Submitted:

12 July 2024

Posted:

15 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction:

2. Method:

2.1. Obesity and Functional Constipation:

3. In Summary:

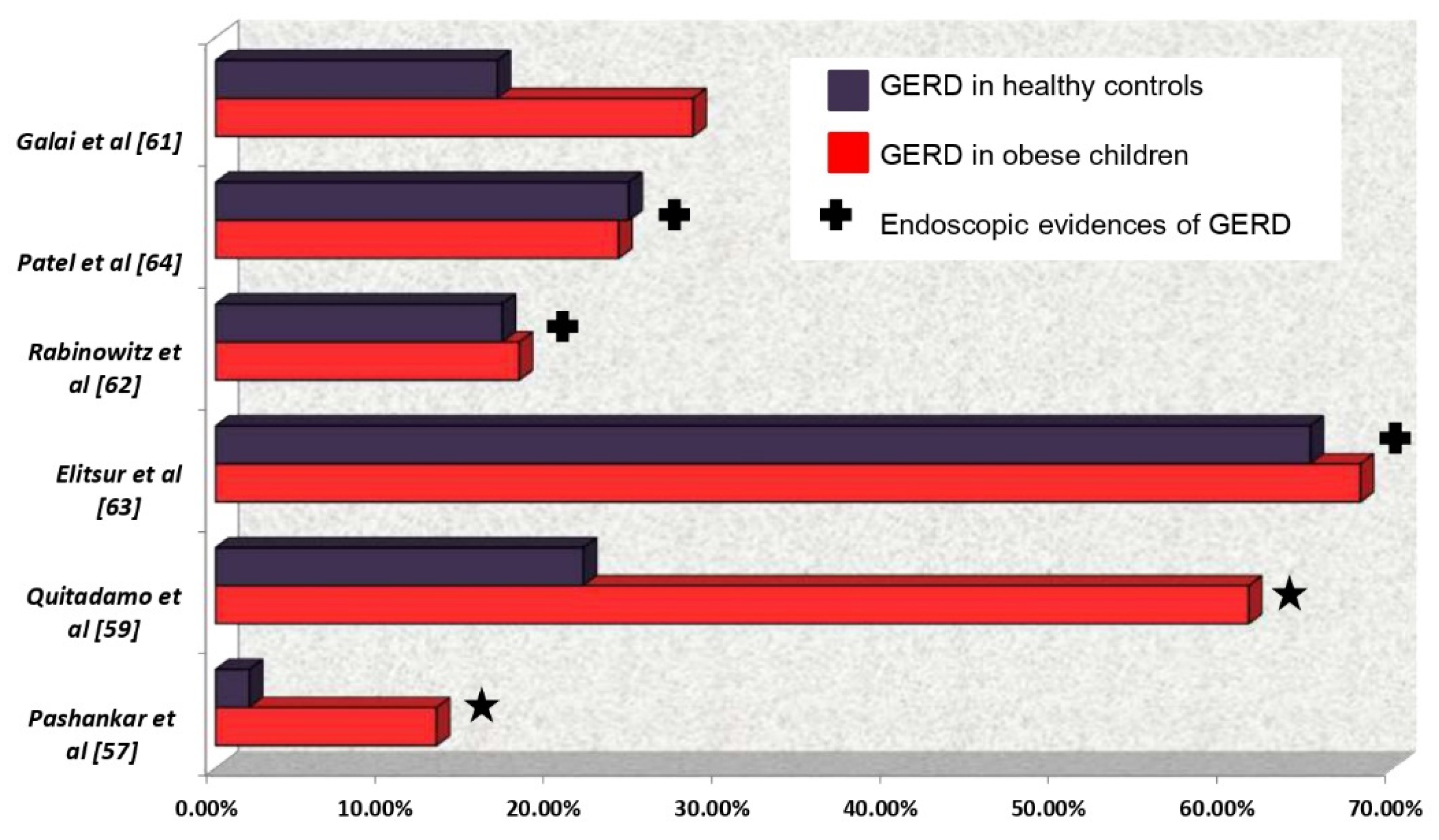

3.1. Obesity and Gastro-Esophageal Reflux:

4. In Summary

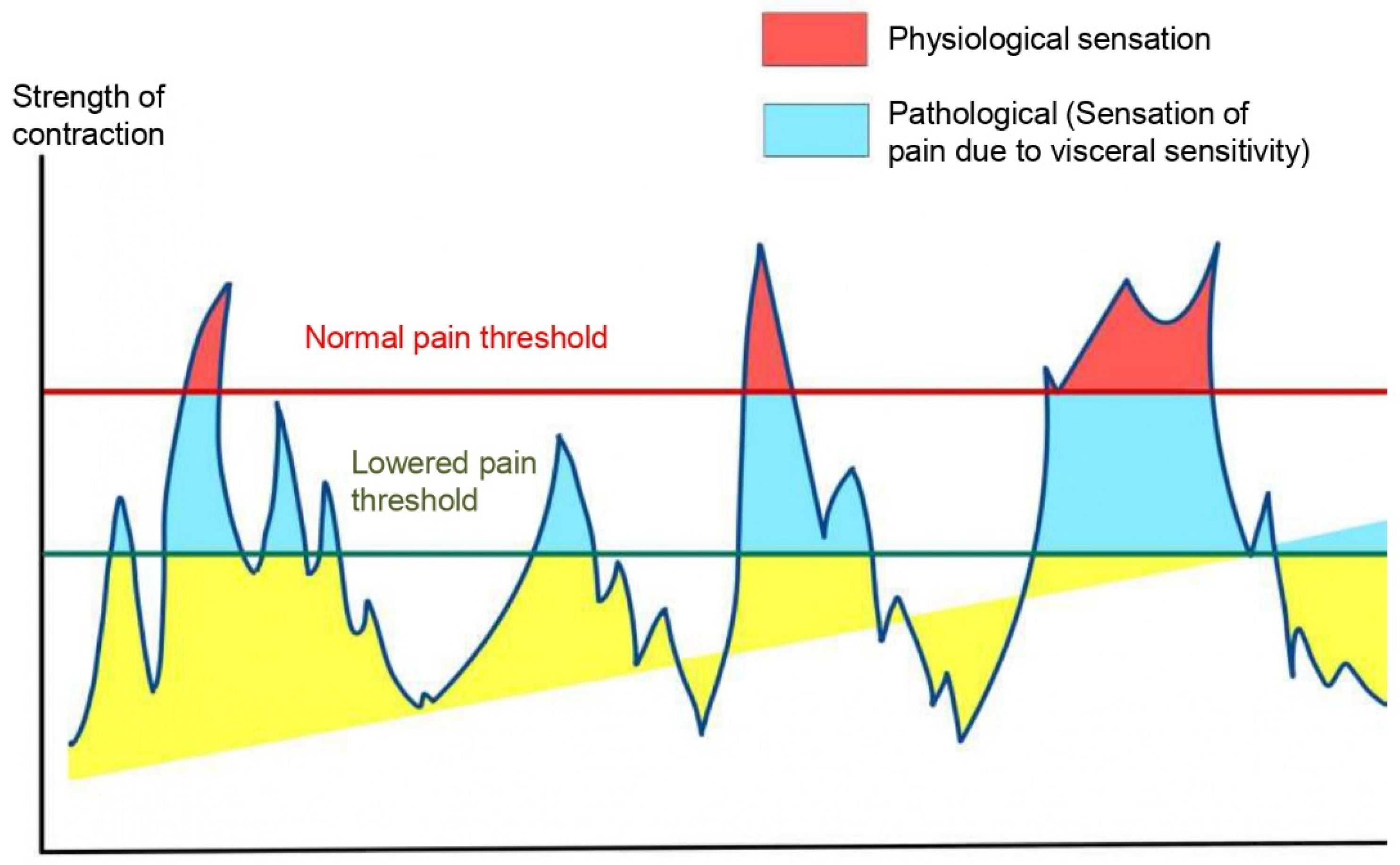

4.1. Obesity and Functional Abdominal Pain (FAP):

5. In Summary:

Funding/Support

Data availability

Conflicts of Interest Disclosures (includes financial disclosures)

Abbreviations:

| ACTH | Adrenocorticotrophic Hormone. |

| BMI | Body Mass Index. |

| CCK | Cholecystokinin. |

| CRF | Corticotrophin Releasing Factor. |

| EM | Esophageal microbiome |

| FAPS | Funcronal Abdominal Pain Syndrome. |

| FC | Functional Constipation. |

| FODMAP | Fermentable Oligo-, Di-, and Monosaccharides and Polyols |

| GER | Gastroesophageal Reflux |

| GERD | Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease |

| GET | Gastric Emptying Time. |

| GI | Gastrointestinal. |

| GLP | Glucagon Like Peptide |

| IL | Interleukin |

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| PYY | Peptide YY |

| TLESR | Transient Lower Esophageal Sphincter Relaxation |

| TNF | Tumor Necrosis Factor |

References

- World Health Organization. Obesity and overweight. 2021 Jun; Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight.

- Bryan S, Afful J, Carroll M, Te-Ching C, Orlando D, Fink S, et al. NHSR 158. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2017–March 2020 Pre-pandemic Data Files [Internet]. National Center for Health Statistics (U.S.); 2021 Jun [cited 2023 Jul 22]. Available from: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/106273.

- Smith JD, Fu E, Kobayashi MA. Prevention and Management of Childhood Obesity and Its Psychological and Health Comorbidities. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2020 May 7;16(1):351–78. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The GBD 2015 Obesity Collaborators. Health Effects of Overweight and Obesity in 195 Countries over 25 Years. N Engl J Med. 2017 Jul 6;377(1):13–27. [CrossRef]

- Huang JS, Barlow SE, Quiros-Tejeira RE, Scheimann A, Skelton J, Suskind D, et al. Childhood obesity for pediatric gastroenterologists. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013 Jan;56(1):99–109. [CrossRef]

- Ho W, Spiegel BMR. The relationship between obesity and functional gastrointestinal disorders: causation, association, or neither? Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008 Aug;4(8):572–8. [PubMed]

- Phatak UP, Pashankar DS. Obesity and Gastrointestinal Disorders in Children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2015 Apr;60(4):441–5. [CrossRef]

- Silveira EA, Santos AS e A de C, Ribeiro JN, Noll M, dos Santos Rodrigues AP, de Oliveira C. Prevalence of constipation in adults with obesity class II and III and associated factors. BMC Gastroenterol. 2021 Dec;21(1):217. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koppen IJN, Vriesman MH, Saps M, Rajindrajith S, Shi X, van Etten-Jamaludin FS, et al. Prevalence of Functional Defecation Disorders in Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Pediatr. 2018 Jul;198:121-130.e6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar K, Gupta N, Malhotra S, Sibal A. Functional constipation: A common and often overlooked cause for abdominal pain in children. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2023 Apr;42(2):274–8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teitelbaum JE, Sinha P, Micale M, Yeung S, Jaeger J. Obesity is Related to Multiple Functional Abdominal Diseases. J Pediatr. 2009 Mar;154(3):444–6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fishman L, Lenders C, Fortunato C, Noonan C, Nurko S. Increased prevalence of constipation and fecal soiling in a population of obese children. J Pediatr. 2004 Aug;145(2):253–4. [CrossRef]

- Baan-Slootweg OH, Liem O, Bekkali N, van Aalderen WM, Rijcken THP, Di Lorenzo C, et al. Constipation and Colonic Transit Times in Children with Morbid Obesity. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011 Apr;52(4):442–5. [CrossRef]

- Tambucci R, Quitadamo P, Ambrosi M, De Angelis P, Angelino G, Stagi S, et al. Association Between Obesity/Overweight and Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders in Children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2019 Apr;68(4):517–20. [CrossRef]

- Phatak UP, Pashankar DS. Prevalence of functional gastrointestinal disorders in obese and overweight children. Int J Obes. 2014 Oct;38(10):1324–7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misra S, Lee A, Gensel K. Chronic Constipation in Overweight Children. J Parenter Enter Nutr. 2006 Mar;30(2):81–4. [CrossRef]

- Pashankar DS, Loening-Baucke V. Increased Prevalence of Obesity in Children With Functional Constipation Evaluated in an Academic Medical Center. Pediatrics. 2005 Sep 1;116(3):e377–80. [CrossRef]

- Kumar SS, Kumar SS, Shirley SA. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in children with functional constipation aged 6 to 12 years attending outpatient department in a tertiary care hospital at Tamil Nadu, India. Int J Contemp Pediatr. 2020 Nov 24;7(12):2359. [CrossRef]

- Koppen IJN, Velasco-Benítez CA, Benninga MA, Di Lorenzo C, Saps M. Is There an Association between Functional Constipation and Excessive Bodyweight in Children? J Pediatr. 2016 Apr;171:178-182.e1. [CrossRef]

- Costa ML, Oliveira JN, Tahan S, Morais MB. Overweight and constipation in adolescents. BMC Gastroenterol. 2011 Dec;11(1):40. [CrossRef]

- Kiefte-de Jong JC, De Vries JH, Escher JC, Jaddoe VWV, Hofman A, Raat H, et al. Role of dietary patterns, sedentary behaviour and overweight on the longitudinal development of childhood constipation: the Generation R study: Dietary patterns and constipation. Matern Child Nutr. 2013 Oct;9(4):511–23. [CrossRef]

- Misra S, Liaw A. Controversies on the relationship between increased body mass index and treatment-resistant chronic constipation in children. J Parenter Enter Nutr. 2022 Jul;46(5):1031–5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tantawy S, Kamel D, Abdel-Basset W, Elgohary H. Effects of a proposed physical activity and diet control to manage constipation in middle-aged obese women. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes Targets Ther. 2017 Dec;Volume 10:513–9. [CrossRef]

- Miron I. Gastrointestinal Motility Disorders in Obesity. Acta Endocrinol Buchar. 2019;15(4):497–504. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen CY, Tsai CY. Ghrelin and Motilin in the Gastrointestinal System. Curr Pharm Des. 2012 Sep 2;18(31):4755–65. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding S, Lund PK. Role of intestinal inflammation as an early event in obesity and insulin resistance: Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2011 Jul;14(4):328–33. [CrossRef]

- Moradi M, Mozaffari H, Askari M, Azadbakht L. Association between overweight/obesity with depression, anxiety, low self-esteem, and body dissatisfaction in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2022 Jan 19;62(2):555–70. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore CJ, Cunningham SA. Social Position, Psychological Stress, and Obesity: A Systematic Review. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012 Apr;112(4):518–26. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alang N, Kelly CR. Weight Gain After Fecal Microbiota Transplantation. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2015 Jan 1;2(1):ofv004. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turnbaugh PJ, Hamady M, Yatsunenko T, Cantarel BL, Duncan A, Ley RE, et al. A core gut microbiome in obese and lean twins. Nature. 2009 Jan;457(7228):480–4. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu L, Liu W, Alkhouri R, Baker RD, Bard JE, Quigley EM, et al. Structural changes in the gut microbiome of constipated patients. Physiol Genomics. 2014 Sep 15;46(18):679–86. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandenplas Y, Carnielli VP, Ksiazyk J, Luna MS, Migacheva N, Mosselmans JM, et al. Factors affecting early-life intestinal microbiota development. Nutrition. 2020 Oct;78:110812. [CrossRef]

- Zhao Y, Encinosa W. Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD) Hospitalizations in 1998 and 2005. In: Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs [Internet]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2006 [cited 2023 Jul 25]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK56308/.

- Eslick GD. Gastrointestinal symptoms and obesity: a meta-analysis: GI symptoms and obesity. Obes Rev. 2012 May;13(5):469–79. [CrossRef]

- Cho JH, Shin CM, Han KD, Yoon H, Park YS, Kim N, et al. Abdominal obesity increases risk for esophageal cancer: a nationwide population-based cohort study of South Korea. J Gastroenterol. 2020 Mar;55(3):307–16. [CrossRef]

- Malaty H. Obesity and gastroesophageal reflux disease and gastroesophageal reflux symptoms in children. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2009 Mar;31. [CrossRef]

- Pashankar DS, Corbin Z, Shah SK, Caprio S. Increased Prevalence of Gastroesophageal Reflux Symptoms in Obese Children Evaluated in an Academic Medical Center. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009 May;43(5):410–3. [CrossRef]

- Størdal K, Johannesdottir GB, Bentsen BS, Carlsen KCL, Sandvik L. Asthma and overweight are associated with symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux. Acta Paediatr. 2006 Oct 1;95(10):1197–201. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quitadamo P, Buonavolontà R, Miele E, Masi P, Coccorullo P, Staiano A. Total and Abdominal Obesity Are Risk Factors for Gastroesophageal Reflux Symptoms in Children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012 Jul;55(1):72–5. [CrossRef]

- Koebnick C, Getahun D, Smith N, Porter AH, Der-Sarkissian JK, Jacobsen SJ. Extreme childhood obesity is associated with increased risk for gastroesophageal reflux disease in a large population-based study. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2011 Jun;6(2–2):e257–63. [CrossRef]

- Galai T, Moran-Lev H, Cohen S, Ben-Tov A, Levy D, Weintraub Y, et al. Higher prevalence of obesity among children with functional abdominal pain disorders. BMC Pediatr. 2020 May 6;20(1):193. [CrossRef]

- Elitsur Y, Dementieva Y, Elitsur R, Rewalt M. Obesity Is Not a Risk Factor in Children With Reflux Esophagitis: A Retrospective Analysis of 738 Children. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2009 Jun;7(3):211–4. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel NR, Ward MJ, Beneck D, Cunningham-Rundles S, Moon A. The Association between Childhood Overweight and Reflux Esophagitis. J Obes. 2010;2010:1–5. [CrossRef]

- Rabinowitz SS, Goli S, Xu J, Zhang X, Nicastri A, Anderson V, et al. Lack of correlation between obesity and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) in a pediatric cohort. Open J Pediatr. 2013;03(04):317–23. [CrossRef]

- Yamasaki T, Hemond C, Eisa M, Ganocy S, Fass R. The Changing Epidemiology of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: Are Patients Getting Younger? J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2018 Oct 1;24(4):559–69. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

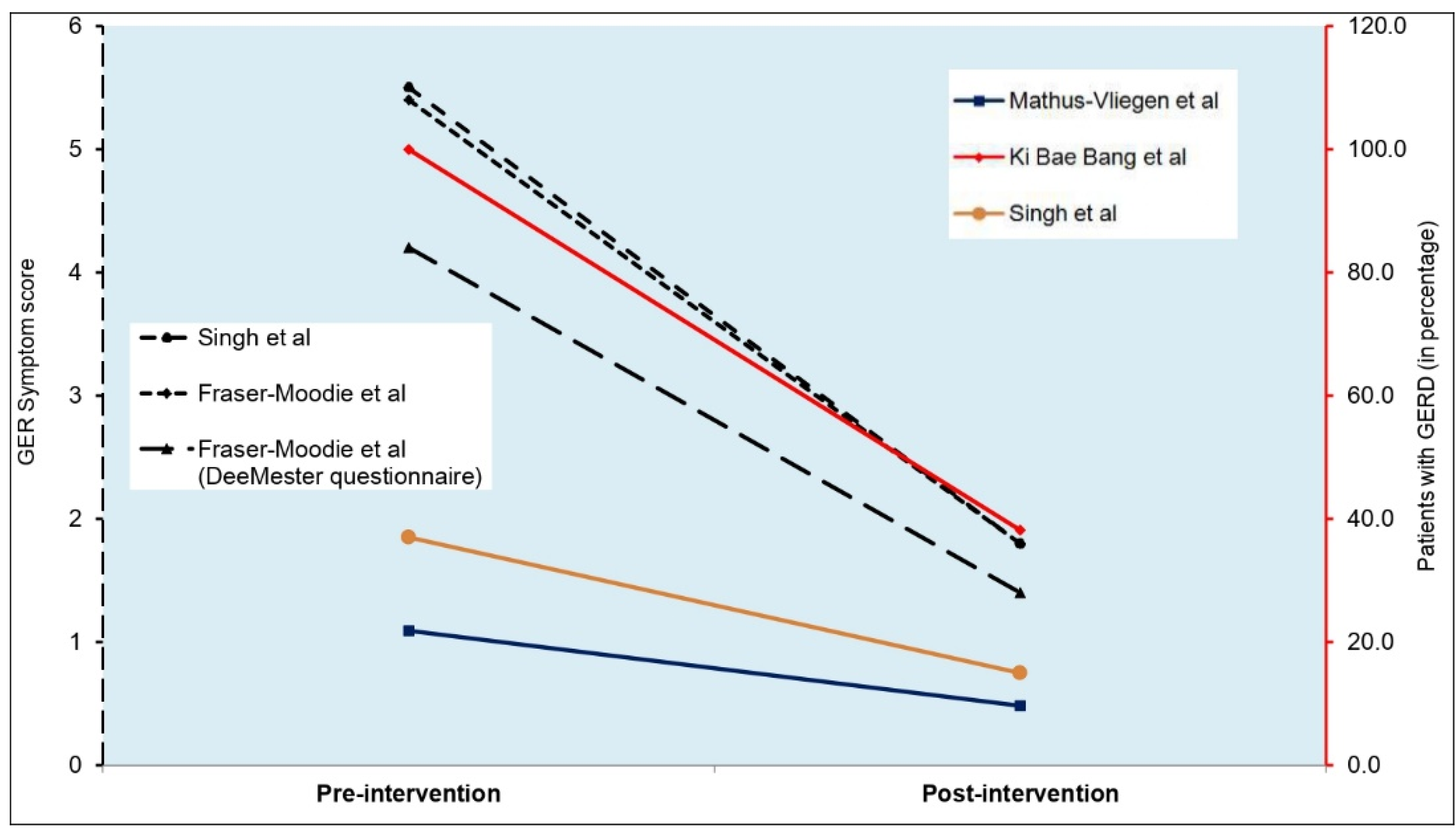

- Singh M, Lee J, Gupta N, Gaddam S, Smith BK, Wani SB, et al. Weight loss can lead to resolution of gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms: A prospective intervention trial. Obesity. 2013 Feb;21(2):284–90. [CrossRef]

- De Groot NL, Burgerhart JS, Van De Meeberg PC, De Vries DR, Smout AJPM, Siersema PD. Systematic review: the effects of conservative and surgical treatment for obesity on gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009 Dec;30(11–12):1091–102. [CrossRef]

- Buckles DC, Sarosiek I, McCallum RW, McMillin C. Delayed Gastric Emptying in Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: Reassessment with New Methods and Symptomatic Correlations. Am J Med Sci. 2004 Jan;327(1):1–4. [CrossRef]

- Quitadamo P, Zenzeri L, Mozzillo E, Cuccurullo I, Rocco A, Franzese A, et al. Gastric Emptying Time, Esophageal pH-Impedance Parameters, Quality of Life, and Gastrointestinal Comorbidity in Obese Children and Adolescents. J Pediatr. 2018 Mar;194:94–9. [CrossRef]

- Barak N, Ehrenpreis ED, Harrison JR, Sitrin MD. Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in obesity: pathophysiological and therapeutic considerations. Obes Rev. 2002 Feb;3(1):9–15. [CrossRef]

- Herzlinger M, Cerezo C. Functional Abdominal Pain and Related Syndromes. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2018 Jan;27(1):15–26. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korterink JJ, Diederen K, Benninga MA, Tabbers MM. Epidemiology of Pediatric Functional Abdominal Pain Disorders: A Meta-Analysis. Zhang L, editor. PLOS ONE. 2015 May 20;10(5):e0126982. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malaty HM, Abudayyeh S, Fraley K, Graham DY, Gilger MA, Hollier DR. Recurrent abdominal pain in school children: effect of obesity and diet. Acta Paediatr. 2007 Apr;96(4):572–6. [CrossRef]

- Fifi AC, Velasco-Benitez C, Saps M. Functional Abdominal Pain and Nutritional Status of Children. A School-Based Study. Nutrients. 2020 Aug 24;12(9):2559. [CrossRef]

- Shepherd SJ, Lomer MCE, Gibson PR. Short-Chain Carbohydrates and Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013 May;108(5):707–17. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomassen RA, Luque V, Assa A, Borrelli O, Broekaert I, Dolinsek J, et al. An ESPGHAN Position Paper on the Use of Low-FODMAP Diet in Pediatric Gastroenterology. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2022 Sep;75(3):356–68. [CrossRef]

- Yanping W, Gao X, Cheng Y, Liu M, Liao S, Zhou J, et al. The interaction between obesity and visceral hypersensitivity. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Mar;38(3):370–7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee SH, Kim KN, Kim KM, Joo NS. Irritable Bowel Syndrome May Be Associated with Elevated Alanine Aminotransferase and Metabolic Syndrome. Yonsei Med J. 2016;57(1):146. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayer EA, Savidge T, Shulman RJ. Brain–Gut Microbiome Interactions and Functional Bowel Disorders. Gastroenterology. 2014 May;146(6):1500–12. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mars RAT, Yang Y, Ward T, Houtti M, Priya S, Lekatz HR, et al. Longitudinal Multi-omics Reveals Subset-Specific Mechanisms Underlying Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Cell. 2020 Nov;183(4):1137–40. [CrossRef]

- Giannetti E, Maglione M, Alessandrella A, Strisciuglio C, De Giovanni D, Campanozzi A, et al. A Mixture of 3 Bifidobacteria Decreases Abdominal Pain and Improves the Quality of Life in Children With Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Multicenter, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Crossover Trial. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2017 Jan;51(1):e5–10. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).