1. Introduction

Gestational Diabetes Mellitus (GDM) stands out as a prevalent complication during pregnancy, affecting approximately 14% of pregnant women globally [

1]. This condition manifests when women, not previously identified with diabetes, develop chronic hyperglycemia during their pregnancy. The risks associated with GDM encompass microvascular and macrovascular complications, posing threats to small blood vessels, nerves, as well as macrovascular issues like heart and blood vessel diseases. The interplay of genetics has been established as a contributing factor to diabetes development and its associated risks [

2,

3]. Given its diagnosis during pregnancy, GDM holds the potential to adversely impact both maternal and fetal health [

4].

The American Diabetes Association classifies GDM as first-time diabetes detected during the second or third trimester of pregnancy, its classification under type 1 or type 2 diabetes is not entirely clear [

5]. Risk factors for GDM include overweight or obesity, advanced maternal age, and a family history of diabetes or chronic insulin resistance. Long-term repercussions on the offspring include an elevated risk of obesity, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases [

6,

7,

8].

The diagnosis of GDM escalates the risk of emotional distress, encompassing depression, anxiety, or stress. Furthermore, it negatively influences self-perception of health and quality of life among diagnosed women [

9]. Research indicates a prevalence of depressive symptoms ranging from 25.9% to 56.7%, and anxiety symptoms from 4.8% to 57.7% among women with GDM [

10].

In a study by Lee et al. [

9], it was found that 40% of women with GDM reported experiencing anxiety, while a tenth exhibited symptoms of depression and stress. Fu et al. [

11] observed that up to 60.8% of women with GDM might suffer from anxiety, with some distress attributed to a lack of knowledge about GDM and others to concerns about fetal health [

12]. A Malaysian study reported a prevalence of 12.5% for depression symptoms, 39.9% for anxiety, and 10.6% for stress among women with GDM [

9]. Additionally, mental distress can manifest physically, with somatization acting as a defense mechanism linked to depression and anxiety, where individuals avoid intolerable feelings and fantasies through physical symptoms [

6].A study involving 62 pregnant women (2

nd/3

nd trimester) revealed a correlation between pregnancy and personal disorders like somatization, depression, and anxiety, influenced by sociodemographic characteristics and the pregnancy process itself [

13].

Understanding the emotional and personality aspects and their relation to GDM respectively to the individual's reaction to GDM and GDM diagnosis, is crucial for tailoring effective treatment for each pregnant women diagnosed with GDM.

While existing studies have linked personality traits to clinical measures in diabetic patients, personality traits such as anxiety, depression, stress, and somatization have not been adequately explored among pregnant women diagnosed with GDM in comparison to a control group of healthy pregnant women. Hence, the current study aims are to: (1) investigate differences in anxiety, depression, stress, and somatization levels between pregnant women with and without GDM; (2) assess variations levels of anxiety, depression, stress, and somatization among women with well-controlled diabetes versus poorly controlled diabetes.

Research Hypotheses:

H1: Significant differences will be identified in the levels of anxiety, depression, stress, and somatization between women diagnosed with GDM and healthy pregnant women. It is anticipated that higher levels of anxiety, depression, stress, and somatization will be observed among women with GDM.

H2: Significant differences will be observed in the levels of anxiety, depression, stress, and somatization among women with well-controlled diabetes, based on HbA1c levels, in comparison to women with poorly controlled diabetes. It is expected that higher levels of anxiety, depression, stress, and somatization will be evident among women with uncontrolled blood sugar levels.

2. Methods

This is a quantitative cross-sectional study involving a sample of 103 women who have given birth at least once, comprising 40 women diagnosed with GDM and 63 healthy pregnant women. The research utilized an online questionnaire encompassing three sections: (1) a socio-demographic questionnaire, (2) the DASS-21 questionnaire [

14] evaluating anxiety, depression, and stress, and (3) the BSI (Brief Symptom Inventory) assessing somatization [

15].

2.1. Tools:

Socio-demographic Section: This segment assessed participants' demographic background through inquiries about age, education, ethnicity, number of children at home, births and pregnancies, youngest child's age, economic status, smoking and alcohol habits, physical activity, healthy food habits and family history of diabetes.

DASS-21 Questionnaire (Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale) [

14] was translated into Hebrew by Janine Lurie. This self-report questionnaire gauges the frequency of symptoms in three domains: depression, anxiety, and stress. It consists of 21 items across three scales: depression, anxiety, and stress, each containing 7 items, which were rated by the participants. The questionnaire has shown good psychometric properties, including good internal consistency in both clinical and general populations (Cronbach's alpha: 0.88 for the Depression Scale, 0.82 for the Anxiety Scale, 0.9 for the Stress Scale, and 0.93 for the total score). The questionnaire also has demonstrated good validity and its scores have shown high correlations with other measures of depression and anxiety levels [

14,

16,

17].

The questionnaire is scored by summing the participant's ratings for each scale, based on the item distribution across the different scales.

Anxiety Scale: The items assessed various expressions of anxiety, including somatic anxiety (physical symptoms), situational anxiety (anxiety related to specific situations), and subjective experience of anxiety (personal perception of anxiety). The scale ranged from 0 (never) to 3 (almost always) for each item (items: 2, 4, 7, 9, 15, 19, 20). Higher scores indicated increased levels of anxiety, providing a quantitative measure of anxiety severity across these different dimensions.

Distress Scale: Items measuring various expressions of distress and pressure, both chronic and situational, were found to be related to generalized anxiety symptoms, including emotional arousal, difficulty calming down, a tendency to react with anger, irritability, impatience, and intolerance. The scale range was between 0 (never) to 3 (almost always) (items: 1, 6, 8, 11, 12, 14, 18), and higher scores indicated a higher level of perceived distress (average of all other dependent variables).

Depression Scale: Items assess different expressions of depression including dysphoria, self-image disturbance, lack of hope, anhedonia, and inertia. The scale range was between 0 (never) to 3 (almost always) (items: 3, 5, 10, 13, 16, 17, 21), and higher scores indicating elevated depression levels.

BSI (Brief Symptom Inventory) somatization questionnaire: The items (13) describe various complaints or symptoms, some of which are related to pain such as chest pain, headaches, lower back pain, and others related to unpleasant sensations in the body such as pressure, numbness, swelling, nausea, and dizziness. The scale frequency of symptom experience in the past month [

15] was between 0 (not at all) to 4 (very much). A high score on this questionnaire indicates a high frequency of somatic symptoms. The questionnaire has been translated into Hebrew and has good reliability (α=0.850) and high internal consistency and validity [

18].

2.2. Research Procedure

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Social and Community Sciences at Ruppin Academic Center. Using a snowball sampling method, an online questionnaire was distributed through social networks such as Facebook, targeting various women's groups and forums for mothers and pregnant women. Participants included women diagnosed with GDM and healthy pregnant women, aged between 18-50.

2.3. Data Analysis

IBM SPSS Statistics 28 software was used for statistical analysis. Descriptive statistics were used to outline demographic and research variables. For testing the first research hypothesis, an independent t-test was conducted for anxiety, depression, stress, and somatization. The second hypothesis involved a dichotomous division based on balanced and unbalanced HbA1C levels, with an independent t-test conducted for anxiety, depression, stress, and somatization.

3. Results

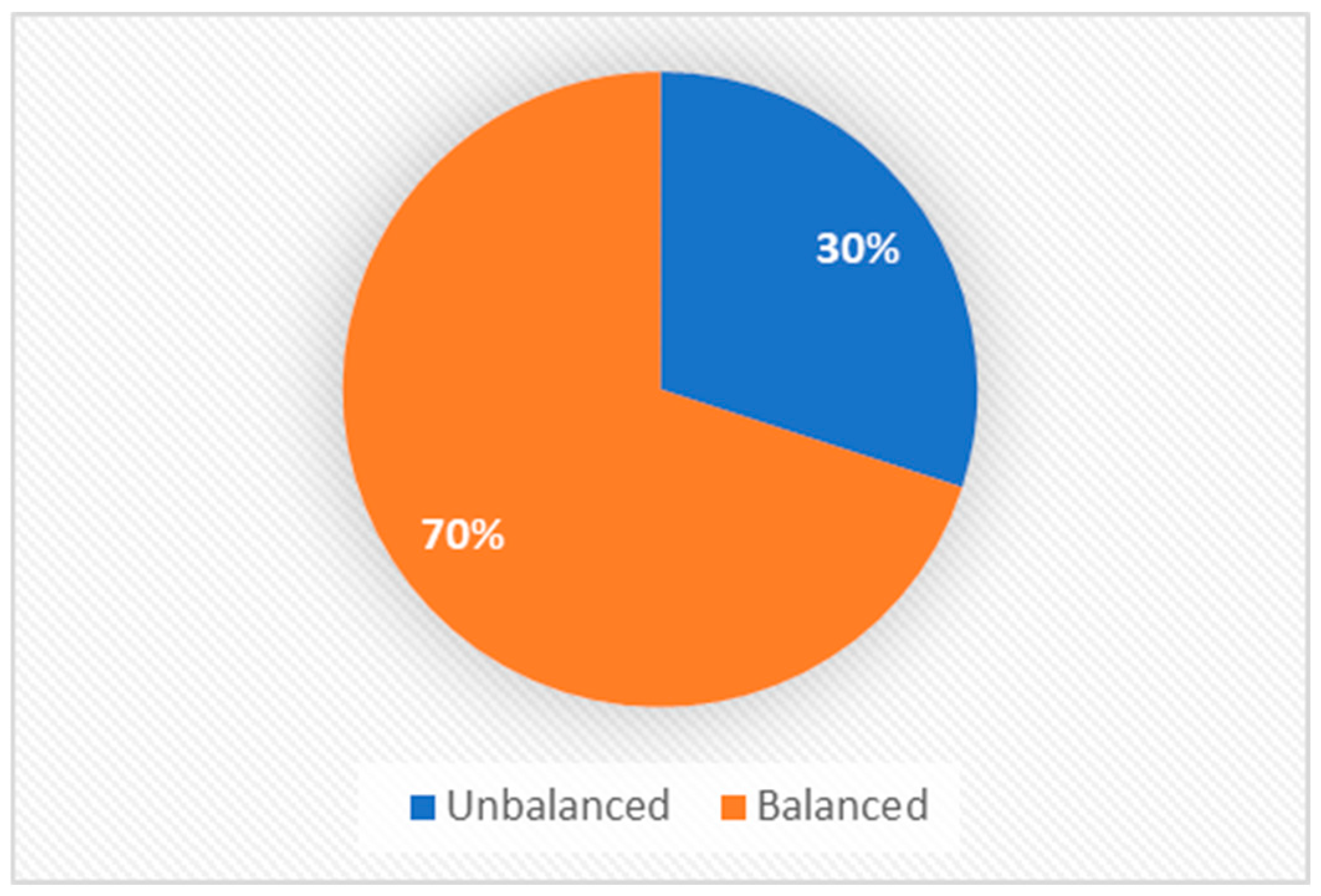

In this quantitative study, a sample of 103 pregnant women (at least once) was analyzed, including 40 diagnosed with GDM and 63 healthy pregnant women. The participants' average age was 34.24. Marital status distribution indicated that 79% were married, 14% were divorced, 3% were single, and 4% defined their status as "other." The youngest child's age ranged from six months to 13 years, with an average age of 3.55. Family size varied, with 38% having one child, 23% having two children, 28% having three children, 7% having four children, 2% having five children, and an additional 2% having six children. Educational backgrounds included 11% with a high school education, 33% beyond high school, 42% with a bachelor's degree, 13% with a master's degree, and 12% holding a doctoral degree. Religious affiliation comprised 77% Jewish, 11% Christian, 9% Muslim, and others identifying as non-religious. Among diabetic patients, 70% considered themselves balanced, and 30% as unbalanced (

Figure 1). Regarding lifestyle, 73% never smoked, 13% smoked occasionally, 9% smoked frequently, 1% smoked very frequently, and 4% smoked regularly. Physical activity engagement showed 8% never engaged, 32% occasional, 19% frequent, 24% very frequent, and 17% always engaged. The latest glycated hemoglobin (HbA1C) values in the blood test ranged from 6.3 to 7.23, with an average of 6.73.

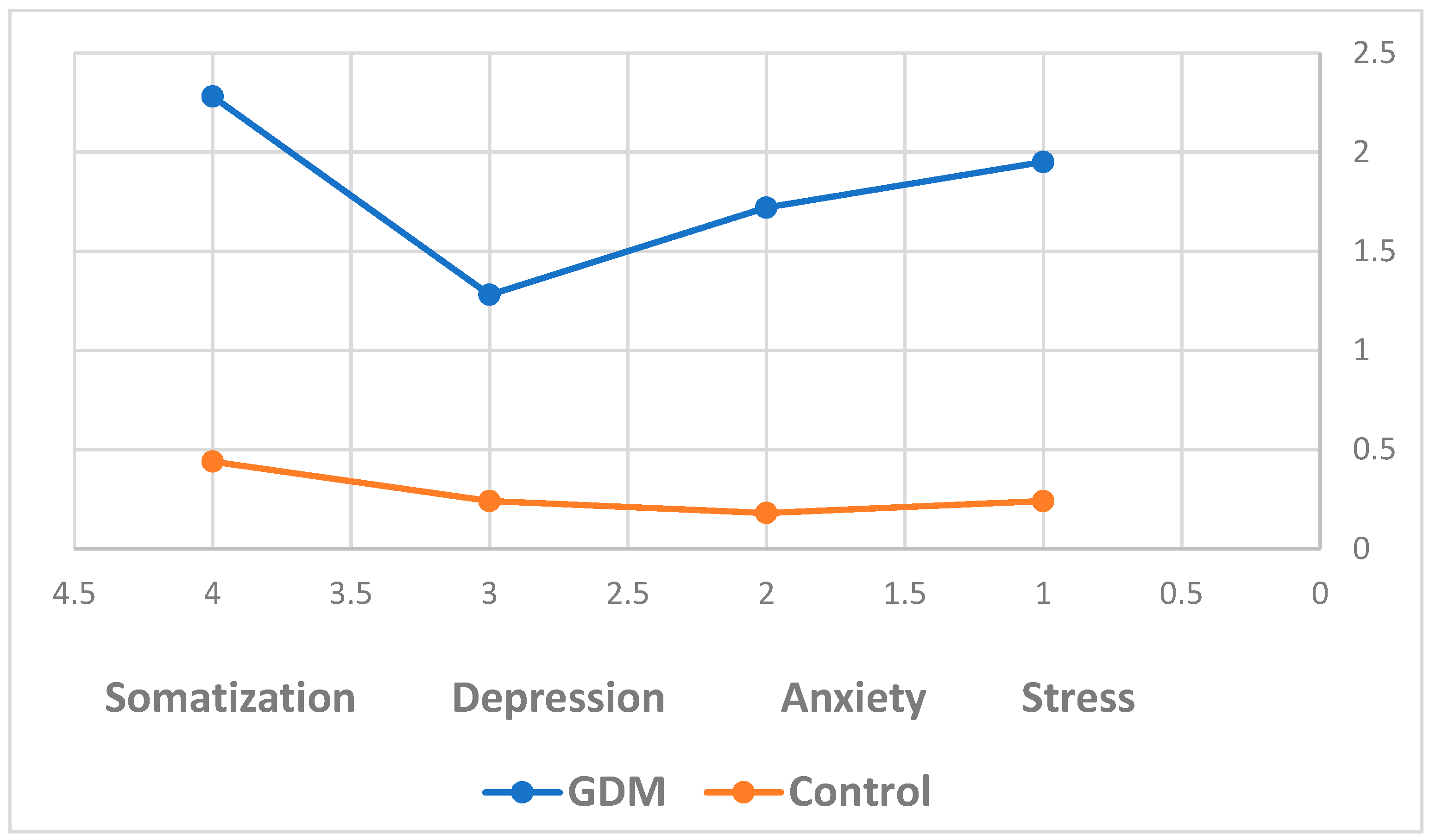

The first research hypothesis was confirmed, revealing significant differences in levels of anxiety (t=14.470, p<.001), depression (t=8.17, p<.001), stress (t=16.354, p<.001), and somatization (t=13.679, p<.001) between women diagnosed with GDM and healthy pregnant control group (

Figure 2).

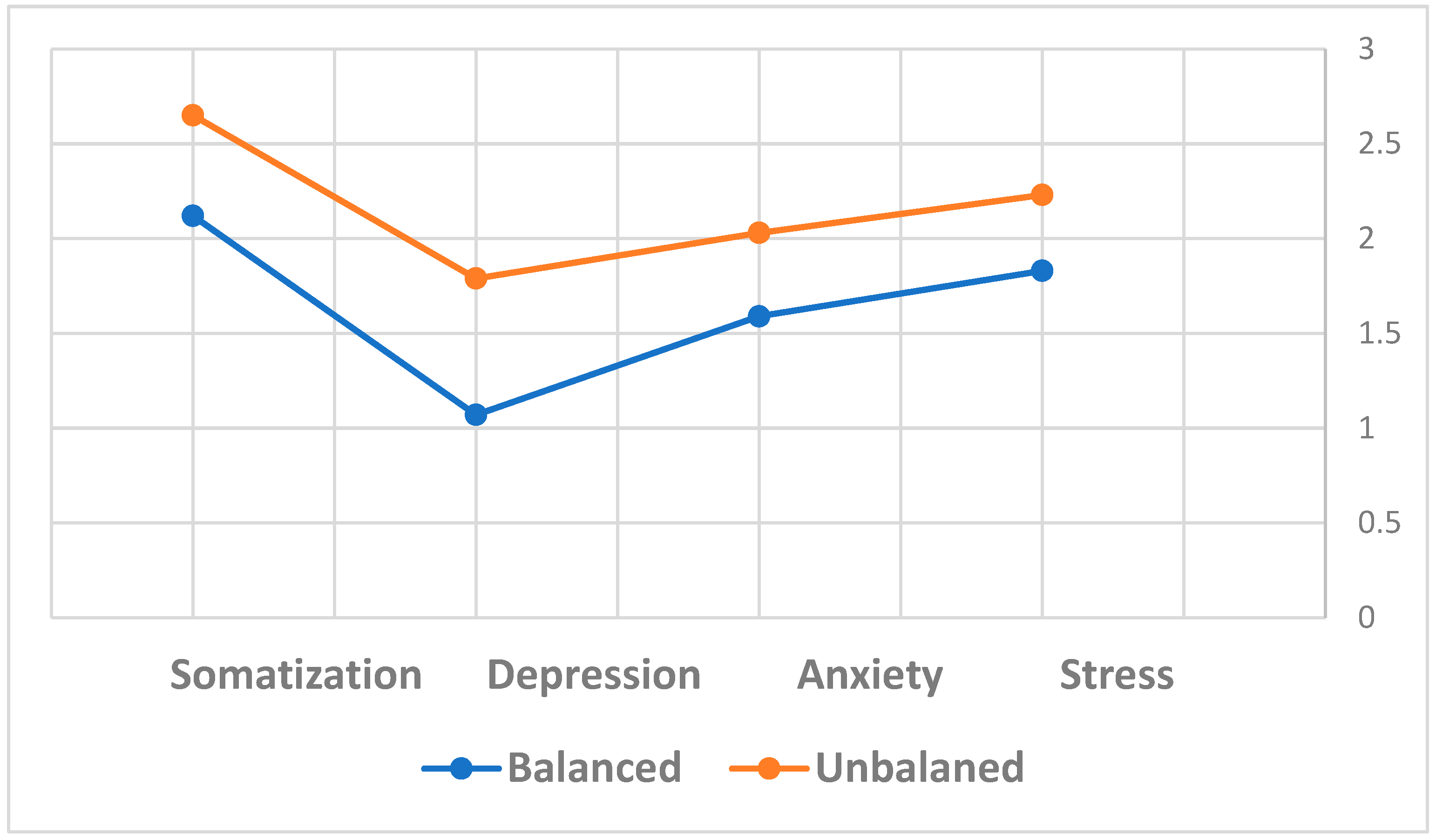

To explore differences in anxiety, depression, stress, and somatization concerning diabetes control, an independent samples t-test demonstrated significant differences in anxiety (t(38)= -2.04, p<0.05), depression (t(38)= -2.88, p<0.01), stress (t(38)= -1.88, p<0.05), and somatization (t(38)= -1.88, p<0.05) between women with well-controlled and poorly controlled diabetes. Higher levels of anxiety, depression, stress, and somatization were observed in women with poorly controlled diabetes.

The second research hypothesis was confirmed, indicating that women with better HbA1C levels exhibited lower levels of anxiety, depression, stress, and somatization compared to those with poorer control. Women diagnosed with GDM were asked to categorize themselves as balanced or unbalanced based on their reported HbA1C levels during pregnancy (

Table 1,

Figure 3). The results from the second hypothesis indicated that balanced women exhibited significantly lower levels of anxiety, depression, stress, and somatization compared to those who were unbalanced (

Table 1,

Figure 3).

In summary, the second hypothesis was confirmed, revealing lower levels of anxiety, depression, stress, and somatization in balanced women compared to those who were not balanced.

4. Discussion

The study delved into variations in levels of anxiety, depression, stress, and somatization among women with GDM compared to healthy pregnant women, and further explored differences based on diabetes control. Both research hypotheses were substantiated shedding light on critical aspects of psychological well-being during pregnancy such as levels of anxiety, depression, stress, and somatization among women diagnosed with GDM compared to healthy pregnant women.

Aligning with the findings of OuYang et al. [

10], the study established that women with GDM exhibit heightened expression of anxiety and depression compared to healthy pregnancies.

Expanding on this comprehension, we aim to investigate notable disparities and heightened levels of somatization among women with GDM in comparison to those without it—a facet, to the best of our knowledge, that has not been previously examined.

The psychological pressure experienced by women with GDM, driven by the awareness of potential complications to both pregnancy and the fetus due to uncontrolled diabetes, might contribute to possible elevated antenatal depression, anxiety, and stress.

Furthermore, it was found that 40% of women who had GDM suffered from anxiety, and a tenth of them suffered from symptoms of depression and stress, those finding aligns with earlier research [

9], emphasizing the importance of addressing psychological well-being in this demographic.

Collier et al.'s insights regarding economic difficulties, healthcare and food costs, as well as physical barriers add a socio-economic dimension to the challenges faced by women with GDM [

19]. These women also experienced difficulties in finding available, valid, and relevant information, as well as in communication with the healthcare system to obtain such information. The perceived time-consuming nature of insulin injections reflects additional psychological burdens. These findings underscore the multifaceted nature of the challenges this population encounters, necessitating holistic intervention strategies [

20].

Accumulating evidence underlines the increasing potential adverse effects of emotional distress during pregnancy on infant development including depression, anxiety, general stress, and specific pregnancy-related stress [

21,

22,

23]. Pregnant women diagnosed with GDM experience heightened psychological pressure caused to the awareness of uncontrolled diabetes who can lead to pregnancy-related complications and harm the fetus. Therefore, this emphasizes the tendency to develop prenatal depression, anxiety, and stress [

11].

The second part of the study reaffirmed that perceived balance in diabetic pregnant women correlates with lower levels of anxiety, depression, stress, and somatization. This suggests that a sense of control over the disease reduces negative emotions, such as, feelings of stress, anxiety, and their negative consequences. Treatment strategies for GDM, including blood glucose management and specialized obstetric care, appear effective in lowering the risk of perinatal complications. The interaction of psychosocial well-being with diet and physical activity highlights the interconnectedness of lifestyle factors and glycemic control. Thus, awareness can very likely reduce health risk including the fetus risks and can lead to decrease levels of anxiety, stress, depression, and somatization.

The study underscores the need for healthcare providers such as balanced diet and regular physical activity to assess psychological well-being and distress at the time of GDM diagnosis and to help controlling their glycemic balance [

24]. It is also possible that the woman's perception of the disease is related to her levels of anxiety, stress, depression, and somatization. For example, mental health has is an important factor in the management of GDM that is still underestimated and should be implemented into daily practice [

25]. Hence, in order to optimize treatment strategies in GDM patients and alleviate the burden of the disease, care providers need to assess the psychological distress of their patients at the time of GDM diagnosis.

The influence of coping resources, both personal and professional, on levels of stress, anxiety, depression, and somatization merits further exploration. Unfortunately, the current study did not assess the woman's knowledge about her condition or her perception of the illness and sense of well-being. However, evaluating women's knowledge about their well-being condition and their perception of illness is crucial for a comprehensive understanding of the emotional experiences associated with GDM and most likely can have a direct relation. In addition, a study by Hjelm et al. [

26] found that beliefs differed and were related to the health-care model chosen. As found, women with GDM (monitored at a specialist maternity clinic) believed that it is a transient condition during pregnancy only, and they expressed fear about a future risk of developing type 2 diabetes.

In summary, the current study provides valuable insights into the personality traits of pregnant women with and without GDM. The findings underscore the importance of addressing psychological well-being, especially in the context of GDM and indicate that pregnant women diagnosed with GDM report higher levels of negative personality traits such as anxiety, depression, stress, and somatization compared to healthy pregnant women. Furthermore, women with GDM diagnosed with balanced levels of HBA1C reported lower levels of anxiety, depression, stress, and somatization compared to women with no balanced sugar levels. Recommendations include holistic interventions, further research on a larger and diverse population, and exploration of factors influencing emotional states in women with GDM.

5. Limitations

The study included a relatively small sample of pregnant women, both with and without GDM. This limited sample size raises concerns about the generalizability of the results to the broader population of pregnant women. The findings might not fully encompass the varied experiences within this demographic, so it's advisable to exercise caution when extrapolating the outcomes.

The study's reliance on self-report questionnaires introduces the potential for participant bias. Responses to questions related to anxiety, depression, stress, and somatization may be influenced by subjective interpretations and individual perspectives. Participants might provide socially desirable responses or may not accurately represent their psychological states, impacting the reliability of the data. In addition, the unequal representation of women with GDM and healthy pregnant women raises concerns about the representativeness of the study cohort. A more balanced sampling approach would have strengthened the study's external validity by ensuring a more equitable comparison group.

The study did not delve into certain crucial factors that could influence emotional states, such as participants' knowledge about their condition, perception of illness, coping mechanisms, and their own sense of well-being. These unexplored variables could significantly contribute to the understanding of the emotional experiences of pregnant women with GDM. In addition, the study primarily focused on anxiety, depression, stress, and somatization, leaving other potential psychological aspects unexplored. Comprehensive psychological assessments encompassing a broader range of variables would offer a more nuanced understanding of the emotional well-being of pregnant women with GDM. The cross-sectional design employed in the study captures a snapshot of participants' experiences at a specific point in time. Longitudinal studies would provide a more dynamic view, allowing for the examination of changes in emotional states over the course of pregnancy, potentially uncovering patterns, or fluctuations.

6. Conclusions

The findings of this study shed light on the psychological challenges faced by pregnant women diagnosed with GDM. The following conclusions can be drawn from the study:

6.1. Heightened Psychological Concerns in GDM Patients:

The study underscores the increased prevalence of psychological issues among pregnant women with GDM. The higher levels of anxiety, depression, stress, and somatization observed in this group emphasize the need for targeted interventions to address their unique mental health needs.

6.2. Call for Active Psychological Interventions:

The study highlights the importance of implementing active and effective psychological intervention measures for GDM pregnant women. Given the psychological pressures associated with GDM, tailored interventions could contribute to better mental health outcomes during pregnancy. Healthcare providers should consider incorporating psychological support into routine care for this population.

6.3. Focus on Pregnancy Safety and Outcomes:

Recognizing the psychological impact on pregnancy outcomes, the study suggests that addressing the mental health of GDM patients is crucial not only for their well-being but also for achieving better pregnancy outcomes. Interventions aimed at reducing anxiety, depression, stress, and somatization may contribute to safer and healthier pregnancies for women with GDM.

6.4. Need for Further Research:

While the study contributes valuable insights into the psychological aspects of GDM, these limitations underscore the need for cautious interpretation. Future research endeavors should address these constraints, employing larger and more diverse samples, incorporating objective measures, and exploring a broader array of contributing factors to enhance the robustness of findings.

Future research should focus on identifying and examining the various factors that influence the levels of anxiety, stress, depression, and somatization among women diagnosed with GDM. Factors such as socio-economic status, cultural considerations, medication treatment and access to healthcare should be explored to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the multifaceted nature of psychological well-being in this population.

In conclusion, addressing the psychological well-being of pregnant women with GDM is a crucial aspect of comprehensive prenatal care. The study emphasizes the imperative for proactive measures to support these women emotionally, ultimately contributing to safer pregnancies and improved outcomes. Ongoing research in this field will further refine our understanding and inform evidence-based interventions for this specific group of pregnant women.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Keren Grinberg and Yael Yisaschar Mekuzas; Methodology, Keren Grinberg and Yael Yisaschar Mekuzas; Formal analysis, Keren Grinberg and Yael Yisaschar Mekuzas; Resources, Yael Yisaschar Mekuzas; Data curation, Keren Grinberg and Yael Yisaschar Mekuzas; Writing – original draft, Keren Grinberg; Writing – review & editing, Keren Grinberg and Yael Yisaschar Mekuzas.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Social and Community Sciences at Ruppin Academic Center (approval code: 185, approval date: 31/10/2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Lea Dovrat for reviewing and editing this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Wendland EM, Torloni MR, Falavigna M, Trujillo J, Dode MA, Campos MA, Duncan BB, Schmidt MI. Gestational diabetes and pregnancy outcomes-a systematic review of the World Health Organization (WHO) and the International Association of Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Groups (IADPSG) diagnostic criteria. BMC pregnancy and childbirth. 2012 Dec;12:1-3. [CrossRef]

- Cole JB, Florez JC. Genetics of diabetes mellitus and diabetes complications. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2020 Jul;16(7):377-390. Epub 2020 May 12. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jung CH, Son JW, Kang S, Kim WJ, Kim HS, Kim HS, Seo M, Shin HJ, Lee SS, Jeong SJ, Cho Y, Han SJ, Jang HM, Rho M, Lee S, Koo M, Yoo B, Moon JW, Lee HY, Yun JS, Kim SY, Kim SR, Jeong IK, Mok JO, Yoon KH. Diabetes Fact Sheets in Korea, 2020: An Appraisal of Current Status. Diabetes Metab J. 2021 Jan;45(1):1-10. Epub 2021 Jan 13. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Murray-Davis B, Berger H, Melamed N, Darling EK, Syed M, Guarna G, Li J, Barrett J, Ray JG, Geary M, Mawjee K. A framework for understanding how midwives perceive and provide care management for pregnancies complicated by gestational diabetes or hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Midwifery. 2022 Dec 1;115:103498. [CrossRef]

- Plows JF, Stanley JL, Baker PN, Reynolds CM, Vickers MH. The pathophysiology of gestational diabetes mellitus. International journal of molecular sciences. 2018 Oct 26;19(11):3342. [CrossRef]

- Nathan DM. Diabetes: advances in diagnosis and treatment. Jama. 2015 Sep 8;314(10):1052-62. [CrossRef]

- Natamba BK, Namara AA, Nyirenda MJ. Burden, risk factors and maternal and offspring outcomes of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA): a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC pregnancy and childbirth. 2019 Dec;19:1-1. [CrossRef]

- McGrath M. The Relationship Between Gestational Diabetes and Stress: A Literature Review. 2021.

- Lee KW, Ching SM, Hoo FK, Ramachandran V, Chong SC, Tusimin M, Mohd Nordin N. Prevalence and factors associated with depressive, anxiety and stress symptoms among women with gestational diabetes mellitus in tertiary care centres in Malaysia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019 Oct 21;19(1):367. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- OuYang H, Chen B, Abdulrahman AM, Li L, Wu N. Associations between gestational diabetes and anxiety or depression: a systematic review. Journal of diabetes research. 2021 Jul 28;2021. [CrossRef]

- Fu F, Yan P, You S, Mao X, Qiao T, Fu L, Wang Y, Dai Y, Maimaiti P. The pregnancy-related anxiety characteristics in women with gestational diabetes mellitus: why should we care? BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021 Jun 10;21(1):424. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Marquesim NA, Cavassini AC, Morceli G, Magalhães CG, Rudge MV, Calderon Ide M, Kron MR, Lima SA. Depression and anxiety in pregnant women with diabetes or mild hyperglycemia. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2016 Apr;293(4):833-7. Epub 2015 Sep 25. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scharlau F, Pietzner D, Vogel M, Gaudl A, Ceglarek U, Thiery J, Kratzsch J, Hiemisch A, Kiess W. Evaluation of hair cortisol and cortisone change during pregnancy and the association with self-reported depression, somatization, and stress symptoms. Stress. 2018 Jan 2;21(1):43-50. [CrossRef]

- Lovibond PF, Lovibond SH. The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behaviour research and therapy. 1995 Mar 1;33(3):335-43. [CrossRef]

- Derogatis LR, Melisaratos N. The brief symptom inventory: an introductory report. Psychological medicine. 1983 Aug;13(3):595-605. [CrossRef]

- Henry JD, Crawford JR. The short-form version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21): Construct validity and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. British journal of clinical psychology. 2005 Jun;44(2):227-39. [CrossRef]

- Lovibond PF. Long-term stability of depression, anxiety, and stress syndromes. Journal of abnormal psychology. 1998 Aug;107(3):520. [CrossRef]

- Canetti L, Shalev AY, De-Nour AK. Israeli adolescents' norms of the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI). The Israel Journal of Psychiatry and Related Sciences. 1994 Jan 1;31(1):13-8. [PubMed]

- Collier SA, Mulholland C, Williams J, Mersereau P, Turay K, Prue C. A qualitative study of perceived barriers to management of diabetes among women with a history of diabetes during pregnancy. Journal of Women's Health. 2011 Sep 1;20(9):1333-9. [CrossRef]

- Collier JL, Abrahams JF. A review of mHealth interventions for diabetes in pregnancy. Global Health Innovation. 2019 Nov 26;2(2). [CrossRef]

- Bowers K, Ding L, Gregory S, Yolton K, Ji H, Meyer J, Ammerman RT, Van Ginkel J, Folger A. Maternal distress and hair cortisol in pregnancy among women with elevated adverse childhood experiences. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2018 Sep;95:145-148. Epub 2018 May 18. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riggin L. Association between gestational diabetes and mental illness. Canadian journal of diabetes. 2020 Aug 1;44(6):566-71. [CrossRef]

- Robinson DJ, Coons M, Haensel H, Vallis M, Yale JF, Diabetes Canada Clinical Practice Guidelines Expert Committee. Diabetes and mental health. Canadian journal of diabetes. 2018 Apr 1;42:S130-41. [CrossRef]

- Gilbert L, Gross J, Lanzi S, Quansah DY, Puder J, Horsch A. How diet, physical activity and psychosocial well-being interact in women with gestational diabetes mellitus: an integrative review. BMC pregnancy and childbirth. 2019 Dec;19:1-6. [CrossRef]

- Rieß C, Heimann Y, Schleußner E, Groten T, Weschenfelder F. Disease Perception and Mental Health in Pregnancies with Gestational Diabetes—PsychDiab Pilot Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023 May 9;12(10):3358. [CrossRef]

- Hjelm K, Berntorp K, Frid A, Åberg A, Apelqvist J. Beliefs about health and illness in women managed for gestational diabetes in two organisations. Midwifery. 2008 Jun 1;24(2):168-82. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).