Submitted:

04 July 2024

Posted:

05 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical and Policy Insights

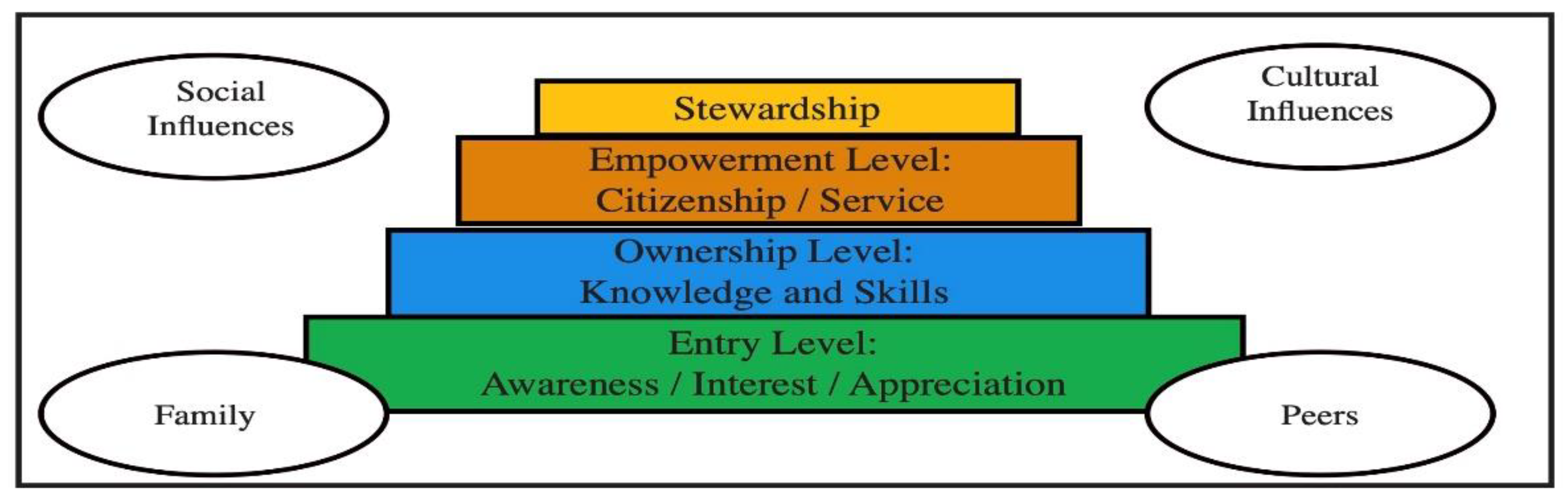

2.1. Environmental Stewardship Education: Theoretical Insights

2.2. Environmental Stewardship Education Embedding Level: Theoretical Insights

2.3. Regional and International Policy Insights on Environmental Stewardship Education

2.4. National Policy Insights on Environmental Stewardship Education

2.5. Insights on Policy Implementation

3. Materials and Methods

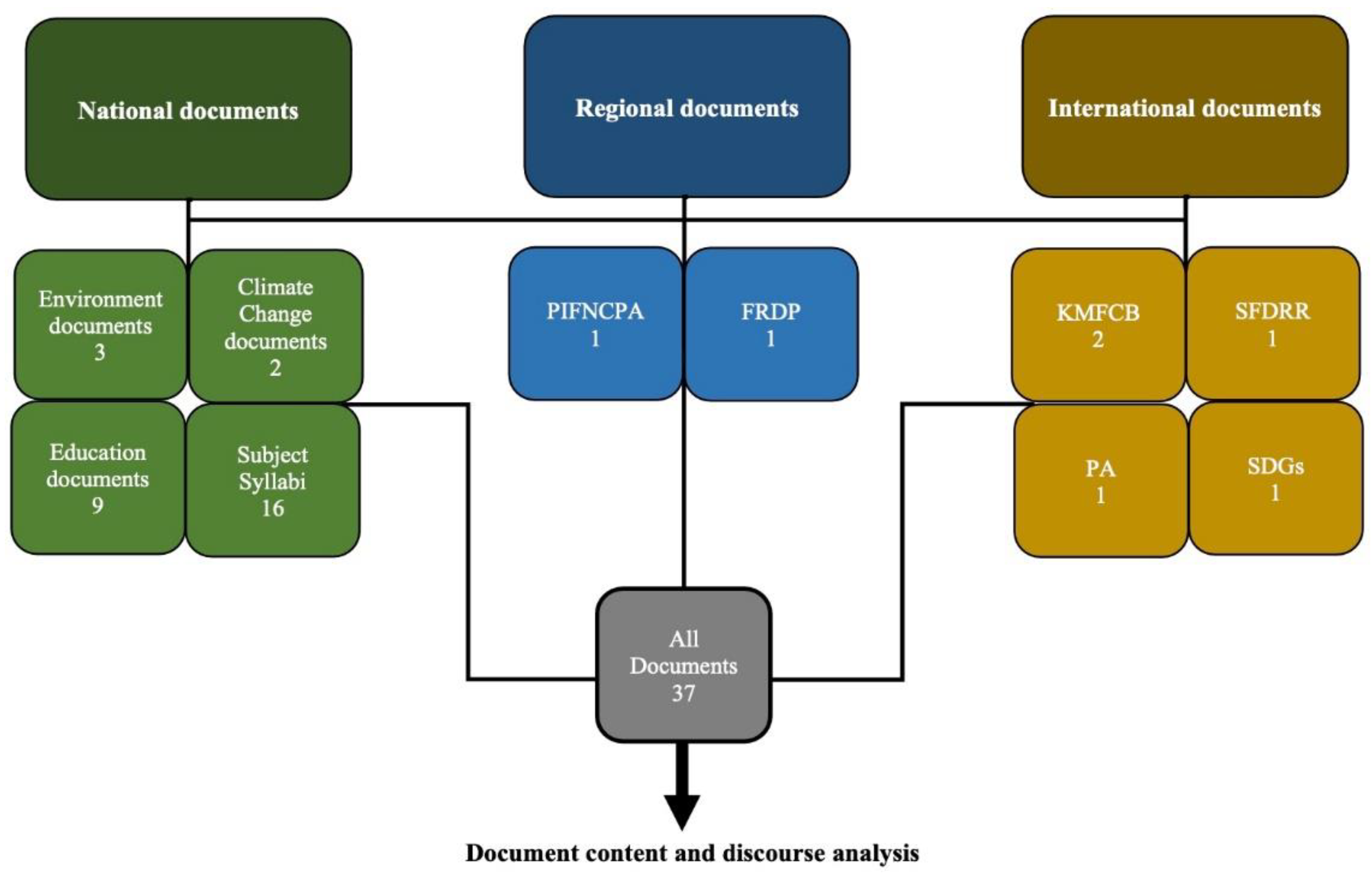

3.1. Collection of Key Documents

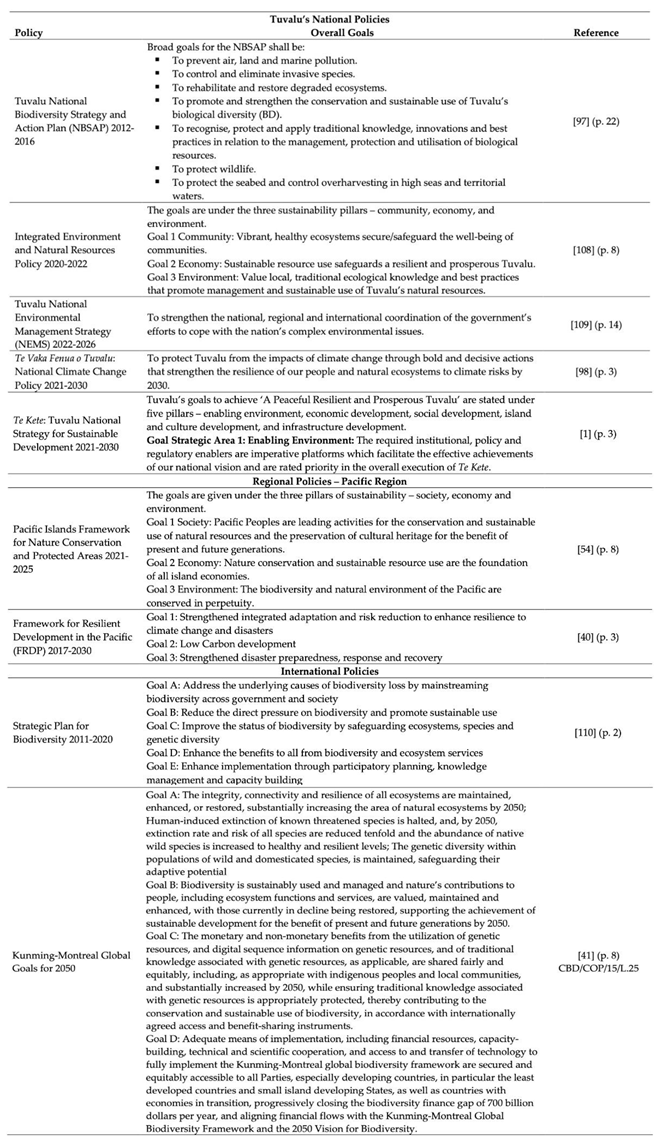

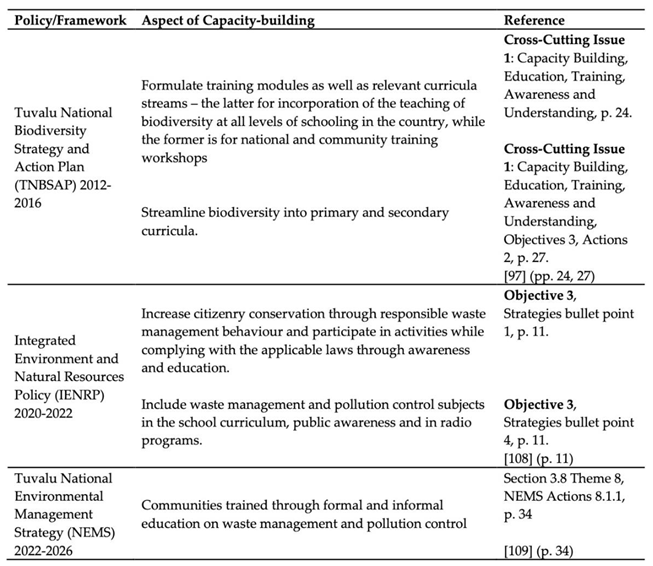

3.2. National Policies and Frameworks

3.3. The National Curriculum

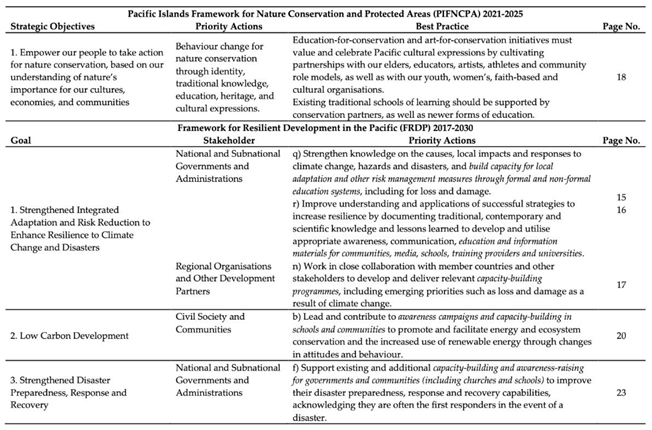

3.4. Regional Policy and Frameworks

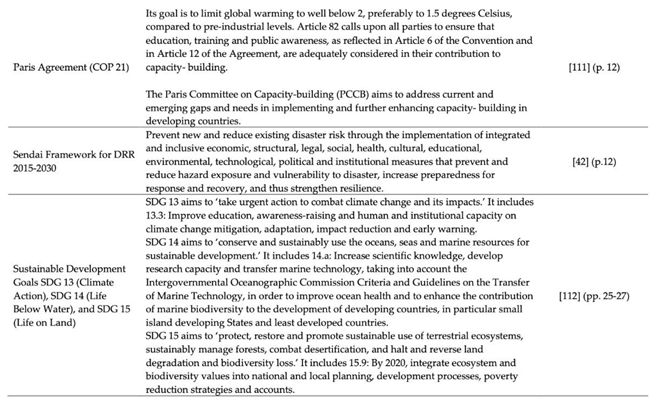

3.5. International Policies and Frameworks

3.6. Document Content and Discourse Analysis of the Policy Documents

4. Results

4.1. Environmental Stewardship Promotion in Government Education Documents

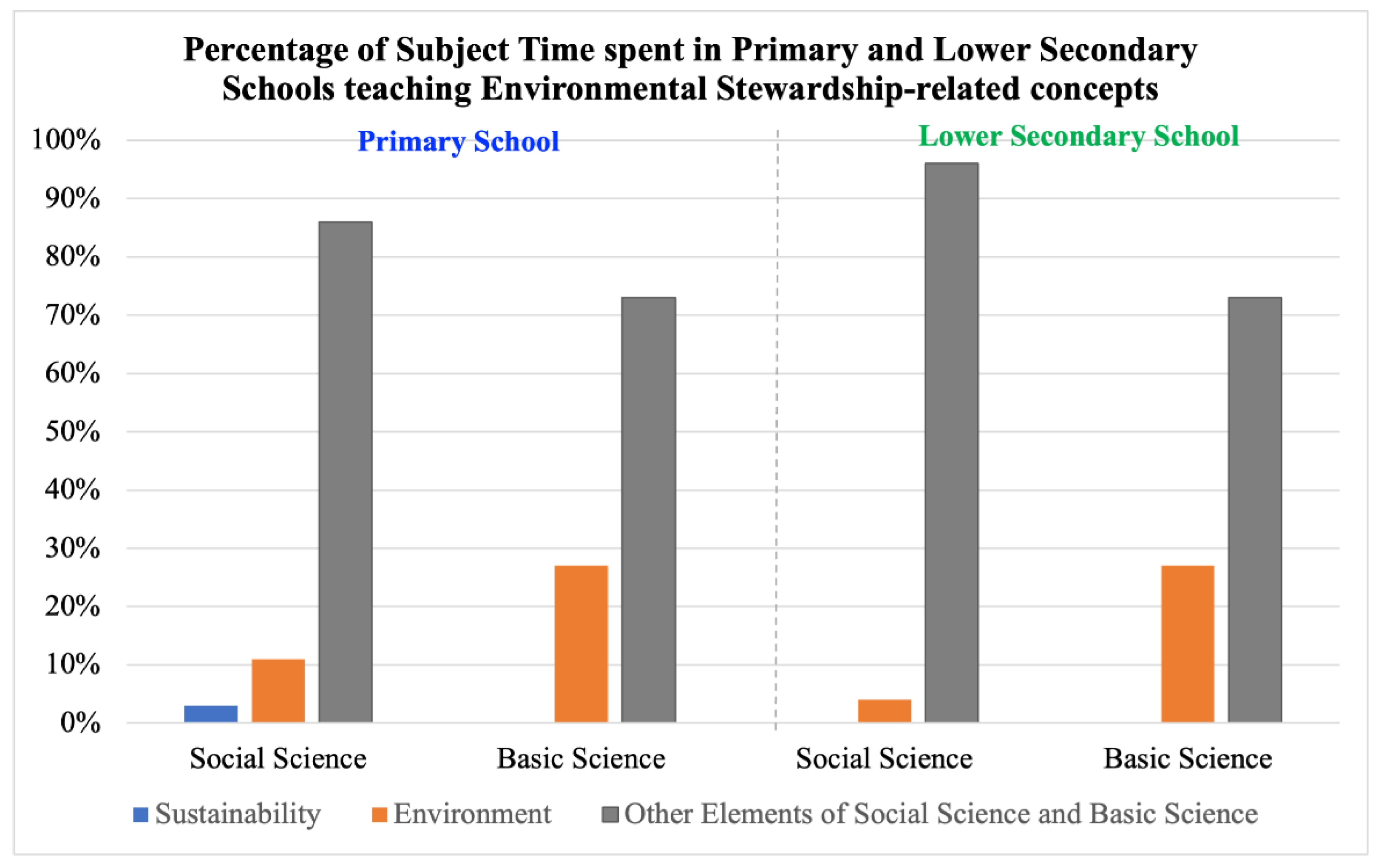

4.2. Environmental Stewardship Education in Primary and Secondary Schools Curricula

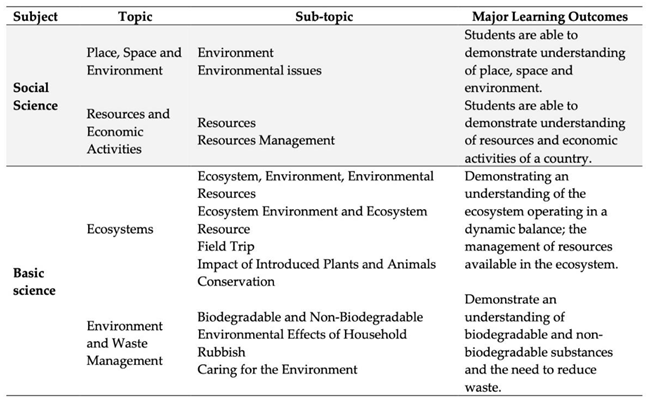

4.2.1. Primary and Lower Secondary Education (Years 1-10)

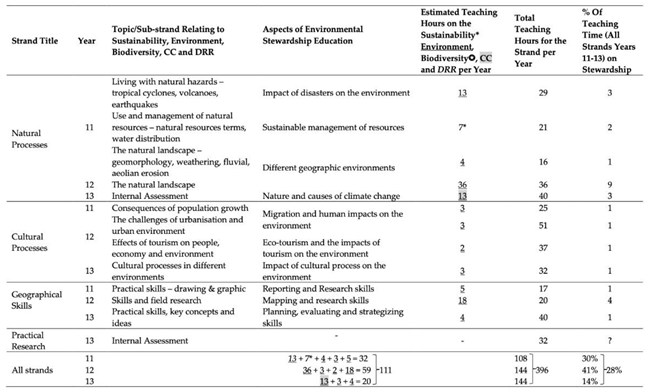

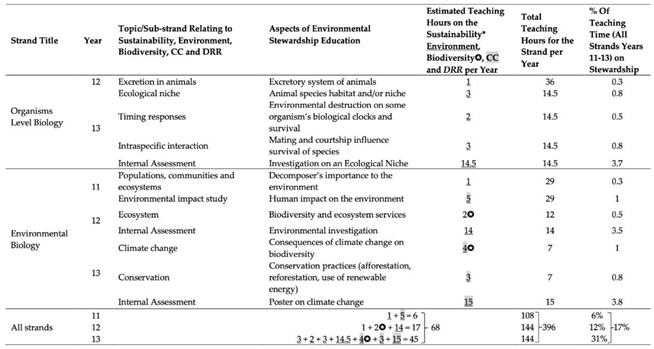

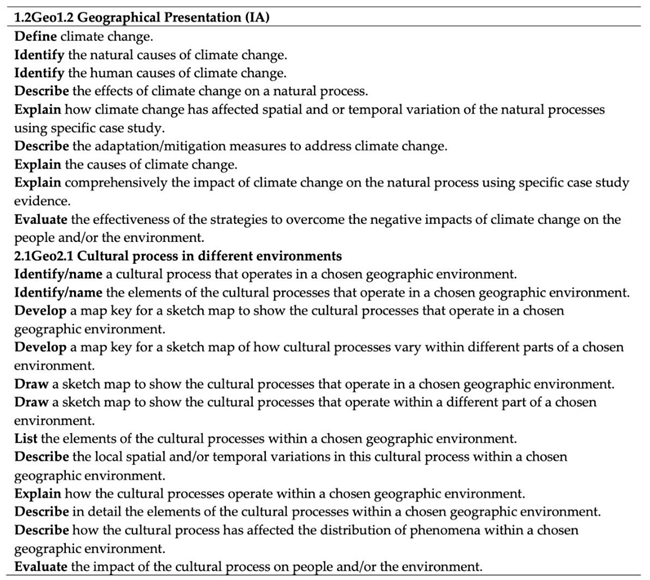

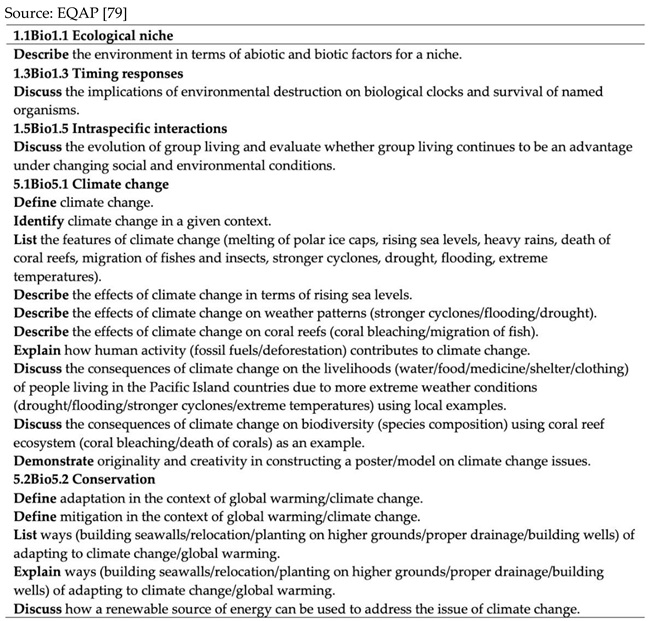

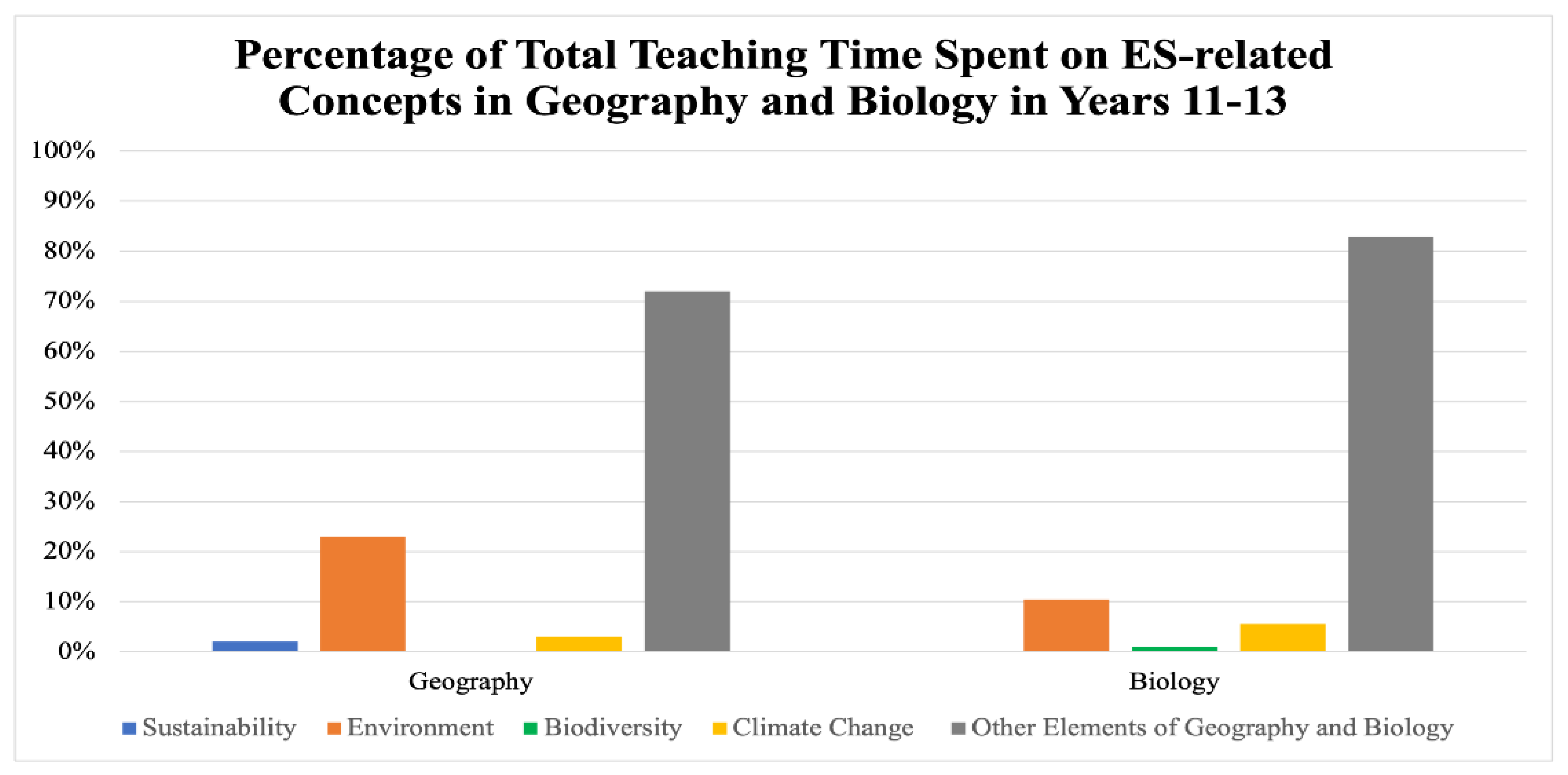

4.2.2. Upper Secondary Education (Years 11-13)

|

|

|

|

|

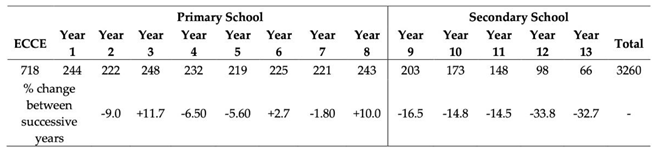

4.3. Student Attrition and Environmental Stewardship Education

|

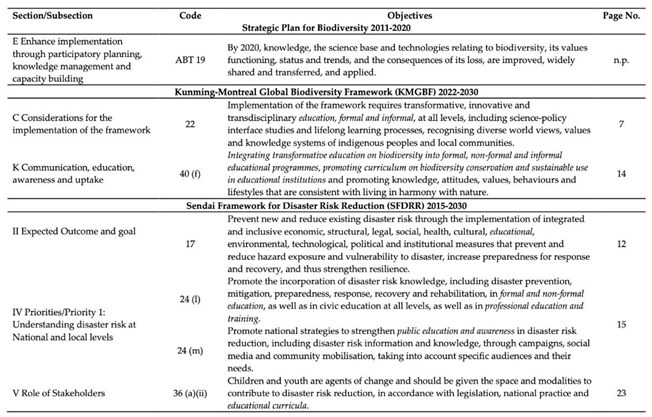

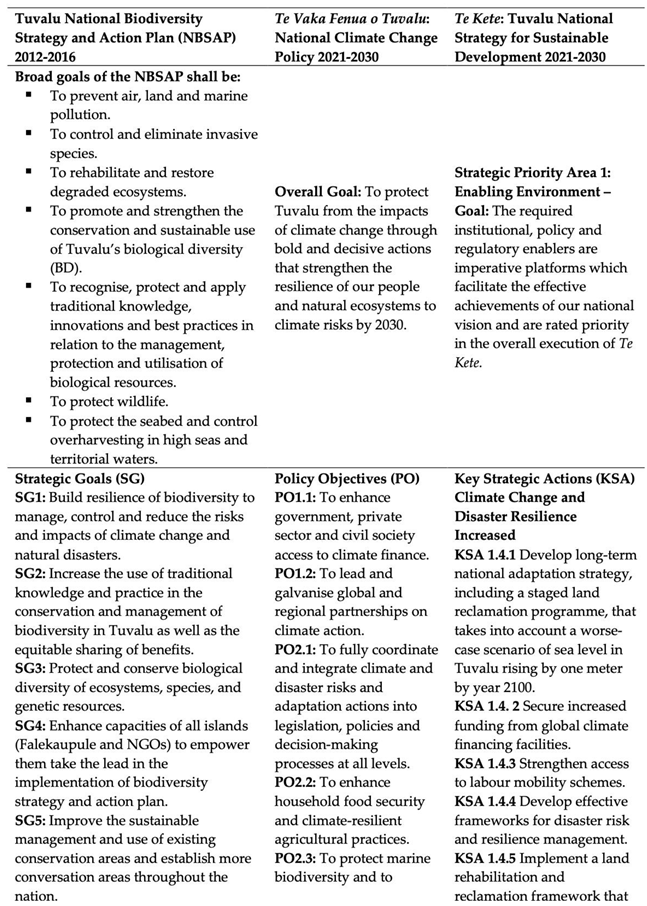

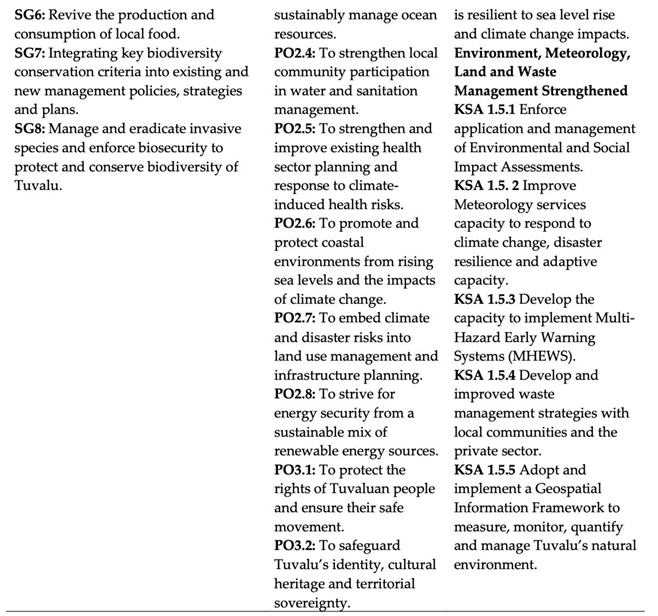

4.4. Environmental Stewardship-Related Government Policies and Frameworks

|

|

|

5. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- ▪

- Establish a consistent educational approach to environmental stewardship using both traditional (informal) and evidenced-based (formal) learning styles throughout a student’s school career.

- ▪

- An integrated national policy is needed to establish a vision for environmental education in all schools (elementary, primary, and secondary), including education about environmental protection, biodiversity conservation, climate change adaptation, and sustainability. The policy would guide future National Curriculum and assessment adjustments.

- ▪

- The national policy should take into account the importance of learning about nature (cognitive learning), learning in nature (experiential learning), and learning with nature (affective learning), and ensure that these learnings are given equal weight throughout a student’s school career.

- ▪

- MEYS should ensure curricula reflect the three types of learning in bullet point 3 to foster enhanced levels of environmental care, concern, and activist engagement in students. This involves engaging them in concrete action, an Agaziz learning to ‘study nature, not books.’

- ▪

- MEYS can be requested to ensure that environmental stewardship is covered at the age of awe and wonder at nature, as well as the level at which most Tuvaluans complete their education. Recognising the significant dropout rates in secondary education, incorporating ES into primary school curricula could serve as a strategic approach to enhance environmental consciousness and bolster capacity for environmental care and protection.

- ▪

- The Education Department should provide opportunities for teacher training programmes in EE, CC & DRR, and Biodiversity Conservation to strengthen their pedagogical skills before mainstreaming ES into the curriculum.

- ▪

- Encourage cross-sectoral educational programmes from DoE, DCC, TFD, DWM, and DoA to be held in schools during the commemoration of Environment, Climate Change, and Biodiversity Days.

Funding

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Government of Tuvalu, “Te Kete: Tuvalu National Strategy for Sustainable Development 2021-2030,” Ministry of Finance, 2020.

- R. Kattumuri, “The Commonwealth Universal Vulnerability Index: For a Global Consensus on the Definition and Measurement of Vulnerability,” 2021. Accessed: 11 January 2022. [Online]. Available: https://thecommonwealth.org/sites/default/files/inline/Universal%20Vulnerability%20Index%20Report.pdf.

- M. Aleksandrova et al., “World Risk Report: Social Protection,” 2021. Accessed: 03 March 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.preventionweb.net/publication/world-risk-report-2021-focus-social-protection.

- World Population Review. “World Population by Country 2024 (Live).” https://worldpopulationreview.com/ (accessed 01 June 2024.

- Central Statistics Division of the Government of Tuvalu, “Tuvalu 2012: Population and Housing Census Volume 1 Analytical Report,” Central Statistics Division, Funafuti, Tuvalu, 2013.

- UNDP, “Funding Proposal,” 2016. Accessed: 03 February 2022. [Online]. Available: https://tcap.tv/about-tcap.

- M. Nachmany et al., “Climate Change Legislation in Tuvalu - An excerpt from The 2015 Global Climate Legislation Study: A review of climate change legislation in 99 countries,” Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment, GLOBE International, 2015. Accessed: 14 December 2022. [Online]. Available: https://library.sprep.org/content/climate-change-legislation-tuvalu-excerpt-2015-global-climate-legislation-study-review.

- F. S. Chapin III et al., “Ecosystem stewardship: sustainability strategies for a rapidly changing planet,” Trends in Ecology and Evolution, vol. 25, no. 4, pp. 241-249, 16 June 2021 2010. [CrossRef]

- N. J. Bennett et al., “Environmental Stewardship: A Conceptual Review and Analytical Framework,” Environmental Management, vol. 61, no. 4, pp. 597-614, 27 January 2022 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Maher, “Environmental Stewardship: “Where there’s a will, is there a way?”,” Australian Journal of Environmental Education, vol. 2, pp. 7-9, 19 January 2022 1986. [Online]. Available: https://www.jstor.org/stable/45239480.

- D. J. V. Rogayan, “I Heart Nature: Perspectives of University Students on Environmental Stewardship,” International Journal on Engineering, Science and Technology, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 10-16, 12 January 2021 2019. [Online]. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Danilo-Rogayan-Jr/publication/316698512_I_heart_nature_perspectives_of_university_students_on_environmental_stewardship/links/5c87cf89a6fdcc88c39d5e0a/I-heart-nature-perspectives-of-university-students-on-environmental-stewardship.pdf.

- P. T. Seng, Stewardship Education: Best Practices Planning Guide: Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies, 2008. [Online]. Available: https://www.fishwildlife.org/application/files/5215/1373/1274/ConEd-Stewardship-Education-Best-Practices-Guide.pdf. Accessed on: 19 January 2022.

- M. Thorne and H. Whitehouse, “Environmental stewardship education in the Anthropocene (Part two): a learning for environmental stewardship conceptual framework.,” Social Educator, vol. 36, no. 1, pp. 17-28, 13 October 2022 2018. [Online]. Available: https://search.informit.org/doi/abs/10.3316/aeipt.219844.

- N. M. McGuire, “Environmental education and behavioral change: An identity-based environmental education model.,” International Journal of Environmental & Science Education, vol. 10, pp. 695-715, 21 November 2022 2015. [Online]. Available: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1081842.

- E. Gallay, L. Marckini-Polk, B. Schroeder, and C. Flanagan, “Place-Based Stewardship Education: Nurturing Aspirations to Protect the Rural Commons,” Peabody Journal of Education, vol. 91, no. 2, pp. 155-175, 16 February 2022 2016. [CrossRef]

- G. A. Smith and D. Sobel, Place-and Community-based Education in Schools, J. Spring, ed., New York: Routledge, 2010. [Online]. Available: http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/ulinc/detail.action?docID=481055. Accessed on: 19 January 2022.

- Pacific Community, “Kiwa Initiative Capacity Needs Assessment for Implementing Nature-based Solutions for Climate Change Adaptation,” Noumea, New Caledonia, 2023. Accessed: 17 April 2024. [Online]. Available: https://library.sprep.org/content/kiwa-initiative-capacity-needs-assessment-implementing-nature-based-solutions-climate.

- C. Pierce and S. Hemstock, “Resilience in Formal School Education in Vanuatu: A Mismatch with National, Regional and International Policies,” Journal of Education for Sustainable Development, vol. 15, pp. 206-233, 26 January 2023 2021. [CrossRef]

- W. F. Siemer, “Best Practices for Curriculum, Teaching, and Evaluation Components of Aquatic Stewardship Education.,” ERIC, Alexandria, VA, 2001. Accessed: 15 November 2022. [Online]. Available: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED463935.

- M. Thorne, “Learning for environmental stewardship in the Anthropocene: a study with young adolescents in the Wet Tropics,” PhD, College of Arts, Society and Education, James Cook University, Townsville, Australia, 2017. [Online]. [CrossRef]

- M. Thorne and H. Whitehouse, “Environmental stewardship education in the Anthropocene : What have we learned from recent research in North Queensland schools adjacent to the Wet Tropics?,” Social Educator, vol. 35, no. 1, pp. 17-27, 15 October 2022 2017.

- A. Benavot, “Education for Sustainable Development in Primary and Secondary Education,” University at Albany-State University of New York, New York, 3 2014. Accessed: 14 February 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/282342116_Education_for_Sustainable_Development_in_Primary_and_Secondary_Education.

- M. T. Borhan and Z. Ismail, “Promoting Environmental Stewardship through Project-Based Learning (PBL),” International Journal of Humanities and Science, vol. 1, no. 4, pp. 180-186, 31 January 2022 2011. [Online]. Available: www.ijhssnet.com.

- A. Kedrayate, “Non-formal education: Is it relevant or obsolete,” International Journal of Business, Humanities and Technology, vol. 2, no. 4, pp. 11-15, 07 January 2023 2012. [Online]. Available: http://ijbhtnet.com/journals/Vol_2_No_4_June_2012/2.pdf.

- O. O. Fafioye, M. O. Sangodapo, O. O. Aluko, and “Is formal education and environmental education a false dichotomy,” Journal of Research in Environmental Science and Toxicology, vol. 2, no. 8, pp. 150-153, 11 March 2022 2013. [Online]. Available: https://www.interesjournals.org/articles/is-formal-education-and-environmental-education-a-false-dichotomy.pdf.

- R. Hoffmann and R. Muttarak, “Greening through schooling: understanding the link between education and pro-environmental behavior in the Philippines,” Environmental Research Letters, vol. 15, no. 1, p. 014009, 28 March 2023 2020. [CrossRef]

- L. Sun, S. Yang, S. Li, and Y. Zhang, “Does education level affect individuals’ environmentally conscious behavior? Evidence from Mainland China,” Social Behavior and Personality, vol. 48, no. 9, 05 February 2023 2020. [CrossRef]

- W. Lutz, R. Muttarak, and E. Striessnig, “Universal education is key to enhanced climate adaptation,” Science, vol. 346, no. 6213, pp. 1061-1062, 27 December 2022 2014. [CrossRef]

- E. Striessnig, W. Lutz, and A. G. Patt, “Effects of educational attainment on climate risk vulnerability,” Ecology and Society, vol. 18, no. 1, 06 March 2022 2013. [CrossRef]

- P. H. Havea, A. Tamani, A. Takinana, A. De Ramon N’ Yeurt, S. L. Hemstock, and H. Jacot Des Coombes, “Addressing Climate Change at a Much Younger Age Than just at the Decision-making Level: Perceptions from Primary School Teachers in Fiji,” vol. 1, Climate Change and the Role of Education, W. L. Filho and S. L. Hemstock, Eds., Cham: Springer, 2019, pp. 149-167. [CrossRef]

- B. Prabawani, I. M. Hanika, A. Pradhanawati, and A. Budiatmo, “Primary schools eco-friendly education in the frame of education for sustainable development,” International Journal of Environmental and Science Education, vol. 12, no. 4, pp. 607-616, 01 January 2022 2017. [Online]. Available: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1144855.

- I. Harker-Schuch, “Why Is Early Adolescence So Pivotal in the Climate Change Communication and Education Arena?,” Climate Change and the Role of Education, W. L. Filho and S. L. Hemstock, Eds., 1 ed. Cham: Springer, 2019, pp. 279-290. [CrossRef]

- I. E. Harker-Schuch, F. P. Mills, S. J. Lade, and R. M. Colvin, “CO2peration – Structuring a 3D interactive digital game to improve climate literacy in the 12-13-year-old age group,” Computers & Education, vol. 144, p. 103705, 17 February 2023 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Aklin, P. Bayer, S. P. Harish, and J. Urpelainen, “Understanding environmental policy preferences: New evidence from Brazil,” Ecological Economics, vol. 94, pp. 28-36, 17 February 2023 2013. [CrossRef]

- N. Taylor et al., “Education for sustainability in the Secondary Sector—A review,” Journal of Education for Sustainable Development, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 102-122, 17 February 2023 2019. [CrossRef]

- L. Chawla and D. F. Cushing, “Education for Strategic Environmental Behavior,” Environmental Education Research, vol. 13, no. 4, pp. 437-452, 05 February 2023 2007. [CrossRef]

- C. Wilson, “Effective approaches to connect children with nature: Principles for effectively engaging children and young people with nature,” Department of Conservation, New Zealand, 2011. Accessed: 01 January 2022. [Online]. Available: http://www.doc.govt.nz/Documents/getting-involved/students-and-teachers/effective-approaches-to-connect-children-with-nature.pdf.

- E. Ferris, M. M. Cernea, and D. Petz, “On the front line of climate change and displacement: Learning from and with Pacific Island Countries,” The Brookings Institution - London School of Economics Project on Internal Displacement, London, 13 June 2023 2011. [Online]. Available: https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/09_idp_climate_change.pdf.

- UNFCCC, “Report of the Conference of the Parties on its twenty-first session, held in Paris from 30 November to 13 December 2015,” FCCC/CP/2015/10, Annex 2 Decision 1/CP.21. Distr.: General 29 January 2016, 2016. Accessed: 11 December 2023. [Online]. Available: https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2015/cop21/eng/10.pdf.

- Pacific Community, Secretariat of the Pacific Regional Environment Programme, Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat, United Nations Development Programme, United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction, and University of the South Pacific, “Framework for Resilient Development in the Pacific: An Integrated Approach to Address Climate Change and Disaster Risk Management (FRDP) 2017 - 2030,” Suva, Fiji, 2016. Accessed: 29 January 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.resilientpacific.org/en/framework-resilient-development-pacific.

- COP 15, “Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework 2022-2030: Draft decision submitted by the President,” presented at the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity Fifteenth Meeting (COP), Montreal, Canada, 7-19 December, 2022, CBD/COP/15/L.25. [Online]. Available: https://www.cbd.int/conferences/2021-2022/cop-15/documents.

- UNDRR, “Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030,” Geneva, 2015. Accessed: 19 December 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.undrr.org/publication/sendai-framework-disaster-risk-reduction-2015-2030.

- UNDESA, “Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development,” New York, 2015. Accessed: 19 December 2022. [Online]. Available: https://sdgs.un.org/publications/transforming-our-world-2030-agenda-sustainable-development-17981.

- UNEP, “The Belgrade Charter: A Framework for Environmental Education,” presented at the International Workshop on Environmental Education, Belgrade, Serbia, 13-22 October, 1975. [Online]. Available: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000017772?posInSet=28&queryId=1d318d21-66f2-4dd0-ad75-5c7d32912852.

- UNESCO, “United Nations Decade of Education for Sustainable Development, 2005-2014: Draft International Implementation Scheme,” presented at the 59th session of the UN General Assembly, New York, 18-19 October 2004, 2005. [Online]. Available: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000139937.

- S. Bramwell-Lalor, K. Kelly, T. Ferguson, C. H. Gentles, and C. Roofe, “Project-based Learning for environmental sustainability action,” Southern African journal of environmental education, vol. 36, pp. 57-71, 19 February 2023 2020. [CrossRef]

- K. A. Fischer, “Cultivating Environmental Stewardship in Middle School Students,” MSc, Ann Arbor, MI, 2011. [Online]. Available: https://www.proquest.com/openview/7bca90d28bde6dd6a4aa5d1e72a315a6/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750.

- C. Roofe and T. Ferguson, “Technical and Vocational Education and Training Curricula at the Lower Secondary Level in Jamaica: A Preliminary Exploration of Education for Sustainable Development Content,” Discourse and Communication for Sustainable Education, vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 93-110, 18 February 2023 2018. [CrossRef]

- J. Fien and D. Wilson, “Promoting sustainable development in TVET: the Bonn Declaration,” Prospects, vol. XXXV, no. 3, pp. 273-288, 20 February 2023 2005. [CrossRef]

- OECD, “Priority areas for action in education and skills formation,” vol. 3, OECD Development Pathways: Multi-dimensional Review of Paraguay : Volume 3. From Analysis to Action PARAGUAYrue André Pascal, Paris: OECD, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/6bed6af4-en/index.html?itemId=/content/component/6bed6af4-en.

- Paryono, “The importance of TVET and its contribution to sustainable development,” presented at the Green Construction and Engineering Education for Sustainable Development:AIP Conference Proceedings, East Java, Indonesia, 8-9 August, 2017. [CrossRef]

- APTC, “How TVET Change Happens: Tuvalu Stakeholder Perspectives,” Australia Pacific Training Coalition: Creating Skills For Life, Suva, Fiji, 11 2019. Accessed: 27 October 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.aptc.edu.au/docs/default-source/how-tvet-change-happens/how_tvet_change_happens_tuvalu_stakeholder-perspectives.pdf?sfvrsn=666d6743_2#:~:text=This%20change%20would%20mean%20that,provision%20of%20scholarships%20for%20training.

- S. Raturi, “Education Development Challenges and Potential for Flexible and Open Learning in Tuvalu for Department of Education Ministry of Education Youth and Sports,” Burnaby, Canada, 2016. Accessed: 01 April 2022. [Online]. Available: http://oasis.col.org/handle/11599/2665.

- SPREP, “Pacific Islands Framework for Nature Conservation and Protected Areas 2021-2025,” Apia, Samoa, 2021. Accessed: 24 December 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.sprep.org/pirt/framework-for-nature-conservation-and-protected-areas-in-the-pacific-islands-region-2021-2025.

- Government of Tuvalu, “Tuvalu National Curriculum Policy Framework,” Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports, Funafuti, Tuvalu, 2019. Accessed: 20 November 2021. [Online]. Available: https://meys.gov.tv/publication.

- UNDRR, “Midterm Review of the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030: Pacific Regional Synthesis Report,” United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction, Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. Accessed: 17 April 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.undrr.org/publication/subregional-report-midterm-review-implementation-sendai-framework-disaster-risk-0.

- S. Hemstock and R. Smith, “The Impacts of International Aid on the Energy Security of Small Island Developing States (SIDS): A case study of Tuvalu,” Central European Journal of Internatiional and Security Studies, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 81-102, 25 January 2022 2012. [Online]. Available: https://irep.ntu.ac.uk/id/eprint/1225/.

- A. Atteridge and N. Canales, Climate finance in the Pacific: An overview of flows to the region’s Small Island Developing States, Stockholm, Sweden: Stockholm Environment Institute., 2017. [Online]. Available: https://mediamanager.sei.org/documents/Publications/Climate/SEI-WP-2017-04-Pacific-climate-finance-flows.pdf. Accessed on: 21 April 2024.

- UNDRR, “Major Development Partner Funded Projects in the Pacific Island Countries & Territories (PICT) Disaster Risk Reduction & Climate Change. Annex II of the Midterm Review of the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030: Pacific Regional Sythesis Report,” United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction, Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.

- OECD, “Geographical Distribution of Financial Flows to Developing Countries 2021: Disbursements, Commitments, Country Indicators,” OECD, 9789264828070, 29 June 2022 2021. Accessed: 29 June 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Smith and S. Hemstock, “An Analysis of the Effectiveness of Funding for Climate Change Adaptation Using Tuvalu as a Case Study,” The International Journal of Climate Change: Impacts and Responses, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 67-78z, 25 January 2022 2012. [CrossRef]

- E. P. Marpa, “Navigating Environmental Education Practices to Promote Environmental Awareness and Education.,” International Journal on Studies in Education, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 45-57, 04 April 2023 2020.

- M. Glackin and H. King, “Understanding Environmental Education in Secondary Schools in England. Report 1: Perspectives from Policy,” King’s College London, 2018. Accessed: 31 May 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/328214640.

- Government of Tuvalu, “Basic Science Syllabus Year 6,” Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports, Tuvalu, 2017.

- Government of Tuvalu, “Basic Science Syllabus Year 7,” Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports, Tuvalu, 2017.

- Government of Tuvalu, “Basic Science Syllabus Year 8,” Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports, Tuvalu, 2017.

- Government of Tuvalu, “Basic Science Syllabus Year 9,” Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports, Tuvalu, 2017.

- Government of Tuvalu, “Basic Science Syllabus Year 10,” Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports, Tuvalu, 2017.

- Government of Tuvalu, “Social Science Syllabus Year 6,” Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports, Tuvalu, 2017.

- Government of Tuvalu, “Social Science Syllabus Year 7,” Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports, Tuvalu, 2017.

- Government of Tuvalu, “Social Science Syllabus Year 8,” Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports, Tuvalu, 2017.

- Government of Tuvalu, “Social Science Syllabus Year 9,” Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports, Tuvalu, 2017.

- Government of Tuvalu, “Social Science Syllabus Year 10,” Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports, Tuvalu, 2017.

- Government of Tuvalu, “Geography Syllabus Year 11,” Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports, Tuvalu, 2017.

- Government of Tuvalu, “Geography Syllabus Year 12,” Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports, Tuvalu, 2017.

- EQAP, South Pacific Form Seven Certificate [SPFSC]: Geography Syllabus, 5 ed.: Pacific Community (SPC), 2020.

- Government of Tuvalu, “Biology Syllabus Year 11,” Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports, Tuvalu, 2017.

- Government of Tuvalu, “Biology Syllabus and Prescription Year 12,” MEYS Tuvalu and EQAP, Tuvalu, 2022.

- EQAP, South Pacific Form Seven Certificate [SPFSC]: Biology Syllabus, 5 ed. Suva, Fiji: The Pacific Community (SPC), 2020.

- C. Cardno, “Policy Document Analysis: A Practical Educational Leadership Tool and a Qualitative Research Method.,” Kuram ve Uygulamada Eğitim Yönetimi, vol. 24, no. 4, pp. 623-640, 21 December 2022 2018. [CrossRef]

- J. Perryman, “Discourse analysis,” in Research Methods in Educational Leadership and Management, B. Ann, C. Marianne, and M. Marlene Eds., 3 ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2012, pp. 309-322.

- K. Aikens, M. McKenzie, and P. Vaughter, “Environmental and sustainability education policy research: a systematic review of methodological and thematic trends,” Environmental Education Research, vol. 22, no. 3, pp. 333-359, 28 March 2023 2016. [CrossRef]

- Government of Tuvalu, “Tuvalu Education Sector Plan III (TESP III) 2016-2020,” Ministry of Education Youth and Sports, Funafuti, Tuvalu, 10 2016. Accessed: 24 November 2021. [Online]. Available: https://meys.gov.tv/publication.

- Government of Tuvalu, “Tuvalu Education Sector Situational Analysis,” Ministry of Education Youth and Sports, Funafuti, Tuvalu, 2017. Accessed: 22 November 2021. [Online]. Available: https://meys.gov.tv/publication.

- Government of Tuvalu, “Tuvalu National Curriculum Policy Framework,” Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports, Funafuti, Tuvalu, 2013. Accessed: 25 November 2021. [Online]. Available: https://meys.gov.tv/publication.

- Government of Tuvalu, “2016 & 2017 Education Statistical Report,” Funafuti, Tuvalu, 2017. Accessed: 22 November 2021. [Online]. Available: https://meys.gov.tv/statistics.

- Government of Tuvalu, “2022 School Calendar,” Ministry of Education Youth and Sports (MEYS), Funafuti, Tuvalu, 2022.

- J. Moore, “Barriers and pathways to creating sustainability education programs: policy, rhetoric and reality,” Environmental Education Research, vol. 11, pp. 537-555, 22 January 2023 2005. [CrossRef]

- M. Varela-Losada, P. Vega-Marcote, U. Pérez-Rodríguez, and M. Álvarez-Lires, “Going to action? A literature review on educational proposals in formal Environmental Education.,” vol. 22, pp. 390-421, 25 November 2023 2016. [CrossRef]

- G. Karareba and C. Baillie, “Community engineering education: The case of post-conflict Rwanda,” Education, Citizenship and Social Justice, vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 211-224, 25 May 2021 2019. [CrossRef]

- D. C. Bennett, G. H. Cornwell, H. J. Al-Lail, and C. Schenck, “An Education for the Twenty-First Century: Stewardship of the Global Commons,” Liberal Education, vol. 98, no. 4, pp. 34-41, 23 May 2023 2012. [Online]. Available: https://gustavus.edu/kendallcenter/teaching-programs-and-resources/documents/2013PDFAnEducationfortheTwenty-FirstCentury.pdf.

- S. Tane, “Tuvalu School Enrolment in Each Level [email]. Sent to S. Tinilau, 02 February,” ed, 2023.

- Education Department, “Education Statistical Report 2012,” Funafuti, Tuvalu, 2012. Accessed: 27 January 2023. [Online]. Available: https://meys.gov.tv/publication.

- R. Ballantyne and J. Packer, “Introducing a fifth pedagogy: experience-based strategies for facilitating learning in natural environments,” vol. 15, no. 2, pp. 243-262, 23 May 2023 2009. [CrossRef]

- Z. T. Salter, “Impact of Whole-School Education for Sustainability on Upper-Primary Students and their Families,” PhD, The University of Western Australia, Western Australia, 2013. [Online]. Available: https://research-repository.uwa.edu.au/en/publications/impact-of-whole-school-education-for-sustainability-on-upper-prim.

- N. Taylor, F. Quinn, and C. Eames, “Why do We Need to Teach Education for Sustainability at the Primary Level?,” Educating for Sustainability in Primary Schools: Teaching for the Future, N. Taylor, F. Quinn, and C. Eames, Eds.: SensePublishers, 2015, pp. 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Government of Tuvalu, “Tuvalu National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan 2012-2016,” 2012. Accessed: 20 November 2021. [Online]. Available: https://tuvalu-data.sprep.org/dataset/national-biodiversity-strategy-and-action-plan-2012-2016.

- (2021). Te Vaka Fenua o Tuvalu: National Climate Change Policy 2021-2030.

- J. Schneiderhan-Opel and F. X. Bogner, “FutureForest: Promoting Biodiversity Literacy by Implementing Citizen Science in the Classroom,” The American Biology Teacher, vol. 82, no. 4, 05 September 2022 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. Amri, J. A. Lassa, Y. Tebe, N. R. Hanifa, J. Kumar, and S. Sagala, “Pathways to Disaster Risk Reduction Education integration in schools: Insights from SPAB evaluation in Indonesia,” International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, vol. 73, p. 102860, 21 April 2024 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. R. Prasad and R. L. Mkumbachi, “University students’ perceptions of climate change: the case study of the University of the South Pacific-Fiji Islands,” International Journal of Climate Change Strategies and Management, vol. 13, no. 4/5, pp. 416-434, 02 January 2023 2021.

- G. Potter, “Environmental Education for the 21st Century: Where Do We Go Now?,” vol. 41, pp. 22-33, 25 January 2023 2009. [CrossRef]

- International Monetary Fund, “IMF Country Report No. 21/176,” Washington DC, USA, 2021.

- A. Craney, “Seeking a Panacea: Attempts to Address the Failings of Fiji and Solomon Islands Formal Education in Preparing Young People for Livelihood Opportunities,” The Contemporary Pacific, vol. 33, no. 2, pp. 338-362, 06 January 2023 2021. [CrossRef]

- F.-L. T. Yu, “Outcomes-based education: a subjectivist critique,” International Journal of Educational Reform, vol. 25, no. 3, pp. 319-333, 6 2016. [Online]. Available: https://proxy.library.lincoln.ac.uk/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edsgao&AN=edsgcl.503641942&site=eds-live.

- M. E. Krasny and B. DuBois, “Climate adaptation education: embracing reality or abandoning environmental values.,” Environmental Education Research, vol. 25, no. 6, pp. 883-894, 10 March 2022 2019. [CrossRef]

- K. M. Schmitt et al., “Beyond Planning Tools: Experiential Learning in Climate Adaptation Planning and Practices,” Climate, vol. 9, no. 5, p. 76, 11 July 2023 2021. [CrossRef]

- Government of Tuvalu, “Integrated Environment and Natural Resources Policy 2020-2022,” 2019.

- Secretariat of the Pacific Regional Environment Programme, “Tuvalu National Environment Management Strategy (NEMS) 2022-2026,” Apia, Samoa, 978-982-04-1125-8, 2022. Accessed: 25 November 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.sprep.org/news/tuvalu-launches-state-of-environment-report-and-national-environment-management-strategy.

- UNCBD, “Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011-2020, including Aichi Biodiversity Targets,” 2011. Accessed: 19 December 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.cbd.int/sp/.

- UFCCC, “Report of the Conference of the Parties on its twenty-first session, held in Paris from 30 November to 13 December 2015 - Addendum - Part two: Action taken by the Conference of the Parties at its twenty-first session,” FCCC/CP/2015/10/Add.1, Distr.: General 29 January 2016, 2016. Accessed: 11 December 2023. [Online]. Available: https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/conferences/past-conferences/paris-climate-change-conference-november-2015/cop-21/cop-21-decisions.

- UNDESA, “Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development,” New York, 2015. Accessed: 19 December 2022. [Online]. Available: https://sdgs.un.org/publications/transforming-our-world-2030-agenda-sustainable-development-17981.

| Year | Document - Author | ES | Sus | Env | BD | CC | DRR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | Early Childhood Care and Education Policy 2007 – Government of Tuvalu | 0 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2009 | National Education Polciy – Government of Tuvalu | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2011 | Tuvalu Education Sector Plan II (TESP II) 2011 -2015 – Government of Tuvalu | 0 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2013 | Tuvalu National Curriculum Policy Framework (TNCPF 2013): Quality Education for sustainable living for all – Government of Tuvalu | 0 | 31 | 28 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2013 | Tuvalu MDG Acceleration Framework: Improving Quality Education – Government of Tuvalu | 0 | 43 | 8 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| 2015 | Education for All 2015 National Review Report: Tuvalu – Government of Tuvalu | 0 | 21 | 20 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| 2016 | Tuvalu Education Sector Plan III (TESP III) 2016-2020 – Government of Tuvalu | 0 | 25 | 7 | 0 | 17 | 8 |

| 2017 | Tuvalu Education Sector Situational Analysis – Government of Tuvalu | 0 | 9 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| 2019 | Tuvalu National Curriculum Policy Framework (TNCPF 2019): Quality Education for sustainable living for all – Government of Tuvalu | 0 | 29 | 26 | 0 | 5 | 0 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).