1. Introduction

In recent years, the higher education sector has undergone significant transformation. This has resulted from the rapid advancement of technology, evolving pedagogical theories, and the changing demands of the modern workforce. In addition, there is a growing need for educational methodologies that equip students with practical skills and critical thinking abilities as the business environment becomes increasingly complex. Kasch et al. [

1] explain that academic institutions should engage students in real-life complex problems to help them gain knowledge and develop skills that meet the needs of the 21st-century workplace. As a result, higher education institutions have adopted innovative instructional strategies, including simulation-based learning (SBL), problem-based learning (PBL), and challenge-based learning (CBL). SBL is a powerful educational tool that bridges the gap between theoretical knowledge and practical application. Hallinger and Wang [

2] found that SBL has more positive learning outcomes than traditional teaching methods like discussions and lectures. For instance, the scholars found that 7 out of 9 students in SBL programs performed better in standard exams and felt they learned more than in traditional teaching settings. The SBL achieves these higher outcomes by immersing students in realistic business scenarios, which provide a risk-free environment to experiment with different strategies, make decisions, and observe the consequences of their actions.

Similarly, PBL offers a student-centred pedagogy that emphasizes learning through the structured exploration of complex, real-world problems. Yew and Goh [

3] (p.76), describe it as a pedagogical approach where students can ”problem-solve in a collaborative setting, create mental models for learning, and form self-directed learning habits through practice and reflection.” This methodology enhances their problem-solving skills develops self-directed learning, critical thinking, and the ability to apply knowledge in practical contexts. On the other hand, CBL further extends the principles of PBL by incorporating real-world challenges posed by industry partners and communities. Kasch et al. [

1] (p.3) define CBL as “an active learning approach in which students gain skills and knowledge through active engagement with an urgent real-life challenge and collaborative work on creative and sustainable solutions.” This approach engages students in authentic, meaningful projects and builds a sense of social responsibility and innovation. It encourages entrepreneurial thinking, creativity, and collaboration, as students must often work with diverse stakeholders to address complex issues.

Integrating SBL, PBL, and CBL into business higher education represents a paradigm shift towards more experiential, student-centered learning environments. These methodologies aim to produce knowledgeable graduates adept at applying their knowledge in real-world settings. This helps meet the requirements of the contemporary workforce, which involves the ability to adapt, innovate, and collaborate. This research paper provides a comprehensive analysis of these learning approaches, highlighting their benefits, challenges, and implications for the future of business education. It aims to contribute to educational innovation and offer insights into how business schools can better prepare students for the demands of the contemporary business environment. The research question that guides the study is therefore ‘What are the advantages, challenges and implications of SBL, PBL and CBL altogether, in the training of business students?’

2. Materials and Methods

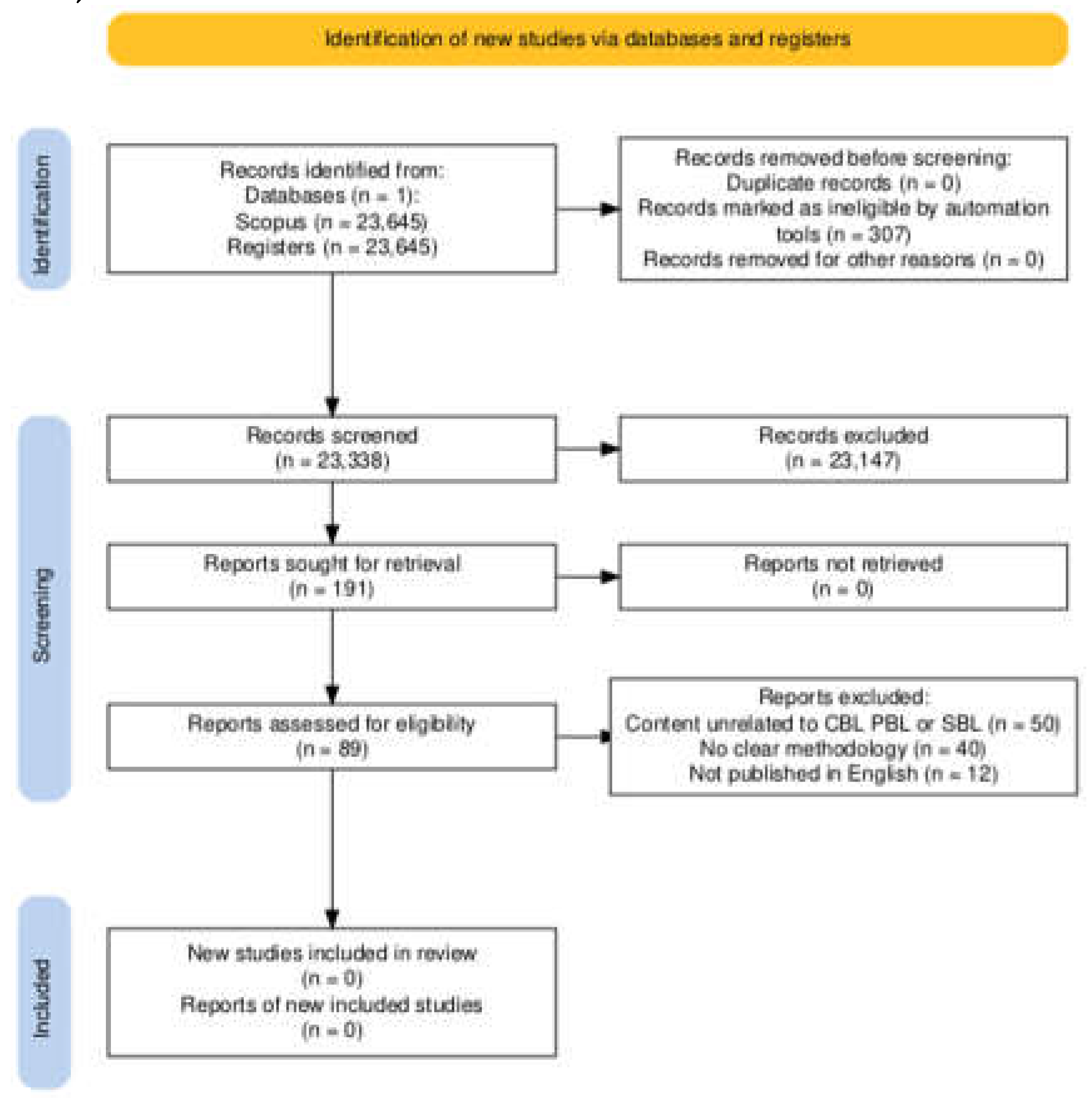

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines guided the systematic review process. According to Page et al. [

4], this framework was designed to help systematic reviewers systematically report reasons for conducting the review, the methods used, and the findings. Similarly, Haddaway et al. [

5] indicate that the PRISMA 2020 model encourages researchers to sufficiently describe the methods and results of systematic reviews, thereby ensuring transparency. The flow diagram allows readers to understand the main procedures and assess the sources’ relevancy.

The researcher employed a systematic bibliometric literature review (LRSB) methodology, which offers a thorough and unbiased approach to examining existing literature. This method ensures that the research encompasses various studies and theoretical perspectives. Additionally, Simulation-Based Learning; Problem-Based Learning; and Challenge-Based Learning are interdisciplinary strategies that integrate educational theory, practices, and pedagogical innovations. The LRSB method aids in identifying, analyzing, and synthesizing data across various academic fields. Unlike traditional literature reviews, LRSB utilizes a replicable, scientific, and transparent process designed to minimize bias by conducting an exhaustive search of both published and unpublished literature on the study topic [

6]. The researcher also maintains an audit trail, enabling readers to evaluate the quality of the included studies, as well as the research procedures and conclusions. As a result, LRSB involves a comprehensive screening and selection of information sources through three phases and six steps [

6], as detailed in

Table 1, to ensure the validity and accuracy of the presented data.

The researchers carried out their literature search using the Scopus database, which is highly regarded in scientific and academic circles. However, it is important to recognize the limitations of this study due to its exclusive reliance on the Scopus database, thereby excluding other scientific and academic databases. Ideally, the literature search should include peer-reviewed scientific and academic publications up to May 2024.

For this study, the Scopus database was used to search for relevant materials. Keywords “Simulation-Based Learning” were used for the initial search, resulting in 1454 document results. Adding the keyword “Problem-Based Learning” expanded the search and increased the results to 23148. This number then increased to 23645 when the researcher added “Challenge-Based Learning.” The exact keyword “higher education” was added at this point, reducing the search results to 1491 records. Finally, the search was limited to the subject area “business,” which reduced the found documents to 191. No publication date restrictions were imposed since the researcher prioritized the relevance of the materials over their oldness. However, inclusion and exclusion criteria were used to ensure that the sources used for the review were relevant to the study topic and reliable. For instance, sources unrelated to SBL, CBL, and PBL were excluded. Only academic and scientific materials, such as peer-reviewed articles, conference papers, books, and book chapters, were included. The studies selected had to be published in English and showcase rigorous research methodology. After screening the sources based on these eligibility criteria, 89 documents were selected for inclusion in the final report (N=89) (

Figure 1).

A set of standards aimed at improving the transparency and quality of systematic reviews is provided by the PRISMA 2020 guidelines. These guidelines offer a detailed checklist and a flow diagram to assist researchers in reporting their systematic reviews clearly and comprehensively. This effort is essential to ensure that scientific evidence is robust and reliable, thereby facilitating informed decision-making in clinical practice and scientific research [

4].

For data analysis, we utilized content and thematic analysis methods to categorize and discuss the diverse documents, as recommended by Rosário and Dias [

6].

The 89 documents indexed in Scopus were analyzed both narratively and bibliometrically to deepen our understanding of the content and to identify common themes that directly address the research question [

6]. Among the selected documents, 63 are articles; 14 are conference proceedings; 9 are books, and 4 are part of a book series.

3. Publication Distribution

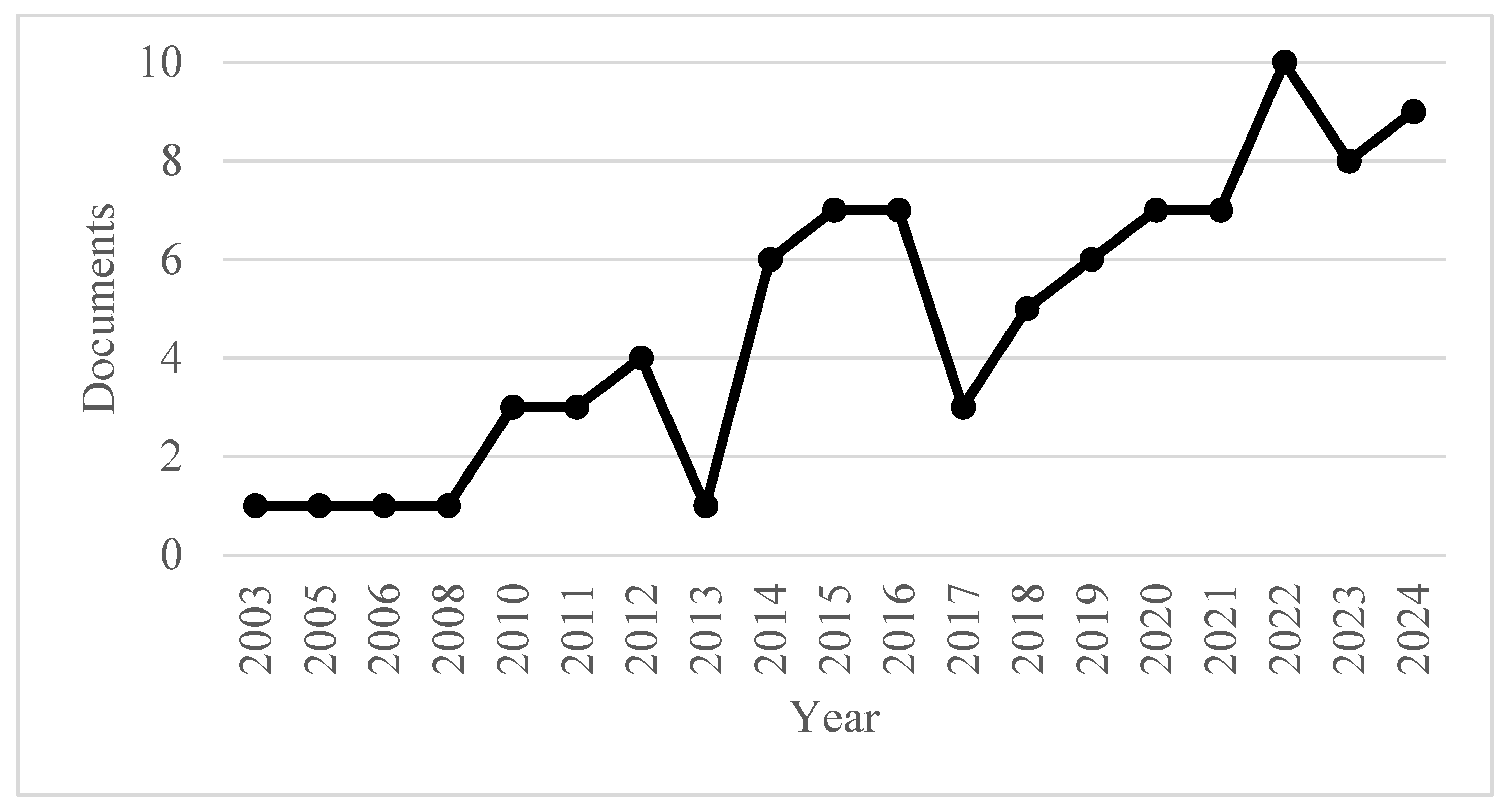

Enhancing Business Higher Education Through Simula-tion-Based Learning, Problem-Based Learning, and Challenge-Based Learning Peer-Reviewed Articles up to May 2024. The year 2022 had the highest number of peer-reviewed publications, reaching 10.

Figure 2 summarizes the peer-reviewed literature published up to May 2024.

The publications were sorted out as follows: International Journal Of Management Education (4); International Journal Of Innovation And Learning (4); Education And Training (4); International Journal Of Management In Education (3); with 2 (Proceedings Of The European Conference On Innovation And Entrepreneurship Ecie; Journal Of Work Applied Management; Journal Of Professional Issues In Engineering Education And Practice; Journal Of Hospitality Leisure Sport And Tourism Education; Journal Of Global Business And Technology; International Journal Of Learning And Change; International Journal Of Human Capital And Information Technology Professionals; Innovar; Imeti 2010 3rd International Multi Conference On Engineering And Technological Innovation Proceedings), and the remaining publications with 1 document.

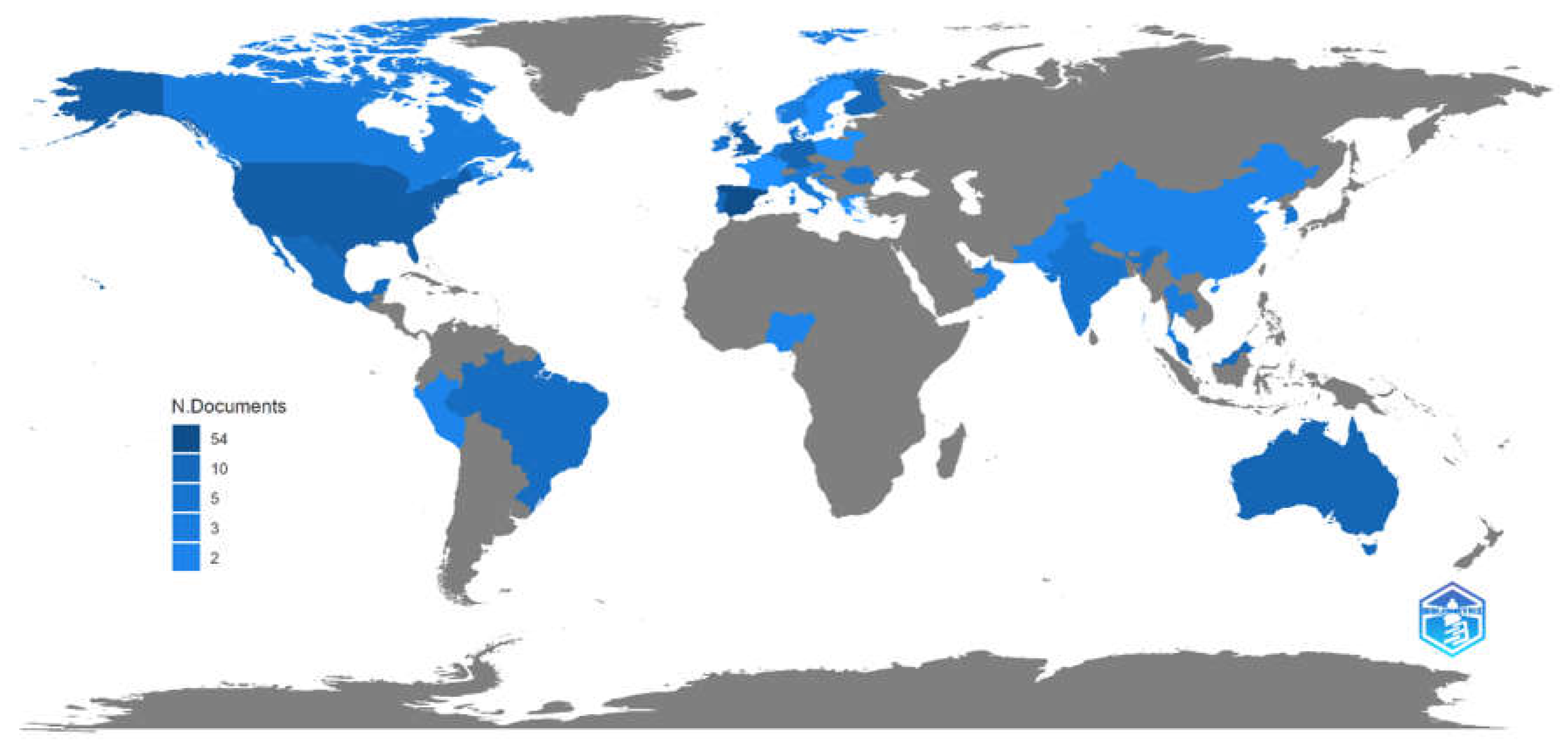

Similarly,

Figure 3 illustrates the regions with the most significant literature contributions on the topic. SPAIN, the USA, Canada, and UK stand out with the highest levels of scientific output in related fields, among other countries publishing on the subject.

In

Table 2 we analyze the Scimago Journal & Country Rank (SJR), the best quartile, and the H index by Technological Forecasting And Social Change with 3,120 (SJR), Q1, and H index 179. There is a total of 13 publications in Q1, 12 publications in Q2, 12 publications Q3, and 6 publications in Q4. Publications from best quartile Q1 represent 19% of the 70 publications titles; best quartile Q2 represents 17%, best Q3 represents 17% and best Q4 represents 9% of each of the titles of 70 publications.

Finally, 27 publications without indexing data represent 39% of publications. As shown in

Table 2, the significant majority of publications do have quartile Q1..

The subject areas covered by the 89 scientific and/or academic documents were: Limited to Business, Management and Accounting (90); Social Sciences (55); engineering (12); Economics, Econometrics and Finance (12); Decision Sciences (8); Computer Science (7); Psychology (6); Medicine (3); Arts and Humanities (2); Physics and Astronomy (1); Nursing (1); Mathematics (1); Environmental Science (1).

The most cited article was “The effectiveness of problem-based learning in technical and vocational education in Malaysia”, with 109 published citations Education and Training 0,760 (SJR), the best quartile (Q1) and with H index (85), in this paper is to examine the impact of the use of problem-based learning with engineering students at a technical university in Malaysia.

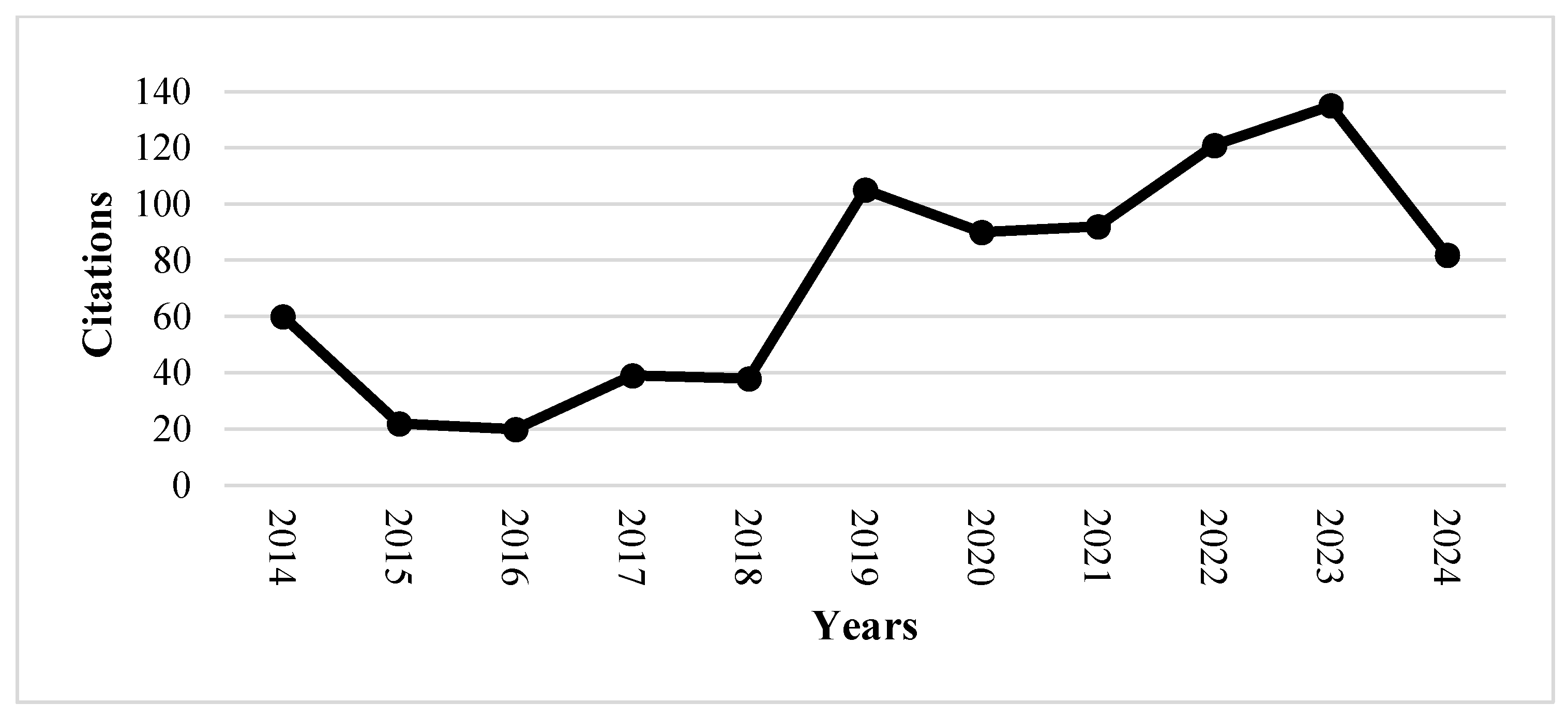

In

Figure 4 we can analyze citation changes for documents published until May 2024. The period 2014-2024 shows a positive net growth in citations with an R2 of 59%, reaching 804 citations in May 2024.

Citations of all scientific and/or academic documents from the period ≤2014 to until May 2024, with a total of 804 citations, of the 89 documents 23 were not cited. The self-citation of documents in the period ≤2014 to May 2024 was self-cited 714 times.

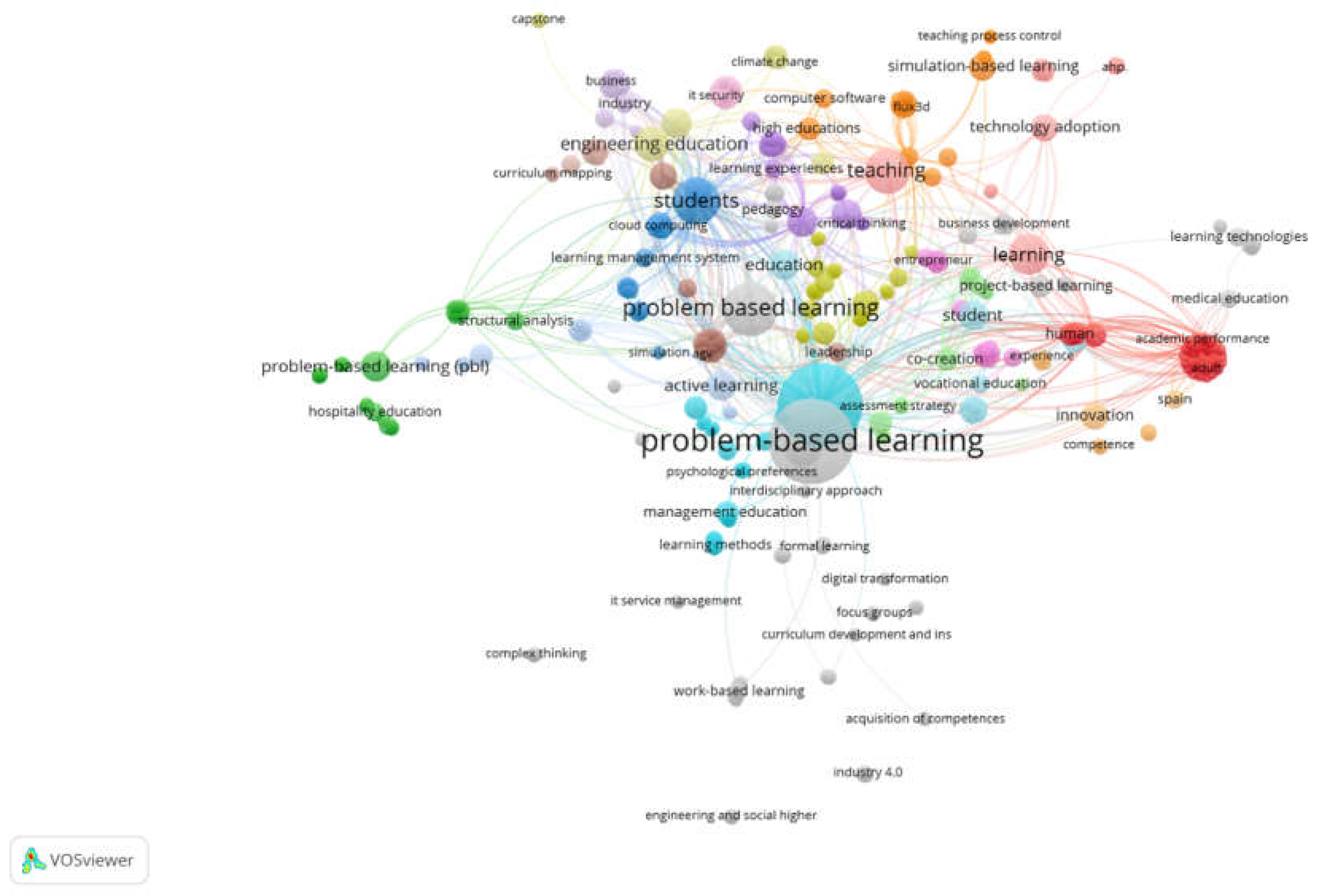

The bibliometric analysis aimed to uncover metrics that reveal patterns and developments in scientific or academic content within documents, focusing on principal keywords (

Figure 5). This visualization displays most network nodes, where the size of each node represents the frequency of the associated keyword, indicating how often the keyword appears. Furthermore, the connections between nodes indicate keyword co-occurrences, showing which keywords appear together. The thickness of these links highlights the frequency of these co-occurrences, essentially illustrating how often the keywords are found together.

In these diagrams, the size of each node reflects the frequency of its associated keyword, while the thickness of the links between nodes indicates how often these keywords co-occur. Different colors represent various thematic clusters. Nodes illustrate the range of topics within a theme, and the links demonstrate the relationships among these topics within the same thematic group.

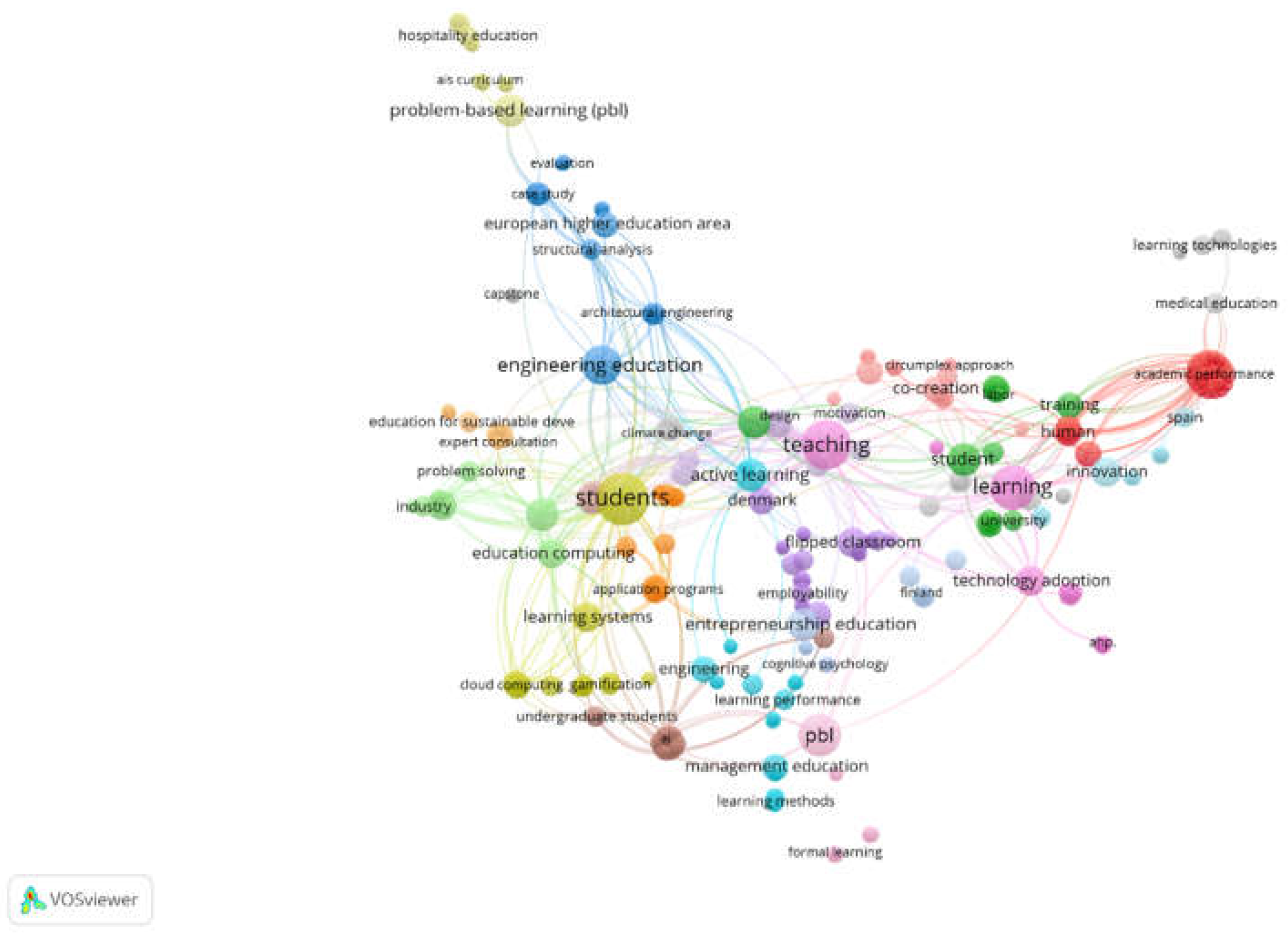

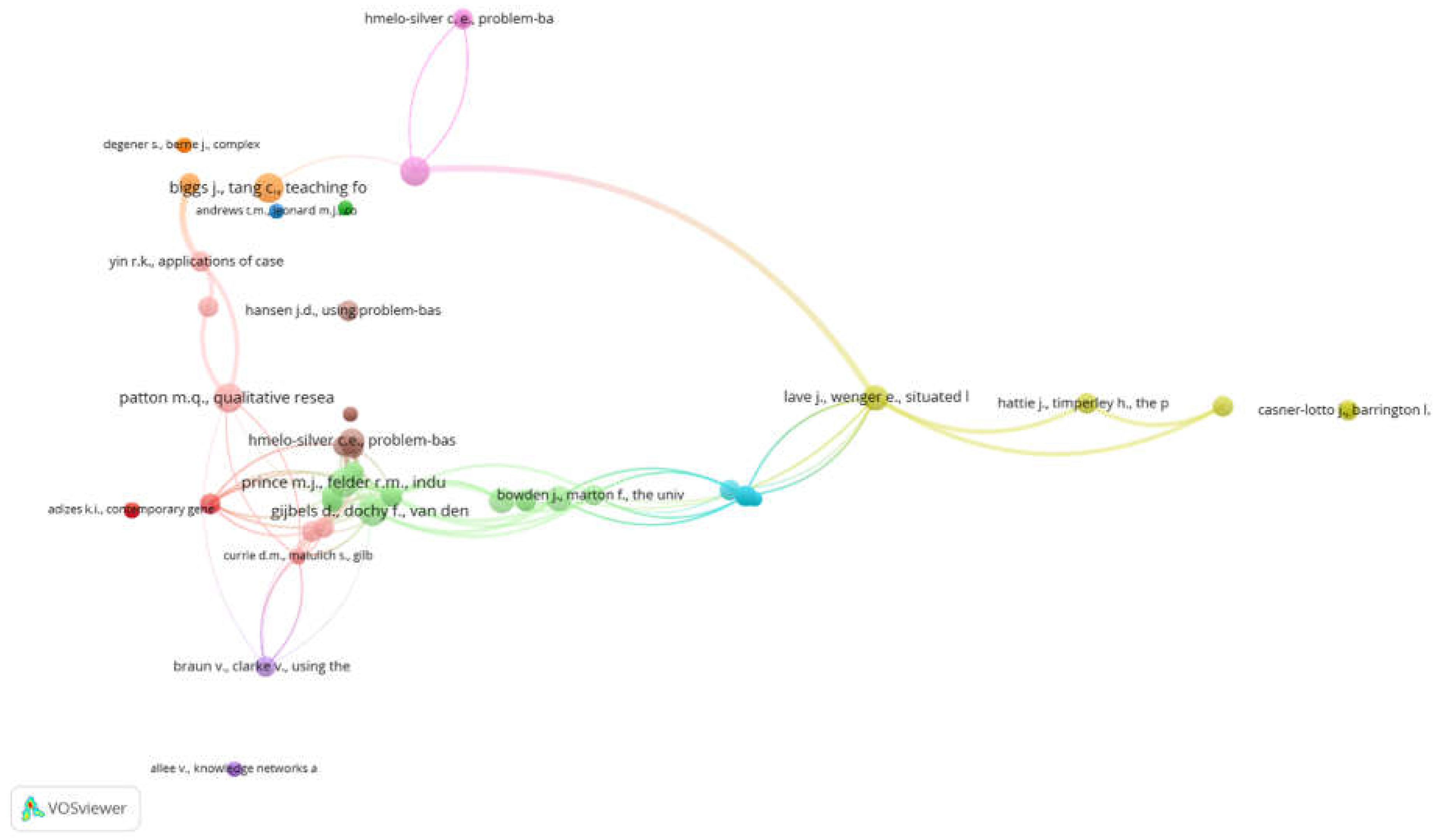

The results were obtained using VOSviewer, a scientific software designed to analyze key search terms such as “Higher Education, Simulation-Based Learning, Problem-Based Learning, and Challenge-Based Learning.” The study focused on scientific and academic documents related to these topics.

Figure 6 showcases the connected keywords, illustrating the network of keywords that co-occur in each scientific article. This analysis helps identify the subjects researchers have investigated and highlights emerging trends for future studies.

Lastly,

Figure 7 presents an extensive bibliographic coupling based on document analysis, allowing for interactive exploration of the co-citation network. This feature enables users to navigate through the network and uncover patterns within “Higher Education, Simulation-Based Learning, Problem-Based Learning, and Challenge-Based Learning” across different authors.

In summary, the chosen methodology ensured precision and provided comprehensive data for future researchers to build upon this review. By addressing key issues, the methodology enhanced coherence and improved the overall validity and reliability of the findings. We adhered to established guidelines for systematic reviews and meta-analyses, achieving a high methodological standard. These aspects will be discussed in further detail below.

4. Theoretical Perspectives

Business higher education has increasingly embraced innovative pedagogical approaches to enhance student learning and engagement in recent years. Among these, simulation-based learning (SBL), problem-based learning (PBL), and challenge-based learning (CBL) have gained significant traction. These methodologies share a common goal, which is to bridge the gap between theoretical knowledge and practical application, thereby preparing students for the complexities of the modern business environment [

7,

8,

9]. They foster critical thinking, collaboration, and real-world problem-solving skills to cultivate a more interactive educational experience. Higher education institutions recognize the importance of actively engaging students in their learning processes to develop competencies essential for their future careers. Therefore, adopting these strategies reflects a broader shift towards experiential learning.

4.1. Overview of Key Concepts

4.1.1. Simulation-Based Learning (SBL)

Simulation-based learning (SBL) is an educational approach that uses interactive, often technology-driven simulations to replicate real-world scenarios within a controlled environment. This method allows students to engage in hands-on, experiential learning without the risks associated with real-life practice. Lu et al. [

10] explain that although different institutions and learning settings implement varying SBL frameworks, they often share common core activities for inclusion.

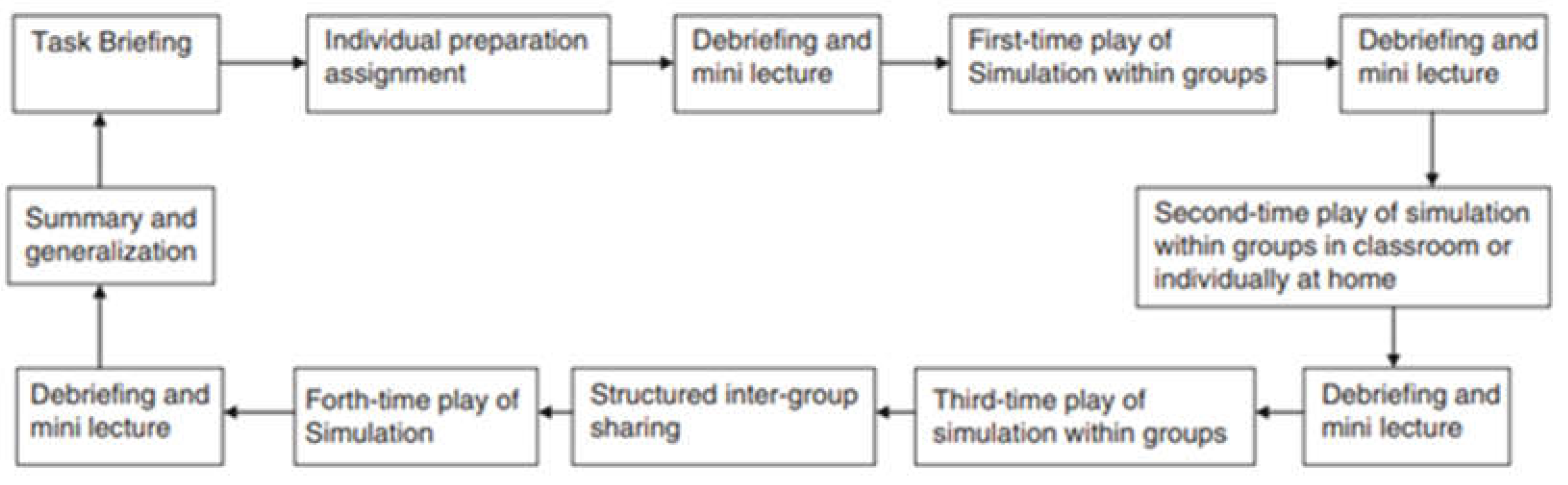

Figure 8 shows a sample framework illustrating the SBL instructional mode and sequence of activities. According to Asadi et al. [

11], SBL requires students to do more than store information; they need to examine how concepts learned in class apply to specific situations. In addition, Bhaskar et al. [

12] explained that students are rarely exposed to similar events twice in well-designed simulation programs. As a result, the exposure to varying situations encourages students to adopt a problem-solving mentality and rethink their psychological processes and strategic decisions.

In business education, SBL often uses software programs that mimic market conditions, financial systems, or managerial decision-making processes. These simulations provide a safe space for students to experiment with different strategies, analyze outcomes, and understand the complexities of business operations [

13,

14]. Engaging in these simulated environments enables students to develop critical skills such as strategic thinking, problem-solving, and decision-making [

15]. In addition, SBL can foster collaborative learning, as students often work in teams to navigate simulated challenges [

16,

17]. This enhances their communication and teamwork skills. The immersive nature of SBL makes it a powerful tool for bridging theoretical knowledge and practical application, providing students with a deeper understanding of business concepts and their real-world implications.

4.1.2. Problem-Based Learning (PBL)

Problem-based learning (PBL) is an instructional method where students learn by actively engaging in real-world and complex problems. This student-centered approach encourages learners to take responsibility for their education by identifying what they need to know to solve problems. Celinšek and Markič [

18] describe PBL as “the most significant innovation in education for the professions.” This is because PBL takes a constructivist approach to teaching and learning, which infers that knowledge cannot be simply transferred from one student to another. Instead, it hypothesizes that individuals gain knowledge through experience. Similarly, Bridges et al. [

19] argue that integrating constructivist views in PBL encourages students to collaborate to co-create knowledge. As a result, PBL promotes collaboration and teamwork, where students work together to solve problems and make strategic decisions.

Implementing PBL in higher business education typically involves presenting students with a business-related problem without a straightforward solution. Students must then collaborate on research, apply relevant knowledge, and develop viable solutions [

20]. This process often involves multiple steps, including identifying the problem, gathering information, formulating hypotheses, and testing these hypotheses through application. PBL emphasizes the development of critical thinking, research skills, and self-directed learning [

21,

22]. It also enhances students’ ability to apply theoretical concepts to practical situations. This creates a deeper understanding of the subject matter [

23]. Furthermore, PBL promotes soft skills such as teamwork, communication, and leadership, as students must work together to solve problems and present their findings [

24]. The focus on real-world issues in PBL prepares students for the dynamic and often ambiguous nature of the business world.

4.1.3. Challenge-Based Learning (CBL)

Challenge-based learning (CBL) is an educational approach involving students identifying and addressing real-world challenges. Unlike traditional problem-solving methods, CBL starts with a broad challenge, which students must narrow down to specific issues they can address [

25]. This method is highly relevant in business education, where students are often tasked with tackling complex, multifaceted problems that do not have clear-cut solutions. In CBL, students typically work in teams to research the challenge, develop a deep understanding of the context, and devise innovative solutions [

26,

27]. This approach encourages active learning and engagement. In this regard, students are motivated by the relevance and impact of the challenges they are addressing. CBL emphasizes the importance of inquiry, critical thinking, and iterative problem-solving. It also integrates technology and interdisciplinary perspectives, reflecting the interconnected nature of modern business issues [

28]. Engaging students with real-world challenges enables them to develop their business skills and knowledge and improves their ability to think creatively, work collaboratively, and drive positive change. This experiential learning model prepares students for the complexities of their future careers and equips them with the skills needed to navigate and address the ever-evolving challenges of the business world.

4.2. Benefits of CBL/PBL/SBL in Business Higher Education

CBL, PBL, and SBL approaches promote student-centered learning, where students actively participate in their learning journey. Unlike conventional teaching methods, the innovative approaches encourage instructors to engage students in real-life challenges. As a result, they gain hands-on experience and develop knowledge and skills to solve potential workplace problems and make strategic decisions. Consequently, these methodologies are associated with multiple benefits, including.

4.2.1. Enhancing Students’ Critical Thinking and Problem-Solving Skills

CBL, PBL, and SBL immerse learners in real-world scenarios where they encounter complex problems typical of business environments. This engagement with practical challenges encourages them to analyze issues from multiple perspectives, apply theoretical knowledge to practical situations, and develop innovative solutions [

28]. This process deepens their understanding of theoretical concepts and improves their ability to think critically under pressure and navigate uncertainties. In addition, these learning approaches promote active engagement and collaborative learning among students [

29,

30]. Through group discussions, debates, and collaborative problem-solving exercises, learners are encouraged to exchange ideas, challenge assumptions, and collectively arrive at solutions. This cooperative aspect mirrors teamwork dynamics in professional settings and enhances students’ communication and interpersonal skills. Finally, PBL, CBL, and SBL encourage self-directed learning and autonomy [

31,

32]. Students take ownership of their learning journey by actively seeking information, identifying gaps in their knowledge, and setting goals for improvement [

33]. This autonomy fosters a sense of responsibility and self-motivation. These are essential attributes for success in dynamic business environments where continuous learning and adaptation are crucial.

4.2.2. Improved Decision-Making Skills

These methodologies expose learners to diverse business scenarios where they must make informed decisions based on available data, analysis, and critical evaluation. They engage with realistic case studies or simulations that help them learn to assess risks, evaluate consequences, and weigh alternative courses of action [

34,

35]. These practices mirror the complexity of decision-making processes in actual business settings. In addition, SBL, CBL, and PBL emphasize the importance of evidence-based decision-making. Students are encouraged to gather relevant information, analyze data effectively, and apply theoretical frameworks to support their decisions [

36]. This process enhances their ability to make sound judgments under uncertainty and reinforces the importance of considering multiple perspectives and ethical implications in decision-making [

37]. Furthermore, these teaching approaches foster reflective practice among students. Learners are encouraged to evaluate the outcomes of their decisions critically through debriefings, feedback sessions, and post-analysis reflections [

38]. This reflective approach promotes continuous improvement and the development of adaptive decision-making strategies, preparing students to navigate real-world issues.

4.2.3. Real-World Application

SBL, CBL, and PBL allow students to bridge theoretical knowledge with practical experience. These methodologies immerse learners in authentic business scenarios, simulations, or case studies that reflect the complexities and challenges encountered in actual professional environments [

39]. As a result, students gain firsthand experience in applying theoretical concepts to solve practical challenges. This hands-on approach allows them to develop a deeper understanding of how theoretical knowledge translates into actionable strategies and decisions within various business contexts [

40,

41]. In addition, students learn to navigate uncertainties, manage risks, and adapt their approaches based on evolving circumstances comparable to actual business operations. Moreover, Spalek [

42] explains that these learning approaches promote the integration of interdisciplinary knowledge and skills. Students are encouraged to draw upon insights from diverse disciplines such as finance, marketing, operations, and strategic management to formulate comprehensive solutions to complex problems.

PBL, CBL, and SBL also facilitate engagement with industry professionals and practitioners. Students gain exposure to current trends, best practices, and real-world business challenges through guest lectures, industry partnerships, or collaborative projects [

43,

44]. This interaction enriches their learning experience and provides valuable networking opportunities and insights into potential career paths within the business sector.

4.2.4. Improved Student Engagement and Motivation

PBL, SBL, and CBL enhance student engagement and motivation through interactive and immersive learning experiences. According to Crovini [

45], these methodologies depart from traditional lecture-based formats by actively involving students in solving real-world problems, analyzing case studies, or participating in simulated business scenarios. One key factor contributing to improved engagement is the relevance of the learning content [

46]. Instructors in these programs present challenges that mimic actual business dilemmas, thereby capturing students’ interest. This relevance sparks curiosity and encourages students to actively participate in discussions, debates, and collaborative activities to find innovative solutions.

These learning approaches promote active learning environments where students take on active roles as problem-solvers and decision-makers. Instead of passively receiving information, students are encouraged to explore, question, and apply their knowledge meaningfully [

47]. This active engagement deepens their understanding of course material, cultivating critical thinking skills and a sense of ownership over their learning journey. PBL, CBL, and SBL create a sense of accomplishment and satisfaction among students [

48]. As they successfully navigate complex challenges and achieve meaningful outcomes, students experience a tangible sense of progress and achievement [

49]. This positive reinforcement motivates them to persist in their studies, take on greater challenges, and continuously strive for improvement. Additionally, these methodologies support personalized learning experiences tailored to students’ interests, strengths, and career aspirations [

50,

51]. They allow flexibility in approach and encourage autonomy in learning, thereby empowering students to pursue topics of personal relevance and develop skills that align with their professional goals.

4.2.5. Improved Academic Performance

PBL, SBL, and CBL are associated with improved academic performance due to several key factors that enhance learning outcomes. For instance, Song et al. [

47] indicate that these methodologies facilitate deeper engagement with course material. Presenting real-world challenges and scenarios in PBL, CBL, and SBL encourages students to apply theoretical concepts in practical contexts [

52,

53]. This active application of knowledge enhances understanding and strengthens retention and mastery of course content. In addition, these innovative approaches challenge students to think critically and solve problems [

54]. This cognitive engagement stimulates intellectual growth and helps students develop higher-order thinking skills essential for academic success. Students in these courses often work in teams to tackle challenges or analyze case studies [

55]. Consequently, they benefit from peer-to-peer learning, constructive feedback, and diverse perspectives. This collaborative environment nurtures communication skills, teamwork abilities, and mutual support among students, all contributing to improved academic performance.

PBL, CBL, and SBL emphasize active participation and student-centered learning. Instead of passive learning through lectures, students actively engage in discussions, debates, and hands-on activities that encourage curiosity, exploration, and self-directed inquiry [

56]. This active learning approach motivates them and contributes to a deeper understanding of concepts, ultimately promoting academic excellence [

57]. Furthermore, these methodologies often incorporate assessments that mirror real-world expectations, such as presentations, case analyses, or project reports [

58]. Aligning assessments with practical skills and competencies valued in the business sector helps prepare students for academic success and future career readiness.

4.2.6. Collaboration and Teamwork

All three methodologies emphasize collaborative learning experiences where students work in teams to analyze complex problems, devise solutions, and make decisions. They participate in group discussions, debates, and joint problem-solving activities. This grouping helps them learn to appreciate diverse perspectives, leverage collective strengths, and navigate interpersonal dynamics effectively [

59,

60]. During these activities, students practice articulating ideas, listening actively to peers, and presenting their findings cohesively. This communication practice enhances clarity in expressing thoughts and ideas and fosters a supportive environment where collaboration flourishes [

43]. In addition, these learning approaches cultivate leadership skills within team contexts. Students collaborating on projects or simulations can take on leadership roles, delegate tasks, and guide team efforts towards achieving common goals [

61,

62]. This experience helps develop leadership qualities such as decision-making, problem-solving, and conflict resolution, which are vital for effective teamwork in professional settings. Finally, PBL, CBL, and SBL encourage accountability and shared responsibility among team members. Students work towards shared objectives and evaluate each other’s contributions, thereby learning to value accountability, trust, and mutual respect within teams.

4.2.7. Lifelong Learning and Adaptability

SBL, CBL, and PBL emphasize learning through practical experience and application. This experiential learning approach instils a curiosity-driven mindset, encouraging students to seek continuous learning opportunities and stay updated with industry developments throughout their careers [

63]. In addition, these approaches promote adaptability by challenging students to respond to dynamic and unpredictable situations. For instance, students learn to assess new information, adjust strategies, and innovate solutions in real time through simulations of business challenges or case studies with varying contexts [

64,

65]. This adaptive mindset prepares them to thrive in environments characterized by rapid change and uncertainty. These are crucial qualities for career longevity and professional growth [

66]. Furthermore, Scholkmann and Küng [

67] indicate that practices such as debriefings, self-assessments, and critical reflections on learning experiences allow students to develop metacognitive skills and self-awareness. This introspective approach encourages them to identify strengths, areas for improvement, and personal learning goals, fostering a commitment to lifelong learning and professional development.

4.2.8. Enhanced Entrepreneurship Skills

SBL, PBL, and CBL approaches improve entrepreneurship skills among students through immersive, practical learning experiences. These methodologies support entrepreneurship skills by supporting creativity and innovation [

68]. Through assessing and solving real-world problems or developing business case studies, students are encouraged to think outside the box, explore unconventional solutions, and envision new opportunities [

69,

70]. This creative mindset is fundamental to entrepreneurial success. It enables students to identify gaps in the market, conceptualize innovative products or services, and formulate viable business strategies [

71]. Moreover, PBL, CBL, and SBL emphasize hands-on learning and practical application of entrepreneurial concepts. Students are engaged in business simulations, creating business plans, or analyzing entrepreneurial case studies. These activities help them gain valuable experience in assessing market trends, identifying potential risks, and making informed decisions.

Furthermore, these learning approaches promote risk-taking and resilience. Students are exposed to scenarios where they must evaluate risks, navigate uncertainties, and adapt strategies based on changing market dynamics [

72]. This experiential learning builds confidence in handling challenges and cultivates resilience. As a result, students learn from setbacks and persevere in pursuing entrepreneurial goals [

73,

74]. Additionally, PBL, CBL, and SBL encourage the development of entrepreneurial mindsets. Students learn to identify opportunities, assess feasibility, and leverage resources effectively [

75]. They also gain exposure to entrepreneurial practices such as business modeling, customer validation, and financial planning, preparing them to launch and manage successful ventures in a competitive business environment.

4.3. Challenges of CBL/PBL/SBL in Business Education

Despite the potential benefits of CBL, PBL, and SBL teaching and learning methods, various challenges hinder their optimal implementation. For instance, students’ learning preferences may impact their willingness to participate in group work [

76]. This can significantly affect the instructors’ ability to provide personalized instructions. In addition, some students and instructors may resist the new changes towards these innovative instructional methods. Other considerable challenges identified include.

4.3.1. Resource and Time Intensive

CBL, PBL, and SBL may require additional resources to implement. For instance, these approaches often involve integrating technology and specialized software platforms to create realistic simulations or deliver interactive learning experiences [

77]. Ensuring access to these technological resources and providing adequate training for faculty and students can be resource-intensive. In addition, developing and delivering case studies, problems, and scenarios require substantial time and effort from instructors [

76,

78]. Unlike traditional lecture-based teaching, these methods necessitate extensive preparation, including creating detailed and realistic scenarios, coordinating group activities, and providing ongoing feedback and support [

79]. Students must also invest considerable time in researching, analyzing, and discussing these complex problems, which can be demanding given their other academic and personal commitments [

80]. This high demand for time and resources can be a significant barrier to the widespread adoption of these approaches, particularly in institutions with limited funding or large class sizes.

4.3.2. Assessment and Evaluation Difficulties

Another challenge associated with CBL, PBL, and SBL is the difficulty of assessing and evaluating student performance. Traditional assessment methods, such as exams and quizzes, may not adequately capture the learning outcomes of these active learning approaches [

81]. Assessing students’ ability to analyze complex problems, develop innovative solutions, and work effectively in teams requires more nuanced and comprehensive evaluation techniques. This can include the use of rubrics, peer assessments, and reflective journals, all of which require careful design and implementation [

82,

83]. Developing reliable and valid assessment tools that accurately reflecting students’ learning and progress is complex and time-consuming [

84]. Furthermore, ensuring fairness and consistency in assessment across different groups and instructors can be challenging, particularly in large classes or diverse educational settings.

4.3.3. Instructor Preparedness and Training

Implementing PBL, CBL, and SBL effectively requires significant instructor preparedness and ongoing training. For instance, faculty members must possess specialized skills and knowledge to design and facilitate these active learning methodologies [

31,

85]. They must be proficient in creating authentic case studies, developing realistic simulations, and structuring learning environments that promote critical thinking and collaboration [

69]. This preparation demands time and resources for curriculum development. It also necessitates additional training or professional development opportunities for educators to enhance their instructional competencies. In addition, instructors require training to use technological tools and platforms that support PBL, CBL, and SBL [

86]. These methodologies often use interactive simulations, online learning platforms, or multimedia resources to create immersive learning experiences [

87]. Faculty members must have the skills to integrate technology into their teaching practices, troubleshoot technical issues, and leverage digital tools to enhance student engagement and learning outcomes.

Adapting to the facilitation role in PBL, CBL, and SBL environments can be challenging for educators accustomed to traditional lecture-based teaching methods. Facilitating group discussions, guiding student-led inquiry, and providing constructive feedback requires a shift in instructional approach and pedagogical mindset [

69,

88]. Training and support in facilitation techniques, effective communication strategies, and managing group dynamics are essential for instructors to create a productive and inclusive learning environment. Besides, maintaining instructor enthusiasm and commitment to these active learning methodologies over time can be demanding [

89]. Faculty members may face workload pressures, competing priorities, or resistance to change within academic institutions. Institutional support through recognition of teaching efforts, provision of professional development resources, and a culture of innovation in teaching can mitigate these challenges and sustain instructor motivation.

4.3.4. Student Resistance and Adjustment

Student resistance to active learning approaches that deviate from traditional lecture-based formats can be a significant challenge. Some students may prefer passive learning or feel uncomfortable with the increased responsibility for self-directed learning, collaborative teamwork, and problem-solving [

90]. In addition, adjusting to the collaborative nature of PBL, CBL, and SBL environments can be challenging for students accustomed to individualized learning experiences. Working effectively in teams, sharing responsibilities, and navigating group dynamics requires interpersonal skills, communication abilities, and a willingness to compromise [

91]. Educators play a crucial role in facilitating team-building activities, setting clear expectations for collaboration, and providing guidance on conflict resolution strategies to help students adjust and thrive in collaborative learning settings.

The complexity and ambiguity inherent in PBL, CBL, and SBL activities can challenge students. These methodologies often involve handling real-world problems or ambiguous case scenarios with no single correct answer. Students must learn to navigate uncertainties, manage ambiguity, and persevere through iterative problem-solving processes [

92]. Providing ongoing feedback and opportunities for reflection can support students in developing resilience and adaptive problem-solving skills necessary for success in dynamic business environments. Moreover, balancing the demands of PBL, CBL, and SBL activities with other academic commitments can overwhelm students [

73,

93]. These methodologies often require substantial time and effort outside of class to conduct research, collaborate with peers, and prepare presentations or reports. Educators can support students by aligning workload expectations with learning objectives, offering flexible deadlines, and promoting time management strategies to help students effectively manage their academic responsibilities.

4.3.5. Scalability and Implementation

Scalability is a significant challenge in SBL, CBL, and PBL. This issue is prevalent in large class sizes or across multiple courses within a program. Implementing PBL, CBL, and SBL requires careful consideration of resource allocation, faculty workload, and logistical support to ensure consistency and quality of learning experiences [

94,

95]. Frezzo et al. [

96] indicate that scaling these methodologies effectively may necessitate additional investments in technological infrastructure, professional development for faculty, and instructional design expertise to maintain educational standards and meet learning outcomes across various settings. Moreover, adapting PBL, CBL, and SBL to different academic environments and disciplines can be complex [

97]. These methodologies often require customization to align with specific programmatic goals, curriculum requirements, and disciplinary contexts. Faculty members may need support tailoring case studies, simulations, or learning activities that resonate with students’ backgrounds, interests, and career aspirations while addressing discipline-specific content and learning objectives.

4.4. Implications of CBL/PBL/SBL in Higher Business Education

In higher business education, CBL, PBL, and SBL can have numerous implications for key stakeholders and processes. For example, higher education institutions must support professional development opportunities to ensure instructors have the knowledge and skills to implement these teaching and learning approaches. This section synthesizes data on other implications of CBL, SBL, and PBL on higher business education.

4.4.1. Curriculum Development and Innovation

Adopting CBL, PBL, and SBL in business education has significant implications for curriculum development and innovation. These approaches necessitate a redesign of traditional curricula to incorporate active learning elements [

32]. This shift encourages the development of innovative teaching strategies and materials that enhance student engagement and learning outcomes [

98]. Institutions must be willing to invest in curriculum development to integrate these methods into their programs fully. This involves rethinking course structures, learning objectives, and assessment methods to align with active learning principles [

99]. Embracing these changes enables institutions to create more dynamic and effective educational experiences that better prepare students for the challenges of the business world.

4.4.2. Professional Development for Instructors

Professional development for instructors is another crucial implication of adopting CBL, PBL, and SBL. To effectively implement these approaches, instructors need ongoing training and support. This professional development helps them develop new teaching competencies and skills, ensuring they can facilitate active learning effectively [

100]. Consequently, institutions must prioritize and support continuous professional development to maintain high standards of teaching and learning. This includes offering workshops, seminars, and other training opportunities that focus on the design and implementation of CBL, PBL, and SBL [

96]. Institutions that invest in the professional growth of their faculty ensure that instructors are well-equipped to deliver high-quality education that meets the needs of their students.

4.4.3. Institutional Support and Resources

Institutional support and resources are critical for successfully implementing CBL, PBL, and SBL in business education. These pedagogical approaches require significant investments in various resources to ensure their effectiveness and sustainability (Bachiller & Bachiller, 2015). For example, financial resources are needed to develop and acquire case studies, simulations, and other learning materials that facilitate active learning. In addition, technological resources, such as classroom technology and online platforms, are essential for delivering and managing these interactive learning experiences (Yeo, 2005). Additionally, infrastructure support is necessary to create conducive learning environments that support collaborative work and group activities.

Administrative support is equally vital to promote and sustain these pedagogical changes. For this reason, institutional leaders must champion the adoption of CBL, PBL, and SBL, advocating for their benefits and providing the necessary guidance and policies to support their implementation [

89]. This includes allocating dedicated funding for professional development programs for instructors, ensuring equitable access to resources across departments and campuses, and promoting a culture of innovation and continuous improvement in teaching and learning practices [

38]. Prioritizing institutional support and resources can enable institutions to create robust frameworks that enhance the quality and impact of CBL, PBL, and SBL in business education.

4.4.4. Research and Continuous Improvement

Adopting CBL, PBL, and SBL in business education also encourages research and continuous improvement in teaching practices. These pedagogical approaches provide fertile ground for educational research to understand their effectiveness, identify best practices, and address emerging challenges. Researchers explore various aspects of CBL, PBL, and SBL, such as their impact on student learning outcomes, the effectiveness of different implementation strategies, and the factors contributing to their success or failure in other contexts. Conducting rigorous research allows educators and institutions to enhance their understanding of how these methods influence student engagement, learning retention, and overall educational outcomes. This evidence-based approach informs the refinement and adaptation of teaching practices, ensuring that CBL, PBL, and SBL evolve to meet the changing needs of students and the business industry. Research findings contribute to developing evidence-based guidelines and recommendations for instructors and institutions seeking to implement these pedagogical approaches effectively.

5. Conclusions

CBL, SBL, and PBL are transformative methodologies in higher business education that emphasize applying theoretical knowledge to real-world scenarios. These approaches enhance students’ critical thinking, problem-solving, and decision-making skills by immersing them in practical, hands-on learning experiences. Students develop a deeper understanding of business concepts and their applications by handling authentic business challenges through PBL, analyzing complex cases in CBL, and engaging in realistic simulations via SBL. These approaches support essential skills such as teamwork, communication, and adaptability, preparing students for the contemporary work environment. In addition, PBL, CBL, and SBL promote lifelong learning and innovation, equipping students with the ability to continuously update their skills and knowledge in response to evolving industry demands. The interdisciplinary focus of these approaches ensures that graduates are well-prepared to address modern business challenges and contribute to organizational success, making them invaluable assets to any organization.

However, implementing PBL, CBL, and SBL in business education also presents several challenges and significant implications for educational institutions. These innovative teaching strategies are resource and time-intensive. They require substantial investment in faculty training, technological infrastructure, and curriculum development. Assessing student performance in these active learning environments can be complex, necessitating robust, multifaceted evaluation strategies that accurately measure practical skills and competencies development. Both students and instructors may need to adjust to the shift from traditional, lecture-based learning to more interactive and collaborative approaches. This transition can initially be met with resistance. Institutional support is critical for overcoming these challenges. In this case, educational facilities should provide financial investment, facilitate policy development, and support a culture of continuous improvement and innovation. Addressing these challenges and leveraging the benefits of active learning can improve business education quality and better prepare students for the global marketplace. The successful implementation of PBL, CBL, and SBL requires comprehensive planning, ongoing professional development, and a commitment to educational excellence. These practices ultimately improve the learning experience and equip graduates to excel in their professional careers.

Simulation-based learning is rooted in experiential learning theory, which posits that learning is a process whereby knowledge is created through the transformation of experience. Simulations provide a risk-free environment where learners can experiment with business strategies and decisions: (i) Platforms allow students to manage virtual companies, make strategic decisions, and see the consequences of their actions in a simulated market; (ii) Students can take on roles within a simulated company (e.g., CEO, marketing manager) to understand different perspectives and responsibilities; (iii) Presenting students with various business scenarios to analyze and make decisions, which helps in developing critical thinking and decision-making skills. Enhances decision-making and strategic thinking skills. Provides hands-on experience without real-world risks and encourages teamwork and communication.

Problem-based learning is grounded in constructivist theories of learning, which suggest that learners construct knowledge through problem-solving experiences and social interaction. PBL emphasizes student-centered learning and the development of problem-solving skills: (i) Students are given complex, real-world business problems to solve, which helps in integrating theoretical knowledge with practical application; (ii) Problems often require knowledge from various business disciplines (finance, marketing, operations), fostering a holistic understanding; (iii) Instructors act as facilitators, guiding students through the problem-solving process rather than providing direct instruction. Develops critical thinking and analytical skills and encourages self-directed learning and intrinsic motivation.

Challenge-based learning is influenced by theories of experiential learning and inquiry-based learning, emphasizing active participation and real-world engagement. It aims to tackle real societal and business challenges through collaborative efforts: (i) Collaboration with businesses to present students with current challenges facing the industry; (ii) Students work on long-term projects that address specific challenges, culminating in practical solutions; (iii) Students present their findings and solutions to stakeholders, which can include business leaders, faculty, and peers.

Enhances problem-solving and innovation skills and provides real-world experience and professional networking opportunities.

Encourages collaboration and communication across diverse teams.

Combining SBL, PBL, and CBL can create a comprehensive learning environment that leverages the strengths of each method.

For instance, a course might use simulations to introduce concepts (SBL), follow with problem-based projects to deepen understanding (PBL) and culminate in a challenge-based project with industry partners (CBL). Use a mix of formative and summative assessments, including peer reviews, reflective journals, and presentations.

Simulation-based, problem-based, and challenge-based learning offer robust frameworks for enhancing business higher education. By combining these approaches, educators can create dynamic, engaging, and practical learning experiences that prepare students for the complexities of the modern business world. The integration of theory and practice not only improves academic outcomes but also equips students with the skills and knowledge necessary for professional success.

Future Lines of Investigation in Improving Business Higher Education through SBL, PBL, and CBL: (i) Investigate how AI-driven simulations can provide personalized learning experiences and adaptive challenges based on individual student progress; (ii) Explore the use of VR and AR to create immersive learning environments for SBL, PBL, and CBL, enhancing realism and engagement; (iii) Investigate the dynamics of collaborative learning in team-based projects and simulations, the factors that drive student motivation and engagement in experiential learning environments.

Future research in improving business higher education through simulation-based learning, problem-based learning, and challenge-based learning should focus on leveraging technological advancements, refining pedagogical strategies, fostering industry collaborations, understanding cognitive and social learning processes, ensuring inclusivity and accessibility, and conducting longitudinal studies. These areas of investigation hold the potential to significantly enhance the effectiveness, relevance, and impact of business education, preparing students for the complexities of the modern business world.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.A. and R.R.; methodology, R.A. and R.R.; software, R.A. and R.R.; validation, R.A. and R.R.; formal analysis, R.A. and R.R.; investigation, R.A. and R.R.; resources, R.A. and R.R.; data curation R.A. and R.R.; writing—original draft preparation, R.A. and R.R.; writing—review and editing, R.A. and R.R.; visualization, R.A. and R.R.; supervision, R.R. and R.A.; project administration, R.R. and R.A.; funding acquisition, R.R. and R.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.” Please turn to the CRediT taxonomy for the term explanation. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

Funding

The first author receives financial support from the Research Unit on Governance, Competitiveness and Public Policies (UIDB/04058/2020) + (UIDP/04058/2020), funded by national funds through FCT - Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, and the second author receives financial support from ISEC Lisboa. Both entities provided invaluable support.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to the Editor and the Referees. They offered valuable sug-gestions or improvements. The authors were supported by the GOVCOPP Research Center of the University of Aveiro and ISEC Lisboa that provided invaluable support.

Conflicts of Interest

The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Overview of document citations period ≤2014 to 2024.

Table A1.

Overview of document citations period ≤2014 to 2024.

| Documents |

|

≤2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

2023 |

2024 |

Total |

| Trends and research outcomes of technolo ... |

2023 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

3 |

3 |

| Exploring problem-based learning curricula ... |

2023 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

5 |

7 |

12 |

| Challenge-based learning approach to teac. .. |

2023 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

2 |

2 |

4 |

| Design pedagogy in a time of change: Appl. .. |

2023 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

1 |

| Challenges and opportunities for problem- ... |

2023 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

3 |

3 |

7 |

| lnhibiting factors influencing adoption of si ... |

2023 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

2 |

2 |

| Feed Back as a Teaching Toai: lts lmpact on ... |

2023 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

1 |

| Teaching entrepreneurship to life-science s ... |

2022 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

2 |

5 |

8 |

| Business students’ perspectives on case me ... |

2022 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

3 |

2 |

2 |

7 |

| Simulation-based learning in business and ... |

2022 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

1 |

| The adoption of corporate social responsibi ... |

2022 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

6 |

1 |

8 |

| Challenge-based Learning: How to Support ... |

2022 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

1 |

1 |

3 |

| Bringing social challenges to the classroom ... |

2022 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

1 |

| Engineering Students as Co-creators in an ... |

2021 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

5 |

9 |

6 |

2 |

22 |

| Self-managed and work-based learning: pr ... |

2021 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

6 |

| Towards a responsible entrepreneurship ed ... |

2021 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

3 |

6 |

8 |

12 |

5 |

34 |

| lntegrating Problem-based Learning with 1. .. |

2021 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

3 |

2 |

2 |

7 |

| The logilegolab: A problem-based learning ... |

2021 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

4 |

- |

- |

4 |

| Are we ready for the job market? The role of ... |

2020 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

| Continuous lmprovement Challenges: lmpl. .. |

2020 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

2 |

| A Novel Education Program Using Autono ... |

2020 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

5 |

| Application of narrative theory in project ba ... |

2020 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

3 |

2 |

- |

- |

- |

5 |

| Development of Cloud Learning Managem ... |

2019 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

7 |

| Problem-based learning in the lrish SME w ... |

2019 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

2 |

2 |

4 |

2 |

1 |

11 |

| The effectiveness of problem-based learnin ... |

2019 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

52 |

11 |

8 |

15 |

14 |

9 |

109 |

| Undergraduates’ satisfaction and perceptio ... |

2019 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

8 |

11 |

11 |

20 |

9 |

59 |

| Linking Active Learning and Capstone Proje ... |

2019 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

1 |

| Developing an Effective Model of Students’ ... |

2018 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

1 |

| Sustainable higher education teaching appr ... |

2018 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

1 |

- |

2 |

2 |

- |

5 |

| Developing undergraduate it students’ gen ... |

2018 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

3 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

- |

- |

10 |

| How Simulations of Decision-Making Affec. .. |

2018 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

2 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

2 |

| Aligning teaching methods for learning out ... |

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

3 |

2 |

2 |

6 |

2 |

1 |

16 |

| Teaching environmental sustainability acros ... |

2017 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

3 |

3 |

- |

2 |

2 |

10 |

| Escaping the healthcare leadership cul-de-sac |

2017 |

|

|

1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

2 |

| An empirical investigation on factors affecti ... |

2017 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

| Training students for new jobs: The role of t... |

2016 |

- |

- |

1 |

3 |

5 |

9 |

4 |

7 |

10 |

2 |

- |

41 |

| Students’ acquisition of competences throu ... |

2016 |

- |

- |

- |

3 |

- |

2 |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

6 |

| A professional development framework for ... |

2016 |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

| Fostering Entrepreneurship in Higher Educ ... |

2016 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

1 |

- |

3 |

| Role of universities for inclusive developme ... |

2016 |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

2 |

1 |

1 |

- |

- |

5 |

| The LAB studio model: Enhancing entrepre ... |

2016 |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

1 |

3 |

- |

1 |

- |

3 |

1 |

10 |

| Leveraging education of information techn ... |

2016 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

1 |

- |

3 |

- |

- |

- |

5 |

| Analysis of perception of training in gradua ... |

2015 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

1 |

1 |

- |

- |

3 |

| Change to competence-based education in ... |

2015 |

- |

- |

1 |

3 |

1 |

4 |

3 |

2 |

4 |

4 |

3 |

25 |

| Proposal of a theoretical competence-based ... |

2015 |

- |

- |

3 |

4 |

1 |

- |

3 |

- |

- |

1 |

1 |

13 |

| Designing problem-based curricula: The rol ... |

2015 |

- |

1 |

1 |

1 |

- |

1 |

2 |

- |

1 |

2 |

1 |

10 |

| IMPLEMENTING EDUCATION FOR SUSTA ... |

2015 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

1 |

1 |

- |

2 |

- |

- |

5 |

| Effects of simulation on student satisfactio ... |

2015 |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

2 |

3 |

- |

1 |

1 |

3 |

- |

11 |

| Teaching case of gamification and visual te ... |

2014 |

- |

3 |

2 |

7 |

7 |

8 |

8 |

10 |

9 |

12 |

4 |

70 |

| New teaching methodologies and their imp ... |

2014 |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

3 |

| Project-based learning. Experiences from th ... |

2014 |

- |

1 |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

3 |

| Enhancing the AIS curriculum: lntegration ... |

2014 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

- |

4 |

2 |

3 |

- |

2 |

18 |

| The Rigour of IFRS Education in the USA: A ... |

2014 |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

2 |

- |

- |

3 |

| Redefining the higher education landscape ... |

2013 |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

| Bringing teaching to life: Exploring innovat ... |

2012 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

- |

2 |

2 |

- |

14 |

| Higher education and the development of ... |

2012 |

9 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

3 |

4 |

9 |

3 |

3 |

2 |

3 |

41 |

| Examining competence factors that encour ... |

2012 |

1 |

1 |

4 |

2 |

2 |

7 |

8 |

7 |

4 |

4 |

1 |

41 |

| Features for suitable problems: IT professio ... |

2012 |

1 |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

2 |

| Problem-focused higher education for shap ... |

2011 |

2 |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

3 |

| A new theoretical PBL model for MIS cours ... |

2011 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

2 |

1 |

- |

- |

3 |

| Assessing the instructional effectiveness of ... |

2011 |

7 |

4 |

1 |

6 |

1 |

- |

- |

2 |

- |

1 |

1 |

23 |

| lmpact of information literacy training on a ... |

2010 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

1 |

2 |

| lmplementing problem-based learning in a ... |

2008 |

6 |

- |

1 |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

8 |

| Analysis of education problems at higher e ... |

2006 |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

2 |

| Problem-based learning: Lessons for admin ... |

2005 |

7 |

- |

1 |

1 |

- |

2 |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

12 |

| Do industry collaborative projects enhance ... |

2003 |

23 |

2 |

- |

- |

3 |

2 |

2 |

4 |

2 |

2 |

- |

39 |

| |

Total |

63 |

22 |

20 |

39 |

38 |

105 |

90 |

92 |

121 |

135 |

82 |

22 |

References

- Kasch, J. , Bootsma, M., Schutjens, V., van Dam, F., Kirkels, A., Prins, F.; Rebel, K. Experiences and perspectives regarding challenge-based learning in online sustainability education. Emerald Open Research, 2023, 1(3), 1-20. [CrossRef]

- Hallinger, P.; Wang, R. The evolution of simulation-based learning across the disciplines, 1965–2018: A science map of the literature. Simulation & Gaming, 2020, 51(1), 9-32. [CrossRef]

- Yew, E. H.; Goh, K. Problem-based learning: An overview of its process and impact on learning. Health professions education, 2016, 2(2), 75-79. [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., ...; Moher, D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 2021, 372. [CrossRef]

- Haddaway, N. R. , Page, M. J., Pritchard, C. C.,; McGuinness, L. A. PRISMA 2020: An R package and Shiny app for producing PRISMA 2020-compliant flow diagrams, with interactivity for optimised digital transparency and Open Synthesis. Campbell Systematic Reviews 2022, 18(2), e1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosário, A.T.; Dias, J.C. The New Digital Economy and Sustainability: Challenges and Opportunities. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallinger, P.; Lu, J. Assessing the instructional effectiveness of problem-based management education in Thailand: A longitudinal evaluation. Management Learning, 2011, 42(3), 279–299. [CrossRef]

- Franco, E., González-Peño, A., Trucharte, P.; Martínez-Majolero, V. Challenge- based learning approach to teach sports: Exploring perceptions of teaching styles and motivational experiences among student teachers. Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport and Tourism Education, 2023, 32. [CrossRef]

- Mesquita, A.; Silva, P. Are we ready for the job market? The role of business simulation in the preparation of youngsters. In Handbook of Research on User Experience in Web 2.0 Technologies and Its Impact on Universities and Businesses, 2020, (pp. 19–36). IGI Global. [CrossRef]

- Lu, J., Hallinger, P.; Showanasai, P. Simulation-based learning in management education: A longitudinal quasi-experimental evaluation of instructional effectiveness. Journal of Management Development, 2014, 33(3), 218-244.

- Asadi, S. , Allison, J., Iranmanesh, M., Fathi, M., Safaei, M.; Saeed, F. Determinants of intention to use simulation-based learning in computers and networking courses: an ISM and MICMAC analysis. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 2024, 71, 6015–6030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaskar, P. , Bhaskar, P., Anthonisamy, A., Dayalan, P.; Joshi, A. Inhibiting factors influencing adoption of simulation-based teaching from management teacher’s perspective: prioritization using analytic hierarchy process. International Journal of Learning and Change. 2023, 15(5), 529–551. [CrossRef]

- Yasin, N. , Gilani, S. A. M., Contu, D.; Fayaz, M. J. Simulation-based learning in business and entrepreneurship in higher education: A review of the games available. In Technology and Entrepreneurship Education: Adopting Creative Digital Approaches to Learning and Teaching. 2022, pp.25–51). Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Sipoş, A.; Pacala, M. L. Simulation-Based Learning, an Essential Tool for Control Process in Food Engineering Education. Balkan Region Conference on Engineering and Business Education, 3(1), 383–389. [CrossRef]

- Pratt, M. A.; Hahn, S. (2015). Effects of simulation on student satisfaction with a capstone course. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Education, 2019, 27(1), 39–46. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz de la Torre Acha, A. , Rio Belver, R. M., Fernandez Aguirrebeña, J.; Merlo, C. Application of simulation and virtual reality to production learning. Education and Training, 2024, 66(2–3), 145–165. [CrossRef]

- Chaurasia, S. An empirical investigation on factors affecting perceived learning by training through simulations. Industrial and Commercial Training, 2017, 49(1), 22–32. [CrossRef]

- Celinšek, D.; Markič, M. Implementing problem-based learning in a higher education institution. International Journal of Management in Education, 2008, 2(1), 88– 107. [CrossRef]

- Bridges, S. M. , Corbet, E. F.; Chan, L. K. Designing problem-based curricula: The role of concept mapping in scaffolding learning for the health sciences. Knowledge Management and E-Learning, 2015, 7(1), 119–

133. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-84927165591&partnerID=40&md5=1385164cd245643a06830b997b75eb31, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Azam, R. , Farooq, M. U.; Riaz, M. R. A case study of problem-based learning from a civil engineering structural analysis course. Journal of Civil Engineering Education, 2024, 150(3). [CrossRef]

- Eräpuro-Piila, L. , Haka, M., Dietrich, P.; Kujala, J. Problem-based learning in university education: Do psychological preferences make a difference? International Journal of Management in Education. 2014, 8(2), 101–116. [CrossRef]

- Hermann, R. R. , Amaral, M.; Bossle, M. B. Integrating Problem-based Learning with International Internships in Business Education. Journal of Teaching in International Business, 2021, 32(3–4), 202–235. [CrossRef]

- Kompatscher, J. , Pacher, C.; Woschank, M. The logilegolab: A problem-based learning approach for higher education institutions. Proceedings of the International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management, 2021, 1834–1844. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-

85114258857&partnerID=40&md5=f1e7d05435a19f5a426ccb4465ab8866.

- Jabarullah, N. H.; Iqbal Hussain, H. The effectiveness of problem-based learning in technical and vocational education in Malaysia. Education and Training, 2019, 61(5), 552–567. [CrossRef]

- Hölzner, H. M.; Halberstadt, J. Challenge-based Learning: How to Support the Development of an Entrepreneurial Mindset. In Transforming Entrepreneurship Education: Interdisciplinary Insights on Innovative Methods and Formats, 2022, (pp. 23–36). Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Jordán-Fisas, A.; Mas-Machuca, M. Bringing social challenges to the classroom: Connecting students with local agents. International Journal of Intellectual Property Management, 2022, 12(1), 129–147. [CrossRef]

- Recke, M. P.; Perna, S. Application of narrative theory in project based software development education. In D. N. A (Ed.), Proceedings of the European Conference on Innovation and Entrepreneurship, ECIE, 2020, (Vols. 2020-Septe, pp. 538–544). Academic Conferences and Publishing International Limited. [CrossRef]

- Patiño, A. , Ramírez-Montoya, M. S.; Ibarra-Vazquez, G. Trends and research outcomes of technology-based interventions for complex thinking development in higher education: A review of scientific publications. Contemporary Educational Technology 2023, 15(4). [CrossRef]

- Fassbender, U. , Papenbrock, J.; Pilz, M. Teaching entrepreneurship to life- science students through Problem Based Learning. International Journal of Management Education, 2022, 20(3). [CrossRef]

- Heng, L. K.; Mansor, Y. Impact of information literacy training on academic self- efficacy and learning performance of university students in a problem-based learning environment. Pertanika Journal of Social Science and Humanities, 2010, 18(SPEC. ISSUE), 121–134. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-

78651497043&partnerID=40&md5=00fea64f68d452bea15616d1612deb10.

- Jareño, F. , Álamo, R., Gabriela Lagos, M.; Jiménez, J. J. Perception of the acquisition of competences for university professors in a context of problem-based learning methodology. International Journal of Management in Education, 2020, 14(6), 628– 643. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-

85095798572&partnerID=40&md5=c47c13fbe79e941aa1dccb047fab81c6.

- Muñoz Cerón, E. , Ortega Jódar, M. J., Rubio Paramio, M. Á.; Hermoso Orzáez, M. J. Experiences of problem-based learning. photovoltaic systems integration project aimed at university and pre-university students. Proceedings from the International Congress on Project Management and Engineering, 2020, 2150–2161. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-

85150719431&partnerID=40&md5=27b736e794c7b80144ae58fc9ae241a8.

- Lee, N.; Jo, M. Exploring problem-based learning curricula in the metaverse: The hospitality students’ perspective. Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport and Tourism Education, 2023, 32. [CrossRef]

- Donche, V. , Gijbels, D., Spooren, P.; Bursens, P. How Simulations of decision- making affect learning. In Professional and Practice-based Learning, 2018, (Vol. 22, pp. 121–127). Springer Nature. [CrossRef]

- Wilkin, C. L. Enhancing the AIS curriculum: Integration of a research-led, problem- based learning task. Journal of Accounting Education, 2014, 32(2), 185–199. [CrossRef]

- Vila, L. E. , Perez, P. J.; Morillas, F. G. Higher education and the development of competencies for innovation in the workplace. Management Decision, 2012, 50(9), 1634– 1648. [CrossRef]

- Alcantara-Concepcion, T.; Ramirez-Pulido, K. Teaching gender for STEM scholar community in a virtual learning environment: a path for scholar digital transformation. IBIMA Business Review, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Bachiller, P.; Bachiller, A. A teaching experience in business management and administration: An empirical analysis with finance. Innovar, 2015, 25(55), 185–194. [CrossRef]

- Dreifuss-Serrano, C.; Herrera, P. C. SDGs for the assessment of voluntourism learning experiences. 2022 IEEE International Humanitarian Technology Conference, IHTC, 2022, 27–31. [CrossRef]

- Gregersen, B. Role of universities for inclusive development and social innovation: Experiences from Denmark. In Universities, Inclusive Development and Social Innovation: An International Perspective, 2016, (pp. 369–385). Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]