Submitted:

02 July 2024

Posted:

03 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design, population and sample

2.2. Antigens

2.3. Reactivity towards SARS-CoV-2 antigens

2.4. Plaque Reduction Neutralization Test of Sputnik V vaccinees sera

2.5. Statistical analysis

3. Results

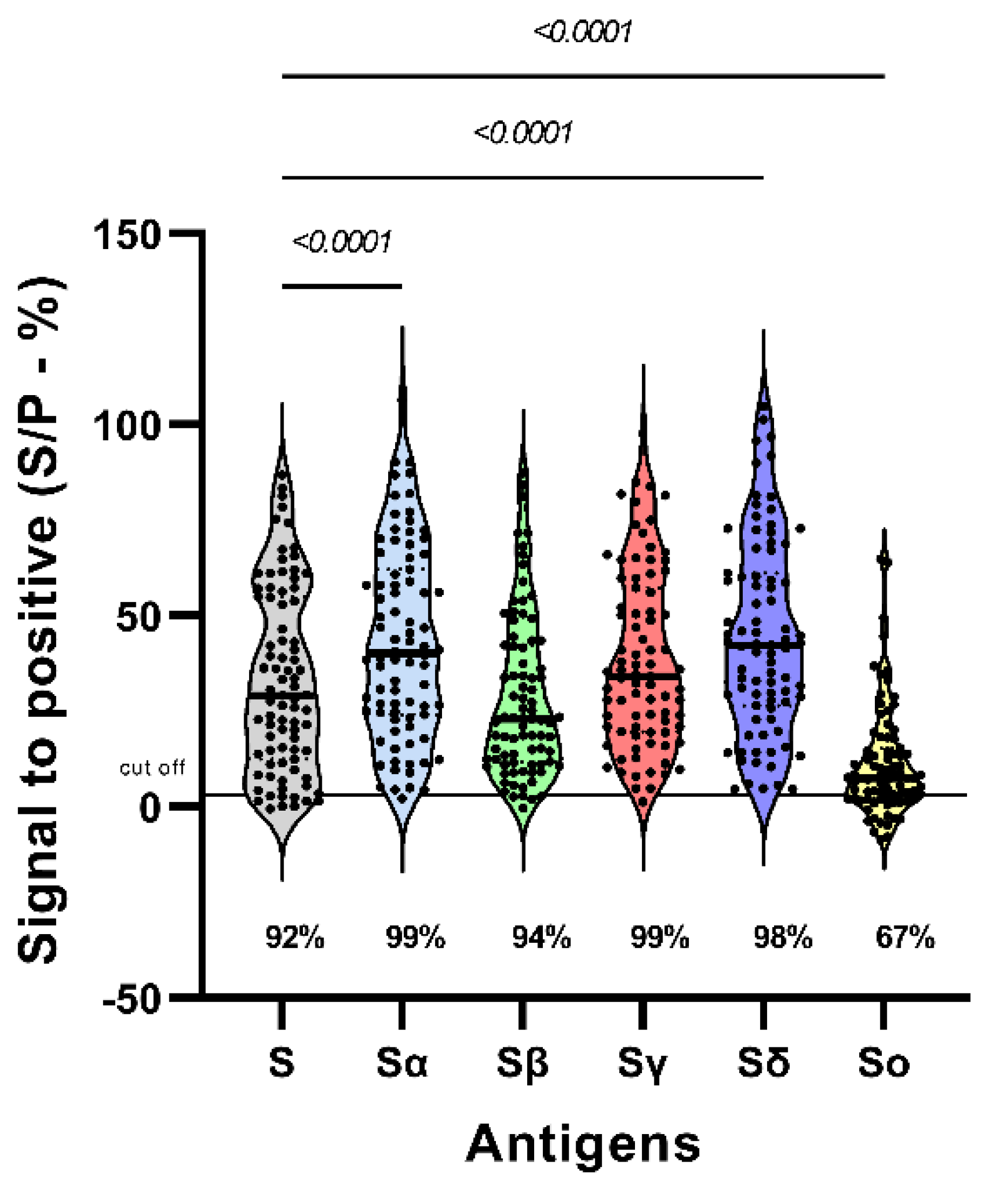

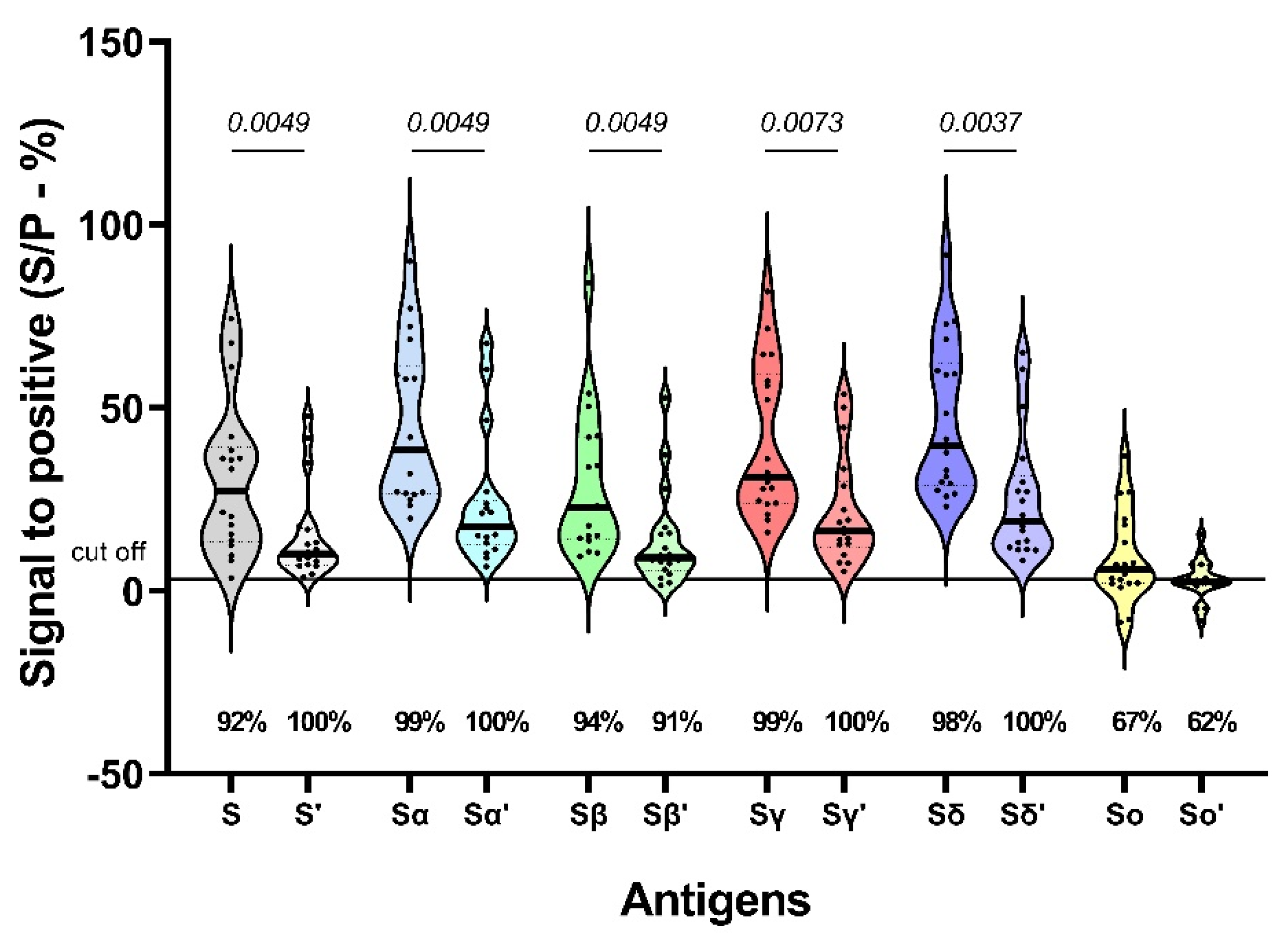

3.1. Reactivity to SARS-CoV-2 variants S protein

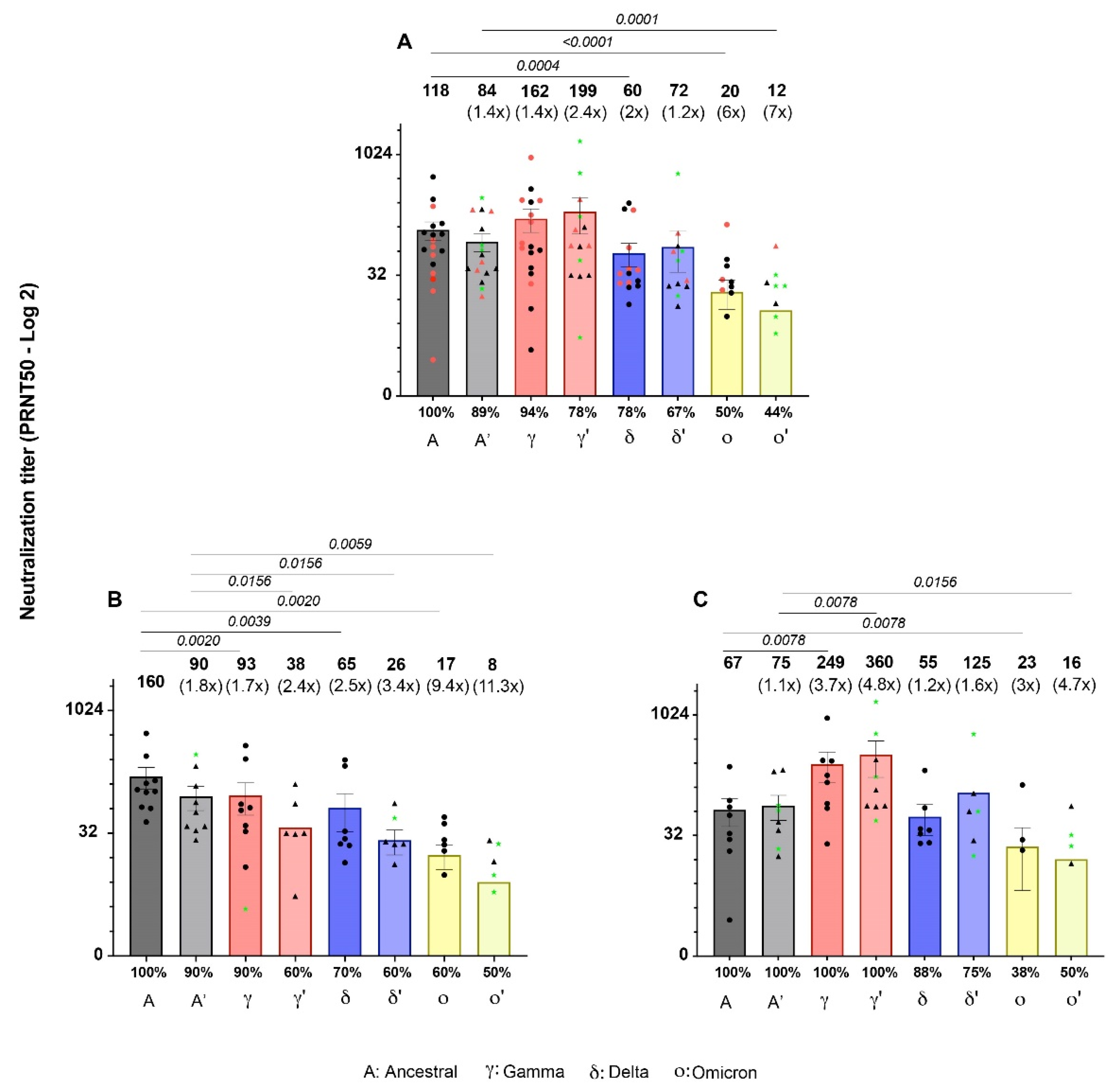

3.2. Neutralizing activity of Sputnik-V-induced antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 variants at 42 and 180 dpv.

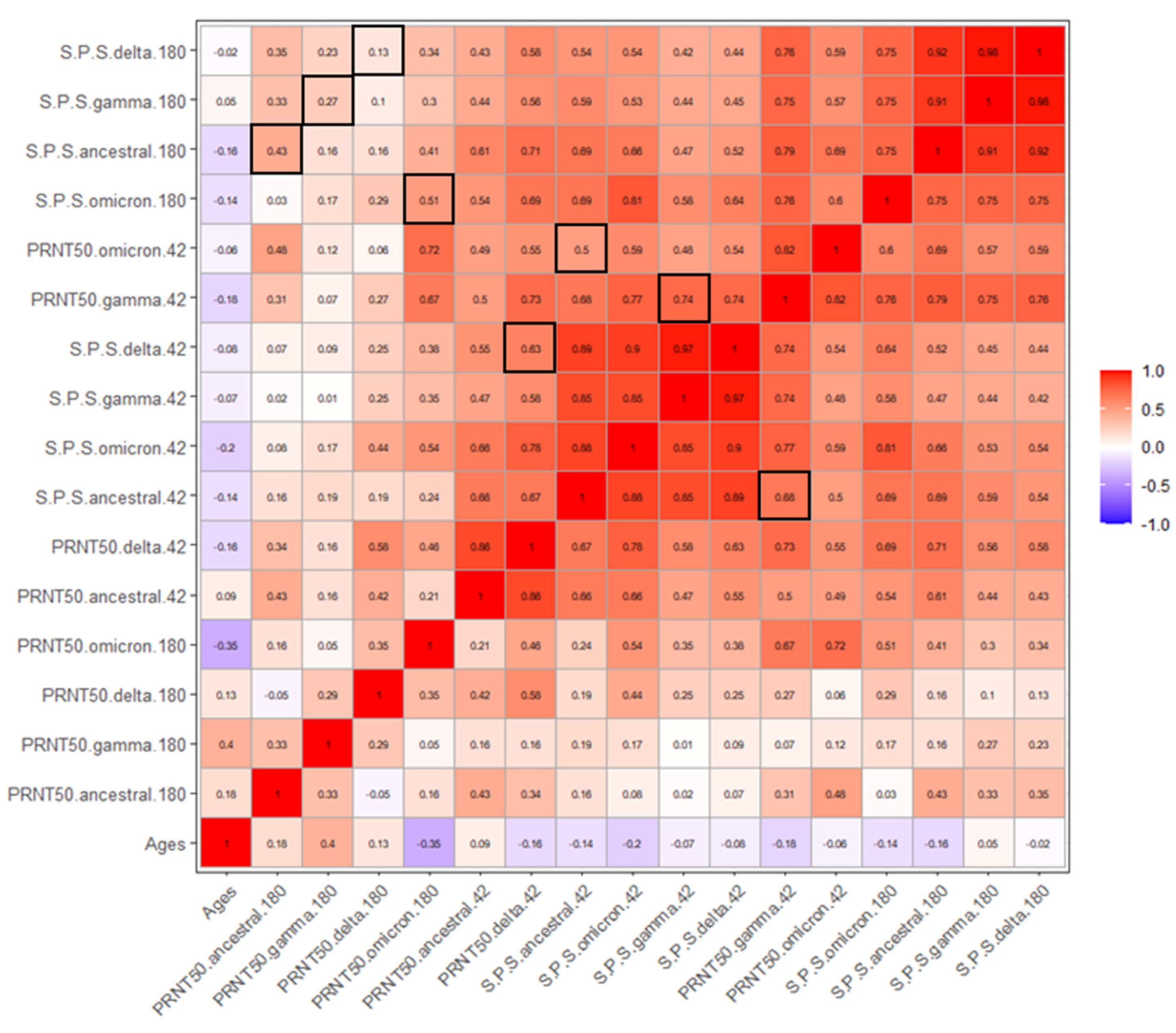

3.3. Correlation between age, reactivity and PRNT50.

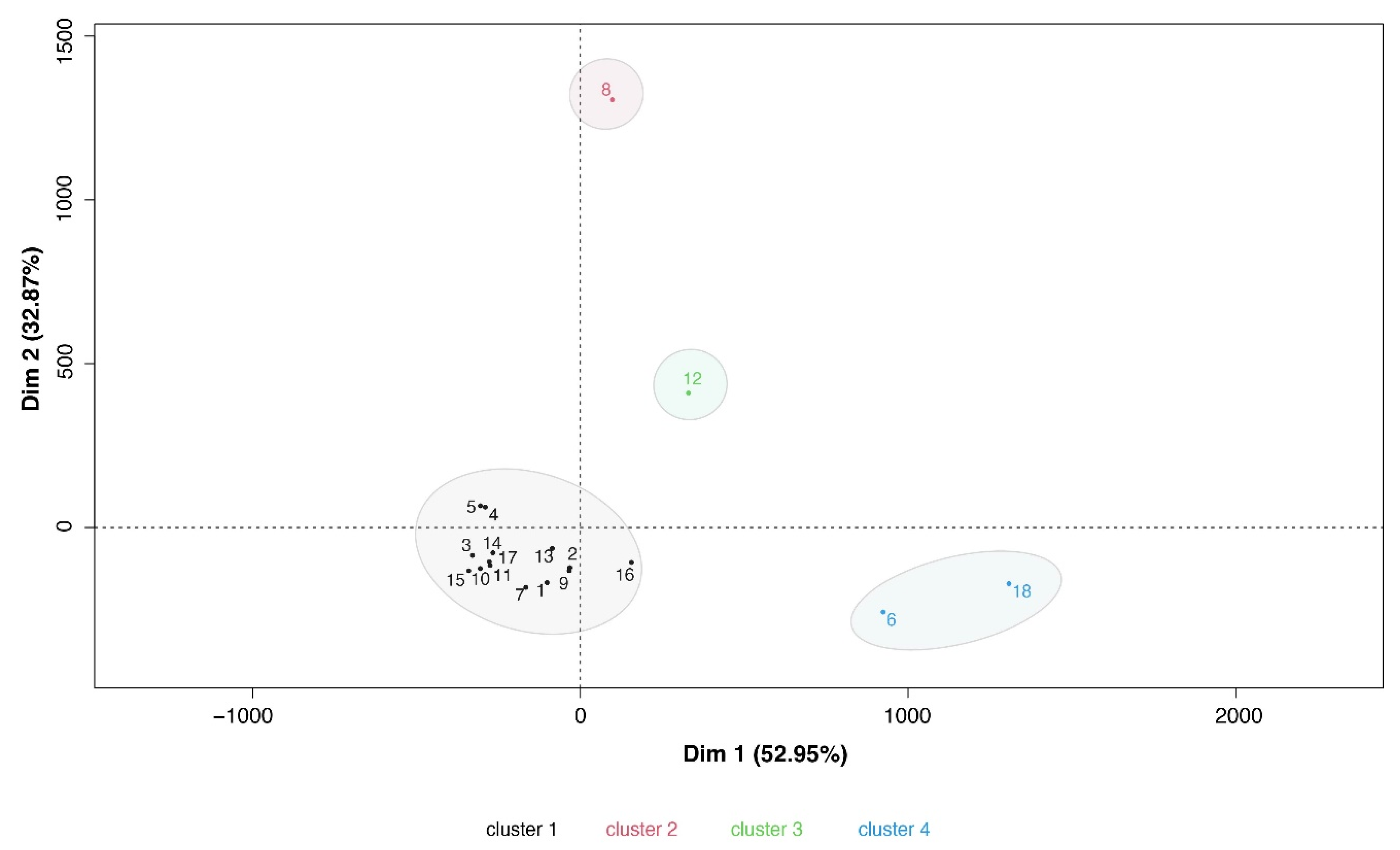

3.5. Signatures of antibody immune response in Sputnik V vaccinees.

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization WHO Data. Available online: https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19/cases?n=c (accessed on 26 March 2024).

- Barber, R.M.; Sorensen, R.J.D.; Pigott, D.M.; Bisignano, C.; Carter, A.; Amlag, J.O.; Collins, J.K.; Abbafati, C.; Adolph, C.; Allorant, A.; et al. Estimating Global, Regional, and National Daily and Cumulative Infections with SARS-CoV-2 through Nov 14, 2021: A Statistical Analysis. The Lancet 2022, 399, 2351–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Paulson, K.R.; Pease, S.A.; Watson, S.; Comfort, H.; Zheng, P.; Aravkin, A.Y.; Bisignano, C.; Barber, R.M.; Alam, T.; et al. Estimating Excess Mortality Due to the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Analysis of COVID-19-Related Mortality, 2020–21. The Lancet 2022, 399, 1513–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L. Retrospect of the Two-Year Debate: What Fuels the Evolution of SARS-CoV-2: RNA Editing or Replication Error? Curr Microbiol 2023, 80, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carabelli, A.M.; Peacock, T.P.; Thorne, L.G.; Harvey, W.T.; Hughes, J.; de Silva, T.I.; Peacock, S.J.; Barclay, W.S.; de Silva, T.I.; Towers, G.J.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Variant Biology: Immune Escape, Transmission and Fitness. Nat Rev Microbiol 2023, 21, 162–177. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sherif, Z.A.; Gomez, C.R.; Connors, T.J.; Henrich, T.J.; Reeves, W.B. Pathogenic Mechanisms of Post-Acute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 Infection (PASC). Elife 2023, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Ghildiyal, T.; Rai, N.; Mishra Rawat, J.; Singh, M.; Anand, J.; Pant, G.; Kumar, G.; Shidiki, A. Challenges in Emerging Vaccines and Future Promising Candidates against SARS-CoV-2 Variants. J Immunol Res 2024, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mykytyn, A.Z.; Rissmann, M.; Kok, A.; Rosu, M.E.; Schipper, D.; Breugem, T.I.; van den Doel, P.B.; Chandler, F.; Bestebroer, T.; de Wit, M.; et al. Antigenic Cartography of SARS-CoV-2 Reveals That Omicron BA.1 and BA.2 Are Antigenically Distinct. Sci. Immunol 2022, 7, 4450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendonça, S.A.; Lorincz, R.; Boucher, P.; Curiel, D.T. Adenoviral Vector Vaccine Platforms in the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic. NPJ Vaccines 2021, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiolet, T.; Kherabi, Y.; MacDonald, C.J.; Ghosn, J.; Peiffer-Smadja, N. Comparing COVID-19 Vaccines for Their Characteristics, Efficacy and Effectiveness against SARS-CoV-2 and Variants of Concern: A Narrative Review. Clinical Microbiology and Infection 2022, 28, 202–221. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Logunov, D.Y.; Dolzhikova, I.V.; Zubkova, O.V.; Tukhvatullin, A.I.; Shcheblyakov, D.V.; Dzharullaeva, A.S.; Grousova, D.M.; Erokhova, A.S.; Kovyrshina, A.V.; Botikov, A.G.; et al. Safety and Immunogenicity of an RAd26 and RAd5 Vector-Based Heterologous Prime-Boost COVID-19 Vaccine in Two Formulations: Two Open, Non-Randomised Phase 1/2 Studies from Russia. The Lancet 2020, 396, 887–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martynova, E.; Hamza, S.; Garanina, E.E.; Kabwe, E.; Markelova, M.; Shakirova, V.; Khaertynova, I.M.; Kaushal, N.; Baranwal, M.; Rizvanov, A.A.; et al. Long Term Immune Response Produced by the Sputnikv Vaccine. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikegame, S.; Siddiquey, M.N.A.; Hung, C.T.; Haas, G.; Brambilla, L.; Oguntuyo, K.Y.; Kowdle, S.; Chiu, H.P.; Stevens, C.S.; Vilardo, A.E.; et al. Neutralizing Activity of Sputnik V Vaccine Sera against SARS-CoV-2 Variants. Nat Commun 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gushchin, V.A.; Dolzhikova, I.V.; Shchetinin, A.M.; Odintsova, A.S.; Siniavin, A.E.; Nikiforova, M.A.; Pochtovyi, A.A.; Shidlovskaya, E.V.; Kuznetsova, N.A.; Burgasova, O.A.; et al. Neutralizing Activity of Sera from Sputnik V-Vaccinated People against Variants of Concern (VOC: B.1.1.7, B.1.351, P.1, B.1.617.2, B.1.617.3) and Moscow Endemic SARS-CoV-2 Variants. Vaccines (Basel) 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaspe, R.C.; Loureiro, C.L.; Sulbaran, Y.; Moros, Z.C.; D’Angelo, P.; Rodríguez, L.; Zambrano, J.L.; Hidalgo, M.; Vizzi, E.; Alarcón, V.; et al. Introduction and Rapid Dissemination of SARS-CoV-2 Gamma Variant of Concern in Venezuela. Infection, Genetics and Evolution 2021, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kudlay, D.; Svistunov, A. COVID-19 Vaccines: An Overview of Different Platforms. Bioengineering 2022, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Basta, N.; Moodie, E. COVID19 VACCINE TRACKER. Available online: https://covid19.trackvaccines.org/vaccines/approved/ (accessed on 30 June 2024).

- Cornejo, A.; Franco, C.; Rodríguez, M.; García, A.; Belisario, I.; Mayoría, S.; Garzaro, D.J.; Zambrano, J.L.; Jaspe, R.C.; Hidalgo, M.; et al. Humoral Immunity across the SARS-CoV-2 Spike after Sputnik V (Gam-COVID-Vac) Vaccination. Antibodies 2024, 13, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stadlbauer, D.; Amanat, F.; Chromikova, V.; Jiang, K.; Strohmeier, S.; Arunkumar, G.A.; Tan, J.; Bhavsar, D.; Capuano, C.; Kirkpatrick, E.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Seroconversion in Humans: A Detailed Protocol for a Serological Assay, Antigen Production, and Test Setup. Curr Protoc Microbiol 2020, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claro, F.; Silva, D.; Rodriguez, M.; Rangel, H.R.; de Waard, J.H. Immunoglobulin G Antibody Response to the Sputnik V Vaccine: Previous SARS-CoV-2 Seropositive Individuals May Need Just One Vaccine Dose. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 2021, 111, 261–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Nuñez, M.; Cepeda, M. del V.; Bello, C.; Lopez, M.A.; Sulbaran, Y.; Loureiro, C.L.; Liprandi, F.; Jaspe, R.C.; Pujol, F.H.; Rangel, H.R. Neutralization of Different Variants of SARS-CoV-2 by a F(Ab′)2 Preparation from Sera of Horses Immunized with the Viral Receptor Binding Domain. Antibodies 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, M.M.; Ledesma, L.; Sanchez, L.; Ojeda, D.S.; Rouco, S.O.; Rossi, A.H.; Varese, A.; Mazzitelli, I.; Pascuale, C.A.; Miglietta, E.A.; et al. Longitudinal Study after Sputnik V Vaccination Shows Durable SARS-CoV-2 Neutralizing Antibodies and Reduced Viral Variant Escape to Neutralization over Time. mBio 2022, 13, e03442–21. [Google Scholar]

- Röltgen, K.; Nielsen, S.C.A.; Silva, O.; Younes, S.F.; Zaslavsky, M.; Costales, C.; Yang, F.; Wirz, O.F.; Solis, D.; Hoh, R.A.; et al. Immune Imprinting, Breadth of Variant Recognition, and Germinal Center Response in Human SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Vaccination. Cell 2022, 185, 1025–1040.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Logunov, D.Y.; Dolzhikova, I.V.; Shcheblyakov, D.V.; Tukhvatulin, A.I.; Zubkova, O.V.; Dzharullaeva, A.S.; Kovyrshina, A.V.; Lubenets, N.L.; Grousova, D.M.; Erokhova, A.S.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of an RAd26 and RAd5 Vector-Based Heterologous Prime-Boost COVID-19 Vaccine: An Interim Analysis of a Randomised Controlled Phase 3 Trial in Russia. The Lancet 2021, 397, 671–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radion, E.I.; Mukhin, V.E.; Kholodova, A.V.; Vladimirov, I.S.; Alsaeva, D.Y.; Zhdanova, A.S.; Ulasova, N.Y.; Bulanova, N.V.; Makarov, V.V.; Keskinov, A.A.; et al. Functional Characteristics of Serum Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Antibodies against Delta and Omicron Variants after Vaccination with Sputnik V. Viruses 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Claro, F.; Silva, D.; Pérez Bogado, J.A.; Rangel, H.R.; de Waard, J.H. Lasting SARS-CoV-2 Specific IgG Antibody Response in Health Care Workers from Venezuela, 6 Months after Vaccination with Sputnik V. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 2022, 122, 850–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lapa, D.; Grousova, D.M.; Matusali, G.; Meschi, S.; Colavita, F.; Bettini, A.; Gramigna, G.; Francalancia, M.; Garbuglia, A.R.; Girardi, E.; et al. Retention of Neutralizing Response against SARS-CoV-2 Omicron Variant in Sputnik V-Vaccinated Individuals. Vaccines (Basel) 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greaney, A.J.; Starr, T.N.; Gilchuk, P.; Zost, S.J.; Binshtein, E.; Loes, A.N.; Hilton, S.K.; Huddleston, J.; Eguia, R.; Crawford, K.H.D.; et al. Complete Mapping of Mutations to the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Receptor-Binding Domain That Escape Antibody Recognition. Cell Host Microbe 2021, 29, 44–57.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Victora, G.D.; Nussenzweig, M.C. Germinal Centers. Annu Rev Immunol 2022, 30, 429–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.S.; O’Halloran, J.A.; Kalaidina, E.; Kim, W.; Schmitz, A.J.; Zhou, J.Q.; Lei, T.; Thapa, M.; Chen, R.E.; Case, J.B.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 MRNA Vaccines Induce Persistent Human Germinal Centre Responses. Nature 2021, 596, 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudd, P.A.; Minervina, A.A.; Pogorelyy, M.V.; Turner, J.S.; Kim, W.; Kalaidina, E.; Petersen, J.; Schmitz, A.J.; Lei, T.; Haile, A.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 MRNA Vaccination Elicits a Robust and Persistent T Follicular Helper Cell Response in Humans. Cell 2022, 185, 603–613.e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, R.R.; Painter, M.M.; Apostolidis, S.A.; Mathew, D.; Meng, W.; Rosenfeld, A.M.; Lundgreen, K.A.; Reynaldi, A.; Khoury, D.S.; Pattekar, A.; et al. MRNA Vaccines Induce Durable Immune Memory to SARS-CoV-2 and Variants of Concern. Science (1979) 2021, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Zhou, J.Q.; Horvath, S.C.; Schmitz, A.J.; Sturtz, A.J.; Lei, T.; Liu, Z.; Kalaidina, E.; Thapa, M.; Alsoussi, W.B.; et al. Germinal Centre-Driven Maturation of B Cell Response to MRNA Vaccination. Nature 2022, 604, 141–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakharkar, M.; Rappazzo, G.; Wieland-Alter, W.F.; Hsieh, C.L.; Wrapp, D.; Esterman, E.S.; Kaku, C.I.; Wec, A.Z.; Geoghegan, J.C.; McLellan, J.S.; et al. Prolonged Evolution of the Human B Cell Response to SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Sci Immunol 2021, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moriyama, S.; Adachi, Y.; Sato, T.; Tonouchi, K.; Sun, L.; Fukushi, S.; Yamada, S.; Kinoshita, H.; Nojima, K.; Kanno, T.; et al. Temporal Maturation of Neutralizing Antibodies in COVID-19 Convalescent Individuals Improves Potency and Breadth to Circulating SARS-CoV-2 Variants. Immunity 2021, 54, 1841–1852.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaebler, C.; Wang, Z.; Lorenzi, J.C.C.; Muecksch, F.; Finkin, S.; Tokuyama, M.; Cho, A.; Jankovic, M.; Schaefer-Babajew, D.; Oliveira, T.Y.; et al. Evolution of Antibody Immunity to SARS-CoV-2. Nature 2021, 591, 639–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krauson, A.J.; Casimero, F.V.C.; Siddiquee, Z.; Stone, J.R. Duration of SARS-CoV-2 MRNA Vaccine Persistence and Factors Associated with Cardiac Involvement in Recently Vaccinated Patients. NPJ Vaccines 2023, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stebbings, R.; Armour, G.; Pettis, V.; Goodman, J. AZD1222 (ChAdOx1 NCov-19): A Single-Dose Biodistribution Study in Mice. Vaccine 2022, 40, 192–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogata, A.F.; Cheng, C.A.; Desjardins, M.; Senussi, Y.; Sherman, A.C.; Powell, M.; Novack, L.; Von, S.; Li, X.; Baden, L.R.; et al. Circulating Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Vaccine Antigen Detected in the Plasma of MRNA-1273 Vaccine Recipients. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2022, 74, 715–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonker, L.M.; Swank, Z.; Bartsch, Y.C.; Burns, M.D.; Kane, A.; Boribong, B.P.; Davis, J.P.; Loiselle, M.; Novak, T.; Senussi, Y.; et al. Circulating Spike Protein Detected in Post-COVID-19 MRNA Vaccine Myocarditis. Circulation 2023, 147, 867–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tam, H.H.; Melo, M.B.; Kang, M.; Pelet, J.M.; Ruda, V.M.; Foley, M.H.; Hu, J.K.; Kumari, S.; Crampton, J.; Baldeon, A.D.; et al. Sustained Antigen Availability during Germinal Center Initiation Enhances Antibody Responses to Vaccination. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016, 113, E6639–E6648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aung, A.; Cui, A.; Maiorino, L.; Amini, A.P.; Gregory, J.R.; Bukenya, M.; Zhang, Y.; Lee, H.; Cottrell, C.A.; Morgan, D.M.; et al. Low Protease Activity in B Cell Follicles Promotes Retention of Intact Antigens after Immunization. Science (1979) 2023, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Hart, M.; Chui, C.; Ajuogu, A.; Brian, I.J.; de Cassan, S.C.; Borrow, P.; Draper, S.J.; Douglas, A.D. Germinal Center B Cell and T Follicular Helper Cell Responses to Viral Vector and Protein-in-Adjuvant Vaccines. The Journal of Immunology 2016, 197, 1242–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Mateus, J.; Coelho, C.H.; Dan, J.M.; Moderbacher, C.R.; Gálvez, R.I.; Cortes, F.H.; Grifoni, A.; Tarke, A.; Chang, J.; et al. Humoral and Cellular Immune Memory to Four COVID-19 Vaccines. Cell 2022, 185, 2434–2451.e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuñez, N.G.; Schmid, J.; Power, L.; Alberti, C.; Krishnarajah, S.; Kreutmair, S.; Unger, S.; Blanco, S.; Konigheim, B.; Marín, C.; et al. High-Dimensional Analysis of 16 SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine Combinations Reveals Lymphocyte Signatures Correlating with Immunogenicity. Nat Immunol 2023, 24, 941–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islas-Vazquez, L.; Cruz-Aguilar, M.; Velazquez-Soto, H.; Jiménez-Corona, A.; Pérez-Tapia, S.M.; Jimenez-Martinez, M.C. Effector-Memory B-Lymphocytes and Follicular Helper T-Lymphocytes as Central Players in the Immune Response in Vaccinated and Nonvaccinated Populations against SARS-CoV-2. Vaccines (Basel) 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jandl, C.; King, C. Cytokines in the Germinal Center Niche. Antibodies 2016, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yegorov, S.; Kadyrova, I.; Negmetzhanov, B.; Kolesnikova, Y.; Kolesnichenko, S.; Korshukov, I.; Baiken, Y.; Matkarimov, B.; Miller, M.S.; Hortelano, G.H.; et al. Sputnik-V Reactogenicity and Immunogenicity in the Blood and Mucosa: A Prospective Cohort Study. Sci Rep 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaspe, R.C.; Loureiro, C.L.; Sulbaran, Y.; Moros, Z.C.; D’angelo, P.; Hidalgo, M.; Rodríguez, L.; Alarcón, V.; Aguilar, M.; Sánchez, D.; et al. Description of a One-Year Succession of Variants of Interest and Concern of SARS-CoV-2 in Venezuela. Viruses 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marklund, E.; Leach, S.; Axelsson, H.; Nystrom, K.; Norder, H.; Bemark, M.; Angeletti, D.; Lundgren, A.; Nilsson, S.; Andersson, L.M.; et al. Serum-IgG Responses to SARS-CoV-2 after Mild and Severe COVID-19 Infection and Analysis of IgG Non-Responders. PLoS One 2020, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanco, S.; Salomé Konigheim, B.; Diaz, A.; Spinsanti, L.; Javier Aguilar, J.; Elisa Rivarola, M.; Beranek, M.; Collino, C.; MinSalCba working group; FCM-UNC working group; et al. Evaluation of the Gam-COVID-Vac and Vaccine-Induced Neutralizing Response against SARS-CoV-2 Lineage P.1 Variant in an Argentinean Cohort. Vaccine 2022, 40, 811–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, O.J.; Barnsley, G.; Toor, J.; Hogan, A.B.; Winskill, P.; Ghani, A.C. Global Impact of the First Year of COVID-19 Vaccination: A Mathematical Modelling Study. Lancet Infect Dis 2022, 22, 1293–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, I.C.H.; Zhang, R.; Man, K.K.C.; Wong, C.K.H.; Chui, C.S.L.; Lai, F.T.T.; Li, X.; Chan, E.W.Y.; Lau, C.S.; Wong, I.C.K.; et al. Persistence in Risk and Effect of COVID-19 Vaccination on Long-Term Health Consequences after SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Nat Commun 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilks, S.H.; Mühlemann, B.; Shen, X.; Türeli, S.; LeGresley, E.B.; Netzl, A.; Caniza, M.A.; Chacaltana-Huarcaya, J.N.; Corman, V.M.; Daniell, X.; et al. Mapping SARS-CoV-2 Antigenic Relationships and Serological Responses. Science (1979) 2023, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Vaccine | Manufacturer | Country | PUBMED entries | Vaccine approved in countries (N) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BNT162b2 (Comirnaty) |

Pfizer – BioNTech | Germany | 14309 | 149 |

| ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 (AZD1222) | Astra Zeneca – Oxford University | Sweden | 5911 | 149 |

| Ad26.COV 2-S (Jcovden) | Janssen Biotech, Inc (Johnson & Johnson) | Belgium | 4088 | 113 |

| mRNA-1273 (Spikevax) | Moderna | USA | 4824 | 88 |

| CoronaVac | Sinovac | China | 1223 | 56 |

| BBIBP-CorV (Covilo) |

Sinopharm | China | 725 | 93 |

| NVX-CoV2373 (Nuvaxovid) | Novavax | USA | 989 | 40 |

| Gam-COVID-Vac (Sputnik V) | Gamaleya | Russia | 563 | 74 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).