Spanish speaking university students in various programs of English for Specific Purposes differ in their reading strategies and if there are any differences in their reading strategies, what are those specific differences? The answer to this research question is important because such information could be valuable in helping such specialized programs to be more effective and efficient in teaching students specific skills and for helping teachers to be more precise and effective in their teaching. Additionally, this area of inquiry is also significant because it could help students to learn more efficiently and to utilize reading concepts and strategies more effectively in the area of applied English for Specific Purposes.

Review of the Literature

Research has found that students often vary in the reading strategies they use to learn. The key question is whether such variance is also occurring with ESP students, independent of their knowledge of general English. In the following section, reading, metacognitive strategies, and ESP are briefly reviewed.

Reading

Reading is the ability or activity of reading materials. This activity can be performed silently or audibly verbalized. Reading is a mechanism for assisting in the transmission of information immediately and over time.

Fuchs, Fuchs, and Hosp (2001) found that younger learners tend to demonstrate larger learning increases than older learners and, this was also found in a study documented by Dixon (2012). Additionally, Fuchs, Fuchs, and Hosp (2001) and Reece, Garnier, and Gallimore (2000) found that students who read aloud tended to learn more and retain more information. Fuchs, Fuchs, and Hosp study reviewed oral reading fluency as an indicator of reading competence and provided a theoretical, empirical, and historical analysis “of the extent to which oral reading fluency has been incorporated into measurement approaches during the past century.” (2001:240)

The study also included specific recommendations regarding the assessment of oral reading fluency for applications with research and applied practice. The key aspects of the research found that younger students did much better in correlating better oral reading fluency and academic performance while older adults were less likely to demonstrate such positive academic performance. Additionally, the study found that correlations for oral reading fluency were substantially higher and statistically significantly higher than for silent reading fluency scores.

Research conducted by Crawford, Tindal, and Stieber, S. (2001) found that students who practiced reading and writing at home and in the classroom demonstrated better academic performance. The study found that students who wrote more tended to demonstrate better academic performance and students who read more tended to demonstrate better academic performance. These research findings were also documented by Baker, Scher, and Mackler (1997).

The later study used a curriculum-based measurement (CBM) to predict student performance on Oregon statewide reading and math achievement tests. The students read aloud from descriptive passages and the results indicated support for the timed oral readings as a predictor for performance on the tests. The strength of this study is that the research was conducted longitudinally with comprehensive testing procedures and with strong teacher administrative assistance.

Several studies have attempted to provide more precise measures of reading strategy activities. Research that includes need assessment and evaluation such as the one carried out by Basturkmen (2010) found that such activities produce better results and outcome. The research of Basturkmen (2010) focused on real world applications with police officers and with physicians while Edwards (2000) had similar finding with bankers. Arani (2004) also found similar results with second year medical students and ESP learning while Sevilla-Pavon, Serra-Camara, and Gimeno-Sanz, (2012) found the same outcomes with aerospace engineers.

English for Specific Purposes (ESP)

According to Harding (2012) ESP relates directly to what students need to do in their vocations or jobs. Harding (2012) believes that ESP is important because it helps to increase vocational learning and training throughout the world. As globalization is spreading, Harding states that knowledge of English has become the major need. “It’s not just the politician, the business leader, and the academic professor who need to speak to international colleagues and clients: “it’s also the hotel receptionist, the nurse, and the site fireman” (Harding, 2012, p. 7). Anthony (1998) has suggested that ESP can be, but not necessarily be, concerned with a specific discipline and it does not have to be focused on a specific ability range or particular age group. Rather, Anthony suggests that ESP can be viewed as an approach to teaching.

Basturkmen (2006) has indicated two distinct perspectives regarding language for specific purposes. One perspective suggests that English has a common foundation of words of which all learners should know. The other perspective suggests that all language is already for specific purposes, and therefore, specialization must begin at an early age.

Whether specialization begins early or late in the life of an individual, Read (2007) has found that there are numerous methods of identifying vocabulary for specific purposes. However, Read has further noted that there is a lack of a systematic way of identifying vocabulary for specific purposes. The lack of such a systematic methodology could have caused variations in outcomes. Therefore, these variations may have caused many researchers to produce very different and unique conclusions in their research findings.

In terms of theoretical background some researchers have suggested that ESP is just technical vocabulary. Other researchers have suggested that ESP is more than technical vocabulary and that it is important to understand that vocabulary is an important part of any ESP course. Harding (2012) states that partly this is because specific technical words are used to describe particular features of the vocabulary specialization and that teaching, and vocabulary development are on-going processes. These concerns are important to this particular research study because much of the study of ESP is based on definitions of technical words and vocabulary, which may be perceived to be perceptually different in different countries and cultures.

Characteristics of ESP

Belcher (2006) addressed the global features of ESP and potential cultural differences. ESP usually includes Technical English, Medical English, Business English, Aviation English, and other English areas. Tony Dudley-Evans (1997); has suggested that the field should be viewed from a set of “absolute” and “variable” characteristics. Dudley-Evans built upon the work of Strevens (1988); and Johns and Dudley-Evans in relation to general English had developed the following characteristics:

Absolute Characteristics

1) ESP is defined to meet specific needs of the learners.

2) ESP makes use of underlying methodology and activities

3) ESP is centered on the language appropriate to these activities in terms of grammar, lexis, register, study skills, discourse, and genre.

Variable Characteristics

1) ESP may be related to or designed for specific disciplines.

2) ESP may be used in specific teaching situations and with a different methodology from that of General English.

3) ESP is likely to be designed for adult learners, either at a tertiary level institution or in a professional work situation. It could, however, be for learners at secondary school level.

4) ESP is generally designed for intermediate or advanced students.

5) Most ESP courses assume some basic knowledge of the language systems.

(Dudley-Evans, 1997:101)

ESP itself has gone under a process of development, as Hutchinson & Alan Waters noted, “From its early beginnings in the 1960, ESP has undergone five main phases of development including the concept of special languages, rhetorical or discourse analysis, target situation analysis, skills and strategies, and learning centered approach” (2003:9)

ESP Vocabulary

Another important area of ESP is the issue of vocabulary, and the kind of vocabulary learners need. From this area of vocabulary, consideration is usually made regarding specialized vocabulary. Nation (2008:10) has suggested that most technical vocabularies have about one thousand to five thousand words depending on the subject area, which can be learned at almost any age.

Some researchers have suggested that ESP is just technical vocabulary. Other researchers have suggested that ESP is more than technical vocabulary and that it is important to understand that vocabulary is an important part of any ESP course. Harding (2012) states that partly this is because specific technical words are used to describe particular features of the vocabulary specialization and that teaching, and vocabulary are on-going processes.

In order to address target knowledge, ESP has to include “authentic discourse, vocabulary and situation” used in the context where learners will apply their knowledge (Chalikandy, 2001). For example, Gatehouse (2001) suggested that the proper use of occupational jargon is absolutely necessary to perform an effective needs analysis relative to the specific occupational context.

Klimova (2015) suggests that to develop vocabulary materials for an ESP course, teachers must be authentic in showing students how to use English in real world situations and that ESP practitioners must remember that ESP students need to use English to fulfill their discipline-specific real-world tasks. As Frendo (2005) has noted, the teacher must give careful preparation relative to the knowledge and experience of the students. For example, Frendo observed that in most other fields of teaching the teacher knows more about the subject than the learner, but in business English the relationship can be more symbiotic where the teacher knows about language and communication, but the learner often knows more about the job and its content.

Reading Strategies

Research has attempted to produce better understanding about how reading strategies can impact different types of learning programs such as in ESP programs. Such research has limited availability, but the significance of this type of research is very important.

In regards to reading strategies, Olszak (2016) performed an investigation into the use of reading strategies among students of dual language programs at selected Polish universities. Olszak noted that O’Malley and Chamot (1990:1) found that “language learning strategies are the special thoughts or behaviors that individuals use to help them comprehend, learn or retain new information.” (2016:5) Olszak further noted that O’Malley and Chamot used three category learning strategies, which included cognitive, metacognitive, and social/affective strategies with subcategories under each main category. Olszak utilized the initial works of O’Malley and Chamot (1960) to develop her categories. These categories were also related to the applied aspects of reading strategies and they were: Organizing reading and planning, Actions undertaken while reading, Evaluation after reading, and Dealing with problems.

Olszak used this information to create and to minimize variance among grouping of students and their reading strategies. The resulting questions were the result of direct tabulation of student survey responses. A key aspect of that research was having sufficient numbers of reading strategies, but not too many reading strategies so as to confuse student responses. This approach also complemented the research of Cohen (1990) who divided strategies into two different types which were identified as language learning strategies and language use strategies and Anderson (1991) and Anderson (2003) who examined individual differences in strategy use in reading and testing for second language students.

Therefore, the final test items reflected the general frequency of student survey responses and explanations provided to researchers. This approach allowed the maximum number of responses to be tabulated and to be placed in the final survey while maximizing reliability and validity.

There were a minimum of fifteen reading strategies and five forms of training listed on the student surveys for which responses were tabulated and analyzed. Items were designed to allow for the maximum amount of participant responses through the selection format. Each survey took about fifteen minutes or less per student to complete.

Olszak then used the learning strategies of O’Malley and Chamot to evaluate metacognitive and cognitive reading strategies of dual language learners (DLLs). Olszak (2016) surveyed reading strategies among students of Dual Language Programs at selected Polish Universities. Olszak found that the “frequency of adopted strategies seem to be rather high.” (p.15) and “there are differences in the adoption of reading strategies between female” dual language learners. (p.15).

In regards to the broader picture of reading strategies and ESP, Martinez (2008) studied students’ metacognitive awareness of reading strategies using the Metacognitive Awareness of Reading Strategies Inventory (MARSI) (Mokhtari & Reichard, 2002). Martinez surveyed 157 English for Specific Purposes (ESP) university students who were students from a Faculty of Chemistry and the Technical School of Engineering at the University of Oviedo in Spain.

Martinez (2008) found a moderate to high overall use of reading strategies by ESP students and that students demonstrated a specifically higher reported use for problem-solving and global reading strategies. Additionally, the study found that female ESP students reported a significantly higher use of reading strategies and that these same female ESP students tended to utilize reading strategies much more frequently than male ESP students.

Later research conducted by Jafari and Shokrpour (2012) evaluated the reading strategies of Iranian ESP students to comprehend English expository texts. The research used the Survey of Reading Strategies (SORS) (Mokhtari & Sheorey, 2002) with 81 female and male sophomore ESP students who were studying midwifery, environmental health, and occupational health and safety at a university in Shiraz. The results of the study found that the ESP student participants were moderately aware of their own reading strategies and the most frequently used category of strategies was support strategies, then global strategies, and problem solving strategies. The study also found the ESP student participants utilized reading strategies differently based on their respective academic majors.

Research by Vaez Dalili and Tavakoli (2013) evaluated whether significant differences were found between 35 humanities EFL students and between 35 engineering in regards to metacognitive perceptions and utilization of particular reading strategies while these students were reading English for Specific Purposes (ESP) texts. These 70 students at the University of Isfahan in India completed the Metacognitive Awareness of Reading Strategies Inventory (Mokhtari & Reichard, 2002), which was used to measure the metacognitive awareness of ESP reading strategies with EFL students.

The results of the research study found that although there were two different groups of academic major areas of study, both groups displayed similar reading strategy awareness patterns and similar use of reading strategies while reading the ESP materials. The study also found that engineering ESP students more frequently used some types of reading strategies than did the humanities ESP students. The research study also suggested that the findings, “also help to challenge the purely speculative assumption as to the deficiencies in strategy-based ESP reading comprehension of humanities students.” (p. 63)

A research study by Poole (2009) evaluated whether there were significant differences in the use of reading strategies between Columbian university females (N=235) and Columbian university males (N=117) who completed the Survey of Reading Strategies or SORS (Mokhtari & Sheorey, 2002).

The results of the study found that the use of males’ overall reading strategies was moderate, “as was their use of half of their strategies (p. 1).” For females, the overall strategy utilization was high as was the female use of half of their own reading strategies. Finally, the study found that the overall reading strategies for females were significantly higher than that of the males. The research study also provided ideas for teaching strategies and for suggesting areas for future research.

Research by Amirian (2013) evaluated “the impact of teaching reading strategies on reading comprehension improvement of ESP readers. It also intended to find out whether there is any interaction between readers' proficiency level and the effectiveness of reading strategy training.” (p.19) The study used 60 sophomore ESP students who were studying geography at Hakim Sabzevari University in Iran, and they were randomly assigned to one of two equal sized groups. The control group received traditional reading instruction while the experimental group received training in reading strategies.

The results of the study found training ESP students in reading strategies was more effective than traditional reading instruction for improving the reading ability of ESP students. Additionally, the study found that training in reading strategies did not affect the reading ability of the ESP students who had different levels of reading proficiency. This research result also suggested that less proficient ESP readers could potentially benefit from additional training in reading strategies.

Method

For this survey research, four Ecuadorian universities were selected. Two of the universities were located in the Andean region of Ecuador and the other two universities were located in the Costa Region. These universities were selected in order to analyze and to establish a comparison of reading strategies among Spanish-speaking University students in four different ESP programs. The total population of students in the different English programs of the four universities selected was one thousand one hundred twenty two (1,122). From that population a sampling of ninety-seven (97) ESP students voluntarily completed the Olszak (2016) reading strategies survey.

The following list indicates the number of students who were voluntarily surveyed at the different programs of ESP at four universities in the country of Ecuador.

17 students in the Agriculture English Program at a public university in Guayaquil.

23 students in the Accounting and Business English Program at a private university in Guayaquil.

32 students in Business English program at a private university in Quito

25 students in the Medical English program at a public university in Riobamba.

Olszak (2016) developed a reading strategies survey using the responses of 98 dual language students at three different Polish universities who were asked to identify which reading strategies they applied while organizing their process of reading comprehension in the first and second foreign languages that they had studied. The items in the survey thematically include many recognized reading strategies used by learners. Olszak found the validity of her survey to be 80% and the reliability to be highly statistically significant (p=0,000; R =0,708) using R=Pearson's correlation coefficient.

Results

This research study examined the relationships of reading strategies among four different programs of English for Specific Purposes. A total of 97 students enrolled in four English for Specific Purposes (ESP) programs in two public universities and in two private universities in Ecuador were surveyed regarding their reading strategies.

There were a total of 65 items on the surveys completed by the 97 volunteer students in six reading strategy categories. Those six categories were: Organizing Reading and Planning, with the number of survey items to be seven.

Actions Undertaken While Reading, with the number of survey items to be 18.

Evaluation after Reading, with the number of survey items to be 11.

Dealing with Problems, with the number of survey items to be ten.

The following two categories asked for an answer of “yes and no”

- 4.

What kind of actions do you undertake in order to improve your reading skills / comprehension? The number of survey items was 15.

- 5.

Have you ever been engaged in any of the below mentioned forms of learner training? The number of survey items was four.

Key Research Question:

Are there significant statistical differences between the four ESP groups?

Table 1.

Summary of Participants.

Table 1.

Summary of Participants.

| Summary of Participants |

|---|

| A public university in Guayaquil |

17 |

18% |

| A private university in Guayaquil |

23 |

24% |

| A private university in Quito |

32 |

33% |

| A public university in Riobamba |

25 |

26% |

| TOTAL: |

97 |

00% |

A total of ninety-seven (97) ESP students were surveyed. Here are the numbers of students responding at each university: 17 surveys at a public university in Guayaquil, representing 18% of respondents, 23 surveys at a private university in Guayaquil, representing 24% of respondents, 32 surveys at a private university in Quito, representing 33% of respondents, and 25 surveys at a public university in Riobamba representing 26% of respondents.

Chi-Square Method

The use of the Chi-Square Method is a method for evaluating possible statistical differences among groups. The technological tool used to calculate the Chi-Square in this study was the VassarStats: Statistical Computation web site for which the URL was

www.vassarstats.net

For this study, all responses of the survey from the four questions categories were used. These responses are represented in the columns of the following table as: B1 (Organizing reading and planning), B2 (Actions undertaken while reading), B3 (Evaluating after reading), and B4 (Dealing with problems). For the rows, the five possible answers were A1 (never), A2 (rarely), A3 (sometimes), A4 (usually), and A5 (Always).

This study presented variables called First Language and Second Language and the responses were calculated using a separate contingency table. Those results are presented below.

First Language

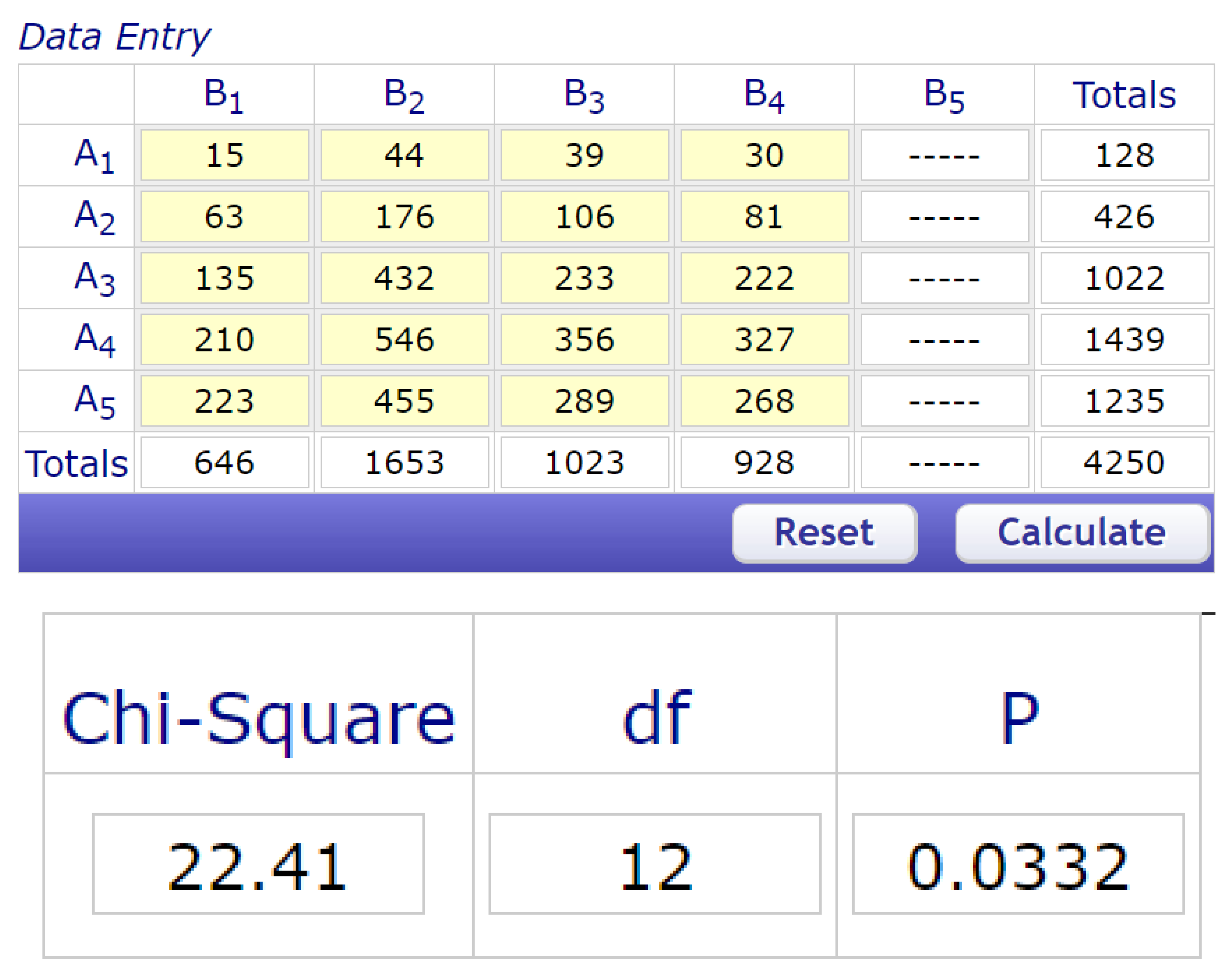

For first language the value of P is: 0.0332, which was lower than 0.5 and the study finding was that the reading strategies used by the first language group were significantly different.

Table 2.

Chi-Square for First Language.

Table 2.

Chi-Square for First Language.

Second Language

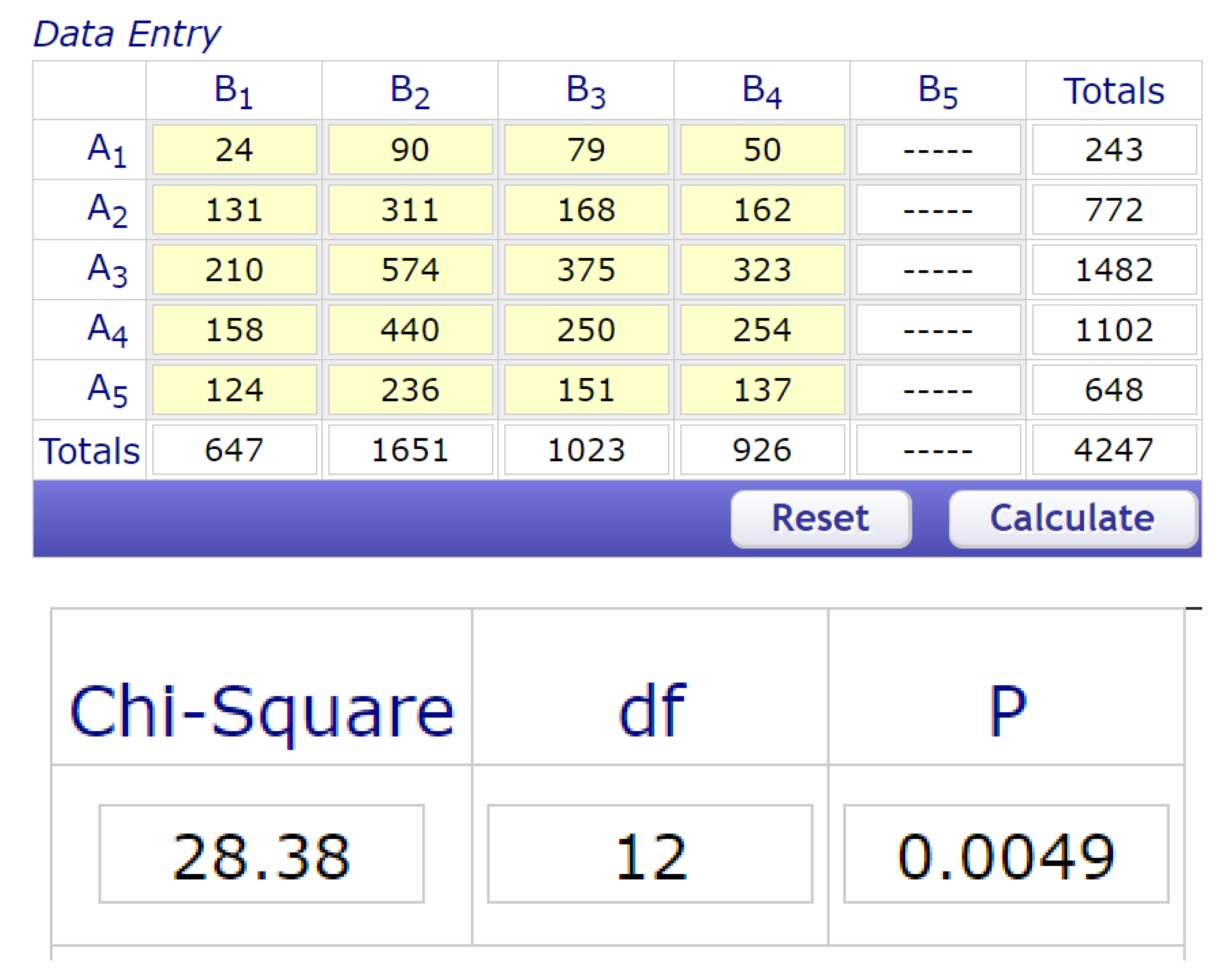

For the second language the value of P is: 0.0049, which was lower than 0.5 and the study finding was that the reading strategies used by the second language group were significantly different.

Table 3.

Chi-Square for Second Language

Table 3.

Chi-Square for Second Language

Chi-Square by Groups of Answers in the Survey

In order to evaluate potential differences between ESP groups, chi-square was calculated by groups of questions answered in the survey. Column (B) represents the values of the results for each university and row (A) represents the values for the variables from “never to always”.

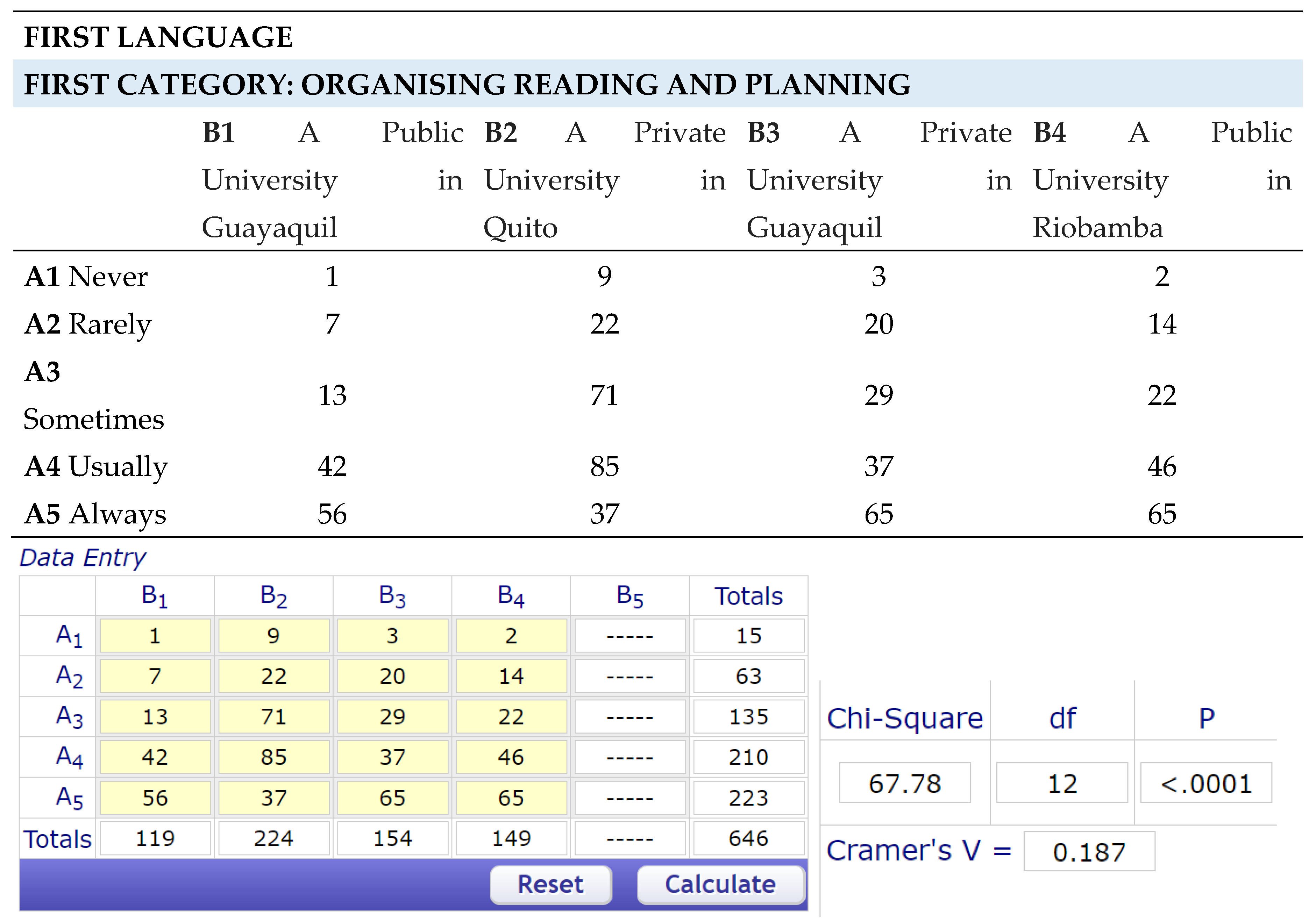

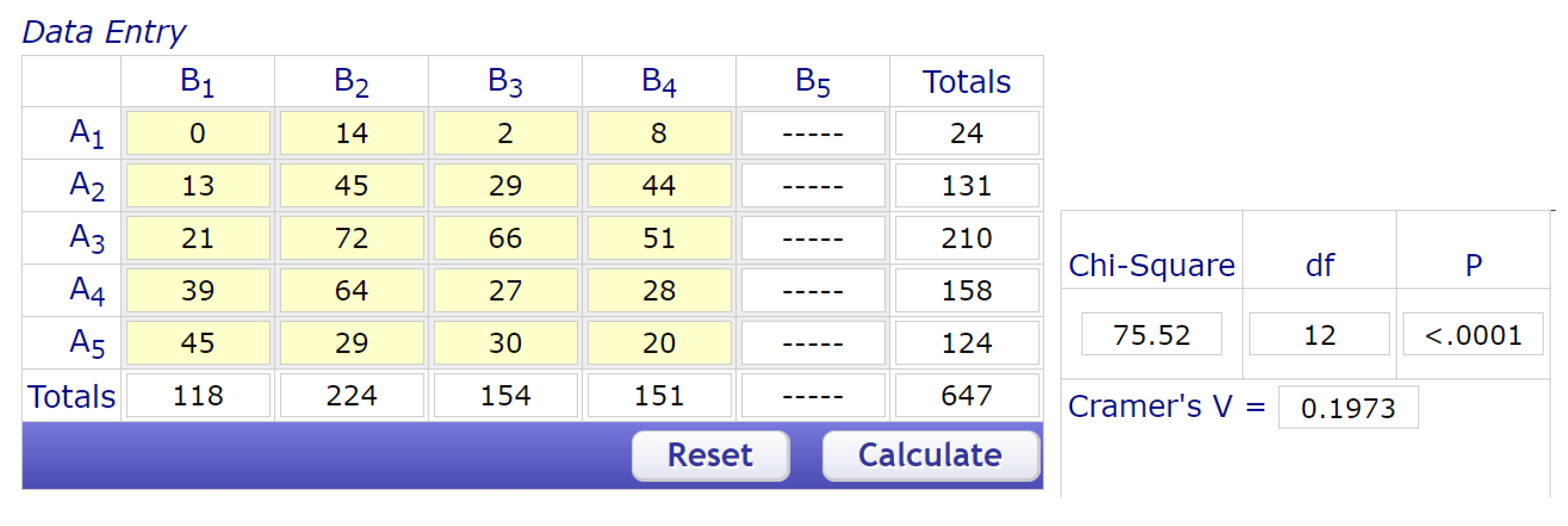

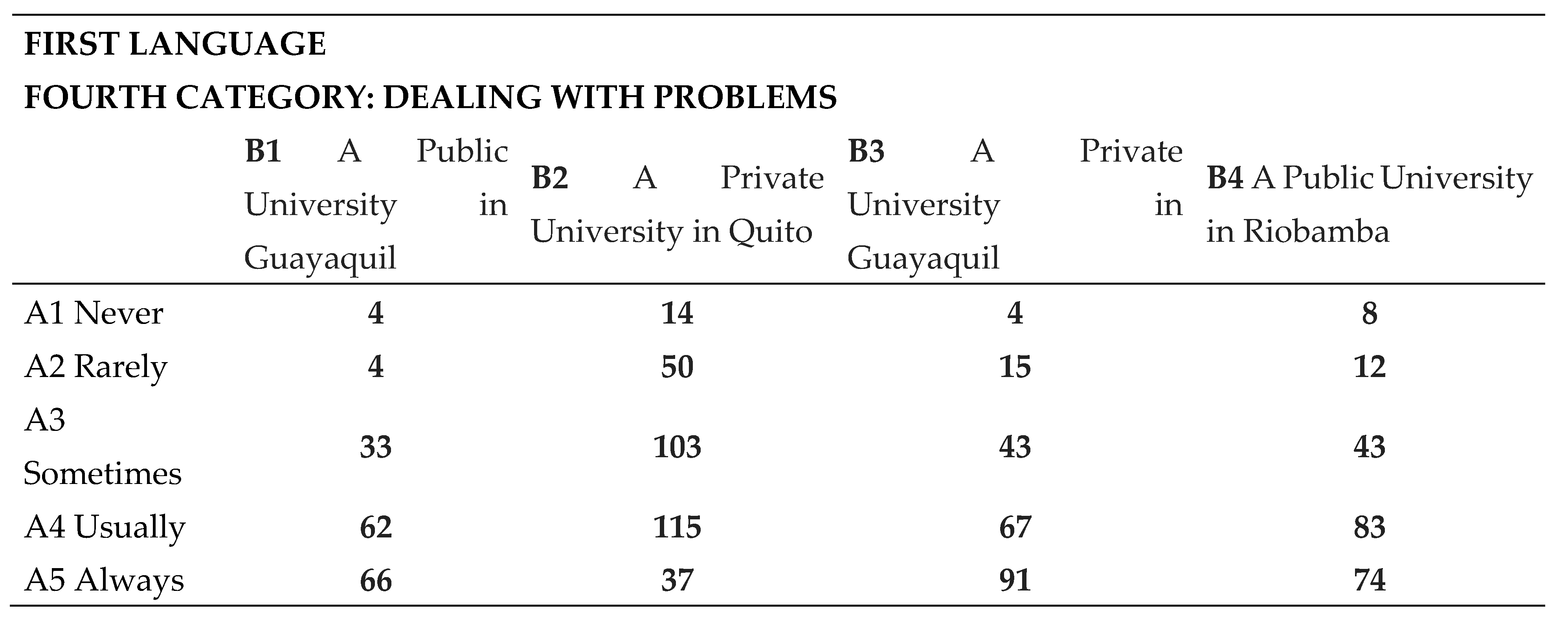

First Category: Organizing Reading and Planning

Table 4.

Chi-Square for First Language – First Category.

Table 4.

Chi-Square for First Language – First Category.

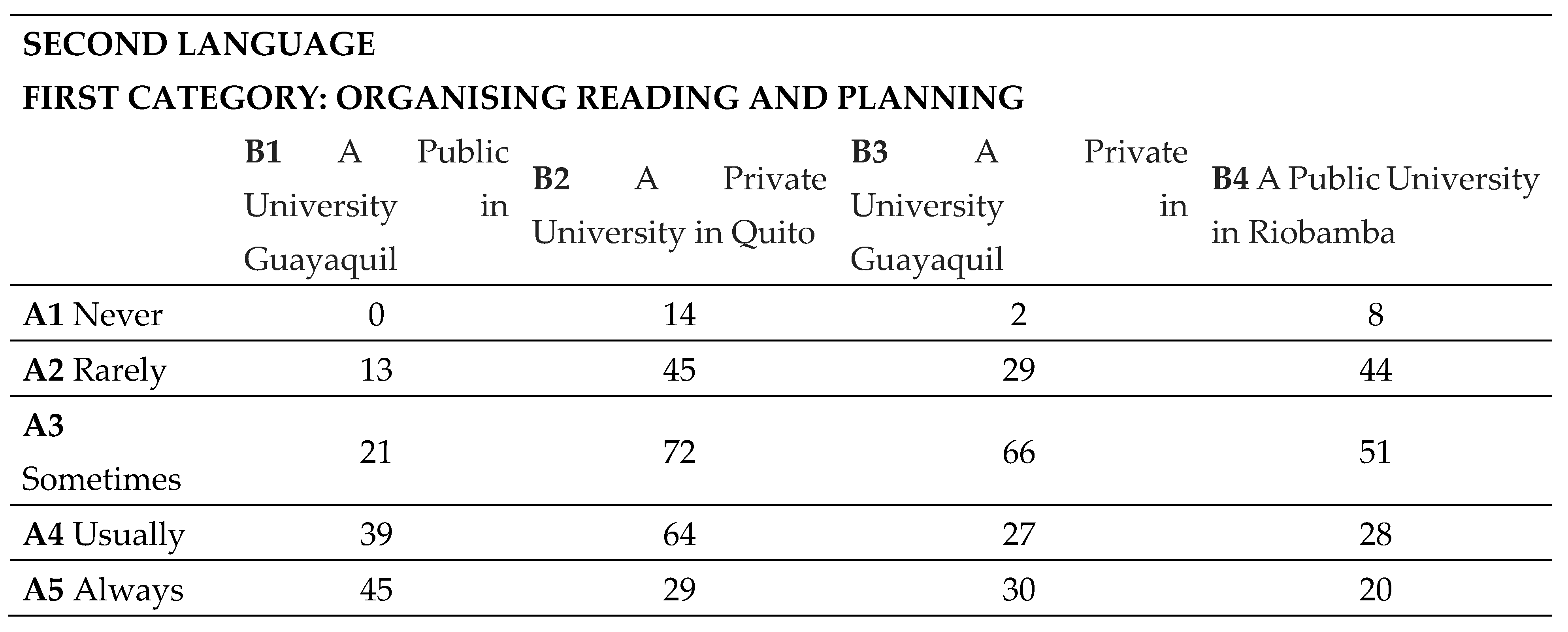

Table 5.

Chi-Square for Second Language – First Category.

Table 5.

Chi-Square for Second Language – First Category.

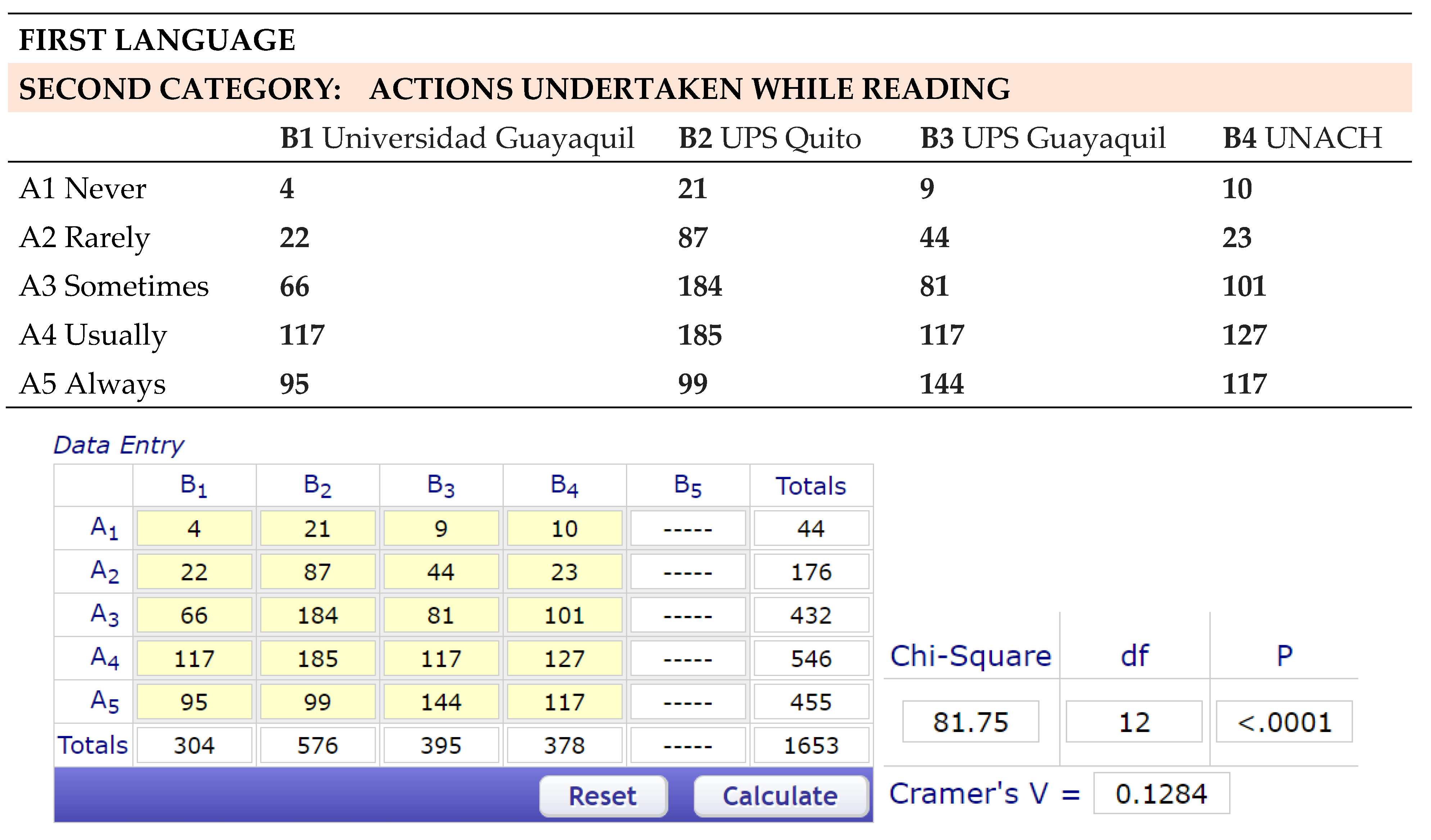

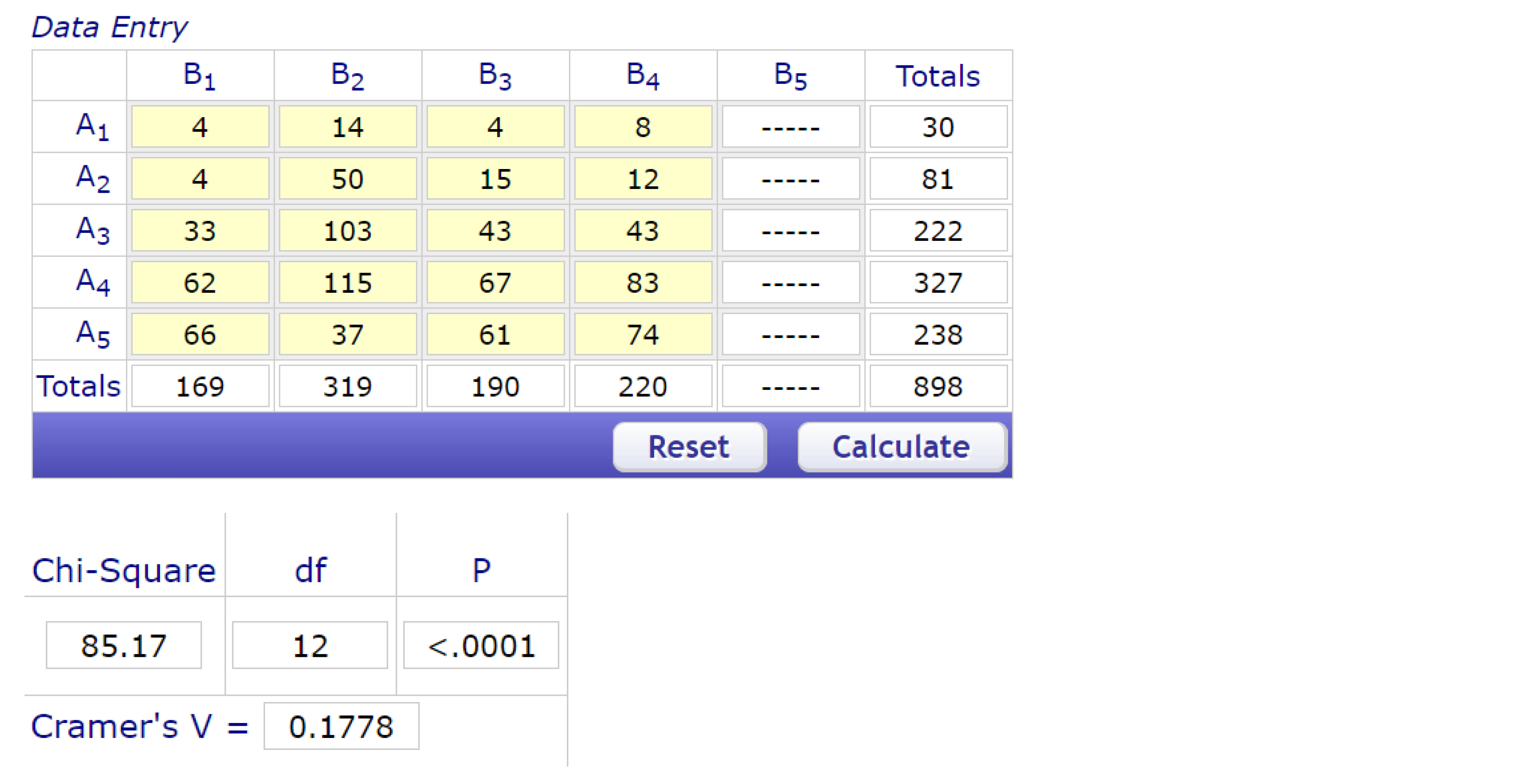

Second Category: Actions Undertaken While Reading

Table 7.

Chi-Square for First Language – Second Category.

Table 7.

Chi-Square for First Language – Second Category.

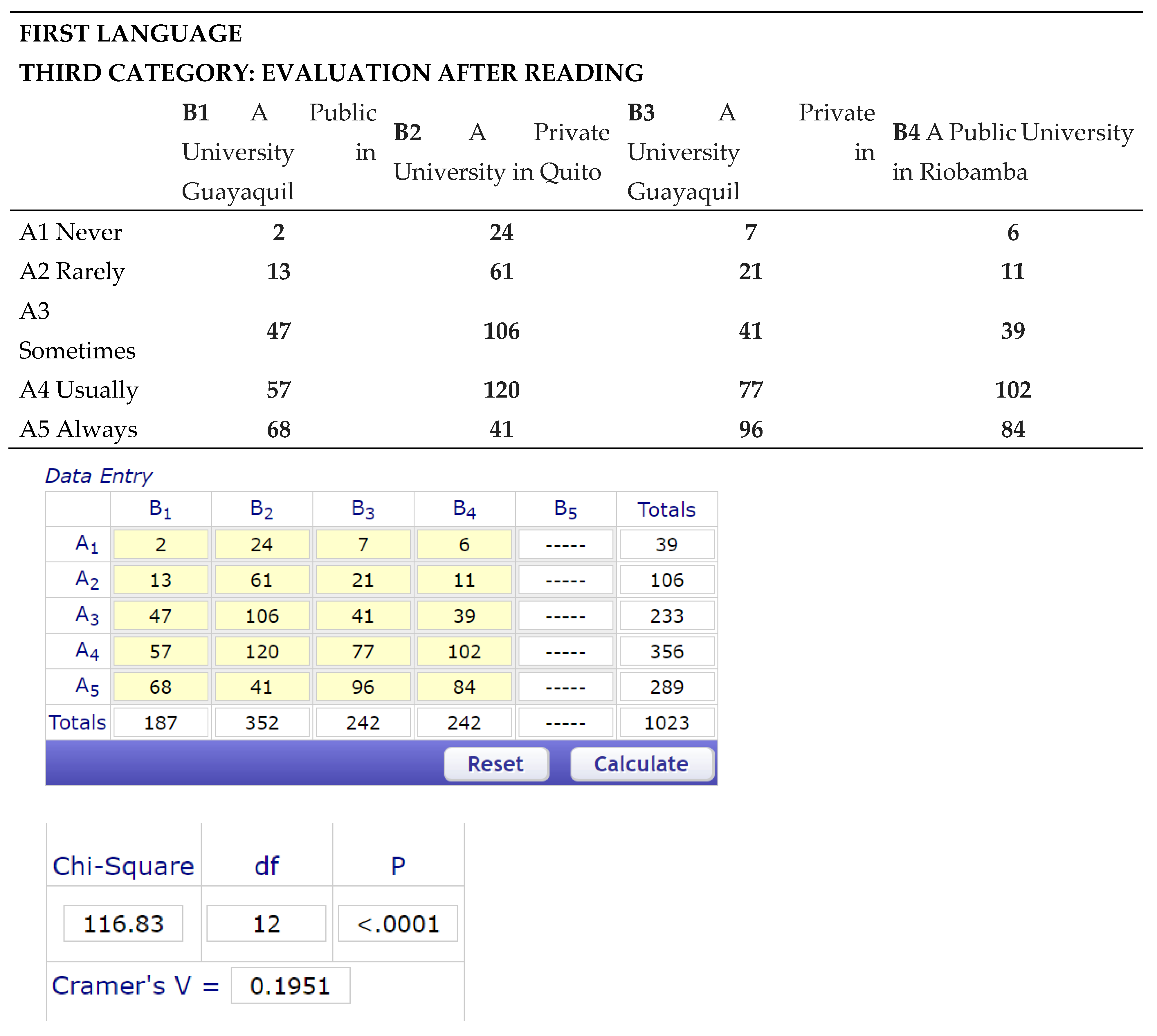

Table 8.

Chi-Square for Second Language – Second Category.

Table 8.

Chi-Square for Second Language – Second Category.

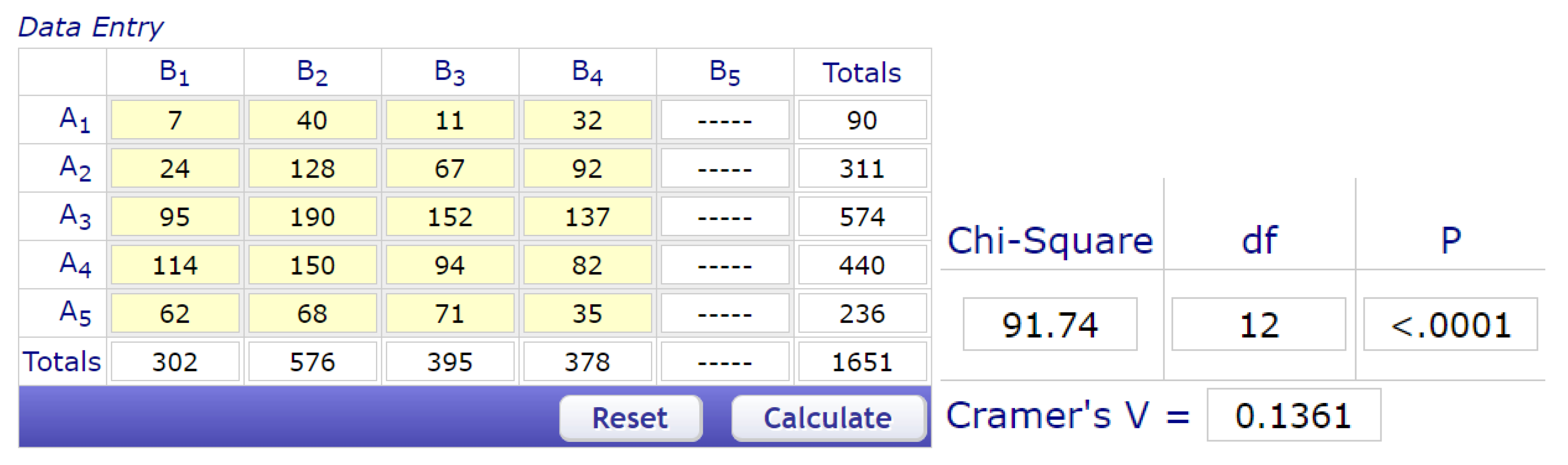

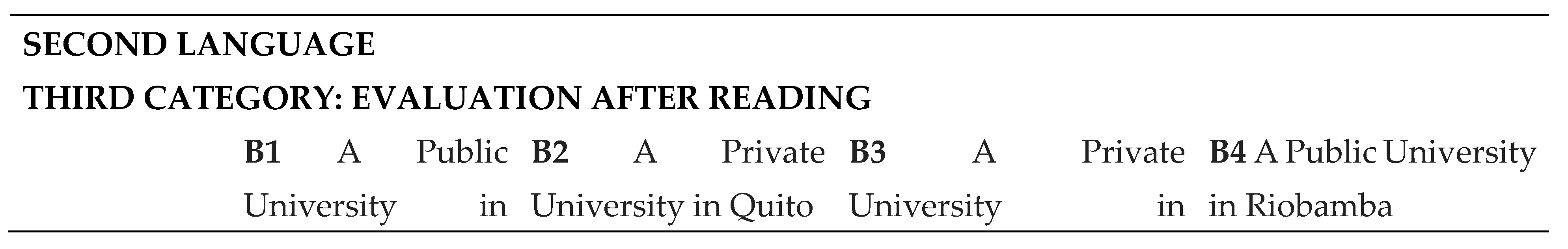

Third Category: Evaluation after Reading

Table 9.

Chi-Square for First Language - Category Three.

Table 9.

Chi-Square for First Language - Category Three.

Table 10.

Chi-Square for Second Language - Category Three.

Table 10.

Chi-Square for Second Language - Category Three.

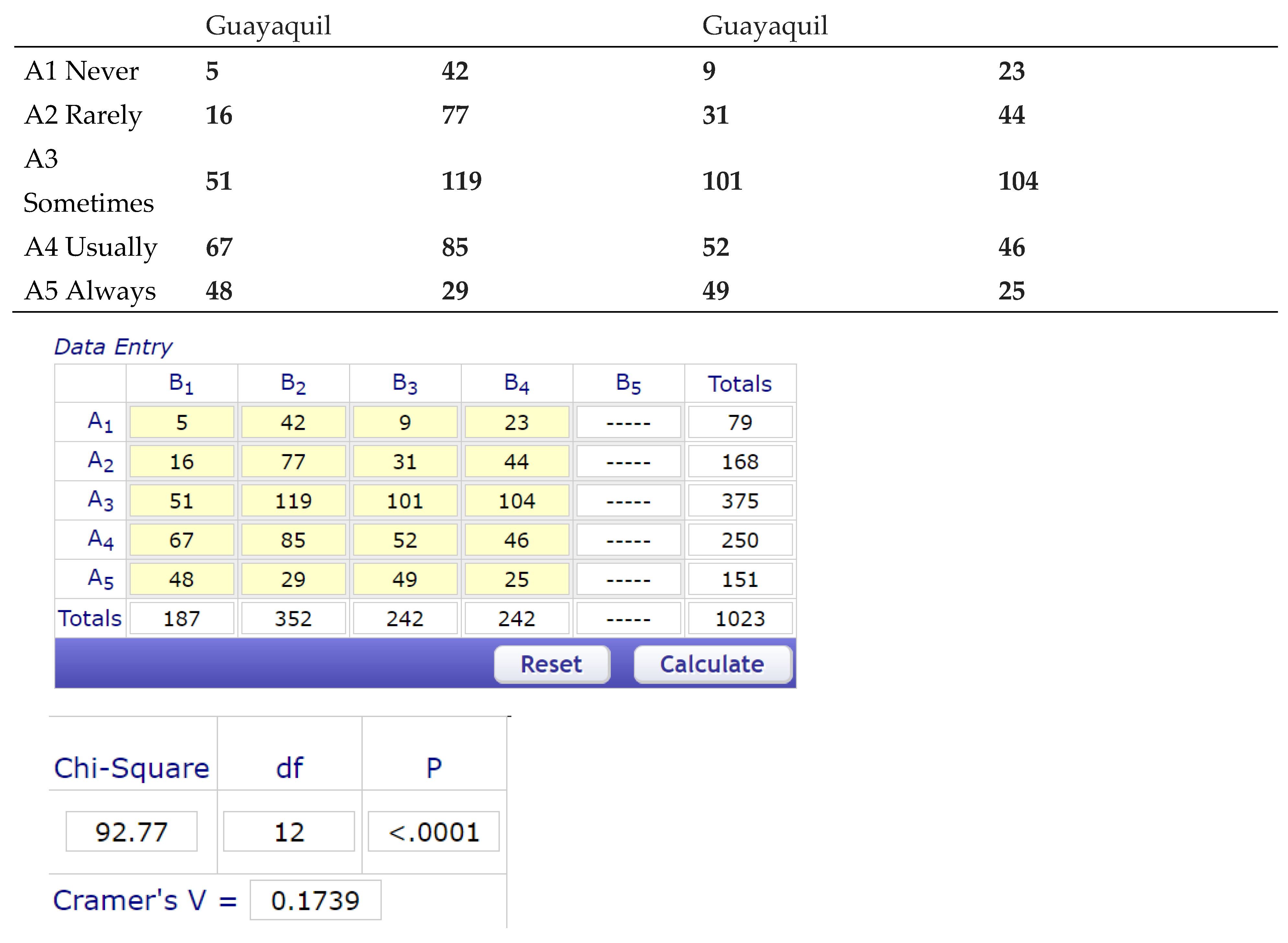

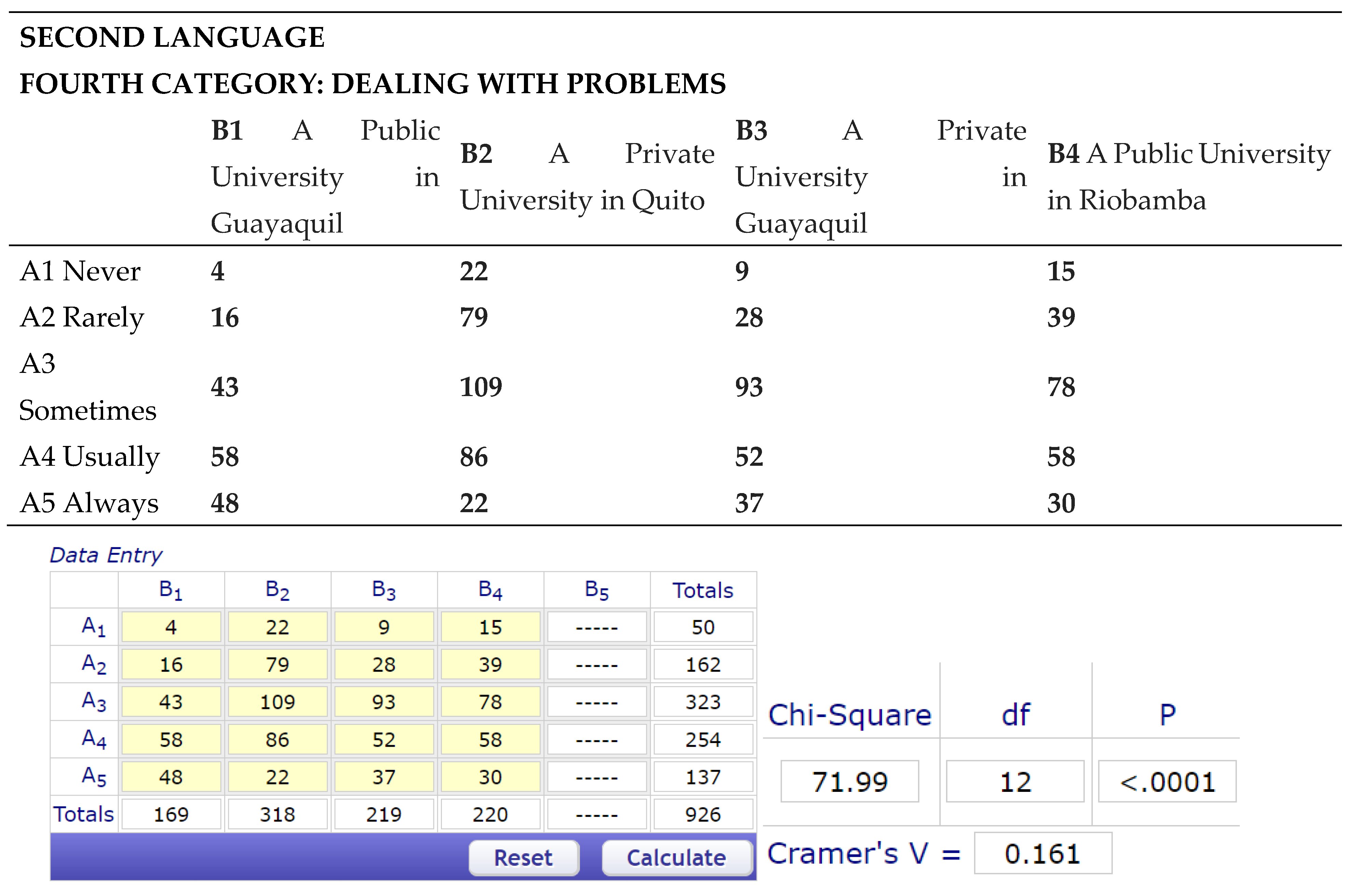

Fourth Category: Dealing with Problems

Table 11.

Chi-Square for First Language - Category Four.

Table 11.

Chi-Square for First Language - Category Four.

Table 12.

Chi-Square for Second Language - Category Four.

Table 12.

Chi-Square for Second Language - Category Four.

Discussion

As previously noted, the current study found that there were significant differences in reading strategies among students of the four different university programs of ESP. Therefore, such differences in findings should cause researchers to ask this question: why do such differences exist among the four different university programs of ESP?

On the surface, such differences could be the result of different teaching methodologies among the four programs of ESP. Such differences could also be the result of different previous student instruction and different student educational backgrounds before the students enrolled in the four university programs of ESP. Additionally, such differences could be a combination of differing teaching methodologies, differing previous student instruction, and differing student educational backgrounds. Unfortunately, the current research does not provide any clear or exact reasons to explain why such statistically significant differences were found among the reading strategies of the students enrolled in the four university programs of ESP.

Now that the current research study has determined that differences in reading strategies do exist among the four university programs of ESP, it is logical to suggest that future research in this area of inquiry needs to control the possible factors of differing teaching methodologies, differing previous student instruction, and differing student educational backgrounds. Additionally, such future research investigations should include larger numbers of students in order to clarify any other sources of potential differences in reading strategies among students who are enrolled in university programs of ESP.

The results of the current study indicate differences in reading strategies among four university programs of ESP while raising questions of why such differences exist and asking questions regarding potential implications as a consequence of the research findings. Clearly, the immediate implication of such differences in reading strategies suggests that ESP program administrators need to examine carefully and to evaluate their ESP programs on a continuous basis regarding reading strategies and their use among ESP students. These differences also suggest that ESP program administrators may need to have additional testing of reading strategies among their ESP students in order to define more precisely how to match instructional methodologies with variances in ESP student reading strategies.

These implications seem to also suggest that in terms of applied teaching significance, teachers may need to have a much deeper and better understanding of individual student reading strategies in order to help teachers to be more precise and more effective in their target teaching and reading strategies. Additionally, these implications also seem to suggest that students also need to have a much deeper and better understanding of their own individual student reading strategies in order to maximize their own learning, their own potential for learning, and their application of learning.

Since the surveyed applied on this research had four categories, the discussion is presented as an analysis of the findings of the most interesting results in each category.

The original Olszak study (2016) had four distinct categories of questions presented to the students. Those four categories were:

For this research which used the Olszak (2016) survey, the exact same four categories and the Yes and No questions that Olszak included at the end of her survey were also asked to the 97 students in this study.

Category number one was “Organizing reading and Planning.” In this category the most significant question was about exam planning. It has been analyzed as the first questions of the surveyed used in this study. When students have to take an exam in Spanish (first language) they tend to plan “usually” their exam according to student’s answers. Whereas, in English the answers showed to be “sometimes.” Having in mind that planning is an essential factor of metacognition, this behavior may be because students do not know how to get ready for exams. The differences between taking exams in Spanish and in English can be related to the culture and to the structure of the exam planned. For example, in English exams all questions are established with specific time for certain tasks. Whereas in Spanish, the time on an exam is only given as a specific amount of time for the whole test. Therefore, this cultural and structure change can effect students who are taking exams and the amount of time they take to do it.

Category number two was “Actions undertaking while reading.” The most significant question in this category was about guessing meaning according to the context where students in the first language and in the second language have the same amount impact answering 37.36% in both cases for “sometimes” that they do it while reading and a difference of around 3% in “Usually” to the same activity. Needs mo

Category number three was “Evaluation after reading” were Evaluation of strategies is one of the most significant questions that present significant differences on students first and second language strategies for reading. This was based on the need of students to find strategies to read faster and to comprehend better what they are asked to do in English. Whereas in Spanish, there is not such a need of strategies since they dominate the language and it is faster reading comprehension than it is in English.

Category number four was “Dealing with problems” The most common error from Spanish to English was translation which is the first thing students tend to do while they are reading and after reading.

The implications of the current study suggest in regards to the significance of applied teaching that teachers will need to have a much deeper and more complete understanding of individual student reading strategies. Such an understanding can greatly assist teachers in their efforts to be more effective and precise in their target teaching and reading strategies.

Because of the limited sized of the study (N = 97), potential implications from the results of this research study should be carefully evaluated. Additionally, there are no other known studies that have evaluated student-reading strategies in different Spanish programs of English for Special Purposes. Therefore, this research study provides the basis of pilot test research to help guide future research investigations.

Because statistically significant response differences were found among the four ESP programs, in the gender of the ESP students, and in the educational level of the ESP students, these results seem to suggest that ESP programs must be more thoroughly examined in more rigorous long term research to evaluate further the truer and deeper form of these statistically significant differences. Therefore, longitudinal studies could provide the best data for evaluating the occurrence and intensity of any statistically significantly differences. Additionally, future research should utilize larger sample sizes of thousands of ESP students, more equal numbers of females and males, and larger samples among ESP students with two or more language skill sets.

Such longitudinal studies could assist researchers in evaluating when and how such statistically significant changes occur. Additional considerations beyond the type of ESP program, the gender of the ESP students, and the educational level of the ESP students should also provide more precise measures of mastery of both written and spoken English skills in order to discover any other significant influencing factors that could further define such statistically significant differences.

References

- Alcantara, R.D. 2003. Teaching Strategies 1: For the Teaching of the Communication Arts: Listening, Speaking, Reading and Writing. Makati: Katha Publishing Co., Inc.

- Amirian, S. M. R. (2013). Teaching reading strategies to ESP readers. International Journal of Research Studies in Educational Technology, 2(2).file:///C:/Users/Success7/Downloads/318-1820-1-PB.pdf.

- Anderson, N.J. 1991. Individual differences in strategy use in second language reading and testing. The Modern Language Journal. Vol.75, No.4, 460-472.

- Anderson, N.J. 2003. Exploring Second Language Reading: Issues and Strategies. Beijing: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press. [CrossRef]

- Anthony, L. (1998). English for Specific Purposes: What does it mean. Retrieved September 1, 2015, from http://www.laurenceanthony.net/abstracts/ESParticle.html.

- Arellano, O. (17 de October de 2014). English for Specific Purposes . English for Specific Purposes at Political and Administrative Science Faculty at UNACH. (S. Ribadeneira, Interviewer).

- Basturkmen, H. (2006). Ideas and Options in English for Specific Purpose. Language Arts & Disciplines , 186.

- Brikci, N. (2007, February 1). A Guide to Using Qualitative Research Methodology. Retrieved August 15, 2015, from http://fieldresearch.msf.org/msf/bitstream/10144/84230/1/Qualitativeresearchmethodology.pdf.

- Bryman, A. (2015). Social research methods. Oxford university press.

- Cabrera, C. (1997). ESTADISTICA INFERENCIAL. Loja: Universidad Técnica Particular de Loja.

- Carrell, P.L. 1989. Metacognitive Awareness and Second Language Reading. Modern Language Journal. Vol.73, No.2, 121-134.

- Casco, D. (27 de August de 2015). English for Specific Purpose. English for Specific Purposes in the Political and Administrative Science Faculty at UNACH. (S.Ribadeneira, Interviewer).

- Cengage, H. (2008). Teaching Vocabulary: Strategies and Techniques. Boston: Nation.

- Cohen, A.D. 1990. Strategies in Learning and Using a Second Language. Shanghai: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press.

- Converse, J. M. & S. Presser, Survey Questions: Handcrafting the Standardized Questionnaire, Beverley Hills, Sage, 1986.

- Crawford, L., Tindal, G., & Stieber, S. (2001). Using oral reading rate to predict student performance on statewide achievement tests. Educational Assessment, 7(4), 303-323. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Lindy_Crawford/publication/238595234_Using_Oral_Reading_Rate_to_Predict_Student_Performance_on_Statewide_Achievement_Tests/links/54005c920cf2194bc29ac783.pdf.

- Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design Choosing Among Five Approaches (3rd ed., p. 472). Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications.

- Denzin NK, Lincoln YS (eds.). Handbook of Qualitative Research. London: Sage Publications, 2000.

- Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2011). The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research (4th ed., p. 984). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

- Dudley, T., Evans, Jo, M., & John, S. (2007). Developments in English for Specific Purposes (Vol. 9). United Kingdom: University Press, Cambridge.

- Fink, A., The Survey Research Handbook - How to Conduct Surveys: A Step-by-Step Guide, Beverley Hills: Sage, 1983.

- Flowerdew, J., & Peacock, M. (2001). Research perspectives on English for Academic Purposes. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Frendo, E. (2005). How to teach Business English. (J. Harmer, Ed.) Pearson Education Limited.

- Fuchs, L.S., Fuchs, D., & Hosp, M.K. (2001). Oral reading fluency as an indicator of reading competence: A theoretical, empirical, and historical analysis. Scientific Studies of Reading, 5(3), 239-256. Retrieved from http://www.psy.cmu.edu/~siegler/418-Fuchs.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Gómez, I. F. (2002). Cómo escribir un artículo de investigación en inglés. (A. Editorial, Ed.) Torrejón de Ardoz, Madrid: Archivos y Biblioteca del Ministerio de Educación y Cultura.

- Hernandez, S. (2014). Metodología de la Investigación. México: McGram Hill Interamericana.

- Harding, K. (2012). English for Specific Purposes . New York, USA: Oxford University Press.

- Hutchinson, T., & Alan Waters, W. (2003). English for Specific Purpose (Vol. 18). (H. B. Strevens, Ed.) New York: The New Directions in Language Teaching Series / Cambridge Language Teaching.

- Jafari, S. M., & Shokrpour, N. (2012). The reading strategies used by Iranian ESP students to comprehend authentic expository texts in English. International Journal of Applied Linguistics and English Literature, 1(4), 102-113.file:///C:/Users/Success7/Downloads/756-1571-1-SM.pdf. [CrossRef]

- López, P. (2015 de March and August de 2015). English for Specific Purposes. English for Specific Purposes in the Political and Administrative Science Faculty at UNACH. (S. Ribadeneira, Interviewer).

- Malmkjaer, K. (2004). The Linguistics Encyclopedia (Vol. Second Edition). New York: Routledge.

- Martínez, C. (2012). Estadística y muestreo / 13rd ed. Bogota: Ecoe Ediciones.

- Martínez, A. C. L. (2008). Analysis of ESP university students' reading strategy awareness. Ibérica: Revista de la Asociación Europea de Lenguas para Fines Específicos (AELFE), (15), 165-176.

- file:///C:/Users/Success7/Downloads/DialnetAnalysisOfESPUniversityStudentsReadingStrategyAwar-2573842.pdf.

- Marshall PA. Human subjects protections, institutional review boards, and cultural anthropological research. Anthropol Q 2003;76(2):269-85. [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, J. (2013). Qualitative Research Design An Interactive Approach (3rd ed., p. 232). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

- Miranda, C. (19 de October de 2014). English for Specific Purposes. English for Specific Purposes in the Political and Administrative Science Faculty at UNACH. (S. Ribadeneira, Interviewer).

- Mokhtari, K., & Reichard, C. A. (2002). Assessing students' metacognitive awareness of reading strategies. Journal of educational psychology, 94(2), 249.

- Mokhtari, K. & C. Reichard (2002). “Assessing students’ metacognitive awareness of reading strategies”. Journal of Educational Psychology 94: 249-259.

- Mokhtari, K. & Sheorey, R. (2002). Measuring ESL students’ awareness of reading strategies. Journal of Developmental Education, 25, 2-10.

- Northeastern University College of Computer and Information Science (2010). Qualitative Research Methods: A Data Collector’s Field Guide. (2010). Retrieved August 25, 2015, from http://www.ccs.neu.edu/course/is4800sp12/resources/qualmethods.pdf.

- O’Malley, J.M & Chamot, A.V. 1990. Learning Strategy in Second Language Acquisition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Olszak, I. (2016). An investigation into the use of reading strategies among students of dual language programs at selected Polish universities. English for Specific Purposes World, 17(51), 1-16.

- Oxford, R.L. 1990. Language Learning Strategies: What Every Teacher Should Know. New York: Newbery House Publishers.

- Patton, M.Q.(2001). Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Paris, S. G., & Jacobs, J. E. (1984). The benefits of informed instruction for children’s reading awareness and comprehension skills. Child Development, 55, 2083–2093.

- Paris, S. G., & Winograd, P. (1990). How metacognition can promote academic learning and instruction. In B. F. Jones & L. Idol (Eds.), Dimensions of thinking and cognitive instruction (pp. 15-51). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Poole, A. (2009). The reading strategies used by male and female Colombian university students. Profile Issues in TeachersProfessional Development, (11), 29-40.http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?pid=S1657-07902009000100003&script=sci_arttext&tlng=pt.

- Read, J. (2007). Second language vocabulary assessment. International Journal of English Studies , 105.

- Reece, L., Garnier, H., & Gallimore, R. (2000). Longitudinal analysis of the antecedents of emergent Spanish literacy and middle-school English reading achievement of Spanish-speaking students. American Educational Research Journal, 37 (3), 633 – 662. Retrieved fromhttps://www.researchgate.net/profile/Ronald_Gallimore/publication/250184930_Longitudinal_Analysis_of_the_Antecedents_of_Emergent_Spanish_Literacy_and_Middle-School_English_Reading_Achievement_of_Spanish-Speaking_Students1/links/00b7d5272b7de16582000000.pdf.

- Ricardo. (2010). elzhifestadistica. (C. D. INVESTIGACION, Producer) Retrieved 03 de 06 de 2015 Retrived from: http://elzhifestadistica.blogspot.com/2012/05/componentes-de- unainvestigacion.html.

- Rubin, H., & Rubin, I. (1995). Qualitative interviewing: The art of hearing data. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Rubin, J. (1981). The study of cognitive processes in second language learning. Applied Linguistics, 11, 118-131.

- Silberstein, S. 1994. Techniques and Resources in Teaching Reading. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [CrossRef]

- Silverman, D. "Qualitative research: meanings or practices?", Information Systems Journal (8:1) 1998, pp. 3-20.

- Smith, F. 1994. Understanding reading. 5th ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Vaez Dalili, M., & Tavakoli, M. (2013). A comparative analysis of reading strategies across ESP students of humanities and engineering. International Journal of Research Studies in Language Learning, 2(5).http://www.consortiacademia.org/index.php/ijrsll/article/viewFile/257/214. [CrossRef]

- Weiss, R. S. (1995). Learning from Strangers: The Art and Method of Qualitative Interview Studies (p. 256). New York, NY: Free Press.

- Wiley-Blackwell. (2012). The Handbook of English for Specific Purposes. (S. Starfield, & B. Paltridge, Eds.).

- Yin, R. K. (2014). Case study research: Design and methods (5th ed., p. 312). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).