Submitted:

10 July 2024

Posted:

11 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

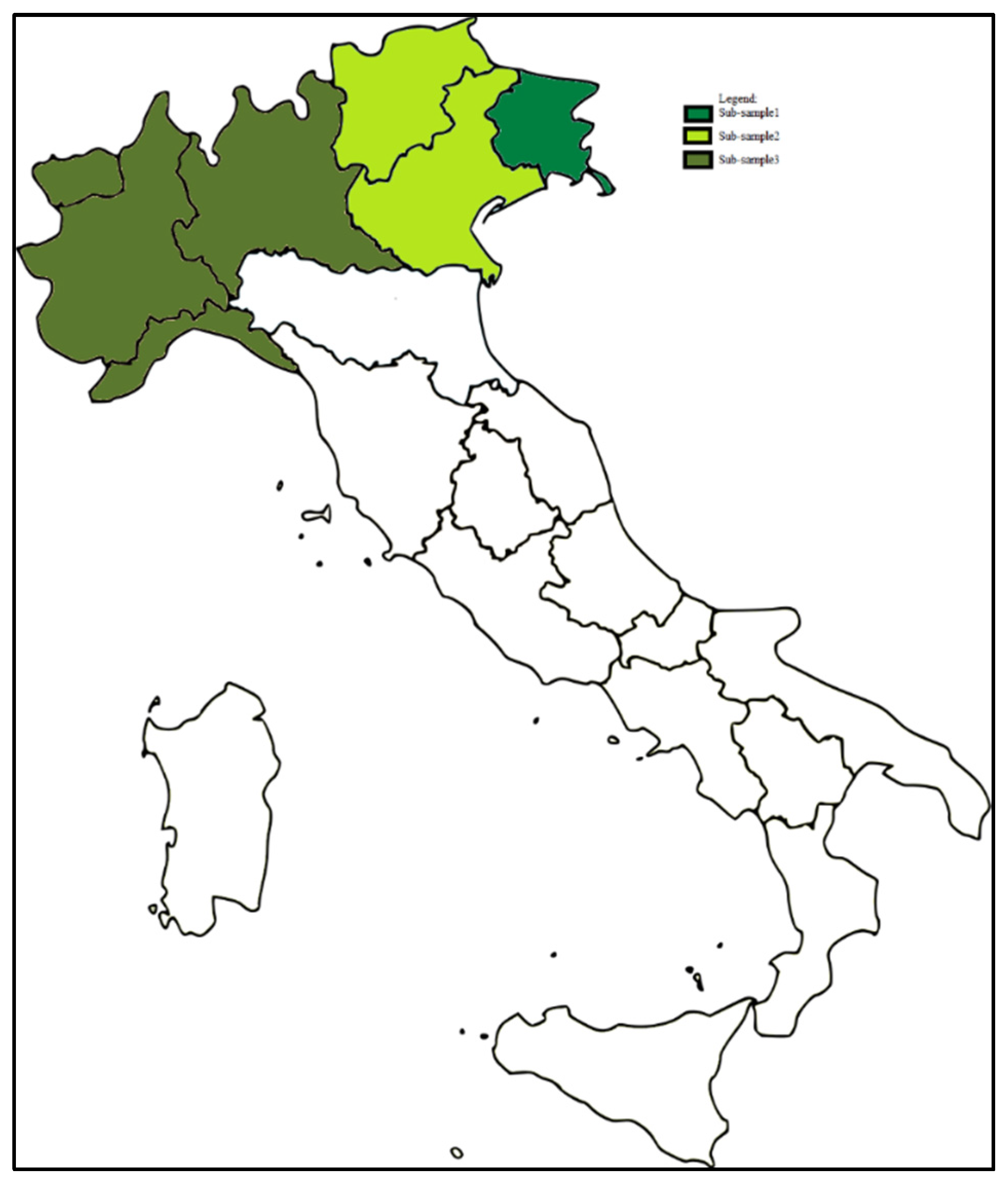

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Questionnaire Survey

2.3. Economic Valuation Methodology

3. Results

3.1. Sample Description

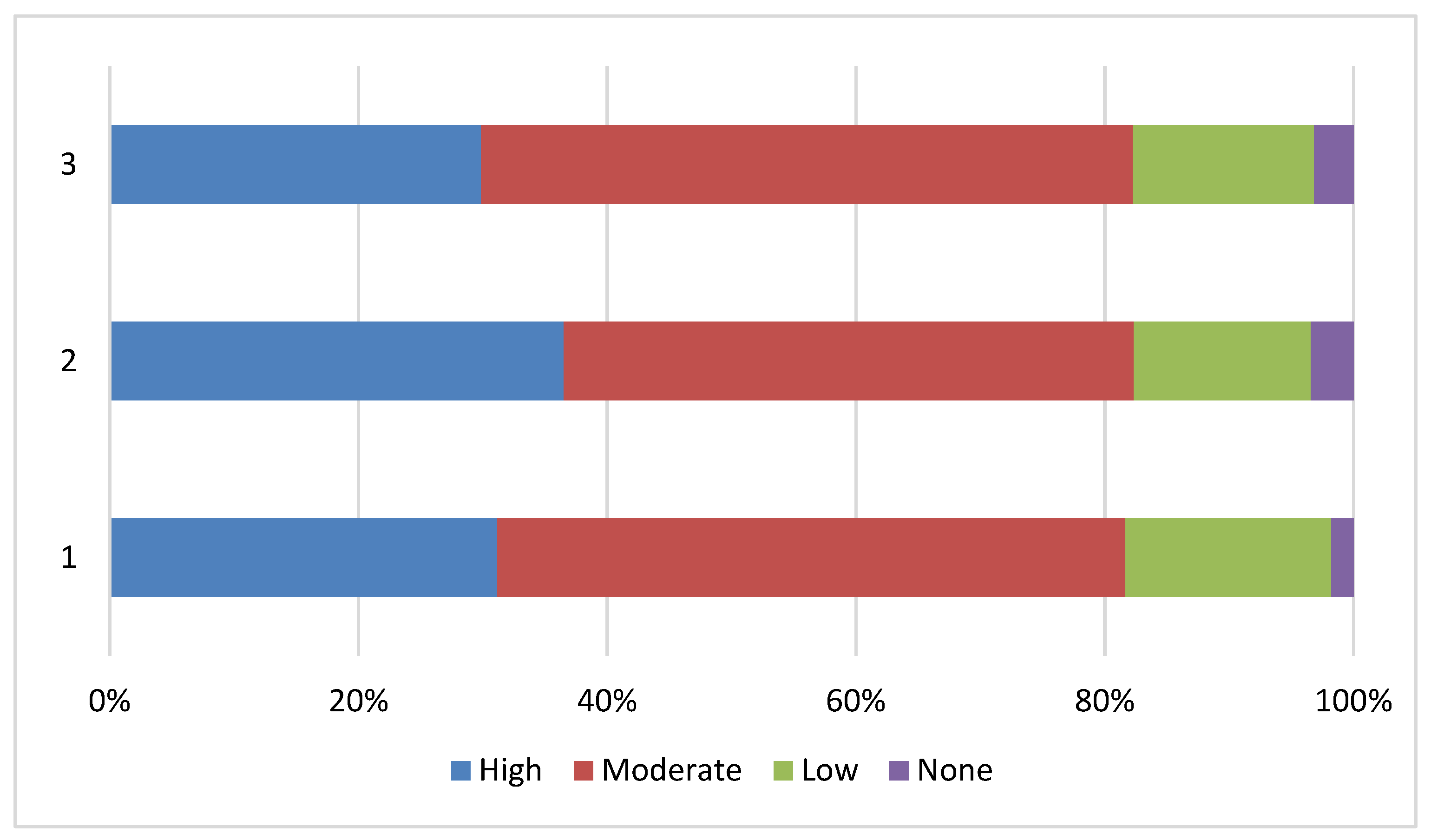

3.2. Potential Demand of FB

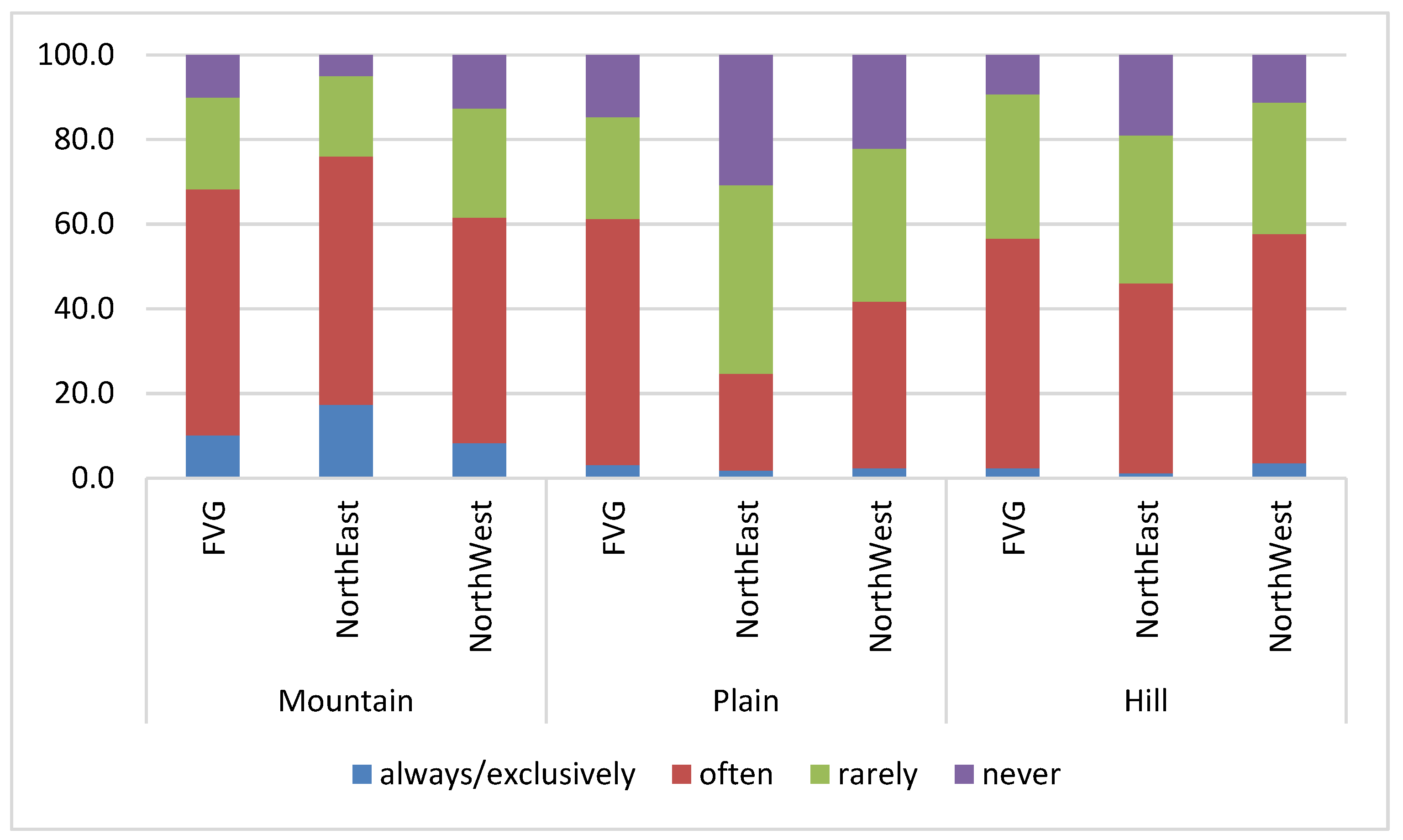

3.3. Visitors’ Attitudes and Preferences toward Forest Frequentation and FB

- physical and/or psychological “Being-away” - feeling removed from one’s usual environment and daily routines;

- “Fascination” - being captivated by the aesthetic and archetypal characteristics of the place;

- “Coherence – sub criteria of Extent” - physical dimensions and contents of the place that do not seem to limit interest;

- “Scope - sub criteria of Compatibility” - finding full alignment with one’s expectations and ability to engage with the place.

- Walking without exertion, strolling, and exploring the surrounding space;

- Pausing, relaxing, contemplating, and observing the surroundings and details of the place;

- Breathing deeply and doing breathing exercises;

- Sensing one’s own body through simple movements interacting with the environment and its components;

- Opening and awakening the senses.”

3.4. Flows

3.5. Value

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, Qing. Shinrin-Yoku: The Art and Science of Forest Bathing; Publisher: Penguin UK, 2018; pp. 320.

- Miyazaki, Y. Shinrin-yoku: the Japanese way of forest bathing for health and relaxation. 1st ed.; Aster-Octopus Publishing Group Limited: London, UK, 2018; pp. 192.

- Hansen, M.M.; Jones, R; Tocchini, K. Shinrin-Yoku (Forest Bathing) and Nature Therapy: A State-of-the-Art Review. Environ. Res. Public Health. July 2017, 14, 851.

- Zhang, Z.; Ye, B. Forest Therapy in Germany, Japan and China: Proposal, Development Status, and Future Prospects. Forests 2022, 13, 1289. [CrossRef]

- Droli, M.; Sigura, M.; Vassallo, F.B.; Droli, G.; Iseppi, L. Evaluating Potential Respiratory Benefits of Forest-Based Experiences: A Regional Scale Approach. Forests 2022, 13-3, 387. [CrossRef]

- Farkic, J.; Isailovic, G.; Taylor, S. Forest bathing as a mindful tourism practice. Annals of Tourism Research Empirical Insights, 2021, 2, 100028. [CrossRef]

- Lazo Álvarez, A.C.; Ednie, A.; Gale-Detrich, T. Contributions of Nature Bathing to Resilience and Sustainability. In Tourism and Conservation-based Development in the Periphery. Natural and Social Sciences of Patagonia; Gale-Detrich, T., Ednie, A., Bosak, K., Eds; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 389–408. [CrossRef]

- Hirons, M.; Comberti, C.; Dunford, R. Valuing Cultural Ecosystem Services. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2016. 41, pp. 545-74.

- Prete, C.; Cozzi, M.; Viccaro, M.; Sijtsma, F.; Romano, S. Foreste e servizi ecosistemici culturali: mappatura su larga scala utilizzando un approccio partecipativo. L’Italia Forestale e Montana. 2020, 75, 3, pp. 119-136. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Van Damme, S.; Li, L.; Uyttenhove, P. Evaluation of cultural ecosystem services: A review of methods. Ecosystem Services. 2019, 37. [CrossRef]

- Gatto, P.; Vidale, E.; Secco, L.; Pettenella, D. Exploring the willingness to pay for forest ecosystem services by residents of the Veneto Region. Bio-Based and Applied Economics 2013, 3, 1, pp. 21-43. [CrossRef]

- Bateman, I.J.; Mace, G.M.; Fezzi, C.; Atkinson, G.; Turner, K. Economic Analysis for Ecosystem Service Assessments. Environ. Resource Econ. 2011, 48, pp. 177–218. [CrossRef]

- Bateman, I.J.; Turner, R.K. Valuation of the environment, methods and techniques: the contingent valuation method. In Sustainable Environmental Economics and Management. Principles and practice; Turner, R.K., Eds.; Belhaven Press: London, UK, 1993; pp. 120-191.

- Adamowicz, W.L. What’s it worth? An examination of historical trends and future directions in environmental valuation. Australian Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics 2004, 48, 3, pp. 419-443.

- PEFC. Standard di certificazione dei Servizi Ecosistemici generati da boschi e piantagioni gestiti in maniera sostenibile Versione 0.4; PEFC. https://pefc.it/ (archived on 17th May 2024).

- FSC. Guidance for Demonstrating Ecosystem Services Impacts - FSC-GUI-30-006 V1-1 EN; FSC. https://connect.fsc.org/ (archived on 17th May 2024).

- Immich, G.; Robl, E. Development of Structural Criteria for the Certification and Designation of Recreational and Therapeutic Forests in Bavaria, Germany. Forests 2023, 14, 1273. [CrossRef]

- Binder, S; Haight, R.G.; Polasky, S.; Warziniack, T.; Mockrin, M.H.; Deal, R.L.; Arthaud, G. Assessment and valuation of forest ecosystem services: State of the science review; Gen. Tech. Rep. NRS-170; Newtown Square, PA: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northern Research Station, USA, 2017; 47 p.

- Haines-Young, R. Common International Classification of Ecosystem Services (CICES) V5.2 and Guidance on the Application of the Revised Structure. Available online: www.cices.eu. 2023 (accessed on 31st May 2024).

- Brander, L.M.; de Groot, R; Guisado Goñi, V.; van’t Hoff, V.; Schägner, P.; Solomonides, S.; McVittie, A.; Eppink, F.; Sposato, M.; Do, L.; Ghermandi, A.; Sinclair, M. Ecosystem Services Valuation Database (ESVD). Foundation for Sustainable Development and Brander Environmental Economics. Available online: https://esvd.net Database Version APR2024V1.1, 2024 (accessed on 30th May 2024).

- Tempesta, T.; Visintin, F.; Marangon F. Ecotourism Demand in North-East Italy, Proceedings of the International Conference on “ Monitoring and Management of Visitor Flows in Recreational and Protected Areas”, Vienna, Austria, 30 January - 2 February 2002, 2002 pp. 373-379.

- Tempesta, T.; Thiene, M. The willingness to pay for the conservation of mountain landscape in Cortina D’Ampezzo (Italy). in Proceeding of 90th EAAE Seminar “Multifunctional Agriculture, policies and markets: understanding the critical linkages”. 2004, Rennes-France.

- Scarpa, R.; Thiene, M. Destination choice models for rock-climbing in the North-Eastern Alps: a latent-class approach based on intensity of preferences. Land Economics 2005, 81, 3, pp. 426-444. [CrossRef]

- Scarpa, R.; Thiene, M.; Tempesta, T. Latent class count models of total visitation demand: days out in the Eastern Alps. Environmental and Resource Economics 2007, 38, 4, pp. 447-460. [CrossRef]

- Thiene, M.; Scarpa, R. Hiking in the Alps: exploring substitution patterns of hiking destinations. Tourism Economics 2008 14, 2, pp. 263-282.

- Paletto, A.; Geitner, C.; Grilli, G.; Hastik, R.; Pastorella, F.; Rodrìguez Garcìa, L. Mapping the Value of Ecosystem Services: A Case Study from the Austrian Alps. 2015 Annals of forest research, 58, 1, pp. 157–175.

- Paletto, A.; Notaro, S.; Sergiacomi, C.; Di Mascio, F. The Economic Value of Forest Bathing: An Example Case of the Italian Alps. Forests 2024, 15, 543. [CrossRef]

- Hirons, M; Comberti, C.; Dunford, Valuing Cultural Ecosystem Services, R. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2016, 41, PP. 545-574.

- Hermes, J.; Albert., C.; von Haaren, C. Modelling flows of recreational ecosystem services in Germany. Leibniz Universität Hannover, Institute of Environmental Planning, Hannover, Germany. 2013, preprint.

- Müller, A.; Olschewski, R.; Unterberger, C.; Knoke, T. The valuation of forest ecosystem services as a tool for management planning – A choice experiment. Journal of Environmental management, 271. 2020. Scopus. [CrossRef]

- Cerda Jiménez, C.. Valuing biodiversity attributes and water supply using choice experiments: a case study of La Campana Peñuelas Biosphere Reserve, Chile. Environ Monit Assess, 185, pp. 253–266. 2013.

- Plieninger, T.; Bieling, C.; Ohnesorge, B.; Schaich, H.; Schleyer, C.; Wolff, F. Exploring futures of ecosystem services in cultural landscapes through participatory scenario development in the Swabian Alb, Germany. Ecol. Soc. 2013, pp. 18-39.

- Willis, K.G.; Garrod, G.; Scarpa, R.; Powe, N.; Lovett, A.; Bateman, I J.; Hanley, N.; Macmillan, D. Report to Forestry Commission. Social&Environmental Benefits of Forestry Phase 2: The social and enviromental benefits of forests in Great Britain. Centre for Research in Environmental Appraisal & Management University of Newcastle, Newcastle, UK. 2003, p. 34.

- Christie, M.; Hyde, T.; Cooper, R.; Fazey, I.; Dennis, P.; Warren, J.; Colombo S.; Hanley, N. Economic Valuation of the Benefits of Ecosystem Services delivered by the UK Biodiversity Action Plan. Defra Project: NE0112, Final Report, Institute of Biological, Environmental and Rural Sciences, Aberystwyth University, Aberystwyth, Ceredigion, Wales, 2011; p. 164.

- Mourato, S.; Atkinson, G.; Collins, M.; Gibbons S.; MacKerron, G.; Resende, G. Economic analysis of cultural services. UK NEA Economic Analysis Report (Final report). 2010 (Available online: http://uknea.unep-wcmc.org/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=COKihFXhPpc%3D&tabid=82, accessed on 30th May 2024).

- Yao, N.; Gu, C.; Qi, J.; Shen, S.; Nan, B.;Wang, H. Protecting Rural Large Old Trees with Multi-Scale Strategies: Integrating Spatial Analysis and the Contingent Valuation Method (CVM) for Socio-Cultural Value Assessment. Forests 2024, 15, 18. [CrossRef]

- Busk, H.; Sidenius, U.; Kongstad, L.P.; Corazon, S.S.; Petersen, C.B.; Poulsen, D.V.; Nyed, P.K.; Stigsdotter, U.K. Economic Evaluation of Nature-Based Therapy Interventions—A Scoping Review. Challenges 2022, 13, 23. [CrossRef]

- Pretty, J.; Barton, J. Nature-Based Interventions and Mind–Body Interventions: Saving Public Health Costs Whilst Increasing Life Satisfaction and Happiness. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7769. [CrossRef]

- Elsey, H.; Farragher, T.; Tubeuf, S.; Bragg, R.; Elings, M.; Brennan, C.; Gold, R.; Shickle, D.; Wickramasekera, N.; Richardson, Z.; et al. Assessing the impact of care farms on quality of life and offending: A pilot study among probation service users in England. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e019296. [CrossRef]

- CJC Consulting. Branching Out Economic Study Extension. 2016. Available online: https://forestry.gov.scot/images/corporate/pdf/branching-out-report-2016.pdf (accessed on 14 June 2024).

- Uyan, K.G.V. Estimation of Tourists’ Willingness to Pay Entrance Fees for a Forest Bathing Site in the Philippines. Journal of Management and Development Studies 2020, 9 (1), pp. 30-47.

- Mitchell, R.C.; Carson, R.T. Using Surveys to Value Public Goods: The Contingent Valuation Method. The Contingent Valuation Method, 1st ed.; Resources for the Future: Washington, DC, USA, 1989.

- Hanemann, W.M. Welfare evaluations in contingent valuation experiments with discrete responses. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 1984, 66, pp. 332–341. [CrossRef]

- Boyle, K.J. Contingent valuation in practice. In A primer on nonmarket valuation., 2nd ed.; Champ, P.A.; Boyle, K.J.; Brown, T.C., Eds.; Springer, Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 83-131.

- Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, United Kingdom, 1989. ISBN 978-0-521-34139-4.

- Kellert, S.R. The Biological Basis for Human Values of Nature. In The Biophilia Hypothesis; Kellert, S.R., Wilson, E.O., Eds.; Island Press: Washington DC; pp. 42-69.

- Ulrich, R.S. Aesthetic and affective response to natural environment. In Human Behavior and Environment; Altman, I., Wohlwill, J., Eds.; Plenum Press: New York, 1983; Volume 6, pp. 85-125.

- Ulrich, R.S. Visual Landscapes and Psychological Well-being. Landscape Research 1979, 4, 17-23. [CrossRef]

- Pasini, M.; Berto, R.; Brondino, M.; Hall, R.; Ortner, C. How to Measure the Restorative Quality of Environments: The PRS-11. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 2014, 159, 293-297. [CrossRef]

- Frey, U.J.; Pirscher, F. Distinguishing protest responses in contingent valuation: A conceptualization of motivations and attitudes behind them. PLoS One. 2019 Jan, 8, 14(1):e0209872. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Doimo, I.; Masiero, M.; Gatto, P. Forest and Wellbeing: Bridging Medical and Forest Research for Effective Forest-Based Initiatives. Forests 2020, 11, 791. [CrossRef]

- Chaudhry, P.; Tewari, V.P. A Comparison between TCM and CVM in Assessing the Recreational Use Value of Urban Forestry, Commonwealth Forestry Association - The international forestry review, 2006, 8, 4, pp. 439-448.

- Mayor, K.; Scott, S.; Tol, R.S.J. Comparing the travel cost method and the contingent valuation method – An application of convergent validity theory to the recreational value of Irish forests. Dublin: Economic and Social Research Institute, 2007. 21 p. (ESRI Working Paper; 190).

- Hanley, N.D. Valuing rural recreation benefits: An empirical comparison of two approaches. Journal of Agricultural Economics 1989, 40, 3, pp. 361-374. [CrossRef]

- Cropper, M.L.; Oates, W.A. Environmental Economics: A Survey. Journal of economic Literature 1992, 30, pp. 675-740.

- Louv, R. Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children from Nature-deficit Disorder, 1st ed.; Algonquin Books: New York, USA, 2005; pp. 390.

- Russell, R.; Guerry, A.D.; Balvanera, P.; Gould, R.K.; Basurto, X.; et al. Humans and nature: how knowing and experiencing nature affect well-being. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2013, 38, pp. 473–502. [CrossRef]

- Sauerlender, J.P. Design of a Nature-Based Health Intervention: Self-Guided Forest Bathing for Public Gardens. Masters’s Thesis, University of Washington, Washington, DC, USA, 2021.

- Kil, N.; Stein, T.V.; Holland, S.M.; Kim, J.J.; Kim, J.; Petitte, S. The Role of Place Attachment in Recreation Experience and Outcome Preferences among Forest Bathers. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2021, 35, 100410. [CrossRef]

- Doimo, I.; Masiero, M.; Gatto, P. Forest and Wellbeing: Bridging Medical and Forest Research for Effective Forest-Based Initiatives. Forests 2020, 11, 791. [CrossRef]

- Subirana-Malaret, M.; Miró, A.; Camacho, A.; Gesse, A.; McEwan, K. A Multi-Country Study Assessing the Mechanisms of Natural Elements and Sociodemographics behind the Impact of Forest Bathing on Well-Being. Forests 2023, 14, 904. [CrossRef]

- Guardini, B.; Secco, L.; Moè, A.; Pazzaglia, F.; De Mas, G.; Vegetti, M.; Perrone, R.; Tilman, A.; Renzi, M.; Rapisarda, S. A Three-Day Forest-Bathing Retreat Enhances Positive Affect, Vitality, Optimism, and Gratitude: An Option for Green-Care Tourism in Italy? Forests 2023, 14, 1423. [CrossRef]

- Kotera, Y.; Richardson, M.; Sheffield, D. Effects of Shinrin-Yoku (Forest Bathing) and Nature Therapy on Mental Health: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. 2022, 20, PP. 337–361. [CrossRef]

| Age | Friuli Venezia Giulia | Northeast Italy | Northwest Italy | ||||||

| Age group | Male | Female | Total | Male | Female | Total | Male | Female | Total |

| 18-29 | 71.555 | 63.938 | 135.493 | 654.931 | 596.745 | 1.251.676 | 990.159 | 899.476 | 1.889.635 |

| 30-44 | 98.638 | 93.584 | 192.222 | 898.698 | 875.065 | 1.773.763 | 1.387.730 | 1.339.275 | 2.727.005 |

| 45-54 | 92.950 | 93.050 | 186.000 | 818.063 | 817.527 | 1.635.590 | 1.244.076 | 1.237.603 | 2.481.679 |

| 55-64 | 94.781 | 97.102 | 191.883 | 800.253 | 820.943 | 1.621.196 | 1.218.002 | 1.252.829 | 2.470.831 |

| 65-75 | 76.082 | 85.878 | 161.960 | 618.563 | 684.335 | 1.302.898 | 959.493 | 1.072.036 | 2.031.529 |

| 434.006 | 433.552 | 867.558 | 3.790.508 | 3.794.615 | 7.585.123 | 5.799.460 | 5.801.219 | 11.600.679 | |

| Age | Friuli Venezia Giulia | Northeast Italy | Northwest Italy | Sample composition | ||||||||

| Group | Male | Female | Total | Male | Female | Total | Male | Female | Total | Male | Female | Total |

| 18-29 | 32 | 38 | 70 | 31 | 38 | 69 | 45 | 26 | 71 | 8,9% | 8,4% | 17,2% |

| 30-44 | 51 | 67 | 118 | 55 | 55 | 110 | 42 | 23 | 65 | 12,2% | 11,9% | 24,1% |

| 45-54 | 51 | 52 | 103 | 47 | 49 | 96 | 42 | 33 | 75 | 11,5% | 11,0% | 22,5% |

| 55-64 | 34 | 29 | 63 | 34 | 46 | 80 | 58 | 55 | 113 | 10,3% | 10,7% | 21,0% |

| 65-75 | 29 | 15 | 44 | 33 | 20 | 53 | 39 | 49 | 88 | 8,3% | 6,9% | 15,2% |

| 197 | 201 | 398 | 200 | 208 | 408 | 226 | 186 | 412 | 51,1% | 48,9% | 100,0% | |

| Sub-sample of destination | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Sub-sample 1 | Sub-sample 2 | Sub-sample 3 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Friuli VG | Veneto | Aut.Prov. Trento | Aut.Prov. Bolzano | Lombardy | Piedmont | Aosta Valley | Liguria | Total | |||||||||||||

| Sub-sample of origin | DT | V | DT | V | DT | V | DT | V | DT | V | DT | V | DT | V | DT | V | DT | V | |||

| Sub-sample 1 | Friuli VG | 12.0 | 2.7 | 1.9 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 16.3 | 6.5 | ||

| Sub-sample 2 | Veneto | 1.3 | 0.7 | 8.8 | 2.9 | 2.3 | 1.4 | 1.7 | 1.2 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 15.4 | 7.3 | ||

| Aut.Prov. Trento | 1.4 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 2.4 | 1.3 | 18.1 | 1.9 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 23.5 | 6.3 | |||

| Aut.Prov. Bolzano | 0.7 | 0.6 | 2.2 | 0.9 | 25.0 | 2.9 | 8.1 | 2.4 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 37.2 | 7.8 | |||

| Sub-sample 3 | Lombardy | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 1.8 | 0.6 | 1.2 | 10.1 | 2.9 | 1.2 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 15.8 | 9.8 | ||

| Piedmont | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.9 | 0.4 | 13.9 | 3.7 | 3.3 | 1.9 | 1.7 | 1.9 | 20.6 | 8.8 | |||

| Aosta Valley | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 4.1 | 0.6 | 21.3 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 25.6 | 1.8 | |||

| Liguria | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 2.6 | 3.2 | 3.1 | 0.8 | 1.1 | 10.7 | 3.7 | 17.7 | 12.2 | |||

| Total | 16.3 | 5.6 | 15.1 | 7.4 | 32.2 | 8.8 | 30.4 | 8.8 | 13.8 | 7.7 | 23.2 | 9.2 | 27.1 | 4.8 | 14.0 | 8.0 | |||||

| Sub-sample of destination | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Sub-sample 1 | Sub-sample 2 | Sub-sample 3 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Friuli VG | Veneto | Aut.Prov. Trento | Aut.Prov. Bolzano | Lombardy | Piedmont | Aosta Valley | Liguria | Total | |||||||||||||

| Sub-sample of origin | DT | V | DT | V | DT | V | DT | V | DT | V | DT | V | DT | V | DT | V | DT | V | |||

| Sub-sample 1 | Friuli VG | 72.7 | 38.5 | 12.1 | 15.4 | 3.0 | 7.7 | 3.0 | 15.4 | 3.0 | 7.7 | 0.0 | 7.7 | 3.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

| Sub-sample 2 | Veneto | 9.7 | 6.7 | 58.1 | 40.0 | 16.1 | 20.0 | 9.7 | 13.3 | 3.2 | 6.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

| Aut.Prov. Trento | 6.4 | 7.7 | 4.3 | 15.4 | 10.6 | 23.1 | 76.6 | 30.8 | 2.1 | 7.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 7.7 | 100.0 | 100.0 | |||

| Aut.Prov. Bolzano | 1.4 | 6.3 | 5.4 | 12.5 | 67.6 | 37.5 | 21.6 | 31.3 | 1.4 | 6.3 | 0.0 | 6.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | |||

| Sub-sample 3 | Lombardy | 3.1 | 5.0 | 6.3 | 10.0 | 6.3 | 20.0 | 3.1 | 10.0 | 62.5 | 30.0 | 6.3 | 10.0 | 6.3 | 10.0 | 3.1 | 10.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

| Piedmont | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.4 | 5.6 | 4.9 | 5.6 | 68.3 | 38.9 | 17.1 | 22.2 | 7.3 | 22.2 | 100.0 | 100.0 | |||

| Aosta Valley | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 25.0 | 15.7 | 25.0 | 84.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 25.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | |||

| Liguria | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.9 | 4.2 | 2.9 | 4.2 | 5.7 | 4.2 | 5.7 | 20.8 | 17.1 | 25.0 | 5.7 | 8.3 | 60.0 | 29.2 | 100.0 | 100.0 | |||

| Sub-sample of destination | |||||||||||||||||||

| Sub-sample 1 | Sub-sample 2 | Sub-sample 3 | |||||||||||||||||

| Friuli VG | Veneto | Aut.Prov. Trento | Aut.Prov. Bolzano | Lombardy | Piedmont | Aosta Valley | Liguria | ||||||||||||

| Sub-sample of origin | DT | V | DT | V | DT | V | DT | V | DT | V | DT | V | DT | V | DT | V | |||

| Sub-sample 1 | Friuli VG | 75.0 | 55.6 | 12.9 | 13.3 | 1.6 | 5.6 | 1.7 | 11.8 | 3.6 | 5.9 | 0.0 | 5.6 | 1.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| Sub-sample 2 | Veneto | 9.4 | 11.1 | 58.1 | 40.0 | 7.8 | 16.7 | 5.0 | 11.8 | 3.6 | 5.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| Aut.Prov. Trento | 9.4 | 11.1 | 6.5 | 13.3 | 7.8 | 16.7 | 60.0 | 23.5 | 3.6 | 5.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 6.7 | |||

| Aut.Prov. Bolzano | 3.1 | 11.1 | 12.9 | 13.3 | 78.1 | 33.3 | 26.7 | 29.4 | 3.6 | 5.9 | 0.0 | 5.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |||

| Sub-sample 3 | Lombardy | 3.1 | 11.1 | 6.5 | 13.3 | 3.1 | 22.2 | 1.7 | 11.8 | 71.4 | 35.3 | 4.5 | 11.1 | 3.6 | 25.0 | 4.0 | 13.3 | ||

| Piedmont | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.7 | 5.9 | 7.1 | 5.9 | 63.6 | 38.9 | 12.5 | 50.0 | 12.0 | 26.7 | |||

| Aosta Valley | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5.9 | 18.2 | 5.6 | 76.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 6.7 | |||

| Liguria | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.2 | 6.7 | 1.6 | 5.6 | 3.3 | 5.9 | 7.1 | 29.4 | 13.6 | 33.3 | 3.6 | 25.0 | 84.0 | 46.7 | |||

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | |||

| FB factor | n. | Statement | Mean |

| Well-being | 1 | I frequent the forests because the air is healthy | 8,0 |

| Fascination | 2 | I like forests that can be explored | 7,7 |

| Well-being | 3 | The forest environment scares me | 2,7 |

| Being away | 4 | I really like to immerse myself in the forests because it is a refuge from daily worries | 7,1 |

| Coherence | 5 | I like forests where there are diverse trees (in species, height and age) and the undergrowth is rich but does not obstruct the view | 7,6 |

| Well-being | 6 | I only like forests that are easily accessible (e.g., availability of parking, no gates and/or obstacles) | 5,7 |

| Well-being | 7 | I like to walk in the forests without exerting myself | 6,9 |

| Being away | 8 | I frequent the forests because I have little contact with nature in my daily life | 6,3 |

| Fascination | 9 | I like the forest when there are several interesting things that attract my attention (e.g., streams, rocks, cliffs, old trees) | 7,8 |

| Well-being | 10 | Immersing myself in the forests creates positive emotion for me | 8,2 |

| Coherence | 11 | I like to frequent the forest when there is a clear order in the physical layout of the place | 5.9, 5.4, 5.7* |

| Fascination | 12 | I like the forests because it is an environment that fascinates me | 7,9 |

| Scope | 13 | I would never frequent the forest for recreational activities | 3,0 |

| Well-being | 14 | I frequent the forests for health reasons (e.g., I activate metabolism, improve mood and sleep quality) | 6,5 |

| Well-being | 15 | Contact with nature makes me uncomfortable | 1.9, 1.4, 1.7* |

| Scope | 16 | I would never frequent the forest to engage in sports activities | 3.2, 2.6, 3.0 |

| * the means refer to Sub-sample 1, 2, and 3 respectively | |||

| Friuli Venezia Giulia | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Age group | Annual FB hikes | Inhabitants | Hikes | ||||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | Total | 01.01.2024 | Total | Average | |

| 18-29 | 2.5% | 2.8% | 2.8% | 4.7% | 1.4% | 2.2% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.3% | 0.0% | 0.8% | 0.0% | 1.1% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 18.7% | 135,493 | 85,674 | 0.6 |

| 30-44 | 1.9% | 4.7% | 7.2% | 4.5% | 1.9% | 5.3% | 0.6% | 0.0% | 1.4% | 0.0% | 1.7% | 0.0% | 1.9% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 31.2% | 192,222 | 233,451 | 1.2 |

| 45-54 | 2.5% | 3.3% | 3.9% | 1.9% | 2.5% | 4.2% | 1.1% | 0.6% | 0.6% | 0.0% | 1.9% | 0.0% | 1.4% | 0.0% | 0.3% | 0.6% | 0.3% | 25.1% | 186,000 | 215,532 | 1.2 |

| 55-64 | 1.4% | 2.5% | 1.7% | 0.8% | 1.7% | 2.2% | 0.6% | 0.3% | 0.8% | 0.0% | 2.8% | 0.0% | 0.3% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 15.0% | 191,883 | 133,089 | 0.7 |

| 65-74 | 2.5% | 1.4% | 2.8% | 0.8% | 0.6% | 0.6% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.8% | 0.0% | 0.6% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 10.0% | 161,960 | 47,821 | 0.3 |

| 10.9% | 14.8% | 18.4% | 12.8% | 8.1% | 14.5% | 2.2% | 0.8% | 3.1% | 0.0% | 8.1% | 0.0% | 5.3% | 0.0% | 0.3% | 0.6% | 0.3% | 100.0% | 867,558 | 715,566 | 0.8 | |

| Northeast Italy | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Age group | Annual FB hikes | Inhabitants | Hikes | ||||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | Total | 01.01.2024 | Total | Average | |

| 18-29 | 1.3% | 4.0% | 4.0% | 1.9% | 0.3% | 3.2% | 1.1% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 1.1% | 0.0% | 0.3% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 17.2% | 1,251,676 | 693,132 | 0.6 |

| 30-44 | 3.2% | 4.8% | 3.2% | 3.2% | 2.4% | 3.2% | 1.1% | 0.0% | 1.6% | 0.3% | 2.2% | 0.0% | 1.3% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 1.1% | 0.0% | 27.7% | 1,773,763 | 2,169,522 | 1.2 |

| 45-54 | 1.6% | 3.8% | 4.6% | 1.3% | 2.2% | 4.3% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.5% | 0.3% | 3.2% | 0.0% | 0.8% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 22.6% | 1,635,590 | 1,565,242 | 1.0 |

| 55-64 | 3.0% | 1.3% | 3.2% | 2.7% | 0.5% | 3.8% | 0.8% | 0.8% | 0.8% | 0.0% | 2.7% | 0.0% | 0.5% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 20.2% | 1,621,196 | 1,412,009 | 0.9 |

| 65-74 | 1.3% | 1.1% | 3.2% | 1.1% | 0.8% | 1.1% | 1.1% | 0.0% | 0.8% | 0.0% | 1.6% | 0.0% | 0.3% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 12.4% | 1,302,898 | 672,463 | 0.5 |

| 10.5% | 15.1% | 18.3% | 10.2% | 6.2% | 15.6% | 4.0% | 0.8% | 3.8% | 0.5% | 10.8% | 0.0% | 3.2% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 1.1% | 0.0% | 100.0% | 7,585,123 | 6,512,369 | 0.9 | |

| Northwest Italy | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Age group | Annual FB hikes | Inhabitants | Hikes | ||||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | Total | 01.01.2024 | Total | Average | |

| 18-29 | 1.6% | 2.6% | 3.4% | 3.2% | 0.5% | 1.6% | 0.8% | 0.5% | 0.5% | 0.0% | 1.6% | 0.0% | 1.3% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.3% | 0.0% | 18.0% | 1,889,635 | 1,464,717 | 0.8 |

| 30-44 | 1.3% | 2.4% | 3.2% | 1.6% | 1.6% | 1.9% | 0.3% | 0.0% | 0.3% | 0.0% | 2.9% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 15.3% | 2,727,005 | 1,688,146 | 0.6 |

| 45-54 | 2.1% | 2.4% | 2.6% | 2.4% | 1.1% | 3.4% | 1.3% | 0.3% | 0.5% | 0.3% | 0.3% | 0.0% | 0.8% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.3% | 0.0% | 17.7% | 2,481,679 | 1,706,975 | 0.7 |

| 55-64 | 3.7% | 3.2% | 4.8% | 2.1% | 2.6% | 4.2% | 1.3% | 0.3% | 0.0% | 0.3% | 2.9% | 0.0% | 1.1% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.8% | 0.0% | 27.2% | 2,470,831 | 2,882,636 | 1.2 |

| 65-74 | 3.2% | 0.8% | 3.7% | 2.4% | 2.6% | 2.1% | 1.3% | 0.5% | 0.8% | 0.3% | 3.2% | 0.0% | 0.8% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 21.7% | 2,031,529 | 1,993,908 | 1.0 |

| 11.9% | 11.4% | 17.7% | 11.6% | 8.5% | 13.2% | 5.0% | 1.6% | 2.1% | 0.8% | 10.8% | 0.0% | 4.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 1.3% | 0.0% | 100.0% | 11,600,679 | 9,736,382 | 0.8 | |

| Friuli Venezia Giulia | ||||||||||||||||

| Age group | Annual FB hikes | Inhabitants | Hikes | |||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | Total | 01.01.2024 | Total | Average | |

| 18-29 | 5.4% | 2.2% | 4.6% | 3.0% | 0.5% | 1.3% | 0.3% | 0.5% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 17.8% | 135,493 | 47,477 | 0.4 | ||

| 30-44 | 8.4% | 8.9% | 4.9% | 2.7% | 0.8% | 2.7% | 0.5% | 0.3% | 0.0% | 1.1% | 30.2% | 192,222 | 114,504 | 0.6 | ||

| 45-54 | 8.1% | 6.2% | 4.0% | 1.3% | 1.1% | 2.2% | 0.3% | 0.0% | 0.3% | 2.2% | 25.6% | 186,000 | 109,795 | 0.6 | ||

| 55-64 | 5.7% | 3.5% | 1.3% | 1.3% | 0.5% | 1.6% | 0.3% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 1.6% | 15.9% | 191,883 | 73,443 | 0.4 | ||

| 65-74 | 5.7% | 1.3% | 0.8% | 1.3% | 0.0% | 0.8% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.5% | 10.5% | 161,960 | 26,630 | 0.2 | ||

| 33.2% | 22.1% | 15.6% | 9.7% | 3.0% | 8.6% | 1.3% | 0.0% | 0.8% | 0.3% | 5.4% | 0.0% | 100.0% | 867,558 | 371,849 | 0.4 | |

| Northeast Italy | |||||||||||||||||

| Age group | Annual FB hikes | Inhabitants | Hikes | ||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | Total | 01.01.2024 | Total | Average | ||

| 18-29 | 3.9% | 3.9% | 3.4% | 2.6% | 0.0% | 1.0% | 0.5% | 0.5% | 0.3% | 1.3% | 17.4% | 1,251,676 | 568,944 | 0.5 | |||

| 30-44 | 5.5% | 6.0% | 7.0% | 2.1% | 1.0% | 2.3% | 0.5% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 2.3% | 26.8% | 1,773,763 | 1,216,295 | 0.7 | |||

| 45-54 | 4.9% | 6.5% | 3.4% | 2.3% | 1.0% | 1.3% | 0.5% | 0.3% | 0.0% | 2.3% | 22.6% | 1,635,590 | 968,609 | 0.6 | |||

| 55-64 | 6.0% | 2.1% | 3.4% | 3.6% | 0.3% | 2.3% | 0.5% | 0.0% | 0.3% | 1.3% | 19.7% | 1,621,196 | 821,125 | 0.5 | |||

| 65-74 | 3.4% | 1.6% | 3.4% | 1.0% | 0.3% | 0.5% | 0.3% | 0.0% | 0.5% | 2.6% | 13.5% | 1,302,898 | 609,147 | 0.5 | |||

| 23.6% | 20.0% | 20.5% | 11.7% | 2.6% | 7.5% | 2.3% | 0.8% | 1.0% | 0.0% | 9.9% | 0.0% | 100.0% | 7,585,123 | 4,184,120 | 0.6 | ||

| Northwest Italy | ||||||||||||||||||

| Age | Annual FB hikes | Inhabitants | Hikes | |||||||||||||||

| group | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | Total | 01.01.2024 | Total | Average | ||

| 18-29 | 2.8% | 1.8% | 6.3% | 2.3% | 1.0% | 2.0% | 0.3% | 0.0% | 0.8% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 17.2% | 1,889,635 | 813,261 | 0.4 | |||

| 30-44 | 4.3% | 2.5% | 1.8% | 1.8% | 1.0% | 1.8% | 0.3% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 2.8% | 16.2% | 2,727,005 | 1,463,608 | 0.5 | |||

| 45-54 | 4.3% | 4.3% | 2.0% | 1.0% | 1.0% | 1.5% | 1.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.3% | 2.0% | 17.5% | 2,481,679 | 1,281,677 | 0.5 | |||

| 55-64 | 5.8% | 4.1% | 7.8% | 1.8% | 1.5% | 2.3% | 1.0% | 0.5% | 0.0% | 0.5% | 2.3% | 27.6% | 2,470,831 | 1,964,154 | 0.8 | |||

| 65-74 | 6.3% | 2.8% | 6.6% | 0.8% | 1.3% | 1.0% | 0.5% | 0.3% | 0.5% | 0.3% | 1.3% | 21.5% | 2,031,529 | 1,059,481 | 0.5 | |||

| 23.5% | 15.4% | 24.6% | 7.6% | 5.8% | 8.6% | 3.0% | 0.8% | 1.3% | 1.0% | 8.4% | 0.0% | 100.0% | 11,600,679 | 6,582,181 | 0.6 | |||

| WTP per hike | Unit of measurement | Sample |

| Mean | € | 5.83 |

| Median | € | 5.00 |

| Standard deviation | € | 5.97 |

| 25th percentile | € | 0.00 |

| 50th percentile | € | 5.00 |

| 75th percentile | € | 10.00 |

| Willing to pay | % | 66.1 |

| Question code | Question text | Sample | Sub-sample 1 | Sub-sample 2 | Sub-sample 3 | |

| D14.2 | Frequence of visinting plain forest | -.077* | -.125* | |||

| D14.3 | Frequence of visinting hill forest | -.096** | -.123* | |||

| D15.a.3 | N. of daily hikes in Trentino | .115* | ||||

| D15.a.6 | N. of daily hikes in Piedmont | .111* | ||||

| D15.b.3 | N. of vacation hikes in Trentino | .118* | ||||

| D15.b.6 | N. of vacation hikes in Piedmont | .119* | .161** | |||

| D16.a | I frequent the forest because the air is healthy | .091** | .114* | |||

| D16.b | I like forest that can be explored | .121** | .139* | .124* | ||

| D16.d | I really like to immerse myself in the forest because it is a refuge from daily worries | .104** | .112* | .123* | ||

| D16.e | I like forest where there are diverse trees (in species, height, and age) and the undergrowth is rich but does not obstruct the view | .067* | ||||

| D16.f | I only like forest that are easily accessible (e.g., availability of parking, no gates and/or obstacles) | .088** | ||||

| D16.i | I like the forest when there are several interesting things that attract my attention (e.g., streams, rocks, cliffs, old trees) | |||||

| D16.j | Immersing myself in the forest creates positive emotions for me | .088** | .123* | |||

| D16.k | I like to frequent the forest when there is a clear order in the physical layout of the place | .078* | .112* | .113* | ||

| D16.l | I like the forest because it is an environment that fascinates me | .112** | .125* | .122* | ||

| D16.n | I frequent the forest for health reasons (e.g., I activate metabolism, improve mood and sleep quality) | .133** | .151** | .157** | ||

| D17 | For you, how important is it to have forests in which to practice FB? | .244** | .271** | .220** | .246** | |

| D18 | How many hikes per year of FB would you conduct in your home region? | .176** | .230** | .212** | ||

| D19 | How many FB hikes per year would you conduct in other regions of northern Italy? | .148** | .151** | .123** | .182** | |

| D29 | Income | .146** | .127* | .142** | .163** | |

|

** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level * Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level |

||||||

| Question code | Question text | Sample | Sub-sample 1 | Sub-sample 2 | Sub-sample 3 |

| D12 | Do you visit forests? | 0.007 | 0.148 | 0.104 | 0.175 |

| Model | Unstandardized coefficient | Standardized coefficient | t | Sign. | 95.0% Confidence interval for B | Collinearity statistics | ||||

| B | Std. Err. | Beta | Lower bound | B | Std. Err. | Beta | ||||

| 1 | (Constant) | 0.047 | 0.860 | 0.055 | 0.956 | -1.640 | 1.734 | |||

| D17 | 1.875 | 0.263 | 0.225 | 7.118 | 0.000 | 1.358 | 2.392 | 1.000 | 1.000 | |

| 2 | (Constant) | -0.883 | 0.878 | -1.005 | 0.315 | -2.606 | 0.840 | |||

| D17 | 1.803 | 0.262 | 0.216 | 6.895 | 0.000 | 1.290 | 2.316 | 0.996 | 1.004 | |

| D29 | 0.579 | 0.133 | 0.136 | 4.358 | 0.000 | 0.318 | 0.840 | 0.996 | 1.004 | |

| 3 | (Constant) | -1.521 | 0.886 | -1.716 | 0.086 | -3.261 | 0.218 | |||

| D17 | 2.145 | 0.274 | 0.257 | 7.837 | 0.000 | 1.608 | 2.683 | 0.895 | 1.117 | |

| D29 | 0.604 | 0.132 | 0.142 | 4.571 | 0.000 | 0.344 | 0.863 | 0.994 | 1.006 | |

| D18 | -0.065 | 0.017 | -0.129 | -3.934 | 0.000 | -0.098 | -0.033 | 0.895 | 1.117 | |

| 4 | (Constant) | 0.492 | 1.198 | 0.411 | 0.681 | -1.859 | 2.844 | |||

| D17 | 2.158 | 0.273 | 0.258 | 7.902 | 0.000 | 1.622 | 2.693 | 0.895 | 1.117 | |

| D29 | 0.658 | 0.134 | 0.155 | 4.929 | 0.000 | 0.396 | 0.920 | 0.967 | 1.034 | |

| D18 | -0.066 | 0.017 | -0.130 | -3.982 | 0.000 | -0.098 | -0.033 | 0.895 | 1.117 | |

| D26 | -0.643 | 0.258 | -0.078 | -2.489 | 0.013 | -1.150 | -0.136 | 0.973 | 1.028 | |

| 5 | (Constant) | -0.393 | 1.262 | -0.312 | 0.755 | -2.869 | 2.083 | |||

| D17 | 2.132 | 0.273 | 0.255 | 7.817 | 0.000 | 1.597 | 2.667 | 0.893 | 1.119 | |

| D29 | 0.651 | 0.133 | 0.153 | 4.881 | 0.000 | 0.389 | 0.912 | 0.967 | 1.035 | |

| D18 | -0.060 | 0.017 | -0.120 | -3.630 | 0.000 | -0.093 | -0.028 | 0.876 | 1.141 | |

| D26 | -0.627 | 0.258 | -0.076 | -2.428 | 0.015 | -1.133 | -0.120 | 0.972 | 1.029 | |

| D16_f | 0.155 | 0.070 | 0.069 | 2.207 | 0.028 | 0.017 | 0.293 | 0.978 | 1.022 | |

| Model | R | R-Squared | Adj R-Squared | Std. errore of the estimate |

| 1 | .225 | 0.050 | 0.049 | 5.86103 |

| 2 | .263 | 0.069 | 0.067 | 5.80654 |

| 3 | .290 | 0.084 | 0.081 | 5.76294 |

| 4 | .300 | 0.090 | 0.086 | 5.74728 |

| 5 | .307 | 0.094 | 0.090 | 5.73562 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).