Submitted:

08 July 2024

Posted:

10 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. General Characteristics of the Patients

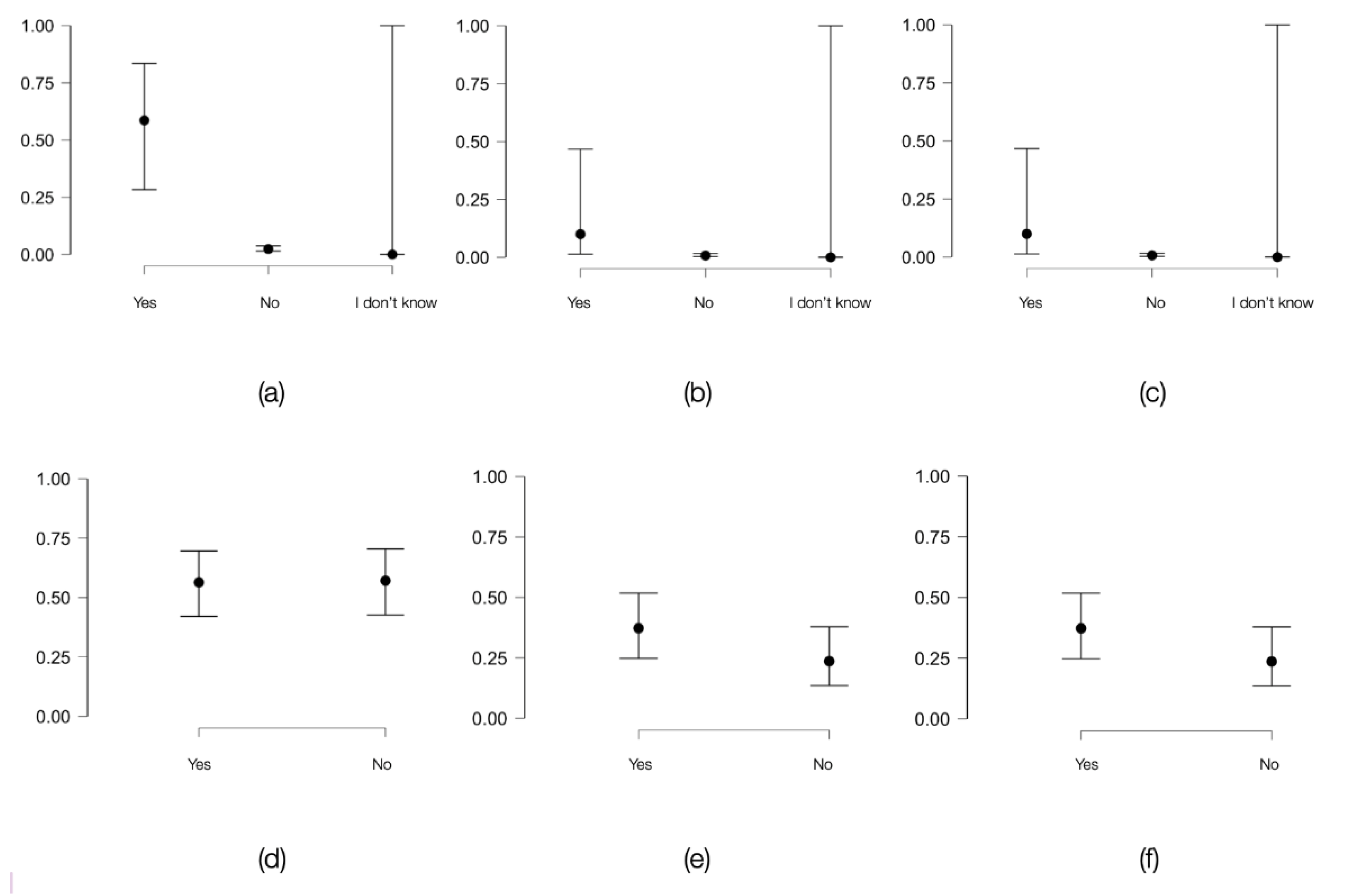

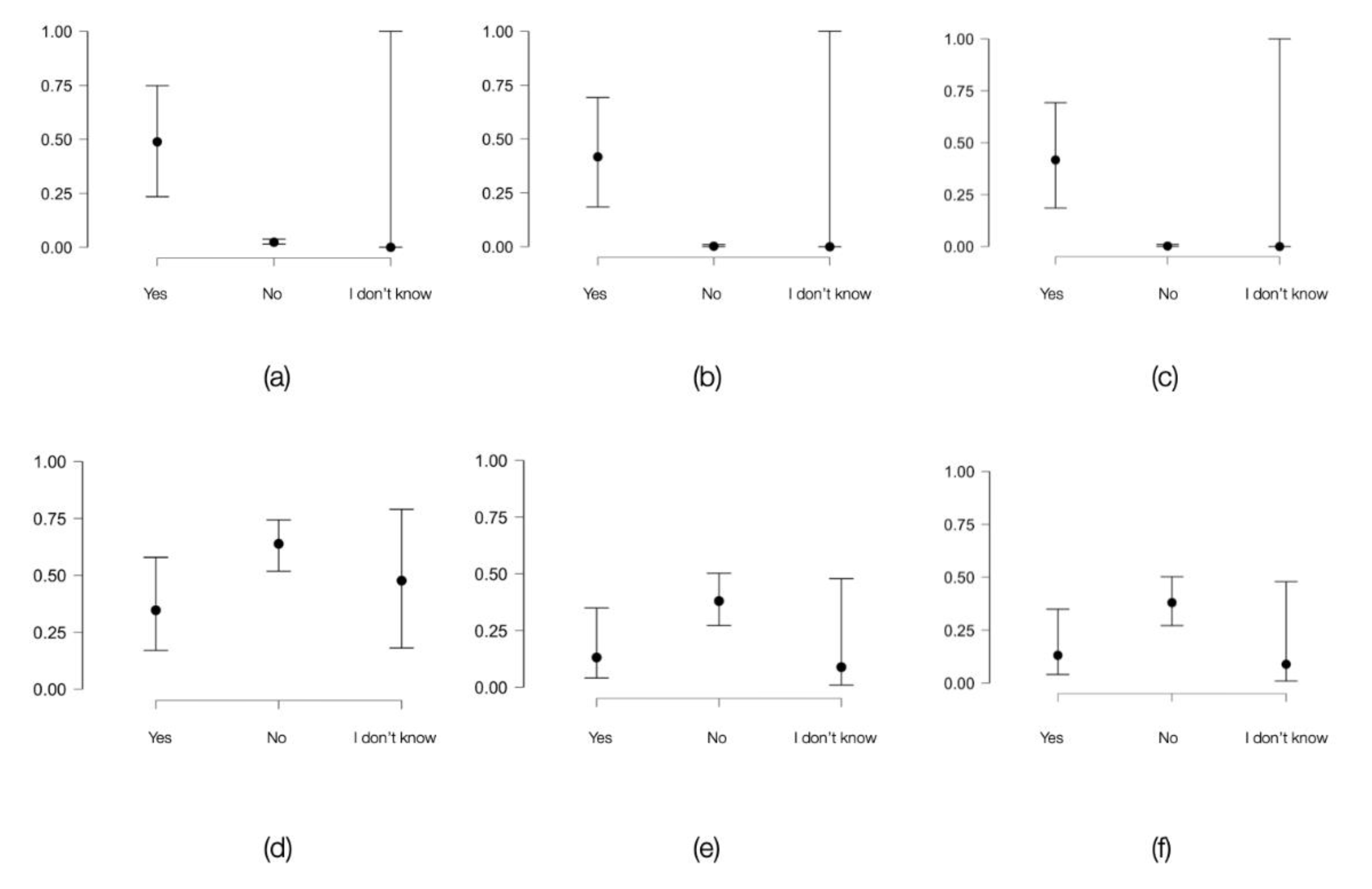

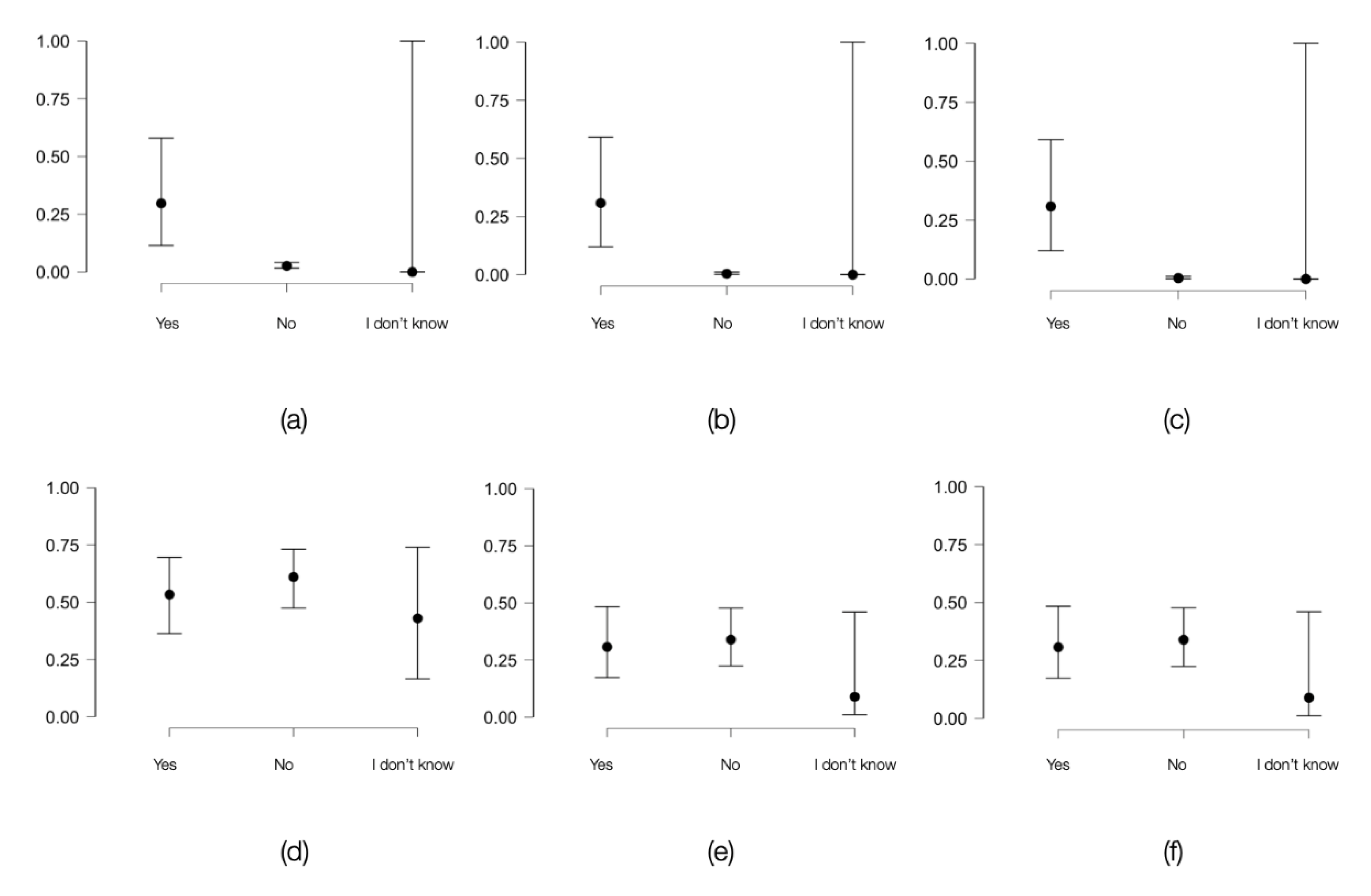

3.2. Correlations between Risk Factors and the Outcomes of the Screening

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. SDG target 3.3 communicable diseases; https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/topics/sdg-target-3_3-communicable-diseases.

- Mărdărescu M, Streinu-Cercel A, Popa M. Infecția cu HIV/SIDA: o actualizare a datelor din țara noastră. Infectio.ro 2018; 4 (52): 5-10.

- CNLAS, Romania. https://www.cnlas.ro/images/doc/2023/PREZENTARE-30 iunie-2023-site -07.08.2023.pdf.

- Sultana C, Erscoiu SM, Grancea C, Ceaușu E, Ruță S. Predictors of Chronic Hepatitis C Evolution in HIV Co-Infected Patients From Romania. Hepat Mon 2013; 13(2). [CrossRef]

- Kim AY, Onofrey S, Church DR. An epidemiologic update on hepatitis C infection in persons living with or at risk of HIV infection. J Infect Dis 2013; 207 (Suppl 1): S1-6. [CrossRef]

- Lingala S, Ghany MG. Natural History of Hepatitis C. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2015; 44(4): 717-34. [CrossRef]

- Huiban L, Stanciu C, Muzica CM, Cuciureanu T, Chiriac S., Zenovia S, et al. Hepatitis C Virus Prevalence and Risk Factors in a Village in Northeastern Romania - A Population-Based Screening - The First Step to Viral Micro-Elimination. Healthcare (Basel) 2021; 9(6): 651. [CrossRef]

- Niculescu I, Paraschiv S, Paraskevis D, Abagiu A, Batan I, Banica L, et al. Recent HIV-1 Outbreak Among Intravenous Drug Users in Romania: Evidence for Cocirculation of CRF14_BG and Subtype F1 Strains. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2015; 31(5): 488-95.

- Guvernul României 2022. The Government has approved two programs in the field of prevention, and psychological, social and medical care provided to drug users; https://www.gov.ro/en/government/cabinet-meeting/the-government-has-approved-two-programs-in-the-field-of-prevention-and-psychological-social-and-medical-care-provided-to-drug-users.

- AGENȚIA NAȚIONALĂ ANTIDROG, ROMÂNIA; http://ana.gov.ro/raportul-national-privind-situatia-drogurilor-in-romania-2020/.

- Strathdee SA, Kuo I, El-Bassel N, Hodder S, Smith LR, Springer SA. Preventing HIV outbreaks among people who inject drugs in the United States: plus ça change, plus ça même chose. AIDS 2020; 34(14): 1997-2005.

- Valera P, Chang Y, Lian Z. HIV risk inside U.S. prisons: a systematic review of risk reduction interventions conducted in U.S. prisons. AIDS Care 2017; 29(8): 943-952.

- Cdc.gov 2021. HIV Among People Who Inject Drugs | HIV by Group | HIV/AIDS | CDC; https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/hiv-idu.html.

- Rosengard C, Anderson B, Stein M. Intravenous drug users’ HIV-risk behaviors with primary/other partners. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 2004; 30(2): 225-36.

- Amirkhanian Y. Review of HIV vulnerability and condom use in central and eastern Europe. Sex Health 2012; 9(1): 34-43.

- Basu D, Sharma AK, Gupta S, Nebhinani N, Kumar V. Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection & risk factors for HCV positivity in injecting & non-injecting drug users attending a de-addiction centre in northern India. Indian J Med Res 2015; 142(3): 311-6.

- Bartholomew TS, Onugha J, Bullock C, Scaramutti C, Patel H, Forrest DW, et al. Baseline prevalence and correlates of HIV and HCV infection among people who inject drugs accessing a syringe services program. Harm Reduct J 2020; 17, 40.

- Mata-Marín JA, de Pablos-Leal AA, Mauss S, Arroyo-Anduiza CI, Rodríguez-Evaristo MS, Uribe-Noguéz LA, et al. Risk factors for HCV transmission in HIV-positive men who have sex with men in México. PLoS One 2022; 17(7): e0269977.

- European Study Group On Heterosexual Transmission Of HIV. Comparison Of Female To Male And Male To Female Transmission Of HIV In 563 Stable Couples. BMJ: British Medical Journal 1992; vol. 304, nr. 6830: 809–813.

- Ganley KY, Wilson-Barthes M, Zullo AR, Sosa-Rubí SG, Conde-Glez CJ, García-Cisneros S, et al. Incidence and time-varying predictors of HIV and sexually transmitted infections among male sex workers in Mexico City. Infect Dis Poverty 2021; 10(1): 7.

- Kloek M, Bulstra CA, Chabata ST, Fearon E, Taramusi I, de Vlas SJ, et al. No increased HIV risk in general population near sex work sites: A nationally representative cross-sectional study in Zimbabwe. Trop Med Int Health 2022; 27(8): 696-704. [CrossRef]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. HIV/AIDS surveillance in Europe 2023 (2022 data); https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/hivaids-surveillance-europe-2023-2022-data.

- Ward H, Rönn M. Contribution of sexually transmitted infections to the sexual transmission of HIV. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2010; 5(4): 305-10.

- Barker EK, Malekinejad M, Merai R, Lyles CM, Sipe TA, DeLuca JB, Ridpath D, et al. Risk of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Acquisition Among High-Risk Heterosexuals With Nonviral Sexually Transmitted Infections: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sex Transm Dis 2022; 49(6): 383-397. [CrossRef]

- Council of Europe Annual Penal Statistics; https://wp.unil.ch/space/files/2021/04/210330_FinalReport_SPACE_I_2020.pdf.

- Barros I, Santana-da-Silva N, Nogami Y, Santos e Santos C, Pereira L; França E, et al. Immunogenetic Profile Associated with Patients Living with HIV-1 and Epstein–Barr Virus (EBV) in the Brazilian Amazon Region. Viruses 2024; 16, 1012.

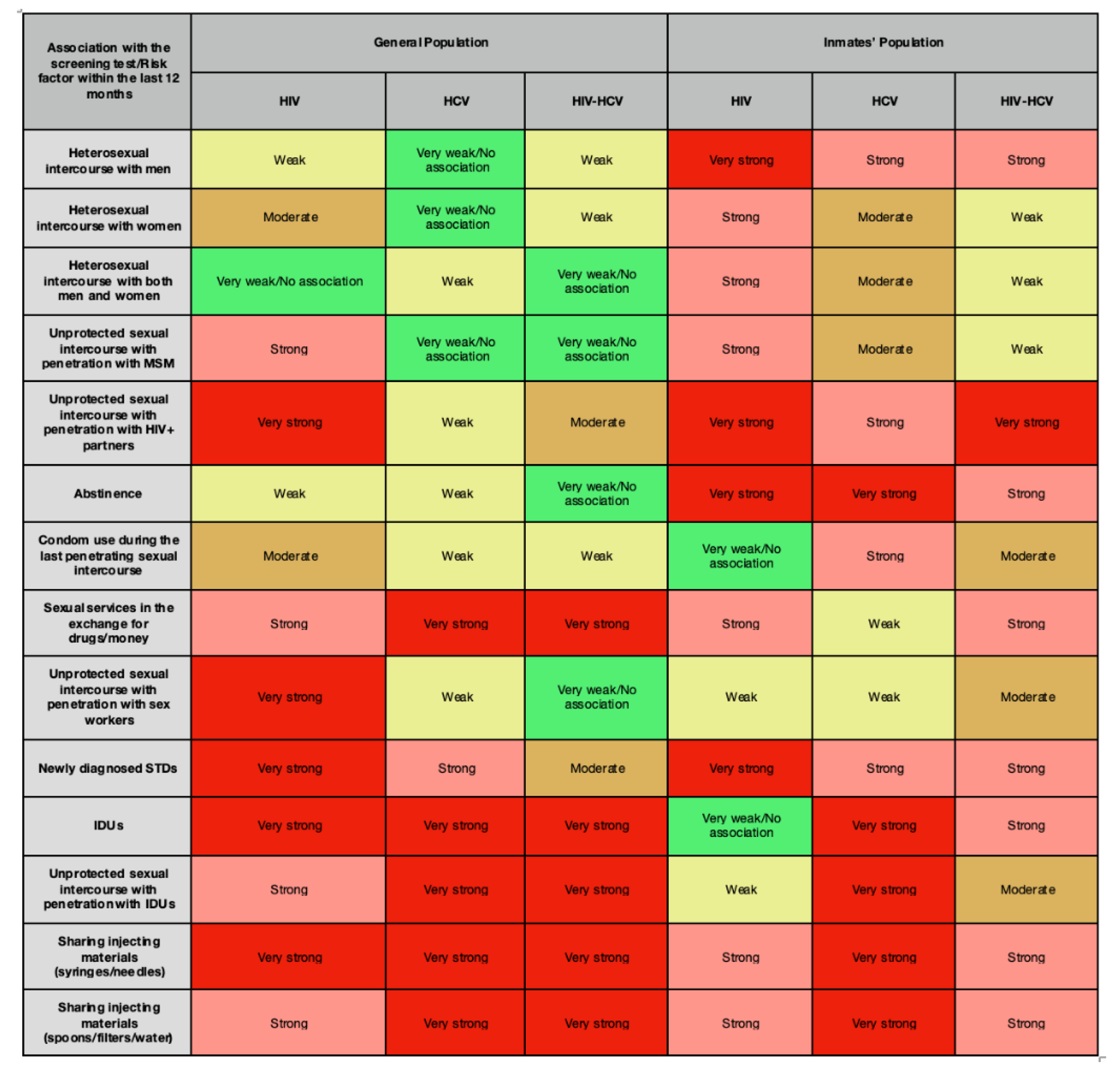

| Risk Factor | Chi-squared Test | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chi-squared Test | Adjusted Chi-squared Test | P Value of Chi-squared Test | P Value of Adjusted Chi-squared Test | Degrees of Freedom | Association Coefficient Phi | Cramer’s V Coefficient | |||||||

| Sexual intercourse with men | HIV | 4.71 | 3.87 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 1 | 0.07 | 0.07 | |||||

| HCV | 0.76 | 0.43 | 0.38 | 0.51 | 1 | 0.03 | 0.03 | ||||||

| HIV-HCV | 2.71 | 1.59 | 0.09 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.05 | 0.05 | ||||||

| Sexual intercourse with women | HIV | 10.24 | 8.89 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 0.11 | 0.11 | |||||

| HCV | 0.5 | 0.22 | 0.47 | 0.63 | 1 | 0.02 | 0.02 | ||||||

| HIV-HCV | 2.58 | 1.42 | 0.1 | 0.23 | 1 | 0.05 | 0.05 | ||||||

| Sexual intercourse with both men and women | HIV | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.85 | 0.85 | 2 | - | 19 | |||||

| HCV | 2.93 | 2.93 | 0.23 | 0.23 | 2 | - | 0.06 | ||||||

| HIV-HCV | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 2 | - | 0.01 | ||||||

| Unprotected sexual intercourse with men who have sex with men (MSM) | HIV | 18.58 | 18.58 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 2 | - | 0.15 | |||||

| HCV | 0.42 | 0.42 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 2 | - | 0.02 | ||||||

| HIV-HCV | 134 | 134 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 2 | - | 0.01 | ||||||

| Unprotected sexual intercourse with HIV+ partners | HIV | 104.65 | 104.65 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 2 | - | 0.36 | |||||

| HCV | 2.14 | 2.14 | 0.34 | 0.34 | 2 | - | 0.05 | ||||||

| HIV-HCV | 9.84 | 9.84 | 7 | 7 | 2 | - | 0.11 | ||||||

| Abstinence | HIV | 6.04 | 5.07 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 1 | 0.08 | 0.08 | |||||

| HCV | 3.93 | 3.09 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 1 | 0.07 | 0.07 | ||||||

| HIV-HCV | 0.05 | <1 | 0.81 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 8 | ||||||

| Condom use during the last penetrating sexual intercourse | HIV | 14.4 | 12.92 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 1 | 0.13 | 0.13 | |||||

| HCV | 4.17 | 3.32 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 1 | 0.07 | 0.07 | ||||||

| HIV-HCV | 5.55 | 3.09 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 1 | 0.08 | 0.08 | ||||||

| Sexual intercourse in exchange for drugs/money | HIV | 35.52 | 23.87 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 1 | 0.21 | 0.21 | |||||

| HCV | 125.52 | 100.77 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 1 | 0.39 | 0.39 | ||||||

| HIV-HCV | 144.6 | 99.58 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 1 | 0.42 | 0.42 | ||||||

| Unprotected sexual intercourse with sex workers | HIV | 56.65 | 56.65 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 2 | - | 0.26 | |||||

| HCV | 2.93 | 2.93 | 0.23 | 0.23 | 2 | - | 0.06 | ||||||

| HIV-HCV | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 2 | - | 0.01 | ||||||

| Newly diagnosed sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) | HIV | 91.09 | 91.09 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 2 | - | 0.33 | |||||

| HCV | 29.64 | 29.64 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 2 | - | 0.19 | ||||||

| HIV-HCV | 7.98 | 7.98 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 2 | - | 0.1 | ||||||

| Intravenous drug users (IDUs) | HIV | 84.01 | 84.01 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 2 | - | 0.32 | |||||

| HCV | 284.38 | 284.38 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 2 | - | 0.59 | ||||||

| HIV-HCV | 263.95 | 263.95 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 2 | - | 0.57 | ||||||

| Unprotected sexual intercourse with IDUs | HIV | 32.2 | 32.2 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 2 | - | 0.2 | |||||

| HCV | 138.12 | 138.12 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 2 | - | 0.41 | ||||||

| HIV-HCV | 137.21 | 137.21 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 2 | - | 0.41 | ||||||

| Common use of injecting materials (syringes/needles) | HIV | 85.39 | 85.39 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 2 | - | 0.32 | |||||

| HCV | 141.86 | 141.86 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 2 | - | 0.42 | ||||||

| HIV-HCV | 235.5 | 235.5 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 2 | - | 0.54 | ||||||

| Common use of injecting materials (spoons/filters/water) | HIV | 30.53 | 30.53 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 2 | - | 0.19 | |||||

| HCV | 50.74 | 50.74 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 2 | - | 0.25 | ||||||

| HIV-HCV | 114.03 | 114.03 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 2 | - | 0.37 | ||||||

| Risk Factor | Chi-squared Test | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chi-squared Test | Adjusted Chi-squared Test | P Value of Chi-squared Test | P Value of Adjusted Chi-squared Test | Degrees of Freedom | Association Coefficient Phi | Cramer’s V Coefficient | |||||||

| Sexual intercourse with men | HIV | 9.95 | 7.89 | <0.05 | <0.05 | 1 | 0.32 | 0.32 | |||||

| HCV | 3.87 | 2.67 | 0.04 | 0.1 | 1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | ||||||

| HIV-HCV | 4.99 | 3.05 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 1 | 0.22 | 0.22 | ||||||

| Sexual intercourse with women | HIV | 3.23 | 2.13 | 0.07 | 0.14 | 1 | 0.18 | 0.18 | |||||

| HCV | 1.69 | 0.93 | 0.19 | 0.33 | 1 | 0.13 | 0.13 | ||||||

| HIV-HCV | 0.62 | 0.18 | 0.42 | 0.66 | 1 | 0.08 | 0.08 | ||||||

| Sexual intercourse with both men and women | HIV | 2.67 | 0.83 | 0.1 | 0.36 | 1 | 0.16 | 0.16 | |||||

| HCV | 2 | 0.49 | 0.15 | 0.48 | 1 | 0.14 | 0.14 | ||||||

| HIV-HCV | 0.91 | 0.03 | 0.33 | 0.85 | 1 | 0.09 | 0.09 | ||||||

| Unprotected sexual intercourse with men who have sex with men (MSM) | HIV | 2.67 | 0.83 | 0.1 | 0.36 | 1 | 0.16 | 0.16 | |||||

| HCV | 2 | 0.49 | 0.15 | 0.48 | 1 | 0.14 | 0.14 | ||||||

| HIV-HCV | 0.91 | 0.03 | 0.33 | 0.85 | 1 | 0.09 | 0.09 | ||||||

| Unprotected sexual intercourse with HIV+ partners | HIV | 7.99 | 7.99 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 2 | - | 0.28 | |||||

| HCV | 8.74 | 8.74 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 2 | - | 0.3 | ||||||

| HIV-HCV | 5.12 | 5.12 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 2 | - | 0.23 | ||||||

| Abstinence | HIV | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.89 | 0.89 | 2 | - | 0.04 | |||||

| HCV | 5.02 | 5.02 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 2 | - | 0.23 | ||||||

| HIV-HCV | 1.46 | 1.46 | 0.48 | 0.48 | 2 | - | 0.12 | ||||||

| Condom use during the last penetrating sexual intercourse | HIV | 4.17 | 2.61 | 0.04 | 0.1 | 1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | |||||

| HCV | 0.66 | 0.15 | 0.41 | 0.69 | 1 | 0.08 | 0.08 | ||||||

| HIV-HCV | 7.99 | 7.99 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 2 | - | 0.28 | ||||||

| Sexual intercourse in exchange for drugs/money | HIV | 4.17 | 2.61 | 0.04 | 0.1 | 1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | |||||

| HCV | 0.66 | 0.15 | 0.41 | 0.69 | 1 | 0.08 | 0.08 | ||||||

| HIV-HCV | 2.86 | 1.52 | 0.09 | 0.21 | 1 | 0.17 | 0.17 | ||||||

| Unprotected sexual intercourse with sex workers | HIV | 0.68 | 0.05 | 0.4 | 0.81 | 1 | 0.08 | 0.08 | |||||

| HCV | 0.32 | <1 | 0.57 | 1 | 1 | 0.05 | 0.05 | ||||||

| HIV-HCV | 1.38 | 0.29 | 0.23 | 0.58 | 1 | 0.12 | 0.12 | ||||||

| Newly diagnosed sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) | HIV | 9.28 | 8.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | 1 | 0.3 | 0.3 | |||||

| HCV | 5.71 | 4.77 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 1 | 0.24 | 0.24 | ||||||

| HIV-HCV | 4.26 | 3.39 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 1 | 0.21 | 0.21 | ||||||

| Intravenous drug users (IDUs) | HIV | 8 | 0 | 0.92 | 1 | 1 | 9 | 9 | |||||

| HCV | 20.87 | 19.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | 1 | 0.46 | 0.46 | ||||||

| HIV-HCV | 2.85 | 2.16 | 0.09 | 0.14 | 1 | 0.17 | 0.17 | ||||||

| Unprotected sexual intercourse with IDUs | HIV | 0.85 | 0.85 | 0.65 | 0.65 | 2 | - | 0.09 | |||||

| HCV | 13.72 | 13.72 | <0.05 | <0.05 | 2 | - | 0.37 | ||||||

| HIV-HCV | 1.82 | 1.82 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 2 | - | 0.13 | ||||||

| Common use of injecting materials (syringes/needles) | HIV | 4.27 | 4.27 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 2 | - | 0.21 | |||||

| HCV | 7.06 | 7.06 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 2 | - | 0.27 | ||||||

| HIV-HCV | 4.57 | 4.57 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 2 | - | 0.21 | ||||||

| Common use of injecting materials (spoons/filters/water) | HIV | 3.27 | 3.27 | 0.19 | 0.19 | 2 | - | 0.18 | |||||

| HCV | 8.06 | 8.06 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 2 | - | 0.28 | ||||||

| HIV-HCV | 4.06 | 4.06 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 2 | - | 0.2 | ||||||

| Risk Factor | Chi-squared Test | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR Reactive vs Non-reactive * | P Value | OR Age ** | P Value | OR Exposed vs Non-exposed *** | P Value | OR Exposed vs No response **** | P Value | ||

| Sexual intercourse with men | HIV | 0.04 | <0.001 | 0.98 | 0.2 | 2.56 | 0.02 | - | - |

| HCV | 4 | <0.001 | 0.99 | 0.92 | 1.54 | 0.12 | - | - | |

| HIV-HCV | 4 | <0.001 | 0.99 | 0.92 | 3.66 | 0.12 | - | - | |

| Sexual intercourse with women | HIV | 0.11 | <0.001 | 0.98 | 0.36 | 0.29 | 3 | - | - |

| HCV | 0.01 | <0.001 | 1 | 0.95 | 0.31 | 0.12 | - | - | |

| HIV-HCV | 0.01 | <0.001 | 1 | 0.95 | 0.31 | 0.12 | - | - | |

| Sexual intercourse with both men and women | HIV | <1 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.31 | >1 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 1 |

| HCV | <1 | 0.99 | 1 | 0.98 | >1 | 0.99 | 1 | 1 | |

| HIV-HCV | <1 | 0.99 | 1 | 0.98 | >1 | 0.99 | 1 | 1 | |

| Unprotected sexual intercourse with men who have sex with men (MSM) | HIV | 0.48 | 0.38 | 0.98 | 0.44 | 0.09 | <0.001 | <1 | 0.98 |

| HCV | <1 | 0.99 | 1 | 0.98 | >1 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 1 | |

| HIV-HCV | <1 | 0.99 | 1 | 0.98 | >1 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 1 | |

| Unprotected sexual intercourse with HIV+ partners | HIV | 2.06 | 0.28 | 0.98 | 0.36 | 0.01 | <0.001 | <1 | 0.98 |

| HCV | 0.11 | 0.04 | 1 | 0.99 | 0.06 | 0.01 | <1 | 0.99 | |

| HIV-HCV | 0.11 | 0.04 | 1 | 0.99 | 0.06 | 0.01 | <1 | 0.99 | |

| Abstinence | HIV | 0.08 | <0.001 | 0.98 | 0.31 | 0.27 | 0.02 | - | - |

| HCV | 8 | <0.001 | 1 | 0.99 | 1.02 | 0.81 | - | - | |

| HIV-HCV | 8 | <0.001 | 1 | 0.99 | 1.02 | 0.81 | - | - | |

| Condom use during the last penetrating sexual intercourse | HIV | 0.01 | <0.001 | 0.98 | 0.2 | 10.42 | 2 | - | - |

| HCV | <1 | 0.98 | 0.99 | 0.92 | >1 | 0.99 | - | - | |

| HIV-HCV | <1 | 0.98 | 0.99 | 0.92 | >1 | 0.99 | - | - | |

| Sexual intercourse in exchange for drugs/money | HIV | 1.21 | 0.83 | 0.98 | 0.38 | 0.04 | <0.001 | - | - |

| HCV | 0.73 | 0.69 | 1 | 0.91 | 7 | <0.001 | - | - | |

| HIV-HCV | 0.73 | 0.69 | 1 | 0.91 | 7 | <0.001 | - | - | |

| Unprotected sexual intercourse with sex workers | HIV | 1.45 | 0.66 | 0.98 | 0.47 | 0.03 | <0.001 | <1 | 0.98 |

| HCV | <1 | 0.99 | 1 | 0.98 | >1 | 0.99 | 1 | 1 | |

| HIV-HCV | <1 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.98 | >1 | 0.99 | 1 | 1 | |

| Newly diagnosed sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) | HIV | 0.29 | 0.19 | 0.98 | 0.27 | 0.16 | 0.02 | 7.05 | 0.03 |

| HCV | <1 | 0.99 | 1 | 0.98 | >1 | 0.99 | >1 | 0.99 | |

| HIV-HCV | <1 | 0.99 | 1 | 0.98 | >1 | 0.99 | >1 | 0.99 | |

| Intravenous drug users (IDUs) | HIV | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.98 | 0.45 | 0.03 | <0.001 | <1 | 0.98 |

| HCV | 1 | 0.04 | 1.17 | 0.06 | <1 | 0.92 | <1 | 1 | |

| HIV-HCV | 1 | 0.04 | 1.17 | 0.06 | <1 | 0.92 | <1 | 1 | |

| Unprotected sexual intercourse with IDUs | HIV | 0.81 | 0.8 | 0.98 | 0.32 | 0.06 | <0.001 | <1 | 0.98 |

| HCV | 0.43 | 0.19 | 1 | 0.93 | 9 | <0.001 | <1 | 0.99 | |

| HIV-HCV | 0.43 | 0.19 | 1 | 0.93 | 9 | <0.001 | <1 | 0.99 | |

| Common use of injecting materials (syringes/needles) | HIV | 1.94 | 0.44 | 0.98 | 0.3 | 0.02 | <0.001 | <1 | 0.98 |

| HCV | 0.69 | 0.56 | 1 | 0.9 | 0.92 | <0.001 | >1 | 0.99 | |

| HIV-HCV | 0.69 | 0.56 | 1 | 0.9 | 4 | <0.001 | <1 | 0.99 | |

| Common use of injecting materials (spoons/filters/water) | HIV | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.98 | 0.26 | 0.11 | <0.001 | <1 | 0.98 |

| HCV | 0.15 | 0.12 | 1 | 0.91 | <1 | 0.99 | <1 | 0.99 | |

| HIV-HCV | 0.15 | 0.12 | 1 | 0.91 | <1 | 0.99 | <1 | 0.99 | |

| Risk Factor | Chi-squared Test | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR Reactive vs Non-reactive * | P Value | OR Age ** | P Value | OR Exposed vs Non-exposed *** | P Value | OR Exposed vs No response **** | P Value | ||

| Sexual intercourse with men | HIV | 0.36 | 0.45 | 0.96 | 0.17 | 18.57 | <0.05 | - | - |

| HCV | <1 | 0.99 | 0.95 | 0.06 | >1 | 0.98 | - | - | |

| HIV-HCV | <1 | 0.99 | 0.95 | 0.06 | >1 | 0.98 | - | - | |

| Sexual intercourse with women | HIV | 3.65 | 0.19 | 0.97 | 0.35 | 0.26 | 0.06 | - | - |

| HCV | 2.25 | 0.44 | 0.96 | 0.13 | 0.45 | 0.34 | - | - | |

| HIV-HCV | 2.25 | 0.44 | 0.96 | 0.13 | 0.45 | 0.34 | - | - | |

| Sexual intercourse with both men and women | HIV | <1 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.44 | >1 | 0.98 | - | - |

| HCV | <1 | 0.99 | 0.96 | 0.15 | >1 | 0.99 | - | - | |

| HIV-HCV | <1 | 0.99 | 0.96 | 0.15 | >1 | 0.99 | - | - | |

| Unprotected sexual intercourse with men who have sex with men (MSM) | HIV | <1 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.44 | >1 | 0.98 | - | - |

| HCV | <1 | 0.99 | 0.96 | 0.15 | >1 | 0.99 | - | - | |

| HIV-HCV | <1 | 0.99 | 0.96 | 0.15 | >1 | 0.99 | - | - | |

| Unprotected sexual intercourse with HIV+ partners | HIV | <1 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.56 | >1 | 0.99 | >1 | 0.98 |

| HCV | <1 | 0.99 | 0.96 | 0.2 | >1 | 0.99 | >1 | 0.99 | |

| HIV-HCV | <1 | 0.99 | 0.96 | 0.2 | >1 | 0.99 | >1 | 0.99 | |

| Abstinence | HIV | 2.59 | 0.34 | 0.99 | 0.73 | 0.23 | 9 | 0.52 | 0.38 |

| HCV | 2.68 | 0.37 | 0.96 | 0.17 | 0.31 | 92 | 0.19 | 0.14 | |

| HIV-HCV | 2.68 | 0.37 | 0.96 | 0.17 | 0.31 | 0.09 | 0.19 | 0.14 | |

| Condom use during the last penetrating sexual intercourse | HIV | 2.36 | 0.41 | 0.98 | 0.48 | 1.12 | 0.82 | 0.76 | 0.75 |

| HCV | 2.37 | 0.46 | 0.95 | 0.11 | 1.17 | 0.77 | 0.26 | 0.26 | |

| HIV-HCV | 2.37 | 0.46 | 0.95 | 0.11 | 1.17 | 0.77 | 0.26 | 0.26 | |

| Sexual intercourse in exchange for drugs/money | HIV | 0.47 | 0.58 | 0.97 | 0.28 | 8.87 | 0.05 | - | - |

| HCV | <1 | 0.99 | 0.95 | 0.08 | >1 | 0.99 | - | - | |

| HIV-HCV | <1 | 0.99 | 0.95 | 0.08 | >1 | 0.99 | - | - | |

| Unprotected sexual intercourse with sex workers | HIV | 0.91 | 0.95 | 0.98 | 0.43 | 3.13 | 0.36 | - | - |

| HCV | <1 | 0.99 | 0.96 | 0.11 | >1 | 0.99 | - | - | |

| HIV-HCV | <1 | 0.99 | 0.96 | 0.11 | >1 | 0.99 | - | - | |

| Newly diagnosed sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) | HIV | 2.77 | 0.3 | 1.002 | 0.93 | 0.25 | 4 | - | - |

| HCV | 1.95 | 0.52 | 0.97 | 0.33 | 0.44 | 0.07 | - | - | |

| HIV-HCV | 1.95 | 0.52 | 0.97 | 0.33 | 0.44 | 0.07 | - | - | |

| Intravenous drug users (IDUs) | HIV | 2.04 | 0.36 | 0.98 | 0.51 | 1.03 | 0.94 | - | - |

| HCV | 1.86 | 0.55 | 0.97 | 0.28 | 0.52 | 0.15 | - | - | |

| HIV-HCV | 1.86 | 0.55 | 0.97 | 0.28 | 0.52 | 0.15 | - | - | |

| Unprotected sexual intercourse with IDUs | HIV | 2.63 | 0.32 | 0.98 | 0.38 | 1.36 | 0.49 | 0.65 | 0.58 |

| HCV | 2.65 | 0.37 | 0.95 | 0.1 | 1.15 | 0.76 | 0.22 | 0.19 | |

| HIV-HCV | 2.65 | 0.37 | 0.95 | 0.1 | 1.15 | 0.76 | 0.22 | 0.19 | |

| Common use of injecting materials (syringes/needles) | HIV | 1.62 | 0.63 | 0.97 | 0.25 | 3.32 | 0.03 | 1.71 | 0.53 |

| HCV | 1.38 | 0.78 | 0.94 | 51 | 4.05 | 0.04 | 0.64 | 0.73 | |

| HIV-HCV | 1.38 | 0.78 | 0.94 | 51 | 5.04 | 0.04 | 0.64 | 0.73 | |

| Common use of injecting materials (spoons/filters/water) | HIV | 1.62 | 0.63 | 0.97 | 0.29 | 2.86 | 0.05 | 1.56 | 0.6 |

| HCV | 1.37 | 0.79 | 0.95 | 0.06 | 3.06 | 0.06 | 0.6 | 0.69 | |

| HIV-HCV | 1.37 | 0.79 | 0.95 | 0.06 | 3.06 | 0.06 | 0.6 | 0.69 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).