Submitted:

12 July 2024

Posted:

15 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

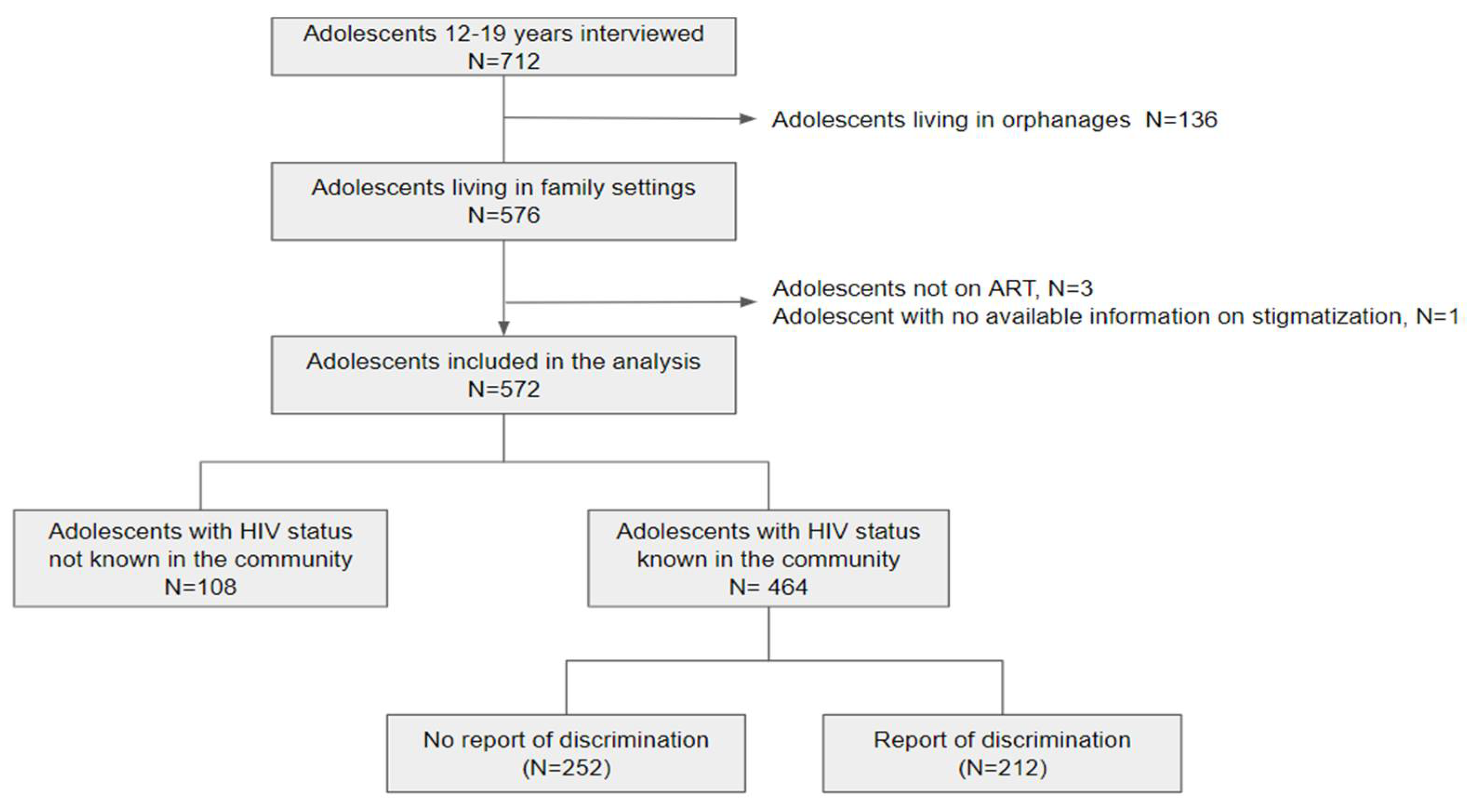

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Inclusion Criteria

2.2. Variables of interest: Stigma or Discrimination

2.3. Quantitative analysis

Covariates

Rationale for selecting the covariates included in the analysis

Statistical analyses

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the study population

3.2. Quantitative Analysis

3.3. Multivariable Analysis

| Any experience of stigma/discrimination | Diverse stigma/discrimination | Repeated stigma/discrimination | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariable | Multivariable | Univariable | Multivariable | Univariable | Multivariable | |||||||

| Factors | OR (95%CI) | p | aOR (95%CI) | p | OR (95%CI) | p | aOR (95%CI) | p | OR (95%CI) | p | aOR (95%CI) | p |

| Age | >0.99 | 0.15 | 0.90 | 0.99 | 0.48 | 0.09 | ||||||

| 12-13 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| 14-15 | 1.02 (0.67-1.57) | 1.51(0.91-2.53) | 0.94 (0.57-1.54) | 0.99 (0.58-1.70) | 1.05 (0.63-1.75) | 1.28 (0.74-2.22) | ||||||

| 16-19 | 1.00 (0.61-1.65) | 1.73(0.92-3.27) | 1.14 (0.64-2.06) | 0.98 (0.51-1.84) | 1.57 (0.90-2.72) | 2.13 (1.14-3.95) | ||||||

| Sex Female |

Ref | 0.72 | Ref | 0.74 | Ref | 0.89 | Ref | 0.24 | Ref | 0.87 | Ref | 0.39 |

| Male | 1.07 (0.74-1.55) | 0.93 (0.59-1.45) | 0.97 (0.63-1.49) | 0.75 (0.45-1.22) | 0.93 (0.60-1.44) | 0.80 (0.49-1.31) | ||||||

| Region | 0.07 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.01 | |||||||

| Center | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| North | 1.38 (0.84-2.28) | 1.46 (0.84-2.56) | 1.07 (0.60-1.99) | 1.21 (0.65-2.34) | 0.80 (0.46-1.45) | 0.75 (0.41-1.39) | ||||||

| North-East | 2.64 (1.31-5.40) | 2.93 (1.36-6.45) | 2.67 (1.25-5.78) | 2.70 (1.21-6.13) | 2.17 (1.04-4.58) | 2.25 (1.04-4.94) | ||||||

| South | 1.68 (0.49-5.81) | 3.31 (0.77-15.5) | 1.94 (0.47-6.97) | 2.29 (0.52-8.89) | 0.63 (0.09-2.65) | 0.54 (0.08-2.46) | ||||||

| School delay | 0.38 | 0.16 | 0.19 | |||||||||

| No | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||||||||

| Yes | 1.25 (0.76-2.04) | 1.48 (0.85-2.53) | 1.46 (0.83-2.50) | |||||||||

| Orphan | 0.30 | 0.72 | 0.79 | |||||||||

| No | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||||||||

| Yes | 0.82 (0.57-1.19) | 0.93 (0.60-1.42) | 0.94 (0.61-1.45) | |||||||||

| Adolescent aware of his status | 0.03 | 0.15 | <0.01 | 0.01 | 0.35 | |||||||

| No | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||||||

| Yes | 1.98 (1.04-3.95) | 1.79 (0.81-4.12) | 3.52 (1.38-11.9) | 3.55 (1.30-12.6) | 1.45 (0.69-3.44) | |||||||

| Perception of adolescent’s health | 0.54 | 0.24 | 0.87 | |||||||||

| Good | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||||||||

| Very good | 0.87 (0.56-1.36) | 0.74 (0.45-1.23) | 1.04 (0.62-1.79) | |||||||||

| Perception of adolescent’s happiness | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.87 | |||||||||

| Happy | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||||||||

| Unhappy | 0.70 (0.24-1.93) | 1.47 (0.45-4.13) | 1.10 (0.30-3.24) | |||||||||

| Perception of adolescent’s intellectual ability | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | ||||||

| Good | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Low | 3.10 (1.69-5.91) | 3.35 (1.66-7.10) | 2.45 (1.32-4.45) | 2.99 (1.52-5.88) | 2.40 (1.29-4.39) | 2.92 (1.49-5.66) | ||||||

| Conflicts with adolescents | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.15 | 0.53 | ||||||

| No | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Yes | 1.83 (1.26-2.66) | 1.81 (1.17-2.79) | 1.73 (1.12-2.66) | 1.54 (0.96-2.49) | 1.38 (0.89-2.13) | 1.17 (0.72-1.89) | ||||||

| Age at ART initiation (years) | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.47 | 0.68 | ||||||||

| 0-6 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||||

| 7-19 | 0.69 (0.46-1.02) | 0.64 (0.40-1.02) | 0.76 (0.48-1.20) | 0.91 (0.57-1.45) | ||||||||

| Adherence to treatment | 0.30 | 0.94 | 0.79 | |||||||||

| Good | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||||||||

| Very good | 1.43 (0.72-2.92) | 0.97 (0.46-2.24) | 1.11 (0.52-2.69) | |||||||||

| BMI | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.92 | 0.98 | ||||||||

| <18.5 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||||

| >18.5 | 0.71 (0.48-1.05) | 0.61 (0.37-0.98) | 0.94 (0.60-1.47) | 0.99 (0.63-1.55) | ||||||||

| CD4 cell count (cells/mm3) | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.97 | 0.87 | ||||||||

| <500 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||||

| >500 | 1.43 (0.96-2.14) | 1.57 (0.98-2.55) | 0.98 (0.62-1.56) | 1.04 (0.66-1.67) | ||||||||

| Viral load | 0.74 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.50 | ||||||||

| Detectable | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||||

| Undetectable | 0.92 (0.57-1.48) | 1.78 (1.05-2.96) | 1.63 (0.89-2.93) | 1.20 (0.69-2.05) | ||||||||

| Caregiver member of a support group | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | ||||||

| No | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Yes | 2.34 (1.61-3.42) | 2.28 (1.48-3.53) | 2.08 (1.35-3.21) | 1.88 (1.18-3.04) | 2.25 (1.46-3.51) | 1.99 (1.24-3.23) | ||||||

3.4. Qualitative Analysis : Experiences of Stigma or Social Discrimination

- Bullying or moral harassment

- Social isolation

- Behavioral discrimination

- Public Disclosure

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations General Assembly. Political Declaration on HIV/AIDS (Resolution 60/262), 2006. Accessed February 26th 2024 https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/sub_landing/files/20060615_hlm_politicaldeclaration_ares60262_en.pdf.

- UNAIDS, Evidence for eliminating HIV-related stigma and discrimination, 2020. Accessed February 26th, 2024. https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/eliminating-discrimination-guidance_en.pdf.

- United Nations Agency for International Development (UNAIDS). Protocol for identification of discrimination against people living with HIV. 2000. Accessed February 26th, 2024. https://data.unaids.org/publications/irc-pub01/jc295-protocol_en.pdf.

- Hatzenbuehler, M.L.; Phelan, J.C.; Link, B.G. Stigma as a Fundamental Cause of Population Health Inequalities. Am. J. Public Heal. 2013, 103, 813–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Relf, M.V.; Holzemer, W.P.L.; Holt, L.M.; Nyblade, L.; Caiola, C.P.E. A Review of the State of the Science of HIV and Stigma: Context, Conceptualization, Measurement, Interventions, Gaps, and Future Priorities. J. Assoc. Nurses AIDS Care 2021, 32, 392–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cluver, L.; Orkin, M. Cumulative risk and AIDS-orphanhood: Interactions of stigma, bullying and poverty on child mental health in South Africa. Soc. Sci. Med. 2009, 69, 1186–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Wu, Q.; Zhao, J.; Zhao, G.; Li, X.; Du, H.; Chi, P. Enacted Stigma Influences Bereavement Coping Among Children Orphaned by Parental AIDS: A Longitudinal Study with Network Analysis. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2023, ume 16, 4949–4958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horsakulchai, W.; Sermprasartkul, T.; Sumetchoengprachya, P.; Chummaneekul, P.; Rungruang, N.; Uthis, P.; Sripan, P.; Srithanaviboonchai, K. Factors associated with internalized HIV-related stigma among people living with HIV in Thailand. AIDS Care 2024, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowther, K.; Selman, L.; Harding, R.; Higginson, I.J. Experience of persistent psychological symptoms and perceived stigma among people with HIV on antiretroviral therapy (ART): A systematic review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2014, 51, 1171–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merville, O.; Puangmala, P.; Suksawas, P.; Kliangpiboon, W.; Keawvilai, W.; Tunkam, C.; Yama, S.; Sukhaphan, U.; Sathan, S.; Marasri, S.; et al. School trajectory disruption among adolescents living with perinatal HIV receiving antiretroviral treatments: a case-control study in Thailand. BMC Public Heal. 2021, 21, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Logie, C.; Gadalla, T. Meta-analysis of health and demographic correlates of stigma towards people living with HIV. AIDS Care 2009, 21, 742–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimera, E.; Vindevogel, S.; Reynaert, D.; Justice, K.M.; Rubaihayo, J.; De Maeyer, J.; Engelen, A.-M.; Musanje, K.; Bilsen, J. Experiences and effects of HIV-related stigma among youth living with HIV/AIDS in Western Uganda: A photovoice study. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0232359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brener, L.; Callander, D.; Slavin, S.; de Wit, J. Experiences of HIV stigma: The role of visible symptoms, HIV centrality and community attachment for people living with HIV. AIDS Care 2013, 25, 1166–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, I.T.; E Ryu, A.; Onuegbu, A.G.; Psaros, C.; Weiser, S.D.; Bangsberg, D.R.; Tsai, A.C. Impact of HIV-related stigma on treatment adherence: systematic review and meta-synthesis. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2013, 16, 18640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L.; Munir, K.; Kanabkaew, C.; Le Coeur, S. Factors influencing antiretroviral treatment suboptimal adherence among perinatally HIV-infected adolescents in Thailand. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0172392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutakumwa, R.; Zalwango, F.; Richards, E.; Seeley, J. Exploring the Care Relationship between Grandparents/Older Carers and Children Infected with HIV in South-Western Uganda: Implications for Care for Both the Children and Their Older Carers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2015, 12, 2120–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amuri, M.; Mitchell, S.; Cockcroft, A.; Andersson, N. Socio-economic status and HIV/AIDS stigma in Tanzania. AIDS Care 2011, 23, 378–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiener, L.S.; Battles, H.B.; Heilman, N.; Sigelman, C.K.; A Pizzo, P. Factors associated with disclosure of diagnosis to children with HIV/AIDS. 1996, 7, 310–24. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Robinson, A.; Cooney, A.; Fassbender, C.; McGovern, D.P. Examining the Relationship Between HIV-Related Stigma and the Health and Wellbeing of Children and Adolescents Living with HIV: A Systematic Review. AIDS Behav. 2023, 27, 3133–3149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalichman, S.C.; Sikkema, K.J.; Somlai, A. People living with HIV infection who attend and do not attend support groups: A pilot study of needs, characteristics and experiences. AIDS Care 1996, 8, 589–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tzemis, D.; Forrest, J.I.; Puskas, C.M.; Zhang, W.; Orchard, T.R.; Palmer, A.K.; McInnes, C.W.; Fernades, K.A.; Montaner, J.S.; Hogg, R.S. Identifying self-perceived HIV-related stigma in a population accessing antiretroviral therapy. AIDS Care 2012, 25, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rayanakorn, A.; Ong-Artborirak, P.; Ademi, Z.; Chariyalertsak, S. Predictors of Stigma and Health-Related Quality of Life Among People Living with HIV in Northern Thailand. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2022, 36, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chem, E.D.; Ferry, A.; Seeley, J.; Weiss, H.A.; Simms, V. Health-related needs reported by adolescents living with HIV and receiving antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic literature review. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2022, 25, e25921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Health Statistical Office (NHSO), National Statistical Office (NSO) the 2010 Population and Housing Census.

- UNAIDS, Thailand country factsheet, 2022. Accessed February 26th, 2024. https://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/thailand.

- Lolekha, R.; Boonsuk, S.; Plipat, T.; Martin, M.; Tonputsa, C.; Punsuwan, N.; Naiwatanakul, T.; Chokephaibulkit, K.; Thaisri, H.; Phanuphak, P.; et al. Elimination of Mother-to-Child Transmission of HIV — Thailand. Mmwr. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2016, 65, 562–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pannetier, J.; Lelièvre, E.; Le Cœur, S. HIV-related stigma experiences: Understanding gender disparities in Thailand. AIDS Care 2015, 28, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H. Intersectional stigma and coping strategies of single mothers living with HIV in Thailand. Cult. Heal. Sex. 2022, 25, 336–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srithanaviboonchai, K.; Chariyalertsak, S.; Nontarak, J.; Assanangkornchai, S.; Kessomboon, P.; Putwatana, P.; Taneepanichskul, S.; Aekplakorn, W. Stigmatizing attitudes toward people living with HIV among general adult Thai population: Results from the 5th Thai National Health Examination Survey (NHES). PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0187231–e0187231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chautrakarn, S.; Ong-Artborirak, P.; Naksen, W.; Thongprachum, A.; Wungrath, J.; Chariyalertsak, S.; Stonington, S.; Taneepanichskul, S.; Assanangkornchai, S.; Kessomboon, P.; et al. Stigmatizing and discriminatory attitudes toward people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) among general adult population: the results from the 6th Thai National Health Examination Survey (NHES VI). J. Glob. Heal. 2023, 13, 04006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberdorfer Perceived and Experienced Stigma and Discrimination among Caregivers of Perinatally HIV-Infected Adolescents in Thailand. J. Ther. Manag. HIV Infect. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Charles H. Washington, Peninnah Oberdorfer. Stigma and Discrimination among Perinatally HIV-Infected Adolescents Receiving HAART in Thailand. International Journal of Sociology Study; 2014 2, 33-41.

- Le Coeur S, Lelièvre E, Kanabkaew C, Sirirungsi W. A Survey of Adolescents Born with HIV: The TEEWA project in Thailand. Population (English edition) 2017, 72: 333-356. [CrossRef]

- Bursac, Z.; Gauss, C.H.; Williams, D.K.; Hosmer, D.W. Purposeful selection of variables in logistic regression. Source Code Biol. Med. 2008, 3, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aurpibul, L.; Tangmunkongvorakul, A.; Detsakunathiwatchara, C.; Masurin, S.; Srita, A.; Meeart, P.; Chueakong, W. Social effects of HIV disclosure, an ongoing challenge in young adults living with perinatal HIV: a qualitative study. Front. Public Heal. 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hogwood, J.; Campbell, T.; Butler, S. I wish I could tell you but I can’t: Adolescents with perinatally acquired HIV and their dilemmas around self-disclosure. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2012, 18, 44–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, R.S.; Boonsuk, P.; Dandu, M.; Sohn, A.H. Experiences with stigma and discrimination among adolescents and young adults living with HIV in Bangkok, Thailand. AIDS Care 2019, 32, 530–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fair, C.D.; Berk, M. Provider perceptions of stigma and discrimination experienced by adolescents and young adults with pHiV while accessing sexual and reproductive health care. AIDS Care 2017, 30, 178–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thai, T.T.; Tran, V.B.; Nguyen, N.B.T.; Bui, H.H.T. HIV-related stigma, symptoms of depression and their association with suicidal ideation among people living with HIV in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. Psychol. Heal. Med. 2022, 28, 1263–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aurpibul, L.; Kosalaraksa, P.; Kawichai, S.; Lumbiganon, P.; Ounchanum, P.; Songtaweesin, W.N.; Sudjaritruk, T.; Chokephaibulkit, K.; Rungmaitree, S.; Suwanlerk, T.; et al. Alcohol use, suicidality and virologic non-suppression among young adults with perinatally acquired HIV in Thailand: a cross-sectional study. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2023, 26, e26064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, J.V.; Abramowitz, S.; Koenig, L.J.; Chandwani, S.; Orban, L. Negative life events and depression in adolescents with HIV: a stress and coping analysis. AIDS Care 2015, 27, 1265–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aurpibul, L.; Sophonphan, J.; Malee, K.; Kerr, S.J.; Sun, L.P.; Ounchanum, P.; Kosalaraksa, P.; Ngampiyaskul, C.; Kanjanavanit, S.; Chettra, K.; et al. HIV-related enacted stigma and increase frequency of depressive symptoms among Thai and Cambodian adolescents and young adults with perinatal HIV. Int. J. STD AIDS 2020, 32, 246–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aurpibul, L.; Detsakunathiwatchara, C.; Khampun, R.; Wongnum, N.; Chotecharoentanan, T.; Sudjaritruk, T. Quality of life and HIV adherence self-efficacy in adolescents and young adults living with perinatal HIV in Chiang Mai, Thailand. AIDS Care 2022, 35, 406–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fair, C.D.; Jutras, A. “I have hope, but I'm worried”: Perspectives on parenting adolescents and young adults living with perinatally-acquired HIV. Fam. Syst. Heal. 2022, 40, 232–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peretti-Watel, P.; Spire, B.; Obadia, Y.; Moatti, J.-P. ; for the VESPA Group Discrimination against HIV-Infected People and the Spread of HIV: Some Evidence from France. PLOS ONE 2007, 2, e411–e411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mofenson, L.M.; Cotton, M.F. The challenges of success: adolescents with perinatal HIV infection. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2013, 16, 18650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siraprapasiri, T.; Srithanaviboonchai, K.; Chantcharas, P.; Suwanphatthana, N.; Ongwandee, S.; Khemngern, P.; Benjarattanaporn, P.; Mingkwan, P.; Nyblade, L. Integration and scale-up of efforts to measure and reduce HIV-related stigma: the experience of Thailand. AIDS 2020, 34, S103–S114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dollfus, C.; Le Chenadec, J.; Faye, A.; Blanche, S.; Briand, N.; Rouzioux, C.; Warszawski, J. Long-Term Outcomes in Adolescents Perinatally Infected with HIV-1 and Followed Up since Birth in the French Perinatal Cohort (EPF/ANRS CO10). Clin. Infect. Dis. 2010, 51, 214–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uthis, P.; Suktrakul, S.; Wiwatwongwana, R.; Tangmunkongvorakul, A.; Sripan, P.; Srithanaviboonchai, K. The Thai Internalized HIV-related Stigma Scale. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1134648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desmonde, S.; Lolekha, R.; Costantini, S.; Siraprapasiri, T.; Frank, S.; Bakkali, T.; Benjarattanaporn, P.; Hou, T.; Jantaramanee, S.; Kuttiparambil, B.; et al. A focused multi-state model to estimate the pediatric and adolescent HIV epidemic in Thailand, 2005–2025. PLOS ONE 2022, 17, e0276330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernet, M.; Wong, K.; Richard, M.-E.; Otis, J.; Lévy, J.J.; Lapointe, N.; Samson, J.; Morin, G.; Thériault, J.; Trottier, G. Romantic relationships and sexual activities of the first generation of youth living with HIV since birth. AIDS Care 2011, 23, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Coeur S, Hoang Ngoc Minh P, Sriphetcharawut S, Jongpaijitsakul P, Lallemant M, Puangmala P. The Teens Living with Antiretrovirals (TEEWA) study group. Mortality among adolescents living with perinatal HIV (APHIV) receiving antiretroviral therapy (ART): the Teens Living with Antiretrovirals (TEEWA) study in Thailand. 23rd Intl AIDS Conference (Aids 2020), 6-10 July 2020, San Francisco, USA.

- National Committee for the Prevention and Response to AIDS. Thailand National Strategy to End AIDS 2017-2030. April 2017.

- Harris, J.; Thaiprayoon, S. Common factors in HIV/AIDS prevention success: lessons from Thailand. BMC Heal. Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics of adolescents, (from caregivers, % | Total | Knowledge of the HIV status in the community | Report of stigma/discrimination | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | p | Yes | No | p | ||

| All | 572 (100) | 464 (81.1) | 108 (18.9) | 212 (45.7) | 252 (54.3) | ||

| Sex (female) | 334 (58.4) | 269 (57.8) | 65 (60.1) | 0.70 | 121 (57.0) | 148 (58.7) | 0.70 |

| Age (years) | 14.4 | 14.5 | 14.2 | 0.40 | 14.5 | 14.4 | 0.80 |

| Median [IQR] | 13.1, 16.0 | 13.2- 16.0 | 12.9-15.4 | 13.3-15.9 | 13.1, 16.2 | ||

| 12-13 | 203 (35.4) | 159 (34.2) | 44 (40.7) | 74 (34.9) | 85 (33.7) | ||

| 14-15 | 195 (34.1) | 159 (34.2) | 36 (33.3) | 75 (35.3) | 84 (33.3) | ||

| 16-19 | 174 (30.4) | 146 (31.4) | 28 (25.9) | 63 (29.7) | 83 (32.9) | ||

| Region | <0.01 | <0.01 | |||||

| Center | 139 (24.3) | 83 (17.8) | 56 (51.9) | 31 (14.6) | 52 (20.6) | ||

| North | 336 (58.7) | 315 (67.7) | 21 (19.4) | 142 (67.0) | 173 (68.6) | ||

| North-East | 66 (11.5) | 54 (11.6) | 12 (11.1) | 33 (15.6) | 21 (8.3) | ||

| South | 31 (5.4) | 12 (2.6) | 19 (17.6) | 6 (2.8) | 6 (2.4) | ||

| Orphan from both parents | 245 (42.8) | 220 (47.4) | 25 (23.1) | <0.01 | 95 (44.8) | 125 (49.6) | 0.30 |

| School delay (repeated a school year) | 87 (15.2) | 76 (16.3) | 11 (10.2) | 0.10 | 38 (17.9) | 38 (15.1) | 0.40 |

| Perception of adolescent’s intellectual capacity: low | 82 (14.4) | 72 (15.7) | 10 (9.3) | 0.20 | 47 (22.2) | 25 (10.0) | <0.01 |

| Perception of adolescent’s health: good or very good | 445 (77.8) | 357 (76.8) | 88 (81.4) | 0.40 | 161 (75.9) | 196 (77.8) | 0.60 |

| Perception of adolescents happiness: fair, happy or very happy | 554 (96.9) | 448 (96.3) | 106 (98.1) | 0.50 | 206 (97.1) | 242 (96.0) | 0.50 |

| Conflicts with adolescents | 235 (41.1) | 191 (41.1) | 44 (40.7) | 0.90 | 104 (49.1) | 87 (34.5) | <0.01 |

| Adolescent aware of his/her HIV status | 501 (87.6) | 419 (90.1) | 82 (75.9) | <0.01 | 198 (93.3) | 221 (87.7) | 0.10 |

| Age at ART initiation | 0.40 | 0.06 | |||||

| 0-6 | 180 (31.5) | 144 (31.0) | 36 (33.3) | 75 (35.3) | 69 (27.4) | ||

| 7-12 | 321 (56.1) | 258 (55.5) | 63 (58.3) | 115 (54.2) | 143 (56.7) | ||

| >12 | 55 (9.6) | 48 (10.3) | 7 (6.5) | 16 (7.5) | 32 (12.7) | ||

| Adherence to treatment: good or very good | 519 (90.7) | 421 (90.5) | 98 (90.7) | 0.70 | 196 (92.4) | 225 (89.3) | 0.60 |

| Information obtained from the medical records | |||||||

| BMI>18.5 | 206 (36.0) | 163 (35.1) | 43 (39.8) | 0.40 | 66 (25.0) | 97 (26.2) | 0.08 |

| CD4 cell count >500/cell/mm3 | 386 (67.5) | 318 (68.5) | 68 (63.0) | 0.30 | 154 (72.6) | 164 (65.1) | 0.07 |

| Undetectable viral load (<50 copies/mL) | 467 (81.6) | 378 (81.3) | 89 (82.4) | 0.90 | 174 (82.1) | 204 (81.0) | 0.70 |

| Characteristics of the caregivers | |||||||

| Sex (female) | 445 (77.8) | 354 (76.1) | 91 (84.2) | 0.07 | 167 (78.7) | 187 (74.2) | 0.20 |

| Age (median, IQR) | 50 (41, 60) | 52 (42, 61) | 46 (39, 57) | <0.01 | 52 (42, 61) | 50 (41, 60) | 0.50 |

| Relationship with the adolescent | 0.01 | 0.30 | |||||

| Parents | 77 (13.5) | 53 (11.4) | 24 (22.2) | 23 (10.8) | 30 (11.9) | ||

| Grandparents or siblings | 217 (37.9) | 184 (39.7) | 33 (30.6) | 86 (40.6) | 98 (38.9) | ||

| Aunt or uncle | 138 (24.1) | 117 (25.2) | 21 (19.4) | 46 (21.7) | 71 (28.2) | ||

| Other relatives | 140 (24.5) | 110 (23.7) | 30 (27.8) | 57 (26.9) | 53 (21.0) | ||

| Caregiver’s financial situation: good or very good | 363 (63.5) | 279 (60.0) | 84 (77.8) | <0.01 | 120 (56.6) | 159 (63.1) | 0.20 |

| Caregiver own’s health perception: good or very good | 528 (92.3) | 427 (91.8) | 101 (93.5) | 0.60 | 193 (91.0) | 234 (92.9) | 0.50 |

| Member of a support group | 239 (41.8) | 208 (44.7) | 31 (28.7) | <0.01 | 119 (56.1) | 89 (35.3) | <0.01 |

| N (%) | |

| Adolescents whose HIV status is known in the community | 464 (100.0) |

| Any experience of stigma/discrimination | 212 (45.6) |

| Circumstances of stigma/discrimination* (N=212) | |

| At school | 136 (64.2) |

| From friends | 125 (59.0) |

| From people in the village | 91 (42.9) |

| From family | 22 (10.4) |

| At the hospital | 5 (0.02) |

| Type of stigma/discrimination* (N=212) | |

| Bullying/moral harassment | 130 (61.3) |

| Social isolation | 90 (42.4) |

| Behavioral discrimination | 40 (18.9) |

| Public disclosure | 16 (7.5) |

| Repeated stigma/discrimination experiences** (N=464) | 108 (23.3) |

| Among adolescents with stigma/discrimination experience (N=212) | 108 (50.9) |

| Diverse stigma/discrimination experiences** (N=464) | 111 (23.9) |

| Among adolescents with stigma/discrimination experience (N=212) | 111 (52.3) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).