Submitted:

11 July 2024

Posted:

12 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Ethical Aspects

Health Status Assessment

Clinical History and Physical Examination

Nutritional Assessment

Psychological Evaluation

General Biochemical and Metabolic Parameters, and Intestinal Microbiota Anaylisis

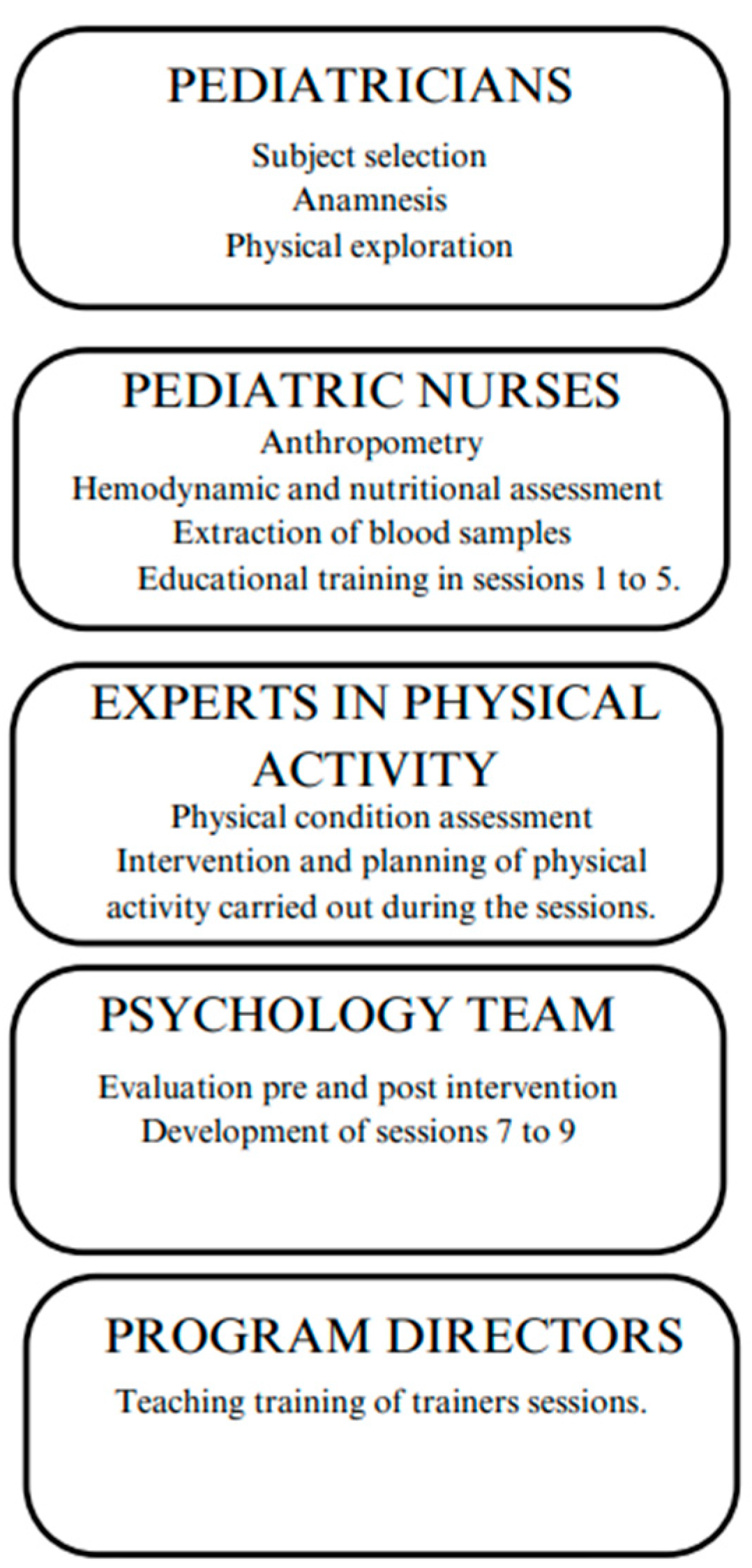

Design of the PinPo Group Intervention Program

Group Intervention

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

5. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alberto Moreno Aznar L, Lorenzo Garrido H, Aznar M LA, Garrido Obesidad LH. Obesidad infantil. Available from: www.aeped.es/protocolos/.

- Obesity and overweight [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jul 8]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight.

- Pulungan AB, Puteri HA, Ratnasari AF, Hoey H, Utari A, Darendeliler F, et al. Childhood Obesity as a Global Problem: a Cross-sectional Survey on Global Awareness and National Program Implementation. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol [Internet]. 2024 Mar 11 [cited 2024 Jul 3];16(1):31–40. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37622285/.

- Aesan - Agencia Española de Seguridad Alimentaria y Nutrición [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jul 8]. Available from: https://www.aesan.gob.es/AECOSAN/web/nutricion/detalle/aladino_2023.htm.

- Olza J, Gil-Campos M, Leis R, Bueno G, Aguilera CM, Valle M, et al. Presence of the metabolic syndrome in obese children at prepubertal age. Ann Nutr Metab [Internet]. 2011 Oct [cited 2024 Jul 3];58(4):343–50. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21996789/.

- Pulgarón, ER. Childhood obesity: a review of increased risk for physical and psychological comorbidities. Clin Ther [Internet]. 2013 Jan [cited 2024 Jul 3];35(1). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23328273/.

- Ciężki S, Odyjewska E, Bossowski A, Głowińska-Olszewska B. Not Only Metabolic Complications of Childhood Obesity. Vol. 16, Nutrients. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI); 2024.

- Smith KE, Mason TB. Psychiatric comorbidity associated with weight status in 9 to 10 year old children. Pediatr Obes. 2022 May 1;17(5).

- Smith JD, Fu E, Kobayashi MA. Prevention and Management of Childhood Obesity and its Psychological and Health Comorbidities. Annu Rev Clin Psychol [Internet]. 2020 May 5 [cited 2024 Jul 3];16:351. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC7259820/.

- Powell-Wiley TM, Baumer Y, Baah FO, Baez AS, Farmer N, Mahlobo CT, et al. Social Determinants of Cardiovascular Disease. Circ Res [Internet]. 2022 Mar 4 [cited 2024 Jul 2];130(5):782–99. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35239404/.

- Chait A, den Hartigh LJ. Adipose Tissue Distribution, Inflammation and Its Metabolic Consequences, Including Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease. Front Cardiovasc Med [Internet]. 2020 Feb 25 [cited 2024 Jul 3];7. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32158768/.

- Mandelbaum J, Harrison SE. Perceived challenges to implementing childhood obesity prevention strategies in pediatric primary care. SSM - Qualitative Research in Health. 2022 Dec 1;2:100185.

- Aparicio E, Canals J, Arija V, De Henauw S, Michels N. The role of emotion regulation in childhood obesity: implications for prevention and treatment. Nutr Res Rev [Internet]. 2016 Jun 1 [cited 2024 Jul 3];29(1):17–29. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27045966/.

- Brown T, Moore TH, Hooper L, Gao Y, Zayegh A, Ijaz S, et al. Interventions for preventing obesity in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev [Internet]. 2019 Jul 23 [cited 2024 Jul 2];7(7). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31332776/.

- Wyatt KM, Lloyd JJ, Abraham C, Creanor S, Dean S, Densham E, et al. The Healthy Lifestyles Programme (HeLP), a novel school-based intervention to prevent obesity in school children: Study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2013 Apr 4;14(1).

- Marten KA, Allen DB, Rehm J, Vanderwall C, Peterson AL, Carrel AL. A Multidisciplinary Approach to Pediatric Obesity Shows Improvement Postintervention. Acad Pediatr [Internet]. 2023 Jul 1 [cited 2024 Jul 2];23(5):947–51. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36441091/.

- Rojo M, Lacruz T, Santos Solano |, Gutiérrez A, Sepúlveda AR, Sepulveda AR. Family-reported barriers and predictors of short-term attendance in a multidisciplinary intervention for managing childhood obesity: A psycho-family-system based randomised controlled trial (ENTREN-F) |. 2 | Montserrat Graell [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2024 Jul 2];3:4. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/erv.2913.

- Baygi F, Djalalinia S, Qorbani M, Larrabee Sonderlund A, Kousgaard Andersen MK, Thilsing T, et al. The effect of psychological interventions targeting overweight and obesity in school-aged children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2023 Dec 1 [cited 2024 Jul 2];23(1). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37537523/.

- Salam RA, Padhani ZA, Das JK, Shaikh AY, Hoodbhoy Z, Jeelani SM, et al. Effects of Lifestyle Modification Interventions to Prevent and Manage Child and Adolescent Obesity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients [Internet]. 2020 Aug 1 [cited 2024 Jul 2];12(8):1–23. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32722112/.

- Miri SF, Javadi M, Lin CY, Griffiths MD, Björk M, Pakpour AH. Effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy on nutrition improvement and weight of overweight and obese adolescents: A randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Metab Syndr [Internet]. 2019 May 1 [cited 2024 Jul 3];13(3):2190–7. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31235156/.

- M Bartelink NH, Mulkens S, Mujakovic S, J Jansen MW, J MW. Long-term effects of the RealFit intervention on self-esteem and food craving. Child Care in Practice [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2024 Jul 3];24(1):65–75. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=cccp20.

- Danielsen YS, Nordhus IH, Júlíusson PB, Mæhle M, Pallesen S. Effect of a family-based cognitive behavioural intervention on body mass index, self-esteem and symptoms of depression in children with obesity (aged 7-13): a randomised waiting list controlled trial. Obes Res Clin Pract [Internet]. 2013 Mar [cited 2024 Jul 2];7(2). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24331773/.

- Flores-Vázquez AS, Rodríguez-Rocha NP, Herrera-Echauri DD, Macedo-Ojeda G. A systematic review of educational nutrition interventions based on behavioral theories in school adolescents. Appetite [Internet]. 2024 Jan 1 [cited 2024 Jul 2];192. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37865297/.

- Sepúlveda AR, Santos Solano |, Blanco M, Lacruz T, Veiga | Oscar, Solano S. Feasibility, acceptability, and effectiveness of a multidisciplinary intervention in childhood obesity from primary care: Nutrition, physical activity, emotional regulation, and family. Eur Eat Disorders Rev [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2024 Jul 2];28:184–98. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/erv.2702.

- Oude Luttikhuis H, Baur L, Jansen H, Shrewsbury VA, O’Malley C, Stolk RP, et al. WITHDRAWN: Interventions for treating obesity in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019 Mar 7;3:CD001872.

- Rhee KE, Herrera L, Strong D, DeBenedetto AM, Shi Y, Boutelle KN. Design of the GOT Doc study: A randomized controlled trial comparing a Guided Self-Help obesity treatment program for childhood obesity in the primary care setting to traditional family-based behavioral weight loss. Contemp Clin Trials Commun [Internet]. 2021 Jun 1 [cited 2024 Jul 2];22. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33997462/.

- Cole TJ, Lobstein T. Extended international (IOTF) body mass index cut-offs for thinness, overweight and obesity. Pediatr Obes [Internet]. 2012 [cited 2024 Jul 2];7(4):284–94. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22715120/.

- Bornstein, MH. The SAGE Encyclopedia of Lifespan Human Development. The SAGE Encyclopedia of Lifespan Human Development. 2018 Mar 27;

- Garcidueñas-Fimbres TE, Gómez-Martínez C, Pascual-Compte M, Jurado-Castro JM, Leis R, Moreno LA, et al. Adherence to a healthy lifestyle behavior composite score and cardiometabolic risk factors in Spanish children from the CORALS cohort. Eur J Pediatr. 2024 Apr 1;183(4):1819–30.

- VanItallie TB, Yang MU, Heymsfield SB, Funk RC, Boileau RA. Height-normalized indices of the body’s fat-free mass and fat mass: potentially useful indicators of nutritional status. Am J Clin Nutr [Internet]. 1990 [cited 2024 Jul 3];52(6):953–9. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2239792/.

- Manual de Nutrición Coordinadores: Comité de Nutrición y Lactancia Materna de la AEP. [cited 2024 Jul 3]; Available from: www.luaediciones.com.

- ¿Qué es? - Fundación Iberoamericana de Nutrición [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jul 8]. Available from: https://www.finut.org/evalfinut/.

- Martin-moreno JM, Boyle P, Gorgojo L, Maisonneuve P, Fernandez-rodriguez JC, Salvini S, et al. Development and Validation of a Food Frequency Questionnaire in Spain. Int J Epidemiol [Internet]. 1993 Jun 1 [cited 2024 Jul 3];22(3):512–9. [CrossRef]

- Martín-García M, Vila-Maldonado S, Rodríguez-Gómez I, Faya FM, Plaza-Carmona M, Pastor-Vicedo JC, et al. The Spanish version of the Three Factor Eating Questionnaire-R21 for children and adolescents (TFEQ-R21C): Psychometric analysis and relationships with body composition and fitness variables. Physiol Behav [Internet]. 2016 Oct 15 [cited 2024 Jul 3];165:350–7. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27538345/.

- Caprara GV, Di Giunta L, Eisenberg N, Gerbino M, Pastorelli C, Tramontano C. Assessing Regulatory Emotional Self-Efficacy in Three Countries. Psychol Assess [Internet]. 2008 Sep [cited 2024 Jul 3];20(3):227. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC2713723/.

- Sanmartín R, Vicent M, Gonzálvez C, Inglés CJ, Díaz-Herrero Á, Granados L, et al. Positive and Negative Affect Schedule-Short Form: Factorial Invariance and Optimistic and Pessimistic Affective Profiles in Spanish Children. Front Psychol [Internet]. 2018 Mar 23 [cited 2024 Jul 3];9(MAR). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29628906/.

- Atienza FL, Pons D, Balaguer I, García- Merita M. Propiedades Psicométricas de la Escala de Satisfacción con la Vida en Adolescentes | Psicothema. Psicthrma [Internet]. 2000 [cited 2024 Jul 3];314–9. Available from: https://reunido.uniovi.es/index.php/PST/article/view/7597.

- Wood C, Griffin M, Barton J, Sandercock G. Modification of the Rosenberg Scale to Assess Self-Esteem in Children. Front Public Health [Internet]. 2021 Jun 17 [cited 2024 Jul 3];9. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34222169/.

- Mosqueda Díaz A, Mendoza Parra S, Jofré Aravena V, Barriga OA. Validez y confiabilidad de una escala de apoyo social percibido en población adolescente. Enfermería Global [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2024 Jul 3];14(39):125–36. Available from: https://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1695-61412015000300006&lng=es&nrm=iso&tlng=es.

- Villaécija J, Luque B, Martínez S, Castillo-Mayén R, Cuadrado E, Domínguez-Escribano M, et al. Perceived social support and healthy eating self-efficacy on the well-being of children and adolescents. Revista Iberoamericana de Psicologia y Salud. 2022;13(1):56–72.

- Mahmood L, Flores-Barrantes P, Moreno LA, Manios Y, Gonzalez-Gil EM. The influence of parental dietary behaviors and practices on children’s eating habits. Nutrients [Internet]. 2021 Apr 1 [cited 2024 Jul 2];13(4):1138. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/13/4/1138/htm.

- Sagui-Henson SJ, Armstrong LM, Mitchell AD, Basquin CA, Levens SM. The Effects of Parental Emotion Regulation Ability on Parenting Self-Efficacy and Child Diet. J Child Fam Stud. 2020 Aug 1;29(8):2290–302.

- López-Gómez I, Hervás G, Vázquez C. Adaptación de las “escalas de afecto positivo y negativo” (PANAS) en una muestra general española. Psicol Conductual [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2024 Jul 3];23:529–48. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/289993251_An_adaptation_of_the_Positive_and_Negative_Affect_Schedules_PANAS_in_a_Spanish_general_sample.

- Anderson E S, Winett R A, Wojcik J R. Social-cognitive determinants of nutrition behavior among supermarket food shoppers: a structural equation analysis - PubMed. Health Psychol [Internet]. 2000 [cited 2024 Jul 3];5:479–86. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11007156/.

- Jimeno-Martínez A, Maneschy I, Moreno LA, Bueno-Lozano G, De Miguel-Etayo P, Flores-Rojas K, et al. Reliability and Validation of the Child Eating Behavior Questionnaire in 3- to 6-Year-Old Spanish Children. Front Psychol [Internet]. 2022 May 4 [cited 2024 Jul 3];13. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35602745/.

- Cuadrado E, Gutiérrez-Domingo T, Castillo-Mayen R, Luque B, Arenas A, Taberneroa C. The Self-Efficacy Scale for Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet (SESAMeD): A scale construction and validation. Appetite [Internet]. 2018 Jan 1 [cited 2024 Jul 3];120:6–15. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28823625/.

- Safe Creative: Obra #2007144741729 - PinPo [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jul 8]. Available from: https://www.safecreative.org/work/2007144741729-pinpo.%20PinPo.%20Programa%20de%20intervenci%C3%B3n%20grupal%20para%20el%20tratamiento%20de%20la%20obesidad%20infantil.%20Literary%20work%20registry.%20Jun%202020.%20Accessed%2001%20July%202024.?0.

- Ehrenreich-May J, Kennedy SM, Sherman JA, Bilek EL, Barlow DH. Protocolo unificado para el tratamiento transdiagnóstico de los trastornos emocionales en niños - Ediciones Pirámide [Internet]. Piramide; 2022 [cited 2024 Jul 3]. Available from: https://www.edicionespiramide.es/libro/manuales-practicos/protocolo-unificado-para-el-tratamiento-transdiagnostico-de-los-trastornos-emocionales-en-ninos-jill-ehrenreich-may-9788436844344/.

- Sandín B, García-Escalera J, Valiente RM, Espinosa V, Chorot P. Clinical Utility of an Internet-Delivered Version of the Unified Protocol for Transdiagnostic Treatment of Emotional Disorders in Adolescents (iUP-A): A Pilot Open Trial. Int J Environ Res Public Health [Internet]. 2020 Nov 2 [cited 2024 Jul 3];17(22):1–17. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33182711/.

- MacHt M, Simons G. Emotional eating. Emotion Regulation and Well-Being. 2011;281–95.

- Michels N, Sioen I, Braet C, Eiben G, Hebestreit A, Huybrechts I, et al. Stress, emotional eating behaviour and dietary patterns in children. Appetite [Internet]. 2012 Dec [cited 2024 Jul 3];59(3):762–9. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22918173/.

- Vanhelst J, Deken V, Boulic G, Raffin S, Duhamel A, Romon M. Trends in prevalence of childhood overweight and obesity in a community-based programme: The VIF Programme. Pediatr Obes. 2021 Jul 1;16(7).

- Sal S, Bektas M. Effectiveness of Obesity Prevention Program Developed for Secondary School Students. Am J Health Educ [Internet]. 2022 Jan 2 [cited 2024 Jul 2];53(1):45–55. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/19325037.2021.2001774.

- Vinck J, Brohet C, Roillet M, Dramaix M, Borys JM, Beysens J, et al. Downward trends in the prevalence of childhood overweight in two pilot towns taking part in the VIASANO community-based programme in Belgium: Data from a national school health monitoring system. Pediatr Obes. 2016 Feb 1;11(1):61–7.

- de Melo JMM, Dourado BLLFS, de Menezes RCE, Longo-Silva G, da Silveira JAC. Early onset of overweight among children from low-income families: The role of exclusive breastfeeding and maternal intake of ultra-processed food. Pediatr Obes [Internet]. 2021 Dec 1 [cited 2024 Jul 2];16(12). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34169658/.

- Gibson-Moore H, Chambers L. Sleep matters: Can a good night’s sleep help tackle the obesity crisis? Nutr Bull [Internet]. 2019 Jun 1 [cited 2024 Jul 2];44(2):123–9. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/nbu.12386.

- Davison GM, Fowler LA, Ramel M, Stein RI, Conlon RPK, Saelens BE, et al. Racial and socioeconomic disparities in the efficacy of a family-based treatment programme for paediatric obesity. Pediatr Obes [Internet]. 2021 Oct 1 [cited 2024 Jul 2];16(10). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33847074/.

- Conrey SC, Burrell AR, Brokamp C, Burke RM, Couch SC, Niu L, et al. Neighbourhood socio-economic environment predicts adiposity and obesity risk in children under two. Pediatr Obes [Internet]. 2022 Dec 1 [cited 2024 Jul 2];17(12). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36350200/.

- Scaglioni S, De Cosmi V, Ciappolino V, Parazzini F, Brambilla P, Agostoni C. Factors Influencing Children’s Eating Behaviours. Nutrients [Internet]. 2018 Jun 1 [cited 2024 Jul 2];10(6). Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC6024598/.

- Lloyd J, McHugh C, Minton J, Eke H, Wyatt K. The impact of active stakeholder involvement on recruitment, retention and engagement of schools, children and their families in the cluster randomised controlled trial of the Healthy Lifestyles Programme (HeLP): A school-based intervention to prevent obesity. Trials. 2017 Aug 14;18(1).

- Verónica Marín B, Lorena Rodríguez O, Roxana Buscaglione A, María Luis Aguirre C, Raquel Burrows A, María Isabel Hodgson B, et al. MINSAL-FONASA Pilot Study in obese children and adolescents. Rev Chil Pediatr [Internet]. 2011 [cited 2024 Jul 2];82(1):21–8. Available from: http://www.scielo.cl/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0370-41062011000100003&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=es.

- Gago C, Aftosmes-Tobio A, Beckerman-Hsu JP, Oddleifson C, Garcia EA, Lansburg K, et al. Evaluation of a cluster-randomized controlled trial: Communities for Healthy Living, family-centered obesity prevention program for Head Start parents and children. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2023 Dec 1;20(1).

- Chai LK, Farletti R, Fathi L, Littlewood R. A Rapid Review of the Impact of Family-Based Digital Interventions for Obesity Prevention and Treatment on Obesity-Related Outcomes in Primary School-Aged Children. Nutrients [Internet]. 2022 Nov 1 [cited 2024 Jul 3];14(22). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36432522/.

- Viitasalo A, Eloranta AM, Lintu N, Väistö J, Venäläinen T, Kiiskinen S, et al. The effects of a 2-year individualized and family-based lifestyle intervention on physical activity, sedentary behavior and diet in children. Prev Med (Baltim). 2016 Jun 1;87:81–8.

- Jacobs J, Strugnell C, Allender S, Orellana L, Backholer K, Bolton KA, et al. The impact of a community-based intervention on weight, weight-related behaviours and health-related quality of life in primary school children in Victoria, Australia, according to socio-economic position. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2021 Dec 1 [cited 2024 Jul 2];21(1). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34837974/.

- Jakobsen DD, Brader L, Bruun JM. Effect of a higher protein diet and lifestyle camp intervention on childhood obesity (The COPE study): results from a nonrandomized controlled trail with 52-weeks follow-up. Eur J Nutr [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2024 Jul 2]; Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38724826/.

- Resnicow K, Delacroix E, Sonneville KR, Considine S, Grundmeier RW, Di Shu, et al. Outcome of BMI2+: Motivational Interviewing to Reduce BMI Through Primary Care AAP PROS Practices. Pediatrics [Internet]. 2024 Feb 1 [cited 2024 Jul 2];153(2). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38282541/.

- Rifas-Shiman SL, Taveras EM, Gortmaker SL, Hohman KH, Horan CM, Kleinman KP, et al. Two-year follow-up of a primary care-based intervention to prevent and manage childhood obesity: the High Five for Kids study. Pediatr Obes [Internet]. 2017 Jun 1 [cited 2024 Jul 3];12(3):e24–7. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27231236/.

- Else V, Chen Q, Cortez AB, Koebnick C. Effectiveness of a Family-Centered Pediatric Weight Management Program Integrated in Primary Care - PubMed. Perm J [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2024 Jul 3]; Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33635768/.

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev [Internet]. 1977 [cited 2024 Jul 3];84(2):191–215. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/847061/.

- Ames GE, Heckman MG, Diehl NN, Grothe KB, Clark MM. Further statistical and clinical validity for the Weight Efficacy Lifestyle Questionnaire-Short Form. Eat Behav [Internet]. 2015 Aug 1 [cited 2024 Jul 3];18:115–9. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26042918/.

- Ruiz LD, Zuelch ML, Dimitratos SM, Scherr RE. Adolescent Obesity: Diet Quality, Psychosocial Health, and Cardiometabolic Risk Factors. Nutrients [Internet]. 2019 Jan 1 [cited 2024 Jul 3];12(1). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31877943/.

- Lee EY, Yoon KH. Epidemic obesity in children and adolescents: risk factors and prevention. Front Med [Internet]. 2018 Dec 1 [cited 2024 Jul 3];12(6):658–66. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30280308/.

- Skelton JA, Vitolins M, Pratt KJ, DeWitt LH, Eagleton SG, Brown C. Rethinking family-based obesity treatment. Clin Obes [Internet]. 2023 Dec 1 [cited 2024 Jul 3];13(6). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37532265/.

- Yackobovitch-Gavan M, Wolf Linhard D, Nagelberg N, Poraz I, Shalitin S, Phillip M, et al. Intervention for childhood obesity based on parents only or parents and child compared with follow-up alone. Pediatr Obes [Internet]. 2018 Nov 1 [cited 2024 Jul 3];13(11):647–55. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29345113/.

- Azevedo LB, Stephenson J, Ells L, Adu-Ntiamoah S, DeSmet A, Giles EL, et al. The effectiveness of e-health interventions for the treatment of overweight or obesity in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev [Internet]. 2022 Feb 1 [cited 2024 Jul 3];23(2). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34747118/.

- Tate EB, Spruijt-Metz D, O’Reilly G, Jordan-Marsh M, Gotsis M, Pentz MA, et al. mHealth approaches to child obesity prevention: successes, unique challenges, and next directions. Transl Behav Med [Internet]. 2013 Dec [cited 2024 Jul 3];3(4):406. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC3830013/.

- Tozzi F, Nicolaidou I, Galani A, Antoniades A. eHealth Interventions for Anxiety Management Targeting Young Children and Adolescents: Exploratory Review. JMIR Pediatr Parent [Internet]. 2018 Jan 1 [cited 2024 Jul 3];1(1). Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC6716078/.

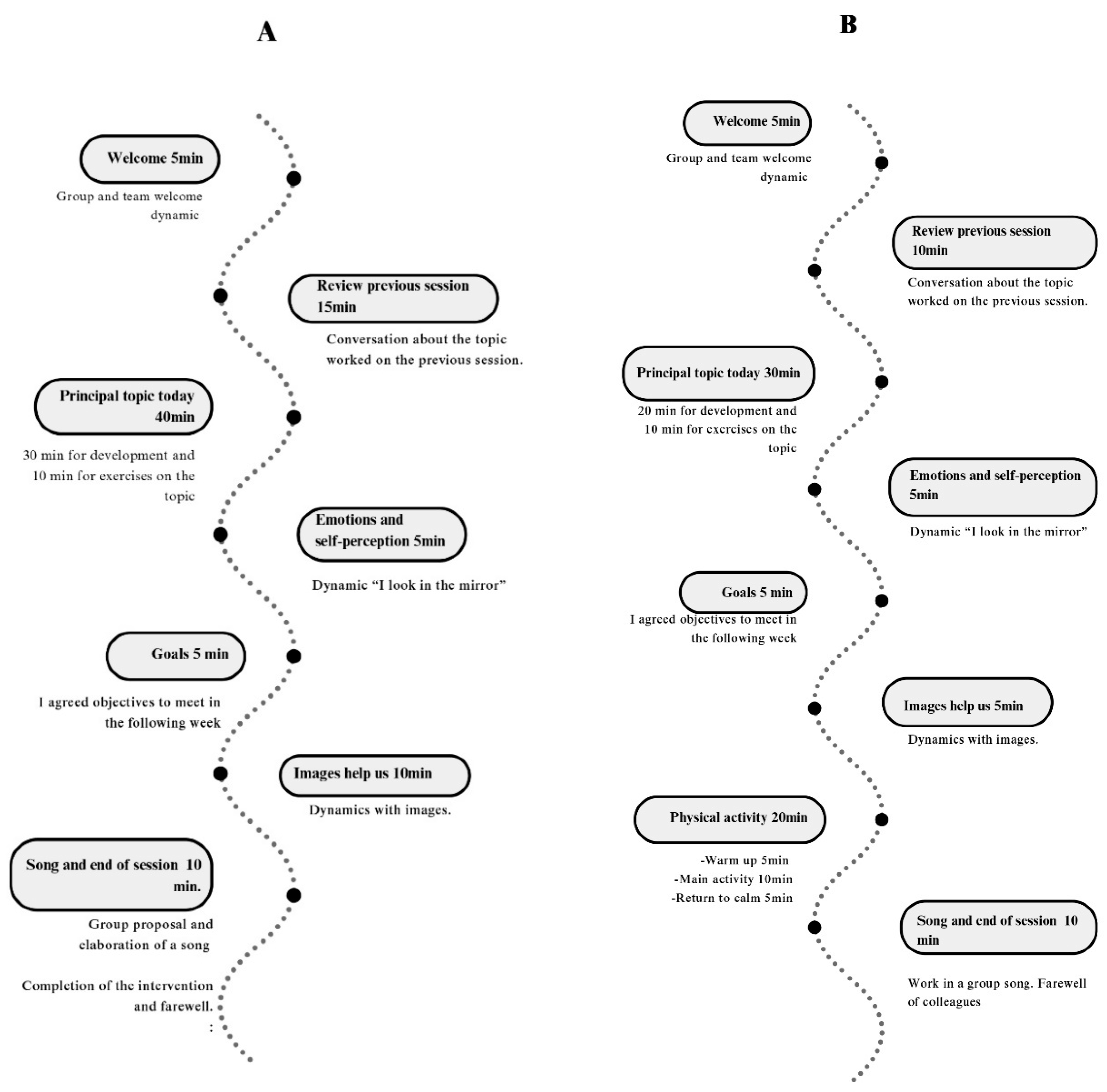

| PinPo Sessions | Main topic | We look in the mirror | Images help us | Physical activity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SESSION 1 Knocking on the door. Will you open me? | -Healthy breakfast. -Food traffic light. -Hand method for food quantities |

-Quiz about breakfast. -Self-criticism and reflection about feelings. |

-Photograph of the pantry and refrigerator for the next session. | -Games with toy food. |

| SESSION 2 My five stars, my five meals. | -Traffic light and breakfast review. -The importance of the five meals. -Our body image. |

-Daily food record. -Write foods and quantities for a day. -Indicate the ultra-limited foods consumed. |

-Check photographs of the pantry and refrigerator. - Sort photos by food groups |

-Carrer. -Vertical jump. |

| SESSION 3 My friends, recess, the park and sports. | - Review of 5 meals and breakfast. -Types and frequency of exercise. -Mid-morning meals and snacks. |

-Record on PA of all family members. | -Search information about traditional games -Attend a friend or family member’s training or match. |

-Relay and cooperative games with balls |

| SESSION 4 My colorful friends, fruits and vegetables. | -Review of 5 meals, breakfast and physical activity. -Importance of fruit and vegetable consumption. -Food composition. |

- Write down the number of fruits and vegetables consumed in a day. | -Review the menus prior to starting the program. -Take photos of menus for the next session. |

-Games with balloons. |

| SESSION 5 Knowing nutrients, my new way of cooking. | -Nutritional labels. -Nutritional traffic light. -Content of main meal and dinners. -Ways of cooking. |

-Answer and debate the questions in this section. -Complete table on the nutrients of traditional meals. |

-Check photos of meals and write down the number of colors. -Bring food labels to analyze in the next session. |

-Games and exercises in pairs with tennis balls. |

| SESSION 6 My inner self: self-esteem. | -Self-esteem. Importance of expressing feelings -Types of communication |

-Self-criticism and debate on issues related to self-esteem and emotional regulation. | -Analyze the labels that we have brought from home. | -Individual challenges: exercises on the floor and with a chair. -Group challenges: races in pairs, balloon transfers. |

| SESSION 7 Obstacles, relapses… I am going to build. | -Recognize our feelings and express them. -Mediterranean diet -Food pyramid. |

-Test of adherence to the Mediterranean diet. | -Analyze food pyramid and healthy habits. |

-Animal Flow: Make movements of each animal. |

| SESSION 8 My new resolutions with my new friends. | -Relapses -School bullying -Motivation |

-Importance of meeting objectives. -Achievable goals. -Assess the small changes. |

-Stages of change test. | -Traditional games. |

| SESSION 9 My new resolutions with my new friends. | -Reflect on the achievements achieved at an individual level. -Importance of planning the menu. |

-Knowledge test of the PinPo program. |

-Write physical and psychological evolution throughout the development of the program. | -Presentation of the gamification program. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).