1. Introduction

Family planning (FP) has the potential to save over 30% of maternal and 10% of newborn deaths worldwide, making it one of the most important public health concerns as well as one of the most "health-promoting" and economical public health promotion initiatives [

1]. It is an essential part of the healthcare given before conception, right after delivery, and in the first year following childbirth [

2]. It includes all the goods, services, information, commodities, attitudes, and policies —including contraceptives — that encourage individuals, couples, women, men, and teenagers to choose when and whether to have a child and prevent unintended pregnancies [

3,

4]. Furthermore, FP permits controlled population growth that yields socioeconomic advantages such as decreased gender disparity, poverty, and increased access to education [

5].

According to Starbird et al. [

4], enhancing the accessibility of family planning services improves maternal and child health, and promotes gender parity and women’s empowerment. Also, FPS is necessary to avoid unintended pregnancies, reducing the risk of unsafe abortions, other pregnancy-associated issues, and economic burdens [

1]. Despite these benefits, equal access to FP services is a challenge in Pakistan because of a lack of education, poor knowledge of FP, and low socio-economic status, ultimately affecting the utilization of FP services in Pakistan [

6]. Additionally, several other health system-related factors such as inadequate health service delivery, low access to outreach services, and ineffectiveness of FP programs have been linked with the under-utilization of FP services in Pakistan [

6,

7,

8].

Pakistan is experiencing exponential growth of population which poses major challenges, hence a need for enhanced uptake and continuation of FP services. Globally, Pakistan was rated the fifth most populated nation with about 225 million people. But, according to the estimations of PBS [

9] & WPP [

10], the population will grow to 310 million by 2050. In 2012, the Pakistani government promised to commit its efforts to address this challenge by increasing the nation’s contraceptive prevalence rate (CPR) to 55% by 2020, which was then modified to 50% by 2025 [

11]. However, since 2007, Pakistan's CPR has been stagnant in the range of 30–35% despite the political efforts, allotted funds, and extensive FP programs [

12,

13,

14,

15]. Variation still occurs in the usage of FP services in different regions of Pakistan, especially in the rural areas. Although the government and several stakeholders in the FP domain have endeavored to promote FP, challenges still exist in increasing the optimal uptake of CPR [

16,

17]. Pakistan confronts difficulties in attaining sustainable development, lowering population growth, and enhancing maternal health [

18].

Notably, Pakistani provinces show variations in the total fertility rate (TFR) and the CPR. The 2017 and 2018 PDHS reported that Gilgit-Baltistan province has the highest TRF of 4.7, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa has 4.0, and Balochistan has the lowest TFR of 3.0. However, CPR was the highest (35%) in Islamabad and the lowest (35%) in Balochistan [

19]. These inequities are relatively higher at the district level; for example, the Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) conducted between 2017 – 2018 shows that CPR varied from 49% in the Multan district to 17% in the Gujranwala district of the Punjab province [

20]. Also, the same variations are found across the districts in other regions. This issue underlines the need for targeted or tailored approaches/interventions to reach the most marginalized and vulnerable women in Pakistan [

21]. More so, despite the continuous efforts of the government, many potential barriers still exist to the use of contraceptives, especially among women of childbearing age in Pakistan because of social, cultural, and perceived religious unacceptability of contraception, lack of knowledge and awareness of contraception, cost of contraception, and access to contraceptive services [

22,

23,

24,

25].

Current research studies have highlighted the significance of spatial analysis techniques, like Cluster Hotspot Analysis, and Geographic Information Systems (GIS), in the identification of geographic inequities in family planning and reproductive health services uptake [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31]. This study, however, aimed to add to the body of existing knowledge by investigating provincial or regional inequities in the use of FPS in Pakistan. It demonstrated the application of innovative techniques in the evaluation and planning of family planning programs that can strategically transform the family planning landscape in Pakistan. It maps geographic disparities in contraceptive prevalence rates, specifically identifying areas with statistically significant high or low-prevalence rates for uptake of any type of contraceptive method. This study can assist policy and program planners in identifying areas that require immediate attention and resource allocation.

2. Materials and Methods

The study used Pakistan Demographic and Health Surveys (PDHS) that were collected in 2006-07 and 2017-18. The PDHS is a nationally representative household survey conducted every five years. The survey consists of 2 stage cluster design sampling, which includes: (a) clusters as primary sampling units that are generally drawn from census files; and (b)secondary sampling units consisting of 25-30 households that are randomly selected within each cluster. Details on the sampling strategy can be accessed at the DHS Program website (“Sampling and Household Listing Manual [DHSM4]”). The DHS program collects GPS coordinates for the survey cluster or primary sampling unit. These coordinates are distorted to maintain the confidentiality and anonymity of the survey respondents. The clusters in rural areas are displaced 5km from the center, and the clusters in urban areas are displaced 2km from the center. Further details on the displacement can be accessed at the DHS program site [

32].

2.1. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive analysis was reported as frequency and percentage. The contraceptive prevalence rates were calculated using the master file provided by the DHS Program. The master file provides the “do” files to recode survey variables and perform tabulation to calculate prevalence rates [

33]. All statistical analysis was done using Stata 12.0 (College Station, Texas, USA), and spatial analysis was performed with ArcMap 10.1 (ESRI, USA). The study calculated the CPR for any method (aCPR), and modern methods (mCPR), in addition to unmet need and intent to use family planning services and preference for ideal family size for each cluster.

Moran's I index was used to assess the autocorrelation in the clusters. The index identified if there was any significant spatial pattern, clustered, dispersed, or random, in the data. It calculates Moran’s I Index, including z-score and p-value, to evaluate the significance of the Index. The Index value ranges from -1 to 1. A positive value indicates a clustered pattern, a negative indicates a dispersed pattern, and 0 indicates random distribution. A high z-score and a low p-value indicate a statistically significant deviation from a random pattern [

34]. Hotspot Analysis using the Getis-Ord Gi* statistics was conducted to identify statistically significant high values (hotspots) and low values (cold spots). The output feature class calculates z-scores, p-values, and confidence levels in fields. It is interpreted by analyzing the statistical significance of z-scores, p-values, and bin values of high and low clusters [

35]. Interpolation was performed using the ordinary Kriging method that provides optimum accuracy of predicted values for unsampled locations based on a weighted combination of nearby data points.

3. Results

There was a total of 957 and 560 clusters in PDHS 2006-07 and 2017-18, respectively. The PDHS 2006-07 had 385 (40.22%) clusters from urban areas and 572 (59.77%) clusters from rural areas, whereas the PDHS 2017-18 had 282 (50.35%) clusters from urban areas and 278 (49.64%) clusters from rural areas. The spatial auto-correlation analysis indicated that the distribution of CPR of any method, CPR of the modern methods, and unmet need of family planning was not randomly distributed as indicated by the Global Moran’s I values in

Table 1.

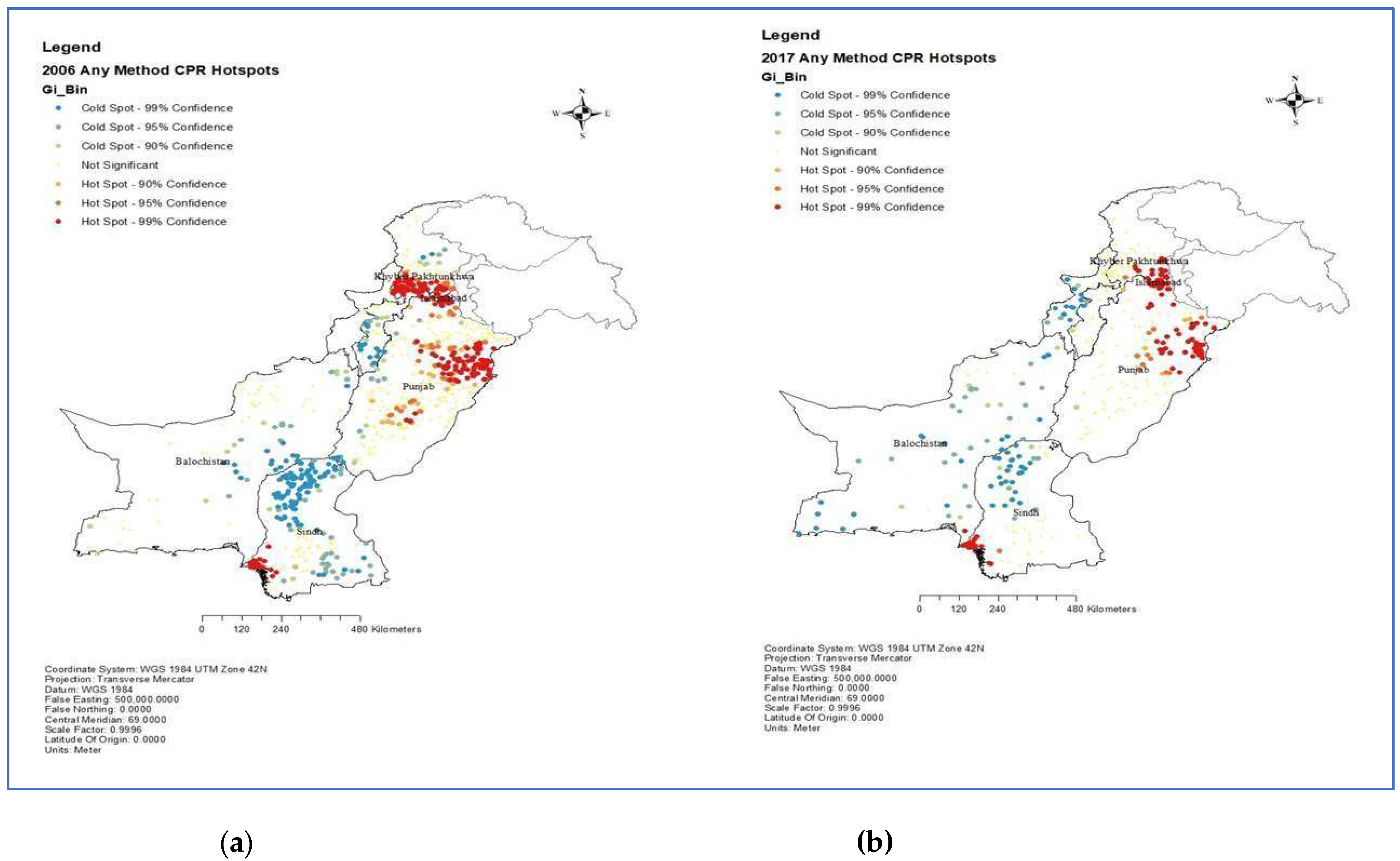

3.1. Hotspots Analysis of CPR for any Method

The hotspot analysis of contraceptive prevalence rate for any method (aCPR), based on the PDHS 2006-07 data, revealed distinct spatial patterns. The areas with high aCPR were found to be more clustered in lower or urban Sindh, upper or urban and certain parts of central Punjab, and urban areas of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP). Conversely, most Balochistan, Sindh, and KP exhibited the lowest CPR for any method during this period, as indicated by the significant cold spots.

In the subsequent analysis of PDHS 2017 data, a notable change in the spatial distribution of CPR for any method was observed. The high CPR hotspots in Punjab had contracted, primarily limited to the upper urban centers. In Sindh, the cold spots started diffusing but still concentrated in the upper part, while the situation remained relatively unchanged in the other provinces.

Figure 1.

Hotspot analysis of contraceptive prevalence rate for any method. (a) Any method CPR hotspots, 2006 (b) Any method CPR hotspots 2017.

Figure 1.

Hotspot analysis of contraceptive prevalence rate for any method. (a) Any method CPR hotspots, 2006 (b) Any method CPR hotspots 2017.

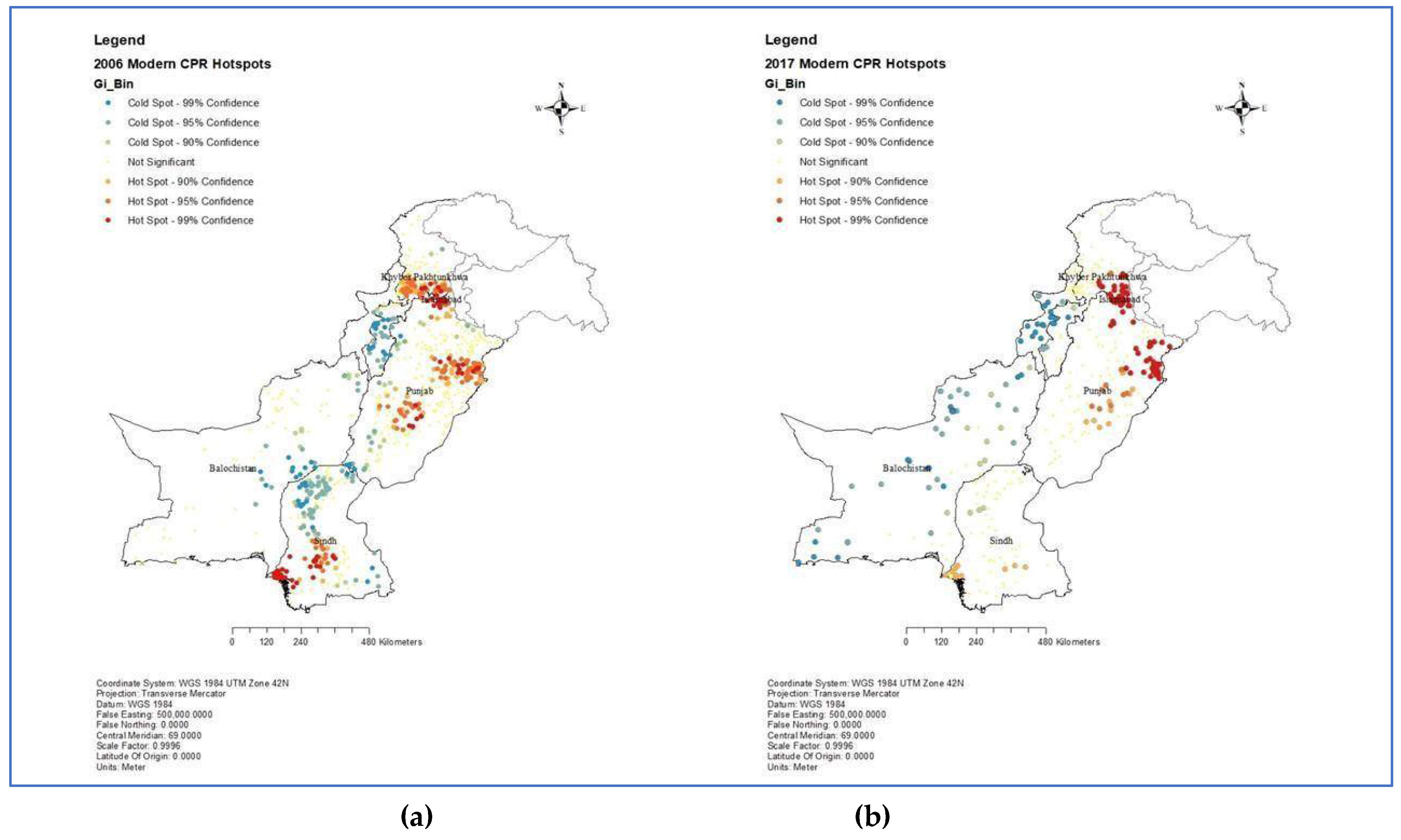

3.2. Hotspots Analysis of CPR for Modern Method

The hotspot analysis of the contraceptive prevalence rate for the modern method (mCPR), based on the PDHS 2006-07 data, revealed spatial patterns similar to the analysis of CPR for any method. The areas with high mCPR were clustered in lower and central Sindh, upper and central Punjab, and urban areas of KP. Conversely, most of Balochistan, upper Sindh, and lower KP exhibited the lowest CPR for the modern method during this period. When analyzing the PDHS 2017 data, it was found that the most significant mCPR hotspots were identified in Punjab and they had maintained almost a similar distribution as 2006. In Sindh, the mCPR remained concentrated in the lower province, while central Sindh, a hotspot in 2006, did not maintain the same position in 2017, indicating a more uneven distribution of mCPR. Likewise, upper Sindh, which had a dense cluster of cold spots in 2006, did not indicate a similar pattern in 2017, and the clusters were diffused indicating an improvement in the distribution of mCPR. The situation remained relatively unchanged in KP, but Balochistan exhibited some sporadic cold spots of mCPR as compared to 2006.

Figure 2.

Hotspot analysis of contraceptive prevalence rate for modern method. (a) Modern CPR hotspots, 2006 (b) Modern CPR hotspots, 2017.

Figure 2.

Hotspot analysis of contraceptive prevalence rate for modern method. (a) Modern CPR hotspots, 2006 (b) Modern CPR hotspots, 2017.

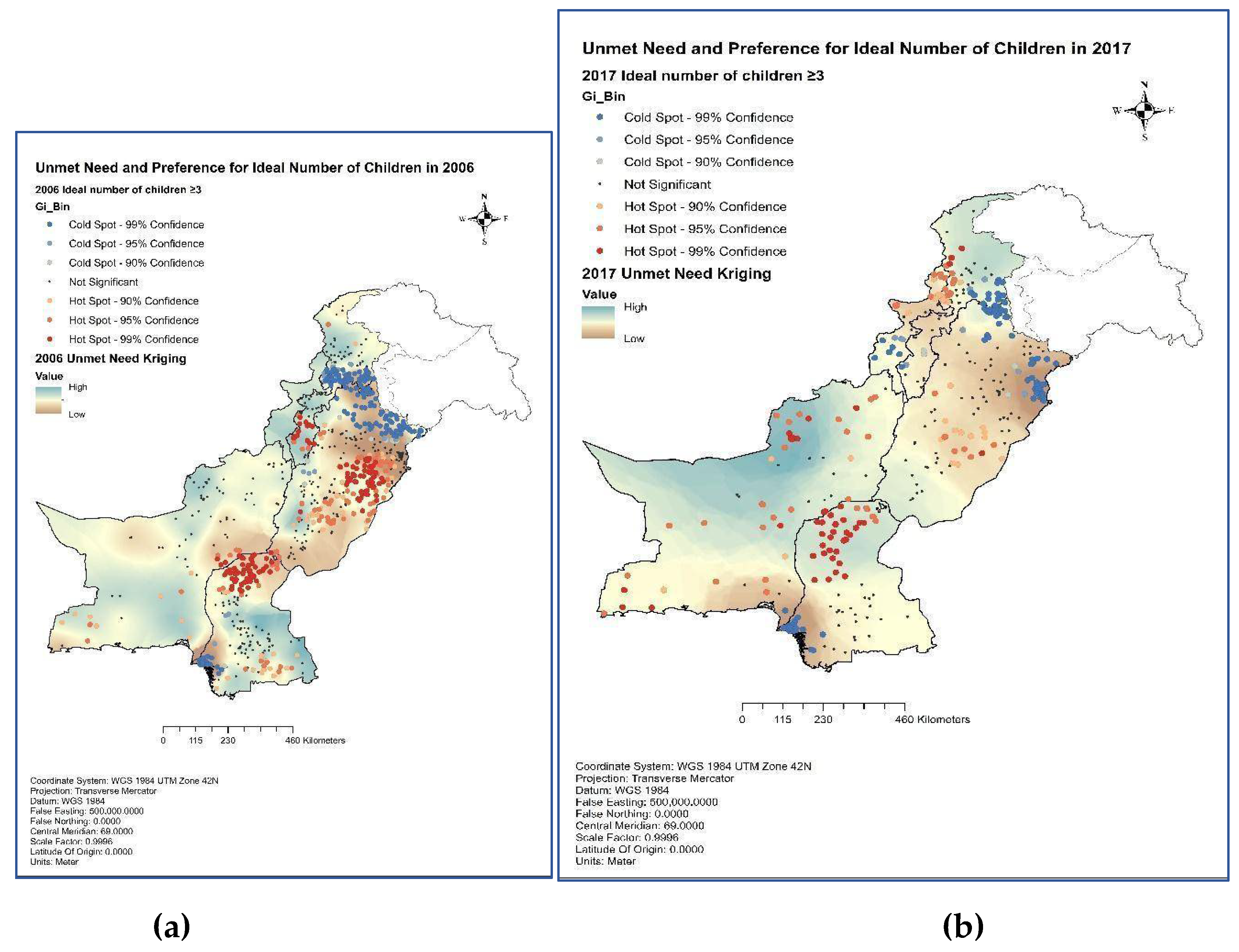

3.3. Unmet Need and Ideal Number of Children

Our hotspot analysis of the ideal number of children with unmet needs indicated that regions expressing a preference for three or more children were notably concentrated in areas characterized by moderate to the highest unmet needs. Metropolitan centers, which exhibited the lowest unmet need values, displayed cold spots for three or more children, indicating a prevalent inclination towards a lower number (<3) of children.

Figure 3.

Hotspot analysis of unmet needs and the ideal number of children. (a) Unmet need and preference for the ideal number of children in 2006 (b) Unmet need and preference for the ideal number of children in 2017.

Figure 3.

Hotspot analysis of unmet needs and the ideal number of children. (a) Unmet need and preference for the ideal number of children in 2006 (b) Unmet need and preference for the ideal number of children in 2017.

In 2006, the province of Sindh exhibited pronounced hotspot clusters of preference for more than 3 children in its northern part, accompanied by sporadic clusters in the southern region with high unmet needs. Similar trends were observed in the provinces of Punjab and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP), where significant hotspots of preferences marked areas with moderate to high unmet needs for three or more children. Notably, despite having the highest unmet need, Balochistan displayed only a limited number of hotspots in this regard. The year 2017 showcased notable shifts in spatial distribution, particularly in Balochistan and KP. Balochistan saw widespread hotspots throughout the province, primarily in areas with the highest unmet need. Conversely, KP displayed cold spots for preferences of three or more children, even in areas characterized by moderate unmet needs. In Sindh, the southern-northern region remained a hotspot for clusters favoring three or more children. In central Punjab, sporadic hotspots emerged in regions marked by moderate unmet needs.

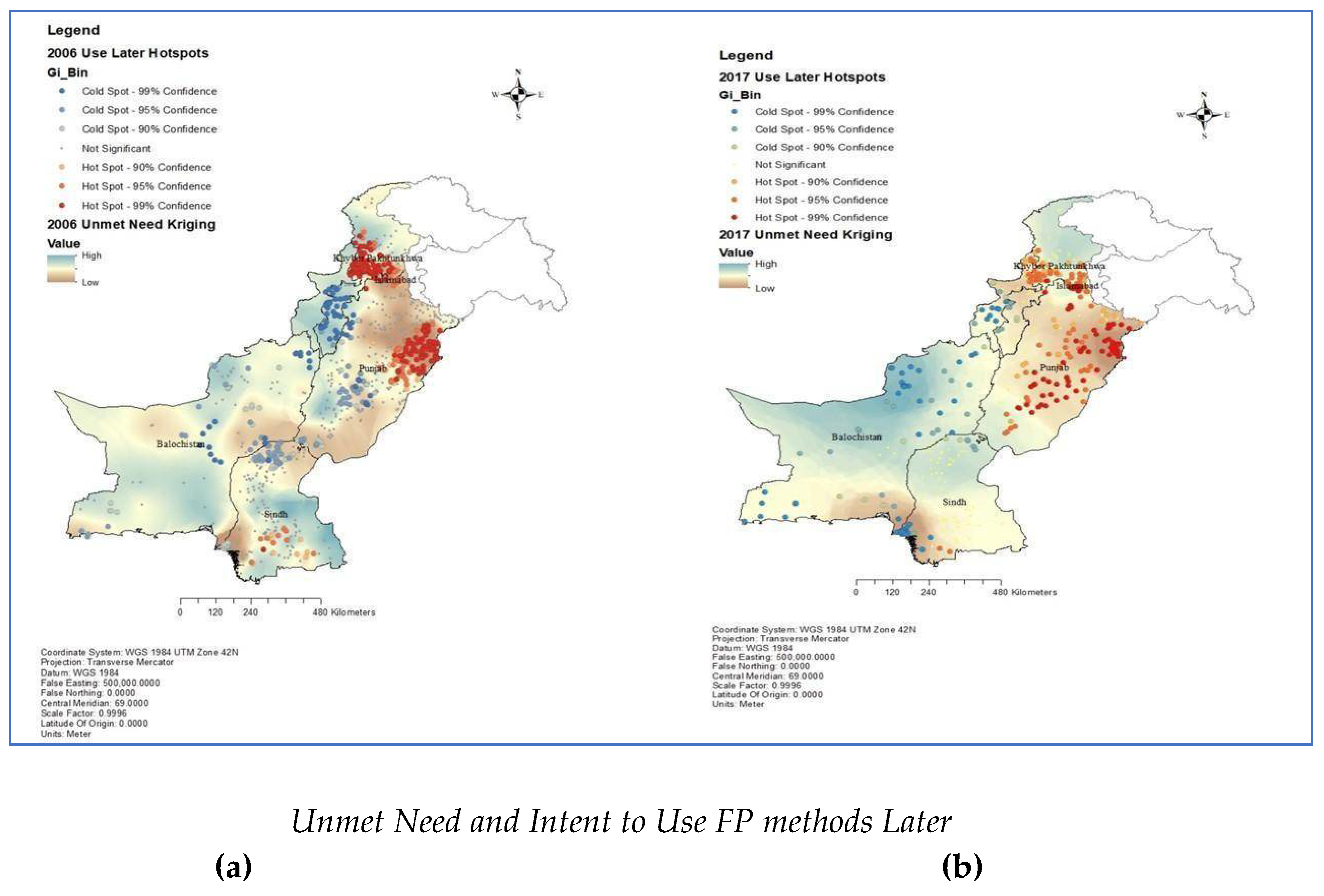

Figure 4.

Hotspot analysis of unmet needs and intent to use family planning methods later. (a) Use Later Hotspots, 2006 (b) Use Later Hotspots, 2017.

Figure 4.

Hotspot analysis of unmet needs and intent to use family planning methods later. (a) Use Later Hotspots, 2006 (b) Use Later Hotspots, 2017.

The spatial distribution of unmet needs of family planning (FP) was assessed using the Kriging method in this study. Clusters with a high proportion of individuals expressing the intent to use FP services were later identified. In 2006, statistically significant clusters indicating the intent to use FP services later were observed in areas of high unmet need in Sindh. However, upper Sindh, which exhibited relatively low unmet needs, had clusters with lower intention to use FP service later. In Punjab, the clusters using FP services were more concentrated in areas with low unmet needs. In contrast, central and lower Punjab demonstrated significantly lower proportions of intention to use FP services. In KP, the clusters with a high proportion of intent to use FP services were concentrated in areas with low unmet needs. In contrast, lower KP with high unmet needs showed statistically significant cold spots or clusters with a lower proportion of intention to use them later. Balochistan had high unmet needs in 2006 and sporadic cold spots of intention to use FP services.

Analyzing the 2017 data, lower Sindh exhibited an increase in the number of clusters with cold spots, indicating a higher prevalence of areas with lower intention to use FP services. This is also the area with the lowest unmet need in Sindh. Only the upper part of Sindh was observed to have high unmet needs and cold spots of intention to use. The rest of Sindh which previously had hotspots of intention to use FP methods later, were not significant in 2017. In Punjab, the situation became more dispersed, with the observation of sporadic hotspot clusters throughout the province, indicating a more favorable attitude throughout the province. The unmet need became concentrated in the lowest part of Punjab, with few hotspots of intent to use FP services later. No significant changes were observed in KP, and Balochistan continued to exhibit cold spots concerning the intention to use FP services later, particularly in areas with high unmet needs, indicating a more challenging situation where despite high unmet needs people don't intend to use FP services.

4. Discussion

Family planning efforts in Pakistan have sluggish progress over the past two decades, failing to achieve desired targets and outcomes. Various factors, including socioeconomic, cultural, and gender preferences, contraceptive side effects, service availability, and accessibility barriers, have been identified as facilitators or barriers to family planning uptake [

25,

36,

37,

38]. The previous studies helped profile the users and non-users of contraceptives in Pakistan. However, this current research uniquely applies a micro-level lens by harnessing spatial statistical tools to identify high and low uptake clusters and intentions to use FP services in Pakistan. This approach enables the precise identification of “hotspots” and “cold spots” where family planning utilization is significantly higher or lower than national trends, respectively. Targeting interventions based on this granular understanding of localization promises to improve efficiency and effectiveness by segmenting patient populations, identifying high-risk communities, and providing accessible and engaging visualizations for policymakers and practitioners, akin to successful strategies in other public health interventions [

39,

40,

41].

This study revealed substantial geographic disparities and clustering in the uptake of family planning services across provinces and predominantly urban areas in Pakistan. The situation of mCPR has evolved between 2006 and 2017, with some contracting and diffusion of previously concentrated hotspots. In 2006, mCPR was concentrated in the urban clusters of the provinces. Similar findings were observed by other researchers who used PDHS 2006-07 and reported that educated women in the upper wealth quintiles and residing in urban areas were more likely to use family planning services [

42]. However, some increase in contraceptive uptake was noticed in rural women, primarily because of traditional methods [

43]. Sequential analysis of PDHS 2017 indicated an interesting spatial disparity in the distribution of clusters among and within the provinces, especially in Sindh and Punjab. A situation very similar to previously reported findings that indicated widespread socioeconomic and regional disparities [

44].

Our research findings from hotspot analysis for PDHS 2017 showed that the distribution of mCPR has evolved differently in different geographies. Sindh no longer retains the hot spots of mCPR, indicating a point of concern for program planners. Simultaneously, the cold spots in upper Sindh have dispersed too, indicating an improvement in mCPR in upper Sindh. This improvement in upper Sindh and concerning position in lower Sindh, at the same time, demands immediate attention in areas that previously had higher mCPR and no longer retained the same position in 2017. In contrast, the distribution of the highest CPR for any method and mCPR in Punjab displayed a similar clustering pattern, primarily in and around urban areas. Balochistan continued to exhibit the lowest prevalence of mCPR in 2017 and the emergence of cold spots throughout the province demands the immediate attention of donors, implementing partners, and government agencies. Sarwar

et al. observed a similar pattern of reproductive health services uptake across the country [

28].

Our analysis of ideal family size preferences hotspots has unveiled distinct spatial patterns that demonstrate an inverse association with unmet needs in Pakistan. The areas that prefer three or more children are mainly concentrated in regions with moderate to the highest unmet need. This observation suggested an interesting phenomenon where those with the highest unmet need prefer having a larger family size. This suggests that in regions with significant unmet needs, there is a prevailing cultural preference for larger families, which may delay or complicate the adoption of family planning measures. Conversely, metropolitan centers that have low unmet needs exhibited cold spots for preferences of three or more children, indicating a widespread inclination towards smaller family sizes, usually less than three children. This phenomenon resonates with trends observed in other developing regions, where the unmet need for family planning varies with age and reproductive goals [

45]. Importantly, our findings highlight that areas with high unmet needs tend to consider larger family sizes as ideal, underscoring the necessity for targeted social and behavioral change communication interventions rather than simply addressing supply-side deficiencies.

As revealed in our study, the spatial distribution of unmet need for FP and the intention to use FP services presented intriguing insights into the dynamics of FP preferences across different regions and periods in Pakistan. In 2017, a significant geographical shift was observed in the intention to use in Sindh & Punjab only. Specifically, intention to use was not clustered in areas with high unmet needs. The north or upper Sindh, with a significantly higher concentration of unmet needs, was resistant to adopting FP services, as observed by the persistent clusters of low intention to use FP.

In Punjab, most upper and central parts exhibited low unmet needs and high intention to use FP services, indicating a significant transition from low to high intention to use FP services between 2006 to 2017. Consequently, there was a temporal shift in unmet needs across the province, except for the southern or lower Punjab region, which still grappled with high unmet needs but displayed significant hotspots of intention to use. Although women in South Punjab intend to use FP services, factors such as limited autonomy in health-seeking behavior and the influence of socio-cultural and religious values act as barriers, preventing young girls and women from accessing family planning [

46].

Interestingly, the presence of cold spots of intention to use FP services or hotspots of not intending to use in areas of high unmet need in upper Sindh, entire Balochistan, and lower KP prompts a reconsideration of the utility of unmet need for FP in policy and program planning. Unmet contraceptive needs contribute to unwanted fertility in low and middle-income nations, serving as a guide for family planning initiatives. The findings from our study indicated that almost all the areas with the highest unmet needs are clustered with cold spots of intention to use FP services in the future. Moreau

et al. reported only half of the women with current unmet needs for contraception intend to use contraception in the future, underscoring the complex nature of unmet needs, where lack of demand plays a substantial role. The insight emphasized the importance of considering both point prevalence measures of unmet need to understand the current situation and dynamic measures like unmet demand for contraception to identify women who are interested and willing to use contraception in the future [

47].

4.1. Methodological Innovation

The present study implemented advanced geospatial techniques, including spatial autocorrelation analysis, and hotspot analysis in geographic information system (GIS) mapping, to examine geographic disparities in family planning services uptake in Pakistan. While previous studies have relied primarily on individual or broad provincial or regional comparisons [

23,

42,

48,

49], this research uniquely applies a micro-level lens by harnessing spatial statistical tools to identify clusters of high and low uptake at the more granular level using primary clusters of DHS. The widely used landscape analysis report assessed consumers, service provision, contraceptive supply, and policies and regulations in Pakistan to identify investment opportunities for increasing contraceptive prevalence [

50]. Our approach strengthened existing evidence through precise identification of “hotspots” and “cold spots” where family planning utilization is significantly higher or lower than national trends, respectively. Interventions that focus on specific “hot and cold spots” based on this granular understanding of localization promise to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of family planning services delivery in Pakistan.

4.2. Contribution to the Field

This study makes several notable contributions to family planning and public health research:

Precision Targeted Interventions: Using geospatial analysis to pinpoint specific geographical areas with the lowest family planning service utilization provides unprecedented detail to guide resource allocation and coordinated intervention efforts by policymakers and health organizations. This precision approach allows for developing targeted strategies to address social and behavioral factors, access barriers, and service gaps in the communities with the highest need.

Dynamic Visualization of Disparities: The geospatial mapping techniques used to generate intuitive visual representations of family planning uptake variation and need across geographic areas. Compared to traditional stats-heavy results, these maps enhance comprehension, communication, and decision-making regarding spatial disparities for policymakers, implementation partners, and local communities.

Temporal Changes and Trends: The analysis of two-time points identifies temporal shifts in family planning service utilization and changes in geographic hotspots/cold spots over time. This temporospatial perspective enriches understanding of evolving dynamics around family planning access, uptake, and continuation.

4.3. Study Limitations

The study had limitations, including reliance on self-reported data from cross-sectional surveys. The exact geographic coordinates of the clusters were displaced to conceal the actual position of the respondents and maintain confidentiality. Urban clusters were displaced up to two kilometers and rural clusters up to five kilometers. However, the lead researcher ensured that displaced coordinates remained within the actual administrative boundary of the cluster. Hence the data can be used for identifying the geospatial distribution of variables of interest. Further qualitative and longitudinal research can provide deeper insights into reasons for clustered disparities between provinces, rural-urban areas, and intention-need gaps.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, this study provided valuable insights into the geographic disparities in FP uptake in Pakistan, highlighting the need for targeted interventions to address these variations effectively. By leveraging advanced spatial analysis techniques, including hotspot analysis, this identified clusters of both high and low contraceptive prevalence rates (CPR), offering actionable intelligence for policymakers and healthcare practitioners. These findings highlighted the importance of tailoring interventions to specific geographic areas identified through hotspot analysis, which has the potential to optimize resource allocation and improve FP service delivery, particularly in marginalized and underserved areas.

Furthermore, the identification of geographic disparities in FP uptake not only informs the design of theory-guided targeted interventions but should stimulate meaningful collaborations between stakeholders to drive policy reform. The multifaceted challenges hindering FP uptake in Pakistan can be best addressed through prioritized, evidenced-based decision-making and investments in sustainable strategies that support women’s reproductive health. As a result, improves maternal and child health outcomes, and also empowers individuals and communities to make informed choices about their reproductive health.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.K., and M.S.; methodology, B.K.; formal analysis, B.K.; writing—original draft preparation, B.K., and E O.; writing—review and editing, M.S.; B.K.; and E.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study used publicly available data.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

The data used for this study was obtained from the Pakistan Demographic and Health Surveys (PDHS) that were collected between 2006-07 and 2017-18. The PDHS is a nationally representative household survey conducted every five years. Details on the sampling strategy can be accessed at the DHS Program website (“Sampling and Household Listing Manual [DHSM4]”).

Data is available with the DHS Program of ICF at https://dhsprogram.com/data/available-datasets.cfm and can be accessed upon approval of a formal request to the DHS Program.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the ICF for providing access to the Pakistan Demographic and Health Surveys (PDHS) to be used for this study. Also, they thank the participants who made it possible for them to conduct the study from multicultural viewpoints.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- UNFPA. Investing in three transformative results: realizing powerful returns; UNFPA: New York, 2022; Available online: https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/Realizing%20powerful%20returnsEN FINAL.pdf.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use, Fourth edition. 2009. Available online: http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/family_planning/9789241563888/en/index. html (accessed on 10 October 2013).

- Stenberg, K.; Axelson, H.; Sheehan, P.; Anderson, I.; Gülmezoglu, A. M.; Temmerman, M. Study group for the global investment framework for women's children's health. Advancing social and economic development by investing in women’s and children’s health: a new Global Investment Framework. Lancet 2014, 383, 1333–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Starbird, E.; Norton, M.; Marcus, R. Investing in family planning: Key to achieving sustainable development goals. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2016, 27, 191–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denton, E. H. Benefits of family planning. Glob Popul Reprod Health 2014, 199, 199–219. [Google Scholar]

- Ortayli, N.; Malarcher, S. Equity analysis: identifying who benefits from family planning programs. Studies in Family Planning 2010, 41, 101–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, M.; Sahin-Hodoglugil, N. N.; Potts, M. Barriers to fertility regulation: a review of the literature. Studies in family planning 2006, 37, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, S.; Stephenson, R. Provider, and health facility influences on contraceptive adoption in urban Pakistan. International family planning perspectives 2006, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pakistan Bureau of Statistics (PBS). Provisional summary results of 6th population and housing census-2017; Pakistan Bureau of Statistics: Islamabad, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- World Population Prospects (WPP). Highlights. New York: United Nations, 2019 ST/ESA/SER.A/423.

- UKAID. BMGF, WHO. London summit on family planning: summaries of commitments. Report No. 2012. https://pmnch.who.int/docs/librariesprovider 9/governance/12th-board-meeting-2may2012-family-planning-summit-en.pdf? Status=Master&sfvrsn=53093522_5.

- National Institute of Population Studies (NIP). Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey 2006-07. Islamabad, Pakistan: National Institute of Population Studies (NIPS) and Macro International Inc 2008. Report No. 6/2008.

- National Institute of Population Studies (NIP). Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey 2012-13. Islamabad, Pakistan, and Rockville, Maryland, USA: NIPS and ICF 2013. Report No. 10/2013.

- National Institute of Population Studies (NIPS). DHSM. Pakistan demographic and health survey 2017–18. 2018. Report No. 2018.

- Khan, A. A. Family planning trends and programming in Pakistan. J Pak Med Assoc. 2021, 71 (Suppl 7), S3–S11. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, R. N.; Ahmad, K. Impact of Population on Economic Growth: A case study of Pakistan. Bulletin of Business and Economics (BBE) 2016, 5, 162–176. [Google Scholar]

- Abbas, F.; Awan, H. S. What determines the health status of the population in Pakistan? Soc Indic Res. 2018, 139, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhutta, Z. A.; Hafeez, A. What can Pakistan do to address maternal and child health over the next decade? Health Res Policy Sys. 2015, 13 (Suppl 1), S49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Population Studies (NIPS). Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey 2017-18. Islamabad: National Institute of Population Studies. Https://dhsprogram.com/pubs /pdf/FR354 /FR354. pdf. 2019. Accessed on April 14, 2024.

- Government of Punjab (GoP). Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey 2018–19. Lahore: Bureau of Statistics, Planning & Development Board, Government of Punjab. 2019.

- Aziz, A.; Khan, F.A.; Wood, G. Who is excluded and how? An analysis of community spaces for maternal and child health in Pakistan. Health Res Policy Sys. 2015, 13 (Suppl 1), S56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, F.; Jonker, L. Educational level and family planning among Pakistani women: A prospective explorative knowledge, attitude and practice study. Middle East Fertility Soc J 2018, 23, 464–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, M. F.; Pervaiz, Z. Socio-demographic determinants of unmet need for family planning among married women in Pakistan. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, A. N. Z.; Wheldon, M.; Kantorova, V.; Ueffing, P. Progress in Family Planning: Did the Millennium Development Goals Make a Difference? Population Association of America 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, N. Z.; Ali, T.; Jehan, I.; Gul, X. Struggling with long-time low uptake of modern contraceptives in Pakistan. East Mediterr Health J 2020, 26, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merid, M.W.; Kibret, A.A.; Alem, A.Z.; Asratie, M.H.; Aragaw, F.M.; Chilot, D.; Belay, D.G. Spatial variations and multi-level determinants of modern contraceptive utilization among young women (15-24 years) in Ethiopia: spatial and multi-level analysis of mini-EDHS 2019. Contracept Reprod Med. 2023, 10, 8–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birara, A.S.; Urmale, M.K.; Sharew, M.M.; Woday, T.A. Spatial distribution and determinants of nonautonomy on decision regarding contraceptive utilization among married reproductive-age women in Ethiopia: Spatial and Bayesian Multilevel Analysis. Nurs Res Pract. 2021, 2160922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwar, A. Mapping out regional disparities of reproductive health care services (RHCS) across Pakistan: an exploratory spatial approach. Asia-Pacific Journal of Regional Science 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naz, S.; Acharya, Y. The effect of reframing the goals of family planning programs from limiting fertility to birth spacing: Evidence from Pakistan. Stud Fam Plann. 2021, 52, 125–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahfuzur, M.R.; Billah, M.A.; Liebergreen, N.; Ghosh, M. K.; Alam, M.S.; Haque, M.A.; Al-Maruf, A. Exploring spatial variations in level and predictors of unskilled birth attendant delivery in Bangladesh using spatial analysis techniques: Findings from nationally representative survey data. PLoS One 2022, 25, 17–e0275951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belay, A. S.; Sarma, H.; Yilak, G. Spatial distribution and determinants of unmet need for family planning among all reproductive-age women in Uganda: a multi-level logistic regression modeling approach and spatial analysis. Contracept Reprod Med. 2024, 9, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgert, C. R.; Colston, J.; Roy, T.; Zachary, B. Geographic displacement procedure and georeferenced data release policy for the demographic and health surveys. DHS Spatial Analysis Reports No. 7. 2013. Calverton, Maryland, USA: ICF International. I: Calverton, Maryland, USA.

- DHSProgram. GitHub - DHSProgram/DHS-Indicators-Stata: Stata code to produce Demographic and Health Survey Indicators. GitHub 2021. Available online: https://github.com/DHS Program /DHS-Indicators-Stata (accessed on 8 September 2023).

- ArcGIS Pro. How Spatial Autocorrelation (Global Moran’s I) works— Documentation. 2018. Available online: https://pro.arcgis.com/en/pro-app/latest/tool-reference/spatial-statistics/h-how-spatial-autocorrelation-moran-s-i-spatial-st.htm (accessed on 15 September 2023).

- ArcGIS Pro. How Hot Spot Analysis (Getis-Ord Gi*) works—ArcGIS Pro Documentation. 2018. Available online: https://pro.arcgis.com/en/pro-app/latest/tool-reference/spatial-statistics/h-how-hot-spot-analysis-getis-ord-gi-spatial-stati.htm#GUID-6939C62C-E1E6-4409-BF1B-1CCD22DE0A63 (accessed on 15 September 2023).

- Azmat, S.; Mustafa, G.; Hameed, W.; Ali, M.; Ahmed, A.; Bilgrami, M. Barriers and perceptions regarding different contraceptives and family planning practices amongst men and women of reproductive age in rural Pakistan: A qualitative study. Pak J Public Health 2012, 2, 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, A.; Zar, A.; Wadood, A. Factors associated with modern contraceptive use among men in Pakistan: Evidence from Pakistan demographic and health survey 2017-18. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0273907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meherali, S.; Ali, A.; Khaliq, A.; Lassi, Z.S. Prevalence and determinants of contraception use prevalence: trend analysis from the Pakistan Demographic and Health Surveys (PDHS) dataset from 1990 to 2018. F1000Res 2021, 10, 790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baig, K.; Shaw-Ridley, M.; Munoz, O.J. Applying geospatial analysis in community needs assessment: Implications for planning and prioritizing based on data. Eval Program Plann. 2016, 58, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dworkis, D.A.; Taylor, L.A.; Peak, D.A.; Bearnot, B. Geospatial analysis of emergency department visits for targeting community-based responses to the opioid epidemic. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0175115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poulos, R.G.; Chong, S.S.; Olivier, J.; Jalaludin, B. Geospatial analyses to prioritize public health interventions: a case study of pedestrian and pedal cycle injuries in New South Wales, Australia. Int J Public Health 2012, 57, 467–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, K.S.; Zaheer, S.; Qureshi, M.S.; Aslam, S.N.; Shafique, K. Socio-economic disparities in use of family planning methods among Pakistani women: Findings from Pakistan Demographic and Health Surveys. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0153313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carton, T. W.; Agha, S. Changes in contraceptive use and method mix in Pakistan: 1990–91 to 2006–07. Health Policy and Planning 2016, 27, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacQuarrie, K.L.D.; Aziz, A. Trends, differentials, and determinants of modern contraceptive use in Pakistan, 1990-2018. DHS Further Analysis Reports No. 129. 2020. Rockville, Maryland, USA: ICF.

- Wulifan, J.K.; Brenner, S.; Jahn, A.; De Allegri, M. A scoping review on determinants of unmet need for family planning among women of reproductive age in low and middle-income countries. BMC Womens Health 2016, 16, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omer, S.; Zakar, R.; Zakar, M.Z.; Fischer, F. The influence of social and cultural practices on maternal mortality: a qualitative study from South Punjab, Pakistan. Reprod Health 2021, 18, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreau, C.; Shankar, M.; Helleringer, S.; Becker, S. Measuring unmet need for contraception as a point prevalence. BMJ Glob Health 2019, 4, e001581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hameed, W.; Azmat, S.K.; Bilgrami, M.; Ishaqe, M. Determining the factors associated with Unmet need for family planning: a cross-sectional survey in 49 districts of Pakistan. Pakistan Journal of Public Health 2011, 1, 21–27. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, A.A.; Khan, A.; Javed, W.; Hamza, H.B.; Orakzai, M.; Ansari, A.; Abbas, K. Family planning in Pakistan: applying what we have learned. J Pak Med Assoc. 2013, 63 (4 Suppl 3), S3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Population Council (PC). Landscape analysis of the family planning situation in Pakistan: Brief summary of findings. Islamabad. 2016. https://knowledgecommons.popcouncil.org/ departments_sbsr-rh/702.

Table 1.

Spatial Autocorrelation by Moran Index.

Table 1.

Spatial Autocorrelation by Moran Index.

| Indicators |

PDHS 2006-07 |

PDHS 2017-18 |

| Global Moran Index |

p-value |

Global Moran Index |

p-value |

| CPR Any Method |

0.427 |

<0.001 |

0.483 |

<0.001 |

| CPR Modern Methods |

0.339 |

<0.001 |

0.304 |

<0.001 |

| Unmet Need |

0.077 |

<0.001 |

0.165 |

0.002 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).