1. Introduction

Apart from the excellent academic achievement expected from medical students, medical students’ psychological, social, and physical well-being and academic motivation are also ongoing concerns for any medical school. Students’ subjective well-being and motivation are important aspects of their academic lives as they are also correlated with their academic performance [

1,

2].

There are two types of motivation. First, intrinsic motivation reflects genuine interest in an activity to learn and assimilate. Second, extrinsic motivation is derived from an expected gain or outcome. It includes external and internal reward or punishment, self-control, personal importance, and value. Amotivation typically describes a lack of motivation [

3,

4]. A study found that academic motivation has indirect effects on academic performance through learning engagement [

2]. However, a study revealed that medical students’ motivation decreased as medical training progressed. Factors associated with motivation include learning environment, learning approach, time spent studying, time of studying, sex, stressors, sleep quality, bullying or discrimination during training, perceived social support, and determination. While depression is associated with amotivation [

3,

5,

6,

7,

8].

A systematic review of data across countries, including Thailand revealed high prevalence of depression, anxiety, stress, and suicidal ideation among medical students. Medical students experience higher depressive symptoms, stress and anxiety levels compared to general young adults. Related research has shown that they also had higher suicidal ideation, higher rate of burnout and a poorer quality of life [

9,

10,

11]. These mental health problems affect students’ personal shame and doubt, relationship problems, substance misuse, and suicide. Other consequences include cynicism, reduced empathy, professionalism and efficacy [

12].

A study found that the prevalence of these mental problems was highest among fourth-year medical students [

13]. Compared to preclinical studying (first to third year in Thailand), clinical training (fourth to sixth year in Thailand) for medical students can be very stressful. Changing from pre-clinical to clinical years is one of the major stressors giving rise to anxiety for medical students [

11]. This could be due to the fact that studying in the clinical years can expose students to many stressful events. Study in the clinical year also inevitably involves difficult encounters with numerous people, including patients, residents, senior faculty, and other healthcare personnel [

10,

14]. Students who have academic stress and relationship problems have a higher risk of depression and anxiety [

15,

16].

While it is essential for students to attain competence as physicians, medical training is characterized by exceedingly high expectations. Some individuals involved in the process may mistakenly believe that subjecting students to demanding and occasionally intimidating experiences is the optimal method to prepare them for the rigors of clinical practice, inadvertently contributing to the potential for mistreatment.

Mistreatment is defined as “either intentional or unintentional acts occurring when behavior shows disrespect for the dignity of others and unreasonably interferes with the learning process.” Mistreatment includes the use of grading and other forms of assessment in a punitive manner; discrimination or harassment based on race, religion, ethnicity, sex, or sexual orientation; humiliation; psychological or physical punishment; and sexual harassment [

17].

Even though mistreatment is less likely to be expected in a highly structured environment such as a medical school, there is a high prevalence of this problem. Mistreatment has been reported among 35-47 % of students across medical schools [

17,

18,

19]. The most common form of mistreatment was public humiliation, sexist names, requests to perform personal services, and lower evaluations or grades because of gender from clinical professors [

17]. Previous studies in Thailand found that 63.4-74.5% of medical students experienced mistreatment during training. The most common types of mistreatment reported from Thai medical students were verbal criticism and discriminative behavior from the attending physician [

6,

20].

Being mistreated can considerably affect students’ academic performance as well as their well-being. Some students respond to mistreatment with stress, burnout, anxiety, depression, and decreased motivation to continue studying [

6,

20,

21]. Experiencing recurrent and severe mistreatment is associated with students’ feeling overwhelmed and thinking about quitting medical school [

22].

Although mistreatment remains a challenging issue in medical education, problems could be prevented with appropriate communication and a clear understanding between medical personnel and students [

17,

23]. Interventions to reduce mistreatment by a collaboration of students, faculty members, and administrative leaders have been reported. The interventions included identifying misunderstandings, challenges and impact of mistreatment, promoting professionalism in faculty members, prompt response to report of mistreatment and providing tool to help instructor provide authentic learning environments for students. These interventions shown reduction of mistreatment reported [

23].

In Thailand, there are still very few reports and studies on mistreatment among medical students [

6,

20]. The prevalence and associated factors of mistreatment among Thai medical students are unclear. The hypothesis is that there could be some prevalence of mistreatment among Thai medical students and mistreatment could be associated with students’ low academic motivation. This study aims to investigate the prevalence of mistreatment and its association with academic motivation among Thai medical students in their clinical years. The hypothesis is that there could be some prevalence of mistreatment among Thai medical students and mistreatment could be associated to students’ low academic motivation. Additionally, the study aims to examine the existing support systems and procedures for reporting mistreatment within medical schools.

2. Materials and Methods

This research is part of the project “Mental strength and challenges among Thai medical Students in their clinical year”.

2.1. Study Design and Time-Period

This study employed a cross-sectional design among medical students currently studying and working in 23 qualified medical schools throughout Thailand (2020-2021). The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University. Study code: FAC-MED-2563-07564 / Research ID: FAC-MED-2563-07564

2.2. Study Population

The participants were medical students currently studying in their clinical years, years 4 to 6 within 23 certified Thai medical schools by Institute of medical education accreditation (IMEAc). Inclusion criteria include students having 1. an electronic device with an internet connection, such as a mobile phone, tablet, or personal computer, to submit questionnaires and 2. Having passed at least one rotation in clinical training. There are no exclusion criteria for participants.

2.3. Sample Size Calculation

A related study conducted at a Thai medical school in the southern region indicated that the proportion of medical students experiencing mistreatment at least once during their clinical years totaled 63.4% [

20]. With an absolute error of 5% (d = 0.05) and a type I error at 5% (Z = 1.96) [

24], we calculated the number of required participants; these calculations indicated we needed to recruit at least 357 participants for this study. However, as many participants were interested in participating in the online survey that the researchers were unable to close the link when the target number of participants was reached. The final number of participants is 399.

2.4. Procedure and Participant Invitation

Because of COVID-19 pandemic requirements for physical distancing, we developed an online questionnaire for this study. The investigator team provided the relevant link, or the Quick Response code (QR code) to all potential participants. Flyers to invite students to participate in the study were placed in private areas such as medical students’ dormitories or private rooms for medical students in teaching hospitals. Social media networks such as LINE and medical student associations were used to communicate and distribute the questionnaires. A convenience and snowball sampling strategy was applied to recruit potential participants. Payments of 200 baths (5.7 US Dollars at the exchange in October 2023) were offered to compensate for completing the questionnaires.

The Data were collected for one year. Information regarding informed consent and details about the study was included on the first page of the questionnaire before participants answered questions to ensure that they understood and willingly participated in the study. Personal details that could be used to identify respondents were excluded from the report.

2.5. Measurements

The primary questionnaires included sociodemographic data, information related to participants’ status, and information related to support and extracurricular activities provided by the faculty, followed by questionnaires assessing academic motivation by The Academic Motivation Scale (AMS).

The AMS measures 3 types of motivation based on the self-determination theory, i.e., intrinsic, extrinsic, and amotivation. It is developed by Vallerand et al. [

25], and adapted for use among medical students by Kusurkar et al. [

4]. The Thai version was developed by Wongpakaran and was used with permission. The AMS has 28 items that use a 7-point Likert scale that ranges between 1 “strongly disagree” to 7 “strongly disagree”. There are three subscales of intrinsic motivation: 1. obtaining knowledge, 2. accomplishment, and 3. stimulation. Extrinsic motivation also has three subscales: 1. identified regulation, 2. introjected regulation, and 3. external regulation. The score ranging from 28 to 196, the higher score the higher academic motivation. The internal consistency of the Thai version of AMS was excellent (Cronbach α = 0.84) [

3].

Lastly, mistreatment questionnaires investigated the participants’ experiences of or witnessing an episode of mistreatment and their reaction to mistreatment experienced by a single question.

The questionnaire regarding mistreatment experience was developed by collecting questions and information reported in previous studies via PubMed and Google Scholar search. The text words “medical student”, “mistreatment”, “clinical training”, “abuse” and “harassment” were used for articles published from 2006 to June 2020. Previous studies about medical students’ mistreatment during clinical training were reviewed [

20,

21,

22,

26,

27,

28]. Several current medical students and faculty were also interviewed to develop this questionnaire. The questionnaire consists of 38 questions to inquire about detailed information regarding mistreatment experience and reporting of mistreatment incidence. T questionnaire regarding mistreatment prevalence is based on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from never (0 times), a couple of times (1 to 2 times), sometimes (3 to 5 times), often (6 to 10 times) and many times (over 10 times). This questionnaire has face validity assessed by Professor Tinakon Wongpakaran and Professor Nahathai Wongpakaran, professors of psychiatry. The questionnaire was tested in a pilot study with 30 medical students. The content validity index is 1.00.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used for sociodemographic data presented as frequency; percentage (%) was used for categorical variables, e.g., sex, while continuous variables, e.g., age will be presented as mean ± standard deviation or median (IQR). To assess differences between groups, chi-square was used. Correlation and regression were used to examine associations between anticipated outcomes and predictors. p-values < 0.05 was considered significant correlations. IMB SPSS, version 22.0, was used for data cleaning and statistical analysis. Multiple imputations were used for missing data or incomplete responses.

Measurement tools of the survey

| Instrument |

Aim in assessing |

Response format |

Number of items |

Recall

period |

Internal consistency |

| Composite Questionnaire of Mistreatment |

Qualitative and quantitative data of mistreatment experience and mistreatment detail (Participants can select more than one choice)

5 Types of mistreatments include

1. Verbal mistreatment

2. Physical mistreatment

3. Sexual mistreatment

4. Discriminative mistreatment

5. Academic mistreatment |

Mixed |

13 |

Past to present |

1.00 (CVI) |

| Academic Motivation Scale (AMS) |

Level of motivation and amotivation

3 types of motivation

i.e., Motivation (intrinsic, extrinsic) and amotivation

Interpretation of the total score: 196 |

7 |

28 |

Past to present |

0.84 (CVI) |

| * Internal consistency is calculated using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient (>0.7 considered acceptable); CVI = content validity index (>0.8 considered acceptable). |

3. Results

3.1. Demographic

A total of 399 Participants completed the questionnaire. Their age was between 21 and 30 years old with a mean age of 23 ± 1.29 years old, and 61.5% were female. The majority of students (39%) was in their 4th year. 15.3% of participant reported an underlying psychiatric disorder (e.g., anxiety disorder, depression and obsessive-compulsive disorder). Out of the 399 participants, 323 (80.95%) reported experiencing mistreatment. Further details are presented in

Table 1.

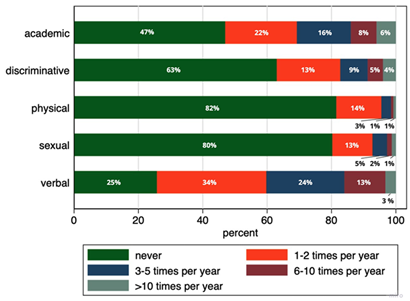

3.2. Prevalence of Mistreatment

Among all, 81% of students were mistreated at least once during their clinical training, while 81.8% of students witnessed mistreatment occurring to their peers. The prevalence of mistreatment was related to the students’ age, year and rotation that they had passed previously in their clinical years. The most common types of mistreatments were verbal mistreatment (74%) followed by academic mistreatment (53%). Thirty-seven percent of students reported experiencing discriminative mistreatment, while 20% and 19% reported experiencing sexual and physical mistreatment respectively (

Table 2).

The most common sources of mistreatment were from faculty members (41%), residents (25%) and nurses (24%). Mistreatment events occurred more frequently at surgery (64.5%), internal medicine (21.7%) and obstetrics and gynecology rotation (11%), respectively (

Table 3). The number of wards passed was not associated with being mistreated (p = 0.120)

The most common reactions to mistreatment among the students were anger (23.2%) and being less motivated to learn (20.6%). 9% of students even thought about quitting their training. The majority of students who experienced or witnessed mistreatment (85.8% and 88.6%) did not report these events. Most students who experienced mistreatment directly thought that the problem couldn’t be solved (48.1%) or that it wasn’t significant enough to be reported (21.3%). Most students who witnessed mistreatment similarly thought this problem can’t be solved (15.7%). Some reported that they didn’t know what to do to help their peers.

When asked about their opinions on the maltreaters’ reason(s) for mistreatment, most students reported that they thought the maltreaters did not consider mistreatment an inappropriate or serious act (28.8%). Some thought the maltreaters wanted students to improve themselves (19.3%) or that they just lost self-control (18.5%) (

Table 3).

3.3. Medical School Support System for Students

Most participants reported that their medical schools provide some supporting system for medical students such as screening for new students or faculty’s mental health each year into a group with previous underlying psychiatric problem and a high-risk group every year. However, most participant reported that mental health support in their school is only moderately sufficient. Most students also reported that their schools also provide financial support and praise the success of students or faculty. In the participants’ opinion, the tradition and hierarchy in their medical institute is highly steeped.

Regarding a mistreatment reporting system in their medical school, most participants report that the efficacy and safety of the system is moderate. Most system does not provide a clear declaration of authorities who can access the report and resolution of the reported problems (

Supplementary Table S1).

3.4. Mistreatment and Students’ Academic Motivation

Students who experienced mistreatment exhibited lower academic motivation scores (B = -9.81, 95% CI: -15.51 to -4.10, p-value = 0.01) than those who did not. While students who experienced academic mistreatment exhibited higher amotivation score (B= 1.66, 95% CI: 0.34 to 2.99, p-value = 0.014) than those who did not. More details are presented in

Table 4.

4. Discussion

This study found that the majority of Thai medical students experienced mistreatment at least once during their clinical training. The prevalence found is higher than in other studies conducted in southern Thailand and other countries [

17,

20,

21,

22]. However, to ensure the anonymity and safety of both students and their medical institutions in this study, the results do not disclose the particular medical schools or the specific regions within Thailand where the prevalence was observed. The societal, cultural factors, students’ perceptions of mistreatment definition as well as the different research tools could involve the prevalence of mistreatment [

6,

17,

29]. One distinction is that, unlike country such as USA, medical education in Thailand usually commences immediately after students graduate from high school. Consequently, the average age of Thai medical students upon admission is 18 years old [

30,

31]. During the first three years, Thai medical students learn fundamental medical knowledge. It is not until their clinical years that they are exposed to patient interactions and begin to develop physician skills.

The difference in prevalence could also be due to the fact that mistreatment is often underreported. This study found a similar result to previous reports that most students chose not to report mistreatment events as they felt that the reporting systems were ineffective and unsafe [

10]. While the majority of participants reported that their medical schools offer some form of mental health support for medical students overall, the reporting system within their institutions lacks clarity regarding the designated authorities authorized to access reports and oversee the resolution of reported issues.

This study also found that mistreatment was related to the students’ age, year and rotation that they had passed previously in their clinical years. As students progressed through their years of study, they reported experiencing more mistreatment. This is similar to the result found by Naothavorn, that mistreatment was related with the academic years [

6]. This trend may be attributed to the increased exposure to potential perpetrators of mistreatment during clinical training as students advance in their education.

Consistent with previous studies, mistreatment by faculty members is the highest, followed by residents and nurses [

6,

17,

20,

26]. This could be due to frequent interactions between students, faculty members and residents that involved intense clinical training. This highlights the need to focus on relationships and interaction between faculty members, residents, and students during training.

A previous study which explore students’ opinion about the mistreatment event among faculty and revealed that most student believed personal character of the maltreaters was the cause of mistreatment [

6]. However, this study found that most students thought that a maltreater might not be aware of mistreatment or did not consider mistreatment an inappropriate or serious act. Previous studies also raised the point that defining mistreatment is a challenging issue as it could be different among cultures or generations [

17]. Establishing appropriate communication and a clear understanding between medical personnel and students of what is inappropriate or considered mistreatment could be the first step to preventing mistreatment and its consequences.

Although, the self-reported underlying of psychiatric disorder did not show a significant association with mistreatment. Mistreatment led to students’ negative feelings such as anger (23.2%) and being less motivated to learn (20.6%). 9% of students even thought about quitting their training. There is an association between mistreatment and low academic motivation. This is consistent with previous studies conducted in other countries about the negative effects of mistreatment [

6,

20,

21,

22,

26]. The stressful and unsafe learning environment caused by mistreatment during training could be the reason for the low academic motivation of students. A study found that several factors related to the school environment, such as the situation in class, the teaching method and the student-teacher relationship, could affect the academic motivation [

8]. This highlights the fact that mistreatment is a serious problem that needs to be made more aware of in the medical education system.

This study has some limitations. First, this study employs a cross-sectional design, which precludes any examination of causal relationships. However, this initial study will set the stage for further and deeper studies in the future. Second, a convenience and snowball sampling strategy were applied to recruit potential participants. As the identities of students and their medical institutes must be protected for their anonymity and safety, a stratification strategy to ensure equal allocation of participants from each part of Thailand or each medical school was not performed. However, as the number of participants exceeded the minimal number of required participants for the cross-sectional study, this group of participants can be expected to represent Thai medical students’ overall population.

5. Conclusions

This study found an unexpectedly high prevalence of mistreatment among Thai medical students during their clinical years, with verbal mistreatment by faculty members being the most common type. Most students thought that mistreatment occurred because the maltreaters did not consider mistreatment an inappropriate or serious act. Mistreatment was associated with a lower level of academic motivation. Unfortunately, most mistreatment events are not reported. Educational institutions should prioritize addressing this issue and develop strategies to provide assistance, including the enhancement of reporting systems.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org, Table S1: A support system.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.H., T.W., N.W., P.S., S.S., J.J, S.K., P.C., A.D. and D.W.; Methodology, T.H., T.W., N.W., P.S., S.S., J.J, S.K., P.C., A.D. and D.W.; Software, T.H., T.W., N.W., P.S. and S.S.; Validation, T.H., T.W., N.W., P.S. and S.S.; Formal Analysis, T.H., T.W., N.W., P.S. and S.S.; Investigation, T.H., T.W., N.W., P.S., S.S., J.J, S.K. and P.C.; Resources, T.H., T.W., N.W., P.S., S.S., J.J, S.K. and P.C.; Data Curation, T.H., T.W., N.W., P.S. and S.S.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, T.H., T.W., N.W., P.S., S.S. and D.W.; Writing—Review & Editing, T.H., T.W., N.W., P.S., S.S. and D.W.; Visualization, T.H., T.W., N.W., P.S.; Supervision, T.W. and N.W.; Project Administration, P.K.; Funding Acquisition, T.H., T.W., N.W., P.S., S.S., J.J, S.K., P.C. and P.K.

Funding

This research was funded by Faculty of medicine, Chiang Mai University, grant number 010/2565 and the APC was funded by Faculty of medicine, Chiang Mai University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University (protocol code FAC-MED-2563-07564 / Research ID: FAC-MED-2563-07564, approved on October 30th 2020)

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Chattu, V. K., Sahu, P. K., Seedial, N., Seecharan, G., Seepersad, A., Seunarine, M., Sieunarine, S., Seymour, K., Simboo, S., & Singh, A. (2020). Subjective Well-Being and Its Relation to Academic Performance among Students in Medicine, Dentistry, and Other Health Professions. Education Sciences, 10(9), Article 9. [CrossRef]

- Wu, H., Li, S., Zheng, J., & Guo, J. (n.d.). Medical students’ motivation and academic performance: The mediating roles of self-efficacy and learning engagement. Medical Education Online, 25(1), 1742964. [CrossRef]

- Kunanitthaworn, N., Wongpakaran, T., Wongpakaran, N., Paiboonsithiwong, S., Songtrijuck, N., Kuntawong, P., & Wedding, D. (2018). Factors associated with motivation in medical education: A path analysis. BMC Medical Education, 18(1), 140. [CrossRef]

- Kusurkar, R. A., Ten Cate, Th. J., Vos, C. M. P., Westers, P., & Croiset, G. (2013). How motivation affects academic performance: A structural equation modelling analysis. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 18(1), 57–69. [CrossRef]

- Da Silva Ezequiel, O., Lucchetti, A. L. G., Melo, P. F., Dias, M. G., e Silva, D. F. L., Lameira, T. L., Ardisson, G. M. C., de Almeida, B. T., & Lucchetti, G. (2022). Factors Associated with Motivation in Medical Students: A 30-Month Longitudinal Study. Medical Science Educator, 32(6), 1375–1385. [CrossRef]

- Naothavorn, W., Puranitee, P., Kaewpila, W., Sumrithe, S., Heeneman, S., Mook, W. N. K. A. van, & Busari, J. O. (2023). An exploratory university-based cross-sectional study of the prevalence and reporting of mistreatment and student-related factors among Thai medical students. BMC Medical Education, 23. [CrossRef]

- Alfaro, E. C., Umaña-Taylor, A. J., Gonzales-Backen, M. A., Bámaca, M. Y., & Zeiders, K. H. (2009). Latino adolescents’ academic success: The role of discrimination, academic motivation, and gender. Journal of Adolescence, 32(4), 941–962. [CrossRef]

- Cadête Filho, A. D. A., Peixoto, J. M., & Moura, E. P. (2021). Medical students’ academic motivation: An analysis from the perspective of the Theory of Self-Determination. Revista Brasileira de Educação Médica, 45(2), e086. [CrossRef]

- Heinen, I., Bullinger, M., & Kocalevent, R.-D. (2017). Perceived stress in first year medical students—Associations with personal resources and emotional distress. BMC Medical Education, 17(1), 4. [CrossRef]

- Benbassat, J. (2014). Changes in wellbeing and professional values among medical undergraduate students: A narrative review of the literature. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 19(4), 597–610. [CrossRef]

- Nuallaong, W. (2010). Stress in medical students of Thammasat University. TMJ, 10(2), Article 2.

- Dyrbye, L. N., Thomas, M. R., & Shanafelt, T. D. (2005). Medical Student Distress: Causes, Consequences, and Proposed Solutions. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 80(12), 1613–1622. [CrossRef]

- EBSCOhost | 138971116 | Prevalence and Associated Factors of Depression in Medical Students at Faculty of Medicine Vajira Hospital. (n.d.). Available online: https://web.p.ebscohost.com/abstract?direct=true&profile=ehost&scope=site&authtype=crawler&jrnl=01252208&AN=138971116&h=x7up5yqicfcgF%2bQOK3rJz7Yxj3SFm0%2fJHPin1izGMeuQ8tqrdSl4l%2fkgQqBzcuYP180wEGBfasBCebJvPD2NWQ%3d%3d&crl=c&resultNs=AdminWebAuth&resultLocal=ErrCrlNotAuth&crlhashurl=login.aspx%3fdirect%3dtrue%26profile%3dehost%26scope%3dsite%26authtype%3dcrawler%26jrnl%3d01252208%26AN%3d138971116 (accessed on 3 July 2023).

- Houpy, J. C., Lee, W. W., Woodruff, J. N., & Pincavage, A. T. (2017). Medical student resilience and stressful clinical events during clinical training. Medical Education Online, 22(1), 1320187. [CrossRef]

- Peng, P., Hao, Y., Liu, Y., Chen, S., Wang, Y., Yang, Q., Wang, X., Li, M., Wang, Y., He, L., Wang, Q., Ma, Y., He, H., Zhou, Y., Wu, Q., & Liu, T. (2023). The prevalence and risk factors of mental problems in medical students during COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 321, 167–181. [CrossRef]

- Shao, R., He, P., Ling, B., Tan, L., Xu, L., Hou, Y., Kong, L., & Yang, Y. (2020). Prevalence of depression and anxiety and correlations between depression, anxiety, family functioning, social support and coping styles among Chinese medical students. BMC Psychology, 8(1), 38. [CrossRef]

- Mavis, B., Sousa, A., Lipscomb, W., & Rappley, M. D. (2014). Learning About Medical Student Mistreatment From Responses to the Medical School Graduation Questionnaire. Academic Medicine, 89(5), 705. [CrossRef]

- Teshome, B. G., Desai, M. M., Gross, C. P., Hill, K. A., Li, F., Samuels, E. A., Wong, A. H., Xu, Y., & Boatright, D. H. (2022). Marginalized identities, mistreatment, discrimination, and burnout among US medical students: Cross sectional survey and retrospective cohort study. The BMJ, 376, e065984. [CrossRef]

- Hill, K. A., Samuels, E. A., Gross, C. P., Desai, M. M., Sitkin Zelin, N., Latimore, D., Huot, S. J., Cramer, L. D., Wong, A. H., & Boatright, D. (2020). Assessment of the Prevalence of Medical Student Mistreatment by Sex, Race/Ethnicity, and Sexual Orientation. JAMA Internal Medicine, 180(5), 653–665. [CrossRef]

- Pitanupong, J. (2019). The Prevalence and Factors Associated with Mistreatment Perception among Thai Medical Students in a Southern Medical School. Siriraj Medical Journal, 71, 310–317. [CrossRef]

-

Medical student abuse during clinical clerkships in Japan | SpringerLink. (n.d.). Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00320.x (accessed on 4 July 2023).

- Peres, M. F. T., Babler, F., Arakaki, J. N. L., Quaresma, I. Y. do V., Barreto, A. D. A. de L., Silva, A. T. C. da, & Eluf-Neto, J. (2016). Mistreatment in an academic setting and medical students’ perceptions about their course in São Paulo, Brazil: A cross-sectional study. Sao Paulo Medical Journal, 134, 130–137. [CrossRef]

- Lind, K. T., Osborne, C. M., Badesch, B., Blood, A., & Lowenstein, S. R. (2020). Ending student mistreatment: Early successes and continuing challenges. Medical Education Online, 25(1), 1690846. [CrossRef]

- How to Calculate Sample Size for Different Study Designs in Medical Research? - Jaykaran Charan, Tamoghna Biswas, 2013. (n.d.). Available online: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.4103/0253-7176.116232 (accessed on 5 July 2023).

- Vallerand, R. J., Pelletier, L. G., Blais, M. R., Briere, N. M., Senecal, C., & Vallieres, E. F. (1993). On the Assessment of Intrinsic, Extrinsic, and Amotivation in Education: Evidence on the Concurrent and Construct Validity of the Academic Motivation Scale. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 53(1), 159–172. [CrossRef]

- Cook, A. F., Arora, V. M., Rasinski, K. A., Curlin, F. A., & Yoon, J. D. (2014). The Prevalence of Medical Student Mistreatment and Its Association With Burnout. Academic Medicine, 89(5), 749. [CrossRef]

- Heru, A., Gagne, G., & Strong, D. (2009). Medical student mistreatment results in symptoms of posttraumatic stress. Academic Psychiatry: The Journal of the American Association of Directors of Psychiatric Residency Training and the Association for Academic Psychiatry, 33(4), 302–306. [CrossRef]

- Oser, T. K., Haidet, P., Lewis, P. R., Mauger, D. T., Gingrich, D. L., & Leong, S. L. (2014). Frequency and Negative Impact of Medical Student Mistreatment Based on Specialty Choice: A Longitudinal Study. Academic Medicine, 89(5), 755. [CrossRef]

- Neville, A. J. (2008). In the age of professionalism, student harassment is alive and well. Medical Education, 42(5), 447–448. [CrossRef]

- Wainipitapong, S., & Chiddaycha, M. (2022). Assessment of dropout rates in the preclinical years and contributing factors: A study on one Thai medical school. BMC Medical Education, 22(1), 461. [CrossRef]

-

Going directly from college to medical school: What it takes. (2019, August 15). American Medical Association. Available online: https://www.ama-assn.org/medical-students/preparing-medical-school/going-directly-college-medical-school-what-it-takes.

Table 1.

Demographic data.

Table 1.

Demographic data.

| |

Overall

(n= 399) |

Mistreatment

(n= 323, 80.95%) |

Non-Mistreatment

(n= 76, 19.05%) |

Test difference between two groups (Chi-square, p-value) |

| Age (years), median (IQR) |

23 (22-24 |

23 (22-24) |

23 (22-24) |

Z = -2.19, 0.029 |

| Medical student year (n, %) |

|

|

|

Z = 6.30, 0.043 |

| - 4th year |

157 (39.35%) |

119 (36.84%) |

38 (50.00%) |

|

| - 5th year |

109 (27.32%) |

96 (29.72%) |

13 (17.11%) |

|

| - 6th year |

133 (33.33%) |

108 (33.44%) |

25 (32.89%) |

|

| Biological sex (n, %) |

|

|

|

Z = 0.001, 0.970 |

| - Female |

246 (61.65%) |

199 (61.61%) |

47 (61.84%) |

|

| - Male |

153 (38.35%) |

124 (38.39%) |

29 (38.16%) |

|

| Gender identity (n, %) |

|

|

|

Z = 1.72, 0.943 |

| - Female |

216 (54.14%) |

176 (54.49%) |

40 (52.63%) |

|

| - Male |

124 (31.08%) |

98 (30.34%) |

26 (34.21%) |

|

| - Bisexual |

29 (7.27%) |

23 (7.12%) |

6 (7.89%) |

|

| - Gay |

23 (5.76%) |

20 (6.19%) |

3 (3.95%) |

|

| - Lesbian |

4 (1.00%) |

3 (0.93%) |

1 (1.32%) |

|

| - Pansexual |

1 (0.25%) |

1 (0.31%) |

0 |

|

| - Trans |

2 (0.50%) |

2 (0.62%) |

0 |

|

| Gender expression (n, %) |

|

|

|

Z = 3.08, 0.799 |

| - Female |

229 (57.39%) |

187 (57.89%) |

42 (55.26%) |

|

| - Male |

137 (34.34%) |

110 (34.06%) |

27 (35.53%) |

|

| - Bisexual |

11 (2.76%) |

9 (2.79%) |

2 (2.63%) |

|

| - Gay |

16 (4.01%) |

13 (4.02%) |

3 (3.95%) |

|

| - Lesbian |

4 (1.00%) |

2 (0.62%) |

2 (2.63%) |

|

| - Pansexual |

1 (0.25%) |

1 (0.31%) |

0 |

|

| - Trans |

1 (0.25%) |

1 (0.31%) |

0 |

|

| Sexual orientation (n, %) |

|

|

|

Z = 4.00, 0.549 |

| - Heterosexual |

293 (73.43%) |

234 (72.45%) |

59 (77.63%) |

|

| - Homosexual |

39 (9.77%) |

34 (10.53%) |

5 (6.58%) |

|

| - Bisexual |

56 (14.04%) |

44 (13.62%) |

12 (15.70%) |

|

| - LQBTQ |

5 (1.25%) |

5 (1.55%) |

0 |

|

| - Pansexual |

1 (0.25%) |

1 (0.31%) |

0 |

|

| - asexual |

5 (1.25%) |

5 (1.55%) |

0 |

|

| Underlying psychiatric disorder (n, %) |

|

|

|

|

| - Anxiety disorder |

15 (3.76%) |

13 (4.02%) |

2 (2.63%) |

Z = 0.33, 0.566 |

| - Depression |

29 (7.27%) |

27 (8.36%) |

2 (2.63%) |

Z = 2.99, 0.084 |

| - OCD |

4 (1.00%) |

4 (1.24%) |

0 |

Z = 0.95, 0.33 |

| Religion (n, %) |

|

|

|

Z = 2.03, 0.730 |

| - Buddhism |

329 (82.46%) |

263 (81.42%) |

66 (86.84%) |

|

| - Christian |

13 (3.26%) |

12 (3.72%) |

1 (1.32%) |

|

| Accommodation (n, %) |

|

|

|

Z = 16.86, 0.112 |

| - University dormitory |

253 (63.41%) |

206 (63.78%) |

47 (61.84%) |

|

| - Condominium |

86 (21.55%) |

73 (22.60%) |

13 (17.11%) |

|

| - House |

50 (12.53%) |

37 (11.46%) |

13 (17.11%) |

|

| Living with (n, %) |

|

|

|

Z = 2.44, 0.296 |

| Family member |

58 (14.54%) |

43 (13.31%) |

15 (19.74%) |

|

| Roommate |

144 (36.09%) |

116 (35.91%) |

28 (36.84%) |

|

| None |

197 (49.37%) |

164 (50.77%) |

33 (43.42%) |

|

| Monthly income (n, %) |

|

|

|

Z = 5.07, 0.167 |

| < 5000 baht/month |

24 (6.02%) |

22 (0.81%) |

2 (2.63%) |

|

| 5,000 - 9,999 baht/month |

172 (43.11%) |

139 (43.03%) |

33 (43.42%) |

|

| 10,000 - 14,999 baht/month |

163 (40.85%) |

134 (41.49%) |

29 (38.16%) |

|

| >15,000 baht/month |

40 (10.03%) |

28 (8.67%) |

12 (15.79%) |

|

| Number of ward/Department passed in the clinical years (median, IQR) |

13(8) |

13(8) |

13(8) |

Z=1.56, 0.120 |

Table 2.

Type and frequency of mistreatment.

Table 2.

Type and frequency of mistreatment.

Table 3.

Mistreatment details. Participants have the option to select more than one choice.

Table 3.

Mistreatment details. Participants have the option to select more than one choice.

| |

Number of responses |

% of responses |

| Rotation(s) students experienced mistreatment |

138 |

|

|

89 |

64.5 |

|

30 |

21.7 |

|

15 |

10.9 |

|

4 |

2.9 |

| Source(s) of mistreatment |

667 |

|

|

271 |

40.6 |

|

166 |

24.8 |

|

161 |

24.1 |

|

37 |

5.5 |

|

20 |

3.0 |

|

12 |

1.8 |

| Students’ reaction(s) to mistreatment |

893 |

|

| Anger |

207 |

23.2 |

|

184 |

20.6 |

|

134 |

15.0 |

|

88 |

9.9 |

|

80 |

9.0 |

|

78 |

8.7 |

|

69 |

7.7 |

|

28 |

3.1 |

|

25 |

2.8 |

| Students’ opinion on the maltreaters’ reason(s) of mistreatment in students |

649 |

|

|

187 |

28.8 |

|

125 |

19.3 |

|

120 |

18.5 |

|

102 |

15.7 |

|

72 |

11.1 |

|

34 |

5.2 |

|

9 |

1.4 |

| Reason(s) for not reporting mistreatment events experienced |

108 |

|

|

52 |

48.1 |

|

23 |

21.3 |

|

18 |

16.7 |

|

8 |

7.4 |

|

7 |

6.5 |

| Reason(s) for not reporting mistreatment events witnessed |

655 |

|

|

206 |

15.7 |

|

120 |

9.2 |

|

119 |

9.1 |

|

99 |

7.6 |

|

62 |

4.7 |

|

49 |

3.7 |

Table 4.

Association between mistreatment and academic motivation. Linear regression adjusting for age, sex, clinical year, previous ward/rotation and underlying condition.

Table 4.

Association between mistreatment and academic motivation. Linear regression adjusting for age, sex, clinical year, previous ward/rotation and underlying condition.

| |

Coefficient |

SD |

95% CI |

p-value |

| Motivation |

|

|

|

|

Verbal Mistreatment

(n=296, 74.2%) |

-8.41 |

2.83 |

-13.97 to -2.84 |

0.003 |

Physical Mistreatment

(n=74, 18.6%) |

1.22 |

3.18 |

-5.03 to 7.46 |

0.702 |

Sexual Mistreatment

(n=79, 19.8%) |

-0.65 |

3.17 |

-6.88 to 5.59 |

0.839 |

Discriminative Mistreatment

(n=147, 36.8%) |

-5.70 |

2.59 |

-10.79 to -0.62 |

0.028 |

Academic Mistreatment

(n=211, 52.88%) |

-8.62 |

2.45 |

-13.44 to -3.80 |

<0.001 |

All type Mistreatment

(n=323, 81.0%) |

-9.16 |

3.16 |

-15.37 to -2.95 |

0.004 |

| Amotivation |

|

|

|

|

Verbal Mistreatment

(n=296, 74.2%) |

0.16 |

0.79 |

-1.40 to 1.72 |

0.839 |

Physical Mistreatment

(n=74, 18.6%) |

1.33 |

0.88 |

-0.40 to 3.05 |

0.131 |

Sexual Mistreatment

(n=79, 19.8%) |

0.27 |

0.88 |

-1.45 to 2.00 |

0.755 |

Discriminative Mistreatment

(n=147, 36.8%) |

1.31 |

0.72 |

-0.11 to 2.72 |

0.070 |

Academic Mistreatment

(n=211, 52.88%) |

1.50 |

0.69 |

0.16 to 2.85 |

0.029 |

All type Mistreatment

(n=323, 81.0%) |

-0.02 |

0.88 |

-1.76 to 1.71 |

0.979 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).