Submitted:

07 July 2024

Posted:

08 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- a systematic review and meta-analysis of the association between mental disorders in inmates and placement into disciplinary confinement in correctional setting compared to in inmates without any mental disorder.

- a systematic review on the effects of disciplinary confinement in correctional setting on the mental health of inmates with or without pre-existing psychiatric conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategies

2.2. Study Eligibility

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

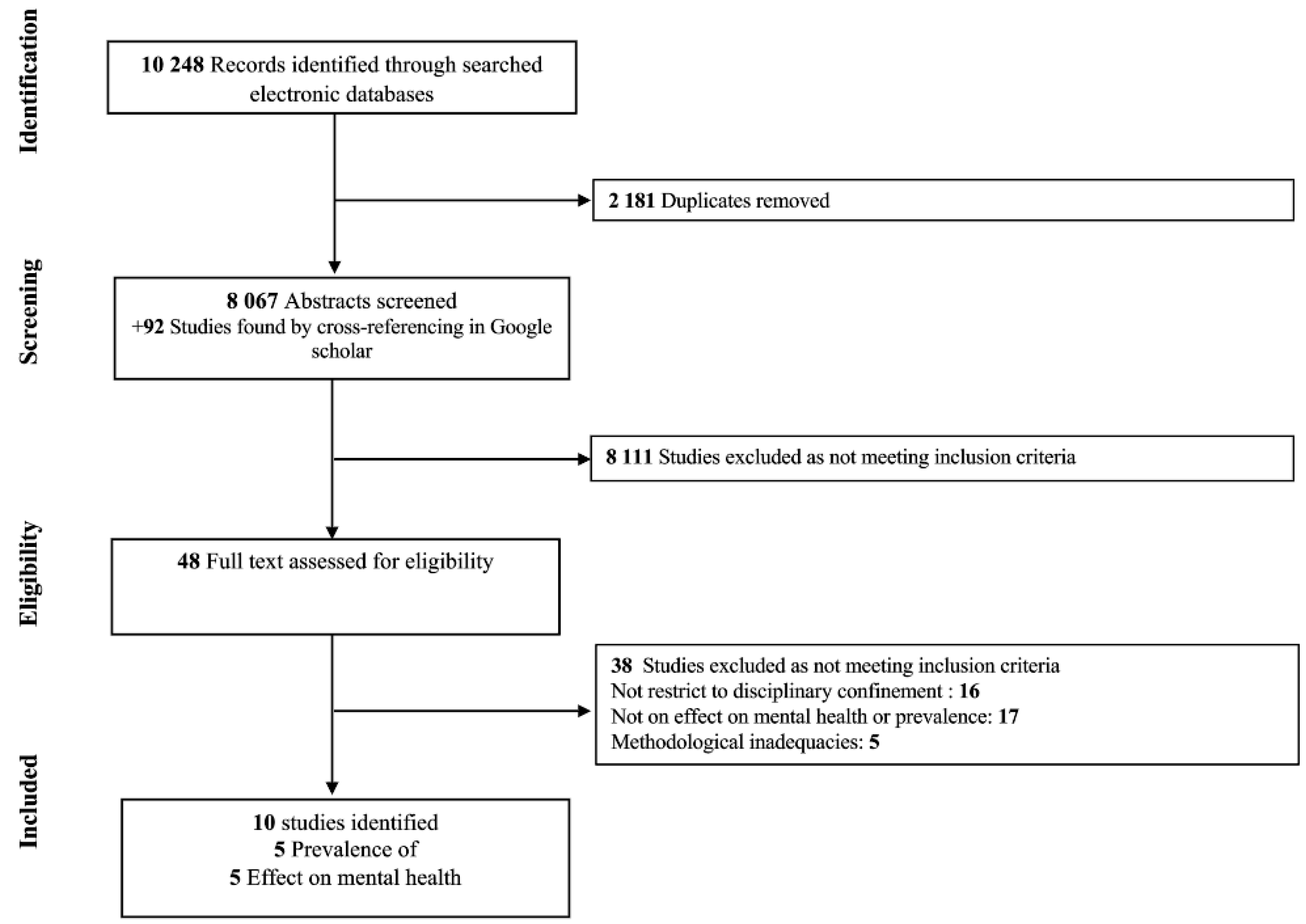

3.1. Description of Studies

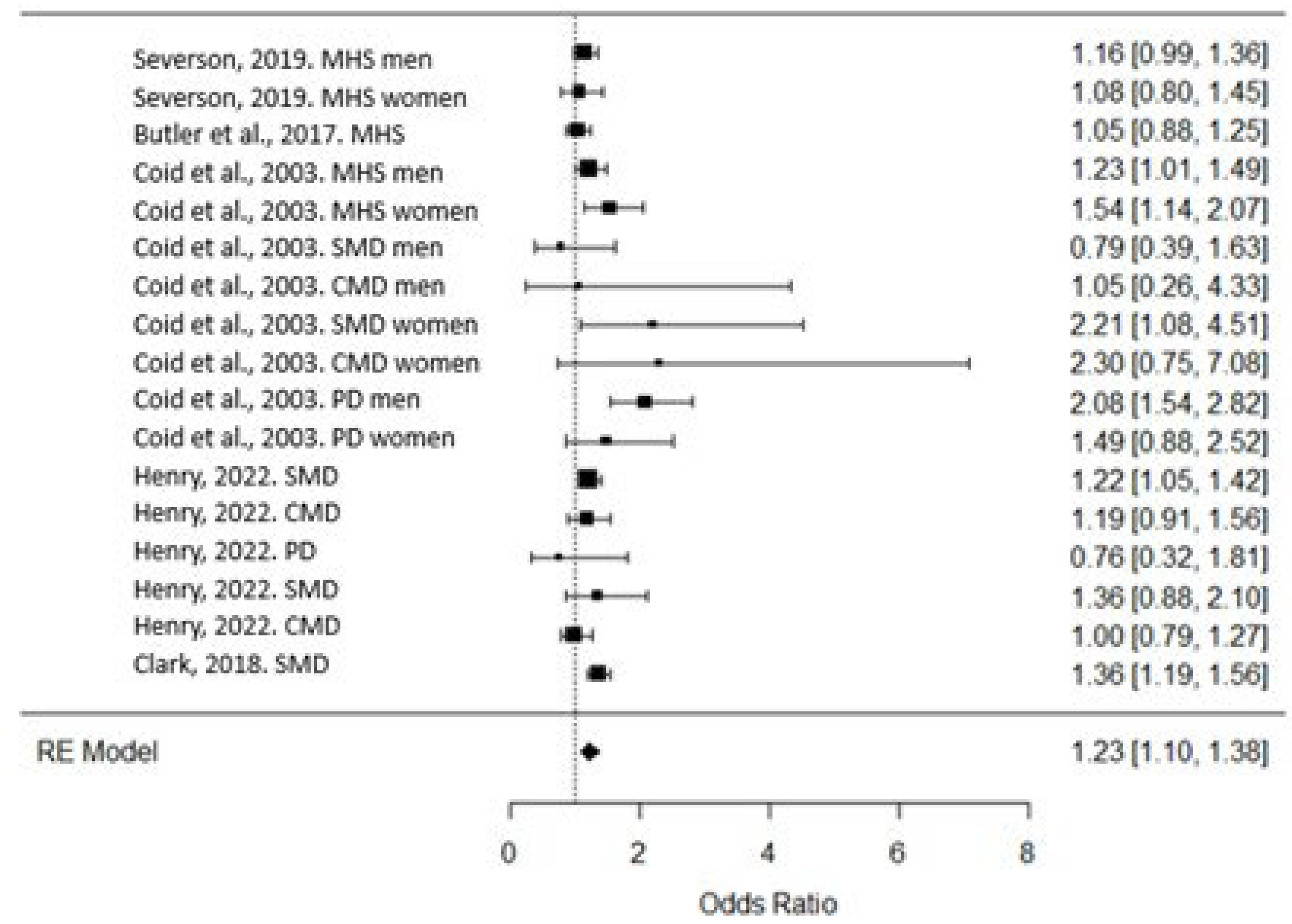

3.2. Association of Mental Health in Disciplinary Confinement

3.3. Effects of Disciplinary Confinement on Mental Health

3.3.1. Psychological Distress and Psychiatric Symptoms

3.3.2. Mental Health Services and Hospitalizations

3.3.3. Self Harm

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Al-Rousan, T.; et al. Inside the nation’s largest mental health institution: a prevalence study in a state prison system. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, A.; et al. Prevalence of Mental Health Needs, Substance Use, and Co-occurring Disorders Among People Admitted to Prison. Psychiatr Serv 2022, 73, 737–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennion, E. Banning the bing: Why extreme solitary confinement is cruel and far too usual punishment. Ind. LJ 2015, 90, 741. [Google Scholar]

- Torrey, E.F.; Kennard, A.D.; Eslinger, D.; Lamb, R.; Pavle, J. More mentally ill persons are in jails and prisons than hospitals: A survey of the states; Treatment Advocacy Center: Arlington, VA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Fazel, S.; et al. Mental health of prisoners: prevalence, adverse outcomes, and interventions. Lancet Psychiatry 2016, 3, 871–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’keefe, M.L.; Schnell, M.J. Offenders with mental illness in the correctional system. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation 2007, 45, 81–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fellner, J. A corrections quandary: Mental illness and prison rules. Harv. CR-CLL Rev. 2006, 41, 391. [Google Scholar]

- Craig, S.C. Rehabilitation versus control: An organizational theory of prison management. The Prison Journal 2004, 84 4_suppl, 92S–114S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalev, S. Supermax: Controlling risk through solitary confinement; Willan, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mears, D.P.; Castro, J.L. Wardens’ views on the wisdom of supermax prisons. Crime & Delinquency 2006, 52, 398–431. [Google Scholar]

- Shames, A.; Wilcox, J.; Subramanian, R. Solitary confinement: Common misconceptions and emerging safe alternatives; ERA Institute: New York, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Simes, J.T.; Western, B.; Lee, A. Mental health disparities in solitary confinement. Criminology 2022, 60, 538–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, H.D.; Steiner, B. Examining the use of disciplinary segregation within and across prisons. Justice Quarterly 2017, 34, 248–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, H.D.; et al. An examination of the influence of exposure to disciplinary segregation on recidivism. Crime & Delinquency 2020, 66, 485–512. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, R.G. Exploring the effect of exposure to short-term solitary confinement among violent prison inmates. Journal of Quantitative Criminology 2016, 32, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, Y.; et al. Disciplinary segregation’s effects on inmate behavior: Institutional and community outcomes. Criminal Justice Policy Review 2020, 31, 1036–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, J.W.; Jones, M.A. An analysis of the deterrent effects of disciplinary segregation on institutional rule violation rates. Criminal Justice Policy Review 2019, 30, 765–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, R.D.; et al. Quantitative syntheses of the effects of administrative segregation on inmates’ well-being. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law 2016, 22, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luigi, M.; et al. Shedding light on “the hole”: A systematic review and meta-analysis on adverse psychological effects and mortality following solitary confinement in correctional settings. Frontiers in Psychiatry 2020, 11, 840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houser, K.; Belenko, S. Disciplinary responses to misconduct among female prison inmates with mental illness, substance use disorders, and co-occurring disorders. Psychiatr Rehabil J 2015, 38, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dellazizzo, L.; et al. Is mental illness associated with placement into solitary confinement in correctional settings? A systematic review and meta-analysis. International journal of mental health nursing 2020, 29, 576–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, H.A.; Young, G.R. Prison segregation: Administrative detention remedy or mental health problem? Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health 1997, 7, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labrecque, R.M.; Mears, D.P.; Smith, P. Gender and the effect of disciplinary segregation on prison misconduct. Criminal Justice Policy Review 2020, 31, 1193–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, N.A.; Monteiro, C.E. Administrative segregation in US prisons. Restrictive housing in the US: Issues, challenges, and future directions, 2016: p. 1-48.

- Wooldredge, J.; et al. Disparities in Segregation for Prison Control: Comparing Long Term Solitary Confinement to Short Term Disciplinary Restrictive Housing. Justice Quarterly 2023, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wildeman, C.; Andersen, L.H. Long-term consequences of being placed in disciplinary segregation. Criminology 2020, 58, 423–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, B.F. Disparities in use of disciplinary solitary confinement by mental health diagnosis, race, sexual orientation and sex: Results from a national survey in the United States of America. Criminal behaviour and mental health 2022, 32, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Severson, R.E. Gender differences in mental health, institutional misconduct, and disciplinary segregation. Criminal Justice and Behavior 2019, 46, 1719–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coid, J.; et al. Psychiatric morbidity in prisoners and solitary cellular confinement, I: Disciplinary segregation. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology 2003, 14, 298–319. [Google Scholar]

- Wynn, J.R. Psychopathology in supermax prisons: A New York state study; City University of New York, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kaba, F.; et al. Solitary confinement and risk of self-harm among jail inmates. American journal of public health 2014, 104, 442–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyatt, G.H.; et al. GRADE guidelines: 4. Rating the quality of evidence—study limitations (risk of bias). Journal of clinical epidemiology 2011, 64, 407–415. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst Rev 2021, 10, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Team, R.D.C. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. (No Title), 2010.

- Viechtbauer, W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. Journal of statistical software 2010, 36, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, R.; DiMatteo, M.R. Meta-analysis: Recent developments in quantitative methods for literature reviews. Annual review of psychology 2001, 52, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.; et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. Bmj 2003, 327, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipsey, M.W.; Wilson, D.B. Practical meta-analysis; SAGE publications, Inc, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, H.; Hedges, L.V.; Valentine, J.C. The handbook of research synthesis and meta-analysis; Russell Sage Foundation, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders : dsm-5-tr (Fifth edition, text revision); American Psychiatric Association Publishing, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, K. The effect of mental illness on segregation following institutional misconduct. Criminal Justice and Behavior 2018, 45, 1363–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, H.A. Reexamining psychological distress in the current conditions of segregation. Journal of Correctional Health Care 1994, 1, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloud, D.H.; et al. Self-injury and the embodiment of solitary confinement among adult men in Louisiana prisons. SSM-Population Health 2023, 22, 101354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, G.F. Impact of a mental health training course for correctional officers on a special housing unit. Psychiatric Services 2009, 60, 640–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavoie, J.A.; Connolly, D.A.; Roesch, R. Correctional officers’ perceptions of inmates with mental illness: The role of training and burnout syndrome. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health 2006, 5, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haney, C. The psychological effects of solitary confinement: A systematic critique. Crime and Justice 2018, 47, 365–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahalt, C.; et al. Reducing the use and impact of solitary confinement in corrections. International Journal of Prisoner Health 2017, 13, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glowa-Kollisch, S.; et al. From Punishment to Treatment: The “Clinical Alternative to Punitive Segregation” (CAPS) Program in New York City Jails. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2016, 13, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarzar, T.R.; et al. Effect of Clozapine on Time Assigned to Restrictive Housing in a State Prison Population. The Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law 2021, 49, 581–589. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).