Introduction

Healthy wildlife populations are the foundation for wildlife conservation, ecosystem services maintenance, income generation (e.g., ecotourism), food security, and the achievement of One Health (OH) objectives [

1,

2,

3]. Wildlife serve as important reservoir for many endemic or (re-)emerging infectious diseases that affect people and livestock. For example, the recent emergence and global spread of the high pathogenicity avian influenza H5N1 virus from clade 2.3.4.4b, has greatly impacted the poultry sector and wild birds and mammals globally [

4]. Large-scale amplification and circulation of this virus within and between poultry and wildlife has increased spillovers to mammalian hosts, including humans, illustrating a complex ensemble of conservation, livestock health, and public health issues [

5]. Human activities and continued encroachment into natural areas affect climate, landscape structures and connectivity, habitat availability, water and soil quality, and patterns of species interactions, challenging the existence of wildlife species [

6,

7]. This loss of ecological integrity can threaten human health, with wildlife species often acting as early indicators and sentinels, but information is often lacking on biotic, abiotic, and anthropogenic drivers of wildlife and human health. In fact, a proposed “continuum of care” socio-ecological model of public health includes ecosystem integrity as a key upstream determinant, and nature protection as an essential intervention point for public health [

8,

9,

10].

A fuller understanding and appropriate management of these complex OH issues require integrated wildlife health (WH) intelligence, especially across political borders. However, coordinated and systematic wildlife health surveillance (WHS) is globally lacking. Countries have significant disparities in the development of their WHS systems. Among 107 countries surveyed, 58% demonstrated no evidence of a functional WHS program [

11]. Only a few high-income countries maintain established, nationwide, and centralized programs, and even in those cases, funding for WHS fluctuates in response to successive livestock or public health crises. Most low-and-middle income countries (LMIC) have limited capacity beyond sporadic surveillance with foreign funding or support often restricted in scope and duration [

12].

Since 2011, the World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH) and its WOAH Working Group on Wildlife, has shepherded the global standardization and coordination of WHS, through the designation of national wildlife focal points who report wildlife disease events to WOAH’s ‘WAHIS Wild’ database via national delegates [

1,

13]. In 2021, WOAH released a WH framework that reinforced its commitment to supporting WHS globally, and to further integrate WHS into OH strategies. Moreover, WHS would further support WHO's pandemic preparedness framework that identifies actions for pre-epidemic preparedness, alert, outbreak response and post-epidemic evaluation. Despite these and other activities, WOAH has been limited in supporting WHS implementation at sub-national to national scales, due to the lack of field-level networks to support implementation of WHS. Most countries have not allocated human and financial resources for WH and institutional mandates for WHS either do not exist or fail to maximize intelligence across institutions. This represents a major gap in the ability to generate WH intelligence globally [

14]. Therefore, current top-down approaches should be complemented with bottom-up processes and other grounded approaches (side-to-side and inside-out approaches) to enhance national coordinated initiatives and mainstream WHS systems [

11].

The Science for Nature and People Partnership (SNAPP) funded the creation of a working group (WG), to strengthen WHS globally through a collaborative and evidence-based approach [

10]. This WG comprises representatives of international, national, and local organizations with the goal of addressing the gap between global coordination and local implementation and identifying ways to encourage consistent and effective WHS practices at the national and global levels. This WG was founded on the premises that growing national WHS across the globe is beyond the scope of a single institution, a consortium approach would better address these challenges, and cross-sectoral and trans-disciplinary methods are needed to implement sustainable WHS systems. One of the main objectives of this WG is to identify practical pathways to implementation. Here, we present a Theory of Change (ToC) to address the gaps between global policy and local-to-national implementation of WHS.

Methods

The development of a ToC is a participatory process in which a group of stakeholders and rightsholders reflect on their collective aims and the expected outcomes and impacts of their actions and describe how their activities will eventually lead to these desired outcomes and impacts [

15]. The ToC is a roadmap illustrating our working group’s assumptions about how a set of interventions will lead to specific changes. The WG developed a ToC to address the WHS implementation gap following six steps (

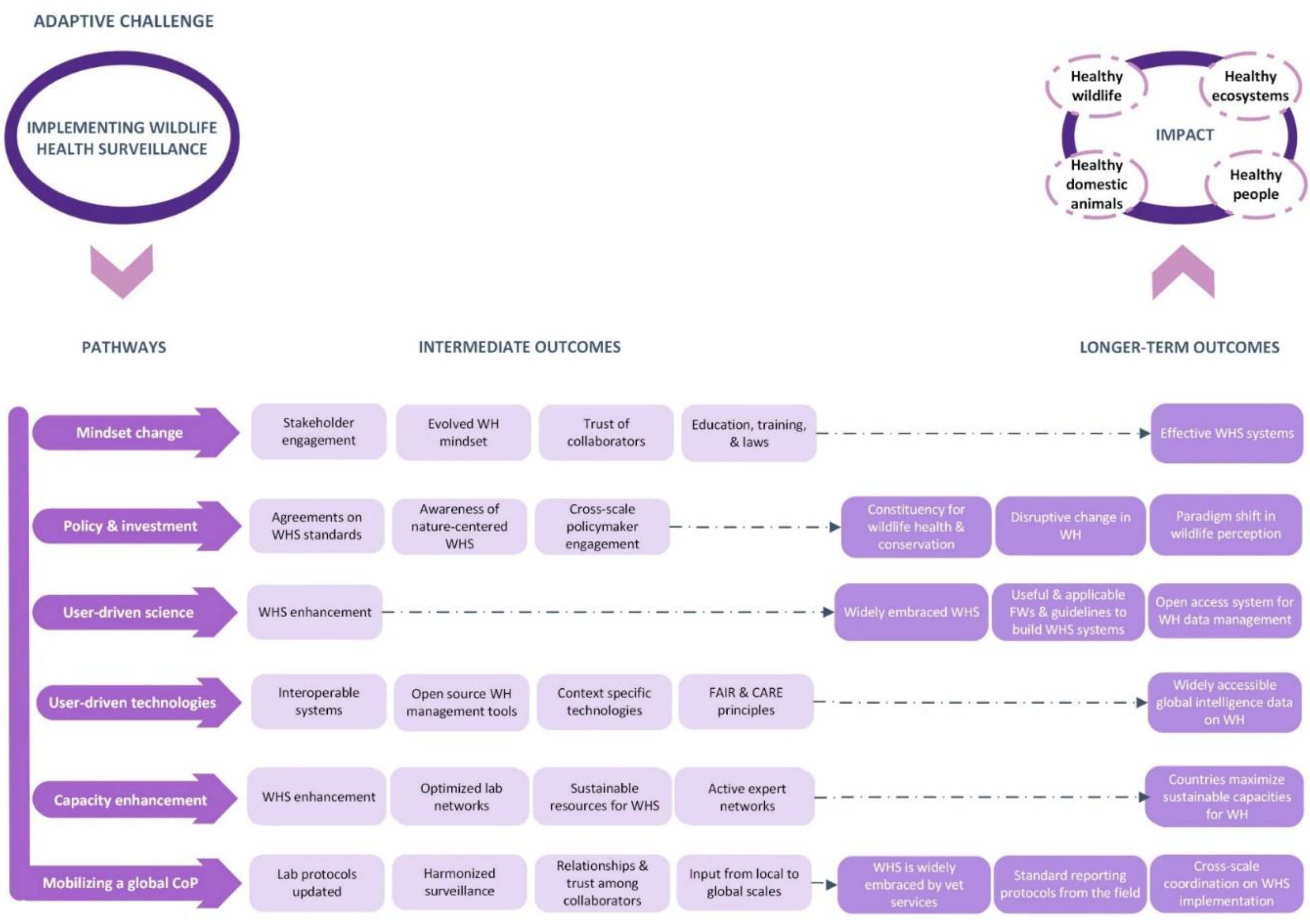

Figure 1).

The WG developed the final ToC (

Figure 2) over two virtual workshops (4-hours each), a 3-day in-person workshop facilitated by a professional and experienced facilitator (CK), additional online debriefing sessions, and multiple rounds of drafting. Each step involved various activities including individual reflection, group discussions, or plenary exercise.

Results

Adaptive Challenge

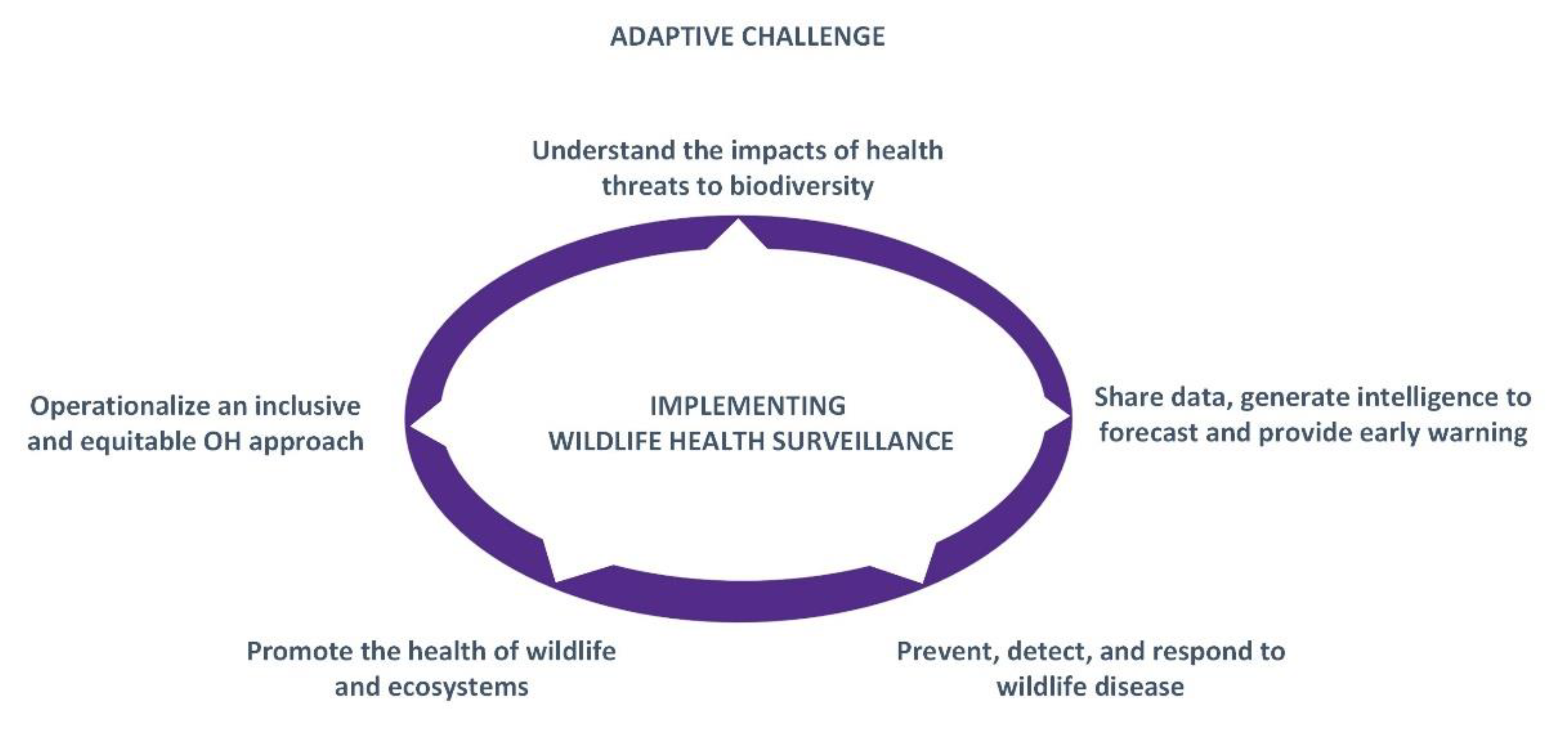

Adaptive challenges are issues resulting from complex dynamics that require a collaborative learning process and a mindset shift, rather than an expertise-guided technical solution [

16]. The group focused on the adaptive challenge of bridging the WHS implementation gap (

Figure 3) to “enhance capacity for coordinated and effective WHS systems to support adaptive management across scales and sectors.”

Barriers to Implementation

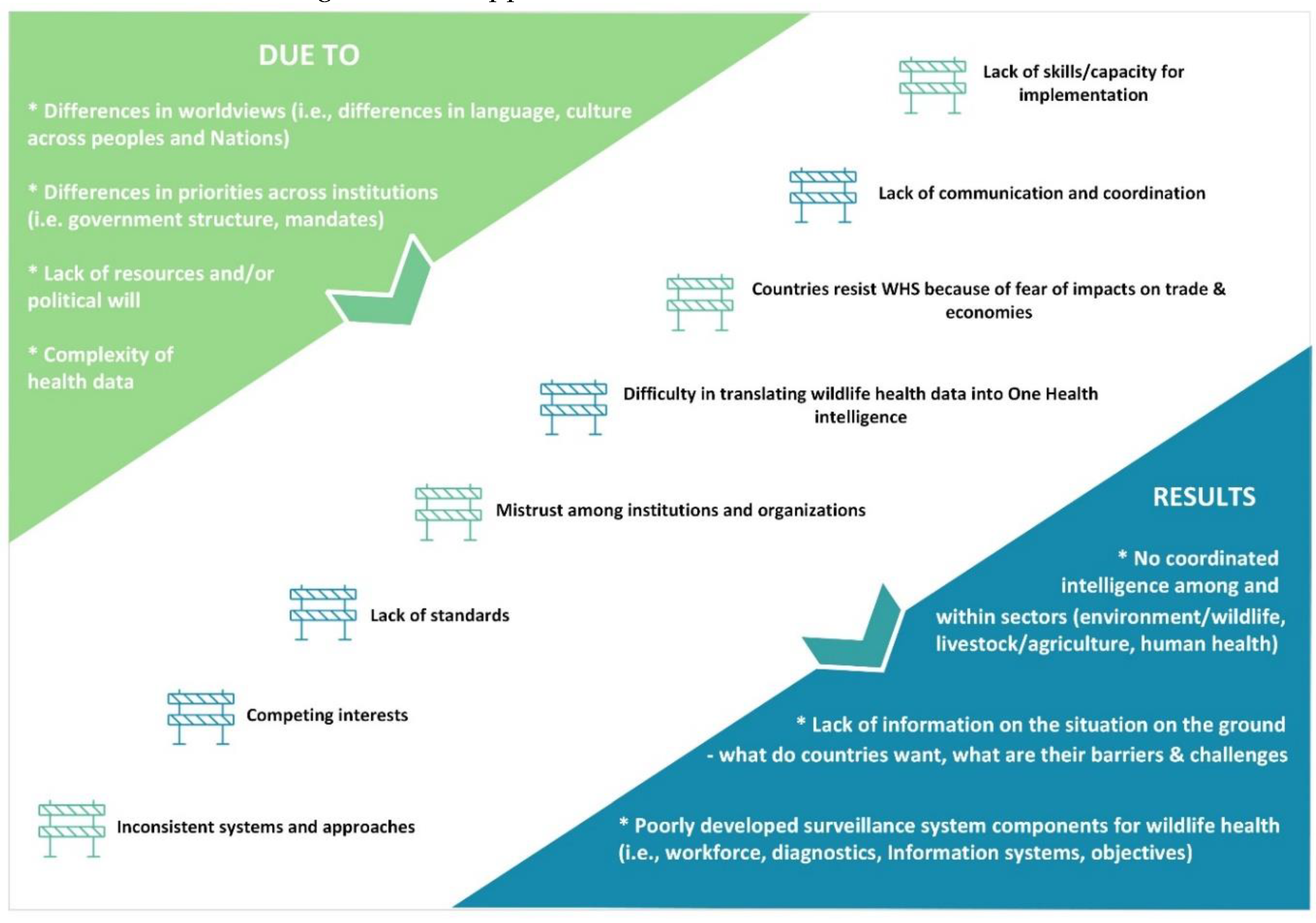

Barriers are a result of conflicting priorities between government sectors or worldviews, as well as resource and data complexity challenges (

Figure 4). Government entities’ abilities to lead WHS may be limited because of legal or funding restrictions, or the absence of an underlying mandate for WHS or appropriate expertise. Animal health mandates are usually within veterinary services, whose main priorities are determined by a limited number of economically important species. On one hand, this results in low WHS prioritization compared to other animal health priorities. On the other hand, it reduces incentives to transparently report WH intelligence because of perceived negative economic consequences and trade impacts. In this context, wildlife is perceived as a threat (source of diseases), rather than a resource to be conserved for the greater good. Traditionally the environmental sector has had limited awareness of and influence on livestock and public health decisions. As a result, WHS priorities have mainly been defined from a human and agriculture-centered standpoint without considering the inherent value of wildlife, biodiversity, and ecosystems. The lack of institutional support for WHS has caused poor prioritization of sustained WHS efforts despite its critical importance to operationalizing One Health.

As single institutions rarely hold the sole mandate for WHS, multi-institution collaborative approaches are needed for implementation, which requires adequate communication coordination, and collaboration mechanisms [

12]. This can be further complicated when national and subnational levels of government operate under different regulations and policies. The complexity of WHS data and the lack of standards result in inconsistent systems that hinder the sharing of information, and coordination across sectors and scales. As a result, significant barriers prevent generation of coordinated WHS intelligence that supports One Health action.

Pathways of Change

Six pathways were identified: mindset change, policy and investment, user-driven science, user-driven technologies, and capacity enhancement, all supported by the mobilization of a global community of practice. Activities identified for each pathway are shown in

Table 1.

Mindset Change

Mindset changes underpin every pathway of the ToC. Three strategies of mindset change were highlighted. First, there is a need to understand and communicate the value of WHS as a benefit and not just as a cost (e.g. cost of trade impacts). Economic analyses should be a core activity of this pathway (e.g., Natural Capital Project), making a business case for WHS, including the non-market value of wildlife like willingness to pay for WH or ecosystem services that incorporate the intrinsic value of wildlife. Second, there is a need to move beyond the utilitarian and human-centered perception of wildlife and WHS, and fully integrate the intrinsic value of wildlife in decisions and prioritization of WHS. In that nature-centered paradigm, WHS incorporates drivers of disease and their effects on wildlife populations and encourages the connection of WHS systems with ecological monitoring programs for comprehensive monitoring of environmental changes. Third, the WG reflected on decolonizing our approach to global cooperation on WHS, and the requirement for cultural humility in addressing questions of wildlife value and WHS [

18,

19]. Creating relationships among diverse groups, peoples, and Nations is critical to create the ethical space where multiple worldviews can be represented, heard, and respected. This is essential as national governments engage with Indigenous Nations on the co-design and co-management of WHS programs, under the guiding principles of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) [

20].

Policy and Investment

This pathway focuses on growing political will for WHS by fostering policy changes, allocating adequate funding and investment, and incentivizing health hazard detection. Political support for sustainable WHS can benefit from both top-down and bottom-up approaches. At the global level, the wildlife health framework developed by WOAH and other tools (e.g. Joint External Evaluation [JEE], the WOAH Performance of Veterinary Service [PVS]) encourage and guide countries to implement WHS but are not legally binding and do not provide a clear pathway to national and local implementation. The WOAH guidelines on wildlife surveillance offer practical recommendations for national implementation, albeit without an enforcement mechanism. Opportunities exist (e.g., the Pandemic Prevention Treaty, the pending 2005 WHO International Health Regulation [IHR] updates) to more strongly mandate the development and maintenance of WHS as part of coordinated multisectoral surveillance, such as those in place for livestock and human health [

11,

21,

22]. At the national level, the adoption of standard operating procedures is essential to provide bottom-up policy incentives to sustainably implement such surveillance.

Locally relevant prioritization of WHS objectives (i.e. engaging local stakeholders and rightsholders, making them responsible “stake sharers”) along with stronger assessment of the value of functional WHS systems would further incentivize local implementation and investments. However, the global nature of drivers of WH warrants a strong role for global cooperation in the funding of country-level WHS systems and moving away from short-term project funding. A challenge to address is ensuring that both spatial and temporal scales of national and global investments are compatible with the generation of WH intelligence that benefit local and global communities.

User-Driven Science

Data synthesis, research, and knowledge sharing activities are fundamental to supporting science-based decisions and tools for WHS. A concerted focus on developing evidence and sharing scientific resources for WHS is needed, particularly in the following subject areas: economics or cost-benefit analyses, prioritization of surveillance efforts, assessment of existing WHS resources, development of performance metrics, and political science research for policy gaps and governance. There is also a need for science to facilitate the building of useful public data collection tools to better incorporate local knowledge sourced from community, citizen, or student-based networks, which can enhance data from government-led efforts [

23].

User-Driven Technologies

This pathway addresses flexible and scalable technologies needed to improve WHS implementation. The need for standardized and open-source data collection and management tools has been a strong force driving collaboration between WG members. WH information sharing remains hamstrung by institutions largely operating data systems in isolation and constrained by sensitivities related to data sharing. Reducing data siloes will help operationalize WHS and One Health. Here, appropriate technology developed through participatory and collaborative approaches can provide reliable standard open-source data management solutions that enable information sharing and greater interoperability of existing systems. Advancements in artificial intelligence could also contribute to making information more accessible. The ultimate goal is for user-driven technology to provide richer information and intelligence about WH for decision makers and managers of wildlife.

Capacity Enhancement

This pathway explores how to mobilize existing workforces and enhance the skills, knowledge, and capacity for WHS. Developing and consolidating training materials that are locally relevant and tailored to the different roles within the WHS system are critical to implementation. Delivery of training requires institutions and actors that are firmly embedded in the local context. As such, connecting international and local WHS actors and organizations will be instrumental in the development of sustainable capacity building models. Facilitating access to training materials through e-learning platforms in multiple languages would benefit WHS implementation. Finally, even with adequate training, responding to large-scale wildlife health emergencies can be a challenge for newly formed WHS systems, and this capacity can be enhanced by the support and mentoring of a global network.

Aims and Expected Impacts

The mission of WHIN is to establish a CoP that works collaboratively on WHS so that it is implemented everywhere, at all times, particularly where it matters most, such as vulnerable populations, and threatened biodiversity. WHIN seeks to grow the CoP and over the longer-term WHIN aims for the majority of countries to have effective WHS systems, supported by comprehensive guidance and standards, open access to WH data management tools, and broad support for OH and conservation driven WHS. The impact of enhanced capacity for WHS at national scales, combined with effective coordination between global and local-national organizations and institutions, will be facilitated by WHIN’s CoP. The ultimate impact seeks sustainable and healthy ecosystems supporting abundant and diverse wildlife and sustainable human societies.

Discussion

Our ToC for implementing WHS provides a roadmap for strengthening national, and subsequently global, capacity to effectively prevent, monitor, and respond to WH threats. Through a focus on six pathways (mindset changes, policy and investment, user-driven science, user-driven technologies, capacity enhancement, and mobilizing a global CoP), this ToC delineates activities that will contribute to operationalizing WHS, thereby promoting wildlife and ecosystem health and reducing health risks at source (i.e., primary prevention) [

9]. This ToC highlights the importance of coordination and knowledge sharing across sectors among all stakeholders and rightsholders involved in WHS – from local field practitioners to global actors.

Establishing a CoP through WHIN can help achieve transformative change by bringing together multiple organizations, governments, local communities, and consolidating the expertise of scientists and practitioners at sub-national, national, and regional levels. Such a diverse group of institutions and voices working alongside each other to support WHS is best positioned to enhance the adoption and growth of WHS on the ground, by facilitating bottom-up, side-to-side, and inside-out approaches [

24].

This is the first ToC to articulate steps to support practical implementation of WHS across scales, bridging an important gap between global frameworks (e.g., WOAH’s Wildlife Health Framework [

23]) and local realities. Stronger WHS can help countries achieve coordinated multi-sectoral surveillance and capacity indicators across the IHR Joint External Evaluation (JEE) and WOAH’s Performance of Veterinary Service (PVS) Evaluation tool to address zoonotic disease emergence. This ToC further supports broader OH strategies outlined in OHHLEP’s One Health Theory of Change, the Quadripartite’s One Health Joint Plan of Action, the Global Health Security Agenda (GHSA), and the Convention on Biological Diversity Global Action Plan on Biodiversity and Health [

25,

26,

27,

28]. One of the most immediate implications of our ToC is the need for social, political, and technological advances in data and knowledge sharing. Creation of WH intelligence requires efficiencies of structured data, including a universal language for complex WH data that integrates the collaborative input of stakeholders and rightholders, and incremental steps to achieve greater data sharing (i.e., FAIR and CARE principles, DataOne) [

29].

There is a lack of transdisciplinary involvement, representation, and diversity in who currently advises and implements WHS, with the majority of established WHS systems and expertise in high-income countries [

30]. Despite efforts to diversify perspectives, our WG composition and the ToC we developed face the same limitation of representation, diversity, and transdisciplinary involvement. However, WHIN’s CoP approach aims to address these gaps in representation, reduce high-income country bias, and increase diversity and inclusion in global cooperation processes. WHIN is committed to cultural pluralism and supports the inclusion and leadership of Indigenous and LMIC members. We encourage readers interested in this initiative to get involved, as diverse and sustained support will be critical to success.

Moreover, WHIN’s consortium approach will require member organizations to support the common good despite potentially overlapping or even competing institutional mandates. Competing mandates likely influenced the development of this ToC and will likely continue to be a challenge for WHIN, particularly when leadership in an area is associated with increased funding opportunities. However, we hope that this collaborative approach will facilitate efficient and concerted use of limited resources, demonstrating benefits over competitive models. Shifting funding priorities towards collaborative models will be necessary to reduce competition between key actors. Furthermore, current funding mechanisms are fragmented, both in time and space, leaving few opportunities for sustainable and scalable impacts. Continuous evaluation and adaptation of this ToC will be crucial in response to the ever-evolving landscapes of WH and global cooperation.

This ToC offers an exciting vision for WHS, one in which WHS is expanded to respond to nature-centered priorities. WHS is needed to understand environmental drivers of WH, and how they influence conservation, and animal and public health. This is essential to ensure continued progress in operationalizing OH as most wildlife health initiatives remain focused on zoonotic diseases [

11]. The ToC underlines the importance of knowledge exchange, cooperation, and learning across all levels. Global WHS needs trust and collaboration among actors that engage and support countries in enhancing their WHS systems. The WHIN community of practice can link and leverage these efforts to scale WHS efficiently and globally. With a keen focus on capacity enhancement, standard development, research, data sharing, and advocating for wildlife, the ToC paves the way for tangible action to catalyze change. This proposal’s success will rely on our willingness to lean into a new collaborative and decolonized model of international cooperation for WHS.

Funding

Science for Nature and People Partnership (SNAPP).

Acknowledgments

We thank Amelie Arnecke, Keith Hamilton, Thierry Work, Susan Kutz, and Sophie Muset for their contributions.

Conflicts of Interest

The findings and conclusions in this manuscript are those of the authors and should not be construed to represent any official USDA or U.S. Government determination or policy.

References

- Buttke DE, Decker DJ, Wild MA. The role of One Health in wildlife conservation: a challenge and opportunity. J Wildl Dis 2015, 51, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter NH, Shrestha BK, Karki JB, Pradhan NMB, Liu J. Coexistence between wildlife and humans at fine spatial scales. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2012, 109, 15360–15365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen T, Murray KA, Zambrana-Torrelio C, et al. Global hotspots and correlates of emerging zoonotic diseases. Nat Commun 2017, 8, 1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charostad J, Rezaei Zadeh Rukerd M, Mahmoudvand S, et al. A comprehensive review of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) H5N1: An imminent threat at doorstep. Travel Med Infect Dis 2023, 55, 102638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verhagen JH, Fouchier RAM, Lewis N. Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza Viruses at the Wild–Domestic Bird Interface in Europe: Future Directions for Research and Surveillance. Viruses 2021, 13, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WOAH. Wildlife Diseases – Situation Report 3. https://www.woah.org/en/document/wildlife-diseases-situation-report-3/.

- World Health Organization, Convention on Biological Diversity. Connecting global priorities: biodiversity and human health: a state of knowledge review. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2015 https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/174012. (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- Kilanowski PhD R APRN, CPNP, FAAN,Jill F. Breadth of the Socio-Ecological Model. J Agromedicine 2017, 22, 295–297. [Google Scholar]

- Stephen C, Walzer C. The continuum of care as a unifying framework for intergenerational and interspecies health equity. Front Public Health 2023; 11. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1236569(accessed Jan 16, 2024).

- Lefrançois T, Malvy D, Atlani-Duault L, et al. After 2 years of the COVID-19 pandemic, translating One Health into action is urgent. The Lancet 2023, 401, 789–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machalaba C, Uhart M, Ryser-Degiorgis M-P, Karesh WB. Gaps in health security related to wildlife and environment affecting pandemic prevention and preparedness, 2007–2020. Bull World Health Organ, 2021;99: 342-350B.

- Pruvot M, Denstedt E, Latinne A, et al. WildHealthNet: Supporting the development of sustainable wildlife health surveillance networks in Southeast Asia. Sci Total Environ 2023, 863, 160748–160748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Organisation for Animal Health. Home. WOAH - World Organ. Anim. Health. https://www.woah.org/en/home/ (accessed Feb 26, 2024).

- Delgado M, Ferrari N, Fanelli A, et al. Wildlife health surveillance: gaps, needs and opportunities.

- Theory of Change. https://www.structural-learning.com/post/theory-of-change. (accessed on 17 January 2024).

- Multi-Stakeholder Decision Making for Complex Problems. https://www.worldscientific.com/worldscibooks/10.1142/9294#t=aboutBook. (accessed on 18 January 2024).

- Liz Paola NZ, Torgerson PR, Hartnack S. Alternative Paradigms in Animal Health Decisions: A Framework for Treating Animals Not Only as Commodities. Animals 2022, 12, 1845–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barroso P, Relimpio D, Zearra JA, et al. Using integrated wildlife monitoring to prevent future pandemics through one health approach. One Health 2023, 16, 100479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redvers N, Celidwen Y, Schultz C, et al. The determinants of planetary health: an Indigenous consensus perspective. Lancet Planet Health 2022, 6, e156–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples | Division for Inclusive Social Development (DISD). https://social.desa.un.org/issues/indigenous-peoples/united-nations-declaration-on-the-rights-of-indigenous-peoples. (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- Morner T, Obendorf DL, Artois M, Woodford MH. Surveillance and monitoring of wildlife diseases:. Rev Sci Tech OIE 2002, 21, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- dos, S. Ribeiro C, van de Burgwal LHM, Regeer BJ. Overcoming challenges for designing and implementing the One Health approach: A systematic review of the literature. One Health 2019, 7, 100085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephen C, Duff JP, Gavier-Widen D, et al. Proposed attributes of national wildlife health programmes: -EN- -FR- Attributs proposés pour des programmes nationaux de santé de la faune sauvage -ES- Características propuestas de los programas nacionales de sanidad de la fauna silvestre. Rev Sci Tech OIE 2018, 37, 925–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Top down, bottom up, side to side, inside out: 4 types of social change and why we need them all. The RSA. 2014; published online April 9. https://www.thersa.org/blog/2014/04/top-down-bottom-up-side-to-side-inside-out-4-types-of-social-change-and-why-we-need-them-all. (accessed on 23 October 2023).

- One health joint plan of action (2022‒2026): working together for the health of humans, animals, plants and the environment. https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789240059139. (accessed on 10 April 2024).

- One Health High-Level Expert Panel (OHHLEP), Adisasmito WB, Almuhairi S, et al. One Health: A new definition for a sustainable and healthy future. PLOS Pathog 2022, 18, e1010537. [Google Scholar]

- Biggs D, Cooney R, Roe D, et al. Developing a theory of change for a community-based response to illegal wildlife trade. Conserv Biol 2017, 31, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skinner D, Dublin H, Niskanen L, Roe D, Vishwanath A. Chapter 24 - Exploring community beliefs to reduce illegal wildlife trade using a theory of change approach. In: Challender DWS, Nash HC, Waterman C, eds. Pangolins. Academic Press, 2020: 385–93.

- DataONE Data Catalog. https://search.dataone.org/data (accessed 26 February 2024).

- Gallo-Cajiao E, Lieberman S, Dolšak N, et al. Global governance for pandemic prevention and the wildlife trade. Lancet Planet Health 2023, 7, e336–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).